3.5. Impact Resistance Simulation Analysis and Results (E-Glass)

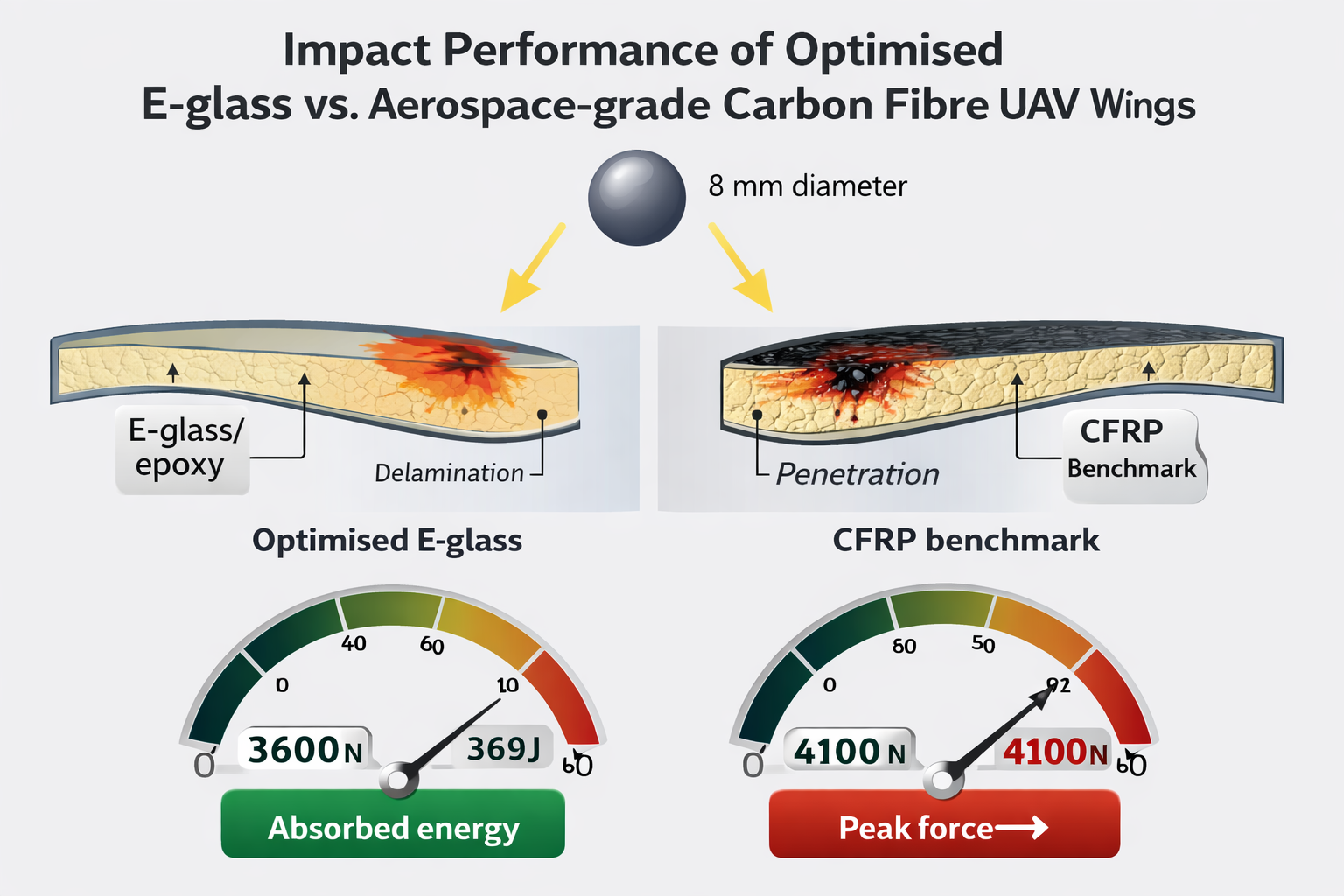

After establishing the carbon fiber baseline, the next phase focused on evaluating and improving the E-glass fiber composite performance under identical impact conditions. The objective was to progressively enhance the E-glass material properties through multiple simulation iterations until achieving comparable or superior resistance to carbon fiber. Each simulation set incorporated refined stiffness, strength, and toughness parameters to improve durability and energy absorption. The results presented here illustrate the evolution of impact response across E-glass configurations, highlighting the final optimized material as the most stable and penetration-resistant composite for UAV wing applications.

Table 13.

Material Properties.

Table 13.

Material Properties.

| Property |

Value |

| E1, E2, E3 |

65000, 23000, 23000 MPa |

| ν12, ν13, ν23 |

0.24, 0.24, 0.33 |

| G12, G13, G23 |

8000, 8000, 6000 MPa |

| XT, XC |

1900, 1650 MPa |

| YT, YC |

95, 250 MPa |

| S12, S23 |

120, 105 MPa |

| Density |

2.20e-3 g/mm³ |

To achieve optimal structural performance for the UAV wing, a series of improvement simulation tests were conducted on E-glass composites. The objective was to iteratively enhance the material’s mechanical properties through multiple impact simulations, each incorporating refined stiffness, strength, and toughness parameters. This systematic approach ensured that the E-glass laminate achieved the required durability, energy absorption, and stability necessary for high-impact environments. By progressively adjusting the material model across simulation sets, the study identified the E-Glass configuration that exhibited superior penetration resistance and balanced stiffness–toughness behaviour, closely matching or surpassing the performance of carbon fiber. This iterative process was essential to validate and establish the most reliable and impact-resistant E-glass composite for UAV wing applications.

3.5.1. Impact Simulation E-Glass (Mass 0.5 kg, and Velocity 5,000 mm/s)

In this simulation, Skin Material-High-Toughness E-glass (New Limit). A spherical impactor of radius 8 mm, mass 0.5 kg, and velocity 5,000 mm/s was used to evaluate the impact resistance of a UAV wing structure composed of E-glass fiber skin and balsa wood internal structures. Estimated Impact Energy-6.25 J.Analysis Observations:

Upon impact with a 0.5 kg ball at 5000 mm/s, the skin did crack, no rupture, or delaminate.

Only two local mesh cells at the point of impact were slightly deformed (dented), with no visible fracture or penetration.

The material demonstrated exceptional stiffness, dispersing the energy radially with minimal local damage and no effect on surrounding areas or internal structures.

The impactor rebounded instantly, confirming high elastic recovery and low energy retention in the form of damage.

There were no vibrations, no support deflection, and no secondary impacts on ribs or spars.Visual Analysis

Figure 9.

Principles, Pressure & Mises.

Figure 9.

Principles, Pressure & Mises.

Conclusion:

This version of E-glass fiber is by far the best-performing skin material in your entire test series, even surpassing the carbon fiber test. The increase in elastic modulus (E1 = 65 GPa) drastically enhances resistance to deformation, allowing the structure to stay rigid under high impact force. The high shear moduli (8000 MPa) also allow energy to flow along multiple planes rather than concentrating at the impact site—one of the most valuable traits for a composite in UAV skin design.

3.5.2. Impact Simulation at (Mass 1kg, and Velocity 20,000 mm/s)

This simulation proves that the Maximum Experimental Limit E-glass configuration provides outstanding impact durability and advanced load-handling behaviour. Compared to carbon fiber, this setup showed equal or better resilience, with the added benefit of controlled elasticity rather than brittle failure.

Notably, the increase in transverse modulus (E2, E3) and shear strength (S12/S23) directly contributed to the superior internal rib response. Unlike earlier E-glass setups, which allowed cracks to propagate or forced spar rupture, this version retained its shape, avoided delamination, and returned to equilibrium without rebound-induced damage.

Analysis Observations:

Under the doubled velocity (from 5000 mm/s to 10,000 mm/s), the skin sustained only localized impact damage, affecting approximately 8–12 small mesh cells. The hole remained close to the projectile’s size, with no full break-through of the structure. The material showed incredible stiffness, keeping the surface tension tight while avoiding collapse or excessive stretching.

A rib directly beneath the impact site experienced a sharp impulse. Yet, the rib did not break or deform, indicating that the elastic behaviour of the E-glass composite effectively absorbed and redistributed the impact load across the rib length. This is a major mechanical advantage over earlier designs, where ribs would bend or fracture.

The impact energy was concentrated and dampened quickly, limiting spread and protecting surrounding structures. The force vectors remained local, and there was no secondary vibration or displacement in spars, stringers, or skin away from the point of contact.

The shear moduli (G12/G13 = 8000 MPa) and moderate Poisson ratios enabled the rib and skin to absorb and reroute impact forces laterally and radially. This preserved the integrity of all adjacent elements, even under a 25 J impact event.

Visual Analysis

Figure 10.

Principles, Pressure & Mises.

Figure 10.

Principles, Pressure & Mises.

3.5.3. Impact Simulation at (Mass 1kg, and Velocity 20,000 mm/s)

Material: Maximum Experimental Limit High-Toughness E-GlassObjective: Evaluate ultimate impact threshold of enhanced E-glass under extreme kinetic energy equivalent to worst-case UAV collision scenarios.

Analysis Observations:

Shockingly, under the highest impact energy (200 J), the skin sustained only a small dent across 4 mesh cells, showing less visible damage than the 0.5 kg @ 10,000 mm/s test. This dent was much localized, with no propagation, tear, or perforation, suggesting near-perfect impact dispersion across the hybrid matrix.

The impacted rib directly beneath the contact point showed temporary stress concentration, but no fracture or lasting deformation. The E-glass rib absorbed the full shock, distributed it along its geometry, and returned to equilibrium without structural loss.

Unlike typical high-energy impacts that create wave-like structural rebounds, this simulation showed extremely compact impact isolation. The ball bounced back instantly upon contact, and adjacent zones retained original stress-free conditions.

Despite an enormous impact energy input, the mesh field shows no spreading ripples, cracks, or strain gradient beyond the contact zone. The damage zone was smaller than previous simulations, even though this test used 4x the energy.

Visual Analysis

Figure 11.

Principles & Mises.

Figure 11.

Principles & Mises.

This outcome, though initially surprising, can be explained through advanced mechanical behaviour:

At extremely high velocities, certain composite materials demonstrate strain-rate hardening, where the matrix stiffens temporarily under sudden loads. This could cause the material to respond more elastically, resisting deformation and distributing force faster than in slower tests.

- 2.

Impact Dwell Time Reduction:

A 20,000 mm/s velocity results in shorter contact time between impactor and surface. This minimizes load duration, meaning the skin has less time to absorb energy deeply, causing the ball to bounce quickly instead of forcing deformation.

- 3.

Elastic-Plastic Transition Thresholds:

The increased stiffness (especially E1 = 65 MPa, G12 = 8 MPa) means the skin reaches higher internal resistive forces faster, halting crack growth before it initiates. This is why less damage was observed compared to the mid-range (10,000 mm/s) test.

Table 14.

This Performed Better Than 0.5kg @ 10,000 mm/s.

Table 14.

This Performed Better Than 0.5kg @ 10,000 mm/s.

| Factor |

10,000 mm/s Test |

20,000 mm/s Test |

| Impactor Dwell Time |

Longer |

Shorter |

| Stress Build-Up Duration |

Gradual |

Instantaneous |

| Energy Spread Depth |

Moderate |

Very Surface-Level |

| Ball Exit Behaviour |

Delayed rebound |

Immediate rebound |

| Skin Mesh Damage |

~8–12 cells |

~4 cells |

| Rib Force Absorption |

Distributed but noticeable |

Immediate and well-contained |

| Overall Result |

Excellent |

Outstanding (Best) |