Submitted:

21 June 2025

Posted:

23 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production of Biocomposite Plates

2.2. Impact Tests and Statistical Analyses

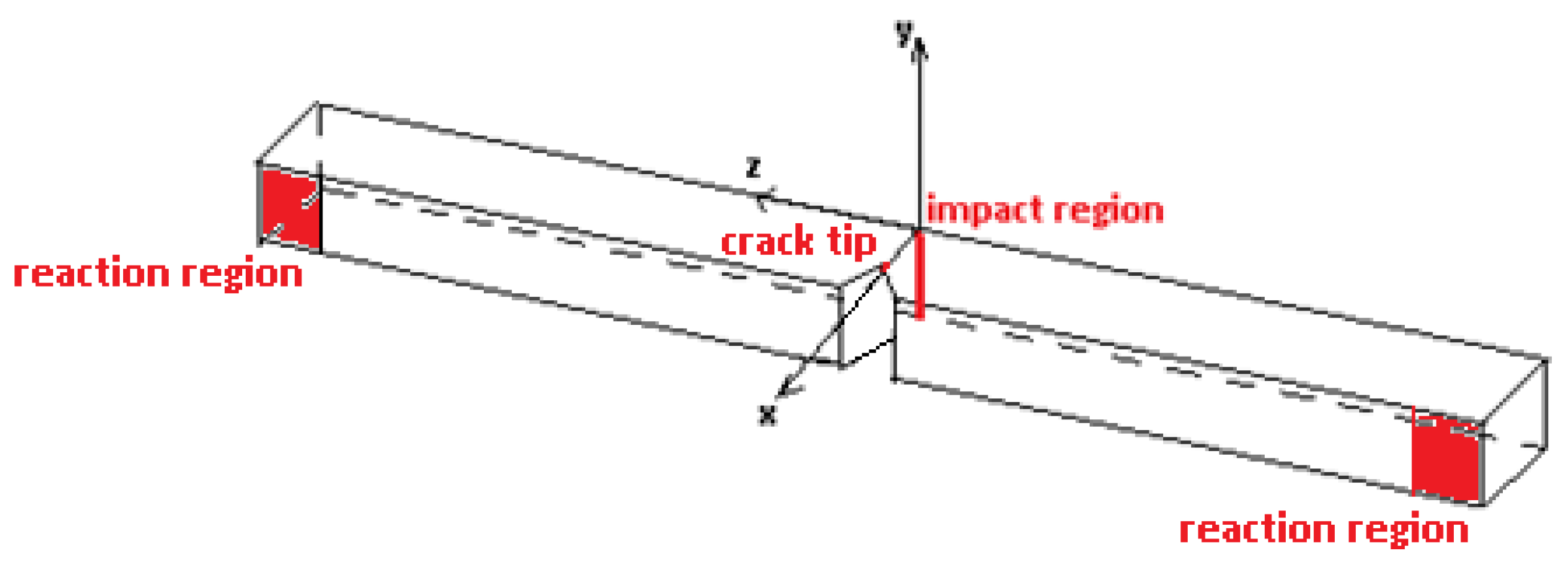

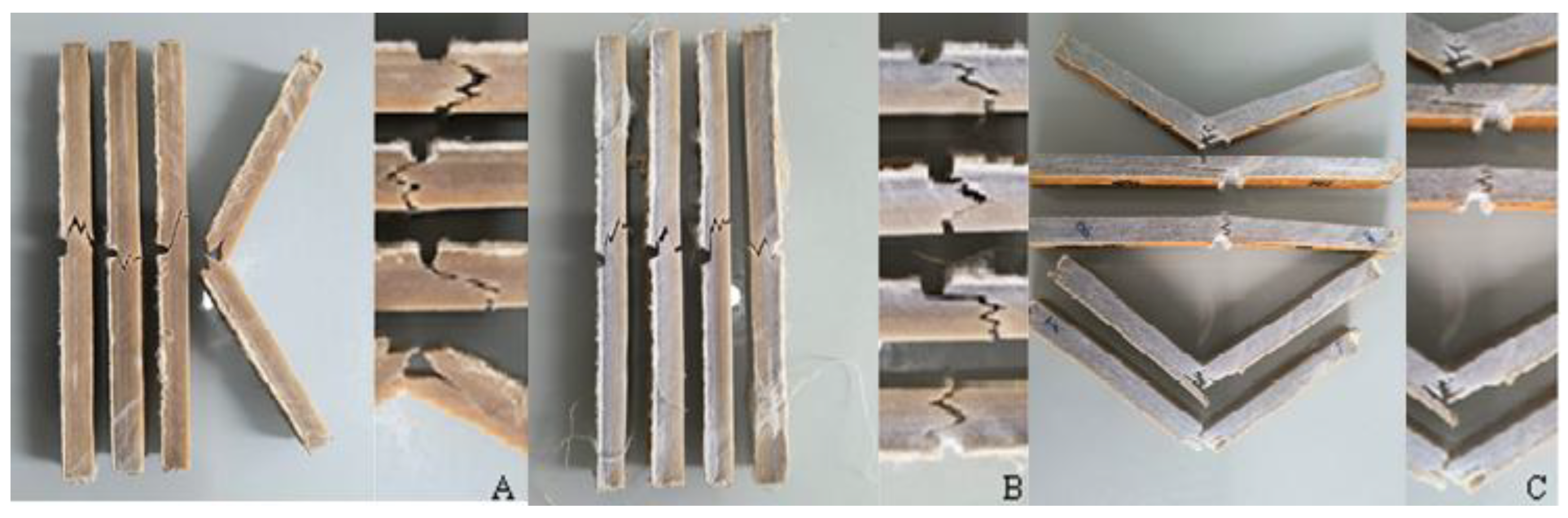

2.3. Intralaminar and Interlaminar Fracture Characterizations

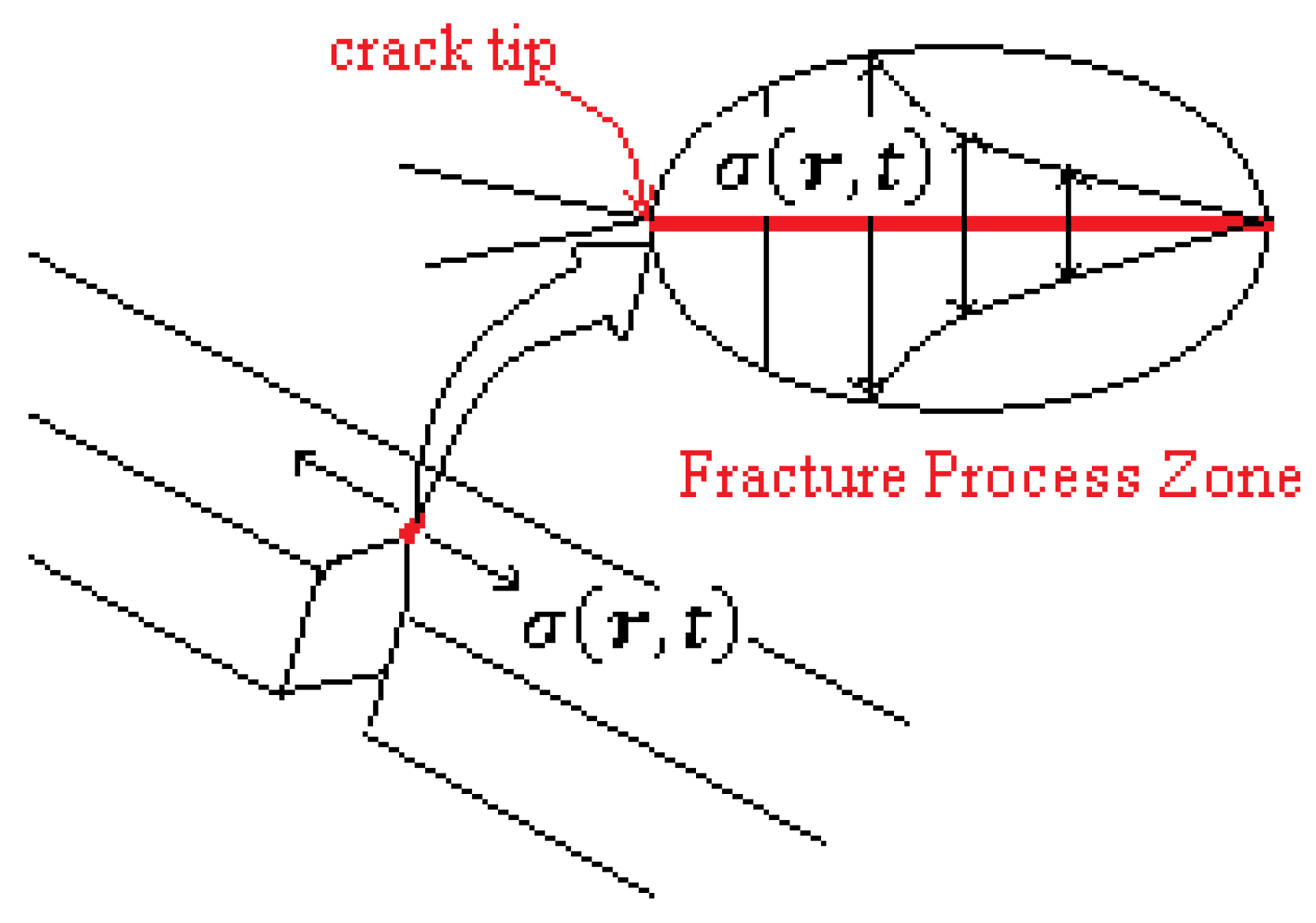

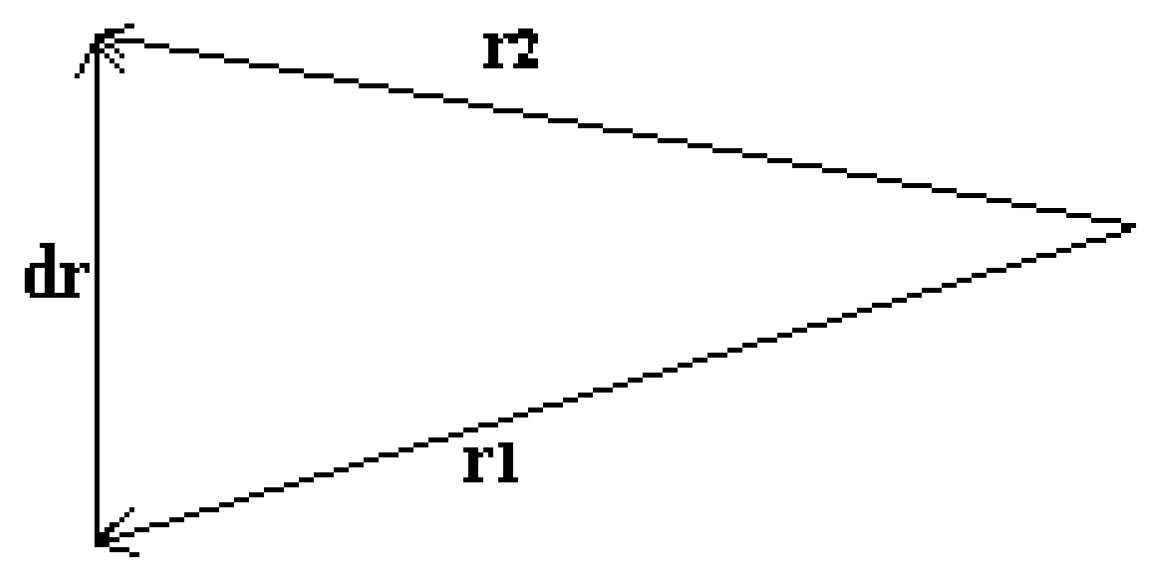

2.4. Hypotheses for the Relation Between the Quality of Interface and Fracture Energy

3. Results and Discussion

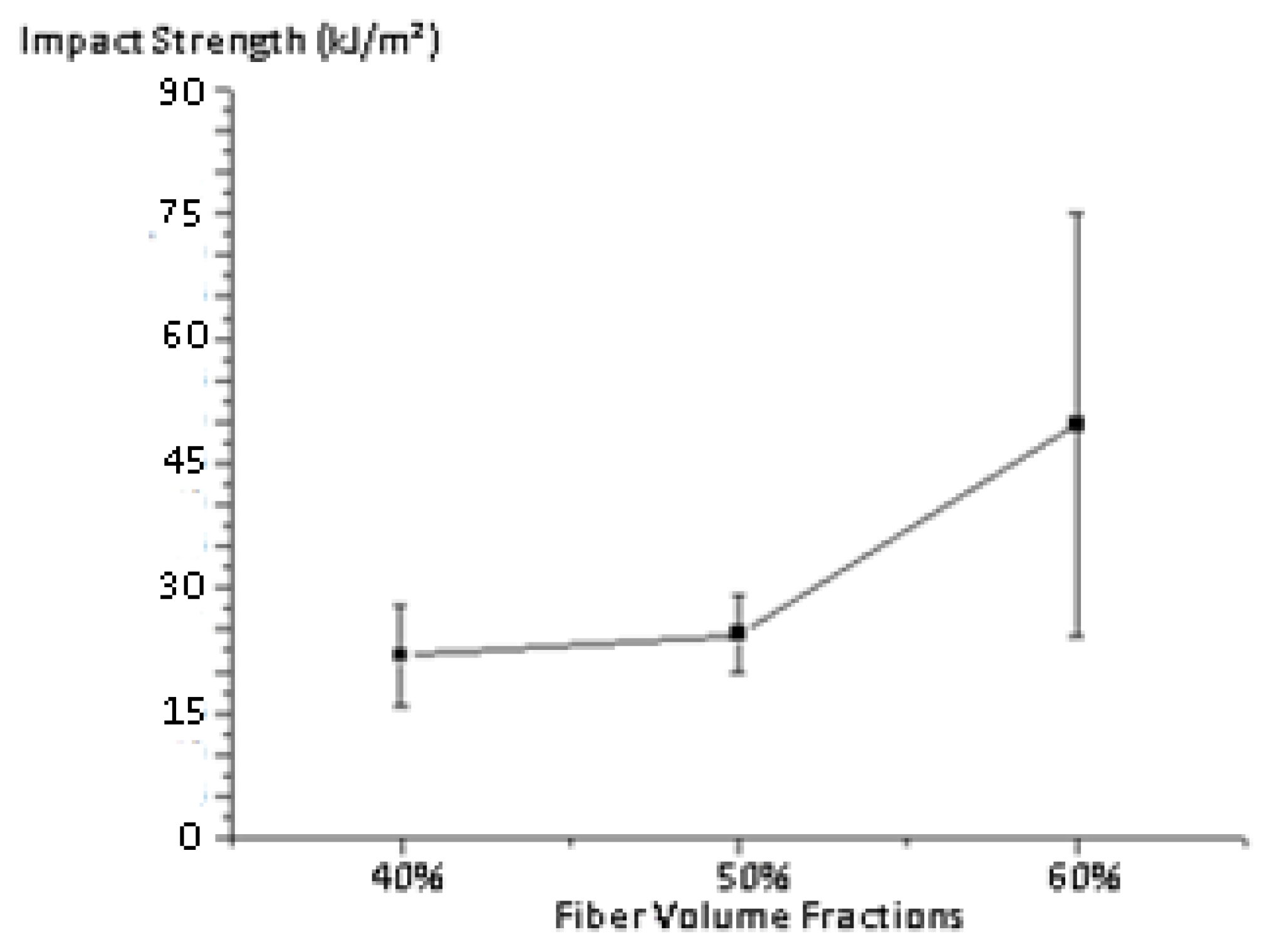

3.1. Results of the Charpy test in Intact Specimens

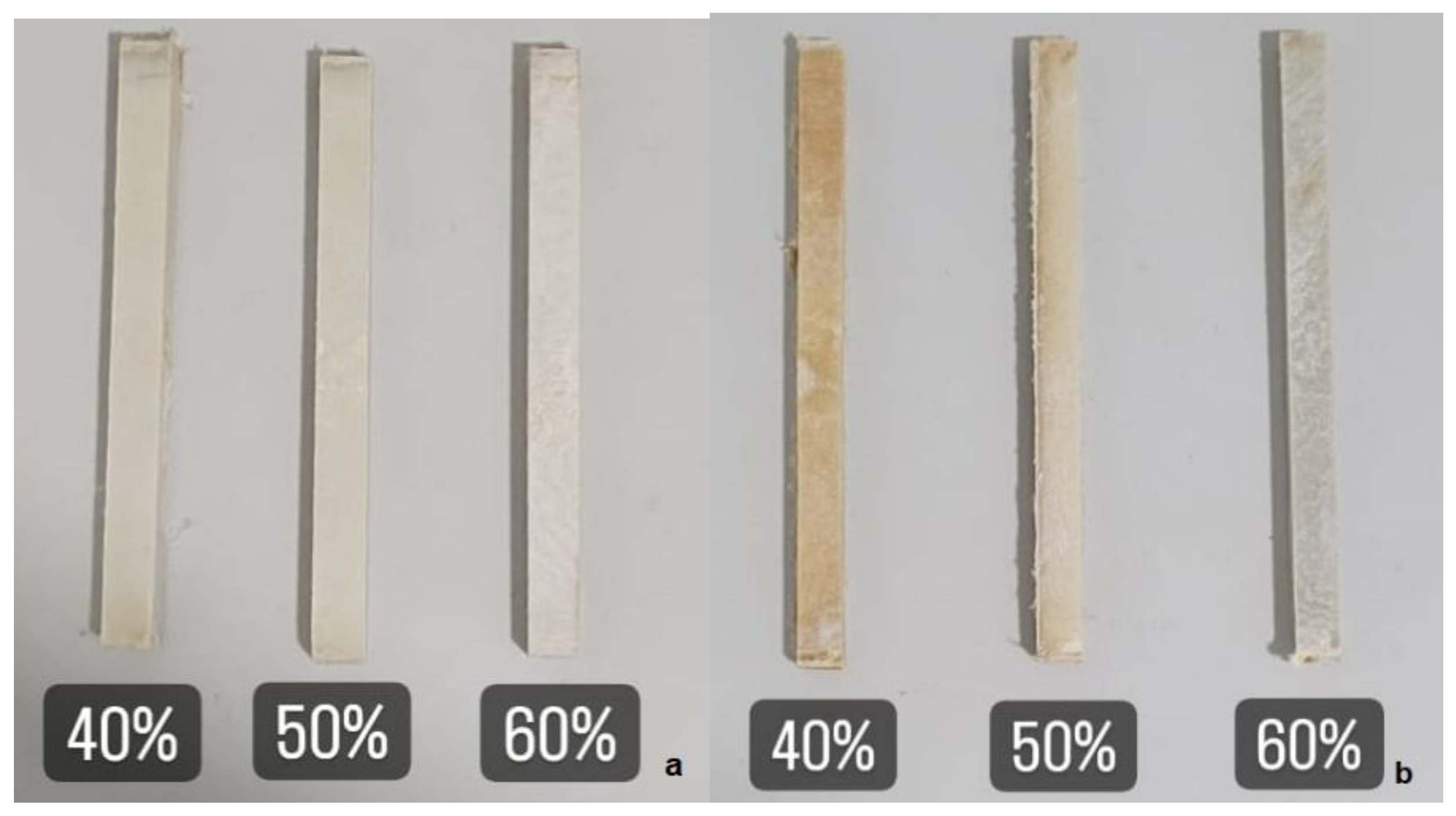

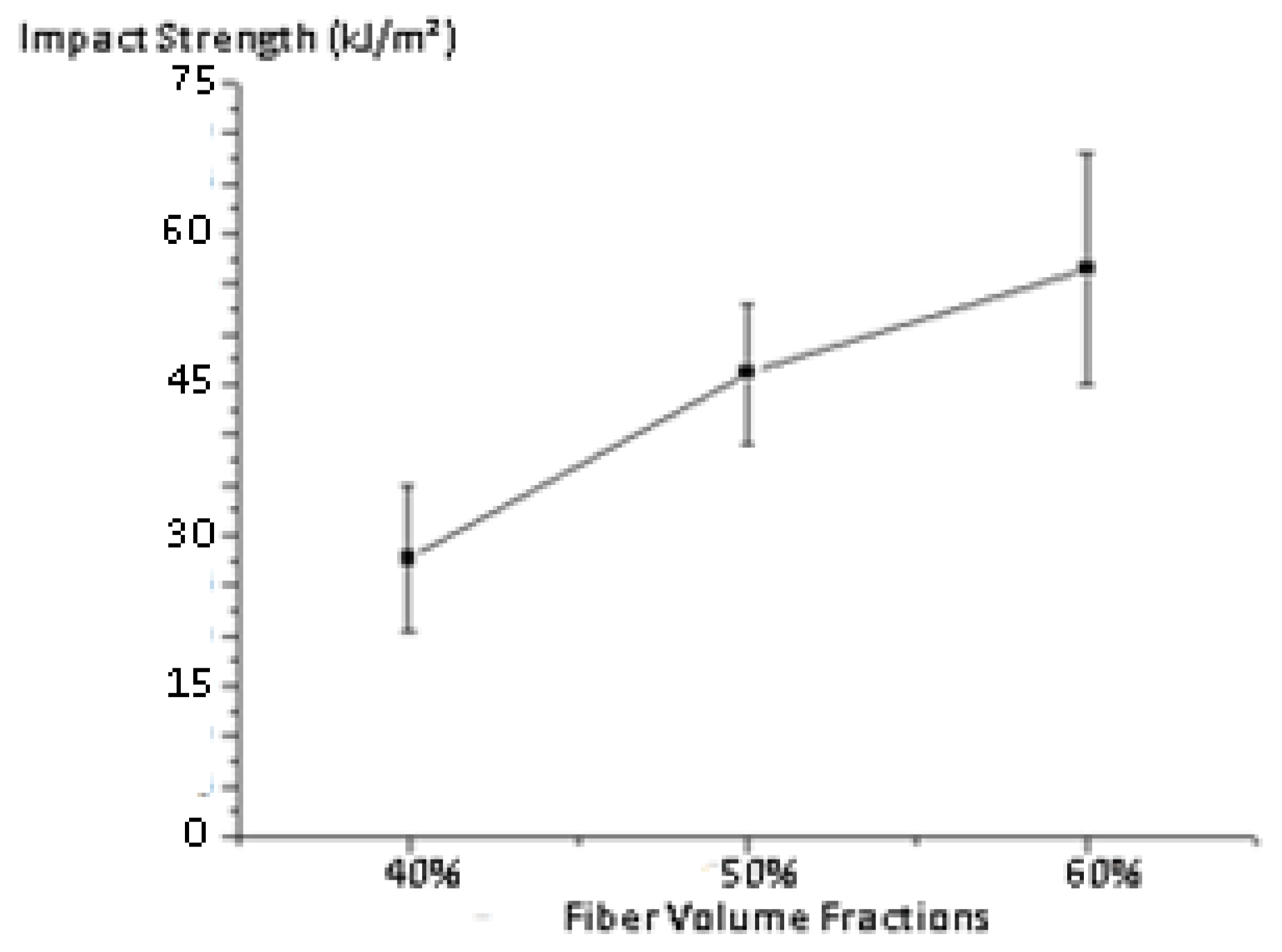

3.2. Results of the Charpy Test in Aged Specimens

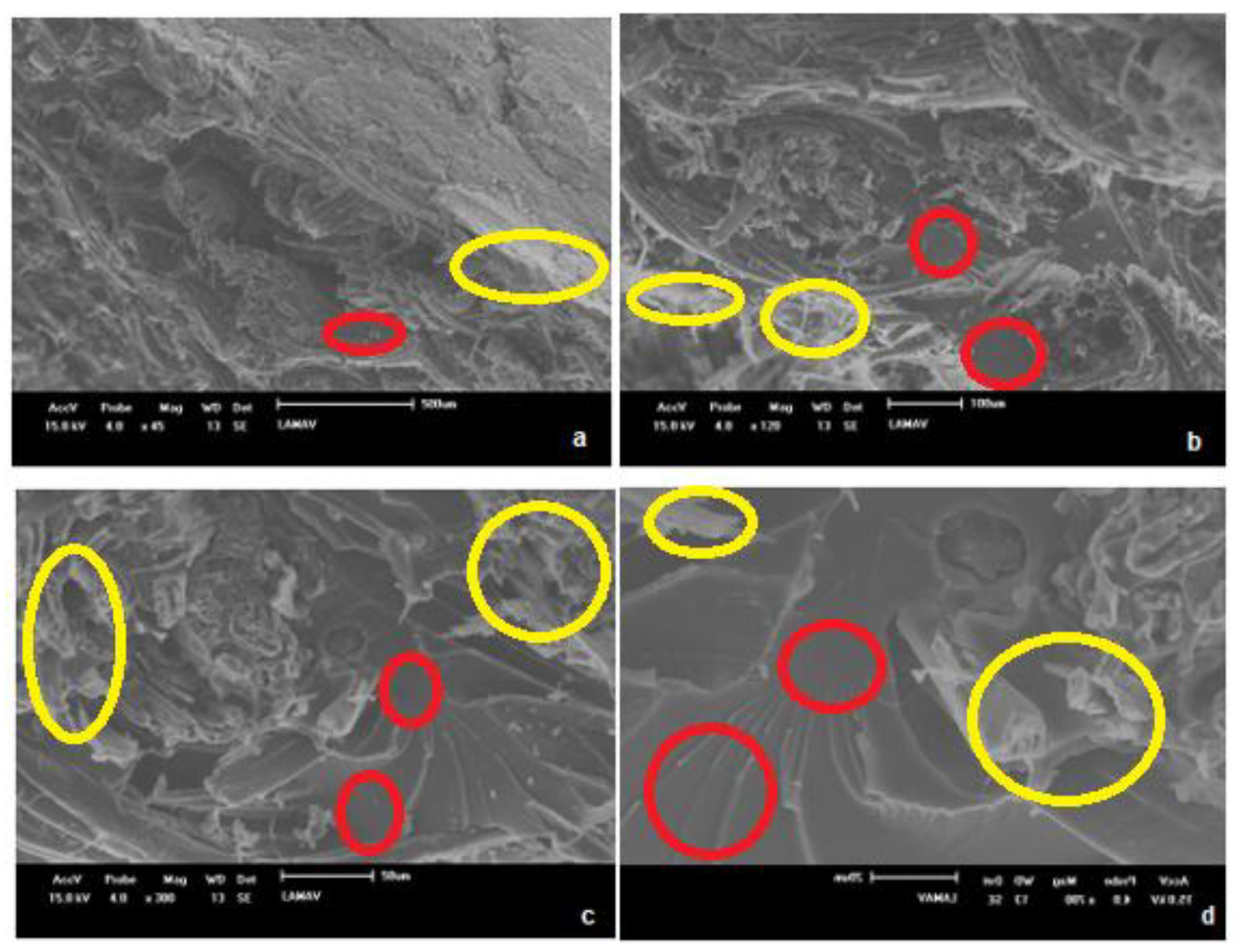

3.3. The Relation Between Interface Quality and Impact Fracture Energy

4. Conclusion

References

- Parvathaneni, P.P.; Madhav, V.V.V.; Chaitanya, C.S.; Spandana, V.V.; Saxena, K.K.; Garg, S.; Zeleke, M.A. Prediction of Impact Behaviour for Natural Fiber-Reinforced Composites Using the Finite Element Method. Composites and Advanced Materials 2022, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Blok, R.; Teuffel, P.; Lucas, S.S.; Moonen, F. Effect of Moisture in Flax Fiber on Viscoelastic Properties of the Manufactured Flax Fiber Reinforced Polymer by Fractional-Order Viscoelastic Model. Materials Today Communications 2024, 40, 110138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syduzzaman, Md.; Chowdhury, S.E.; Pritha, N.M.; Hassan, A.; Hossain, S. Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composites for Ballistic Protection: Design, Performance, and Challenges. Results in Materials 2024, 24, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, A.; Das, P.K.; Gupta, S.K.; Saha, A.; Rajendran, S.; Kamyab, H.; Yusuf, M. An Overview of Recent Trends and Future Prospects of Sustainable Natural Fiber-Reinforced Polymeric Composites for Tribological Applications. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 222, 119501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, A.; Reddy, P.V.; Kumar, V.S.; Buddi, T. Influence of the Stacking on Mechanical and Physical Properties of Jute/Banana Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Matrix Composite. Materials Today Proceedings 2023. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K.; Tewari, R.; Zafar, S.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. A Comprehensive Review of Various Factors for Application Feasibility of Natural Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Results in Materials 2022, 17, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppula, S.B.; Karachi, S.; P, V.K.; Borra, N.D.; Y, P.; Neigapula, V.S.N.; Rao, M.I.; S, H. Investigation into the Mechanical Characteristics of Natural Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites: Effects of Flax and e-Glass Reinforcement and Stacking Configuration. Materials Today Proceedings 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, A.M.; Adimass, S.A. Review on the Impact Behavior of Natural Fiber Epoxy Based Composites. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwash, B.; Shivakumar, N.D.; Sachidananda, K.B. Analytical Investigation of Green Composite Lamina Utilizing Natural Fiber to Strengthen PLA. Hybrid Advances 2024, 7, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Hossain, N.; Hasan, F.; Rahman, S.M.M.; Khan, S.; Saifullah, A.Z.A.; Chowdhury, M.A. Advances of Natural Fiber Composites in Diverse Engineering Applications – A Review. Applications in Engineering Science 2024, 18, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.D.; Yadav, S.P.S.; Ravindra, N.; D’Mello, G.; Manjunatha, G. Study the Effect of Fracture Toughness on Hybrid Composite for Automotive Application. Materials Today Proceedings 2023, 92, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, M.R; Nurfaizey, A.H.; Tamaldin, N.; Nordin, M.N.A. Natural fiber polymer composites: Utilization in aerospace engineering. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Composites Science and Engineering. Biomass, Biopolymer-Based Materials, and Bioenergy. Woodhead Publishing. Cambridge. 2019.

- Tuli, N.T.; Khatun, S.; Rashid, A.B. Unlocking the Future of Precision Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Exploration of 3D Printing with Fiber-Reinforced Composites in Aerospace, Automotive, Medical, and Consumer Industries. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, C.M.; Santos, T.F.; Rao, H.J.; Silva, F.H.V.A.; Rangappa, S.M.; Boonyasopon, P.; Siengchin, S.; Souza, D.F.S.; Nascimento, J.H.O. A Bibliometric Review on Applications of Lignocellulosic Fibers in Polymeric and Hybrid Composites: Trends and Perspectives. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrens, A.; Bonde, A.; Sun, H.; Wittig, N.K.; Hammershøj, H.C.D.; Batista, G.M.F.; Sommerfeldt, A.; Frølich, S.; Birkedal, H.; Skrydstrup, T. Catalytic Disconnection of C–O Bonds in Epoxy Resins and Composites. Nature 2023, 617, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, K.; Schritt, H.; Pleissner, D.; Kaur, G.; Brar, S.K. Biodegradable Green Composites: It’s Never Too Late to Mend. Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2021, 30, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniyasamy, S.; Dada, O.E. Recycling of Plastics and Composites Materials and Degradation Technologies for Bioplastics and Biocomposites. In Elsevier eBooks; 2021; pp. 311–333.

- Le Bourhis, E.; Touchard, F. Mechanical Properties of Natural Fiber Composites. Reference Module in Materials Science and Materials Engineering, Elsevier, 2021.

- Tan, Y.; Mei, Q.; Luo, X. The Influence of Interface Morphology on the Mechanical Properties of Binary Laminated Metal Composites Fabricated by Hierarchical Roll-Bonding. Metals 2025, 15, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Wang, C.; Deng, K.; Nie, K.; Liang, W.; Wu, Y. Effect of interface on mechanical properties and formability of Ti/Al/Ti laminated composites, Journal of Materials Research and Technology, Volume 14, 2021, Pages 1655-1669. [CrossRef]

- Woigk, W.; Fuentes, C.A.; Rion, J.; Hegemann, D.; Van Vuure, A.W.; Dransfeld, C.; Masania, K. Interface Properties and Their Effect on the Mechanical Performance of Flax Fibre Thermoplastic Composites. Composites Part a Applied Science and Manufacturing 2019, 122, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, W.; Zhuang, W.; Xing, B.; Zhou, Q.; Xia, Y. Finite Element Method of a Progressive Intralaminar and Interlaminar Damage Model for Woven Fibre Laminated Composites under Low Velocity Impact. Materials & Design 2022, 223, 111256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedifar, M.; Toudeshky, H.H. The Effect of Interlaminar and Intralaminar Damage Mechanisms on the Quasi-Static Indentation Strength of Composite Laminates. Applied Composite Materials 2023, 30, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 4787 – Laboratory Glass and Plastic Ware – Volumetric Instruments – Methods for testing of capacity and use. 2021.

- Uppal, N.; Pappu, A.; Gowri, V.K.S.; Thakur, V.K. Cellulosic Fibres-Based Epoxy Composites: From Bioresources to a Circular Economy. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 182, 114895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 179-1 – Plastic Determination of Charpy Impact Properties, part 1: Non-instrumented Impact Test. 2010.

- Machado, M. V. F., Lopes, F. P. D., Simonassi, N. T., Monteiro, S. N. Ensaios de Impacto em Compósitos Epóxi com Média e Alta Frações Volumétricas Teóricas de Tecido de Rami e uma Análise de Fraturas à Luz do Princípio de Hamilton. ABM Proceedings 2024, p. 321–332. [CrossRef]

- ASTM-G53/154 – Standard Practice for Operating Fluorescent Light Apparatus for UV Exposure of Nonmetallic Materials. 2017.

- ASTM D 5208 - Standard Practice for Fluorescent Ultraviolet (UV) Exposure of Photodegradable Plastics. 2022.

- ADEXIM-COMEXIM – Correlação Entre o Tempo Real de Intemperismo e a Ação do Sistema C-UV com Base na ASTM-G53/154. 2000.

- Wu, X.; Li, X.; Sun, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Z. Fracture Process Zone and Fracture Energy of Heterogeneous Soft Materials. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 2024, 105997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, S.M.H.; Fakoor, M.; Mirzavand, B. A Novel Mixed Mode Fracture Criterion for Functionally Graded Materials Considering Fracture Process Zone. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics 2024, 134, 104710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, I.O.; Marsavina, L.; Dopeux, J.; Metrope, M. A New Approach for Fracture Process Zone Evaluation. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics 2024, 132, 104495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, S.; Seryo, Y.; Kimura, M.; Hojo, M. Mesoscale Mechanism of Damage in Fracture Process Zone of CFRP Laminates Simulated with Triaxial Stress State-Dependent Constitutive Equation of Matrix Resin. Composites Science and Technology 2024, 257, 110837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghami, A.; Wang, Q.; Tricarico, M.; Ciavarella, M.; Li, Q.; Papangelo, A. Bulk and Fracture Process Zone Contribution to the Rate-Dependent Adhesion Amplification in Viscoelastic Broad-Band Materials. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids 2024, 193, 105844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, P.; Xie, H.; Hu, J.; Li, M.; Ren, L.; Li, C. Anisotropic Fracture Behavior and Corresponding Fracture Process Zone of Laminated Shale through Three-Point Bending Tests. Journal of Rock Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Li, D.; Luo, Q. A Multiscale Nonlinear Fracture Model for Staggered Composites to Reveal the Toughening Effect of Process Zone. Composites Science and Technology 2023, 241, 110132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Takeda, S.-I.; Wisnom, M.R. Investigation of Fracture Process Zone Development in Quasi-Isotropic Carbon/Epoxy Laminates Using in Situ and Ex Situ X-Ray Computed Tomography. Composites Part a Applied Science and Manufacturing 2022, 166, 107395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, H.; Luo, S. Size Effect Model of Nominal Tensile Strength with Competing Mechanisms between Maximum Defect and Fracture Process Zone (CDF Model) for Quasi-Brittle Materials. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 399, 132538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.A.; Lessel, A.M.; Williams, B.A.; Horner, W.M.; Ranade, R. Fracture Process Zone Characterizations of Multi-Scale Fiber Reinforced Cementitious Composites. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 408, 133713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, B. A Phase-Field Framework for Modeling Multiple Cohesive Fracture Behaviors in Laminated Composite Materials. Composite Structures 2024, 347, 118458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Zhao, C.; An, L. A Micromechanics Perspective on the Intralaminar and Interlaminar Damage Mechanisms of Composite Laminates Considering Ply Orientation and Loading Condition. Composite Structures 2024, 347, 118454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.M.; Coelho, C.A.C.P.; Reis, P.N.B. Numerical Predictions of Intralaminar and Interlaminar Damage in Thin Composite Shells Subjected to Impact Loads. Thin-Walled Structures 2023, 192, 111148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, W.; Zhuang, W.; Xing, B.; Zhou, Q.; Xia, Y. Finite Element Method of a Progressive Intralaminar and Interlaminar Damage Model for Woven Fibre Laminated Composites under Low Velocity Impact. Materials & Design 2022, 223, 111256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Gao, Y.; Cheng, L.; Liu, W.; Cui, H.; Suo, T. Dynamic Tensile Intralaminar Fracture and Continuum Damage Evolution of 2D Woven Composite Laminates at High Loading Rate. Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics 2024, 104731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, P.; Pulungan, D.; Tao, R.; Lubineau, G. An Experimental Study on the Influence of Intralaminar Damage on Interlaminar Delamination Properties of Laminated Composites. Composites Part a Applied Science and Manufacturing 2020, 131, 105783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Palumbo, C.; Riccio, A. The Role of Intralaminar Damages on the Delamination Evolution in Laminated Composite Structures. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Naya, F.; Yang, L.; Chang, T.; Falzon, B.G.; Zhan, L.; Molina-Aldareguía, J.M.; González, C.; Llorca, J. The Role of Interfacial Properties on the Intralaminar and Interlaminar Damage Behaviour of Unidirectional Composite Laminates: Experimental Characterization and Multiscale Modelling. Composites Part B Engineering 2017, 138, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espadas-Escalante, J.J.; Van Dijk, N.P.; Isaksson, P. The Effect of Free-Edges and Layer Shifting on Intralaminar and Interlaminar Stresses in Woven Composites. Composite Structures 2017, 185, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naya, F.; Pappas, G.; Botsis, J. Micromechanical Study on the Origin of Fiber Bridging under Interlaminar and Intralaminar Mode I Failure. Composite Structures 2018, 210, 877–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moura, M.F.S.F.; Campilho, R.D.S.G.; Amaro, A.M.; Reis, P.N.B. Interlaminar and Intralaminar Fracture Characterization of Composites under Mode I Loading. Composite Structures 2009, 92, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.; Czabaj, M.W. A New Test for Characterization of Interlaminar Tensile Strength of Tape-Laminate Composites. Composites Part a Applied Science and Manufacturing 2023, 176, 107868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Fiber theoretical volume fraction | 40% | 50% | 60% |

| Number of plies | 70 | 87 | 105 |

| %Volfiber | Energy (J) | Notch Toughness (J/m) | Impact Strength (kJ/m²) |

| 40% | 1,28 0,35 | 139,91 37,67 | 21,83 6,08 |

| 50% | 1,48 0,36 | 158,53 36,10 | 24,45 4,59 |

| 60% | 3,86 1,87 | 414,09 200,24 | 49,67 25,44 |

| %Volfiber | Energy (J) | Notch Toughness (J/m) | Impact Strength (kJ/m²) |

| 40% | 2,31 0,77 | 231,11 76,60 | 27,62 7,25 |

| 50% | 3,54 0,61 | 354,40 61,12 | 46,11 6,59 |

| 60% | 4,55 1,18 | 455,00118,22 | 56,47 11,55 |

| 40% intact | 50% intact | 60% intact | 40% aged | 50% aged | 60% aged | |

| 40% intact | 0,4621 | 0,0003139 | 0,1971 | 9,552.10-5 | 1,398.10-6 | |

| 50% intact | 0,4621 | 0,004672 | 0,5603 | 0,001661 | 5,1.10-5 | |

| 60% intact | 0,0003139 | 0,004672 | 0,03398 | 0,6992 | 0,2031 | |

| 40% aged | 0,1971 | 0,5603 | 0,03398 | 0,001455 | 0,0009424 | |

| 50% aged | 9,522.10-5 | 0,001661 | 0,6992 | 0,01455 | 0,3876 | |

| 60% aged | 1,398.10-6 | 5,1.10-5 | 0,2031 | 0,0009424 | 0,3876 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).