Submitted:

13 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

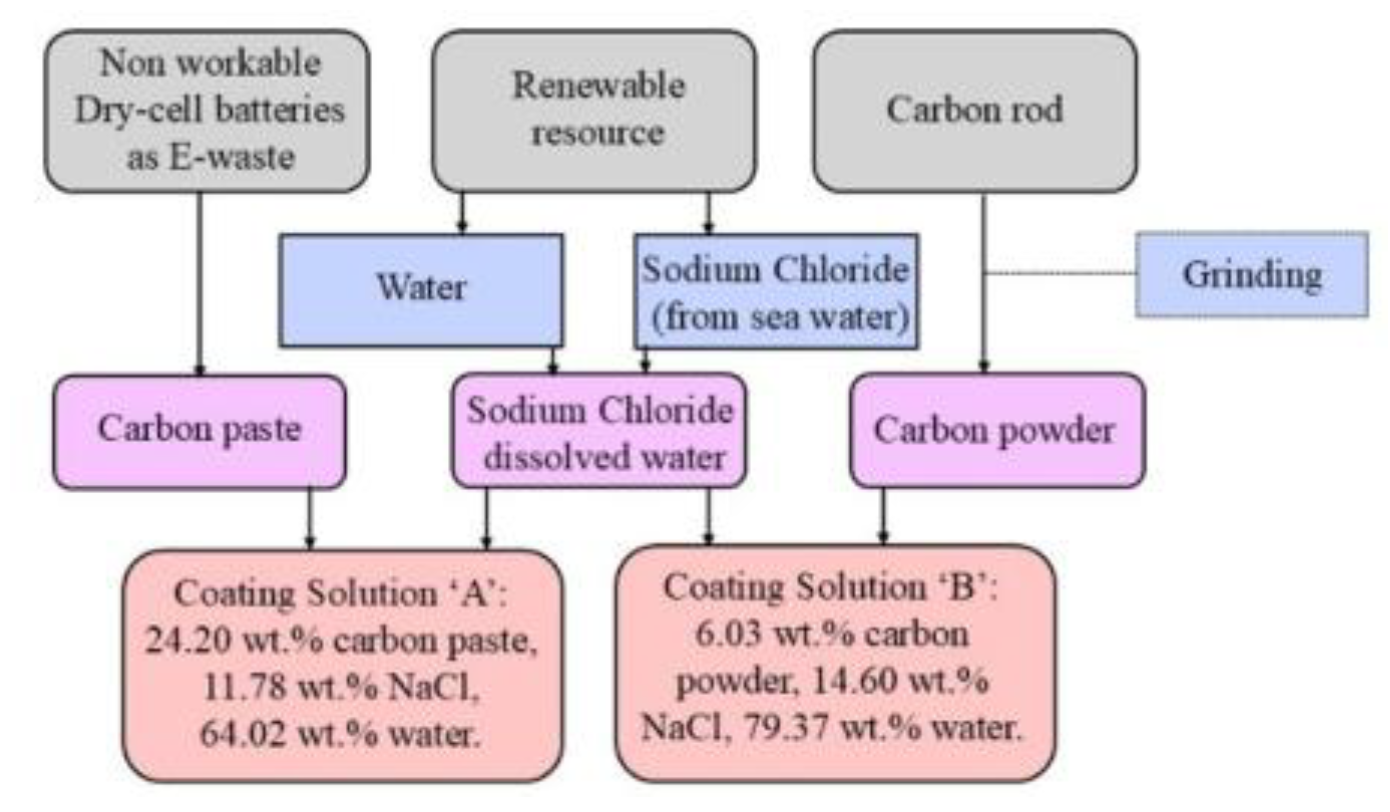

2.2. Preparation of Coating Solution

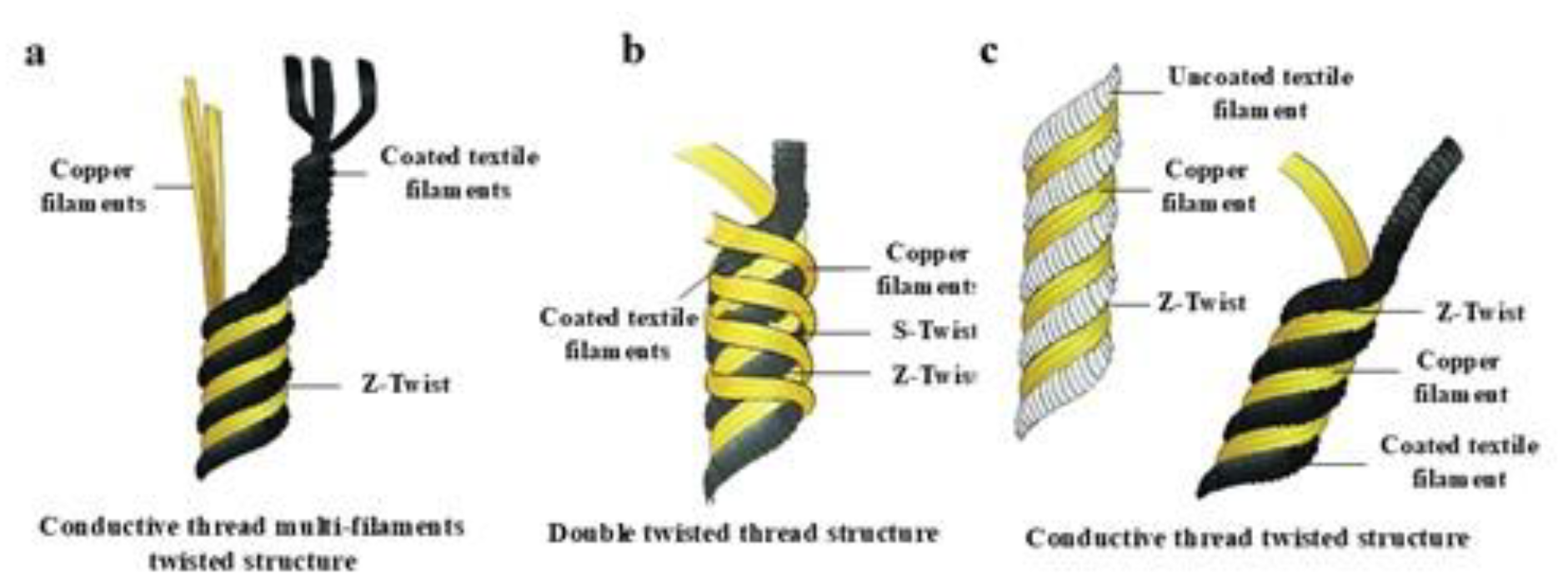

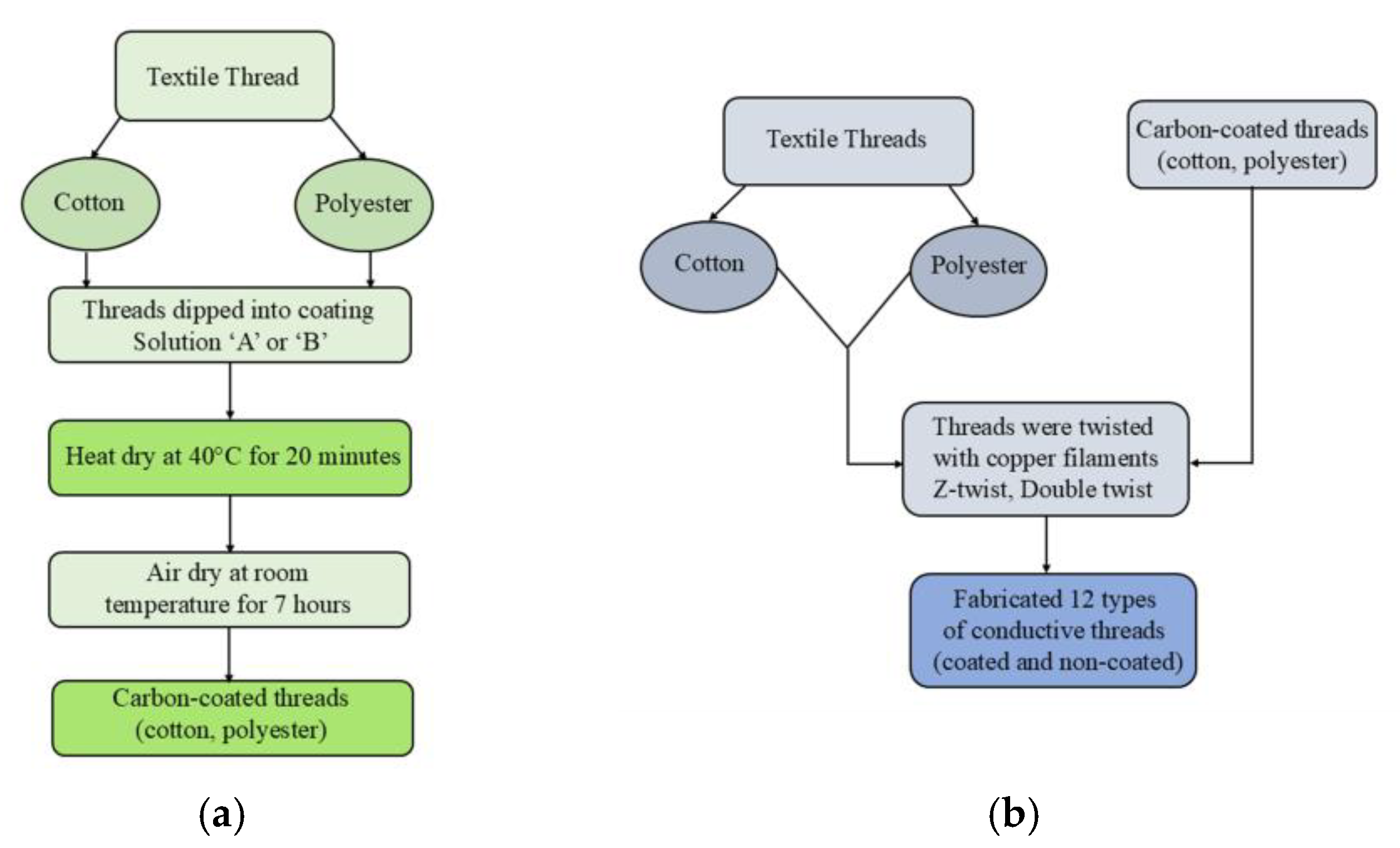

2.3. Preparation of Conductive Threads

3. Results and Discussion

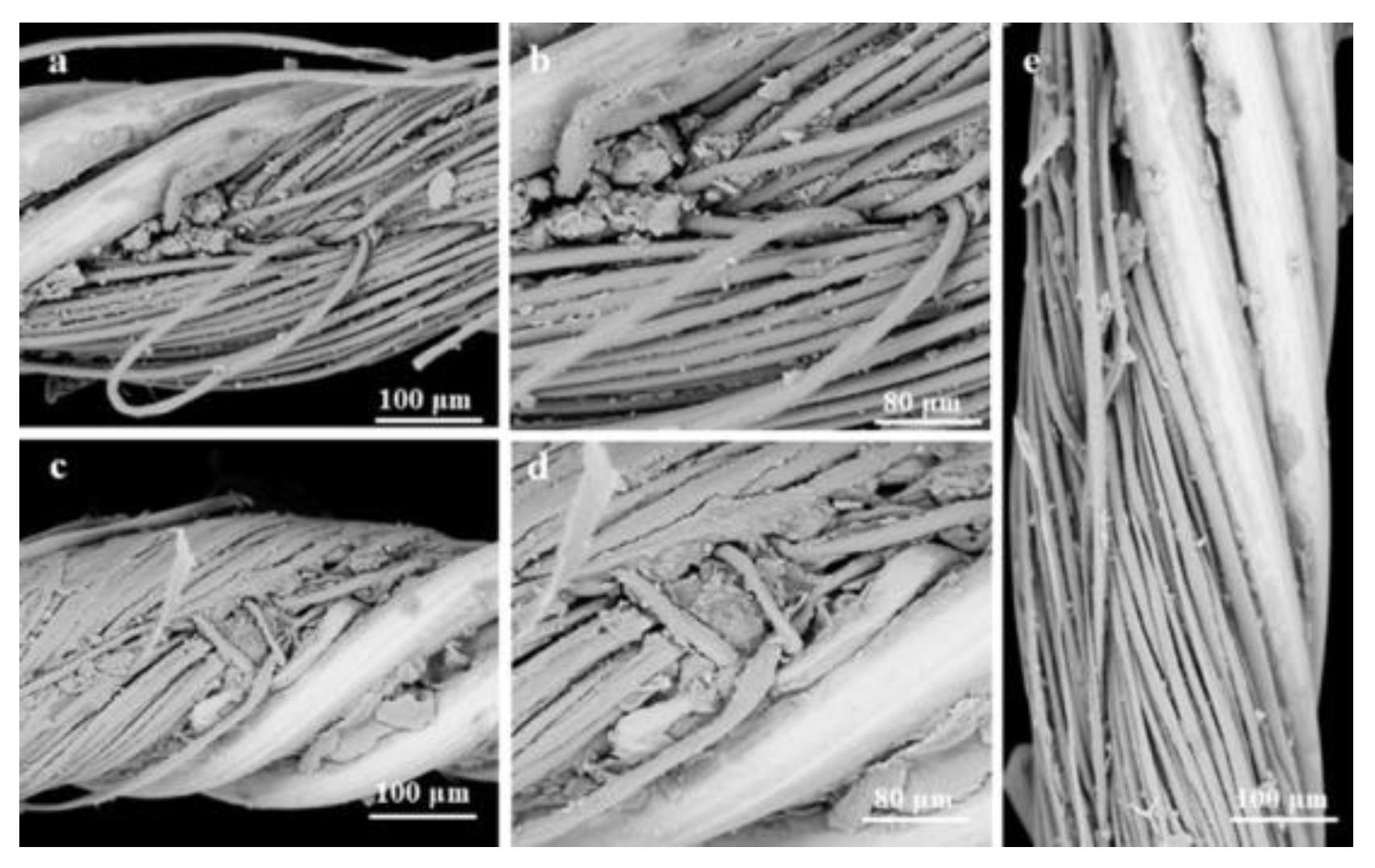

3.1. Surface Morphology Analysis of Conductive Threads Using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

3.2. Electrical resistance and thread count measurement

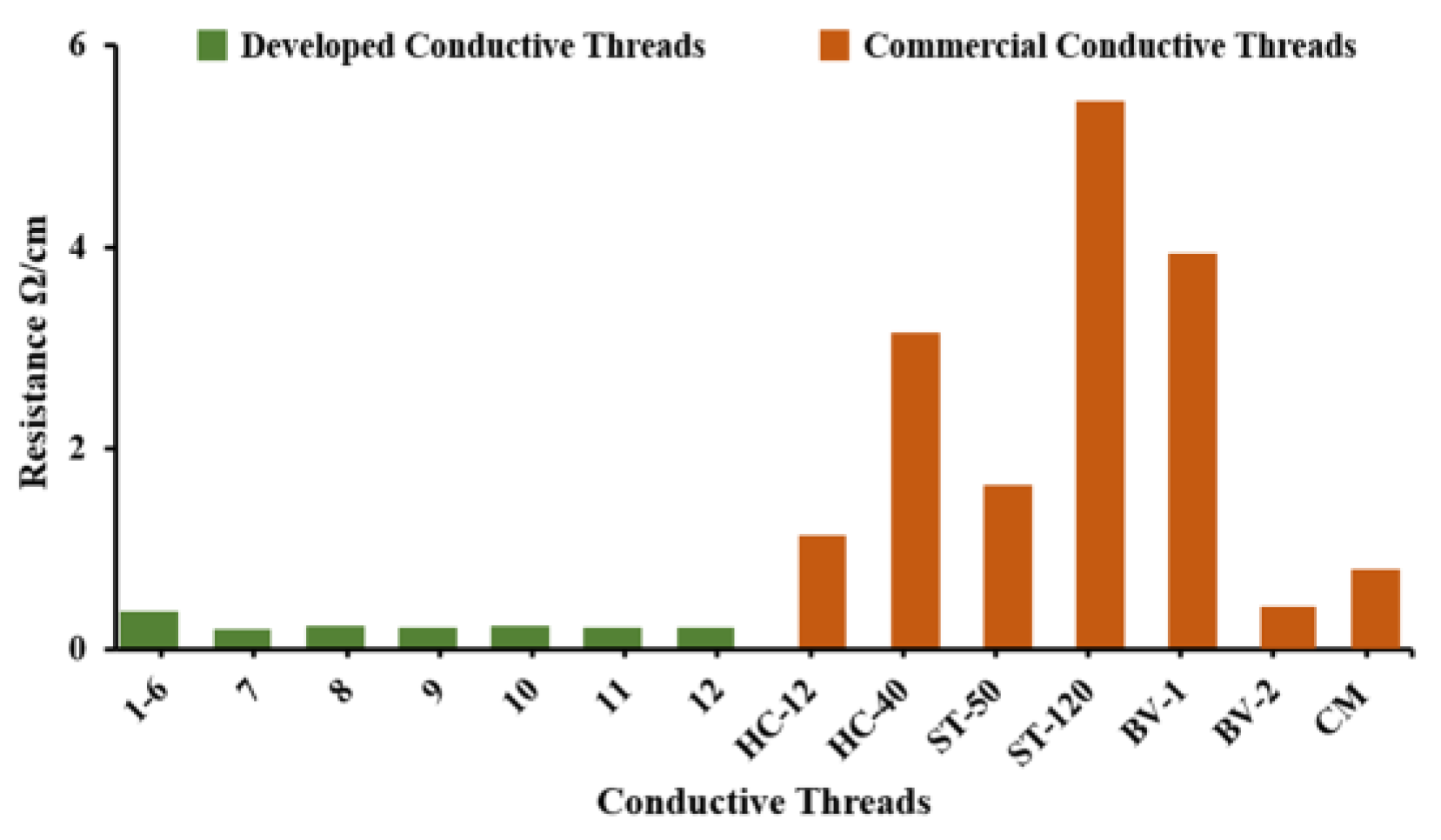

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Conductive Threads Resistances with Commercial Conductive Threads

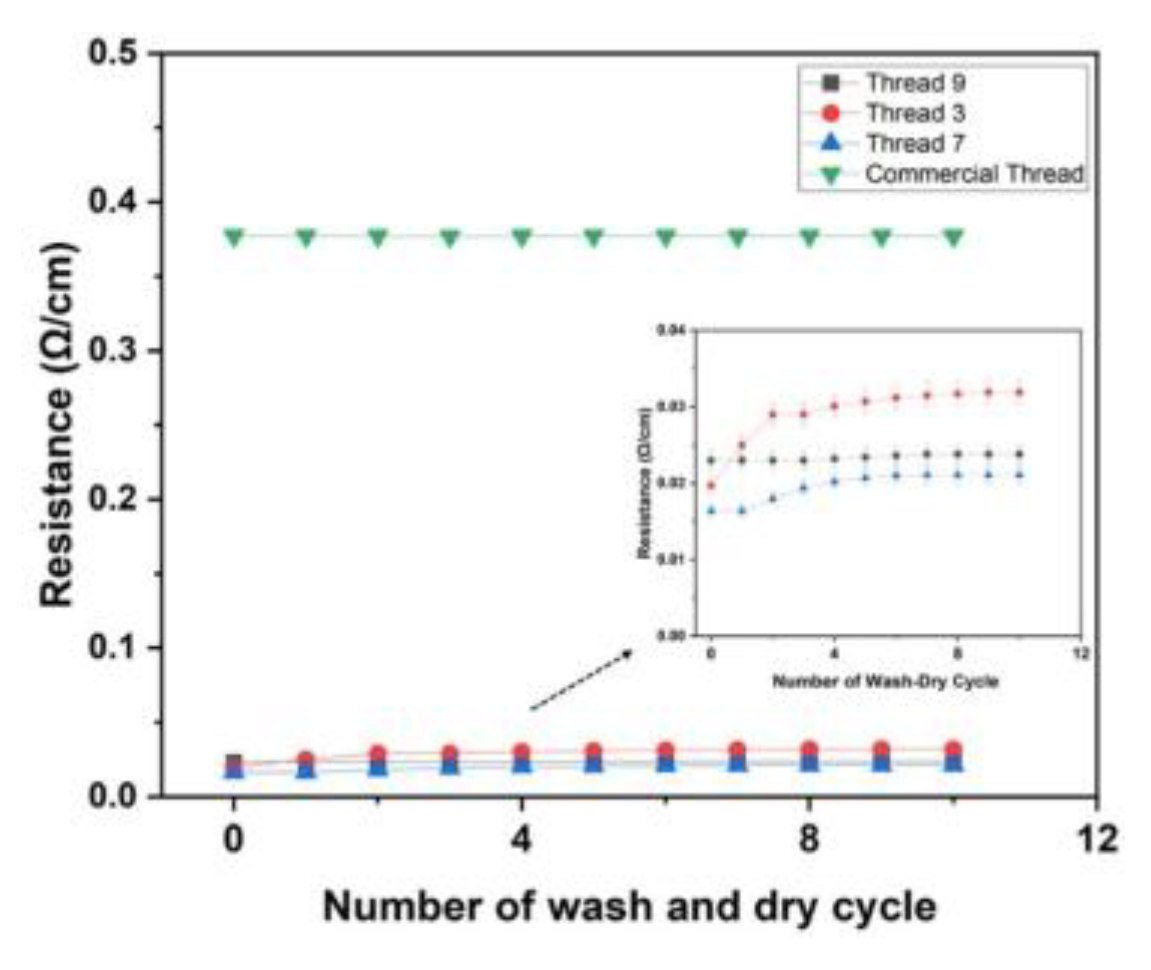

3.4. Resistance Dynamics of Conductive Threads Under Wash-Dry Cycles

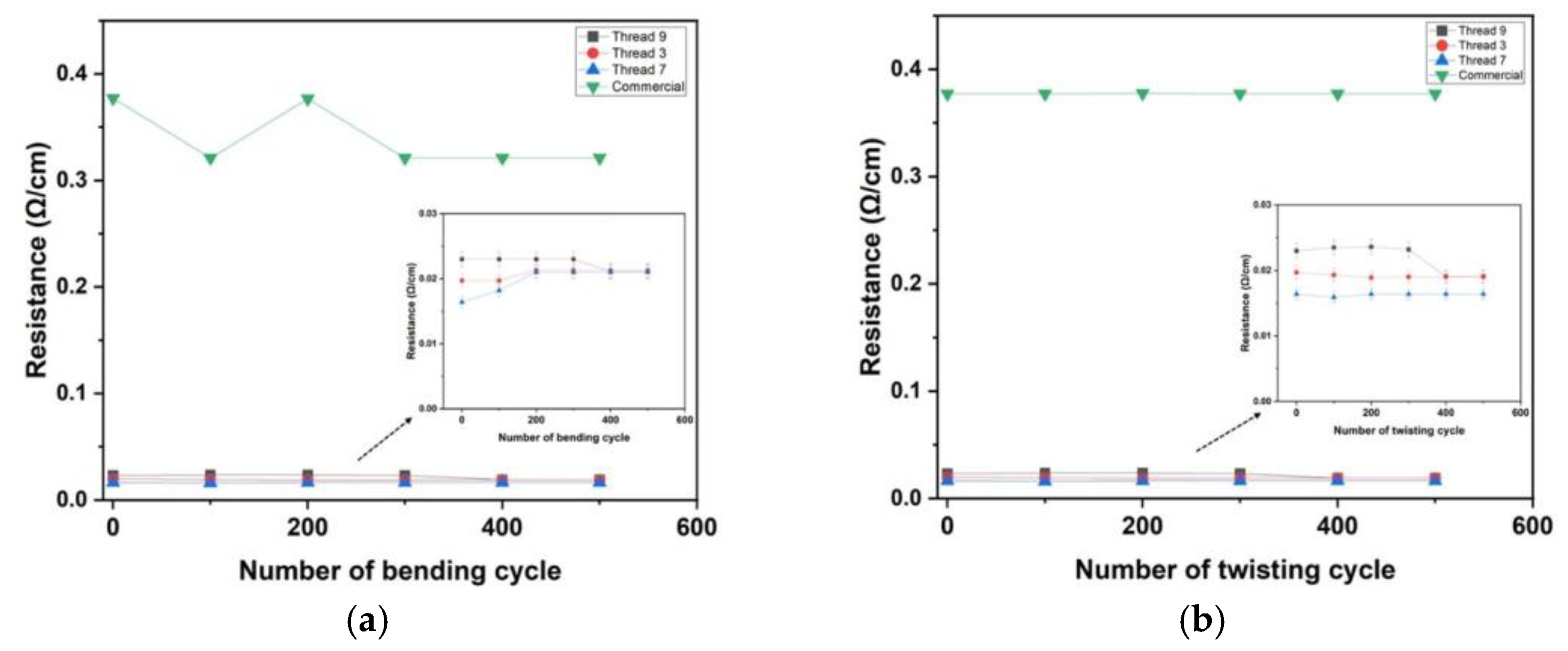

3.5. Mechanical-Electrical Stability of Conductive Threads Under Bending and Twisting

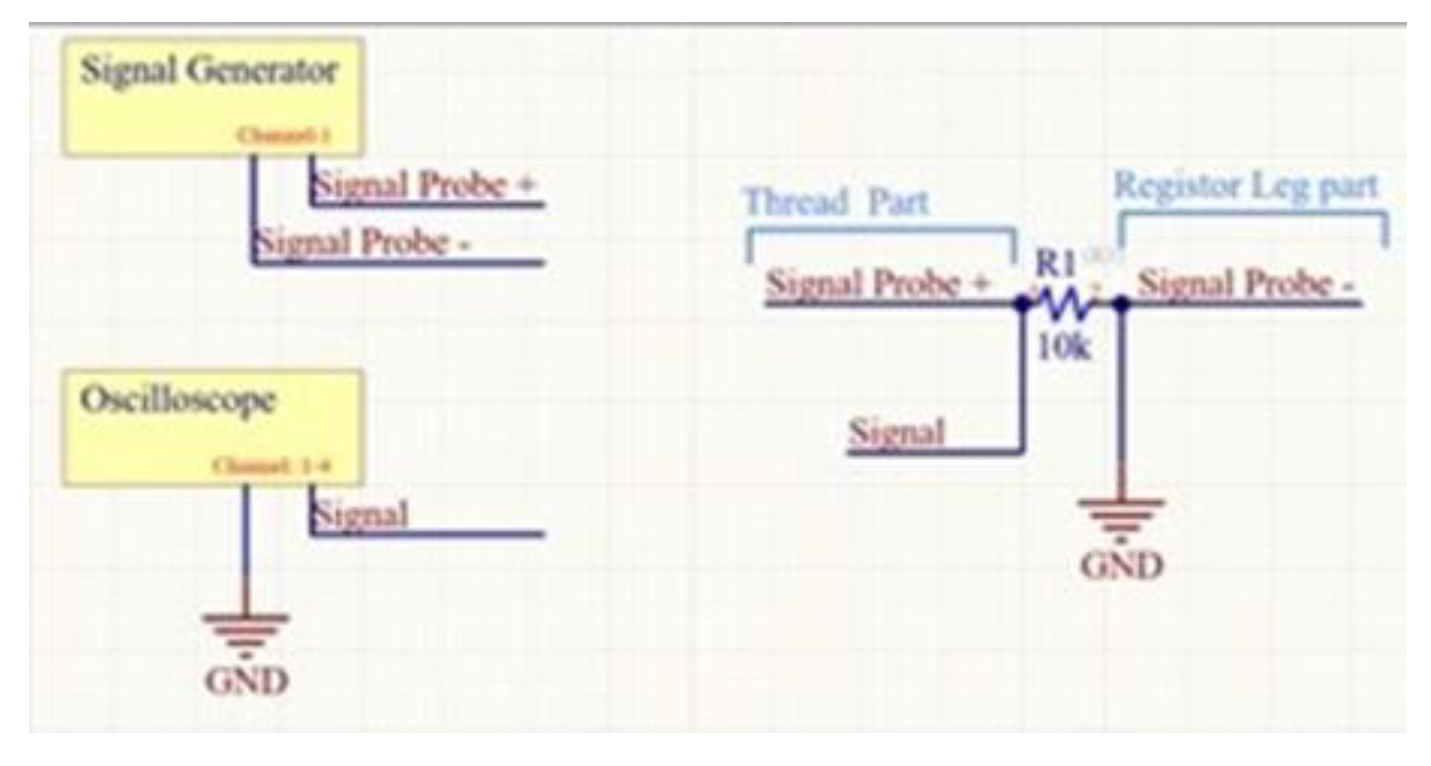

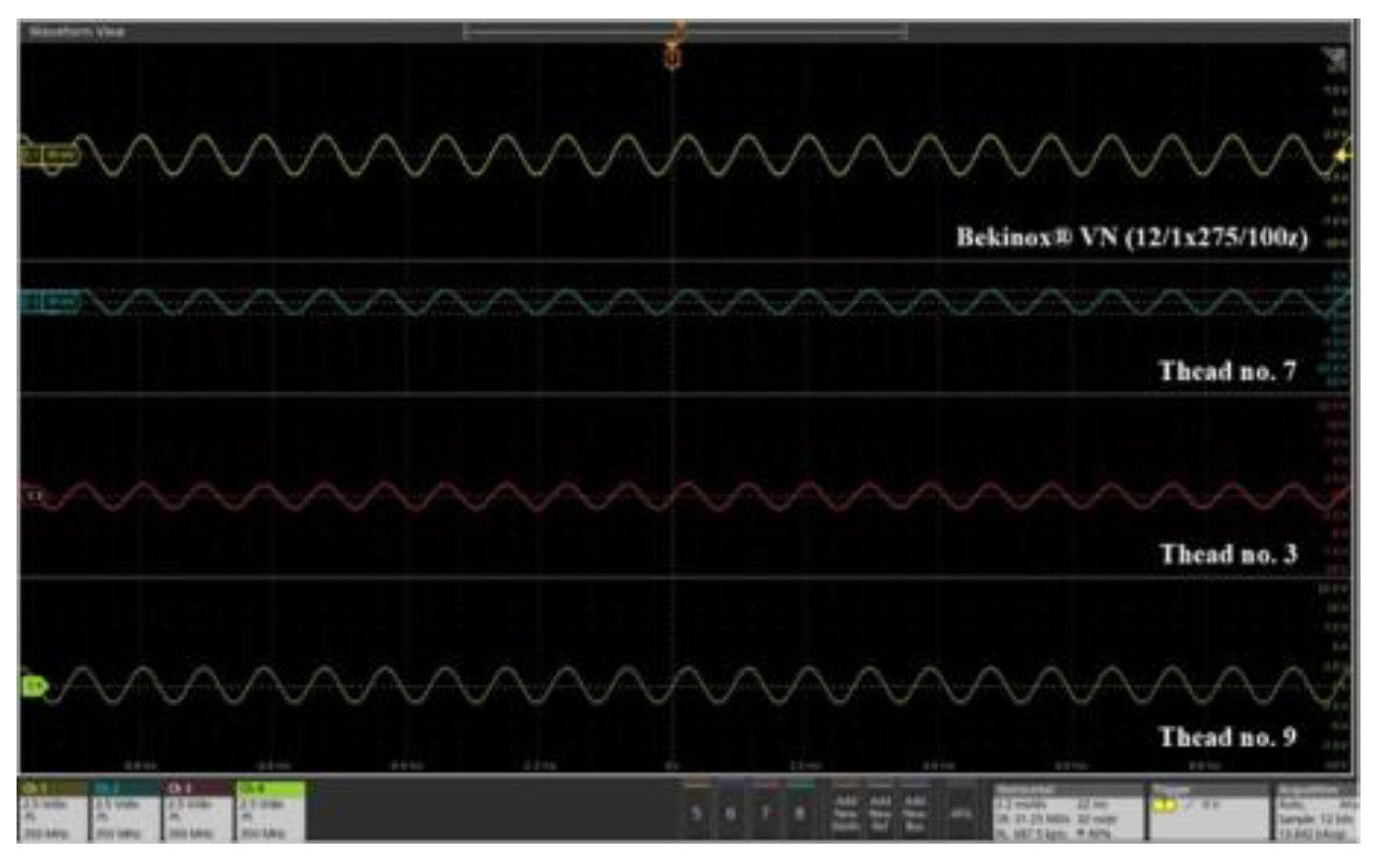

3.6. Signal’s Amplitude & Strength Analysis

3.7. Overall Performance Evaluation

3.8. Conductive Threads: Future Textiles

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, H.; Wang, D.; Sun, G.; Hinestroza, J.P. Assembly of metal nanoparticles on electrospun nylon 6 nanofibers by control of interfacial hydrogen-bonding interactions. Chemistry of Materials 2008, 20, 6627–6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, L.; Guo, Z.H.; Zhang, P.; Wan, J.; Pu, X.; Wang, Z.L. Stretchable, self-healing, conductive hydrogel fibers for strain sensing and triboelectric energy-harvesting smart textiles. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherenack, K.; Van Pieterson, L. Smart textiles: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Applied Physics 2012, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Guo, B.; Cruz, M.A.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Q.; Lin, Z.; Xu, F.; Xu, F.; Chen, X.; Cai, D. Colorful conductive threads for wearable electronics: transparent Cu–Ag nanonets. Advanced Science 2022, 9, 2201111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhashmi Alamer, F.; Almalki, G.A.; Althagafy, K. Advancements in Conductive Cotton Thread-Based Graphene: A New Generation of Flexible, Lightweight, and Cost-Effective Electronic Applications. Journal of Composites Science 2023, 7, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam Po Tang, S.; Stylios, G. An overview of smart technologies for clothing design and engineering. International Journal of Clothing Science and Technology 2006, 18, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukada, S.; Nakashima, H.; Torimitsu, K. Conductive polymer combined silk fiber bundle for bioelectrical signal recording. PloS one 2012, 7, e33689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Dong, Z.; Hu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Qu, L.; Chen, N.; Dai, L. Textile electrodes woven by carbon nanotube–graphene hybrid fibers for flexible electrochemical capacitors. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 3428–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajani, A.; Gilani, H.; Islam, S.; Khandoker, N.; Mazid, A.M. Fabrication of CNT-reinforced 6061 aluminium alloy surface composites by friction stir processing. Jom 2021, 73, 3718–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Lee, J.; Hyeon, T.; Lee, M.; Kim, D.-H. Fabric-based integrated energy devices for wearable activity monitors. Advanced Materials (Deerfield Beach, Fla.) 2014, 26, 6329–6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Goh, W.-P.; Norsten, T.B. Aqueous-based formation of gold nanoparticles on surface-modified cotton textiles. Journal of Molecular and Engineering Materials 2013, 1, 1250001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.H.; Hinestroza, J.P. Metal nanoparticles on natural cellulose fibers: electrostatic assembly and in situ synthesis. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2009, 1, 797–803. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kwon, H.; Seo, J.; Shin, S.; Koo, J.H.; Pang, C.; Son, S.; Kim, J.H.; Jang, Y.H.; Kim, D.E. Conductive fiber-based ultrasensitive textile pressure sensor for wearable electronics. Advanced materials 2015, 27, 2433–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y. Conductive materials with elaborate micro/nanostructures for bioelectronics. Advanced Materials 2022, 34, 2110024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, B.; Alam, M.R.; Rahman, M.A.; Newaz, K.; Khan, M.A.; Rahman, M.Z. Advanced nanocomposites for sensing applications. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwa, Y.; Maheshwari, N.; Goldthorpe, I.A. Silver nanowire coated threads for electrically conductive textiles. Journal of Materials Chemistry C 2015, 3, 3908–3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhashmi Alamer, F.; Badawi, N.M. Fully Flexible, Highly Conductive Threads Based on single walled carbon nanotube (SWCNTs) and poly (3, 4 ethylenedioxy thiophene) poly (styrenesulfonate)(PEDOT: PSS). Advanced Engineering Materials 2021, 23, 2100448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Facchetti, A. Mechanically flexible conductors for stretchable and wearable e-skin and e-textile devices. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, 1901408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardeen, J. Electrical conductivity of metals. Journal of Applied Physics 1940, 11, 88–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Afroj, S.; Yin, J.; Novoselov, K.S.; Chen, J.; Karim, N. Advances in printed electronic textiles. Advanced Science 2024, 11, 2304140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cork, C. Conductive fibres for electronic textiles: an overview. Electronic Textiles 2015, 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Dev, B.; Rahman, M.A.; Tazrin, T.; Islam, M.S.; Datta, A.; Rahman, M.Z. Investigation of Mechanical Properties of Nonwoven Recycled Cotton/PET Fiber-Reinforced Polyester Hybrid Composites. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering 2024, 2400020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, K.; Goldizen, F.C.; Sly, P.D.; Brune, M.-N.; Neira, M.; van den Berg, M.; Norman, R.E. Health consequences of exposure to e-waste: a systematic review. The lancet global health 2013, 1, e350–e361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwakarma, S.; Kumar, V.; Arya, S.; Tembhare, M.; Dutta, D.; Kumar, S. E-waste in Information and Communication Technology Sector: Existing scenario, management schemes and initiatives. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2022, 27, 102797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghulam, S.T.; Abushammala, H. Challenges and opportunities in the management of electronic waste and its impact on human health and environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Shu, L.; Yang, Y.; Ren, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, W. Smart textile-integrated microelectronic systems for wearable applications. Advanced materials 2020, 32, 1901958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- contributors, W. Units of textile measurement. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Units_of_textile_measurement.

- Stavrakis, A.K.; Simić, M.; Stojanović, G.M. Electrical characterization of conductive threads for textile electronics. Electronics 2021, 10, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzowska, J.; Bromley, M. Soft computation through conductive textiles. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Foundation of Fashion Technology Institutes Conference, 2007; pp. 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Group, A. AMANN TechX Brochure. Available online: https://www.amann.com/fileadmin/user_upload/Download_Center/Brochures/AMANN_TechX_Brochure_EN.pdf.

- Coats. Coats Magellan. Available online: https://www.coats.com/en/products/threads/magellan/magellan/.

- Badawi, N.M.; Batoo, K.M.; Hussain, S.; Agrawal, N.; Bhuyan, M.; Bashir, S.; Subramaniam, R.; Kasi, R. Design and Characterization of electroconductive graphene-coated cotton fabric for wearable electronics. Coatings 2023, 13, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfameni, S.; Lawnick, T.; Rando, G.; Visco, A.; Textor, T.; Plutino, M.R. Super-hydrophobicity of polyester fabrics driven by functional sustainable fluorine-free silane-based coatings. Gels 2023, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, K.; Grabowska, K.; Stempień, Z.; Ciesielska-Wrobel, I.; Rutkowska, A.; Taranek, D. Woven fabrics containing hybrid yarns for shielding electromagnetic radiation. Fibres & Textiles in Eastern Europe 2016, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Ahmed, R.; Siddique, A.B.; Begum, H.A. Extraction and characterization of a newly developed cellulose enriched sustainable natural fiber from the epidermis of Mikania micrantha. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Jin, L.; Qi, J.; Liu, Z.; Xu, L.; Hayes, S.; Gill, S.; Li, Y. Performance evaluation of conductive tracks in fabricating e-textiles by lock-stitch embroidery. Journal of Industrial Textiles 2022, 51, 6864S–6883S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.U.A.; Saha, A.K.; Bristy, Z.T.; Tazrin, T.; Baqui, A.; Dev, B. Development of the smart jacket featured with medical, sports, and defense attributes using conductive thread and thermoelectric fabric. Engineering Proceedings 2023, 30, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Thread No | Thread Name | Twist Direction | No of Ply [filament] |

Coating Agent [Solution] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Non-Coated Polyester Twisted Copper Thread-I | Z | Polyester-2, Copper-4 | N/A |

| 2 | Non-Coated Cotton Twisted Copper Thread-I | Z | Cotton-3, Copper-4 | N/A |

| 3 | Carbon Coated Polyester Twisted Copper Thread | Z | Polyester-2, Copper-4 | Solution ‘A’ |

| 4 | Non-Coated Cotton Double Twisted Copper Thread | Z, S | Cotton-3, Copper-4 | N/A |

| 5 | Non-Coated Polyester Double Twisted Copper Thread | Z, S | Polyester-2, Copper-4 | N/A |

| 6 | Non-Coated Cotton Twisted Copper Thread-III | Z | Cotton-3, Copper-3 | N/A |

| 7 | Carbon Coated Cotton Twisted Copper Thread- II | Z | Cotton-3, Copper-4 | Solution ‘A’ |

| 8 | Non-Coated Cotton Twisted Copper Thread | Z | Cotton-3, Copper-2 | N/A |

| 9 | Non-Coated Polyester Twisted Copper Thread-III | Z | Polyester-2, Copper-3 | N/A |

| 10 | Non-Coated Cotton Twisted Copper Finest Thread | Z | Cotton-3, Copper-1 | N/A |

| 11 | Carbon Coated Cotton Twisted Copper Thread-V | Z | Cotton-3, Copper-3 | Solution ‘A’ |

| 12 | Carbon Coated Cotton Twisted Copper Thread–VI | Z | Cotton-3, Copper-3 | Solution ‘B’ |

| Thread No | R of DT [Ω cm-1] | Count [Ne] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0197 | 3 |

| 2 | 0.0197 | 3 |

| 3 | 0.0197 | 3 |

| 4 | 0.0197 | 3 |

| 5 | 0.0197 | 3 |

| 6 | 0.0197 | 3 |

| 8 | 0.0470 | 3.6 |

| 9 | 0.0230 | 3.6 |

| 10 | 0.0459 | 4.5 |

| 11 | 0.025 | 3.18 |

| 12 | 0.0273 | 3.37 |

| Signal Amplitude | Pick-to-Pick 5V |

|---|---|

| Frequency | 1kHz |

| Offset | 0 VDC |

| Phase | 0 degree |

| Load | 10 kΩ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).