Submitted:

14 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate how dietary yeast cell wall (YCW) supplementation in the starter feed affects ruminal fermentation parameters, microbial community composition, and metabolite profiles in early-weaned Simmental calves. Twenty-four newborn Simmental heifer calves (initial body weight: 37.53 ± 2.50 kg) were randomly assigned based on birth date sequence into the experimental group and the control group (12 calves per group). Calves in the experimental group (YCW) received a daily supplement of 5 g/head/day of yeast cell wall in the starter diet, whereas those in the control group (CON) received no supplementation. The experimental period lasted for 100 days, with weaning conducted at 70 days of age. On day 70, rumen fluid samples were randomly collected from six calves per group for analysis of rumen fermentation parameters, microbial community composition, and metabolomic profiles. (1) YCW supplementation significantly increased ruminal butyrate concentration and the relative abundance of the genus Ruminococcus (p < 0.05); (2) Metabolomic analysis identified 43 differential metabolites (20 upregulated and 23 downregulated), with nucleotide metabolism–related compounds such as guanylic acid and deoxycytidine monophosphate being prominently enriched (p < 0.05); (3) Spearman correlation analysis further revealed positive associations between Ruminococcus and both butyrate levels and selected upregulated metabolites, including guanylic acid (p < 0.05). Dietary yeast cell wall supplementation enhanced ruminal fermentation in early-weaned Simmental calves by increasing butyrate concentration and altering the ruminal microbiota and metabolome. Enrichment of Ruminococcus and nucleotide-associated metabolites, with positive correlations to butyrate, indicates a coordinated shift in the microbiota–metabolite axis. These findings support YCW as an effective nutritional strategy to promote rumen development and health during the early weaning period.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Subjects and Experimental Design

2.2. Rumen Fluid Sample Collection

2.2.1. Determination of Volatile Fatty Acids and Ammonia Nitrogen (NH₃-N)

2.2.2. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.2.3. Rumen Metabolomics Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results

3.1. Rumen Fermentation Characteristics

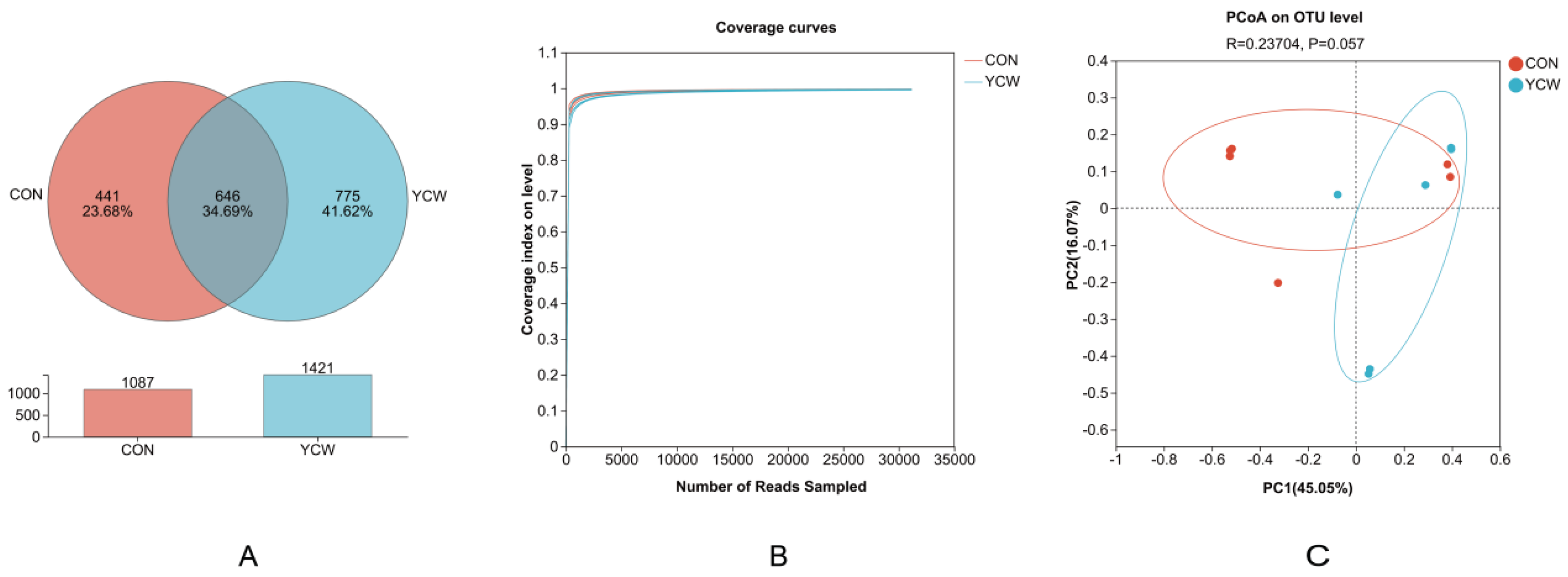

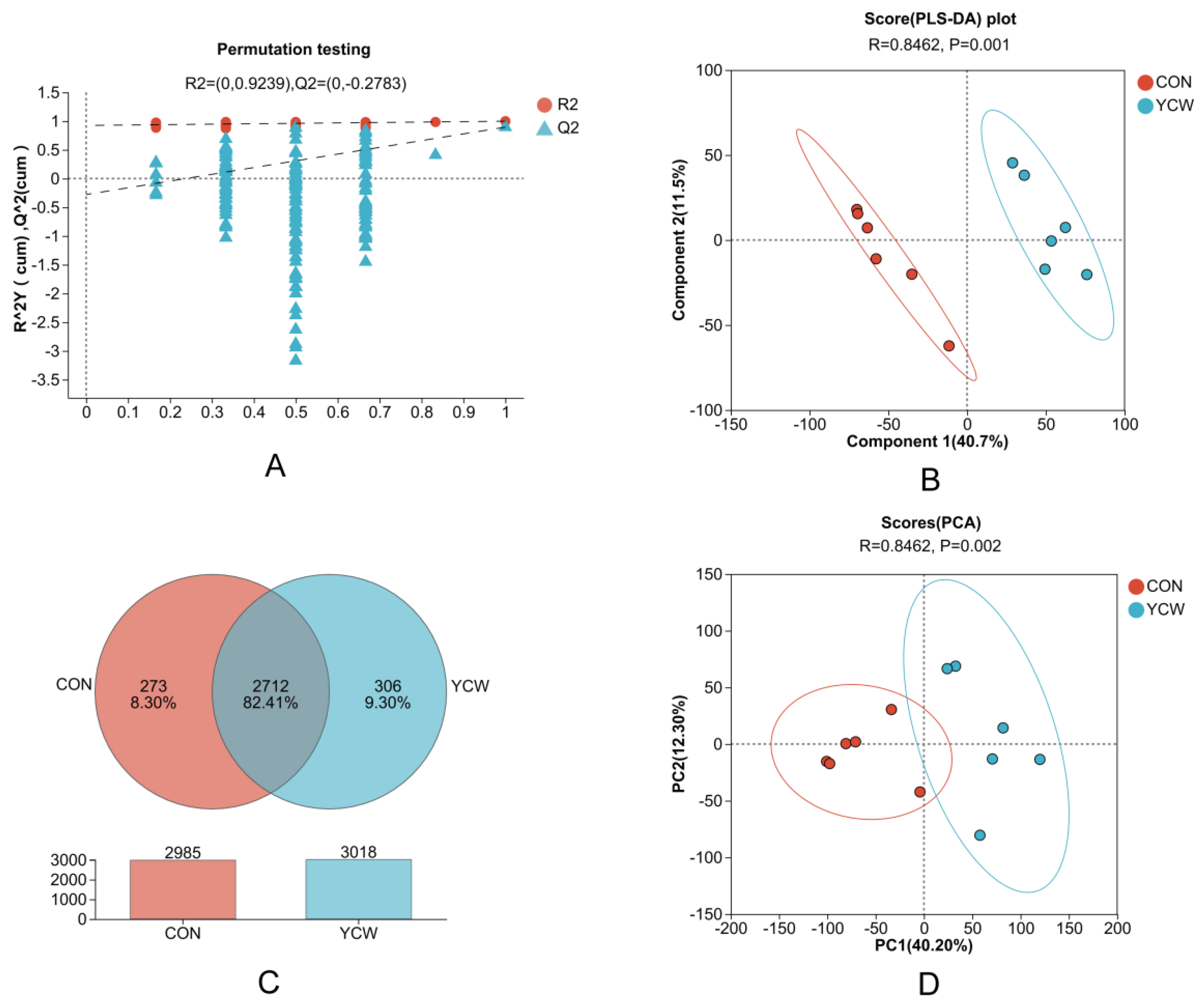

3.2. Rumen Microbial Community

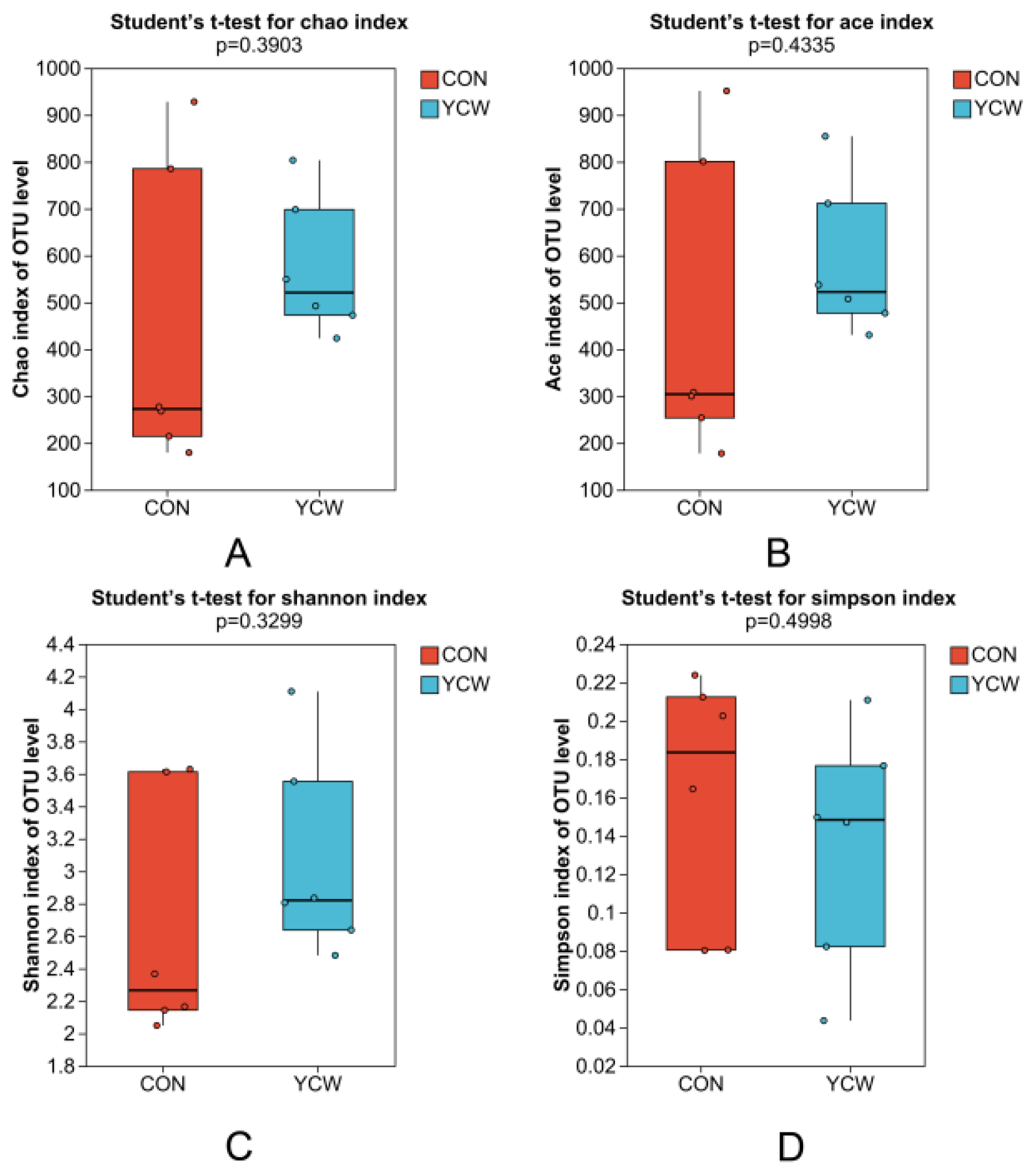

3.3. Rumen Microbial Species Composition

3.4. LEfSe Analysis for Multi-Level Differential Species Identification

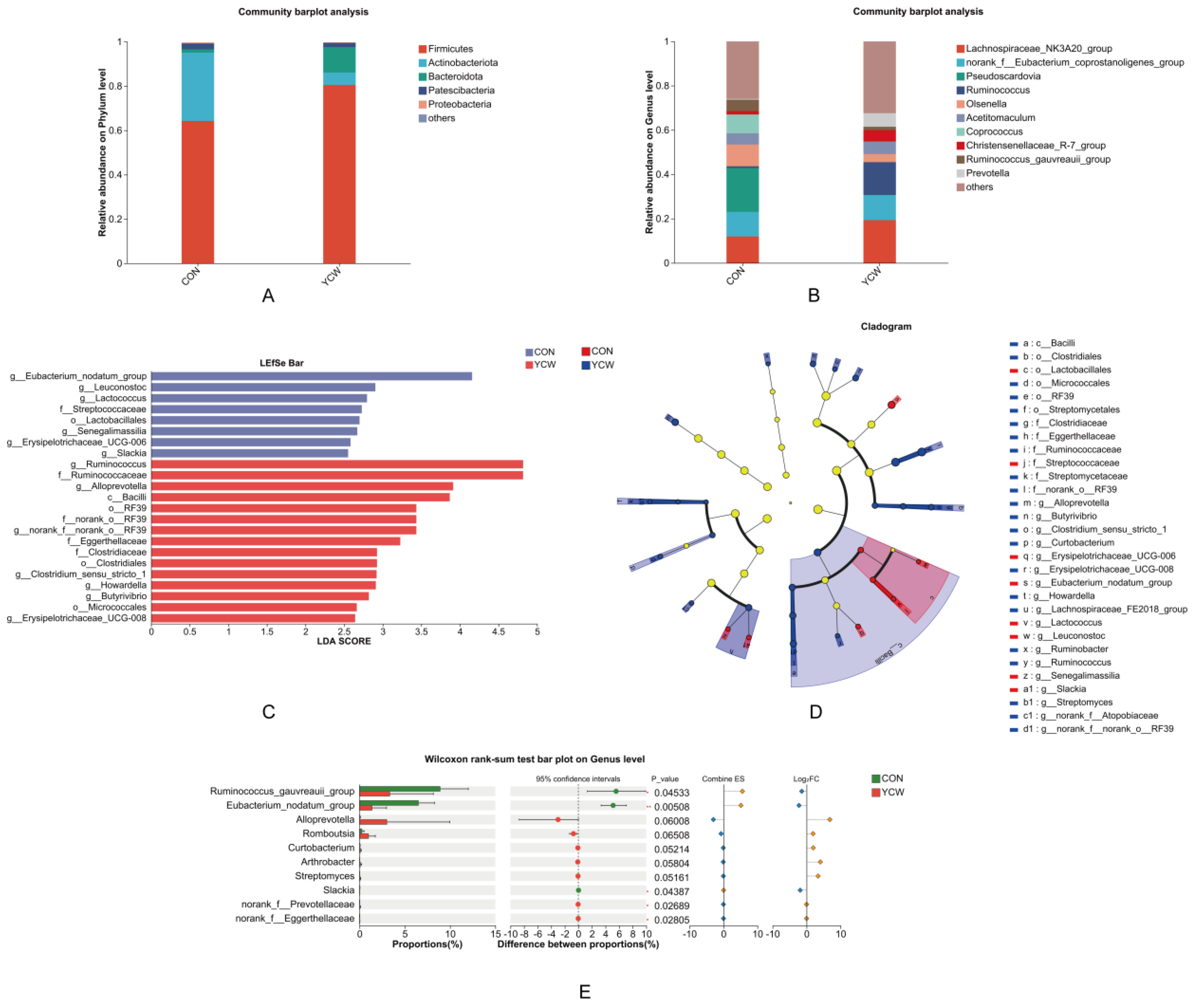

3.5. Correlation Analysis and Functional Prediction

3.6. Rumen Metabolites

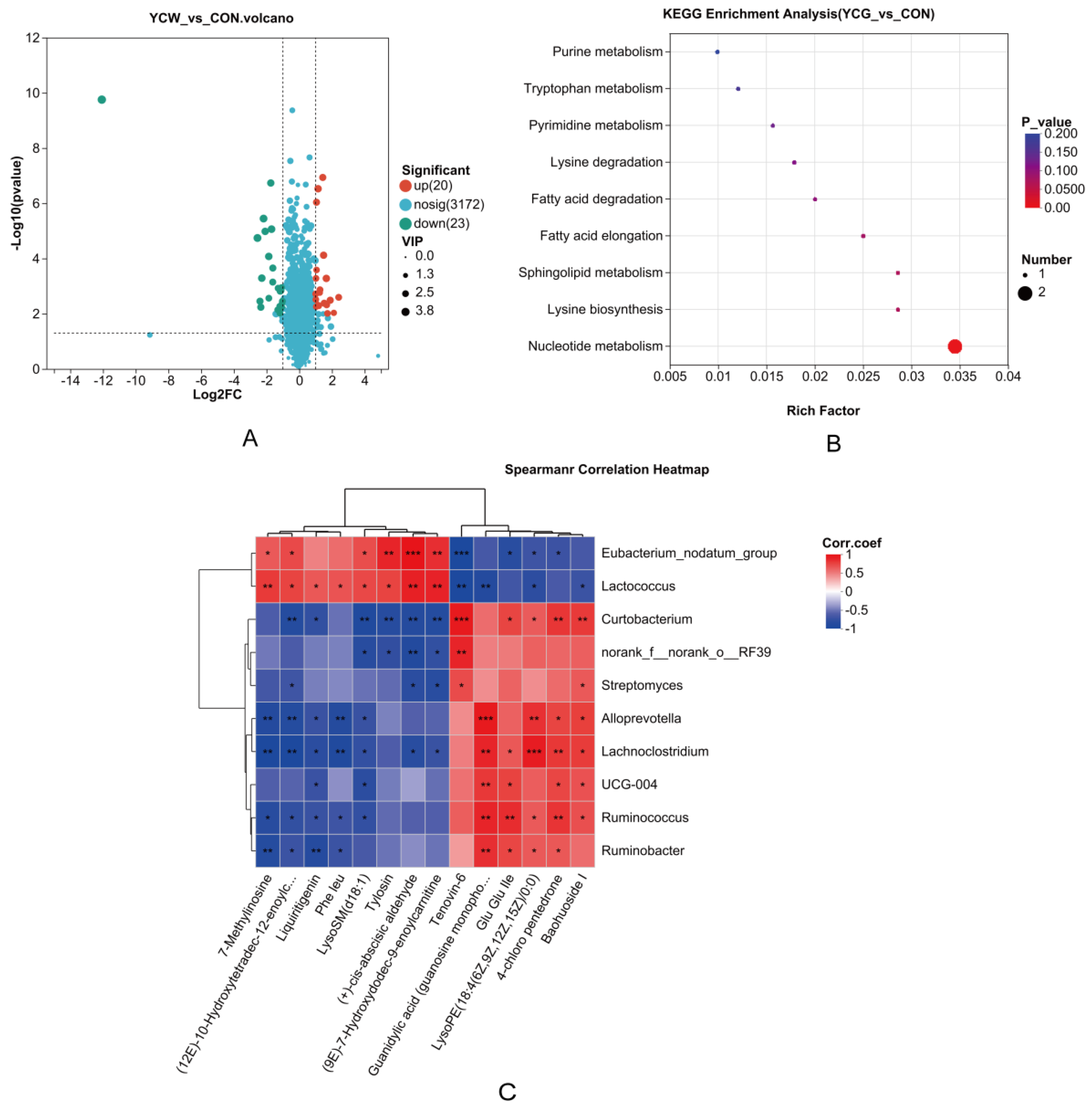

3.7. Analysis of Differential Metabolites and Associated Metabolic Pathways

3.8. Correlation Analysis Between Rumen Microorganisms and Differential Metabolites

| Items | Log2FC | P-value | VIP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upregulated metabolites | |||

| guanylic acid (guanosine monophosphate) | 1.65 | 0.001 | 2.84 |

| LysoPE (18:4(6Z,9Z,12Z,15Z)/0:0) | 1.15 | 0.000 | 2.90 |

| ‘7,8-dihydroxy-5,6-dimethoxy-2-phenylchromen-4-one’ | 1.49 | 0.000 | 2.73 |

| Baohuoside I | 1.89 | 0.003 | 2.69 |

| Kaempferol 3,7,4’-Trimethyl Ether | 1.44 | 0.000 | 2.58 |

| Haloperidol glucuronide | 1.05 | 0.000 | 2.52 |

| Deoxycytidine monophosphate | 1.52 | 0.004 | 2.54 |

| Convallatoxin | 1.67 | 0.005 | 2.40 |

| Albendazole-2-aminosulfone | 0.98 | 0.000 | 2.41 |

| Downregulated metabolites | |||

| 2-[(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z)-Icosa-5,8,11,14-tetraenoxy] propane-1,3-diol | -12.07 | 0.000 | 3.63 |

| Auraptenol | -2.56 | 0.000 | 3.18 |

| LysoSM(d18:1) | -2.18 | 0.000 | 3.17 |

| Tylosin | -1.70 | 0.000 | 3.09 |

| (+)-cis-abscisic aldehyde | -2.29 | 0.001 | 2.87 |

| Formyl-5-hydroxykynurenamine | -1.87 | 0.000 | 2.81 |

| (12E)-10-Hydroxytetradec-12-enoylcarnitine | -2.09 | 0.000 | 2.77 |

| (9E)-7-Hydroxydodec-9-enoylcarnitine | -1.74 | 0.000 | 2.74 |

| N6-(L-1,3-Dicarboxypropyl)-L-lysine | -2.35 | 0.006 | 2.64 |

| N-(furan-2-ylmethyl)-2-(6-oxopyridazin-1-yl) acetamide | -2.40 | 0.004 | 2.67 |

| 7-Methylinosine | -1.17 | 0.002 | 2.38 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jammer, BD; Lombard, WA; Jordaan, H. Investigating cow-calf productive performance under early and conventional weaning practices in south african beef cattle. Vet Anim Sci. 2025, 29, 100472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, YH; Nagata, R; Ohtani, N; Ichijo, T; Ikuta, K; Sato, S. Effects of Dietary Forage and Calf Starter Diet on Ruminal pH and Bacteria in Holstein Calves during Weaning Transition. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, EE; Baldwin, RL; Li, CJ; Li, RW; Chung, H. Gene expression in bovine rumen epithelium during weaning identifies molecular regulators of rumen development and growth. Funct Integr Genomics 2013, 13(1), 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokhrel, B; Jiang, H. Postnatal Growth and Development of the Rumen: Integrating Physiological and Molecular Insights. Biology (Basel) 2024, 13(4), 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C; Zhang, Q; Wang, G; et al. The functional development of the rumen is influenced by weaning and associated with ruminal microbiota in lambs. Anim Biotechnol 2022, 33(4), 612–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, A; Tu, R; Qi, M; et al. Mannan oligosaccharides selenium ameliorates intestinal mucosal barrier, and regulate intestinal microbiota to prevent Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli -induced diarrhea in weaned piglets. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2023, 264, 115448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfen, J; Carpinelli, N; Del Pino, FAB; et al. Effects of yeast culture supplementation on lactation performance and rumen fermentation profile and microbial abundance in mid-lactation Holstein dairy cows. J Dairy Sci 2021, 104(11), 11580–11592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, LK; Heinrichs, AJ. Feeding various forages and live yeast culture on weaned dairy calf intake, growth, nutrient digestibility, and ruminal fermentation. J Dairy Sci. 2020, 103(10), 8880–8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S; Fang, L; Kang, X; et al. Establishment and transcriptomic analyses of a cattle rumen epithelial primary cells (REPC) culture by bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing to elucidate interactions of butyrate and rumen development. Heliyon 2020, 6(6), e04112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigley, JD, 3rd; Kost, CJ; Wolfe, TA. Effects of spray-dried animal plasma in milk replacers or additives containing serum and oligosaccharides on growth and health of calves. J Dairy Sci 2002, 85(2), 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, M; Ohtsuka, H; Izumi, K. Effect of yeast cell wall supplementation on production performances and blood biochemical indices of dairy cows in different lactation periods. Vet World 2019, 12(6), 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J; Shah, A M; Shao, Y; et al. Effects of yeast cell wall on the growth performance, ruminal fermentation, and microbial community of weaned calves. Livest Sci 2020, 239, 104170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschenlauer, SC; McKain, N; Walker, ND; McEwan, NR; Newbold, CJ; Wallace, RJ. Ammonia production by ruminal microorganisms and enumeration, isolation, and characterization of bacteria capable of growth on peptides and amino acids from the sheep rumen. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002, 68(10), 4925–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, AB; Mao, S. Influence of yeast on rumen fermentation, growth performance and quality of products in ruminants: A review. Anim Nutr. 2021, 7(1), 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putri, EM; Zain, M; Warly, L; Hermon, H. Effects of rumen-degradable-to-undegradable protein ratio in ruminant diet on in vitro digestibility, rumen fermentation, and microbial protein synthesis. Vet World 2021, 14(3), 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J; Shi, L; Wang, Z; et al. Yeast β-glucan alleviates the subacute rumen acidosis-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and cell structure integrity injury in yak rumen epithelial cells via the TLR2/PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway. Int J Biol Macromol 2025, 309 Pt 2, 142929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohe, TT; Schramm, H; Parsons, CLM; et al. Form of calf diet and the rumen. Impact on growth and development J Dairy Sci 2019, 102(9), 8486–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G; Li, S; Ye, H; et al. Gut microbiome and frailty: insight from genetic correlation and mendelian randomization. Gut Microbes 2023, 15(2), 2282795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascano, G J; Heinrichs, A J. Rumen fermentation pattern of dairy heifers fed restricted amounts of low, medium, and high concentrate diets without and with yeastculture. Livest Sci 2009, 124(1-3), 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekkhahi, M; Tahmasbi, A M; Naserian, A A; et al. Effects of supplementation of active dried yeast and malate during sub-acute ruminal acidosis on rumen fermentation, microbial population, selected blood metabolites, and milk production in dairy cows. Anim Feed Sci Tech 2016, 213, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofyan, A; Uyeno, Y; Shinkai, T; et al. Metagenomic profiles of the rumen microbiota during the transition period in low-yield and high-yield dairy cows. Anim Sci J 2019, 90(10), 1362–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urga, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Wang, X; Wei, H; Zhao, G. Mechanisms and Applications of Gastrointestinal Microbiota-Metabolite Interactions in Ruminants: A Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13(12), 2880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, A; Purabdolah, H; Hajinia, F; et al. Emerging functionalities of yeast cell-wall components; the value-added food-grade pre-and post-biotics. Appl Food Res. 2025, 101072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C; Yang, J; Nie, X; Wu, Q; Wang, L; Jiang, Z. Influences of Dietary Vitamin E, Selenium-Enriched Yeast, and Soy Isoflavone Supplementation on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity, Carcass Traits, Meat Quality and Gut Microbiota in Finishing Pigs. Antioxidants (Basel) Published. 2022, 11(8), 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P; Yang, X; Hou, M; et al. Ruminal Yeast Strain with Probiotic Potential: Isolation and Characterization and Its Effect on Rumen Fermentation In Vitro. Microorganisms 2025, 13(6), 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J; Wu, D; Wang, Z; et al. Effects of yeast β-glucan on fermentation parameters, microbial community structure, and rumen epithelial cell function in high-concentrate-induced yak rumen acidosis in vitro. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025, 314, 144441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desvignes, P; Ruiz, P; Guillot, L; et al. Transcriptomic analysis of the interactions between Fibrobacter succinogenes S85, Selenomonas ruminantium PC18 and a live yeast strain used as a ruminant feed additive. BMC Genomics 2025, 26(1), 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnell, LJ; Reyes, AA; Wolfe, CA; et al. Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes Drive Differing Microbial Diversity and Community Composition Among Micro-Environments in the Bovine Rumen. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 897996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X; Xiao, J; Zhao, W; et al. Mechanistic insights into rumen function promotion through yeast culture (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) metabolites using in vitro and in vivo models. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1407024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunade, I; Schweickart, H; McCoun, M; Cannon, K; McManus, C. Integrating 16S rRNA Sequencing and LC⁻MS-Based Metabolomics to Evaluate the Effects of Live Yeast on Rumen Function in Beef Cattle. Animals (Basel) 2019, 9(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B; Fan, Y; Wang, H. Lactate uptake in the rumen and its contributions to subacute rumen acidosis of goats induced by high-grain diets. Front Vet Sci. 2022, 9, 964027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravelo, AD; Calvo Agustinho, B; Arce-Cordero, J; et al. Effects of partially replacing dietary corn with molasses, condensed whey permeate, or treated condensed whey permeate on ruminal microbial fermentation. J Dairy Sci 2022, 105(3), 2215–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirisan, V; Pattarajinda, V; Vichitphan, K; Leesing, R. Isolation, identification and growth determination of lactic acid-utilizing yeasts from the ruminal fluid of dairy cattle. Lett Appl Microbiol 2013, 57(2), 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y; Li, H; Wang, J; et al. Gender and age-related variations in rumen fermentation and microbiota of Qinchuan cattle. Anim Biosci. 2025, 38(5), 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H; Su, M; Wang, C; et al. Yeast culture repairs rumen epithelial injury by regulating microbial communities and metabolites in sheep. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1305772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X; Liu, L; Niu, P; et al. Promoting cytidine biosynthesis by modulating pyrimidine metabolism and carbon metabolic regulatory networks in Bacillus subtilis. Microb Cell Fact 2025, 24(1), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C; Wang, M; Liu, H; et al. Multi-omics reveals that the host-microbiome metabolism crosstalk of differential rumen bacterial enterotypes can regulate the milk protein synthesis of dairy cows. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2023, 14(1), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiolino, A; Centoducati, G; Casalino, E; et al. Use of a commercial feed supplement based on yeast products and microalgae with or without nucleotide addition in calves. J Dairy Sci. 2023, 106(6), 4397–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J; Zhang, C; Lu, K; et al. Effect of guanidinoacetic acid and betaine supplementation in soybean meal-based diets on growth performance, muscle energy metabolism and methionine utilization in the bullfrog Lithobates catesbeianus. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, Y; Seki, E; Kodama, Y; et al. Acid sphingomyelinase regulates glucose and lipid metabolism in hepatocytes through AKT activation and AMP-activated protein kinase suppression. FASEB J 2011, 25(4), 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, JJ; Kyoung, H; Cho, JH; et al. Dietary Yeast Cell Wall Improves Growth Performanceand Prevents of Diarrhea of Weaned Pigs by Enhancing Gut Health and Anti-Inflammatory Immune Responses. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11(8), 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Day | Lactation Arrangement | Starter Feed Offered (g) | Starter Feeding Schedule |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0-7 | Unrestricted suckling | 10~20 | --- |

| 8-14 | 80~100 | 1–2/d (for feeding stimulation) |

|

| 15-21 | 80~100 | 2 × 2-h sessions daily | |

| 22-28 | 80~100 | 3 × 2-h sessions daily | |

| 29-36 | 4 × 1-h sessions daily | 150~200 | Ad libitum access |

| 37-43 | 3 × 1-h sessions daily | 200~500 | |

| 44-50 | 3 × 0.5-h sessions daily | 500~800 | |

| 51-70 (weaning phase) | 1 × 0.5-h sessions daily | 1000~1400 |

| Ingredients | Content | Nutrient level | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | 40.54 | DM | 87.95 |

| Soybean meal | 32.00 | CP | 22.17 |

| Wheat bran | 5.80 | EE | 5.79 |

| Cottonseed meal | 5.30 | Ash | 5.91 |

| Puffed soybeans | 5.00 | NDF | 12.23 |

| Whey powder | 4.00 | ADF | 6.18 |

| Molasses | 4.00 | Ca | 0.91 |

| CaCO3 | 1.60 | P | 0.59 |

| Soybean oil | 0.80 | ||

| NaCl | 0.60 | ||

| CaHPO4 | 0.10 | ||

| MgO | 0.10 | ||

| Selenium yeast | 0.02 | ||

| 1Premix | 0.14 | ||

| Total | 100.00 |

| Items | Group | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CON | YCW | ||

| pH | 6.33 ± 0.17 | 6.40 ± 0.27 | 0.660 |

| Ammonia Nitrogen(mg/dL) | 11.53 ± 2.62 | 10.92 ± 2.28 | 0.737 |

| Acetic acid | 44.90 ± 6.74 | 45.52 ± 5.76 | 0.893 |

| Propionic acid | 17.33 ± 1.41 | 16.54 ± 3.97 | 0.722 |

| Butyric acid | 4.85 ± 0.76a | 6.79 ± 0.25b | 0.001 |

| Isobutyric acid | 1.99 ± 0.35 | 2.55 ± 0.52 | 0.133 |

| Valeric acid | 3.39 ± 1.11 | 3.51 ± 1.02 | 0.877 |

| Isovaleric acid | 4.04 ± 0.60 | 3.83 ± 0.78 | 0.683 |

| Total Acid | 76.53 ± 9.88 | 78.77 ± 3.09 | 0.681 |

| Items | Group | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CON | YCW | ||

| Phylum level | |||

| p__Firmicutes | 64.24 ± 15.59 | 80.47 ± 15.29 | 0.092 |

| p__Actinobacteriota | 1.53 ± 0.71 | 11.46 ± 1.36 | 0.229 |

| p__Bacteroidota | 30.81 ± 2.66 | 5.63 ± 3.83 | 0.128 |

| p__Patescibacteria | 2.66 ± 0.02 | 1.95 ± 0.11 | 0.748 |

| p__Proteobacteria | 0.46 ± 0.16 | 0.25 ± 0.19 | 0.261 |

| Genus level | |||

| g__Lachnospiraceae_NK3A20_group | 11.94 ± 1.81 | 19.32 ± 1.03 | 0.378 |

| g__norank_f__Eubacterium_coprostanoligenes_group | 11.12 ± 5.05 | 11.30 ± 7.67 | 0.810 |

| g__Pseudoscardovia | 19.82 ± 1.76 | 0.058 ± 0.02 | 0.494 |

| g__Ruminococcus | 0.79 ± 0.22b | 14.83 ± 1.86a | 0.030 |

| g__Prevotella | 0.36 ± 0.64 | 6.12 ± 1.73 | 0.128 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).