Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

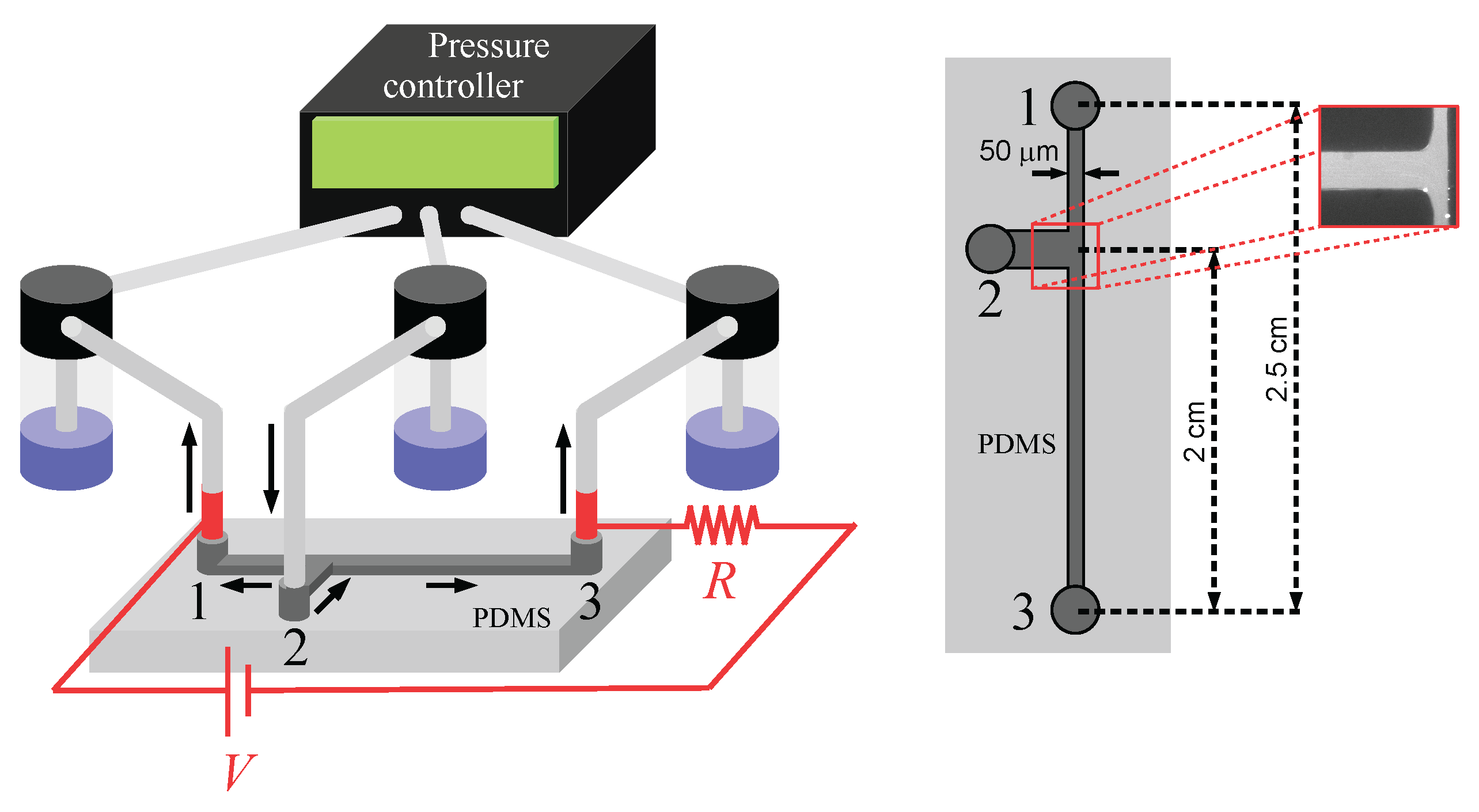

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

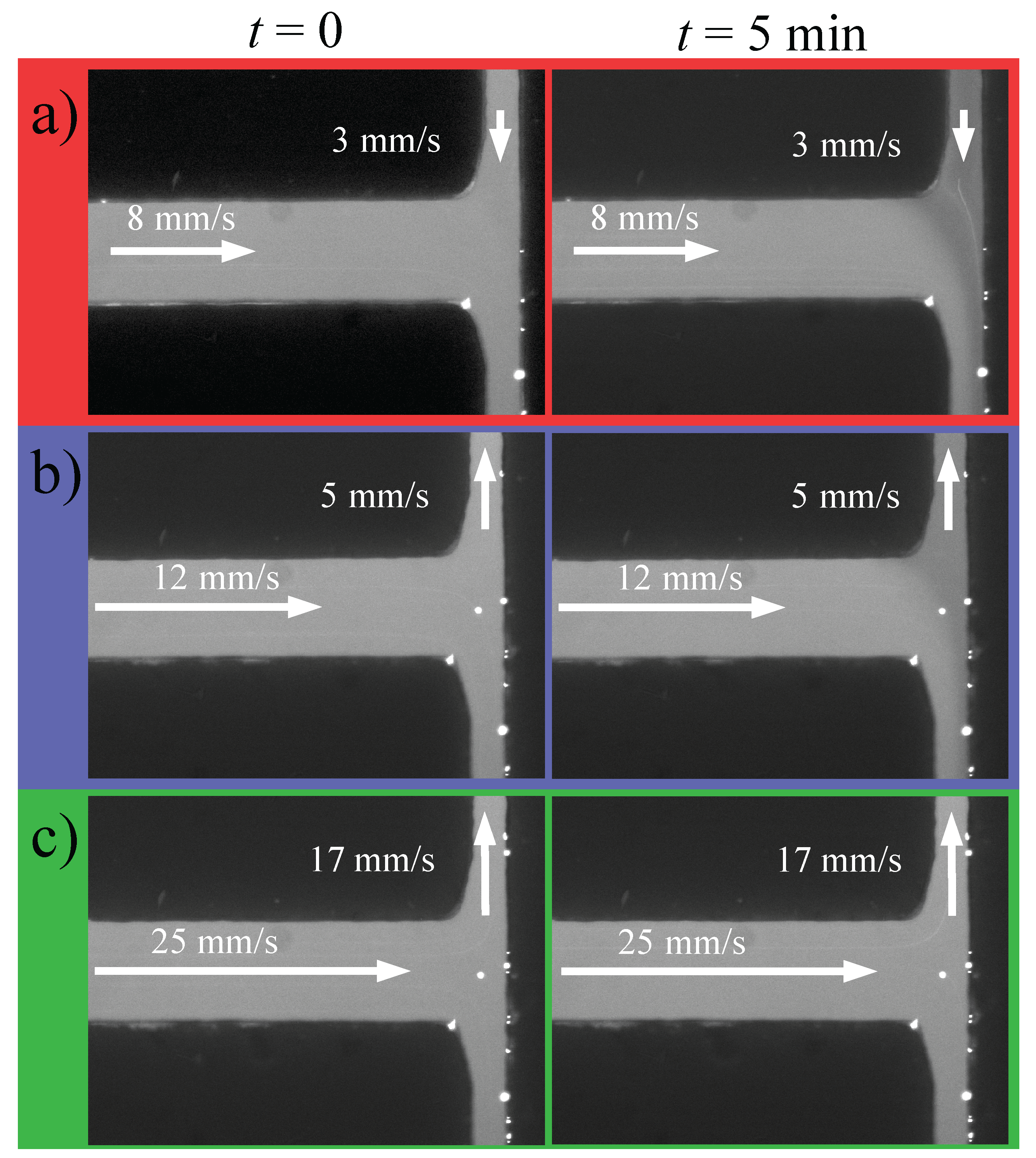

3.1. Experiments with Fluorescein

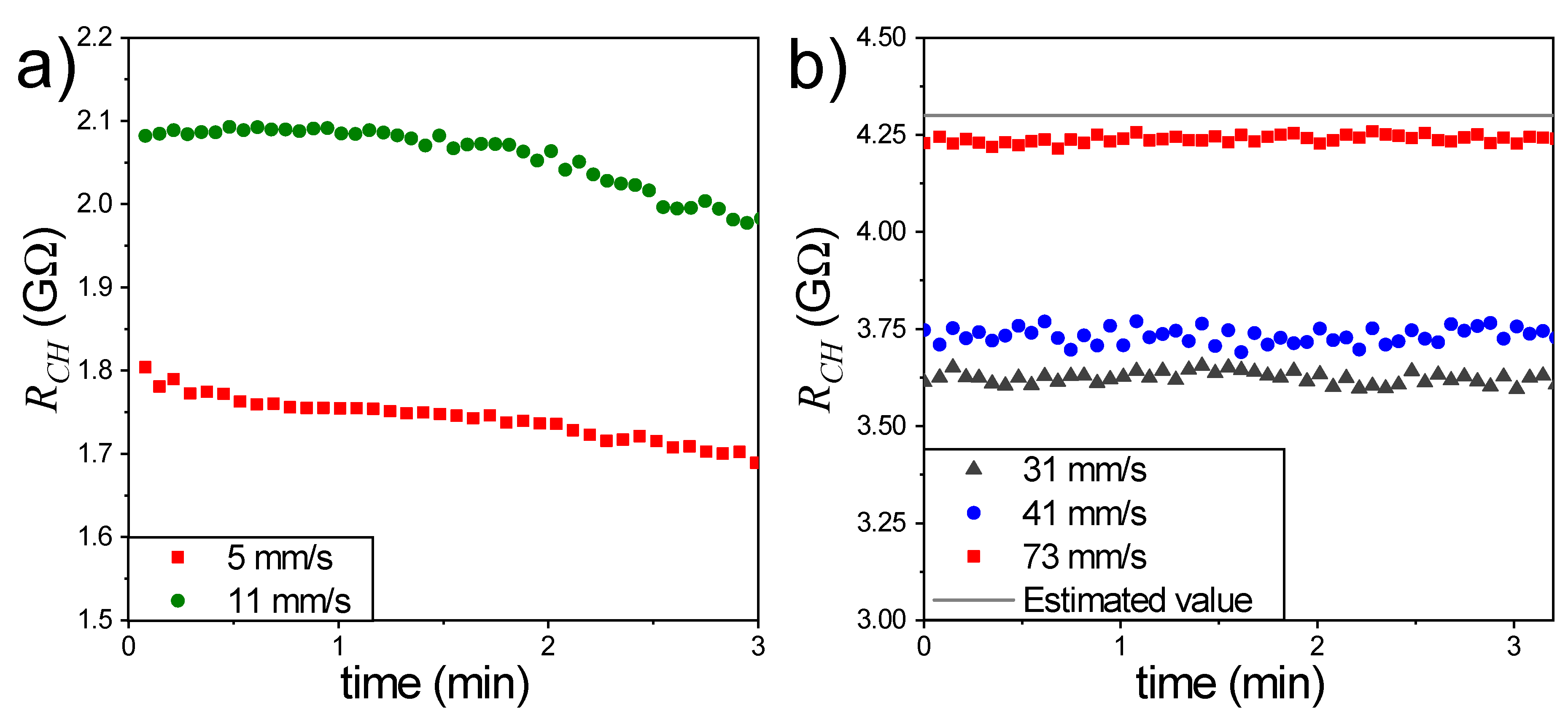

3.2. Electrical Measurements

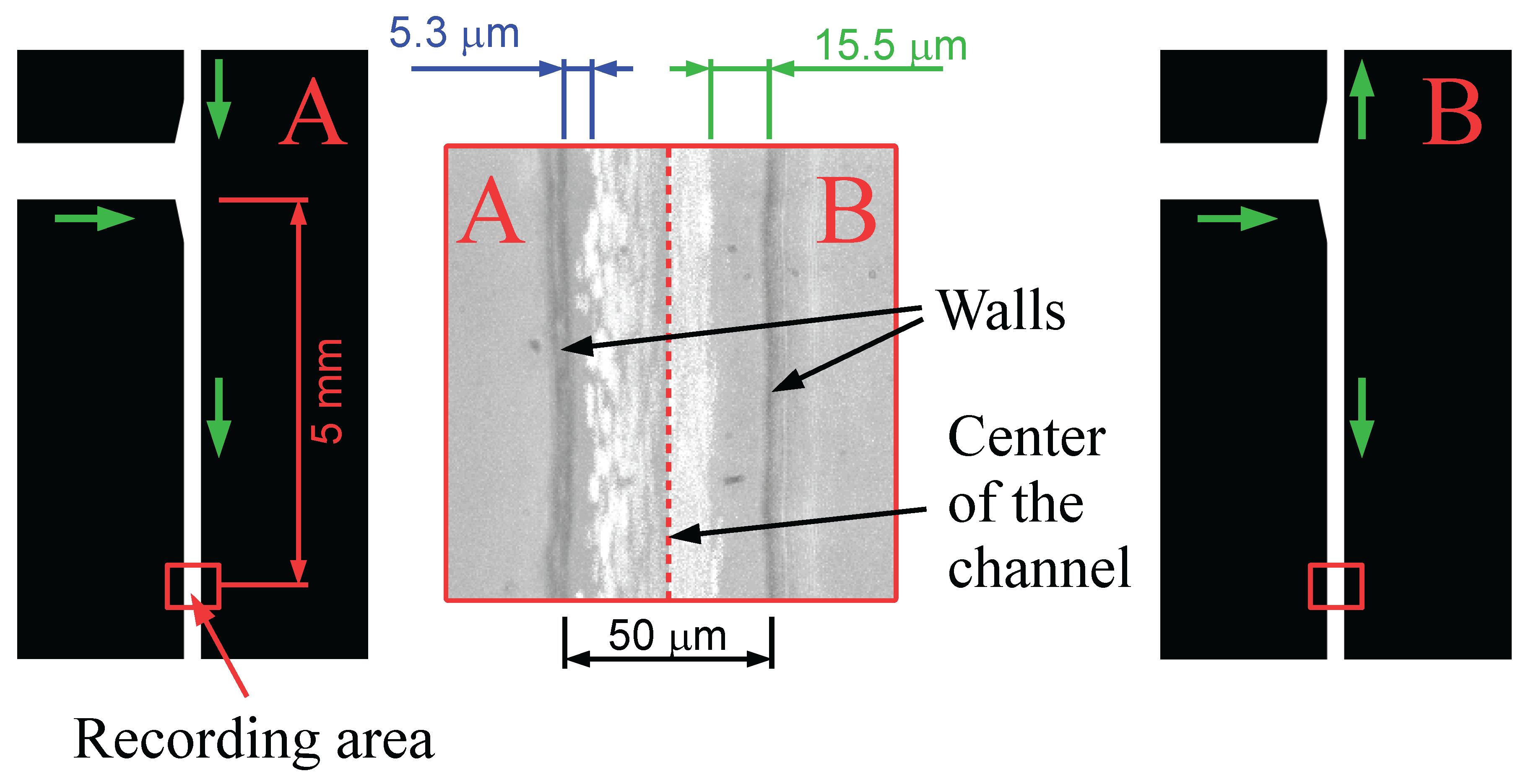

3.3. Electrophoresis Experiments

4. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Hunter, R. Introduction to Modern Colloid Science; Oxford University Press, 1993.

- von Smoluchowski, M. Contribution à la théorie de l’endosmose électrique et de quelques phénomènes corrélatifs. Bull. Akad. Sci. Cracovie. 1903, 8, 182–200.

- O’Brien, R.W.; White, L.R. Electrophoretic mobility of a spherical colloidal particle. Journal of the Chemical Society, Faraday Transactions 2: Molecular and Chemical Physics 1978, 74, 1607–1626. DOI . [CrossRef]

- Southern, E.M.; et al. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J mol biol 1975, 98, 503–517. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mateo, R.; García-Sánchez, P.; Calero, V.; Ramos, A.; Morgan, H. A simple and accurate method of measuring the zeta-potential of microfluidic channels. Electrophoresis 2022, 43, 1259–1262. [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Espinosa, M.A.; Lapizco-Encinas, B.H. Refinement of current monitoring methodology for electroosmotic flow assessment under low ionic strength conditions. Biomicrofluidics 2016, 10, 033104. [CrossRef]

- Saucedo-Espinosa, M.A.; Rauch, M.M.; LaLonde, A.; Lapizco-Encinas, B.H. Polarization behavior of polystyrene particles under direct current and low-frequency (<1 kHz) electric fields in dielectrophoretic systems. Electrophoresis 2016, 37, 635–644. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mateo, R.; Calero, V.; Morgan, H.; García-Sánchez, P.; Ramos, A. Wall Repulsion of Charged Colloidal Particles during Electrophoresis in Microfluidic Channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 128, 074501. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mateo, R.; Morgan, H.; Ramos, A.; García-Sánchez, P. Wall Repulsion during Electrophoresis: Testing the theory of Concentration-Polarization Electroosmosis. Physics of Fluids 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gallo-Villanueva, R.C.; Rodríguez-López, C.E.; Díaz-de-la Garza, R.I.; Reyes-Betanzo, C.; Lapizco-Encinas, B.H. DNA manipulation by means of insulator-based dielectrophoresis employing direct current electric fields. Electrophoresis 2009, 30, 4195–4205. [CrossRef]

- Pysher, M.D.; Hayes, M.A. Electrophoretic and dielectrophoretic field gradient technique for separating bioparticles. Analytical chemistry 2007, 79, 4552–4557. [CrossRef]

- Corstjens, H.; Billiet, H.A.; Frank, J.; Luyben, K.C. Variation of the pH of the background electrolyte due to electrode reactions in capillary electrophoresis: theoretical approach and in situ measurement. Electrophoresis 1996, 17, 137–143. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, C.R.; Finlayson, B.; Yager, P. Formation of natural pH gradients in a microfluidic device under flow conditions: model and experimental validation. Analytical Chemistry 2001, 73, 658–666. [CrossRef]

- Calero, V.; García-Sánchez, P.; Ramos, A.; Morgan, H. Combining DC and AC electric fields with deterministic lateral displacement for micro-and nano-particle separation. Biomicrofluidics 2019, 13, 054110. [CrossRef]

- Persat, A.; Suss, M.E.; Santiago, J.G. Basic principles of electrolyte chemistry for microfluidic electrokinetics. Part II: Coupling between ion mobility, electrolysis, and acid–base equilibria. Lab on a Chip 2009, 9, 2454–2469. [CrossRef]

- Macka, M.; Andersson, P.; Haddad, P.R. Changes in electrolyte pH due to electrolysis during capillary zone electrophoresis. Analytical Chemistry 1998, 70, 743–749. [CrossRef]

- Novotnỳ, T.; Gaš, B. Electrolysis phenomena in electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 2020, 41, 536–544. [CrossRef]

- Macounová, K.; Cabrera, C.R.; Holl, M.R.; Yager, P. Generation of natural pH gradients in microfluidic channels for use in isoelectric focusing. Analytical chemistry 2000, 72, 3745–3751. [CrossRef]

- Kosmulski, M. Surface charging and points of zero charge; CRC press, 2009.

- Chen, D.; Arancibia-Miranda, N.; Escudey, M.; Fu, J.; Lu, Q.; Amon, C.H.; Galatro, D.; Guzmán, A.M. Nonlinear dependence (on ionic strength, pH) of surface charge density and zeta potential in microchannel electrokinetic flow. Heliyon 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

- Abdorahimzadeh, S.; Bölükkaya, Z.; Vainio, S.J.; Liimatainen, H.; Elbuken, C. Anomalous electrohydrodynamic cross-stream particle migration. Physics of Fluids 2024, 36. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Pan, C.; Zhang, J.; Yan, S.; Zhao, Q.; Alici, G.; Li, W. Tunable Particle Focusing in a Straight Channel with Symmetric Semicircle Obstacle Arrays Using Electrophoresis-Modified Inertial Effects. Micromachines 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Lochab, V.; Yee, A.; Yoda, M.; Conlisk, A.; Prakash, S. Dynamics of colloidal particles in microchannels under combined pressure and electric potential gradients. Microfluidics and Nanofluidics 2019, 23, 134. [CrossRef]

- Trau, M.; Saville, D.A.; Aksay, I.A. Assembly of Colloidal Crystals at Electrode Interfaces. Langmuir 1997, 13, 6375–6381. [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, M.J.; Gamaj, M.I. Estimation of the Diffusion Coefficient and Hydrodynamic Radius (Stokes Radius) for Inorganic Ions in Solution Depending on Molar Conductivity as Electro-Analytical Technique-A Review. Journal of Chemical Reviews 2020, 2, 182–188. [CrossRef]

- Arcenegui-Troya, J.; Fernández-Mateo, R.; Ramos, A.; García-Sánchez, P. Wall repulsion of charged Brownian particles subjected to alternating current electric fields in microfluidic channels. Physics of Fluids 2025, 37. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Mateo, R.; García-Sánchez, P.; Calero, V.; Morgan, H.; Ramos, A. Stationary electro-osmotic flow driven by AC fields around charged dielectric spheres. Journal of Fluid Mechanics 2021, 924, R2. [CrossRef]

- Calero, V.; Fernández-Mateo, R.; Morgan, H.; García-Sánchez, P.; Ramos, A. Stationary Electro-osmotic Flow Driven by ac Fields around Insulators. Physical Review Applied 2021, 15, 014047. [CrossRef]

- Khair, A.S.; Kabarowski, J.K. Migration of an electrophoretic particle in a weakly inertial or viscoelastic shear flow. Physical Review Fluids 2020, 5, 033702. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).