Introduction

Most life forms rely on oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions for energy generation, with the transfer of electrons between donor and acceptor chemical species at the core of this process. Microbes source the electrons needed for their metabolic processes from the environment via direct or indirect means. While most microbes utilize soluble electron donors or acceptors, in environments where they are limited, some microbes have evolved the ability to transfer electrons to or from external solids, through a process known as extracellular electron transfer (EET). This adaptation enables microbes to access critical energy resources in otherwise inhospitable redox-limited environments such as deep marine sediments, anoxic soils, and mineral-rich subsurfaces[

1,

2]. EET is bidirectional and can be classified based on the direction of electron flow. In reductive extracellular electron transfer (rEET), electrons are transported out of the cell to reduce external solid-phase electron acceptors. This form of EET is analogous to respiration, where the solidphase material serves as the terminal electron acceptor.

Geobacter sulfurreducens[

3] are examples of microbes capable of reducing Fe(III) oxides. Conversely, extracellular electron uptake (EEU) involves the flow of electrons into the cell from external solid-phase electron donors. Photoautotrophic bacteria, such as

Rhodopseudomonas palustris[

4], can couple EEU with CO₂ fixation allowing them to synthesize biomass from inorganic carbon.

EET has far-reaching significance in both ecological and biotechnological contexts. In natural systems, it plays a crucial role in microbial energy flow and biogeochemical cycling, particularly in anoxic and nutrient-limited environments[

2]. Beyond its ecological importance, EET has substantial potential for applications in biotechnology and sustainable development. Microbes capable of EET are instrumental in bioremediation, where they facilitate the removal or immobilization of environmental pollutants. For example, species like Geobacter can reduce and immobilize toxic metals such as uranium[

5,

6] by transferring electrons to insoluble electron acceptors. Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) harness rEET to generate electricity from organic substrates. In these systems, microbes oxidize organic matter and transfer electrons to an anode, generating electrical current as a renewable energy source[

7,

8]. Microbial electrosynthesis (MES) represents another significant application of EET, specifically EEU. In MES systems, microbes use electrons from a cathode to reduce carbon dioxide into value-added bioproducts, including biofuels, bioplastics, and specialty chemicals[

9,

10,

11]. Photoautotrophic microbes like

Rhodopseudomonas palustris can couple EEU with light-driven carbon fixation, creating carbon neutral pathways to produce sustainable bioproducts[

12].

Miniaturized electrochemical platforms have been developed to address the limitations of traditional reactors in the study of EET, which typically lack compatibility with multiplexing or high-resolution imaging. Examples include paper-based microbial fuel cell arrays[

13,

14,

15], flexible textile-based systems[

16,

17,

18], and PDMS-based microfluidic devices[

19,

20,

21,

22]. CNT-modified electrodes have improved biofilm-electrode interactions in confined systems[

23,

24], while integrated LED-based circuits have simplified electrogenicity screening in resource-limited settings[

23].

Here, we report on a scalable glass-based microfluidic bioelectrochemical cell (µ-BEC) platform designed for multiplexed EEU measurements. The µ-BEC integrates eight three-electrode cells in a 2×4 layout with transparent working electrodes and microfluidic control, allowing simultaneous imaging and electrochemical analysis. We used Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 as a model organism to characterize EEU activity in response to light and assess the impact of planktonic versus biofilm-associated cells. Experiments in the µ-BEC confirmed light-dependent EEU in TIE-1 and enabled isolation of biofilm-specific electron uptake by removing planktonic cells through controlled microfluidic flow. These findings demonstrate the platform’s suitability for investigating phototrophic EEU and validate its potential for use in high-throughput and mechanistic studies.

Materials and Methods

Electrode Array Lithography, Deposition, Lift-Off and Annealing

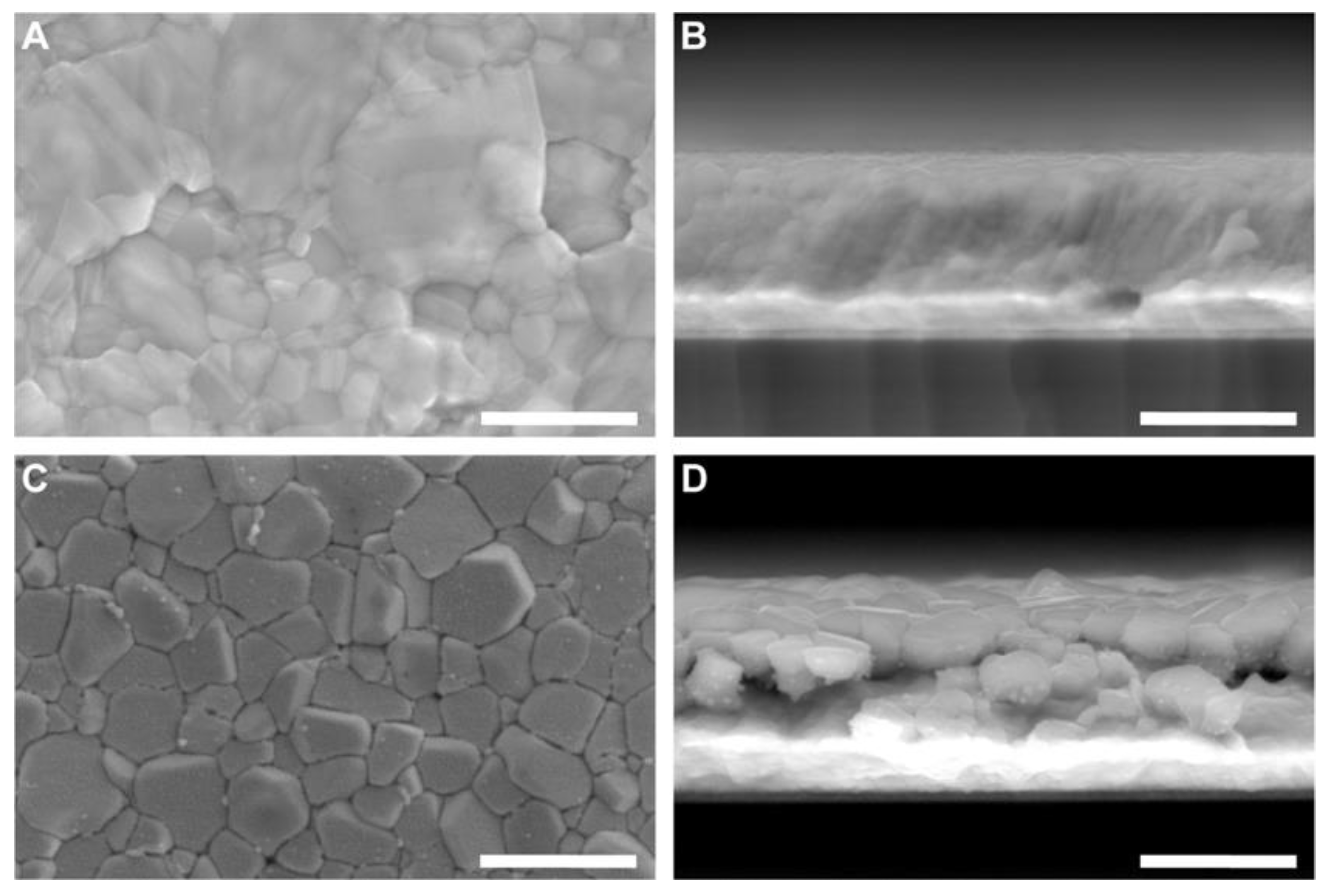

Electrode-support layers were fabricated on 100-mm diameter, 500-µm thick borosilicate glass wafers (University Wafer, Boston, MA, USA). Prior to each lithography step, wafers were cleaned sequentially with acetone, methanol, and isopropanol, dried under nitrogen flow, and placed on a 120°C hot plate for 15 minutes to eliminate residual moisture. A layer of KL8020 HMDS Spin-On Primer (KemLab™, Livermore, CA, USA) was spin-coated (Apogee® Spin Coater, Cost Effective Equipment LLC, Rolla, MO, USA) and soft-baked for 3 minutes at 115°C to promote photoresist adhesion. Subsequently, LOR 10B (Kayaku Advanced Materials Inc., Westborough, MA, USA) and Microposit™ S1805™ (Kayaku Advanced Materials Inc., Westborough, MA, USA) were sequentially spin-coated to thicknesses of 1.5 µm and 0.6 µm and soft-baked for 10 minutes at 195°C and 1 minute at 115°C respectively. Electrode patterns were exposed by direct laser writing (DWL 66+, Heidelberg Instruments Mikrotechnik GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) and developed using Microposit™ MFR-319 developer (Kayaku Advanced Materials Inc., Westborough, MA, USA). Residual photoresist was removed from the electrode areas by a 10-second exposure to a 100-Watt ozone plasma (PE-50 Plasma Asher, Plasma Etch Inc., Carson City, NV, USA) prior to thin-film deposition.

Counter electrodes and alignment marks were patterned and deposited by thermally evaporating a 20-nm thick chromium adhesion layer followed by a 250-nm thick gold layer (AUTO 306 Vacuum Coater, Edwards Vacuum, West Sussex, UK). Working electrodes were patterned and deposited by magnetron sputtering a 250-nm thick indium tin oxide (ITO) film (PVD 75, Kurt J. Lesker, Jefferson Hills, PA, USA). Pseudoreference electrodes were deposited through the sequential magnetron sputtering (PVD 75, Kurt J. Lesker, Jefferson Hills, PA, USA) of a 30-nm thick titanium adhesion layer and a 1000-nm thick silver layer. After each electrode deposition, lift-off was performed by immersion in a 65°C Remover PG bath (Kayaku Advanced Materials Inc., Westborough, MA, USA) for 1 hour, followed by transfer to a fresh room-temperature Remover PG bath for a minimum of 12 hours. Wafers were vacuum annealed at pressures below 1 × 10⁻⁶ Torr and 320°C for 30 minutes and cooled to room temperature under argon atmosphere (20 mTorr, 220 sccm) to enhance electrode adhesion and reduce working electrode sheet resistance.

Chlorination of the Pseudoreference Electrodes

The pseudoreference electrodes were further modified to contain a silver chloride (AgCl) layer through solution-based chlorination method. To protect the working and counter electrodes during chlorination, a layer of AZ P4620 photoresist (MicroChemicals GmbH, Ulm, Germany) was spin-coated and patterned to expose only the pseudoreference electrode surfaces. Exposed pseudoreference electrodes were cleaned in 10% hydrochloric acid (HCl), followed by chlorination in a 50 mM ferric chloride (FeCl₃) aqueous solution for 50 seconds, a stabilization step in a 3.5 M potassium chloride (KCl) aqueous solution for 5 seconds, and rinsing in deionized water. The protective AZ P4620 photoresist was subsequently removed by sequential washing in acetone, methanol, and isopropanol, and dried under nitrogen flow.

Application of a Patterned Proton Exchange Thin-Film Membrane on the Reference Electrode Surface

Pseudoreference electrodes were coated with a protective Nafion™ layer using a sacrificial polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic channel designed to selectively expose only the pseudoreference electrode surface while shielding the working and counter electrodes. PDMS channels were fabricated using a standard soft lithography process. SU-8 2100 photoresist (Kayaku Advanced Materials Inc., Westborough, MA, USA) was spin-coated to a 100-µm thickness and patterned to form a replica mold according to vendor-recommended parameters. The mold was silanized under vacuum for 12 hours using 1H,1H,2H,2H-Perfluorooctyltriethoxysilane (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to facilitate PDMS release. A 10:1 (base:curing agent) mixture of PDMS (SYLGARD™ 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit, Dow, Midland, MI, USA) was cast over the SU-8 mold and cured at room temperature for 48 hours on a level surface. Cured PDMS layers were cut to the desired dimensions, and 1-mm diameter inlet and outlet holes were created using a biopsy punch. PDMS channels were aligned to the electrode layer and brought into conformal contact. A 0.5% (w/w) Nafion™ solution diluted in 200 proof ethanol (Nafion™ 117 solution, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was introduced into the microfluidic channel inlet using a micropipette. After filling, the device was placed under vacuum inside a desiccator for 15 minutes to allow solvent evaporation, after which the PDMS channel was removed.

Microfluidic Channel Fabrication

Glass channels were fabricated from 100 mm × 100 mm, 1.5-mm thick soda-lime glass/chromium mask blanks (Telic Co., Santa Clarita, CA, USA). Mask blanks were precoated with a 5300-Å thick AZ1500 positive photoresist (Telic Co., Santa Clarita, CA, USA), and channel patterns were written using direct laser writing (DWL 66+, Heidelberg Instruments Mikrotechnik GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany). The exposed photoresist was developed for 120 seconds in an AZ® 400K developer bath (MicroChemicals GmbH, Ulm, Germany). Exposed chromium layers were etched using chrome etchant, and channels were isotropically etched to a depth of 100 µm using a solution of 49% (w/w) hydrofluoric acid (HF), 69% (w/w) nitric acid (HNO₃), and deionized water in a volumetric ratio of 2:1:6. Residual photoresist was removed by exposure to a 100-Watt oxygen plasma for 10 minutes (PE-50 Asher, Plasma Etch Inc., Carson City, NV, USA), followed by the removal of remaining chromium using chrome etchant.

Device Bonding and Packaging

Single electrode array devices and microfluidic channels were diced to final dimensions using a dicing saw (DAD 323, Disco Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Inlet and outlet holes with a 1-mm diameter were drilled into the channel layers using diamond-coated glass drill bits. Electrode arrays and channel substrates were cleaned by sonication in an acetone bath for 3 minutes, followed by sequential rinsing with methanol, isopropanol, and deionized water. Residual moisture was removed by drying under nitrogen flow and placing the substrates on a 120°C hot plate for 15 minutes. Device layers were bonded using a stamp and stick method with a UV-curable adhesive (NOA 61, Norland Products, East Windsor, NJ, USA). Adhesive was spin-coated onto a 75-mm diameter, 500-µm thick silicon transfer wafer (University Wafer, Boston, MA, USA) at a spreading speed of 500 RPM for 10 seconds and a spin speed of 6000 RPM for 30 seconds (CEE 200X Spin Coater, Brewer Science, Rolla, MO, USA). A mask aligner (MJB3 UV 400, Karl Suss, Germany) was used to stamp the adhesive onto the channel layer, align the device layers, bring them into contact, and expose the adhesive to a UV dosage of 3 J cm⁻². The bonded devices were cured on a 60°C hot plate for 45 minutes followed by curing at room temperature for 72 hours.

Microfluidic Channel and Electrode Interfacing

Microfluidic adapters (Stand Alone Olive Fluidic 630, Microfluidic ChipShop) were glued on top of the inlet and outlet holes using an adhesive ring (Adhesive Ring Fluidic 699, Microfluidic ChipShop) and sealed with epoxy resin, followed by curing at room temperature for at least 24 hours. The assembled devices are then mounted in a custom-designed microscopy-compatible metal-plastic holder that offers individually accessible connections to each electrode lead on the microfluidic device electrode layer via pogo-pins (825 spring-loaded pogo pin header strip, Mill-Maxx).

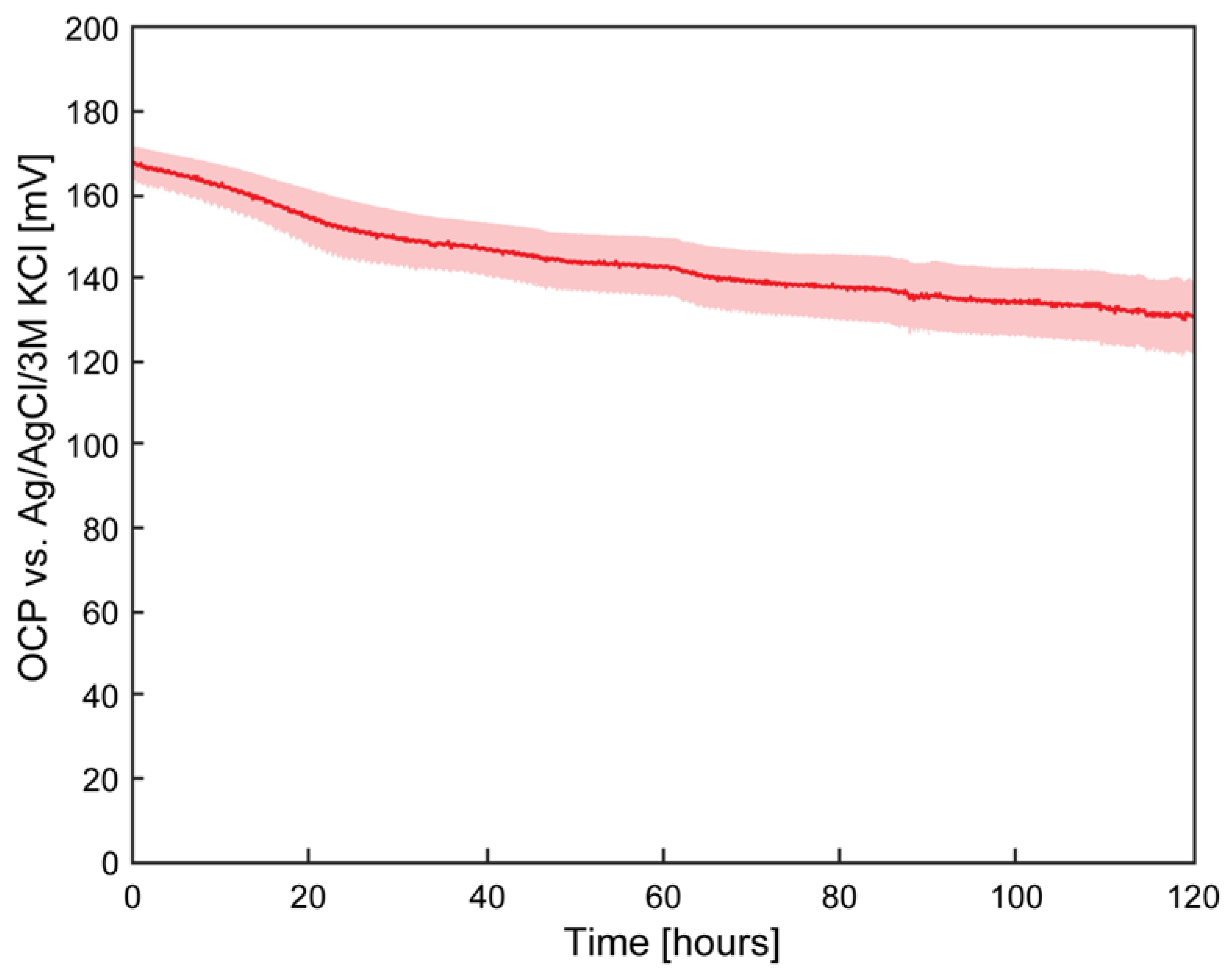

Open Circuit Potential Measurements of the Pseudoreference Electrodes

Single pseudoreference electrodes were fabricated following the same procedures and materials as the 2 × 4 device arrays and diced to final dimensions of 20 mm × 20 mm. Titanium wires (Ultra-Corrosion-Resistant Grade 2 Titanium Wire, 0.025-inch diameter, McMaster-Carr, Elmhurst, IL, USA) were cut to length and bonded to the contact pads using silver epoxy (8331 Silver Conductive Epoxy Adhesive, MG Chemicals, Ontario, Canada) to form electrical connections to the pseudoreference electrode leads. The stability of four pseudoreference electrodes was evaluated by measuring their open circuit potential over 120 hours using a multi-channel potentiostat (PalmSens4 with MUX8-R2 Multiplexer, PalmSens, Houten, Netherlands) versus Ag/AgCl/3 M KCl reference electrodes (BASi Research Products, West Lafayette, IN, USA) in anoxic freshwater media bubbled with 50 kPa of 80% nitrogen and 20% carbon dioxide mixed gas. Measurements were conducted inside a Faraday cage.

Potential Calibration of the Pseudoreference Electrodes

Single three-electrode electrochemical cells were fabricated following the same procedures and materials as the 2 × 4 device arrays and diced to final dimensions of 20 mm × 20 mm. Titanium wires (Ultra-Corrosion-Resistant Grade 2 Titanium Wire, 0.025-inch diameter, McMaster-Carr, Elmhurst, IL, USA) were cut to length and bonded to the contact pads using silver epoxy (8331 Silver Conductive Epoxy Adhesive, MG Chemicals, Ontario, Canada) to establish electrical connections to the electrode leads. Single three-electrode cells were inserted into 100-mL bulk reactors along with standard Ag/AgCl/3 M KCl reference electrodes (BASi Research Products, West Lafayette, IN, USA). The ferricyanide/ferrocyanide redox couple was used as an internal redox standard by preparing a 1 mM potassium ferricyanide/potassium ferrocyanide solution in freshwater media. Cyclic voltammograms were recorded at a scan rate of 10 mV s⁻¹ using a multi-channel potentiostat (PalmSens4 with MUX8-R2 Multiplexer, PalmSens, Houten, Netherlands) versus both the Ag/AgCl/Nafion pseudoreference electrode and standard Ag/AgCl/3M KCl reference electrodes. Measurements were performed in both freshwater media for background current measurement and ferri/ferrocyanide solutions. All solutions were bubbled with a 50 kPa of 80% nitrogen and 20% carbon dioxide mixed gas for 90 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen. Experiments were conducted inside a Faraday cage to minimize background noise. Three independent samples were tested, with three repeated cyclic voltammetry measurements performed for each sample under each testing condition. Cyclic voltammogram data were analyzed using PSTrace Software (PalmSens), and oxidation and reduction peaks were identified after subtracting the average background current from the ferri/ferrocyanide cyclic voltammograms. The electrode potential was calibrated by measuring the difference in half-wave potentials between the pseudoreference electrodes and the standard Ag/AgCl/3M KCl reference electrodes.

Culture and Characterization of the Model EEU Organism Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 Inside the µ-BEC Platform

Isopropyl alcohol, ethyl alcohol, and basal freshwater medium were prepared in sterile glass serum bottles and purged with 50 kPa of 80% nitrogen and 20% carbon dioxide for 30 minutes prior to use. The µ-BEC platform was loaded inside an anaerobic chamber using a syringe pump (KD Scientific, Holliston, MA, USA) with 1 mL of isopropyl alcohol at a flow rate of 10 µL s⁻¹ to remove trapped gas bubbles, followed by 2.5 mL of ethyl alcohol for sterilization. The platform was left to sit with the ethyl alcohol solution for 30 minutes, after which it was flushed with 2.5 mL of purged freshwater medium at a flow rate of 10 µL s⁻¹.

Cyclic voltammograms were recorded using a multi-channel potentiostat (PalmSens4 with MUX8-R2 Multiplexer, PalmSens, Houten, Netherlands) under both illuminated and dark conditions. Illumination was provided by a 60 W incandescent light bulb positioned 25 cm above the platform. Rhodopseudomonas palustris TIE-1 cells were cultured photoautotrophically in freshwater medium with 80% hydrogen and 20% carbon dioxide in sealed sterile glass serum bottles at 30°C with illumination from a 60 W incandescent light bulb positioned 25 cm above the bottles. Cultures were harvested at an optical density of 1.5 (OD₆₆₀ = 1.5), centrifuged at 5000 × g, washed three times with basal freshwater medium, and resuspended to a final optical density of 5.5 (OD₆₆₀ = 5.5). Prior to inoculation, the cell suspension was purged with 5 kPa of 80% nitrogen and 20% carbon dioxide for 30 minutes.

Approximately 0.5 mL of concentrated TIE-1 culture was loaded into the µ-BEC platform inside the anaerobic chamber at a flow rate of 10 µL min⁻¹. Cyclic voltammograms were recorded at 10 mV s⁻¹ under both illuminated and dark conditions. Following initial measurements, the working electrodes were poised at +100 mV vs. SHE for approximately 96 hours under continuous illumination from a 60 W incandescent light bulb positioned 25 cm above the platform to facilitate biofilm formation. After the incubation period, light on/off chronoamperometry experiments were performed in 30-second intervals over a 300-second total duration with three repeated measurements per electrochemical cell. Cyclic voltammograms were then recorded again under both illuminated and dark conditions at 10 mV s⁻¹.

After electrochemical characterization, unattached and planktonic cells were removed by flushing the platform with approximately 0.5 mL of freshwater medium (pre-purged with 5 kPa of 80% nitrogen and 20% carbon dioxide for 30 minutes) at a flow rate of 10 µL min⁻¹ inside the anaerobic chamber. Final cyclic voltammograms and light on/off chronoamperometry measurements were recorded as described previously.

Cyclic voltammetry data were analyzed using PSTrace Software (PalmSens). The average background current obtained in abiotic freshwater medium was subtracted from the inoculated voltammograms. Data were smoothed using the software’s smoothing function set to the high smoothing factor. Oxidation and reduction peaks were identified using the Autodetect Peaks function. Chronoamperometry data were analyzed using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA).

Brightfield transmitted light images of each µ-BEC unit were acquired using an inverted microscope (Axio Observer Z.1, Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a 2.5× objective (EC Plan-NEOFLUAR 2.5×/0.085 WD = 8.8 mm, Zeiss) at multiple time points: before cell inoculation, after inoculation, after the 96-hour incubation, and after planktonic cell removal.

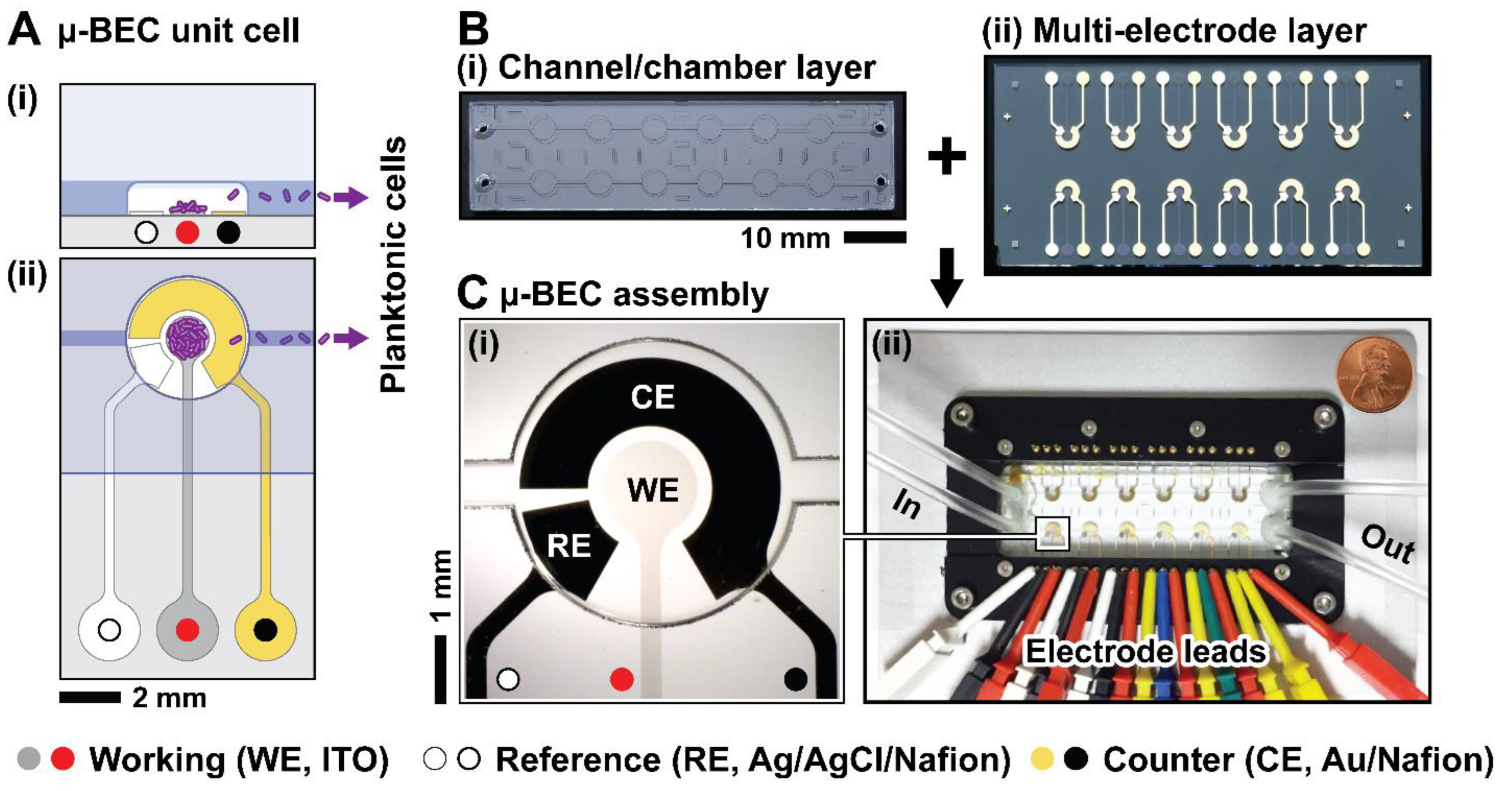

Figure 1.

Microfluidic bio-electrochemical cell (µ-BEC) platform. (A) Side (i) and top (ii) views of single µ-BEC; (B) Fabricated microfluidic channel layer (i) and multi-electrode layer (ii); (C) Inset of fabricated µ-BEC (i) and assembled device inside the microscopy and electrochemical measurements compatible holder.

Figure 1.

Microfluidic bio-electrochemical cell (µ-BEC) platform. (A) Side (i) and top (ii) views of single µ-BEC; (B) Fabricated microfluidic channel layer (i) and multi-electrode layer (ii); (C) Inset of fabricated µ-BEC (i) and assembled device inside the microscopy and electrochemical measurements compatible holder.

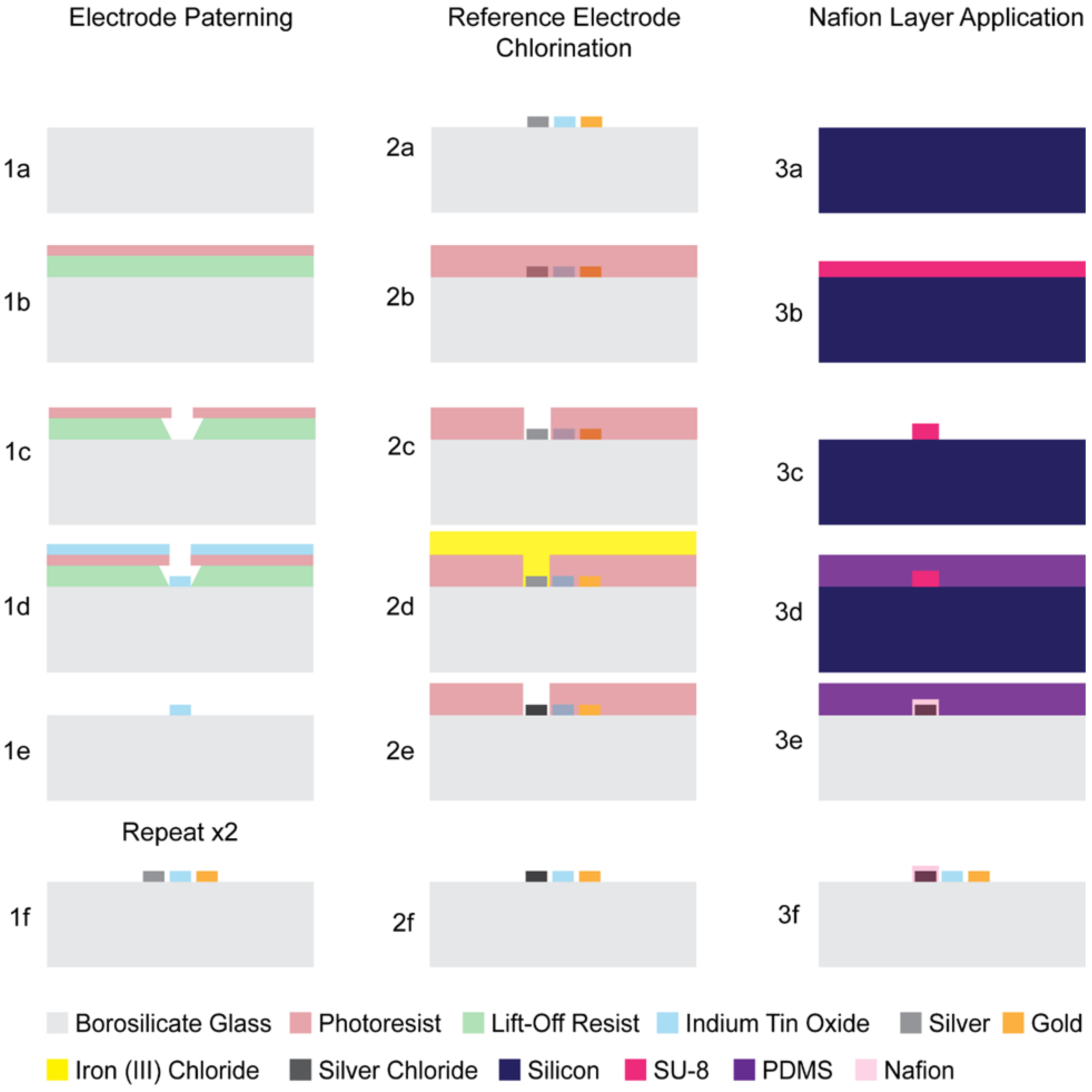

Figure 2.

µ-BEC platform fabrication steps. 1(a-f) electrode layer lithography, metallization, and lift-off; 2(a-f) reference electrode chlorination; 3(a-f) Nafion layer application.

Figure 2.

µ-BEC platform fabrication steps. 1(a-f) electrode layer lithography, metallization, and lift-off; 2(a-f) reference electrode chlorination; 3(a-f) Nafion layer application.

Figure 4.

Open circuit potential of pseudoreference electrode in freshwater media. Average value across three samples with shaded area representing ± standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Open circuit potential of pseudoreference electrode in freshwater media. Average value across three samples with shaded area representing ± standard deviation.

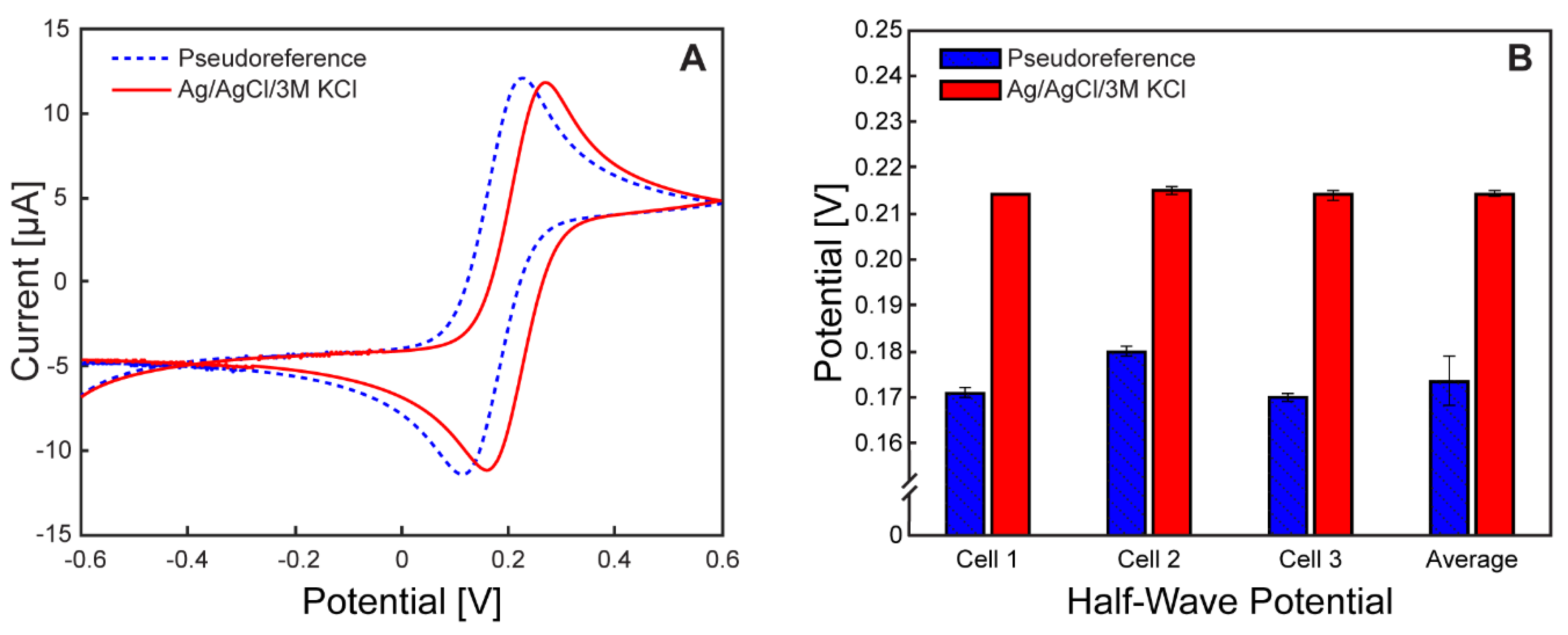

Figure 5.

Pseudoreference electrode potential calibration. Cyclic voltammograms at 10 mV/s of 1 mM ferri/ferrocyanide in 1 M potassium chloride solution versus the pseudoreference electrode (doted blue) and Ag/AgCl/3M KCl (red); B Average half-wave potential values for each tested electrochemical cell and overall average across the three cells of the pseudoreference electrode (blue) and Ag/AgCl/3M KCl (red). Error bars represent +/- standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Pseudoreference electrode potential calibration. Cyclic voltammograms at 10 mV/s of 1 mM ferri/ferrocyanide in 1 M potassium chloride solution versus the pseudoreference electrode (doted blue) and Ag/AgCl/3M KCl (red); B Average half-wave potential values for each tested electrochemical cell and overall average across the three cells of the pseudoreference electrode (blue) and Ag/AgCl/3M KCl (red). Error bars represent +/- standard deviation.

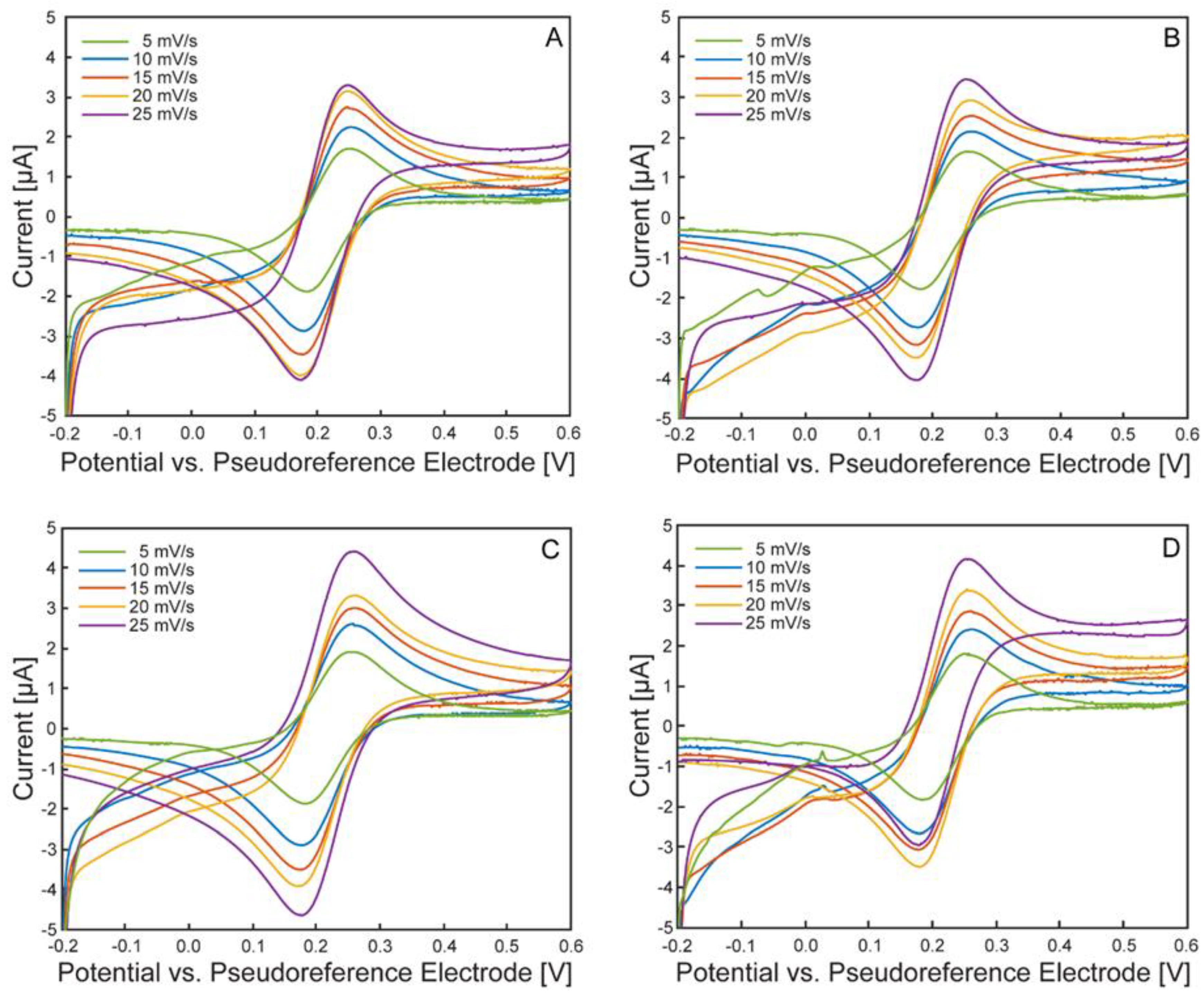

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammograms of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe within each µ-BEC cell. Scan rates: 5 mV/s (green), 10 mV/s (blue), 15 mV/s (red), 20 mV/s (yellow) and 25 mV/s (purple). Subfigures A-D correspond to µ-BEC cells 1-4 on the platform.

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammograms of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe within each µ-BEC cell. Scan rates: 5 mV/s (green), 10 mV/s (blue), 15 mV/s (red), 20 mV/s (yellow) and 25 mV/s (purple). Subfigures A-D correspond to µ-BEC cells 1-4 on the platform.

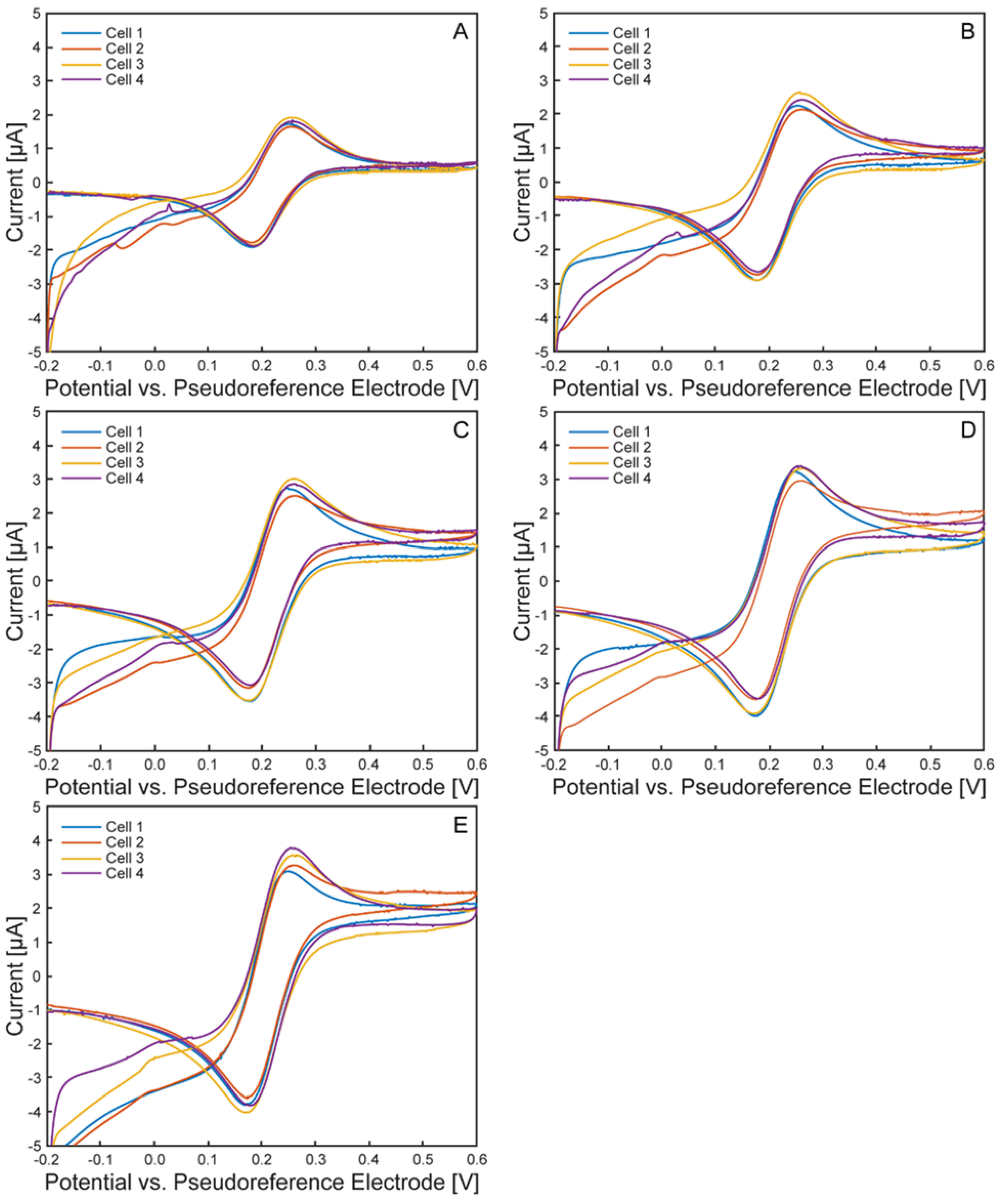

Figure 7.

Cyclic voltammograms at different scan rates of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe. µ-BEC cell 1 (blue), cell 2 (red), cell 3 (yellow), cell 4 (purple). Subfigures A-E correspond to scan rates of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 mV/s.

Figure 7.

Cyclic voltammograms at different scan rates of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe. µ-BEC cell 1 (blue), cell 2 (red), cell 3 (yellow), cell 4 (purple). Subfigures A-E correspond to scan rates of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 mV/s.

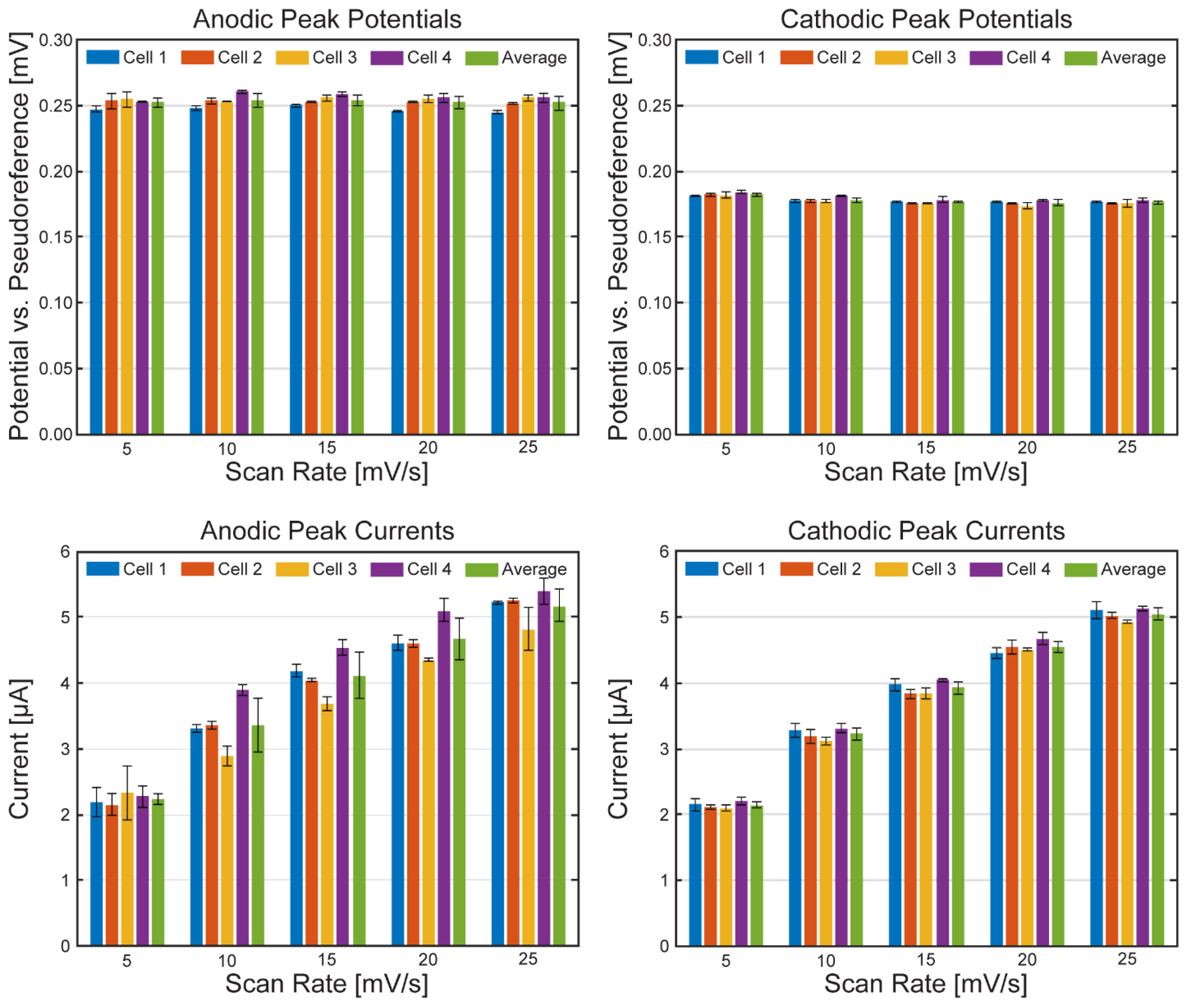

Figure 8.

Average anodic and cathodic peak potentials and currents of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe. Cell 1 (blue), cell 2 (red), cell 3 (yellow), cell 4 (purple), average across all cells (green). Error bars represent +/- standard deviation.

Figure 8.

Average anodic and cathodic peak potentials and currents of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe. Cell 1 (blue), cell 2 (red), cell 3 (yellow), cell 4 (purple), average across all cells (green). Error bars represent +/- standard deviation.

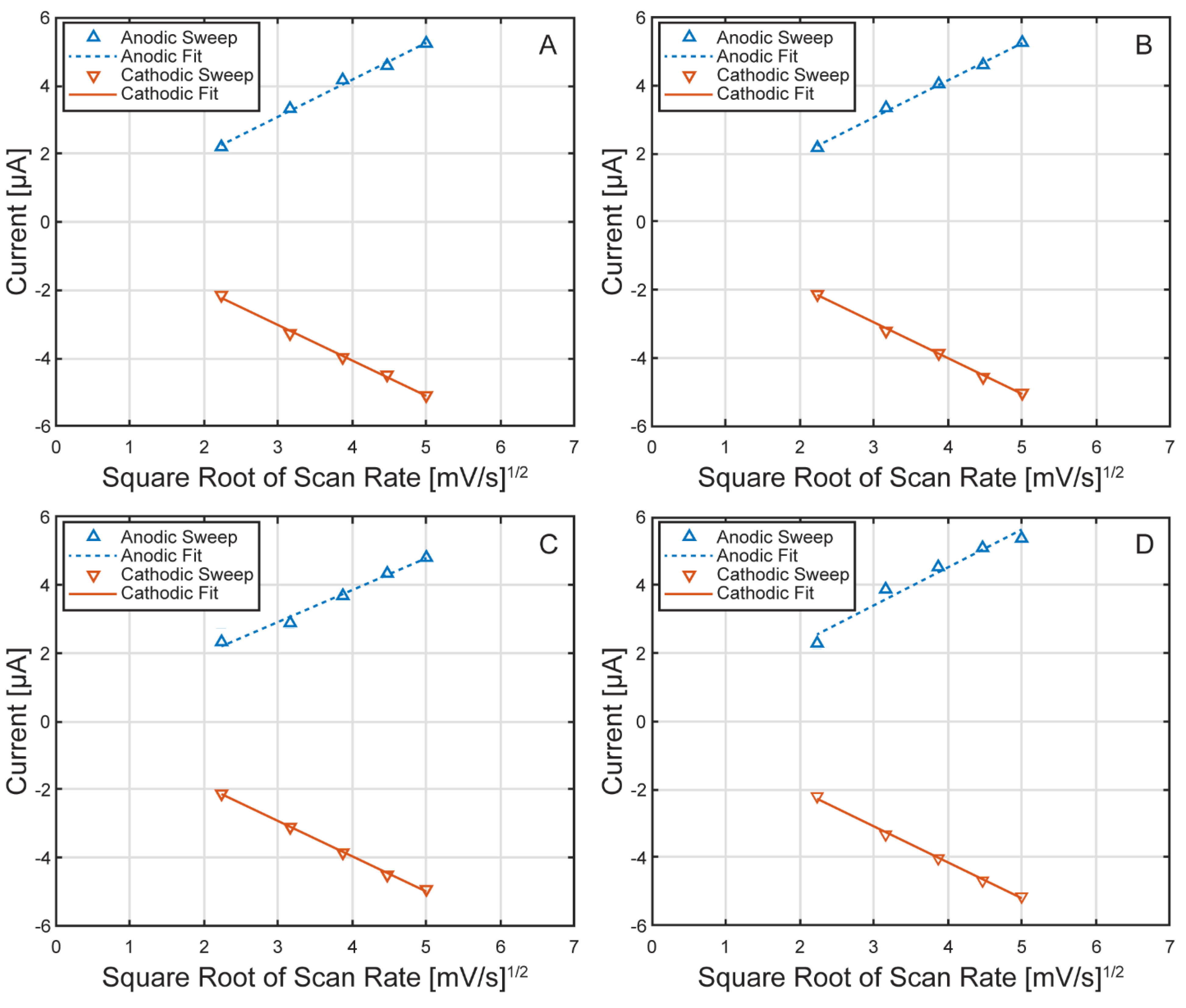

Figure 9.

Randles–Ševčík fits for each µ-BEC cell. Linear regression fits of the anodic (doted blue) and cathodic (red) sweeps of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe inside the µ-BEC platform in cell 1 (A), cell 2 (B), cell 3 (C), and cell 4 (D).

Figure 9.

Randles–Ševčík fits for each µ-BEC cell. Linear regression fits of the anodic (doted blue) and cathodic (red) sweeps of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe inside the µ-BEC platform in cell 1 (A), cell 2 (B), cell 3 (C), and cell 4 (D).

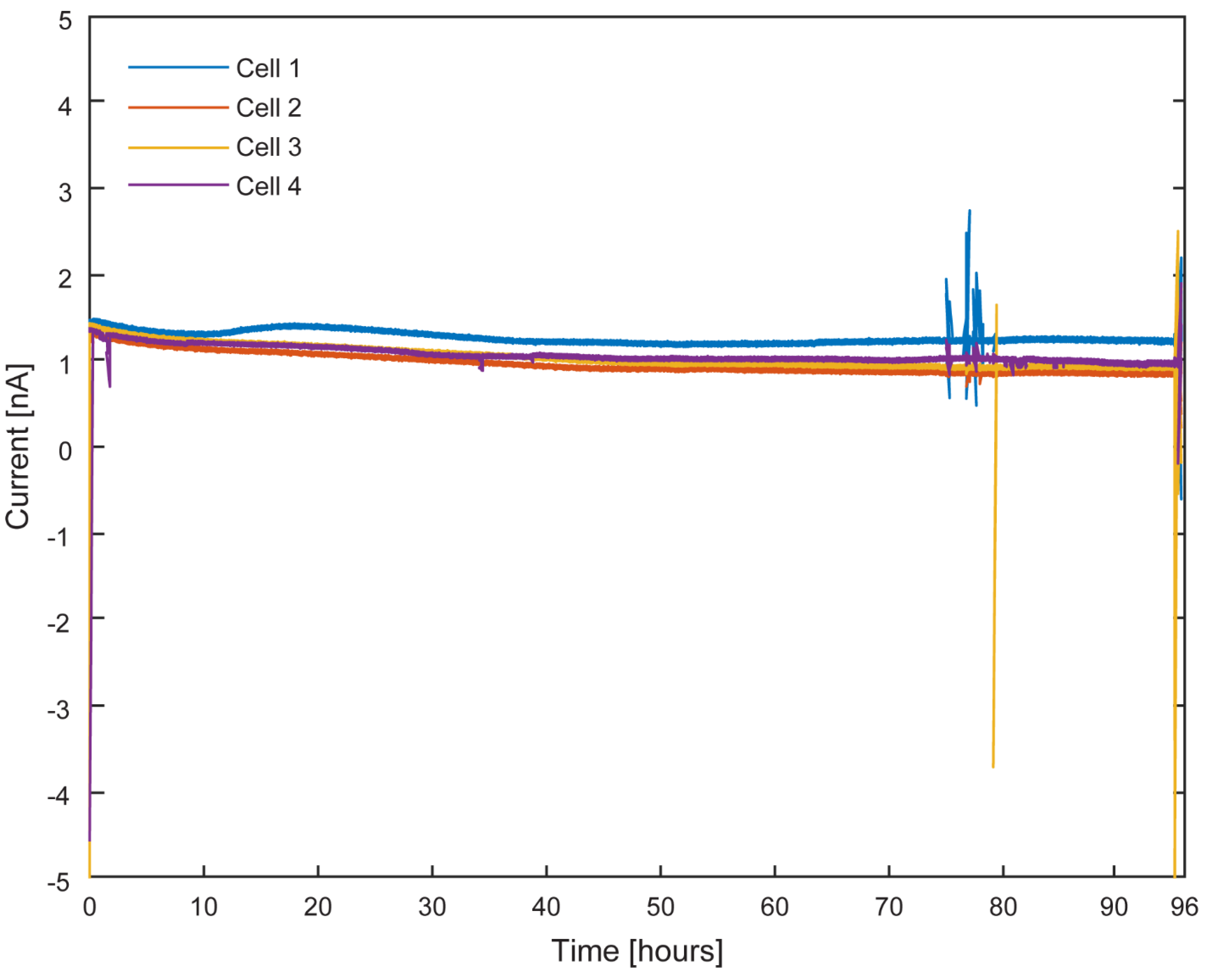

Figure 10.

Electron uptake by TIE-1 cells under illuminated conditions. 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. cell 1 (blue), cell 2 (red), cell 3 (yellow), cell 4 (purple).

Figure 10.

Electron uptake by TIE-1 cells under illuminated conditions. 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. cell 1 (blue), cell 2 (red), cell 3 (yellow), cell 4 (purple).

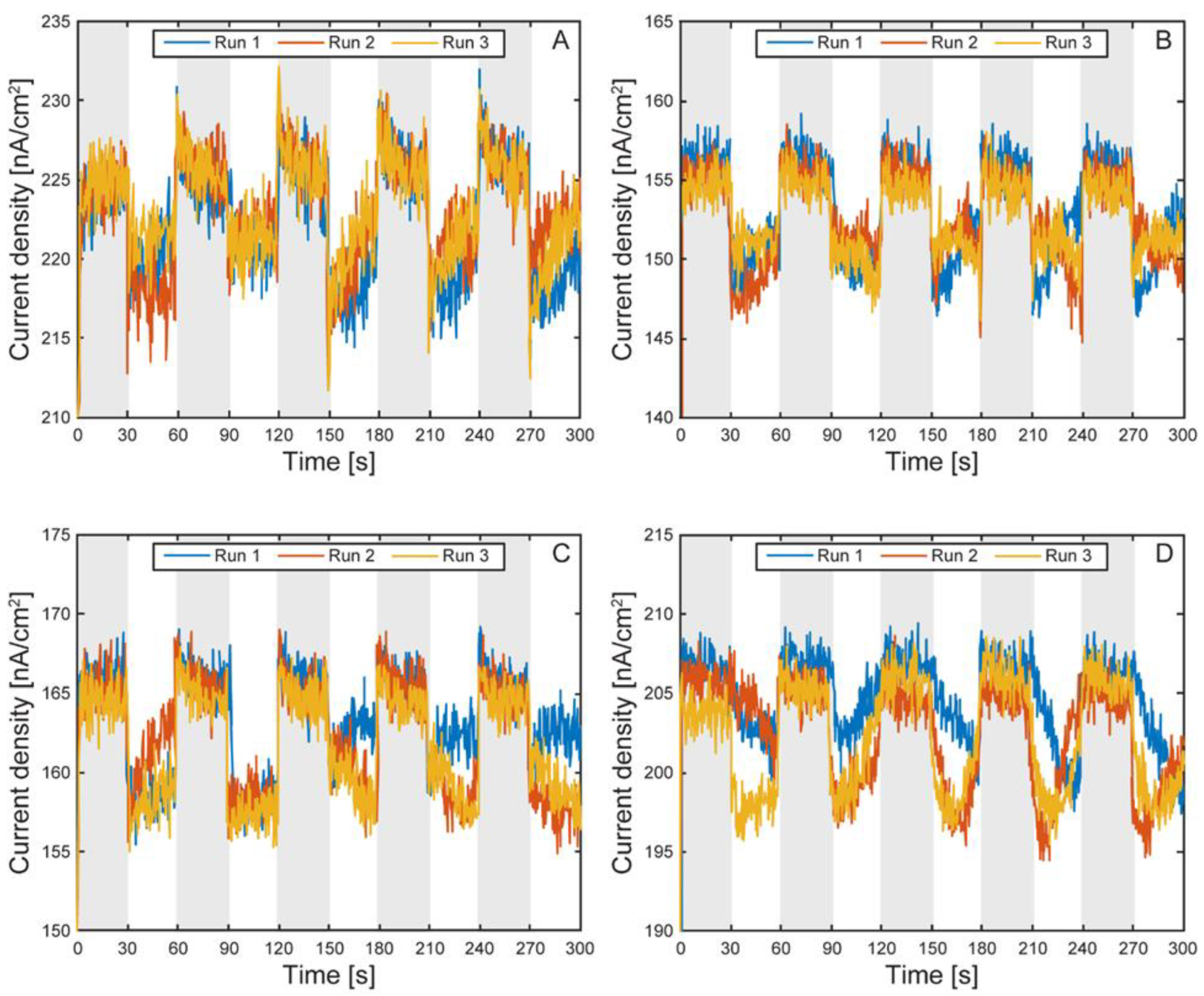

Figure 11.

Electron uptake by TIE-1 cells under light on and off conditions with planktonic cells. Overlayed runs of light on (white region) and light off (shaded region) under 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. Cell 1 (A), cell 2 (B), cell 3 (C), cell 4 (D).

Figure 11.

Electron uptake by TIE-1 cells under light on and off conditions with planktonic cells. Overlayed runs of light on (white region) and light off (shaded region) under 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. Cell 1 (A), cell 2 (B), cell 3 (C), cell 4 (D).

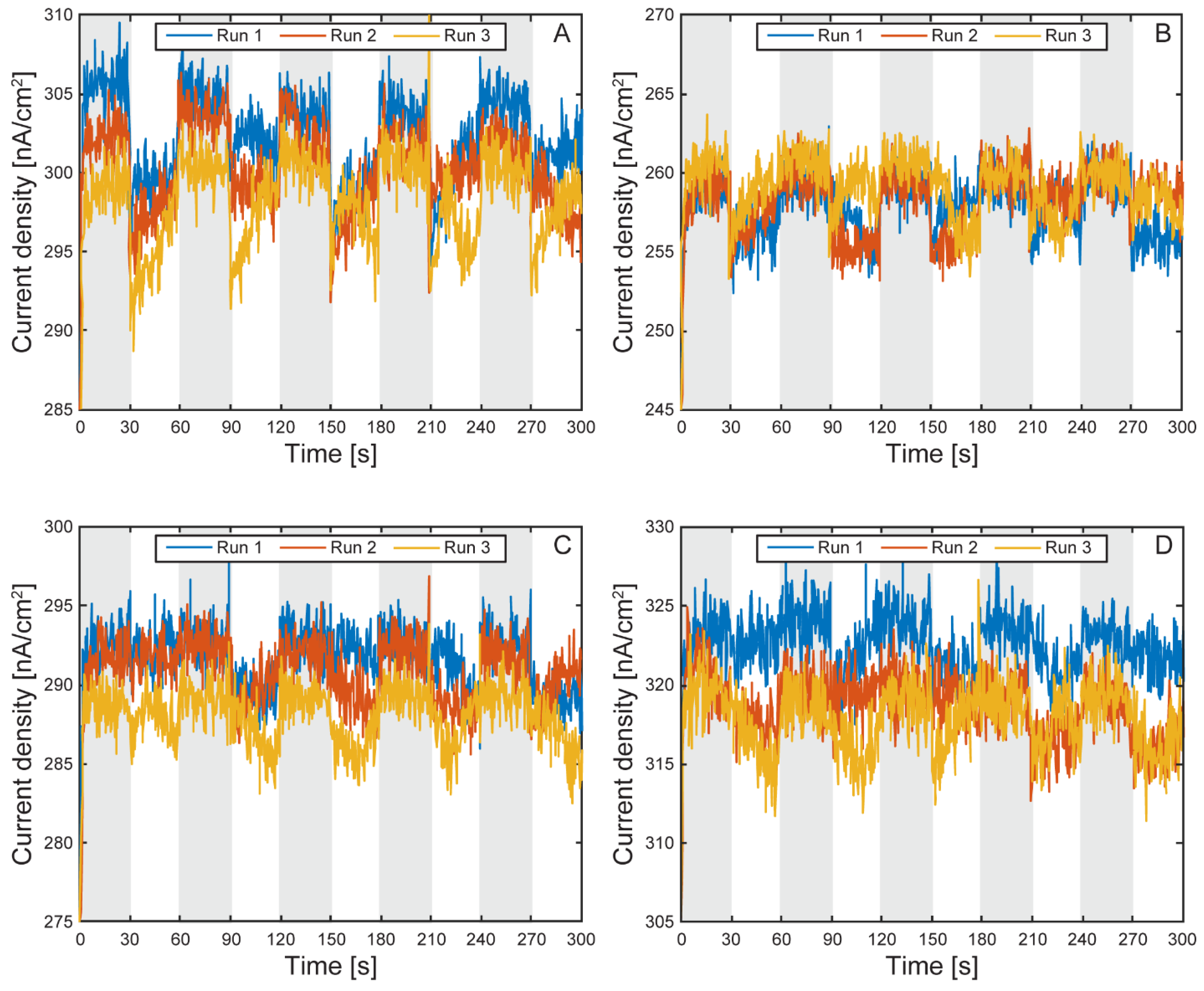

Figure 12.

Electron uptake by TIE-1 cells under light on and off conditions without planktonic cells. Overlayed runs of light on (white region) and light off (shaded region) under 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. Cell 1 (A), cell 2 (B), cell 3 (C), cell 4 (D).

Figure 12.

Electron uptake by TIE-1 cells under light on and off conditions without planktonic cells. Overlayed runs of light on (white region) and light off (shaded region) under 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. Cell 1 (A), cell 2 (B), cell 3 (C), cell 4 (D).

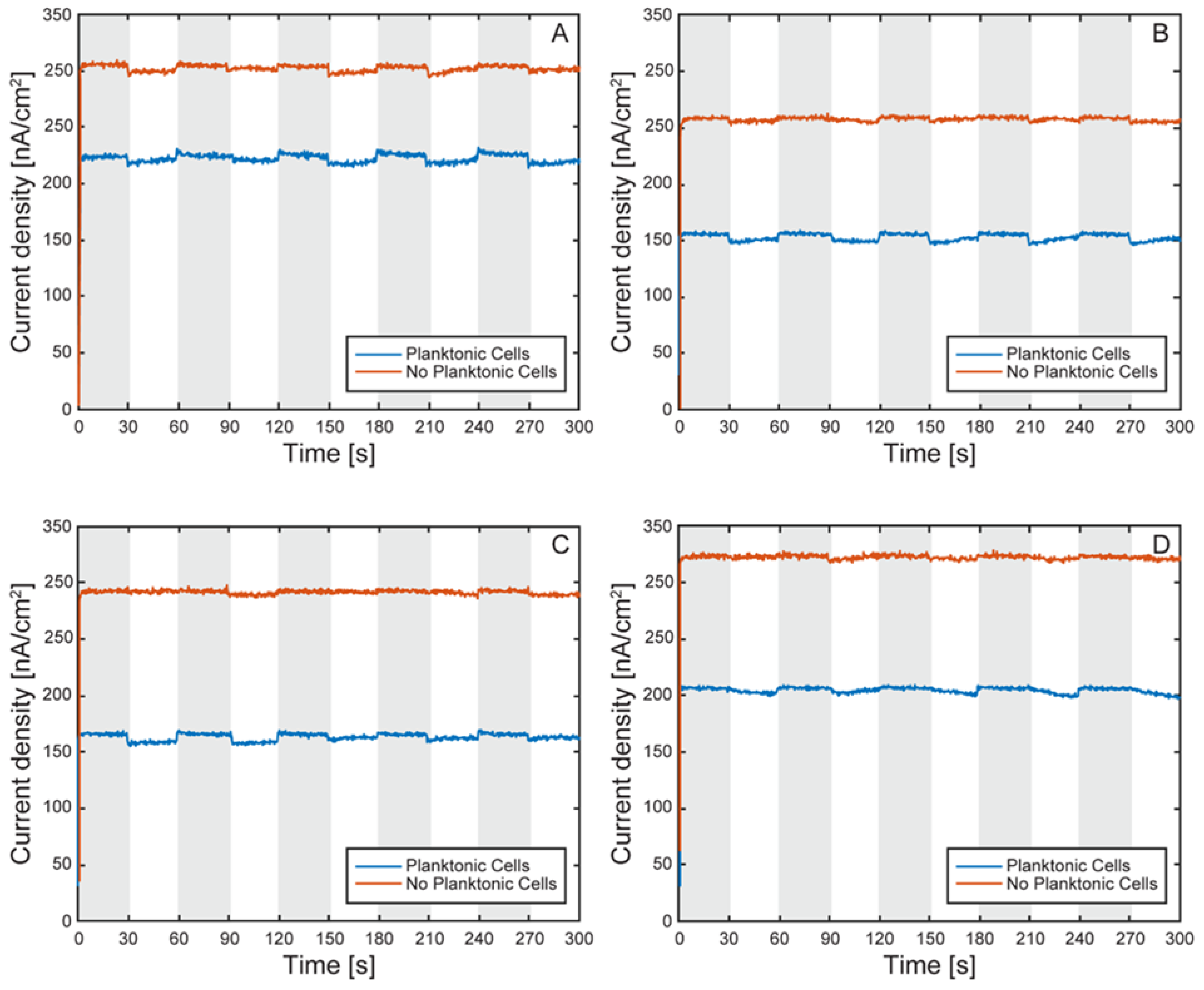

Figure 13.

Electron uptake comparison by TIE-1 cells under light on and off conditions with and without planktonic cells. Light on (white region) and light off (shaded region) under 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. Cell 1 (A), cell 2 (B), cell 3 (C), cell 4 (D).

Figure 13.

Electron uptake comparison by TIE-1 cells under light on and off conditions with and without planktonic cells. Light on (white region) and light off (shaded region) under 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. Cell 1 (A), cell 2 (B), cell 3 (C), cell 4 (D).

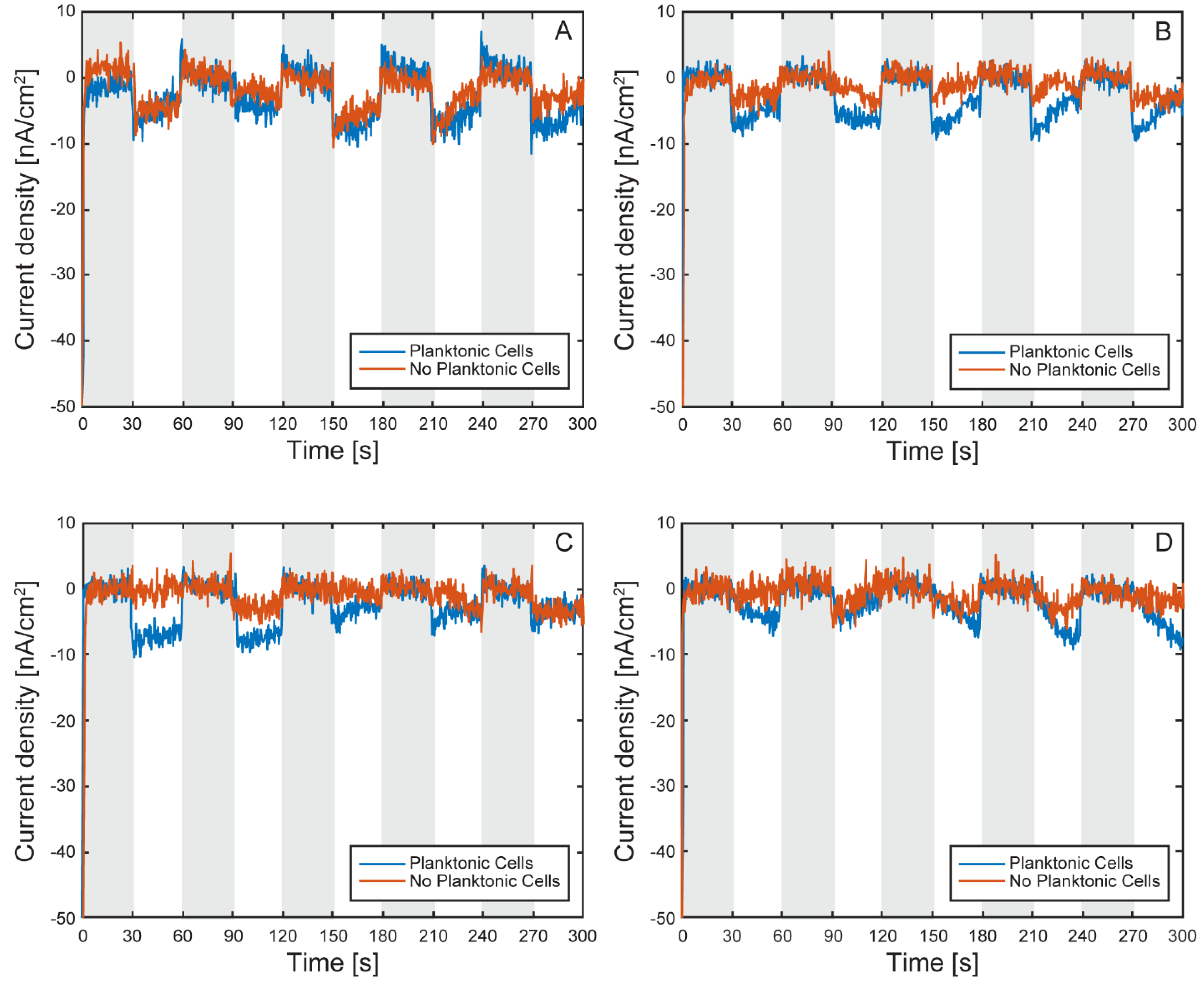

Figure 14.

Normalized electron uptake comparison by TIE-1 cells under light on and off conditions with and without planktonic cells. Light on (white region) and light off (shaded region) under 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. Cell 1 (A), cell 2 (B), cell 3 (C), cell 4 (D).

Figure 14.

Normalized electron uptake comparison by TIE-1 cells under light on and off conditions with and without planktonic cells. Light on (white region) and light off (shaded region) under 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. Cell 1 (A), cell 2 (B), cell 3 (C), cell 4 (D).

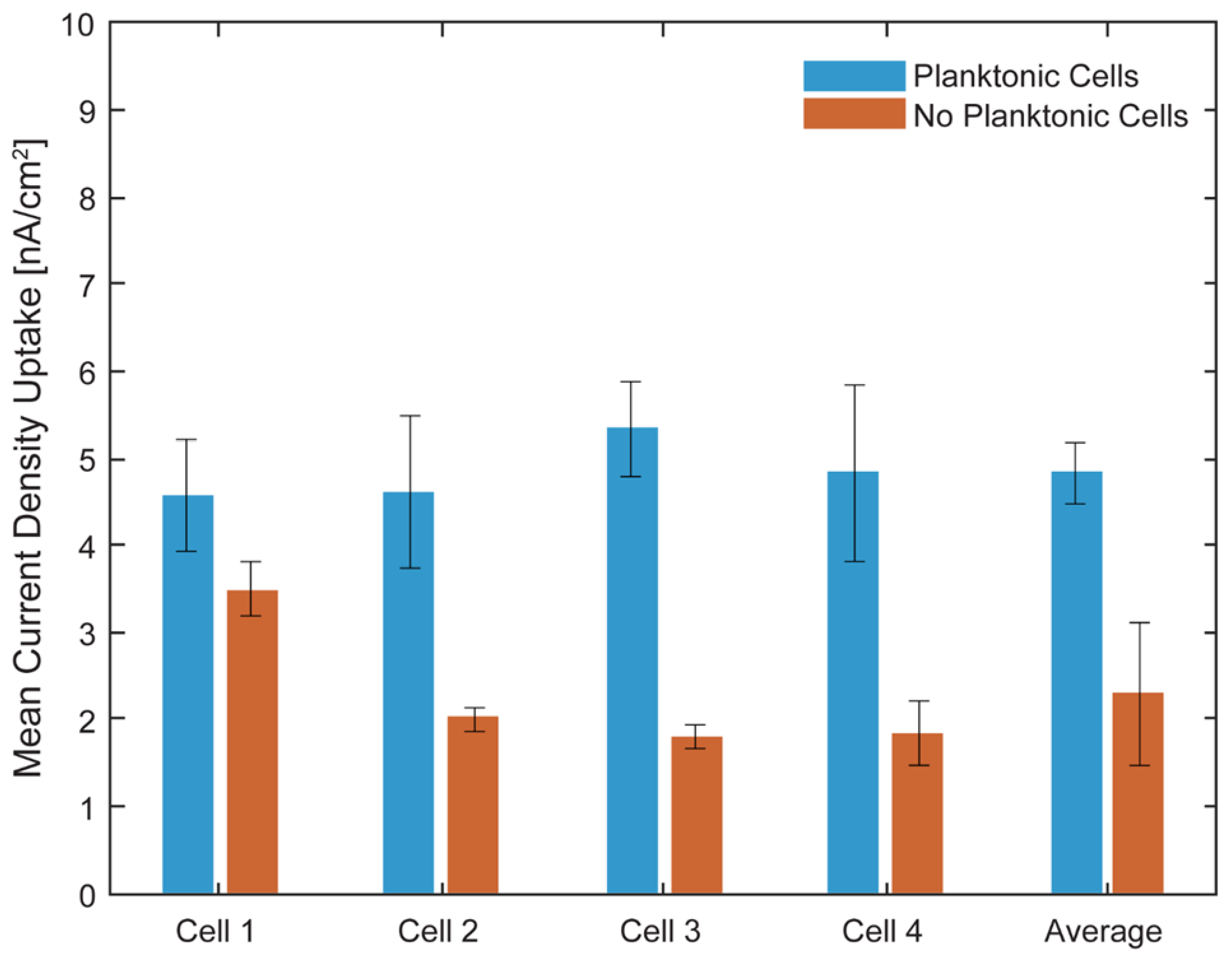

Figure 15.

Average current uptake by TIE-1 cells under illuminated conditions versus dark conditions. With planktonic cells (blue) or without planktonic cells (red) under 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Figure 15.

Average current uptake by TIE-1 cells under illuminated conditions versus dark conditions. With planktonic cells (blue) or without planktonic cells (red) under 60 W incandescent light-bulb illumination and working electrode poised at +100 mV vs SHE. Error bars represent standard deviation.

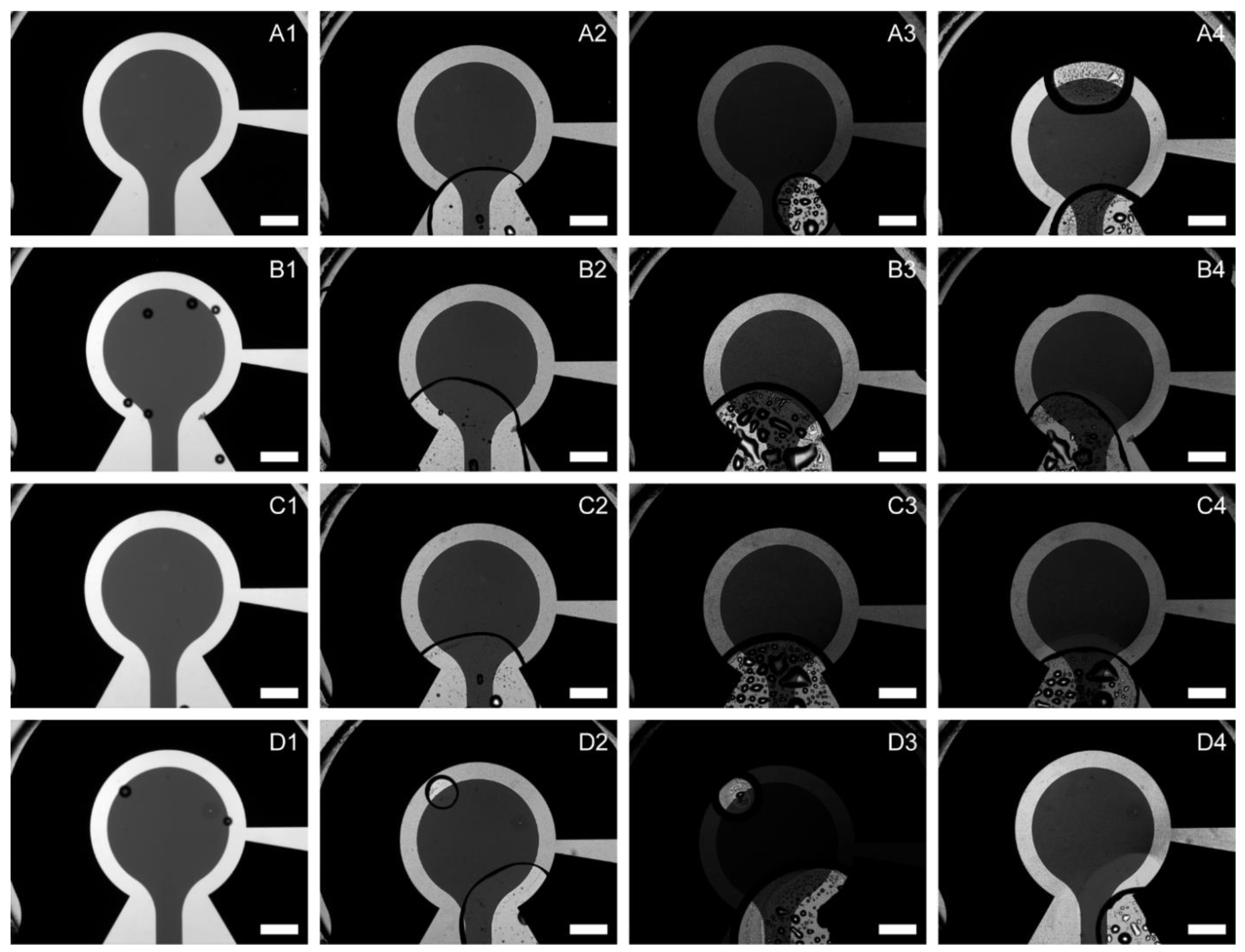

Figure 16.

Brightfield microscopy images of μ-BECs. Cells 1-4 (subfigures A-D) in the µ-BEC platform before loading with TIE-1 cells (1), after loading with TIE-1 cells on Day 0 (2), after loading with TIE-1 cells on Day 4 (3), after removal of planktonic cells on Day 4 (4).

Figure 16.

Brightfield microscopy images of μ-BECs. Cells 1-4 (subfigures A-D) in the µ-BEC platform before loading with TIE-1 cells (1), after loading with TIE-1 cells on Day 0 (2), after loading with TIE-1 cells on Day 4 (3), after removal of planktonic cells on Day 4 (4).

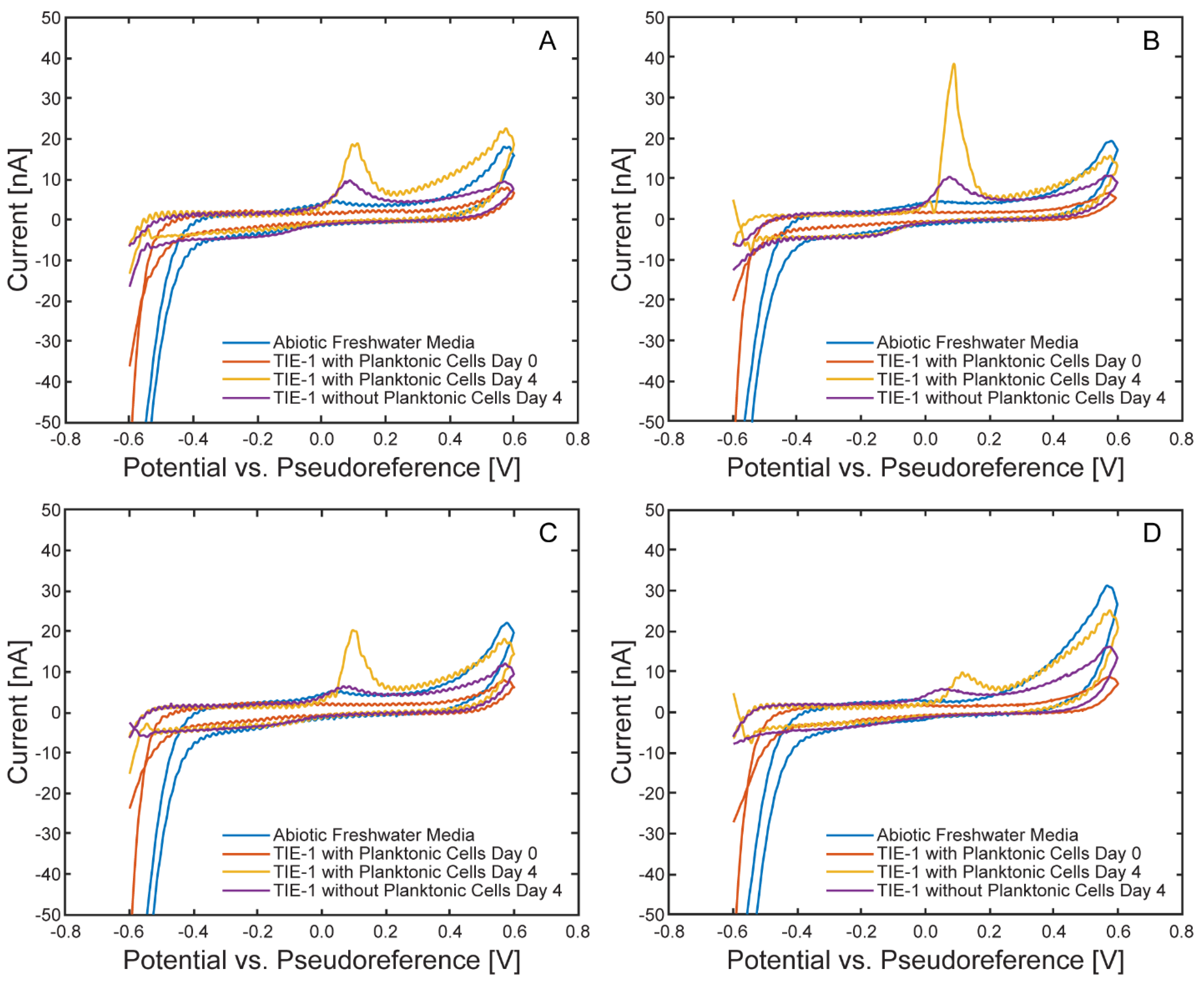

Figure 17.

Comparison of cyclic voltammograms within each μ-BEC cell under illuminated conditions. Cyclic voltammograms at 10 mV/s of abiotic freshwater media (blue), TIE-1 with planktonic cells on Day 0 (red), TIE-1 with planktonic cells on Day 4 (yellow), TIE-1 without planktonic cells on Day 4 (purple) in the µ-BEC platform cells 1-4 (A-D).

Figure 17.

Comparison of cyclic voltammograms within each μ-BEC cell under illuminated conditions. Cyclic voltammograms at 10 mV/s of abiotic freshwater media (blue), TIE-1 with planktonic cells on Day 0 (red), TIE-1 with planktonic cells on Day 4 (yellow), TIE-1 without planktonic cells on Day 4 (purple) in the µ-BEC platform cells 1-4 (A-D).

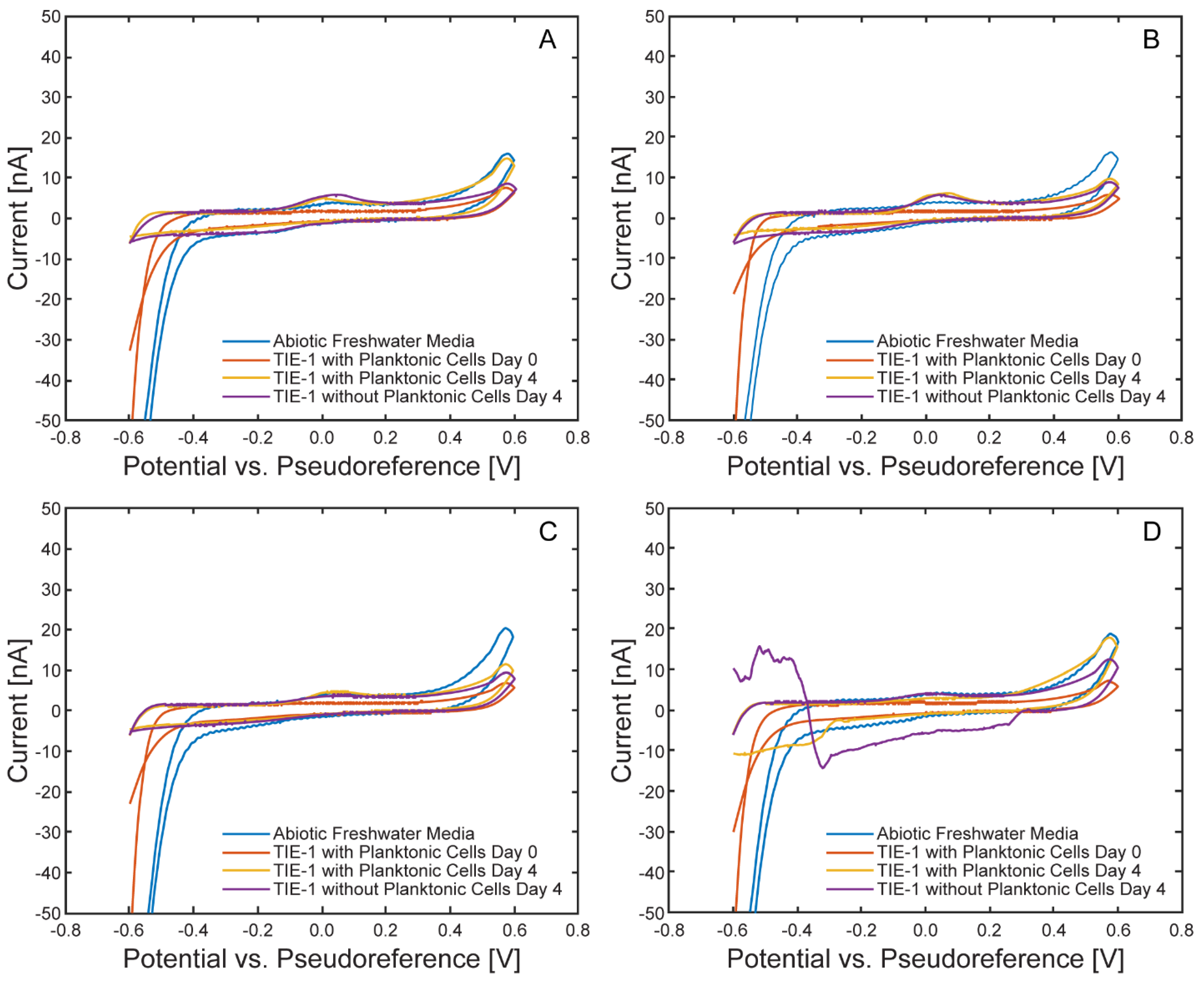

Figure 18.

Comparison of cyclic voltammograms within each μ-BEC cell under dark conditions. Cyclic voltammograms at 10 mV/s of abiotic freshwater media (blue), TIE-1 with planktonic cells on Day 0 (red), TIE-1 with planktonic cells on Day 4 (yellow), TIE-1 without planktonic cells on Day 4 (purple) in the µ-BEC platform cells 1-4 (A-D).

Figure 18.

Comparison of cyclic voltammograms within each μ-BEC cell under dark conditions. Cyclic voltammograms at 10 mV/s of abiotic freshwater media (blue), TIE-1 with planktonic cells on Day 0 (red), TIE-1 with planktonic cells on Day 4 (yellow), TIE-1 without planktonic cells on Day 4 (purple) in the µ-BEC platform cells 1-4 (A-D).

Table 1.

Anodic and cathodic peak potentials of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe inside the µ-BEC platform. Potential reported versus the pseudoreference electrode.

Table 1.

Anodic and cathodic peak potentials of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe inside the µ-BEC platform. Potential reported versus the pseudoreference electrode.

| Scan Rate |

Anodic Peak Potential [mV] |

Cathodic Peak Potential [mV] |

| Average |

Standard Deviation |

Average |

Standard Deviation |

| 5 mV/s |

252 |

3.25 |

182 |

1.29 |

| 10 mV/s |

254 |

5.21 |

178 |

1.90 |

| 15 mV/s |

254 |

3.75 |

177 |

1.12 |

| 20 mV/s |

252 |

4.50 |

176 |

2.05 |

| 25 mV/s |

252 |

5.20 |

176 |

1.13 |

Table 2.

Anodic and cathodic peak currents of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe inside the µ-BEC platform. Potential reported versus the pseudoreference electrode.

Table 2.

Anodic and cathodic peak currents of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe inside the µ-BEC platform. Potential reported versus the pseudoreference electrode.

| Scan Rate |

Anodic Peak Current [µA] |

Cathodic Peak Potential [µA] |

| Average |

Standard Deviation |

Average |

Standard Deviation |

| 5 mV/s |

2.24 |

0.08 |

2.15 |

0.05 |

| 10 mV/s |

3.36 |

0.41 |

3.23 |

0.09 |

| 15 mV/s |

4.12 |

0.35 |

3.93 |

0.10 |

| 20 mV/s |

4.67 |

0.31 |

4.55 |

0.09 |

| 25 mV/s |

5.17 |

0.25 |

5.05 |

0.09 |

Table 3.

Randles–Ševčík linear regression fit constants and R-squared values for the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe.

Table 3.

Randles–Ševčík linear regression fit constants and R-squared values for the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe.

| Cell Number |

Anodic Fit Constant |

Anodic R-Squared |

Cathodic Fit Constant |

Cathodic R-Squared |

| 1 |

3.30E-05 |

9.994E-01 |

3.21E-05 |

9.997E-01 |

| 2 |

3.29E-05 |

9.995E-01 |

3.17E-05 |

9.997E-01 |

| 3 |

3.05E-05 |

9.992E-01 |

3.13E-05 |

9.997E-01 |

| 4 |

3.58E-05 |

9.973E-01 |

3.27E-05 |

9.998E-01 |

| Average |

3.30E-05 |

9.989E-01 |

3.20E-05 |

9.997E-01 |

| Standard Deviation |

2.17E-06 |

1.041E-03 |

6.03E-07 |

5.00E-05 |

| CV (%) |

6.56 |

0.10 |

1.88 |

0.01 |

Table 4.

Coefficients of variance for anodic and cathodic peak potentials and currents of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe inside the µ-BEC platform.

Table 4.

Coefficients of variance for anodic and cathodic peak potentials and currents of the ferri/ferrocyanide redox probe inside the µ-BEC platform.

| Scan Rate |

Coefficient of Variance [%] |

| Anodic Peak Potential |

Anodic Peak Current |

Cathodic Peak Potential |

Cathodic Peak Current |

| 5 mV/s |

1.29 |

3.46 |

0.71 |

2.33 |

| 10 mV/s |

2.05 |

12.25 |

1.06 |

2.65 |

| 15 mV/s |

1.47 |

8.51 |

0.64 |

2.61 |

| 20 mV/s |

1.79 |

6.74 |

1.17 |

2.01 |

| 25 mV/s |

2.06 |

4.76 |

0.64 |

1.77 |

| Average |

1.73 |

7.14 |

0.84 |

2.27 |