Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

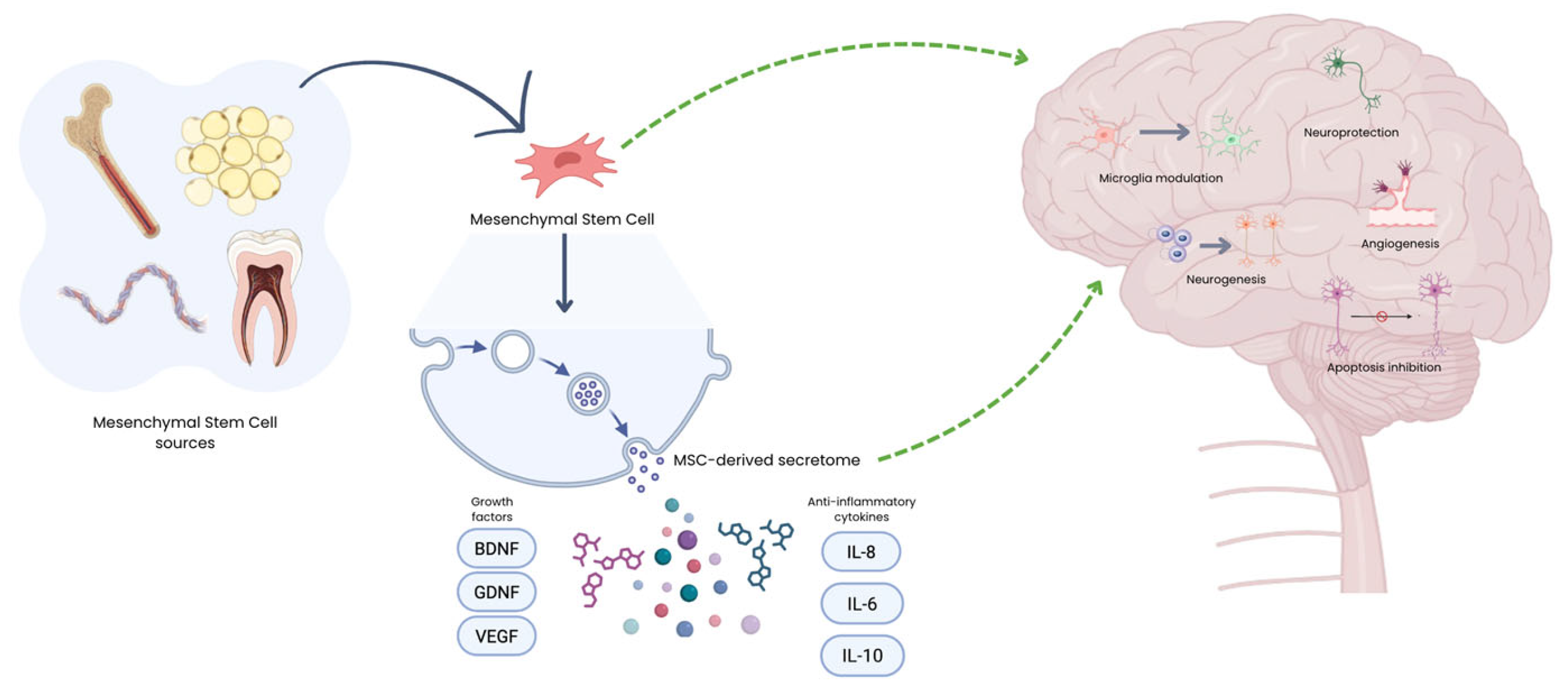

2. MSC’s Therapies for Specific Neurological Disorders

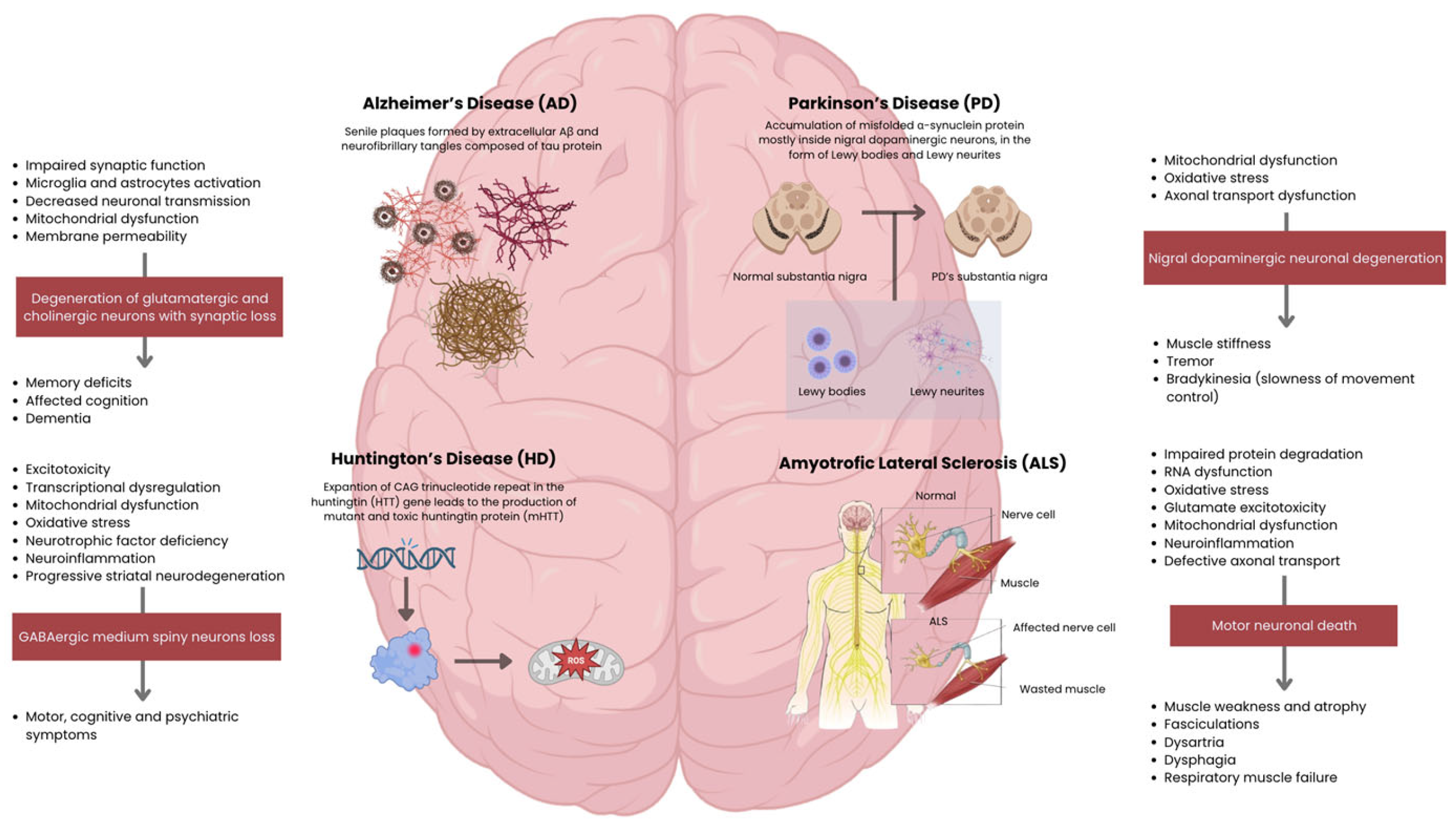

2.1. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

2.2. Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

2.3. Huntington’s Disease (HD)

2.4. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wang, S., et al., The Expanding Burden of Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Unmet Medical and Social Need. Aging Dis, 2024. 16(5): p. 2937-2952. [CrossRef]

- Deokate, N., et al., A Comprehensive Review of the Role of Stem Cells in Neuroregeneration: Potential Therapies for Neurological Disorders. Cureus, 2024. 16(8): p. e67506. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K., et al., A Review of the Common Neurodegenerative Disorders: Current Therapeutic Approaches and the Potential Role of Bioactive Peptides. Curr Protein Pept Sci, 2024. 25(7): p. 507-526. [CrossRef]

- Giovannelli, L., et al., Mesenchymal stem cell secretome and extracellular vesicles for neurodegenerative diseases: Risk-benefit profile and next steps for the market access. Bioactive Materials, 2023. 29: p. 16-35. [CrossRef]

- Chitnis, T. and H.L. Weiner, CNS inflammation and neurodegeneration. J Clin Invest, 2017. 127(10): p. 3577-3587. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y., et al., Interactions of glial cells with neuronal synapses, from astrocytes to microglia and oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Glia, 2023. 71: p. 1383-1401. [CrossRef]

- Demmings, M., et al., (Re)building the nervous system: A review of neuron–glia interactions from development to disease. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2024. 169. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., et al., Emerging Role of Neuron-Glia in Neurological Disorders: At a Glance. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2022. 2022.

- Tesco, G. and S. Lomoio, Pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases: An interplay among axonal transport failure, oxidative stress, and inflammation? Semin Immunol, 2022. 59: p. 101628. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweeney, P., et al., Protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases: implications and strategies. Transl Neurodegener, 2017. 6: p. 6. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, H., et al., The cerebellum in Alzheimer's disease: evaluating its role in cognitive decline. Brain : a journal of neurology, 2018. 141 1: p. 37-47. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Callaghan, C., et al., Cerebellar atrophy in Parkinson's disease and its implication for network connectivity. Brain, 2016. 139(Pt 3): p. 845-55. [CrossRef]

- Iskusnykh, I., et al., Aging, Neurodegenerative Disorders, and Cerebellum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2024. 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, K. and E. Carlson, Resistance, vulnerability and resilience: A review of the cognitive cerebellum in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 2020. 170.

- Kaur, G. and N. Singh, The Role of Inflammation in Retinal Neurodegeneration and Degenerative Diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021. 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, G., et al., Progressive neurodegeneration following spinal cord injury. Neurology, 2018. 90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, A., et al., Spinal Cord Injury: Pathophysiology, Multimolecular Interactions, and Underlying Recovery Mechanisms. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020. 21. [CrossRef]

- Akbar, A., et al., CRISPR in Neurodegenerative Diseases Treatment: An Alternative Approach to Current Therapies. Genes (Basel), 2025. 16(8). [CrossRef]

- Jankovic, J. and L.G. Aguilar, Current approaches to the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 2008. 4(4): p. 743-57. [CrossRef]

- Temple, S., Advancing cell therapy for neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Stem Cell, 2023. 30(5): p. 512-529. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi Darehbagh, R., et al., Stem cell therapies for neurological disorders: current progress, challenges, and future perspectives. Eur J Med Res, 2024. 29(1): p. 386. [CrossRef]

- Sakthiswary, R. and A.A. Raymond, Stem cell therapy in neurodegenerative diseases: From principles to practice. Neural Regen Res, 2012. 7(23): p. 1822-31.

- Li, Y., et al., Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in neurodegenerative diseases. World Journal of Stem Cells, 2025.

- Patel, G.D., et al., Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapies for treating well-studied neurological disorders: a systematic review. Front Med (Lausanne), 2024. 11: p. 1361723. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagno, L.L., et al., Mechanism of Action of Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs): impact of delivery method. Expert Opin Biol Ther, 2022. 22(4): p. 449-463. [CrossRef]

- Issa, E.H.B., et al., Therapeutic potential and challenges of mesenchymal stem cells in neurological disorders: A concise analysis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol, 2025. 84(8): p. 668-679. [CrossRef]

- Quan, J., et al., Mesenchymal stem cell exosome therapy: current research status in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases and the possibility of reversing normal brain aging. Stem Cell Research and Therapy, 2025. 16(1). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krämer-Albers, E.-M., Extracellular Vesicles at CNS barriers: Mode of action. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 2022. 75. [CrossRef]

- Banks, W., et al., Transport of Extracellular Vesicles across the Blood-Brain Barrier: Brain Pharmacokinetics and Effects of Inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020. 21. [CrossRef]

- Nieland, L., et al., Engineered EVs designed to target diseases of the CNS. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society, 2023. 356: p. 493-506. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.S., et al., Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Huntington Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Stem Cells Int, 2023. 2023: p. 1109967. [CrossRef]

- Aditya, B., B. Harshita, and S. Priyanka, Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: A novel therapeutic approach for neurodegenerative diseases. Neuroscience, 2024. 555: p. 52-68. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.R., et al., Role of Cholinergic Signaling in Alzheimer's Disease. Molecules, 2022. 27(6). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pushpa Tryphena, K., et al., Pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics for Alzheimer's disease: Breaking the memory barrier. Ageing Research Reviews, 2024. 101: p. 102481. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.P. and H. LeVine, 3rd, Alzheimer's disease and the amyloid-beta peptide. J Alzheimers Dis, 2010. 19(1): p. 311-23. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., et al., Role of Aβ in Alzheimer's-related synaptic dysfunction. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022. 10: p. 964075. [CrossRef]

- McGroarty, J., et al., Inflammasome-Mediated Neuroinflammation: A Key Driver in Alzheimer's Disease Pathogenesis. Biomolecules, 2025. 15(5). [CrossRef]

- Tolar, M., et al., Neurotoxic Soluble Amyloid Oligomers Drive Alzheimer’s Pathogenesis and Represent a Clinically Validated Target for Slowing Disease Progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021. 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S. and D. Selkoe, A mechanistic hypothesis for the impairment of synaptic plasticity by soluble Aβ oligomers from Alzheimer’s brain. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2020. 154: p. 583-597. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., et al., Role of Aβ in Alzheimer’s-related synaptic dysfunction. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2022. 10. [CrossRef]

- Fišar, Z., Linking the Amyloid, Tau, and Mitochondrial Hypotheses of Alzheimer’s Disease and Identifying Promising Drug Targets. Biomolecules, 2022. 12. [CrossRef]

- Fanlo-Ucar, H., et al., The Dual Role of Amyloid Beta-Peptide in Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: Unveiling Their Connections in Alzheimer’s Disease Etiopathology. Antioxidants, 2024. 13. [CrossRef]

- Gulisano, W., et al., Role of Amyloid-β and Tau Proteins in Alzheimer's Disease: Confuting the Amyloid Cascade. J Alzheimers Dis, 2018. 64(s1): p. S611-s631. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z., D. Zhi-fang, and Z. Jie-yuan, Immunomodulatory role of mesenchymal stem cells in Alzheimer's disease. Life Sciences, 2020. 246: p. 117405. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., et al., Exploration of Cytokines That Impact the Therapeutic Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Alzheimer’s Disease. Bioengineering, 2025. 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X., et al., Clinical safety and efficacy of allogenic human adipose mesenchymal stromal cells-derived exosomes in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a phase I/II clinical trial. General Psychiatry, 2023. 36. [CrossRef]

- Cone, A., et al., Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles ameliorate Alzheimer's disease-like phenotypes in a preclinical mouse model. Theranostics, 2021. 11: p. 8129-8142. [CrossRef]

- Qin, C., et al., Transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells improves cognitive deficits and alleviates neuropathology in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analytic review on potential mechanisms. Translational Neurodegeneration, 2020. 9. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J., et al., Intracerebroventricular injection of human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells in patients with Alzheimer’s disease dementia: a phase I clinical trial. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy, 2021. 13.

- Rash, B., et al., Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell therapy with laromestrocel in mild Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized controlled phase 2a trial. Nature Medicine, 2025. 31: p. 1257-1266. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouli, A., K.M. Torsney, and W.L. Kuan, Parkinson’s Disease: Etiology, Neuropathology, and Pathogenesis, in Parkinson’s Disease: Pathogenesis and Clinical Aspects, T.B. Stoker and J.C. Greenland, Editors. 2018, Codon Publications Copyright: The Authors.: Brisbane (AU).

- Xu, L. and J. Pu, Alpha-Synuclein in Parkinson's Disease: From Pathogenetic Dysfunction to Potential Clinical Application. Parkinson's Disease, 2016. 2016.

- Wang, X., et al., Effectiveness of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles therapy for Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review of preclinical studies. World Journal of Stem Cells, 2025. 17. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volarević, A., et al., Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. Cells, 2025. 14. [CrossRef]

- Mendes-Pinheiro, B., et al., Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells' Secretome Exerts Neuroprotective Effects in a Parkinson's Disease Rat Model. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2019. 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, C.R., et al., Secretome of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells cultured in a dynamic system induces neuroprotection and modulates microglial responsiveness in an α-synuclein overexpression rat model. Cytotherapy, 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiess, M., et al., Preliminary Report on the Safety and Tolerability of Bone marrow-derived Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stem Cells infused intravenously in Parkinson’s disease Patients (S16.008). Neurology, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rahbaran, M., et al., Therapeutic utility of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-based approaches in chronic neurodegeneration: a glimpse into underlying mechanisms, current status, and prospects. Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters, 2022. 27.

- Venkataramana, N., et al., Open-labeled study of unilateral autologous bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in Parkinson's disease. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine, 2010. 155 2: p. 62-70. [CrossRef]

- Boika, A., et al., Mesenchymal stem cells in Parkinson’s disease: Motor and nonmotor symptoms in the early posttransplant period. Surgical Neurology International, 2020. 11.

- Neelam, K.V., et al., Open-labeled study of unilateral autologous bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in Parkinson's disease. Translational Research, 2010. 155(2): p. 62-70.

- Venkataramana, N., et al., Bilateral Transplantation of Allogenic Adult Human Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells into the Subventricular Zone of Parkinson's Disease: A Pilot Clinical Study. Stem Cells International, 2012. 2012.

- Patel, G.D., et al., Mesenchymal stem cell-based therapies for treating well-studied neurological disorders: a systematic review. Frontiers in Medicine, 2024. 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiess, M., et al., Allogeneic Bone Marrow–Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Safety in Idiopathic Parkinson's Disease. Movement Disorders, 2021. 36: p. 1825-1834. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vij, R., et al., Safety and efficacy of adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy in elderly Parkinson's disease patients: an intermediate-size expanded access program. Cytotherapy, 2024. [CrossRef]

- McColgan, P. and S.J. Tabrizi, Huntington's disease: a clinical review. Eur J Neurol, 2018. 25(1): p. 24-34. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A., et al., From Pathogenesis to Therapeutics: A Review of 150 Years of Huntington’s Disease Research. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023. 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurcău, A., Molecular Pathophysiological Mechanisms in Huntington’s Disease. Biomedicines, 2022. 10. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.W., et al., Current and Possible Future Therapeutic Options for Huntington's Disease. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis, 2022. 14: p. 11795735221092517. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.-S., et al., Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Huntington Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Stem Cells International, 2023. 2023.

- Kerkis, I., et al., Neural and mesenchymal stem cells in animal models of Huntington’s disease: past experiences and future challenges. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2015. 6.

- Rossignol, J., et al., Reductions in behavioral deficits and neuropathology in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease following transplantation of bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells is dependent on passage number. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2015. 6. [CrossRef]

- Rossignol, J., et al., Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation and DMEM administration in a 3NP rat model of Huntington's disease: Morphological and behavioral outcomes. Behavioural Brain Research, 2011. 217: p. 369-378. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo Furno, D., G. Mannino, and R. Giuffrida, Functional role of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of chronic neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 2018. 233: p. 3982-3999. [CrossRef]

- Kari, P., et al., Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Genetically Engineered to Overexpress Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor Improve Outcomes in Huntington's Disease Mouse Models. Molecular Therapy, 2016. 24(5): p. 965-977. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu-Taeger, L., et al., Intranasal Administration of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Ameliorates the Abnormal Dopamine Transmission System and Inflammatory Reaction in the R6/2 Mouse Model of Huntington Disease. Cells, 2019. 8. [CrossRef]

- Wheelock, V., et al., PRE-CELL: Clinical and Novel Biomarker Measures of Disease Progression in a Lead-In-Observational Study for a Planned Phase 1 Trial of Genetically-Modified Mesenchymal Stem Cells Over-Expressing BDNF in Patients with Huntington’s Disease (S25.004). Neurology, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Fink, K., et al., Developing stem cell therapies for juvenile and adult-onset Huntington’s disease. Regenerative medicine, 2015. 10: p. 623-646. [CrossRef]

- Giovannelli, L., et al., Mesenchymal stem cell secretome and extracellular vesicles for neurodegenerative diseases: Risk-benefit profile and next steps for the market access. Bioactive Materials, 2023. 29: p. 16-35. [CrossRef]

- Masrori, P. and P. Van Damme, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a clinical review. Eur J Neurol, 2020. 27(10): p. 1918-1929. [CrossRef]

- Peggion, C., et al., SOD1 in ALS: Taking Stock in Pathogenic Mechanisms and the Role of Glial and Muscle Cells. Antioxidants, 2022. 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, L., et al., Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms Affected in ALS. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 2020. 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A., Clinical Manifestation and Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, T. Araki, Editor. 2021, Exon Publications Copyright: The Authors.: Brisbane (AU).

- Pasqualucci, E., et al., Management of Dysarthria in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cells, 2025. 14(14). [CrossRef]

- Achi, E.Y. and S.A. Rudnicki, ALS and Frontotemporal Dysfunction: A Review. Neurol Res Int, 2012. 2012: p. 806306. [CrossRef]

- Vercelli, A., et al., Human mesenchymal stem cell transplantation extends survival, improves motor performance and decreases neuroinflammation in mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiology of Disease, 2008. 31: p. 395-405. [CrossRef]

- Rahbaran, M., et al., Therapeutic utility of mesenchymal stromal cell (MSC)-based approaches in chronic neurodegeneration: a glimpse into underlying mechanisms, current status, and prospects. Cell Mol Biol Lett, 2022. 27(1): p. 56. [CrossRef]

- Tolstova, T., et al., Preconditioning of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhances the Neuroprotective Effects of Their Conditioned Medium in an Alzheimer’s Disease In Vitro Model. Biomedicines, 2024. 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrou, P., et al., Safety and Clinical Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Secreting Neurotrophic Factor Transplantation in Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Results of Phase 1/2 and 2a Clinical Trials. JAMA neurology, 2016. 73 3: p. 337-344. [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.-W., et al., Phase I Trial of Repeated Intrathecal Autologous Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. STEM CELLS Translational Medicine, 2015. 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cudkowicz, M., et al., A randomized placebo-controlled phase 3 study of mesenchymal stem cells induced to secrete high levels of neurotrophic factors in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle & Nerve, 2021. 65: p. 291-302.

- Di Santo, S. and H.R. Widmer, Paracrine factors for neurodegenerative disorders: special emphasis on Parkinson's disease. Neural Regen Res, 2016. 11(4): p. 570-1.

- Ghasemi, M., et al., Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived secretome-based therapy for neurodegenerative diseases: overview of clinical trials. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2023. 14.

- Sheikhi, K., et al., Recent advances in mesenchymal stem cell therapy for multiple sclerosis: clinical applications and challenges. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2025. 13. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M., D.D. Liu, and A.S. Thakor, Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Homing: Mechanisms and Strategies for Improvement. iScience, 2019. 15: p. 421-438. [CrossRef]

- Isaković, J., et al., Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for neurological disorders: The light or the dark side of the force? Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2023. 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turlo, A.J., et al., Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Secretome Is Affected by Tissue Source and Donor Age. Stem Cells, 2023. 41(11): p. 1047-1059. [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bos, J., et al., Are Cell-Based Therapies Safe and Effective in the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Biomolecules, 2022. 12. [CrossRef]

- Staff, N.P., D.T. Jones, and W. Singer, Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapies for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mayo Clin Proc, 2019. 94(5): p. 892-905. [CrossRef]

- Quynh Dieu, T., M. Huynh Nhu, and P. Duc Toan, Application of mesenchymal stem cells for neurodegenerative diseases therapy discovery. Regenerative Therapy, 2024. 26: p. 981-989. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).