Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

15 January 2026

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

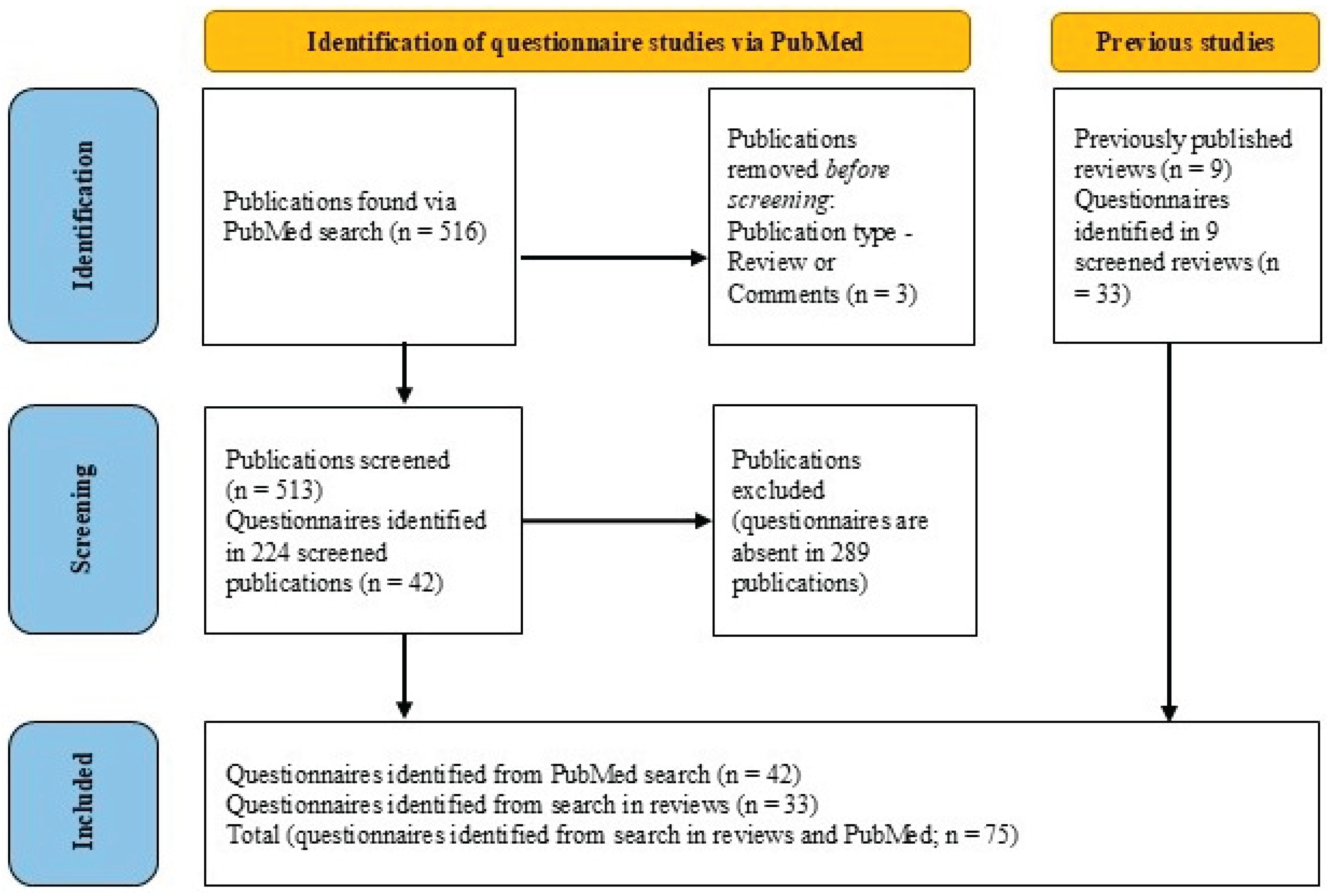

2.1. Identification of Chronotype Questionnaires

2.2. List of Properties for Classification of Chronotype Questionnaires

2.3. Categorization of 11 Properties of Chronotype Questionnaires

2.4. Categorization of 9 Properties of Scales of Chronotype Questionnaires

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ME | Morningness-eveningness construct |

| M,E | Morningness subconstruct, Eveningness subconstruct of morningness-eveningness construct |

| M | Morningness subconstruct of morningness-eveningness construct |

| See also Table 1 for questionnaire abbreviations |

References

- Sir William Thomson (Lord Kelvin). Popular Lectures and Addresses, Vol. 1, page 73.

- Di Milia L, Adan A, Natale V, Randler C. Reviewing the psychometric properties of contemporary circadian typology measures. Chronobiol Int. 2013;30(10):1261-71. [CrossRef]

- Putilov AA. Owls, larks, swifts, woodcocks and they are not alone: A historical review of methodology for multidimensional self-assessment of individual differences in sleep-wake pattern. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(3):426-437. [CrossRef]

- Horne JA, Östberg O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol. 1976;4(2):97-110. PMID: 1027738.

- Torsvall L, Åkerstedt T. A diurnal type scale. Construction, consistency and validation in shift work. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1980;6(4):283-90. PMID: 7195066. [CrossRef]

- Moog, R. (1981). Morning-evening types and shift work: a questionnaire study. In Reinberg, A., Vieux, N. & Andlauer, P. (Eds), Night and shift work: biological and social aspects. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Smith CS, Reilly C, Midkiff K. Evaluation of three circadian rhythm questionnaires with suggestions for an improved measure of morningness. J Appl Psychol. 1989;74(5):728-38. [CrossRef]

- Folkard S, Monk TH, Lobban MC. Towards a predictive test of adjustment to shift work. Ergonomics. 1979;22(1):79-91. [CrossRef]

- Ogińska H. 2011. Can you feel the rhythm? A short questionnaire to describe two dimensions of chronotype. Pers Individ Dif. 50(7):1039–43. [CrossRef]

- Putilov, A.A. A questionnaire for self-assessment of individual traits of sleep-wake cycle. Bulletin of the Siberian Branch of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences, 1990, 1: 22-25 [in Russian].

- Randler C, Díaz-Morales JF, Rahafar A, Vollmer C. Morningness-eveningness and amplitude - development and validation of an improved composite scale to measure circadian preference and stability (MESSi). Chronobiol Int. 2016;33(7):832-48. [CrossRef]

- Putilov AA. Three-dimensional structural representation of the sleep-wake adaptability. Chronobiol Int. 2016;33(2):169-80. [CrossRef]

- Samuels C, James L, Lawson D, Meeuwisse W. The Athlete Sleep Screening Questionnaire: a new tool for assessing and managing sleep in elite athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(7):418-22. [CrossRef]

- de Souza CM, Carissimi A, Costa D, Francisco AP, Medeiros MS, Ilgenfritz CA, de Oliveira MA, Frey BN, Hidalgo MP. The Mood Rhythm Instrument: development and preliminary report. Braz J Psychiatry. 2016;38(2):148-53. [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki R, Ando H, Hamasaki T, Higuchi Y, Oshita K, Tashiro T, Sakane N. Development and initial validation of the Morningness-Eveningness Exercise Preference Questionnaire (MEEPQ) in Japanese university students. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0200870. [CrossRef]

- Francis, L. J., Village, A., & Payne, V. J. Introducing the Francis Owl-Lark Indices (FOLI): Assessing the implications of diurnal activity patterns for clergy work-related psychological health. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 2021, 24(8), 780–795. [CrossRef]

- Putilov AA, Sveshnikov DS, Puchkova AN, Dorokhov VB, Bakaeva ZB, Yakunina EB, Starshinov YP, Torshin VI, Alipov NN, Sergeeva OV, Trutneva EA, Lapkin MM, Lopatskaya ZN, Budkevich RO, Budkevich EV, Dyakovich MP, Donskaya OG, Plusnin JM, Delwiche B, Colomb C, Neu D, & Mairesse O. Single-Item Chronotyping (SIC), a method to self-assess diurnal types by using 6 simple charts. Pers Ind Differ. 2021, 168:Article 110353. [CrossRef]

- Byrne JEM, Bullock B, Murray G. Development of a Measure of Sleep, Circadian Rhythms, and Mood: The SCRAM Questionnaire. Front Psychol. 2017;8:2105. [CrossRef]

- Veronda AC, Allison KC, Crosby RD, Irish LA. Development, validation and reliability of the Chrononutrition Profile - Questionnaire. Chronobiol Int. 2020;37(3):375-394. [CrossRef]

- Chakradeo P, Rasmussen HE, Swanson GR, Swanson B, Fogg LF, Bishehsari F, Burgess HJ, Keshavarzian A. Psychometric Testing of a Food Timing Questionnaire and Food Timing Screener. Curr Dev Nutr. 2021;6(2):nzab148. [CrossRef]

- Phoi YY, Bonham MP, Rogers M, Dorrian J, Coates AM. Content Validation of a Chrononutrition Questionnaire for the General and Shift Work Populations: A Delphi Study. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):4087. [CrossRef]

- Murakami K, Shinozaki N, McCaffrey TA, Livingstone MBE, Masayasu S, Sasaki S. Relative validity of the Chrono-Nutrition Behavior Questionnaire (CNBQ) against 11-day event-based ecological momentary assessment diaries of eating. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2025;22(1):46. [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg T. Having Trouble Typing? What on Earth Is Chronotype? J Biol Rhythms. 2015;30(6):487-91. [CrossRef]

- Roenneberg T, Wirz-Justice A, Merrow M. Life between clocks: daily temporal patterns of human chronotypes. J Biol Rhythms. 2003;18(1):80-90. [CrossRef]

- Adan, A., & Almirall, H. Horne and Őstberg Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire: A reduced scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 1991, 12(3), 241–253. [CrossRef]

- Carskadon MA, Vieira C, Acebo C. Association between puberty and delayed phase preference. Sleep. 1993;16(3):258-62. [CrossRef]

- Werner H, Lebourgeois MK, Geiger A, Jenni OG. Assessment of chronotype in four- to eleven-year-old children: reliability and validity of the Children’s Chronotype Questionnaire (CCTQ). Chronobiol Int. 2009;26(5):992-1014. [CrossRef]

- Cavallera GM, Giudici S. Morningness and eveningness personality: a survey in literature from 1995 up till 2006. Pers Individ Dif 2008;44:3–21. [CrossRef]

- Levandovski R, Sasso E, Hidalgo MP. Chronotype: a review of the advances, limits and applicability of the main instruments used in the literature to assess human phenotype. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2013;35(1):3-11. [CrossRef]

- Tonetti L, Adan A, Di Milia L, Randler C, Natale V. Measures of circadian preference in childhood and adolescence: A review. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(5):576-82. [CrossRef]

- Almoosawi S, Vingeliene S, Gachon F, Voortman T, Palla L, Johnston JD, Van Dam RM, Darimont C, Karagounis LG. Chronotype: Implications for Epidemiologic Studies on Chrono-Nutrition and Cardiometabolic Health. Adv Nutr. 2019;10(1):30-42. [CrossRef]

- Coelho J, Martin VP, Gauld C, d’Incau E, Geoffroy PA, Bourgin P, Philip P, Taillard J, Micoulaud-Franchi JA. Clinical physiology of circadian rhythms: A systematic and hierarchized content analysis of circadian questionnaires. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2025;25(2):100563. [CrossRef]

- Vidueira VF, Booth JN, Saunders DH, Sproule J, Turner AP. Circadian preference and physical and cognitive performance in adolescence: A scoping review. Chronobiol Int. 2023;40(9):1296-1331. [CrossRef]

- Buest de Mesquita Silva, R., Schmidt, H., dos Santos, G., Leocadio-Miguel, M., & Mazzilli Louzada, F. Chronotype Profile in Children: A Systematic Review. Sleep and Vigilance OnlineFirst (2025): 1-28. [CrossRef]

- Caci H, Adan A, Bohle P, Natale V, Pornpitakpan C, Tilley A. Transcultural properties of the composite scale of morningness: the relevance of the “morning affect” factor. Chronobiol Int. 2005;22(3):523-40. [CrossRef]

- Smith CS, Folkard S, Schmieder RA, Parra LF, Spelten E, Almiral H, Tisak J, Sahu S, Perez LM, Tisak J. Investigation of morning–evening orientation in six countries using the preferences scale. Pers Individ Dif. 2002, 32:949–968. [CrossRef]

- Monk TH, Buysse DJ, Kennedy KS, Pods JM, DeGrazia JM, Miewald JM. Measuring sleep habits without using a diary: the sleep timing questionnaire. Sleep. 2003;26(2):208-12. [CrossRef]

- Groß JV, Fritschi L, Erren TC. Hypothesis: A perfect day conveys internal time. Med Hypotheses. 2017;101:85-89. [CrossRef]

- Putilov, A.A., Putilov, D.A. Sleepless in Siberia and Alaska: Cross-validation of factor structure of the individual adaptability of the sleep-wake cycle. Ergonomia, 2005, 27(2): 207-226.

- Di Milia L, Smith PA, Folkard S. A validation of the revised circadian type inventory in a working sample. Pers Indiv Differ. 2005, 39:1293–1305. [CrossRef]

- Di Milia L, Folkard S, Hill J, Walker C Jr. A psychometric assessment of the Circadian Amplitude and Phase Scale. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28(1):81-7. [CrossRef]

- Oginska H, Mojsa-Kaja J, Mairesse O. Chronotype description: In search of a solid subjective amplitude scale. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(10):1388-1400. [CrossRef]

- Dosseville F, Laborde S, Lericollais R. Validation of a chronotype questionnaire including an amplitude dimension. Chronobiol Int. 2013;30(5):639-48. [CrossRef]

- Ottoni GL, Antoniolli E, Lara DR. The Circadian Energy Scale (CIRENS): two simple questions for a reliable chronotype measurement based on energy. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28(3):229-37. [CrossRef]

- Monk TH, Flaherty JF, Frank E, Hoskinson K, Kupfer DJ. The Social Rhythm Metric. An instrument to quantify the daily rhythms of life. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990;178(2):120-6. [CrossRef]

- Marcoen N, Vandekerckhove M, Neu D, Pattyn N, Mairesse O. Individual differences in subjective circadian flexibility. Chronobiol Int. 2015;32(9):1246-53. [CrossRef]

- Putilov, A.A. Introduction of the tetra-circumplex criterion for comparison of the actual and theoretical structures of the sleep-wake adaptability. Biol Rhythm Res 2007, 38: 65-84. [CrossRef]

- Putilov AA, Budkevich EV, Tinkova EL, Dyakovich MP, Sveshnikov DS, Donskaya OG, Budkevich RO. A six-factor structure of individual variation in the tendencies to become sleepy and to sleep at different times of the day. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2021;217:103327. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, R. D. The Lark-Owl (Chronotype) Indicator (LOCI). Sydney: Entelligent Testing Products, 1998; www.radssolution.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/1-Tech-Bulletin-Lark-Owl-Chronotype-Indicator.pdf.

- Rhee MK, Lee HJ, Rex KM, Kripke DF. Evaluation of two circadian rhythm questionnaires for screening for the delayed sleep phase disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2012;9(3):236-44. [CrossRef]

- Juda M, Vetter C, Roenneberg T. The Munich ChronoType Questionnaire for Shift-Workers (MCTQShift). J Biol Rhythms. 2013;28(2):130-40. PMID: 23606612. [CrossRef]

- Pornpitakpan C. Psychometric properties of the composite scale of morningness: a shortened version. Pers Ind Diff. 1998, 25:699–709. [CrossRef]

- Brown FM. Psychometric equivalence of an improved Basic Language Morningness (BALM) scale using industrial population within comparisons. Ergonomics. 1993;36(1-3):191-7. [CrossRef]

- Weidenauer, C., Täuber, L., Huber, S., Rimkus, K., & Randler, C. Measuring circadian preference in adolescence with the Morningness-Eveningness Stability Scale improved (MESSi). Biological Rhythm Research, 2019, 52(3), 367–379. [CrossRef]

- Putilov, A.A. Association of the circadian phase with two morningness-eveningness scales of an enlarged version of the sleep-wake pattern assessment questionnaire. Arbeitswissbetriebl Praxis 2000, 17: 317-322.

- Ghotbi N, Pilz LK, Winnebeck EC, Vetter C, Zerbini G, Lenssen D, Frighetto G, Salamanca M, Costa R, Montagnese S, Roenneberg T. The µMCTQ: An Ultra-Short Version of the Munich ChronoType Questionnaire. J Biol Rhythms. 2020;35(1):98-110. [CrossRef]

- Manjón-Caballero JL, Díaz-Morales JF. Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire: Reliability and factorial structure of the full and reduced versions in Spanish adolescents. Chronobiol Int. 2025;42(6):808-816. [CrossRef]

- Urbán R, Magyaródi T, Rigó A. Morningness-eveningness, chronotypes and health-impairing behaviors in adolescents. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28(3):238-47. [CrossRef]

- Jankowski KS. Polish version of the reduced morningness–eveningness questionnaire. Biol Rhythm Res, 2013, 44:427–433. doi:10.1080/09291016.2012.704791.

- Turco M, Corrias M, Chiaromanni F, Bano M, Salamanca M, Caccin L, Merkel C, Amodio P, Romualdi C, De Pittà C, Costa R, Montagnese S. The self-morningness/eveningness (Self-ME): An extremely concise and totally subjective assessment of diurnal preference. Chronobiol Int. 2015;32(9):1192-200. [CrossRef]

- Košćec, A., Radošević-Vidaček, B. & Kostović, M. Morningness–eveningness across two student generations: would two decades make a difference? Pers. Individ. Dif. 2001, 31(4), 627–638. [CrossRef]

- Hätönen T, Forsblom S, Kieseppä T, Lönnqvist J, Partonen T. Circadian phenotype in patients with the co-morbid alcohol use and bipolar disorders. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008:564-8. [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Lee HJ. Validation of the 6-item Evening Chronotype Scale (ECS): a modified version of Composite Scale Morningness. Chronobiol Int. 2021;38(11):1640-1649. [CrossRef]

- Barton J, Spelten E, Totterdell P, Smith L, Folkard S, Costa G. The standard shiftwork index—a battery of questionnaires for assessing shiftwork-related problems. Work Stress. 1995;9:4–30. [CrossRef]

- Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27(7):1255-73. [CrossRef]

- Evans MA, Buysse DJ, Marsland AL, Wright AGC, Foust J, Carroll LW, Kohli N, Mehra R, Jasper A, Srinivasan S, Hall MH. Meta-analysis of age and actigraphy-assessed sleep characteristics across the lifespan. Sleep. 2021;44(9):zsab088. [CrossRef]

- Skeldon AC, Derks G, Dijk DJ. Modelling changes in sleep timing and duration across the lifespan: Changes in circadian rhythmicity or sleep homeostasis? Sleep Med Rev. 2016;28:96-107. [CrossRef]

- Putilov AA, Verevkin EG. Weekday and weekend sleep times across the human lifespan: a model-based simulation. Sleep Breath. 2024;28(5):2223-2236. [CrossRef]

- Putilov AA, Verevkin EG. Simulation of the Ontogeny of Social Jet Lag: A Shift in Just One of the Parameters of a Model of Sleep-Wake Regulating Process Accounts for the Delay of Sleep Phase Across Adolescence. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1529. [CrossRef]

- Putilov, A. A., Verevkin, E. G., Donskaya, O. G., Tkachenko, O. N., & Dorokhov, V. B. Model-based simulations of weekday and weekend sleep times self-reported by larks and owls. Biol Rhythm Res, 2020;51(5), 709–726. [CrossRef]

- Putilov AA, Donskaya OG. What Can Make the Difference Between Chronotypes in Sleep Duration? Testing the Similarity of Their Homeostatic Processes. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:832807. [CrossRef]

- Putilov, A.A.; Verevkin, E.G.; Sveshnikov, D.S.; Bakaeva, Z.V.; Yakunina, E.B.; Mankaeva, O.V.; Torshin, V.I.; Trutneva, E.A.; Lapkin, M.M.; Lopatskaya, Z.N.; et al. Estimation of the Circadian Phase Difference in Weekend Sleep and Further Evidence for Our Failure to Sleep More on Weekends to Catch Up on Lost Sleep. Clocks & Sleep 2025, 7, 67. [CrossRef]

- Ishihara K, Miyake S, Miyasita A, Miyata Y. Comparisons of sleep-wake habits of morning and evening types in Japanese worker sample. J Hum Ergol (Tokyo). 1988;17(2):111-8.

- Steele MT, McNamara RM, Smith-Coggins R, Watson WA. Morningness-eveningness preferences of emergency medicine residents are skewed toward eveningness. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(7):699-705. [CrossRef]

- Harada T, Inoue M. Do majoring subjects affect the morningness-eveningness preference by students? J Hum Ergol (Tokyo). 1999;28(1-2):49-53.

- Adan A, Natale V. Gender differences in morningness-eveningness preference. Chronobiol Int. 2002;19(4):709-20. [CrossRef]

- Randler C, Engelke J. Gender differences in chronotype diminish with age: a meta-analysis based on morningness/chronotype questionnaires. Chronobiol Int. 2019;36(7):888-905. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann LK. Chronotype and the transition to college life. Chronobiol Int. 2011;28(10):904-10. [CrossRef]

- Natale V, Adan A, Fabbri M. Season of birth, gender, and social-cultural effects on sleep timing preferences in humans. Sleep. 2009;32(3):423-6. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Morales JF, Parra-Robledo Z. Age and Sex Differences in Morningness/Eveningness Along the Life Span: A Cross-Sectional Study in Spain. J Genet Psychol. 2018;179(2):71-84. [CrossRef]

- Buekenhout I, Clara MI, Gomes AA, Leitão J. Examining sex differences in morningness-eveningness and inter-individual variability across years of age: A cross-sectional study. Chronobiol Int. 2025;42(1):29-45. [CrossRef]

- Duarte LL, Menna-Barreto L, Miguel MA, Louzada F, Araújo J, Alam M, Areas R, Pedrazzoli M. Chronotype ontogeny related to gender. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2014;47(4):316-20. [CrossRef]

- Merikanto I, Kronholm E, Peltonen M, Laatikainen T, Lahti T, Partonen T. Relation of chronotype to sleep complaints in the general Finnish population. Chronobiol Int. 2012;29(3):311-7. [CrossRef]

- Gaina A, Sekine M, Kanayama H, Takashi Y, Hu L, Sengoku K, Kagamimori S. Morning-evening preference: sleep pattern spectrum and lifestyle habits among Japanese junior high school pupils. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(3):607-21. [CrossRef]

- Putilov AA, Verevkin EG, Ivanova E, Donskaya OG, Putilov DA. Gender differences in morning and evening lateness. Biol Rhythm Res 2008; 39(4), 335-348. doi:10.1080/09291010701424895.

- Preckel, F., Fischbach, A., Scherrer, V., Brunner, M., Ugen, S., Lipnevich, A. A., & Roberts, R. D. (2020). Circadian preference as a typology: Latent-class analysis of adolescents’ morningness/eveningness, relation with sleep behavior, and with academic outcomes. Learn. Individ. Differ., 78, 101725. [CrossRef]

- Putilov AA, Verevkin EG. The yin and yang of sleep-wake regulation: gender gap in need for sleep persists across the human lifespan. Sleep Breath. 2025;29(2):145. [CrossRef]

- Vagos P, Rodrigues PFS, Pandeirada JNS, Kasaeian A, Weidenauer C, Silva CF, Randler C. Factorial Structure of the Morningness-Eveningness-Stability-Scale (MESSi) and Sex and Age Invariance. Front Psychol. 2019;10:3. [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Morales JF, Randler C, Arrona-Palacios A, Adan A. Validation of the MESSi among adult workers and young students: General health and personality correlates. Chronobiol Int. 2017;34(9):1288-1299. [CrossRef]

- Tonetti L, Adan A, Natale V. A more accurate assessment of circadian typology is achieved by asking persons to indicate their preferred times rather than comparing themselves with most people. Chronobiol Int. 2024;41(1):53-60. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. [CrossRef]

| # | Family or | Subfamily | #.Abbreviation- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate | # of items | Number of items and name (abbreviation, yr, and author(s)) | ||

| 1 | 1.1.MEQ | 1.1.1.MEQ | 1.1.1.1.MEQ-19 | The 19-item Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (MEQ; 1976, Horne, Ostberg).[4] |

| 2 | 1.1.2.rMEQ | 1.1.2.1.rMEQ-1 | The 19th item of MEQ (MEQ19th; 1976, Horne, Ostberg) [4] | |

| 3 | 1.1.2.2.rMEQ-5 | The 5-item reduced MEQ (rMEQ; Adan, Almirall,1990)[25] | ||

| 4 | 1.2.DTS | 1.2.1.DTS | 1.2.1.1.DTS-7 | The 7-item Diurnal Type Scale (DTS; 1980, Torsvall & Åkerstedt)[5] |

| 5 | 1.3.CSM | 1.3.1.CSM | 1.3.1.1.CSM-13 | The 13-item Composite Scale of Morningness (CSM; 1989, Smith et al.)[7] |

| 6 | 1.3.4.MA | 1.3.4.1.MA-5 | The 5-item Morning Affect factor (MA factor, 2005, Caci et al.)[35] | |

| 7 | 1.3.5.PS | 1.3.5.1.PS-12 | The 12-item Early-Late Preferences Scale (PS; 2002, Smith et al.) [36] | |

| 8 | 1.4.STQ | 1.4.1.STQ | 1.4.1.1.STQ-18 | The 18-item Sleep Timing Questionnaire (STQ; 2003, Monk et al.) [37]. |

| 9 | 1.4.2.MCTQ | 1.4.2.1.MCTQ-32 | The 32-item Munich Chronotype Questionnaire (MCTQ; 2003, Roenneberg et al.)[24] | |

| 10 | 1.4.3.PD | 1.4.3.1.PD-2 | The two-item Perfect Day (PD; 2017, Gross et al.) [38]. | |

| 11 | 1.6.MRhl | 1.6.1.MRhI | 1.6.1.1.MRhI-15 | The 15-item Mood Rhythm Instrument (MRhI; 2016, de Souza et al.)[14] |

| 12 | 1.8.SACL | 1.8.1.SACL | 1.8.1.1.SACL-13 | The 13-item Scale for Assessment of Circadian Lateness (SACL; 2005, Putilov, Putilov) [39] |

| 13 | 1.9.FOLI | 1.9.1.FOLI | 1.9.1.1.FOLI-10 | The 10-item Francis Owl-Lark Indices (FOLI; 2021, Francis et al.)[16] |

| 14 | 2.1.CTQ | 2.1.1.CTQ | 2.1.1.1.CTQ-20 | The 20-item Circadian-Type Questionnaire (CTQ; 1979, Folkard et al.)[8] |

| 15 | 2.1.1.3.rCTI-11 | The 11-item Circadian Type Inventory-revised (CTI-r; 2005, Di Milia et al.) [40] | ||

| 16 | 2.1.2.CAPS | 2.1.2.1.CAPS-38 | The 38-item Circadian Amplitude and Phase Scale (CAPS; 2011, Di Milia et al.) [41] | |

| 17 | 2.2.ChQ | 2.2.1.ChQ | 2.2.1.1.ChQ-16 | The 16-item Chronotype Questionnaire (ChQ; 2011, Ogińska).[9] |

| 18 | 2.2.1.2.SCAS-8 | The 8-item Revised Subjective Amplitude Scale (SCAS; 2017, Oginska et al.) [42] | ||

| 19 | 2.2.2.CCQ | 2.2.2.1.CCQ-16 | The 16-item Caen Chronotype Questionnaire (CCQ; 2013, Dosseville et al.) [43] | |

| 20 | 2.3.CIRENS | 2.3.1.CIRENS | 2.3.1.1.CIRENS-3 | The three-item CIRcadian ENergy Scale (CIRENS; 2011, Ottoni et al.) [44] |

| 21 | 2.4.MESSi | 2.4.1.MESSi | 2.4.1.1.MESSi-15 | The 15-item Morningness–Eveningness-Stability Scale improved (MESSi; 2016, Randler et al.)[11] |

| 22 | 2.5.MQ | 2.5.1.MQ | 2.5.1.1.MQ-16 | The 16-item Marburger questionnaire (MQ; 1981, Moog)[6] |

| 23 | 2.5.2.SRM | 2.5.2.1.SRM-17 | The 17-item The Social Rhythm Metric (SRM; 1990, Monk et al.) [45] | |

| 24 | 2.6.VJT | 2.6.1.VJT | 2.6.1.1.VJT-19 | The 19-time point Visuo-verbal Judgment Task (VJT; 2015, Marcoen et al.) [46] |

| 25 | 2.6.2.SIC | 2.6.2.1.SIC-1 | The Single-Item Chronotyping (SIC; 2021, Putilov et al.).[17] | |

| 26 | 2.7.SWPAQ | 2.7.1.SWPAQ | 2.7.1.1.SWPAQ-40 | The 40-item Sleep-Wake Pattern Assessment Questionnaire (SWPAQ-40: 1990, Putilov) [10] |

| 27 | 2.7.1.2.SWPAQ-72 | The 72-item SWPAQ (SWPAQ-72: 2007, Putilov) [47] | ||

| 28 | 2.7.2.SWAT | 2.7.2.1.SWAT-168 | The 168-item Sleep-Wake Adaptability Test (SWAT-168; 2016, Putilov)[12] | |

| 29 | 2.7.2.2.rSWAT-60 | The 60-item SWAT (SWAT-60; 2021, Putilov) [48] | ||

| 30 | 2.8.LOCI | 2.8.1.LOCI | 2.8.1.1.LOCI-38 | The 38-item Lark-Owl (Chronotype) Indicator (LOCI; 1998, Roberts) [49] |

| # | #.Abbreviation- | 2a. | 2b. | 3a. | 3b. | 4a. | 4b. | 4c. | 5a. | 5b. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of items | Size | Items | Parameter | Scales | Variation | Output | Clock h | Behavior | Interval | |

| 1 | 1.1.1.1.MEQ-19 | Pr | 19 | Ph | 1 | TL | Sc | Ch+ | Act+Pre | T+W |

| 2 | 1.1.2.1.rMEQ-1 | Re | 1 | Ph | <1 | Ty | Sc | Ch- | Pre | W |

| 3 | 1.1.2.2.rMEQ-5 | Re | 5 | Ph | 1 | TL | Sc | Ch+ | Act+Pre | T+W |

| 4 | 1.2.1.1.DTS-7 | Pr | 7 | Ph | 1 | TL | Sc | Ch+ | Act+Pre | T+W |

| 5 | 1.3.1.1.CSM-13 | Pr | 13 | Ph | 1 | TL | Sc | Ch+ | Act+Pre | T+W |

| 6 | 1.3.4.1.MA-5 | Re | 5 | Ph | 1 | TL | Sc | Ch- | Act+Pre | T |

| 7 | 1.3.5.1.PS-12 | Fu | 12 | Ph | 1 | TL | Sc | Ch- | Pre | T+W |

| 8 | 1.4.1.1.STQ-18 | Pr | 18 | Ph | 2 | TL | Ch | Ch | Pre | T |

| 9 | 1.4.2.1.MCTQ-32 | Pr | 32 | Ph | <1 | SL | Ch | Ch | Act | T |

| 10 | 1.4.3.1.PD-2 | Re | 2 | Ph | <1 | TL | Ch | Ch | Pre | T |

| 11 | 1.6.1.1.MRhI-15 | Pr | 15 | Ph | 1 | SL | Ch | Ch | Act | W |

| 12 | 1.8.1.1.SACL-13 | Pr | 13 | Ph | 1 | TL | Sc | Ch | Pre | T+W |

| 13 | 1.9.1.1.FOLI-10 | Pr | 10 | Ph | 2 | TL | Scs | Ch+ | Pre | T+W |

| 14 | 2.1.1.1.CTQ-20 | Pr | 20 | Ph+ | 3 | T+AL | Scs | Ch- | Pre | T+W |

| 15 | 2.1.1.3.rCTI-11 | Re | 11 | Ph- | 2 | AL | Scs | Ch- | Pre | T+W |

| 16 | 2.1.2.1.CAPS-38 | En | 38 | Ph+ | 3 | T+AL | Scs | Ch- | Pre | T+W |

| 17 | 2.2.1.1.ChQ-16 | Pr | 16 | Ph+ | 2 | TL | Scs | Ch- | Pre | T+W |

| 18 | 2.2.1.2.SCAS-8 | Re | 8 | Ph- | 1 | TL | Sc | Ch- | Pre | T+W |

| 19 | 2.2.2.1.CCQ-16 | Fu | 16 | Ph+ | 2 | TL | Scs | Ch- | Pre | T+W |

| 20 | 2.3.1.1.CIRENS-3 | Pr | 3 | Ph+ | <1 | S+AL | Sc | Ch- | Act | W |

| 21 | 2.4.1.1.MESSi-15 | Fu | 15 | Ph+ | 3 | T+S+AL | Scs | Ch- | Act+Pre | T+W |

| 22 | 2.5.1.1.MQ-16 | Pr | 16 | Ph+ | 2 | T+SL | Scs | Ch+ | Act+Pre | T+W |

| 23 | 2.5.2.1.SRM-17 | Pr | 17 | Ph- | 1 | SL | Ch | Ch | Act | T+W |

| 24 | 2.6.1.1.VJT-19 | Pr | 19 | Ph+ | 4 | S+AL | Scs | Ch+ | Act | W |

| 25 | 2.6.2.1.SIC-1 | Pr | 1 | Ph+ | <1 | Ty | Na | Ch- | Act | W |

| 26 | 2.7.1.1.SWPAQ-40 | Pr | 40 | Ph+ | 5 | AL | Scs | Ch- | Pre | T+W+S |

| 27 | 2.7.1.2.SWPAQ-72 | En | 72 | Ph+ | 6 | AL | Scs | Ch- | Pre | T+W+S |

| 28 | 2.7.2.1.SWAT-168 | Pr | 168 | Ph+ | 6 | AL | Scs | Ch- | Pre | T+W+S |

| 29 | 2.7.2.2.rSWAT-60 | Re | 60 | Ph+ | 6 | AL | Scs | Ch- | Pre | T+W+S |

| 30 | 2.8.1.1.LOCI-38 | Pr | 38 | Ph+ | 3 | T+AL | Scs | Ch+ | Pre | T+W |

| # | #.Abbreviation- | 6a. | 6b. | 6c. | 7a. | 7b. | 8a. | 8b. | 9a. | 9b. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| number of items |

ME scale(s) |

Dimen- sions |

Items | Amplitude/ Stability |

Items | Wake- ability |

Items | Sleep- ability |

Items | |

| 1 | 1.1.1.1.MEQ-19 | ME | >1 | 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1.1.2.1.rMEQ-1 | ME | <1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1.1.2.2.rMEQ-5 | ME | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 1.2.1.1.DTS-7 | ME | >1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1.3.1.1.CSM-13 | ME | >1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 1.3.4.1.MA-5 | M | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 1.3.5.1.PS-12 | ME | >1 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 1.4.1.1.STQ-18 | M,E | <1 | 3,3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1.4.2.1.MCTQ-32 | ME | <1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 1.4.3.1.PD-2 | ME | <1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 1.6.1.1.MRhI-15 | ME | >1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 1.8.1.1.SACL-13 | ME | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 1.9.1.1.FOLI-10 | M,E | 1 | 5,5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 2.1.1.1.CTQ-20 | ME | 1 | 6 | 2 | 8,5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 2.1.1.3.rCTI-11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5,6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | 2.1.2.1.CAPS-38 | ME | >1 | 14 | 2 | 14,10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 17 | 2.2.1.1.ChQ-16 | ME | 1 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | 2.2.1.2.SCAS-8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | 2.2.2.1.CCQ-16 | ME | 1 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | 2.3.1.1.CIRENS-3 | ME | <1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | <1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 21 | 2.4.1.1.MESSi-15 | M,E | 1 | 5,5 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 22 | 2.5.1.1.MQ-16 | ME | 1 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 23 | 2.5.2.1.SRM-17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 24 | 2.6.1.1.VJT-19 | M,E | 1 | 4,6 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5,4 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | 2.6.2.1.SIC-1 | ME | <1 | <1 | 0 | 0 | <1 | <1 | 0 | 0 |

| 26 | 2.7.1.1.SWPAQ-40 | M,E | 1 | 12,8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4,12 |

| 27 | 2.7.1.2.SWPAQ-72 | M,E | 1 | 12,12 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 12,12 | 2 | 12,12 |

| 28 | 2.7.2.1.SWAT-168 | M,E | 1 | 28,28 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 28,28 | 2 | 28,28 |

| 29 | 2.7.2.2.rSWAT-60 | M,E | 1 | 10,10 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 10,10 | 2 | 10,10 |

| 30 | 2.8.1.1.LOCI-38 | M,E | 1 | 13,13 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Property of | Questionnaire | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Property # | 1a. | 1b. | 2a. | 3a. | 4a. | 4b. | 4.c |

| Its short name | For | in | Size | Parameter | Variation | Output | Clock h |

| Number | Ch+=15 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| of | Ch=60 | AN=39 | Pr=21 | Ph=38 | Ty=2 | Na=1 | Ch=11 |

| categories | AL=4 | Fu=9 | Ph+=15 | TL=35 | Sc=29 | Ch+=26 | |

| of | SW=2 | Re=27 | Ph-=6 | SL=10 | Scs=19 | Ch-=23 | |

| properties | AP=3 | En=3 | AL=6 | Ch=9 | |||

| AS=1 | S+AL=2 | Ch+Scs=1 | |||||

| CA=11 | T+AL=3 | ||||||

| T+S+AL=2 | |||||||

| T+SL=1 | |||||||

| Total number | 75 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Property of | Questionnaire | Questionnaire scale(s) | |||||

| Property # | 5a. | 5b. | 6a. | 6b. | 7a. | 8a. | 9a. |

| Its short name | Behavior | Interval |

ME scale(s) |

Dimensions |

Amplitude/ Stability |

Wake- ability |

Sleep- ability |

| Number | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| of | Act=12 | T=7 | ME=41 | 1=25 | 1=11 | 1=2 | 2=4 |

| categories | Pre=25 | W=7 | M=2 | >1=23 | 2=4 | 2=4 | 0=56 |

| of | Act+Pre=22 | T+W=41 | M,E=11 | <1=8 | 0=45 | <1=2 | |

| properties | T+W+S=4 | 0=6 | 0=4 | 0=52 | |||

| T+S=1 | |||||||

| Total number | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).