Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The Brown Planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål.) (Hemiptera: Delphinidae), is one of the most destructive pests of rice. Its reproductive and developmental traits are influenced by various environmental and biological factors including endosymbiotic microorganisms. Arsenophonus, a widespread endosymbiotic bacterium of insects, can affect host fitness and metabolic processes. This study investigates the role of Arsenophonus in modulating the developmental and reproductive traits of N. lugens fed on transgenic cry30Fa1 rice (KF30-14) and its parent variety Minghui 86 (MH86). Life table analysis revealed that Arsenophonus infection (Ars+) increased the development time and reduced the reproductive capacity of N. lugens, especially those feeding on KF30-14. The first-instar nymphs in MH86 Ars+ (infected) exhibited slower development compared to MH86 Ars- (uninfected). Similarly, the third and fourth-instar nymphs in KF30-14 Ars+ exhibited prolonged development time compared to KF30-14 Ars-. In addition, KF30-14 Ars+ females had significantly reduced reproductive capacity, smaller ovarian tubules and lower relative expression levels of reproduction-related genes including Trehalose transporter (Tret), Vitellogenin (Vg) and Cytochrome P450 hydroxylase (cyp314a1), while Juvenile hormone acid methyltransferase (JHAMT) expression was upregulated. RNA sequencing and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis revealed significant enrichment of genes involved in lipid, amino acid, and vitamin metabolisms, with Long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase implicated as a key regulator of lipid metabolism and reproductive fitness. These results highlight the complex interactions between endosymbionts, host plants and pest biology, offering a solid foundation for sustainable approaches to control N. lugens in rice production systems.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rice Varieties and Insects Rearing

2.2. Establishment of N. lugens Infected Populations and Bacterial Detection

2.3. Life Table Analysis

2.4. Effect of Ars on Adult Weight and the Size of the Reproductive Organs of N. lugens Feeding on Different Rice Varieties

2.5. Gene Expression and Transcriptomic Analysis

2.5.1. RNA Extraction

2.5.2. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

2.5.3. Transcriptome Data Processing and Quality Control

2.5.4. Differential Gene Expression and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

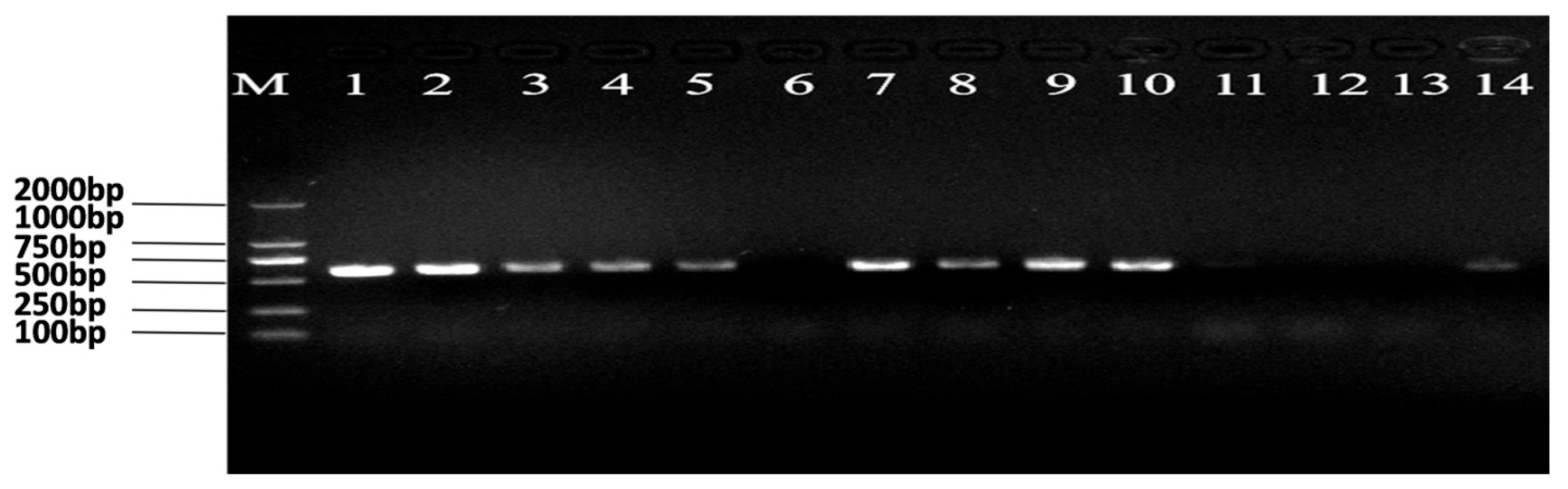

3.1. Establishment and Confirmation of Ars-Infected Populations

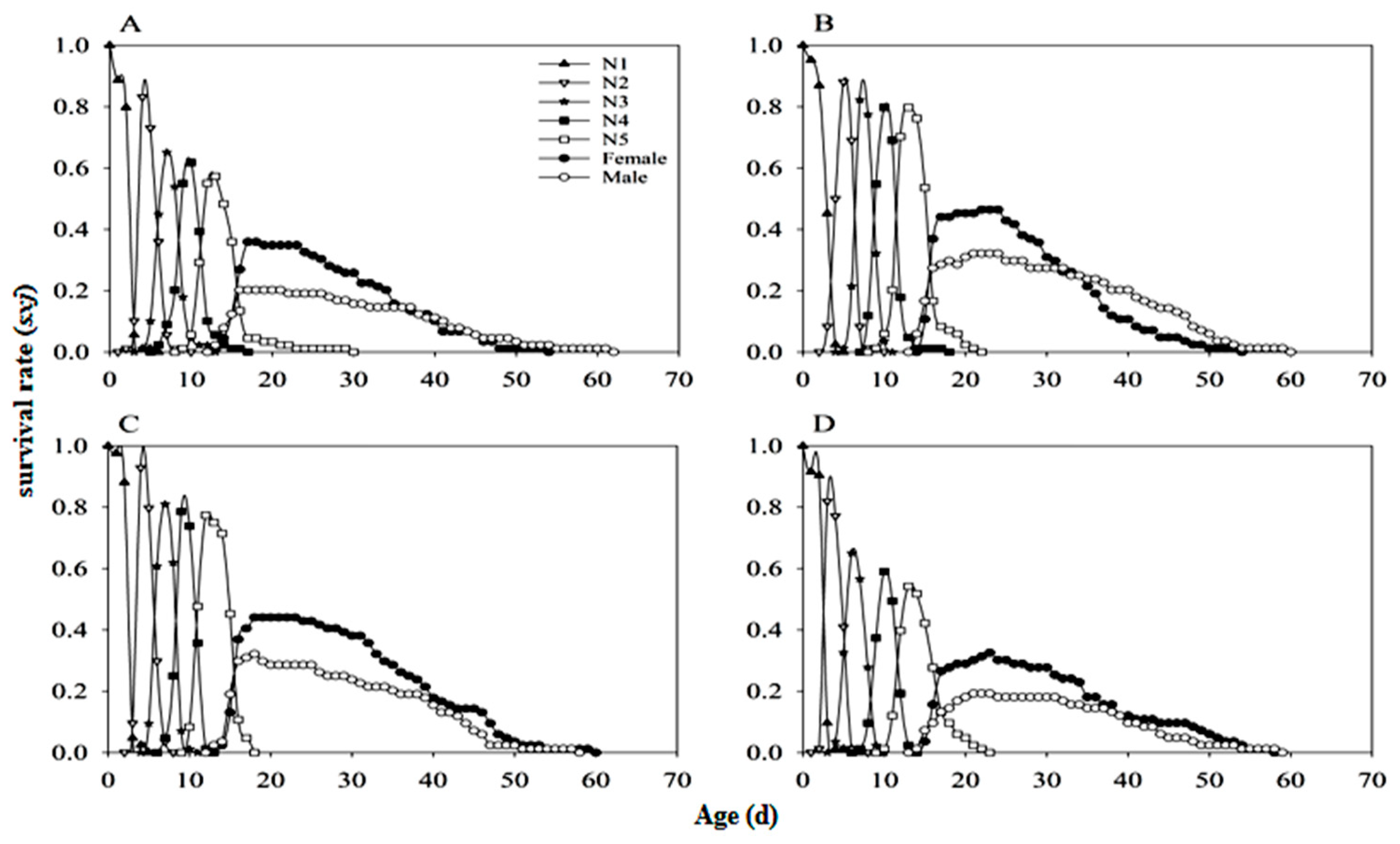

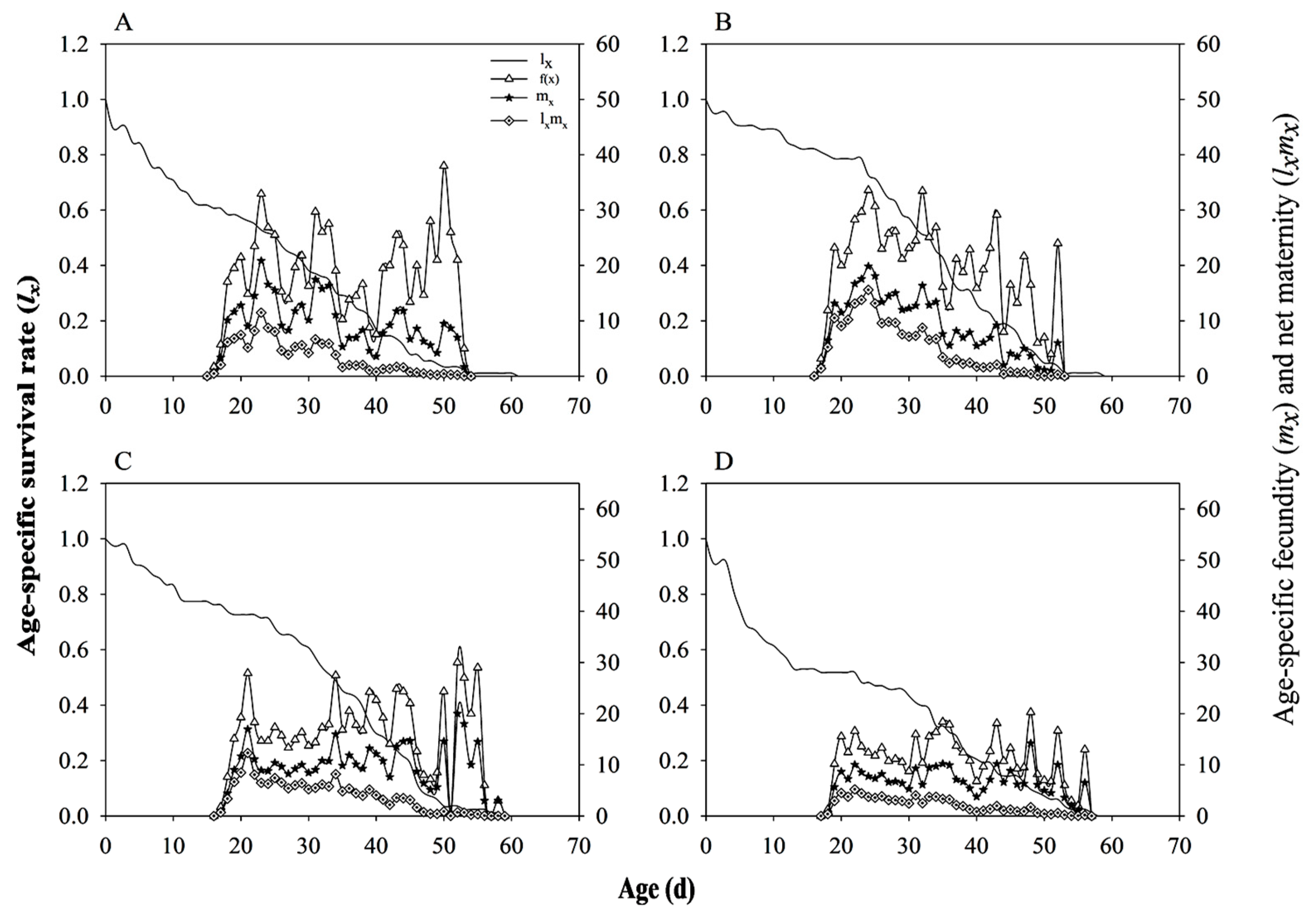

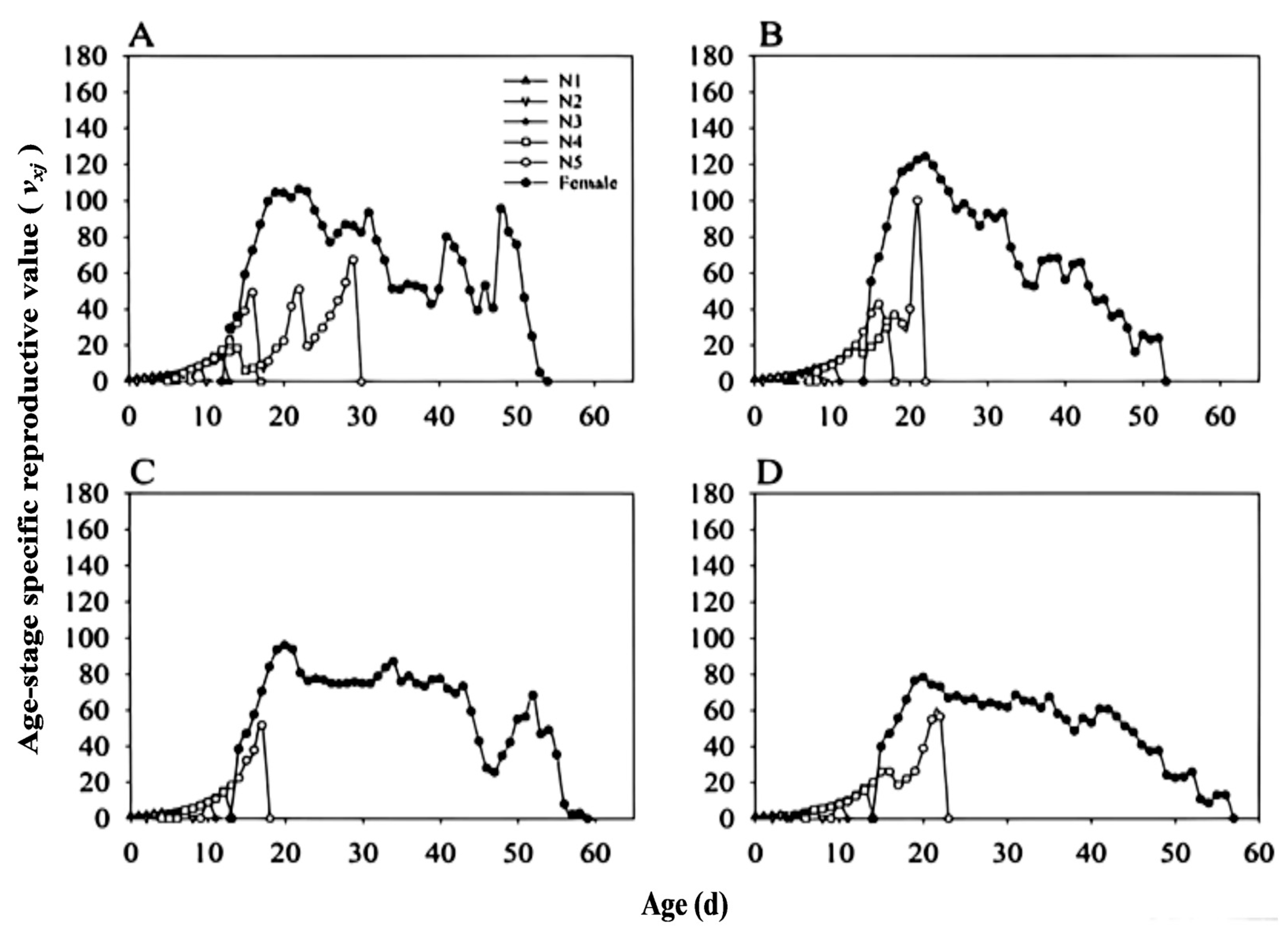

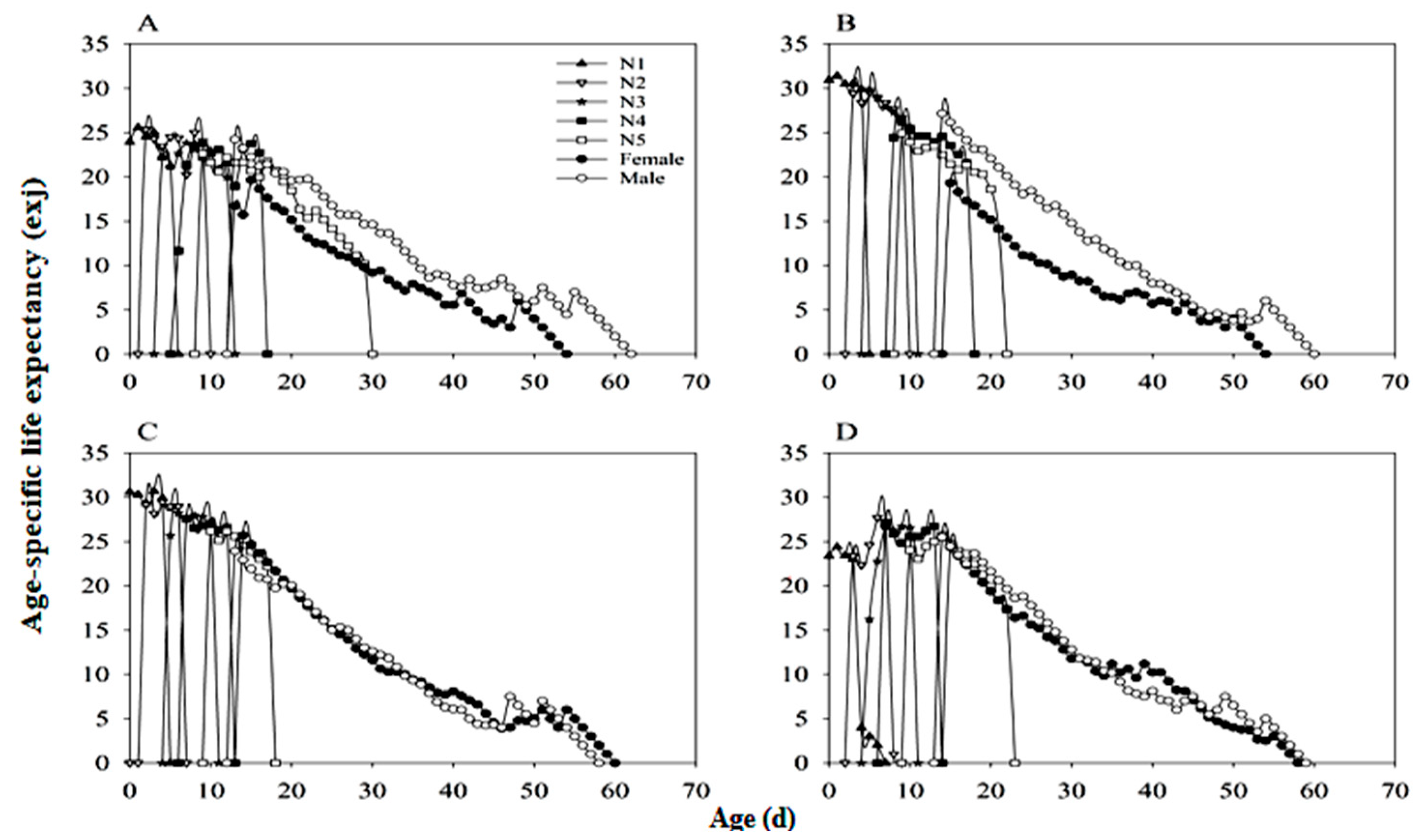

3.2. Effect of Ars on the Fitness of N. lugens Populations Fed on Different Rice Varieties

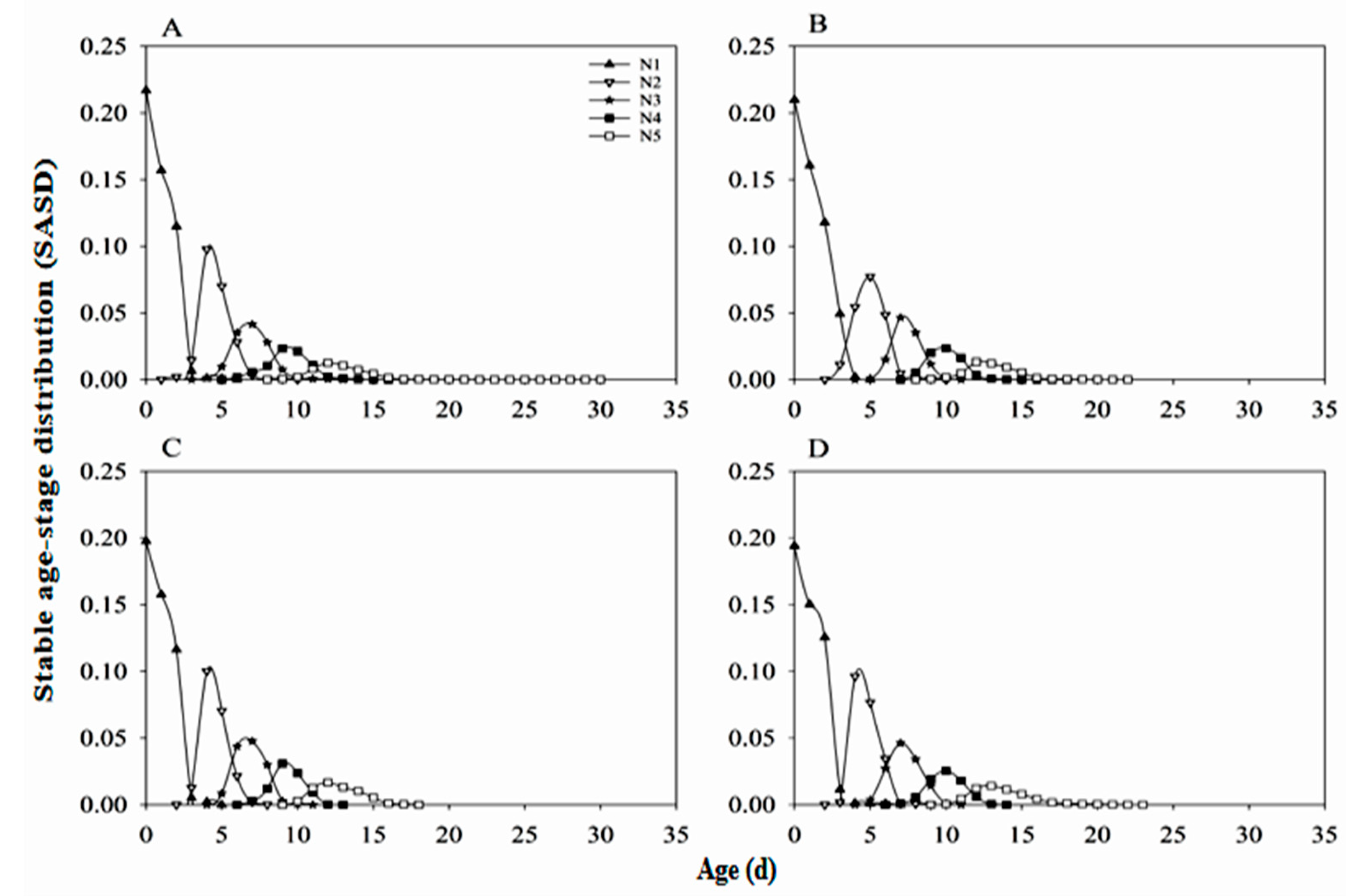

3.4. Stable Age-Stage Distribution of Nymphs (SASD)

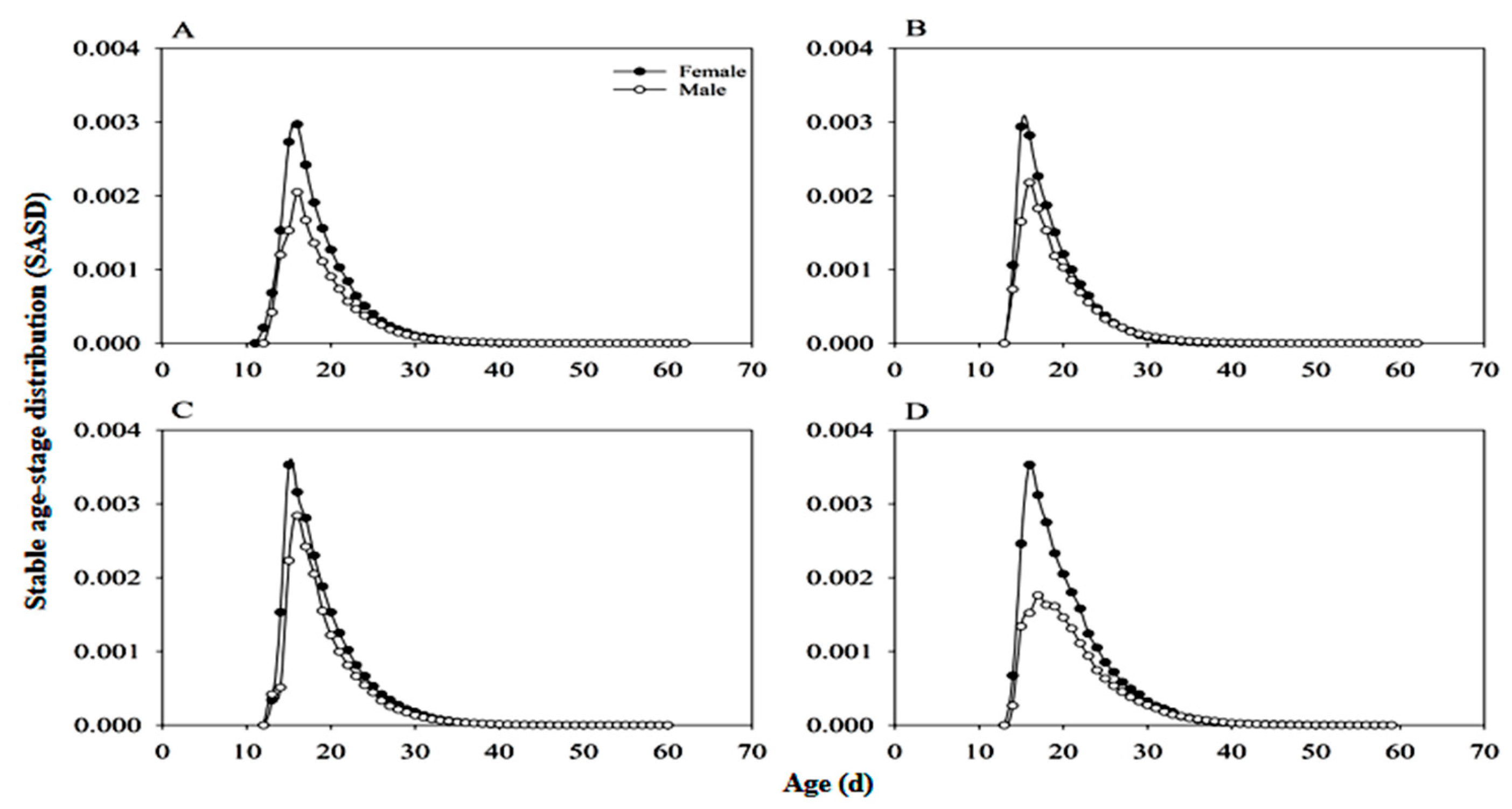

3.5. Stable Age-Stage Distribution of Adults (SASD)

3.6. Developmental Duration and Lifespan of N. lugens

3.7. Mortality Rate Distribution

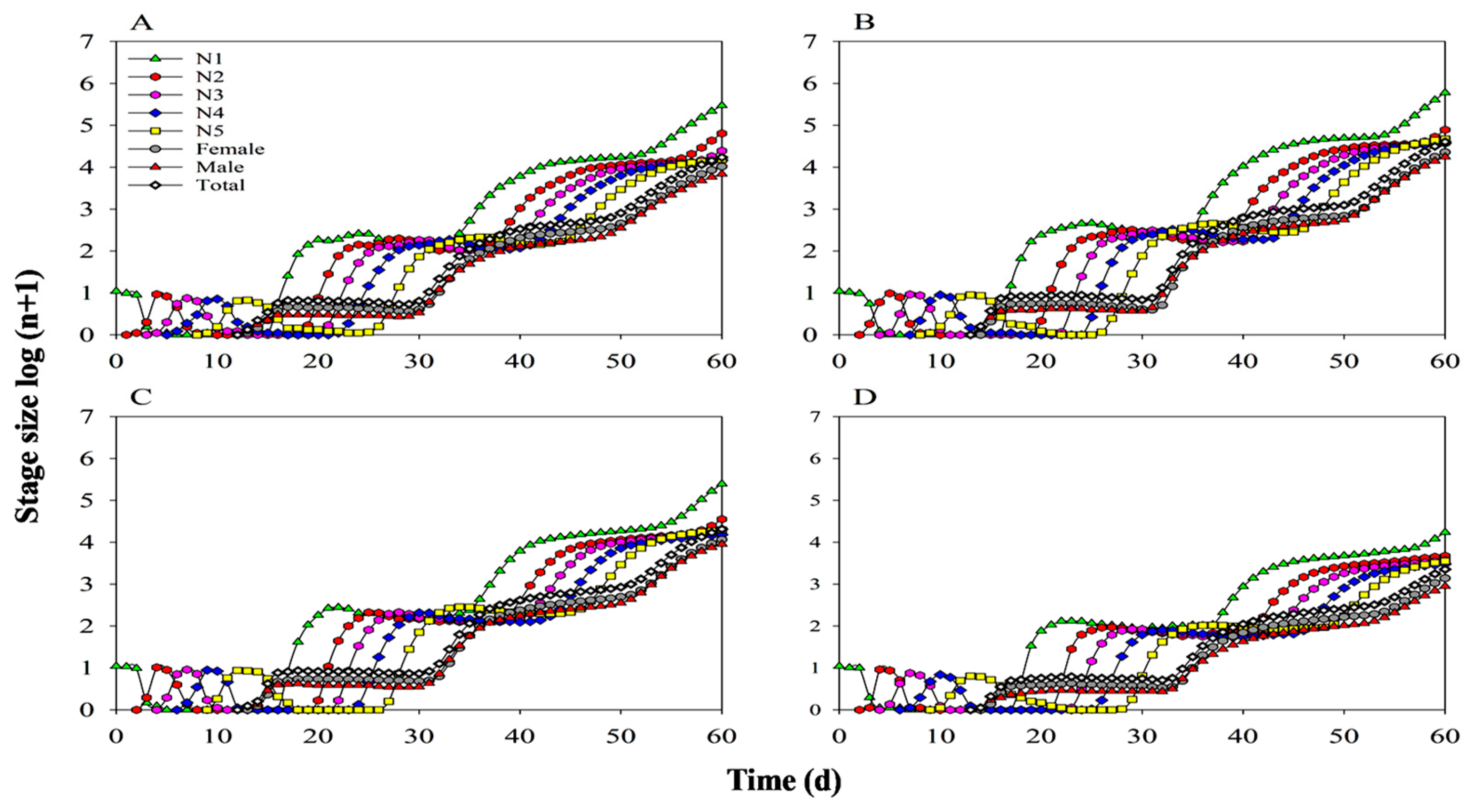

3.8. Population Parameters and Dynamics Predication

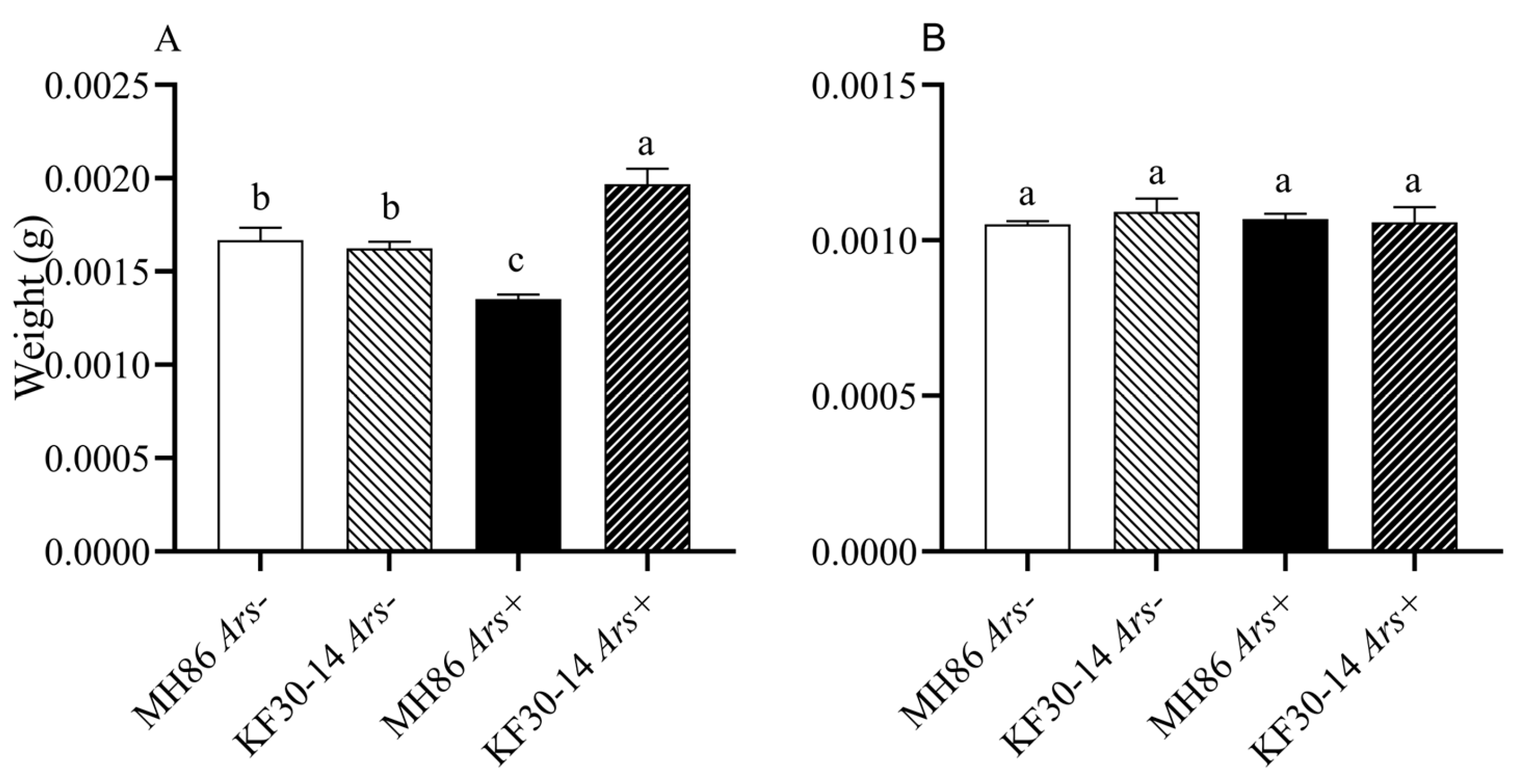

3.6. Effect of Arsenophonus on Adult Weight

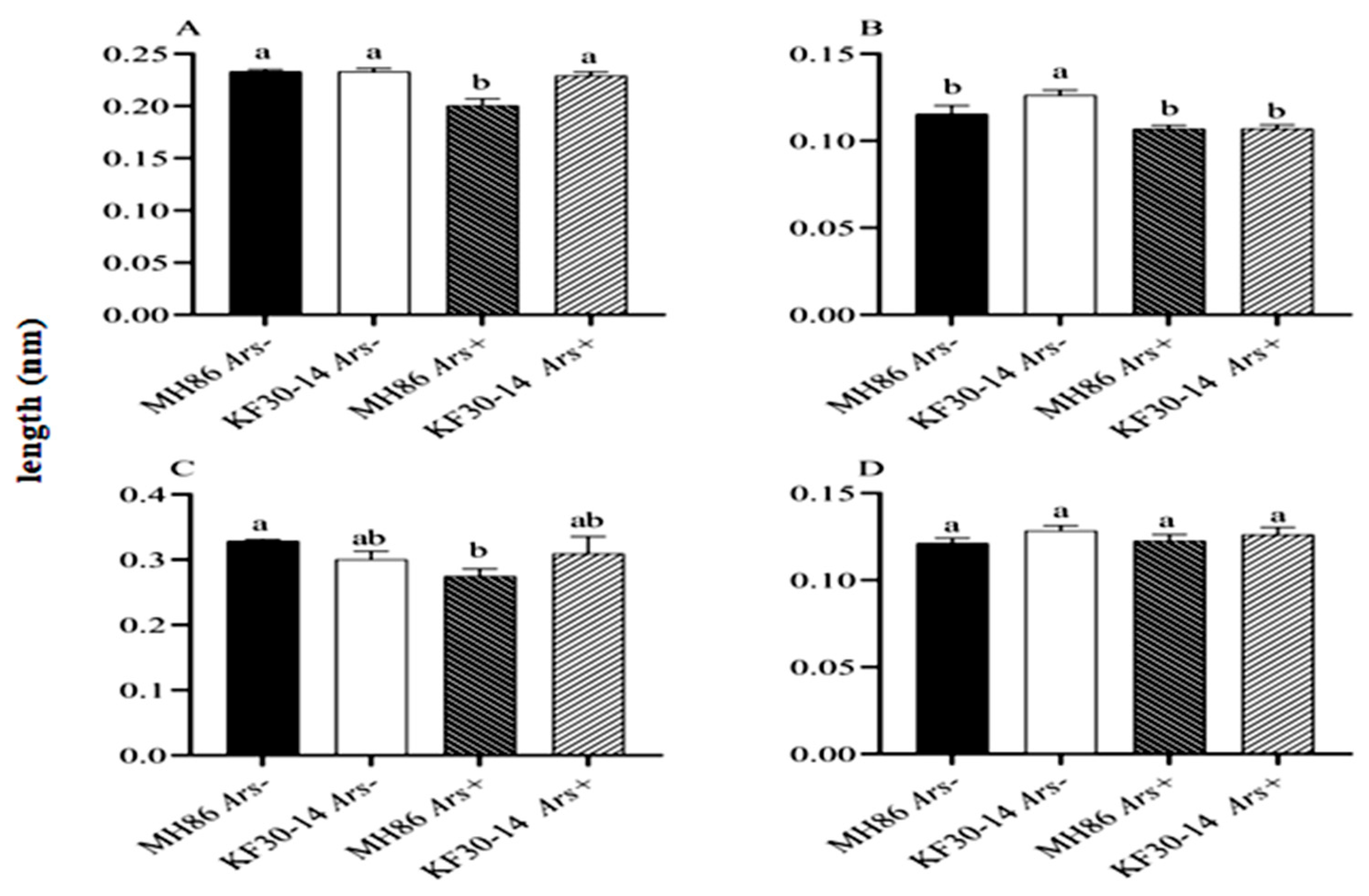

3.7. Effect of Arsenophonus on the Size of the Reproductive Organs of N. lugens Feeding on Different Rice Varieties

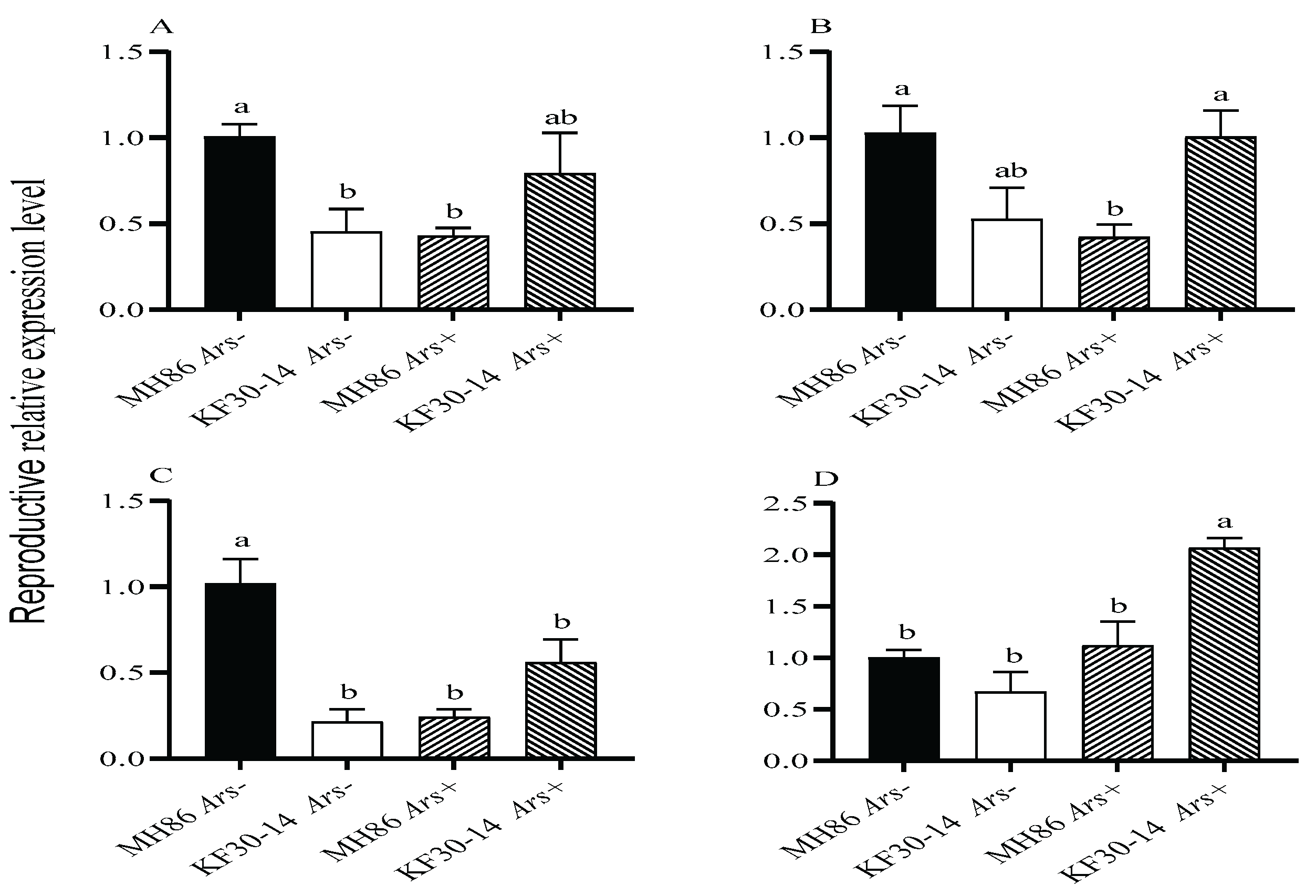

3.8. Effect of Arsenophonus Infection on the Expression of Reproductive Genes in Newly Eclosed Female Adults

3.9. Transcriptome Sequencing Quality and Differential Expression Analysis

3.9.1. KEGG Annotation Analysis

3.9.2. Differentially Expressed Genes Between Treatments and KEGG Enrichment Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matsumura, M et al. Species-specific insecticide resistance to imidacloprid and fipronil in the rice planthoppers Nilaparvata lugens and Sogatella furcifera in East and South-east Asia. Pest Management Science: formerly Pesticide Science 2008, vol. 64(no. 11), 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iamba, K.; Dono, D. A review on brown planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens Stål), a major pest of rice in Asia and Pacific. Asian J. Res. Crop Sci 2021, vol. 6, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, M. C.; Aguda, R. M.; Shepard, B. M.; Roberts, D. W. Infection of Rice Brown Planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Homoptera: Delphacidae), by Field Application of Entomopathogenic Hyphomycetes (Deuteromycotina). Environ Entomol 1986, vol. 15(no. 5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. P., H. X. X., L. Y. Y., & others Wang, Acquisition and identification of cry30Fa1 gene trans-genic rice resistant to Nilaparvata lugens. Chinese Journal of Rice Science, Chinese Journal of Rice Science 2016, vol. 30(no. 3), 256–264.

- Rupawate, P. S. et al. Role of gut symbionts of insect pests: A novel target for insect-pest control. Front Microbial 2023, vol. 14, 1146390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, K. et al. The multifaceted roles of gut microbiota in insect physiology, metabolism, and environmental adaptation: implications for pest management strategies. World J Microbial Biotechnol 2025, vol. 41(no. 3), 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, E. Nutritional interactions in insect-microbial symbioses: aphids and their symbiotic bacteria Buchnera. Annu Rev Entomol 1998, vol. 43(no. 1), 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Chen, H.; Yang, X.; Gao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, D. Gut bacteria induce oviposition preference through ovipositor recognition in fruit fly. Commun Biol 2022, vol. 5(no. 1), 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husnik, F. Horizontal gene transfer from diverse bacteria to an insect genome enables a tripartite nested mealybug symbiosis. Cell 2013, vol. 153(no. 7), 1567–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, P.; Moran, N. A. The gut microbiota of insects–diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbial Rev 2013, vol. 37(no. 5), 699–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behar, B. Yuval; Jurkevitch, E. Gut bacterial communities in the Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) and their impact on host longevity. J Insect Physiol 2008, vol. 54(no. 9), 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.-Y. Lysine provisioning by horizontally acquired genes promotes mutual dependence between whitefly and two intracellular symbionts. PLoS Pathog 2021, vol. 17(no. 11), e1010120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherna, R. L. Arsenophonus nasoniae gen. nov., sp. nov., the causative agent of the son-killer trait in the parasitic wasp Nasonia vitripennis. Int J Syst Evol Microbial 1991, vol. 41(no. 4), 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediannikov; Subramanian, G.; Sekeyova, Z.; Bell-Sakyi, L.; Raoult, D. Isolation of Arsenophonus nasoniae from Ixodes Ricinus ticks in Slovakia. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2012, vol. 3(no. 5–6), 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nováková, E.; Hypša, V.; Moran, N. A. Arsenophonus, an emerging clade of intracellular symbionts with a broad host distribution. BMC Microbial 2009, vol. 9(no. 1), 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, R. A distinct strain of Arsenophonus symbiont decreases insecticide resistance in its insect host. PLoS Genet 2018, vol. 14(no. 10), e1007725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- B., Z. F., L. Y. T., W. S. F., B. C., & G. C. F. Zeng, Symbiotic bacteria confer insecticide resistance by metabolizing buprofezin in the brown plant hopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål). PLoSPathogens 2023, vol. 19(no. 12), e101–1828.

- Liu, H. Arsenophonus and Wolbachia-mediated insecticide protection in Nilaparvata lugens. J Pest Sci (2004) 2025, vol. 98(no. 1), 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Insect genomes: progress and challenges. Insect Mol Biol 2019, vol. 28(no. 6), 739–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaech, H.; Dennis, A. B.; Vorburger, C. Triple RNA-Seq characterizes aphid gene expression in response to infection with unequally virulent strains of the endosymbiont Hamiltonella defensa. BMC Genomics 2021, vol. 22(no. 1), 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marguerat, S.; Bähler, J. RNA-seq: from technology to biology. Cellular and molecular life sciences 2010, vol. 67(no. 4), 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunfen, L. I.; Meng, H. E.; Cui, Y.; Peng, Y.; Liu, J.; Yun, Y. Insights into the mechanism of shortened developmental duration and accelerated weight gain associated with Wolbachia infection in Hylyphantes graminicola. Integr Zool 2022, vol. 17(no. 3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHEN, Y.; CHEN, Y.; WANG, W. A preliminary study on the transfer mode and biological significance of endosymbiont Arsenophonus in Nilaparvata lugens. Chinese Journal of Rice Science 2014, vol. 28(no. 1), 92. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, H. TWOSEX-MSChart: the key tool for life table research and education. Entomologia Generalis 2022, vol. 42(no. 6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H. TWOSEX-MSChart: the key tool for life table research and education. Entomologia Generalis 2022, vol. 42(no. 6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsin, C. H. Chi; Wei, F. J. Fu Jian; Sheng, Y. M. You Min. Age-stage, two-sex life table and its application in population ecology and integrated pest management. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Livak, K. J.; Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. methods 2001, vol. 25(no. 4), 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téfit, M. A.; Leulier, F. Lactobacillus plantarum favors the early emergence of fit and fertile adult Drosophila upon chronic undernutrition. Journal of Experimental Biology 2017, vol. 220(no. 5), 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Somani, J.; Roy, S.; Babu, A.; Pandey, A. K. Insect microbial symbionts: Ecology, interactions, and biological significance. Microorganisms 2023, vol. 11(no. 11), 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, H.; Keesey, I. W.; Hansson, B. S.; Knaden, M. Gut microbiota affects development and olfactory behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Journal of Experimental Biology 2019, vol. 222(no. 5), jeb192500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H. Host plant-mediated effects on Buchnera symbiont: implications for biological characteristics and nutritional metabolism of pea aphids (Acyrthosiphon pisum). Front Plant Sci 2023, vol. 14, 1288997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.; Moran, N. A. The impact of microbial symbionts on host plant utilization by herbivorous insects. Mol Ecol 2014, vol. 23(no. 6), 1473–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attardo, G. M.; Scolari, F.; Malacrida, A. Bacterial symbionts of tsetse flies: relationships and functional interactions between tsetse flies and their symbionts. Symbiosis: Cellular, Molecular, Medical and Evolutionary Aspects, 2020; 497–536. [Google Scholar]

- Bing, X. et al. Unravelling the relationship between the tsetse fly and its obligate symbiont Wigglesworthia: transcriptomic and metabolomic landscapes reveal highly integrated physiological networks. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2017, vol. 284(no. 1857), 20170360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Askari Seyahooei, M.; Izadi, H.; Bagheri, A.; Khodaygan, P. Effect of Arsenophonus endosymbiont elimination on fitness of the date palm hopper, Ommatissus lybicus (Hemiptera: Tropiduchidae). Environ Entomol 2019, vol. 48(no. 3), 614–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, R. Insecticide resistance reduces the profitability of insect-resistant rice cultivars. J Adv Res 2024, vol. 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S. C. Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science (1979) 2011, vol. 334(no. 6056), 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maistrenko, M.; Serga, S. V; Vaiserman, A. M.; Kozeretska, I. A. Longevity-modulating effects of symbiosis: insights from Drosophila–Wolbachia interaction. Biogerontology 2016, vol. 17(no. 5), 785–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q. et al. Combined effects of elevated CO2 concentration and Wolbachia on Hylyphantes graminicola (Araneae: Linyphiidae). Ecol Evol 2019, vol. 9(no. 12), 7112–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T. Insecticide susceptibility in a planthopper pest increases following inoculation with cultured Arsenophonus. ISME J 2024, vol. 18(no. 1), wrae194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y. et al. FoxO directly regulates the expression of TOR/S6K and vitellogenin to modulate the fecundity of the brown planthopper. Sci China Life Sci 2021, vol. 64(no. 1), 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Z. W. Y., X. X.; Huang, X. H.; et al. The effect of silencing juvenile hormone receptor on the reproductive capacity of female Leptoglossus gonagra (Hemiptera: Coreidae). Plant Protection 2023, vol. 49(no. 1), 164–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, J.; Xu, B.; Ge, L.-Q.; Yang, G.-Q.; Wu, J.-C. Long chain fatty acid coenzyme A ligase (FACL) regulates triazophos-induced stimulation of reproduction in the small brown planthopper (SBPH), Laodelphax striatellus (Fallen). Pestic Biochem Physiol 2018, vol. 148, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Lu, J.; Ye, Y.; Yu, X.; Zhang, C. Characteristics of the draft genome of ‘Candidatus Arsenophonus nilaparvatae’, a facultative endosymbiont of Nilaparvata lugens. Insect Sci 2016, vol. 23(no. 3), 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Development stage | Rice line | Arsenophonus- | Arsenophonus+ | |||

| n | Duration/d | n | Duration/d | |||

| 1st instar nymph | MH86 | 80 | 2.96±0.06* | 80 | 3.41±0.08a | |

| KF30-14 | 82 | 2.98±0.05 | 76 | 3.13±0.06b | ||

| 2st instar nymph | MH86 | 74 | 2.46±0.09 | 76 | 2.45±0.09 | |

| KF30-14 | 77 | 2.29±0.07 | 62 | 2.50±0.08 | ||

| 3st instar nymph | MH86 | 69 | 2.54±0.09 | 76 | 2.41±0.07b | |

| KF30-14 | 73 | 2.49±0.07* | 54 | 2.74±0.10a | ||

| 4st instar nymph | MH86 | 62 | 2.87±0.10a | 75 | 2.71±0.09 | |

| KF30-14 | 69 | 2.61±0.07b* | 50 | 2.88±0.10 | ||

| 5st instar nymph | MH86 | 56 | 4.25±0.20 | 69 | 4.16±0.13b | |

| KF30-14 | 65 | 4.34±0.08 | 44 | 4.89±0.27a | ||

| Adult longevity | MH86 | 56 | 19.46±1.44 | 69 | 21.02±1.15 | |

| KF30-14 | 65 | 22.84±1.16 | 44 | 22.70±1.41 | ||

| Male adult longevity | MH86 | 21 | 22.10±2.84 | 28 | 25.36±1.91 | |

| KF30-14 | 28 | 21.61±2.03 | 17 | 23.35±2.53 | ||

| Female adult longevity | MH86 | 35 | 17.89±1.52 b | 41 | 18.07±1.25 b | |

| KF30-14 | 37 | 23.78±1.35 a | 27 | 22.30±1.69 a | ||

| Total longevity | MH86 | 89 | 23.97±1.71 b* | 84 | 30.93±1.55 a | |

| KF30-14 | 84 | 30.57±1.68 a | 83 | 23.34±1.97 b* | ||

| Parameters | Rice line | Arsenophonus- | Arsenophonus+ | |||

| n | Duration/d | n | Duration/d | |||

| Adultpre-ovipositionperiod (APOP) | MH86 | 33 | 2.97±0.27 a | 39 | 2.67±0.16 b | |

| KF30-14 | 37 | 3.51±0.23 a* | 27 | 4.33±0.30 a | ||

| Total preoviposition period (TPOP) | MH86 | 33 | 18.36±0.63 a | 39 | 18.03±0.31 b | |

| KF30-14 | 37 | 18.41±0.28 a* | 27 | 20.41±0.51 a | ||

|

Oviposition days (Od) |

MH86 | 33 | 13.33±46a | 39 | 14.18±1.33a | |

| KF30-14 | 37 | 17.16±1.40a | 27 | 14.22±1.40a | ||

|

Fecundity |

MH86 | 33 | 349.12±43.87a | 39 | 407.72±44.86a | |

| KF30-14 | 37 | 373.62±39.04a | 27 | 255.93±34.78b* |

| Development stage | Rice line | Arsenophonus- | Arsenophonus+ | ||

| 1st instar nymph | MH86 | 0.10±0.03a | 0.05±0.02a | ||

| KF30-14 | 0.02±0.02b | 0.08±0.03a | |||

| 2st instar nymph | MH86 | 0.07±0.03a | 0.05±0.02b | ||

| KF30-14 | 0.06±0.03a | 0.17±0.04a | |||

| 3st instar nymph | MH86 | 0.06±0.02a | 0.00±0.00b* | ||

| KF30-14 | 0.05±0.02a | 0.10±0.03a | |||

| 4st instar nymph | MH86 | 0.08±0.03a | 0.01±0.01a* | ||

| KF30-14 | 0.05±0.02a | 0.05±0.02 a | |||

| 5st instar nymph | MH86 | 0.07±0.03a | 0.07±0.03a | ||

| KF30-14 | 0.05±0.02a | 0.07±0.03a | |||

| Immature | MH86 | 0.37±0.05a | 0.18±0.04b* | ||

| KF30-14 | 0.23±0.05b* | 0.47±0.05a | |||

| Female adult | MH86 | 0.39±0.05a | 0.49±0.05a | ||

| KF30-14 | 0.44±0.05a | 0.33±0.05b | |||

| Male adult | MH86 | 0.24 ± 0.04a | 0.33±0.05a | ||

| KF30-14 | 0.33±0.05a | 0.20±0.04a | |||

| Adult | MH86 | 0.63±0.05b* | 0.82±0.04a | ||

| KF30-14 | 0.77±0.05a | 0.53±0.05b* | |||

| Population parameters | Rice varieties | Arsenophonus- | Arsenophonus+ | |||

| Intrinsic rate of increase (d-1) | MH86 | 0.204±0.009a | 0.218±0.008a | |||

| KF30-14 | 0.202±0.007a | 0.167±0.010 b* | ||||

| Mean generation time (d-1) | MH86 | 23.805±0.432 b | 24.041±0.311 b | |||

| KF30-14 | 25.272±0.410 a | 26.340±0.720 a | ||||

| Net reproductive rate | MH86 | 129.449±24.021 a | 189.298±30.262 a | |||

| KF30-14 | 164.571±26.67a | 83.253±18.237 b* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).