1. Introduction

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) have become indispensable tools in modern marine engineering and oceanography, playing a pivotal role in tasks such as seabed mapping, resource exploration, pipeline inspection, and environmental monitoring. As mission complexity increases, single-AUV systems are often constrained by limited energy endurance and operational efficiency. Consequently, Multi-AUV systems have garnered significant attention due to their ability to perform cooperative tasks with higher efficiency, robustness, and fault tolerance.[

1] However, achieving effective cooperative path planning for multiple AUVs remains a formidable challenge, particularly in complex, dynamic marine environments characterized by time-varying ocean currents and irregular seabed terrain.

The core objective of cooperative path planning is to generate collision-free and energy-efficient trajectories for multiple vehicles while maintaining formation or spatiotemporal coordination. Classical global planning algorithms, such as A* and Dijkstra, have been widely applied to static environments but often struggle with the computational burden in dynamic, high-dimensional spaces. Sampling-based methods like Rapidly-exploring Random Tree (RRT)[

2] and its variants offer probabilistic completeness but may generate jagged, suboptimal paths. More recently, heuristic intelligence algorithms, including Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), have demonstrated potential in optimizing multi-objective constraints.[

2] However, these global methods typically rely on prior map information and may lack sufficient responsiveness to real-time environmental disturbances. Deep reinforcement learning has also been explored for AUV path planning under ocean current disturbances[

4].

To address local avoidance and dynamic adaptation, reactive methods such as Artificial Potential Fields (APF) and the Dynamic Window Approach (DWA) are commonly employed.[

5] While computationally efficient, APF is prone to local minima, and standard DWA may not fully account for the kinematic constraints of underactuated AUVs in strong currents. Furthermore, a critical limitation in most existing literature is the deterministic treatment of environmental risks. Traditional approaches often simplify obstacles as binary constraints (occupied or free) and treat ocean currents merely as vector disturbances. In reality, the underwater environment is stochastic; risks arising from steep terrain, variable current shear, and equipment uncertainty are probabilistic rather than deterministic. Neglecting this probabilistic nature can lead to overly conservative paths or, conversely, risky trajectories that jeopardize vehicle safety.

To overcome these limitations, Receding Horizon Planning (RHP), or Model Predictive Control (MPC), has emerged as a powerful framework for handling dynamic constraints and uncertainties by optimizing trajectories over a finite moving horizon. Nevertheless, integrating a comprehensive, probabilistic risk assessment module directly into the RHP optimization loop for multi-AUV cooperation remains an open research problem.

In this paper, we propose a risk-aware cooperative path planning method for multiple AUVs, specifically designed for complex marine environments. Unlike traditional methods, we introduce a Conditional Bayesian Network (CBN) to quantify environmental risks probabilistically. By inferring the causal relationships between environmental factors (e.g., current intensity, terrain complexity) and vehicle safety, the CBN provides a continuous risk gradient map. This probabilistic risk is then embedded into the cost function of a distributed RHP framework, allowing AUVs to actively trade off between path efficiency, energy consumption, and safety probabilities.

It is important to note that the probabilistic risk considered in this study is not intended to represent an absolute or statistically calibrated failure probability. Instead, it serves as a relative and planning-oriented risk index, whose primary role is to provide consistent safety-aware guidance for cooperative trajectory optimization in complex marine environments.

Different from existing deterministic or reactive planning approaches, the novelty of this work lies not in proposing an entirely new optimization framework, but in tightly coupling probabilistic environmental risk inference with cooperative trajectory optimization. In particular, the proposed method embeds a CBN-derived, continuously varying risk metric directly into the receding-horizon planning loop, allowing multi-AUV systems to proactively balance efficiency and safety under realistic, time-varying ocean current conditions.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

A probabilistic risk assessment model: We construct a Conditional Bayesian Network (CBN) to infer relative risk levels dynamically, integrating factors such as terrain slope, current velocity, and obstacle proximity, which provides a more realistic safety metric than binary obstacle maps.

A risk-aware cooperative planning framework: We propose a distributed Receding Horizon Planning algorithm that incorporates the CBN-derived risk cost, enabling multi-AUV systems to navigate complex canyon environments while balancing energy consumption, formation maintenance, and collision avoidance.

Validation in realistic simulation environments: The proposed method is validated using real-world bathymetric data from the South China Sea and reanalysis data from the HYCOM ocean current model. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed approach significantly improves mission success rates and safety margins compared to deterministic baselines.

2. Problem Formulation and Environmental Modeling

2.1. Coordinate System and Motion Model of AUVs

A three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system is established to describe the motion of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) in the marine environment. The position of the

AUV at time

is defined as

where

,

, and

denote the coordinates of the AUV along the

,

, and

, respectively.

The kinematic model of the AUV motion under the influence of ocean currents is expressed as[

6]

where

denotes the control velocity vector of the AUV relative to the surrounding water, and

represents the ocean current velocity at position

and time

.

The control velocity of each AUV is constrained by the maximum allowable speed:

where

is the maximum cruising speed of the AUV.

2.2. Dynamic Marine Environment Modeling

In realistic marine environments, ocean currents vary both spatially and temporally. The ocean current field is modeled as a time-varying vector field:

where

,

, and

represent the current velocity components along the

,

, and

, respectively.

To represent environmental constraints, dynamic obstacles and restricted regions are defined as obstacle sets:

where

is a time-dependent function describing the boundary of the

obstacle.

An AUV trajectory is considered feasible if it satisfies the following condition throughout the planning horizon:

2.3. Cooperative Constraints for Multiple AUVs

For a multi-AUV system consisting of

vehicles, collision avoidance between AUVs must be ensured. The minimum safe distance between any two AUVs

and

is defined as Dsafe. The inter-vehicle distance constraint is formulated as

Each AUV has a specified initial position and target position:

where

and

denote the initial and goal positions of the

AUV, respectively, and

represents the terminal time of the mission.

2.4. Objective Function

The cooperative path planning objective is to generate safe, efficient, and coordinated trajectories for all AUVs. The overall cost function of the multi-AUV system is defined as

where

is the individual cost function of the

AUV.

The cost function

is formulated as

where

denotes the total path length,

represents the energy consumption,

is the traveling time, and

,

, and

are weighting coefficients.

The path length is calculated as

and the energy consumption is approximated by

2.5. Problem Statement

Based on the above formulations, the cooperative path planning problem for multiple AUVs in dynamic marine environments can be summarized as the following constrained optimization problem:

Subject to:

for all

and

.

3. Cooperative Path Planning Algorithm for Multiple AUVs

3.1. Overview of the Cooperative Planning Framework

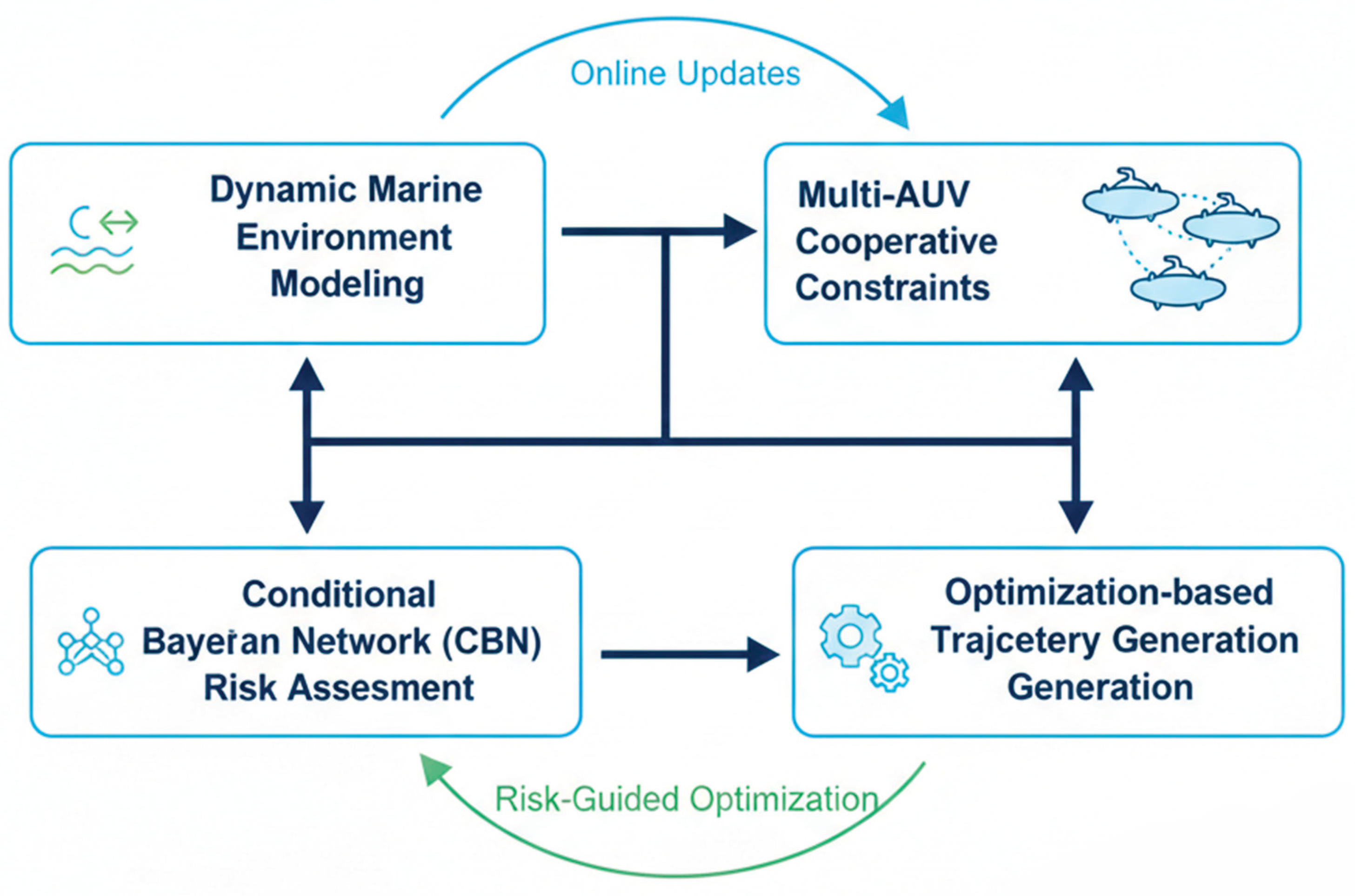

Based on the problem formulation presented in

Section 2, a cooperative path planning framework for multiple autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) operating in complex dynamic marine environments is developed. From a methodological perspective, the proposed approach can be categorized as a

risk-aware receding-horizon trajectory optimization framework for cooperative multi-AUV systems. Rather than pursuing globally optimal solutions over the entire mission duration, the framework focuses on generating

engineering-feasible, safe, and computationally tractable trajectories under time-varying environmental conditions.

The proposed framework integrates environmental perception, cooperative coordination, and trajectory optimization into a unified planning process. Its core objective is to generate coordinated AUV trajectories that simultaneously satisfy vehicle dynamic constraints, environmental safety requirements, and inter-vehicle cooperation constraints, while minimizing a composite cost function that accounts for path efficiency, energy consumption, and mission duration.

A key distinguishing feature of the proposed framework is the explicit incorporation of probabilistic environmental risk inference into the planning process. In particular, a conditional Bayesian network (CBN) is employed to infer spatially varying failure probability based on coupled terrain features, ocean current characteristics, and environmental uncertainty. It is emphasized that the CBN-based risk model is not used as a post-processing evaluation tool, but serves as a decision-driving component that directly influences trajectory generation during optimization. By embedding probabilistic risk into the objective function and constraint handling strategy, the planner is guided toward trajectories that balance efficiency and safety in a principled manner.

The overall planning process follows a receding-horizon strategy and consists of four main stages:

- i.

the dynamic marine environment, including time-varying ocean currents and obstacle information, is modeled and updated over the planning horizon;

- ii.

cooperative constraints among multiple AUVs are enforced to guarantee collision avoidance and coordinated motion;

- iii.

the CBN-based risk inference module evaluates spatially distributed environmental risk and provides risk-related guidance to the planner;

- iv.

a trajectory optimization procedure generates coordinated AUV paths by minimizing a composite cost function while penalizing risk exposure and constraint violations.

Figure 1 illustrates the information flow of the proposed cooperative planning framework. As shown, environmental modeling, cooperative coordination, and risk inference are tightly coupled within the optimization loop. This integration enables the planner to proactively avoid hazardous regions and unfavorable flow conditions, rather than reacting to them after trajectory generation. Such a design is particularly suitable for multi-AUV operations in complex marine environments, where safety, robustness, and computational efficiency are of primary concern.

3.2. Path Representation and Discretization

To facilitate numerical optimization, the continuous trajectory of each AUV is discretized into a sequence of waypoints. The trajectory of the

AUV is represented as

where

denotes the position of the

AUV at the

waypoint, and

is the total number of waypoints.

The distance between two consecutive waypoints is constrained to ensure feasible motion and numerical stability. The discretized trajectory provides a practical representation for evaluating path length, collision avoidance, and energy consumption.

3.3. Cooperative Interaction Modeling

To achieve cooperative behavior among multiple AUVs, interaction constraints are incorporated into the planning process. For any two AUVs

and

, the relative distance between their trajectories at corresponding time steps must satisfy the safety constraint:

for all

and

.

This constraint ensures that inter-vehicle collisions are avoided throughout the mission. By enforcing the cooperative constraint at each discretized waypoint, the planning algorithm maintains safe separation among all AUVs during coordinated operations.

3.4. Optimization-Based Path Planning Model

Based on the discretized path representation, the cooperative path planning problem is transformed into a constrained optimization problem. The objective is to minimize the total cost function defined in

Section 2.4 while satisfying dynamic, environmental, and cooperative constraints.

The discretized form of the cost function for the

AUV is expressed as

where

denotes the control velocity at the

waypoint.

The control velocity

is approximated by

where

is the time interval between two consecutive waypoints, and

represents the ocean current velocity at the corresponding position and time.

3.5. Probabilistic Risk Modeling via Conditional Bayesian Network

To explicitly quantify the impact of complex marine environments on AUV safety, we construct a Conditional Bayesian Network (CBN).[

7] Unlike deterministic obstacle avoidance, the CBN maps environmental features to a probabilistic risk metric, termed as the inferred failure probability or relative navigation risk. Unlike conventional approaches where risk metrics are computed a posteriori for performance assessment, the CBN in this framework actively shapes the optimization landscape by providing a continuous risk gradient that directly influences trajectory updates at each planning step. As a result, risk awareness functions as a decision-driving component of the cooperative planner, rather than an external constraint or heuristic penalty.

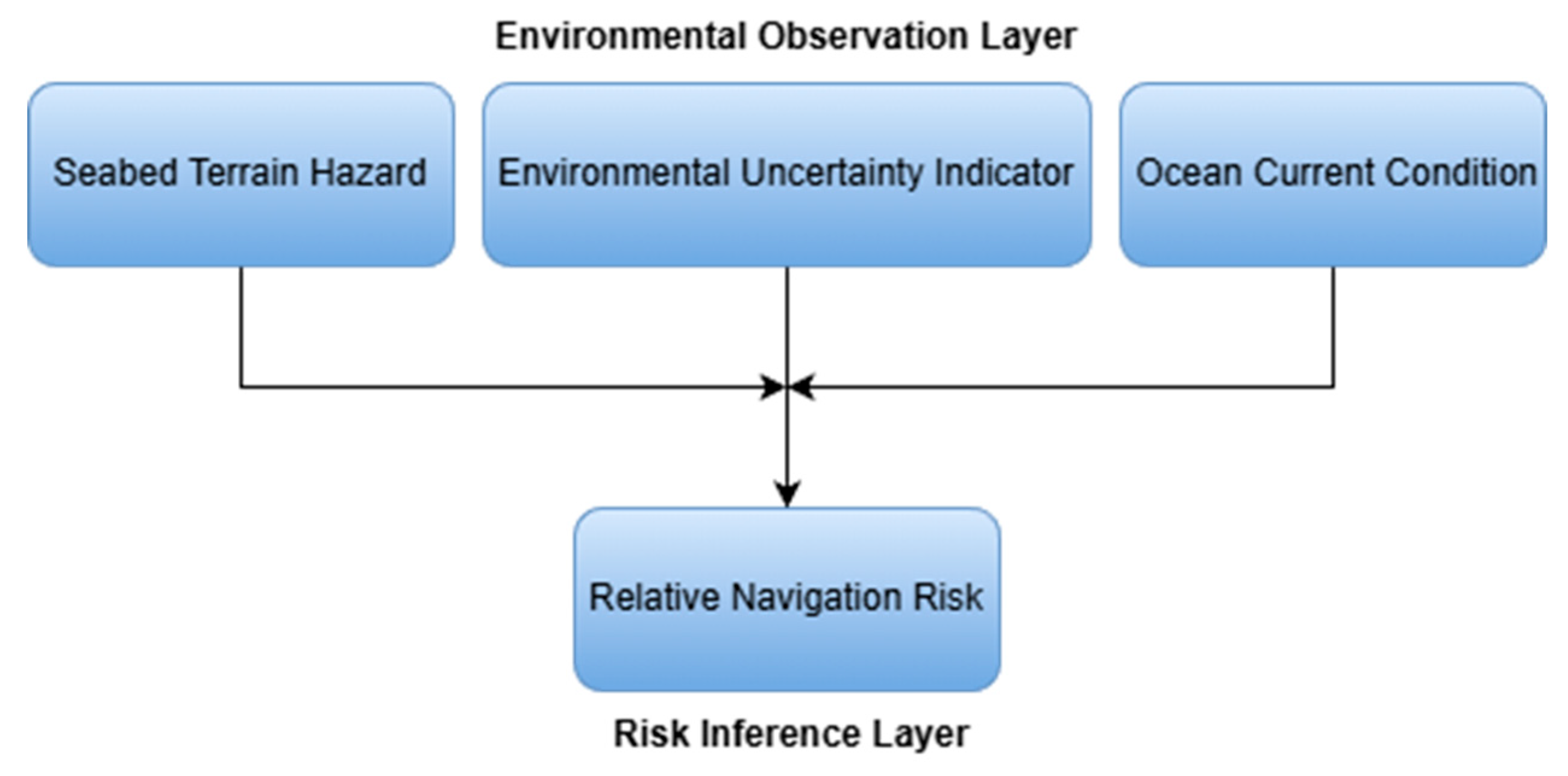

3.5.1. Network Topology and Variables

The proposed CBN structure is designed to capture the causal relationship between environmental stressors and operational risk. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the network is organized into two functional layers: the Environmental Observation Layer and the Risk Inference Layer.

Parent Node 1: Seabed Terrain Hazard (): Represents the risk associated with static geomorphic features. It aggregates factors such as local seabed slope and terrain ruggedness, which limit the AUV’s maneuvering space.

Parent Node 2: Ocean Current Condition (): Encodes the hydrodynamic threat level, derived from the intensity and turbulence of the local flow field. High-velocity currents increase the probability of control loss.

Parent Node 3: Environmental Uncertainty Indicator (): Accounts for the reliability of sensing data. High turbidity or sensor noise leads to higher uncertainty, thereby increasing the latent risk of collision.

Child Node: Relative Navigation Risk (): The output node representing the posterior probability of mission failure or collision given the current environmental states.

3.5.2. Mathematical Formulation

The CBN defines the joint probability distribution over the set of variables. Assuming the environmental inputs are conditionally independent given the specific location, the joint distribution is formulated as:

where represents the Conditional Probability Table (CPT) that quantifies the risk level under specific combinations of environmental states.

3.5.3. Engineering-Informed Probability Assignment

Defining the CPTs is critical. Since obtaining absolute actuarial failure rates for AUVs in specific sea areas is impractical due to data sparsity, we adopt an engineering-informed, normalized relative probability assignment approach.

We define the risk not as an absolute frequency of failure, but as a normalized relative risk index ranged in

. The conditional probabilities are assigned based on a sigmoid-like mapping function of the normalized environmental intensity:

where

is the vector of environmental evidence,

is the weighted intensity of the adverse environment, and

are shaping parameters determined by the vehicle's maneuverability constraints. This formulation ensures that the inferred risk increases non-linearly as environmental conditions deteriorate, reflecting the "edge of safety" effect in marine robotics.

The inferred does not represent an absolute failure probability, but rather a relative risk index for planning purposes. It should be emphasized that the objective of the CBN is not to estimate statistically calibrated failure probabilities, but to provide a consistent relative risk ordering that is sufficient for guiding trajectory optimization in engineering planning problems. The planner relies primarily on relative risk gradients rather than absolute probability values, which is appropriate for risk-aware path planning under limited environmental statistics. Instead, it serves as a normalized, relative risk index designed to guide path planning decisions by ranking environmental hazard levels in a consistent and interpretable manner.

The parameters α and β control the sharpness and offset of the risk transition and are selected based on vehicle maneuverability limits and engineering experience. A brief sensitivity analysis indicates that moderate variations of the shaping parameters (α, β) affect the absolute magnitude of the inferred risk index but do not alter the spatial ranking of high-risk and low-risk regions. Since the cooperative planner depends mainly on relative risk ordering rather than absolute probability values, the resulting planning behavior remains qualitatively consistent. While different parameter choices may affect the absolute magnitude of the inferred risk index, preliminary sensitivity tests indicate that the relative spatial ranking of high-risk and low-risk regions remains consistent. Since the planner relies on relative risk gradients rather than absolute probability values, the qualitative conclusions of this study are not sensitive to moderate variations in these parameters.

3.6. Constraint Handling Strategy

To ensure feasibility of the planned paths, constraint handling techniques are integrated into the optimization process. Environmental constraints, including obstacle avoidance and boundary limitations, are enforced by introducing penalty functions or feasibility checks during the optimization.

For obstacle avoidance, a penalty term is introduced when a waypoint violates the obstacle constraint:

Similarly, cooperative constraints are handled by penalizing violations of the minimum safety distance between AUVs.

By incorporating these constraint handling strategies, the optimization algorithm is guided toward feasible solutions that satisfy all safety and operational requirements.

3.7. Algorithm Implementation Procedure

Algorithm 1. Risk-aware cooperative path planning for multi-AUV systems

Input:

Initial positions of AUVs , ; goal positions , ; dynamic marine environment model (ocean currents, obstacles); CBN-based risk field ; planning horizon T; number of waypoints N.

Output:

Cooperative trajectories , , .

1: Initialize feasible trajectories , , using straight-line paths or heuristic planning.

2: Set iteration index n = 0.

3: while convergence criterion is not satisfied do

4: Update the dynamic marine environment, including the ocean current field and obstacle information.

5: For each AUV , evaluate the local environmental risk using the CBN-based risk inference model.

6: Compute the cooperative cost function

7: Enforce cooperative constraints for all AUV pairs , :

8: Enforce environmental constraints, including obstacle avoidance and boundary limitations.

9: Update trajectories by solving the constrained trajectory optimization problem.

10: Set n = n + 1.

11: end while

12: Output the optimized cooperative trajectories , .

3.8. Computational Considerations

The proposed cooperative path planning algorithm is designed with computational efficiency in mind. By discretizing trajectories and applying cooperative constraints locally at each waypoint, the computational complexity increases approximately linearly with the number of AUVs and waypoints.

This property makes the proposed method suitable for real-time or near-real-time applications in marine engineering tasks involving multiple AUVs.

In this study, the constrained trajectory optimization problem is solved using a gradient-based numerical optimizer within a receding-horizon framework, where each AUV optimizes its local trajectory segment while exchanging minimal coordination information with neighboring vehicles.

4. Simulation Setup and Experimental Scenarios

4.1. Numerical Testbed and Marine Environment

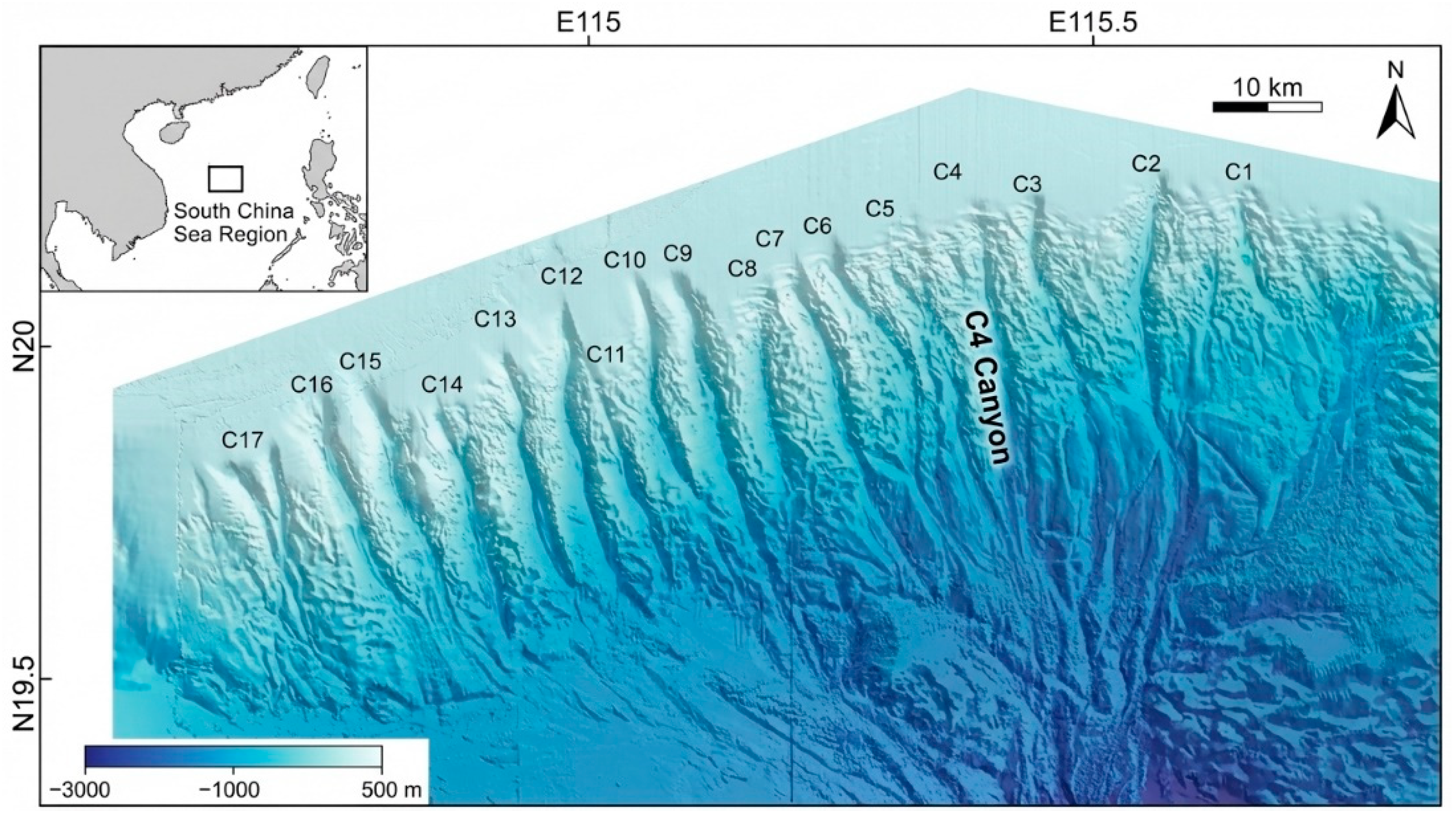

To evaluate the proposed cooperative path planning method, a three-dimensional numerical testbed is constructed for a representative canyon environment. The bathymetry is derived from global gridded data and higher-resolution multibeam measurements,[

8] providing a realistic description of steep slopes, terraces and local topographic irregularities along the canyon axis. The test region is located on the northern slope of the South China Sea and includes the C4 canyon,[

9] a typical slope canyon where water depth increases from approximately 700–800 m near the shelf edge to about 1700–1800 m in the basin. The axial slope is moderate on average, while local sidewalls can be very steep,[

10] which poses challenges for safe AUV navigation close to the seabed.

Figure 3 illustrates the bathymetric layout of the canyon test area located on the northern slope of the South China Sea. The C4 canyon and its tributaries define a complex terrain environment characterized by steep sidewalls and narrow passages, which pose significant challenges for safe and energy-efficient AUV navigation.

This spatial context is later used to interpret how planned trajectories align with the canyon axis and how risk varies with local topography. In addition to bathymetry, the time-varying current field is interpolated onto the same grid so that both terrain constraints and hydrodynamic forcing can be consistently evaluated during cooperative planning.

The background ocean circulation and mesoscale variability are represented by reanalysis current fields that are dynamically consistent with regional observations.[

11] The three-dimensional current field is interpolated onto the computational grid of the testbed, and temporal interpolation is employed to obtain time-varying current velocities during the simulations. In this way, both along-canyon flows and cross-canyon shear structures are included in the environment used for numerical experiments.[

12]

A risk field is precomputed based on the joint risk assessment model described in the previous sections. This field accounts for terrain-related hazards, strong bottom currents and regions of enhanced environmental uncertainty. During the simulations, this risk field is used to quantify exposure to high-risk regions and to drive the cooperative planning strategy toward safer paths.

The computational domain is discretized with a horizontal grid spacing that balances the need to resolve key bathymetric and current features with the available computational resources. Vertically, the water column is divided into layers that capture near-bottom dynamics as well as intermediate-depth flows that may influence vehicle trajectories. The simulation time step is set to 1 s, and the maximum mission duration is 7200 s, which corresponds to a 2-hour operational window typical for medium-range AUV missions in such environments.

4.2. AUV Fleet Configuration and Mission Profiles

The numerical experiments consider a fleet of four identical AUVs forming a cooperative group. Each vehicle is modeled using the dynamic and kinematic equations introduced earlier, with parameters representative of a medium-size survey-class AUV.[

13] The maximum cruising speed, minimum turning radius and safe separation distance

are chosen to reflect realistic maneuvering capabilities and collision-avoidance requirements.

At the start of each simulation, the four AUVs are positioned near the canyon entrance at a depth of approximately 800 m. Their mission is to traverse the canyon and reach a designated target region located near 1600 m depth, while performing cooperative area search along the canyon axis. Initial headings are randomized within a prescribed range to emulate practical deployment uncertainties.

The fleet operates under the cooperative planning framework described previously. Each AUV executes local path segments produced by the planner, while inter-vehicle constraints ensure that the minimum separation distance is respected at all times. The environment-aware component of the method guides trajectories toward down-current and low-shear corridors when beneficial, and away from high-risk zones identified by the risk field.

Dynamic obstacles can be included in the testbed to represent intermittent hazards such as trawling activity, temporary equipment or other underwater vehicles. In these cases, obstacle locations and motions are prescribed and updated during the simulations, and the planner treats them as time-varying constraints that must be avoided.

4.3. Performance Metrics

To quantitatively assess the performance of the cooperative path planning method, several metrics are evaluated over multiple simulation runs:

Success rate (SR)

The success rate is defined as the proportion of trials in which all AUVs reach the target region within the mission time without collision, loss of vehicles or violation of safety constraints. A higher SR indicates more robust cooperative behavior in complex environments.

2.

Energy consumption index (ECI)

The energy consumption index represents the average energy consumption per unit distance, with units of kJ/km. It is obtained by integrating the propulsion power over the mission for each AUV and normalizing by the corresponding path length, then averaging over the fleet. A smaller ECI implies more energy-efficient trajectories.

3.

Path smoothness (CurvRMS)

Path smoothness is quantified by the root mean square curvature of each trajectory, computed along the path length and then averaged over the fleet. This metric, denoted CurvRMS and expressed in 1/km, reflects how frequently and how strongly the vehicles need to turn. Smaller CurvRMS values correspond to smoother paths that are easier to track and more compatible with the limited maneuverability of underactuated AUVs.

4.

High-risk exposure ratio ()

The high-risk exposure ratio is defined as the percentage of mission time during which an AUV operates in grid cells where the failure probability exceeds a specified threshold (for example, > 0.6). is computed for each AUV and then averaged over the fleet. Lower values indicate that the cooperative planner successfully steers vehicles away from hazardous regions identified by the risk model.

5.

Planning and communication frequencies (, )

To characterize computational and communication load, the average planning frequency and average communication frequency are monitored. measures how often global or regional replanning events occur during a mission, while measures how often inter-AUV or AUV-to-base communication is triggered. Lower and values, for comparable mission performance, indicate higher efficiency and better suitability for bandwidth-limited and power-constrained multi-AUV operations.

Unless otherwise stated, the weighting coefficients and risk model parameters are kept consistent across all simulation scenarios to ensure fair comparison between planning schemes.

4.4. Baseline Definition and Performance Benchmarking

To rigorously evaluate the advantages of the proposed CBN-based risk-aware method, we define a Conventional Risk-Agnostic Cooperative Scheme (CR-ACS) as the primary baseline for comparison.

4.4.1. Logic of the Baseline (CR-ACS)

The CR-ACS represents the state-of-the-art deterministic approach commonly used in multi-AUV coordination. Unlike our proposed method, the baseline treats environmental hazards as binary constraints rather than probabilistic risks. Specifically:

Collision Avoidance: It utilizes a fixed safety buffer () to keep AUVs away from seabed terrain and obstacles. A collision is defined only when the Euclidean distance .

Ocean Currents: It considers the average current velocity for energy estimation but lacks the non-linear coupling between current turbulence and navigation risk.

Environmental Uncertainty: It assumes perfect sensing information and does not incorporate the "Uncertainty Indicator" into its decision-making process.

4.4.2. Cost Function Comparison

The core difference lies in the optimization objective. While the proposed method minimizes the posterior risk

derived from the CBN, the baseline minimizes a standard weighted cost function:

subject to the deterministic constraint:

where denotes the distance to the goal and is set to a constant value (e.g., 5 meters) based on the AUV’s physical dimensions. By comparing our method with CR-ACS, we can isolate the specific contribution of the probabilistic risk awareness provided by the CBN.

4.5. Baseline Selection and Comparison Rationale

The baseline cooperative planning strategy considered in this study is designed to represent a commonly adopted engineering-oriented approach for multi-AUV operations in dynamic marine environments. Specifically, the baseline planner enforces geometric feasibility, inter-vehicle collision avoidance, and basic kinematic constraints, while not explicitly incorporating probabilistic environmental risk or detailed current-aware optimization into the planning objective.

Such baseline strategies are widely used in practical multi-AUV deployments due to their computational simplicity, robustness, and ease of implementation, particularly in environments where environmental uncertainty is difficult to quantify in real time. Therefore, the selected baseline provides a realistic and practically relevant reference rather than an artificially weakened comparator.

Learning-based approaches such as deep reinforcement learning have shown potential for AUV navigation in complex environments; however, they typically require extensive training data, suffer from limited interpretability, and may generalize poorly to unseen ocean current conditions. In contrast, the proposed framework adopts an engineering-oriented, model-based strategy that emphasizes robustness, transparency, and practical deployability under limited communication and computational resources.

The purpose of the comparison is not to benchmark against all existing planning paradigms, but to isolate and evaluate the impact of explicitly integrating probabilistic environmental risk into cooperative planning. By keeping the underlying cooperative structure and constraints comparable between the two schemes, the observed performance differences can be primarily attributed to the inclusion of risk-aware planning mechanisms.

This comparison strategy allows a focused assessment of how risk inference influences cooperative behavior, energy efficiency, trajectory smoothness, and mission robustness, without conflating the results with differences arising from fundamentally distinct planning architectures.

It is noted that the selected baseline is not intended to represent the full spectrum of state-of-the-art planning algorithms, but rather a commonly adopted engineering-oriented cooperative scheme. The focus of this comparison is to isolate the effect of explicit probabilistic risk integration under otherwise comparable cooperative structures. The baseline scheme is intended to represent a commonly adopted engineering-oriented cooperative planning strategy rather than an exhaustive comparison with all existing state-of-the-art planning paradigms.

5. Results and Discussion

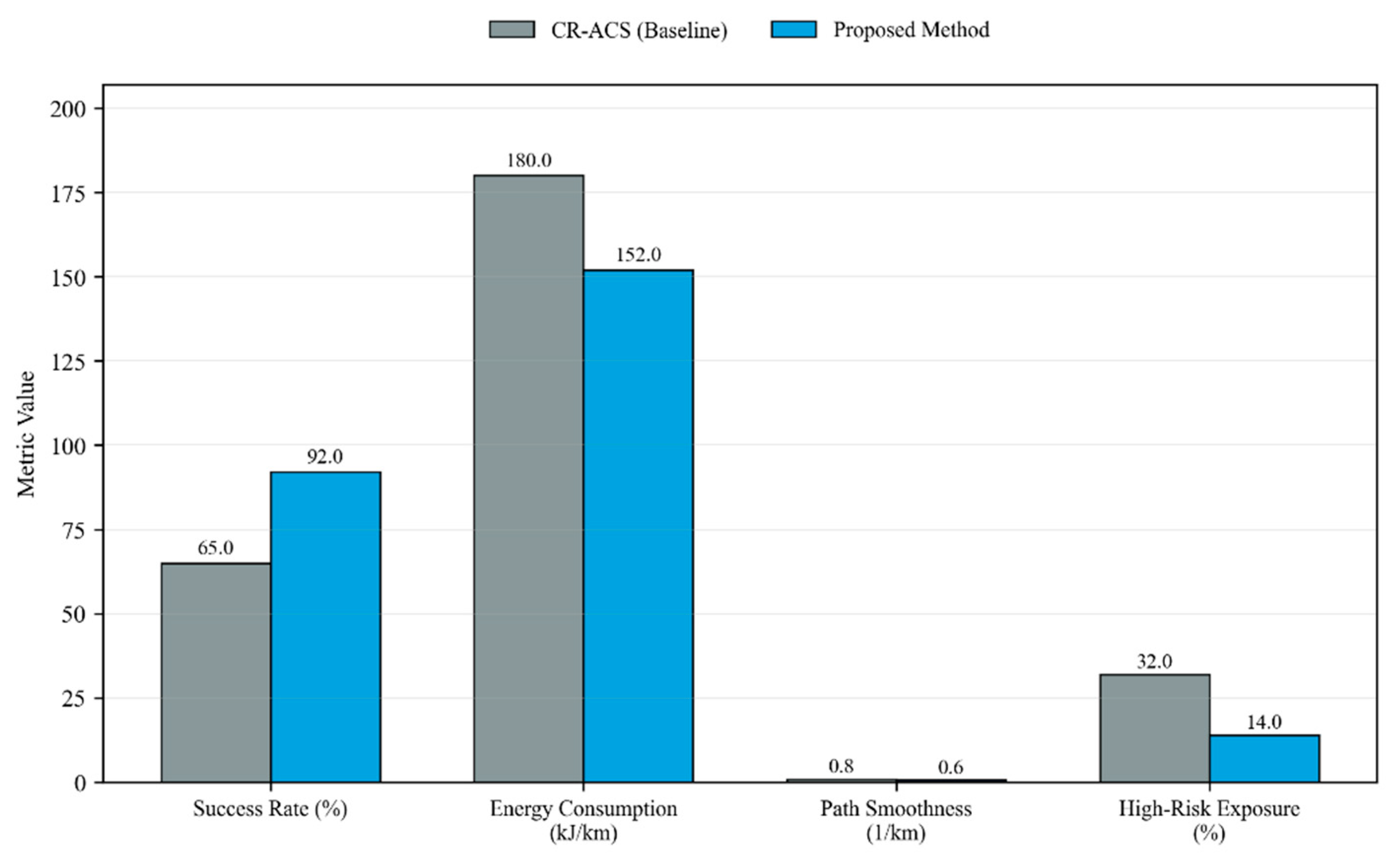

5.1. Overall Cooperative Performance

The overall cooperative performance of the proposed framework is evaluated through large-scale Monte Carlo simulations under heterogeneous canyon environments, and the aggregated results are summarized in

Figure 4. The comparison is conducted against the conventional risk-agnostic cooperative scheme (CR-ACS) using the performance metrics defined in

Section 4.

As shown in

Figure 4, the proposed method achieves a substantially higher mission success rate (SR) than the baseline scheme across all tested scenarios. In most simulation runs, all AUVs successfully reach the target region without violating collision-avoidance constraints or entering prohibited areas. This improvement indicates that explicitly integrating probabilistic environmental risk into cooperative planning significantly enhances mission robustness in complex dynamic marine environments.

Importantly, the increase in success rate is not obtained through overly conservative behavior.

Figure 4 shows that the proposed method simultaneously reduces the energy consumption index (ECI) and path curvature (CurvRMS) relative to CR-ACS. This demonstrates that risk-aware planning guides the AUVs toward dynamically favorable and safer corridors, rather than forcing long detours or excessive maneuvering. By accounting for current structure and terrain-related risk during optimization, unnecessary corrective actions and inefficient path adjustments are avoided.

In addition, the proposed framework yields a markedly lower high-risk exposure ratio (RTrisk) in

Figure 4. This result confirms that AUVs spend significantly less time operating in regions associated with elevated inferred failure probability. The reduction in risk exposure directly reflects the role of the CBN-based risk field as a decision-driving component within the planning loop, rather than as a post hoc evaluation metric.

Overall,

Figure 4 demonstrates that the proposed cooperative planner improves mission reliability, energy efficiency, trajectory smoothness, and safety in a consistent and integrated manner. These results establish a solid performance baseline for the subsequent analysis of risk evolution and engineering robustness.

5.2. Energy Consumption and Path Efficiency

Energy efficiency is a critical consideration for AUV missions due to limited onboard power. The energy consumption index (ECI) is used to quantify the average energy cost per unit distance traveled by the AUV fleet.

Simulation results show that the proposed method achieves lower ECI values compared with the baseline scheme in most cases. By leveraging favorable ocean current directions and avoiding unnecessary detours, the proposed planner generates trajectories that require less propulsion effort. This effect is particularly evident in scenarios with strong along-canyon currents, where the planner guides AUVs to exploit down-current corridors. The observed reduction in energy consumption can be attributed to the planner’s ability to exploit favorable current structures while avoiding high-risk and high-resistance regions. By explicitly accounting for current-induced drift and environmental risk within the optimization process, unnecessary corrective maneuvers and detours are reduced, resulting in more energy-efficient trajectories rather than relying on overly simplified or shortest-path solutions.

In addition to reduced energy consumption, the proposed method also yields shorter effective path lengths. This indicates that the cooperative strategy not only improves safety but also enhances overall path efficiency. From an engineering perspective, these improvements translate into extended operational range and increased mission endurance for multi-AUV systems.

5.3. Path Smoothness and Maneuverability

Path smoothness is evaluated using the root mean square curvature metric, denoted as CurvRMS. Lower CurvRMS values correspond to smoother trajectories with fewer sharp turns, which are more compatible with the maneuvering limitations of practical AUV platforms.

The results show that the proposed method produces smoother paths than the baseline approach. This improvement can be attributed to the cooperative optimization process, which penalizes excessive curvature while balancing safety and efficiency objectives. Smooth trajectories are beneficial for reducing actuator wear, improving tracking accuracy, and enhancing overall navigation stability.

In contrast, the CR-ACS often generates paths with higher curvature when reacting to dynamic obstacles or strong currents, resulting in less predictable vehicle motion. The smoother trajectories obtained using the proposed method are therefore more suitable for real-world deployment in complex marine environments.

These results are consistent with the engineering intuition that smoother and current-aware trajectories reduce both control effort and actuator workload, further supporting the practical applicability of the proposed framework for real-world AUV operations.

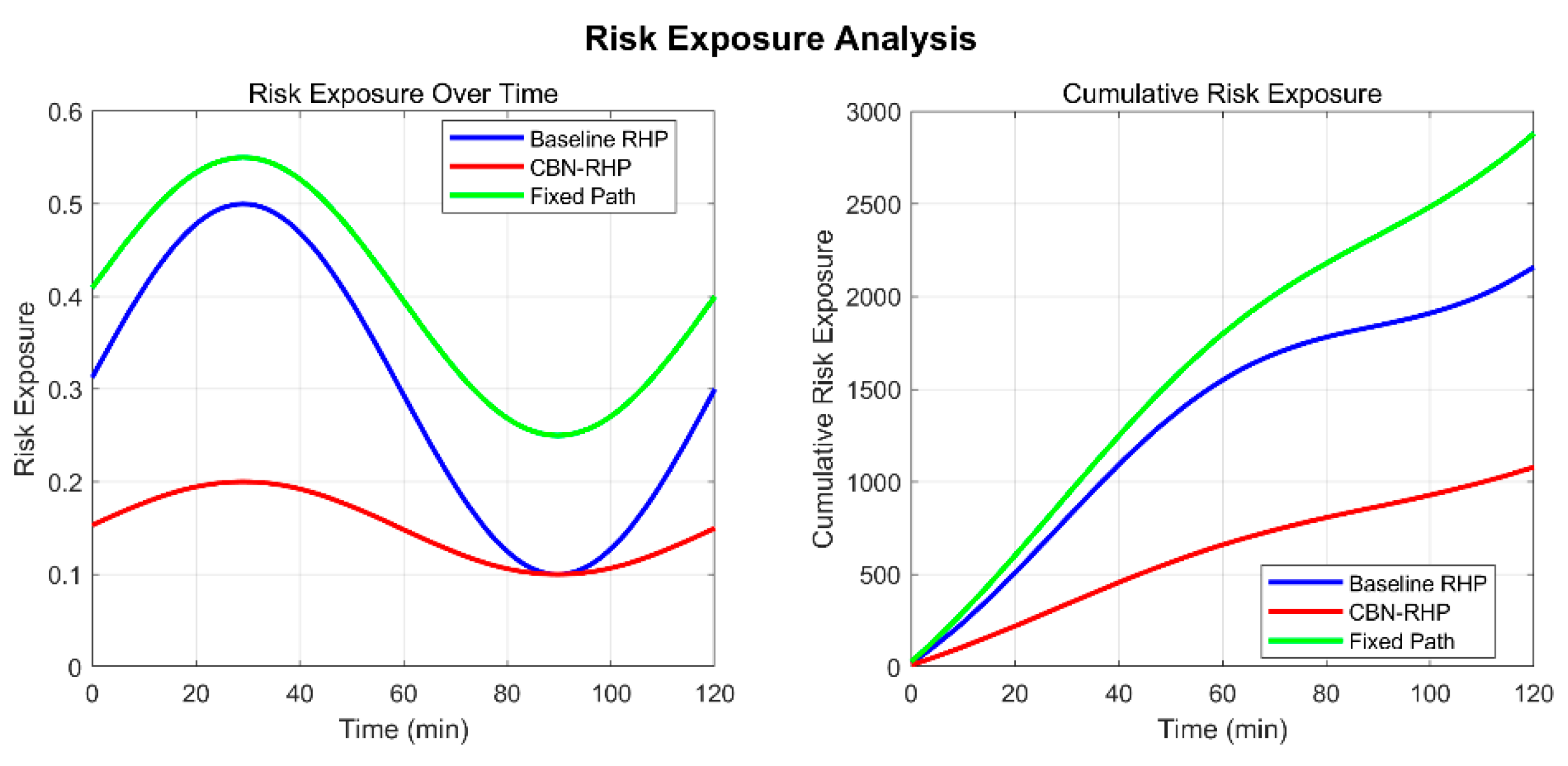

5.4. Risk Exposure Analysis

To further examine how safety improvements are achieved during cooperative planning, the temporal evolution of risk exposure is analyzed using the high-risk exposure ratio RTrisk. This metric quantifies the proportion of mission time during which AUVs operate in regions with elevated inferred failure probability.

Figure 5 reports the risk exposure over mission time for both the baseline and the proposed method, including the time-varying (instantaneous) exposure curve and the cumulative exposure curve. The proposed method consistently maintains a lower instantaneous risk level throughout the mission, rather than reducing risk only at specific stages. In contrast, the baseline scheme exhibits more pronounced increases in risk exposure when trajectories traverse dynamically unfavorable or terrain-constrained regions.

The cumulative exposure curve further confirms this trend. Over the full mission duration, the proposed framework accumulates risk at a significantly slower rate, resulting in substantially lower total risk exposure by the end of the mission. This behavior indicates that risk reduction is achieved proactively and continuously during trajectory generation, rather than relying on a posteriori filtering or late-stage corrections.

The observed reduction in risk exposure can be directly attributed to the integration of the CBN-derived risk field into the cooperative optimization process. By penalizing sustained traversal through hazardous terrain–current–uncertainty combinations, the planner biases trajectory updates toward safer corridors whenever feasible alternatives exist.

Overall,

Figure 5 provides process-level evidence that the proposed planner systematically limits time spent in high-risk regions throughout the mission. This sustained risk suppression explains the improved mission success rates reported in

Section 5.1 and confirms that safety gains arise from consistent risk-aware decision-making rather than isolated avoidance events.

5.5. Planning and Communication Efficiency

The computational and communication efficiency of the cooperative planning framework is assessed using the average planning frequency and communication frequency .

The proposed method exhibits moderate values of , indicating that frequent global replanning is not required to maintain safe and efficient trajectories. This is achieved by incorporating environmental trends and cooperative constraints directly into the planning process, which reduces the need for reactive replanning.

Similarly, the communication frequency remains at an acceptable level, as coordination among AUVs is achieved through limited but effective information exchange. This property is advantageous for practical deployments where acoustic communication bandwidth is constrained and intermittent.

Overall, the balance between planning performance and computational load suggests that the proposed cooperative path planning method is suitable for real-time or near-real-time implementation in multi-AUV systems.

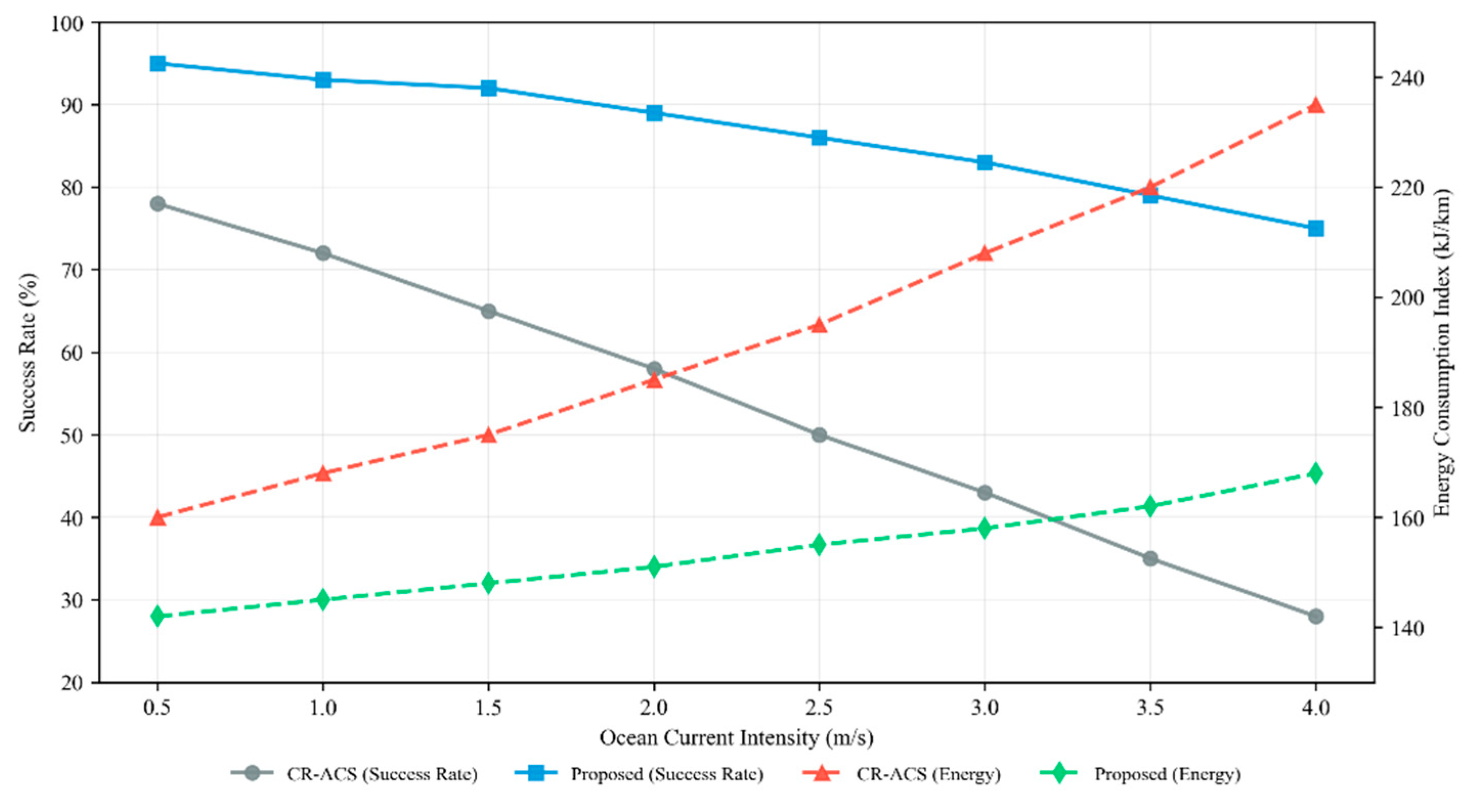

5.6. Engineering Implications

From a marine engineering perspective, the simulation results demonstrate that cooperative path planning strategies which explicitly account for environmental dynamics and probabilistic risk can substantially enhance multi-AUV mission performance. Improvements in success rate, energy efficiency, trajectory smoothness, and safety collectively indicate strong potential for real-world deployment in complex marine environments.

Figure 6 examines the robustness of the proposed framework under increasing ocean current intensity. As current strength increases, the baseline cooperative scheme exhibits a pronounced degradation in mission success rate, accompanied by a rapid rise in energy consumption. This behavior reflects limited ability to anticipate and mitigate the coupled effects of strong currents and terrain constraints.

In contrast, the proposed risk-aware method maintains consistently higher success rates across the tested current intensities, while exhibiting a more moderate increase in energy cost. This indicates that the planner effectively exploits safer and more favorable flow corridors under stronger forcing, thereby reducing mission-critical failures and excessive corrective maneuvers.

These results suggest that the proposed framework provides improved operational margins in adverse flow conditions without requiring frequent global replanning or excessive communication. Such characteristics are particularly advantageous for bandwidth-limited and power-constrained multi-AUV operations, including canyon surveys, seabed inspection, and long-duration environmental monitoring missions.

5.7. Limitations and Applicability of the Proposed Framework

The CBN-based risk model adopted in this study is designed to provide a relative ranking of environmental hazard levels for planning purposes, rather than to predict absolute failure probabilities.

As such, the inferred risk values are scenario-dependent and should be interpreted as decision-support indicators rather than statistically calibrated safety metrics.

First, the conditional Bayesian network (CBN)-based risk model relies on a predefined set of environmental variables and engineering-informed parameterization. While this formulation provides a consistent and interpretable representation of relative environmental risk for planning purposes, the inferred risk values are scenario-dependent and do not represent universally calibrated failure probabilities. As such, the framework is best suited for applications where relative risk ranking and risk-aware decision guidance are more critical than precise probabilistic prediction.

Second, the current implementation adopts a simplified kinematic model of AUV motion and does not explicitly account for higher-order vehicle dynamics, actuator saturation, or hydrodynamic interaction effects. These simplifications are common in cooperative planning studies and are appropriate for evaluating high-level planning behavior. However, for missions requiring aggressive maneuvering or operating near vehicle performance limits, tighter coupling between planning and low-level control may be necessary.

Third, the computational performance of the proposed framework scales approximately linearly with the number of vehicles and discretization resolution. While this enables real-time or near-real-time operation for small to medium-sized AUV teams, further optimization or hierarchical planning strategies may be required for large-scale fleets or highly constrained environments.

Despite these limitations, the proposed framework is well suited for a broad class of engineering-oriented multi-AUV missions, including cooperative seabed surveying, canyon exploration, and environmental monitoring, where environmental uncertainty, ocean current variability, and operational safety are dominant considerations. The modular design of the framework also allows individual components, such as the risk inference model or cooperative coordination strategy, to be extended or replaced as needed for specific application scenarios.

6. Conclusions

This paper has presented a cooperative path planning framework for multiple autonomous underwater vehicles operating in complex dynamic marine environments. By explicitly incorporating time-varying ocean currents, environmental constraints, and inter-vehicle cooperative requirements, the proposed method addresses key challenges encountered in practical multi-AUV missions.

The main conclusions of this study can be summarized as follows.

First, a unified problem formulation for cooperative multi-AUV path planning in dynamic marine environments has been established. The formulation integrates vehicle kinematics, ocean current effects, environmental constraints, and collision-avoidance requirements, providing a consistent foundation for engineering-oriented path planning.

Second, a cooperative planning algorithm has been developed based on discretized trajectory optimization and constraint handling. The algorithm enables multiple AUVs to coordinate their motion effectively while maintaining safe separation distances and avoiding hazardous regions identified by the risk assessment model.

Third, numerical simulations conducted in a realistic canyon environment demonstrate that the proposed method improves mission robustness and efficiency. Compared with a baseline cooperative planning scheme, the proposed approach achieves higher success rates, lower energy consumption indices, smoother trajectories, and reduced exposure to high-risk regions, as quantified by metrics such as ECI, CurvRMS, and .

Finally, the computational and communication characteristics of the proposed framework indicate that it is suitable for real-time or near-real-time implementation in practical marine engineering applications. The moderate planning frequency and communication frequency suggest that the method can be deployed in bandwidth-limited and power-constrained multi-AUV systems.

Overall, the results demonstrate that incorporating environmental dynamics and cooperative risk-aware strategies into multi-AUV path planning can significantly enhance operational performance and safety in complex marine environments. These findings highlight the practical value of integrating probabilistic environmental risk into cooperative AUV planning for real-world marine engineering applications.

7. Future Work

Although the proposed cooperative path planning framework has shown promising performance in numerical simulations, several aspects warrant further investigation.

Future work will focus on extending the framework to account for more complex vehicle dynamics, including vehicle inertia and control constraints. In addition, incorporating uncertainty-aware planning and adaptive risk modeling based on real-time sensor feedback may further improve robustness in highly uncertain marine environments.

Another important direction is the experimental validation of the proposed method using sea trials or hardware-in-the-loop simulations. In addition, learning-based multi-agent coordination (e.g., Shapley-value-based credit assignment in multi-agent Q-learning) could be incorporated to enhance cooperative decision-making.[

14] Such studies would provide valuable insights into real-world performance and facilitate the transition of the proposed framework from simulation to operational deployment.

References

- Zhuang, Y.; Huang, H.; et al. Cooperative path planning of multiple autonomous underwater vehicles operating in dynamic ocean environment. ISA Transactions 2019, Volume 94, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chassignet, E. P.; Hurlburt, H. E.; Smedstad, O. M.; et al. The HYCOM (Hybrid Coordinate Ocean Model) data assimilative system. Journal of Marine Systems 2007, 65, 60–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Liu, Y.; Sun, B. Task assignment and path planning of a multi-AUV system based on a Glasius bio-inspired self-organising map algorithm. Journal of Navigation 2018, 71, 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Z.; Wang, F.; Lei, T.; Luo, C. Path Planning Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Underwater Vehicles Under Ocean Current Disturbance. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2023, 8, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasius, R.; Komoda, A.; Gielen, S. C. A. M. Neural network dynamics for path planning and obstacle avoidance. Neural Networks 1995, 8, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossen, T. I. Handbook of Marine Craft Hydrodynamics and Motion Control; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elidan, G. Copula Bayesian networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; Volume 23, NIPS 2010, pp. 559–567. [Google Scholar]

- GEBCO Compilation Group. GEBCO 2024 Grid. In General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans; 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, L.; Huang, B.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, C. Erosional and depositional features along the axis of a canyon in the northern South China Sea and their implications: Insights from high-resolution AUV-based geophysical data. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2024, 12, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Li, T.; Sun, M.; et al. Erosional and depositional features along the axis of a canyon in the northern South China Sea and their implications. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 2016, 116, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; et al. Analysis of mooring-observed bottom current on the northern continental shelf of the South China Sea. Frontiers in Marine Science 2023, 10, 1164790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, C.; et al. Along-slope bottom current and sediment resuspension and transport induced by internal tides on a continental slope in the northeastern South China Sea. Journal of Physical Oceanography 2024, 54, 2311–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. REMUS Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. Online resource.

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, T.-K.; Gu, Y. SHAQ: Incorporating Shapley value theory into multi-agent Q-learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022); Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 27985–27998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).