1. Introduction

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) are mostly used by scientists and researchers to map the sea collect information on the sea bed, and its environment, and identify hazards (Cochran et al, 2019). Autonomous underwater vehicles provide better autonomy than Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROV) as they cut off the umbilical cord tether which is used as a means of human-robot interaction for communication (Giodini et al, 2023). While Human-Robot Interaction (HRI) for ROVs is defined with a tethering system, there is still ongoing research on HRI, even as it relates to decision-making for AUVs (Birk, 2022). This is the basis for our argument for better decision-making for autonomous underwater vehicles. There has been multiple research on autonomous underwater vehicles and their applications in the advancement of deep-sea research such as habitat mapping in deep and shallow water (Russell, 2014). However, this research mostly focuses on the use of autonomous underwater vehicles, with little thought on how AUVs make decisions that keep them on their route as they execute their tasks. To understand how AUVs make decisions, they need to first perceive their environment, make decisions, and then actuate movement.

Planning decision-making for underwater autonomous vehicles is difficult as we have to factor in how diverse the underwater environment can be. This is because the underwater robot needs to be aware and versed with its environment. Hence, it is necessary to make decisions by evaluating the current conditions at sea and anticipating future conditions from the evaluation. This is what makes an autonomous underwater vehicle intelligent and trustworthy.

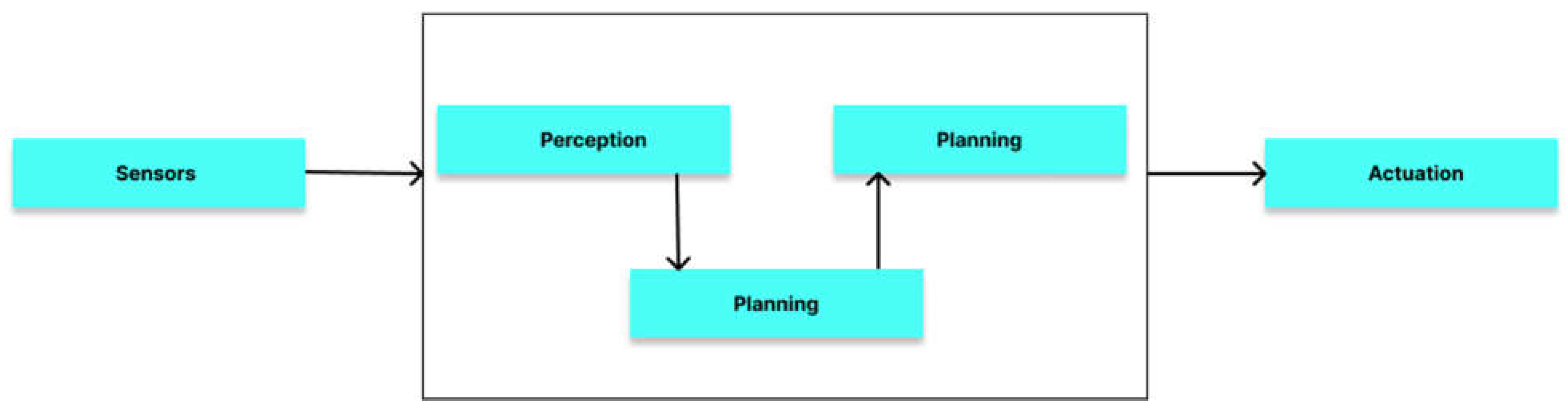

Figure 1.

Autonomous system overview.

Figure 1.

Autonomous system overview.

1.1. Perception

This is the first stage that all autonomous robots must go through. According to Premediba et al. (2018), this involves the use of sensory data and artificial intelligence to empower robots to learn about their environment and comprehend events. This is just like humans, where we use our eyes to be well-versed in the environment (Brummelen, 2018). With perception, robots can determine how far the next object is from them. Perception algorithm needs to be correct as an impaired perception may cause visual and motion dysfunction (Benli, 2019).

1.2. Decision Making

Planning is the next step after perception. In this stage, the algorithm utilizes the data provided in the perception stage to provide a collision-free path for the robot to reach its destination (Mohamed et al, 2024). This is the process of decision-making or path planning. For autonomous underwater vehicles, we have to account for external factors such as wind and tide when incorporating path planning (Binney, 2010).

1.3. Motion Actuation

Control or motion actuation is the final step in the robot process. After getting a visual representation of their environment and deciding the route to follow, this process is in charge of translating this into motion (Xianbo, 2015).

2. Perception Overview in AUVs

Perception of automated underwater vehicles has been researched and improved over time since the Special Purpose Underwater Research Vehicle (SPURV) the first AUV was developed in 1957 at the Applied Physics Laboratory of the University of Washington (SPURV, n.d). Perception uses sensors positioned at various parts of the vehicle to collect and analyze data about its surroundings. With increased research in the area of perception in autonomous underwater vehicles, researchers can now benefit from data presented by AUVs such as the MIT Sea Grant Marine Perception Dataset (MIT Sea Grant, 2021). There are also firms making commercial software to aid perception in autonomous underwater vehicles such as AutoTrap Onboard produced by Charles River Analytics (Pfautz, 2022). This has seen the use of more detailed imaging sensors for perception such as high-frequency sonars and electro-optics which is quite different from the traditional optical vision used (Pailhas, 2010) (Massot-Campos, 2015).

This research paper by Rosique et al (2018), shows the trade-off between resolution and distance to be considered when choosing between sonar and optical vision as a means of perception. Hence, the improvement of sonars for higher-resolution images, shows that researchers are tilting towards this distance trade-off with sonars for its ability to capture high-resolution images at a short range (Pailhas, 2010). It is important to note that these perception devices and software are accompanied by a perception algorithm. For instance, the VAN framework by the University of Michigan uses visual perception to augment the navigation capabilities of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUV) (Eustice, 2008). These algorithms usually incorporate a perception (real-time) map to determine the location of the vehicle and aid decision-making (Li et al, 2021). This is an improvement from the SPRUV deployed in 1975, which used acoustic signals from the accompanying research vessel as a guide to move below the water’s surface.

2.1. Path Planning in AUVs

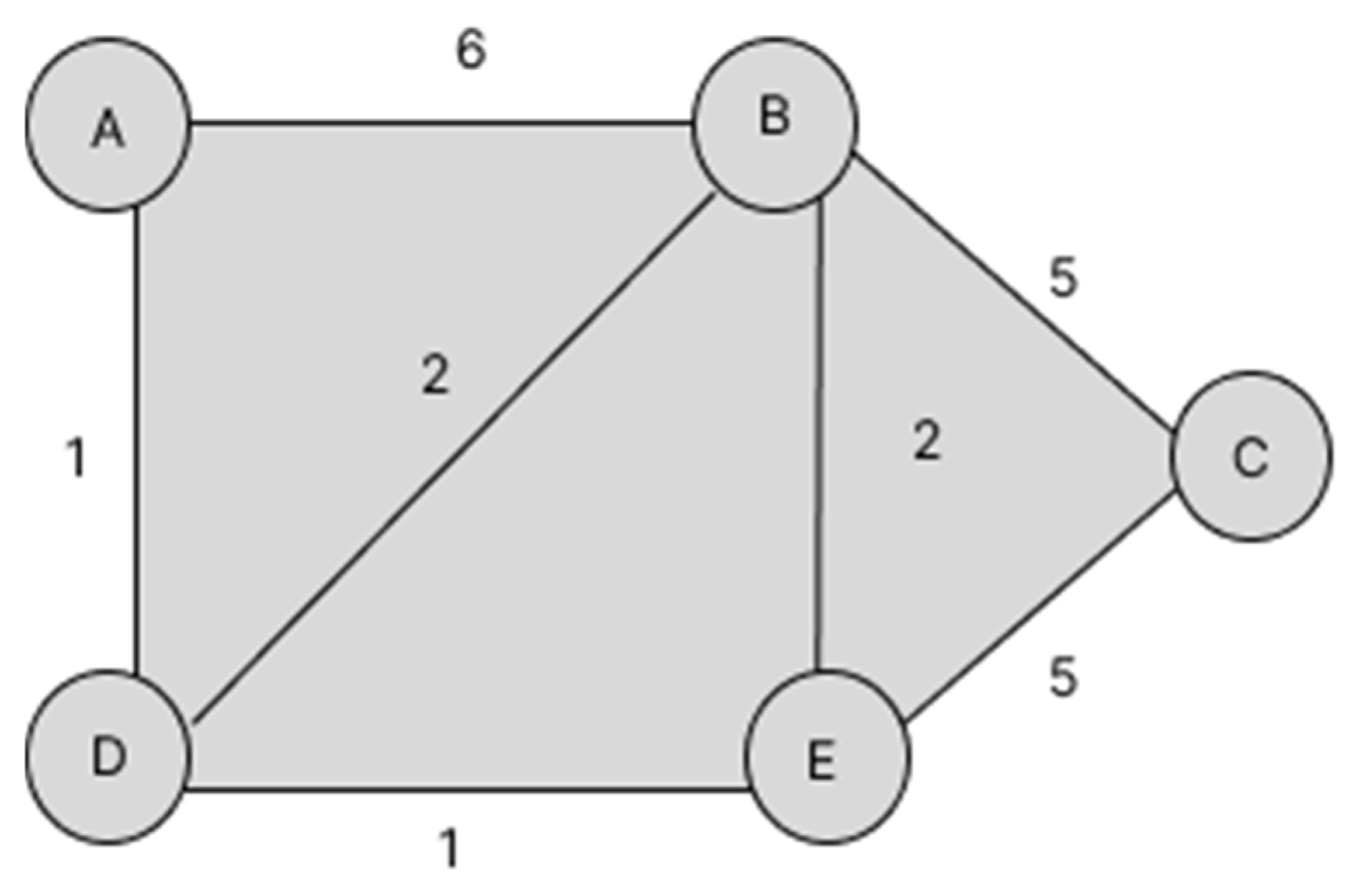

There has been a lot of research on different algorithms for better path planning for autonomous vehicles. For instance, this paper focuses on the use of a visibility binary tree algorithm to plan the path of the robot. Binary trees have mostly been used as a data structure for decision-making, sorting data, and searching for information quickly. This paper shows the complete construction of all paths between the robot and the destination. Next, this path is used to create a visibility binary tree where we run the algorithm for the shortest path without an obstacle. Ashraf et al. (2021), also show the use of a decision tree for decision-making in the initial and final positions. With the use of a heuristic, the A* algorithm can successfully plan the paths with the shortest route. However, the problem with this algorithm is that it can take a lot of time and cost much. For instance, when the initial goal node is reached, the path can be reconstructed while ensuring that the path cost is not over-estimated. Also, A* is expensive and memory-intensive to execute as it keeps track of all generated nodes.

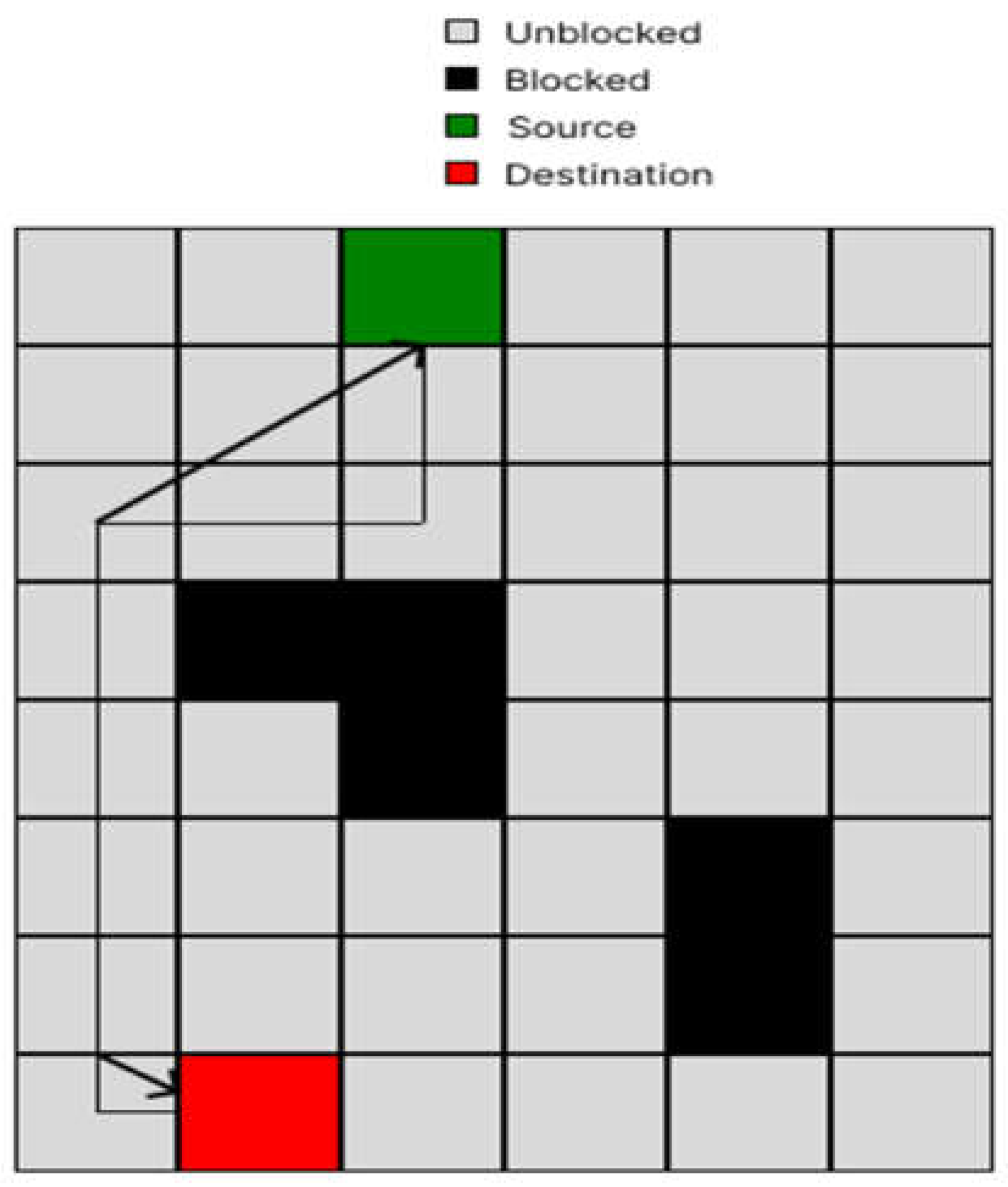

Figure 2.

Rapidly Exploring Random Tree (RRT).

Figure 2.

Rapidly Exploring Random Tree (RRT).

However, for autonomous underwater vehicles, it is a bit different to plan the path of the vehicle by considering only external objects and obstacles because considerations are also given to external environmental factors. Hence, this path-planning research paper focuses on the use of a modified rapidly exploring random tree(RRT) for path-planning autonomous underwater vehicles. RRTs are particularly useful in high-dimensional spaces where traditional search methods won’t work, making them a better solution than binary search trees (Xu, 2024).

However, the use of standard RRTs has been shown to lack the ability to guarantee optimal paths. For instance, RRTs don’t consider the shortest path when planning the path of autonomous vehicles (Huang & Ma, 2022). This is because, the random sampling that RRTs provide isn’t optimized to take into account, the shortest path. Hence, the first point only points to the nearest existing node so that the tree grows exponentially to avoid obstacles.

Next, RRTs is improved to address the optimality that they lack by creating an RRT extension known as RRT star (RRT*) (Tu et al. 2023). According to Kiani et al. (2021), this optimized version of RRT creates the shortest path to the destination by enhancing its node. RRT* uses a cost-to-come metric for each node, ensuring that the new nodes minimize the path cost.

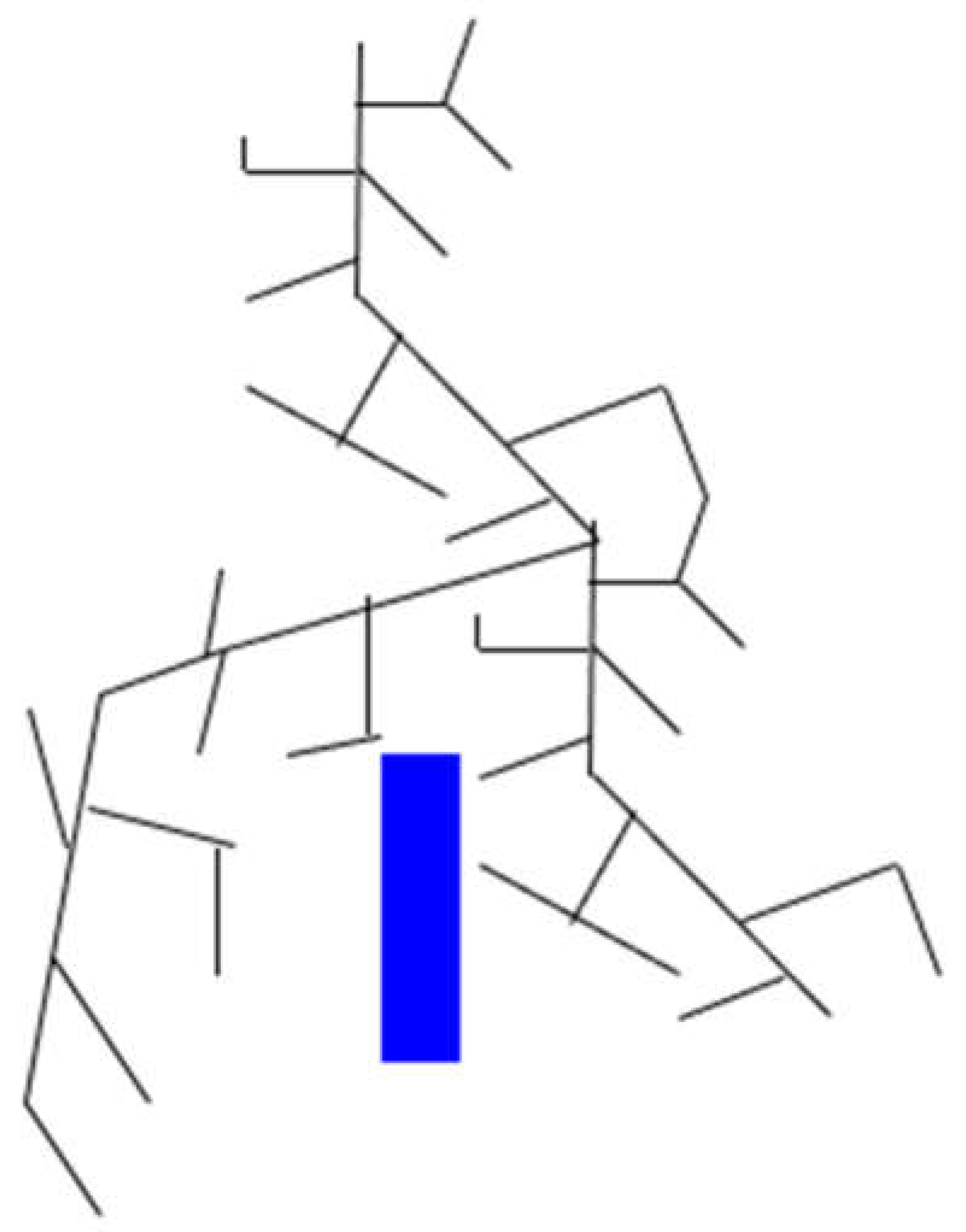

Another algorithm with wide usage in path planning that has been researched fully is the star (A*) algorithm (Foead et al., 2021) (Pokorny & Vincent, 2013) (Zuoyu & Xinduo, 2024). This algorithm is also focused on finding the shortest path between the source node (start point) and the goal node (destination point). Dijkstra's algorithm is another algorithm that is useful for path planning in autonomous vehicles. This algorithm is useful for finding the shortest path from one vertex to another vertex. This has been used in GPS for locating the distance between the vehicle and the destination, and other devices (Hsu, 2022). Dijkstra's algorithm makes this possible by visiting the nearest unvisited vertex. According to Candra et al. (2020), Dijkstra can handle the shortest path search giving optimal results in a longer search time.

Figure 4.

Dijkstra's Algorithm.

Figure 4.

Dijkstra's Algorithm.

2.2. AUV Motion Actuation

Motion actuation in autonomous underwater vehicles usually depends on their degree of freedom (DOF) as it relates to their actuators (Qin & Sun, 2019). For instance, in partially actuated AUVs, the AUV controls only a subset of their degree of freedom, while relying on the water dynamics to manage the others. Whereas, the fully actuated AUVs have total control of their DOF. This simply means that fully actuated AUVs have enough actuators to control their DOF whereas partially actuated AUVs have fewer actuators controlling their DOF (Xiang et al, 2016).

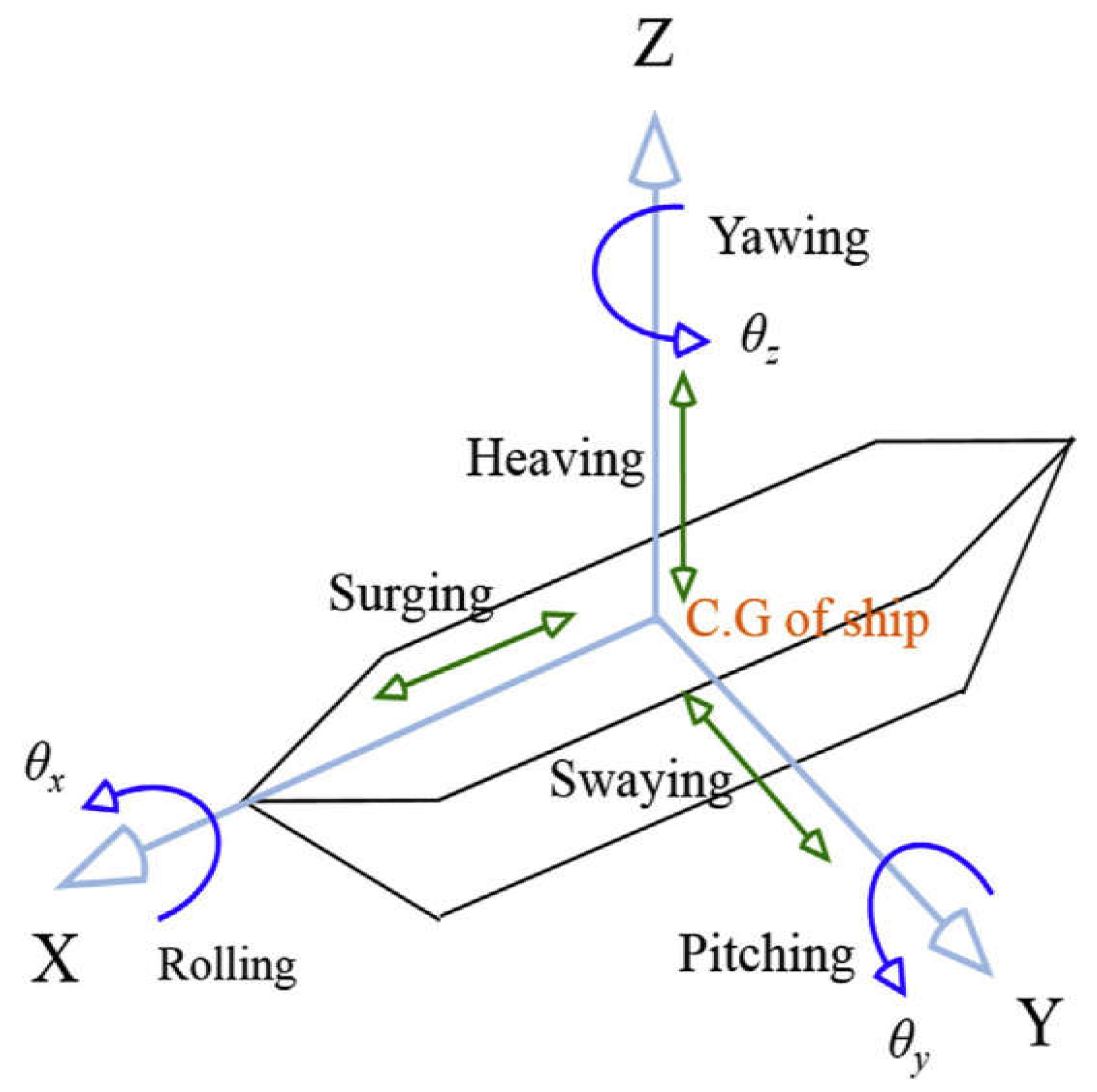

In marine engineering design, there are six degrees of freedom such as roll, pitch, yaw, heave, surge, and sway.

Figure 5.

Six Degrees of Motion.

Figure 5.

Six Degrees of Motion.

From the image above, the motions are divided into rotational and translational motions, each relating to the x, y, or z axis.

Table 1.

Six Degrees of Motions.

Table 1.

Six Degrees of Motions.

| Rotational Motion |

|

| Roll |

Side-by-side tilting motion along the x-axis. |

| Pitch |

Up-and-down motion along the x-axis. |

| Yaw |

Turning rotation along its vertical/Z axis. |

| Translational Motions |

|

| Heave |

Up-and-down motion along the y-axis |

| Surge |

Linear longitudinal front/back motion. |

| Sway |

Linear transverse Side-by-side |

Sometimes, autonomous vehicles are built in such a way that they have actuators designed for all of these motions. In other vehicles, their physical structure is streamlined in such a way that they can handle some form of motion in relation to the water body, without an actuator.

Since we understand the six degrees of freedom or the motions a vessel can make, it is important to understand actuation in AUVs. The following methods can be employed for motion actuation in an AUV:

2.2.1. Thrusters

Thrusters are usually electric or hydraulic motors driving propellers to generate thrust. The thrust produced allows the vehicle to move in different directions. They are the primary means of propulsion and maneuvering in AUVs. According to Chen and Liu, they are the most common form of propulsion for AUVs (Chen et al, 2020). Thrusters are mounted on various parts of the vehicle to provide forward, backward, literal movement, and depth control. Body thrusters in AUVs can be used for maneuvering at high speed and low speed. This is because thrusters offer quick adjustments and better maneuverability than other actuation methods (Karkori, 2024) (Myung & Kim, 2015). Also, at low speeds or in rough environments, thrusters provide more precise and versatile movement control (Bertram, 2011). With all of these advantages, it is important to note that multiple thrusters in an autonomous vehicle can increase the complexity of the design.

2.2.2. Control Surfaces

Rudders, fins, elevators, and other components that control the motion of the ship through hydrodynamic lift and drag forces are known as control surfaces (Rawson & Tupper, 2000). This is because they are used for steering and stabilizing the vehicle. However, control surfaces are effective at higher speeds and are mostly used in conjunction with thrusters for better maneuvering (Kiselev et al, 2022). Control surfaces rely on hydrodynamics and not continuous power, making them an effective choice for less power consumption.

2.2.3. Ballast Systems

The ballast system controls the level of air or water in the tanks of the vehicle, changing its buoyancy. This allows the vehicle to ascend, descend, or maintain a specific depth (Olsen & Rossi, 2024). Unlike other actuation methods, the ballast systems are quieter as they don’t require constant energy and propulsion. However, there needs to be a clear thought-out process in designing the internal sections of the AUV to accommodate the water and air tanks (Alam et al, 2014).

2.2.4. Movable Masses

This type of actuation involves moving the internal components of the vehicle to change the center of gravity, which will in turn affect the vehicle’s pitch or roll. According to Barrass, there is a relationship between ship stability and ship motion. Hence, movable masses can alter stability as well as ship motion.

3. Conclusion

This work exposes the decision-making process of autonomous underwater vehicles. Hence, we have explored current research on perception, decision-making, and motion actuation. Although autonomous underwater vehicles still need a lot of work to gain better trust and function optimally, there’s no doubt that a lot of progress has happened in recent times. Therefore, we see improvements in perception visualization tools, decision-making algorithms, and actuators for motion.

References

- Cochran, J., Bokuniewicz, J., & Yager, L. (2019). Encyclopedia of Ocean Sciences (3rd ed.). Academic Press.

- Giodini, S., Van Der Spek, E., & Dol, H. (2023, July 3). Underwater communications and the level of autonomy of AUVs. Hydro International. https://www.hydro-international.com/content/article/underwater-communications-and-the-level-of-autonomy-of-auvs.

- Birk, A. (2022). A Survey of Underwater Human-Robot Interaction (U-HRI). Curr Robot Rep 3, 199–211. [CrossRef]

- Russell B., Veerle A., Timothy P., Bramley J., Douglas P., Brian J., Henry A., Kirsty J., Jeffrey P., Daniel R., Esther J., Stephen E., Robert M., & James E. (2014). Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs): Their past, present and future contributions to the advancement of marine geoscience, Marine Geology, Volume 352, 2014, Pages 451-468, ISSN 0025-3227. [CrossRef]

- Premebida, C., Ambrus, R., & Marton, Z. (2018). Intelligent Robotic Perception Systems. [CrossRef]

- Brummelen, J., O’Brien, M., Gruyer, D., & Najjaran, H., (2018) Autonomous vehicle perception:.

- The technology of today and tomorrow, Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, Volume 89, 2018, Pages 384-406, ISSN 0968-090X. [CrossRef]

- Benli, E., Motai, Y., & Rogers, J. (2019). Visual Perception for Multiple Human-Robot Interaction From Motion Behavior. IEEE Systems Journal. PP. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, R., Ahmed, O., Amira Y., & Ali G., (2024). Path planning algorithms in the autonomous driving system: A comprehensive review, Robotics and Autonomous Systems, Volume 174, 2024, 104630, ISSN 0921-8890. [CrossRef]

- Binney, J., Krause, A., & Sukhatme, G. (2010). Informative Path Planning for an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. 4791-4796. [CrossRef]

- Xianbo, X., Lionel, L., & Bruno, J., (2015). Smooth transition of AUV motion control: From fully-actuated to under-actuated configuration, Robotics and Autonomous Systems, Volume 67, 2015, Pages 14-22, ISSN 0921-8890. [CrossRef]

- Special Purpose Underwater Research Vehicle (SPURV). (n.d.). http://www.navaldrones.com/SPURV.html.

- MIT Sea Grant. (2021, January 14). AUV Lab - Datasets - Marine Perception - Overview - MIT Sea Grant. https://seagrant.mit.edu/auvlab-datasets-marine-perception-1/.

- Pfautz, K. (2022, May 13). The Journey to Helping AUVs Think: How Marine Roboticists are Turning AUV Sight into Perception. Charles River Analytics. https://cra.com/the-journey-to-helping-auvs-think-how-marine-roboticists-are-turning-auv-sight-into-perception/.

- Pailhas, Y., Petillot, Y., & Capus, C. (2010). High-Resolution Sonars: What Resolution Do We Need for Target Recognition? EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing, 2010(1), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Massot-Campos, M., & Oliver-Codina, G.(2015). Optical Sensors and Methods for Underwater 3D Reconstruction. Sensors, 15(12), 31525-31557. [CrossRef]

- Pailhas, Yan & Petillot, Yvan & Capus, Chris. (2010). High-Resolution Sonars: What Resolution Do We Need for Target Recognition? EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Rosique, F., Navarro, P. J., Fernández, C., & Padilla, A. (2018). A Systematic Review of Perception System and Simulators for Autonomous Vehicles Research. Sensors, 19(3), 648. [CrossRef]

- Eustice, R., Brown, H., & Kim, A. (2008). "An overview of AUV algorithms research and testbed at the University of Michigan," IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles, Woods Hole, MA, USA, 2008, pp. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Zhai, X., Xu, J., & Li, C. (2021). Target Search Algorithm for AUV Based on Real-Time Perception Maps in Unknown Environment. Machines, 9(8), 147. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M., Dey, K., Mishra, S., & Rahman, M. (2021). Extracting rules from autonomous vehicle-involved crashes by applying decision tree and association rule methods. Transportation Research Record, 2675 (11), 522-533. [CrossRef]

- Xu, T. (2024). Recent advances in Rapidly-exploring random tree: A review. Heliyon, 10(11), e32451. [CrossRef]

- Huang, G., & Ma, Q (2022). Research on Path Planning Algorithm of Autonomous Vehicles Based on Improved RRT Algorithm. Int. J. ITS Res. 20, 170–180. [CrossRef]

- Tu, H., Deng, Y., Li, Q., Song, M., & Zheng, X. (2023). Improved RRT global path planning algorithm based on Bridge Test. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 171, 104570. [CrossRef]

- Kiani, F., Seyyedabbasi, A., Aliyev, R. et al (2021). Adapted-RRT: novel hybrid method to solve three-dimensional path planning problems using sampling and metaheuristic-based algorithms. Neural Comput & Applic 33, 15569–15599. [CrossRef]

- Foead, D., Ghifari, A., Kusuma, M., Hanafiah, N., & Gunawan, E. (2021). A Systematic Literature Review of A* Pathfinding. Procedia Computer Science. 179. 507-514. [CrossRef]

- Pokorny, K., & Vincent, R. (2013). Multiple constraint satisfaction problems using the A-star (A*) search algorithm: classroom scheduling with preferences. Journal of Computing Sciences in Colleges. 28. 152-159.

- Zuoyu W., & Xinduo F. (2024). A systematic review and analysis of A-star pathfinding algorithms and their variations, Proc. SPIE 13077, Fourth International Conference on Signal Processing and Machine Learning (CONF-SPML 2024), 130770J. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, R. (2022). Find the shortest path: Algorithm behind GPS - Ray’s Data Science Home - Medium. Medium. https://medium.com/datascienceray/find-the-shortest-path-algorithm-behind-gps-588a1c3dd6d6.

- Candra, A., Budiman M., & Hartanto, K. (2020). "Dijkstra's and A-Star in Finding the Shortest Path: a Tutorial," 2020 International Conference on Data Science, Artificial Intelligence, and Business Analytics (DATABIA), Medan, Indonesia, 2020, pp. 28-32. [CrossRef]

- Qin, H., & Sun, Y. (2019). Autonomous control of underwater offshore vehicles. Fundamental Design and Automation Technologies in Offshore Robotics, 115-160. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X., Yu, C., Zhang, Q., & Xu, G. (2016). Path-Following Control of an AUV: Fully Actuated Versus Under-actuated Configuration. Marine Technology Society Journal. 50. 34-47. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. & Liu, K. (2020). AUV/ROV/HOV Propulsion System. In: Cui, W., Fu, S., Hu, Z. (eds) Encyclopedia of Ocean Engineering. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Karkori, F. (2024). Thruster System Design. In: Dynamic Positioning Systems. Springer Series on Naval Architecture, Marine Engineering, Shipbuilding, and Shipping, vol 21. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. J., & Myung, H. (2015). Autonomous Underwater Vehicles: Design and Practice. CRC Press.

- Bertram, V. (2011). Ship Maneuvering. Practical Ship Hydrodynamics (Second Edition), 241-298. [CrossRef]

- Rawson, K., & Tupper, E. (2000). Structural design and analysis. Basic Ship Theory (Fifth Edition), 237-285. [CrossRef]

- Kiselev, M., Levitsky, S. & Shkurin, M. (2022). Influence of control system algorithms on the maneuvering characteristics of the aircraft. AS 5, 123–130. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, A., & Rossi Ciampolini, P. (2024). Ballast Water Management System Infrastructure. In: Ballast Water Treatment and Exchange for Ships. Synthesis Lectures on Ocean Systems Engineering. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Alam, K., Ray, T., & Anavatti, S. G. (2014). Design and construction of an autonomous underwater vehicle. Neurocomputing, 142, 16-29. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).