Submitted:

11 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characteristics of Sampling Sites

| Country | Climate on yearly basis Rainfall in mm (temperature) |

Horse breed | Type of horse (number) | Number of farms / duration in years | Anthelmintic treatments |

Anthelminticefficacy(%) | Percentage of cyathostomins |

| Poland (South-East part) |

680 (8.7°C°) | Pure blood Arabian, Thoroughbred | Racing (12450 altogether) |

74(10) | Pyrantel, FenbendazoleIvermectin Moxidectin |

51* 23 67 100 |

99 |

| France-1 | 689 (11.8°C) | Welsh poney | Leisure (100x 10 sampling events) |

1 (3) | Ivermectin, Moxidectin Pyrantel |

90 100 90 |

98 |

| France-2 | 579 (14.8°C° | Diverse | Riding club (35x ‘4 sampling events) |

1 (0.5) | Ivermectin, Mebendazole |

96 76 |

nd |

| France-3 | 1237 (10.8°C) | Selle Français, Anglo-Arab | Racing (160x 6 sampling events) |

1 (2) | Ivermectin, Pyrantel Fenbendazole |

96 97 55 |

95 |

| Mexico-1 | 1240 (25.0°C) | American Quarter | Racing (42x4 sampling events) |

1 (0.25) | Ivermectin, Moxidectin, Febantel | 99 90 97 |

64 |

| Mexico-2 | 490 (24.0 °C) | American Quarter | Racing (54x4 sampling events) |

1 (0.25) | Ivermectin, Moxidectin, Febantel | 99 98 90 |

50 |

| Mexico 3 | 426 (22.5 °C) | American Quarter | Racing (71x4 sampling events) |

1 (0.25) | Ivermectin, Moxidectin, Febantel and Metrifonate | 100 100 93 |

30 |

| Mexico 4 | 747 (26.5 °C) | Raza Española | Racing (99 x4 sampling events) |

1 (0.25) | Ivermectin, Moxidectin, Febantel and Metrifonate | 100 100 100 |

65 |

2.2. Parasitological Methods

2.3. Statistical Methods

3. Results

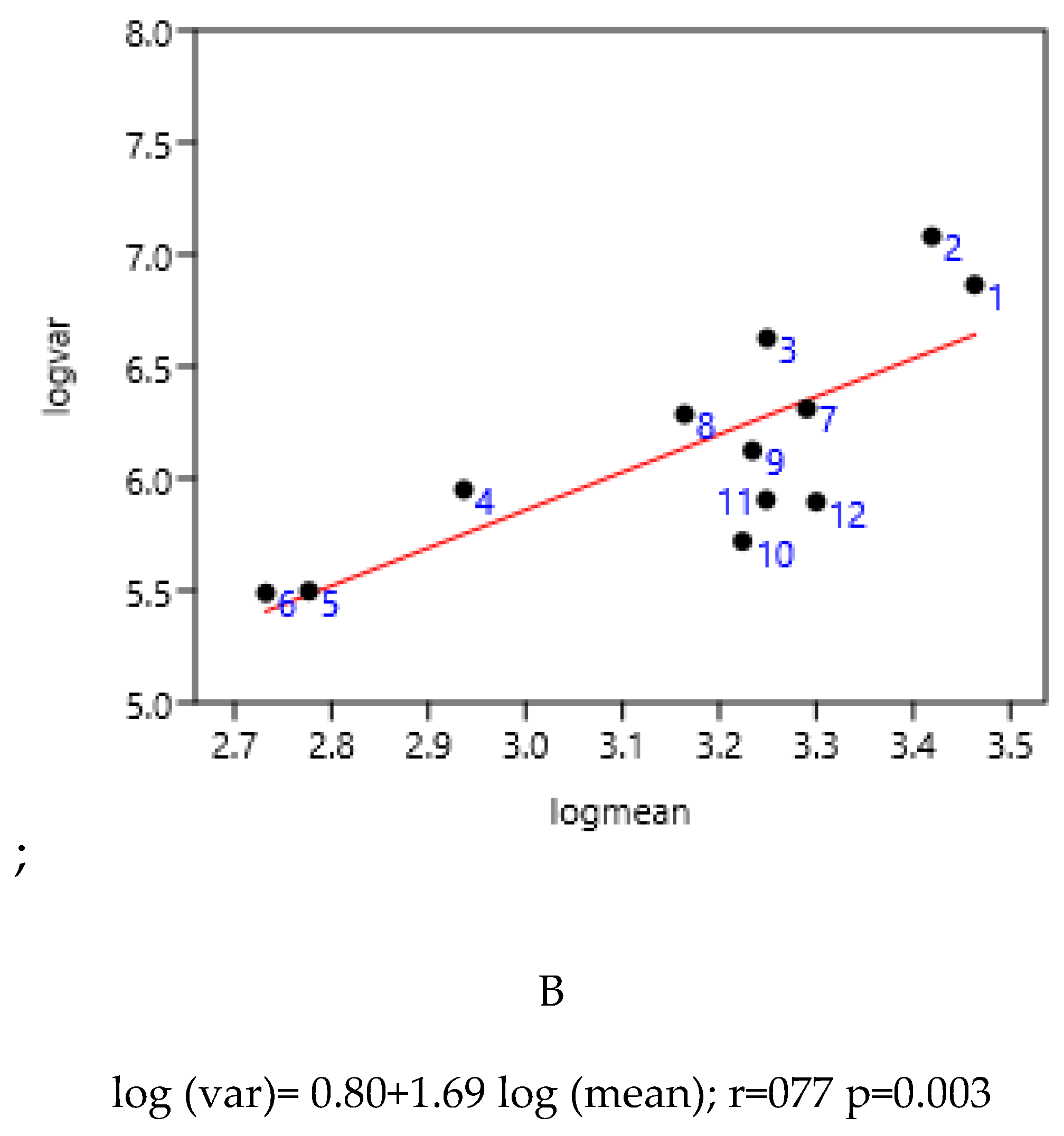

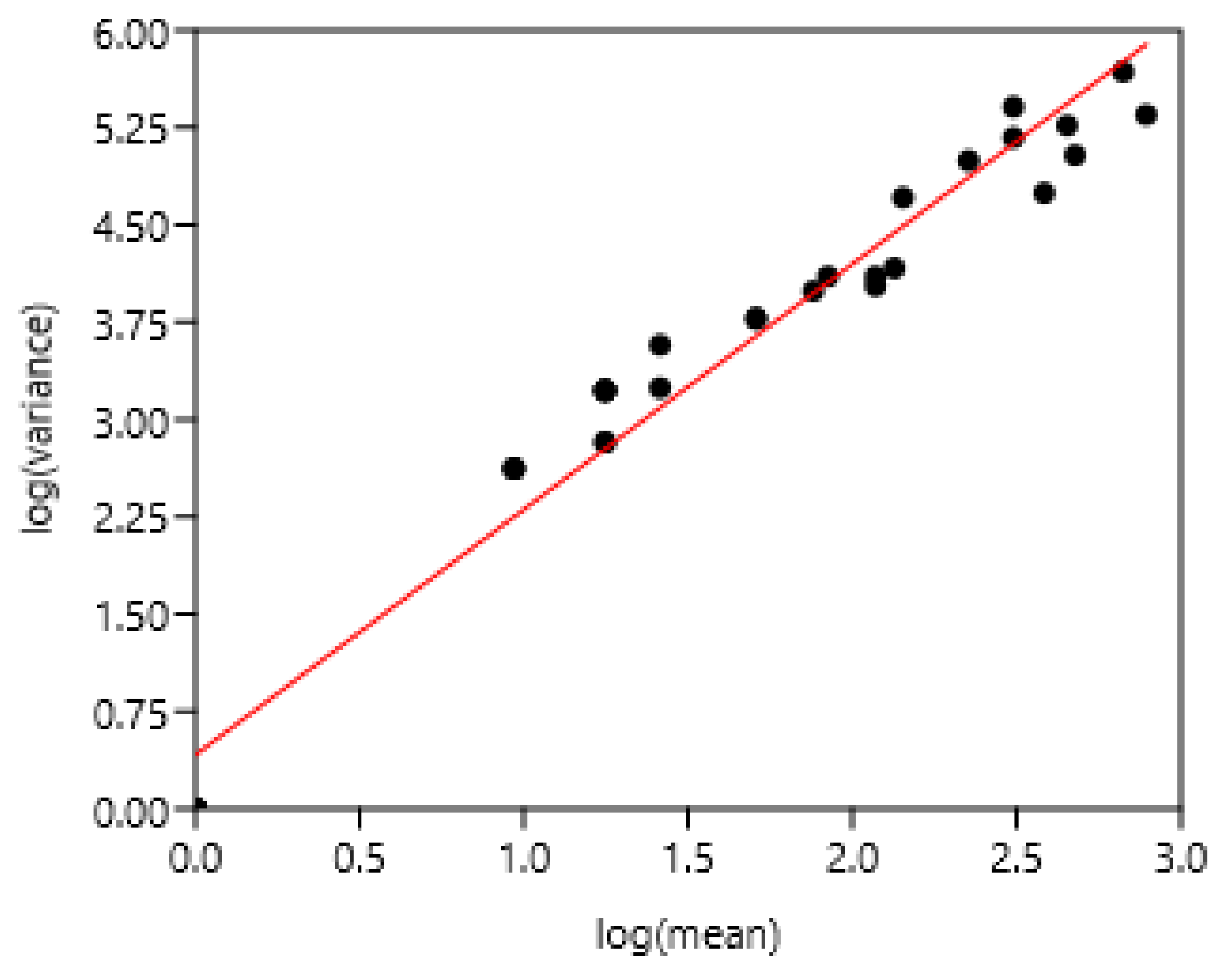

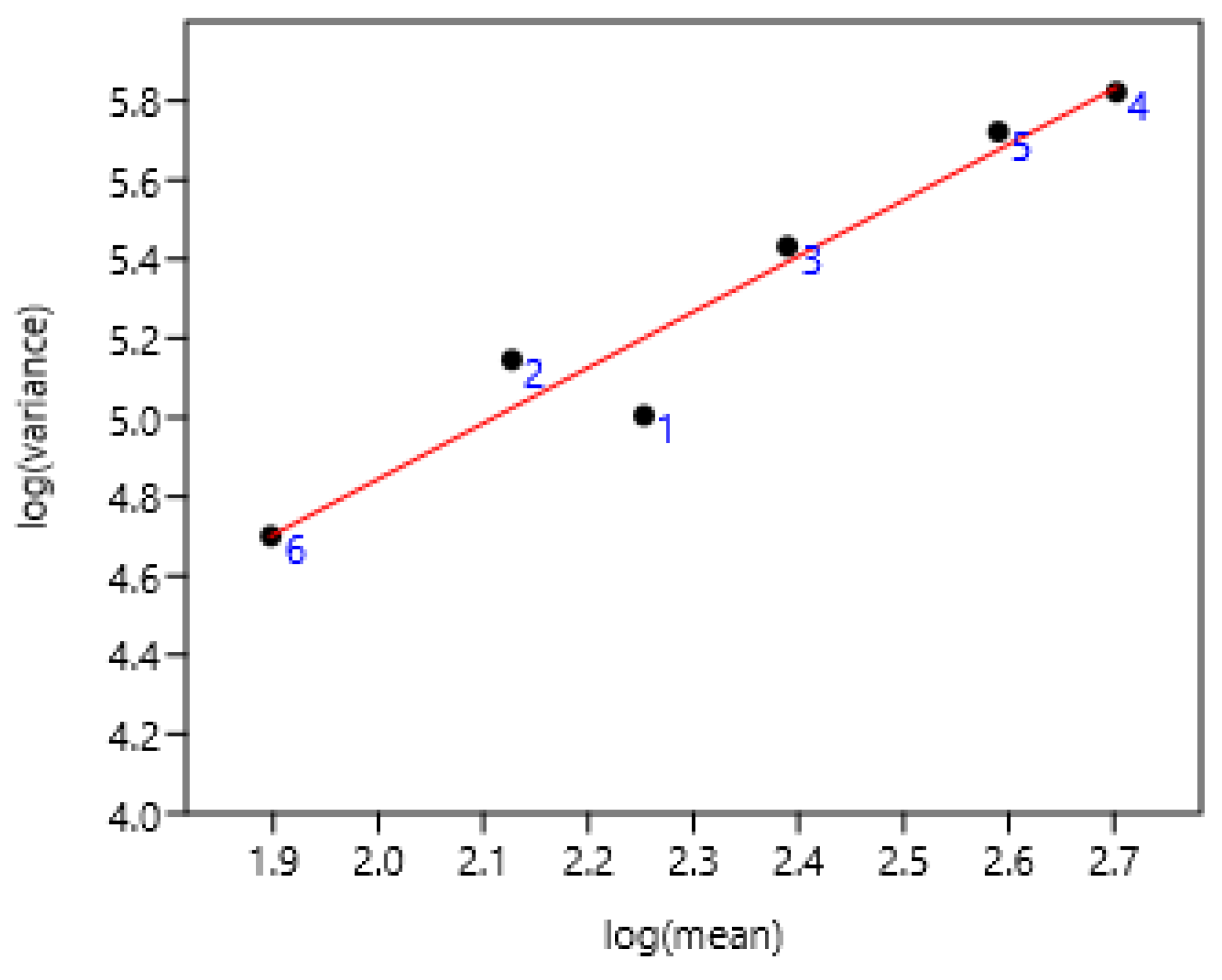

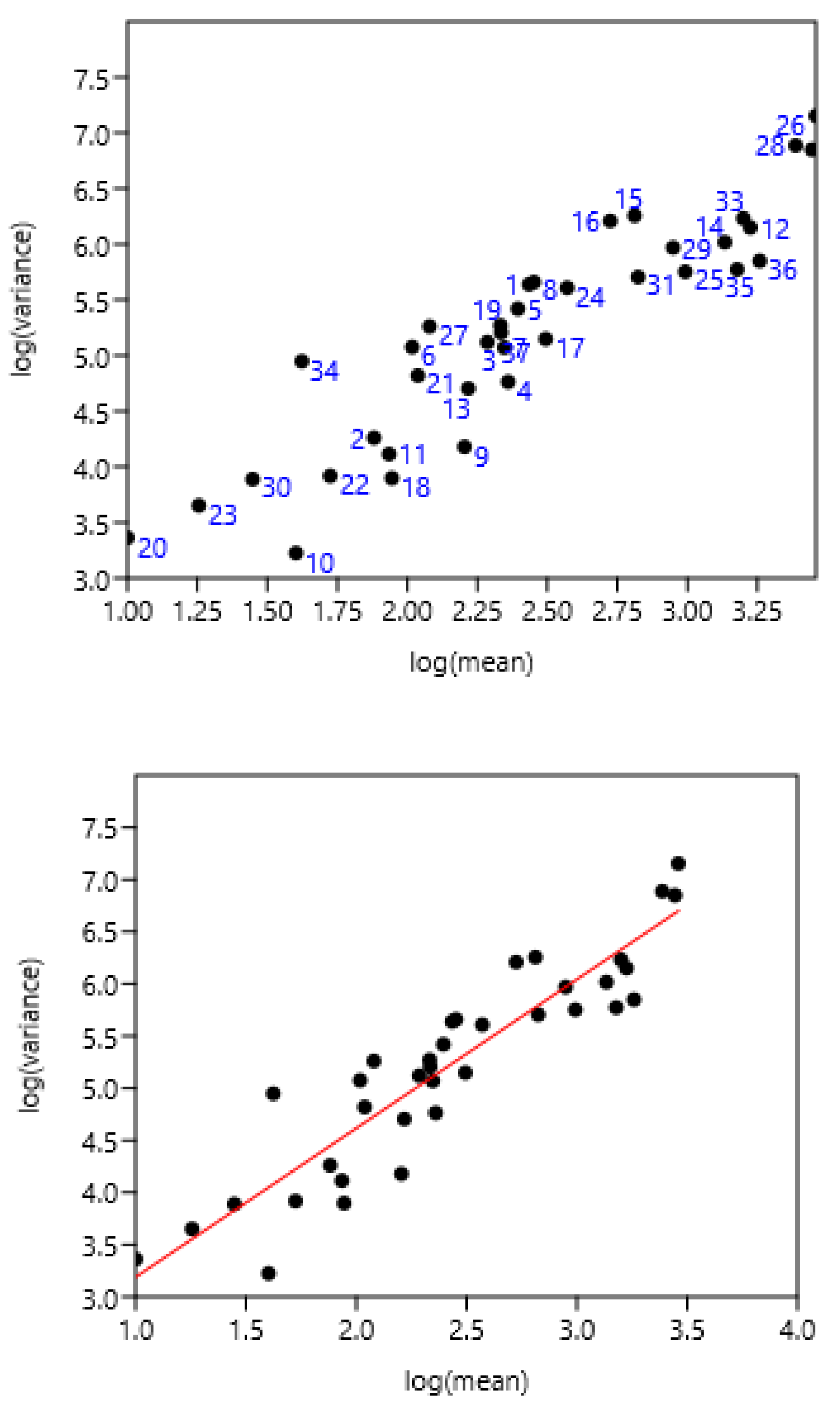

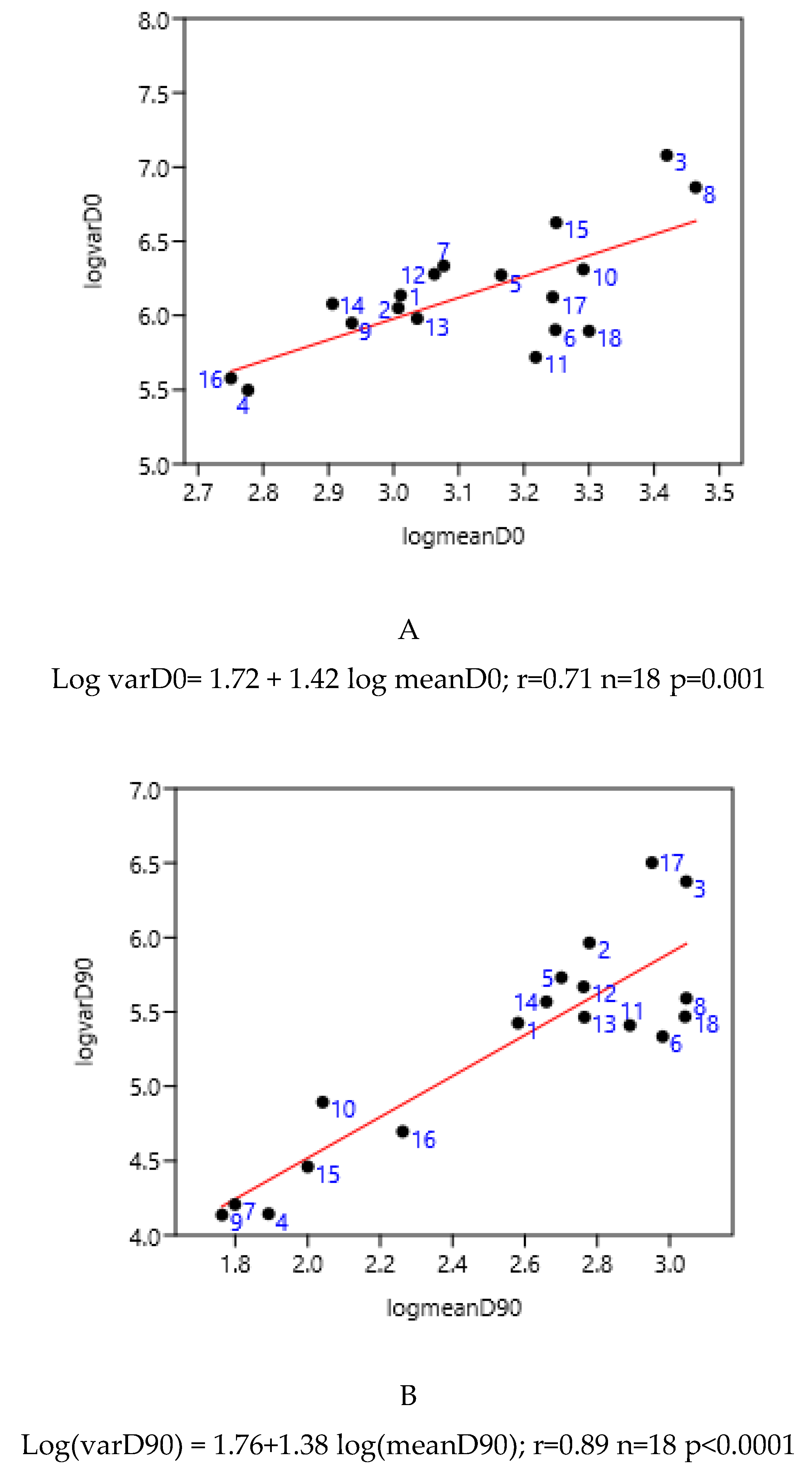

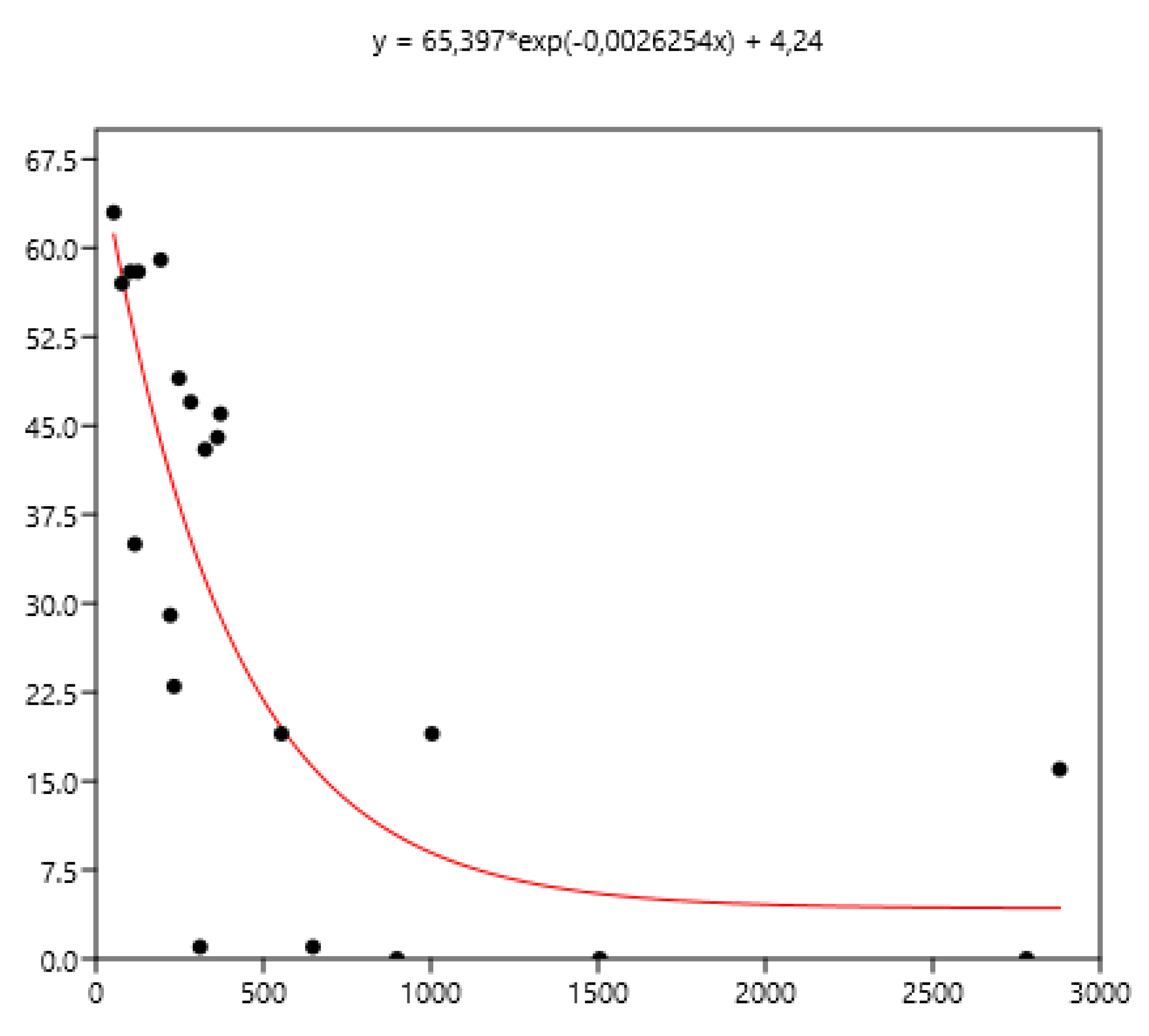

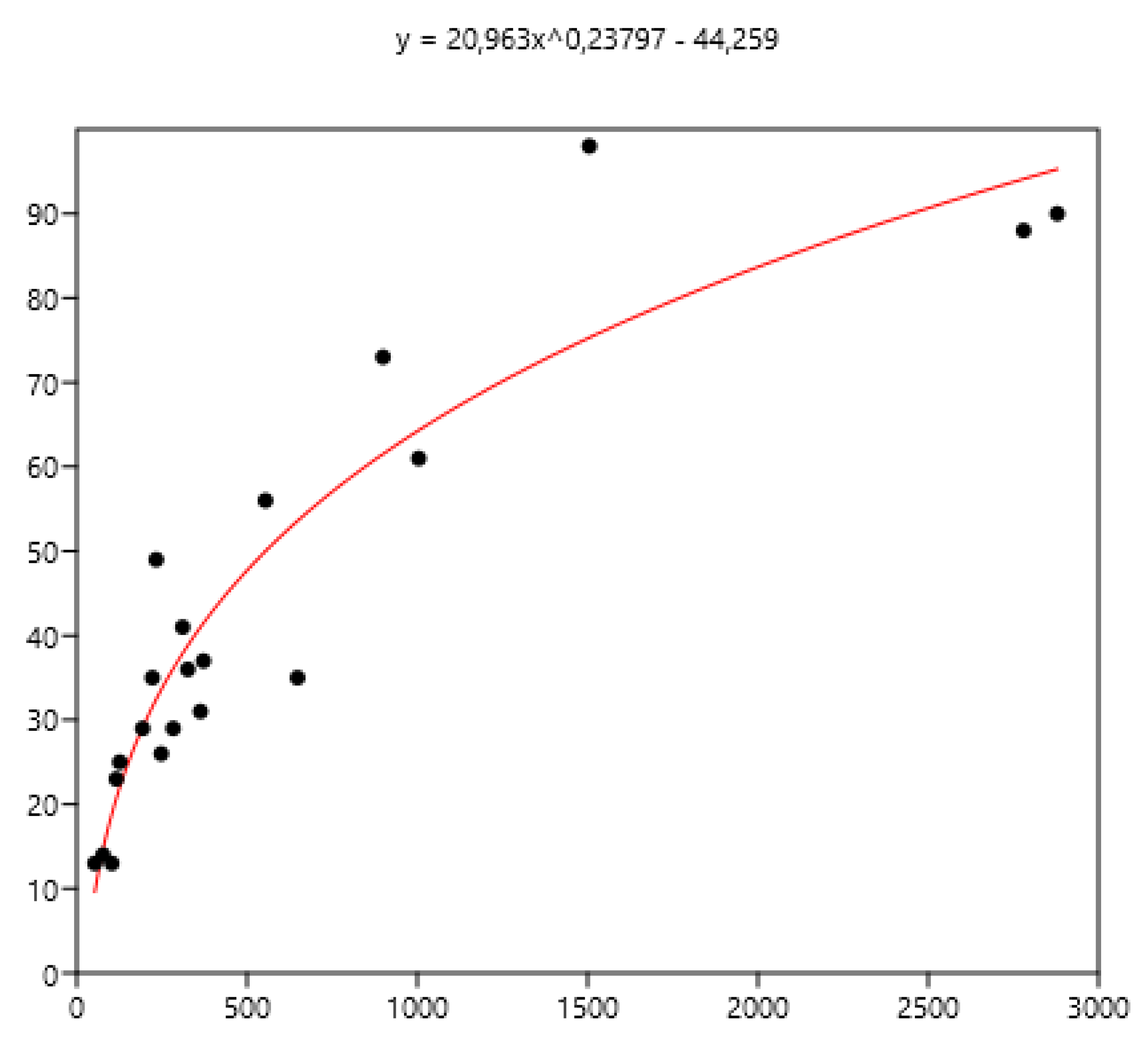

3.1. Relationship Between Average FEC and its Variance: Factors of Variation

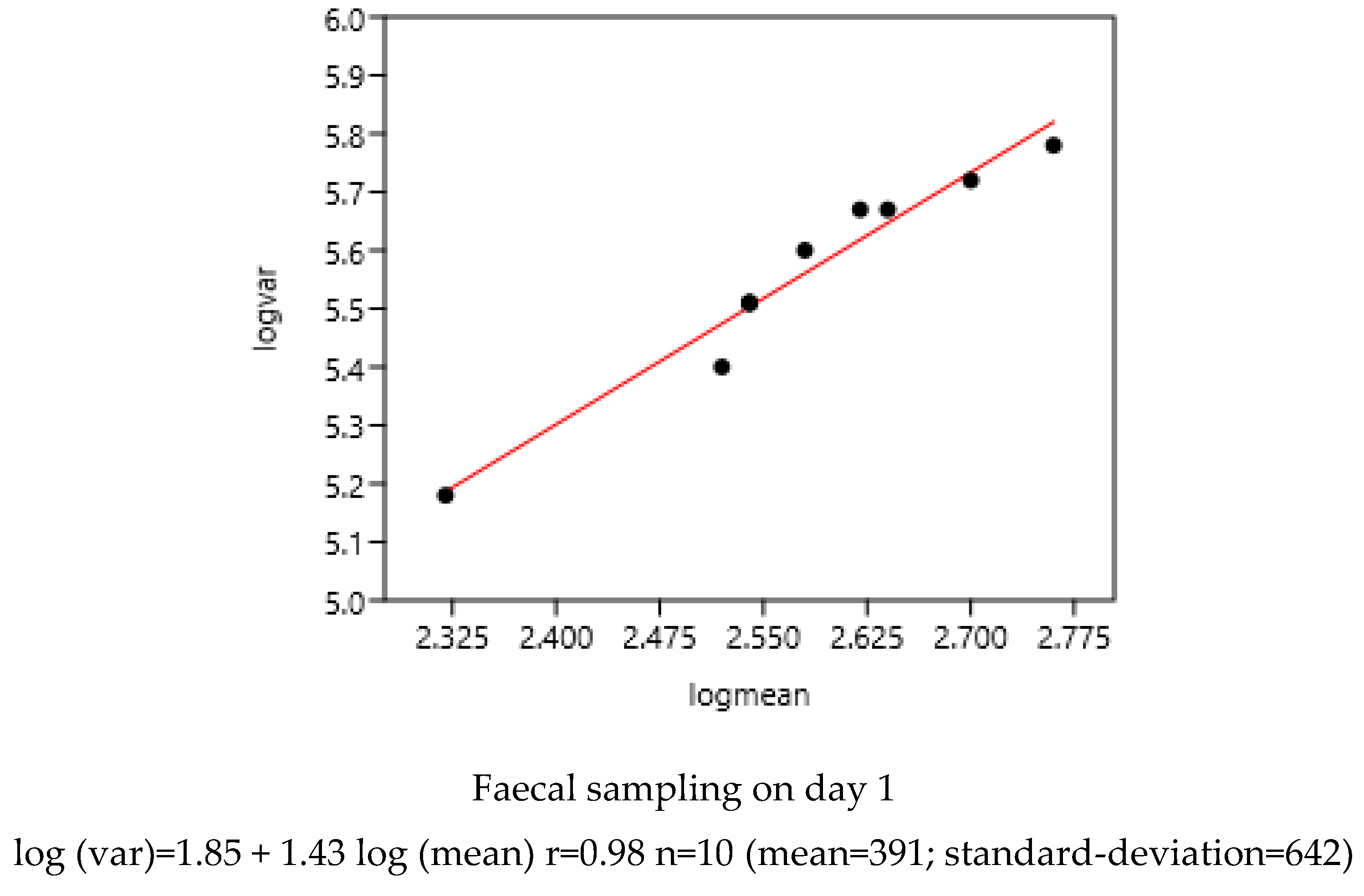

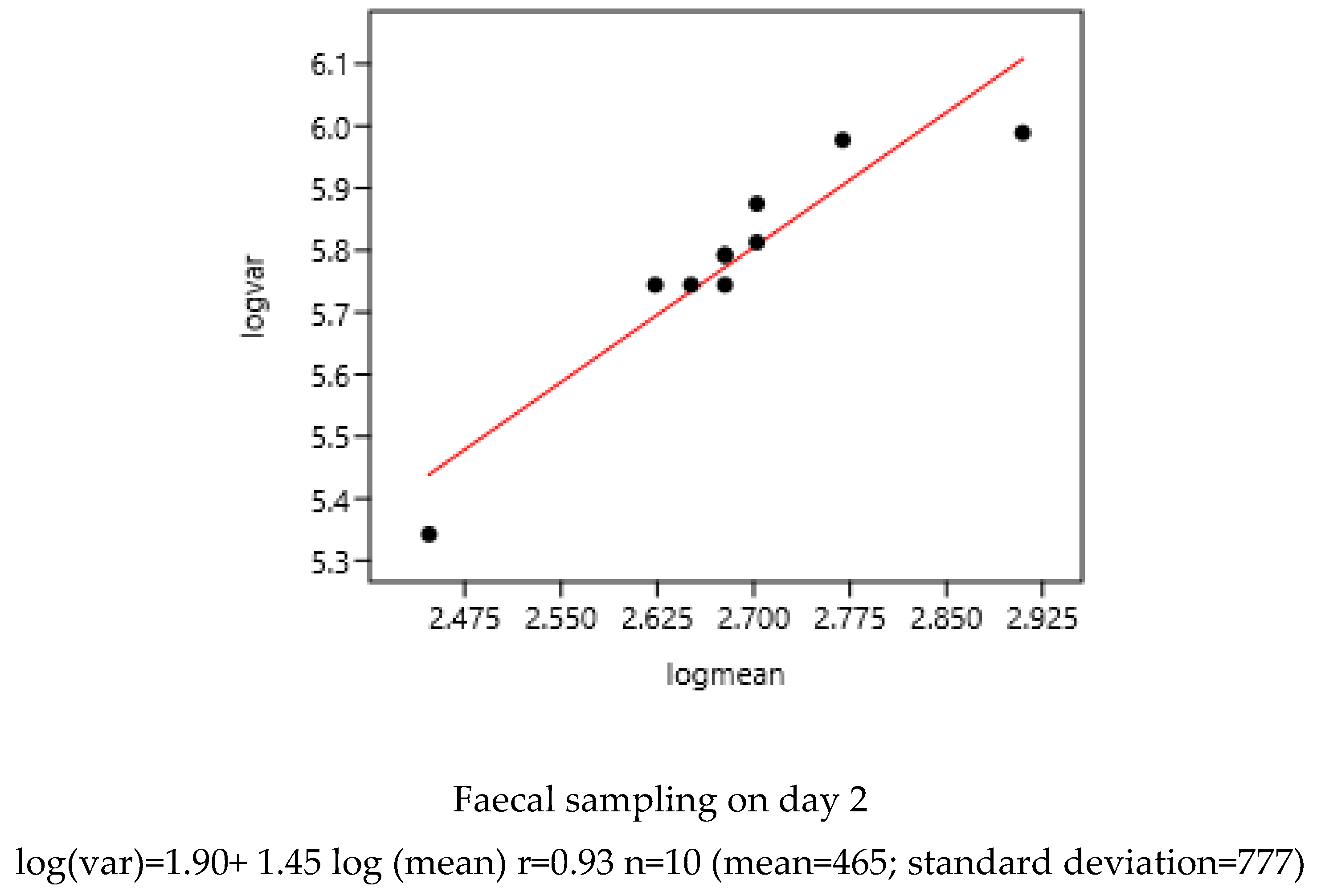

3.1.1. Sampling Day in a Farm

3.1.2. Age of Horses

3.1.3. Category of Horses

3.1.4. Regions of Three Countries

3.1.5. Previous Anthelmintic Treatment

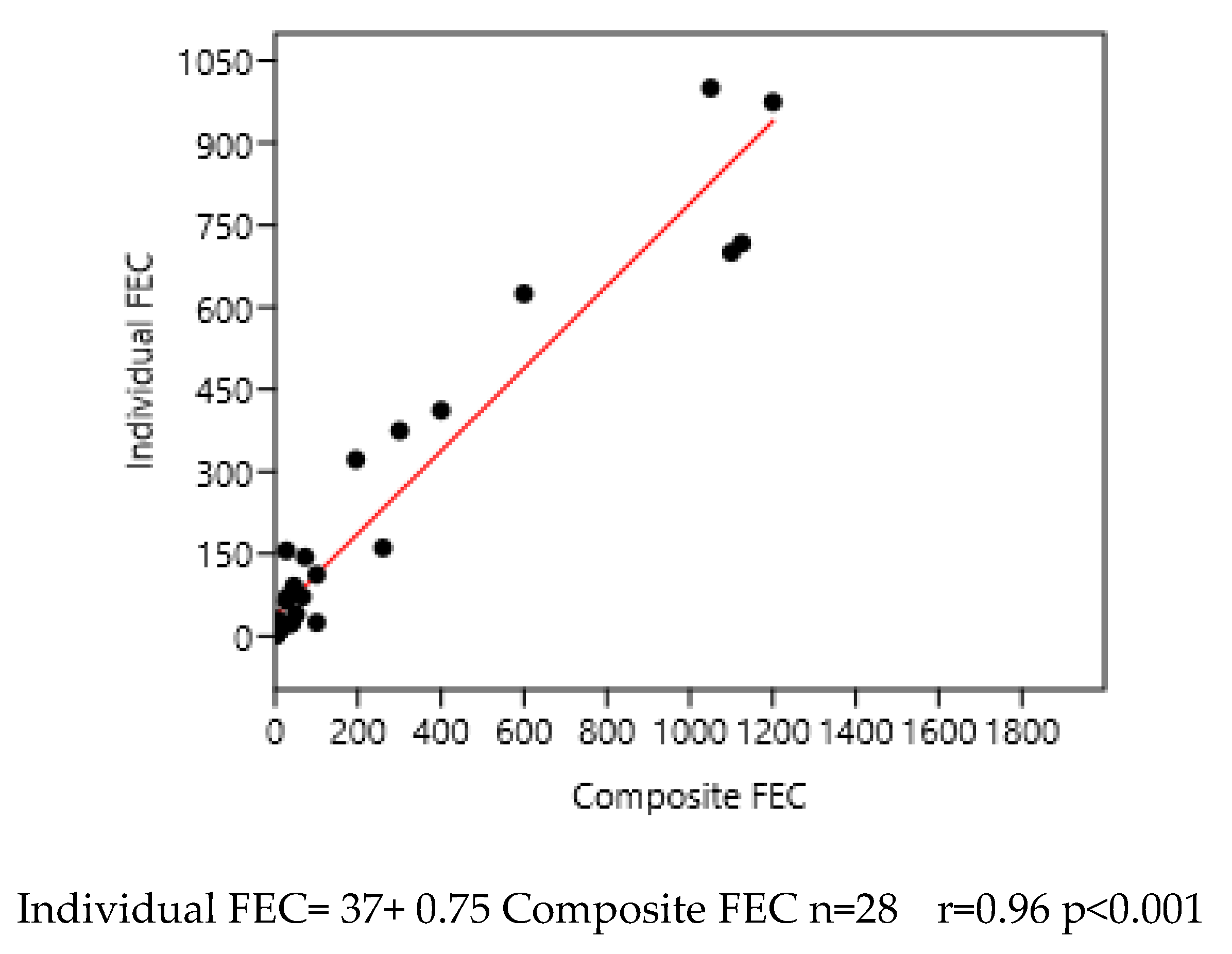

3.2. Composite Faecal Egg Count to Establish Average FEC

3.2.1. Composite from Faeces Collected from Horses

3.2.2. Composite from Faeces Collected from the Ground

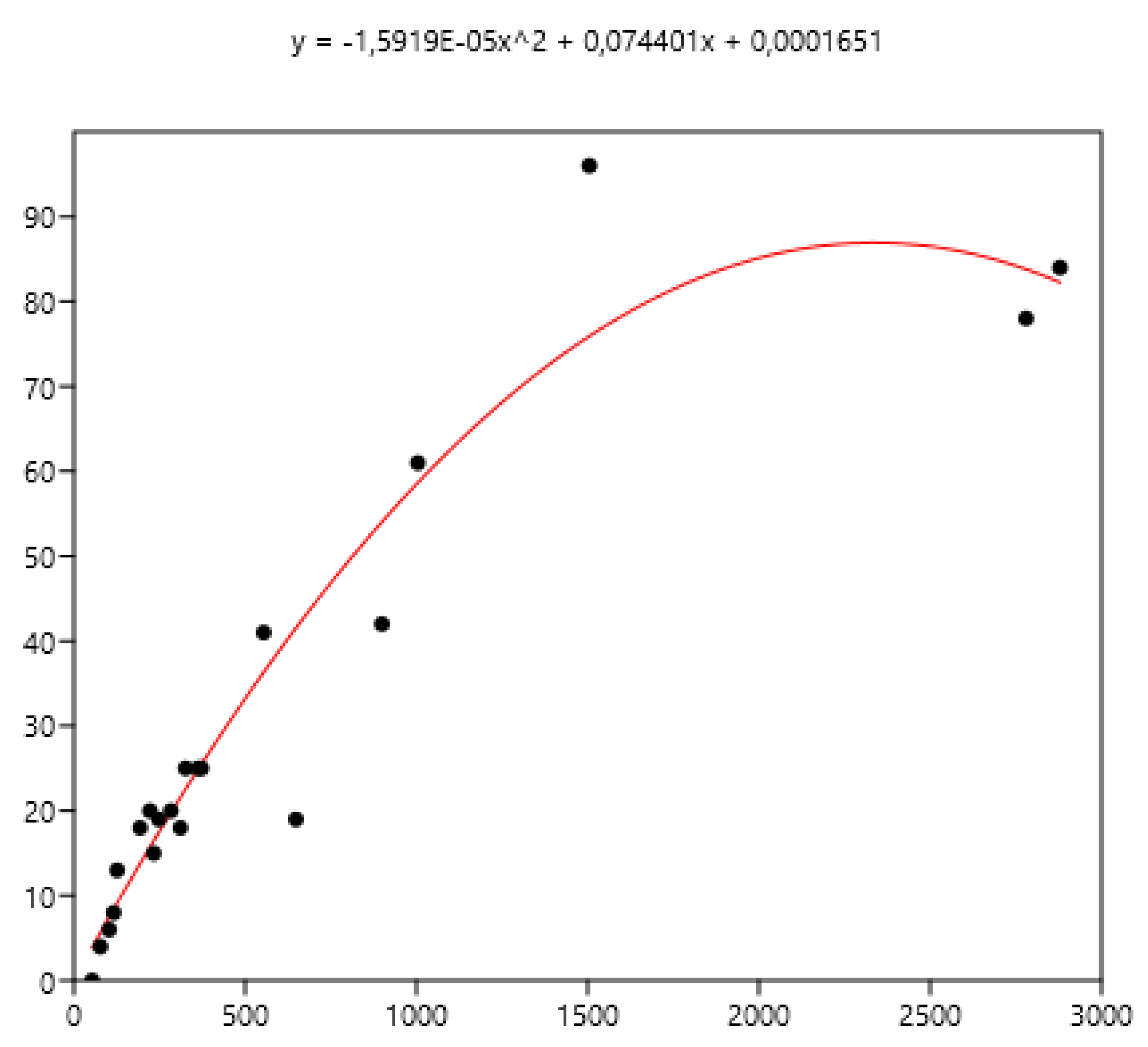

3.3. Relation Between Mean FEC and the Percentage of Horses with Different Indicators of FEC

4. Discussion

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

References

- Poulin, R. Are there general laws in parasite ecology? Parasitology, 2007,134, 763–776. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182006002150. [CrossRef]

- Gaba, S., Ginot, V., Cabaret, J. Modelling macroparasite aggregation using a nematode-sheep system: the Weibull distribution as an alternative to the negative binomial distribution? Parasitology, 2005,131,3, 393-401. [CrossRef]

- Relf, V. E., Morgan, E. R., Hodgkinson, J. E., Matthews, J. B. Helminth egg excretion with regard to age, gender and management practices on UK Thoroughbred studs. Parasitology, 2013, 140,5, 641-652. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. M., Nielsen, M. K. An evidence-based approach to equine parasite control: It ain't the 60s anymore. Equine Vety Educ.2010, 22,6, 306-316. [CrossRef]

- Morrill, A., Poulin, R., Forbes, M. R. Interrelationships a, d properties of parasite aggregation measures: a user’s guide. Int. J. for Parasitol., 2023, 53,14, 763-776. [CrossRef]

- Barger, I.A. The statistical distribution of trichostrongylid nematodes in grazing lambs. Int. J.for Parasitol.1985, 15, 645-649. [CrossRef]

- Boag, B., Hackett, C.A., Topham, P.B. The use of Taylor’s Power Law to describe the aggregated distribution of gastro-intestinal nematodes of sheep. Int. J. for Parasitol., 1992, 22, 267-270. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.R. Aggregation, variance, and the mean. Nature, 1961, 189,732–735.

- Smith, H. F. An empirical law describing heterogeneity in the yields of agricultural crops. The Journal of Agric. Sci., 1938, 28,1, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R. A.Taylor's power law: order and pattern in nature. Academic Press. London, 2019,640 p.

- Morgan, E.R.; Segonds-Pichon, A.; Ferté, H.;Duncan, P.; Cabaret, J. Anthelmintic Treatment and the Stability of Parasite Distribution in Ruminants. Animals 2023, 13, 1882. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D., Love, S. The pathogenic effects of experimental cyathostome infections in ponies. Vet. Parasitol. 1997, 70,1-3, 99-110. [CrossRef]

- Kilani M., Chermette R., Guillot J., Polack B., Duncan J.L., Cabaret J. Gastrointestinal nematodes. p. 1481-16003. In: Infectious and parasitic diseases of Livestock. 2. Bacterial diseases, Fungal diseases, Parasitic diseases. Ed. Tec & Toc Lavoisier, 2010, Paris.

- Kaplan, R. M. Anthelmintic resistance in nematodes of horses. Vet. Res. 2002, 33,5, 491-507. [CrossRef]

- Silva, P. A., Cernea, M., Madeira de Carvalho, L. Anthelmintic Resistance in Equine Nematodes-A Review on the Current Situation, with Emphasis in Europe. Bull. of the Univ. of Agric.Sciences & Vet. Med. Cluj-Napoca, 2019, 76(2). [CrossRef]

- Uriarte, J., Cabaret, J., Tanco, J. A. The distribution and abundance of parasitic infections in sheep grazing on irrigated or on non-irrigated pastures in North-Eastern Spain. Ann. de rech. vét. 1985, 16, 4, 321-325.

- Duncan, J.L., Love, S. Preliminary observations on an alternative strategy for the control of horse strongyles. Equine Vet. J. 1991, 23, 226–228. [CrossRef]

- Gomez, H.H., Georgi, J.R. Equine helminth infections: control by selective chemotherapy. Equine Vet. J. 1991, 23, 198–200. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen MK. Sustainable equine parasite control: Perspectives and research needs. Vet.Parasitol.2012, 185,1, 32–44. [CrossRef]

- Pfister, K., van Doorn, D. New perspectives in equine intestinal parasitic disease: insights in monitoring helminth infections. Vet. Clin. of North America. Equine Practice, 2018 34,1, 141-153.

- Matthee, S., McGeoch, M. A. Helminths in horses: use of selective treatment for the control of strongyles. J. of the South African Vet. Assoc., 2004,75,3, 129-136. [CrossRef]

- Becher, A. M., Mahling, M., Nielsen, M. K., Pfister, K. (2010). Selective anthelmintic therapy of horses in the Federal states of Bavaria (Germany) and Salzburg (Austria): An investigation into strongyle egg shedding consistency. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 171,1-2, 116-122. [CrossRef]

- Lüthin, S., Zollinger, A., Basso, W., Bisig, M., Caspari, N., Eng, V., Frey C.F., Grimm F., Igel P., Lüthi S., Regli W., Roelfstra L., Rosskopf M., Steiner B., Stöckli M.,. Waidyasekera D., Waldmeier P., Schnyder M., Torgerson P.R. Hertzberg, H. Strongyle faecal egg counts in Swiss horses: A retrospective analysis after the introduction of a selective treatment strategy. Vet. Parasitol. 2023,323, 110027.

- Jürgenschellert, L., Krücken, J., Bousquet, E., Bartz, J., Heyer, N., Nielsen, M. K., von Samson-Himmelstjerna, G. Occurrence of strongylid nematode parasites on horse farms in Berlin and Brandenburg, Germany, with high seroprevalence of Strongylus vulgaris infection. Frontiers in vet. sci.2022, 9, 892920. [CrossRef]

- Sallé, G., Cortet, J., Koch, C., Reigner, F., Cabaret, J. Economic assessment of FEC-based targeted selective drenching in horses. Vet. Parasitol.2015, 214,1-2, 159-166. [CrossRef]

- Vineer H.R., F. Vande Velde, K. Bull, E. Claerebout, E.R. Morgan. Attitudes towards worm egg counts and targeted selective treatment against equine cyathostomins. Prev. Vet. Med., 144, 66-74,. [CrossRef]

- Kornaś, S., J. Cabaret, M. Skalska et B. Nowosad. Horse infection with intestinal helminths in relation to age, sex, access to grass and farm system. Vet. Parasitol.2010, 174:.285-291. [CrossRef]

- Pagnon R. Résistance aux anthelminthiques des strongles chez les équidés : enquête dans un centre équestre du sud de la France. Thèse Doctorat Vétérinaire, Université de Toulouse,2005, 121 p.

- Henriksen,S. A., Korsholm,H. A method for culture and recovery of gastrointestinal strongyle larvae. Nordisk Vet. Med. 1983, 35, 11, 429–430.

- Amer, M. M., Desouky, A. Y., Helmy, N. M., Abdou, A. M., Sorour, S. S. Identifying 3rd larval stages of common strongylid and non-strongylid nematodes (class: Nematoda) infecting Egyptian equines based on morphometric analysis. BMC Vet. Res. 2022,18, 1, 432. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan R.K., Denwood M.J., Nielsen M.K., Thamsborg S.M., Torgerson P.R., Gilleard J.S., Dobson R.J., Vercruysse J., Levecke B. World Association for the Advancement of Veterinary Parasitology (W.A.A.V.P.) guideline for diagnosing anthelmintic resistance using the faecal egg count. reduction test in ruminants, horses and swine. Vet. ParasitoL,318,2023,109936. [CrossRef]

- Eisler, Z., Bartos, I., Kertész, J. Fluctuation scaling in complex systems: Taylor's law and beyond. Adv. in Physics, 2008, 57,1 89-142. [CrossRef]

- Johnson PTJ, Wilber MQ. Biological and statistical processes jointly drive population aggregation: using host–parasite interactions to understand T,aylor’s power law. Proc. R. Soc. B 2017, 284: 20171388. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.1388. [CrossRef]

- McVinish R, Lester RJG. Measuring aggregation in parasite populations. J. R. Soc. Interface2020, 17: 20190886. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2019.0886. [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, R. C., Vineer, H. R., Grainger-Wood, R., Morgan, E. R. Heterogeneity in helminth infections: factors influencing aggregation in a simple host–parasite system. Parasitology, 2020, 147, 1, 65-77. [CrossRef]

- Galvani, A. P. Immunity, antigenic heterogeneity, and aggregation of helminth parasites. Journal of Parasitol., 2003,89, 2, 232-241. [CrossRef]

- Boag, B.; Lello, J.; Fenton, A.; Tompkins, D.M.; Hudson, P.J. Patterns of parasite aggregation in the wild European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Int. J. Parasitol. 2001, 31, 1421–1428. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, E.R., Cavill, L., Curry, G.E., Wood, R.M., Mitchell, E.S.E. Effects of aggregation and sample size on composite faecal egg counts in sheep. Vet. Parasitol.2005, 131, 79 – 87. [CrossRef]

- Eysker, M., Bakker, J., Van Den Berg, M., Van Doorn, D. C. K., & Ploeger, H. W. The use of age-clustered pooled faecal samples for monitoring worm control in horses. Vet. Parasitol. 2008,151,2-4, 249-255. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M. K., Baptiste, K. E., Tolliver, S. C., Collins, S. S., Lyons, E. T. Analysis of multiyear studies in horses in Kentucky to ascertain whether counts of eggs and larvae per gram of feces are reliable indicators of numbers of strongyles and ascarids present. Vet. Parasitol. 2010,174,1-2), 77-84. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ortiz de Montellano C., González-Reyes L., Toledo-Alvarado H.O. 2025. Epidemiological patterns of cyathostominae burden in Warmblood horses in Mexico. WAAVP 2025, 30th Conference of the World Association for the Advancements of Veterinary Parasitology. Curitiba. Proceeding p. 61-62.

- Matthews, J. B. Anthelmintic resistance in equine nematodes. Int. J. Parasitol.: Drugs and Drug Resistance, 2014, 4, 3, 310-315. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen MK., Mittel L., Grice, A., Erskine, M., Graves, E., Vaala, W., Tully, R. C., French, D. D. 2013, AAEP Parasite Control Guidelines. (Accessed on 15 th of November2025).

- Rendle D, Austin C, Bowen M, Cameron I, Furtado T, Hodgkinson J, McGorum B, Matthews J . Equine de-worming: a consensus on current best practice. UK-Vet Equine, 2019, 3, Sup1, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, E. J. A., Woodgate, R. G., Raidal, S. L., & Hughes, K. J. The application of faecal egg count results and statistical inference for clinical decision making in foals. Vet. Parasitol. 2019 270, 7-12. [CrossRef]

- Denwood, M. J., Love, S., Innocent, G. T., Matthews, L., McKendrick, I. J., Hillary, N., Reid, S. W. J. Quantifying the sources of variability in equine faecal egg counts: implications for improving the utility of the method. Vet. Parasitol. 2012,188,1-2, 120-126. [CrossRef]

- Lester, H. E., Morgan, E. R., Hodgkinson, J. E., Matthews, J. B. Analysis of strongyle egg shedding consistency in horses and factors that affect it. J. of Equine Vet. Sci, 2018, 60, 113-119. [CrossRef]

- Kuzmina, T. A., Lyons, E. T., Tolliver, S. C., Dzeverin, I. I., Kharchenko, V. A. Fecundity of various species of strongylids (Nematoda: Strongylidae)—parasites of domestic horses. Parasitol. Res. 2012,111,6, 2265-2271. [CrossRef]

- Fleurance G., Martin-Rosset W., Dumont B., Duncan P., Farrugia A., Lecomte T. Environmental impact of horses. p. 481-504. In: Equine nutrition, Ed. Martin-Rosset, Wageningen Academic Publishers. Wageningen, 2013.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).