1. Introduction

With the continuous growth of the global population, industrial-scale food production has increased significantly. However, due to multiple factors, a substantial amount of food is discarded as waste, resulting in approximately 1.3 billion tons of organic waste generated annually, primarily due to inadequate storage, expiration, microbial spoilage, physical damage, and other forms of degradation [

1]. Despite this, food waste still contains abundant organic components—especially bioactive compounds—that cannot be effectively utilized when food waste is landfilled, incinerated, or processed into animal feed [

2]. Numerous studies have shown that bioactive substances such as polyphenols, flavonoids, hydrocarbons, and pigments can be efficiently recovered from food waste via appropriate treatment [

3,

4,

5].

Flavonoids are naturally occurring bioactive compounds renowned for their antioxidant activity, potential anticancer properties, beneficial effects on metabolic regulation, and protective roles in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health [

6]. (+)-Catechin is a typical flavonoid present in various foods, including grapes, chocolate, and tea. Putra et al. and Tang et al. have reported studies on recovering catechins from peanut skin and grape waste, respectively [

7,

8]. Thus, the recovery of (+)-catechin from food waste emerges as a promising and sustainable strategy for food waste valorization. Currently, solvent extraction, microwave-assisted extraction, and combined extraction techniques are frequently used to extract (+)-catechin from different sources. For isolation and purification, adsorption-based methods using materials such as resins or molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) are considered the most efficient, owing to their high selectivity and adsorption capacity.

The core of adsorption-based methods lies in the development of functional sorbents. Toward this goal, our research group has previously fabricated a series of modified silica sorbents for isolating bioactive compounds from natural plants, where ionic liquids (ILs) played a key role in enhancing adsorption performance [

9]. ILs are well recognized as “green” reaction media with excellent chemical properties; their tunable hydrophobicity, miscibility with various inorganic/organic solvents, and specific interactions between functional groups enable their widespread application as solvents or sorbent modifiers [

9]. Several studies have demonstrated that IL-modified materials can be used for the detection and extraction of catechins: for example, ILs have been applied to extract flavonoids or catechins from grape seeds and tea [

10,

11], while IL-modified magnetic nanoparticles, silica, and resins have successfully adsorbed catechins from grape juice and green tea, respectively [

12,

13,

14].

These findings indicate that interactions exist between IL groups and catechin molecules, highlighting the potential of IL-modified sorbents for the adsorption and separation of (+)-catechin from complex matrices.

To improve the adsorption selectivity and capacity of sorbents toward (+)-catechin, the physicochemical properties of the substrate (in addition to the selection of suitable ILs) exert a critical influence on adsorption efficiency. According to previous studies, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)—with their unique nanoporous coordination structures—facilitate specific intermolecular interactions [

15,

16,

17]. Consequently, IL-modified MOFs have attracted considerable research attention for their tunable separation mechanisms and high enrichment efficiency [

18,

19,

20].

Yang et al. applied IL-modified MOFs for the extraction and adsorption of bioactive compounds [

21], and our team has also established a theoretical foundation for the practical application of IL-modified ZIF67 (a typical MOF) in isolating bioactive compounds from herbal plants [

22,

23]. However, the stability of IL-modified MOFs in aqueous environments requires further improvement [

24]. To address this limitation, this study developed an IL-modified ZIF67-coated silica sorbent and employed a solid-phase extraction (SPE) method for the recovery of (+)-catechin from chocolate waste.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Silica (15-31 μm), (3-chloropropyl) trimethoxysilane (98.0%), 2-methylimidazole (98.0%), cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (CO(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, 99.0%), imidazole (99.0%), N-bromosuccinimide (NBS, 98.0%), 1-chlorobutane (98.0%), 1-chlorohexane (98.0%), and (+)-catechin (97.0%) were purchased from Aladdin Inc. (Shanghai, China). HPLC-grade acetonitrile and methanol were obtained from CINC High Purity Solvents Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Acetonitrile, triethylamine, acetic acid, and other organic solvents were supplied by Beilian Company (Tianjin, China), with purities ≥ 99.0%. Ultrapure water was produced using a water purification system (UPH-I-5, Youpu, China).

2.2. Apparatus

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were acquired using a MIRA3 scanning microscope (TESCAN, Brno, Czech Republic). Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy (Nicolet 6700, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, USA) was performed using KBr pellets over the wavenumber range of 400.0–4000.0 cm⁻¹ at a scan rate of 20 scans min⁻¹. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was conducted using a Labsys evo instrument (Setaram, Caluire Et Cuire, France) at a heating rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere. HPLC analysis was performed on an LC3000 system (CXTH, Beijing, China) equipped with a TC-C18 column (4.6 × 150.0 mm, 5.0 μm, Agilent, Santa Clara, USA). The mobile phase was acetonitrile/water (20:80, v/v) containing 1.0% (v/v) acetic acid, with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min at a column temperature of 30 °C. Detection was carried out at a UV wavelength of 280.0 nm, and the injection volume was 10.0 μL.

2.3. Preparation of Ionic Liquid-Modified Sorbents

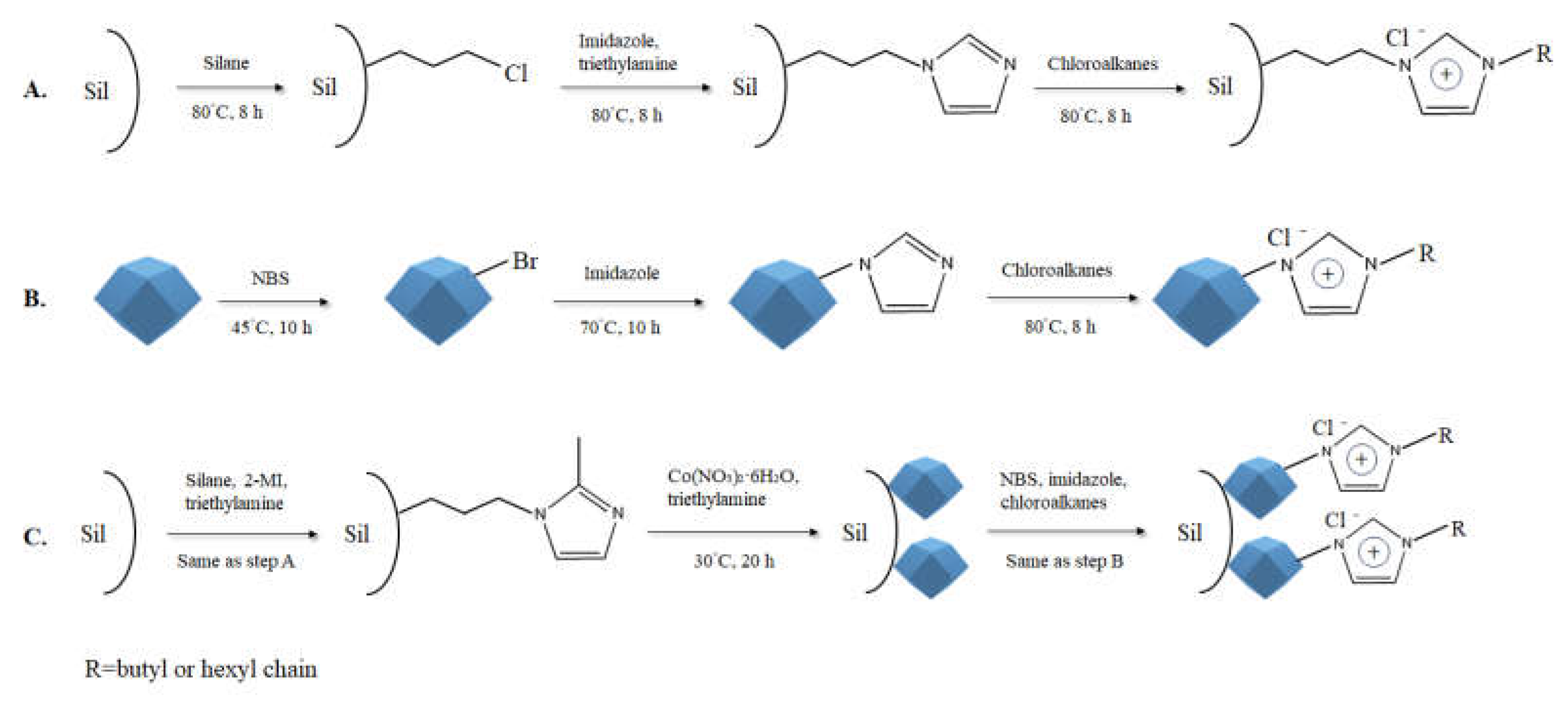

According to our previous study [

24], ILs with 4-carbon (butyl) or 6-carbon (hexyl) alkyl chains exhibit enhanced interactions with (+)-catechin due to well-matched hydrophilic–hydrophobic properties. Based on this, nine sorbents were prepared (

Figure 1).

2.3.1. Step A: Preparation of IL-Modified Silica Sorbents

First, silica was stirred in a 10.0% (v/v) hydrochloric acid aqueous solution for 24 h to activate surface -OH groups. After washing with ultrapure water until the pH reached 7.0, activated silica (Sil) was obtained.

In a round-bottom flask, 20.0 g of Sil and 45.0 g of (3-chloropropyl) trimethoxysilane were mixed with 150.0 mL of toluene. The mixture was heated to 80 °C and stirred for 8 h to synthesize 3-chloropropyl-functionalized Sil. Subsequently, 30.0 g of imidazole, 0.03 g of triethylamine, and 150.0 mL of toluene were added to the flask, and the mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 8 h to produce imidazole-immobilized Sil (Sil-imidazole).

To introduce alkyl chains, 20.0 g of Sil-imidazole was mixed with 150.0 mL of toluene, and 20.0 g of either 1-chlorobutane or 1-chlorohexane was added. The mixture was heated to 80 °C for 8 h, yielding two IL-modified silica sorbents: Sil-Bmim (butyl-modified) and Sil-Hmim (hexyl-modified).

2.3.2. Step B: Preparation of IL-Modified ZIF67 Sorbents

ZIF67 was first synthesized as follows: 15.0 g of CO(NO₃) ₂·6H₂O and 65.0 g of 2-methylimidazole were separately dissolved in 100.0 mL of methanol under ultrasonic irradiation. The 2-methylimidazole solution was then slowly added dropwise to the stirred CO(NO₃) ₂ solution. The mixture was stirred continuously at 25 °C for 8 h and aged at room temperature for 16 h. The resulting precipitate was collected by centrifugation at 5000 rpm for 5 min, washed three times with methanol, and dried in an oven at 70 °C for 10 h to obtain purple ZIF67 powder. Next, 4.5 g of ZIF67 and 4.2 g of NBS were mixed in 80 mL of dichloromethane under ultrasonic irradiation. The mixture was heated to 45 °C and reacted for 10 h. The solid product (ZIF67-Br) was collected by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 5 min), washed five times with dichloromethane, and dried at 50 °C for 10 h. Then, 4.0 g of ZIF67-Br, 2.0 g of triethylamine, and 11.5 g of imidazole were added to 150 mL of ethanol in a flask. The mixture was heated to 70 °C and reacted for 10 h; after washing and drying (same as above), imidazole-immobilized ZIF67 (ZIF67-Imidazole) was obtained. Finally, 4.0 g of ZIF67 Imidazole was mixed with 100.0 mL of ethanol, and 10.0 g of 1-chlorobutane or 1-chlorohexane was added. The mixture was heated to 80 °C for 8 h, yielding ZIF67-Bmim or ZIF67-Hmim.

2.3.3. Step C: Preparation of IL-Modified ZIF67-Coated Silica Sorbents

Sil was first modified with 2-methylimidazole using the same method as Step A (imidazole immobilization). Then, 30.0 g of 2-methylimidazole-modified Sil, 25.8 mL of triethylamine, and 20.0 g of CO(NO₃) ₂·6H₂O were dissolved in 100.0 mL of ultrapure water. The mixture was stirred and aged at room temperature for 16 h. The precipitate (Sil@ZIF67) was collected by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 5 min), washed three times with methanol, and dried at 60 °C for 12 h. Finally, Sil@ZIF67 was modified with ILs using the same procedure as Step B, producing Sil@ZIF67-Bmim and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim.

2.4. Adsorption Isotherm and Kinetics Studies

A calibration curve for (+)-catechin was constructed using seven concentrations (0.0001–0.5 mg/mL). The linear regression equation was y = 0.19x + 0.001 (where y is peak area and x is (+)-catechin concentration, mg/mL) with a correlation coefficient (R²) of 0.97, indicating good linearity.

2.4.1. Adsorption Capacity Evaluation

To determine the maximum adsorption capacity of each sorbent, 0.005 g of sorbent was mixed with 4.0 mL of 0.45 mg/mL (+)-catechin aqueous solution and shaken at 25 °C for 10 h. After adsorption equilibrium, the residual (+)-catechin concentration was measured by HPLC.

2.4.2. Adsorption Isotherm Experiments

For isotherm studies, 0.005 g of sorbent was immersed in 4.0 mL of (+)-catechin aqueous solution with concentrations ranging from 0.001 to 0.45 mg/mL at room temperature. The concentrations of (+)-catechin before and after adsorption were determined by HPLC. The equilibrium adsorption capacity (

Qₑ, mg/g) and adsorption efficiency (

E%) were calculated using Equations (1) and (2):

where

C₀ (mg/mL) is initial (+)-catechin concentration,

Cₑ (mg/mL) is equilibrium (+)-catechin concentration,

V (mL) is solution volume, and

m (g) is sorbent mass.

2.4.3. Adsorption Kinetics Experiments

For kinetics studies, 0.005 g of sorbent was added to 4.0 mL of 1.0 mg/mL (+)-catechin solution at 30 °C, and samples were collected at different time intervals (1.0-120.0 min). The experimental data were fitted to pseudo-first-order (Equation (3)) and pseudo-second-order (Equation (4)) kinetic models:

where

Qₜ (mg/g) is adsorption capacity at time

t (min), k₁ (min⁻¹) is pseudo-first-order rate constant, and k₂ (g (mg · min)

-1) is pseudo-second-order rate constant.

2.5. Stability and Reusability Tests

To evaluate sorbent reusability, 0.015 g of sorbent was immersed in 1.0 mL of 1.0 mg/mL (+)-catechin aqueous solution at 30 °C for 120.0 min. After measuring the residual (+)-catechin concentration by HPLC, the sorbent was desorbed and rinsed with a methanol/water mixture (70:30, v/v) for more than 10 cycles. The adsorption–desorption cycle was repeated under identical conditions, and the adsorption capacity was determined after each cycle.

2.6. Isolation of (+)-Catechin from Chocolate Waste Using SPE

First, (+)-catechin was extracted from chocolate waste: 10.0 g of cocoa shell waste powder (a byproduct of chocolate production) was immersed in 20.0 mL of water at 65 °C for 8 h. The extract was collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon membrane. For SPE, 0.3 g of sorbent was packed into a standard SPE cartridge (Φ 0.9 cm) and preconditioned with 6.0 mL of methanol. The filtered cocoa shell extract was then loaded onto the cartridge, and the effluent was collected. To elute (+)-catechin, 3.0 mL of eluents with different polarities (water, acetonitrile, methanol, or methanol/water containing 1% (v/v) acetic acid) were passed through the cartridge at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The eluate was analyzed by HPLC to determine the (+)-catechin recovery rate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization

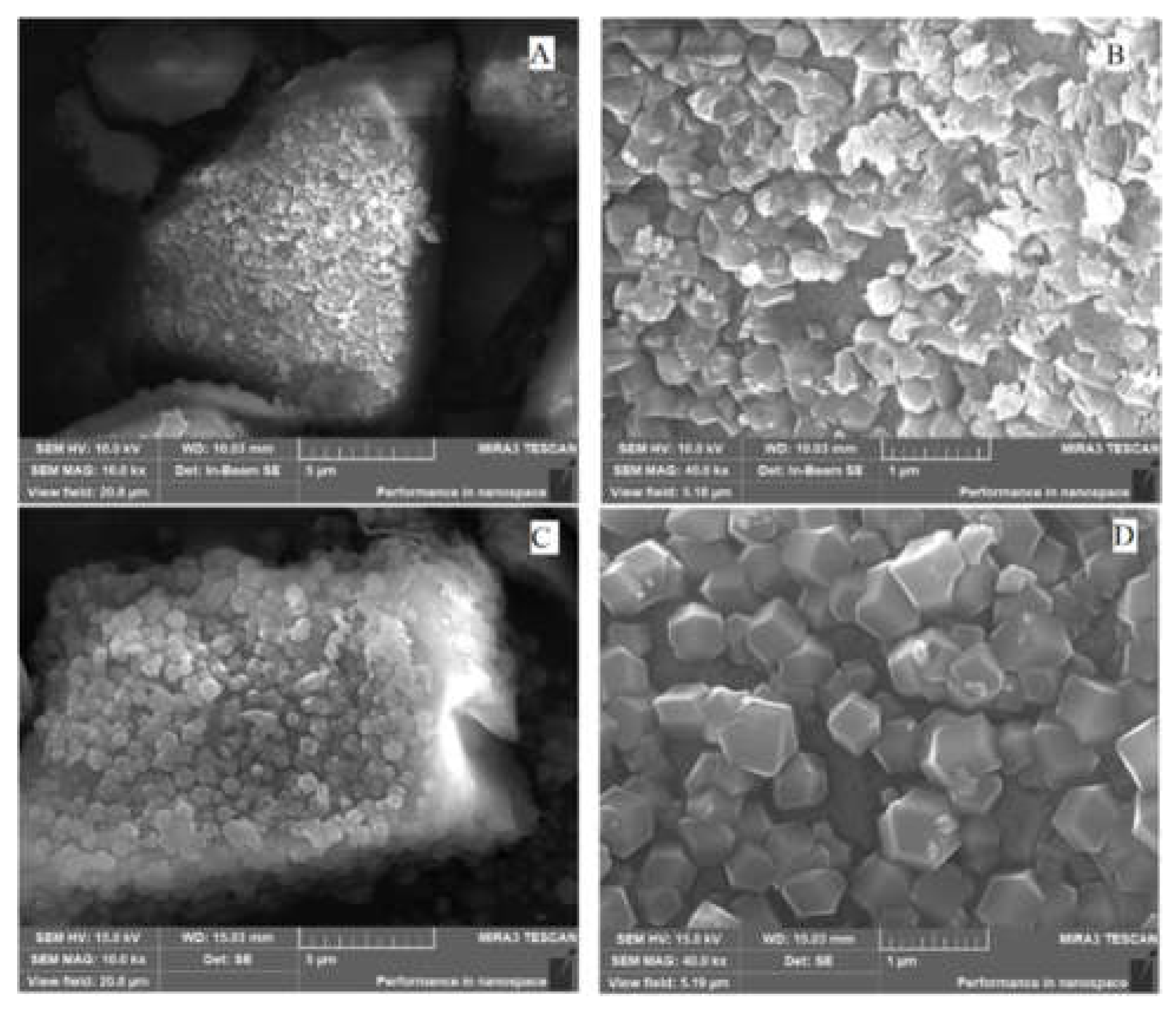

The SEM microstructures of Sil@ZIF67-IL are illustrated in

Figure 2. As depicted in Figure D, well-defined rhombic dodecahedral crystals with uniform particle sizes (≈200-300 nm) are distinctly observed, which is consistent with the characteristic morphology of ZIF67, thereby confirming the successful synthesis of the metal-organic framework. In Figure B, the crystals exhibit slightly rough surfaces, indicative of the successful grafting of ionic liquid (IL) onto the MOF matrix. Figure A presents the silica substrate under low magnification, while Figure C reveals numerous dodecahedral particles uniformly dispersed on the silica surface, demonstrating that ZIF67-IL crystals are firmly anchored onto the silica support. This hierarchical architecture is advantageous for exposing active adsorption sites and facilitating mass transfer, thus enhancing the adsorption performance. In summary, the SEM characterization results unequivocally verify the successful fabrication of the Sil@ZIF67-IL clearly confirm.

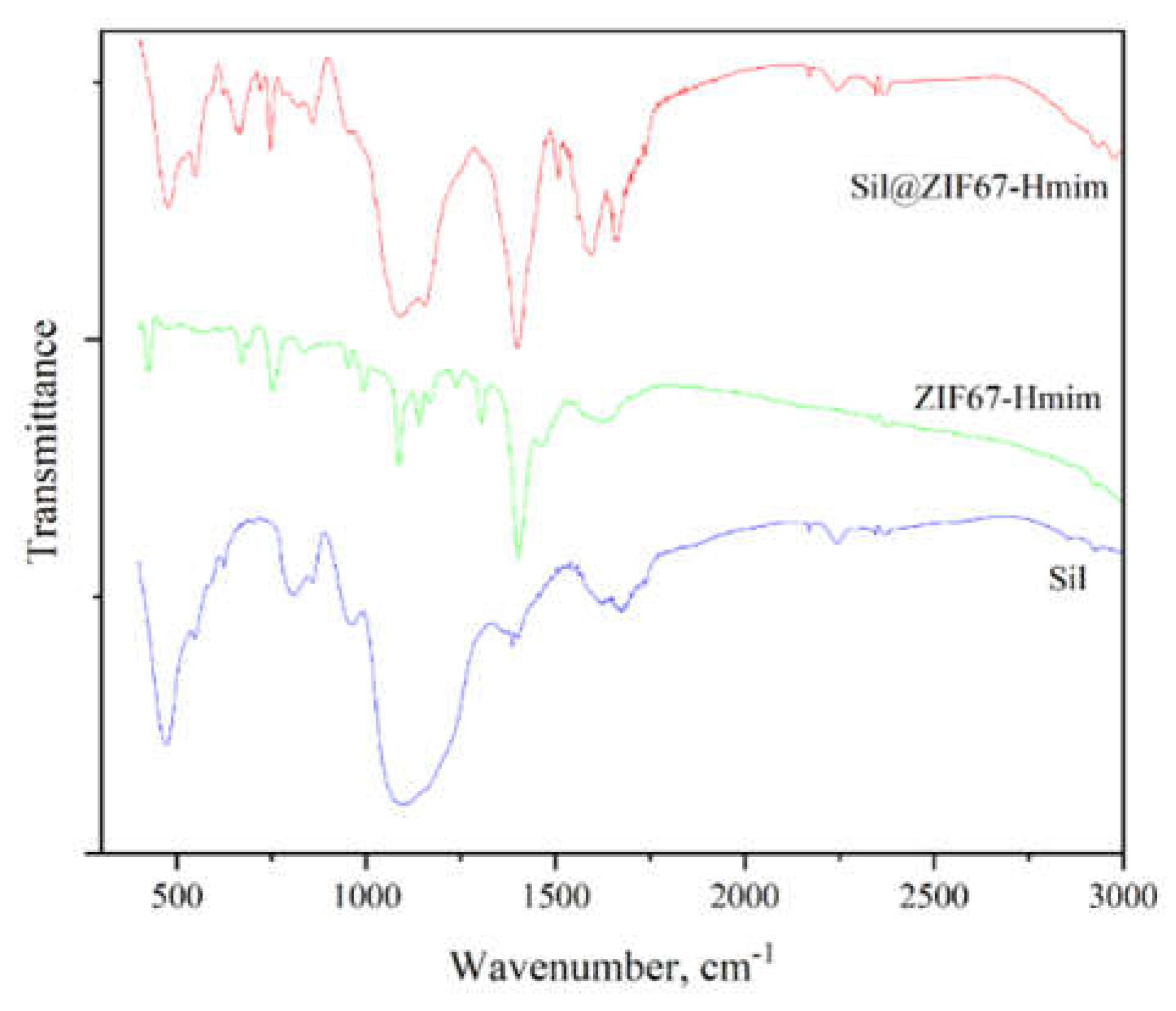

The FTIR spectra of the materials are presented in

Figure 3. Silica (Sil) shows a prominent absorption peak around 1100 cm⁻¹, which corresponds to the stretching vibration of Si-O-Si bonds. ZIF67-Hmim exhibits characteristic peaks in the range of 1400-1600 cm⁻¹, attributed to the C=N and C=C skeletal vibrations of the imidazole ring—confirming the intact presence of both ZIF67 and IL structures. For the composite Sil@ZIF67-Hmim, the Si-O characteristic peaks (1000-1200 cm⁻¹) and ZIF67-Hmim characteristic peaks (1400-1600 cm⁻¹) are observed simultaneously. This spectral overlap verifies the successful fabrication of the Sil@ZIF67-Hmim composite.

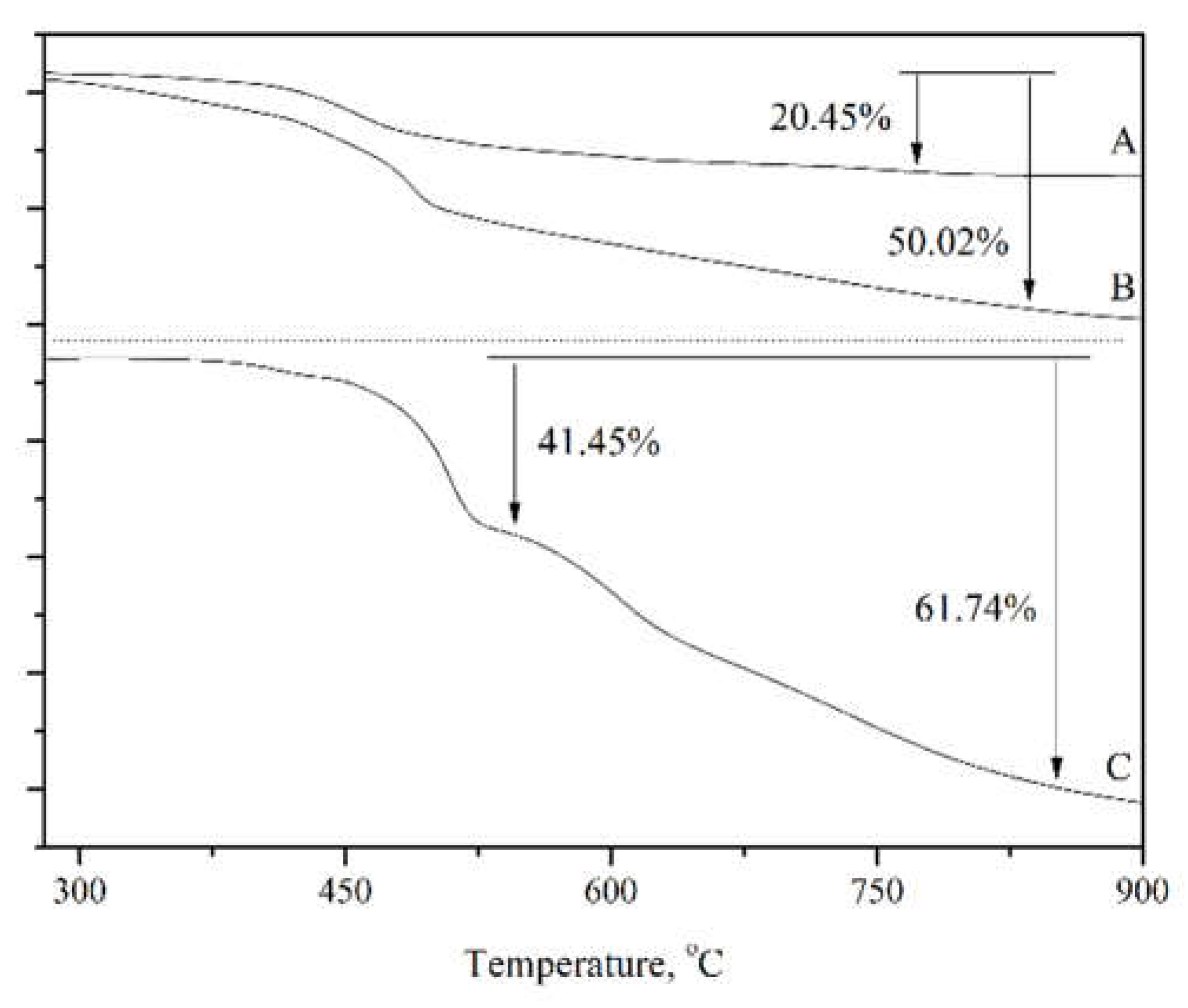

The thermal decomposition curves of Sil-IL, ZIF67-IL, and Sil@ZIF67-IL were acquired via thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), as depicted in

Figure 4. For Sil-IL (

Figure 4A), the mass started to decrease above 450 °C with a maximum mass loss of 20.45%, indicating the decomposition of the ionic liquid (IL) grafted on Sil at elevated temperatures. For ZIF-IL (

Figure 4B), a slow mass loss was observed before 460 °C, corresponding to the gradual decomposition of organic groups in ZIF67, followed by an abrupt drop which suggests the co-decomposition of organic groups and IL under high temperatures. As for Sil@ZIF67-IL (

Figure 4C), the material first underwent a 41.45% mass loss and then a further decrease to a total mass loss of 61.74%, demonstrating that ZIF67 and IL moieties modified on the Sil surface decomposed at distinct temperature intervals. These TGA results verify the successful synthesis of the target materials.

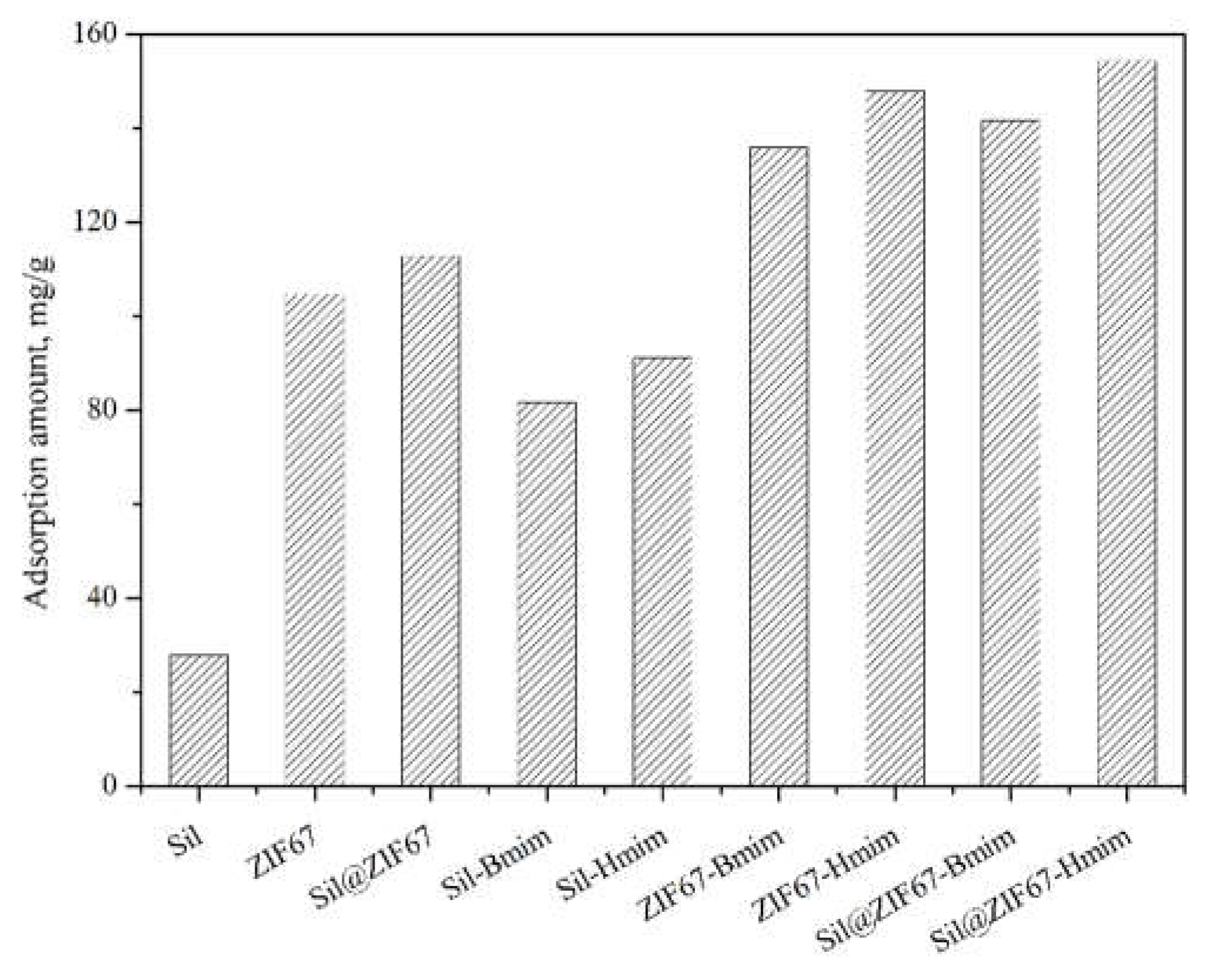

3.2. Comparison of Maximum Adsorption Capacity

Figure 5 presents the maximum adsorption capacities of all nine sorbents. The adsorption capacities of ZIF67 and Sil@ZIF67 were significantly higher than those of Sil, which can be attributed to the larger specific surface area of ZIF67 (nanoporous structure) compared to microscale silica. Additionally, Sil-Bmim and Sil-Hmim exhibited a notable increase in adsorption capacity relative to unmodified Sil, confirming the strong interactions between IL groups and (+)-catechin.

The composite sorbents (ZIF67-Bmim, ZIF67-Hmim, Sil@ZIF67-Bmim, and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim) achieved the highest adsorption capacities, as they combined two advantages: the large specific surface area of ZIF67 (providing abundant adsorption sites) and the specific interactions between IL groups and (+)-catechin. These results demonstrate that the rational design of composite sorbents—guided by the chemical structure and functional groups of (+)-catechin—effectively improves adsorption efficiency.

3.3. Adsorption Isotherm and Kinetics Studies

3.3.1. Adsorption Isotherm Studies

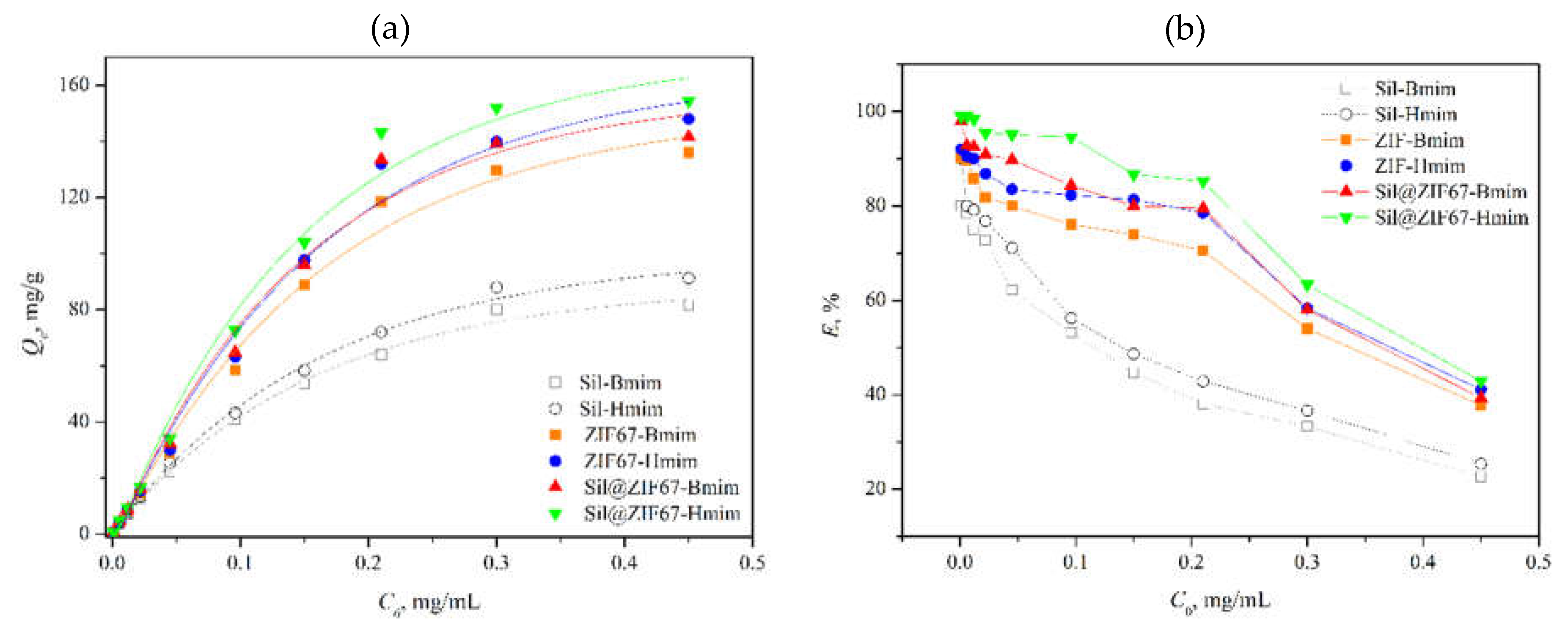

Figure 6a shows the adsorption isotherms of the six IL-modified sorbents (Sil-Bmim, Sil-Hmim, ZIF67-Bmim, ZIF67-Hmim, Sil@ZIF67-Bmim, and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim). With increasing (+)-catechin concentration, the adsorption capacity of all sorbents increased, which is consistent with the principle of mass transfer driving force: higher initial concentrations promote the diffusion of (+)-catechin molecules toward sorbent surfaces.

The mechanism underlying the enhanced adsorption of IL-modified sorbents involves three key types of interactions: (1) Hydrogen bonding between the -OH/-O- groups of (+)-catechin and the imidazole groups of ILs; (2) Ionic interactions between the negatively charged phenolic groups of (+)-catechin and the positively charged imidazolium cations of ILs; (3) π-π stacking between the benzene ring of (+)-catechin and the imidazole ring of ILs (enhancing adsorption selectivity).

The Langmuir model (R²=0.99) provided a better fit than the Freundlich model (R²=0.94), indicating that the adsorption of (+)-catechin onto the sorbents follows a monolayer adsorption mechanism—consistent with the uniform distribution of IL groups on the sorbent surface and the specific 1:1 interaction between IL groups and (+)-catechin molecules.

For Sil-Bmim and Sil-Hmim, the introduction of IL groups improved adsorption capacity, but this effect was offset by the small specific surface area of silica. Additionally, the significant decrease in

E% with increasing (+)-catechin concentration (

Figure 6b) suggests that the long alkyl chains of ILs blocked some surface -OH groups of silica during modification, reducing the number of available adsorption sites for (+)-catechin.

ZIF67-Bmim and ZIF67-Hmim exhibited higher adsorption capacities than Sil-Bmim and Sil-Hmim, owing to the large specific surface area of ZIF67. However, their adsorption capacities were lower than expected, as the dense packing of IL groups on nanoporous surface caused steric hindrance of ZIF67—preventing some IL groups from interacting with (+)-catechin.

Sil@ZIF67-Bmim and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim achieved the highest adsorption capacities among all sorbents, which can be attributed to two synergistic effects: (1) The ZIF67 coating on silica maintained a large specific surface area (provided by Co²⁺-coordinated nanopores); (2) The unblocked -OH groups on silica contributed additional adsorption sites via hydrogen bonding with (+)-catechin. When the initial (+)-catechin concentration exceeded 0.3 mg/mL, the adsorption capacity of all sorbents tended to plateau (

Figure 6a), and

E% decreased slightly (

Figure 6b). This indicates that the adsorption sites on the sorbents approached saturation. Subsequent studies (temperature effect, kinetics) focused on the four composite sorbents (ZIF67-Bmim, ZIF67-Hmim, Sil@ZIF67-Bmim, and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim) due to their higher adsorption capacities.

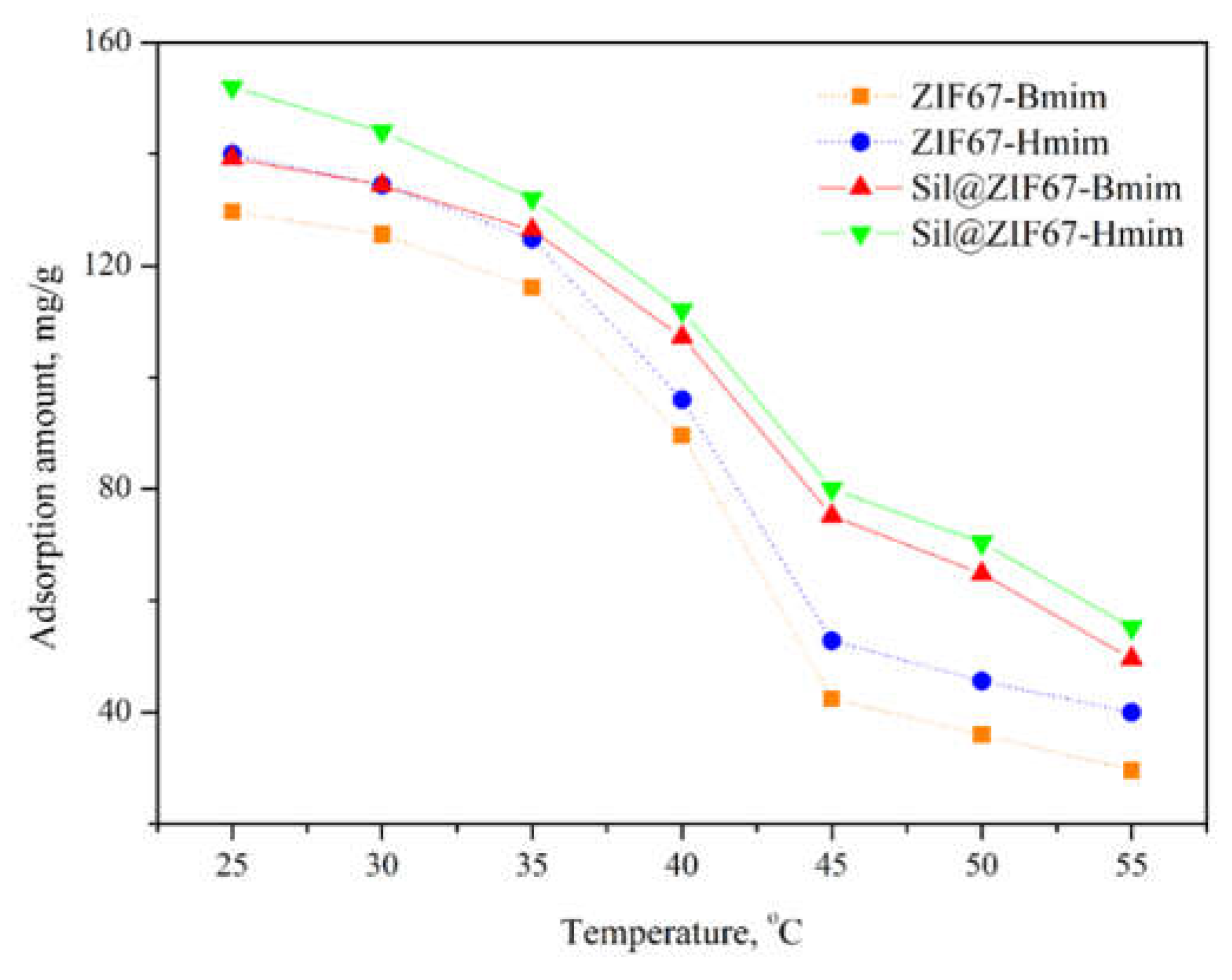

3.3.2. Effect of Temperature on Adsorption Capacity

Figure 7 shows the effect of temperature (25-55 °C) on the adsorption capacities of the four composite sorbents. With increasing temperature, the adsorption capacity of all sorbents decreased. This phenomenon can be explained by the nature of intermolecular interactions: higher temperatures increase the kinetic energy of (+)-catechin molecules, weakening the hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, and π-π stacking between (+)-catechin and sorbents [

22].

Notably, the adsorption capacity of Sil@ZIF67-Bmim and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim decreased less significantly than that of ZIF67-Bmim and ZIF67-Hmim. This is because the silica substrate improved the thermal stability of the composite sorbents: the -OH groups of silica form stronger hydrogen bonds with (+)-catechin than the IL groups of ZIF67, making them less sensitive to temperature changes. Based on these results, 25 °C was selected as the optimal temperature for subsequent experiments.

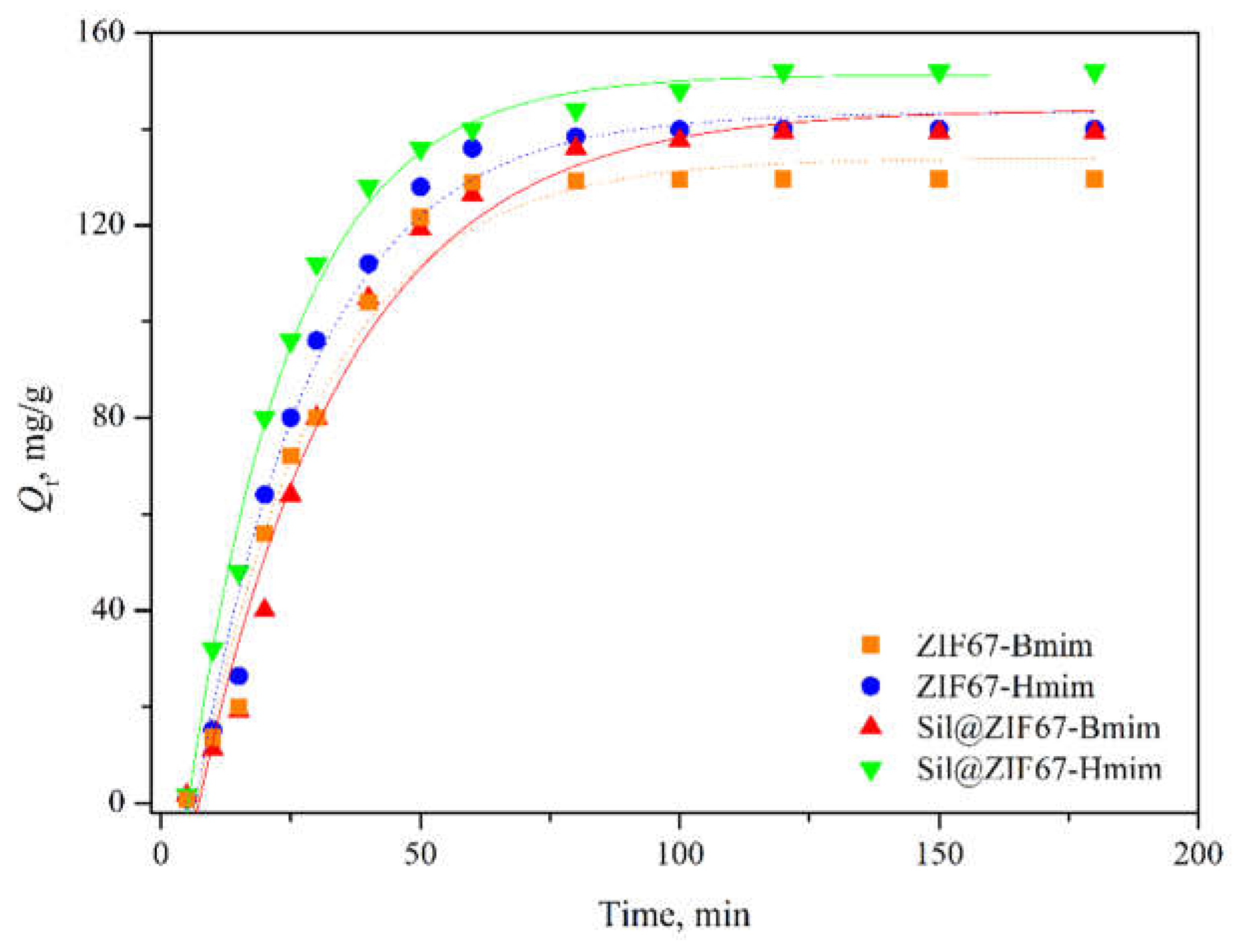

3.3.3. Adsorption Kinetics

Figure 8 shows the adsorption kinetics of the four composite sorbents. The adsorption capacity increased rapidly in the first 30 min (due to the abundance of vacant adsorption sites on sorbent surfaces) and gradually approached equilibrium. Specifically, ZIF67-Bmim and ZIF67-Hmim reached equilibrium at 80 min, while Sil@ZIF67-Bmim and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim required 120 min to reach equilibrium. The longer equilibrium time of Sil@ZIF67-based sorbents is attributed to their thicker ZIF67 coating, which increases the diffusion distance of (+)-catechin molecules into the sorbent interior.

The pseudo-second-order model (R²=0.97) provided a much better fit than the pseudo-first-order model (R²=0.84), indicating that the adsorption process is dominated by chemical adsorption (e.g., ionic interactions, hydrogen bonding) rather than physical adsorption (e.g., van der Waals forces) [

23]. Based on these results, an adsorption time of 120 min was recommended for subsequent experiments to ensure equilibrium.

Figure 8.

Adsorption kinetics of the four composite sorbents.

Figure 8.

Adsorption kinetics of the four composite sorbents.

3.4. Other Factors Affecting Adsorption Capacity

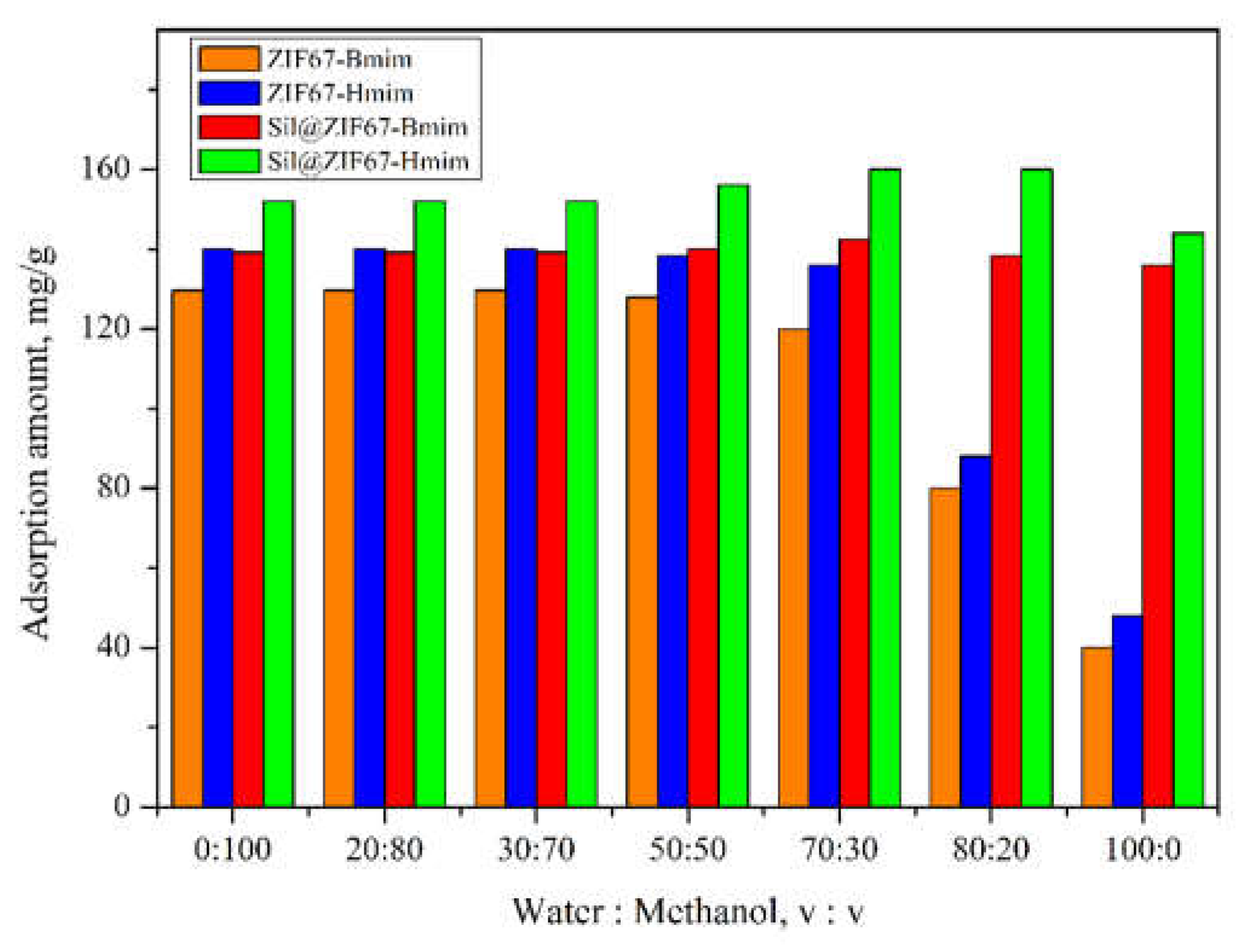

3.4.1. Effect of Water: Methanol Ratio

Figure 9 shows the effect of water/methanol ratio (0:100 to 100:0, v/v) on the adsorption capacities of the four composite sorbents. For ZIF67-Bmim and ZIF67-Hmim, the adsorption capacity decreased significantly with increasing water content. This is because water molecules disrupt the coordination bonds between Co²⁺ and imidazole ligands in ZIF67, leading to structural degradation of the sorbents [

23].

In contrast, the adsorption capacity of Sil@ZIF67-Bmim and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim first increased slightly (water/methanol was 0:100 to 70:30) and then decreased (water/methanol was 70:30 to 100:0). The initial increase can be attributed to the hydrophobicity of (+)-catechin: higher water content enhances the hydrophobic interaction between (+)-catechin and the alkyl chains of ILs, promoting adsorption. The subsequent decrease (pure water) is due to the disruption of hydrogen bonding between silica -OH groups and (+)-catechin by excess water molecules.

Based on these results, a water/methanol ratio of 70:30 (v/v) was selected as the optimal solvent system. ZIF67-Bmim and ZIF67-Hmim were excluded from further studies due to their poor stability in aqueous solutions.

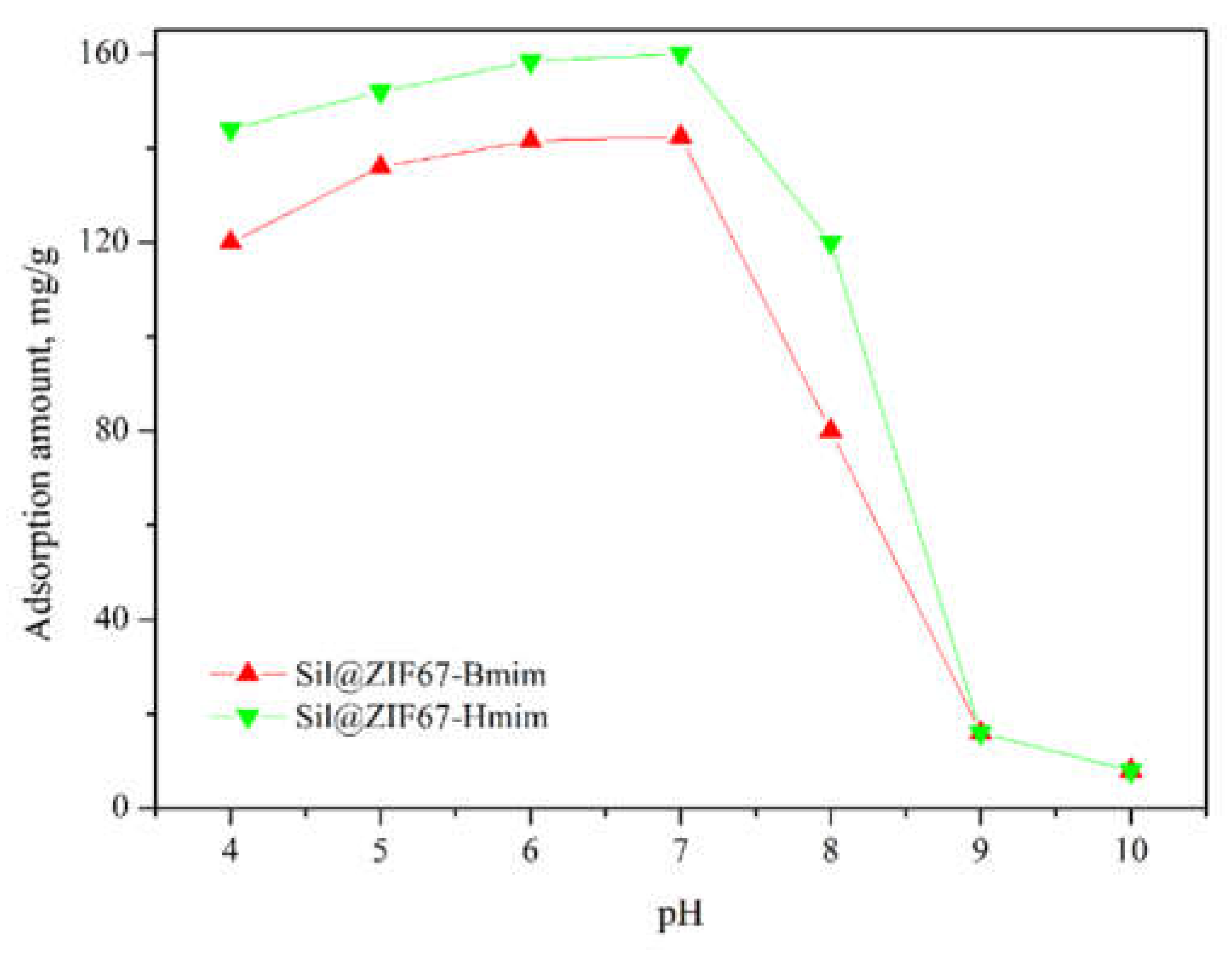

3.4.2. Effect of Solution pH

The effect of solution pH (3.0-9.0) on the adsorption capacities of Sil@ZIF67-Bmim and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim was investigated under the following conditions: water/methanol was 70:30 (v/v), (+)-catechin concentration was 0.3 mg/mL, contact time was 120 min, and temperature was 25 °C (

Figure 10).

When pH < 7.0 (acidic conditions), the adsorption capacity decreased slightly. This is because excess H⁺ ions in acidic solutions compete with (+)-catechin for adsorption sites: H⁺ binds to the imidazole groups of ILs (protonation) and the -OH groups of silica, weakening hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions with (+)-catechin. When pH > 7.0 (alkaline conditions), the adsorption capacity decreased significantly. Alkaline environments cause the deprotonation of silica -OH groups (forming SiO⁻) and the hydrolysis of Co²⁺ in ZIF67, leading to structural damage of the sorbents.

Thus, a neutral pH (7.0) was determined to be optimal for the adsorption of (+)-catechin onto Sil@ZIF67-Bmim and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim.

3.5. Stability and Reusability of Sil@ZIF67-Hmim

The adsorption capacity of Sil-Hmim, ZIF67-Hmim, and Sil@ZIF67-Hmim were tested during the repeated adsorption and desorption processes, and after 10 adsorption-desorption cycles, the adsorption capacities were decreased 2.5%, 3.6%, and 0.7%, respectively. The results revealed that the stereochemical structure of Sil@ZIF67-Hmim was more stable than other sorbents.

The 0.003 mg/L of LOD and 0.02 mg/L of LOQ proved that the analysis condition was precise enough. Then, 1.0 mg/g of standard solution was spiked into extracted solution of chocolate waste, the recoveries of SPE were analyzed and calculated using the HPLC peak areas and the correlation equation. Moreover, the relative standard deviations (RSDs) were analyzed by repeating the SPE process 5 times per day (intra-day RSD) with exactly same conditions over five consecutive days (inter-day RSD). The satisfactory recoveries of 98.1%-99.2% and RSDs of 3.2 %-4.4% revealed that the SPE conditions with Sil@ZIF67-Hmim was accurate and precise to isolate (+)-catechin from chocolate waste.

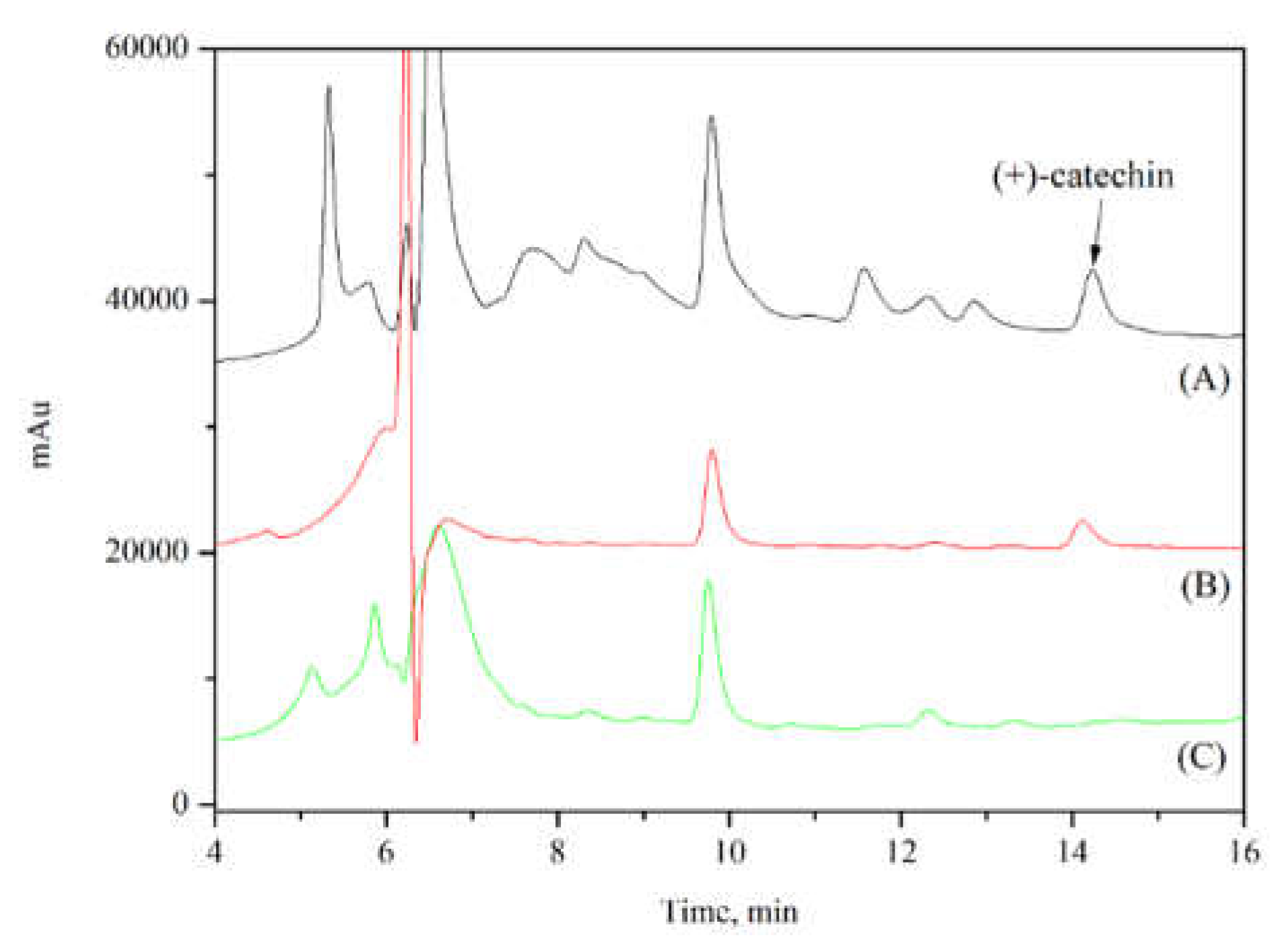

3.6. Solid-Phase Extraction of (+)-Catechin from Chocolate Waste

First, the extract obtained from chocolate waste was analyzed. HPLC injection yielded a catechin concentration of 2.24 mg/g (

Figure 11A). Subsequently, 0.05 g of the adsorbent Sil@ZIF67-Hmim was weighed out and packed into a SPE cartridge. The obtained extract was poured into the cartridge, which was then placed in an incubator at 30 °C. After standing for 60 minutes, the adsorbent was rinsed with hexane to eliminate interference from impurities. Then, methanol was used as the elution solvent to desorb (+)-catechin from the adsorbent. As shown in (

Figure 11B), the impurity peaks were basically removed. Finally, the adsorbent was rinsed again with methanol/acetic acid solution. HPLC injection results (

Figure 11C) indicated that (+)-catechin had been completely eluted. The SPE method could separate all (+)-catechin from chocolate waste, and the adsorbent could be used for subsequent repeated adsorption experiments.

3.7. Comparison with Reported Sorbents for (+)-Catechin Adsorption

After reviewing previous studies, we compared the performance of several different adsorbents for catechin adsorption. Yusoff et al. constructed a core-shell magnetite-hydroxyapatite nanoparticle (Fe₃O₄/HA) catechin delivery system with a maximum loading capacity of 110.97 mg/g [

24]. Jabbari et al. successfully prepared UIO66-NH₂@PANI nanocomposites for efficient catechin adsorption, achieving an adsorption capacity of 69.15 mg/g at pH was10 [

25]. In the previous study on Sil@ZIF8@EIM-EIM, an adsorbent developed for extracting catechins from cacao shells, the maximum adsorption capacity was 58.0 mg/g [

26]. In contrast, the maximum adsorption capacity in this study has been significantly improved. Additionally, some literature has reported other methods for extracting catechins from plants. Rezaeinejad et al. established a high-efficiency and rapid magnetic solid-phase extraction (MSPE) method based on ionic liquid-modified magnetic nanoparticles, using sample-containing narrow-bore tubes to extract catechins from grape juice, with a maximum extraction capacity of 61 mg/g [

27].

Zhu, Y. et al. prepared a CS-DES lignin aerogel via solution blending and copper block freeze-drying technology, which exhibited a maximum catechin adsorption capacity of 115.67 mg/g. After 4 cycles, the adsorption capacity decreased by 1.3% [

28]. Overall, the adsorbent successfully prepared in this study can efficiently adsorb catechins and exhibit superior adsorption performance compared with other reported adsorbents.

Table 1.

Comparison of the methods or proposed material for catechin.

Table 1.

Comparison of the methods or proposed material for catechin.

| Sorbent |

Adsorption method |

Capacity(mg/g) |

RSD(%) |

Ref |

| Fe3O4/HA |

SPE |

110.97mg/g |

- |

[24] |

| UIO66-NH2@PANI |

- |

69.15mg/g |

- |

[25] |

| Sil@ZIF8@EIM-EIM |

SPE |

58.0mg/g |

1.3%-3.2% |

[26] |

| Fe3O4@IL Nanoparticles |

MSPE |

61mg/g |

1.63% |

[27] |

| CS-LIG |

- |

115.67mg/g |

- |

[28] |

| NR/HMS |

SPE |

68.41mg/g |

- |

[29] |

| Benzimidazole/Hype |

- |

101.7mg/g |

- |

[30] |

| TSL |

SPE |

146.7mg/g |

- |

[31] |

| MIRs@CNF AG |

SPE |

101.94mg/g |

- |

[32] |

| Pectin |

- |

20.71mg/g |

- |

[33] |

4. Conclusion

In this study, an ionic liquid-modified ZIF67-coated silica sorbent (Sil@ZIF67-Hmim) was successfully synthesized for the recovery of (+)-catechin from chocolate waste. The composite sorbent exhibited high adsorption capacity (154.4 mg/g) and excellent selectivity for (+)-catechin, which was attributed to the synergistic effects of the large specific surface area of ZIF67 and the specific interactions (hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, and π-π stacking) between IL groups and (+)-catechin molecules.

Adsorption isotherm and kinetics studies revealed that the adsorption process follows the Langmuir monolayer model and pseudo-second-order kinetics, confirming chemical adsorption as the dominant mechanism. The sorbent also demonstrated excellent stability and reusability (after 10 adsorption-desorption cycles, the adsorption capacities decreased 0.7%), This work provides a novel and efficient approach for the valorization of food waste (via recovery of bioactive (+)-catechin) and highlights the potential of IL-modified MOF-silica composites for environmental and food chemistry applications.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article. Other data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Author Contributions

Mengshuai Liu and Xiaoman Li conceived the study. Mengshuai Liu performed the experiments and analyzed the data. Mengmeng Zhao and Xuyang Jiu contributed to the material preparation. Minglei Tian and Chuang Yao designed the study and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51503020).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jimenez, M.E.C.; Gabilondo, J; Bodoira, R.M.; et al. Extraction of bioactive compounds from pecan nutshell: An added-value and low-cost alternative for an industrial waste. Food Chemistry 2024, 453, 139596. [CrossRef]

- Pires, E.O.; Caleja, C.; Garcia, C.C.; et al. Current status of genus Impatiens: Bioactive compounds and natural pigments with health benefits. Trends in Food Science and Technology 2021, 117, 106-124. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.; Valentim, I.; Silva, C.A.; et al. Total phenolic content and free radical scavenging activities of methanolic extract powders of tropical fruit residues. Food Chemistry 2009, 115, 469-475. [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, V.; Gasser, J.; Polyphenols from waste streams of food industry: valorisation of blanch water from marzipan production. Phytochemistry Reviews 2020, 19, 1539-1546. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Torres, N.; Espinosa-Andrews, H.; Trombotto, S.; et al. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Optimization of Phenolic Compounds from Citrus latifolia Waste for Chitosan Bioactive Nanoparticles Development. Molecules 2019, 24, 3541. [CrossRef]

- Ettoumi, F.E.; Zhang, R.; Xu, Y.; et al. Synthesis and characterization of fucoidan/chitosan-coated nanoliposomes for enhanced stability and oral bio availability of hydrophilic catechin and hydrophobic juglone. Food Chemistry 2023, 423, 136330. [CrossRef]

- Putra, N.R.; Rizkiyah, D.N.; Qomariyah, L.; et al. Experimental and modeling for catechin and epicatechin recovery from peanut skin using subcritical ethanol. Journal of Food Process Engineering 2023, 46, e14275. [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.Y.; Zhao, C.N.; Liu, Q.; et al. Potential of Grape Wastes as a Natural Source of Bioactive Compounds Molecules 2018, 23, 2598. [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Tian, M.; Yan, X.; et al. Dual ionic liquid-immobilized silicas for multi-phase extraction of aristolochic acid from plants and herbal medicines. Journal of Chromatography A 2019, 1592, 31-37. [CrossRef]

- Ran, L.; Yang, C.; Xu, M.; et al. Enhanced aqueous two-phase extraction of proanthocyanidins from grape seeds by using ionic liquids as adjuvants. Separation and Purification Technology 2019, 226, 154-161. [CrossRef]

- Bajkacz, S.; Adamek, J.; Sobska, A. Application of Deep Eutectic Solvents and Ionic Liquids in the Extraction of Catechins from Tea. Molecules 2020, 25, 3216. [CrossRef]

- Rezaeinejad, S.; Hashemi, P.; Rahimi, A. Narrow-Bore Tube Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction Method Utilizing Ionic Liquid-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Preconcentration and Determination of Catechin in Grape Juice. Food Analytical Methods 2025, 18, 416-427. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Feng, X.; Alula, Y.; Yao, S. Bionic multi-tentacled ionic liquid-modified silica gel for adsorption and separation of polyphenols from green tea (Camellia sinensis) leaves. Food Chemistry 2017, 230, 637-648. [CrossRef]

- Pei, D.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Different ionic liquid modified hypercrosslinked polystyrene resin for purification of catechins from aqueous solution. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2016, 509, 158-165. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xue, W.; Shi, Y.; et al. MXene/MWCNTs-COOH/MOF-808-based electrochemical sensor for the detection of catechin. Microchemical Journal 2025, 215, 114339. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; et al. Ultrafine metal-organic framework @ graphitic carbon with MoS2-CNTs nanocomposites as carbon-based electrochemical sensor for ultrasensitive detection of catechin in beverages. Microchimica Acta 2025, 192, 40. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, D.; Huang, H.; et al. High-efficient electrochemical sensing platform based on MOF-doped Au/PEDOT composites toward simultaneous detection of catechin and sunset yellow in tea beverage. Electrochimica Acta 2023, 462, 142732. [CrossRef]

- Habib, N.; Gulbalkan, H. C.; Aydogdu, A.S.; et al. Toward rational design of ionic liquid/Metal-Organic Framework composites for efficient gas separations: Combining molecular modeling, machine learning, and experiments to move beyond trial-and-error. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2025, 539, 216707. [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.; Cao, X.; Zhang, N.; Cheng, F. Bifunctional ionic liquid-embedded MOFs for constructing ordered CO2-affinitive channels in CO2/N2 separation membranes. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2025, 218, 896-907. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.J.; Chen, Y.T.; Zhang, W.G.; et al. Ionic liquid modified MOF-808 for efficient adsorption and stable capture of radioactive iodine. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 392, 126731. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L. et al. Ionic liquid-functionalized metal-organic frameworks adsorbents for effective extraction of dibutyl phthalate in edible oil: A new strategy for selectivity and low cost. Food Chemistry 2025, 482, 144182. [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Tian, M.; Row, K.H.; et al. Isolation of aristolochic acid I from herbal plant using molecular imprinted polymer composited ionic liquid-based zeolitic imidazolate framework-67. Journal of Separation Science 2019, 42, 3047-3053. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, X.M.; Yan, X.M.; Tian, M.L. Solid-phase extraction of aristolochic acid I from natural plant using dual ionic liquid-immobilized ZIF-67 as sorbent. Separations 2021, 8, 22. [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, A.H.M.; Salimi, M.N.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; et al. Catechin adsorption on magnetic hydroxyapatite nanoparticles: A synergistic interaction with calcium ions. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2020, 241, 122337. [CrossRef]

- Jabbari, A.; Jabbari, M.; Zare, E.N. Synthesis and evaluation of a novel MOF/polymer nanohybrid for pH-sensitive adsorption of two natural products with similar structure. Talanta 2025, 297, 128807. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Qiao, R.; Jiu, X.; Tian, M. Solid phase extraction of (+)-catechin from cocoa shell waste using dual ionic liquid@ZIF8 covered silica. Separations 2022, 9, 441. [CrossRef]

- Rezaeinejad, S.; Hashemi, P.; Rahimi, A. Narrow-Bore Tube Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction Method Utilizing Ionic Liquid-Modified Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Preconcentration and Determination of Catechin in Grape Juice. Food Analytical Methods 2025, 18, 416-427. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Qi, B.K.; Lv, H.N.; et al. Preparation of DES lignin-chitosan aerogel and its adsorption performance for dyes, catechin and epicatechin. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 247, 125761. [CrossRef]

- Jermjun, K.; Khumho, R.; Thongoiam, M.; et al. Natural rubber/hexagonal mesoporous silica nanocomposites as efficient adsorbents for the selective adsorption of (−)-Epigallocatechin Gallate and caffeine from green tea. Molecules 2023, 28, 6019. [CrossRef]

- Pei, D.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Different ionic liquid modified hypercrosslinked polystyrene resin for purification of catechins from aqueous solutions. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2016, 509, 158-165. [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.H.; Ye, J.; Liang, H.L.; et al. Using tea stalk lignocellulose as an adsorbent for separating decaffeinated tea catechins. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100, 622-628. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, X.; et al. A compressible and underwater superelastic hydrophilic molecularly imprinted resin composite cellulose nanofiber aerogel to separate and purify catechins from tea. Chemical Engineering Journal 2023, 472, 145043. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y; Ying, D; Sanguansri; et al. Comparison of the adsorption behaviour of catechin onto cellulose and pectin. Food Chemistry 2019, 271, 733-738. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).