Submitted:

11 January 2026

Posted:

13 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

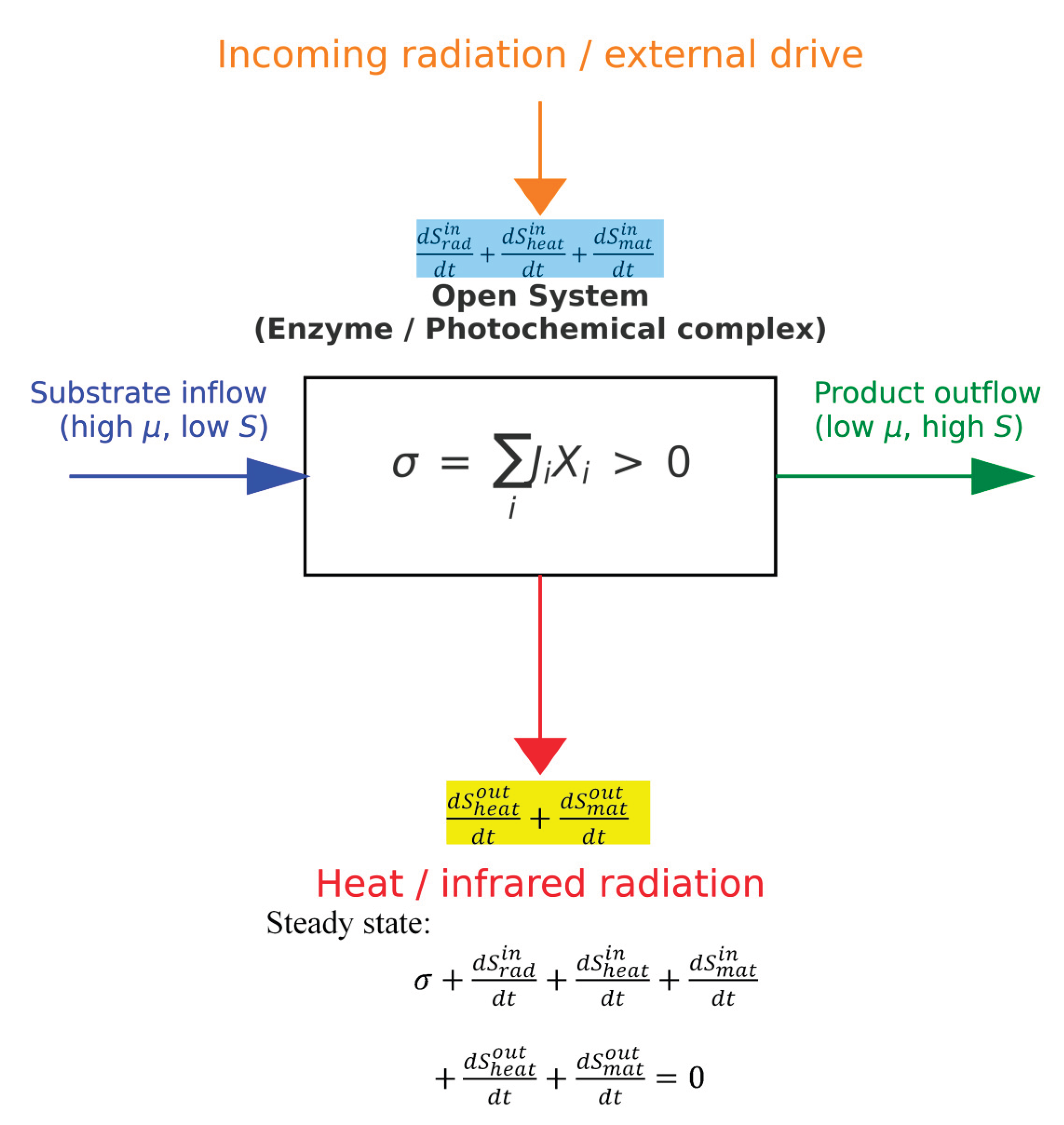

2. Tools Choice from Irreversible Thermodynamics

3. Entropy Production can Be Decomposed into Productive and Waste Parts

4. Extensions of Terrell Hill’s Theoretical Approach

5. Examples of Appplications Combining Nanothermodynamis and Entropy Production Principles in Bioenergetics

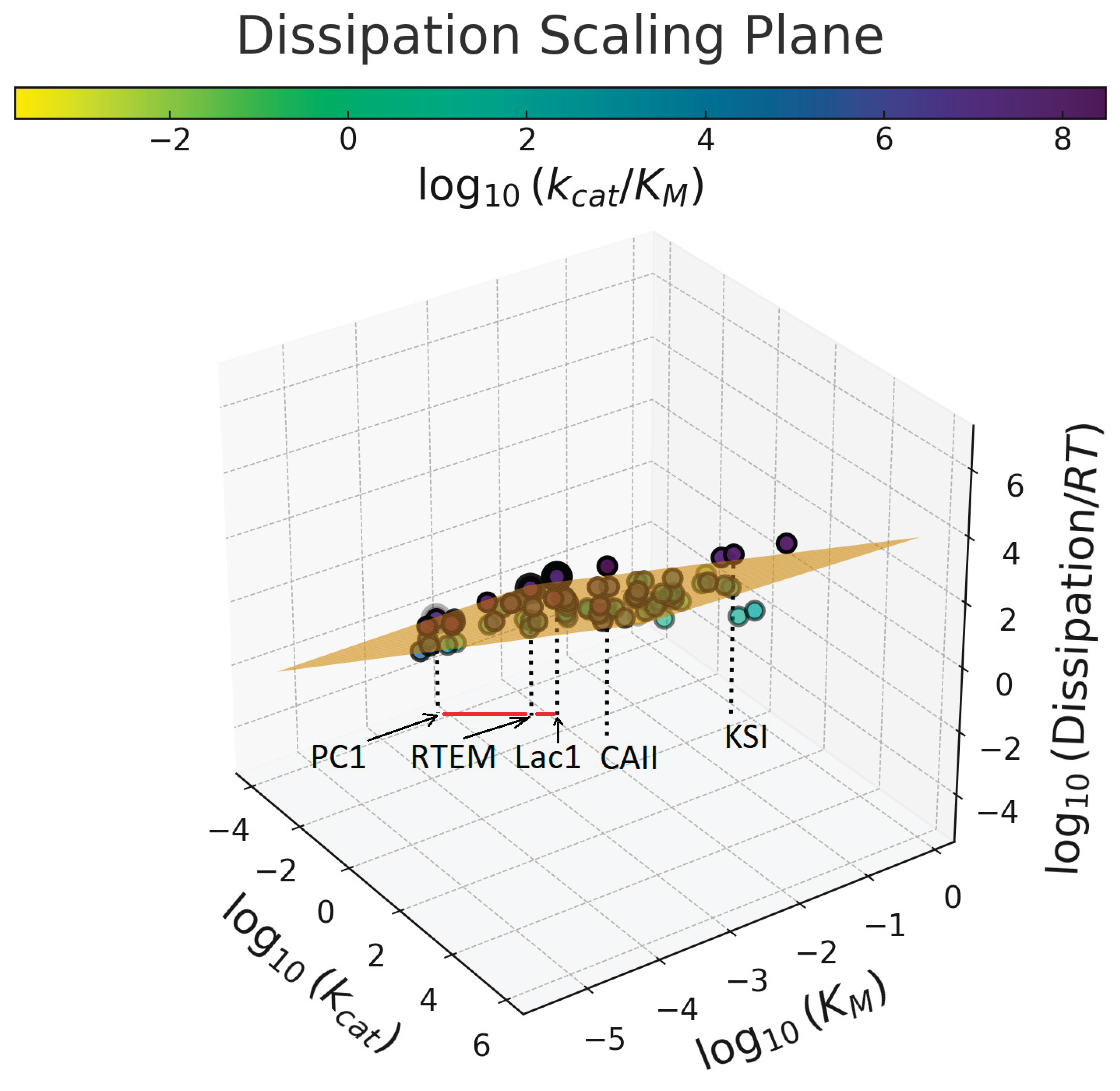

6. The Dissipation-Scaling Plane

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- England: J. Every life is on fire: How Thermodynamics explains the origins of living things. Hachette UK, 2020.

- Juretić, D. Bioenergetics: A Bridge Across Life and Universe; CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. ISBN: 978-0-8153-8838-8. [CrossRef]

- 3. von Stockar, U.; Marison, I.; Janssen, M.; Patiño, R. Biothermodynamics of live cells: A tool for biotechnology and biochemical engineering. J. Non-Equilib. Thermodyn. 2010, 35, 415–475. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.N.; Müller, F.; Marques, J.C.; Bastianoni, S.; Jørgensen, S.E. Thermodynamics in Ecology-An Introductory Review. Entropy (Basel) 2020, 22(8), 820. [CrossRef]

- Glazier, D.S. Power and Efficiency in Living Systems. Sci. 2024, 6(2), 28; [CrossRef]

- Ulanowicz, R.E.; Hannon, B.M. Life and the production of entropy. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 1987, 232, 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, U. Stochastic thermodynamics, fluctuation theorems and molecular machines. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2012, 75(12), 126001. [CrossRef]

- England, J.L. Statistical physics of self-replication. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 139, 121923. [CrossRef]

- England, J.L. Dissipative adaptation in driven self-assembly. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 919–923. [CrossRef]

- Riedel, C.; Gabizon, R.; Wilson, C.A.M.; Hamadani, K.; Tsekouras, K.; Marqusee, S.; Pressé, S.; Bustamante, C. The heat releasedduring catalytic turnover enhances the diffusion of an enzyme. Nature 2015, 517, 227–230. [CrossRef]

- Gnesotto, F.S.; Mura, F.; Gladrow, J.; Broedersz, C.P. Broken detailed balance and non-equilibrium dynamics in living systems: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2018, 81(6), 066601. [CrossRef]

- Wagoner, J.A.; Dill, K.A. Opposing pressures of speed and efficiency guide the evolution of molecular machines. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2019, 36, 2813–2822. [CrossRef]

- Lineweaver, C.H. Beyond the Second Law: Darwinian Evolution as a Tendency for Entropy Production to Increase. Entropy (Basel) 2025, 27(8), 850. [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, R. Benchmark Reaction Rates, the Stability of Biological Molecules in Water, and the Evolution of Catalytic Power in Enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 80, 645–667. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-093051.

- Edwards, D.R.; Lohman, D.C.; Wolfenden, R. Catalytic proficiency: the extreme case of S-O cleaving sulfatases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134(1), 525-531. [CrossRef]

- Warshel, A.; Sharma, P.K.; Kato, M.; Xiang, Y.; Liu, H.; Olsson, M.H.M. Electrostatic basis for enzyme catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 3210–3235. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhou, H.X. Protein Allostery and Conformational Dynamics. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116(11), 6503-6515. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.K.; Bernard, D.N.; Bafna, K.; Doucet, D. Enzyme dynamics: Looking beyond a single structure. ChemCatChem 2020, 12(19), 4704-4720. [CrossRef]

- Klinman, J.P.; Kohen, A. Hydrogen tunneling links protein dynamics to enzyme catalysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 471-496. [CrossRef]

- Kroll, A.; Engqvist, M.K.M.; Heckmann, D.; Lercher, M.J. Deep learning allows genome-scale prediction of Michaelis constants from structural features. PLoS Biol. 2021,19, e3001402. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yuan, L.; Lu, H.; Li, G.; Chen, Y.; Engqvist, M.K.M.; Kerkhoven, E.J.; Nielsen, J. Deep Learning-Based kcat Prediction Enables Improved Enzyme-Constrained Model Reconstruction. Nat. Catal. 2022, 5(8), 662−672. [CrossRef]

- Kroll, A.; Rousset, Y.; Hu, X.-P.; Liebrand, N.A.; Lercher, M.J. Turnover number predictions for kinetically uncharacterized enzymes using machine and deep learning. Nat. Commun. 2023,14, 4139. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Deng, H.; He, J.; Keasling, J.D.; Luo, X. UniKP: a unified framework for the prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters. Nat. Commun. 2023,14, 8211. [CrossRef]

- Boorla, V.S.; Maranas, C.D. CatPred: a comprehensive framework for deep learning in vitro enzyme kinetic parameters. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16(1), 2072. [CrossRef]

- Annila, A.; Baverstock, K. Genes without prominence: a reappraisal of the foundations of biology. J. R. Soc. Interface, 2014, 11, 20131017. [CrossRef]

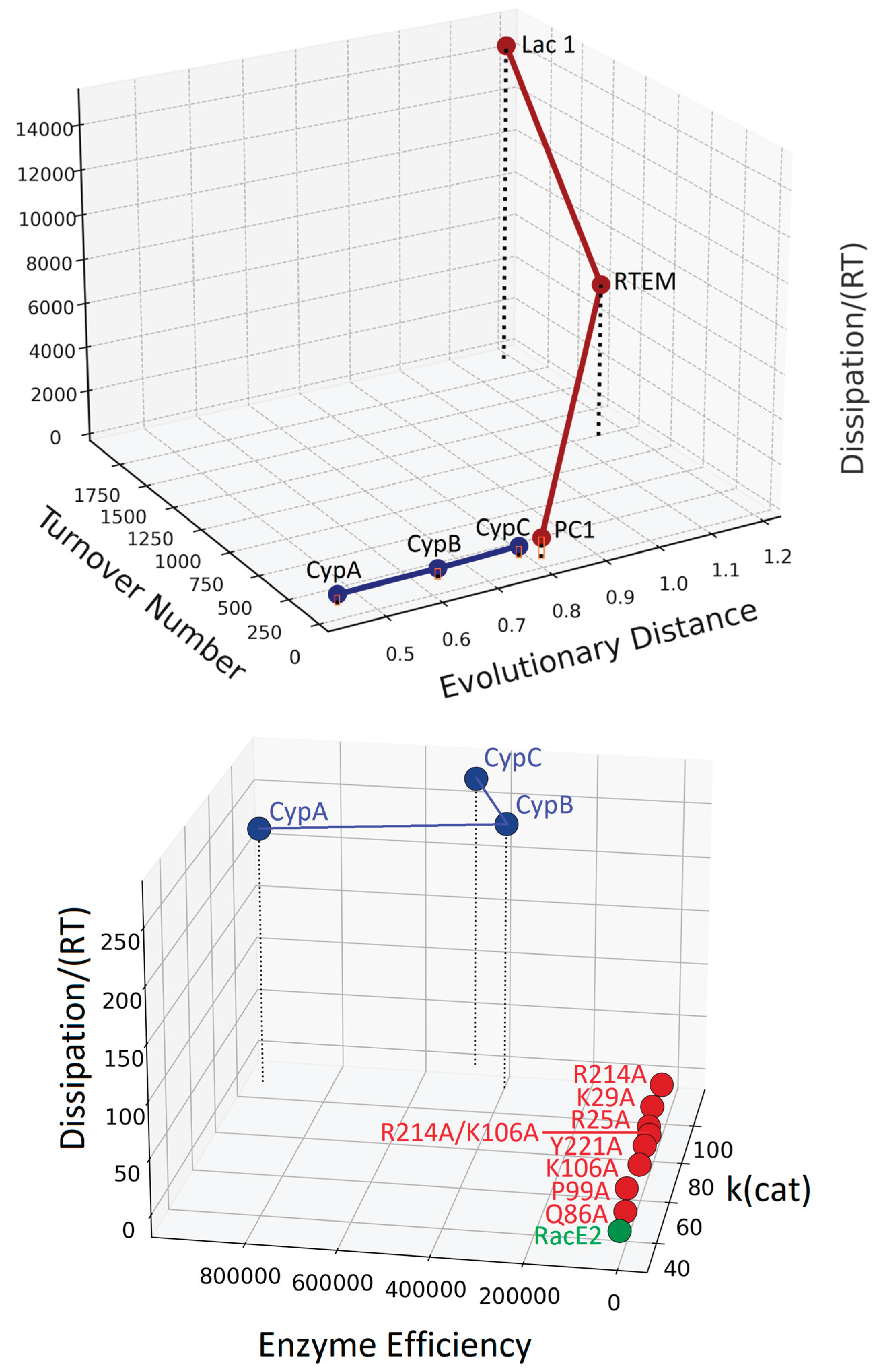

- Juretić, D. Exploring the evolution-coupling hypothesis: do enzymes’ performance gains correlate with increased dissipation? Entropy 2025, 27, 365. [CrossRef]

- Crooks, G.E. Entropy production fluctuation theorem and the nonequilibrium work relation for free energy differences. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Phys. Plasmas Fluids Relat. Interdiscip. Topics 1999, 60(3), 2721-2726. [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I. Introduction to Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1967.

- Kondepudi, D.; Prigogine, I. Modern Thermodynamics: From Heat Engines to Dissipative Structures; Johh Willey & Sons 2015, 2nd ed.: Chichester, UK. ISBN 978-1-118-371-81-7.

- Jarzynski, C. Nonequilibrium equality for free energy differences. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 2690-2693. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.2690.

- Seifert, U. Entropy production along a stochastic trajectory and an integral fluctuation theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95(4), 040602. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Van den Broeck, C. Three detailed fluctuation theorems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104(9), 090601. [CrossRef]

- Polettini, M.; Bulnes-Cuetara, G.; Esposito, M. Conservation laws and symmetries in stochastic thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. E, 2016, 94(5), 052117. [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, J.M.; Esposito, M. Work producing reservoirs: Stochastic thermodynamics with generalized Gibbs ensembles. Phys. Rev. E, 2016, 94, 02 0102. [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, J.M.; Gingrich, T.R. Thermodynamic uncertainty relations constrain non-equilibrium fluctuations. Nat. Phys., 2020, 16(1), 15–20. [CrossRef]

- Celani, A.; Bo, S.; Eichhorn, R.; Aurell, E. Anomalous thermodynamics at the microscale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109(26), 260603. [CrossRef]

- Falasco, G.; Esposito, M. Local detailed balance across scales: from diffusions to jump processes and beyond. Phys. Rev. E, 2017, 95(5), 052142. [CrossRef]

- Sagawa, T.; Ueda, M. Generalized Jarzynski Equality under Nonequilibrium Feedback Control. Phys. Rev. Lett., 2010, 104 (9), 090602. [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, J.M.; Esposito, M. Thermodynamics with Continuous Information Flow. Physical Review X, 2014, 4, 031015. [CrossRef]

- Fodor, É.; Nardini, C.; Cates, M.E.; Tailleur, J.; Visco, P.; van Wijland, F. How far from equilibrium is active matter? Phys. Rev. Lett. 2016, 117(3), 038103. [CrossRef]

- Speck, T. Stochastic thermodynamics for active matter. EPL (Europhysics Letters), 2016, 114(3), 30006. [CrossRef]

- Mandal, D.; Klymko, K.; DeWeese, M.R. Entropy Production and Fluctuation Theorems for Active Matter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017, PRL 119, 258001. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, U. From stochastic thermodynamics to thermodynamic inference. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys., 2019, 10, 171–192. [CrossRef]

- Takaki, R.; Mugnai, M.L.; Thirumalai, D. Information flow, gating, and energetics in dimeric molecular motors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119(46), e2208083119. [CrossRef]

- English, B.P.; Min, W.; van Oijen, A.M.; Lee, K.T.; Luo, G.; Sun, H.; Cherayil, B.J.; Kou, S.C.; Xie, X.S. Ever-fluctuating single enzyme molecules: Michaelis-Menten equation revisited. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2006, 2(2), 87-94. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Punia, B.; Chaudhury S. Theoretical Tools to Quantify Stochastic Fluctuations in Single-Molecule Catalysis by Enzymes and Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2022, 7(51), 47587-47600. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y.; Wang G.; Moitessier N.; Mittermaier, A.K. Enzyme Kinetics by Isothermal Titration Calorimetry: Allostery, Inhibition, and Dynamics. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020, 7, 583826. [CrossRef]

- Falconer, R.J.; Schuur, B.; Mittermaier, A.K. Applications of isothermal titration calorimetry in pure and applied research from 2016 to 2020. J. Mol. Recognit. 2021, 34(10), e2901. [CrossRef]

- Mazzei, L.; Ranieri, S.; Silvestri, D.; Greene-Cramer, R.; Cioffi, C.; Montelione, G.T.; Ciurli, S. An isothermal calorimetry assay for determining steady state kinetic and Ensitrelvir inhibition parameters for SARS-CoV-2 3CL-protease. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14(1), 32175. [CrossRef]

- Martyushev, L.M.; Seleznev, V.D. Maximum entropy production principle in physics, chemistry and biology. Phys. Rep. 2006, 426, 1–45. [CrossRef]

- Martyushev, L.M.; Celezneff, V. Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics and Scale Invariance. Entropy 2017, 19, 126;. [CrossRef]

- Essex, C. Radiation and the violation of bilinearity in the thermodynamics. Planet. Space. Sci. 1984, 32, 1035–1043. [CrossRef]

- Tomé, T.; de Oliveira, M.J. Stochastic thermodynamics and entropy production of chemical reaction systems. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 148, 224104 .

- Tomé, T.; de Oliveira, M.J. Irreversible thermodynamics and Glansdorff-Prigogine principle derived from stochastic thermodynamics. J. Stat. Mech. 2025, 2025(6), 063202.. [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.L. Free Energy Transduction in Biology: The Steady State Kinetic and Thermodynamic Formalism. Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.L.; Eisenberg E. Can free energy transduction be localized at some crucial part of the enzymatic cycle? Q. Rev. Biophys. 1981, 14(4), 463-511. [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.L. Thermodynamics of Small Systems; Dover: New York, 1994.

- Hill, T.L. Perspective: Nanothermodynamics. Nano Letters, 2001a, 1(3), 111-112.

- Hill, T.L. A Different Approach to Nanothermodynamics. Nano Letters, 2001b, 1(5), 273-275.

- Hill, T.L.; Chamberlin, R.V. Fluctuations in Energy in Completely Open Small Systems. Nano Letters, 2002, 2(6), 609-613.

- Andrieux, D.; Gaspard, P. A fluctuation theorem for currents and nonlinear response coefficients. J. Stat. Mech. 2007, P02006. [CrossRef]

- Qian, H. Hill’s small systems nanothermodynamics: a simple macromolecular partition problem with a statistical perspective. J. Biol. Phys. 2012, 38(2), 201-207. [CrossRef]

- Tanford, C. Mechanism of active transport: free energy dissipation and free energy transduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79(21), 6527-31. [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.I.; Sivak, D.A. Theory of Nonequilibrium Free Energy Transduction by Molecular Machines. Chemical Reviews, 2020, 120(1), 434–459. [CrossRef]

- Wachtel, A.; Rao, R.; Esposito, M. Free-energy transduction in chemical reaction networks: From enzymes to metabolism. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 157(2), 024109. [CrossRef]

- Leighton, M.P.; Sivak, D.A. Flow of Energy and Information in Molecular Machines. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2025, 76(1), 379-403. [CrossRef]

- Astumian, R.D. Trajectory and Cycle-Based Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Molecular Machines: The Importance of Microscopic Reversibility. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2653–2661. [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.L.; Simmons, R.M. Free energy levels and entropy production associated with biochemical kinetic diagrams. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 1976, 73(1), 95-99. [CrossRef]

- Hill, T.L. Steady-state kinetic formalism applied to multienzyme complexes, oxidative phosphorylation, and interacting enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 1976, 73(12), 4432-4436. [CrossRef]

- Schnakenberg, J. Network theory of microscopic and macroscopic behavior of master equation systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1976, 48, 571-585. [CrossRef]

- Qian, H. Cycle kinetics, steady state thermodynamics and motors-a paradigm for living matter physics. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2005, 17(47), S3783-94. [CrossRef]

- Lipowsky, R.; Liepelt, S. Chemomechanical Coupling of Molecular Motors: Thermodynamics, Network Representations, and Balance Conditions. J. Stat. Phys. 2008, 130, 39–67. [CrossRef]

- Altaner, B.; Grosskinsky, S.; Herminghaus, S.; Katthän, L.; Timme, M.; Vollmer, J. Network representations of nonequilibrium steady states: Cycle decompositions, symmetries, and dominant paths. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2012, 85(4 Pt 1), 041133. [CrossRef]

- Biddle, J.W.; Gunawardena, J. Reversal symmetries for cyclic paths away from thermodynamic equilibrium. Phys. Rev. E, 2020, 101(6-1), 062125. [CrossRef]

- Mugnai, M.L.; Hyeon, C.; Hinczewski, M., Thirumalai, D. Theoretical perspectives on biological machines. Rev. Mod. Phys., 2020, 92(2), 025001. [CrossRef]

- Samoilov, M.; Plyasunov, S.; Arkin, A.P. Stochastic amplification and signaling in enzymatic futile cycles through noise-induced bistability with oscillations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102(7), 2310-2315.. [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Beard, D.A. Metabolic futile cycles and their functions: a systems analysis of energy and control. Syst. Biol. (Stevenage) 2006, 153(4), 192-200. [CrossRef]

- Boehr, D.D. Editorial: Allosteric functions and inhibitions: structural insights. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1363100. [CrossRef]

- Rivoire, O. A role for conformational changes in enzyme catalysis. Biophys. J. 2024, 123(12), 1563-1578. [CrossRef]

- McCullagh, M.; Zeczycki, T.N.; Kariyawasam, C.S.; Durie, C.L.; Halkidis, K.; Fitzkee, N.C.; Holt, J.M.; Fenton, A.W. What is allosteric regulation? Exploring the exceptions that prove the rule! J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300(3), 105672. [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Kobayashi, C.; Yagi, K.; Sugita, Y. Toward understanding whole enzymatic reaction cycles using multi-scale molecular simulations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2025, 95, 103153. [CrossRef]

- Aykac Fas, B.; Akbas Buz, Z.E.; Haliloglu, T. Global dynamics behind enzyme catalysis, evolution, and design. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2025, 94, 103131. [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Astudillo, H.; Zarco-Zavala, M.; García-Trejo, J.J.; González-Halphen, D. Regulation of bacterial ATP synthase activity: A gear-shifting or a pawl–ratchet mechanism? FEBS J. 2021, 288(10), 3159-3163. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, M.; Zeng. Q.; Fu, X.; Chang, Z. A high-throughput genetically directed protein crosslinking analysis reveals the physiological relevance of the ATP synthase “inserted” state. FEBS J. 2021, 288(9), 2989-3009. [CrossRef]

- Brunetta, H.S.; Jung, A.S.; Valdivieso-Rivera, F.; de Campos Zani, S.C.; Guerra, J.; Furino, V.O.; Francisco, A.; Berçot, M.; Moraes-Vieira, P.M.; Keipert, S. et al. IF1 is a cold-regulated switch of ATP synthase hydrolytic activity to support thermogenesis in brown fat. EMBO J. 2024, 43(21), 4870–4891. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.F. Oxidative phosphorylation: regulation and role in cellular and tissue metabolism. J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 7023–7038.. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, A.; Vonck, J.; Mills, D.J.; Meier ,T.; Kühlbrandt, W. Structure, mechanism, and regulation of the chloroplast ATP synthase. Science 2018, 360(6389), eaat4318. [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.; Arroum, T.; Wan, J.; Pavelich, L.; Bell, J.; Morse, P.T.; Lee, I.; Grossman, L.I.; Sanderson, T.H.; Malek, M.H.; Hüttemann, M. Regulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation through tight control of cytochrome c oxidase in health and disease - Implications for ischemia/reperfusion injury, inflammatory diseases, diabetes, and cancer. Redox Biol. 2024, 78, 103426. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, N.K.; Habeck, M.; Kirchner, C.; Haviv , H.; Peleg , Y.; Eisenstein, M.; Apell, H.J.; Karlish, S.J.D. Molecular Mechanisms and Kinetic Effects of FXYD1 and Phosphomimetic Mutants on Purified Human Na,K-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290(48), 28746-28759. [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, B.M.; Leite Fontes, C.F.; Meyer-Fernandes, J.R. Molecular Basis of Na, K-ATPase Regulation of Diseases: Hormone and FXYD2 Interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25(24), 13398. [CrossRef]

- Meszéna, G.; Westerhoff, H.V. Non-equilibrium thermodynamics of light absorption. J. Phys. A.: Math. Gen. 1999, 32, 301–311. [CrossRef]

- Juretić, D.; Westerhoff, H.V. Variation of efficiency with free-energy dissipation in models of biological energy transduction. Biophys. Chem. 1987, 28, 21–34. [CrossRef]

- Juretić, D.; Županović, P. Photosynthetic models with maximum entropy production in irreversible charge transfer steps. J. Comp. Biol. Chem. 2003, 27, 541–553. [CrossRef]

- Dobovišek, A.; Županović, P.; Brumen, M.; Juretić, D. Maximum entropy production and maximum Shannon entropy as germane principles for the evolution of enzyme kinetics, in: Dewar, R.C.; Lineweaver, C.H.; Niven, R.K.; Regenauer-Lieb. K. (Eds.), Beyond the Second Law, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany, 2014, pp. 361–382. [CrossRef]

- Penocchio, E.; Rao, R.; Esposito, M., Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics of Light-Induced Reactions J. Chem. Phys. 2021, 155, 114101. [CrossRef]

- Landi, G.T.; Paternostro, M. Irreversible Entropy Production: From Classical to Quantum Rev. Mod. Phys. 2021, 93, 035008 . [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.; Juretić, D.; Županović, P. The functional design of the rotary enzyme ATP synthase is consistent with maximum entropy production. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 430, 177–182. [CrossRef]

- Juretić, D.; Simunić, J.; Bonačić Lošić, Ž. Maximum entropy production theorem for transitions between enzyme functional states and its application. Entropy 2019, 21, 743. [CrossRef]

- Martyushev, L.M.; Konovalov, M.S. Thermodynamic model of nonequilibrium phase transitions. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2011, 84(1 Pt 1), 011113. [CrossRef]

- Martyushev, L.M. Maximum entropy production principle: History and current status. Phys.-Usp. 2021, 64, 558-583. [CrossRef]

- Dobovišek, A.; Županović, P.; Brumen, M.; Bonačić-Lošić, Ž.; Kuić, D.; Juretić, D. Enzyme kinetics and the maximum entropy production principle. Biophys. Chem. 2011, 154(2-3), 49-55. [CrossRef]

- Bonačić Lošić, Ž.; Donđivić, T., Juretić, D. Is the catalytic activity of triosephosphate isomerase fully optimized? An investigation based on maximization of entropy production. J. Biol. Phys. 2017, 43, 69–86. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, H. Some extreme principles in irreversible thermodynamics with application to continuum mechanics in: Sneddon, I.N.; Hill, R. (Eds.), Progress in Solid Mechanics, vol. 4, pp. 93–193, North-Holland, Amsterdam, 1963.

- Paltridge, G.W. Climate and thermodynamic systems of maximum dissipation, Nature, 1979, 279, 630–631. [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.C. Information theory explanation of the fluctuation theorem, maximum entropy production and self-organized criticality in non-equilibrium stationary states. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2003, 36, 631–641. [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.C. Maximum entropy production and the fluctuation theorem. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2005, 38, L371–L381. [CrossRef]

- Dewar, R.C.; Maritan, A.A. Theoretical Basis for Maximum Entropy Production. In Beyond the Second Law; Dewar, R.C., Lineweaver, C.H., Niven, R.K., Regenauer-Lieb, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 49–71.

- Martyushev, L.; Seleznev, V. Maximum entropy production: application to crystal growth and chemical kinetics. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2015, 7, 23–31. [CrossRef]

- Kleidon, A. Working at the limit: a review of thermodynamics and optimality of the Earth system. Earth Syst. Dynam. 2023, 14, 861–896. [CrossRef]

- Juretić, D.; Županović, P. The free-energy transduction and entropy production in initial photosynthetic reactions, In Non-equilibrium Thermodynamics and the Production of Entropy Kleidon, A.; Lorenz, R.D., Eds.; Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany, 2005, Chapter 13, pp. 161-171. [CrossRef]

- Laland, K.N.; Uller, T.; Feldman, M.W.; Sterelny, K.; Müller, G.B.; Moczek, A.; Jablonka, E.; Odling-Smee, J. The extended evolutionary synthesis: its structure, assumptions and predictions. Proc. R. Soc. B 2015, 282: 20151019. [CrossRef]

- Müller, G.B. Why an extended evolutionary synthesis is necessary. Interface Focus 2017, 7, 20170015. [CrossRef]

- Demetrius, L.A. Directionality theory and the origin of life. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 230623. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.A.; Merondun, J.; Lečić, S.; Wolf, J.B.W. Epigenetic variation in light of population genetic practice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16(1), 1028. [CrossRef]

- Arto, A.; Stanley, S. Physical foundations of evolutionary theory. J. Non-Equilib. Thermodyn. 2010, 35, 301–321. [CrossRef]

- Goldenfeld, N.; Woese, C. Life is Physics: Evolution as a Collective Phenomenon Far From Equilibrium. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2011, 2, 375-399. [CrossRef]

- Zanetti-Polzi, L.; Daidone, I.; Iacobucci, C.; Amadei, A. Thermodynamic Evolution of a Metamorphic Protein: A Theoretical-Computational Study of Human Lymphotactin. Protein J. 2023, 42, 219–228. [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. Entropy production as the selection rule between different growth morphologies. Nature 1990, 348, 426–428. [CrossRef]

- Pal, Rajinder. On the Gouy–Stodola theorem of thermodynamics for open systems. International Journal of Mechanical Engineering Education 2017, 45(2), 194–206. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ayala, J.; Santillan, M.; Santos, M.J.; Calvo Hernandez, A.; Mateos Roco, J.M. Optimization and Stability of Heat Engines: The Role of Entropy Evolution. Entropy 2018, 20, 865. [CrossRef]

- Sheoran J.; Pant, V.; Patel, R.; Banerjee D. Evolution of the thermodynamic properties of a coronal mass ejection in the inner Corona. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, 2023,10, 27. [CrossRef]

- 122. Van Rotterdam, B. Control of Light-Induced Electron Transfer in Bacterial Photosynthesis, PhD thesis: University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998.

- Van Rotterdam, B.J.; Westerhoff, H.V.; Visschers, R.W.; Bloch, D.A.; Hellingwerf, K.J.; Jones, M.R.; Crielaard, W. Pumping capacity of bacterial reaction centers and backpressure regulation of energy transduction. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 958–970. [CrossRef]

- Wickstrand, C.; Dods, R.; Royant, A.; Neutze, R. Bacteriorhodopsin: Would the real intermediates please stand up? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1850, 536–553. [CrossRef]

- Juretić, D.; Bonačić Lošić, Ž.; Kuić, D.; Simunić, J.; Dobovišek, A., The maximum entropy production requirement for proton transfers enhances catalytic efficiency for β-lactamases. Biophys. Chem. 2019, 244, 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Perrino, A.P.; Miyagi, A.; Scheuring, S. Single molecule kinetics of bacteriorhodopsin by HS-AFM. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12(1), 7225. [CrossRef]

- Petrovszki, D.; Krekic, S.; Valkai, S.; Heiner, Z.; Dér, A. All-Optical Switching Demonstrated with Photoactive Yellow Protein Films. Biosensors (Basel) 2021, 11(11), 432. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, D.R.; Perkins, T.T. Quantifying a light-induced energetic change in bacteriorhodopsin by force spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121(7), e2313818121. [CrossRef]

- Dhanuka, A.; Flamholz, A.I.; Murugan, A.; Goyal, A. Ecosystems as adaptive living circuits. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025, Jun 29, 06.27.661910. [CrossRef]

- Juretić, D.; Bruvo Mađarić, B. Scale-invariant dissipation underlies enzyme catalytic performance. Biosystems 2025, 258, 105568. [CrossRef]

- Bisker, G.; Polettini, M.; Gingrich, T.R.; Horowitz, J.M. Hierarchical bounds on entropy production inferred from partial information. J. Stat. Mech. 2017, 093210. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, K.; Kolchinsky, A.; Dechant, A.; Ito, S. Housekeeping and excess entropy production for general nonlinear dynamics. Phys. Rev. Research 2023, 5, 013017. [CrossRef]

- Pänke, O.; Rumberg, B. Kinetic modeling of rotary CF0F1-ATP synthase: storage of elastic energy during energy transduction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1412(2), 118-128. [CrossRef]

- Whittington, A.C.; Larion, M.; Bowler, J.M.; Ramsey, K.M.; Brüschweiler, R.; Miller, B.G. Dual allosteric activation mechanisms in monomeric human glucokinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112(37), 11553-11558. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.E.; Navedo, M.F.; Binder, M.D.; Santana, L.F. Mechanisms and physiological implications of cooperative gating of clustered ion channels. Physiol. Rev. 2021, 102(3), 1159–1210. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Shahul Hameed, U.F.; Hoffmann, T.D.; Kurze, E.; Sun, G.; Steinchen, W.; Nicoli, A.; Di Pizio, A.; Kuttler, C.; Song C. et al. β-Carotene alleviates substrate inhibition caused by asymmetric cooperativity. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16(1), 3065. [CrossRef]

- Punekar, N.S. Regulation of Enzyme Activity. In: ENZYMES: Catalysis, Kinetics and Mechanisms. Springer, Singapore, 2025, pp 527-561. [CrossRef]

- Bordel, S.; Nielsen, J. Identification of flux control in metabolic networks using non-equilibrium thermodynamics. Metab. Eng. 2010, 12(4), 369-377. [CrossRef]

- Vallino, J.J. Ecosystem biogeochemistry considered as a distributed metabolic network ordered by maximum entropy production. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365(1545), 1417-1427. [CrossRef]

- Unrean, P.; Srienc, F. Metabolic networks evolve towards states of maximum entropy production. Metab. Eng. 2011, 13(6), 666-673. [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Pablo Sartori, P.; Neumann, S.; Sourjik, V.; Tu, Y. The energy-speed-accuracy tradeoff in sensory adaptation. Nat. Phys. 2012, 8, 422–428. [CrossRef]

- Weber, J.K.; Shukla, D.; Pande, V.S. Heat dissipation guides activation in signaling proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112(33), 10377-10382. [CrossRef]

- Britton, S.; Alber, M.; Cannon, W.R. Enzyme activities predicted by metabolite concentrations and solvent capacity in the cell. J. R. Soc. Interface 2020, 17, 20200656. [CrossRef]

- King E.; Holzer J.; North J.A.; Cannon, W.R. An approach to learn regulation to maximize growth and entropy production rates in metabolism. Front. Syst. Biol. 2023, 3, 981866. [CrossRef]

- Dobovišek, A.; Blaževič, T.; Kralj, S.; Fajmut, A. Enzyme cascade to enzyme complex phase-transition-like transformation studied by the maximum entropy production principle. Cell Reports Physical Science, 2025, 6(2), 102400. [CrossRef]

- Sawada, Y.; Daigaku, Y.; Toma, K. Maximum Entropy Production Principle of Thermodynamics for the Birth and Evolution of Life. Entropy 2025, 27, 449. [CrossRef]

- Srienc, F.; Barrett, J. Predicting the Rate Structure of an Evolved Metabolic Network. Metabolites 2025, 15(3), 200. [CrossRef]

- Juretić, D.; Bonačić Lošić, Ž. Theoretical improvements in enzyme efficiency associated with noisy rate constants and increased dissipation. Entropy 2024, 26, 151. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.A. Enzyme recruitment in evolution of new function. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1976, 30, 409-25. [CrossRef]

- Copley, S.D. Toward a systems biology perspective on enzyme evolution. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287(1), 3-10. [CrossRef]

- Ambler, R.P. The Amino Acid Sequence of Staphylococcus aureus Penicillinase. Biochem. J. 1975, 151, 197–218. [CrossRef]

- Thatcher, D.R. The Partial Amino Acid Sequence of the Extracellular P-Lactamase I of Bacillus cereus 569/H. Biochem. J. 1975, 147, 313–326. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, H.; Martin, M.T.;Waley, G. beta-lactamases as fully efficient enzymes. Determination of all the rate constants in the acyl-enzyme mechanism. Biochem. J. 1990, 266, 853–861.

- Mehboob, S.; Guo, L.; Fu, W.; Mittal, A.; Yau, T.; Truong, K.; Johlfs, M.; Long, F.; Fung, L. W.-M.; Johnson, M.E. Glutamate racemase dimerization inhibits dynamic conformational flexibility and reduces catalytic rates. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 7045–7055. [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, M. Body size and metabolic rate. Physiol. Rev. 1947, 27, 511–541. https://doi. org/10.1152/physrev.1947.27.4.511.

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 2019, 20 (4), 1160–1166. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 2015, 32 (1), 268–274. [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nature Methods, 2017, 14 (6), 587–589. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 2018, 35 (2), 518–522. [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, M.; Gascuel, O. Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: A fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Systematic Biology, 2006, 55 (4), 539–552. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, K.; Bhattacharyya, K. States with identical steady dissipation rate in reaction networks: A non-equilibrium thermodynamic insight in enzyme efficiency. Chem. Phys. 2014, 438, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, P.; Li, M.; Shi, Y.; Hasman, E.; Wang, B.; Chen, X. Brownian spin-locking effect Nat. Mater 2025, Nov 18. Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Lane, N.; Martin, W.F. The origin of membrane bioenergetics. Cell 2012, 151, 1406–1416. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-E.; Okumura, T.; Ooka, H; Adachi, K.; Hikima, T.; Hirata , K.; Kawano, Y.; Matsuura, H.; Yamamoto Masaki, Yamamoto, Masahiro et al. Osmotic energy conversion in serpentinite-hosted deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15(1), 8193. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Oriola, D.; Grill, S.W. Nonequilibrium physics in biology. Reviews of Modern Physics, 2019, 91(4), 045004. [CrossRef]

- Niebel, B.; Leupold, S.; Heinemann, M. An upper limit on Gibbs energy dissipation governs cellular metabolism. Nat. Metab. 2019, 1, 125–132 . [CrossRef]

- Wortel, M.T.; Peters, H.; Hulshof, J.; Teusink, B.; Bruggeman, F.J. Metabolic enzyme cost explains variable trade-offs between microbial growth rate and yield. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1008656. [CrossRef]

- Mehdi Molaei, M.; Redford, S.A.; Chou, W.-H.; Scheff, D.; de Pablo,J.J.; Oakes, P.W.; Gardel, M.L. Measuring response functions of active materials from data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120(42), e2305283120. [CrossRef]

- Bo, S.; Celani, A.; Eichhorn, R.; Aurell, E. Stochastic Thermodynamics of Enzyme Catalysis: Efficiency, Speed, and Dissipation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 098401. [CrossRef]

- Umeda, K.; Nishizawa, K.; Nagao, W.; Inokuchi, S.; Sugino, Y.; Ebata, H.; Mizuno, D. Activity-dependent glassy cell mechanics II: Nonthermal fluctuations under metabolic activity. Biophys. J. 2023, 122(22), 4395-4413. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).