1. Introduction

Bird migration phenology can be influenced by seasonal variation in food availability and weather conditions such as temperature, wind, and precipitation [

1]. Furthermore, in the last decades, bird migration phenology has been adjusting to temperature changes due to global warming [

2], resulting in shifts in breeding and migration periods [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Climate-related changes in spring migration timing have been described for many migratory bird species in Europe and North America as carry-over effects of changes in environmental conditions, such as availability of food resources or climatic conditions in different areas they visit at subsequent stages of their migratory life [

8,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Climate change may also influence multispecies interactions [

9,

19,

20,

21], which are crucial for regulating and maintaining healthy ecosystems [

9,

22]. Changes in such interactions may vary across species and their relationships at different levels of the trophic chain, as organisms respond differently to changes in temperature or other environmental factors [

9]. Predators are vital in regulating the population of their prey, making predator-prey interactions one of the most important in the trophic chain, at both the population and ecosystem level [

9,

23]. Climate change may influence the population dynamics of both predators and prey in the following ways: changes in range, population density, behaviour and phenology [

9]. Multiannual data (1985–2005) from the Netherlands showed changes in the food chain at three levels: from caterpillars (an average 0.25 day delay compared to the budding of the plants they fed on), passerines (an average 0.5 day delay in relation to the peak in caterpillar abundance), to predators, among which the Eurasian Sparrowhawk

Accipiter nisus (hereafter Sparrowhawk) showed the greatest mismatch between its breeding season and the hatching time of its passerine prey [

9,

24]. Raptor migration routes may have evolved in tandem with routes of their prey species [

25,

26]. The mismatch in the timing of predator and prey phenology, caused by climate warming, may have a greater impact on prey species, which shift spring migration and breeding earlier in response to changes in temperature and earlier availability of their plant and insect food, resulting in a temporal “escape” from the predator [

24]. In North America, advancement in spring migration timing related to climate change has been observed for five out of the ten most abundant raptor species [

8]. Furthermore, temperature changes in Europe influenced autumn migration dates of seven short-distance migrant raptor species, including the Sparrowhawk, which adjusted the timing of autumn migration to temperatures during their breeding and non-breeding seasons during a 30-year study (1980–2010) in Western Europe [

27]. In the Baltic region, long-term phenological shifts in the timing of spring migration since the 1960s until present were related to increased winter and spring temperatures at non-breeding grounds, for the Song Thrush

Turdus philomelos [

28], Robin

Erithacus rubecula [

29], Eurasian Wren

Troglodytes troglodytes [

18] and Chaffinch

Fringilla coelebs [

30]. Recently, changes in spring migration timing have also been revealed in the Sparrowhawk [

31,

32]. With this in mind, we expect that raptors, including the Sparrowhawk, should adjust their spring migration dates to changes in migration timing of their prey species, which occur in response to changes in temperature.

Predators can be classified based on their prey selection. Specialists hunt a narrow range of species and are primarily responsible for regulating the population of their prey species. Generalists hunt on wider range of prey species, and a decline in the population of one prey species does not pose a threat to them, as they can prey on other species according to their abundance [

9,

33]. As generalist predators hunt a larger number of species, their population size should be more stable over time, and they ought to exhibit a higher rate of adaptability to climate change than specialists [

9,

34]. Despite higher population stability, generalists may also be affected by changes in the diversity or abundance of their prey, and the substitution of prey species can affect their interactions with other prey species or predators [

9,

35,

36]. For example, Eleonora’s Falcon

Falco eleonorae is a generalist bird of prey that, by delayed breeding season, relies on passerines and other small birds migrating in autumn through the Mediterranean basin or other areas, to raise offspring [

37,

38,

39]. In these raptors, changes in autumn migration phenology of prey species can cause changes in behaviour and shifts in the timing of breeding. However, knowledge of the responses of generalist predators to changes in the phenology of their prey is still limited [

9].

Thus, we aimed to study interactions between Sparrowhawks and selected passerine prey species they hunt during stopovers on spring migration along the Hel Peninsula on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which concentrates the passage of both predatory and prey migrant birds. We aimed to identify relationships between the timing of spring migration of this predator and its prey species within selected springs, and over the 40 years we studied, for Sparrowhawks as a whole, and for its age and sex groups. We also set out to determine if temperatures on Sparrowhawk’s wintering grounds, migration routes and locally at Hel were related to the annual variation in its migration timing. Lastly, we attempted to answer the question: considering that the selected prey species change the timing of their spring passage over the years, has Sparrowhawk, as a generalist predator, followed suit? We aim to answer those questions, which, to the best of our knowledge, were not addressed for the Sparrowhawk before.

1. Materials and Methods

1.1. Study Site and Methods of Fieldwork

The data used in this study were collected during the spring migration of birds (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021, and in 2024, at the Hel bird ringing station, located on the Hel Peninsula (N Poland) (

Figure 1), within the Operation Baltic Project [

40]. Between 1982 and 2024, the station moved within 5 km along the Hel Peninsula, adjusting to the growth of forest, from location HL.03 near the village of Chałupy, where the station operated in 1982–1999, to location HL.04 near Kuźnica, where it has operated since spring 2000 to this day (

Figure 1). The vicinity of the ringing station consisted of a pine forest with willow and rugose

Rosa rugosa shrubs in which the birds were captured in mist nets [

41]. Passerines were caught in mist nets of 16–19 mm mesh and lengths of 7 m and 12 m, whereas most Sparrowhawks were caught in nets with larger mesh (40–80 mm) and 12 m-long [

42]. The number of mist nets of each type at the Hel station was stable throughout each spring season, but varied from 36 to 58 between the years. After extracting birds from the nets, they were ringed, their species, sex and age (if possible) were determined, and measured, according to the Operation Baltic protocol [

42]. Species, age and sex of each bird were identified by a qualified bird ringer, according to plumage features, according to identification guides [

43,

44].

To determine the Sparrowhawk diet during spring migration and select its bird prey species for further analysis, we collected pluckings and observed Sparrowhawk’s attacks on other birds along the Hel Peninsula, which is a stopover place for the raptor and its prey species. Pluckings and observations were collected in 2024 between 26 March and 12 May near the Hel ringing station (

Figure 1) by KC and station’s volunteers, during regular net checks, in a pine sapling stand near the station where no mist nets were opened but which was an attractive place for bird predators, and along ca 5 km path in the forest between the villages of Chałupy and Kuźnica (

Figure 1).

1.2. Study Species

The Eurasian Sparrowhawk

Accipiter nisus is a medium-sized bird of prey, common across Europe and Asia, that primarily hunts passerine birds [

45,

46]. The main habitat of this species are woodlands with pine and spruce, where it builds nests, close to open areas, where it hunts. The breeding grounds of the Sparrowhawk extend across northern Europe, Russia and central Asia, and its non-breeding grounds span central and southern Europe, Africa, the Middle East, southern Asia, India, and south-western China [

46] (

Figure 2). The Sparrowhawk is the most commonly caught bird of prey during spring ringing at the Hel station. We focus on the populations of Sparrowhawk that migrate in spring to the north, from their wintering grounds in southwestern Europe, through the southern coast of the Baltic, including the Hel station, towards their breeding grounds in Finland, Sweden, Norway and western Russia, as indicated by ringing recoveries (

Figure 2) [

48]. Sparrowhawks can breed already at the end of their first year of life [

49]. This species exhibits clear sexual dimorphism in plumage and size, with adult females being larger than males by up to 25%, and reaching a size of the Eurasian Goshawk

Astur gentilis [

49]. Male Sparrowhawk’s diet consists of prey of a weight 40–120 g, and females can catch prey up to 500 g [

49]. The diversity of species in the Sparrowhawk’s diet depends on the local availability of species [

45]. In most European countries, the Sparrowhawk is a species of Least Concern (LC) status, with stable or increasing population numbers [

50].

1.3. Criteria for selecting prey species for analysis

Most studies on Sparrowhawks’ diet are focused on the breeding period, when birds form 77.2–97.4% of their prey items [

35,

45,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. We selected the bird species analysed in this study as the Sparrowhawk prey based on these studies (

Table 1,

Table 2), and on analysis of Sparrowhawk pluckings collected during its spring migration at the Hel Peninsula in 2024. All prey species we selected for analysis, which are briefly described below (

Table 1), belong to the order Passeriformes.

1.4. Datasets and Methods of Their Collection

1.4.1. Collection of Pluckings and Observations of Sparrowhawk Attacks

In 2024, from 26th March to 12th May, 48 pluckings of Sparrowhawks were collected around the Hel station. During this period, attacks on birds by the Sparrowhawk were also observed near mist-nets by volunteers, or this predator was caught in the mist-nets along with the prey. These observations, along with information on the prey species, age and sex of the predator (if possible), and the location of observation, were recorded at the ringing station. During the study period, 16 such attacks by Sparrowhawk were observed.

Pluckings are feathers remaining after birds of prey or owls pluck them out of their prey (also called pluckings) [

63,

64]. Pluckings by birds can be distinguished from those left by mammal predators by the tooth marks and damage they do to feathers, while birds’ bills and claws leave only small holes in feather quills [

63]. Pluckings by birds of prey can be distinguished between those left by the Eurasian Goshawk and by the Sparrowhawk, as the latter species mainly plucks its prey, smaller than for the first species, on a log, stump, or other elevated location, among leaves in a tree, in an old nest [

63] or near a tree in a dense forest [

65]. The Sparrowhawk plucks its prey in one spot, pulling out feathers one by one, so they are concentrated in one place [

65]. In contrast, when the Eurasian Goshawk plucks feathers, it changes position and moves, scattering the feathers, and it plucks feathers more often in tufts than singly [

65].

Male Sparrowhawks mostly feed on prey that weigh 40 – 120 g, and female Sparrowhawks prey upon species up to even 500 g [

49], so pluckings of larger and heavier species found in the study area, like Long-tailed Duck

Clangula hyemalis, were not considered in the analysis. Because other birds of prey, such as the Eurasian Goshawk, occurred in the area, as well as various species of owls and mammals, the entire appearance of the plucking site and the feather arrangement were examined by KC, either personally or based on photos provided by volunteers. The species of the predator and prey were identified by KC’s own observations and knowledge, using the Featherbase website [

66].

1.4.2. Materials Collected During Bird Ringing

For all six study species, we extracted from the Operation Baltic database the dates of their first capture at the Hel station during the springs 1982–2021, and for the Sparrowhawk, also age and sex of the analysed individuals (

Table 3). For the Sparrowhawk, for each sex, we merged birds aged in the field as juveniles and immatures, which were all in spring in their second calendar year of life, into the age group of “immatures” (young birds). Sparrowhawks that were aged as adults (older than two years), or occasionally as birds in their third year of life, were also merged as “adults”, also separately for each sex. For the five passerine species, we analysed immatures and adults combined (

Table 3).

1.4.3. Temperatures Along Sparrowhawk Spring Migration Routes

To determine if the timing of Sparrowhawks’ passage at Hel was related to temperatures at their wintering grounds and migration routes, we used temperatures in February–April in regions K1 and K2, defined by squares of coordinates (

Figure 2). We used temperatures from February and March in the square K1, including the area of south-western Europe where Sparrowhawks ringed on the Polish coast of the Baltic Sea were recovered (

Figure 2), as a proxy for temperatures at their departures from wintering grounds and along spring migration routes. We used the temperatures in April in a one-degree grid square K2 that includes the Hel station, to reflect conditions on their arrival at that location. We downloaded daily mean temperatures within the selected ranges of coordinates (

Figure 2) from the ERA5 dataset using the Climate Explorer facility by the World Meteorological Organisation [

67]. We then averaged these daily temperatures for the selected months. Temperatures from the same months in areas K1 and K2 were strongly correlated (

Table A1), thus we avoided using them in one model.

1.4.4. Statistical Analysis

Based on the daily ringing data for each species, we summed up the number of individuals captured each day of the spring season (26 March – 15 May) in subsequent years from 1982 to 2021. For the Sparrowhawk, we also summed up the daily numbers of individuals ringed in four age and sex groups separately: adult males, adult females, immature males, and immature females. For each species, using these daily totals, we calculated the percentage of birds captured on each day of the season relative to the total number of individuals caught that spring, to draw the daily migration dynamics in each season. For Sparrowhawk, we also calculated and drew daily migration dynamics for each age/sex group. Then, to draw the many-year average daily migration dynamics for each age/sex group of Sparrowhawk, we calculated the average proportion of birds captured during 1982–2021 each day of the spring season. We obtained the multi-year average spring migration dynamics for each studied species in the same way.

To determine if Sparrowhawk migration coincided with the migration period of prey, for each prey species, and for each age/sex group for Sparrowhawk, we calculated the date (the day number in the year, 1 January = day 1) on which 25% (q25) of individuals were ringed during each spring in 1982–2021. We repeated the same procedure for 50% (q50 = median) and 75% (q75) of the ringed birds. To compare the dates of passage of subsequent quartiles (q25, q50, q75) of the ringed birds between the Sparrowhawk and its prey species, we run three multiple regression models, one for each quartile. In each model, the dates of the selected quartile over 1982–2021 for the Sparrowhawk (all individuals jointly) were the response variable, and analogous dates for the five prey species were explanatory variables. Then, we repeated this modelling procedure for each age/sex group of the Sparrowhawk. We applied the “all subsets regression” procedure and selected the best model according to the Akaike Information Criteria using the Generalised Linear Models (GLM) in Statistica 13.3 [

68]. To relate the timing of passage of Sparrowhawks to temperatures at their wintering grounds and migration routes, for each sex and age group we run a multiple regression model, with the median dates (q50) of their spring passage in 1982-2021 as the response variable and the monthly temperatures of February–March in the square K1, and of April in the square K2, as explanatory variables. Analogously to the previous multiple regression models, we selected the best model using “all subsets regression” and the Akaike Information Criteria. These methods are analogous to those used in other studies of the long-term data on bird migration from the Operation Baltic project [

18,

69,

70].

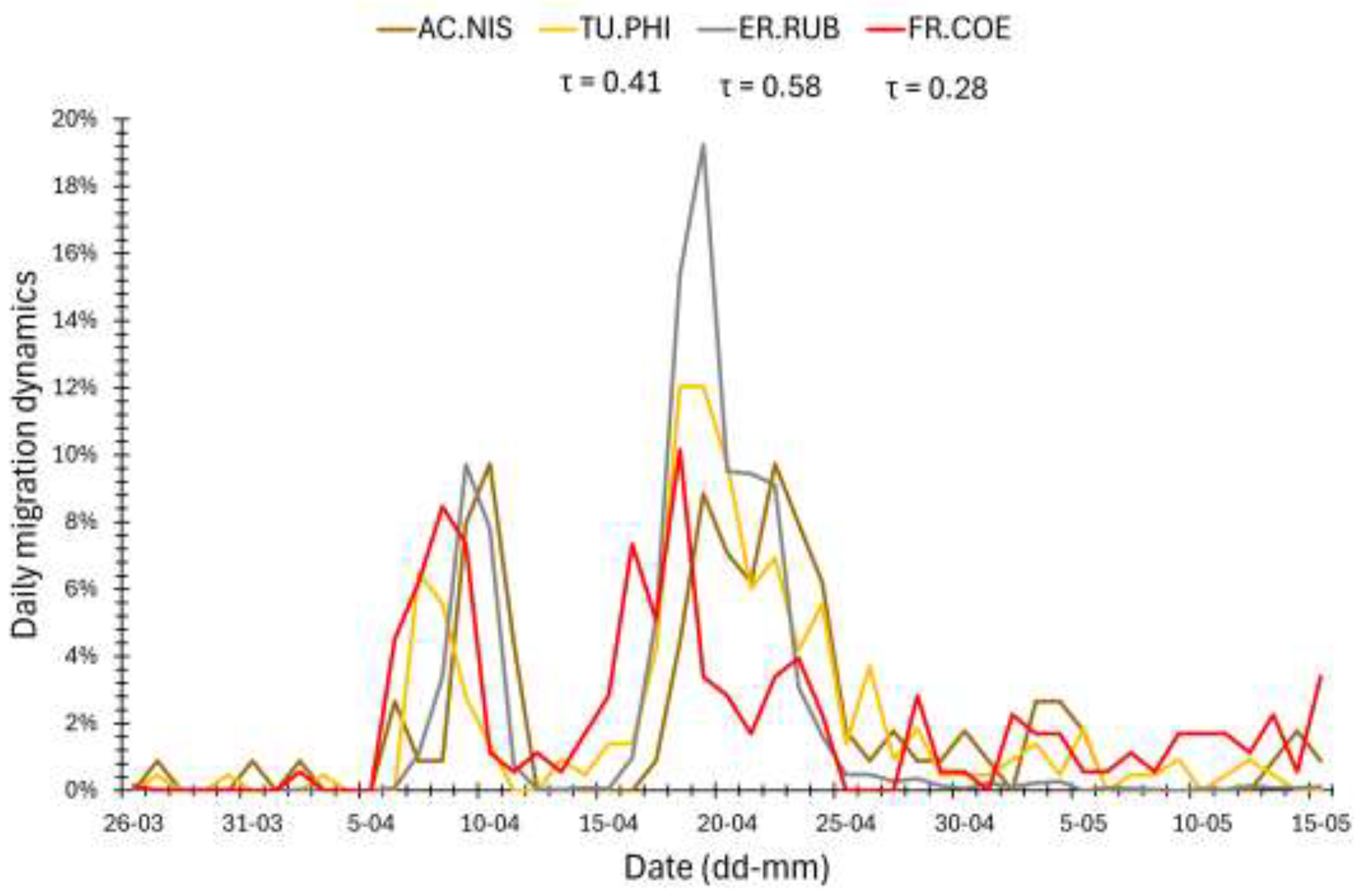

To better understand the relationship between predator and prey migration in each season, we compared the daily migration dynamic of selected prey species and of Sparrowhawks (all groups combined) during seven springs in which more than 100 Sparrowhawks were ringed (

Table A2), using Kendall's Tau correlation coefficient. In this way, for each prey species, we obtained seven correlation coefficients with Sparrowhawk dynamics, one for each selected spring. Thus, we applied the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons and used the adjusted level of significance p < 0.00714 to interpret these results. All statistical calculations were conducted in Statistica 13.3 [

68], and maps were made in QGIS 3.28.5 [

71].

2. Results

2.1. Prey Species in Pluckings and Observations of Attacks in Spring 2024

In spring 2024, 48 pluckings by Sparrowhawks were collected, and 16 Sparrowhawk attacks on other birds were observed, mainly near the mist-nets. Great Tit dominated among the collected pluckings, followed by Blackbird and Song Thrush (

Figure 3A,

Table A3). Among the victims of observed Sparrowhawk attacks, Song Thrush and Robin dominated (

Figure 3B,

Table A4). Based on these results (

Figure 3) and literature (

Table 1), we selected five passerine species (Great Tit, Blackbird, Song Thrush, Robin, Chaffinch) for further analyses, as the main Sparrowhawk’s bird prey species on spring passage.

2.2. Spring Migration Timing of Sparrowhawks by Age and Sex

The first Sparrowhawks in spring at Hel station were caught on 26 March, and their passage lasted until mid-May (

Figure 4,

Figure 5). The timing of spring migration differed between age and sex groups of Sparrowhawks (

Figure 4,

Figure 5). Adult males were the first caught Sparrowhawks, shortly followed by adult females, ahead of the first immatures (

Figure 4,

Figure 5). The median dates of passage of adult males and females were similar (

Figure 5). Most adult males migrated earlier than immature males (

Figure 4), on average by 22 days (

Figure 5). Adult females migrated on average 13 days earlier than immature females (

Figure 5). Immature males migrated the latest and were caught in the largest numbers among all the sex/age groups of Sparrowhawks (

Figure 4,

Figure 5).

The overall migration timing of the Sparrowhawk showed no trend for first (q25) and second (q50) quartiles, but the third (q75) quartile had a significant trend for earlier passage over 1982–2021 (β = –0.11, R² = 0.11, p < 0.05). In none of the four sex/age groups of Sparrowhawks, the median dates (q50) of passage showed any significant trends over 1982–2021 (

Figure 6,

Table A5), but had large year-to-year variation, and were similar for adult males and females (

Figure 6). For none of the prey species, the median dates (q50) of spring passage showed any significant trend over 1982–2021 (

Table A6).

2.3. Relationships Between Spring Migration Timing of the Predator and Prey Species

2.3.1. Relationships in Migration Timing over 1982–2021

The first and last Sparrowhawks were captured at the beginning and at the end of the spring bird ringing season at Hel station, similar to their prey species (

Figure 5). The interquartile range q25–q75 when 50% of Sparrowhawks (all birds jointly) passed through Hel in 1982–2021, overlapped with analogous ranges for the Song Thrush, Robin and Chaffinch (

Figure 5). For adult males and females, the passage of 50% individuals (q25–q75) also overlapped with that of the Great Tits and Blackbirds, which are early migrants at Hel (

Figure 5). The dates for the first (q25) and the third (q75) quartiles of all Sparrowhawks’ passage in subsequent years of the period 1982–2021 were related to the corresponding dates for Robins, and the median date (q50) was related to that of the Song Thrush, according to the best multiple regression models (

Table 4,

Table A7,

Table A8 and

Table A9). For adult male Sparrowhawks, the median date (q50) during 1982–2021 was positively related to the median dates for Robin, according to the best model (

Table 5), which indicated that the predator migrated early if this prey species migrated early and late when Robins migrated late. The median date for this group was also related negatively, though not significantly, to those for the Song Thrush (

Table 5). For adult females, the median date (q50) of passage was positively related to that of the Blackbird. The median date for immature females was positively, though not significantly, related to that of the Song Thrush, and for immature males, the median was negatively associated with that for the Great Tit (

Table 5,

Table A10,

Table A11,

Table A12 and

Table A13).

2.3.2. Correlations of the Daily Migration Dynamics During Selected Springs

The daily migration dynamics of the Sparrowhawk were positively correlated with those for the Song Thrush and Robin in 1989, 1996, 1999, and 2000, and for the Song Thrush only in 2002 (

Table 6,

Figure 7). The correlation with Robin migration was the strongest in 1996 (

Table 6), likely due to two peak periods (6–12 April and 15–23 April) of passage of both species (

Figure 7). In 1996, the Sparrowhawk migration dynamics was also positively correlated with that of the Chaffinch (

Table 6). In 1998, it was significantly and negatively, but weakly, correlated with the dynamics of the Blackbird, Chaffinch and Great Tit. In 2000, the Sparrowhawk daily migration dynamics was negatively correlated with that of the Blackbird, and in 2002 with the Great Tit only (

Table 6).

2.4. Relationship Between Winter and SPRING temperatures and Spring Migration Timing of Sparrowhawk at Hel

For the immature male Sparrowhawk, the median dates (q50) of passage at Hel were early with high temperatures in April around the station (area K2 in

Figure 1), according to the best model (

Table 7). For adult males, the medians of passage at Hel were early with high March temperatures on their wintering grounds and migration routes (area K1), and vice versa. For adult females, the medians were early with warm February on wintering grounds and migration routes (area K1) (

Table 7). For immature females, we found no analogous relationship.

3. Discussion

3.1. Sparrowhawk’s Diet During Spring Migration Through Hel Peninsula

Pluckings were collected in spring 2024 to help the choice of bird prey species for further analyses, which was initially based on literature (

Table 1). The prey species identified in pluckings collected at the spring stopover site around the Hel station corresponded with bird species hunted by Sparrowhawks across Europe during the breeding season [

35,

45,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60], which supported our selection of its five main bird prey species.

The number and diversity of collected pluckings may have been influenced by weather and the difficulty in finding feathers from smaller bird species. Due to the small size of feathers, such as those of the Great Tit and Blue Tit, and their faint colours, it is possible that not all pluckings of small birds were found in the study area. Blackbird and Song Thrush feathers are larger and darker (black, brown) than those of the two species of tits, so they stand out more against the dense green undergrowth in the forest where the material was collected. The dominant species among plucking collected during 26 March–12 May in 2024 were Great Tits and Blackbirds, for which the main peaks of passage that spring occurred at the turn of March and April, when adult Sparrowhawks migrated through Hel (Operation Baltic unpubl. data). This suggests that Sparrowhawks passing through Hel later that spring probably hunted on the late individuals of these prey species, which are usually immature, old or sick birds [

1,

31]. The presence of pluckings of other species, such as the Blue Tit, Redwing, and Skylark, besides the five main prey species, indicates that Sparrowhawk, as a generalist predator, hunts a wide variety of prey during spring migration through Hel (

Figure 3). We did not include these other species in analysis because they were absent or occurred in small numbers in the Sparrowhawk's breeding diet, and were a few among birds ringed at Hel, except of the Blue Tit [

35,

45,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. Many factors might have influenced the pluckings collection, which was limited to one season, thus these results should be treated cautiously and only qualitatively, as an indication of the preferred prey species of the Sparrowhawk during spring migration at Hel.

3.2. Migration Timing of the Sparrowhawk over 1982–2021

3.2.1. Sex- and Age-Differential Timing of Spring Passage

Among all the analysed sex/age groups, adult males arrived at the Hel as the first Sparrowhawks, slightly before the first adult females (

Figure 4). In this species, the male chooses the breeding site, even if both sexes participate in building the nest [

72], which would explain this sequence of passage. The earlier male arrival on breeding grounds (protandry) has been observed in many birds, especially in monogamous species, as the Sparrowhawk [

73]. In such species, males are under greater selection pressure to arrive early on breeding grounds than females, to secure the best breeding territories [

74], which might explain the occurrence of males as first Sparrowhawks at Hel. However, the median dates of spring passage, as well as the numbers of ringed adults of both sexes during 1982–2021, were similar (

Figure 4,

Figure 5), in line with females’ participation in nest building [

72].

Adults migrated through Hel on average ahead of immatures, similarly to Helgoland (Germany), where adults migrated in the first half of April, and youngs migrated only in the second half of April [

49]. This sequence of passage might be the effect of greater experience of adult Sparrowhawks, which enables them to arrive at breeding grounds earlier than immatures to establish breeding and hunting ranges abundant in prey and nesting material, or arrive at their established sites to defend them against immatures and to build a nest on a new tree each year [

72]. Sparrowhawks in spring at the end of their first year of life are sexually mature and can attempt breeding, mostly with a mate of the same age; however, much fewer young pairs have any breeding success than their older counterparts [

49]. Spring passage of adults ahead of youngs was also observed in the Lesser Spotted Eagle

Clanga pomarina and Tawny Eagle

Aquila rapax, in which immatures arrive at the breeding grounds six to ten weeks after adults [

75], and in various eagle species observed during spring passage in Israel [

76]. Having less experience, immatures migrate later in spring and, as a result, choose poorer territories than adults, but still try to reproduce. The difference in migration timing between adults and immatures also probably reduces their competition for food at stopovers, especially in early spring.

Among immatures, the median date of migration was on average 9 days earlier for females than for males (

Figure 5), in contrast to adults. We found no literature record of such a pattern in immature Sparrowhawks. One explanation for that discrepancy in timing might be different food preferences of the sexes. The main prey of female Sparrowhawks are birds from families Turdidae and Sturnidae, whereas male Sparrowhawks hunt smaller birds, from families Fringillidae and Paridae [

49]. Our results showed that the median dates of spring passage of young female Sparrowhawks were related (

Table 5), with those of the Song Thrush, and their main periods of passage (q25–q75) overlapped (

Figure 4). The timing of spring passage of young males overlapped with the second half of the passage of all prey species (

Figure 4), and males tend to hunt smaller prey, which is abundant throughout spring [

49]. Risch and Brinkhof [

77] showed that among 102 breeding pairs with known age for both sexes, studied in 1992–1996 in Northern Germany, 80 pairs were of the same age category (64 adult and 16 first-year pairs), but among the remaining 22 pairs, 20 were “adult male and first-year female” pairs [

77]. Furthermore, females of any age class paired with adult males started egg laying earlier than females that mated first-year males. During the reproductive period, the male provides food for the female and their offspring [

45,

49,

77]. Immature males, which have less experience and probably poorer hunting grounds, provide less or lower-quality food than adults, extending the time required to raise chicks. Thus, immature females likely migrate earlier in spring than immature males to pair with an experienced male and increase breeding success.

We found a trend for earlier migration over 1982–2021 only for the third quartile (q75) of Sparrowhawk passage, which likely represents the shift in migration timing for immature males that dominate the last phase of the Sparrowhawk passage at Hel (

Figure 4). In our study, no long-term trends in the median dates of passage for any sex and age group of Sparrowhawks were significant; however, all groups showed a tendency for earlier median dates of spring passage through Hel over 1982–2021, corresponding with the results from Hanko Bird Observatory in Finland [

31]. Lehikoinen and co-authors [

31] showed that the beginning of migration (the date of 5% of passage), which includes mostly adult Sparrowhawks, through Finland has advanced by 11 days over 1979–2007, but the dates of 50% and 95% migrating individuals did not show any analogous shift [

31]. Thus, both in our study and in that from Hanko [

31], some multi-year shifts for earlier spring passage occurred in Sparrowhawks, although for different phases of passage. The source of this discrepancy might be differences in the periods of these two studies, as the selection of years affects the resulting multi-year trend in migration phenology [

28]. Additionally, the studies differed in the method used, as data from Hanko came from daily count data of migrating Sparrowhawks [

31], and we used data from ringing.

3.2.3. Effect of Temperatures at Wintering Grounds and Migration Routes on Sparrowhawks' Spring Migration at Hel

The Sparrowhawk is a short- or medium-distance migrant [

46], and such migrants respond to climate change quicker than long-distance migrants, which overwinter far away from their breeding grounds [

78,

79]. The influence of temperature on migration timing can vary between age and sex groups within one species [

80]. In our study, the migration timing of each sex/age group of Sparrowhawks was related to temperature in different months and areas, but in the same way: early median dates (q50) of spring passage at Hel were related to high temperatures at the non-breeding grounds, and vice versa (

Table 7). For adult females, the medians of passage at Hel were related to temperatures on wintering grounds and migration routes (K1 square at Fig. 1) in February, and for the males in March, when Sparrowhawks begin their migration [

81], as most adult Sparrowhawks were caught at Hel in the first half of April (

Figure 5). These results suggest that warm end of winter at non-breeding areas promotes early migration of adults, probably because of their lower energy expense on thermoregulation and increased efficiency of hunting as their prey species also begin spring migration early after warm winters [

5,

6,

7,

28,

29,

30]. Warm winters at those grounds might benefit females’ hunting and thus their faster accumulation of reserves required for migration, which would promote their earlier departure from the wintering quarters and faster spring passage with fewer stopovers. As Sparrowhawk is a short- to medium-distance migrant, weather conditions at the wintering grounds before departure correspond with conditions on route and at breeding grounds [

74,

82]. Hence, a warm March at wintering grounds might be an indication for adult male Sparrowhawks of an early and warm spring on the migration route, and likely also at the breeding grounds, which urges them to depart early and migrate as fast as possible, to occupy the best breeding territory.

In contrast, the median for immature males at Hel was early when April was warm near the station (K2 square), and they were the only sex/age group that responded to local temperatures, likely because they migrate through Hel the latest, between mid-April and mid-May (

Figure 4,

Figure 5). This corresponds with the results from Hanko, where local April temperatures explained some part of the variation in the migration timing of Sparrowhawks, for all sex/age groups analysed jointly [

31].

3.3. Migration Timing of the Predator and of the Prey Species

The dates of q25 and q75 of Sparrowhawks passage (all individuals jointly) and the median (q50) date for adult males during 1982–2021were positively related to analogous dates for the Robin (

Table 4,

Table 5), and in three out of seven springs the daily migration dynamics of these species were correlated (

Table 6), which point at Robin as an important prey for Sparrowhawk. Robins migrating through Hel ringing station advanced all phases of their spring passage (5%, 50%, 95%) over 1970–2018 [

29], similarly as at Helgoland station (North Sea, Germany, 1960–2000) [

14] and on Christiansø island (Baltic Sea, Denmark, 1979–1997) [

83]. However, we found no significant trend in the median dates of passage of Robin at Hel over 1982–2021, similarly to the Sparrowhawk, but both species showed strong year-to-year variation in spring phenology. Like the Sparrowhawk, Robin is a medium-distance migrant [

29], and populations of these species that migrate through the southern Baltic coast share breeding grounds in Fennoscandia, the Baltic countries, and western Russia, and wintering grounds in the Iberian Peninsula and the Apennine Peninsula (

Figure 2) [

41]. The relationships between migration timing of Sparrowhawks and Robins in subsequent springs suggest that this predator adjusts its spring phenology to the year-to-year changes in phenology of that prey species.

The median (q50) dates of spring migration at Hel for Sparrowhawks (all birds) during 1982–2021 were related to analogous dates for Song Thrush, and in four out of seven chosen seasons, the daily migration dynamics were positively correlated between these species (

Table 4,

Table 6). April is the main month of Song Thrush migration through the Baltic region [

28,

84], including Hel (

Figure 5), similarly to most Sparrowhawks, which then can use the abundance of Song Thrush as their prey. Warm February at the wintering grounds and warm April along migration routes were related to early spring passage of the Song Thrush at Hel [

28,

74], as in the Sparrowhawk. This similarity suggests that the Sparrowhawk might adjust its migration timing each spring to that of the Song Thrush, which is an attractive prey.

The passage of 50% of adult female Sparrowhawks (range q25–q75) overlapped with the main period of Blackbird passage through Hel, and the median dates of passage for adult females during 1982–2021 were related to those of Blackbirds (

Table 5), which suggests females’ preference for this prey species. Female Sparrowhawks, being up to 25% larger than males, hunt for larger prey, including birds from the Turdidae family [

49], which corresponds well with our results.

The median dates of immature male Sparrowhawk migration at Hel correlated negatively with those for the Great Tit (

Table 5), and daily migration dynamics of both species were negatively correlated in 1998 and 2002 (

Table 6). Most Great Tits migrate through the Baltic region early in spring [

85], as confirmed by our results, which showed that 50% of this species’ passage at Hel was cumulated within 9 days at the turn of March and April (

Figure 5). Such timing of Great Tit passage differed the most from that of immature male Sparrowhawks, for which the first quarter of individuals (q25) passes through Hel on average at the end of April, when most Great Tits are already gone (

Figure 5). Thus, these negative correlations likely result from a very different time of migration of these species, rather than from young Sparrowhawks “avoiding” Great Tits. Among the collected pluckings, Great Tits dominated (

Figure 3), which might have been caused by Sparrowhawks preying upon individuals that migrate late, which are likely young or sick individuals [

1,

31] that are easy prey for the raptor.

The daily migration dynamics of Chaffinch, as the only of the five prey we studied, correlated positively (in 1996) and negatively (in 1998) with the dynamics of the Sparrowhawk's migration. The Chaffinch migration at Hel, like that of the Sparrowhawk, shows large year-to-year variation in timing and numbers related to temperatures at its non-breeding grounds [

30], which may explain the different signs of the correlation in those years. In spring 1998, most Chaffinches migrated early, ahead of most Sparrowhawks, hence the negative correlation of their migration dynamics, similar to the Great Tits. But in 1996, Chaffinches were more numerous at Hel than in 1998 (

Table A2), and their main migration occurred in April, with peaks on similar days to those of Sparrowhawks, which explains the positive correlation, and suggests that Sparrowhawks used the abundance of Chaffinches as their prey at that time.

4. Conclusions

We demonstrated that the year-to-year changes in spring migration timing of Sparrowhawks were correlated with those of their prey species, with some differences between age and sex groups of the predator, reflecting their food preferences linked to their sexual dimorphism in size. Our results suggest that Sparrowhawks adjust their migration timing each spring to match the current availability of their prey species, which in turn is influenced by temperature and conditions at their non-breeding grounds. Sparrowhawks are among the peak bird predators, which regulate the population size of their prey species in forests. Thus, identifying changes in predator-prey dynamics of that species in the face of climate change is key to understanding the effect of such changes on forest ecosystems. Long-term monitoring at bird ringing stations located at bird stopover sites provides valuable data that can contribute to our understanding of changes in such relationships in complex food chains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.C. and M.R.; methodology, K.C and M.R.; validation, M.R., formal analysis, K.C. and M.R.; investigation, K.C.; resources, M.R.; data curation, K.C.; writing—original draft preparation, K.C.; writing—review and editing, M.R.; visualization, K.C.; supervision, M.R.; project administration, M.R.; funding acquisition, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been supported over the years by the Special Research Facility grants (SPUB) from the Polish Ministry of Education and Science to the Bird Migration Research Station, University of Gdańsk.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No approval of any Institutional Board was required for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data contained within the article or supplementary material or is derived from public domain resources. Data from ringing at Operation Baltic ringing stations can be found at the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) database at: Ringing Data from the Bird Migration Research Station, University of Gdańsk (Occurrence dataset

https://doi.org/10.15468/q5o88l) [

86] accessed via GBIF.org on 8 July 2025.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the volunteers and the staff of the Bird Migration Research Station, University of Gdańsk, Poland, for collecting the data at Operation Baltic stations used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients of the temperatures in February–April in 1982–2021 in squares K1 and K2 (

Figure 1), which we used as explanatory variables in multiple regression models. Significant correlations after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (p < 0.00714) are marked in

bold font.

Table A1.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients of the temperatures in February–April in 1982–2021 in squares K1 and K2 (

Figure 1), which we used as explanatory variables in multiple regression models. Significant correlations after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (p < 0.00714) are marked in

bold font.

| |

K1_MAR |

K2_MAR |

K2_APR |

| K1_FEB |

0.43 |

0.56 |

0.34 |

| K1_MAR |

|

0.80 |

0.34 |

| K2_MAR |

|

|

0.37 |

Table A2.

Number of Sparrowhawks and selected prey species caught in consecutive spring seasons (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel bird ringing station (N Poland). Years marked in bold – years in which more than 100 Sparrowhawks were caught, selected to determine the correlations between their daily migration dynamics and that of the Sparrowhawk (treated jointly).

Table A2.

Number of Sparrowhawks and selected prey species caught in consecutive spring seasons (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel bird ringing station (N Poland). Years marked in bold – years in which more than 100 Sparrowhawks were caught, selected to determine the correlations between their daily migration dynamics and that of the Sparrowhawk (treated jointly).

Year/

species |

Sparrowhawk |

Song Thrush |

Blackbird |

Chaffinch |

Robin |

Great Tit |

| 1982 |

10 |

292 |

120 |

209 |

1219 |

775 |

| 1983 |

39 |

227 |

99 |

223 |

484 |

200 |

| 1984 |

21 |

178 |

152 |

141 |

653 |

267 |

| 1985 |

14 |

105 |

38 |

63 |

525 |

148 |

| 1986 |

44 |

187 |

27 |

94 |

511 |

171 |

| 1987 |

35 |

69 |

37 |

94 |

450 |

192 |

| 1988 |

16 |

75 |

7 |

32 |

205 |

93 |

| 1989 |

139 |

137 |

12 |

56 |

282 |

24 |

| 1990 |

57 |

148 |

4 |

82 |

254 |

8 |

| 1991 |

91 |

102 |

12 |

51 |

194 |

44 |

| 1992 |

65 |

62 |

5 |

54 |

103 |

21 |

| 1993 |

93 |

111 |

10 |

76 |

405 |

33 |

| 1994 |

49 |

92 |

9 |

66 |

257 |

61 |

| 1995 |

21 |

121 |

44 |

158 |

1225 |

539 |

| 1996 |

113 |

216 |

341 |

177 |

3623 |

391 |

| 1997 |

94 |

150 |

76 |

215 |

1362 |

484 |

| 1998 |

162 |

196 |

202 |

84 |

1513 |

162 |

| 1999 |

116 |

170 |

82 |

132 |

1590 |

49 |

| 2000 |

105 |

199 |

138 |

164 |

1114 |

217 |

| 2001 |

94 |

157 |

65 |

162 |

590 |

115 |

| 2002 |

112 |

231 |

116 |

217 |

1737 |

169 |

| 2003 |

106 |

309 |

128 |

232 |

2326 |

81 |

| 2004 |

66 |

239 |

88 |

115 |

2377 |

535 |

| 2005 |

18 |

208 |

122 |

167 |

1543 |

1207 |

| 2006 |

62 |

217 |

290 |

133 |

1109 |

731 |

| 2007 |

39 |

366 |

86 |

184 |

1990 |

144 |

| 2008 |

64 |

234 |

105 |

112 |

1789 |

1464 |

| 2009 |

55 |

336 |

138 |

153 |

2786 |

522 |

| 2010 |

50 |

141 |

61 |

126 |

1100 |

56 |

| 2011 |

54 |

261 |

121 |

141 |

1766 |

689 |

| 2012 |

58 |

244 |

32 |

253 |

1890 |

36 |

| 2013 |

25 |

150 |

288 |

145 |

910 |

1767 |

| 2014 |

33 |

233 |

23 |

102 |

1335 |

70 |

| 2015 |

46 |

219 |

104 |

145 |

1074 |

259 |

| 2016 |

31 |

337 |

167 |

180 |

2360 |

1097 |

| 2017 |

41 |

230 |

86 |

118 |

1980 |

53 |

| 2018 |

33 |

305 |

193 |

181 |

1367 |

177 |

| 2019 |

23 |

609 |

118 |

248 |

4673 |

108 |

| 2020 |

15 |

345 |

112 |

208 |

2414 |

73 |

| 2021 |

35 |

366 |

131 |

201 |

1831 |

332 |

Table A3.

Bird pluckings collected near Hel bird ringing station during 26 March – 12 May 2024. The results are summarised in

Figure 3A.

Table A3.

Bird pluckings collected near Hel bird ringing station during 26 March – 12 May 2024. The results are summarised in

Figure 3A.

| No |

Date |

Species |

Scientific name |

| 1 |

28.03.2024 |

Great Spotted Woodpecker |

Dendrocopos major |

| 2 |

29.03.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

| 3 |

29.03.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

| 4 |

30.03.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 5 |

30.03.2024 |

Redwing |

Turdus iliacus |

| 6 |

30.03.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

| 7 |

31.03.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

| 8 |

31.03.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

| 9 |

31.03.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 10 |

31.03.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 11 |

01.04.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

| 12 |

01.04.2024 |

Robin |

Erithacus rubecula |

| 13 |

01.04.2024 |

Robin |

Erithacus rubecula |

| 14 |

01.04.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 15 |

01.04.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

| 16 |

01.04.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 17 |

01.04.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

| 18 |

01.04.2024 |

Redwing |

Turdus iliacus |

| 19 |

01.04.2024 |

Robin |

Erithacus rubecula |

| 20 |

01.04.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 21 |

01.04.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 22 |

02.04.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

| 23 |

06.04.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

| 24 |

20.04.2024 |

Blue Tit |

Cyanistes caeruleus |

| 25 |

20.04.2024 |

Blue Tit |

Cyanistes caeruleus |

| 26 |

20.04.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 27 |

20.04.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

| 28 |

20.04.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 29 |

20.04.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 30 |

20.04.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

| 31 |

20.04.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

| 32 |

25.04.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

| 33 |

26.04.2024 |

Chaffinch |

Fringilla coelebs |

| 34 |

01.05.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

| 35 |

01.05.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

| 36 |

01.05.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

| 37 |

02.05.2024 |

Lesser Spotted Woodpecker |

Dryobates minor |

| 38 |

02.05.2024 |

Skylark |

Alauda arvensis |

| 39 |

03.05.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 40 |

03.05.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 41 |

03.04.2024 |

Blue Tit |

Cyanistes caeruleus |

| 42 |

07.05.2024 |

Skylark |

Alauda arvensis |

| 43 |

07.05.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 44 |

07.05.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

| 45 |

07.05.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

| 46 |

07.05.2024 |

Great Spotted Woodpecker |

Dendrocopos major |

| 47 |

07.05.2024 |

Hawfinch |

Coccothraustes coccothraustes |

| 48 |

12.05.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

Table A4.

Sparrowhawks' prey during attacks observed near the Hel bird ringing station during 26 March–12 May 2024. F = female, M = male, I = immature, A = adult, „– “ = a lack of information about Sparrowhawk’s sex or age. The results are summarised in

Figure 3B.

Table A4.

Sparrowhawks' prey during attacks observed near the Hel bird ringing station during 26 March–12 May 2024. F = female, M = male, I = immature, A = adult, „– “ = a lack of information about Sparrowhawk’s sex or age. The results are summarised in

Figure 3B.

| No |

Date |

Species |

Scientific name |

Sex and age of Sparrowhawk |

Type of observation |

| 1 |

26.03.2024 |

Regulus sp. |

Regulus sp. |

M |

Observation of chase after prey |

| 2 |

27.03.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

F, I |

Mist-net |

| 3 |

27.03.2024 |

Robin |

Erithacus rubecula |

- |

Mist-net |

| 4 |

27.03.2024 |

Great Tit |

Parus major |

M |

Mist-net |

| 5 |

30.03.2024 |

Wren |

Troglodytes troglodytes |

M, A |

Mist-net |

| 6 |

05.04.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

- |

Mist-net |

| 7 |

07.04.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

- |

Mist-net |

| 8 |

08.04.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

F, A |

Mist-net |

| 9 |

11.04.2024 |

Robin |

Erithacus rubecula |

- |

Sparrowhawk attack |

| 10 |

14.04.2024 |

Robin |

Erithacus rubecula |

- |

Mist-net |

| 11 |

20.04.2024 |

Chaffinch |

Fringilla coelebs |

- |

Mist-net |

| 12 |

21.04.2024 |

Robin |

Erithacus rubecula |

- |

Mist-net |

| 13 |

21.04.2024 |

Redwing |

Turdus iliacus |

I |

Mist-net |

| 14 |

26.04.2024 |

Blackcap |

Sylvia atricapilla |

A |

Mist-net |

| 15 |

28.04.2024 |

Song Thrush |

Turdus philomelos |

- |

Mist-net |

| 16 |

28.04.2024 |

Blackbird |

Turdus merula |

- |

Mist-net |

Table A5.

Summary statistics for linear regressions of the median (q50) dates of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk spring migration in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). The linear regressions are presented in

Figure 6.

β Slope = regression coefficient, SE = Standard Error; R²- determination coefficient, t, p = results of t-test, p < 0.05 marked in bold face, 40 x

β = estimated change in days of migration timing over 1982-2021, negative values reflect shift to earlier migration.

Table A5.

Summary statistics for linear regressions of the median (q50) dates of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk spring migration in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). The linear regressions are presented in

Figure 6.

β Slope = regression coefficient, SE = Standard Error; R²- determination coefficient, t, p = results of t-test, p < 0.05 marked in bold face, 40 x

β = estimated change in days of migration timing over 1982-2021, negative values reflect shift to earlier migration.

| Sex/age group |

β Slope |

SE |

R² |

t |

P |

40 years x β (Days) |

| ACNIS_MI |

-0,11 |

0,06 |

0,09 |

-1,94 |

0,06 |

-4,4 |

| ACNIS_MA |

-0,07 |

0,07 |

0,03 |

-1,01 |

0,32 |

-2,8 |

| ACNIS_FI |

-0,05 |

0,06 |

0,02 |

-0,82 |

0,42 |

-2,0 |

| ACNIS_FA |

-0,13 |

0,12 |

0,05 |

-1,06 |

0,30 |

-5,2 |

Table A6.

Summary statistics for linear regressions of the median (q50) dates of the prey species spring migration in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). β Slope = regression coefficient, SE = Standard Error; R² = determination coefficient, t, p = results of t-test, p < 0.05 marked in bold face, 40 x β = estimated change in days of migration timing over 1982–2021, negative values reflect shift to earlier migration.

Table A6.

Summary statistics for linear regressions of the median (q50) dates of the prey species spring migration in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). β Slope = regression coefficient, SE = Standard Error; R² = determination coefficient, t, p = results of t-test, p < 0.05 marked in bold face, 40 x β = estimated change in days of migration timing over 1982–2021, negative values reflect shift to earlier migration.

| Species |

β Slope |

SE |

R² |

t |

P |

40 years x β (Days) |

| Song Thrush |

–0,02 |

0,06 |

0,00 |

–0,32 |

0,75 |

–0,8 |

| Blackbird |

–0,05 |

0,06 |

0,01 |

–0,75 |

0,46 |

–2,0 |

| Chaffinch |

–0,05 |

0,08 |

0,01 |

–0,59 |

0,56 |

–2,0 |

| Great Tit |

0,07 |

0,06 |

0,04 |

1,22 |

0,23 |

2,8 |

| Robin |

–0,10 |

0,08 |

0,05 |

–1,34 |

0,19 |

–4,0 |

Table A7.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the first quartile (q25) of spring migration of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). ACNIS = Eurasian Sparrowhawk

Accipiter nisus, FRCOE = Chaffinch

Fringilla coelebs, PAMAJ = Great Tit

Parus major, TUMER = Blackbird

Turdus merula, TUPHI = Song Thrush

Turdus philomelos. The table presents all models with ΔAIC < 2. The models ranked by Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC), k is the number of estimated parameters in the model, ∆AIC gives the difference in AICc from the model with the lowest AIC. The best model, presented in

Table 4 and discussed in the text, is marked in

bold face.

Table A7.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the first quartile (q25) of spring migration of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). ACNIS = Eurasian Sparrowhawk

Accipiter nisus, FRCOE = Chaffinch

Fringilla coelebs, PAMAJ = Great Tit

Parus major, TUMER = Blackbird

Turdus merula, TUPHI = Song Thrush

Turdus philomelos. The table presents all models with ΔAIC < 2. The models ranked by Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC), k is the number of estimated parameters in the model, ∆AIC gives the difference in AICc from the model with the lowest AIC. The best model, presented in

Table 4 and discussed in the text, is marked in

bold face.

| Model Formula |

k |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB |

1 |

243.40 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB + TUMER |

2 |

244.44 |

1.04 |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB + PAMAJ |

2 |

245.38 |

1.98 |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB + FRCOE |

2 |

245.39 |

1.99 |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB + TUPHI |

2 |

245.40 |

2.00 |

Table A8.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

Table A8.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

| Model Formula |

k |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS ~ TUPHI |

1 |

242.86 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS ~ TUPHI + PAMAJ |

2 |

242.88 |

0.03 |

| ACNIS ~ FRCOE + TUPHI + PAMAJ |

3 |

244.08 |

1.22 |

| ACNIS ~ TUMER + TUPHI + PAMAJ |

3 |

244.18 |

1.32 |

| ACNIS ~ FRCOE + TUPHI |

2 |

244.41 |

1.55 |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB + TUPHI |

2 |

244.85 |

1.97 |

Table A9.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the third quartile (q75) of spring migration of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

Table A9.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the third quartile (q75) of spring migration of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

| Model Formula |

k |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB |

1 |

225.00 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB + PAMAJ |

2 |

226.74 |

1.74 |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB + FRCOE |

2 |

226.78 |

1.78 |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB + TUMER |

2 |

226.98 |

1.98 |

| ACNIS ~ ERRUB + TUPHI |

2 |

227.00 |

2.00 |

Table A10.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of the immature males of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

Table A10.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of the immature males of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

| Model Formula |

k |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS_MI ~ PAMAJ |

1 |

229.04 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS_MI ~ TUMER + PAMAJ |

2 |

230.74 |

1.70 |

| ACNIS_MI ~ FRCOE + PAMAJ |

2 |

230.80 |

1.76 |

| ACNIS_MI ~ ERRUB + PAMAJ |

2 |

230.90 |

1.86 |

| ACNIS_MI ~ TUPHI + PAMAJ |

2 |

230.91 |

1.87 |

Table A11.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of the adult males of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

Table A11.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of the adult males of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

| Model Formula |

K |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS_MA~ ERRUB + TUPHI |

2 |

213.92 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS_MA ~ ERRUB + TUPHI + PAMAJ |

3 |

215.04 |

1.12 |

| ACNIS_MA ~ ERRUB |

1 |

215.06 |

1.14 |

| ACNIS_MA ~ PAMAJ |

1 |

215.56 |

1.64 |

| ACNIS_MA ~ ERRUB + FRICOE + TUPHI |

3 |

215.63 |

1.71 |

| ACNIS_MA ~ ERRUB + TUMER + TUPHI |

3 |

215.87 |

1.95 |

Table A12.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of the immature females of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

Table A12.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of the immature females of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

| Model Formula |

K |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS_FI ~ TUPHI |

1 |

219.36 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS_FI ~ ERRUB |

1 |

220.28 |

0.92 |

| ACNIS_FI ~ TUMER + TUPHI |

2 |

221.29 |

1.93 |

| ACNIS_FI ~ ERRUB + TUPHI |

2 |

221.31 |

1.95 |

| ACNIS_FI ~ FRICOE + TUPHI |

2 |

221.33 |

1.97 |

| ACNIS_FI ~ TUPHI + PAMAJ |

2 |

221.34 |

1.98 |

Table A13.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of the adult females of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

Table A13.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of the adult females of the Eurasian Sparrowhawk and its prey species, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). Symbols as in

Table A7.

| Model Formula |

K |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS_FA ~ TUMER |

1 |

158.69 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ TUMER + TUPHI |

2 |

158.85 |

0.16 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ TUMER + PAMAJ |

2 |

159.31 |

0.62 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ FRCOE + TUMER |

2 |

159.61 |

0.92 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ FRCOE + TUMER + PAMAJ |

3 |

159.83 |

1.14 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ TUMER + TUPHI + PAMAJ |

3 |

159.90 |

1.21 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ ERRUB + TUMER + TUPHI |

3 |

159.95 |

1.26 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ PAMAJ |

1 |

160.20 |

1.51 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ FRCOE + TUMER + TUPHI |

3 |

160.26 |

1.57 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ ERRUB + TUMER |

2 |

160.51 |

1.82 |

Table A14.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of immature males Eurasian Sparrowhawk, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). and temperatures in February–April in regions K1 and K2 (Fig. 1). The table presents all models with ΔAIC < 2. The models ranked by Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC), k is the number of estimated parameters in the model, ∆AIC gives the difference in AICc from the model with the lowest AIC. The best model, presented in

Table 7 and discussed in the text, is marked in bold face.

Table A14.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of immature males Eurasian Sparrowhawk, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland). and temperatures in February–April in regions K1 and K2 (Fig. 1). The table presents all models with ΔAIC < 2. The models ranked by Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC), k is the number of estimated parameters in the model, ∆AIC gives the difference in AICc from the model with the lowest AIC. The best model, presented in

Table 7 and discussed in the text, is marked in bold face.

| Model Formula |

k |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS_MI ~ K2 April |

1 |

230.89 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS_MI ~ K2 April + K1 February |

2 |

231.84 |

0.95 |

| ACNIS_MI ~ K2 April + K1 March |

2 |

232.78 |

1.22 |

Table A15.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of adult males Eurasian Sparrowhawk, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland) and temperatures in February–April in regions K1 and K2 (Fig. 1). Symbols as in

Table A14.

Table A15.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of adult males Eurasian Sparrowhawk, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland) and temperatures in February–April in regions K1 and K2 (Fig. 1). Symbols as in

Table A14.

| Model Formula |

k |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS_MA ~ K1 March |

1 |

212,90 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS_MA ~ K1 February + K1 March |

2 |

213,97 |

1,07 |

| ACNIS_MA ~ K1 February |

1 |

214,14 |

1,24 |

| ACNIS_MA ~ K2 April + K1 March |

2 |

214,88 |

1,98 |

Table A16.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of immature females Eurasian Sparrowhawk, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland) and temperatures in February–April in regions K1 and K2 (Fig. 1). Symbols as in

Table A14.

Table A16.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of immature females Eurasian Sparrowhawk, ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland) and temperatures in February–April in regions K1 and K2 (Fig. 1). Symbols as in

Table A14.

| Model Formula |

k |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS_FI ~ K1 March |

1 |

220,64 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS_FI ~ K1 February + K1 March |

2 |

221,03 |

0,39 |

| ACNIS_FI ~ K2 April + K1 March |

2 |

221,62 |

0,98 |

| ACNIS_FI ~ K1 February |

1 |

221,89 |

1,25 |

| ACNIS_FI ~ K2 April |

1 |

221,96 |

1,32 |

| ACNIS_FI ~ K2 April + K1 March |

3 |

222,48 |

1,83 |

Table A17.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of adult females Eurasian Sparrowhawk ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland) and temperatures in February–April in regions K1 and K2 (Fig. 1). Symbols as in

Table A14.

Table A17.

Model selection procedure by “all subsets”, according to AIC, from the full model of the relationship between the dates of the median (q50) of spring migration of adult females Eurasian Sparrowhawk ringed during spring migration (26 March – 15 May) in 1982–2021 at the Hel ringing station (N Poland) and temperatures in February–April in regions K1 and K2 (Fig. 1). Symbols as in

Table A14.

| Model Formula |

k |

AIC |

ΔAIC |

| ACNIS_FA ~ K1 February |

1 |

161,83 |

0.00 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ K4 April + K1 February |

2 |

163,06 |

1,23 |

| ACNIS_FA ~ K1 February + K1 March |

2 |

163,82 |

2,00 |

References

- Newton, I. The migration ecology of birds; Academic Press: London, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lehikoinen, E; Sparks, TH; Møller, AP; Fiedler, W; Berthold, P. Changes in migration. In (red) Effects of Climate Change on Birds; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2010; pp. s.89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, C. J. The disproportionate effect of global warming on the arrival dates of short-distance migratory birds in North America. Ibis 2003, 145, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenni, L.; Kéry, M. Timing of autumn bird migration under climate change: Advances in long-distance migrants, delays in short-distance migrants. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2003, 270(1523), 1467–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Both, C.; Artemyev, A. V.; Blaauw, B.; Cowie, R. J.; Dekhuijzen, A. J.; Eeva, T.; Enemar, A.; Gustafsson, L.; Ivankina, E. V.; Järvinen, A.; Metcalfe, N. B.; Nyholm, N. E. I.; Potti, J.; Ravussin, P. A.; Sanz, J. J.; Silverin, B.; Slater, F. M.; Sokolov, L. V.; Török, J.; Visser, M. E. Large-scale geographical variation confirms that climate change causes birds to lay earlier. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2004, 271(1549), 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Both, C.; te Marvelde, L. Climate change and timing of avian breeding and migration throughout Europe. Climate Research 2007, 35(1–2), 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordo, O. Why are bird migration dates shifting? A review of weather and climate effects on avian migratory phenology. Climate Research 2007, 35, 7–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A. R.; Flaspohler, D. J.; Froese, R. E.; Ford, D. Climate variability and the timing of spring raptor migration in eastern North America. Journal of Avian Biology 2016, 47(2), 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretagnolle, V.; Terraube, J. Predator–prey interactions and climate change. In Effects of Climate Change on Birds, 2nd ed; Dunn, P.O., Møller, A. P., Eds.; Oxford University Press, 2019; pp. 199–220. [Google Scholar]

- Lehikoinen, A.; Lindén, A.; Karlsson, M.; Andersson, A.; Crewe, T. L.; Dunn, E. H.; Gregory, G.; Karlsson, L.; Kristiansen, V.; Mackenzie, S.; Newman, S.; Røer, J. E.; Sharpe, C.; Sokolov, L. V.; Steinholtz, Å.; Stervander, M.; Tirri, I. S.; Tjørnløv, R. S. Phenology of the avian spring migratory passage in Europe and North America: Asymmetric advancement in time and increase in duration. Ecological Indicators 2019, 101, 985–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, S.; Guralnick, R.; Tingley, M.; Otegui, J.; Withey, J.; Elmendorf, S.; Andrew, M.; Leyk, S.; Pearse, I.; Schneider, D. Increasing phenological asynchrony between spring green-up and arrival of migratory birds. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaifman, J.; Shan, D.; Ay, A.; Jimenez, A. Shifts in Bird Migration Timing in North American Long-Distance and Short-Distance Migrants Are Associated with Climate Change. International Journal of Zoology 2017, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forchhammer, M. C.; Post, E.; Stenseth, N. C. North Atlantic Oscillation timing of long- and short-distance migration. Journal of Animal Ecology 2002, 71(6), 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüppop, O.; Hüppop, K. North Atlantic Oscillation and timing of spring migration in birds. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2003, 270(1512), 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stervander, M.; Lindström, Å.; Jonzén, N.; Andersson, A. Timing of spring migration in birds: long-term trends, North Atlantic Oscillation and the significance of different migration routes. Journal of Avian Biology 2005, 36(3), 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryjanowski, P.; Stenseth, N. C.; Matysioková, B. The Indian Ocean Dipole as an indicator of climatic conditions affecting European birds. Climate Research 2013, 57(1), 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remisiewicz, M.; Underhill, L. G. Large-Scale Climatic Patterns Have Stronger Carry-Over Effects than Local Temperatures on Spring Phenology of Long-Distance Passerine Migrants between Europe and Africa. Animals 2022, 12(13), 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołębiewski, I.; Remisiewicz, M. Carry-Over Effects of Climate Variability at Breeding and Non-Breeding Grounds on Spring Migration in the European Wren Troglodytes troglodytes at the Baltic Coast. Animals 2023, 13(12), 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylianakis, J.; Didham, R.; Bascompte, J.; Wardle, D. Global change and species interactions in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecology Letters 11 2008, 1351–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, A.E.; Aiello-Lammens, M.E.; Fisher-Reid, M.C.; Hua, X.; Karanewsky, C.J.; Yeong Ryu, H.; Sbeglia, G.C.; Spagnolo, F.; Waldron, J.B.; Warsi, O.; Wiens, J.J. How does climate change cause extinction? Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences 2013, 280, 20121890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, A.E.; Schmitz, O.J. Climate change, nutrition, and bottom-up and top-down food web processes. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 2016, 31, 965–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bascompte, J.; Jordano, P.; Olesen, J. Asymmetric coevolutionary networks facilitate biodiversity maintenance. Science 312 2006, 431–3. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, W.; Briggs, C.; Nisbet, R. Consumer-resource dynamics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Both, C.; van Asch, M.; Bijlsma, R.; van den Burg, A.; Visser, M. Climate change and unequal phenological changes across four trophic levels: Constraints or adaptations? Journal of Animal Ecology 2009, 78, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Alerstam, T.; Hedenstrom, A.; Akesson, S. Long-distance migration: evolution and determinants. Oikos 2003, 103, 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Worcester, R.; Ydenberg, R. Cross-continental pattern in the timing of southward Peregrine Falcon migration in North America. J. Raptor Res. 2008, 42, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffré, M.; Beaugrand, G.; Goberville, É.; Jiguet, F.; Kjellén, N.; Troost, G.; Dubois, P. J.; Leprêtre, A.; Luczak, C. Long-term phenological shifts in raptor migration and climate. PLoS ONE 2013, 8((11).). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]