Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

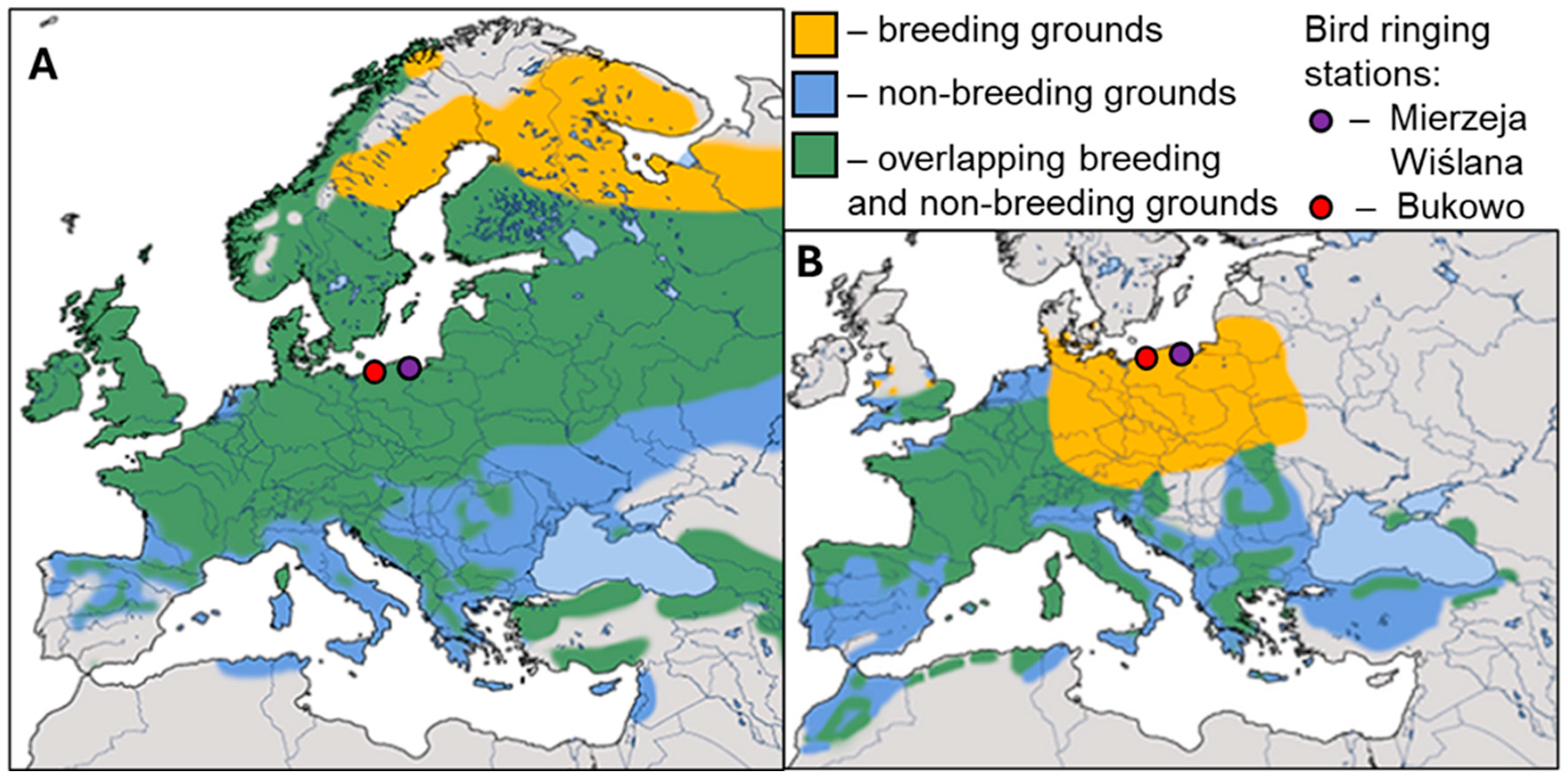

2.1. Study Species

2.2. Study Site and Sampling

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Analysis of the Change in the Firecrest Breeding Range

3. Results

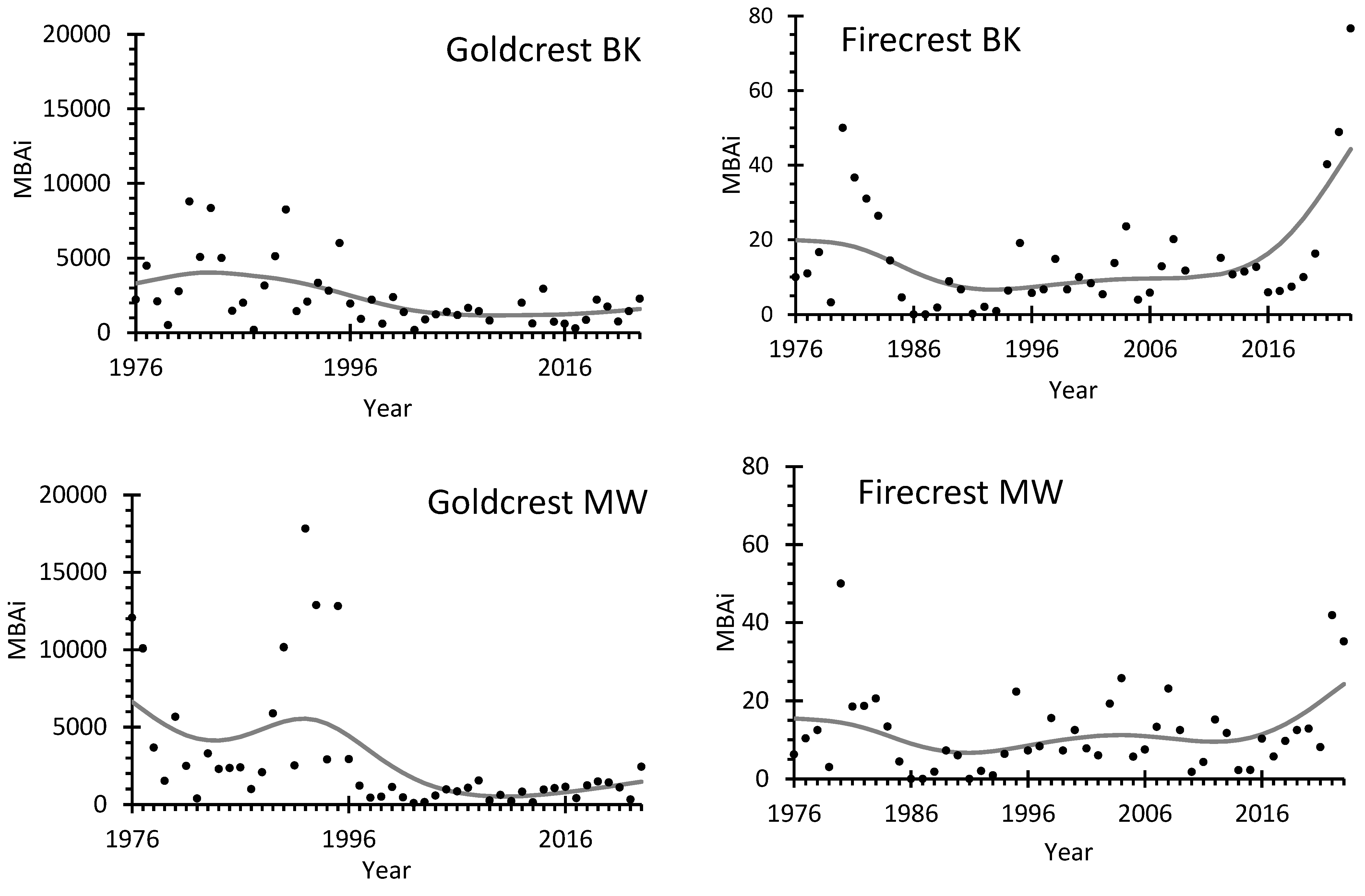

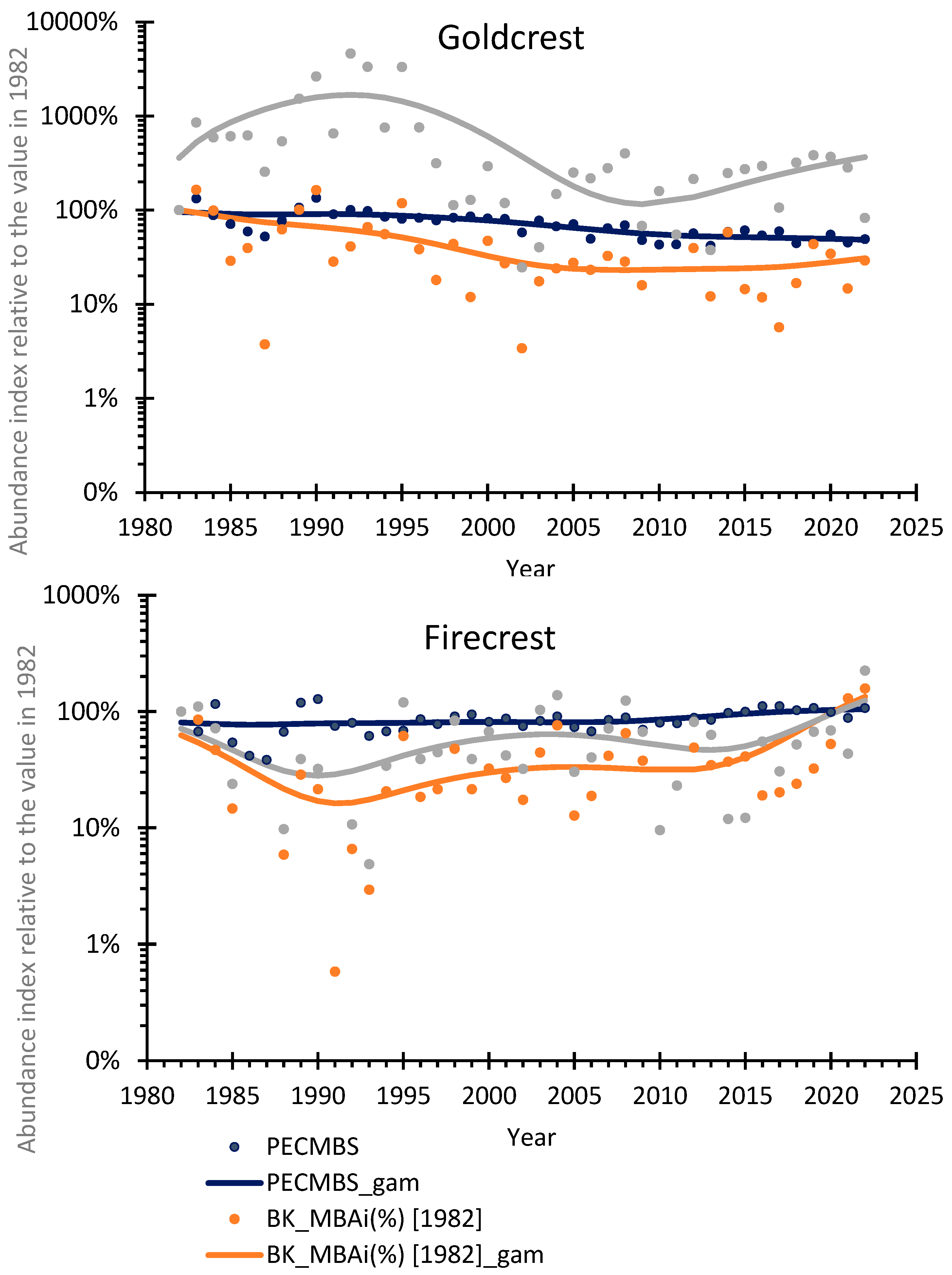

3.1. Abundance of Migrating Goldcrests and Firecrests

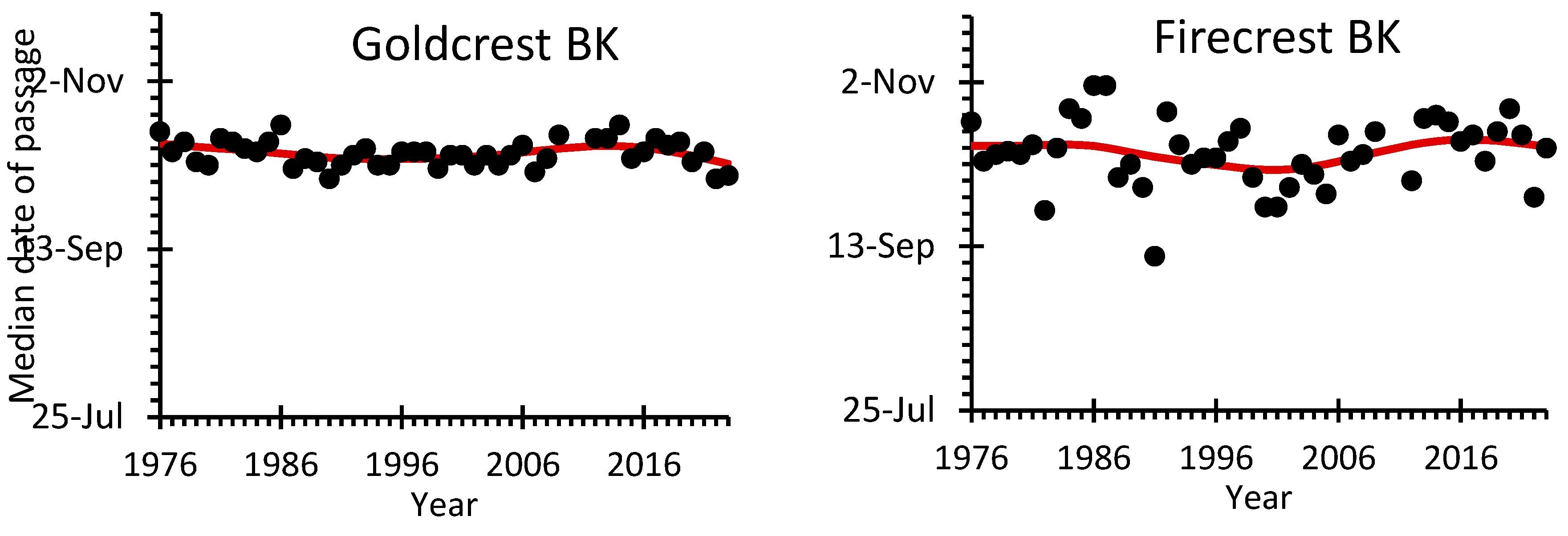

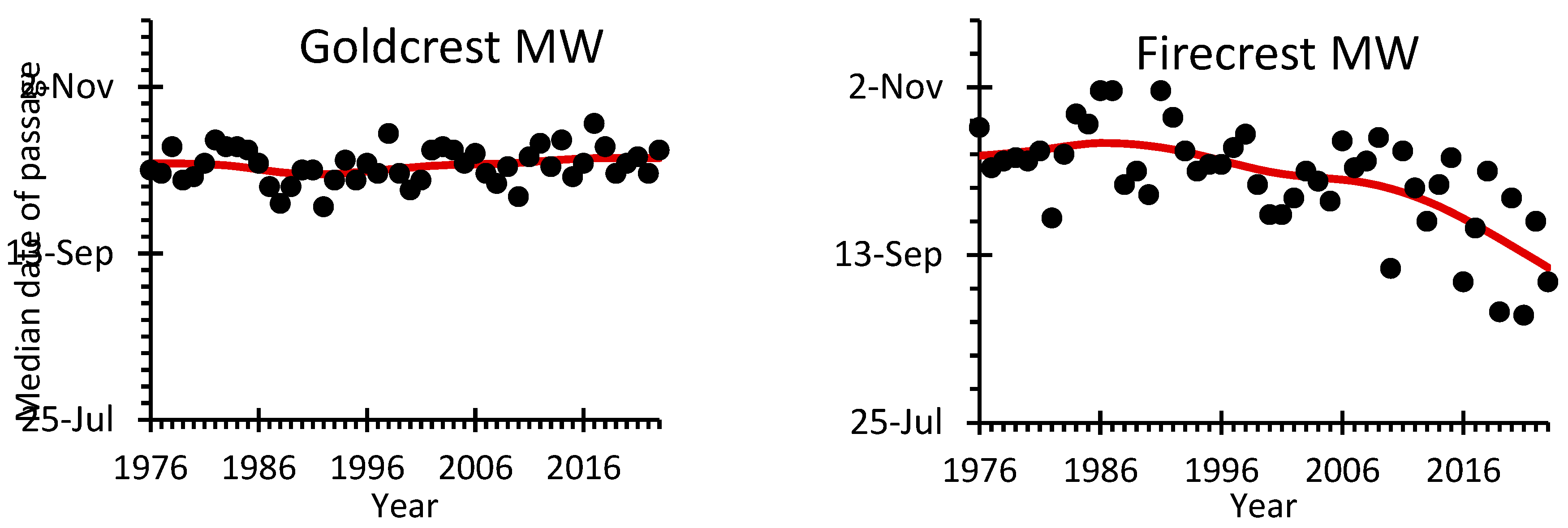

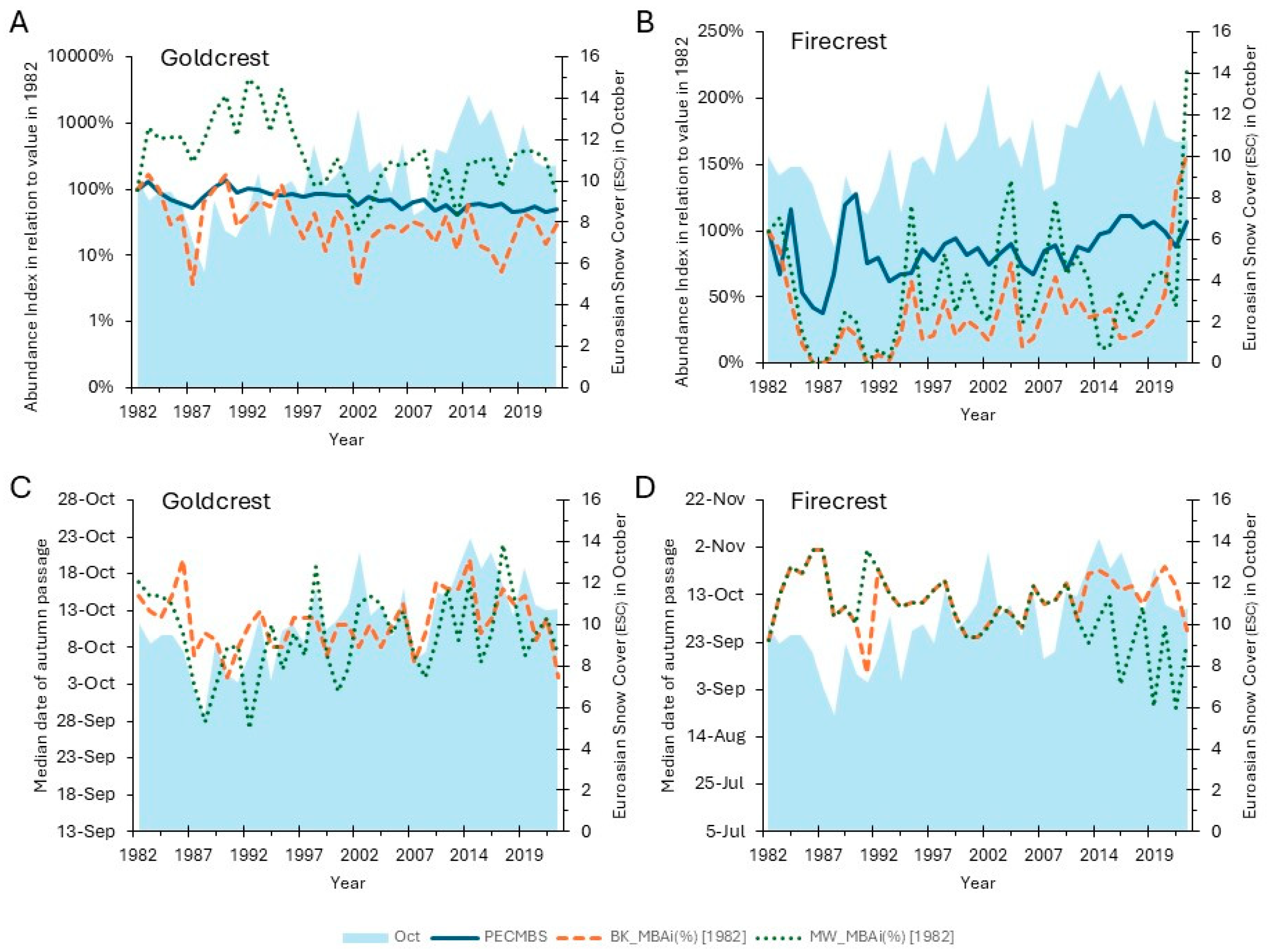

3.2. Autumn Migration Timing of Goldcrests and Firecrests

3.3. Pan-European Breeding Population Trends for Goldcrest and Firecrest

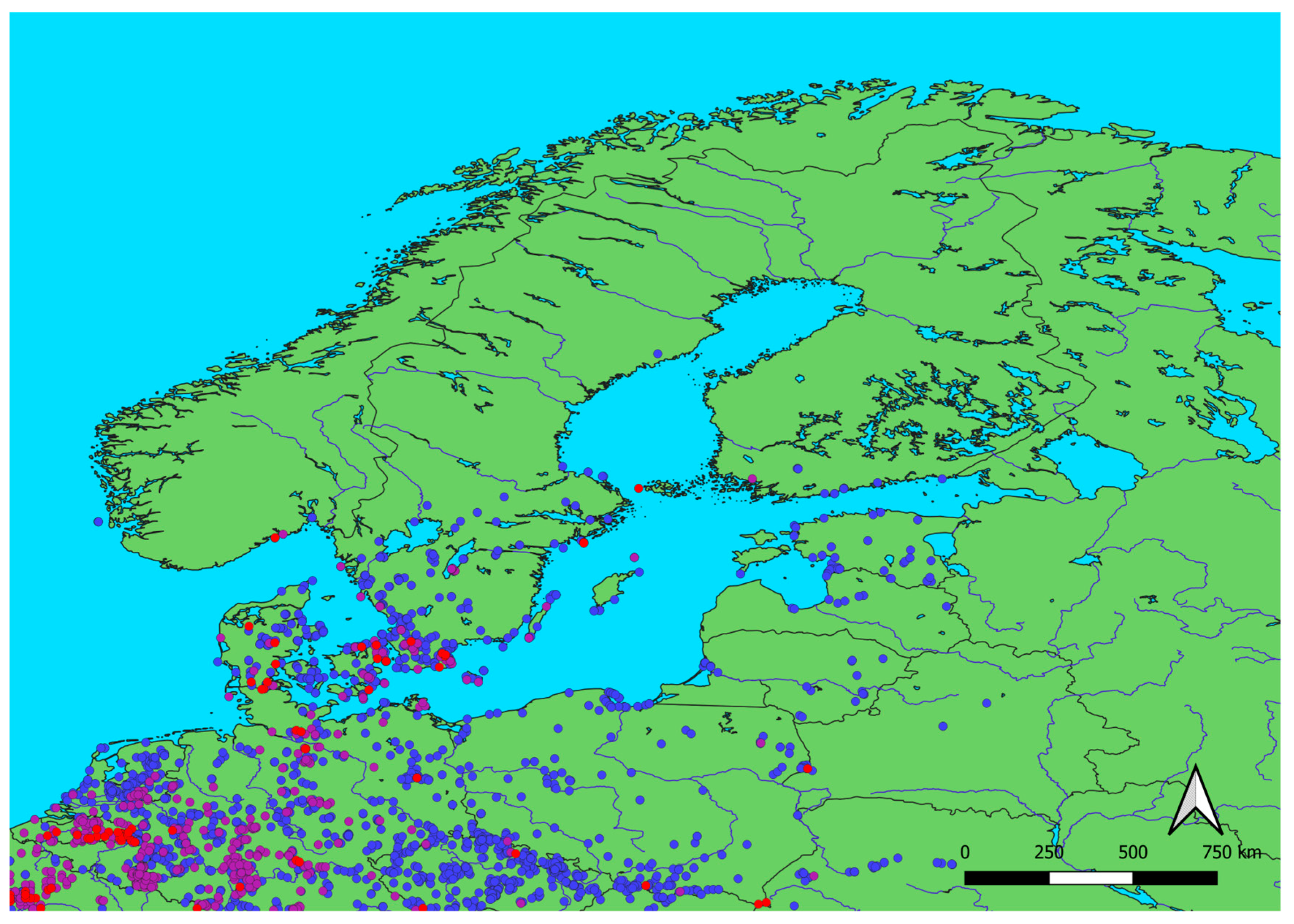

3.4. Changes in Firecrest’s Breeding Range

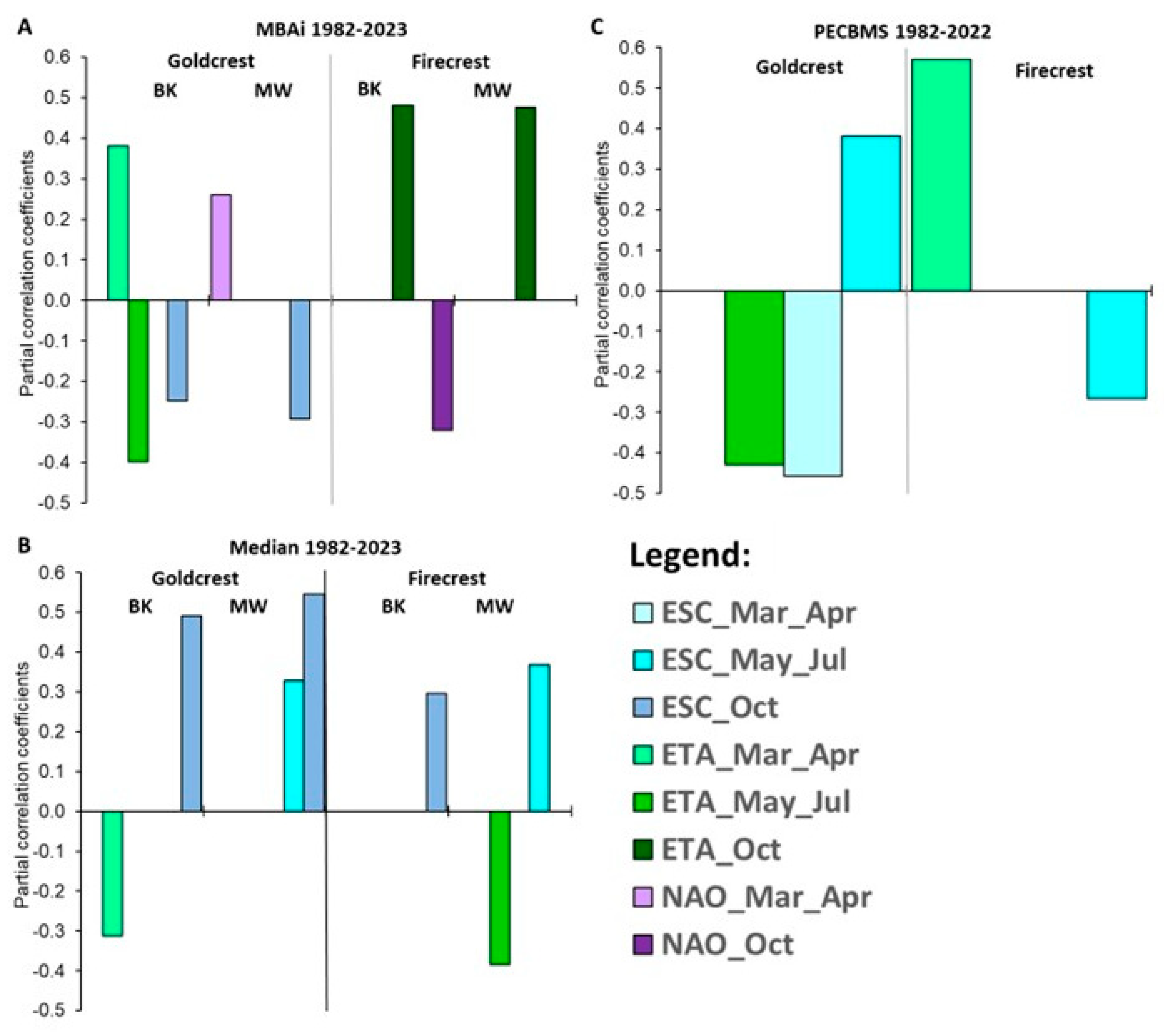

3.4. Influence of Climate Factors on Abundance and Autumn Migration Timing in Goldcrest and Firecrest

4. Discussion

4.1. Multi-Year Trends in Firecrest and Goldcrest Abundance during Breeding and on Autumn

4.2. Effect of Conditions in Spring and Summer on Both Species

4.3. Effect of Autumn Conditions on Both Species

4.3. Effect of Forest Management and Anthropogenic Changes on the Abundance of Goldcrest and Firecrest

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crick, H.Q.P. The Impact of Climate Change on Birds. Ibis 2004, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.E.; Perdeck, A.C.; van Balen, J.H.; Both, C. Climate Change Leads to Decreasing Bird Migration Distances. Glob Chang Biol 2009, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skagen, S.K.; Adams, A.A.Y. Weather Effects on Avian Breeding Performance and Implications of Climate Change. Ecological Applications 2012, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askeyev, O.; Askeyev, A.; Askeyev, I. Recent Climate Change Has Increased Forest Winter Bird Densities in East Europe. Ecol Res 2018, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remisiewicz, M.; Underhill, L.G. Large-Scale Climatic Patterns Have Stronger Carry-Over Effects than Local Temperatures on Spring Phenology of Long-Distance Passerine Migrants between Europe and Africa. Animals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, S.A.; Wiens, J.A.; Bird, C. Bird Populations and Environmental Changes: Can Birds Be Bio-Indicators? American Birds 1989, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, R.D.; Eaton, M.A.; Burfield, I.J.; Grice, P. V.; Howard, C.; Klvaňová, A.; Noble, D.; Šilarová, E.; Staneva, A.; Stephens, P.A.; et al. Drivers of the Changing Abundance of European Birds at Two Spatial Scales. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2023, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crick, H.Q.P.; Baillie, S.R.; Leech, D.I. The UK Nest Record Scheme: Its Value for Science and Conservation. Bird Study 2003, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumbović Mazal, V.B.L.K.J. The Launch of the Common Farmland Bird Monitoring Scheme in Croatia. In Bird census news; Anselin, A., Heldbjerg, H., Eaton, M., Eds.; Research Institute for Nature and Forest, INBO,: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, S. European Bird Monitoring: Geographical Scales and Sampling Strategies. The Ring 2000, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, R.A.; Julliard, R.; Saracco, J.F. Constant Effort: Studying Avian Population Processes Using Standardised Ringing. Ringing and Migration 2009, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.P.; Schnell, G.D. Comparison of Survey Methods for Wintering Grassland Birds. J Field Ornithol 2006, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komenda-Zehnder, S.; Jenni, L.; Liechti, F. Do Bird Captures Reflect Migration Intensity? - Trapping Numbers on an Alpine Pass Compared with Radar Counts. J Avian Biol 2010, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, J. Catch Numbers at Ringing Stations Is a Reflection of Bird Migration Intensity, as Exemplified by Autumn Movements of the Great Tit ( Parus Major ). RING 2003, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, I. Weather-Related Mass-Mortality Events in Migrants. Ibis 2007, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, P.; Meissner, W. Bird Ringing Station Manual; Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG: Warsaw/Berlin, 2015; ISBN 9788376560526. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn, R.B.; Ward, M.; Adams, M.C. The Increasing Firecrest Population in the New Forest, Hampshire. British Birds 2012, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Balmer, D.E.; Gillings, S.; Caffrey, B.J.; Swann, R.L.; Downie, I.S.; Fuller, R.J. Bird Atlas 2007-11: The Breeding and Wintering Birds of Britain and Ireland; BTO Thetford, 2013; ISBN 190858128X.

- Kralj, J.; Flousek, J.; Huzak, M.; Ćiković, D.; Dolenec, Z. Factors Affecting the Goldcrest/Firecrest Abundance Ratio in Their Area of Sympatry. Ann Zool Fennici 2013, 50, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, F.J.; Donald, P.F.; Pain, D.J.; Burfield, I.J.; van Bommel, F.P.J. Long-Term Population Declines in Afro-Palearctic Migrant Birds. Biol Conserv 2006, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramp, S. Volume VI: Warblers. In Handbook of the Birds of Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa: The Birds of the Western Palearctic; Oxford University Press: New York, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, K.; Mitschke, A.; Luniak, M. A Comparison of Common Breeding Bird Populations in Hamburg, Berlin and Warsaw. Acta Ornithol 2005, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, D.; Perrins, C.M. , The Birds of the Western Palearctic Concise Edition; Oxford University Press: Oxford ; New York, 1998; Vol. 2; ISBN 019854099X.

- Leisler, B.; Thaler, E. Differences in Morphology and Foraging Behaviour in the Goldcrest Regulus Regulus and Firecrest Regulus Ignicapillus. Ann Zool Fennici 1982, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Trepte, A. Wintergoldhähnchen - Steckbrief, Verbreitung, Bilder - Avi-Fauna Deutschland. Available online: Https://Www.Avi-Fauna.Info/ (accessed on day month year).

- Remisiewicz, M.; Baumanis, J. Autumn Migration of Goldcrest (Regulus Regulus) at the Eastern Abd Southern Baltic Coast; 1996; Vol. 18;

- Maciąg, T.; Remisiewicz, M.; Nowakowski, J.K.; Redlisiak, M.; Rosińska, K.; Stępniewski, K.; Stępniewska, K.; Szulc, J. Website of the Bird Migration Research Station Http://Www.Sbwp.Ug.Edu.Pl/Badania/Monitoringwyniki/.

- Spina, F.; Baillie, S.R.; Bairlein, F.; Fiedler, W.; Thorup, K. The Eurasian African Bird Migration Atlas. Available Online: Https://Migrationatlas.Org.

- Sokolov, L. V; Markovets, M.Y.; Shapoval, A.P.; Morozov, Y.G. Long-Term Trends in the Timing of Spring Migration of Passerines on the Courish Spit of the Baltic Sea. Avian Ecology and Behaviour 1998, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Tøttrup, A.P.; Thorup, K.; Rahbek, C. Patterns of Change in Timing of Spring Migration in North European Songbird Populations. J Avian Biol 2006, 37, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redlisiak, M.; Remisiewicz, M.; Nowakowski, J.K. Long-Term Changes in Migration Timing of Song Thrush Turdus Philomelos at the Southern Baltic Coast in Response to Temperatures on Route and at Breeding Grounds. Int J Biometeorol 2018, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, P.D. Multiple Regression: A Primer. Stat Med 1999, 20. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. url = {https://www.R-project.org/}.

- Takuya Yanagida Misty: Miscellaneous Functions “T. Yanagida” 2024.

- Jones, P.D.; Jonsson, T.; Wheeler, D. Extension to the North Atlantic Oscillation Using Early Instrumental Pressure Observations from Gibraltar and South-West Iceland. International Journal of Climatology 1997, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental information Climate at a Glance: Global Time Series.

- Estilow, T.W.; Young, A.H.; Robinson, D.A. A Long-Term Northern Hemisphere Snow Cover Extent Data Record for Climate Studies and Monitoring. Earth Syst Sci Data 2015, 7, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J.; et al. Collinearity: A Review of Methods to Deal with It and a Simulation Study Evaluating Their Performance. Ecography 2013, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. Multivariate Linear Models in R: An Appendix to an R Companion to Applied Regression; 2011; Vol. 12;

- Bartoń, K. MuMIn: Multi-Model Inference, Version 1.43.6. R package 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. Ppcor: An R Package for a Fast Calculation to Semi-Partial Correlation Coefficients. Commun Stat Appl Methods 2015, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remisiewicz, M.; Underhill, L.G. Climatic Variation in Africa and Europe Has Combined Effects on Timing of Spring Migration in a Long-Distance Migrant Willow Warbler Phylloscopus Trochilus. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBIF. org GBIF Occurrence Download. 2023.

- QGIS.Org, 3.34.1. QGIS.Org, 3.34.1.2024. QGIS Geographic Information System. Http://Www.Qgis.Org 2023.

- Green, M.; Haas, F.; Lindström, Å.; Nilsson, L. Övervakning Av Fåglarnas Populationsutveckling. Årsrapport För 2020. 2021.

- Both, C.; Bouwhuis, S.; Lessells, C.M.; Visser, M.E. Climate Change and Population Declines in a Long-Distance Migratory Bird. Nature 2006, 441, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickery, J.A.; Ewing, S.R.; Smith, K.W.; Pain, D.J.; Bairlein, F.; Škorpilová, J.; Gregory, R.D. The Decline of Afro-Palaearctic Migrants and an Assessment of Potential Causes. Ibis 2014, 156, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehikoinen, A.; Pakanen, V.M.; Kivinen, S.; Kumpula, S.; Lehto, V.; Rytkönen, S.; Vatka, E.; Virkkala, R.; Orell, M. Population Collapse of a Common Forest Passerine in Northern Europe as a Consequence of Habitat Loss and Decreased Adult Survival. For Ecol Manage 2024, 572, 122283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenni, L.; Kéry, M. Timing of Autumn Bird Migration under Climate Change: Advances in Long-Distance Migrants, Delays in Short-Distance Migrants. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2003, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ożarowska, A.; Meissner, W. Increasing Body Condition of Autumn Migrating Eurasian Blackcaps Sylvia Atricapilla over Four Decades. European Zoological Journal 2024, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozarowska, A.; Zaniewicz, G.; Meissner, W. Spring Arrival Timing Varies between the Groups of Blackcaps (Sylvia Atricapilla) Differing in Wing Length. Ann Zool Fennici 2018, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmore, K.E.; Van Doren, B.M.; Conway, G.J.; Curk, T.; Garrido-Garduño, T.; Germain, R.R.; Hasselmann, T.; Hiemer, D.; Van Der Jeugd, H.P.; Justen, H.; et al. Individual Variability and Versatility in an Eco-Evolutionary Model of Avian Migration: Migratory Strategies of Blackcaps. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2020, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, F.; Berthold, P. Current Selection for Lower Migratory Activity Will Drive the Evolution of Residency in a Migratory Bird Population. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellería, J.L. The Decline of a Peripheral Population of the European Robin Erithacus Rubecula. J Avian Biol 2015, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.E.; Both, C.; Lambrechts, M.M. Global Climate Change Leads to Mistimed Avian Reproduction. Adv Ecol Res 2004, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Van Gils, J.A.; Lisovski, S.; Lok, T.; Meissner, W.; Ozarowska, A.; De Fouw, J.; Rakhimberdiev, E.; Soloviev, M.Y.; Piersma, T.; Klaassen, M. Climate Change: Body Shrinkage Due to Arctic Warming Reduces Red Knot Fitness in Tropical Wintering Range. Science (1979) 2016, 352, 819–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinszke, A.; Remisiewicz, M. Long-Term Changes in Autumn Migration Timing of Garden Warblers Sylvia Borin at the Southern Baltic Coast in Response to Spring, Summer and Autumn Temperatures. European Zoological Journal 2023, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haila, Y.; Tiainen, J.; Fennica, K.V.-O. ; 1986, undefined Delayed Autumn Migration as an Adaptive Strategy of Birds in Northern Europe: Evidence from Finland. ornisfennica.journal.fiY Haila, J Tiainen, K VepsäläinenOrnis Fennica, 1986•ornisfennica.journal.fi.

- Søderdahl, A.S.; Tøttrup, A.P. Consistent Delay in Recent Timing of Passerine Autumn Migration. Ornis Fenn 2023, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, S.E.; Svensson, S.E. Efficiency of Two Methods for Monitoring Bird Population Levels: Breeding Bird Censuses Contra Counts of Migrating Birds. Oikos 1978, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogstad, O. Variation in Numbers, Territoriality and Flock Size of a Goldcrest Regulus Regulus Population in Winter. Ibis 1984, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyurácz, J.; Bánhidi, P.; Góczán, J.; Illés, P.; Kalmár, S.; Koszorús, P.; Lukács, Z.; Molnár, P.; Németh, C.; Varga, L. Annual Captures and Biometrics of Goldcrests Regulus Regulus at a Western Hungarian Stopover Site. The Ring 2021, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, L. V.; Markovets, M.Y.; Morozov, Y.G. Long-Term Dynamics of the Mean Date of Autumn Migration in Passerines on the Courish Spit of the Baltic Sea. Avian Ecology and Behaviour 1999, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tøttrup, A.P.; Thorup, K.; Rahbek, C. Changes in Timing of Autumn Migration in North European Songbird Populations. Ardea 2006, 94, 527–536. [Google Scholar]

- Redlisiak, M.; Remisiewicz, M.; Mazur, A. Sex-Specific Differences in Spring Migration Timing of Song Thrush Turdus Philomelos at the Baltic Coast in Relation to Temperatures on the Wintering Grounds. European Zoological Journal 2021, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.Y.; Mahoney, P.J.; Gurarie, E.; Krikun, N.; Weeks, B.C.; Hebblewhite, M.; Liston, G.; Boelman, N. Behavioral Responses to Spring Snow Conditions Contribute to Long-Term Shift in Migration Phenology in American Robins. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shutt, J.D.; Bell, S.C.; Bell, F.; Castello, J.; El Harouchi, M.; Burgess, M.D. Territory-Level Temperature Influences Breeding Phenology and Reproductive Output in Three Forest Passerine Birds. Oikos 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haftorn, S. Energetics of Incubation by the Goldcrest Regulus Regulus in Relation to Ambient Air Temperatures and the Geographical Distribution of the Species. Ornis Scandinavica 1978, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.E.; Ballinger, T.J.; Euskirchen, E.S.; Hanna, E.; Mård, J.; Overland, J.E.; Tangen, H.; Vihma, T. Extreme Weather and Climate Events in Northern Areas: A Review. Earth Sci Rev 2020, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bison, M.; Yoccoz, N.G.; Carlson, B.; Klein, G.; Laigle, I.; Van Reeth, C.; Asse, D.; Delestrade, A. Best Environmental Predictors of Breeding Phenology Differ with Elevation in a Common Woodland Bird Species. Ecol Evol 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felton, A.; Löfroth, T.; Angelstam, P.; Gustafsson, L.; Hjältén, J.; Felton, A.M.; Simonsson, P.; Dahlberg, A.; Lindbladh, M.; Svensson, J.; et al. Keeping Pace with Forestry: Multi-Scale Conservation in a Changing Production Forest Matrix. Ambio 2020, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulus Ignicapilla: BirdLife International. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020. [CrossRef]

- Regulus Regulus: BirdLife International. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).