1. Introduction

Recent climate change–driven increases in temperature and the frequency of localized heavy rainfall have intensified environmental stress on reforestation species, raising the potential for severe damage [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In particular, drought stress can have a critical impact on the survival of young seedlings planted in open-field conditions [

5,

6]. Such stress leads to physiological impairments, including reduced water-use efficiency, stomatal closure, and suppression of photosynthesis, and in extreme cases, can result in mortality [

7]. However, in sites such as high-altitude or sloped terrains, the installation and maintenance of irrigation systems is challenging, and the ability to respond promptly to weather fluctuations is limited. Therefore, the establishment of seedling production systems that enhance stress adaptability is required to ensure stable rooting and growth.

Conventional forest nursery systems have limited capacity to cope with climate change, and even within the same species, survival rates can vary substantially depending on the planting site conditions. To overcome these challenges, precision nursery technologies that induce stress tolerance from the early growth stage or preselect seedlings with proven resilience are required. In particular, hardening treatments—controlled drought exposure during nursery production—have been reported as an effective strategy for improving drought tolerance [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Such treatments can be implemented more efficiently using ICT-based smart nursery systems capable of environmental monitoring and automated irrigation control [

12,

13,

14]. However, compared to agricultural crops, forest seedlings have different production cycles and economic scales, making direct application of existing smart-farm technologies costly and technically challenging. Consequently, foundational research is needed to guide the development of smart nursery systems tailored to reforestation seedlings.

Non-destructive physiological measurement methods, such as chlorophyll fluorescence and leaf temperature, can detect drought stress earlier than visible symptoms like leaf browning or wilting [

15,

16]. However, these methods require expensive equipment and manual operation, limiting their real-time applicability in conventional nursery systems. Determining the optimal irrigation timing before drought stress reaches a physiological limit is crucial for effective management, and monitoring changes in leaf angle offers a promising approach. Leaf angle is known to be a physical adaptive strategy to environmental stress factors such as light, heat, and water availability [

17]. Under drought stress, stomatal closure and reduced turgor pressure cause leaf wilting, which can be detected before irreversible damage occurs. However, continuous and precise manual measurement of leaf angle in nurseries is impractical. Recently, image-based monitoring of leaf angle has emerged as a low-cost, non-contact approach for assessing plant physiological status [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Leaf angle holds strong potential as an indirect indicator of drought-induced physiological and morphological changes in leaves. Nonetheless, previous research has primarily focused on mature trees in ecological and physiological studies [

17,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], with limited application to seedlings in forest nursery environments [

29,

30,

31]. In particular, there is a need for empirical validation of how well drought-induced changes in leaf angle reflect conventional physiological parameters and how early such changes can be detected. The adoption of early detection and proactive response systems could significantly improve seedling survival rates and enhance irrigation resource efficiency. Therefore, this study conducted a pilot investigation on one-year-old

Quercus acutissima seedlings, simultaneously measuring physiological parameters and image-based leaf angle, to validate the feasibility of using leaf angle variation as a drought stress detection method.

2. Results

2.1. Growth Conditions

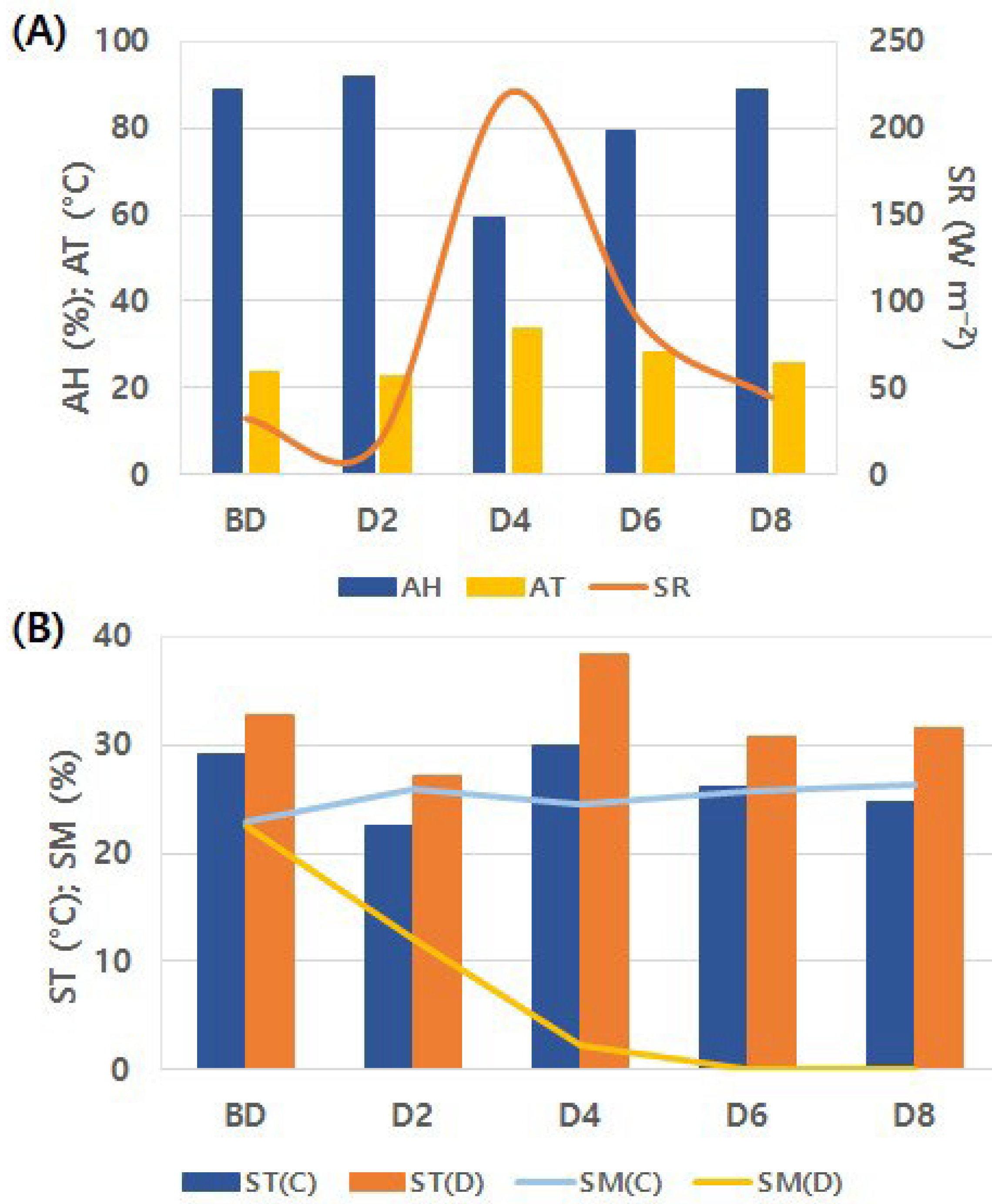

During the experiment, alternating sunny, cloudy, and rainy days resulted in considerable day to day variability in AH, AT, and SR values (

Figure 1A). Among the measurement days, D4 was the only day with clear weather, recording the lowest AH (59.43%) and the highest AT (33.93 °C) and SR (220.39 W m

−2) during the experimental period. From BD to D8, the drought treatment consistently maintained higher ST than the control (average 5.13 ± 2.23 °C) (

Figure 1B). The SM of the control remained at 25.30 ± 1.32% from BD to D8, whereas the SM of the drought treatment continuously declined, reaching 2.19 ± 0.56% on D4 and converging to 0% thereafter.

2.2. Physiological Responses

Physiological parameters showing an interaction effect were Fm′, ΦNO, SPAD, and CWSI (

Table 1). Except for CWSI, all showed main effect for day. The parameters that showed main effect for treatment were Fo′, Fm′, ΦNO, and CWSI.

Overall, chlorophyll fluorescence indicated that both treatments showed sharp increase in stress on D4 (

Table 2). This could be attributed to high light intensity and high temperature on D4 (

Figure 1), which may also explain why the main effect between treatments was not significant. Except for D4, DT showed a consistent decreasing trend over time in certain physiological parameters (Fv′/Fm′, ΦII, ΦNO, ΦNPQ). Parameters that did not exhibit consistent trends over time seemed to be strongly influenced by weather conditions. From D6 onward, physiological parameters such as ΦNO and qL (except Fo′ and Fm′) consistently showed significant differences between treatments, indicating the beginning of drought stress.

2.3. Leaf Angle Variation

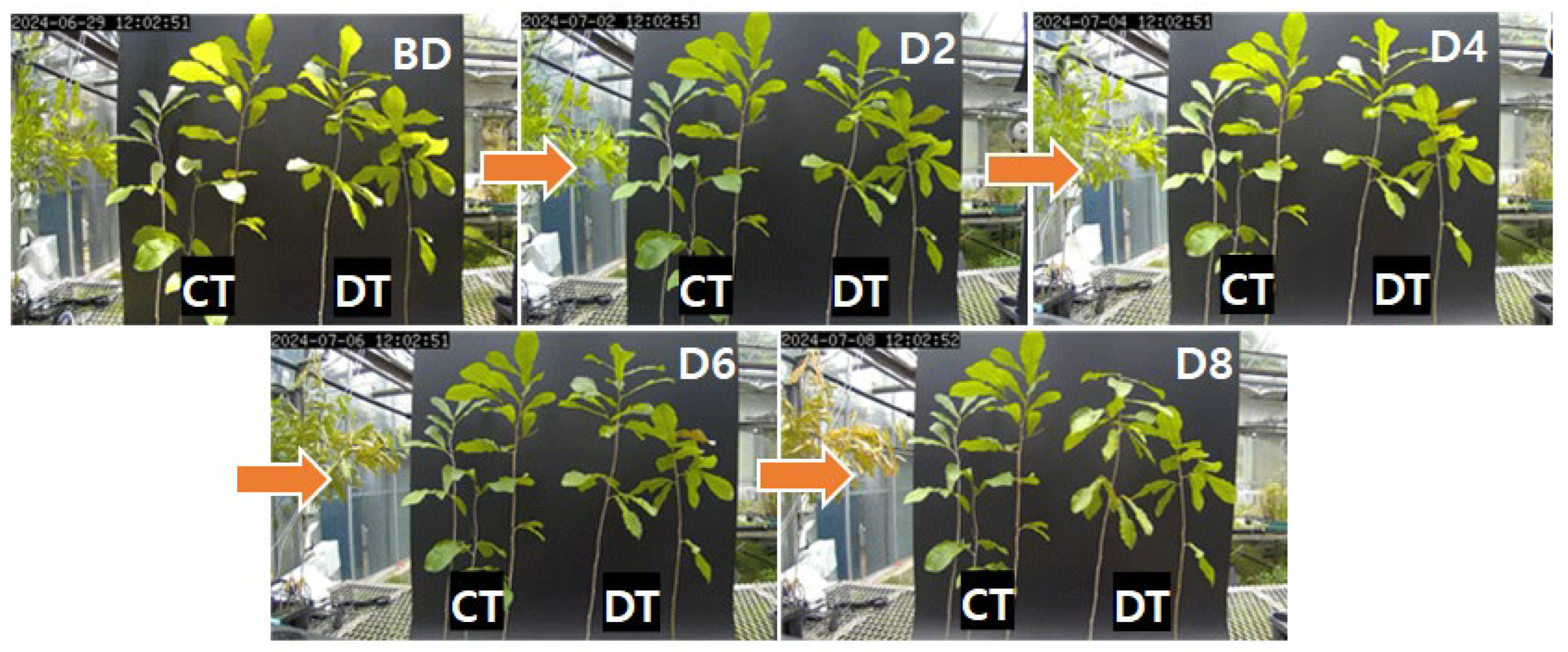

Visual observation revealed that noticeable leaf inclination occurred on D8 (

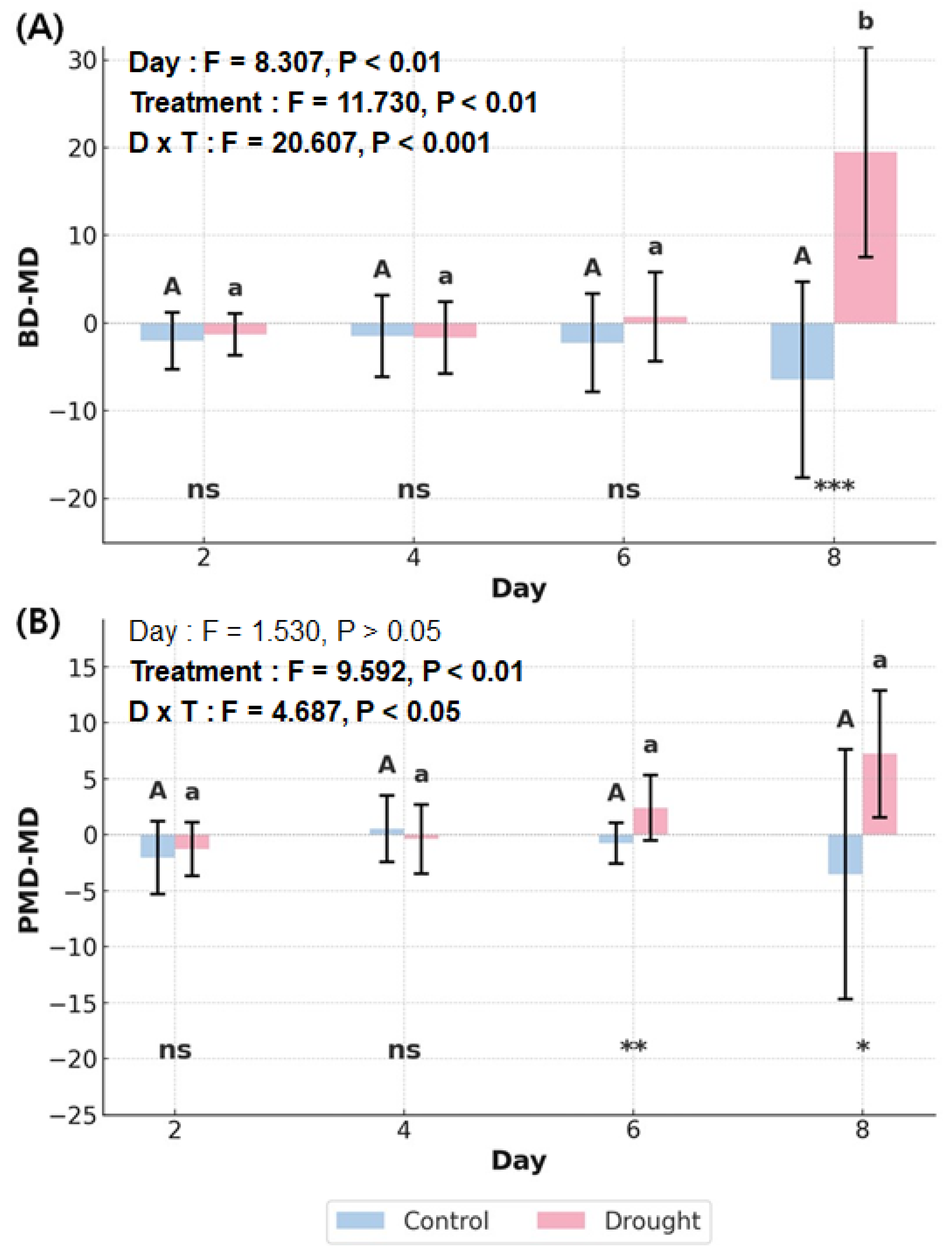

Figure 2). BD–MD exhibited significant interaction and main effects (

Figure 3A), with significant differences between treatments observed from D8 (P < 0.001). PMD–MD showed both interaction effect and main effect for treatment (

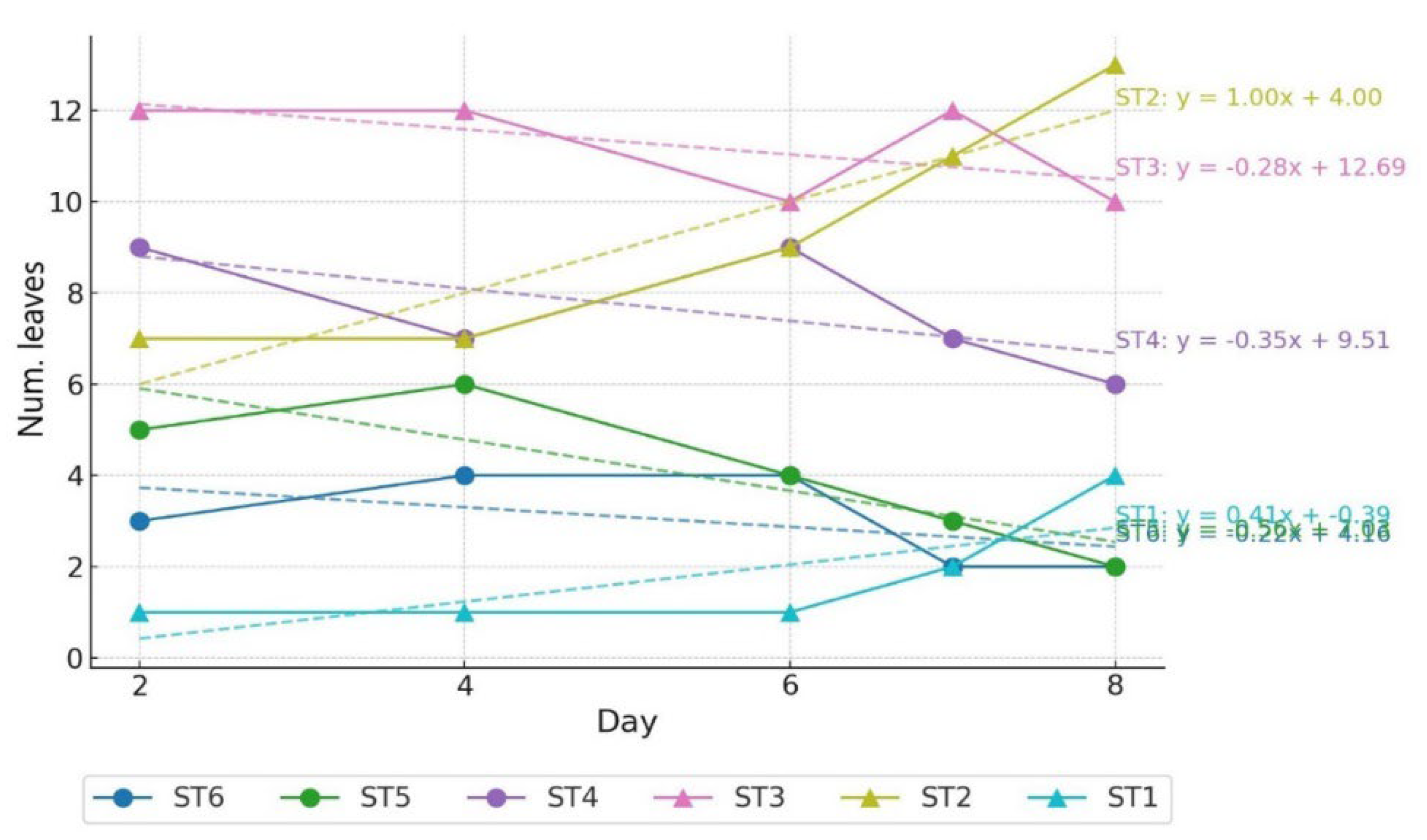

Figure 3B), with significant differences between treatments beginning on D6 (D6: P < 0.01; D8: P < 0.05). This indicates that leaf angle responded to drought stress at a timing similar to physiological responses. In contrast, no significant differences were found over time (P > 0.05). These results suggest that statistical significance can vary depending on the leaf angle parameter used. In DT, ST1 and ST2, which were within the negative angle range, exhibited an upward trend over time (

Figure 4), with ST2 showing the greatest increase (y = 1.00x + 4.00). In contrast, ST5 showed the most pronounced decline (y = –0.56x + 7.03).

2.4. Relationship Between Physiological and Leaf Angle Parameters

The BD–MD model (adjusted R

2 = 0.389) exhibited relatively higher stability in explanatory power compared to the PMD–MD model (adjusted R

2 = 0.242) (

Table 3). However, since both models had R

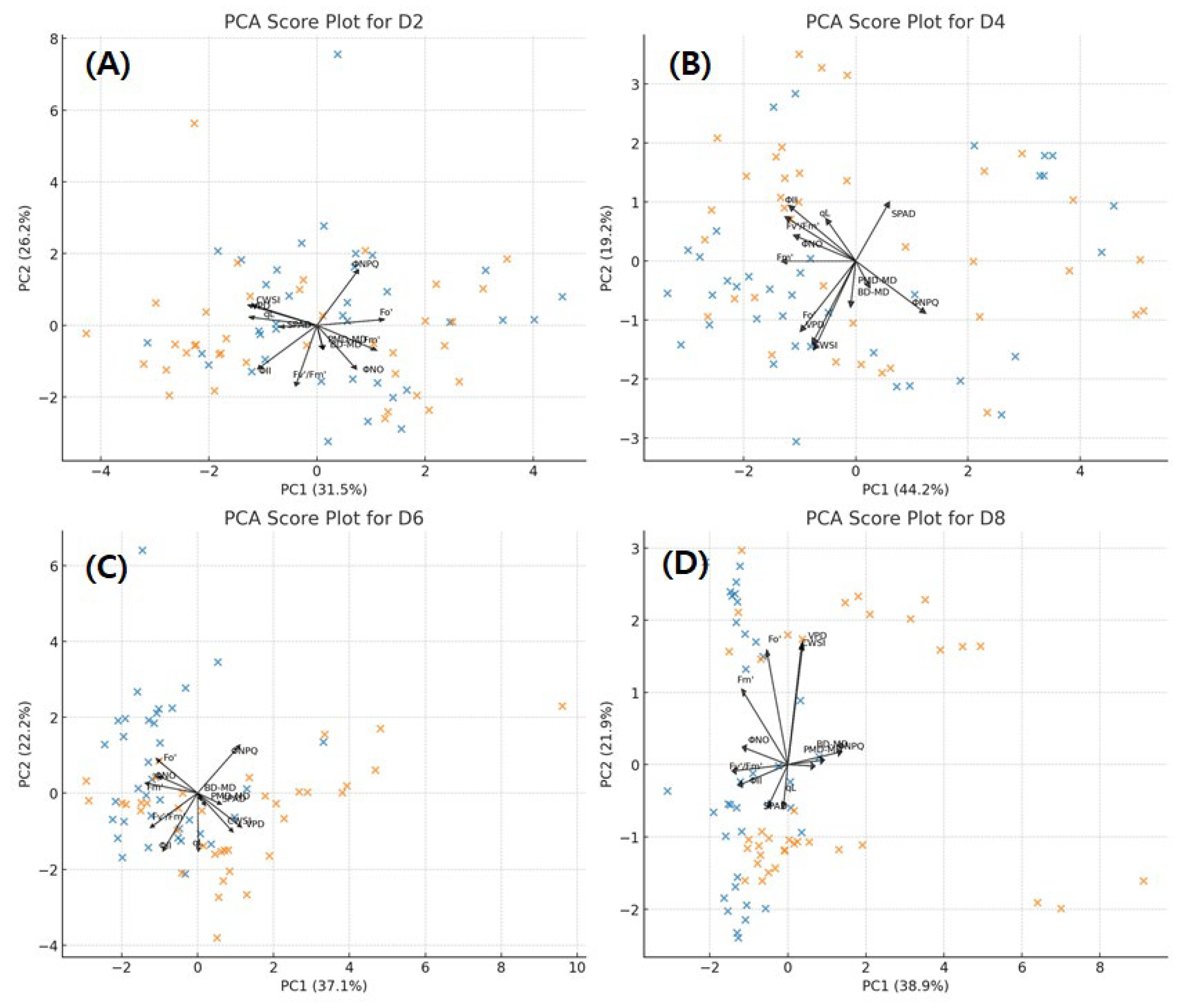

2 values below 0.5, they were appropriate for identifying general trends but could not be considered highly predictive. The addition of new variables contributed to increase in explanatory power (Sig. F change < 0.05). The Durbin–Watson (DW) values were close to 2, indicating minimal DW values were close to 2, indicating minimal autocorrelation. Significant variables selected in both models included SM, AT, Fm′, and VPD. Except for Fm′, most of these were environmental factors (AT, VPD, SM), which were identified as key drivers influencing leaf angle. In particular, AT (BD–MD standardized coefficient β = –1.079; PMD–MD standardized coefficient β = –0.672) exerted the strongest influence (negative) on both leaf angle parameters. PCA results showed that CT and DT overlapped in the score plots on D2 and D4 but exhibited clear separation between treatments from D6 onward (

Figure 5). In the loading plot, the direction of the leaf angle parameters along PC1 appeared to contribute to the separation between the two treatments.

3. Discussion

3.1. Physiological Responses of Q. acutissima to Drought Stress

In contrast to this study, previous studies have shown that 1–2-year-old

Q. acutissima seedlings can survive beyond 30 days of drought treatment [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Up to 30 days of drought, no significant differences in chlorophyll content between irrigated and drought-treated seedlings have been observed, and chlorophyll fluorescence responses also showed minimal variation [

32,

35]. Before rewatering, leaves exhibited visible wilting, but recovery was observed following rewatering [

35,

36]. Thermal imaging further confirmed that leaf temperatures returned to pre-drought levels after rewatering [

35]. Although the seedlings did not die, leaf abscission occurred progressively over time, while surviving leaves tended to recover in photosynthetic parameters [

36]. These studies consistently indicate that, even under DT, SM levels remained higher than in this study, and recovery upon rewatering was possible as long as SM did not reach 0%. According to Lim et al. [

32], SM dropped below 1% after 30 days, after which drought stress responses were detected in chlorophyll fluorescence (Fv/Fm). This is consistent with the findings of this study, in which drought stress symptoms appeared when SM approached 0%. Further investigation is therefore required to determine whether leaf recovery can occur following rewatering once SM has reached 0%. Even when leaf recovery was slow, Wang et al. [

34] reported that stem starch concentrations increased 60 days after defoliation, suggesting an enhancement of drought tolerance through resource reallocation strategies. Liu et al. [

37] observed that nutrient supplementation under drought conditions mitigated structural damage to leaves and maintained physiological functions, thereby alleviating drought stress. From physiological perspective, such effects could reduce leaf mortality, mitigate growth reduction, and enhance the feasibility of leaf-based drought stress detection. According to Li et al. [

33], hardening treatment in

Q. acutissima improved drought readaptation capacity by enhancing photosynthetic performance, activating carbon consumption reduction strategies, and increasing the fine-to-coarse root ratio. These findings highlight

Q. acutissima as suitable species for developing drought stress detection technologies applicable to future nursery systems.

3.2. Potential Applications of Leaf Angle Measurement

This study confirmed that changes in leaf angle closely align with physiological responses of seedlings to drought stress. Leaf angle is known to significantly influence various physiological processes, including suppression of excessive light saturation, prevention of leaf temperature rise, protection of the photosynthetic apparatus, activation of the xanthophyll cycle, and improvement of photosynthetic efficiency [

38]. In some species, inherent leaf angles serve as an adaptive strategy for enhancing survival [

26]. Under nursery conditions, seedlings with positive mean leaf angle exhibited significantly improved physiological responses even under reduced irrigation, whereas those with negative mean leaf angle required greater irrigation inputs [

29,

30]. In conifers such as larch, upper needles exhibited more rapid wilting response compared to broadleaved species, and drought stress symptoms were detectable earlier than physiological changes [

31]. These findings suggest that monitoring strategies based on leaf angle should be adapted to species-specific traits. When applied in practice, individual leaf angle analysis can identify areas within the greenhouse that are subject to the highest levels of drought and heat stress. These high-stress areas are likely to endure the most severe stress, while other areas remain relatively less affected, thereby reducing the risk of mortality.

Recent advances in machine learning and deep learning techniques have enhanced the precision of image-based leaf angle analysis [

20,

21]. For example, Qi et al. [

20] applied Pyramid Convolutional Neural Network (PCNN) to smartphone images of

Euonymus japonicus Thunb., effectively estimating leaf azimuth with high accuracy, as indicated by strong R

2 values, thus demonstrating its field applicability. Several other studies have also reported methods for measuring leaf angle distributions in various plant and crop species [

18,

19]. Jiang et al. [

22] developed the Auto-LIA (leaf inclination angle) system, which integrates RGB imaging with computer vision techniques to achieve fully automated LIA measurement based on leaf–plant connectivity and 3D spatial information. This approach offers advantages of low cost and high precision, highlighting its potential for plant physiological monitoring and phenotyping. Furthermore, leaf angle datasets can be utilized for calibration modeling to improve measurement accuracy, and the data collected in this study are also expected to contribute to the development of future application technologies [

30,

39].

3.3. Limitation and Future Study

This study was conducted only in July, and thus did not account for variations in leaf angle across different seasons or leaf development stages. Previous studies have reported seasonal changes in mean leaf angle [

17,

27]. Therefore, increasing the number of replicates for different time periods, and creating separate datasets based on leaf position and weather conditions, would enable more accurate leaf angle analysis through modeling. Additionally, because leaf angle changes occur in three-dimensional space, measuring only from the side may overlook important azimuth information. Simultaneous detection of changes from the top view could provide more precise drought stress detection when integrated into modeling approaches. Finally, to enhance field applicability, future research should include rewatering experiments and expand measurement and analysis methods from the individual leaf scale to containerized seedlings.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant materials

One-year-old Q. acutissima seedlings used in this study were produced in the greenhouse of Forest Technology and Management Research Center (37°45’39”N, 127°10’13”E). In April 2024, seeds were sown in containers (top Ø6.4 cm × bottom Ø4.2 cm × height 14 cm, cell volume 320 mL, 24 cells per tray) filled with growth medium composed of peat moss, perlite, and vermiculite at 1:1:1 (v/v) ratio. Irrigation was applied daily at 20 L m−2 via sprinkler system. Fertilization was applied once per week using 1 g L−1 (1,000 ppm) solution of MultiFeed 19 (19N:19P2O5:19K2O; Haifa Chemicals, Haifa, Israel). From June until the start of the experiment, seedlings were transferred to the greenhouse of Kangwon National University, College of Forest and Environmental Sciences (37°52’00”N, 127°44’51”E) and acclimated under the same irrigation regime.

4.2. Experimental Conditions

Seedlings were randomly assigned to control (CT, n = 7) and drought treatment (DT, n = 6). Seedlings were positioned so that each image frame contained CT (n = 2–3) and DT (n = 2) seedlings, with a black background board placed behind them. CT received 2.35 L of water per container, applied directly to the soil with a watering can between 11:00 AM and 12:00 PM daily. DT (no irrigation) was applied from July 1 (D1) to July 8 (D8). Air temperature (AT), air humidity (AH), and solar radiation (SR) in the greenhouse were recorded every 10 min using Juns OL sensors (PurumBio, Suwon, Korea). Soil temperature (ST) and soil moisture (SH) were measured by inserting temperature sensor (S-SMDM005, Onset, Bourne, MA, USA) and moisture sensor (S-TMB-M002, Onset, Bourne, MA, USA) into the growth medium. Data were collected at 30 min intervals using Hobo micro station (H21-USB, Onset, Bourne, MA, USA).

4.3. Physiological Measurements

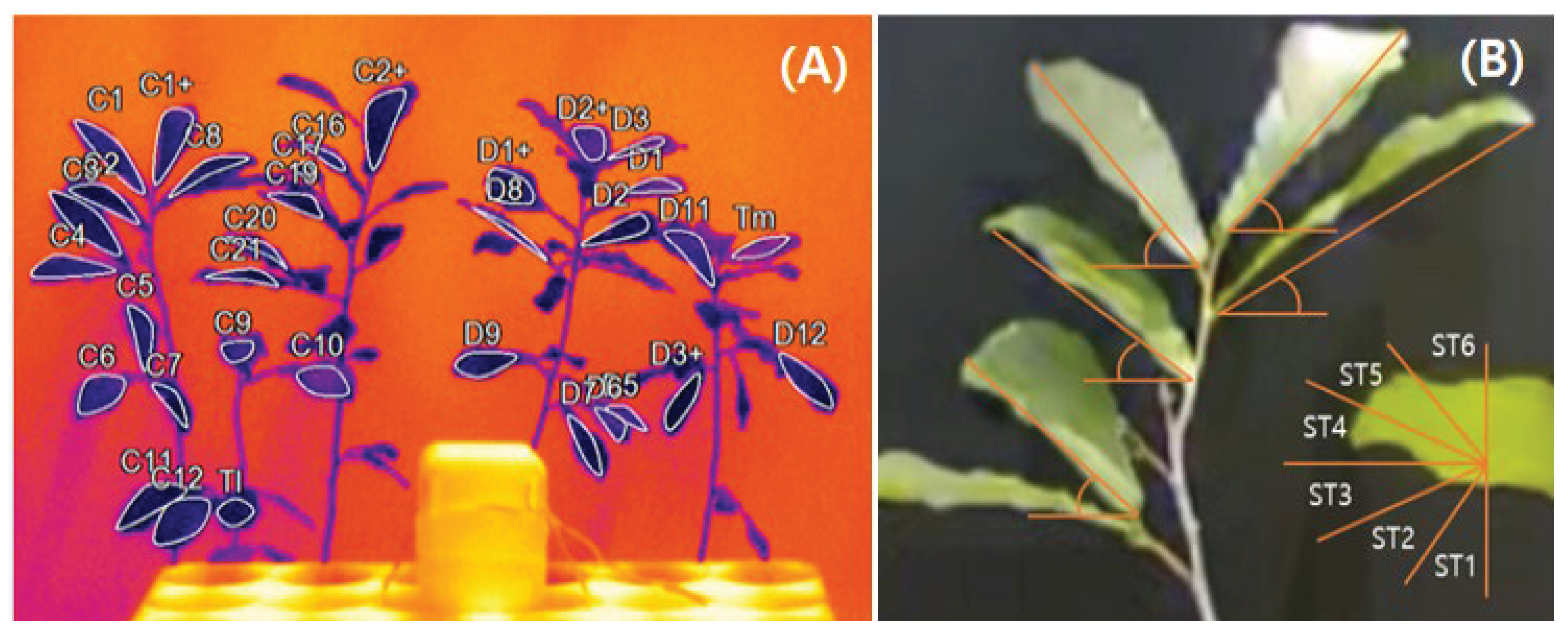

Prior to measurements, leaves (n = 37) from each treatment (CT and DT) were labeled for measurement. The measured parameters included chlorophyll index (SPAD), chlorophyll fluorescence (Fm′: maximum fluorescence in light-adapted state; Fo′: minimum fluorescence in light-adapted state; Fv′/Fm′: maximum quantum yield of PSII in light-adapted state; ΦII: quantum yield of PSII; ΦNO: quantum yield of non-regulated energy dissipation; ΦNPQ: quantum yield of regulated energy dissipation; qL: fraction of open PSII reaction centers), vapor pressure deficit (VPD), and crop water stress index (CWSI). SPAD and chlorophyll fluorescence were measured with MultispeQ V2.0 device (PhotosynQ, East Lansing, MI, USA) between 12:00 PM and 6:00 PM. Leaf temperature data for VPD and CWSI calculations were collected using thermal camera (PI 160i, Optris, Berlin, Germany) positioned 2–3 m from the seedlings, with 10-min recordings (n = 3) taken daily (

Figure 6A). The equations for calculating VPD and CWSI followed Gardner et al. [

40], Stull [

41], Grossiord et al. [

42], and Zhou et al. [

43] (Equations 1,2).

Tl refers to leaf temperature, Ta to air temperature, Tlw to minimum leaf temperature, Tld to maximum leaf temperature, Taw to minimum air temperature, and Tad to maximum air temperature.

4.4. Leaf Angle Measurements

Leaf angle was measured using time-lapse camera (ATL200S, Afidus, New Taipei City, Taiwan) that captured RGB images (16:9 ratio) at 10 min intervals (n = 3). To capture all labeled leaves within a single frame, images were taken from a height of 70 cm above the base of the target pot and 60 cm away from the seedlings. To minimize image distortion, all wide-angle, digital zoom, image stabilization, and auto-exposure optimization functions were disabled. RGB images were analyzed in ImageJ ver. 1.53k (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) to extract leaf angle data. Leaf angle was defined as the internal angle formed between horizontal reference line drawn from the petiole and line from the petiole to the leaf tip (

Figure 6B). Leaves pointing upward were assigned angles between 0° and +90°, while downward-facing leaves were assigned between −90° and 0°. Collected leaf angle data were processed into leaf angle parameters according to equations 3, 4, and 5.

4.5. Statistical Analyses

To assess the effects of DT on temporal and treatment-based variations in physiological parameters and leaf angle, two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (RMANOVA) was performed. Post-hoc pairwise t-tests with Bonferroni correction (P < 0.05) were used. Stepwise multiple regression analysis was conducted to identify factors determining leaf angle variation, with leaf angle parameters as dependent variables and physiological parameters as independent variables. Multicollinearity among predictors was checked using tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF) values. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to visualize variations in physiological and leaf angle characteristics across measurement days and to identify contributing factors. RMANOVA and regression analyses were conducted using SPSS ver. 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). PCA was performed in Python using the scikit-learn PCA module ver. 1.3.0, with StandardScaler applied to normalize all numerical data to account for differences in variable scales. Results were visualized as score plots for PC1 and PC2 using matplotlib ver. 3.7.2, and variable contributions were displayed as loading vectors.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that image-based monitoring of leaf angle can detect drought-induced changes in Q. acutissima seedlings, showing temporal dynamics comparable to conventional physiological stress indicators. PMD-MD, like physiological parameters, showed significant differences between treatments starting on D6, but it did not allow for earlier detection. Multiple regression models indicated that environmental variables, especially AT and SM, were strong determinants of leaf angle variation under drought conditions. Future studies should account for temporal variability (e.g., seasonal changes, leaf development stages), incorporate multi-view imaging capable of capturing both inclination and azimuth changes, and expand to large-scale containerized seedling systems, including rewatering experiments, to validate field applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.J., S.H.H. and E.J.C.; methodology, U.J.; validation, U.J. and D.K.; formal analysis, U.J. and D.K.; investigation, U.J., D.K., S.K. and J.P.; resources, S.H.H.; data curation, U.J. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, U.J.; writing—review and editing, U.J.; visualization, U.J.; supervision, U.J. and E.J.C.; project administration, E.J.C.; funding acquisition, S.H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Forest Science, grant number SC0300-2023-01-2024.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arnell, N.W.; Lowe, J.A.; Challinor, A.J.; Osborn, T.J. Global and regional impacts of climate change at different levels of global temperature increase. Clim. Change. 2019, 155, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes-Silva, P.E.; Loram-Lourenço, L.; Alves, R.D.F.B.; Sousa, L.F.; Almeida, S.E.D.S.; Farnese, F.S. Different ways to die in a changing world: Consequences of climate change for tree species performance and survival through an ecophysiological perspective. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 11979–11999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Jung, S.Y.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, H.S. The Characteristics and survival rates of evergreen broad-leaved tree plantations in Korea. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 2019, 108, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, H.J.; Ali, H.; Allan, R.P.; Ban, N.; Barbero, R.; Berg, P.; Blenkinsop, S.; Cabi, N.S.; Chan, S.; Dale, M.; Dunn, R.J.H.; Ekström, M.; Evans, J.P.; Fosser, G.; Golding, B.; Guerreiro, S.B.; Hegerl, G.C.; Kahraman, A.; Kendon, E.J.; Lenderink, G.; Lewis, E.; Li, X.; O’Gorman, P.A.; Orr, H.G.; Peat, K.L.; Prein, A.F.; Pritchard, D.; Schär, C.; Sharma, A.; Stott, P.A.; Villalobos-Herrera, R.; Villarini, G.; Wasko, C.; Wehner, M.F.; Westra, S.; Whitford, A. Towards advancing scientific knowledge of climate change impacts on short-duration rainfall extremes. Philos. trans., Math. phys. eng. sci. 2021, 379, 20190542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisichelli, N.; Wright, A.; Rice, K.; Mau, A.; Buschena, C.; Reich, P.B. First-year seedlings and climate change: species-specific responses of 15 North American tree species. Oikos 2014, 123, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechergui, T.; Pardos, M.; Jacobs, D.F. Effect of acorn size on survival and growth of Quercus suber L. seedlings under water stress. Eur. J. For. Res. 2021, 140, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Hussain, M.; Wahid, A.; Siddique, K.H.M. Drought stress in plants: an overview. Plant responses to drought stress: From morphological to molecular feature. In Plant Responses to Drought Stress; Aroca, R., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Berlin, 2012; pp. 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah, M.B.; Methenni, K.; Nouairi, I.; Zarrouk, M.; Youssef, N.B. Drought priming improves subsequent more severe drought in a drought-sensitive cultivar of olive cv. Chétoui. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 221, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Zhang, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yang, X.; Wu, L.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Jing, Q.; Shen, J.; Fan, Y.; Xu, W.; Hou, H.; Zhu, X. Drought priming at seedling stage improves photosynthetic performance and yield of potato exposed to a short-term drought stress. Plant Physiol. 2024, 292, 154157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puértolas, J.; Villar-Salvador, P.; Andivia, E.; Ahuja, I.; Cocozza, C.; Cvjetković, B.; Devetaković, J.; Diez, J.J.; Fløistad, I.S.; Ganatsas, P.; Mariotti, B.; Tsakaldimi, M.; Vilagrosa, A.; Witzell, J.; Ivetić, V. Die-hard seedlings. A global meta-analysis on the factors determining the effectiveness of drought hardening on growth and survival of forest plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 572, 122300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toca, A.; Gonzalez-Benecke, C.A.; Nelson, A.S.; Jacobs, D.F. Drought memory expression varies across ecologically contrasting forest tree species. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2025, 231, 106094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Et-Taibi, B.; Abid, M.R.; Boufounas, E.M.; Morchid, A.; Bourhnane, S.; Hamed, T.A.; Benhaddou, D. Enhancing water management in smart agriculture: A cloud and IoT-Based smart irrigation system. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Park, S.; Youn, H.; Lee, J.; Kwon, S. Implementation of smart farm systems based on fog computing in artificial intelligence of things environments. Sensors 2024, 24, 6689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younes, A.; Abou Elassad, Z.E.; El Meslouhi, O.; Abou Elassad, D.E.; Majid, E.D.A. The application of machine learning techniques for smart irrigation systems: A systematic literature review. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 7, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itam, M.; Hall, D.; Kramer, D.; Merewitz, E. Early detection of Kentucky bluegrass and perennial ryegrass responses to drought stress by measuring chlorophyll fluorescence parameters. Crop Sci. 2024, 64, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Zhang, Y.C.; Hou, Y.L. Assessing water status in rice plants in water-deficient environments using thermal imaging. Bot. Stud. 2025, 66, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Li, R.; Jablonski, A.; Stovall, A.; Kim, J.; Yi, K.; Ma, Y.; Beverly, D.; Phillips, R.; Novics, k.; Xu, X.; Lerdau, M. Leaf angle as a leaf and canopy trait: Rejuvenating its role in ecology with new technology. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X.; Mõttus, M.; Tammeorg, P.; Torres, C.L.; Takala, T.; Pisek, J.; Mäkelä, P.; Stoddard, F.L.; Pellikka, P. Photographic measurement of leaf angles in field crops. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 184, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Linow, M.; Pinto-Espinosa, F.; Scharr, H.; Rascher, U. The leaf angle distribution of natural plant populations: assessing the canopy with a novel software tool. Plant methods 2015, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Xie, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, W.; Mu, X.; Yan, G. Estimating leaf angle distribution from smartphone photographs. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. 2019, 16, 1190–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenchanmane Raju, S.K.; Adkins, M.; Enersen, A.; Santana de Carvalho, D.; Studer, A.J.; Ganapathysubramanian, B.; Schnable, P.S.; Schnable, J.C. Leaf Angle eXtractor: A high-throughput image processing framework for leaf angle measurements in maize and sorghum. Appl. Plant Sci. 2020, 8, e11385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wu, X.; Wang, Q.; Pei, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jin, J.; Guo, Y.; Song, R.; Zang, L.; L, Y.J.; Hao, G. Auto-LIA: The automated vision-based leaf inclination angle measurement system improves monitoring of plant physiology. Plant Phenomics 2024, 6, 0245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.A. The functional significance of leaf angle in Eucalyptus. Aust. J. Bot. 1997, 45, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, A.; Toma, T.; Marjenah, M. Leaf gas exchange and cholorphyll fluorescence in relation to leaf angle, azimuth, and canopy position in the tropical pioneer tree, Macaranga conifera. Tree Physiol. 1999, 19, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada, J.M.; Lechowicz, M.J.; Kitajima, K. Optimal photosynthetic use of light by tropical tree crowns achieved by adjustment of individual leaf angles and nitrogen content. Ann. Bot. 2009, 103, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mänd, P.; Hallik, L.; Peñuelas, J.; Kull, O. Electron transport efficiency at opposite leaf sides: effect of vertical distribution of leaf angle, structure, chlorophyll content and species in a forest canopy. Tree Physiol. 2013, 33, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, K.; Pisek, J.; Sonnentag, O.; Annuk, K. Variations of leaf inclination angle distribution with height over the growing season and light exposure for eight broadleaf tree species. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 214, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemeier, M.; Leuschner, C. Functional crown architecture of five temperate broadleaf tree species: Vertical gradients in leaf morphology, leaf angle, and leaf area density. Forests 2019, 10, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L.G.M.; da Silva, R.B.G.; Gabira, M.M.; Rodrigues, A.L.; Simões, D.; de Almeida, L.F.R.; da Silva, M.R. Mean leaf angles affect irrigation efficiency and physiological responses of tropical species seedling. Forests 2022, 13, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, R.B.G.; Simões, D.; Wendling, I.; do Prado, D.Z.; Sartori, M.M.P.; Bertholdi, A.A.D.S.; da Silva, M.R. Leaf Angle as a Criterion for Optimizing Irrigation in Forest Nurseries: Impacts on Physiological Seedling Quality and Performance after Planting in Pots. Forests 2023, 14, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, U.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; Han, S.H.; Cheong, E.J. Needle angle dynamics as a rapid indicator of drought stress in Larix kaempferi (Lamb.) Carrière: advancing non-destructive imaging techniques for resilient seedling production. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1550748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Kang, J.W.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.; Lee, W.Y. Growth and physiological responses of Quercus acutissima seedling under drought stress. Plant Breed. Biotechnol. 2017, 5, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, X.; Sun, X.; Zhao, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, N.; Gao, Q.; Fan, P.; Du, N.; Wang, H.; Wang, R. Effects of drought hardening on the carbohydrate dynamics of Quercus acutissima seedlings under successional drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1184584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Song, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, P.; Qi, L.; Song, H.; Du, N.; Wang, H.; Zheng, P.; Wang, R. Physiological responses of Quercus acutissima and Quercus rubra seedlings to drought and defoliation treatments. Tree Physiol. 2023, 43, 737–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.L.; Oh, C.; Denison, M.I.J.; Natarajan, S.; Lee, K.; Lim, H. Transcriptomic and physiological responses of Quercus acutissima and Quercus palustris to drought stress and rewatering. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1430485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Guo, H.; Yan, L.P.; Gao, L.; Zhai, S.; Xu, Y. Physiological, photosynthetic and stomatal ultrastructural responses of quercus acutissima seedlings to drought stress and rewatering. Forests 2023, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Sun, X.; Yi, S.; Wu, P.; Wang, N. Nutrition addition alleviates negative drought effects on Quercus acutissima seedlings. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 562, 121980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.X.; Xu, S.M.; Woo, K.C. Influence of leaf angle on photosynthesis and the xanthophyll cycle in the tropical tree species Acacia crassicarpa. Tree Physiol. 2003, 23, 1255–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisek, J.; Sonnentag, O.; Richardson, A.D.; Mõttus, M. Is the spherical leaf inclination angle distribution a valid assumption for temperate and boreal broadleaf tree species? Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 169, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.R.; Nielsen, D.C.; Shock, C.C. Infrared thermometry and the crop water stress index. I. History, theory, and baselines. J. Prod. Agric. 1992, 5, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stull, R.B. Practical meteorology: an algebra-based survey of atmospheric science; University of British Columbia: Vancouver, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossiord, C.; Buckley, T.N.; Cernusak, L.A.; Novick, K.A.; Poulter, B.; Siegwolf, R.T.; Sperry, J.S.; Mcdowell, N.G. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Majeed, Y.; Naranjo, G.D.; Gambacorta, E.M. Assessment for crop water stress with infrared thermal imagery in precision agriculture: A review and future prospects for deep learning applications. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 182, 106019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).