1. Introduction

Definitions and descriptions in the well-being (WB) domain is evolving, the interdisciplinary nature and the way it integrates the different domains of human flourishing is well established. In this article well-being principles are applied within a system that integrates the different domains to provide a systemic illustration of how an improvement (or decrease) in one domain of well-being can lead to an improvement (or decrease) in other domains, and (ultimately) impact on overall well-being.

As an example, we show that, by using an integrated well-being framework, an individual’s options to improve (or decrease) her financial position extends well beyond the standard approach of financial planning.

In fact, the solution to improved financial outcomes over the individual lifespan could lie in a domain that has very little direct relationship with investment returns and/or other financial concepts. Rather it could lie in improving (or decreasing) other life domains, such as physical well-being. Not only will this increase (or decrease) financial well-being, but the combination of improved (or neglected) physical and financial well-being will result in a higher (or lower) level of integrated well-being.

2. Defining the Concepts

2.1. Integrated Well-Being (iWB)

Integrated well-being is a systems-based, multi-domain framework for understanding human flourishing, where biological health, psychological functioning, social connection, economic stability, environmental conditions, and personal meaning interact (non-linearly) to determine life outcomes [

1,

2,

3,

4]. It is often used in healthspan economics, organisational well-being programmes, and capability-based models such as Sen’s and Nussbaum’s approaches [

5,

6]. Integrated wellbeing emphasizes:

Multidimensionality: well-being spans many life domains;

Integration: the domains affect each other;

Sustainability over the life course: well-being is dynamic and adapts as circumstances and contexts change;

Agency and capability: it is the individual’s ability to act, adapt, and make choices that support flourishing

Contextual alignment: it is dependent on the goals, the environment, and available resources of both the individual and the society that they find themselves in.

Integrated well-being matters on a global and national level because an improvement in well-being can increase performance and productivity, leads to better employment outcomes, affects stronger social cohesion, and maintains sustainable growth [

4]. The opposite is also true. Decreases in any area of the well-being domain would decrease such on micro and macro levels. Another consideration is that there is also growing dissatisfaction with current measures of economic progress (such as the use of GDP growth) [

7].

On an individual level integrated well-being matters because it determines how long and well you live, how you work, earn, and adapt to changes over the lifespan [

4].

The literature on integrated wellbeing identifies several domains that are important for human flourishing. For example, the OECD publishes an annual measure of the wellbeing of a country’s citizens and has identified eleven dimensions that matters. This includes income and wealth, jobs and earnings, housing conditions, health status, work-life balance and education and skills [

4].

Edwards identifies ten personal, six local and seven national and global dimensions that contributes to a person’s well-being [

3]. The personal domains that Edwards identifies includes: employment and career, purpose and contribution, mental health, physical health, relationships and social connection, financial stability and education and growth. On a local scale Edwards identifies access to housing, transport, health and social care as some of the factors that matter, while environmental change, social norms and macroeconomic conditions are included as factors that matter on a national and global level.

Although the extent of the domains that has been identified varies depending on the level of investigation (e.g. global, national, local, individual) or the detail that the investigation requires, there are a few domains that surface in almost all the studies. These are: mental well-being; occupational well-being; financial well-being, physical well-being, social well-being and community well-being. In fact, Rath et al explore the common elements of well-being that transcend countries and cultures and concluded that these five domains are indeed statistically distinct factors that impact individual well-being [

8].

The integrated nature of the different domains of well-being suggests that:

an improvement in an individual’s total well-being will be limited if only one domain is developed perpetually and in isolation of the other domains. It implies that each domain is subject to diminishing marginal returns in relation to overall well-being. For example, while an improvement in physical well-being from a low level should initially contribute significantly to a lift in integrated well-being, it is unlikely to continue to increase integrated well-being if other domains, such as occupational well-being remains neglected. Kahneman et al shows this in the context of financial well-being by noting that an individual’s (subjective) well-being initially lifts along with their income [

9]. However, at a certain level the impact starts to taper off and their well-being becomes constrained by other domains.

the development of one domain has an impact of the other domains. Some domains may have a significant impact while others have a smaller impact, which may be dependent on the context the individual finds themselves in. For example, an improved level of physical well-being will have an impact on career well-being, while an improvement in career well-being has an impact on financial well-being.

This also suggests that there may be sacrifices (a “budget and/or resource constraint”) involved in one domain to develop and maintain sustained integrated well-being over the lifespan. An individual has only limited resources available that they gain from one domain to develop another domain, and it may be necessary to sacrifice gains in one domain in the short term to develop another domain.

2.2. Two Domains of iWB as Illustration

To illustrate how this system and its interdependencies can be utilised for integrated- as well as domain-specific optimisations - we narrow the scope of all the integrated well-being domains to only two domains:

While it is clearly an over-simplification of the complex reality of integrated well-being, this simplification allows us to illustrate:

how the interdependence between the factors of well-being should be considered when addressing single domains – in this case – financial and physical well-being;

how considering a holistic approach of well-being (integrated well-being) can also contribute to optimisation of the overall integrated well-being of the individual.

We start the illustration with a short description of each of these two domains within the context of the integrated well-being framework.

2.2.1. Financial Well-Being

While there are different definitions of financial well-being, it’s contribution to overall well-being is well established. According to Netemeyer et al, financial well-being explains “

substantial variation in well-being beyond other life domains that have been the focus of prior research (i.e. job satisfaction, relationship support satisfaction, and physical health” [

10]. In short, it is an integral part of well-being (integrated well-being).

Riitsalu et al notes that there are many terms used for financial well-being [

11]. These include financial wellness, financial health, financial satisfaction, financial comfort and financial resilience. Bruggen et al highlights that the existing definitions and measures can be clustered into three groups in terms of their approach: those that use objective and subjective characteristics, and those that use either objective or subjective measures of financial well-being [

12].

Examples of subjective definitions include a 2021 United Nations report where it states that “

Financial health – or wellbeing – is an emerging concept that addresses the financial side of individuals’ and families’ ability to thrive in society” [

13]. Similarly, Bruggen et al defines financial well-being as “

the perception of being able to sustain current and anticipated desired living standards and financial freedom” [

12]. Netemeyer et al describes financial well-being as the result of two distinct yet related assessments: “

How am I doing today” and “How do I expect I will be doing in the future?” [

10]

Definitions presented by Vosloo et al and Cox et al are examples of definitions that combine both objective and subjective aspects [

14], [

15]. Vosloo et al defines financial well-being as “

objective and subjective aspects that contribute to a person’s assessment of their current financial situation” while Cox et al defines financial well-being as “

a composite indicator made up of objective and subjective dimensions and concepts which describe individuals’ financial state and financial behaviours”. The Consumer Protection Bureau defines financial well-being as “

a state of being wherein a person can fully meet current and ongoing financial obligations, can feel secure in their financial future, and is able to make choices to enjoy life” [

16].

Objective measures of financial well-being include levels of debt, income or financial ratios such as debt to income levels. Examples of studies that include these measures are Greninger et al [

17].

Financial well-being also impacts other domains of integrated well-being. Bruggen et al highlights that financial well-being has a wide-ranging and consequential impact on enablement of individuals, organisations and societies [

12]. On an individual level, financial well-being impacts the quality of life, success, happiness, general well-being and mental health and relationship quality. Low financial well-being that leads to financial strain can have a negative impact on physical well-being. For example, Mercado et al shows that lower financial well-being is associated with unfavourable health behaviours and physical and mental health conditions [

18].

Apart from physical well-being, it also impacts career-well-being and social well-being. For example, at the organisational level, employees with low financial well-being tend to be more absent from work, have lower productivity and could impede their work and performance [

14,

19]. At a societal level Bruggen et al states that large groups of people that face financial problems reduce consumption and requires more social (welfare) support [

12].

2.2.2. Physical Well-Being

Despite ongoing work in different disciplines about how to define physical well-being, its importance for integrated well-being is unambiguous. Physical well-being is negatively correlated with mortality risk, and positively with physical functioning and independence, cognitive ability, and [

20,

21].

As with financial well-being, there are several definitions and descriptions of physical well-being. Pressman et al describes the different approaches at defining physical well-being [

22]. They suggest that physical health researchers tend to refer to physical well-being as the absence of disease, while other models of physical well-being views it through a continuum which anchors the one side of the continuum to disease, disability and death and the other side by optimal human functioning where “a person is maximally healthy, has resources for resisting disease and is capable of experiencing joy”.

The notion that physical well-being is a domain that goes beyond just objective measures of health, is supported by the description from the World Health Organisation which defined health in its constitution as “

a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [

23]. Diener et al defines physical well-being as “

the condition in which an individual experiences good physical health, sufficient energy and physical capability to engage fully in life activities and pursue valued goals.” [

24]. Rath et al defines physical well-being as having good health and enough energy to get things done daily [

8].

In short, an improvement (or decrease) in physical well-being not only increases (or decreases) a person’s lifespan, but it increases (or decreases) the potential of a person living a life free from (saddled with) activated/triggered chronic disease and fragility. Not surprisingly, it also affects an individual’s ability to build savings and earn income for a longer period [

25].

Physical well-being impacts the other domains of integrated well-being. For example. Pintor et al have done a review of the literature that investigates the relationship between an individual’s health and their associated labour market outcomes, stating “

The evidence reviewed suggested that individuals with better health overwhelmingly exhibit higher earnings and often enhanced labour supply” [

26]. The improvement in earnings is linked to higher productivity which leads to increased earnings per unit of labour supplied. The lift in productivity is associated with enhanced physical and mental capabilities that are associated improved physical well-being.

Higher earnings can also be associate with higher labour supply. That said, this mechanism depends on an individual’s preference between work and leisure. Improved physical well-being can result in an individual choosing to increase its labour supply, while the opposite can also be true. There does, however, seem to be consensus amongst researchers that poor health reduces labour supply [

27]. It is worth noting that a growing body of research suggest that working longer increases a person’s standard of living in retirement which can be another factor that contributes to an individual’s decision to provide more labour [

28].

While there seems sufficient evidence that suggests an individual’s ability (capability) to increase their labour supply improves with an improvement in physical well-being, this does not necessarily imply that they will indeed lift its supply. To illustrate the positive impact that an increase can have on an individual’s well-being we assume they does indeed decide to translate the capability to increase supply into an actual increase.

Another channel through which physical well-being can have an impact on an individual’s savings and earnings (financial well-being) is through the costs associated with a deterioration in physical well-being (as measured through health expenditure). For example, it can have a negative impact on savings if a deterioration results in increased medical expenses [

29].

Finally, for purposes of the development of our analytical model, it is important to distinguish between

healthspan and

lifespan when considering physical health as it has direct bearing on describing the period that a person can contribute productively in its working environment (healthspan) and the period that an individual lives (lifespan) [

30].

In the following section we use the defining background on integrated well-being, financial well-being, and physical well-being to express these as a dynamic interrelated system that should be optimised within an individual’s respective resource constraints.

3. Results

We first develop an analytical framework that can be used to optimise integrated well-being across several well-being domains. Once the framework is established, we illustratively narrow it down to the two domains of physical and financial well-being.

A Cobb-Douglas function is utilised to express the relationship between the different domains and the Integrated Well-being ), because of the following characteristics of IW:

complimentary nature of the different domains of integrated well-being;

positive elasticities associated with each domain of integrated well-being towards overall well-being;

diminishing marginal contribution of each single domain towards overall integrated well-being; and,

The resource constraint that restricts the extent that each domain can be developed during a certain period.

We combine this relationship with a dynamic function for the development of each domain and a function that represents the resource constraint(s). The

IW function for time (t) is expressed as:

where

is an index that represents integrated well-being of an individual at time (t): a value approaching zero represents very low level of integrated well-being and a value approaching 1 represents a very high level of integrated well-being.

represents a scaling factor that impacts integrated well-being apart from those already included in the model,

are indices that represents different levels of well-being of domain (i) at time (t) (i = 1 to n). A level approaching 0 represents a very low level of domain-specific well-being and a level approaching 1 represents a very high level of domain specific well-being.

3.1. Progression of Each Domain of Integrated Well-Being Within the Individual’s Resource Constraints

Each well-being domain requires a level of investment .

his consists of a minimum level of investment to maintain the current state of well-being and prevent deterioration (), while additional investment beyond this minimum improves the domain . is therefore the net progression of domain (i) in period (t).

However, the integrated nature of the different domains and their combined contribution towards overall well-being implies that there is a finite level of resources generated by the well-being domains that can be allocated across the domains through the investment functions. This serves as the individual’s resource constraint in period (t) ). The use of each domain for investment in the other domains will also generate a finite amount of well-being in the other domains.

The investment into each of the well-being domains are expressed as:

The function that generates resources for investment in well-being domain (i) in period (t) is a function of:

the available resources at the end of the previous period ; and,

the ability to create new resources based on the domains entering the integrated well-being function in period (t) and the use of resources that is employed in other domains to develop well-being domain k in the previous period and the use of resources in.

We constrain the individual to not be able to borrow resources apart from using its own accumulated resources.

Given equations 2 and 3, each domain’s evolution is positively related to an increase in net investment in the domain, which is positively correlated to the available resources for the investment in the domain:

We now use this system to maximise expected Integrated Well-Being subject to the individual’s level of resources available to develop the different domains.

3.2. Optimising Integrated Well-Being in a Two-Domain Model That Includes Financial and Physical Well-Being

We can now adopt the system described in section 3 into a two-factor model that includes financial and physical well-being as drivers of integrated well-being. This illustrates the broader principle that consideration of all the well-being domains can provide additional optionality when focusing on a domain-specific outcome.

And, in this specific example, how the consideration of integrated well-being when optimising financial well-being can contribute to a more optimal financial well-being outcome, while also leading to a better physical and integrated well-being outcome and vice-versa – an improvement in financial well-being can contribute to an improvement in physical well-being. The system below describes the dynamics for each of these well-being domains within the integrated well-being framework.

3.2.1. The Integrated Well-Being Function

Making the simplifying assumptions that the only domains entering the Integrated Well-Being function is financial- and physical well-being, we can express the Integrated Well-Being function of an individual at time (t) as:

Where

:

represent the elasticity of financial well-being and physical well-being respectively.

is financial well-being in time t

is physical well-being in time t,

where

a value of 0 represents very poor financial and/or physical well-being ; and

1 represents an exceptional level of financial and/or physical well-being.

For purposes of the measurement of financial and physical well-being we distinguish between an objective and a subjective component. The objective components are measured through objective indicators of financial and physical health, while the subjective components represent the individual’s perception of their level of financial and physical well-being. The level of financial and physical well-being functions are expressed as:

We focus on the objective measurement of the financial and physical well-being domain for the rest of the framework where a value that approaches 1 is a value that represents a level of financial resources (measured in monetary value) that allows the individual to be in a state of being wherein they can fully meet current and ongoing financial obligations, can feel secure in their financial future, and is able to make choices to enjoy life. The index that measures financial well-being is therefore representative of an individual’s life-time budget constraint.

3.2.2. The Progression of Physical Well-Being

The individual’s physical well-being in time t develops as a function of their previous level of physical well-being , investment into developing physical well-being in the current period ) and their financial well-being (). Physical well-being does, however, deteriorate over time which requires a minimum investment of other well-being domains to ensure a certain level of physical well-being is maintained.

Given the deteriorating nature of physical well-being, and per the framework described in

Section 3, the individual must invest a minimum amount of resources to maintain the current level of physical well-being (

and increase the current level of well-being (

).

where

is a logistics function that allows

to increase over time, representing the decay rate of physical well-being through time.

In both cases, the resources will be a function of the previous period’s resources available for investment in well-being domains

, the resources generated in the current period (

and the investment in other domains of well-being (

– financial well-being in our two-factor model.

Where

Where

:

Finally, we also distinguish between two periods in the individual’s lifetime:

The individual’s healthspan and lifespan is positively related to physical well-being, but the impact of physical well-being is larger on healthspan than on lifespan.

Both healthspan and lifespan ends when physical well-being falls under certain exogenously defined levels for the specific individual.

3.3.3. The Progression of Financial Well-Being

The individual’s objective financial well-being in time (t) develops through investment into objective financial well-being in time (t). There will be a minimum level of investment required to maintain the same level of objective financial well-being as at the previous period (

) and additional investment to lift objective financial well-being above the previous period’s level (

). Both these investment components require resources for progression in objective financial well-being. The investment function is expressed as:

The resources available for investment in objective financial well-being is generated through a process that is:

a function of their previous level of objective financial well-being and the financial market return that can be achieved on that level of objective financial well-being (r);

their level of physical well-being in period (t) (); and

resources that are expended on the development of the physical well-being in the current period (t) ).

The objective financial resource generation function is expressed as:

Equation 12’s components can be further decomposed. The first term expresses the resources generated in period (t) as the financial market earnings on accumulated objective well-being and the second term the net income that the individual receives through its labour supply minus its investment in physical well being (

):

Because we distinguish between healthspan and lifespan in the progression of physical well-being, the labour-income generating function is expressed as:

Hence, equation 13 becomes:

Which creates the explicit constraint that an individual can earn labour income during its healthspan and only financial income thereafter.

Over the individual’s lifespan equation 13 represents the individual’s lifetime budget:

subject to

Where equation 17 can be discounted to its present value through the discount factor (i) which represents the individual’s time preference.

We can now use this system to deduct a few insights related to optimising financial well-being through an integrated well-being perspective.

4. Integration

Optimising Financial Well-Being Through an Integrated Well-Being Perspective

This system of integrated well-being allows us to show how one can employ the integrated nature of the different well-being domains to optimise a specific domain, while also optimising overall well-being. In this instance we show it by focusing on financial well-being and its relationship with physical well-being. We offer three deductions on this basis.

Deduction 1: There is a positive relationship between financial well-being and physical well-being for a given level of expected financial return

This is illustrated through taking the first order derivative of equation 17 with respect to physical well-being

while keeping targeted investment in physical well-being and the rate of return on accumulated financial well-being constant.

For an individual that uses its increased capability to earn labour income, an improvement in physical well-being in period (k) increases income in period (k), which impacts financial well-being (in period k positively). Because the change in income in period (k) compounds over time (as expressed in Equation 17) it results in higher objective financial well-being (all other factors remaining constant) and hence overall financial well-being according to equation 5.

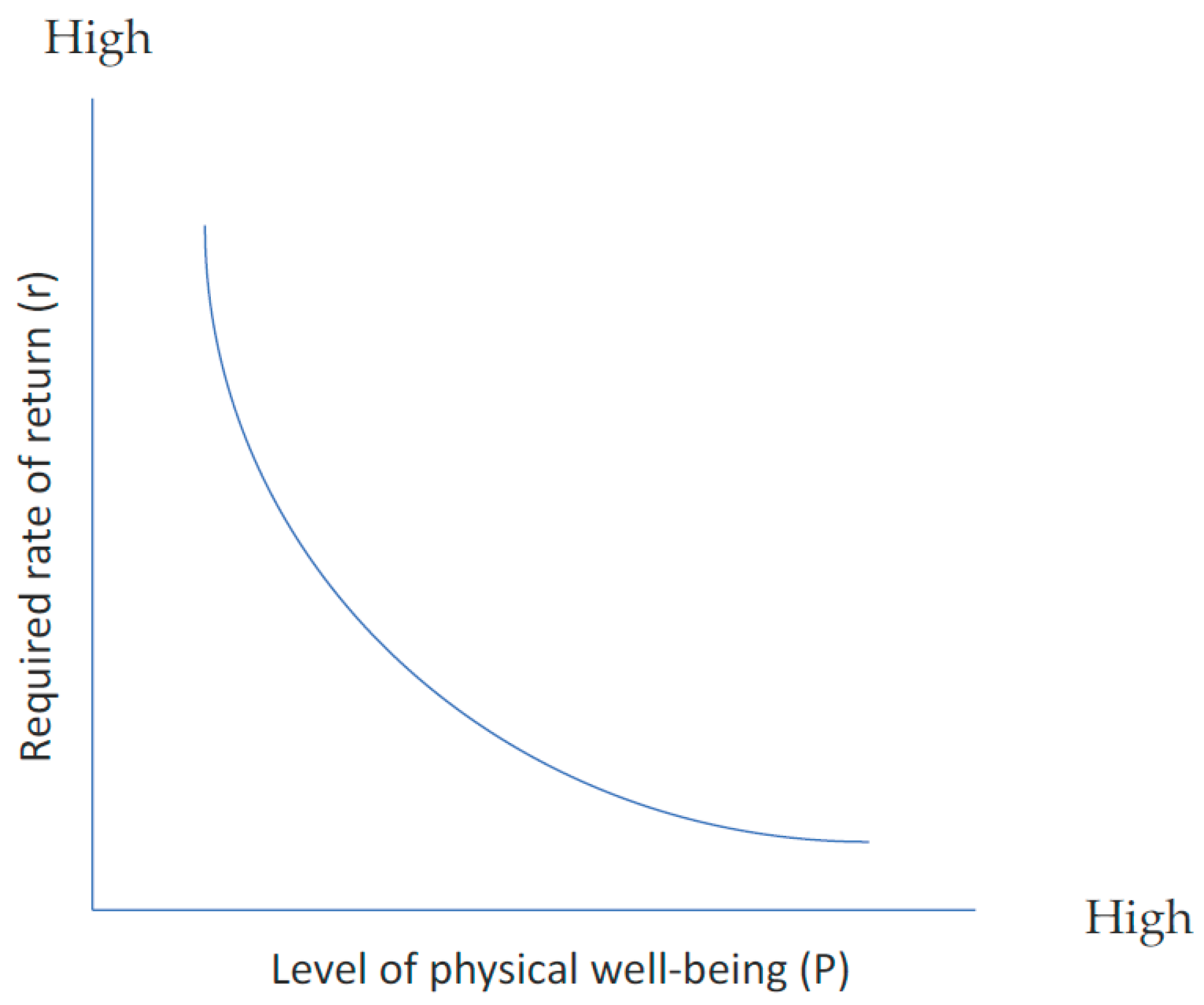

Deduction 2: An individual that translates their increased capability to earn labour income through enhanced physical well-being can reduce the required return that should be achieved for a set level of objective lifetime financial well-being.

This is illustrated through re-arranging Equation 17 and expressing it as the expected return on financial well-being (r) with respect to income and physical well-being.

Re-arranging Equation 15 for r results in:

Solving for the first differential of r relative to Y yields:

Where

represents income in period k. This outcome presents the obvious outcome that an improvement in income in period k will result in a decrease in required returns on wealth over the lifespan for a given level of targeted investment in physical well-being and level of objective well-being (

and (

. Solving equation 16 for the first differential relative to physical well-being (

results in:

This shows that an improvement in physical well-being will result in a decrease in the rate of return required on a

target level of objective financial well-being and targeted level of investment in physical well-being. The second derivative of this relationship is, however, negative (

), suggesting a diminishing marginal impact of health on required return. These relationships can be shown through the graph below:

Figure 1.

The relationship between the required rate of return (r) on financial well-being and the level of physical well-being (P).

Figure 1.

The relationship between the required rate of return (r) on financial well-being and the level of physical well-being (P).

Our last deduction is that Integrated well-being lifts along with improved physical health that leads to improved financial well-being (and vice versa).

Deduction 3: An improvement in physical well-being that leads to an improvement in financial well-being, leads to an improvement in integrated well-being.

Integrated well-being in our two-factor model is expressed through the Cobb-Douglas function (

). The first order derivative with respect to both physical and financial well-being is positive:

suggesting that an increase in both financial- and/or physical well-being will result in an improvement in integrated well-being.

5. Discussion

It is our understanding that the growing body of research that focuses on human well-being shows that there is significant dynamic contextualised interaction between the different domains that are important for well-being. This interaction creates a complex system of feedback loops that must be considered when investigating individual domains of well-being as well as well-being in its totality. The integrated nature of well-being also presents opportunities to optimise one domain of well-being by focusing on the development of a different domain. Lastly, the consideration of optimising well-being over both the short-term and the long-term over the lifespan requires further contextualised balancing of resources across the domains and across the lifespan (time).

To illustrate the integrated nature of the different domains of well-being we express it as a Cobb-Douglas function along with functions that relate to the investment in each domain and an individual’s resource constraints. This resource constraint can also be seen as an individual’s willingness and ability to sacrifice well-being in different domains to increase another and to optimise integrated well-being over the lifespan.

We then use this system to show how the interaction between financial- and physical well-being can lead to different considerations when optimising an individual’s financial well-being. This optimisation shows that, while an individual could be focusing financial-specific factors to lift their financial well-being – such as searching for investment opportunities that offers higher returns on financial well-being, they could rather consider investing in physical well-being. Our model shows that, by improving physical well-being, an individual could improve their financial well-being without having to increase its expected returns on financial well-being. This is in line with recent concepts tabled by other research [

31]

More importantly, by focusing only on factors that impact financial well-being directly (such as the rate of return on financial well-being), the marginal contribution of the increase in financial well-being will eventually diminish. While, focusing on a different domain of integrated well-being – in this case physical well-being – will increase integrated well-being without running into diminishing marginal returns because physical well-being is lifting at the same time.

This approach towards addressing financial well-being is quite different from the standard approach of financial advice which tends to focus on a narrow set of financial instruments and objectives but ignores the other domains of human (integrated) well-being.

This model should be expanded to include more domains. For example, including the career well-being domain and showing how an increase in this domain could create another pathway towards optimising financial well-being and/or physical well-being at the intersect of integrated well-being.

The model should also be adjusted for the stochastic nature of well-being. The progression of the individual domains of integrated well-being is uncertainty and subject to exogenous shocks. This uncertainty should be incorporated in an expansion of the model.

It will also be a natural progression to find a way to estimate the elasticities and other quantifiable factors in the model.

As the study of integrated wellbeing expands and clarity of the different domains, their contribution to, and their interaction with, each other surfaces, the model should be adjusted and refined to reflect this improved behavioural knowledge. However, it should also be used to analyse individual domains and what the effect of sacrifices in the different domains are over the short- and long-term of the lifespan (time).

Author Contributions

TJDW and TDW were involved in the conceptualisation of the article content. TDW conceptualised the broad framework, while TJDW designed and formulated the equations. Both authors drafted the work and substantively revised it. Both authors have approved the submitted version and agree to be personally accountable for their individual and collective contributions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT 5.0 for the purposes of supporting the solving some of the equations and checking consistency of the flow of the equations. Google Gemini 3 Flash (Default) was also utilised to support with the base Abstract and Highlights. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IW |

Integrated Well-being |

| WB |

Well-being |

References

- Dodge, R.; Daly, A.; Huyton, J.; Sanders, L. ‘The challenge of defining wellbeing’. Int. J. Wellbeing. [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F. ‘Psychological well-being: Evidence regarding its causes and consequences’. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2009, vol. 1(no. 2), 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, R.T. ‘Well-being and well-becoming through the life-course in public health economics research and policy: A new infographic’. Front. Public Health 2022, vol. 10, 1035260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. How’s life? Measuring well-being; OECD Publishing, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as freedom; Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. Creating capabilities; Harvard University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, P.J.E.; Sen, P.A.; Fitoussi, P.J.-P. ‘Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress’.

- Rath, T.; Harter, J. Wellbeing: The five essential elements; Gallup Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, D.; Deaton, A. ‘High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being’. PNAS. [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R. ‘How am I doing? Perceived financial well-being’. J. Consum. Res. [CrossRef]

- Riitsalu, L.; Sulg, R.; Lindal, H.; Remmik, M.; Vain, K. ‘From Security to Freedom— The Meaning of Financial Well-being Changes with Age’. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2024, vol. 45(no. 1), 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggen, E.; Hogreve, J.; Holmlund, M.; Kabadayi, S.; Löfgren, M. ‘Financial well-being: A conceptualization and research agenda’. J. Bus. Res. vol. 79, 228–237. [CrossRef]

- ‘UNSGSA Financial-health-introduction-for-policymakers’.

- Vosloo, W.; Fouche, J.; Barnard, J. ‘The Relationship Between Financial Efficacy, Satisfaction With Remuneration And Personal Financial Well-Being’. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. IBER 2014, vol. 13(no. 6), 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Hooker, H.; Marwick, R. ‘Financial well-being in the workplace’; Institute for Employment Studies.

- Bureau, C.F.P. ‘Financial well-being: The goal of financial education’. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Greninger, S.A.; Hampton, V.L.; Kitt, K.A.; Achacoso, J.A. ‘Ratios and Benchmarks for Measuring the Financial Well-Being of Families and Individuals’. Financ. Serv. Rev. 1996, vol. 5(no. 1), 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado, C. ‘Exploring associations of financial well-being with health behaviours and physical and mental health: a cross-sectional study among US adults’. BMJ Public Health 2024, vol. 2(no. 1), e000720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Garman, E.T. ‘Financial stress and absenteeism: An empirically derived model’. J. Financ. Couns. Plan. 2003, vol. 14(no. 1). [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Pinilla, F.; Hillman, C. ‘The Influence of Exercise on Cognitive Abilities’. In Comprehensive Physiology, 1st ed; Prakash, Y. S., Ed.; Wiley, 2013; pp. 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemadi, M.; Kamyar, S.; Hassan, N.A.; Zakaria, Z. ‘A review of the importance of physical fitness to company performance and productivity’. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2016, vol. 13(no. 11), 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S.; Kraft, T.; Bowlin, S. ‘Well-being: Physical, psychological, social’. In Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine; Springer, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

Constitution of the World Health Organization; World Health Organization, 1948.

- Diener, E.; Scollon, C.; Lucas, R. ‘The evolving concept of subjective well-being’. Soc. Indic. Res. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. ‘Productive longevity’. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pintor, M.P.; Fumagalli, E.; Suhrcke, M. ‘The impact of health on labour market outcomes: A rapid systematic review’. Health Policy 2024, vol. 143, 105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L. ‘The Effects of Health on the Extensive and Intensive Margins of Labour Supply’. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2021, vol. 184(no. 1), 87–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronsthein, G.; Scott, J.; Slavov, S. ‘The power of working longer’. National Bureau of Economic Research. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. ‘Healthy bodies and thick wallets’. J. Econ. Perspect. [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, E. ‘Lifespan and healthspan: Past, present, and promise’. Front. Public Health. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, N. ‘Integrating Healthspan and Wealth Span: A Conceptual Framework for Financial Longevity’. Prog. Med. Sci. 2025, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).