1. Introduction

Throughout life, individuals face adversities that influence their health and overall functioning. In this context, resilience—understood as the ability to cope with and adapt to adverse situations—is essential (Hephsebha & Deb, 2024). This concept is closely linked to well-being, self-efficacy, and social support, and has gained particular relevance in the financial sphere. Financial resilience has attracted attention both in academic circles and among regulators, as it contributes to economic stability and enables individuals and systems to absorb and adapt to shocks and uncertainty (Cornaro, 2022). Strengthening financial resilience is crucial to prevent systemic crises and ensure the effective functioning of the financial system (Alam et al., 2024).

Despite its recognized importance, financial resilience still lacks a clear and unified conceptualization (Salignac et al., 2021). It is commonly defined as an organization’s ability to remain operational and recover effectively after a crisis, taking into account the costs and impacts of the event (Daadmehr, 2024). To achieve this, companies must strategically coordinate their resources and design adaptive strategies that enhance performance and reduce risk (Chowdhury et al., 2024).

According to Sreenivasan and Suresh (2023), financial resilience involves anticipating, preparing for, and adjusting to both gradual transformations and unexpected crises. Its main objective is to ensure survival and growth through effective economic strategies. On an individual level, it refers to the ability to manage financial hardship by effectively utilizing personal resources (Hamid et al., 2023). The absence of this capability often leads to greater reliance on government support systems. Oyadeyi et al. (2024) distinguish between financial resilience and economic vulnerability, emphasizing that strengthening the former reduces the latter. Financial resilience, therefore, plays a key role in socioeconomic recovery and sustainable development, relying on effective policy implementation and strong financial foundations.

In urban contexts, Gong (2023) identifies five key dimensions of economic resilience—openness, income and expenditure, innovation, development, and diversity—which influence the stability of cities. In the face of natural disasters, countries develop strategies to mitigate macroeconomic impacts and facilitate recovery (Ciullo et al., 2023). In today’s business environment, organizational resilience depends not only on pre-crisis human capital but also on the ongoing support companies provide to their employees during adverse events.

Employee resilience is crucial, as their adaptive capacity reinforces the overall resilience of the organization, facilitating its recovery (Prayag & Dassanayake, 2022). Furthermore, strengthening corporate financial resilience requires analyzing costs, profit margins, and preparing crisis scenarios (Sreenivasan & Suresh, 2023). In the workplace, individual resilience positively impacts employee engagement, performance, and mental well-being. Resilient individuals tend to have higher self-esteem, better health, and greater productivity (Ibrahim & Hussein, 2024). However, certain population groups—such as female-headed households, older adults, or individuals with low educational attainment—face greater challenges in recovering from economic crises (Salignac et al., 2021). In such contexts, access to financial protections, such as insurance or support networks, plays a key role in enhancing family economic resilience (Oppong et al., 2024).

At both individual and macroeconomic levels, financial resilience has been widely studied. In Malaysia, financial inclusion and education have been found to strengthen this resilience (Hamid, Lok, & Chin, 2023). In China, factors such as social capital, assets, and financial literacy have a positive impact on adolescents and their families (Liu & Chen, 2023, 2024). In rural areas, digital financial inclusion helps households manage risks and overcome structural limitations (Hu et al., 2024). At the corporate level, ownership structure and strong governance reduce financial risk (Alam et al., 2024). Gong (2023) demonstrates how effective financial policies and sound healthcare management facilitated recovery in Chinese provinces after the pandemic. Similarly, in Ghana, microinsurance has proven to be an effective tool for low-income households (Oppong, Yu, & Mazonga, 2024). At the international level, risk diversification in sovereign wealth funds is key to addressing natural disasters (Ciullo et al., 2023).

Recent studies reinforce a multidimensional view of financial resilience. Ben, Clark, Ftiti, and Prigent (2024), as well as Landini (2024), contribute advanced methodologies for managing systemic risks. However, some findings offer a more nuanced perspective. For instance, in Bangladesh, foreign ownership may increase financial risk due to political and familial interference (Alam et al., 2024). In India, Yadav and Shaikh (2023) observe that access to credit and digital transactions support financial resilience, although merely holding multiple bank accounts does not necessarily have the same effect. Mundi and Vashisht (2023) emphasize that cognitive skills influence the resilience of millennial single parents, with variations based on gender and educational level. From a psychological perspective, Özyeşil, Tembelo, and Çikrikçi (2024) find that financial resilience mediates the relationship between financial well-being, future anxiety, and mental health, especially among healthcare professionals. On the other hand, Glew et al. (2023) argue that industrial resilience must be understood in conjunction with legal and political dimensions, highlighting the need for a multidisciplinary and holistic approach.

In summary, financial resilience is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, whose effectiveness depends on structural, educational, technological, cultural, and institutional factors. While there is broad consensus on its importance, approaches must be tailored to specific contexts in order to achieve sustainable and equitable recovery.

This leads us to ask the following questions: How do workers perceive financial health indicators? Likewise, what experiences have they had in relation to these indicators? In addition, what actions have they taken to cope with adverse situations linked to financial health? Therefore, the main purpose of this study is to evaluate financial health indicators based on workers’ perceptions, lived experiences, and actions taken in response to adverse circumstances. The goal is to identify and validate the model that best fits, according to the theoretical criteria of absolute fit, structural fit, and parsimony.

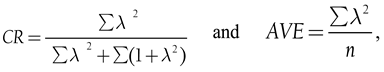

Figure 1 show the conceptual model.

Operational Meaning of the Variables in the Conceptual Model

X1: Spend less than you earn (maintain a balanced budget where expenses do not exceed income). X2: Pay bills on time and in full (avoid late payments to maintain a good credit reputation and prevent additional fees). X3: Have savings in financial products (keep liquid funds in savings accounts or accessible financial instruments). X4: Own long-term savings or assets (possess investments or savings that provide future financial security, such as real estate or retirement funds). X5: Sustainable debt level (maintain manageable debt that does not compromise financial stability). X6: Sustainable credit history (have a good credit record that facilitates access to financing under favorable conditions). X7: Have adequate insurance (possess policies that protect against unexpected economic risks (health, home, life insurance). X8: Plan Expenses (Create budgets and spending plans to avoid unexpected costs and maintain financial control).

Financial Health Indicators (FHI): Financial Health Perception (FHP): How individuals perceive their own financial health in terms of security, control, and stability. Financial Health Experiences (FHE): Real-life accounts and situations that reflect how they have managed their financial health over time. Actions to Face Financial Crises (AFFC): Strategies and measures adopted to overcome economic difficulties, such as reducing expenses, refinancing, or seeking additional income.

2. Methodology

This study follows a non-experimental, quantitative, and cross-sectional design, aiming to examine how perceptions, lived experiences, and financial actions relate to financial well-being indicators among workers at a sugar mill. Participants and Sample: The target population includes individuals over the age of 18 employed at a sugar production company located in San Juan Bautista Tuxtepec, Oaxaca, Mexico. The company currently has approximately 600 unionized workers and 200 non-union staff members. The sample was obtained through non-probability self-selection sampling, in which employees voluntarily chose to participate, indicating their informed consent to take part in the study. Data was collected using an online questionnaire distributed via Google Forms, with the aim of maximizing valid responses during this initial phase. While non-probability sampling limits the generalizability of the findings to the broader workforce, it is considered methodologically appropriate for the exploratory nature of this research. The study seeks to identify and understand the relationship between financial resilience and personal experiences—complex and inherently subjective dimensions that require a flexible and inclusive approach to capture diverse individual realities.

An initial cohort of 311 valid participants was collected during the first phase of the study, forming the basis for preliminary analyses and enabling future comparative assessments. Since the goal is not to generalize findings to the broader population but rather to explore latent patterns and validate theoretical dimensions related to financial resilience, the use of non-probability sampling is both appropriate and relevant. Additionally, the questionnaire remains open, allowing for ongoing and dynamic data collection. This strategy encourages greater response diversity and enhances the ecological and contextual validity of the findings by incorporating perspectives over time. In doing so, the study broadens its scope and deepens the understanding of how different life experiences influence financial resilience in specific work environments.

Ethical Considerations. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Business School at Universidad Cristóbal Colón (Project ID: P-04/2025) and adheres to the Research Ethics Code of the Graduate Studies and Research Division at the National Technological Institute of Mexico. It was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were informed about the study’s objectives and procedures, and full confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed. Informed consent was obtained from all participants after they read and agreed to the provided information. Instrument. The instrument used in this study was previously employed by García-Santillán et al. (2024), and is based on frameworks developed by BBVA (2020) and the Center for Financial Services Innovation (CFSI), complemented by 16 items developed by Flores, Zamora-Lobato, and García-Santillán (2024). The instrument is designed to assess perceptions, lived experiences, and strategies used to face financial crises.

Statistical Analysis and Reliability/Validity Assessment. To validate the instrument and analyze the collected data, several statistical indicators were employed to assess internal consistency and the measurement model's validity. Internal reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha (α), McDonald’s omega (ω), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). Both α and ω measure internal consistency, with ω offering greater robustness when factor loadings vary across items (McDonald, 1999; Tavakol & Dennick, 2011). Composite reliability (CR) is considered acceptable with values above 0.70 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), indicating reliable latent constructs. AVE was used to assess convergent validity, with values above 0.50 considered acceptable, meaning that the items adequately explain the variance of the corresponding construct (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). These metrics help ensure that the measurement scales are both statistically reliable and valid for the study’s objectives. Multivariate normality was also tested. According to Kim (2013), data can be considered normally distributed if skewness falls between -2 and 2 and kurtosis between -7 and 7. Values outside these ranges may indicate significant deviations such as skew or leptokurtosis, which could affect the analysis. George and Mallery (2010) recommend evaluating both indicators together, while Field (2013) emphasizes the importance of assessing normality before applying parametric tests. In this study, Fisher’s criteria were used to assess skewness and kurtosis (Spiegel, Schiller & Srinivasan, 2009).

3. Data analysis and Discussion

The reliability and internal consistency of the test and dataset yielded a Cronbach's alpha of 0.936 and a McDonald's omega of 0.935, both of which are considered excellent. These values indicate that the instrument demonstrates high internal consistency, suggesting that the items coherently measure the same underlying construct. Additionally, the correlation matrices and variable-level measures of sampling adequacy show satisfactory values. The determinant is close to zero, indicating acceptable multicollinearity, and the MSA (Measure of Sampling Adequacy) values exceed the theoretical threshold of 0.5, supporting the suitability of the data for factor analysis.

Table 1.

Correlations matrix and MSA.

Table 1.

Correlations matrix and MSA.

| |

|

FIP1 |

FIP2 |

FIP3 |

FIP4 |

FIP5 |

FIP6 |

FIP7 |

FIP8 |

MSA |

| FIP1 |

Correlación de Pearson |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.836a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FIP2 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.493**

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.891a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FIP3 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.413**

|

.475**

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

.860a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FIP4 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.279**

|

.406**

|

.614**

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

.876a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| FIP5 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.262**

|

.249**

|

.297**

|

.415**

|

1 |

|

|

|

.872a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

| FIP6 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.295**

|

.414**

|

.328**

|

.429**

|

.368**

|

1 |

|

|

.899a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

| FIP7 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.296**

|

.452**

|

.367**

|

.395**

|

.262**

|

.599**

|

1 |

|

.866a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

| FIP8 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.318**

|

.411**

|

.227**

|

.318**

|

.217**

|

.437**

|

.619**

|

1 |

.885a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

**. The correlation is significant at the 0,01 level (two-tailed).

*. The correlation is significant at the 0,05 level (two-tailed).

a determinant = 7.960E7 |

| |

|

LEFI1 |

LEFI2 |

LEFI3 |

LEFI4 |

LEFI5 |

LEFI6 |

LEFI7 |

LEFI8 |

MSA |

| LEFI1 |

Correlación de Pearson |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.942a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LEFI2 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.504**

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.960a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LEFI3 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.494**

|

.479**

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

.902a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LEFI4 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.468**

|

.436**

|

.731**

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

.911a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| LEFI5 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.452**

|

.459**

|

.548**

|

.651**

|

1 |

|

|

|

.930a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

| LEFI6 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.400**

|

.494**

|

.434**

|

.511**

|

.644**

|

1 |

|

|

.931a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

| LEFI7 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.355**

|

.449**

|

.473**

|

.574**

|

.611**

|

.677**

|

1 |

|

.942a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

| LEFI8 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.449**

|

.429**

|

.442**

|

.518**

|

.594**

|

.646**

|

.652**

|

1 |

.937a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

7.5E-17 |

2.3E-15 |

2.6E-16 |

1.0E-22 |

4.9E-31 |

3.7E-38 |

5.2E-39 |

|

**. The correlation is significant at the 0,01 level (two-tailed).

*. The correlation is significant at the 0,05 level (two-tailed).

a determinant = 7.960E7 |

| |

|

FR1 |

FR2 |

FR3 |

FR4 |

FR5 |

FR6 |

FR7 |

FR8 |

MSA |

| FR1 |

Correlación de Pearson |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.941a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FR2 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.572**

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

.951a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FR3 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.559**

|

.577**

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

.941a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FR4 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.546**

|

.456**

|

.623**

|

1 |

|

|

|

|

.936a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| FR5 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.559**

|

.455**

|

.550**

|

.680**

|

1 |

|

|

|

.940a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

|

| FR6 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.468**

|

.514**

|

.565**

|

.569**

|

.594**

|

1 |

|

|

.948a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

|

| FR7 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.479**

|

.415**

|

.591**

|

.592**

|

.684**

|

.657**

|

1 |

|

.931a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

|

| FR8 |

Correlación de Pearson |

.437**

|

.423**

|

.446**

|

.565**

|

.573**

|

.646**

|

.601**

|

1 |

.934a |

| Sig. (bilateral) |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

.000 |

|

**. The correlation is significant at the 0,01 level (two-tailed).

*. The correlation is significant at the 0,05 level (two-tailed).

a determinant = 7.960E7 |

Prior to conducting the factor analysis, data suitability was assessed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The KMO value exceeded 0.90 (0.922), indicating excellent sampling adequacy (Kaiser, 1974). Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant, with a Chi-square value of 4229.498, 276 degrees of freedom (p < .001), suggesting that the correlations among variables were sufficiently strong to justify factor analysis (Hair et al., 2019). Once data adequacy was confirmed through the KMO index and Bartlett’s test, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted. Given the assumption of correlation among latent factors and in line with previous studies (Flores et al., 2024), an oblique Promax rotation was applied following the method of Hendrickson and White (1964). This technique begins with an initial orthogonal solution (such as Varimax) and adjusts it to allow for correlations between factors, which is particularly appropriate in fields like psychology, where constructs are rarely independent.

Moreover, Promax rotation facilitates a simpler and more interpretable factor structure by encouraging each item to load primarily onto a single factor and is also computationally efficient.

Table 2 presents the cumulative variance explained by the five extracted factors, and

Table 3 displays the rotated factor loading matrix.

As shown in

Table 2, the factor analysis extracted five factors that together explain 65.48% of the total variance in the data. This indicates that these five factors effectively represent the information contained in the analyzed items, summarizing all the variability observed in the responses. In other words, most of the differences among participants across the various questions can be explained by these five underlying constructs, confirming that the identified factor structure is robust and accurately represents the latent aspects measured by the questionnaire. As shown in

Table 3, the factor loading matrix rotated using the Promax method revealed a structure composed of five clearly distinct factors. Each item showed a significant loading (≥ 0.50) on a single factor, suggesting appropriate grouping of the items and a well-defined factorial structure. This rotation demonstrated that the extracted factors represent coherent and theoretically interpretable dimensions of the construct under study. Furthermore, since an oblique rotation was applied, correlations among factors were allowed, which is appropriate given the psychological nature of the instrument, where some interrelation between underlying dimensions is expected. Together, these results support the structural validity of the instrument and justify retaining five factors.

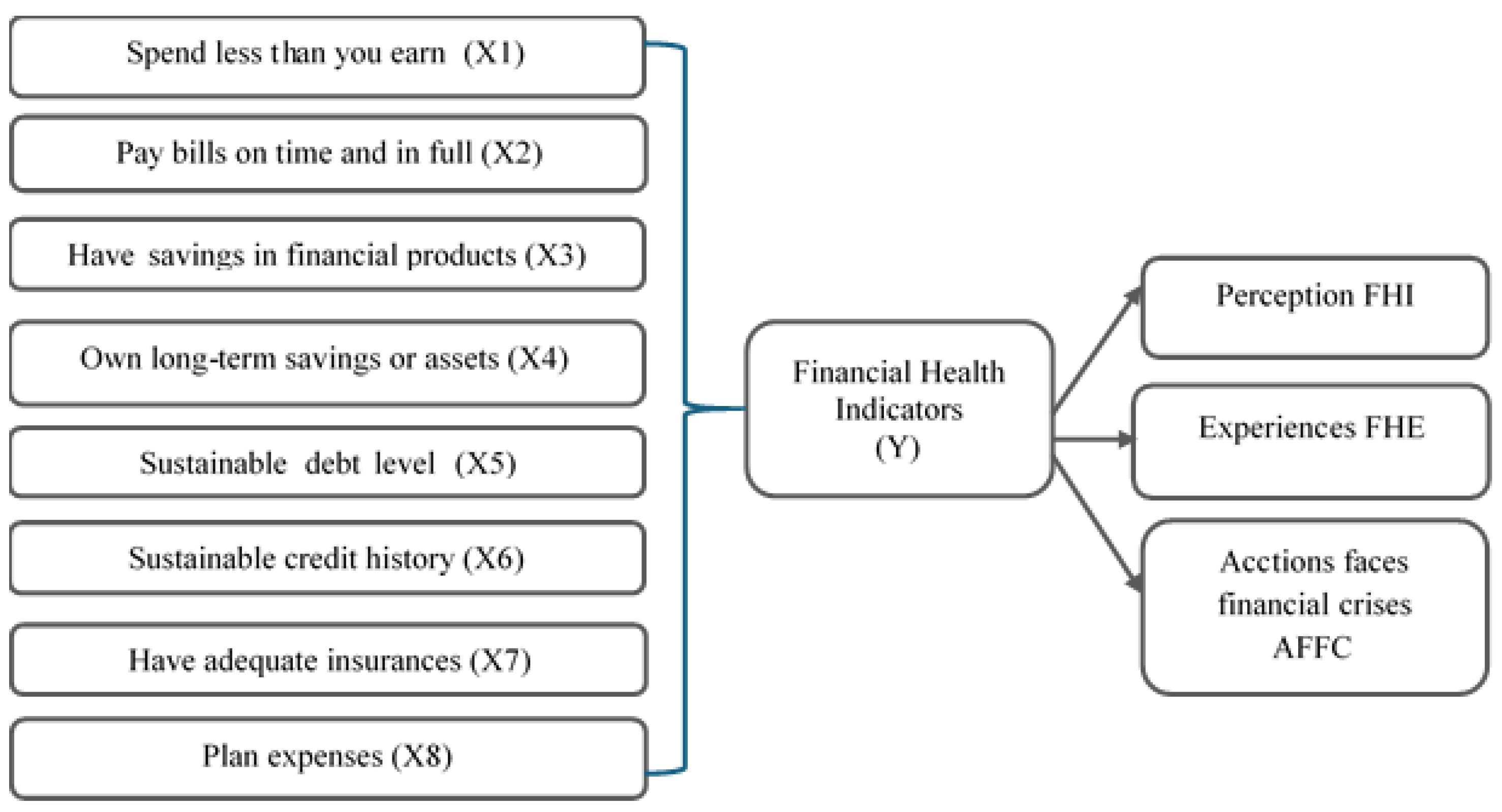

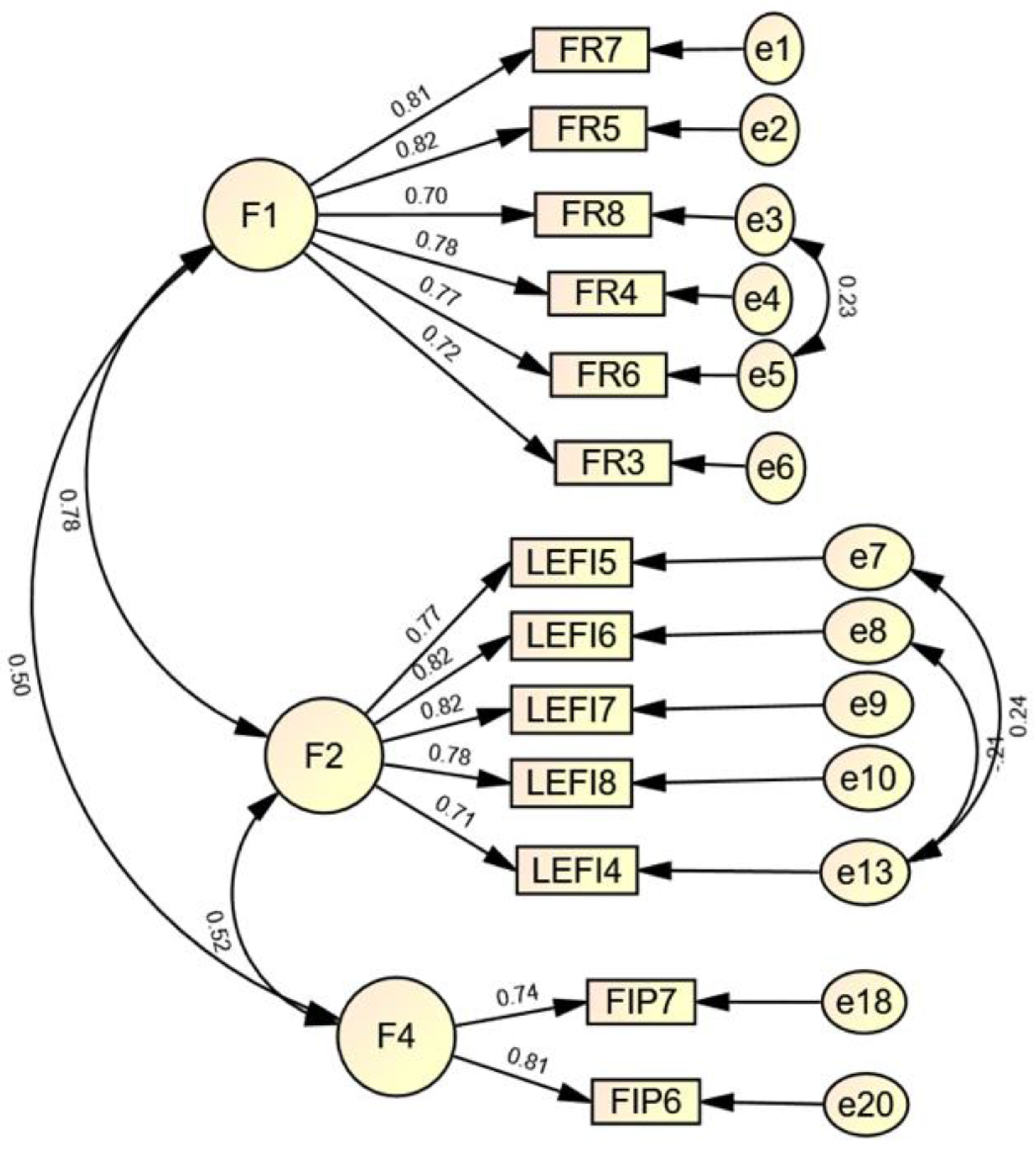

To calculate composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE), the following parameters are used according to the formulas:

where: λ: Standardized factor loadings, n: number of ítems per factor;

Based on the CR and AVE results, the theoretical criteria suggest that Factors 1 and 2 are adequate. For Factor 3, it is recommended to remove either FIP3 (0.593) or LEFI1 (0.600) to improve the AVE. Factor 4 is acceptable, although it only has three items; therefore, adding at least one more item would be advisable to enhance the values. Factor 5, with only two items, is not recommended as it does not meet the minimum psychometric requirements. It would be advisable to merge it with another factor if theoretically justified or, alternatively, to remove it from the model. As a future recommendation, developing additional items for this factor would be beneficial.

Confirmatory Analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the model fit of the previously proposed structure. This analysis aims to evaluate three key aspects of model fit: absolute fit, structural fit, and model parsimony. The model to be confirmed is based on the rotated structure presented in

Table 3, which suggested a preliminary factorial configuration derived from the exploratory factor analysis. Based on that structure, a theoretical model was developed and is now being validated using confirmatory techniques, applying commonly accepted fit indices in the literature (such as GFI, AGFI, RMSEA, CFI, TLI, among others).

This procedure will determine the extent to which the empirical data support the proposed factor structure and will serve as the basis for accepting, adjusting, or refining the initial theoretical model.

Figure 2 presents the initial model.

The results of the confirmatory factor analysis indicate that the global fit indices—GFI (.838), AGFI (.795), RMSEA (.085), CFI (.877), and TLI (.857)—do not reach the thresholds typically considered acceptable in the specialized literature. This suggests that the initial measurement model, derived from the rotated structure, does not adequately fit the observed data. Therefore, it is necessary to introduce adjustments and refinements to the proposed model. As a result, modifications were made by excluding estimators with values below 0.70 and by reassigning certain indicators to the factor with which they better align conceptually and statistically

The following figures show the adjustments in the factors FA, FAt, FB, FWB and FC, which are made for the validation of the confirmatory model.

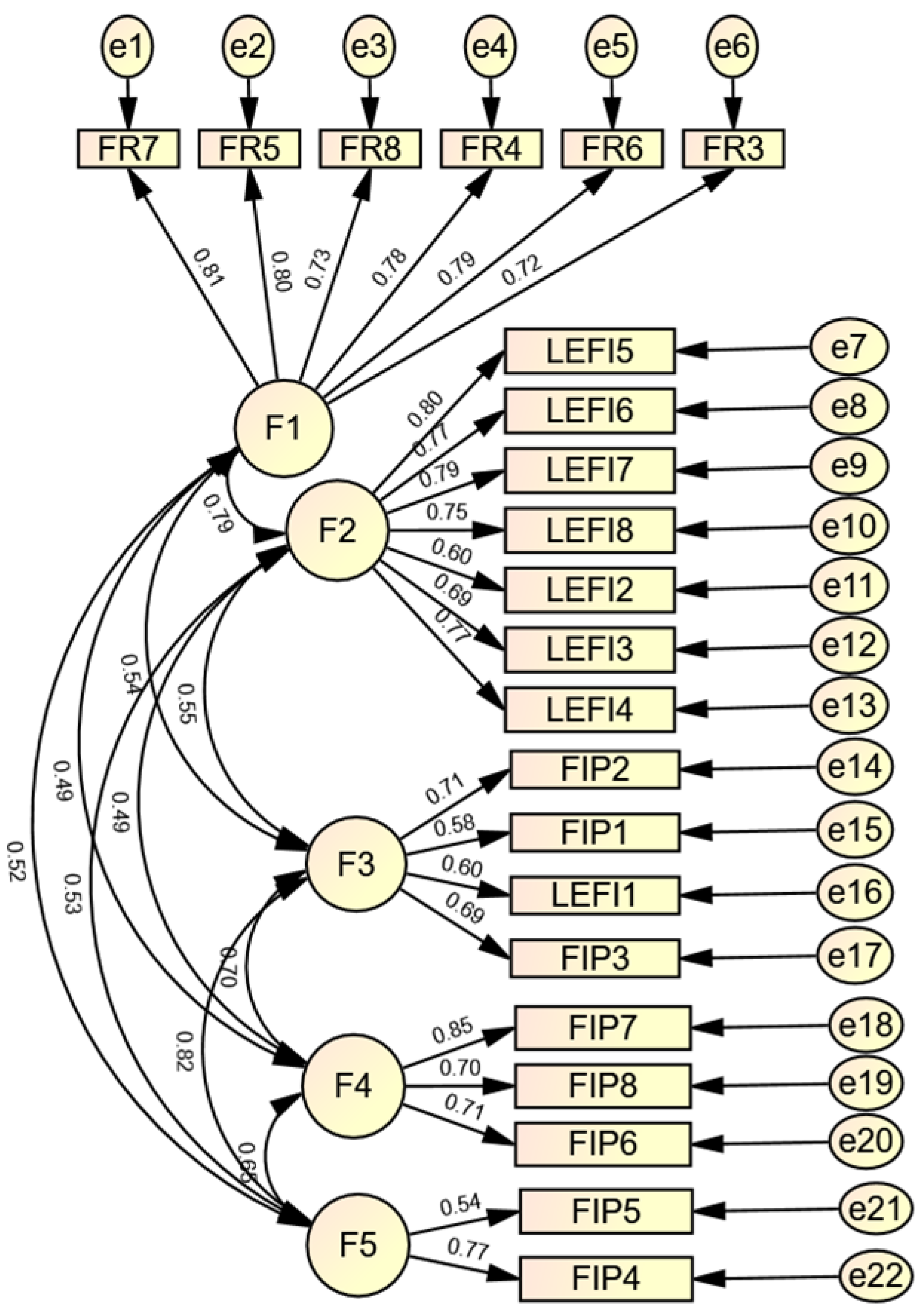

Figure 3 displays the final adjusted model.

As shown in

Figure 3, the resulting three-factor model reveals the following insights: Participants emphasized that financial resilience is key to facing economic challenges. In this context, they mentioned that when adequate insurance is lacking, it is essential to establish a plan that allows them to adjust their financial approach and protect their assets in the face of unexpected situations. They also highlighted the importance of managing debt sustainably, with a clear strategy that enables them to meet their obligations without compromising financial stability. Several participants noted that planning expenses—both short- and medium-term—is crucial to avoid financial surprises that could lead to stress. In addition, they expressed the need to maintain sufficient savings or long-term assets to serve as a financial safety net. Regarding those without a strong credit history, participants pointed out the importance of taking steps to improve it, as a good credit profile facilitates access to financing in critical moments. Finally, participants indicated that increasing savings in liquid financial products is an essential strategy for ensuring quick access to funds when unforeseen events arise.

About their lived experiences, participants shared that their financial well-being is reflected in how they have managed their finances over time and the decisions they have made. Many emphasized that maintaining a manageable level of debt is essential, as it allows them to meet their obligations without negatively affecting other areas of their lives. Regarding credit history, several participants agreed that having a good credit record not only provides access to credit under better conditions but also reflects responsible financial management. Additionally, participants stressed the importance of having adequate insurance coverage, as it provides a safety net in the face of unexpected events. They also mentioned that planning short-term expenses is key to avoiding financial stress and making more informed decisions. Lastly, they highlighted that having long-term savings or assets gives them peace of mind about the future and allows them to handle unforeseen situations with greater confidence.

When it comes to how they perceive these indicators of financial health, participants agreed that factors such as having appropriate insurance and a solid credit history are essential to their financial stability. They expressed that these elements are not only critical for their financial security but also reflect their ability to make smart decisions that protect them and offer peace of mind. In summary, participants stated that adopting a comprehensive approach to their finances—one that includes both financial planning and an awareness of their overall situation—enables them to face adversity with confidence and build a strong foundation for the future. Statistically, the final model presented in Figure 3 reflects the best absolute, structural, and parsimonious fit, according to the theoretical criteria suggested. The following section explains in detail the different fit measures considered:

Absolute Fit Indices: The relative Chi-Square statistic (χ²/d.f.) was 1.888, falling within the acceptable range (between 2 and 5), indicating that the model fits the data well. The RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) value was 0.054, below the critical threshold of 0.08, which also suggests a good fit. The GFI (Goodness-of-Fit Index) reached 0.951, exceeding the recommended minimum of 0.90, supporting the model’s overall fit quality. The AGFI (Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit Index) was 0.924, above the 0.80 threshold, reaffirming adequate model fit. Finally, the SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual) was 0.038, an acceptable value given the sample size (reference: ≤ 0.08). Incremental Fit Indices: Regarding the NFI (Normed Fit Index), the value was 0.953, surpassing the minimum threshold of 0.90, indicating a satisfactory fit. The CFI (Comparative Fit Index) was 0.977, also above the recommended level of 0.90, demonstrating excellent model fit. Similarly, the TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index) yielded a value of 0.970, also exceeding the 0.90 threshold, further confirming the quality of the incremental fit. Parsimony Fit Indices: The PGFI (Parsimonious Goodness-of-Fit Index) reported a value of 0.616, above the generally accepted minimum of 0.50, suggesting reasonable model fit in terms of parsimony. The PNFI (Parsimonious Normed Fit Index) reached 0.721, also surpassing the required minimum of 0.50, indicating adequate fit. Finally, the PCFI (Parsimonious Comparative Fit Index) showed a value of 0.739, also exceeding the established threshold, reflecting an acceptable fit consistent with parsimony criteria.

4. Theoretical Discussion

Financial resilience, understood as the ability to adapt to and overcome economic crises, has been widely discussed in the literature. The results of this study largely align with theoretical approaches that emphasize the importance of financial planning, debt management, and protection against unforeseen events as key strategies for strengthening economic resilience at both individual and organizational levels. In this regard, participants highlighted the importance of having adequate insurance, long-term savings, and a clear debt management strategy—elements that are consistent with recommendations from previous studies.

According to Sreenivasan and Suresh (2023), financial resilience involves anticipating and preparing for both gradual changes and unexpected crises. This is reflected in the practices reported by participants, who noted that planning short- and medium-term expenses is crucial for avoiding financial surprises and maintaining economic stability. A key finding of this study was the importance of maintaining a good credit history, which also aligns with the work of various authors such as Oyadeyi et al. (2024), who argue that access to credit, when combined with proper resource management, enhances financial resilience. However, this study specifically highlights that improving one's credit profile is viewed by participants as fundamental—particularly during times of crisis—adding a practical dimension to existing theories on financial resilience. In turn, the ability to manage debt sustainably reinforces the assertions of Alam et al. (2024), who emphasize the importance of strategic resource management to avoid economic vulnerability.

Another important theme that emerged—closely aligned with theoretical frameworks—is the focus on long-term financial security. Participants agreed that having savings and assets is essential for dealing with economic crises in a more resilient manner. This resonates with the work of Sreenivasan and Suresh (2023), who underscore that financial resilience is not only about managing immediate resources but also about the ability of individuals or institutions to remain stable over time. The broader literature on economic resilience (e.g., Gong, 2023) also highlights the importance of having a financial buffer to cope with unexpected situations, which is evident in participants’ responses that valued the existence of long-term assets.

Regarding the emotional well-being associated with financial resilience, the study results open a new line of reflection. Participants expressed that having a solid credit history and appropriate insurance coverage not only provides economic stability but also contributes to peace of mind. This well-being dimension, though not yet deeply explored in the financial resilience literature, appears to play a crucial role in how people perceive their financial security. Studies such as that of Özyeşil et al. (2024) suggest that financial resilience is linked to mental health, particularly in professional contexts, supporting the notion that financial stability has a significant impact on emotional and psychological well-being. On the other hand, while theoretical foundations emphasize recovery and adaptability in the face of economic crises, the findings of this study place additional emphasis on prevention. The dominant literature, such as that of Sreenivasan and Suresh (2023), tends to focus on how organizations and individuals can bounce back from crises. However, in this study, participants stressed that a preventive approach—such as expense planning and debt management—helps them face adversity with greater confidence and less stress. This suggests that while financial resilience certainly involves the capacity for recovery, anticipatory preparation is also crucial for mitigating the impact of economic shocks.

Finally, a unique aspect of this study is the strong sense of autonomy that participants associate with financial resilience. Throughout the interviews, it was evident that making informed decisions about debt, savings, and insurance not only provided economic stability but also gave them a sense of personal control over their financial well-being. This perception of autonomy is linked to self-efficacy, which, according to Hephsebha and Deb (2024), is fundamental to the development of resilience. The ability to make responsible financial decisions contributes to a sense of empowerment, further strengthening individuals' capacity to face future adversity.

5. Theoretical Implication

The findings of this study have several significant theoretical implications in the field of financial resilience. First, they broaden the understanding of resilience not only as the ability to recover from economic crises but also as a proactive process. Existing literature, such as Sreenivasan and Suresh (2023), has tended to focus on resilience from a reactive perspective. In contrast, this study highlights the importance of prevention through financial planning, debt management, and building long-term financial buffers. This proactive approach offers a more comprehensive and dynamic view of financial resilience, suggesting that preventive interventions can be as valuable as recovery strategies. Furthermore, the results emphasize the emotional and psychological dimension of financial resilience, which has often been underrepresented in prior research. The fact that participants perceive peace of mind as a direct outcome of sound financial management introduces a new component into financial resilience studies. This aspect could be incorporated into future theoretical models that acknowledge resilience not only as an economic phenomenon but also as a process affecting overall individual well-being.

Finally, this study provides evidence that complements existing theory on the relationship between self-efficacy and financial resilience. According to Hephsebha and Deb (2024), self-efficacy—defined as the belief in one’s ability to handle challenging situations—is essential for strengthening resilience. Participants in this study demonstrated that making informed financial decisions gives them a sense of control and empowerment, potentially opening new avenues for research on how self-efficacy influences economic resilience.

6. Practical Implications

From a practical perspective, the findings of this study have important applications for public policy, financial education, and the design of intervention programs. Firstly, proactive financial planning emerges as a crucial component for enhancing individuals' financial resilience, suggesting that financial education programs should place greater emphasis on teaching prevention skills rather than solely focusing on crisis management. Covering topics such as sustainable debt management, long-term savings planning, and the importance of having adequate insurance can equip individuals with tools to reduce financial stress and improve their economic stability.

In the business realm, organizations can use the findings of this study to develop organizational resilience strategies that focus not only on recovery capacity after a crisis but also on the prevention of financial risks. This might include creating adaptive financial plans that involve employees in economic planning and decision-making, thereby strengthening organizational financial resilience.

Moreover, integrating mental health considerations into financial resilience strategies could prove valuable. The results suggest that individuals who perceive their financial well-being as solid experience greater peace of mind and reduced anxiety, which can be critical for designing interventions aimed not only at improving economic stability but also overall well-being. Therefore, public policies that promote financial education, access to insurance, and responsible credit use could play a key role in enhancing financial resilience at both individual and collective levels.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that financial resilience is a multifaceted concept that encompasses not only the ability to adapt to economic crises but also proactive preparation and strategic resource management. The research highlighted the importance of factors such as expense planning, sustainable debt management, insurance protection, and long-term savings as key elements contributing to greater financial stability. Additionally, participants emphasized the relationship between financial resilience and emotional well-being, suggesting that proper financial management not only promotes economic stability but also greater peace of mind.

The study also showed that self-efficacy, understood as the belief in one’s ability to make responsible financial decisions, is fundamental to strengthening economic resilience. This finding opens new theoretical perspectives on how the perception of personal control can influence financial resilience, an area that has been less explored in existing literature.

8. Future Research Directions

This study proposes several future research avenues that could contribute to a deeper understanding of financial resilience. First, it would be interesting to explore how different sociocultural factors, such as educational level, gender, or family situation, influence the financial resilience strategies adopted by individuals. This approach could help identify personalized interventions that address the specific needs of different population groups.

Another promising line of research concerns the relationship between financial resilience and psychological well-being. While better financial management has been shown to reduce stress, further research is needed to understand how mental health and emotional well-being are influenced by economic resilience, especially in contexts of prolonged crises or high uncertainty.

Finally, it would be valuable to investigate how financial resilience strategies are applied at organizational and macroeconomic levels, particularly in the context of vulnerable or developing economies. Studying how public policies and government strategies can enhance the economic resilience of specific sectors could help design more effective interventions aimed at reducing the financial vulnerability of entire communities.

References

- (Alam, Das, Dipa, Hossain 2024). Alam, S., Das, S. K., Dipa, U. R., & Hossain, S. Z. (2024). Predicting financial distress through ownership pattern: dynamics of financial resilience of Bangladesh. Future Business Journal, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- (Ben, Clark, Ftiti, et al. 2024). Ben Ameur, H., Clark, E., Ftiti, Z. et al., (2024). Operational research insights on risk, resilience & dynamics of financial & economic systems. Ann Oper Res 334, 1–6 (2024). [CrossRef]

- (Chowdhury, Chowdhury, Quaddus, Rahman, Shahriar 2024). Chowdhury, M. M. H., Chowdhury, P., Quaddus, M., Rahman, K. W., & Shahriar, S. (2024). Flexibility in Enhancing Supply Chain Resilience: Developing a Resilience Capability Portfolio in the Event of Severe Disruption. Global Journal Of Flexible Systems Management, 25(2), 395-417. [CrossRef]

- (Ciullo, Strobl, Meiler, et al. 2023). Ciullo, A., Strobl, E., Meiler, S. et al., (2023). Increasing countries’ financial resilience through global catastrophe risk pooling. Nat Commun 14, 922 (2023). [CrossRef]

- (Ciullo, Strobl, Meiler, Martius, Bresch, 2023). Ciullo, A., Strobl, E., Meiler, S., Martius, O., & Bresch, D. N. (2023). Increasing countries’ financial resilience through global catastrophe risk pooling. Nature Communications, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- (Cornaro 2022). Cornaro, A. (2022). Financial resilience of insurance network during Covid-19 pandemic. Quality & Quantity, 57(S2), 151-172. [CrossRef]

- (Daadmehr 2024). Daadmehr, E. (2024). Workplace sustainability or financial resilience? Composite-financial resilience index. Risk Management, 26(2). [CrossRef]

- (Flores, Zamora-Lobato, García-Santillán 2024). Flores, M., Zamora-Lobato, T. & García-Santillán, A. (2024). Three-dimensional model of financial resilience in workers: Structural equation modeling and bayesian analysis. Economics and Sociology, 17(1), 69-88. [CrossRef]

- (Fornell, Larcker 1981). Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [CrossRef]

- (García-Santillán, Escalera-Chávez, Santana 2024). García-Santillán, A., Escalera-Chávez, M. E., & Santana, J. C. (2024). Exploring resilience: a Bayesian study of psychological and financial factors across gender. Cogent Economics & Finance, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- (George, Mallery 2010). George, D., & Mallery, P. (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference (10th ed.). Pearson.

- (Glew, Von Behr, Dreesbeimdiek, Houiellebecq, Schumacher, Rama Murthy, Kumar 2023). Glew, R., von Behr, C.-M., Dreesbeimdiek, K., Houiellebecq, E., Schumacher, R., Rama Murthy, S. and Kumar, M. (2023). "The financial, legal and political foundations of industrial resilience", Continuity & Resilience Review, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 17-35. [CrossRef]

- (Gong 2023). Gong, Y. (2023). The impact of China’s financial policy on economic resilience during the pandemic period. Economic Change And Restructuring, 56(4), 2493-2509. [CrossRef]

- (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, 2019). Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- (Hamid, Loke, Chin 2023). Hamid, F. S., Loke, Y. J., & Chin, P. N. (2023). Determinants of financial resilience: insights from an emerging economy. Journal Of Social And Economic Development, 25(2), 479-499. [CrossRef]

- (Hendrickson, White 1964). Hendrickson, A. E., & White, P. O. (1964). Promax: A quick method for rotation to oblique simple structure. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 17, 65–70. [CrossRef]

- (Hephsebha, Deb 2024). Hephsebha, J., & Deb, A. (2024). Introducing Resilience Outcome Expectations: New Avenues for Resilience Research and Practice. International Journal Of Applied Positive Psychology, 9(2), 993-1005. [CrossRef]

- (Hu, Sheng, Ni, et al. 2024). Hu, L., Sheng, D., Ni, G. et al. (2024). Digital Financial Inclusion and Poverty-Alleviation Resilience of Chinese Rural Households. J Fam Econ Iss (2024). [CrossRef]

- (Ibrahim, Hussein 2024). Ibrahim, B. A., & Hussein, S. M. (2024). Relationship between resilience at work, work engagement and job satisfaction among engineers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- (Kaiser 1974). Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. [CrossRef]

- (Kim 2013). Kim HY. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013 Feb; 38(1): 52-4. [CrossRef]

- (Landini 2024). Landini, S. (2024). Financial Resilience Issues in Agriculture. In: Heidemann, M. (eds) The Transformation of Private Law – Principles of Contract and Tort as European and International Law. LCF Studies in Commercial and Financial Law, vol 2. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- (Liu, Chen 2024). Liu, Z., Chen, JK. (2024). Financial Resilience and Adolescent Development: Exploring a Construct of Family Socioeconomic Determinants and Its Associated Psychological and School Outcomes. Child Ind Res 17, 2283–2318 (2024). [CrossRef]

- (Liu, Chen, 2023). Liu, Z., Chen, JK., (2023). Financial Resilience in China: Conceptual Framework, Risk and Protective Factors, and Empirical Evidence. J Fam Econ Iss (2023). [CrossRef]

- (McDonald 1999). McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- (Mundi,Vashisht 2023). Mundi, H.S. and Vashisht, S. (2023). "Cognitive abilities and financial resilience: evidence from an emerging market", International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 41 No. 5, pp. 1010-1036. [CrossRef]

- (Oppong, Yu, Mfoutou 2024). Oppong, E. O., Yu, B., & Mfoutou, B. o. M. (2024). The effect of microinsurance on the financial resilience of low-income households in Ghana: evidence from a propensity score matching analysis. The Geneva Papers On Risk And Insurance Issues And Practice, 49(3), 474-500. [CrossRef]

- (Oyadeyi, Ibukun, Arogundade, Oyadeyi, Biyase 2024). Oyadeyi, O. O., Ibukun, C. O., Arogundade, S., Oyadeyi, O. A., & Biyase, M. (2024). Unveiling economic resilience: exploring the impact of financial vulnerabilities on economic volatility through the economic vulnerability index. Discover Sustainability, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- (Özyeşil, Tembelo, Çikrikçi 2024). Özyeşil, M., Tembelo, H., Çikrikçi, M. (2024). The Mediating Role of Resilience in the Relationship Between Financial Well-Being and Future Financial Situation Expectations, Psychological Well-Being, and Future Anxiety. In: Hamdan, A., Braendle, U. (eds) Harnessing AI, Machine Learning, and IoT for Intelligent Business. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, vol 550. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- (Prayag, Dassanayake 2022). Prayag, G., & Dassanayake, D. M. C. (2022). Tourism employee resilience, organizational resilience and financial performance: the role of creative self-efficacy. Journal Of Sustainable Tourism, 31(10), 2312-2336. [CrossRef]

- (Salignac, Hanoteau, Ramia 2021). Salignac, F., Hanoteau, J., & Ramia, I. (2021). Financial Resilience: A Way Forward Towards Economic Development in Developing Countries. Social Indicators Research, 160(1), 1-33. [CrossRef]

- (Spiegel, Schiller, Srinivasan 2009). Spiegel, M. R., Schiller, J., & Srinivasan, R. A. (2009). Estadística (4ª ed.). McGraw-Hill. (García-Santillám, Escalera-Chávez, & Santana 2024). García-Santillán, A., Escalera-Chávez, M. E., & Santana, J. C. (2024). Exploring resilience: a Bayesian study of psychological and financial factors across gender. Cogent Economics & Finance, 12(1). [CrossRef]

- (Tavakol, Dennick 2011). Tavakol, M., & Dennick, R. (2011). Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. International Journal of Medical Education, 2, 53–55. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).