1. Introduction

Financial literacy is essential for economic well-being, as it enables individuals to make informed decisions about their personal finances. According to Lusardi and Mitchell (2014), a deficiency in financial education can lead to suboptimal decisions in areas such as savings, investment, and debt management, which directly affects financial security. In this regard, access to financial education is crucial for improving financial management skills and promoting greater economic stability (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011). Financial decisions related to asset accumulation and debt management require numerical skills, often involving complex calculations. However, individuals' mathematical capabilities are often limited, particularly when it comes to financial decision-making. Lusardi (2012) highlights that studies conducted in the United States and other countries show that many individuals possess low numerical skills, with this deficiency being more pronounced among certain demographic groups, such as women, older adults, and those with lower levels of education.

The lack of numerical skills has both individual and societal implications, as the ability to make informed financial decisions is closely linked to numeracy

1 or numerical literacy. Lusardi (2012) emphasizes that, in the current economic environment, both numeracy and financial education are essential for success in an increasingly complex financial context. Financial education is not limited to theoretical knowledge but also includes the ability to apply this knowledge in everyday situations (Mandell, 2006). Students who master financial knowledge and the skills necessary for decision-making are better prepared to manage their money, save, and invest effectively (James et al., 2012). A study by Lusardi (2019) highlights the importance of financial knowledge in individuals' ability to make sound financial decisions. Therefore, improving university students' ability to make informed financial decisions is crucial for optimizing their financial education. Students with higher levels of financial knowledge are more likely to take calculated risks in their financial endeavors, such as investing in the stock market or starting a business (Sobaih & Elshaer, 2023). In contrast, those with lower financial knowledge tend to be more risk-averse and prefer safer options (Seraj et al., 2022). Understanding how financial education influences risk tolerance is crucial for educators and policymakers to tailor educational programs to the specific needs of university students (Ergün, 2018). Additionally, financial education is key not only for daily decision-making but also for long-term planning, such as retirement (Lusardi, 2019). Aside from financial education, financial counseling is another important tool for improving economic decision-making. According to Agarwal and Chua (2020), individuals who receive financial advice tend to make more informed and efficient decisions regarding savings and investments.

However, access to and the effectiveness of financial counseling are deeply influenced by individuals' level of financial literacy. A higher level of financial knowledge enables individuals to better understand the recommendations from advisors and make more decisions that are informed. Lusardi and Mitchell (2011) assert that financial literacy is crucial for individuals to fully benefit from financial advisory services, particularly in areas such as retirement planning. Research shows that individuals with higher financial knowledge are more likely to seek external assistance and, furthermore, achieve better financial outcomes due to their ability to effectively evaluate and apply the advice received. In this regard, improving financial education can be key to strengthening the positive effects of financial counseling and optimizing long-term outcomes. Attitudes toward money also play a crucial role in economic decisions. According to Furnham (1984), beliefs and attitudes toward money deeply influence financial behaviors, such as the tendency to save or to spend impulsively. These attitudes develop throughout life and are influenced by socioeconomic and cultural factors. Individuals with a positive attitude toward saving tend to be more disciplined in managing their resources (Perry & Morris, 2005). Along with financial knowledge, these attitudes are essential in forming healthy financial habits.

Gender differences influence financial behavior. Research indicates that men and women manage their finances differently. According to Joo and Grable (2004), women tend to be more conservative in their investment decisions and have less confidence in their financial knowledge. These factors can impact their ability to accumulate wealth. Financial education that addresses these differences is crucial for improving the financial skills of both genders (Lusardi, Mitchell, & Curto, 2010). Furthermore, a deficiency in financial education can lead to suboptimal decisions in saving, investing, and debt management, which in turn affects financial security (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014). Access to financial education is essential for improving financial management and fostering economic stability (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011). Decisions related to asset accumulation and debt management require numerical skills, which are often limited, particularly among women, older adults, and those with lower levels of education (Lusardi, 2012). Understanding how financial education influences risk tolerance is critical for tailoring educational programs to the specific needs of university students (Ergün, 2018).

The lack of numerical skills has both individual and societal implications, as the ability to make informed financial decisions depends on numeracy. Lusardi emphasizes that in the current economic environment, both numeracy and financial education are essential for success in a complex financial context. Financial education not only includes theoretical knowledge but also the ability to apply it in everyday situations (Mandell, 2006). Students who master these skills are better prepared to manage their money, save, and invest effectively (James et al., 2012). According to Lusardi (2019), financial knowledge is key to making sound decisions. Improving university students' ability to make informed financial decisions is crucial for optimizing their financial education. Students with higher financial knowledge tend to take calculated risks, such as investing in the stock market or starting a business (Sobaih & Elshaer, 2023), while those with less knowledge tend to be more risk-averse (Seraj et al., 2022). Additionally, financial education is essential not only for daily decisions but also for long-term planning, such as retirement (Lusardi, 2019).

In addition to financial education, financial counseling is another important tool for improving economic decision-making. According to Agarwal et al. (2009), individuals who receive financial advice are more likely to make informed and efficient decisions regarding savings and investment. However, access to and the effectiveness of such advice are deeply influenced by the individual's level of financial education. A higher level of financial knowledge enables individuals to better understand the recommendations from advisors and make decisions that are more informed. Individuals with greater financial knowledge are more likely to seek external assistance and, furthermore, achieve better financial outcomes due to their ability to effectively assess and apply the advice they receive. In this regard, improving financial education can be key to strengthening the positive effects of financial counseling and optimizing long-term outcomes. Lusardi and Mitchell (2011) argue that financial literacy is crucial for individuals to fully benefit from financial advisory services, particularly in areas such as retirement planning.

On the other hand, it is important to highlight that attitudes toward money also play a crucial role in economic decisions. According to Furnham (1984), beliefs and attitudes toward money deeply influence financial behaviors, such as the tendency to save or to spend impulsively. These attitudes develop throughout life and are influenced by socioeconomic and cultural factors. Individuals with a positive attitude toward saving tend to be more disciplined in managing their resources (Perry & Morris, 2005). Along with financial knowledge, these attitudes are essential in forming healthy financial habits. Gender differences also affect financial behavior. Research has shown that there are differences in the ways men and women manage their finances. According to Joo and Grable (2004), women, on average, tend to be more conservative in their investment decisions and have less confidence in their financial knowledge compared to men. These factors can influence how women make financial decisions and, consequently, their ability to accumulate wealth over time. Financial education aimed at addressing these differences can be crucial for improving the financial capabilities of both genders (Lusardi, Mitchell, & Curto, 2010).

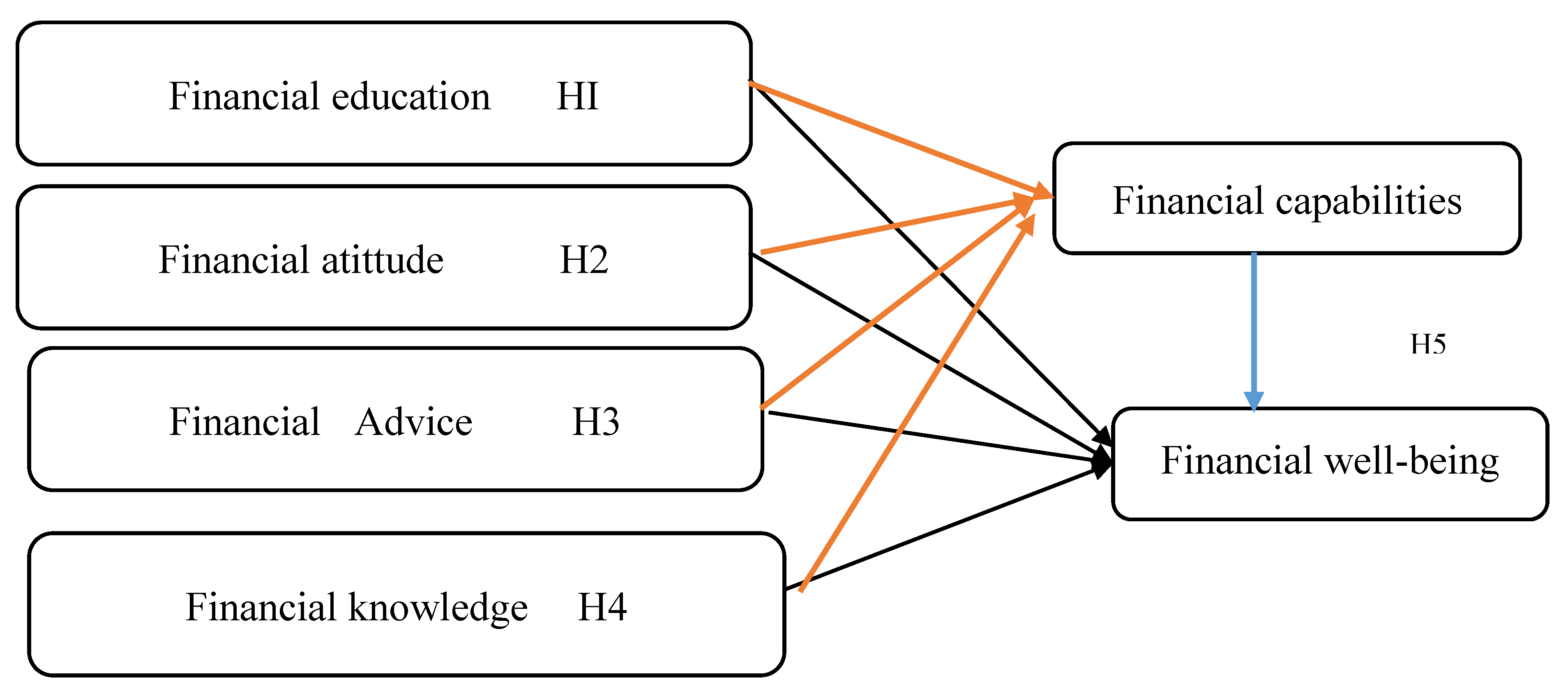

Therefore, the study aims to: 1) Assess the relationship between individuals' level of financial education and their ability to manage personal finances. 2) Analyze the influence of attitudes toward money management, saving, and investing on individuals' financial capabilities. 3) Evaluate the impact of financial advice received on individuals' financial capabilities. 4) Determine whether financial knowledge contributes to enhancing financial capabilities. 5) Analyze the influence of financial capabilities on financial well-being. Lastly, 6) Evaluate gender differences in relation to financial education, financial advice, financial attitudes, financial knowledge, financial capabilities, and financial well-being, in order to identify potential gender-based differences in these aspects. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1. Financial education level influence significantly in financial capabilities

H2. Financial attitude influence in financial capabilities

H3. Financial advice influence significantly in financial capabilities

H4. Financial knowledge influence significantly in financial capabilities

H5. Financial capabilities influence significantly in the financial well-being

3. Financial Education

In the current theoretical discussion on financial education, various approaches and empirical findings are being analyzed, highlighting its impact on financial literacy and other economic aspects. It has been found that public authorities in several countries implement educational policies through the certification of educational institutions offering financial education courses. While this certification process is useful, it is influenced by political and bureaucratic incentives that may bias its effectiveness. In this regard, it has been suggested that financial education is a "credibility good," whose impact largely depends on trust in the educational providers. Furthermore, concerns about financial instability may be a key motivation for political activism surrounding financial education (Guerini, Masciandaro, & Papini, 2024). Levels of financial education promote financial inclusion, which has a direct impact on employment. Financial inclusion improves employment levels, with educational development acting as a moderator of this effect. This impact is more pronounced in female groups and in low- and middle-income countries, suggesting that financial inclusion has greater benefits in less privileged contexts. It is interesting to observe how digital empowerment, combined with financial inclusion policies, can significantly contribute to improving job opportunities (Song, Li, & Wu, 2024).

An alternative approach discusses the design of pension systems and how individualized financial education provided by the government can optimize economic decision-making. Studies indicate that, under conditions of perfect information regarding perceptual biases, the government should impose a uniform pension contribution. However, when biases in individuals' perceptions exist, financial education must be adapted to these biases, leading to distortions in the level of education based on the intensity of these biases (Canta & Leroux, 2024). The impact of financial education has also been analyzed in workplace contexts. A study conducted in India demonstrated that financial education and a positive attitude toward finances are key to improving economic well-being. Conversely, it was found that financial stress negatively affects well-being, underscoring the importance of managing attitudes and emotions toward money (Samuel & Kumar, 2024).

In the Colombian context, the impact of the cancellation of the "Ser Pilo Paga" scholarship, which affected the educational decisions of low-income students, was analyzed. The research showed that the cancellation of the scholarship reduced these students' educational aspirations, reflecting how financial aid can influence young people's decisions regarding their academic future (Bernal, Abadía, Álvarez-Arango, et al., 2024). In the child education sector, the Aflatoun financial education program, implemented in China, showed that children who participated in this program improved their financial behavior, particularly in terms of saving and rational consumption. However, it was also observed that this type of education can have negative side effects on children's attitudes and personal development, raising the need to design programs that are tailored to the cultural and contextual characteristics of the areas in which they are implemented (Zhou, Feng, Wu, et al., 2024). Furthermore, in India, the "PM Jan Dhan Yojana" program, which focuses on financial inclusion, has proven to be an effective tool for integrating underserved segments of the population into the formal banking system, promoting financial awareness and contributing to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, especially concerning poverty eradication (Jalota, Sharma, Barik & Chauhan, 2024).

In the United States, the impact of financial education on saving behaviors has also been studied. It was found that both mandatory and voluntary financial education have positive effects on savings, with these effects being amplified when individuals are exposed to financial education multiple times throughout their lives (Walstad & Wagner, 2022). Lastly, in Sweden, research has analyzed how emotions play a crucial role in financial education. It was observed that emotions such as fear, anxiety, and confidence are strategically used in financial education courses to hold citizens accountable for their financial security. This demonstrates how financial education is not only a cognitive process but also an emotional one that influences individuals' economic decisions (Pettersson & Wettergren, 2020). Empirical evidence highlights how financial education affects various aspects of economic behavior, ranging from financial literacy to well-being, employment, and educational decisions. Research suggests that it is crucial to design financial education programs tailored to the demographic, social, and economic characteristics of the target groups to maximize their benefits and ensure a significant improvement in individuals' financial well-being. Therefore, in the discussion on the impact of financial education on financial capabilities, we can propose the following hypothesis:

H1. Financial education level influence significantly in financial capabilities

This hypothesis is supported by findings from various studies that emphasize how financial education has positive effects on economic decision-making and individuals' financial behavior. Guerini, Masciandaro, and Papini (2024) argue that public policies promoting financial education can significantly enhance financial literacy. In line with this, Song, Li, and Wu (2024) confirm that financial inclusion, as key component of financial education, has a positive effect on employment and the economic opportunities available to individuals. In this sense, educational development acts as a crucial moderator in enhancing financial capabilities, further supporting our hypothesis.

Additionally, Samuel and Kumar (2024) demonstrate that financial education, coupled with a positive attitude toward finances, has direct effects on financial well-being. Individuals with greater financial education tend to experience less financial stress and possess better skills in managing their resources, reinforcing the notion that financial education enhances individuals' financial capabilities. Canta and Leroux (2024) suggest that financial education can play a pivotal role in decision-making regarding pensions and savings, as it helps individuals better understand the risks and benefits of available options. In this context, it is observed that biases in the perception of financial returns can be addressed through appropriate educational programs, thus improving people's ability to make informed financial decisions. Consistently, the study by Zhou, Feng, Wu, et al. (2024) on financial education for children shows that children participating in financial education programs develop better saving and consumption habits. Although some negative effects were identified concerning attitudes and personality traits, the study overall emphasizes how financial education from an early age can foster long-term improvements in financial capabilities. Therefore, based on these studies, it can be stated that financial education has a positive and significant impact on individuals' financial capabilities. It not only enhances financial literacy but also contributes to economic well-being, informed decision-making, and financial inclusion. This reinforces the proposed hypothesis regarding the significant influence of financial education on financial capabilities.

Financial Attitude

The literature review reveals several studies that substantiate the idea that attitudes significantly influence individuals' financial decisions and behaviors. For instance, Mamo, Hassen, Adem et al. (2021) found that individuals with higher levels of education tended to exhibit more responsible attitudes, suggesting that knowledge and education can shape the way critical decisions are made. This finding can be extended to financial behavior, where a positive attitude toward finances, coupled with a solid educational background, is crucial for making more responsible and effective decisions. In this regard, Hassan, Prasad, and Meek (2020) demonstrated that, despite a lack of knowledge, participants maintained a positive attitude toward learning, supporting the notion that attitudes toward education can improve financial decision-making.

Obreja, Rughiniș, and Rosner (2023) provide an interesting perspective on how conservative attitudes toward science can influence decisions. This pattern is also observed in financial contexts, where individuals with more conservative attitudes may be less inclined to adopt new financial tools, thus limiting their ability to seize emerging economic opportunities. In terms of financial well-being, Kumar, Ahlawat, Deveshwar et al. (2024) concluded that financial attitude is the key determinant of men's financial behavior in peri-urban areas, underscoring the importance of cultivating a positive attitude toward finances as a foundation for economic stability. Similarly, She, Ma, Pahlevan Sharif et al. (2024) found that, among Malaysian millennials, a positive attitude and good financial knowledge correlated with better long-term financial outcomes. In evaluating financial literacy, attitude is as important as knowledge and behavior (Martino & Ventre, 2023). Saving and investment decisions largely depend on one's attitude toward finances, making it essential to maintain a positive and well-informed mindset.

Furthermore, financial socialization, particularly within the household, has a profound impact on the financial attitudes of young people, with parents playing a key role in shaping these attitudes (Abdul Ghafoor & Akhtar, 2024). On the other hand, Nayak, Mahakud, Mahalik et al. (2024) conducted a study in rural areas of India and found that despite efforts to promote financial education, attitudes toward financial behavior remained inadequate, thus hindering financial inclusion. This finding reinforces the need to change attitudes toward financial management, particularly in areas with limited access to resources and financial education. Additionally, Vieira, Potrich, Bressan, and Klein (2021) found that a positive financial attitude improved financial resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting how a positive mindset can help individuals adapt to economic adversities and maintain their financial stability. The appropriate financial attitude is essential for achieving economic well-being, alongside knowledge and the adoption of responsible financial behaviors (Bhatia & Singh, 2024).

A risk-taking attitude is crucial for entrepreneurship, as individuals with this mindset are more likely to engage in business activities (Xu & Jiang, 2024). Similarly, a positive attitude toward risk plays a determining role in saving behavior and long-term financial decision-making (Ananda, Kumar & Dalwai, 2024). In their study on financial literacy in rural areas of Punjab, Bansal and Kaur (2024) identified that women in these regions held a more negative attitude toward financial management, which was correlated with low financial literacy. This finding highlights the importance of improving financial education and fostering a positive attitude toward money, particularly among women in rural areas. In relation to digital and technological themes, Marconi, Marinucci, and Paladino (2024) demonstrated that digital skills and financial knowledge play a key role in the adoption of digital financial services. Individuals with better digital competencies tend to have a more positive attitude toward using technological tools for financial management, facilitating improved financial administration.

Similarly, the work of Da Cunha et al. (2019) showed that responsible attitudes influence purchasing decisions, which can also be applied to financial behavior. A positive attitude toward the responsible management of financial resources translates into more prudent saving and investment decisions. Finally, the study by Islam et al. (2023) on the adoption of cryptocurrencies in Bangladesh indicates that both knowledge and a positive attitude toward cryptocurrencies are crucial factors in their adoption. This finding underscores how financial attitudes can affect people's willingness to embrace new financial technologies. Similarly, Aman, Motonishi, and Yamane (2024) observed that individuals with a strong financial ethic tended to avoid investing in risky assets, potentially limiting their long-term returns. This reinforces the idea that conservative attitudes toward risk significantly influence financial decisions and, consequently, economic well-being. Based on these findings, we can formulate the hypothesis regarding the influence of financial attitudes on financial capabilities:

H2. Financial attitude influence in financial capabilities

This hypothesis is supported by several studies that highlight the relationship between a positive attitude toward finances and a better ability to make responsible financial decisions. For example, Kumar et al. (2024) and She et al. (2024) demonstrate that a favorable attitude toward finances improves financial behavior. Additionally, Martino and Ventre (2023) suggest that a positive attitude, combined with financial knowledge, influences decisions related to saving and investing, key elements for financial capabilities. Vieira, Potrich, Bressan, and Klein (2021) emphasize that a positive financial attitude increases economic resilience, enabling individuals to better manage financial challenges. Abdul and Akhtar (2024) show that financial socialization at home fosters responsible attitudes and contributes to the development of better financial capabilities. Bhatia and Singh (2024) and Ananda et al. (2024) highlight that a well-managed open attitude toward risk supports responsible financial decisions, improving long-term saving and investment capabilities. Finally, Marconi et al. (2024) argue that a positive attitude toward digital technologies, combined with financial knowledge, facilitates personal financial management through digital tools.

Financial Advice

In specialized literature, evidence highlights the importance of financial advisory services and their crucial role in sustainability, as well as in how businesses and individuals navigate new economic challenges. According to de Jong & Wagensveld (2024), financial advisors have the ability to influence the sustainability goals of individuals, and particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), not only from an economic perspective but also from social and ecological viewpoints. Specifically, in the case of businesses, by adopting a more comprehensive approach, advisors can guide SMEs to create multiple forms of value and align with global sustainability objectives. However, sustainability is not only a business concern; it also affects the way advisors manage risks. A study by Megeid (2024) highlights how climate risk disclosure can enhance financial management, emphasizing the need for advisors to consider these factors when guiding sustainable investments. It is crucial for financial advisors to be familiar with ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) criteria, as these factors will increasingly influence investment decisions, as noted by Dong & Du (2024). The energy transition is increasingly marked by the need to assess how investment decisions impact the environment, and advisors bear the responsibility of integrating these factors into their financial advice.

With the rise of financial technologies (fintech), advisors must also stay updated on digital advancements. Yadav & Banerji (2024) argue that digital financial literacy is essential for advisors to offer relevant services in a rapidly evolving environment. This also raises regulatory challenges, as observed in Busch’s (2024) study, which discusses how changes in EU regulations may affect advisory services regarding international investments, particularly in post-Brexit contexts. On the other hand, Ashraf (2024) emphasizes how automation in accounting and financial reporting improves the quality of financial advice by reducing errors and increasing efficiency, although it also raises concerns about internal control. Financial advisors must also learn from other fields. Bonadonna et al. (2024) demonstrate how, when addressing natural disaster risks such as volcanic events, a similar approach can be applied to financial advisory, considering both immediate and long-term risks. This holistic approach can be useful when advisors help clients manage complex situations like severe health conditions, as discussed in the study by Watson et al. (2023). Health disruptions can lead to significant financial burdens, so advisors can play a key role in helping clients plan for health-related contingencies. In line with this, the study by Dare et al. (2023) on financial self-efficacy emphasizes how advisors can foster positive financial behaviors to improve their clients' financial well-being, helping them reduce stress and increase economic security.

An interesting example is the study by Kirikkaleli (2024), which highlights how financial innovation and investments in renewable energy can benefit both the environment and economic well-being. Financial advisors must be aware of how these investments can align both the financial and sustainable interests of clients. Moreover, advisors can also assist clients in managing financial stress in unforeseen situations, as demonstrated in the study by Lakshmanan et al. (2022) on the financial burden of families with premature babies. Effective advisory can alleviate these issues through proper planning and access to resources such as social security. In an increasingly interconnected world, economic well-being is also influenced by energy policies and new technologies, as demonstrated by the study of Subhan et al. (2024) on the relationship between renewable energy and economic well-being in India. In their findings, the authors suggest that financial advisors must consider these factors when offering investment strategies related to the energy transition. On the other hand, Zhang et al. (2021) show that clients still prefer experienced human advisors over robo-advisors, underscoring the importance of personal relationships in financial advising. Although robo-advisors are on the rise, clients still value the experience and the ability of advisors to understand not only financial aspects but also the values and emotions associated with money.

Finally, Scholz (2024) discusses how the popularity of robo-advisors is changing the financial industry. Traditional financial advisors must adapt to this new reality by integrating artificial intelligence and more sustainable investment strategies to remain relevant. Meanwhile, the impact of FinTech technologies on household life, as reviewed by Agarwal & Chua (2020), has transformed consumption and saving decisions, making the role of the financial advisor as a guide to navigating these new technologies safely even more relevant. As noted in the study by Lozza et al. (2022), advisors can improve client relationships by understanding the emotional associations clients have with money, which will strengthen trust and loyalty in their relationship. According to the specialized literature on the topic, it is undeniable that financial advising is evolving to adapt to new risks, technologies, and client needs, including individuals, businesses, and any type of organization that requires financial advisory services. Financial advisors must integrate multiple dimensions into their strategies, ranging from sustainability and digitalization to holistic well-being planning, all with the aim of providing a relevant and comprehensive service that addresses the current and future challenges of their clients. Therefore, in the discussion on the influence of financial advising on financial capabilities, we can pose the following hypothesis:

H3. Financial advice influence significantly in financial capabilities

Hypothesis H3, which posits that financial advising influences financial capabilities, is supported by several studies. Dare et al. (2023) highlight that advising enhances financial self-efficacy, while de Jong & Wagensveld (2024) suggest that advisors help businesses make sustainable decisions, thereby strengthening their capabilities. Zhang et al. (2021) show that the experience of advisors improves financial decisions, and Yadav & Banerji (2024) emphasize the role of advisors in digital financial literacy. Additionally, Agarwal & Chua (2020) and Lozza et al. (2022) underline how advising improves financial skills by integrating technologies and emotional aspects of money management.

Financial Behaviour and Knowledge

Financial knowledge is a topic that has garnered significant attention in contemporary research due to its impact on individuals' financial decisions and how these decisions can affect both economic well-being and financial stability. Various factors, such as financial experience, education, investor behavior, and socioeconomic differences (including racial and gender disparities), play a crucial role in the acquisition and application of financial knowledge. One of the most significant studies is that of Chen, Birkenmaier, and Garand (2024), who explore the relationship between financial knowledge and racial differences in the United States. Through a detailed analysis of data from the 2018 National Financial Capability Study, the authors discover that racial minority groups, such as African Americans and Latinos, have lower levels of financial knowledge compared to whites. However, the authors also point out that traditional methodology, which group correct and incorrect answers together with "Don't Know" (DK), do not adequately reflect the actual knowledge of these groups. Minority groups tend to respond more frequently with "Don't Know," but this does not necessarily indicate a lack of knowledge. Instead, it could be related to the lack of financial experience these groups possess, as they are less likely to have access to financial products such as savings accounts, mortgages, or investments, which in turn affects their performance on financial knowledge tests.

In the European context, Bellofatto, Broihanne, and D’Hondt (2024) investigate the impact of online information tools on the behavior of retail investors after the implementation of the MiFID regulation. The authors conclude that financial literacy and financial education are crucial factors in acquiring financial knowledge. However, the effects of this knowledge on investor behavior are mixed: while knowledge improves portfolio diversification, it also increases transaction intensity and reduces net returns. This suggests that acquiring more financial knowledge does not always lead to better investment decisions but may increase activity without necessarily improving outcomes. In India, Saini, Sharma, and Parayitam (2024) examine the relationship between financial knowledge and investment strategy in the context of pension plans. The authors find that greater financial knowledge is positively related to better investment strategy and greater satisfaction among investors. Additionally, they highlight the importance of moderating factors such as future financial goals and financial security, which influence how financial knowledge impacts investor satisfaction.

This study underscores that combining financial knowledge with future goals and concerns plays a key role in financial planning. On the other hand, Cheng, Niu, and Zou (2024) explore how financial knowledge influences the financial behavior of university students in China using a moderated mediation model. The results show that financial knowledge has a positive effect on the rationality of students' financial behavior. However, this impact is partially mediated by self-efficacy, suggesting that not only knowledge but also personal confidence in decision-making is crucial for students to act rationally in their finances. In a different methodological approach, Palazzo, Iannario, and Palumbo (2024) present an innovative analysis using Item Response Theory (IRT) combined with Archetypal Analysis (AA) to identify homogeneous groups according to their financial knowledge levels. In their study, they apply this methodology to a sample of 625 Italians. In their results, they find that this approach allows for better segmentation of groups based on their financial knowledge. Based on their findings, the authors consider these results useful for both public policy formulation and the design of personalized educational interventions.

In the work of Rostamkalaei, Nitani, and Riding (2019), the differences between self-employed workers and employees in terms of financial knowledge and behavior are explored. Although self-employed workers do not show a significant difference in financial knowledge compared to employees, they are more likely to resort to alternative financial services (AFS), such as payday loans. This tendency is partly due to greater financial self-efficacy, meaning that self-employed individuals with more confidence in their financial skills tend to make riskier decisions, such as using expensive financial services. Similarly, Nitani, Riding, and Orser (2019) investigate the use of alternative financial services among self-employed workers, finding that they tend to use high-cost loans more often, which could jeopardize the financial stability of their businesses. The authors suggest that, although self-employed workers' financial knowledge is not significantly different from that of employees, self-efficacy plays a fundamental role in making risky financial decisions.

In the realm of financial anxiety, a study by Kim, Cho, and Xiao (2023) analyzes the relationship between the use of alternative financial services (AFS) and financial anxiety. The results reveal that the use of AFS is associated with increased financial anxiety, but this effect is moderated by financial knowledge. For non-users of AFS, financial knowledge has a negative effect on anxiety, suggesting that those who are better informed about finance experience less anxiety. However, for AFS users, financial knowledge does not seem to have the same effect on reducing anxiety, raising implications about how to intervene to reduce financial anxiety. Wang’s (2009) work adds a gender dimension to the analysis of financial knowledge. The results show that gender differences are significant, with men tending to have greater objective and subjective financial knowledge, as well as a higher risk propensity. Furthermore, investors' subjective knowledge appears to mediate the relationship between their objective knowledge and their willingness to take risks, highlighting how financial knowledge is not only about

H4. Financial knowledge influence significantly in financial capabilities

Various studies support the idea that financial knowledge has a significant impact on individuals' financial capabilities. Chen, Birkenmaier, and Garand (2024) indicate that traditional measures of financial knowledge may not accurately reflect the capabilities of minority racial groups, as these groups tend to select "don’t know" responses more frequently, which could mask a higher level of actual knowledge. This suggests that financial knowledge is not only related to theoretical understanding but also to financial experience, thus reinforcing the importance of financial knowledge in the development of financial capabilities.

Bellofatto, Broihanne, and D’Hondt (2024) highlight that access to information tools can improve investment decision-making, demonstrating how financial knowledge can positively influence portfolio diversification and decision improvement. However, they also warn of the potential negative effects if this knowledge is managed excessively or inappropriately. In a different context, Saini, Sharma, and Parayitam (2024) found that financial knowledge is positively associated with better investment strategies and greater investor satisfaction, suggesting that increased financial education significantly contributes to individuals' ability to make more informed and satisfactory financial decisions. On the other hand, Cheng, Niu, and Zou (2024) explain that financial knowledge not only affects decisions but also improves confidence in one's ability to manage personal finances, as demonstrated by the mediation of self-efficacy in the relationship between knowledge and rational financial behavior. These findings align with the analysis by Palazzo, Iannario, and Palumbo (2024), who, using advanced statistical models, showed that financial knowledge can generate homogeneous profiles of individuals, which helps in understanding how this knowledge contributes to financial decision-making.

Finally, in the context of self-employed workers, Rostamkalaei, Nitani, and Riding (2019), and Nitani, Riding, and Orser (2019) suggest that, although financial knowledge does not significantly differ between self-employed individuals and employees, the ability to make effective financial decisions is influenced by knowledge, especially when it comes to avoiding high-risk practices like alternative financial services (AFS). These findings reinforce the idea that financial knowledge not only enhances decision-making but, is also deeply linked to the development of effective financial capabilities by influencing how individuals manage their resources and make informed decisions throughout their lives.

Financial Capabilities and Financial Well-Being

In the area of financial well-being, it is essential to establish a conceptual definition that allows us to understand its scope and the origins of this concept. In this regard, Brüggen et al. (2017) propose a new definition of financial well-being, describing it as the individual's perception of their desired standard of living and future financial freedom. It is clear that financial well-being stems from sound finances, which result from proper management of an individual’s economic resources, supported by financial capability. The relationship between financial capability and financial well-being has been extensively researched; however, few studies have adopted a longitudinal perspective with long-term national data. Xiao, Kim, and Lee (2024) address this gap by using data from the five waves of the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) between 2009 and 2021. Their study shows a positive relationship between financial capability indexes and financial well-being, highlighting the role of subjective financial knowledge and desirable financial behaviors.

Furthermore, Abdul, Ghafoor, and Akhtar (2024) explore the impact of parental financial socialization, observing how parental strategies, especially with daughters, influence the financial well-being of Generation Z. Gignac et al. (2024) investigate the impact of homeownership on the financial well-being of older adults in Australia, finding that ownership, along with high financial literacy, improves well-being by preventing over-indebtedness. Nykiforuk, Belon, and de Leeuw (2023) propose a public health approach to address financial strain resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, which would contribute to reducing inequities in individuals' financial health. On a global scale, El Anshasy, Shamsuddin, and Katsaiti (2023) find that negative perceptions of financial well-being drive migration, particularly among those with a pessimistic view of the economic future. This is in line with the work of Morrissey, Taylor, and Tu (2023), who demonstrate how childhood economic difficulties affect mental well-being in adulthood, especially in middle age. Similarly, Karthika et al. (2023) discover that, in old age, financial well-being depends on pension systems and access to healthcare services.

In other contexts, financial well-being has also been studied. Nasr et al. (2024) document how the economic crisis in Lebanon severely affected the financial well-being of university students due to financial stress. Cultural differences in the conceptualization of financial well-being highlight the need to adapt measurement instruments accordingly, as noted by Sollis, Biddle, and Maulana (2024). Financial stress became particularly prominent during the pandemic; in this regard, the study by Kelley, Lee, and LeBaron-Black (2023) shows how fluctuations in financial stress during the pandemic affected family relationships and financial behavior. Zhang and Fan (2024) explore the impact of fintechs, highlighting that excessive use of fintech can harm financial behavior and, consequently, financial well-being. Regarding gender, Hasan, Jayasinghe, and Selvanathan (2024) examine how gender and social class affect financial well-being in Bangladesh, concluding that health is the main determinant, followed by finances. Mundi, Vashisht, and Rao (2024) find that retirees with fixed pensions and high social capital enjoy greater financial well-being in India. Kim and Lee (2024) analyze the impact of student loans on financial well-being in the U.S. during the pandemic, finding an increase in financial anxiety and delinquency in payments.

Several studies support the idea that a positive perception of financial status can mitigate the negative effects of a low credit score on health, leading to sustainable financial well-being. In this context, the adoption of Industry 4.0 technologies has a positive impact on financial well-being. In this regard, the study by Wan Ismail, Madah Marzuki, and Lode (2024) explores how the adoption of these technologies affects both the financial and social well-being of employees in Malaysia, concluding that financial transparency and technological adoption are essential. Similarly, Gafoor and Amilan (2024) examine how fintech adoption enhances the financial capacity and well-being of individuals with disabilities, facilitating access to financial services, with financial literacy being a key factor.

In this regard, Rahman et al. (2021) previously investigated financial well-being within Malaysia's B40 group, concluding that improving financial education and managing stress are key to enhancing financial well-being within this group. In turn, Algarni, Ali, and Ali (2024) emphasize the role of parental financial education in the financial well-being of young Saudis, highlighting financial socialization during childhood. Dhiraj, Kumar, and Rani (2023) found that financial stress in the Indian tourism sector is negatively correlated with the financial well-being of employees, suggesting that improving stress management can improve their financial quality of life. Bashir, Qureshi, and Ilyas (2024) explore how financial well-being impacts labor productivity, with stronger effects in men than in women. Finally, She, Ray, and Ma (2023) report that greater clarity in financial goals and improved knowledge contribute to the financial well-being of Chinese millennials. These studies highlight the importance of financial education, stress reduction, and access to new technologies as key tools for improving financial well-being. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed regarding the influence of financial capacities on financial well-being:

H5. Financial capabilities influence significantly in the financial well-being

Several studies support the hypothesis that financial capabilities significantly influence financial well-being. A key example is the work of Xiao, Kim, and Lee (2024), who demonstrate that financial capability indices are positively related to financial well-being over time, highlighting the role of financial knowledge and desirable financial behavior. Similarly, Gignac et al. (2024) find that financial literacy, combined with homeownership, improves financial well-being, emphasizing the importance of financial capabilities in enhancing well-being. Furthermore, Zhang and Fan (2024) suggest that financial literacy acts as a mediator between the use of fintech technologies and financial well-being, indicating that strong financial knowledge is crucial for improving the latter. Along the same lines, Hasan, Jayasinghe, and Selvanathan (2024) point out that financial capability are key determinants for well-being, as they influence the effective management of personal finances. Lastly, Kim and Lee (2024) demonstrate that a lack of financial skills, such as in the case of student loan borrowers, increases financial anxiety and negatively affects financial well-being, further reinforcing the relationship between financial capabilities and financial well-being. Based on the arguments presented in the literature review regarding the relevant variables, the conceptual model is shown in

Figure 1 below:

Figure 1.

Conceptual model (own).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model (own).

4. Data Analysis and Discussion

The values obtained for the reliability and internal consistency of the database are: Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega, both of which show acceptable values, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.868 and a McDonald’s omega of 0.821. Regarding the values of skewness and kurtosis (

Table 1), the observed values do not align with the theoretical criteria suggested by Kim (2013); therefore, polychoric correlation matrices and Bartlett’s test of sphericity with Kaiser’s measure are employed to verify their suitability. The values obtained from Bartlett’s test of sphericity with Kaiser’s measure show acceptable results, with a Chi-square value of 5098.085 with 703 degrees of freedom and a p-value <0.001. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure is 0.808, demonstrating that factorization of the dataset is feasible. The correlation matrices presented in

Table 2 to

Table 2 show acceptable values, indicating that there is correlation among the items of the instrument, providing evidence that the data matrix is not an identity matrix.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix.

| |

FC1 |

FC2 |

FC3 |

FC4 |

FC5 |

FC6 |

FC7 |

FC8 |

FC9 |

| FC1 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FC2 |

0.402 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FC3 |

0.359 |

0.295 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FC4 |

0.292 |

0.435 |

0.235 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| FC5 |

0.531 |

0.367 |

0.516 |

0.290 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

| FC6 |

0.173 |

0.406 |

0.258 |

0.351 |

0.368 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| FC7 |

0.148 |

0.311 |

0.034 |

0.254 |

0.301 |

0.590 |

1.000 |

|

|

| FC8 |

0.275 |

0.326 |

0.255 |

0.278 |

0.234 |

0.267 |

0.205 |

1.000 |

|

| FC9 |

0.374 |

0.244 |

0.374 |

0.284 |

0.390 |

0.272 |

0.211 |

0.358 |

1.000 |

Table 2.

b Correlation matrix.

Table 2.

b Correlation matrix.

| |

FA10 |

FA11 |

FA12 |

FA13 |

FA14 |

FE15 |

FE16 |

FE17 |

FE18 |

| FA10 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FA11 |

-0.107 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FA12 |

0.491 |

-0.026 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FA13 |

0.209 |

-0.016 |

0.274 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| FA14 |

0.209 |

0.230 |

0.293 |

0.137 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

| FE15 |

-0.002 |

0.225 |

0.045 |

-0.026 |

0.172 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| FE16 |

0.120 |

0.040 |

0.144 |

0.029 |

0.137 |

0.468 |

1.000 |

|

|

| FE17 |

0.087 |

0.063 |

0.092 |

0.060 |

0.184 |

0.475 |

0.632 |

1.000 |

|

| FE18 |

0.102 |

0.074 |

0.143 |

0.087 |

0.203 |

0.432 |

0.575 |

0.678 |

1.000 |

Table 2.

c Correlation matrix.

Table 2.

c Correlation matrix.

| |

FAt19 |

FAt20 |

FAt21 |

FAt22 |

FAt23 |

FAt24 |

FB25 |

FB26 |

FB27 |

| FAt19 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FAt20 |

-0.017 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FAt21 |

0.363 |

0.038 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FAt22 |

-0.074 |

0.122 |

0.056 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| FAt23 |

-0.124 |

0.305 |

-0.023 |

0.427 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

| FAt24 |

-0.010 |

0.283 |

0.009 |

0.130 |

0.347 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| FB25 |

0.093 |

0.182 |

0.043 |

-0.194 |

0.115 |

0.363 |

1.000 |

|

|

| FB26 |

0.107 |

0.129 |

0.189 |

-0.026 |

-0.050 |

0.096 |

0.389 |

1.000 |

|

| FB27 |

-0.220 |

0.314 |

-0.136 |

0.125 |

0.368 |

0.375 |

0.269 |

0.155 |

1.000 |

Table 2.

d Correlation matrix.

Table 2.

d Correlation matrix.

| |

FB28 |

FB29 |

FB30 |

FWB31 |

FWB32 |

FWB33 |

FWB34 |

FWB35 |

FWB36 |

FWB37 |

FWB38 |

| FB28 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FB29 |

0.426 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FB30 |

0.012 |

0.018 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FWB31 |

0.179 |

0.381 |

0.048 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FWB32 |

0.323 |

0.558 |

-0.078 |

0.531 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FWB33 |

0.219 |

0.335 |

0.152 |

0.396 |

0.457 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

|

| FWB34 |

0.440 |

0.233 |

0.136 |

0.061 |

0.106 |

0.329 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

|

| FWB35 |

0.301 |

0.494 |

0.071 |

0.291 |

0.359 |

0.290 |

0.222 |

1.000 |

|

|

|

| FWB36 |

0.390 |

0.492 |

-0.003 |

0.252 |

0.391 |

0.274 |

0.292 |

0.461 |

1.000 |

|

|

| FWB37 |

0.266 |

0.272 |

0.027 |

0.214 |

0.190 |

0.300 |

0.436 |

0.227 |

0.288 |

1.000 |

|

| FWB38 |

0.404 |

0.542 |

-0.030 |

0.252 |

0.418 |

0.318 |

0.340 |

0.378 |

0.395 |

0.400 |

1.00 |

In the

Table 3 shows the values of the key indicators used to evaluate the quality and adequacy of the factor model, which include: Factor Loading, Squared Multiple Correlation (SMC), 1 - SMC, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). Factor loading describes the magnitude of the relationship between the observed variables and the latent factors, indicating how well each variable is represented by its corresponding factor. The Squared Multiple Correlation (SMC) reflects the proportion of the variance of an observed variable that is explained by the latent factors of the model, while 1 - SMC indicates the portion of the variance that remains unexplained, or the residual "noise" outside of the model. On the other hand, Composite Reliability (CR) measures the internal consistency of the items representing a latent factor, providing an indication of the reliability of the model. A value greater than 0.7 is considered acceptable. Finally, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) assesses convergent validity, determining how much of the variance in the items is explained by the latent factor, with a value greater than 0.5 indicating adequate validity. These indicators are crucial for verifying that the observed variables are properly associated with the latent factors and that the model demonstrates adequate reliability and validity, ensuring the robustness of the results. The values obtained are acceptable.

Table 3.

Factor Loading, Squared Multiple Correlation (SMC), 1 - SMC, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

Table 3.

Factor Loading, Squared Multiple Correlation (SMC), 1 - SMC, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

| Items |

Initial |

Extraction |

Factor loading |

SMC |

1-SMC |

AVE |

CR |

| FC1 |

1.000 |

0.479 |

0.6923 |

0.4793 |

0.5207 |

0.564 |

0.941 |

| FC2 |

1.000 |

0.584 |

0.7642 |

0.5840 |

0.4160 |

| FC3 |

1.000 |

0.658 |

0.8111 |

0.6579 |

0.3421 |

| FC4 |

1.000 |

0.386 |

0.6215 |

0.3863 |

0.6137 |

| FC5 |

1.000 |

0.635 |

0.7967 |

0.6347 |

0.3653 |

| FC6 |

1.000 |

0.623 |

0.7893 |

0.6230 |

0.3770 |

| FC7 |

1.000 |

0.604 |

0.7772 |

0.6041 |

0.3959 |

| FC8 |

1.000 |

0.607 |

0.7790 |

0.6068 |

0.3932 |

| FC9 |

1.000 |

0.491 |

0.7006 |

0.4909 |

0.5091 |

| FA10 |

1.000 |

0.569 |

0.7546 |

0.5694 |

0.4306 |

| FA11 |

1.000 |

0.606 |

0.7784 |

0.6059 |

0.3941 |

| FA12 |

1.000 |

0.611 |

0.7814 |

0.6106 |

0.3894 |

| FA13 |

1.000 |

0.454 |

0.6738 |

0.4540 |

0.5460 |

| FA14 |

1.000 |

0.447 |

0.6687 |

0.4472 |

0.5528 |

| FE15 |

1.000 |

0.558 |

0.7470 |

0.5580 |

0.4420 |

| FE16 |

1.000 |

0.718 |

0.8476 |

0.7184 |

0.2816 |

| FE17 |

1.000 |

0.763 |

0.8735 |

0.7631 |

0.2369 |

| FE18 |

1.000 |

0.700 |

0.8367 |

0.7001 |

0.2999 |

| FAt19 |

1.000 |

0.622 |

0.7884 |

0.6216 |

0.3784 |

| FAt20 |

1.000 |

0.503 |

0.7092 |

0.5030 |

0.4970 |

| FAt21 |

1.000 |

0.631 |

0.7943 |

0.6309 |

0.3691 |

| FAt22 |

1.000 |

0.524 |

0.7242 |

0.5244 |

0.4756 |

| FAt23 |

1.000 |

0.549 |

0.7410 |

0.5491 |

0.4509 |

| FAt24 |

1.000 |

0.674 |

0.8209 |

0.6739 |

0.3261 |

| FB25 |

1.000 |

0.625 |

0.7904 |

0.6247 |

0.3753 |

| FB26 |

1.000 |

0.569 |

0.7541 |

0.5687 |

0.4313 |

| FB27 |

1.000 |

0.588 |

0.7669 |

0.5882 |

0.4118 |

| FB28 |

1.000 |

0.635 |

0.7971 |

0.6353 |

0.3647 |

| FB29 |

1.000 |

0.652 |

0.8074 |

0.6519 |

0.3481 |

| FB30 |

1.000 |

0.445 |

0.6675 |

0.4455 |

0.5545 |

| FWB31 |

1.000 |

0.471 |

0.6863 |

0.4709 |

0.5291 |

| FWB32 |

1.000 |

0.647 |

0.8044 |

0.6471 |

0.3529 |

| FWB33 |

1.000 |

0.485 |

0.6961 |

0.4846 |

0.5154 |

| FWB34 |

1.000 |

0.568 |

0.7534 |

0.5677 |

0.4323 |

| FWB35 |

1.000 |

0.468 |

0.6843 |

0.4683 |

0.5317 |

| FWB36 |

1.000 |

0.456 |

0.6749 |

0.4555 |

0.5445 |

| FWB37 |

1.000 |

0.677 |

0.8231 |

0.6774 |

0.3226 |

| FWB38 |

1.000 |

0.625 |

0.7906 |

0.6250 |

0.3750 |

Now the Structural Equation Model (SEM) is show, which aims to analyze the relationships between the study variables.

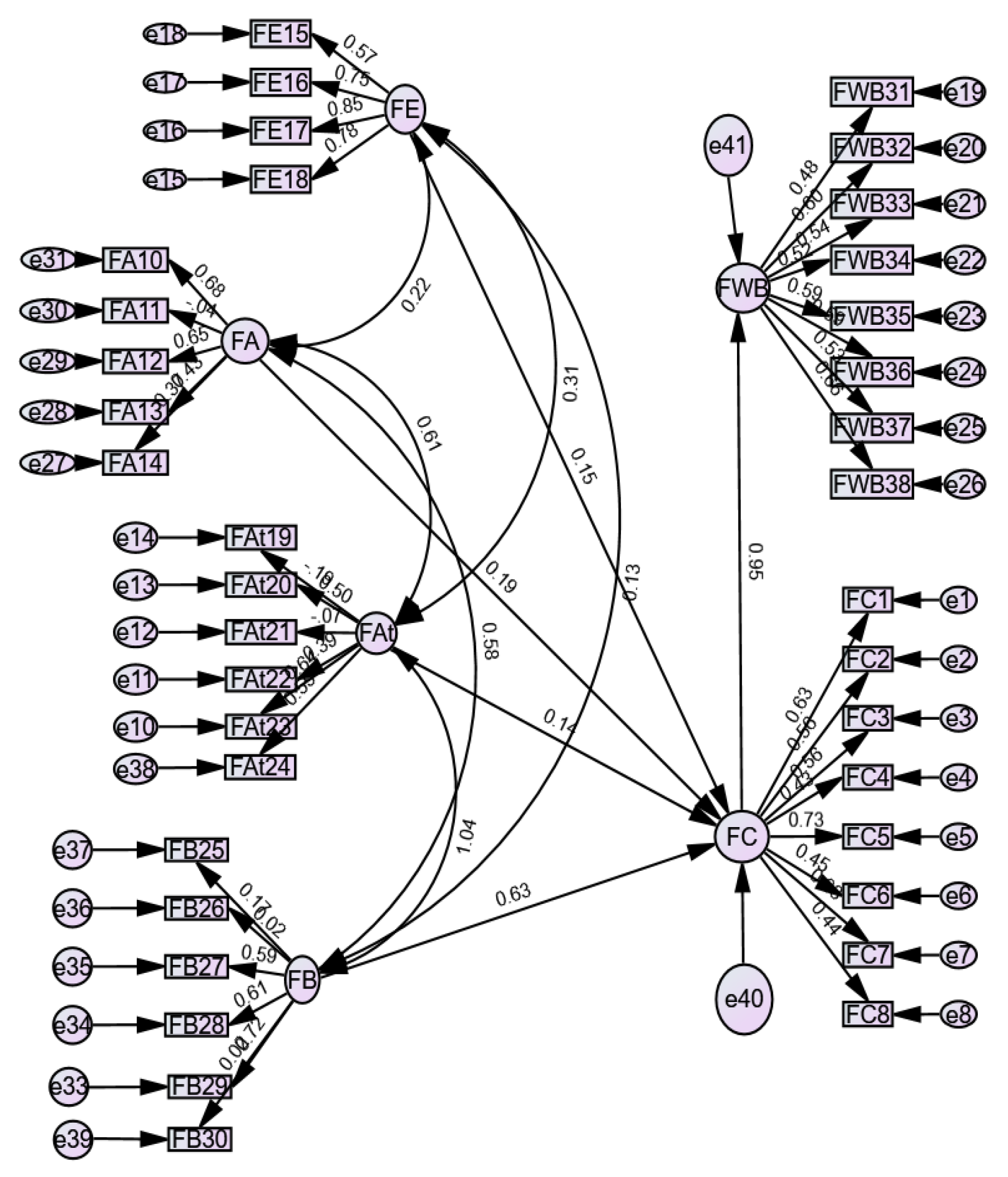

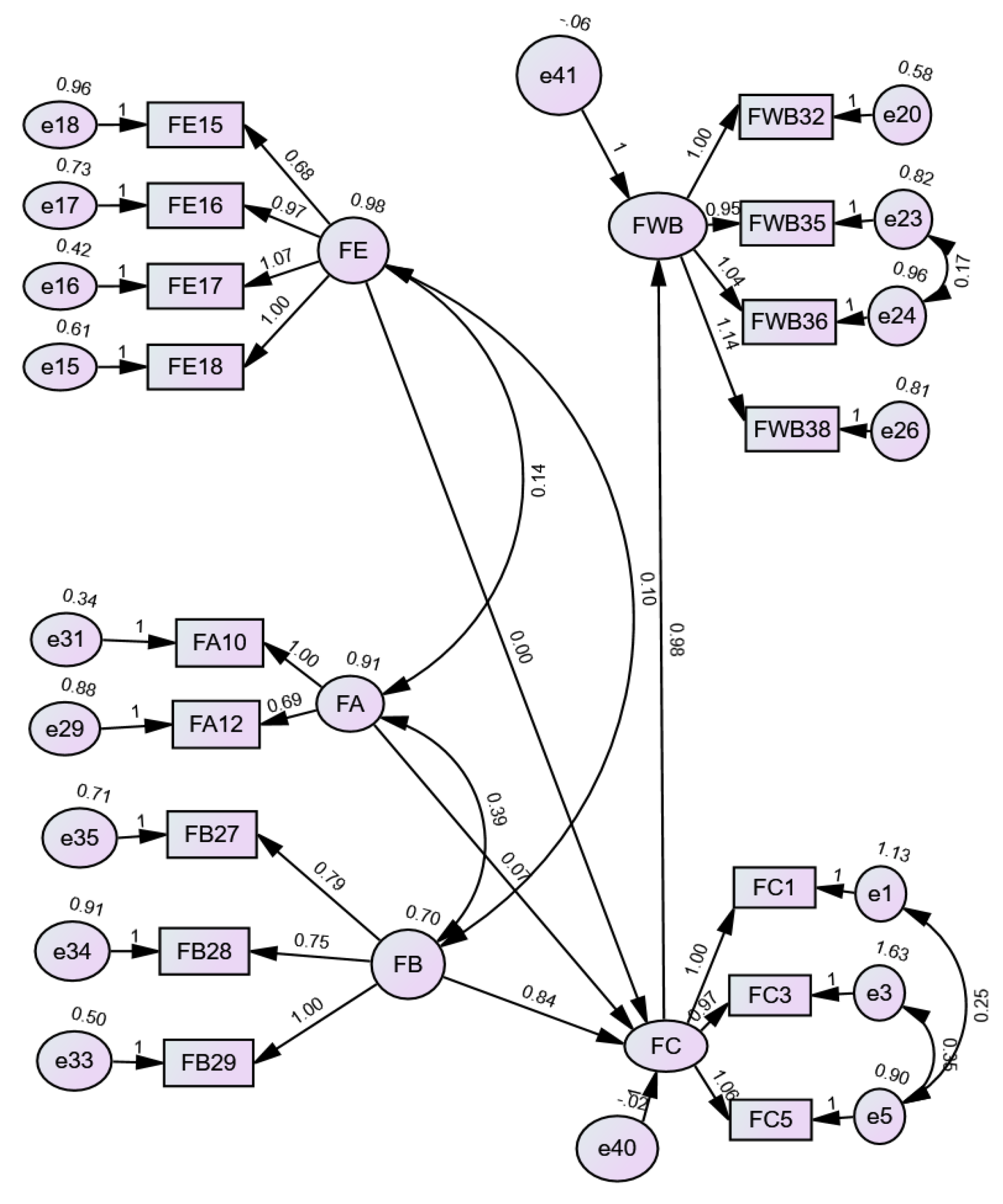

Figure 1 shows the initial measurement model, based on the scale used by Musaddag and Bushra (2024), which integrates the dimensions of Financial Education (Widyastuti et al., 2020), Financial Attitudes (Çoşkun & Dalziel, 2020), Financial Advice (Khan et al., 2022), Financial Knowledge, Financial Capacities (Khan et al., 2022), and Financial Behavior (Çoşkun & Dalziel, 2020). This model defines the connections between the observed and latent variables, allowing for the assessment of their validity and reliability.

Figure 1.

Initial measurement model.

Figure 1.

Initial measurement model.

The values for the fit index, structural fit, and parsimony presented by the model are PCMIN/DF (3.587), RMR (0.133), GFI (0.688), AGFI (0.645), PGFI (0.605), TLI (0.611), CFI (0.639), PRATIO (0.928), PNFI (0.524), PCFI (0.593), and RMSEA (0.087). These indices do not fully align with the theoretical criteria suggested, indicating that adjustments to the model are necessary.

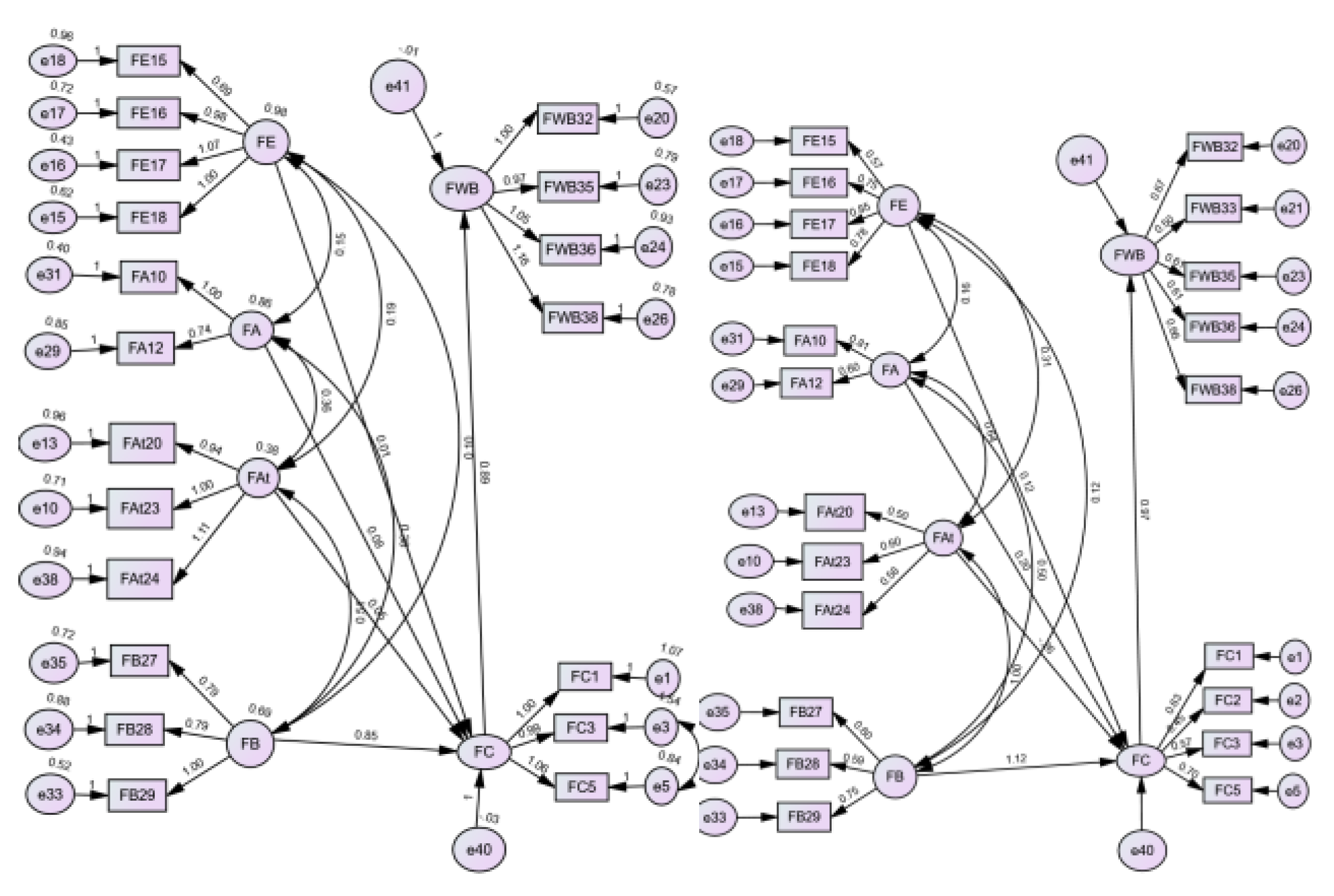

The following figures show the adjustments in the factors FA, FAt, FB, FWB and FC, which are made for the validation of the confirmatory model.

Figure 2.

Final models final FE, FA, FAt, FB, FWB and FC.

Figure 2.

Final models final FE, FA, FAt, FB, FWB and FC.

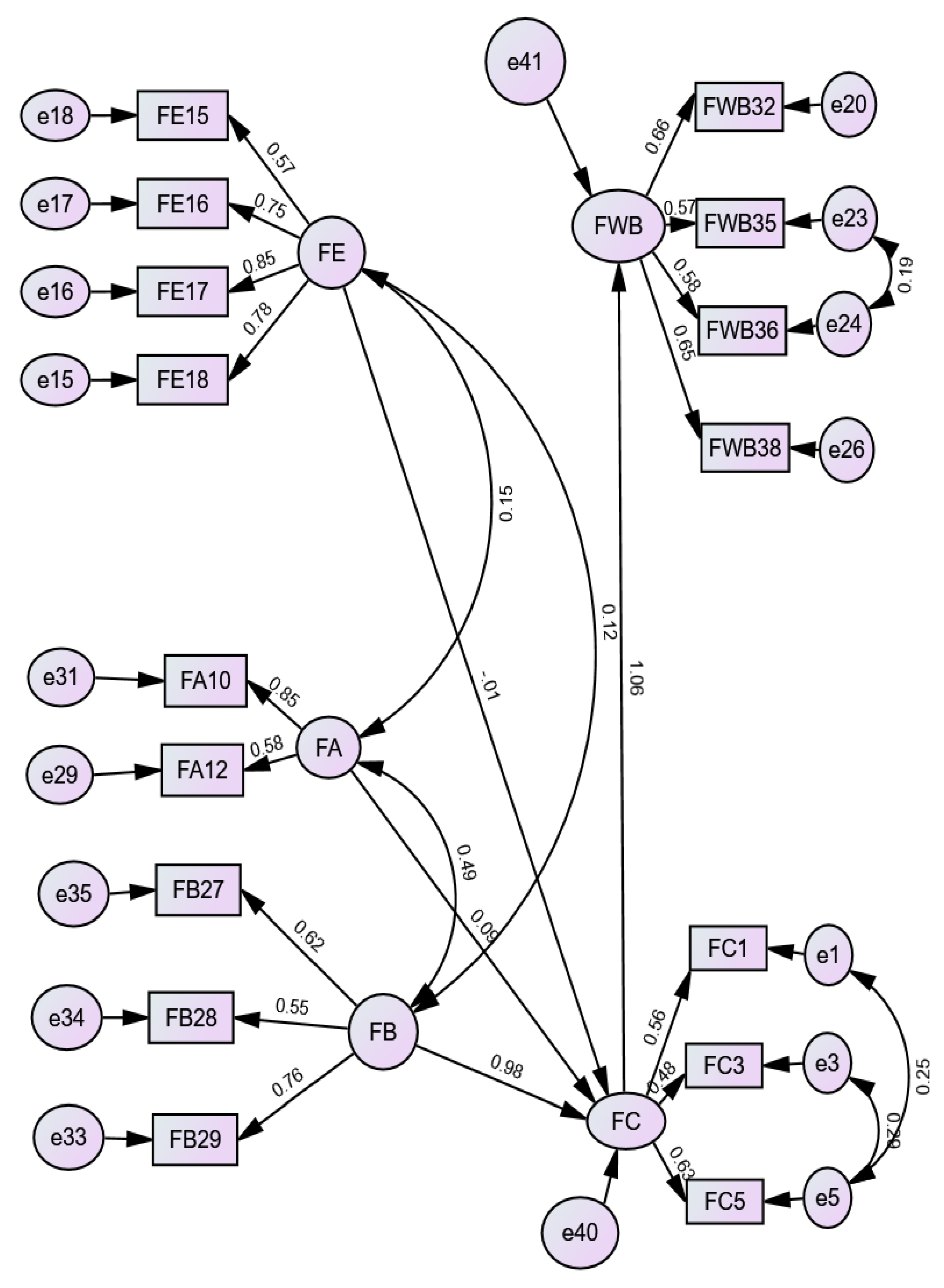

Figure 2.

Models final FE, FA, FAt, FB, FWB and FC, with standardize estimated and non-standardize (own).

Figure 2.

Models final FE, FA, FAt, FB, FWB and FC, with standardize estimated and non-standardize (own).

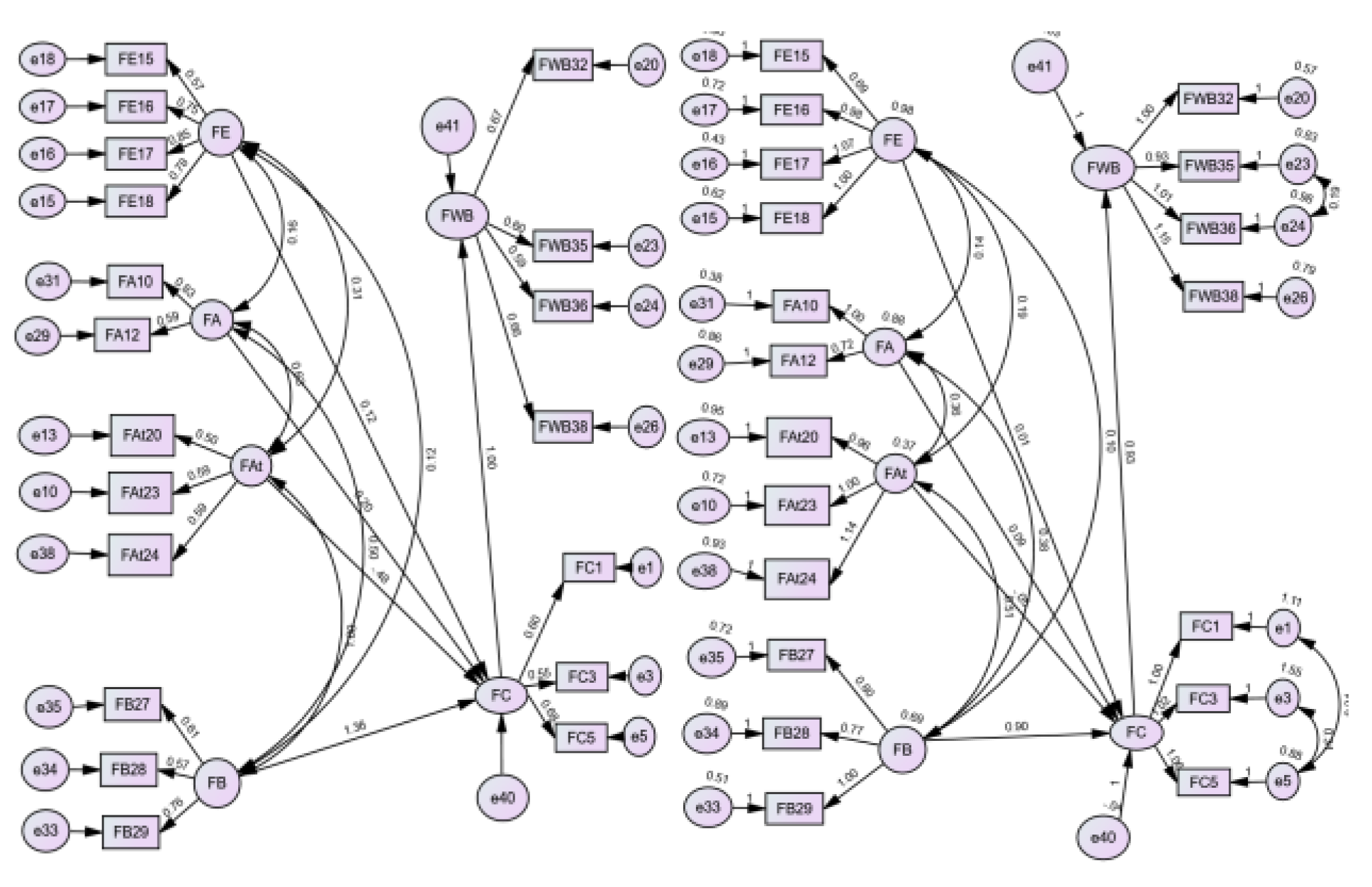

The final model presented in

Figure 2 shows the best absolute fit

, structural fit, and parsimony according to the theoretical criteria suggested. The following provides a detailed explanation:

Measures of Absolute Fit: The obtained Chi-Square (χ²/d.f.) value was 2.476, which falls within the acceptable range (between 2 and 5), indicating a good fit of the model. Regarding the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the value was 0.066, which is below the threshold of 0.08, suggesting an adequate fit. For the Goodness-of-Fit (GFI) index, the value was 0.923, surpassing the recommended threshold of 0.90, indicating a good fit in this index. The Adjusted Goodness-of-Fit (AGFI) value was 0.888, exceeding the minimum threshold of 0.80, suggesting a good fit of the model. For the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) index, the value was 0.092, slightly above the acceptable value for this sample size (0.08). Measures of Incremental Fit: Regarding the Normed Fit Index (NFI), the value was 0.887, close to the minimum threshold of 0.90 but not reaching the optimal value, suggesting that the fit could be improved. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) value was 0.929, which is above the minimum threshold of 0.90, indicating a good fit of the model. For the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the value was 0.909, greater than 0.90, also suggesting an adequate fit. Measures of Parsimony: The Parsimonious Goodness-of-Fit Index (PGFI) yielded a value of 0.929, above the minimum threshold of 0.50, indicating a reasonable fit in terms of parsimony. Similarly, the Parsimonious Normed Fit Index (PNFI) yielded a value of 0.695, surpassing the minimum threshold of 0.50, suggesting an adequate fit in terms of parsimony. Finally, the Parsimonious Comparative Fit Index (PCFI) presented a value of 0.728, exceeding the minimum threshold, indicating an acceptable and reasonable fit for the model.

Based on the previously obtained data, which confirmed the best model, it can be concluded that financial education does not significantly influence the participants' financial capacities. Similarly, financial attitude does not present evidence of influencing financial capacities, nor does it show significant factor loadings in the model with standardized estimators and was thus, excluded from the final model. On the other hand, financial counseling and financial behavior and knowledge showed a slight relationship with financial capacities. However, financial knowledge and behavior exhibited a highly significant influence (0.84) on financial capacities. This might be attributed to the financial education component, as knowledge is acquired through an educational process; however, this was not the case in the final measurement model. Financial capacities have a significant impact on financial well-being (0.98). Moreover, the relationship between the dimensions of financial education, knowledge, and financial behavior shows a relationship of 0.12 and 0.15 between financial education and financial counseling, with a higher relationship between financial counseling and financial knowledge and behavior (0.49).