1. Introduction

Impaired upper limb function greatly affects activities of daily living, which are the basis for independent functioning [

1,

2]. Upper limb disability resulting from musculoskeletal system dysfunction constitutes a significant health issue both in the general population and among patients receiving primary healthcare services. The prevalence of upper limb disorders varies considerably, ranging from 2% to 53%, according to studies, with higher incidence rates observed among students and professionally active individuals. Musculoskeletal complaints affecting the upper limb are associated with specific pathological conditions, such as rotator cuff tendinitis, adhesive capsulitis, lateral epicondylitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and De Quervain’s disease. In some cases, these disorders present with nonspecific symptoms, making their classification and diagnosis more challenging [

3].

It is not only orthopedic conditions that cause upper limb impairment. Many neurological diseases can cause upper limb impairment [

4]. For example, stroke, in the United States of America alone, more than 795,000 people per year have a stroke [

4,

5]. Stroke-related costs in the United States came to nearly

$56.2 billion between 2019 and 2020. Costs include the cost of health care services, medicines to treat stroke, and missed days of work [

6]. Among the numerous neurological deficits that occur in post-stroke patients, loss of upper limb motor function is the most common, affecting 77.4% of patients. This impairment persists for more than six months in 89% of those who have experienced loss of upper limb function, significantly affecting their quality of life. The process of neuroplasticity enables partial or full recovery of function, and its effectiveness can be enhanced by intensive and repetitive motor activity as part of rehabilitation therapy [

7]. The next disease we can mention is multiple sclerosis. The number of people affected by multiple sclerosis worldwide was estimated to rise to 2.8 million in 2020. Using the same methodology as in 2013, this number was estimated to be 30% higher than in 2013. The global prevalence in 2020 was 35.9 cases per 100,000 people [

8], 60% of people with multiple sclerosis have impaired hand function. Upper limb dysfunction in activities of daily living is greater than in stroke, as both sides are often affected [

4]. In neurological diseases, impairment of the upper limbs may result from various causes. In neuromuscular diseases such as spinal muscular atrophy, there are also disorders of the upper limbs resulting from muscle weakness [

9]. The above examples are selected neurological diseases causing impairment of the upper limb, but there are more [

2,

4,

10]

One of the tools significantly supporting the physiotherapy process, considering medical staff shortages, is robots [

11]. The ones used in the home environment must be placed at the forefront of many challenges, including safety, cost, environmental requirements, and use-independent behavior [

12]. Many patients need constant continuous therapy at home after returning from the hospital, which can bring additional benefits. Post-stroke individuals feel comfortable in a home environment (it is an environment closer to them, familiar, closer to family and friends). Providing home therapy results in a lower likelihood of the patient’s re-hospitalization, which relieves the burden on the healthcare system. Home rehabilitation removes access barriers for people who have problems with mobility and travel; in addition, it allows work during pandemic conditions when restrictions on physical contact are imposed, especially proven here are robots for home rehabilitation. Home rehabilitation requires a high degree of repetition of the activities that are taught to be effective. Automated therapy sessions can enable increased repetitions of rehabilitation exercises without the need to intensify in-person visits while providing patients with engaging and goal-oriented activities to support the therapy process.[

7]

Rehabilitation robots are either end-effector type or exoskeletons [

13]. The former enable only point interaction between the device and a human. However, it makes use of such robots more universal and easier in terms of safety [

13]. On the contrary, the latter provides more complex interaction, including mobilization of particular joints [

14,

15]. However, it is significantly susceptible to mechanical differences between the exoskeleton’s kinematics chain and the anatomy of an individual user. Due to the advantages of controlling every degree of freedom precisely by exoskeletons, these structures can be particularly useful for telerehabilitation [

12,

16].

As at least partially wearable structures, exoskeletons benefit from lightweight construction [

11,

17]. To achieve the lowest mass possible while preserving the right durability and strength, optimization methods are utilized during the design process.

One of the commonly used methods is Parametric Optimization (PO). It requires defying all possible parameters and their range and is often quite complicated to perform. However, it allows for a more thorough overview of the process and leaves more decisions to the user. The PO process is commonly reinforced by the Sensitivity Analysis (SA) and the Response Surface Method (RSM) to help in reducing the overall time of the optimization [

18].

SA is a method used to determine how changes in each output of a mathematical model or function are affected by changes in each input [

19]. It’s a common practice to use it for determining the most suitable parameter configuration and reducing the number of input parameters, hence reducing the overall time of the whole optimization process.

Another tool used to optimize designs is Topology Optimization (TO) [

20]. It is a mathematical method that spatially optimizes the distribution of material within a defined domain while maintaining previously set constraints and looking for a minimal value of the predefined objective function [

21]. It is used in the structural optimization of various parts, from mechanical parts such as gears or wheels to smaller, more precise objects such as ferrite plates [

22]. The method was used in the literature to optimize rehabilitation exoskeletons [

23]. Such an approach may utilize different methods like Solid Isotropic Material with Penalization (SIMP) method [

24], evolutionary structural optimization (ESO)[

25], genetic algorithms [

26], or others. The SIMP method is based on the Finite Element Method (FEM) analysis and is commonly applied in stress and structure durability research [

24].

The presented methods are based on different approaches but can be used for the same aim. They are also applicable to additively manufactured components [

27]. Moreover, they can be used sequentially to obtain even higher mass reduction [

28]. For this reason, the paper focuses on combining PO and TO techniques for a specific application in rehabilitation exoskeleton design, as an example of a series robot.

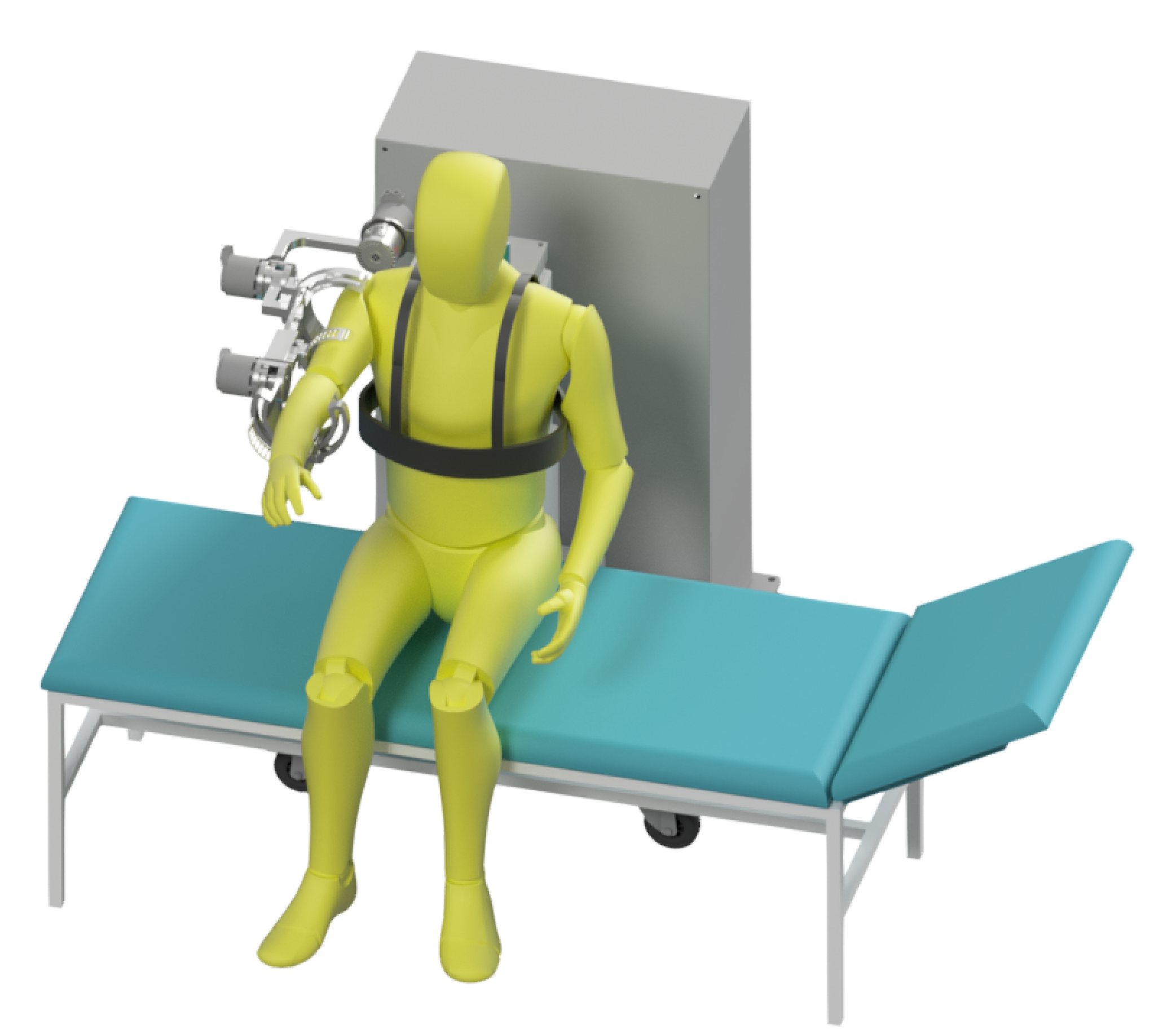

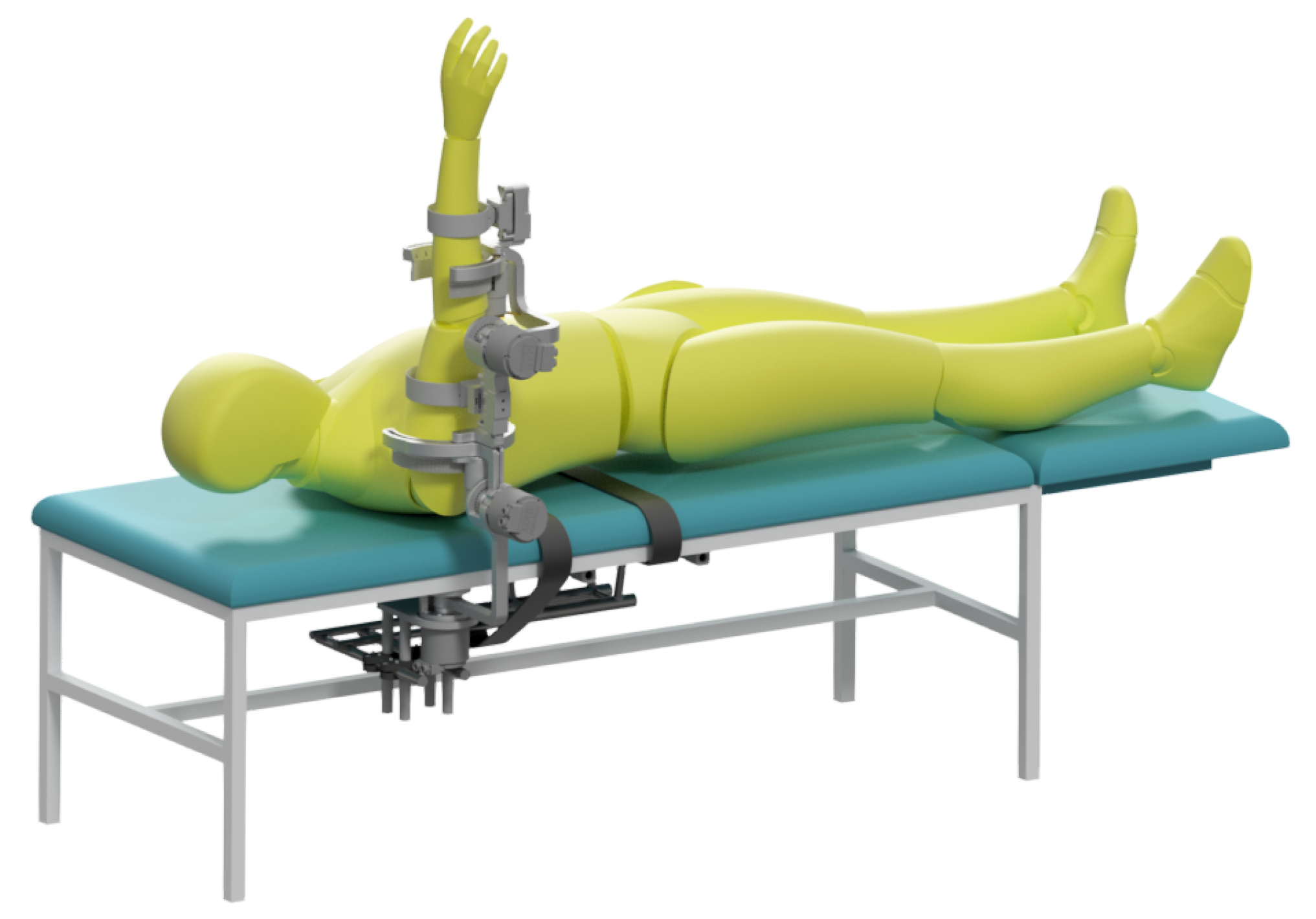

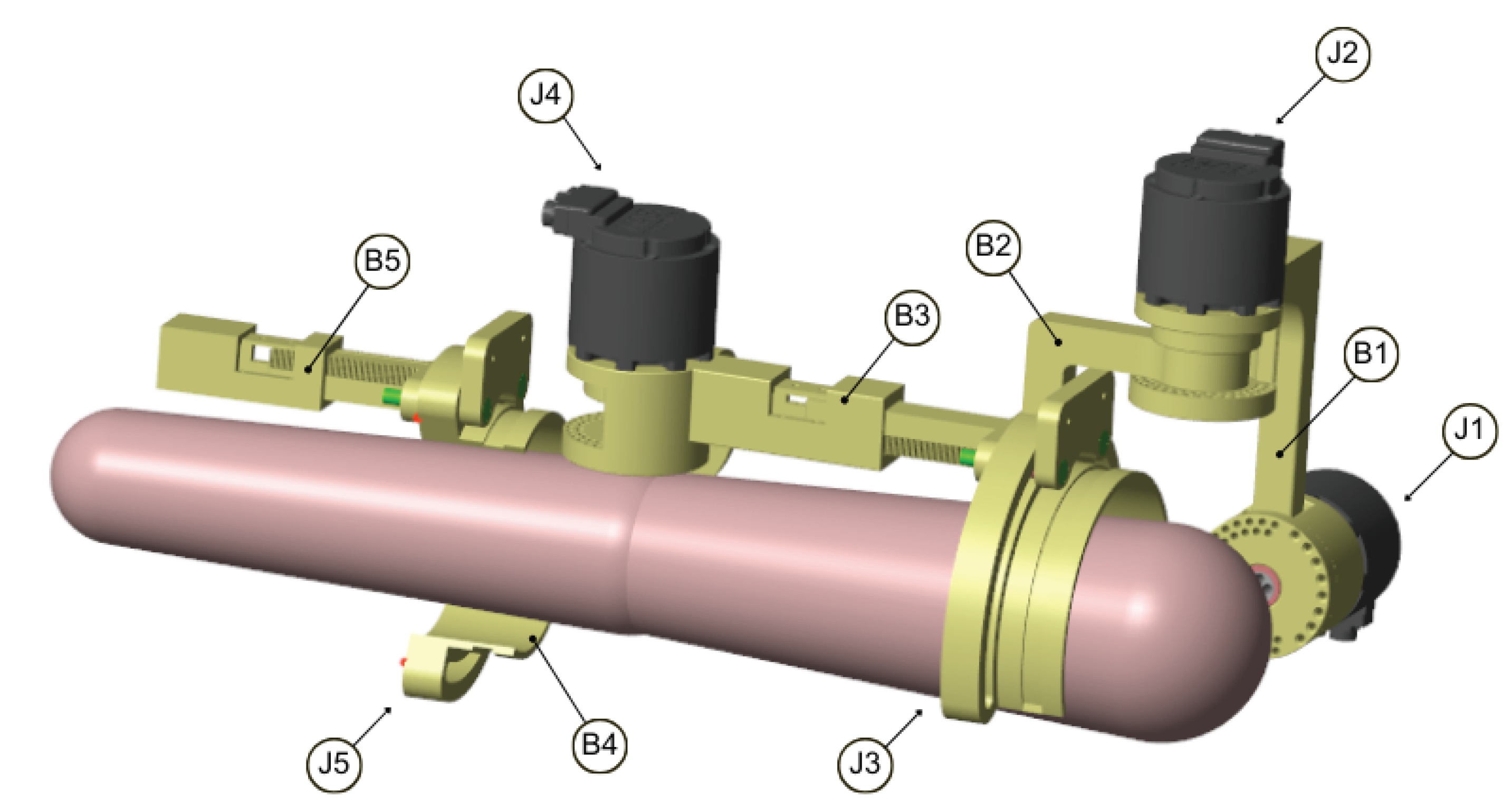

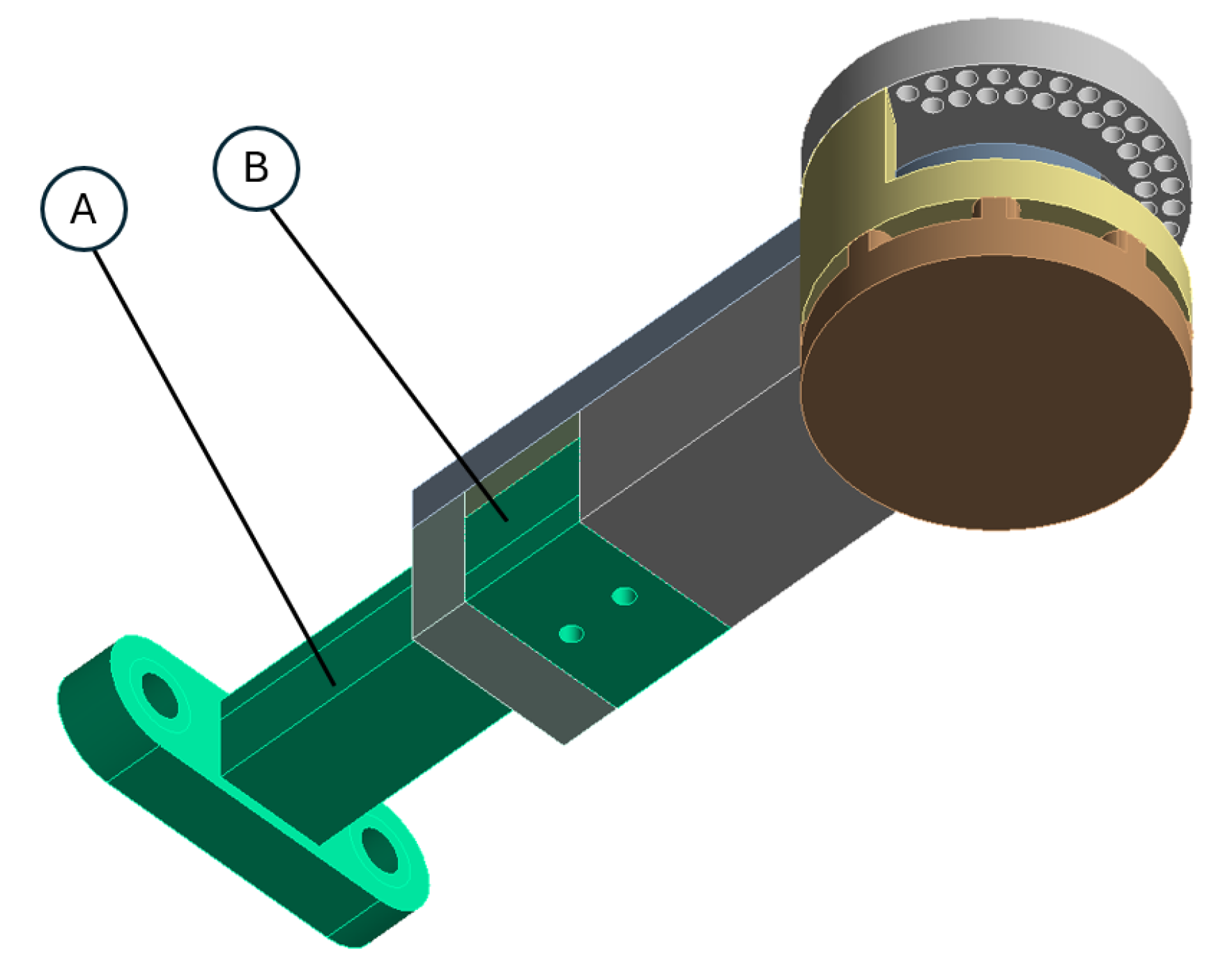

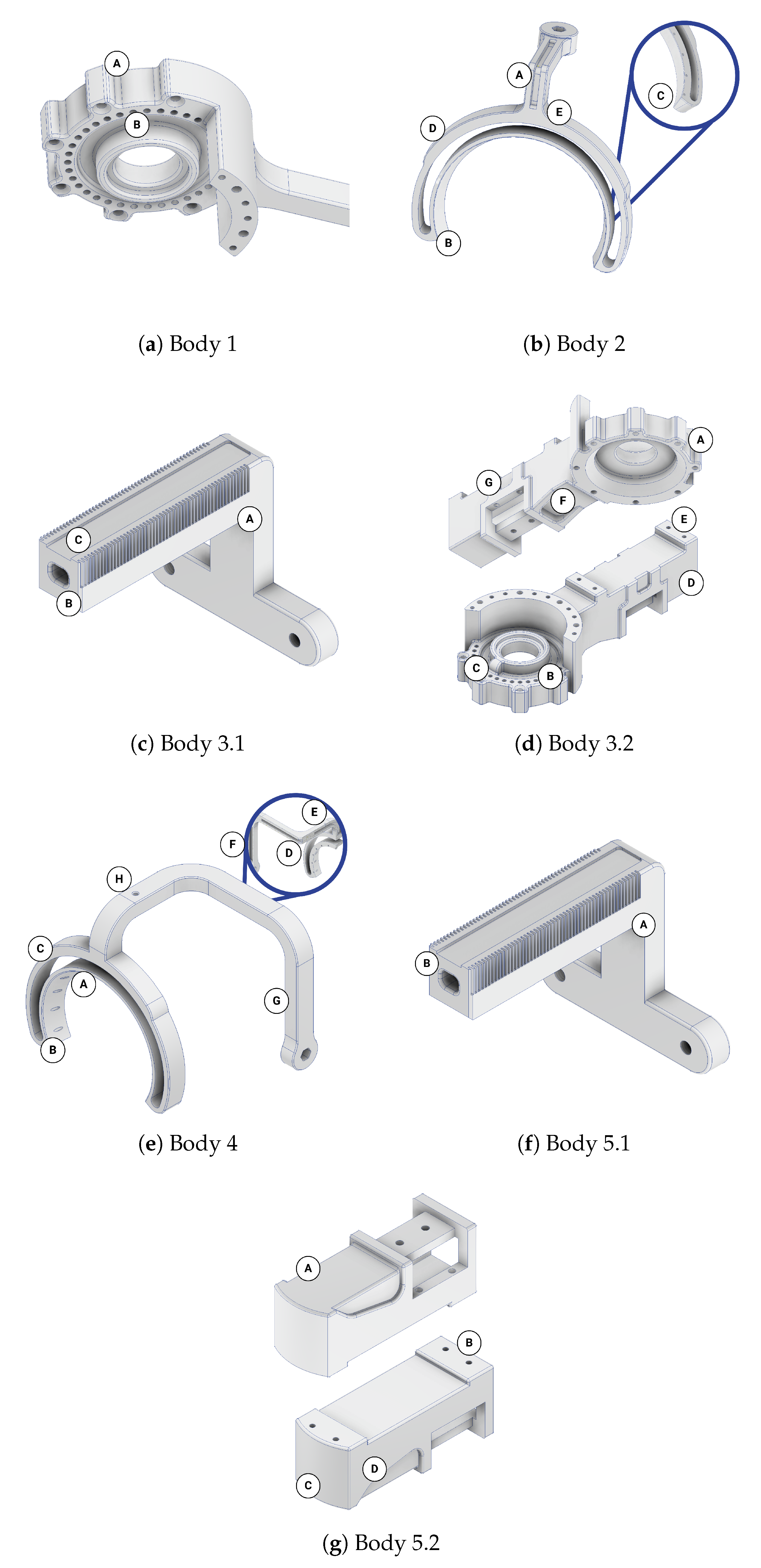

The exoskeleton, which is an object of optimization in this paper, is

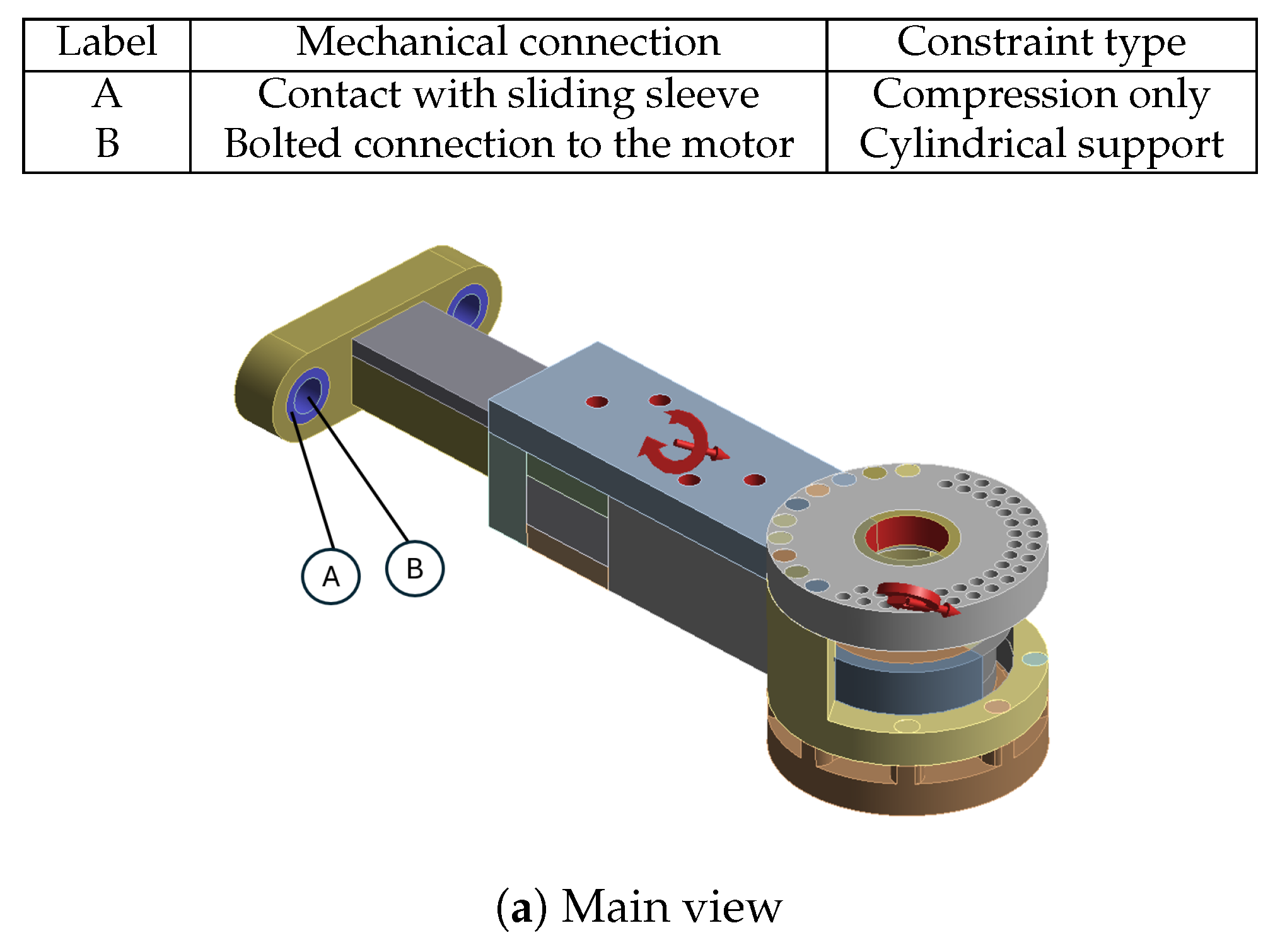

SmartEx-Home, the device for task-oriented kinesiotherapy of the upper extremity. It can be attached to a chair or a bed or used on a dedicated frame with a lifting column. Therefore, physiotherapy can be performed in a sitting, lying, or standing position (see

Figure A1–

Figure A3). The device enables motion in five degrees of freedom of the shoulder and elbow joints. Therefore, it is suitable for task-oriented exercises. Shoulder abduction/adduction and flexion/extension, as well as elbow flexion/extension, are driven by electric motors. On the contrary, shoulder and ulnar-radial rotations correspond to the passive joints of the exoskeleton. The construction is adjustable to the lengths of arm and forearm segments corresponding to the Polish population from 5

th women to 95

th men percentile [

29]. Therefore, all of the joints rotation axes can be aligned with the modeled rotation axes of human joints. The main segments are attached to the arm and forearm through 3-axis force sensors with elastic braces. Patients can also be placed for exercise with wheelchair belts. Exercises with the device are performed in either passive or active mode. Their trajectories correspond to the activities of daily living modeled and recorded at the previous stage by physiotherapists [

30]. The visual of the exoskeleton placed at the chair was presented in

Figure 1.

Based on the analysis of recent research papers regarding designs of rehabilitation devices, combining topology optimization with parametric optimization has not been investigated and applied yet [

16]. Therefore, there is a research gap in the field of optimizing rehabilitation or assistive robots, which have complex loads resulting from human-machine physical interactions and dynamic motions. The focus of the study is to apply the methodology in the field of biorobotics and validate possible mass minimization while modeling reactions with the real-life motion recordings.

The aim of the study is to minimize the mass of the

SmartEx-Home exoskeleton [

30,

31] with the numerical methods. These include combined multibody dynamics simulations and multistep FEM optimization. The process is based on real-life measured motions used in planned robot-aided physiotherapy. Therefore, the optimization process is dedicated to the specific application of the device. Currently, methods that are used tend to involve only a single type of optimization and are based on generalized loads, not specific therapy motions. Therefore, the resultant designs cannot be treated as optimal. The presented methodology will fill this gap. Moreover, this paper will present the complex simulation-based design and discuss the effects obtained at every stage.

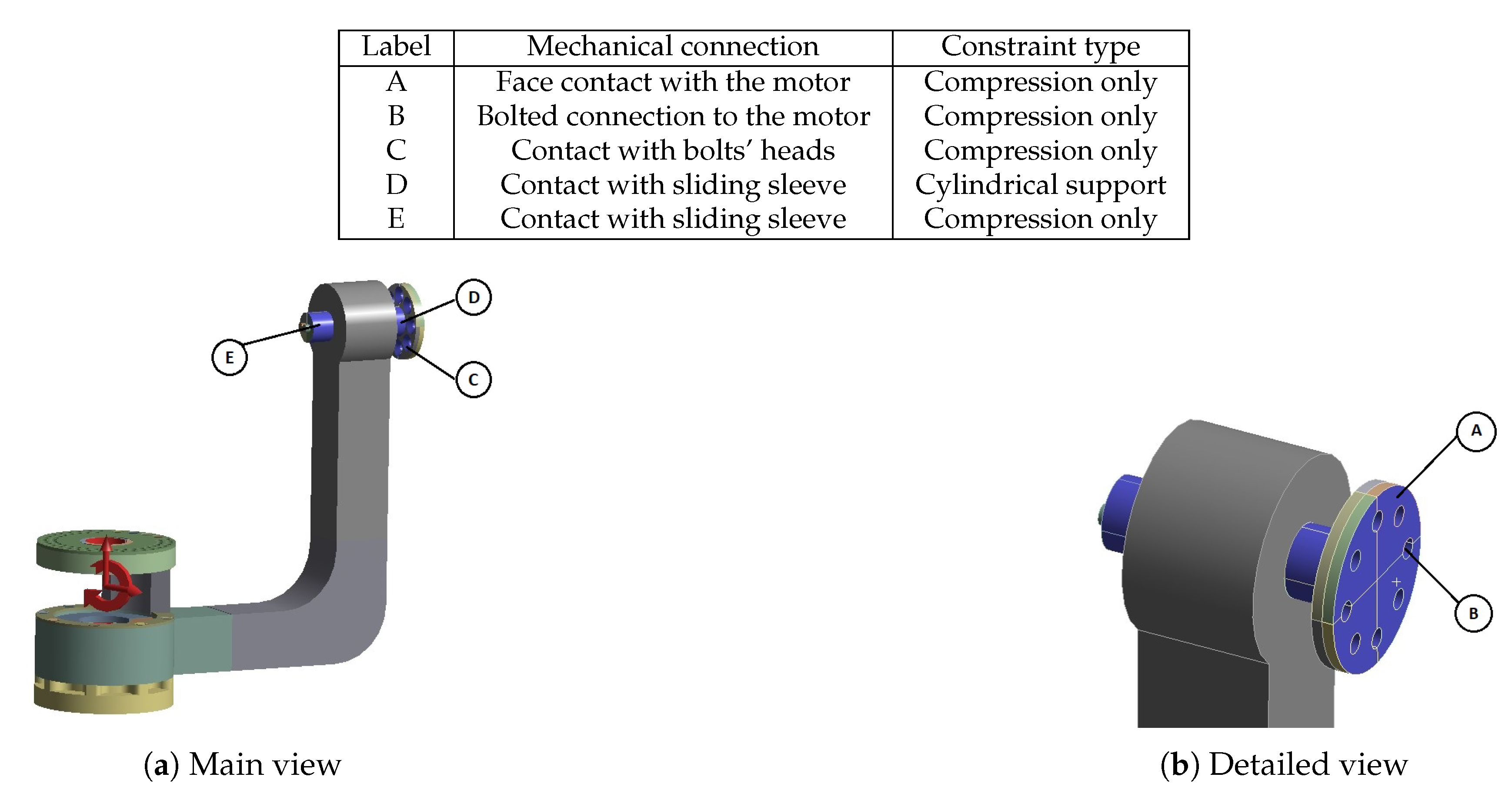

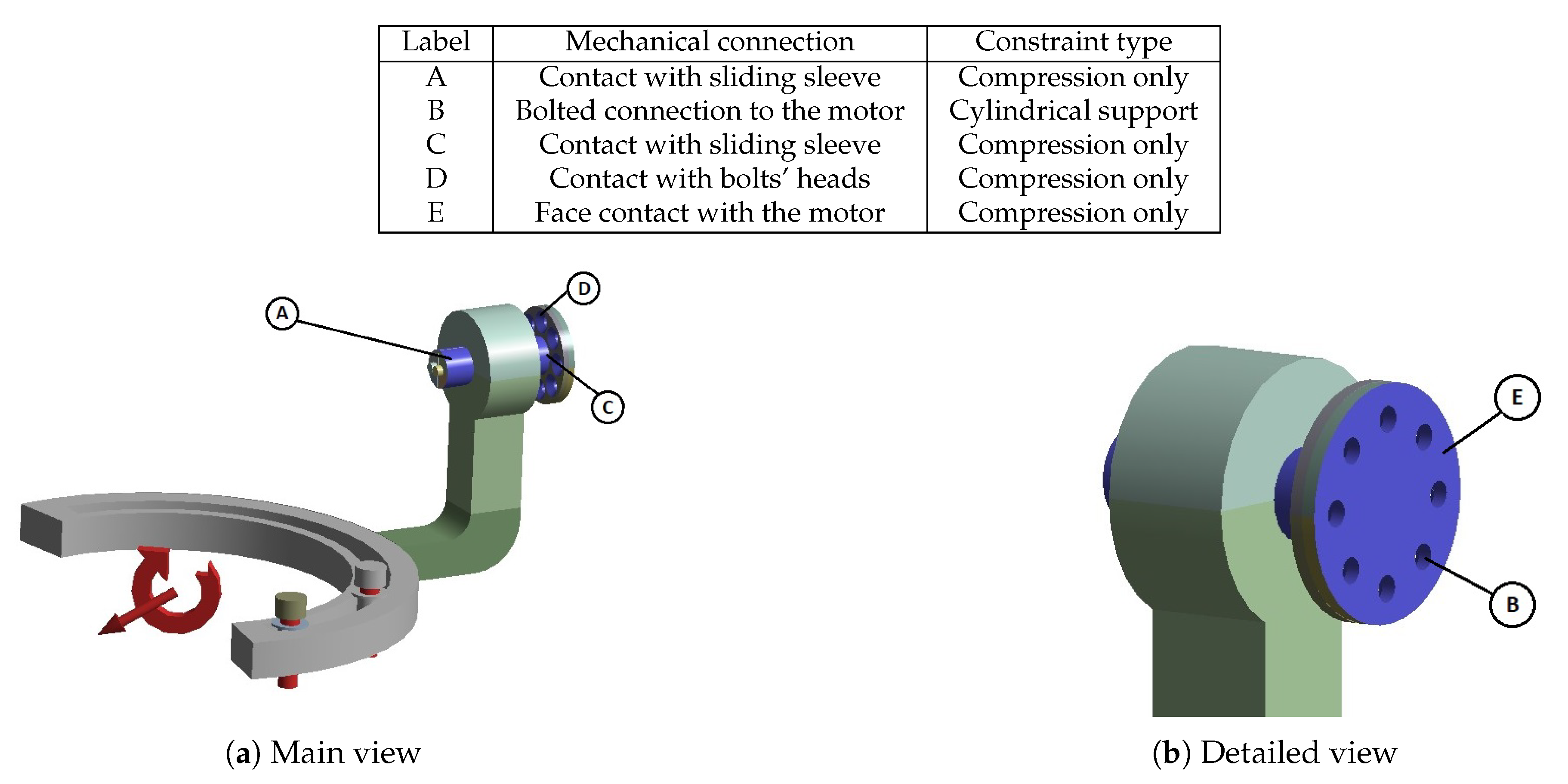

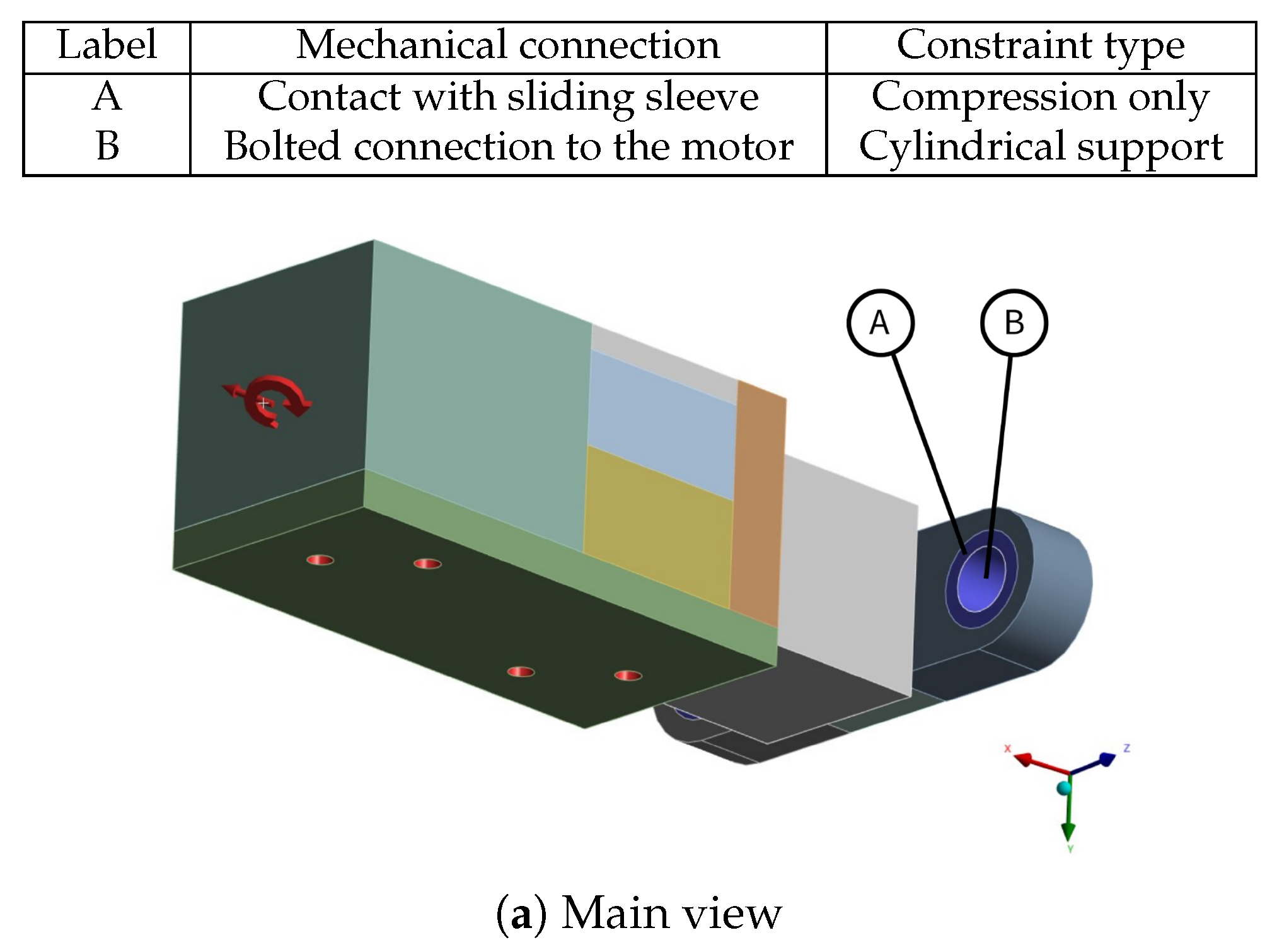

3. Multibody Analysis

The rigid multibody simulation (MBS) model enabled dynamic testing based on recorded motion trajectories, resulting in valuable insights into motors’ torque requirements and internal loads. These supported strength simulations are described in sections 4-6. The model was based on real-life measured trajectories and enabled the simulation of the construction behavior during motion.

Figure 2 shows the MBS model in graphical form within the simulation environment, in its initial configuration - starting each trajectory recording.

The simulation model was primarily developed using the Simulink package, along with Simscape and Simscape Multibody. The exoskeleton bodies used in the simulation were designed in Autodesk Inventor 2021 and integrated with the Simscape Multibody environment. This integration allows for the direct import of 3D models, automatically incorporating physical properties such as density, geometry, and moments of inertia, streamlining the model-building process. Moreover, the modified bodies were automatically updated.

The Robotic System Toolbox was used to generate and adapt polynomial motion trajectories for the simulation based on the recorded discrete real-life trajectories.

Upon completion of the MBS simulation, the recorded trajectories and other resultant data are exported to the Workspace for further analysis, particularly to identify critical structural loads.

3.1. Motion Modeling

Four IMUs from the Movella DOT system were used to record upper extremity motion reflecting activities of daily living (ADLs). Each sensor, recording at 120 Hz, contains a 3-axis gyroscope, accelerometer, and magnetometer, with orientation data delivered as ZYX Euler angles. While most analyzed ADLs primarily involved the upper limb with minimal body motion, one IMU was placed on the trunk to account for natural position changes. Sensors were also placed on the arm and forearm to track these segments’ movements. A fourth IMU was attached to the palm, which was crucial in measuring forearm supination and pronation. This IMU also enabled the recording of wrist motion across two degrees of freedom (radial/ulnar deviation and flexion/extension), which allows for precise modeling of the distal characteristic point of an exoskeleton. The attachment scheme is presented in the complementary paper [

30].

To ensure consistency, data were recorded following a standardized procedure [

30]: (1) performing a heading reset, (2) holding the extremity in a neutral position, (3) conducting ten repetitions of the activity, and (4) transferring the data. Besides aligning the axes of the IMUs in the same direction, the heading reset minimizes issues with proper recognition of the axes. The initialization phase requires the subject to maintain a neutral position for at least 5 seconds.

Each session included ten repetitions per activity and was completed within five minutes to minimize sensor drift. The recorded data was then transferred from the Movella DOT sensors to mobile storage and stored in a database. A total of 38 recordings, representing 19 ADLs from two subjects (physiotherapists), were selected for further multibody analysis. They were repeating the motions multiple times each with the different motion patterns. These ADLs are in-depth described in the complementary paper [

30]. Further experiments with multiple participants confirmed that the motions included in this investigation cover a wide range of potential motions of users.

The stored data were further processed with proprietary scripted software in

MATLAB 2024a. This resulted in the time series for rotations in the MBS model’s joints. This procedure consisted of the following steps: (1) loading data and removing measurement value range limits, (2) computing the initial orientations of the IMUs, (3) assuming default orientation of the body segments’ frames, (4) computing the motion of the body segments’ frames, (5) computing the rotation history in the joints, extensively described in a complementary research paper from the series [

30].

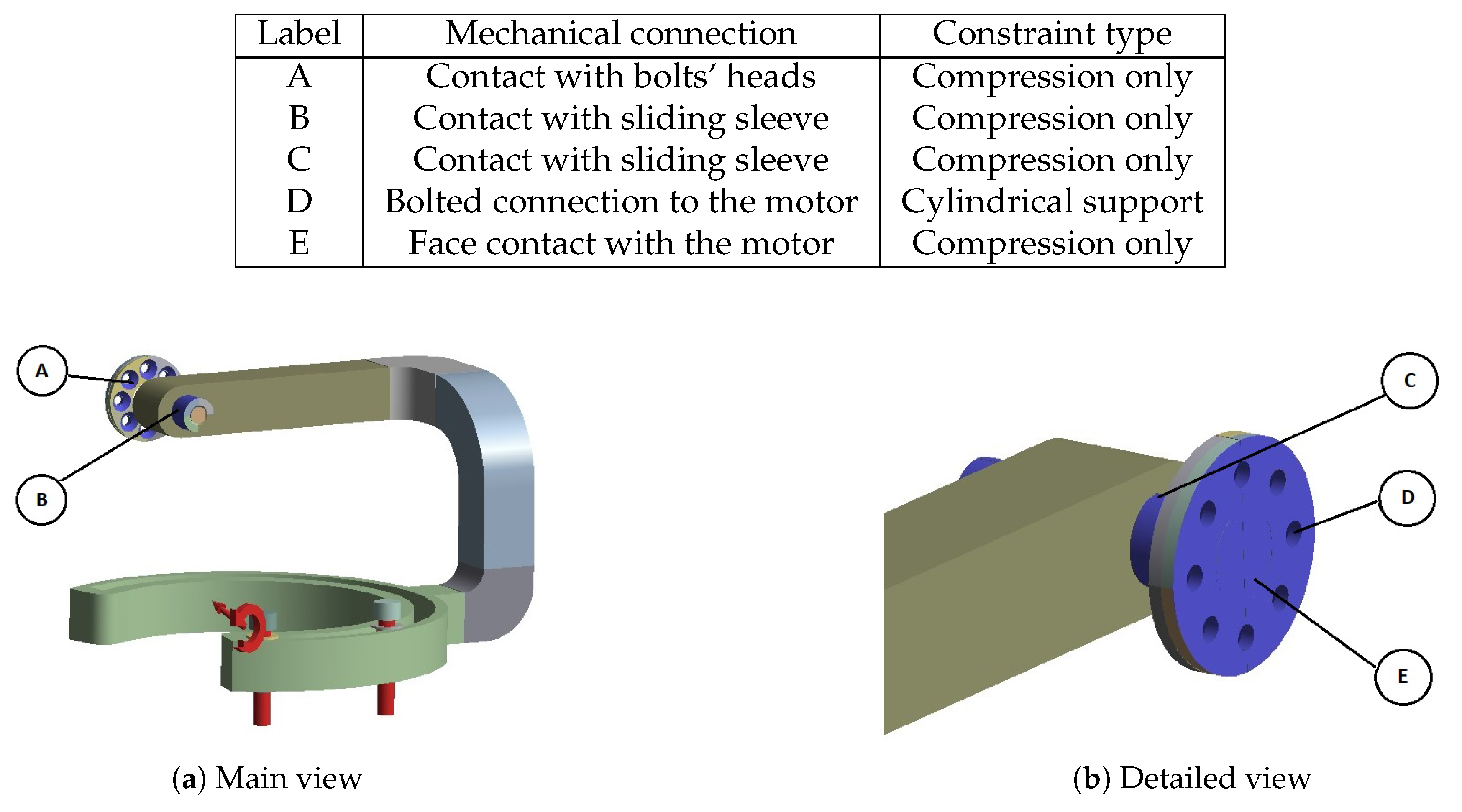

3.2. Model Construction

This subsection is dedicated to the model description, precisely described in a complementary research paper from the series [

31].

The input values consist of angular trajectories at the following joints of the structure, defining the planned motion of the system. The output values provide critical insights into the system’s performance and include:

Required drive torques required in the active degrees of freedom to achieve the desired motion.

Mechanical loads acting on individual components, represented as force and moment vectors reflecting real-life conditions.

The environment has been configured to reflect real-world conditions, such as the gravitational field. A common global reference frame has been established.

The solid subbodies were represented by "File Solid" blocks, which import geometry, material properties, and visuals from files modeled in Autodesk Inventor 2021. However, a manual definition of mechanical parameters was also possible. The position of individual mechanical parts in the model was manipulated using "Rigid Transform" blocks, which defined a fixed 3D transformation between two frames of reference.

Rotational degrees of freedom between frames of reference were implemented using Revolute Joint blocks. The stiffness and damping coefficients of the internal spring-damper force law were experimentally chosen to ensure realistic motion, accounting for inaccuracies and energy losses due to friction.

Linear adjustments were implemented with the Prismatic Joint block. These enabled transformation along the Z-axis of the base coordinate system. The Welded Joint block was used to restrict movement while providing access to reaction load data, permanently linking the base and following frames of reference. The fixed joint’s mounting point corresponded to the actual attachment location of the upper extremity to the structure.

As a part of the project, a pin curve slot mechanism was simulated to accurately determine and measure loads in the free (passive) degrees of freedom. Since none of the available blocks was suitable for simulating passive joints, the mechanism was modeled by applying motion constraints and using a 6-DOF joint. Thanks to this, a required angular trajectory was set.

Rotational degrees of freedom and pin curve slot joints were configured to export the required data during the simulation. For each active DOF, motor torque, and constraint forces and torques were recorded as outputs. In passive joints, constraint forces and torques on each shaft were also recorded. Within the simulation, maximum torques needed for the motions were considered (as for passive therapy).

3.3. Selection of Critical Cases

The selection of critical force sets was used in further stages of the project for structural analysis and optimization. The selection was simplified - critical sets were selected based solely on force and torque magnitudes without considering strain or stress values. Consequently, an appropriate safety factor must be applied to ensure the assumptions’ validity, even in cases where the applied force set could generate higher stresses than those selected as critical.

The analysis consists of independently reviewing the reaction (force and torque) trajectories in the joints for each segment and selecting the critical set of reactions. The critical set for one segment may originate from a different recording than that for another segment. The procedure is divided into the following five steps, as described.

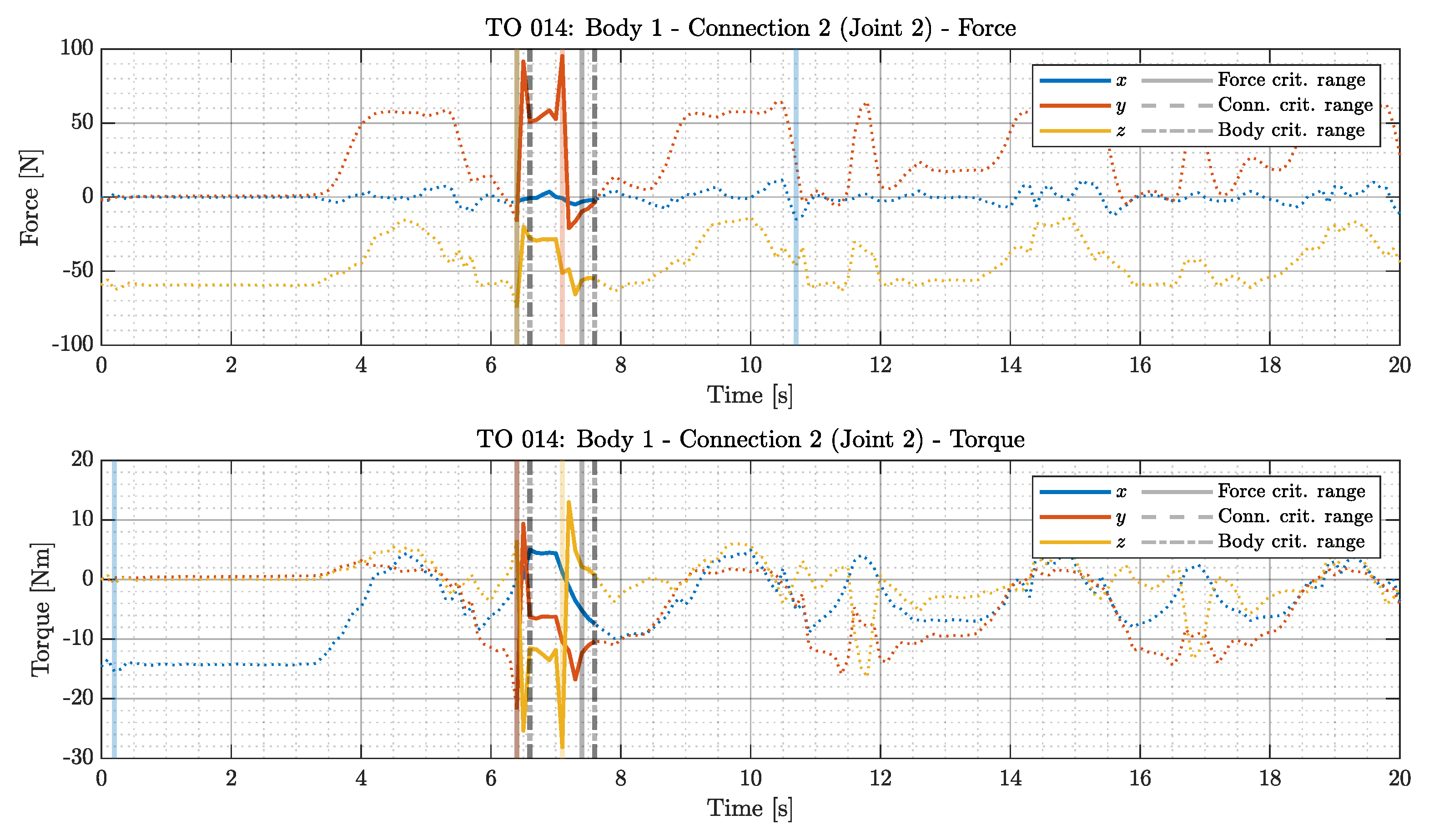

The first step involves identifying the maximum component values of forces in joints. Absolute maximum values of vector components in the coordinate systems related to definitions of joints in the multibody model are recorded. These maxima are marked on an exemplary plot (

Figure 3) with vertical solid lines color-coded according to the respective component (blue for x, red for y, and orange for z).

The next step is determining each joint’s maximum forces and torque norms. Norm profiles are smoothed using a one-second moving average to eliminate artifacts from recordings and spikes generated in simulations. This smoothing allows for identifying a one-second interval where the average force norm reaches the maximum norm. These intervals are selected independently for forces and torques, for different joints and motions, and are marked on the plot with two solid vertical grey lines (

Figure 3).

The selected critical force and torque intervals are normalized to the

range to remove the unit dependency. This facilitates the computation of a new index

according to formula

1, where

represents the normalized, averaged force

, and torque

norm ratio relative to their maximum values (for the

i-th joint in the given body).

The goal is to determine the time interval within which both forces and torques are simultaneously as close as possible to their peaks. This interval is selected for a particular joint and motion combination (marked on the plot with two vertical dashed gray lines in

Figure 3). Ideally, theoretical maximum appear when

. The MATLAB 2024a script assists in identifying these regions, but a final engineering review is necessary to ensure their validity.

The final processing step selects the critical reaction force set for the entire multibody segment. This involves identifying a time interval when force and torque norms across all joints within the body are simultaneously near their maximum values. The computation is performed according to formula

2, where

represents a new non-physical index for the

j-th body, while

n is the number of joints within the body.

The interpretation follows that of

(the identified interval is marked on the plot with a vertical dotted-dashed grey line in

Figure 3). Selecting such an interval ensures that the applied forces are consistent and originate from a single timeframe, making them representative of actual loading conditions.

Forces and torques are selected to yield the highest possible norm values within the proposed interval to ensure a conservative approach. Consequently, the chosen force value may originate from the beginning of the one-second interval, while the torque value may be taken from its end independently for each joint in the body.

The final selection of critical forces and torques involves reviewing average values from the identified intervals (where all joint values come from the same time window) and their corresponding maximum values. Standard deviations were analyzed, and movements with values deviating significantly (more than one standard deviation) were removed. The goal was to find intervals where the mean remained within the upper boundary of a two-standard deviation range and where maximum values were among the highest recorded.

These initially proposed values were further verified by considering intervals for individual joints, forces, and torques separately. The final decision was cross-checked against the force and torque history to eliminate artifacts, measurement errors, or other non-physical simulation results by reviewing the plotted time history of these values. The outcome – selected critical forces and torques for each body – is presented in

Table 2.

7. Discussion

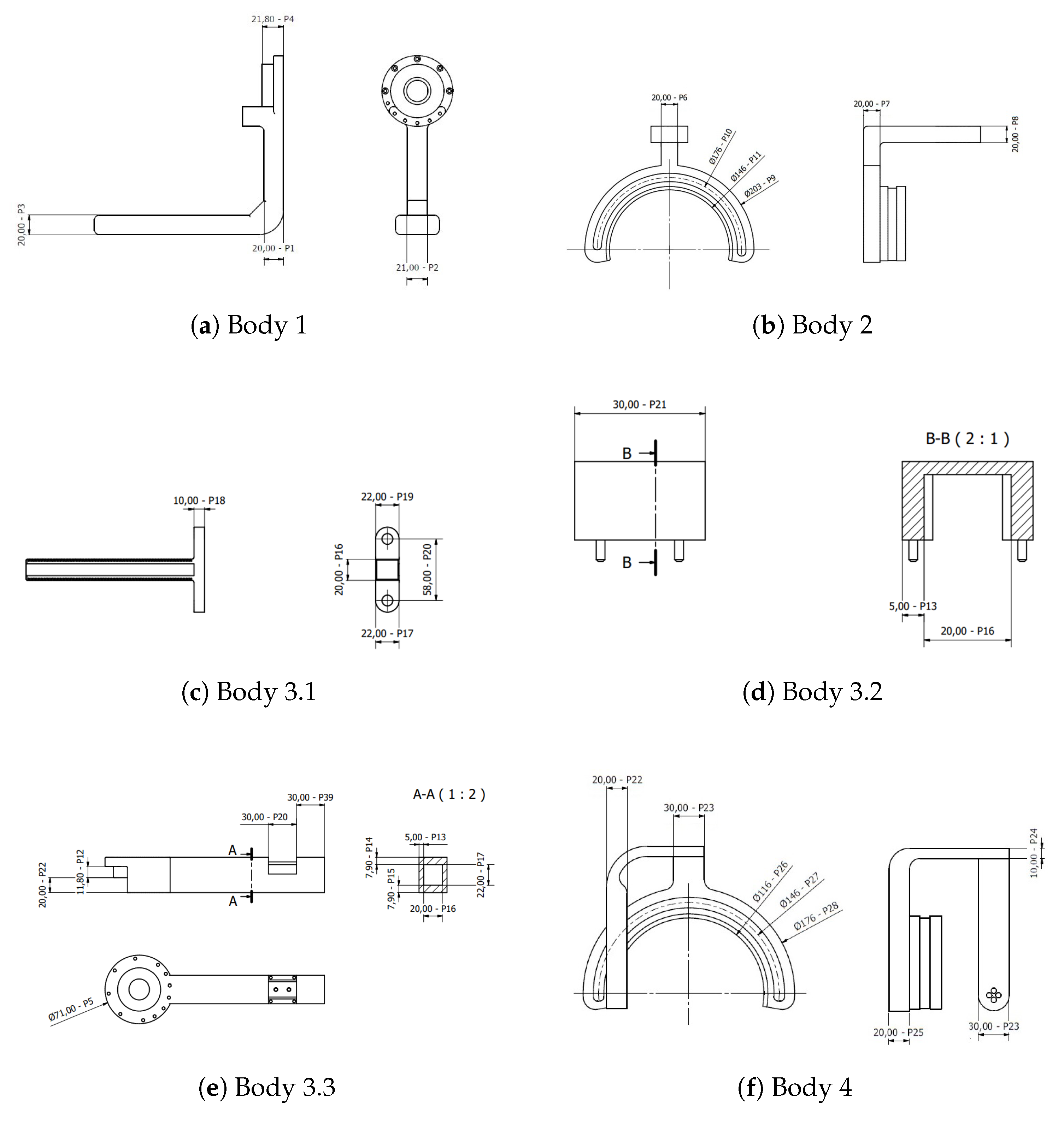

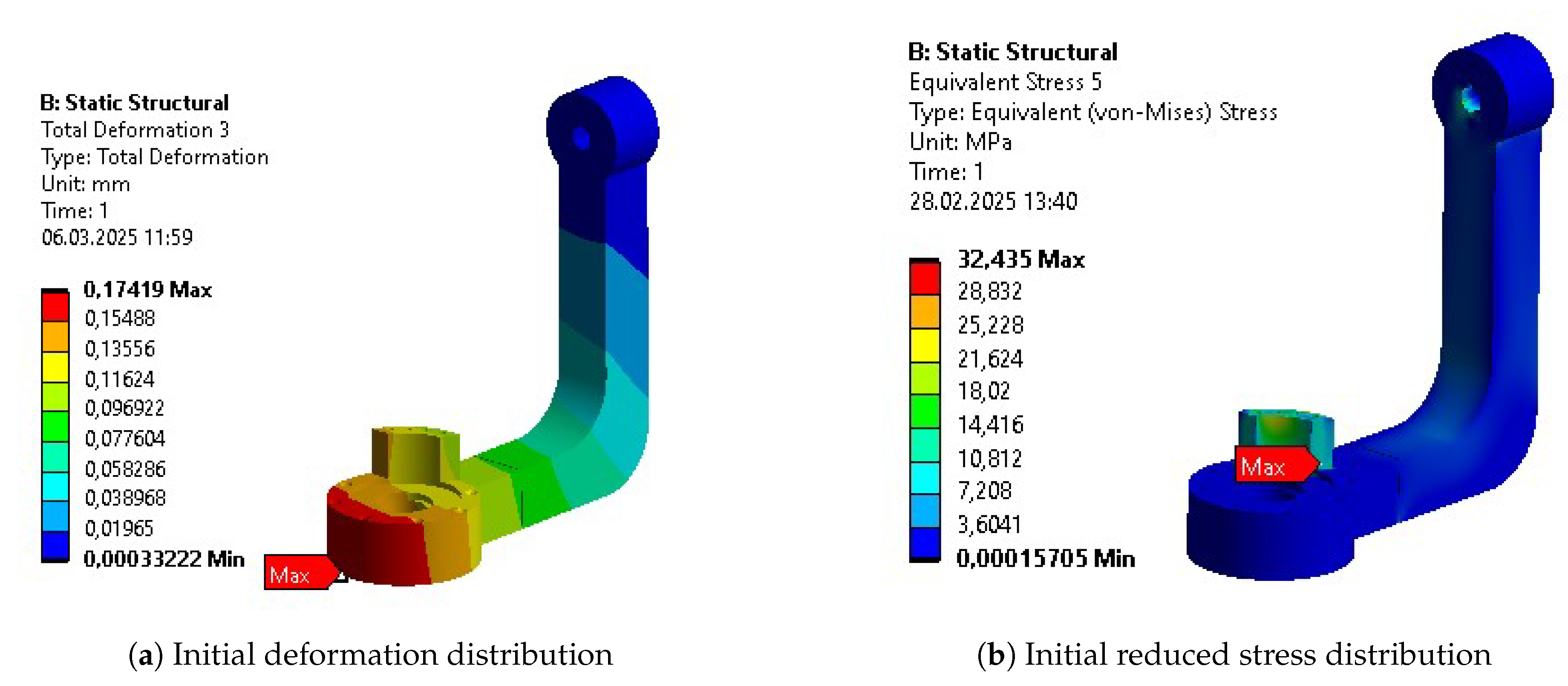

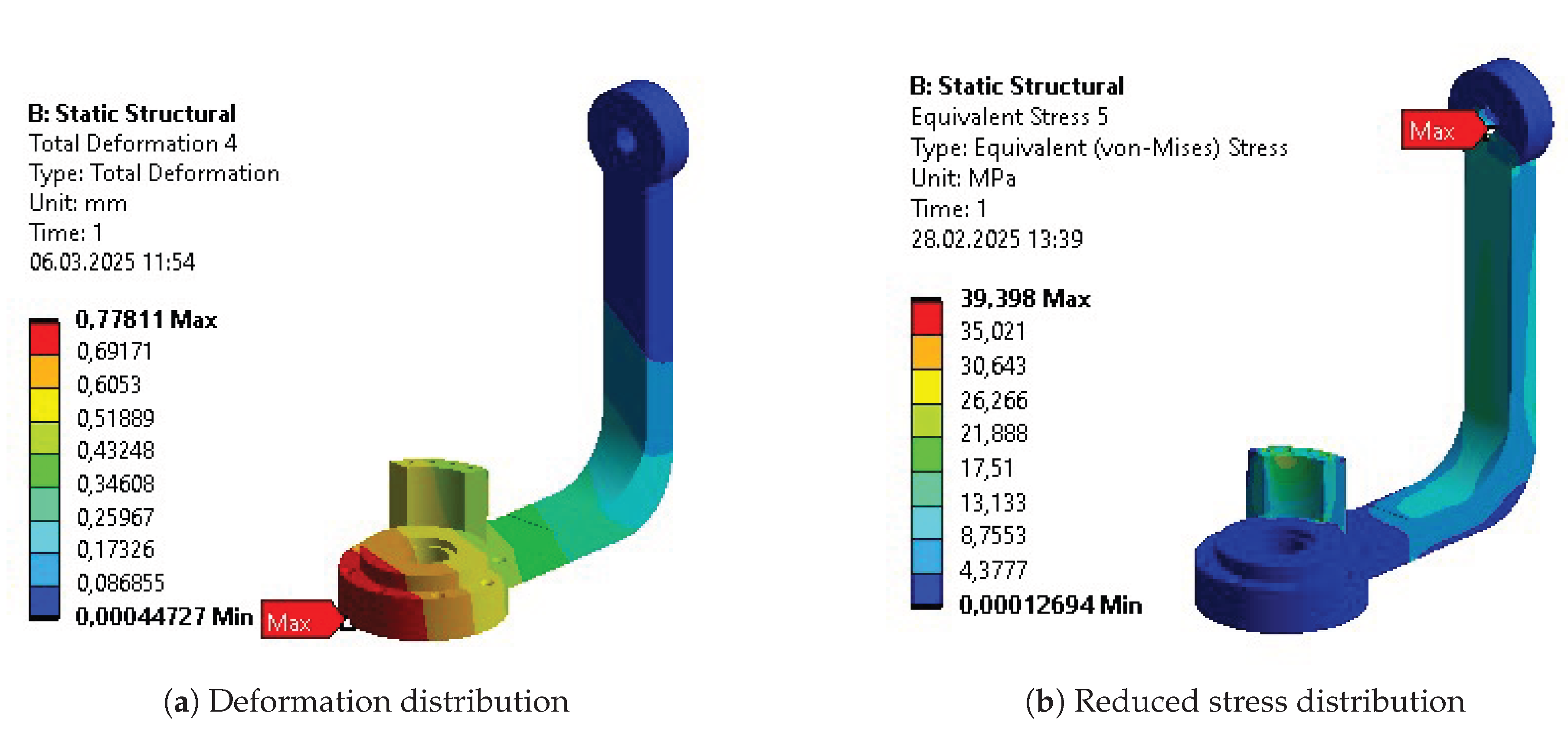

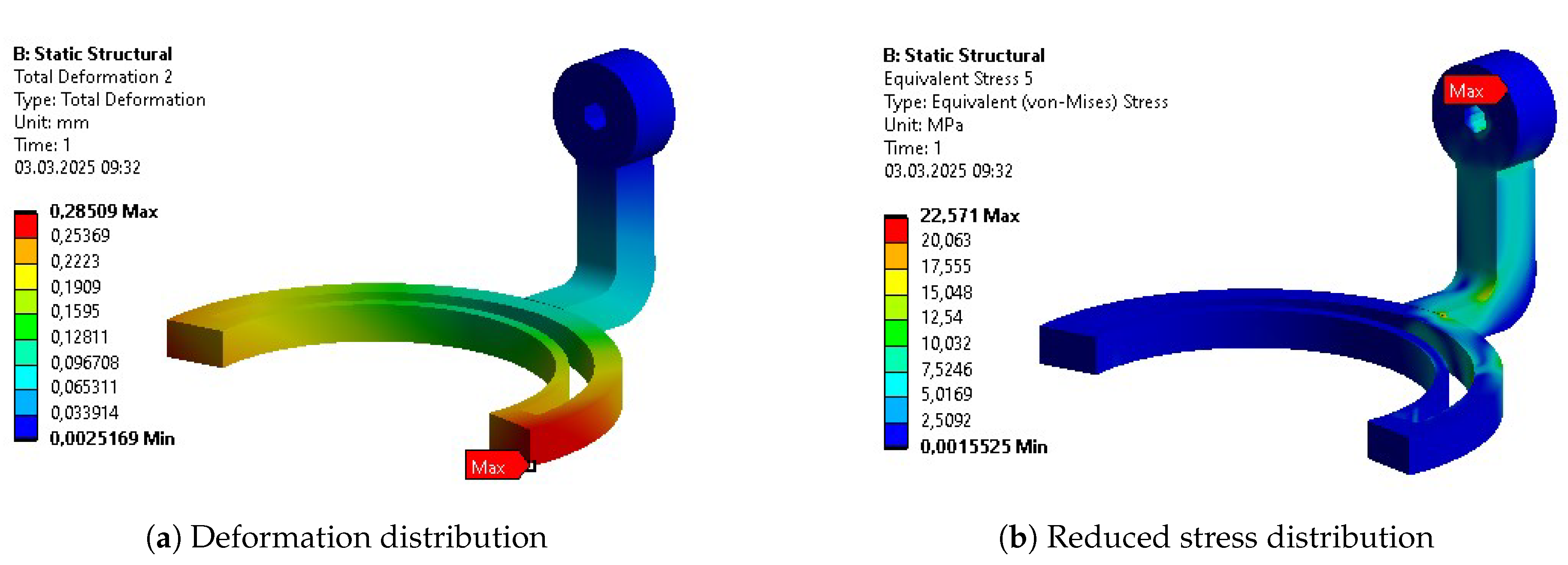

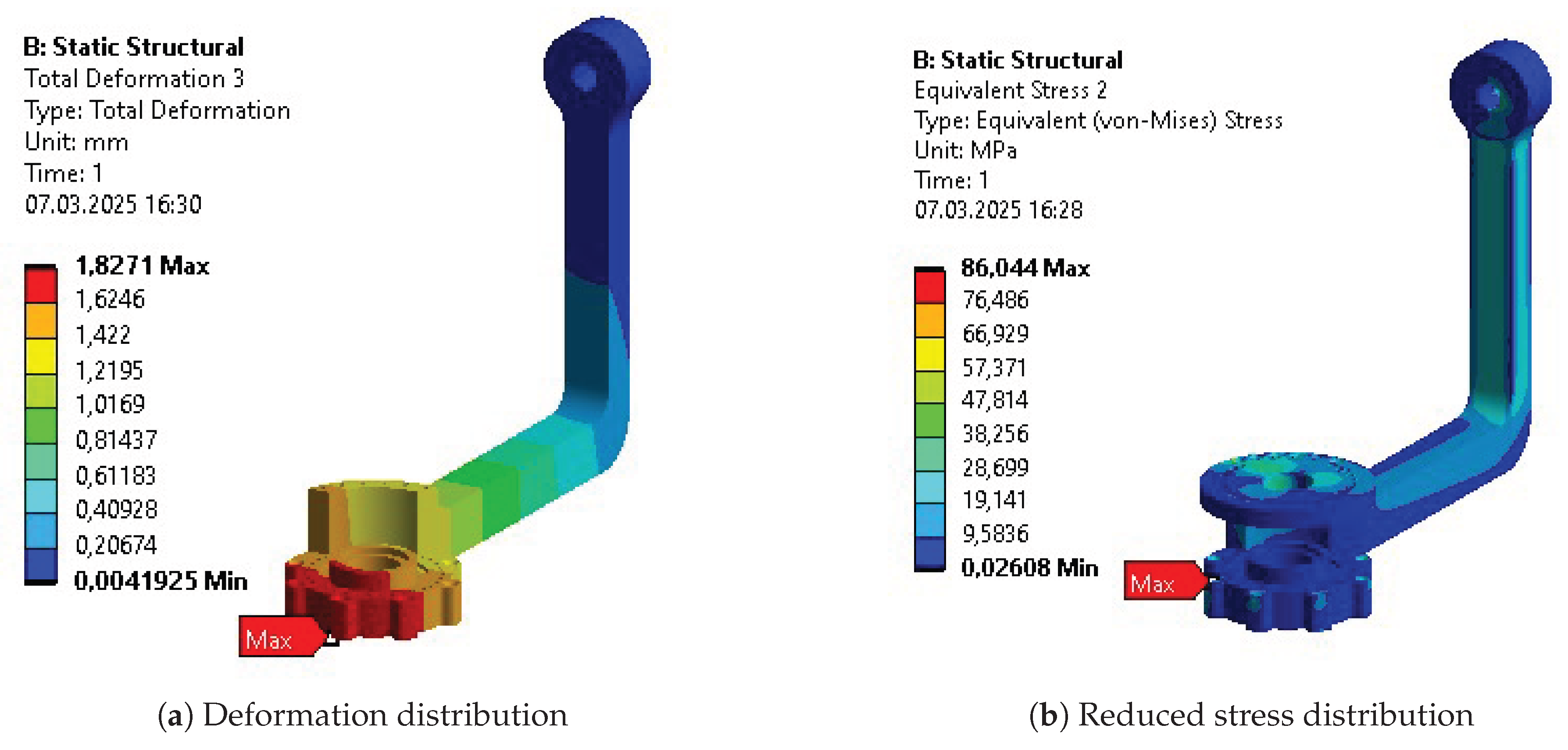

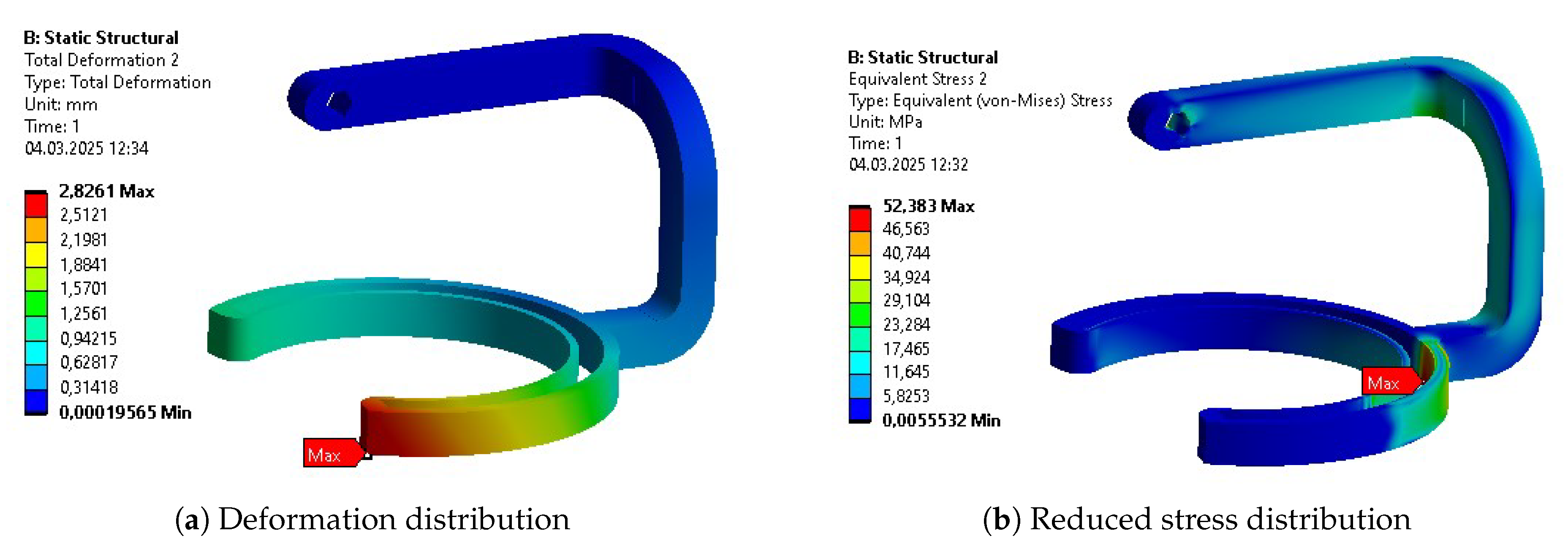

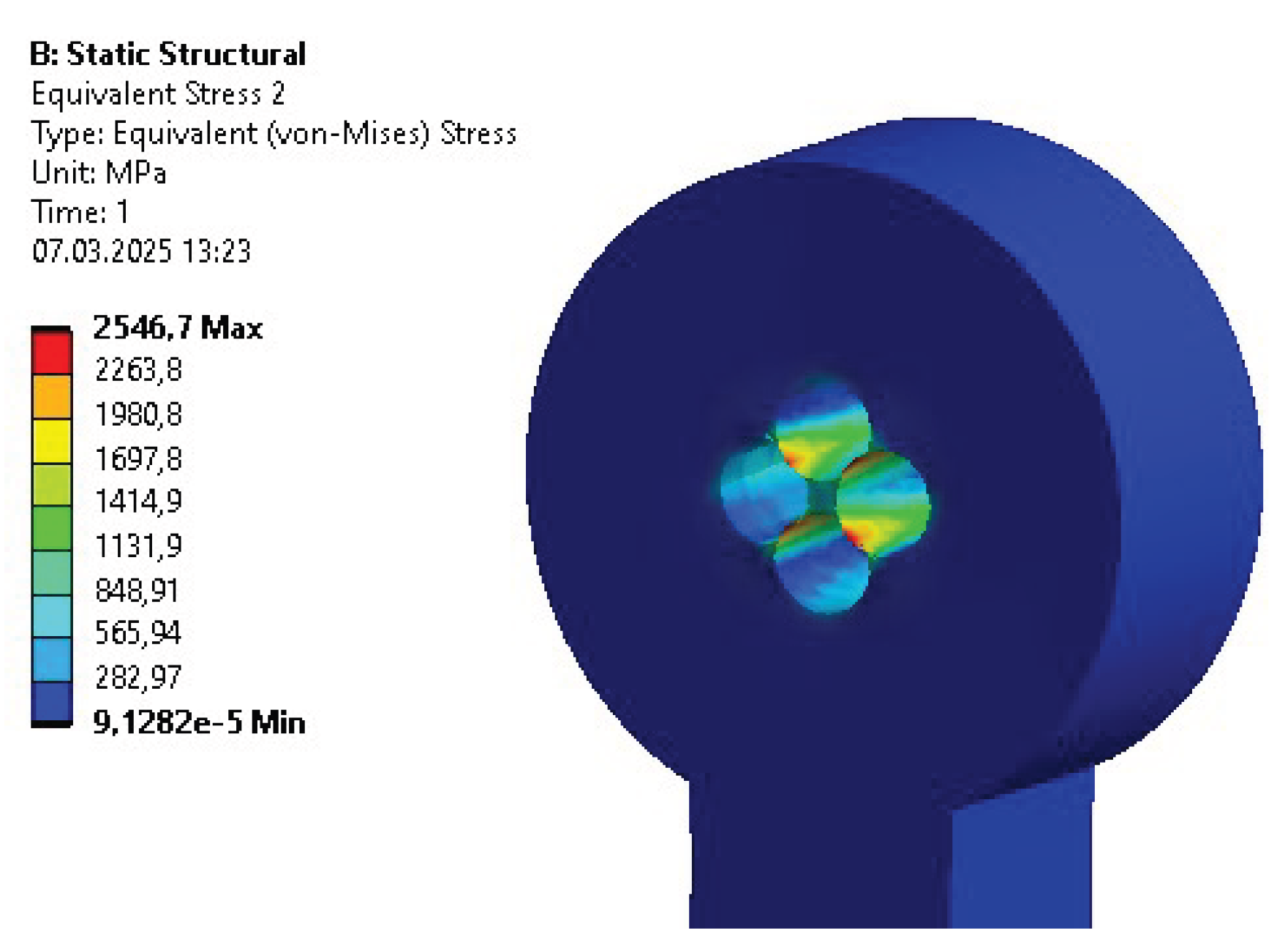

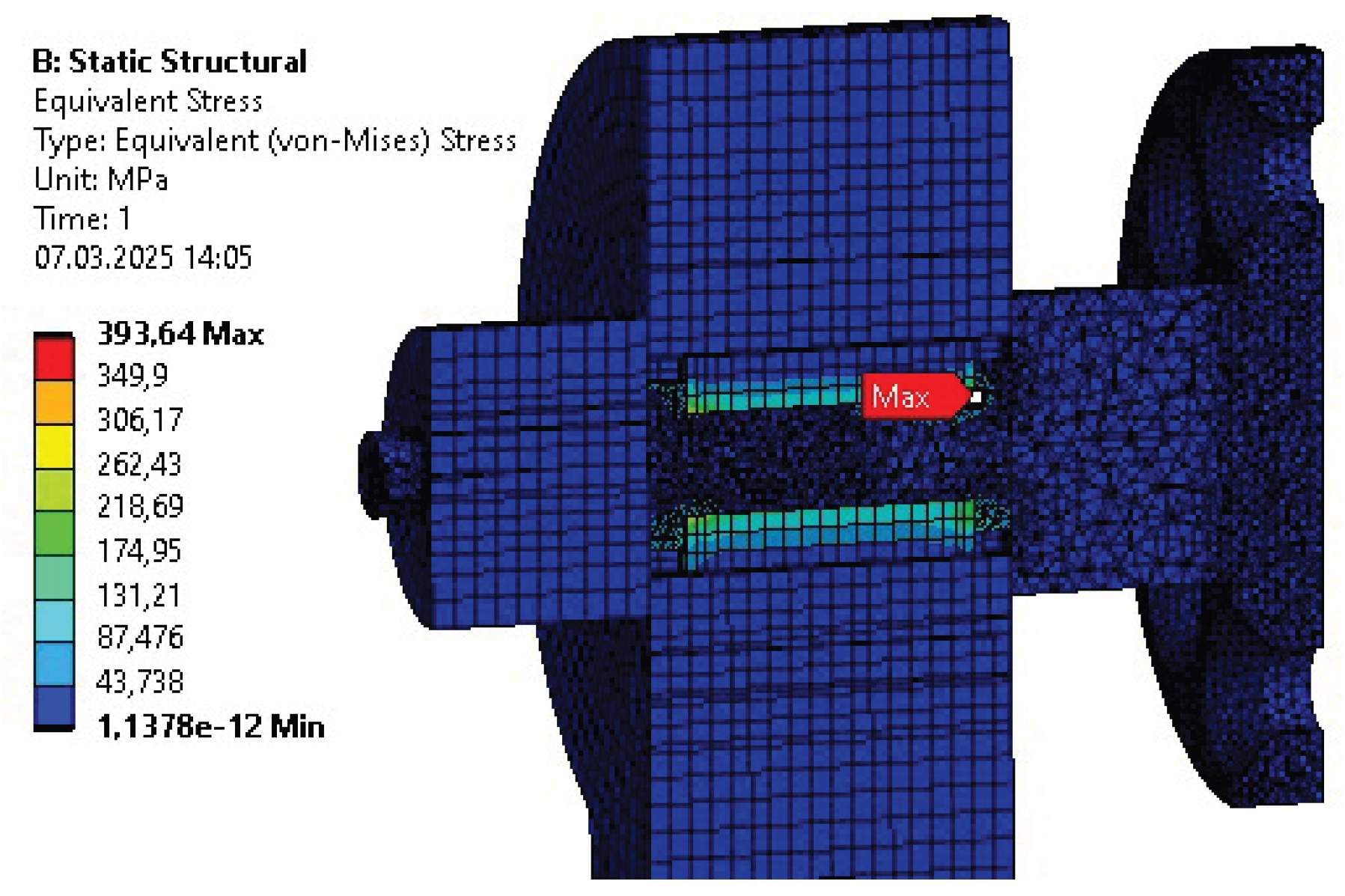

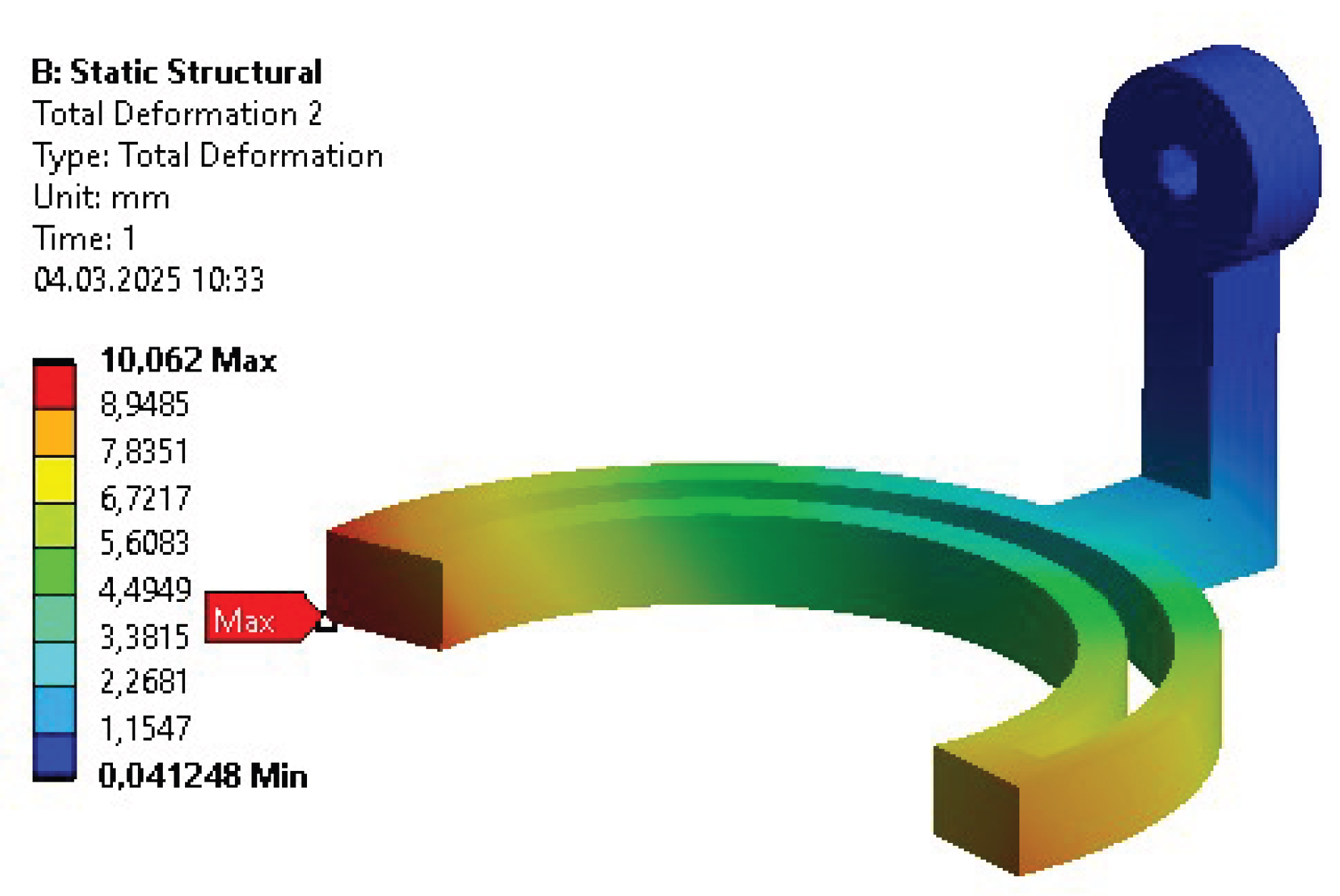

The optimization cycle consisted of three main steps. Within all of them, the optimal result was being find between 199 and 1000 iterations, more correlating to the component’s geometry than the step of optimization. Initial parametric optimization was intended to find the general quasi-optimal dimensions and materials. It resulted in the most significant mass reduction among all of the analyzed bodies. Along with this, it increased the average internal stress, strain, and deformation of the objects. Nevertheless, their values remained significantly below limits for selected materials and even increased a minimal safety factor to 4.94. The following topology optimization targeted changes in the components’ dimensions. Thanks to this, the most loaded regions remained solid, while the material was removed from the others. This brought further mass reduction. Nevertheless, the safety factor still remained above the acceptable 1.3 threshold and got a value of 2.6. The last parametric optimization enabled the final fine mass reduction by adjusting the parameters of new features of the design. The other parameters did not vary significantly, and the final safety factor reached a level of 2.52. The total mass of the design of main constructional bodies decreased by almost 50%, even though the functional modifications increasing the components’ volume were applied before the last parametric optimization. The total mass of the exoskeleton, including motors, mounting components, and sensors was reduced by 29%.

The results are slightly favorable compared to the single-method optimization presented in the literature for similar devices. Studies typically remain a safety factor at the level 1.1-1.33 to reach 28-49% mass reduction of constructional elements [

23,

36,

37]. This includes topology optimization only or parametric lattice optimization. On the contrary, the study that reaches the highest safety level (5.9), important for the medical devices, results in a 43% mass decrease[

38].

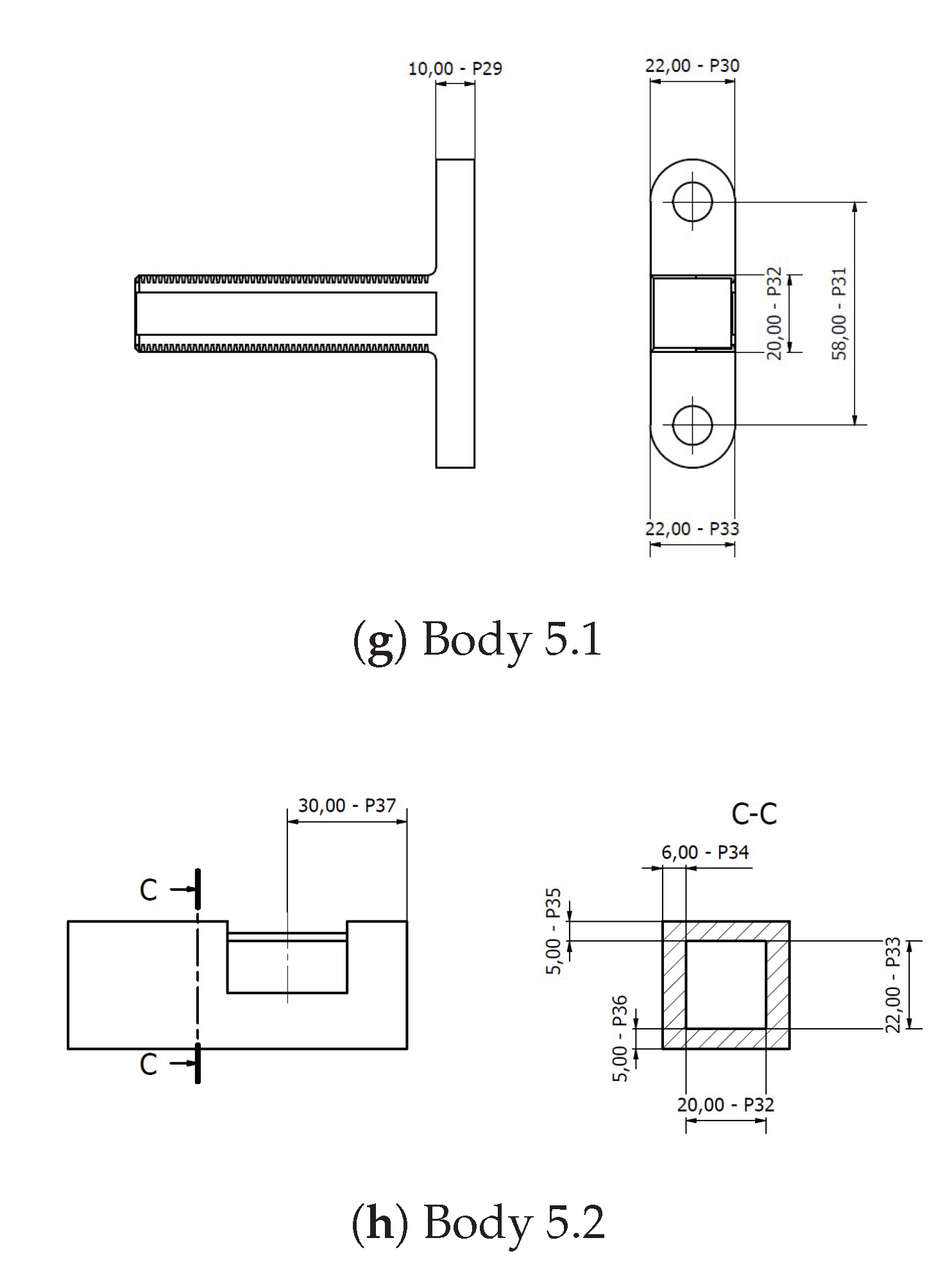

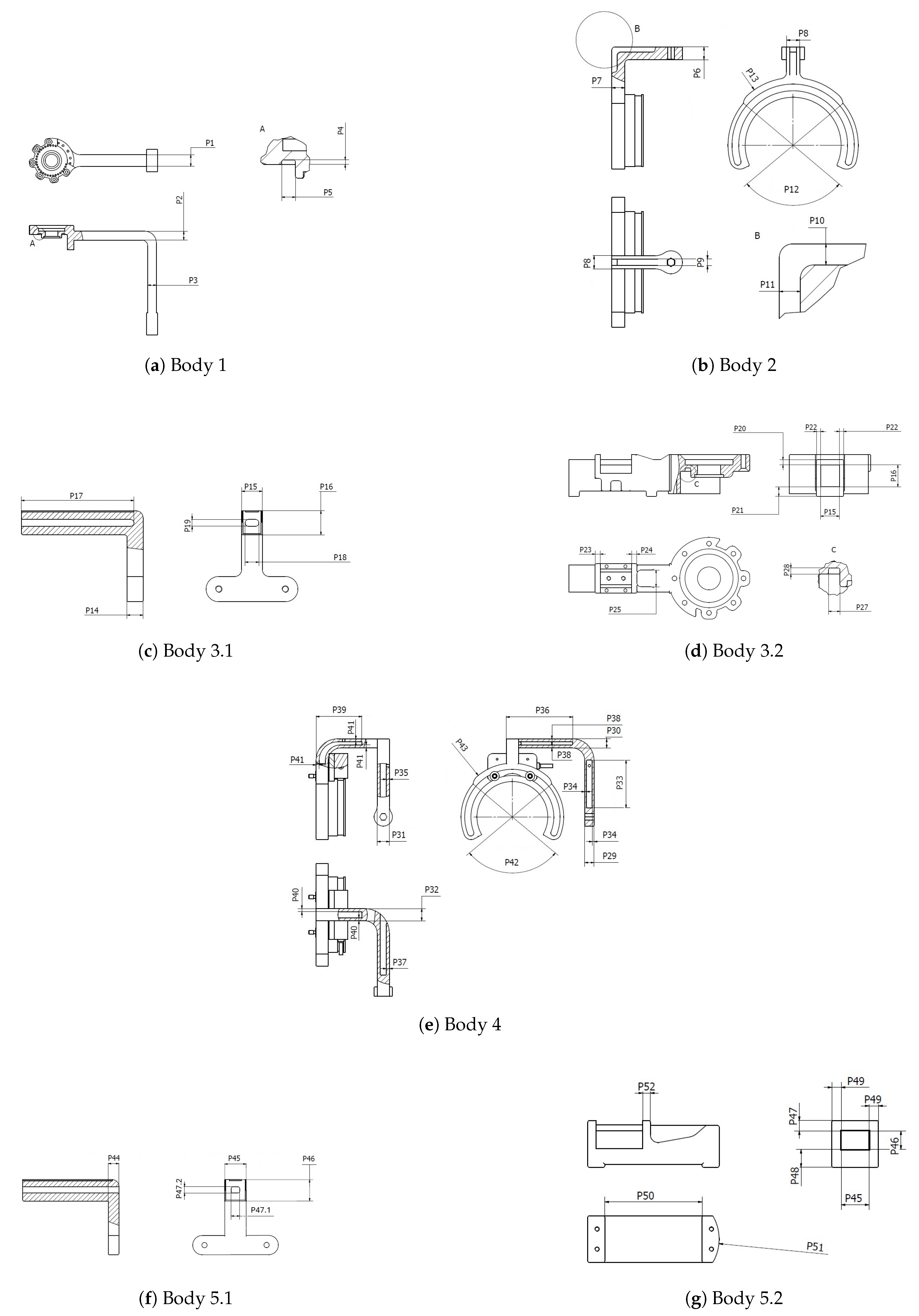

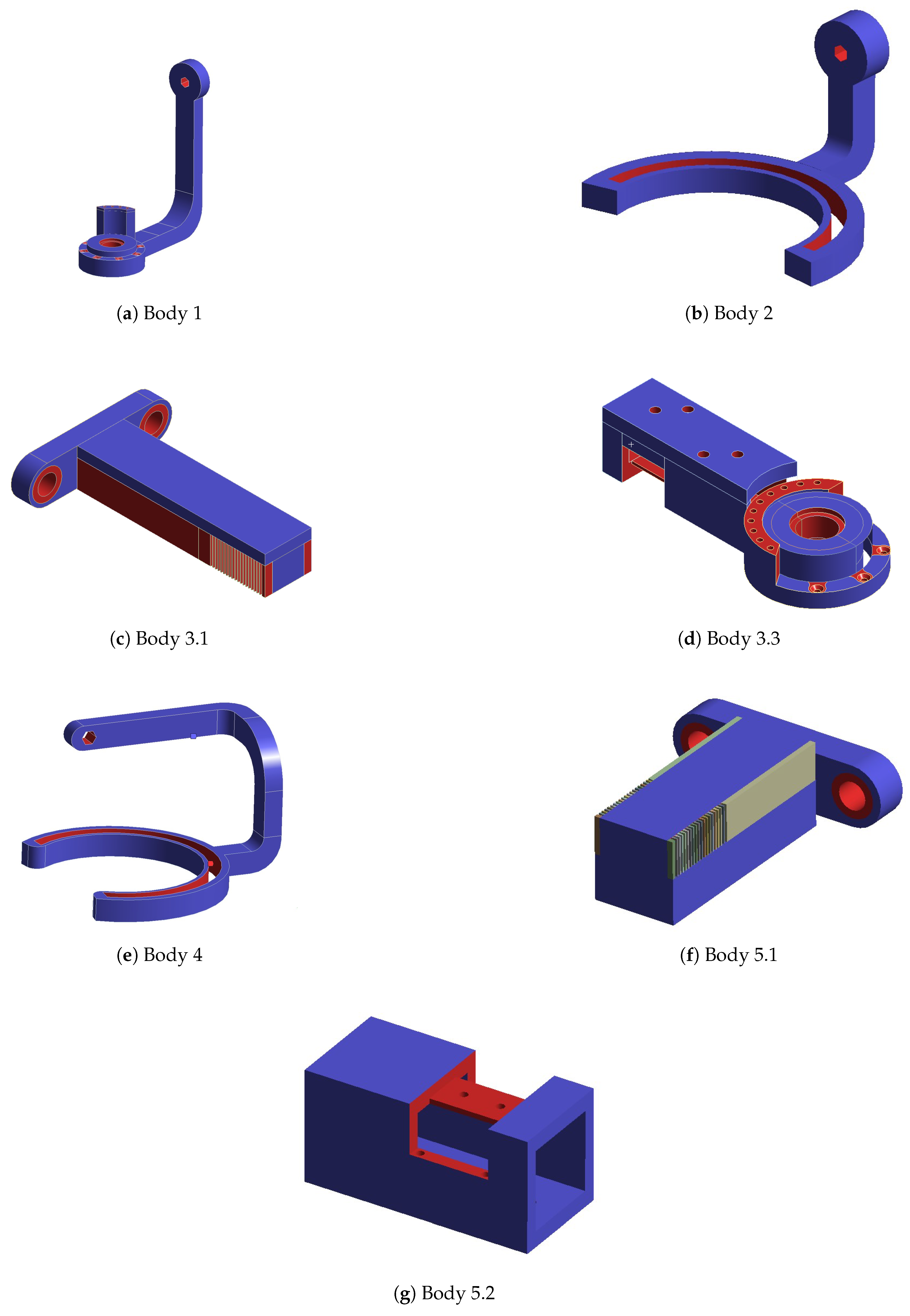

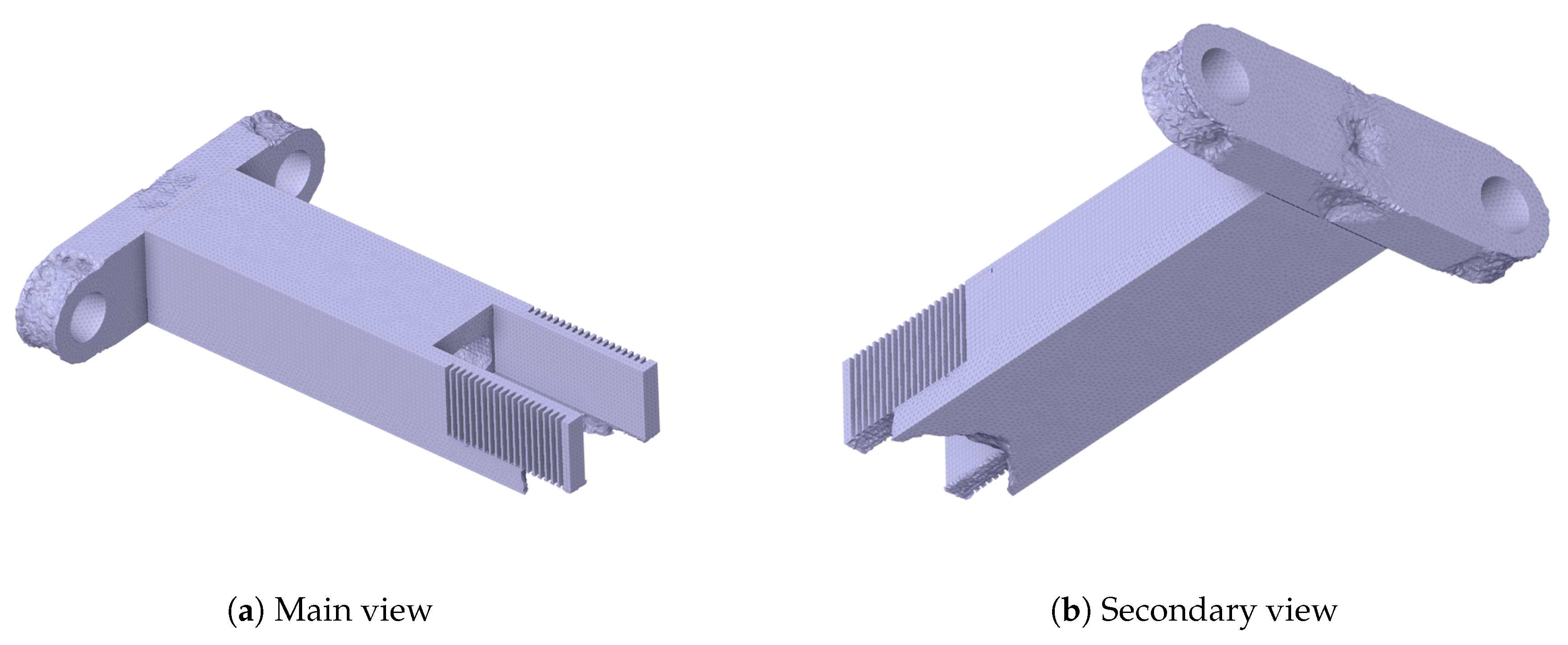

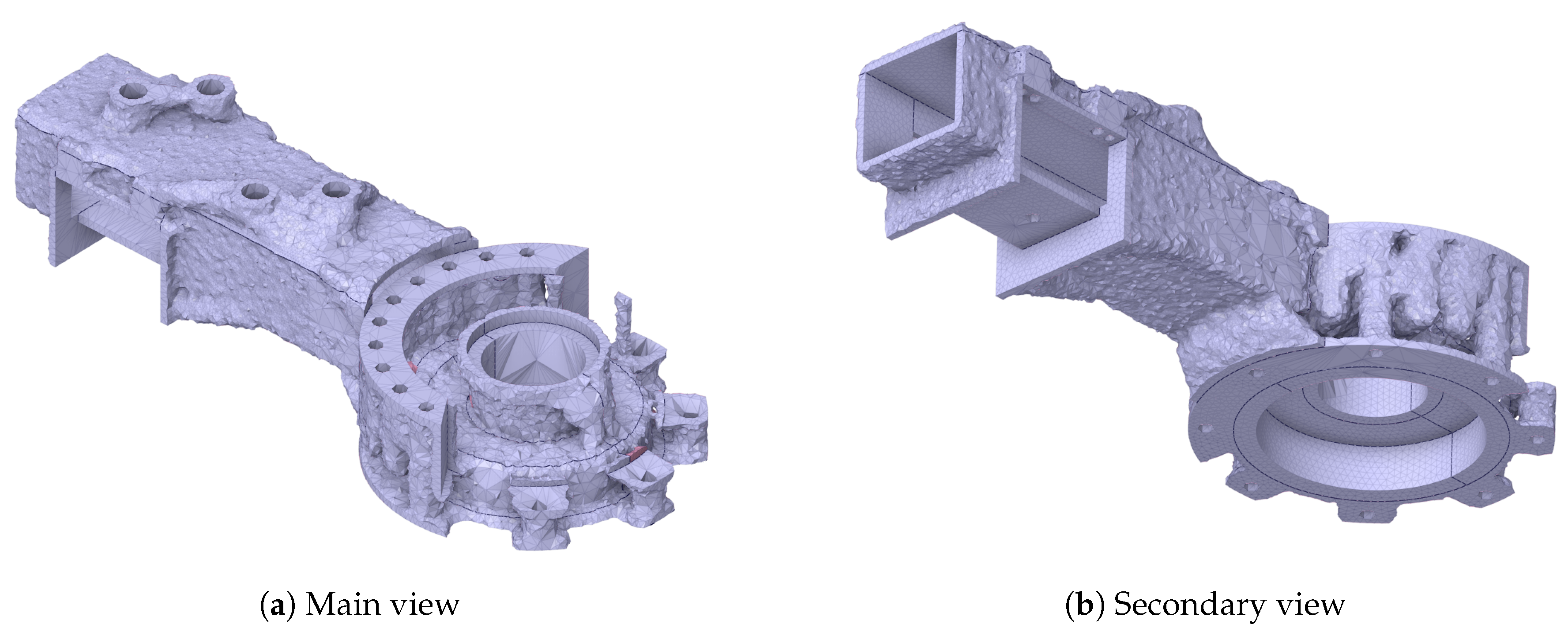

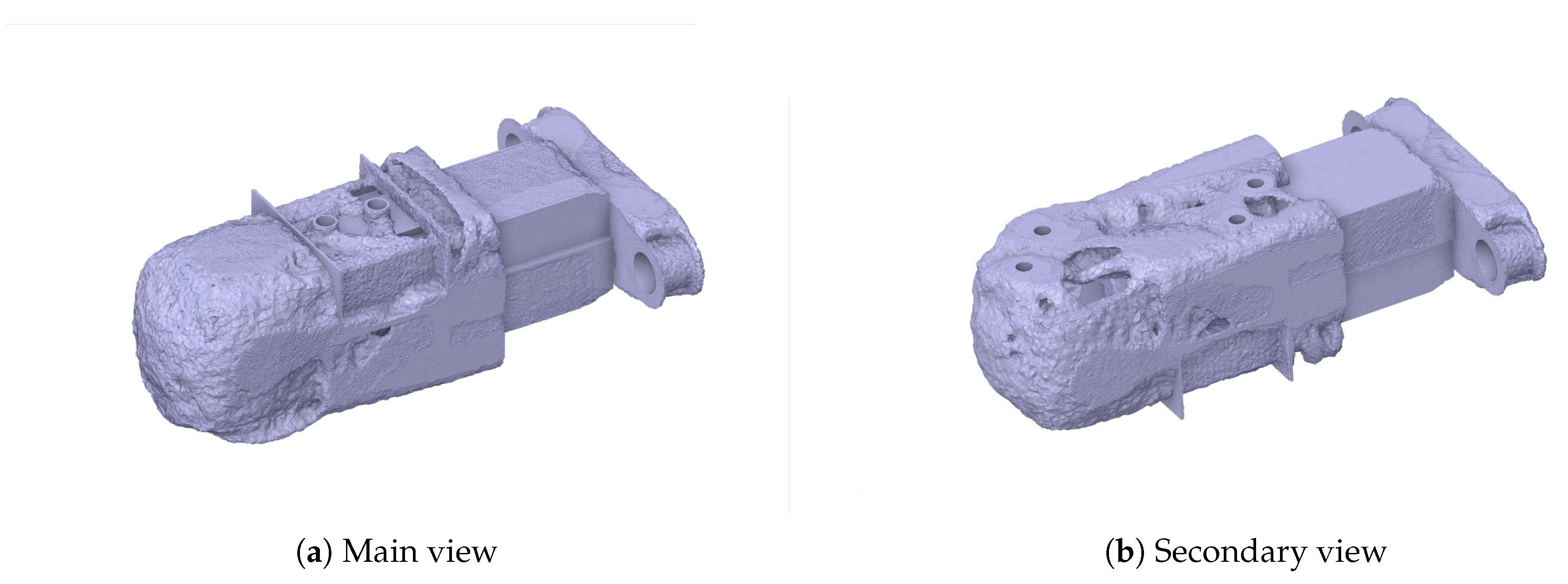

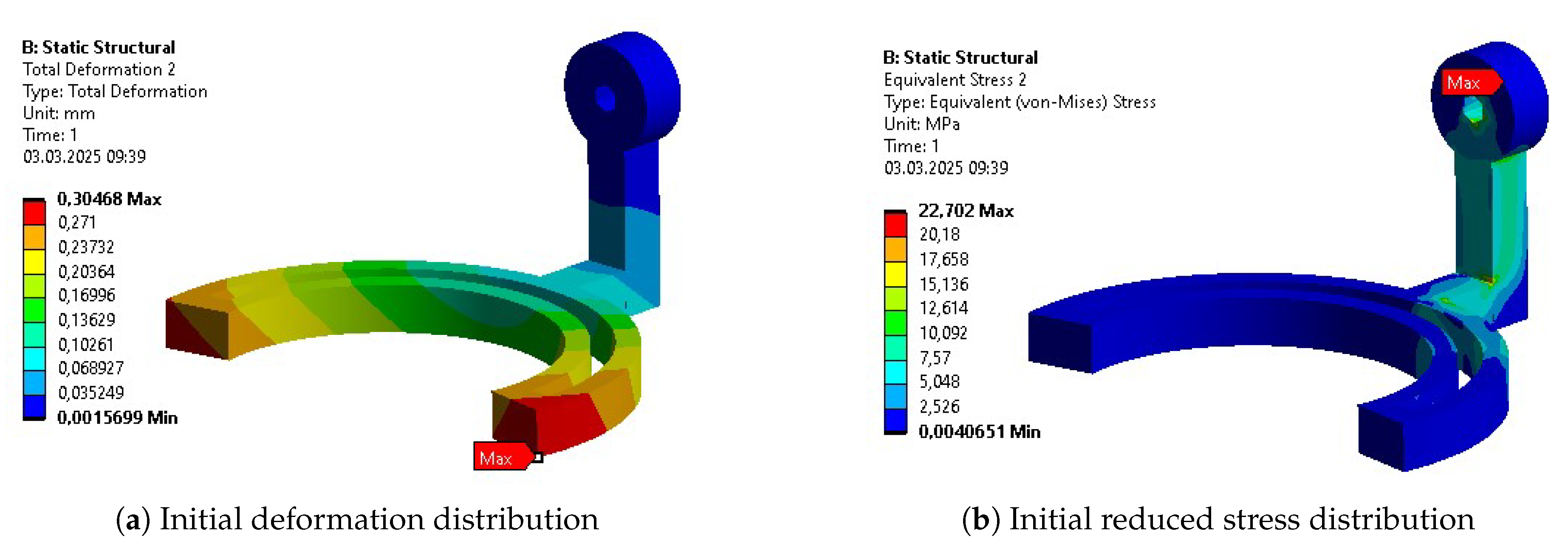

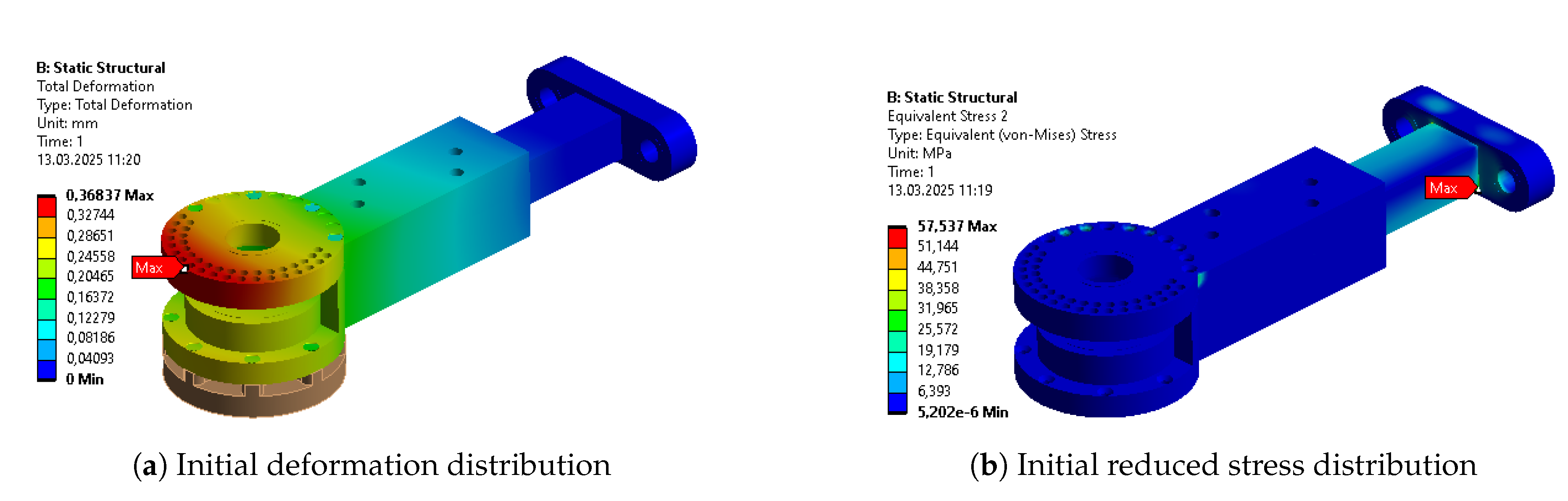

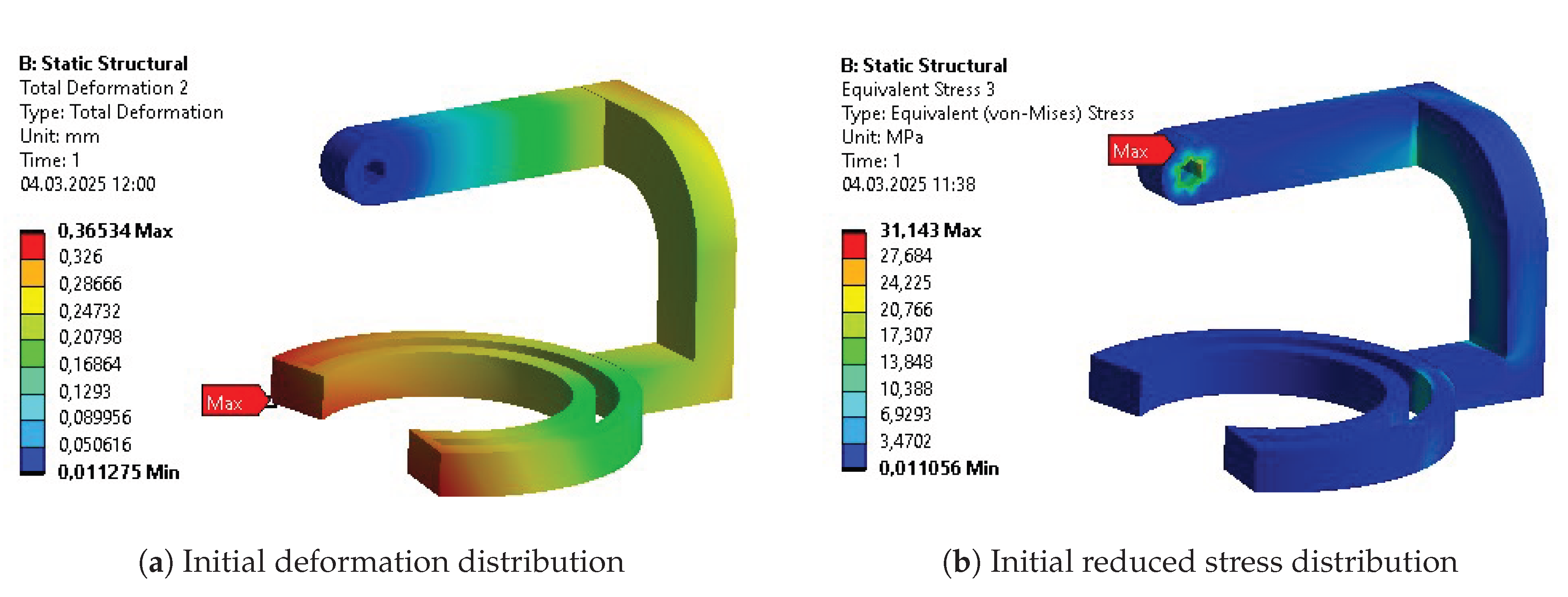

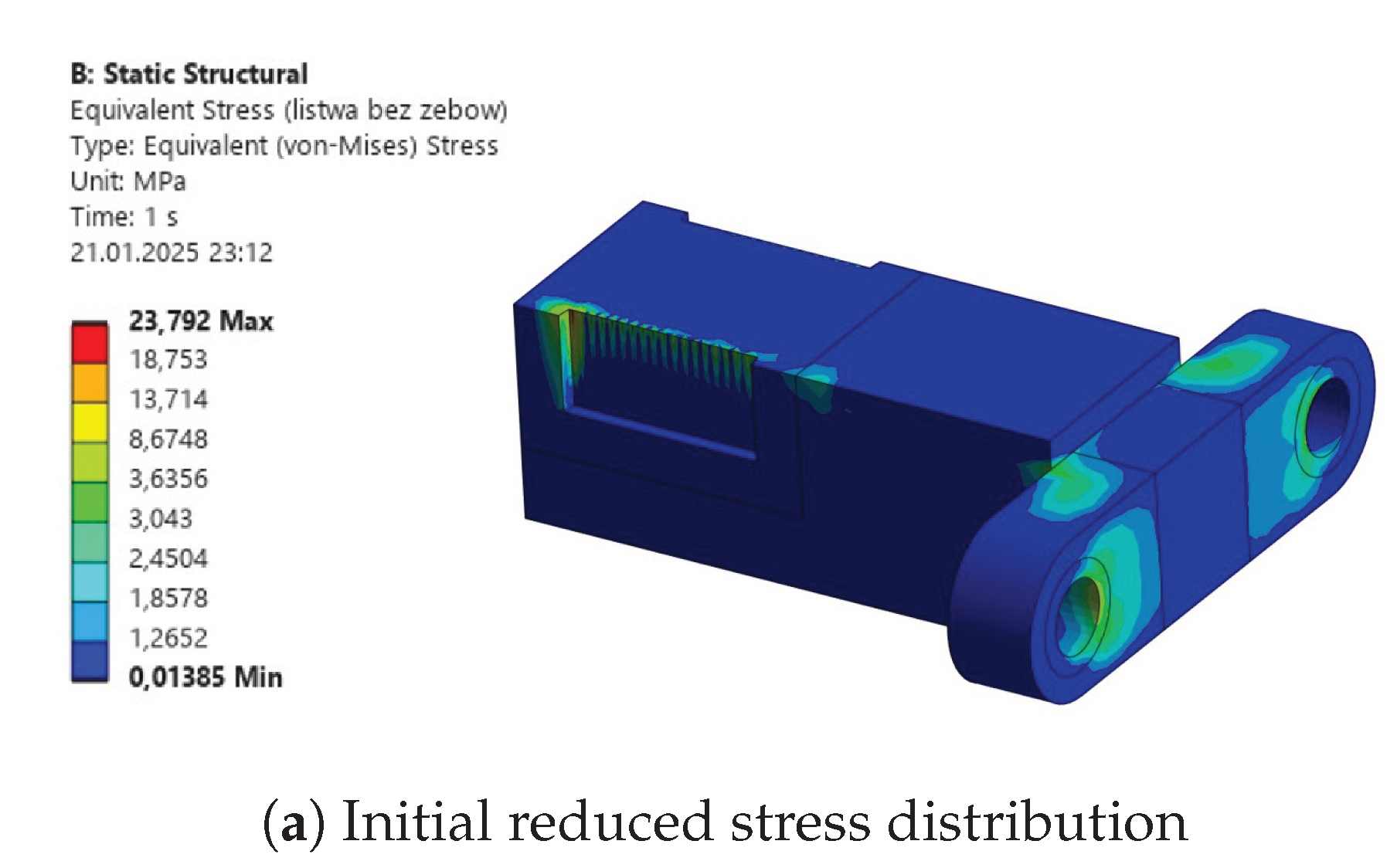

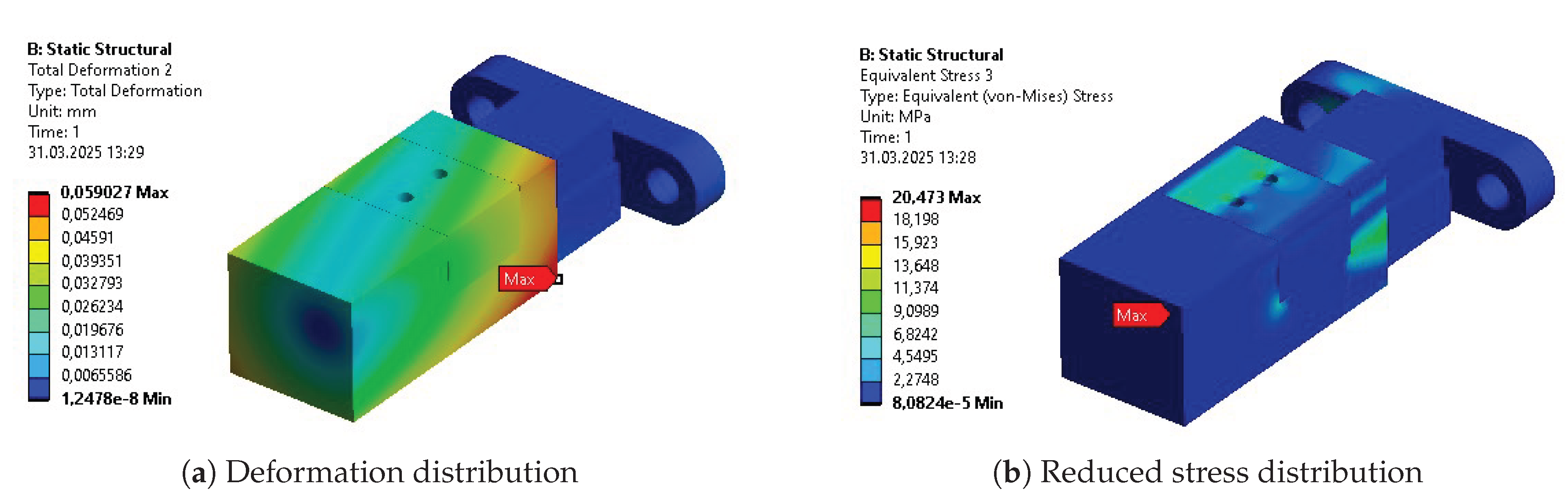

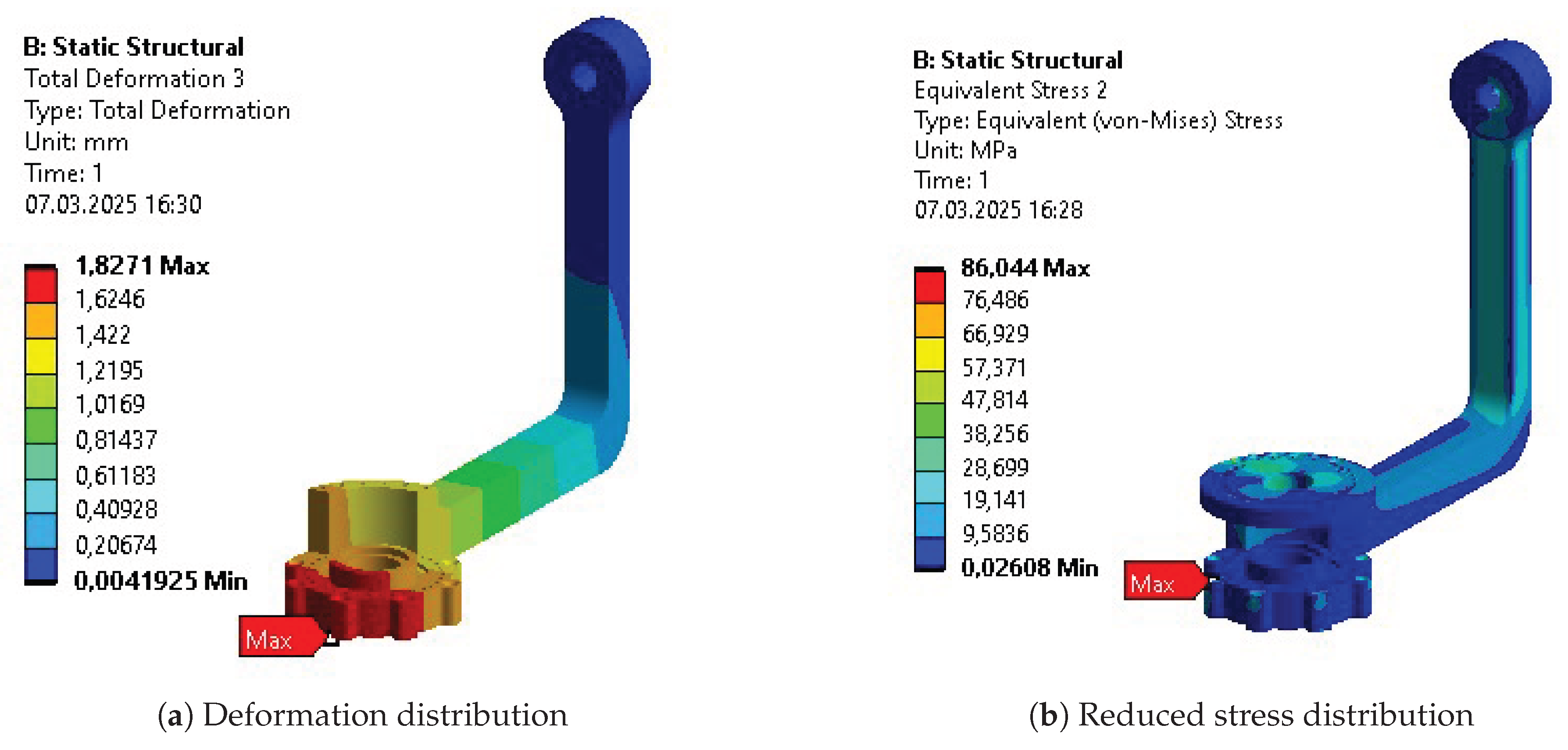

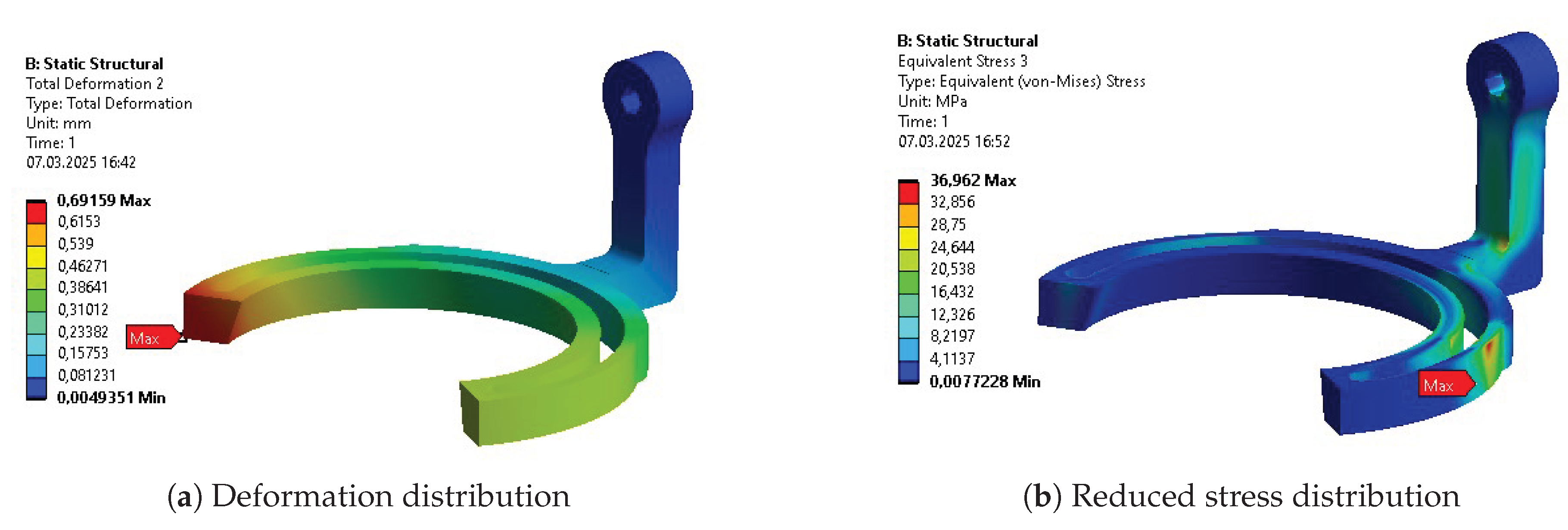

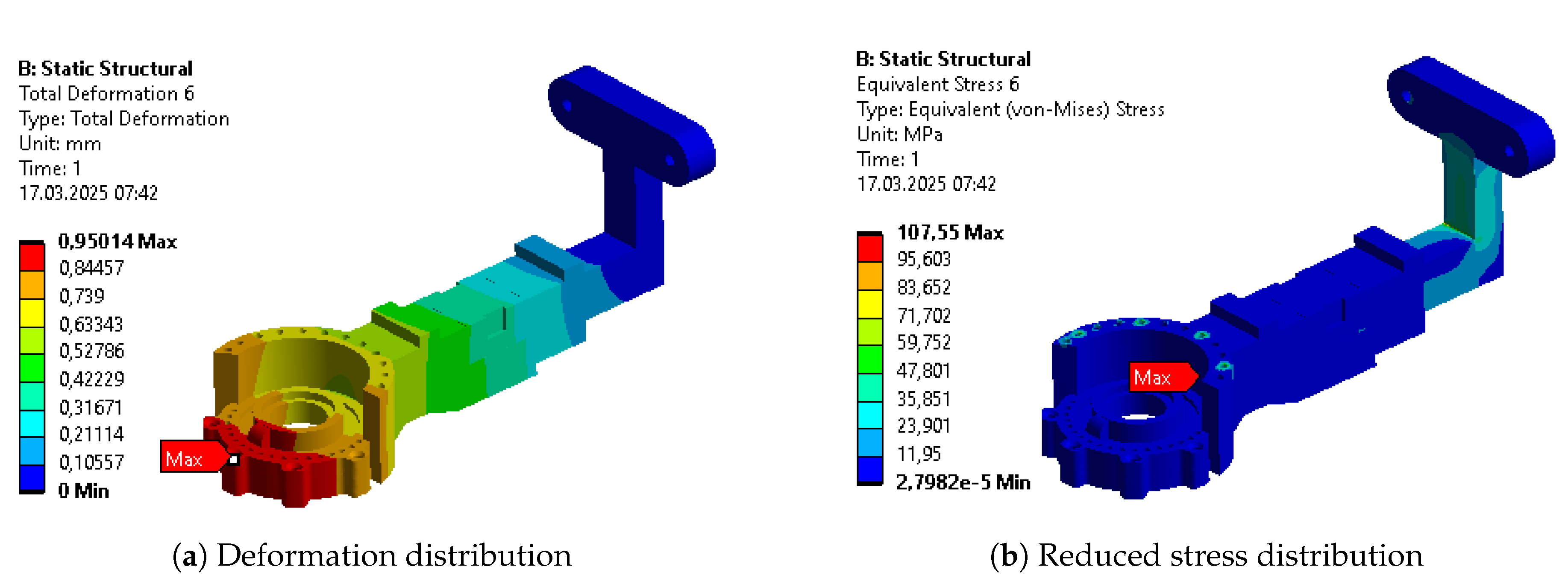

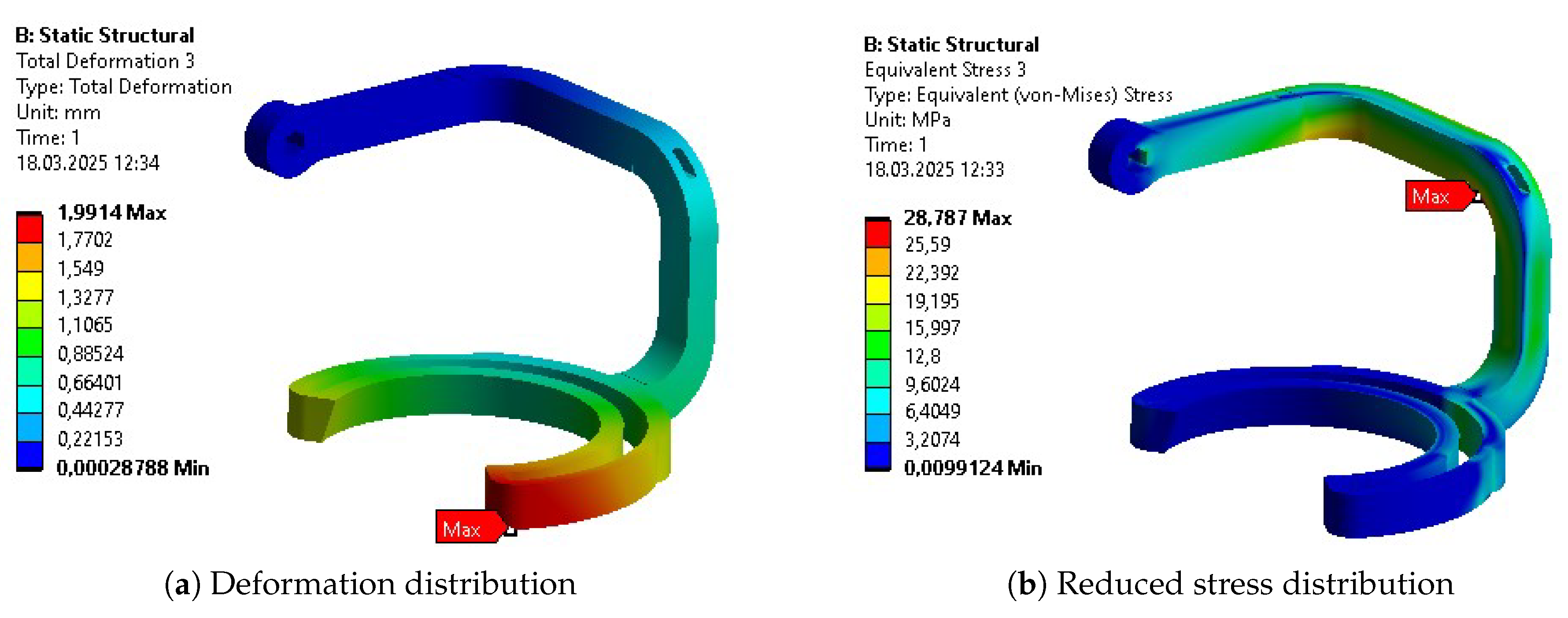

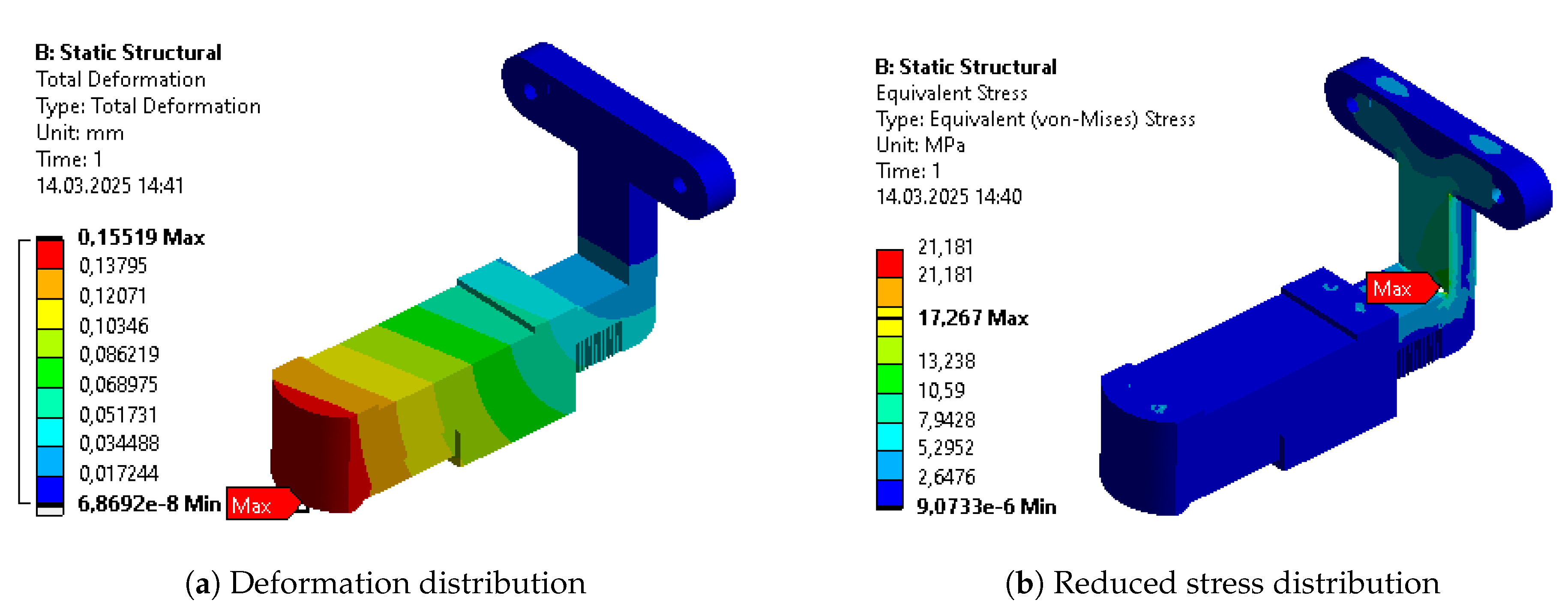

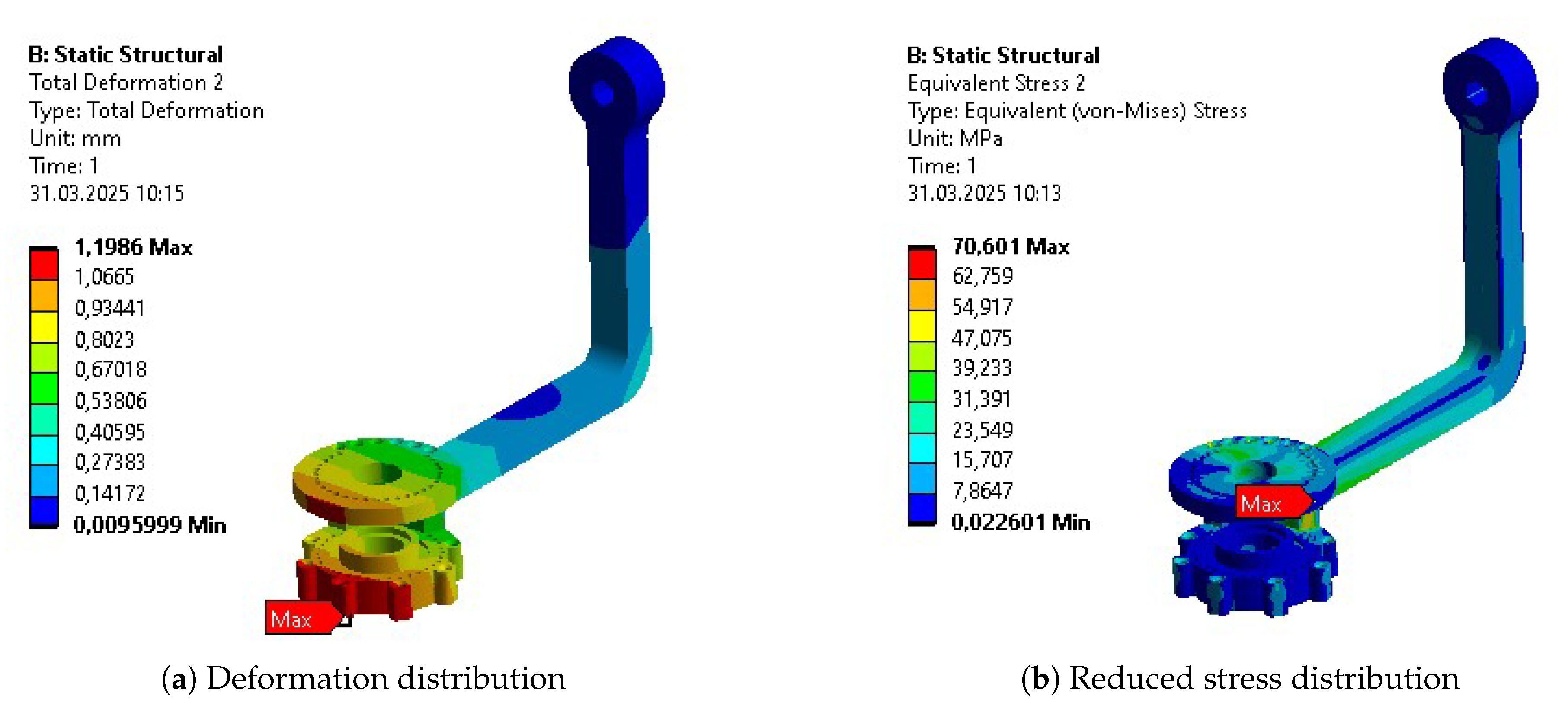

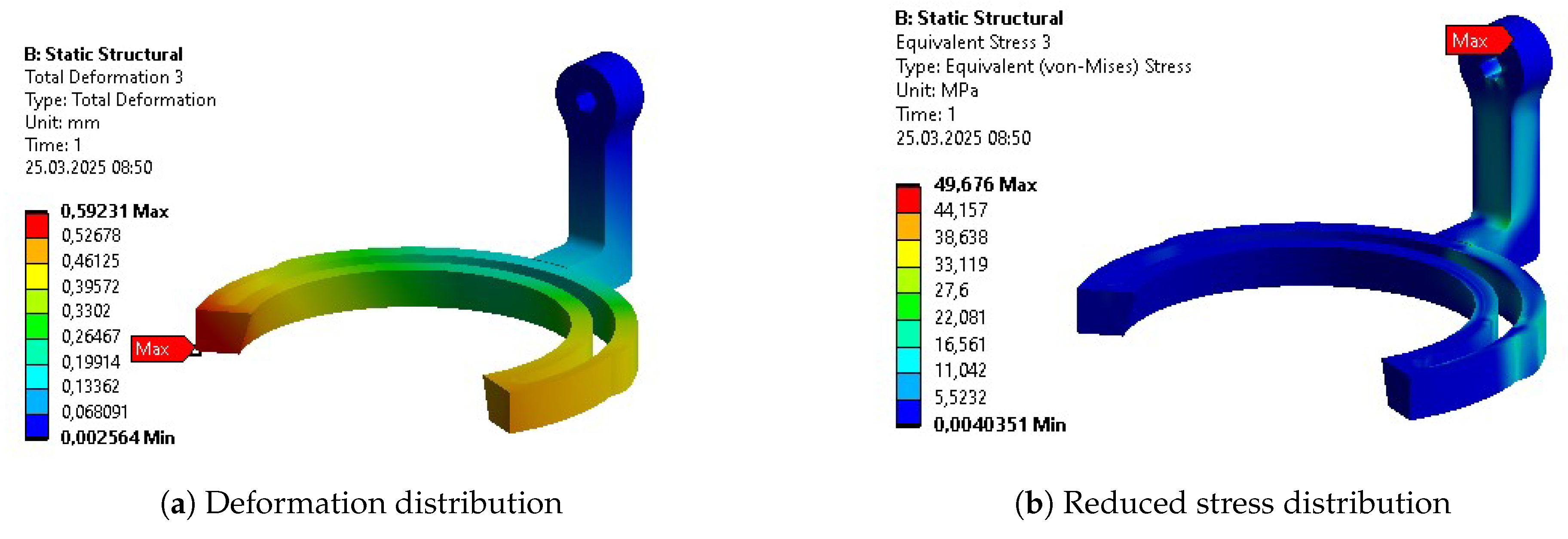

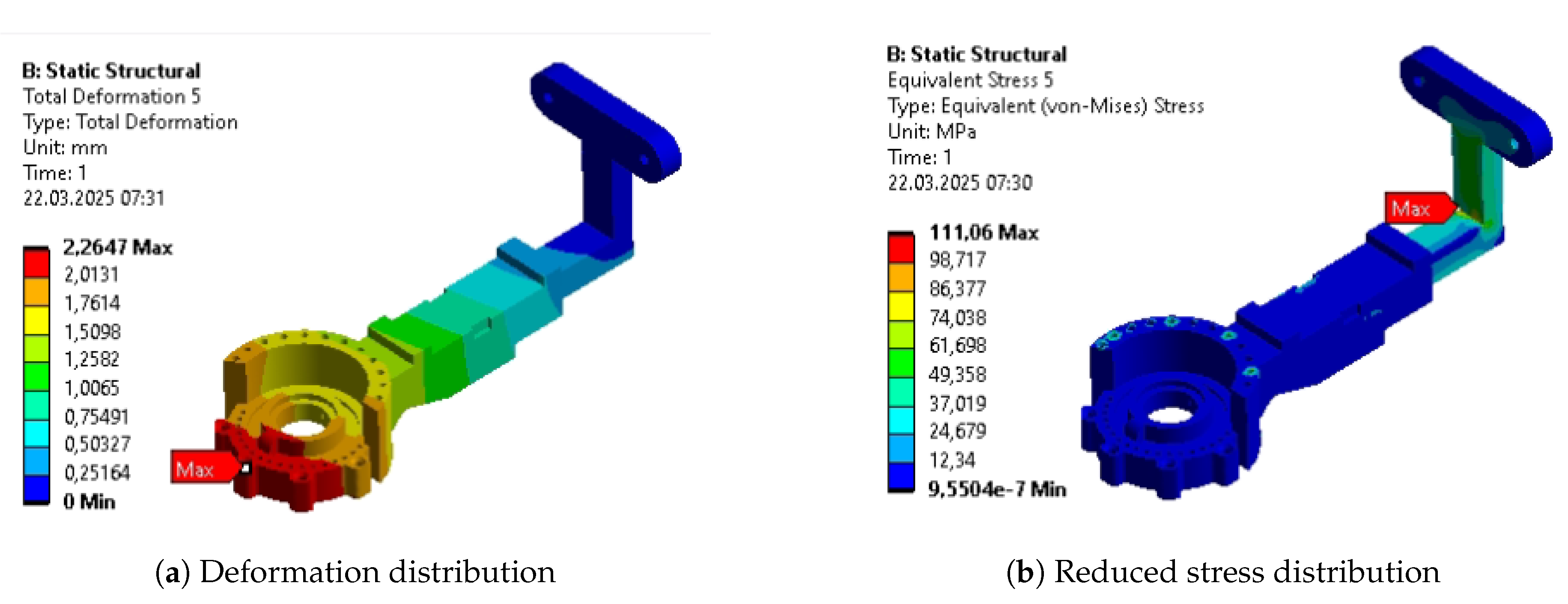

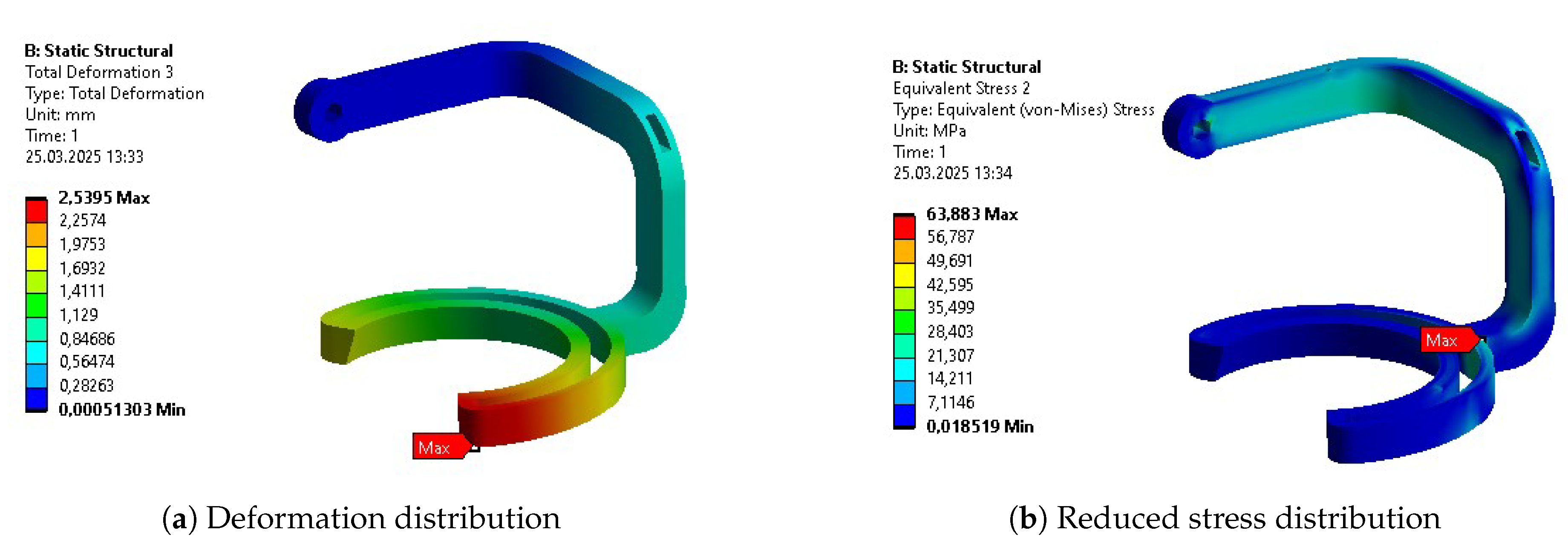

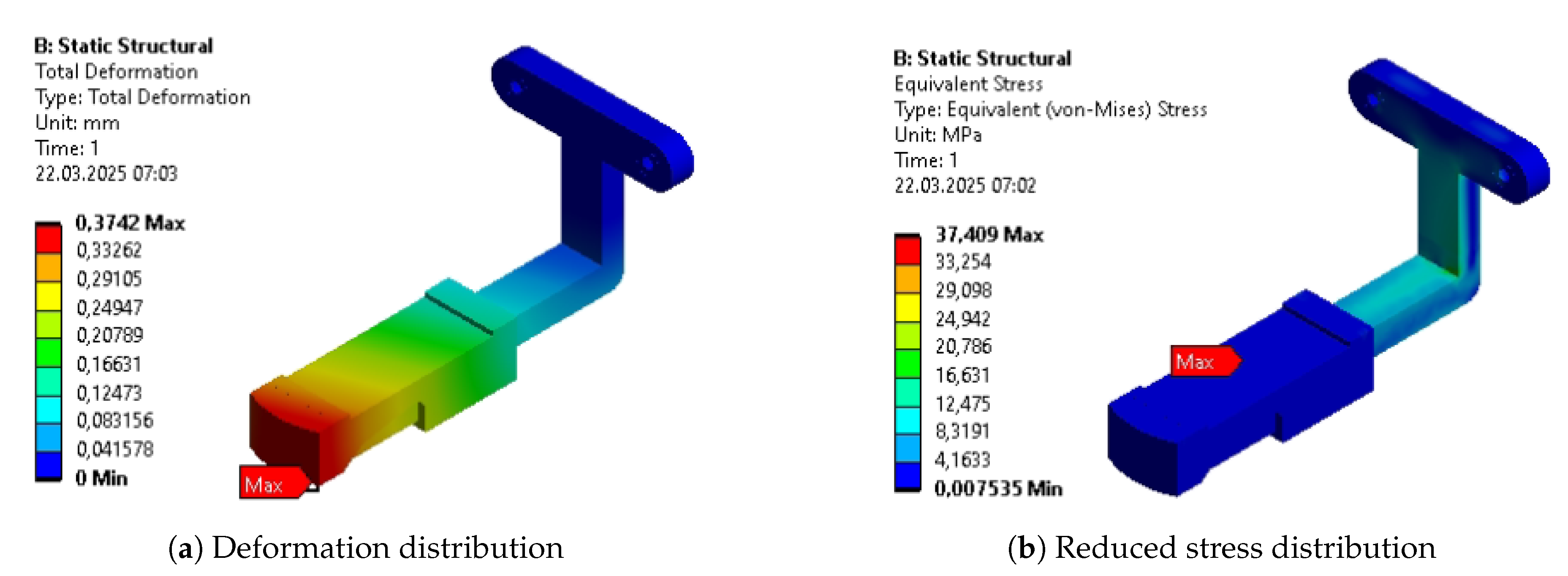

The optimization results at every stage are presented for separate bodies in

Table A3-

Table A7, while the results for the whole assembly are in

Table 10. The columns represent results for the initial design (INITIAL), after initial parametric optimization (PO 1), after topology optimization (TO), and after second parametric optimization (PO 2), respectively. Internal stress values are presented for the reduced Von-Mises’ average stress.

As aforementioned, the first parametric optimization had the greatest contribution to the overall mass reduction. The reduction of each individual segment varied from 10% to 50%, while the whole design weight decreased by more than 30% in the complete process. The average values of stress, strain, and deformation increased as expected. Each of these average outputs experienced growth that exceeded 30% of their initial values, with the average deformation almost doubling. The reduction of the mass was the most significant at the stage of initial parametric optimization. However, the stages of a complete process affected the parts unevenly. Some benefited greatly, while others experienced only minor changes.

The topological optimization has reduced the total mass by a little over 11% compared to its initial value and 17% compared to the mass from the previous step. The individual mass reduction of each of the segments varied from -15% to 35 % compared to the previous iteration. The negative reduction is caused by the addition of functional features, which required slightly more material than in previous iterations. It is worth noticing that the distribution of stress, deformation, and strain, measured by their average values, progressed almost as much as after the first parametric optimization.

The final design, determined by the second parametric optimization, has brought the total mass down by only about 5% compared to its initial value and a little under 10% compared to its mass after the topological optimization. Although contributing very little, compared to the previous stages, it is important to remember that the lower the mass of the exoskeleton, the harder it is to further optimize. The highest percentage of mass any individual segment lost in the entire process is almost 60%, while the lowest is around 40%.

Some of the most vulnerable points in newly acquired geometries are, naturally, regions around the bends of the links. They are highlighted in the initial strength analysis and remain as regions of stress concentration throughout the whole optimization process. Other regions, visible as the most vulnerable across the validation results, are fitted connections to the polygonal shaft of the rotational joints and the bolted connections to the motor mount in Bodies 1 and 3. Moreover, the features introduced based on topological optimization created additional areas of high accumulated stress. Finally, Body 1 has relatively high stress across the whole length of its arm, similar to the newly hollow upper part of Body 4.

The multistep optimization process with hybrid methods enabled significant mass reduction while meeting the strength criteria under real-life loads. However, the presented methods could still have been improved. These could involve different material models, optimization methods, or different orders from the methodology just presented. The parametric optimization process, although enforced by sensitivity analysis, might benefit from trying multiobjective optimization to better control the increased maximum values of stress and deformation. Different orders of the optimization types might result in a greater reduction of the mass or a more even influence over it between individual stages.

The changes in the design lowered its total mass and moments of inertia. These did not affect the device’s stiffness significantly, nor did they reach the elastic deformation region. Therefore, the therapy will be realized safely for the patients, and it is not expected to result in visible vibrations.

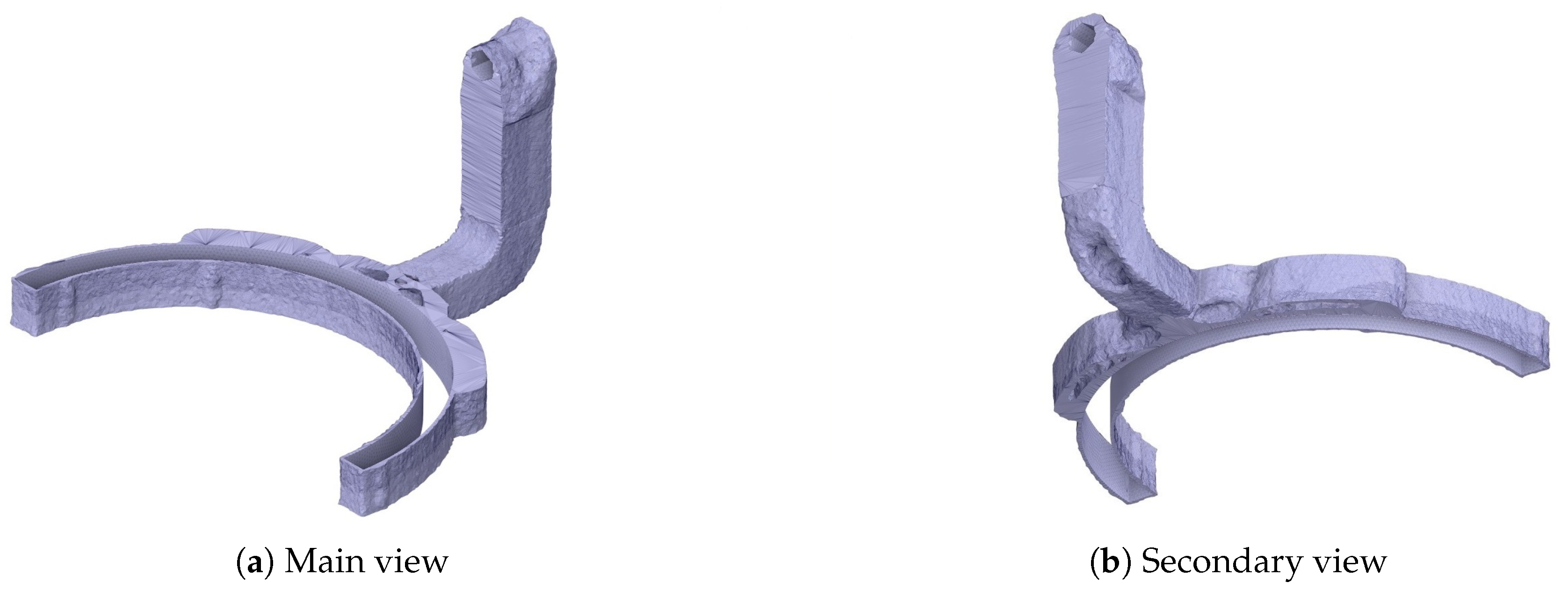

As assumed, modifications of the exoskeleton bodies brought a need for additive manufacturing. Within the research project, it was intended. However, for practical hospital use, the SLS-manufactured surfaces have high roughness. Therefore, they may not comply with hygienic standards and can be more difficult to clean after contamination. Moreover, especially in Body 4, the internal cavities brought technological holes that needed to be enclosed for use. The situation is similar in the regions next to the rotation joints - the removals similar to the motors’ mounting plate shape hindered the potential enclosure of the joint required by the medical devices’ standards. However, all of the removed aluminum geometries can be easily filled with lightweight polymers.

On the contrary, material removal in the mentioned regions also introduced a positive impact on the cost of manufacturing. The costs of 3D-printing technologies strongly correlate with the amount of material used. After the procedure, the cost of laser sintering of aluminum is lower than the initial costs of the design manufactured subtractively. Moreover, the additive technology design does not require additional technological divisions of the links.

The presented technology can be used to personalize components easily. It focuses on a combination of strength analysis with motion dynamics simulations. Therefore, every component can be directly modified and validated in terms of its strength. Once it is done, it can be manufactured with the process obtainable in many cities without the need to prepare technical documentation for milling. For this reason, the robot designed to support different individuals can be individualized without constantly engaging professional mechanical designers.

Reducing the mass and inertia of the main construction parts is expected to directly decrease the joint torques that actuators must generate to track a given rehabilitation trajectory. This can improve actuation efficiency and reduce energy consumption for comparable assistance levels [

39]. Moreover, studies on upper-body exoskeletons show that lightweight designs are perceived as more comfortable, enabling longer usage times, which are critical for effective neurorehabilitation [

40].

The designed elements were manufactured from

Aluminum in the SLS technique. The tests on the sintered material samples from the set printer proved the tensile properties corresponding to the ones known from literature [

41]. Therefore, it was assumed that the simulation results reflect real-life parts.

The assembled device was then used for tests of intelligent algorithms controlling rehabilitation exoskeletons with participants. A group of 22 participants has undergone experimental trials of active therapy with both intelligent assist-as-needed support and active therapy with constant admittance of the system. The motions performed in the experiments reflected 12 activities of daily living, covering the entire range of participants’ joint motions and the possible joint velocities assumed to be performed by the system. Within the experiments, none of the 3D-printed parts were deformed plastically. Moreover, none of the rotary joint motions was hindered by excessive deformations within the experiments. Considering these, the design intents of the exoskeleton can be assumed to be met.