Submitted:

09 January 2026

Posted:

12 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

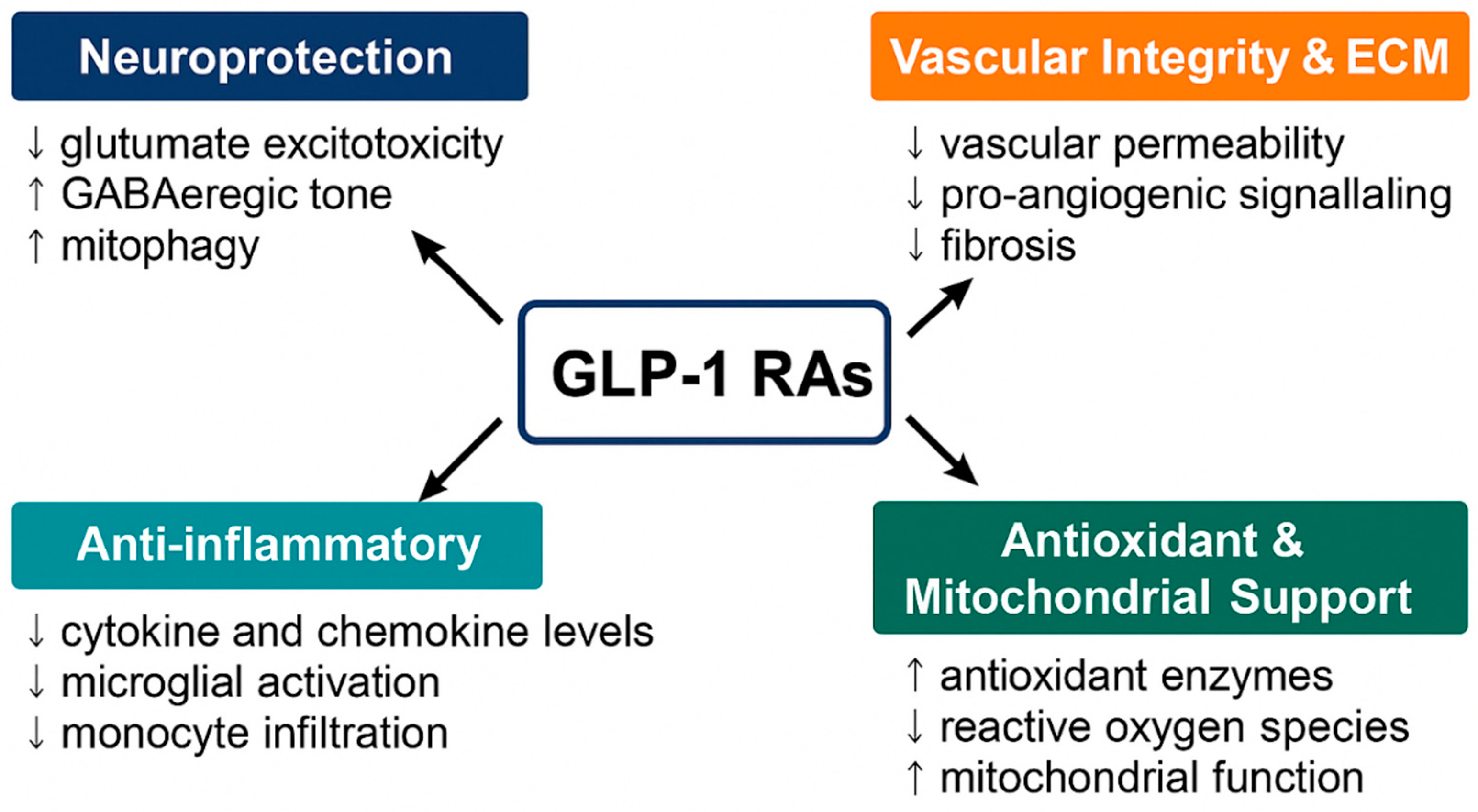

2. Mechanisms of Action of GLP-1RAs in Ocular Tissues

2.1. Neuroprotection

2.2. Vascular Integrity and ECM Homeostasis

2.3. Anti-Inflammatory Effects

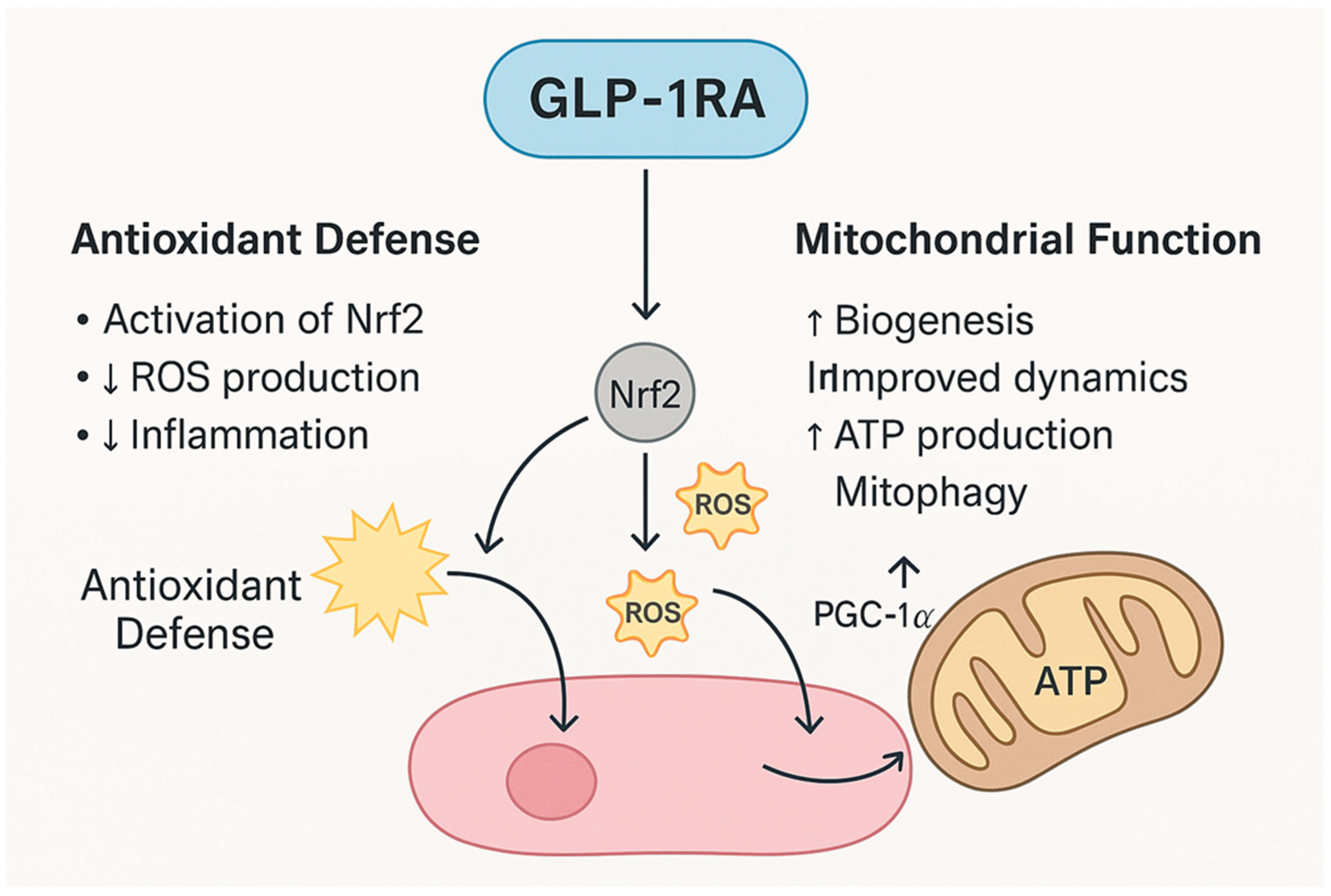

2.4. Antioxidant and Mitochondrial Support

3. Preclinical and Clinical Evidence Across Ocular Diseases

3.1. Glaucoma

3.2. Diabetic Retinopathy (DR)

3.3. Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

3.4. Cataract

3.5. Uveitis

4. Safety Considerations

4.1. Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (NAION)

4.2. Other Retinal and Optic Nerve Events

4.3. Conflicting Evidence and Null Findings

4.4. Clinical Implications

5. Challenges and Prospectives

5.1. Need for Targeted Ocular Delivery Strategies

5.2. Need for Rigorous Prospective Clinical Trials

5.3. Safety Evaluation and Risk Stratification

5.4. Implications for the Ophthalmic Community

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Drucker, D.J. GLP-1-based therapies for diabetes, obesity and beyond. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2025, 24, 631–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.K.; Drucker, D.J. Antiinflammatory actions of glucagon-like peptide-1-based therapies beyond metabolic benefits. J Clin Invest 2025, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.L.; Finn, A.P. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and the eye. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2025, 36, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaram, H.; Kolko, M.; Friedman, D.S.; Gazzard, G. Glaucoma: now and beyond. Lancet 2023, 402, 1788–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talebi, R.; Fortes, B.H.; Yu, F.; Coleman, A.L.; Tsui, I. Real-world Associations Between GLP-1 Receptor Agonist Use and Diabetic Retinopathy Accounting for Longitudinal Glycemic Control. Retina 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, N.; Al Issa, R.M.; Shah, A.; Wardeh, R.; Rashid, F.; Abdelgadir, E.I.; Bashier, A. In The Eye Of Controversy: A Deeper Look Into The Impact Of Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists (GLP1RA) on Diabetic Retinopathy and Non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (NAION). Can J Diabetes 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauqeer, Z.; Bracha, P.; Hua, P.; Yu, Y.; Cui, Q.N.; VanderBeek, B.L. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists are Not Associated with an Increased Risk of Progressing to Vision-Threatening Diabetic Retinopathy. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2025, 32, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebsgaard, J.B.; Pyke, C.; Yildirim, E.; Knudsen, L.B.; Heegaard, S.; Kvist, P.H. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor expression in the human eye. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018, 20, 2304–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puddu, A.; Sanguineti, R.; Montecucco, F.; Viviani, G.L. Retinal pigment epithelial cells express a functional receptor for glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Mediators Inflamm 2013, 2013, 975032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, D.J. Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Application of Glucagon-like Peptide-1. Cell Metab 2018, 27, 740–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Zong, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tian, Y.; Pang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Gao, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor: mechanisms and advances in therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.N.; Stein, L.M.; Fortin, S.M.; Hayes, M.R. The role of glia in the physiology and pharmacology of glucagon-like peptide-1: implications for obesity, diabetes, neurodegeneration and glaucoma. Br J Pharmacol 2022, 179, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, D.C.; Guedes, J.; Cruz, M.R.B.; Cheidde, L.; Nepomuceno, M.; Magalhaes, P.L.M.; Brazuna, R.; Mora-Paez, D.J.; Huang, P.; Razeghinejad, R.; et al. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Use and Incidence of Glaucoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Ophthalmol 2025, 271, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, M.; Asif, A.; Rahman, U.A.; Farooqi, H.A.; Fatima, O.; Ali, W.; Jafar, U.; Jaber, M.H. Incidence of Glaucoma in Type 2 Diabetes Patients Treated With GLP-1 Receptor Agonists: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab 2025, 8, e70059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talcott, K.E.; Rachitskaya, A.V.; Singh, R.P. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Use and Age-Related Macular Degeneration-Where Do We Stand? JAMA Ophthalmol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.Y.; Kuo, H.T.; Wang, Y.H.; Lin, C.J.; Shao, Y.C.; Chiang, C.C.; Hsia, N.Y.; Lai, C.T.; Tseng, H.; Wu, B.Q.; et al. Semaglutide and Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy Risk Among Patients With Diabetes. JAMA Ophthalmol 2025, 143, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Hamann, S.; Larsen, M. Semaglutide and non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy: Review and interpretation of reported association. Acta Ophthalmol 2025, 103, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marso, S.P.; Bain, S.C.; Consoli, A.; Eliaschewitz, F.G.; Jodar, E.; Leiter, L.A.; Lingvay, I.; Rosenstock, J.; Seufert, J.; Warren, M.L.; et al. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016, 375, 1834–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Joshi, P.; Barri, S.; Wang, J.; Corder, A.L.; O’Connell, S.S.; Fonseca, V.A. Progression of retinopathy with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists with cardiovascular benefits in type 2 diabetes - A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diabetes Complications 2022, 36, 108255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shor, R.; Mihalache, A.; Noori, A.; Shor, R.; Kohly, R.P.; Popovic, M.M.; Muni, R.H. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Risk of Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol 2025, 143, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Yang, Z.; Tian, D.; Chen, Y. Unlocking the potential of GLP-1 receptor agonists in ocular therapeutics: from molecular pathways to clinical impact. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1618079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usategui-Martin, R.; Fernandez-Bueno, I. Neuroprotective therapy for retinal neurodegenerative diseases by stem cell secretome. Neural Regen Res 2021, 16, 117–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenca, N.; Fernandez-Sanchez, L.; Campello, L.; Maneu, V.; De la Villa, P.; Lax, P.; Pinilla, I. Cellular responses following retinal injuries and therapeutic approaches for neurodegenerative diseases. Prog Retin Eye Res 2014, 43, 17–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreasen, C.R.; Andersen, A.; Knop, F.K.; Vilsboll, T. How glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists work. Endocr Connect 2021, 10, R200–R212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ruan, H.Z.; Wang, Y.C.; Shao, Y.Q.; Zhou, W.; Weng, S.J.; Zhong, Y.M. Signaling Mechanism for Modulation by GLP-1 and Exendin-4 of GABA Receptors on Rat Retinal Ganglion Cells. Neurosci Bull 2022, 38, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.Q.; Wang, Y.C.; Wang, L.; Ruan, H.Z.; Liu, Y.F.; Zhang, T.H.; Weng, S.J.; Yang, X.L.; Zhong, Y.M. Topical administration of GLP-1 eyedrops improves retinal ganglion cell function by facilitating presynaptic GABA release in early experimental diabetes. Neural Regen Res 2026, 21, 800–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Li, J.; Wang, M.; She, M.; Tang, Y.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Hui, H. GLP-1 Treatment Improves Diabetic Retinopathy by Alleviating Autophagy through GLP-1R-ERK1/2-HDAC6 Signaling Pathway. Int J Med Sci 2017, 14, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.R.; Ma, X.F.; Lin, W.J.; Hao, M.; Yu, X.Y.; Li, H.X.; Xu, C.Y.; Kuang, H.Y. Neuroprotective Role of GLP-1 Analog for Retinal Ganglion Cells via PINK1/Parkin-Mediated Mitophagy in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front Pharmacol 2020, 11, 589114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, A.; Lin, C.M.; Muthusamy, A.; Fontes-Ribeiro, C.; Ambrosio, A.F.; Abcouwer, S.F.; Fernandes, R.; Antonetti, D.A. Protective Effect of a GLP-1 Analog on Ischemia-Reperfusion Induced Blood-Retinal Barrier Breakdown and Inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2016, 57, 2584–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Xu, Z.; Oh, Y.; Gamuyao, R.; Lee, G.; Xie, Y.; Cho, H.; Lee, S.; Duh, E.J. Myeloid cell modulation by a GLP-1 receptor agonist regulates retinal angiogenesis in ischemic retinopathy. JCI Insight 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhao, K.; Xu, C.; Li, H.; Hu, Y.; Lin, W.; Ma, X.; Xu, Q.; Kuang, H.; et al. Liraglutide intervention improves high-glucose-induced reactive gliosis of Muller cells and ECM dysregulation. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2023, 576, 112013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitcup, S.M.; Nussenblatt, R.B.; Lightman, S.L.; Hollander, D.A. Inflammation in retinal disease. Int J Inflam 2013, 2013, 724648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto, I.; Krebs, M.P.; Reagan, A.M.; Howell, G.R. Vascular Inflammation Risk Factors in Retinal Disease. Annu Rev Vis Sci 2019, 5, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egwuagu, C.E. Chronic intraocular inflammation and development of retinal degenerative disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 2014, 801, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrillo, F.; Gesualdo, C.; Platania, C.B.M.; D’Amico, M.; Trotta, M.C. Editorial: Chronic Inflammation and Neurodegeneration in Retinal Disease. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 784770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puddu, A.; Maggi, D. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of GLP-1R Activation in the Retina. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, A.E.; Gaoatswe, G.; Lynch, L.; Corrigan, M.A.; Woods, C.; O’Connell, J.; O’Shea, D. Glucagon-like peptide 1 analogue therapy directly modulates innate immune-mediated inflammation in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2014, 57, 781–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.; Bogdanov, P.; Corraliza, L.; Garcia-Ramirez, M.; Sola-Adell, C.; Arranz, J.A.; Arroba, A.I.; Valverde, A.M.; Simo, R. Topical Administration of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists Prevents Retinal Neurodegeneration in Experimental Diabetes. Diabetes 2016, 65, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes-da-Silva, R.M.; de Souza Marinho, T.; de Macedo Cardoso, L.E.; Mandarim-de-Lacerda, C.A.; Aguila, M.B. Obese mice weight loss role on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and endoplasmic reticulum stress treated by a GLP-1 receptor agonist. Int J Obes (Lond) 2022, 46, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, G.A.; Katsiki, N.; Blundell, J.; Fruhbeck, G.; Kiortsis, D.N. Semaglutide as a promising antiobesity drug. Obes Rev 2019, 20, 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Cassidy, R.S.; Tate, M.; Zhao, Y.; Lockhart, S.; Calderwood, D.; Church, R.; McGahon, M.K.; Brazil, D.P.; McDermott, B.J.; et al. Exendin-4 protects against post-myocardial infarction remodelling via specific actions on inflammation and the extracellular matrix. Basic Res Cardiol 2015, 110, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, J.; Bogdanov, P.; Ramos, H.; Sola-Adell, C.; Turch, M.; Valeri, M.; Simo-Servat, O.; Lagunas, C.; Simo, R.; Hernandez, C. New Insights into the Mechanisms of Action of Topical Administration of GLP-1 in an Experimental Model of Diabetic Retinopathy. J Clin Med 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Munch, A.E.; Chung, W.S.; Peterson, T.C.; et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttenplan, K.A.; Stafford, B.K.; El-Danaf, R.N.; Adler, D.I.; Munch, A.E.; Weigel, M.K.; Huberman, A.D.; Liddelow, S.A. Neurotoxic Reactive Astrocytes Drive Neuronal Death after Retinal Injury. Cell Rep 2020, 31, 107776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.K.; Yusta, B.; Koehler, J.A.; Baggio, L.L.; McLean, B.A.; Matthews, D.; Seeley, R.J.; Drucker, D.J. Divergent roles for the gut intraepithelial lymphocyte GLP-1R in control of metabolism, microbiota, and T cell-induced inflammation. Cell Metab 2022, 34, 1514–1531 e1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.S.; Jun, H.S. Effects of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 on Oxidative Stress and Nrf2 Signaling. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Li, L.; Zhu, L.; Guo, Y.; Du, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, M. Geniposide Attenuates Hyperglycemia-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation by Activating the Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Experimental Diabetic Retinopathy. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 9247947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Sun, L.; Wei, L.; Liu, J.; Zhu, J.; Yu, Q.; Kong, H.; Kong, L. Liraglutide Up-regulation Thioredoxin Attenuated Muller Cells Apoptosis in High Glucose by Regulating Oxidative Stress and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Curr Eye Res 2020, 45, 1283–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, J.K.; Adetunji, M.O.; Guttha, S.; Bargoud, A.R.; Uyhazi, K.E.; Ross, A.G.; Dunaief, J.L.; Cui, Q.N. GLP-1 Receptor Agonist NLY01 Reduces Retinal Inflammation and Neuron Death Secondary to Ocular Hypertension. Cell Rep 2020, 33, 108271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.C.N.; Guo, M.; Schwartz, T.D.; Wu, J.; Lu, J.; Nikonov, S.; Sterling, J.K.; Cui, Q.N. Topical and systemic GLP-1R agonist administration both rescue retinal ganglion cells in hypertensive glaucoma. Front Cell Neurosci 2023, 17, 1156829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhammad, Z.A.; Rombaut, A.; Bermudez, M.Y.G.; Vohra, R.; Tribble, J.R.; Williams, P.A.; Kolko, M. Systemic semaglutide provides a mild vasoprotective and antineuroinflammatory effect in a rat model of ocular hypertensive glaucoma. Mol Brain 2025, 18, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterling, J.; Hua, P.; Dunaief, J.L.; Cui, Q.N.; VanderBeek, B.L. Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist use is associated with reduced risk for glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2023, 107, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.C.; Wang, K.; Chang, C.K.; Lee, C.Y.; Huang, J.Y.; Wu, H.H.; Yang, P.J.; Yang, S.F. Prescription of glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists and risk of subsequent open-angle glaucoma in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Med Sci 2024, 21, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, S.; Gnesin, F.; Thein, A.S.; Andreasen, J.R.; Horwitz, A.; Mouhammad, Z.A.; Jawad, B.N.; Niazi, Z.; Pourhadi, N.; Zareini, B.; et al. Association between Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and the Risk of Glaucoma in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muayad, J.; Loya, A.; Hussain, Z.S.; Chauhan, M.Z.; Alsoudi, A.F.; De Francesco, T.; Ahmed, I.I.K. Comparative Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonists and Metformin on Glaucoma Risk in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasu, P.; Dorairaj, E.A.; Weinreb, R.N.; Huang, A.S.; Dorairaj, S.K. Risk of Glaucoma in Patients without Diabetes Using a Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh, E.J.; Sun, J.K.; Stitt, A.W. Diabetic retinopathy: current understanding, mechanisms, and treatment strategies. JCI Insight 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varughese, G.I.; Jacob, S. Existing and emerging GLP-1 receptor agonist therapy: Ramifications for diabetic retinopathy screening. J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2024, 54, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Huang, C. Exendin-4, a GLP-1 receptor agonist, suppresses diabetic retinopathy in vivo and in vitro. Arch Physiol Biochem 2025, 131, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.C.; Wang, L.; Shao, Y.Q.; Weng, S.J.; Yang, X.L.; Zhong, Y.M. Exendin-4 promotes retinal ganglion cell survival and function by inhibiting calcium channels in experimental diabetes. iScience 2023, 26, 107680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J.; Han, W.N.; Chai, S.F.; Li, Y.; Fu, C.J.; Wang, C.F.; Cai, H.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Wang, X.; Holscher, C.; et al. Semaglutide promotes the transition of microglia from M1 to M2 type to reduce brain inflammation in APP/PS1/tau mice. Neuroscience 2024, 563, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.K.; McLean, B.A.; Baggio, L.L.; Koehler, J.A.; Hammoud, R.; Rittig, N.; Yabut, J.M.; Seeley, R.J.; Brown, T.J.; Drucker, D.J. Central glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor activation inhibits Toll-like receptor agonist-induced inflammation. Cell Metab 2024, 36, 130–143 e135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Mo, W.; Lan, S.; Yang, H.; Huang, Z.; Liang, X.; Li, L.; Xian, J.; Xie, X.; Qin, Y.; et al. GLP-1 RA Improves Diabetic Retinopathy by Protecting the Blood-Retinal Barrier through GLP-1R-ROCK-p-MLC Signaling Pathway. J Diabetes Res 2022, 2022, 1861940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oezer, K.; Kolibabka, M.; Gassenhuber, J.; Dietrich, N.; Fleming, T.; Schlotterer, A.; Morcos, M.; Wohlfart, P.; Hammes, H.P. The effect of GLP-1 receptor agonist lixisenatide on experimental diabetic retinopathy. Acta Diabetol 2023, 60, 1551–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, I.; Sarvepalli, S.M.; D’Alessio, D.; Grewal, D.S.; Hadziahmetovic, M. GLP-1 receptor agonists and diabetic retinopathy: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Surv Ophthalmol 2023, 68, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Li, N.; Hou, R.; Zhang, X.; Wu, L.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K.; Ji, J. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and diabetic retinopathy: nationwide cohort and Mendelian randomization studies. BMC Med 2023, 21, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilsboll, T.; Bain, S.C.; Leiter, L.A.; Lingvay, I.; Matthews, D.; Simo, R.; Helmark, I.C.; Wijayasinghe, N.; Larsen, M. Semaglutide, reduction in glycated haemoglobin and the risk of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Obes Metab 2018, 20, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akil, H.; Burgess, J.; Nevitt, S.; Harding, S.P.; Alam, U.; Burgess, P. Early Worsening of Retinopathy in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes After Rapid Improvement in Glycaemic Control: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Ther 2022, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethel, M.A.; Stevens, S.R.; Buse, J.B.; Choi, J.; Gustavson, S.M.; Iqbal, N.; Lokhnygina, Y.; Mentz, R.J.; Patel, R.A.; Ohman, P.; et al. Exploring the Possible Impact of Unbalanced Open-Label Drop-In of Glucose-Lowering Medications on EXSCEL Outcomes. Circulation 2020, 141, 1360–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckenstein, M.; Keenan, T.D.L.; Guymer, R.H.; Chakravarthy, U.; Schmitz-Valckenberg, S.; Klaver, C.C.; Wong, W.T.; Chew, E.Y. Age-related macular degeneration. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, R.B.; Klein, W.; Reinauer, R.M. Real-World Outcomes with Complement Inhibitors for Geographic Atrophy: A Comparative Study of Pegacetacoplan versus Avacincaptad Pegol. Clin Ophthalmol 2025, 19, 1167–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleckenstein, M.; Mitchell, P.; Freund, K.B.; Sadda, S.; Holz, F.G.; Brittain, C.; Henry, E.C.; Ferrara, D. The Progression of Geographic Atrophy Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 369–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machida, A.; Suzuki, K.; Nakayama, T.; Miyagi, S.; Maekawa, Y.; Murakami, R.; Uematsu, M.; Kitaoka, T.; Oishi, A. Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Receptor Agonist Stimulation Inhibits Laser-Induced Choroidal Neovascularization by Suppressing Intraocular Inflammation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2025, 66, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, K.C.; Joo, J.H.; Kim, S.; Shaia, J.; Kaelber, D.C.; Singh, R.; Talcott, K.E.; Rachitskaya, A.V. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Impact on Chronic Ocular Disease Including Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, S.A.; Davila, N.; Shields, C.; Bineshfar, N.; Banaee, T.; Williams, B.K., Jr. Impact of GLP-1 receptor agonists for type 2 diabetes mellitus on the development and progression of age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, A.S.; Paredes, A.A., 3rd; Young, B.K. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Age-Related Macular Degeneration. JAMA Ophthalmol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, A.S.; Paredes, A.A., 3rd; Ahuja, S.A.; Young, B.K. Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonist Use and Risk of Cataract Development. Am J Ophthalmol 2026, 281, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seve, P.; Cacoub, P.; Bodaghi, B.; Trad, S.; Sellam, J.; Bellocq, D.; Bielefeld, P.; Sene, D.; Kaplanski, G.; Monnet, D.; et al. Uveitis: Diagnostic work-up. A literature review and recommendations from an expert committee. Autoimmun Rev 2017, 16, 1254–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, N.; Srivastava, S.K.; Schulgit, M.J.; Nowacki, A.S.; Kaelber, D.C.; Sharma, S. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Risk of Uveitis. JAMA Ophthalmol 2025, 143, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntentakis, D.P.; Correa, V.; Ntentaki, A.M.; Delavogia, E.; Narimatsu, T.; Efstathiou, N.E.; Vavvas, D.G. Effects of newer-generation anti-diabetics on diabetic retinopathy: a critical review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2024, 262, 717–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Natt, N.K.; Nim, D.K. Association between glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists and risk of diabetic retinopathy: a disproportionality analysis using FDA adverse event reporting system data. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 2025, 20, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, P.; Simo, R.; Lovestam-Adrian, M.; Pearce, I.; Bain, S.C.; Dinah, C.; Davies, S.J.; Strain, W.D.; Burgess, P.; Gamble, A.; et al. Addressing the risk of ocular complications of GLP-1RAs; a multi-disciplinary expert consensus. Diabetes Obes Metab 2025, 27, 7535–7543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hathaway, J.T.; Shah, M.P.; Hathaway, D.B.; Zekavat, S.M.; Krasniqi, D.; Gittinger, J.W., Jr.; Cestari, D.; Mallery, R.; Abbasi, B.; Bouffard, M.; et al. Risk of Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy in Patients Prescribed Semaglutide. JAMA Ophthalmol 2024, 142, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, C.X.; Hribar, M.; Baxter, S.; Goetz, K.; Swaminathan, S.S.; Flowers, A.; Brown, E.N.; Toy, B.; Xu, B.; Chen, J.; et al. Semaglutide and Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy. JAMA Ophthalmol 2025, 143, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonsen, E.; Lund, L.C.; Ernst, M.T.; Hjellvik, V.; Hegedus, L.; Hamann, S.; Jorstad, O.K.; Gulseth, H.L.; Karlstad, O.; Pottegard, A. Use of semaglutide and risk of non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy: A Danish-Norwegian cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2025, 27, 3094–3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauslund, J.; Taha, A.A.; Molander, L.D.; Kawasaki, R.; Moller, S.; Hojlund, K.; Stokholm, L. Once-weekly semaglutide doubles the five-year risk of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy in a Danish cohort of 424,152 persons with type 2 diabetes. Int J Retina Vitreous 2024, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azab, M.; Pasina, L. Semaglutide: Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy in the FDA adverse event reporting system - A disproportionality analysis. Obes Res Clin Pract 2025, 19, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Huang, W.; Xie, Y.; Shen, H.; Liu, M.; Wu, X. Risk of ophthalmic adverse drug reactions in patients prescribed glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: a pharmacovigilance study based on the FDA adverse event reporting system database. Endocrine 2025, 88, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, M.; Kwan, A.T.H.; Mihalache, A.; Popovic, M.M.; Nanji, K.; Xie, J.S.; Feo, A.; Rabinovitch, D.; Shor, R.; Sadda, S.; et al. Association of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists With Optic Nerve and Retinal Adverse Events: A Population-Based Observational Study Across 180 Countries. Am J Ophthalmol 2025, 277, 148–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Volkow, N.D.; Kaelber, D.C.; Xu, R. Semaglutide or Tirzepatide and Optic Nerve and Visual Pathway Disorders in Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA Netw Open 2025, 8, e2526327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.C.; Pan, S.Y.; Sheen, Y.J.; Lin, J.F.; Lin, C.H.; Lin, H.J.; Wang, I.J.; Weng, C.H. Association between Semaglutide and Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy: A Multinational Population-Based Study. Ophthalmology 2025, 132, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natividade, G.R.; Spiazzi, B.F.; Baumgarten, M.W.; Bassotto, C.; Pereira, A.A.; Fraga, B.L.; Scalco, B.G.; Mattes, N.R.; Lavinsky, D.; Kramer, C.K.; et al. Ocular Adverse Events With Semaglutide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol 2025, 143, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mechanisms of Actions |

Ocular Targets |

Molecular Pathways |

Molecular Effectors |

Functional Outcomes | Ocular Disease |

GLP-1 RAs | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroprotection (RGC survival) | RGCs, Amacrine cells |

GLP-1R→cAMP/ PKA, PI3K/Akt, ERK1/2; modulation of Ca2+ channels; GABAergic tone |

↑BDNF signaling; ERK1/2–HDAC6 axis (axonal transport); PINK1/Parkin mitophagy; | Resilience to excitotoxic/ ischemic stress; preserved axoplasmic flow |

Glaucoma (RGC loss), optic neuropathy, DR |

Exenatide, liraglutide, semaglutide |

[24,25] |

|

Mitochondrial quality control |

RGCs, photo- receptors |

AMPK→PINK1/ Parkin; Mitophagy; ERK1/2–HDAC6 |

↑Mitophagy; ↓damaged mitochondria; stabilized mitochondrial trafficking; |

Sustained ATP; ↓ROS-induced apoptosis | Glaucoma, DR, AMD | Exenatide, liraglutide, semaglutide | [26,27] |

| Endothelial barrier stabilization | Retinal vascular endothelium; pericytes |

PI3K/Akt; Rac1/cytoskeletal junctions | ↑Tight-junction proteins (occludin/ claudin-5); ↓leukostasis |

Preserved BRB; ↓vascular leakage & edema |

DME; ischemic retinopathies |

Liraglutide, dulaglutide | [28,29] |

|

Anti-angiogenic responses |

Endothelium; RPE |

Indirect VEGF modulation; HIF-1α restraint | ↓VEGF/VEGFR signaling; ↓endothelial proliferation |

↓Pathologic neovascularization |

PDR, nAMD | Class | [30,31] |

| Microglial & macroglial modulation | Microglia, Müller glia | cAMP/PKA; NF-κB and NLRP3 inhibition | ↓TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6; microglial deactivation | ↓Neuroinflammation; ↓secondary neuronal damage |

DR, AMD, glaucoma | Class | [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] |

|

Antioxidant defense |

Neurons; Endothelium; RPE |

AMPK/Nrf2 activation |

↑SOD, ↑GSH; ↓NADPH oxidase activity |

↓ROS load; Protection from hyperglycemia- induced oxidative stress |

DR, AMD | Class | [45,46,47] |

|

Neurovascular coupling & IOP control |

TM/uveoscleral outflow; optic nerve head | cAMP signaling; nitric-oxide (NO) pathways |

Potential outflow enhancement; vascular autoregulation | ↓IOP (in some reports); optic nerve perfusion support | Glaucoma | Class | [49,50,51] |

|

Immune modulation beyond retina |

Uveal tract, choroid | Systemic + local anti-inflammation | ↓Leukocyte recruitment |

↓Risk of ocular inflammation | Uveitis (noninfectious) | Class | [31,32,33,34] |

|

Systemic metabolic context |

Retina, choroid |

Rapid HbA1c reduction; BP/volume shifts |

Transient perfusion stress |

“Early worsening” of DR in vulnerable eyes |

DR safety concerns |

Class | [63,64] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).