Submitted:

14 April 2024

Posted:

24 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

Patents

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sandberg MA, Rosner B, Weigel-DiFranco C, Dryja TP, Berson EL. Disease course of patients with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa due to RPGR gene mutations. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2007;48(3):1298-304. [CrossRef]

- Konieczka K, Flammer AJ, Todorova M, Meyer P, Flammer J. Retinitis pigmentosa and ocular blood flow. EPMA J. 2012;3(1):17-. [CrossRef]

- Russell S, Bennett J, Wellman JA, Chung DC, Yu ZF, Tillman A, et al. Efficacy and safety of voretigene neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) in patients with RPE65-mediated inherited retinal dystrophy: a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England). 2017;390(10097):849-60. [CrossRef]

- Linsenmeier RA, Padnick-Silver L. Metabolic dependence of photoreceptors on the choroid in the normal and detached retina. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2000;41(10):3117-23.

- Langham ME, Kramer T. Decreased choroidal blood flow associated with retinitis pigmentosa. Eye (London, England). 1990;4 ( Pt 2):374-81. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Harrison JM, Nateras OS, Chalfin S, Duong TQ. Decreased retinal-choroidal blood flow in retinitis pigmentosa as measured by MRI. Documenta ophthalmologica Advances in ophthalmology. 2013;126(3):187-97. [CrossRef]

- Abdolrahimzadeh S, Di Pippo M, Ciancimino C, Di Staso F, Lotery AJ. Choroidal vascularity index and choroidal thickness: potential biomarkers in retinitis pigmentosa. Eye. 2023;37(9):1766-73. [CrossRef]

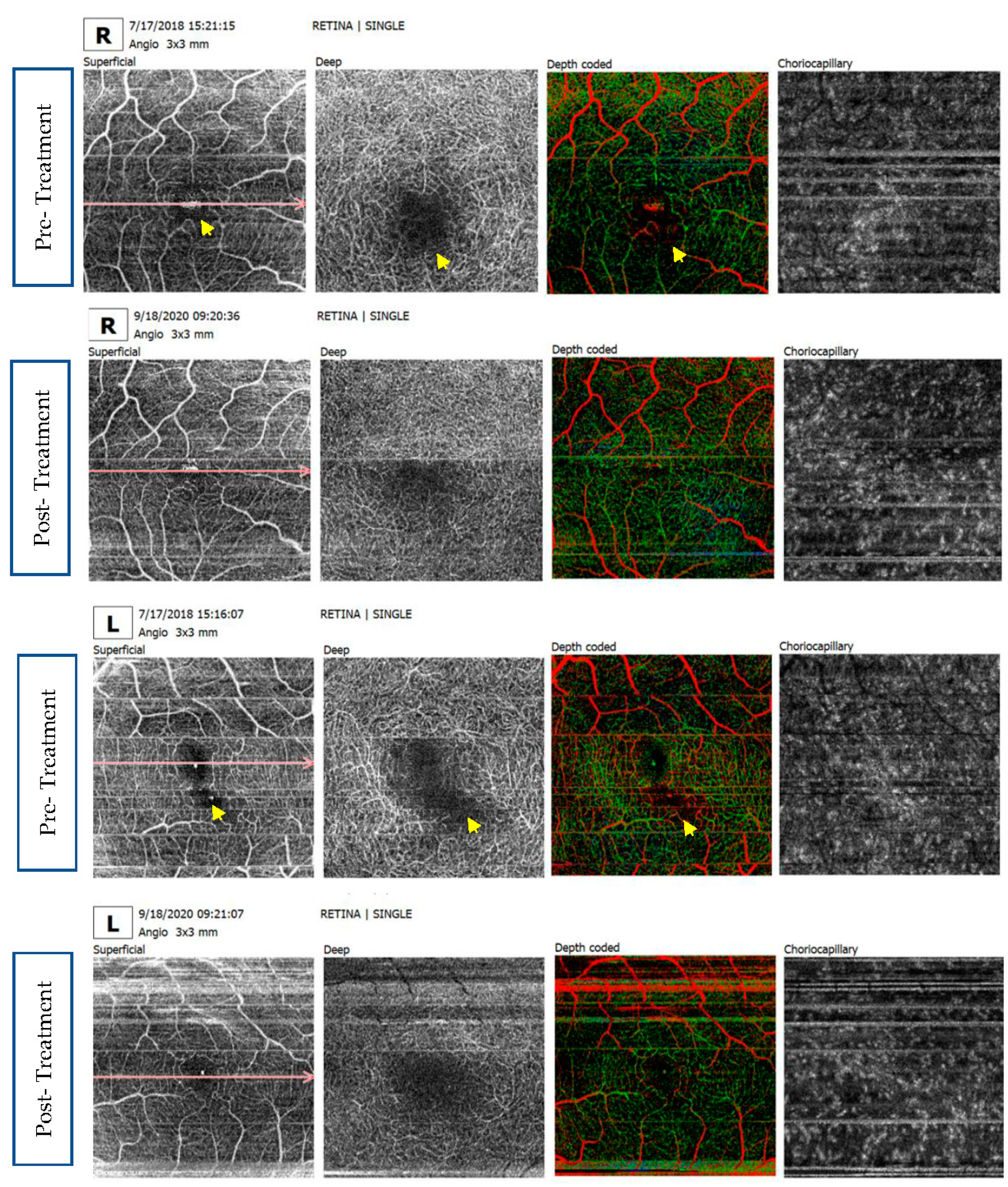

- Shen C, Li Y, Wang Q, Chen YN, Li W, Wei WB. Choroidal vascular changes in retinitis pigmentosa patients detected by optical coherence tomography angiography. BMC ophthalmology. 2020;20(1):384. [CrossRef]

- Cetin EN, Parca O, Akkaya HS, Pekel G. Association of retinal biomarkers and choroidal vascularity index on optical coherence tomography using binarization method in retinitis pigmentosa. Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology = Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. 2020;258(1):23-30. [CrossRef]

- Falsini B, Anselmi GM, Marangoni D, D'Esposito F, Fadda A, Di Renzo A, et al. Subfoveal choroidal blood flow and central retinal function in retinitis pigmentosa. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2011;52(2):1064-9. [CrossRef]

- Grunwald JE, Maguire AM, Dupont J. Retinal hemodynamics in retinitis pigmentosa. American journal of ophthalmology. 1996;122(4):502-8. [CrossRef]

- Cellini M, Strobbe E, Gizzi C, Campos EC. ET-1 plasma levels and ocular blood flow in retinitis pigmentosa. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology. 2010;88(6):630-5. [CrossRef]

- Wolf S, Pöstgens H, Bertram B, Schulte K, Teping C, Reim M. [Hemodynamic findings in patients with retinitis pigmentosa]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 1991;199(5):325-9.

- Vingolo EM, Lupo S, Grenga PL, Salvatore S, Zinnamosca L, Cotesta D, et al. Endothelin-1 plasma concentrations in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Regulatory peptides. 2010;160(1-3):64-7. [CrossRef]

- Cellini M, Santiago L, Versura P, Caramazza R. Plasma levels of endothelin-1 in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmologica Journal international d'ophtalmologie International journal of ophthalmology Zeitschrift fur Augenheilkunde. 2002;216(4):265-8. [CrossRef]

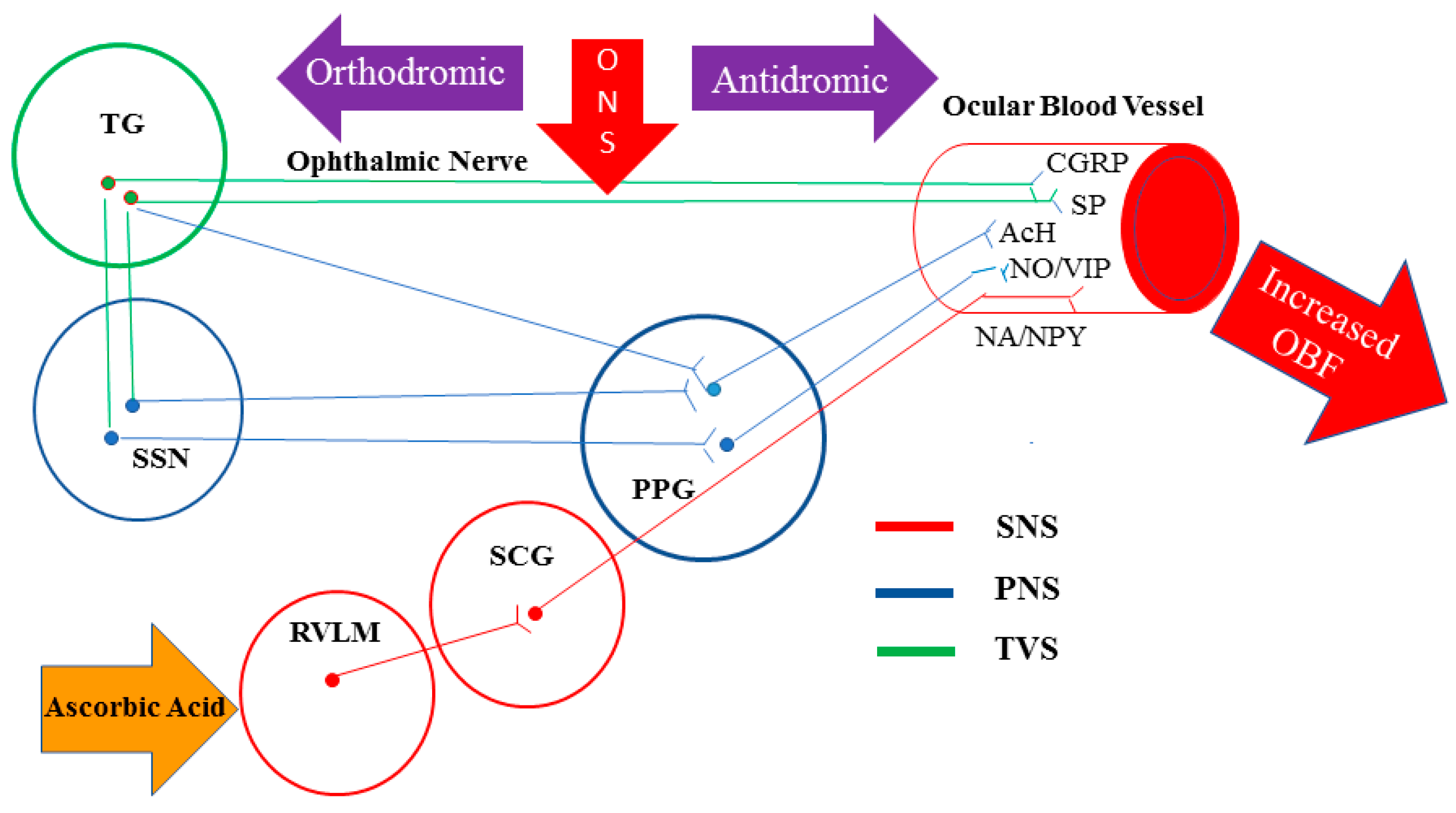

- Reiner A, Fitzgerald MEC, Del Mar N, Li C. Neural control of choroidal blood flow. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2018;64:96-130. [CrossRef]

- McDougal DH, Gamlin PD. Autonomic control of the eye. Comprehensive Physiology. 2015;5(1):439-73. [CrossRef]

- Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L, Ekman R. Release of vasoactive peptides in the extracerebral circulation of humans and the cat during activation of the trigeminovascular system. Annals of neurology. 1988;23(2):193-6. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki N, Hardebo JE, Owman C. Trigeminal fibre collaterals storing substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide associate with ganglion cells containing choline acetyltransferase and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in the sphenopalatine ganglion of the rat. An axon reflex modulating parasympathetic ganglionic activity? Neuroscience. 1989;30(3):595-604. [CrossRef]

- Hosaka F, Yamamoto M, Cho KH, Jang HS, Murakami G, Abe S. Human nasociliary nerve with special reference to its unique parasympathetic cutaneous innervation. Anatomy & cell biology. 2016;49(2):132-7. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki N, Hardebo JE, Owman C. Origins and pathways of cerebrovascular nerves storing substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide in rat. Neuroscience. 1989;31(2):427-38. [CrossRef]

- Lambert GA, Bogduk N, Goadsby PJ, Duckworth JW, Lance JW. Decreased carotid arterial resistance in cats in response to trigeminal stimulation. Journal of neurosurgery. 1984;61(2):307-15. [CrossRef]

- Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L. The trigeminovascular system and migraine: studies characterizing cerebrovascular and neuropeptide changes seen in humans and cats. Annals of neurology. 1993;33(1):48-56. [CrossRef]

- Stjernschantz J, Geijer C, Bill A. Electrical stimulation of the fifth cranial nerve in rabbits: effects on ocular blood flow, extravascular albumin content and intraocular pressure. Experimental eye research. 1979;28(2):229-38. [CrossRef]

- Bill A, Nilsson SF. Control of ocular blood flow. Journal of cardiovascular pharmacology. 1985;7 Suppl 3:S96-102.

- Kim JH, Jung Y, Kim BS, Kim SH. Stem cell recruitment and angiogenesis of neuropeptide substance P coupled with self-assembling peptide nanofiber in a mouse hind limb ischemia model. Biomaterials. 2013;34(6):1657-68. [CrossRef]

- Lee D, Hong HS. Substance P Alleviates Retinal Pigment Epithelium Dysfunction Caused by High Glucose-Induced Stress. Life (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;13(5). [CrossRef]

- Ou K, Mertsch S, Theodoropoulou S, Wu J, Liu J, Copland DA, et al. Restoring retinal neurovascular health via substance P. Experimental cell research. 2019;380(2):115-23. [CrossRef]

- Backman LJ, Eriksson DE, Danielson P. Substance P reduces TNF-α-induced apoptosis in human tenocytes through NK-1 receptor stimulation. British journal of sports medicine. 2014;48(19):1414-20. [CrossRef]

- Yang J-H, Guo Z, Zhang T, Meng XX, Xie L-S. Restoration of endogenous substance P is associated with inhibition of apoptosis of retinal cells in diabetic rats. Regulatory peptides. 2013;187:12-6. [CrossRef]

- Yoo K, Son BK, Kim S, Son Y, Yu S-Y, Hong HS. Substance P prevents development of proliferative vitreoretinopathy in mice by modulating TNF-α. Mol Vis. 2017;23:933-43.

- Lim JE, Chung E, Son Y. A neuropeptide, Substance-P, directly induces tissue-repairing M2 like macrophages by activating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway even in the presence of IFNγ. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):9417. [CrossRef]

- Baek SM, Yu SY, Son Y, Hong HS. Substance P promotes the recovery of oxidative stress-damaged retinal pigmented epithelial cells by modulating Akt/GSK-3β signaling. Molecular vision. 2016;22:1015-23.

- Kim DY, Piao J, Hong HS. Substance-P Inhibits Cardiac Microvascular Endothelial Dysfunction Caused by High Glucose-Induced Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland). 2021;10(7). [CrossRef]

- Piao J, Hong HS, Son Y. Substance P ameliorates tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced endothelial cell dysfunction by regulating eNOS expression in vitro. Microcirculation (New York, NY : 1994). 2018;25(3):e12443. [CrossRef]

- Campochiaro PA, Iftikhar M, Hafiz G, Akhlaq A, Tsai G, Wehling D, et al. Oral N-acetylcysteine improves cone function in retinitis pigmentosa patients in phase I trial. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2020;130(3):1527-41. [CrossRef]

- Henry PT, Chandy MJ. Effect of ascorbic acid on infarct size in experimental focal cerebral ischaemia and reperfusion in a primate model. Acta neurochirurgica. 1998;140(9):977-80. [CrossRef]

- Ranjan A, Theodore D, Haran RP, Chandy MJ. Ascorbic acid and focal cerebral ischaemia in a primate model. Acta neurochirurgica. 1993;123(1-2):87-91. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Agus DB, Winfree CJ, Kiss S, Mack WJ, McTaggart RA, et al. Dehydroascorbic acid, a blood-brain barrier transportable form of vitamin C, mediates potent cerebroprotection in experimental stroke. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(20):11720-4. [CrossRef]

- Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Spoelstra-de Man AM, de Waard MC. Vitamin C revisited. Critical care (London, England). 2014;18(4):460. [CrossRef]

- Rose RC, Bode AM. Ocular ascorbate transport and metabolism. Comparative biochemistry and physiology A, Comparative physiology. 1991;100(2):273-85. [CrossRef]

- Hosoya K, Minamizono A, Katayama K, Terasaki T, Tomi M. Vitamin C transport in oxidized form across the rat blood-retinal barrier. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2004;45(4):1232-9. [CrossRef]

- Jackson TS, Xu A, Vita JA, Keaney JF, Jr. Ascorbate prevents the interaction of superoxide and nitric oxide only at very high physiological concentrations. Circulation research. 1998;83(9):916-22. [CrossRef]

- Bruno RM, Daghini E, Ghiadoni L, Sudano I, Rugani I, Varanini M, et al. Effect of acute administration of vitamin C on muscle sympathetic activity, cardiac sympathovagal balance, and baroreflex sensitivity in hypertensive patients. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2012;96(2):302-8. [CrossRef]

- SWOG:. Cancer Research Network – Cancer Research and Biostatistics. https://stattoolscraborg/Calculators/oneArmSurvivalColoredhtml.

- Thenappan A, Nanda A, Lee CS, Lee SY. Retinitis Pigmentosa Masquerades: Case Series and Review of the Literature. Journal of clinical medicine. 2023;12(17). [CrossRef]

- Oh R, Bae K, Yoon CK, Park UC, Park KH, Lee EK. Quantitative microvascular analysis in different stages of retinitis pigmentosa using optical coherence tomography angiography. Scientific reports. 2024;14(1):4688. [CrossRef]

- Ito N, Miura G, Shiko Y, Kawasaki Y, Baba T, Yamamoto S. Progression Rate of Visual Function and Affecting Factors at Different Stages of Retinitis Pigmentosa. BioMed research international. 2022;2022:7204954. [CrossRef]

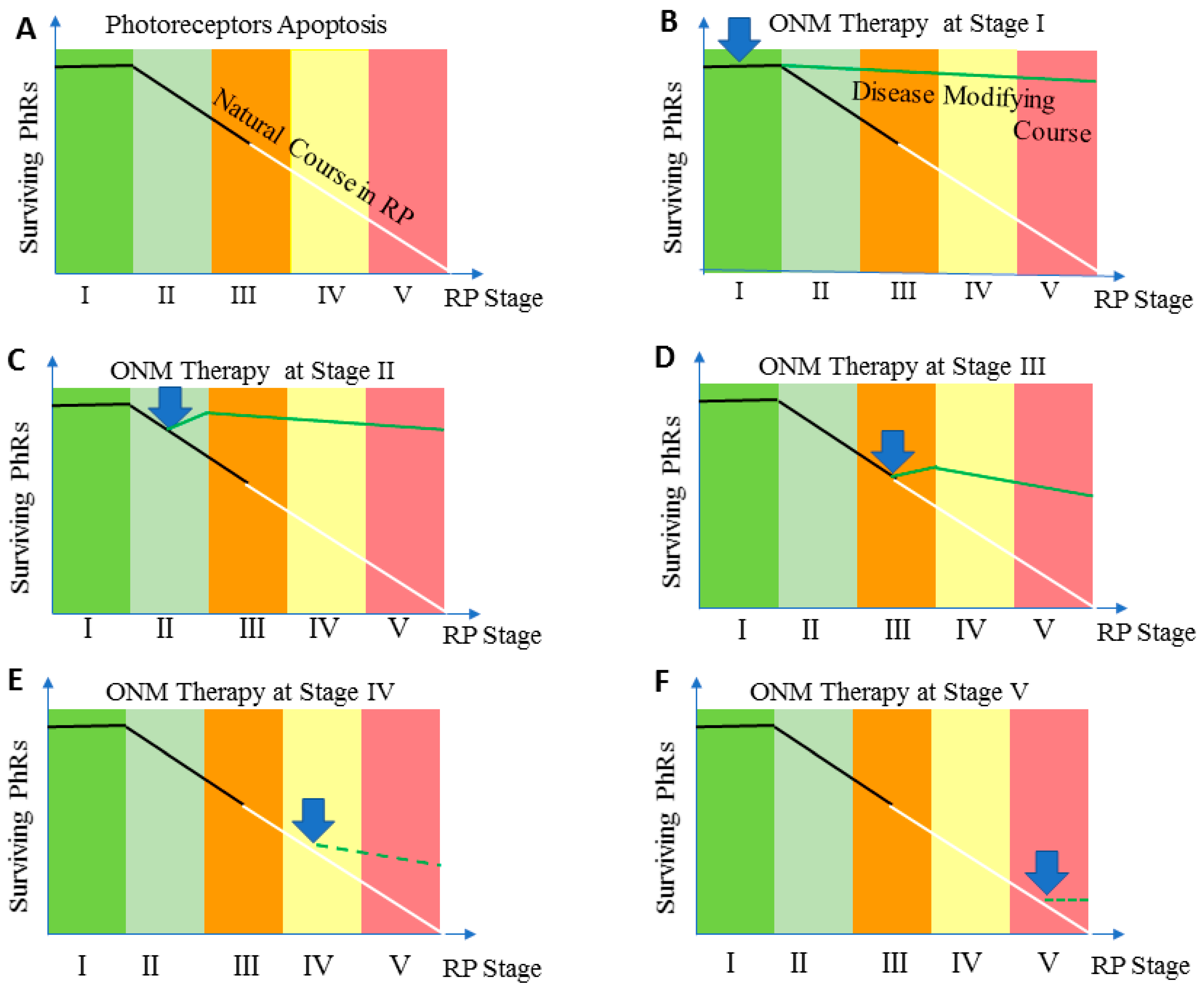

- Iftikhar M, Lemus M, Usmani B, Campochiaro PA, Sahel JA, Scholl HPN, et al. Classification of disease severity in retinitis pigmentosa. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2019;103(11):1595-9. [CrossRef]

- Oner A, Sinim Kahraman N. A New Classification for Retinitis Pigmentosa Including Multifocal Electroretinography to Evaluate the Disease Severity. Open Journal of Ophthalmology. 2023;13:37-47. [CrossRef]

- Smith HB, Chandra A, Zambarakji H. Grading severity in retinitis pigmentosa using clinical assessment, visual acuity, perimetry and optical coherence tomography. International ophthalmology. 2013;33(3):237-44. [CrossRef]

- O'Neill JJ, McKay GJ, Simpson DA, Silvestri G. Retinitis Pigmentosa Assessment Severity Scale (RPASS) for Use in Scientific Analysis and Classification of Disease Progression. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2006;47(13):1419-.

- Milam AH, Li ZY, Fariss RN. Histopathology of the human retina in retinitis pigmentosa. Progress in retinal and eye research. 1998;17(2):175-205. [CrossRef]

- Li ZY, Possin DE, Milam AH. Histopathology of bone spicule pigmentation in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(5):805-16. [CrossRef]

- Ma Y, Kawasaki R, Dobson LP, Ruddle JB, Kearns LS, Wong TY, et al. Quantitative Analysis of Retinal Vessel Attenuation in Eyes with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2012;53(7):4306-14. [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa S, Oishi A, Ogino K, Makiyama Y, Kurimoto M, Yoshimura N. Association of retinal vessel attenuation with visual function in eyes with retinitis pigmentosa. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, NZ). 2014;8:1487-93. [CrossRef]

- Albakri AS, Al-Shahwan E, Nowilaty SR. Correlation Of Retinitis Pigmentosa Disease Stage With Orbital Color Doppler Imaging. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2012;53(14):6846-.

- Lesko LJ, Atkinson AJ, Jr. Use of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in drug development and regulatory decision making: criteria, validation, strategies. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2001;41:347-66. [CrossRef]

- Medeiros FA. Biomarkers and Surrogate Endpoints: Lessons Learned From Glaucoma. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2017;58(6):Bio20-bio6. [CrossRef]

- Owsley C, McGwin G, Jr., Scilley K, Kallies K. Development of a questionnaire to assess vision problems under low luminance in age-related maculopathy. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2006;47(2):528-35. [CrossRef]

- Reiner A, Fitzgerald MC, C. L. Neural Control of Ocular Blood Flow. Editors. Ocular Blood Flow. Berlin Heidelberge:springer; 2012.

- Hiraba H, Inoue M, Gora K, Sato T, Nishimura S, Yamaoka M, et al. Facial vibrotactile stimulation activates the parasympathetic nervous system: study of salivary secretion, heart rate, pupillary reflex, and functional near-infrared spectroscopy activity. BioMed research international. 2014;2014:910812. [CrossRef]

- Li ZY, Kljavin IJ, Milam AH. Rod photoreceptor neurite sprouting in retinitis pigmentosa. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1995;15(8):5429-38.

- Wang W, Lee SJ, Scott PA, Lu X, Emery D, Liu Y, et al. Two-Step Reactivation of Dormant Cones in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Cell reports. 2016;15(2):372-85. [CrossRef]

- Wang W, Kini A, Wang Y, Liu T, Chen Y, Vukmanic E, et al. Metabolic Deregulation of the Blood-Outer Retinal Barrier in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Cell reports. 2019;28(5):1323-34.e4. [CrossRef]

- Toto L, Borrelli E, Mastropasqua R, Senatore A, Di Antonio L, Di Nicola M, et al. Macular Features in Retinitis Pigmentosa: Correlations Among Ganglion Cell Complex Thickness, Capillary Density, and Macular Function. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2016;57(14):6360-6. [CrossRef]

- Hayreh SS. In vivo choroidal circulation and its watershed zones. Eye (London, England). 1990;4 ( Pt 2):273-89. [CrossRef]

- Punzo C, Kornacker K, Cepko CL. Stimulation of the insulin/mTOR pathway delays cone death in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Nature neuroscience. 2009;12(1):44-52. [CrossRef]

- Shigesada N, Shikada N, Shirai M, Toriyama M, Higashijima F, Kimura K, et al. Combination of blockade of endothelin signalling and compensation of IGF1 expression protects the retina from degeneration. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2024;81(1):51. [CrossRef]

- Kedzierski RM, Yanagisawa M. Endothelin system: the double-edged sword in health and disease. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2001;41:851-76. [CrossRef]

- Derella CC, Tingen MS, Blanks A, Sojourner SJ, Tucker MA, Thomas J, et al. Smoking cessation reduces systemic inflammation and circulating endothelin-1. Scientific reports. 2021;11(1):24122. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi Y, Watanabe S, Shirai M, Yamashiro C, Ogata T, Higashijima F, et al. Light-dependent induction of Edn2 expression and attenuation of retinal pathology by endothelin receptor antagonists in Prominin-1- deficient mice. 2020.

- Dellett M, Sasai N, Nishide K, Becker S, Papadaki V, Limb GA, et al. Genetic background and light-dependent progression of photoreceptor cell degeneration in Prominin-1 knockout mice. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2014;56(1):164-76. [CrossRef]

- Oishi A, Noda K, Birtel J, Miyake M, Sato A, Hasegawa T, et al. Effect of smoking on macular function and retinal structure in retinitis pigmentosa. Brain communications. 2020;2(2):fcaa117. [CrossRef]

- Zhu X, Lin X, Xu Y, Li N, Zhou Q, Sun X, et al. Effect of Dual Endothelin Receptor Antagonist on a Retinal Degeneration Animal Model by Regulating Choroidal Microvascular Morphology. Journal of ophthalmology. 2021;2021:5688300. [CrossRef]

- Kirkby NS, Hadoke PW, Bagnall AJ, Webb DJ. The endothelin system as a therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease: great expectations or bleak house? British journal of pharmacology. 2008;153(6):1105-19. [CrossRef]

- De Mey J, Compeer MG, Meens MJJMCP. Endothelin-1, an endogenous irreversible agonist in search of an allosteric inhibitor. 2009;1:246-57. [CrossRef]

- Meens MJ, Compeer MG, Hackeng TM, van Zandvoort MA, Janssen BJ, De Mey JG. Stimuli of sensory-motor nerves terminate arterial contractile effects of endothelin-1 by CGRP and dissociation of ET-1/ET(A)-receptor complexes. PloS one. 2010;5(6):e10917. [CrossRef]

- Hilal-Dandan R, Villegas S, Gonzalez A, Brunton LL. The quasi-irreversible nature of endothelin binding and G protein-linked signaling in cardiac myocytes. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1997;281(1):267-73. [CrossRef]

- Meens MJPMT, Mattheij NJA, Nelissen J, Lemkens P, Compeer MG, Janssen BJA, et al. Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Terminates Long-Lasting Vasopressor Responses to Endothelin 1 In Vivo. Hypertension. 2011;58(1):99-106. [CrossRef]

- Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: molecular and biological aspects. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 1999;237:1-30. [CrossRef]

- Salom D, Diaz-Llopis M, García-Delpech S, Udaondo P, Sancho-Tello M, Romero FJ. Aqueous humor levels of vascular endothelial growth factor in retinitis pigmentosa. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2008;49(8):3499-502. [CrossRef]

- Lv YX, Zhong S, Tang H, Luo B, Chen SJ, Chen L, et al. VEGF-A and VEGF-B Coordinate the Arteriogenesis to Repair the Infarcted Heart with Vagus Nerve Stimulation. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology. 2018;48(2):433-49. [CrossRef]

- Luo B, Wu Y, Liu SL, Li XY, Zhu HR, Zhang L, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation optimized cardiomyocyte phenotype, sarcomere organization and energy metabolism in infarcted heart through FoxO3A-VEGF signaling. Cell death & disease. 2020;11(11):971. [CrossRef]

- Rogers RC, Kita H, Butcher LL, Novin D. Afferent projections to the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Brain research bulletin. 1980;5(4):365-73. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Dana R, Yin J. Sensory neurons directly promote angiogenesis in response to inflammation via substance P signaling. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2020;34(5):6229-43. [CrossRef]

- Ziche M, Morbidelli L, Pacini M, Geppetti P, Alessandri G, Maggi CA. Substance P stimulates neovascularization in vivo and proliferation of cultured endothelial cells. Microvascular research. 1990;40(2):264-78. [CrossRef]

- Kohara H, Tajima S, Yamamoto M, Tabata Y. Angiogenesis induced by controlled release of neuropeptide substance P. Biomaterials. 2010;31(33):8617-25. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida N, Ikeda Y, Notomi S, Ishikawa K, Murakami Y, Hisatomi T, et al. Laboratory evidence of sustained chronic inflammatory reaction in retinitis pigmentosa. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(1):e5-12. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Chiluwal A, Afridi A, Chaung W, Powell K, Yang WL, et al. Trigeminal Nerve Stimulation: A Novel Method of Resuscitation for Hemorrhagic Shock. Critical care medicine. 2019;47(6):e478-e84. [CrossRef]

- Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, Yang H, Botchkina GI, Watkins LR, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature. 2000;405(6785):458-62. [CrossRef]

- Komeima K, Rogers BS, Lu L, Campochiaro PA. Antioxidants reduce cone cell death in a model of retinitis pigmentosa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(30):11300-5. [CrossRef]

- Taddei S, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Magagna A, Salvetti A. Vitamin C improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation by restoring nitric oxide activity in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1998;97(22):2222-9. [CrossRef]

- Gupta N, Brown KE, Milam AH. Activated microglia in human retinitis pigmentosa, late-onset retinal degeneration, and age-related macular degeneration. Experimental eye research. 2003;76(4):463-71. [CrossRef]

- Zhou T, Huang Z, Sun X, Zhu X, Zhou L, Li M, et al. Microglia Polarization with M1/M2 Phenotype Changes in rd1 Mouse Model of Retinal Degeneration. Frontiers in neuroanatomy. 2017;11:77. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L, Zabel MK, Wang X, Ma W, Shah P, Fariss RN, et al. Microglial phagocytosis of living photoreceptors contributes to inherited retinal degeneration. EMBO molecular medicine. 2015;7(9):1179-97. [CrossRef]

- Blank T, Goldmann T, Koch M, Amann L, Schön C, Bonin M, et al. Early Microglia Activation Precedes Photoreceptor Degeneration in a Mouse Model of CNGB1-Linked Retinitis Pigmentosa. Frontiers in immunology. 2017;8:1930. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Cui X, Jauregui R, Park KS, Justus S, Tsai YT, et al. Genetic Rescue Reverses Microglial Activation in Preclinical Models of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2018;26(8):1953-64. [CrossRef]

- Jiang MH, Chung E, Chi GF, Ahn W, Lim JE, Hong HS, et al. Substance P induces M2-type macrophages after spinal cord injury. Neuroreport. 2012;23(13):786-92. [CrossRef]

- Ahn W, Chi G, Kim S, Son Y, Zhang M. Substance P Reduces Infarct Size and Mortality After Ischemic Stroke, Possibly Through the M2 Polarization of Microglia/Macrophages and Neuroprotection in the Ischemic Rat Brain. Cellular and molecular neurobiology. 2023;43(5):2035-52. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Zeng R, Wang Y, Huang W, Hu B, Zhu G, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance microglia M2 polarization and attenuate neuroinflammation through TSG-6. Brain Res. 2019;1724:146422. [CrossRef]

- Jolly JK, Wagner SK, Martus P, MacLaren RE, Wilhelm B, Webster AR, et al. Transcorneal Electrical Stimulation for the Treatment of Retinitis Pigmentosa: A Multicenter Safety Study of the OkuStim® System (TESOLA-Study). Ophthalmic research. 2020;63(3):234-43. [CrossRef]

- Miura G, Sugawara T, Kawasaki Y, Tatsumi T, Nizawa T, Baba T, et al. Clinical Trial to Evaluate Safety and Efficacy of Transdermal Electrical Stimulation on Visual Functions of Patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Scientific reports. 2019;9(1):11668. [CrossRef]

- de Rossi F, Guidobaldi M, Turco S, Amore F. Transorbital electrical stimulation in retinitis pigmentosa. Better results joining visual pattern stimulation? Brain stimulation. 2020;13(5):1173-4. [CrossRef]

- Iftinca M, Altier C. The cool things to know about TRPM8! Channels (Austin, Tex). 2020;14(1):413-20. [CrossRef]

- Keh SM, Facer P, Yehia A, Sandhu G, Saleh HA, Anand P. The menthol and cold sensation receptor TRPM8 in normal human nasal mucosa and rhinitis. Rhinology. 2011;49(4):453-7.

- Bae JY, Kim JH, Cho YS, Mah W, Bae YC. Quantitative analysis of afferents expressing substance P, calcitonin gene-related peptide, isolectin B4, neurofilament 200, and Peripherin in the sensory root of the rat trigeminal ganglion. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2015;523(1):126-38. [CrossRef]

- Hong HS, Kim S, Nam S, Um J, Kim YH, Son Y. Effect of substance P on recovery from laser-induced retinal degeneration. Wound repair and regeneration : official publication of the Wound Healing Society [and] the European Tissue Repair Society. 2015;23(2):268-77. [CrossRef]

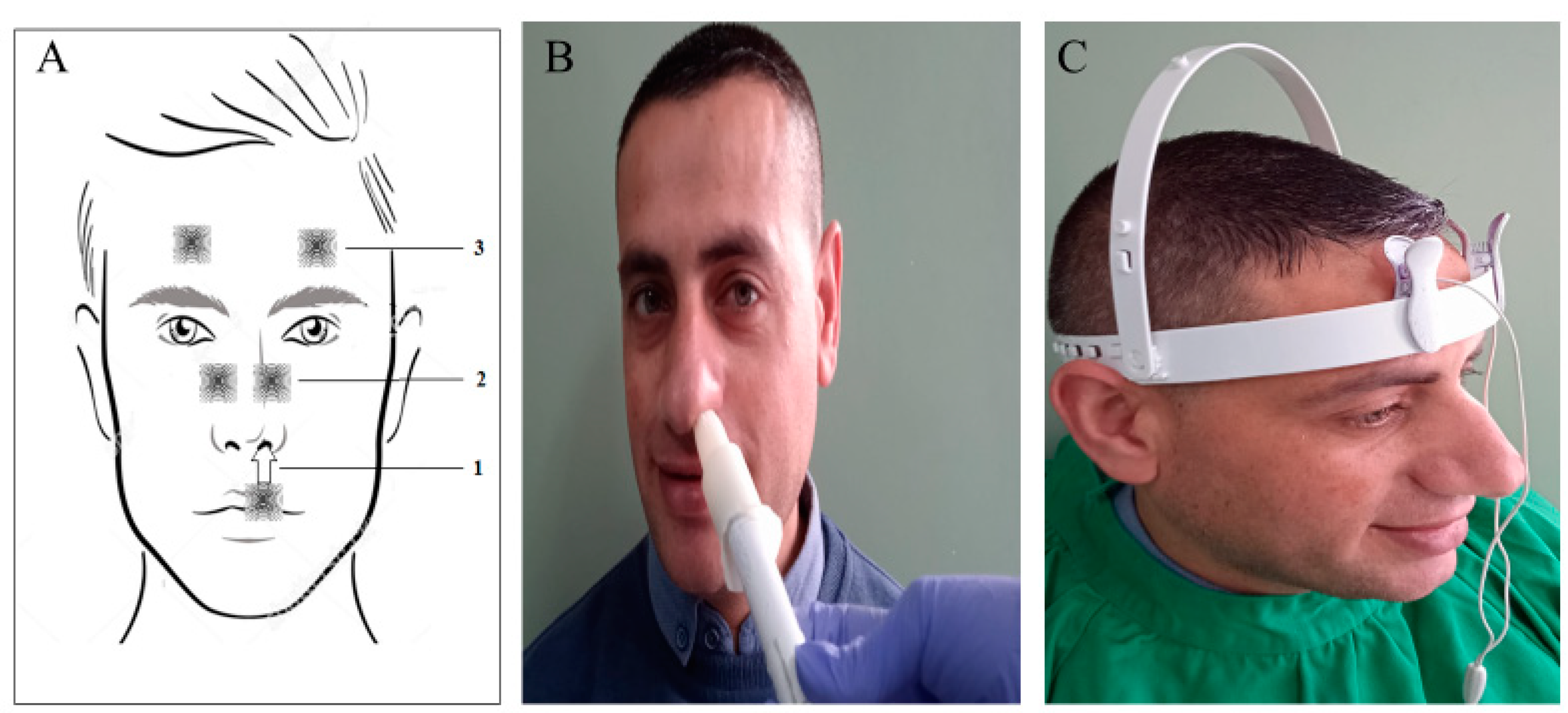

- Scheibe M, van Thriel C, Hummel T. Responses to trigeminal irritants at different locations of the human nasal mucosa. The Laryngoscope. 2008;118(1):152-5. [CrossRef]

- Atalay B, Bolay H, Dalkara T, Soylemezoglu F, Oge K, Ozcan OE. Transcorneal stimulation of trigeminal nerve afferents to increase cerebral blood flow in rats with cerebral vasospasm: a noninvasive method to activate the trigeminovascular reflex. Journal of neurosurgery. 2002;97(5):1179-83. [CrossRef]

- McCulloch PF, Faber KM, Panneton WM. Electrical stimulation of the anterior ethmoidal nerve produces the diving response. Brain Res. 1999;830(1):24-31. [CrossRef]

- Bittner AK, Seger K, Salveson R, Kayser S, Morrison N, Vargas P, et al. Randomized controlled trial of electro-stimulation therapies to modulate retinal blood flow and visual function in retinitis pigmentosa. Acta ophthalmologica. 2018;96(3):e366-e76. [CrossRef]

- Schatz A, Pach J, Gosheva M, Naycheva L, Willmann G, Wilhelm B, et al. Transcorneal Electrical Stimulation for Patients With Retinitis Pigmentosa: A Prospective, Randomized, Sham-Controlled Follow-up Study Over 1 Year. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2017;58(1):257-69. [CrossRef]

- Kalloniatis M, Tomisich G. Amino acid neurochemistry of the vertebrate retina. Progress in retinal and eye research. 1999;18(6):811-66. [CrossRef]

- Zilberter Y, Harkany T, Holmgren CD. Dendritic release of retrograde messengers controls synaptic transmission in local neocortical networks. The Neuroscientist : a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry. 2005;11(4):334-44. [CrossRef]

- Puthussery T, Taylor WR. Functional changes in inner retinal neurons in animal models of photoreceptor degeneration. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2010;664:525-32. [CrossRef]

- Marc RE, Jones BW, Watt CB, Strettoi E. Neural remodeling in retinal degeneration. Progress in retinal and eye research. 2003;22(5):607-55. [CrossRef]

- Wang T, Pahlberg J, Cafaro J, Frederiksen R, Cooper AJ, Sampath AP, et al. Activation of Rod Input in a Model of Retinal Degeneration Reverses Retinal Remodeling and Induces Formation of Functional Synapses and Recovery of Visual Signaling in the Adult Retina. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2019;39(34):6798-810. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Rountree CM, Kare S-S, Ramkumar PK, Finan JD, Troy JB. Progress on Designing a Chemical Retinal Prosthesis. 2022;16. [CrossRef]

- Cideciyan AV, Jacobson SG, Beltran WA, Sumaroka A, Swider M, Iwabe S, et al. Human retinal gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis shows advancing retinal degeneration despite enduring visual improvement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(6):E517-25. [CrossRef]

- Aït-Ali N, Fridlich R, Millet-Puel G, Clérin E, Delalande F, Jaillard C, et al. Rod-derived cone viability factor promotes cone survival by stimulating aerobic glycolysis. Cell. 2015;161(4):817-32. [CrossRef]

- Gange WS, Sisk RA, Besirli CG, Lee TC, Havunjian M, Schwartz H, et al. Perifoveal Chorioretinal Atrophy after Subretinal Voretigene Neparvovec-rzyl for RPE65-Mediated Leber Congenital Amaurosis. Ophthalmology Retina. 2022;6(1):58-64. [CrossRef]

- Evans SR. Clinical trial structures. Journal of experimental stroke & translational medicine. 2010;3(1):8-18. [CrossRef]

| Stage | Clinical Description |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Patients experience no symptoms related to retinitis pigmentosa. Fundus examination reveals a normal-looking retina with no pigmentary changes, no visible retinal blood vessel changes, or optic nerve pallor. Classic electroretinogram findings for retinitis pigmentosa are detected |

| Stage 1 | Patients may experience mild night vision disturbance. Fundus examination reveals a normal-looking retina with no pigmentary changes, no visible retinal blood vessel changes, or optic nerve pallor. Classic electroretinogram findings for retinitis pigmentosa are detected |

| Stage II | Mild attenuation of retinal blood vessels that extend anteriorely beyond the mid periphery of the retina but not reaching ora serrata, no or mild optic disc pallor, bone spicule pigmentary changes are limited to mid-periphery of the retina. |

| Stage III | Moderate attenuation of retinal blood vessels that extend anteriorely up to mid-periphery with mild optic nerve pallor. Pigmentary changes are located at mid-periphery and extend centrally reaching the vascular arcade. |

| Stage IV | Severe attenuation of retinal blood vessels ended with the formation of a complete vascular arcade, combined with moderate optic nerve pallor. Pigmentary changes are becoming more diffuse and extend centrally to the inside of the vascular arcade, but sparing the macula. Central retinal thickness is less than 150 µ as measured by Spectral Domain Optical Coherance Tomography |

| Stage V | Very severe attenuation or complete obliteration of retinal blood vessels that ended at a short distance forming incomplete vascular arcade (≤ 4 disc diameter) from optic nerve disc. Optic pallor is remarkable and the macula is involved in pigmentary changes. Stage V is also coined to any retina with a central retinal thickness of 100 µm or less as measured by Spectral Domain Optical Coherance Tomography |

| Q | Subject | Question Text |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Night Vision | Rate how much difficulty you have seeing at night. |

| 2 | Peripheral vision | Rate how much difficulty you have in your peripheral vision at night. |

| 3 | Reading in dim light | Rate how much difficulty you have in reading menus in dimly lit restaurants or reading the newspaper/book without good lighting. |

| 4 | Depth of Perception | Rate how much difficulty you have in-depth perception at night. |

| 5 | Color Vision | Rate how much difficulty you have seeing colors at night. |

| 6 | Home life | Rate how much difficulty you have seeing furniture in dimly lit rooms. |

| 7 | Social life | Rate how much difficulty you have going out to nighttime social events such as sports events, the theater, friend’s homes, church, mosque, or restaurants? |

| 8 | Parties in dim light | Rate how much difficulty seeing in candlelight? |

| 9 | Dependency on others | Rate how often you depend on others to help you because of your vision at night or under poor lighting? |

| 10 | Psychological Stress | Rate how often you are worried or concerned that you might fall at night because of your vision? |

| Character | Total cohort |

Rod Responders |

Non-Rod-Responders | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant Number | 40 (76 eyes) | 24 (60%) | 16 (40%) | |

|

Age,( Mean ±SD) Age (Median)(median; 25th,75th) Range |

28.4 ± 14.1 yrs. 24.0 yrs. (19,40) 4-55 yrs. |

23.9 ± 12.2 21.5 yrs. (16.5,32.0) 4-49 yrs. |

35.1 ± 14.3 yrs. 40.00 yrs. (21.3,47.0) 7-52 yrs. |

0.02 0.015 |

| Gender; Male/Female (males %) | 24/16 (60%) | 13/11 (54.2%) | 10/6 (62.5%) | NS |

|

Range/ Duration of night blindness (mean ±SD) (Median) |

2-46 yrs. 16.2 ± 12.3 yrs. |

2-30 yrs. 10.9 ± 6.7 yrs. 10.0 yrs |

3-46 yrs. 24.2 ± 14.6 yrs. 21.00 yrs |

0.0001 0.003 |

|

Duration of Night Blindness 0-10 10-20 >20 |

16 (100%) 14 (100%) 10 (100%) |

13(81.2%) 4 (28.6%) 1 (10%) |

3 (18.8%) 10 (71.4%) 9 (90%) |

|

|

Stage of the Disease * II, no. of patients (%) III, no. of patients/ (%) IV, no. of patients (%) V, no. of patients/ (%) |

9 (100%) 15 (100%) 11 (100%) 5 (100%) |

9 (100%) 12 (80%) 2 (18.2%) 1 (20%) |

0 (0%) 3 (20%) 9 (81.8%) 4 (80%) |

0.0001 |

|

LLQ-10 Score (mean ± SD) LLQ-10 Score (median) (median; 25th,75th) |

23.1 ± 13.0 21.3 (12.5, 34.4) |

23.6 ± 11.6 22.5 (15.0,34.4) |

22.2 ± 15.2 17.5 (12.5,34.4) |

NS NS |

|

BCVA: logMAR (mean ±SD) BCVA: logMAR (Median)(median; (median; 25th,75th) |

0.54 ± 0.35 0.50 (0.20,0.80) |

0.44 ± 0.33 0.34 (0.2,0.6) |

0.69 ± 0.33 0.8 (0.5,1.0) |

0.03 0.03 |

|

Contrast Sensitivity log unit (mean ±SD) Contrast Sensitivity (Median) log unit (median; 25th,75th) |

0.43 ± 0.48 0.18 (0,0.9) |

0.57 ± 0.50 0.7 (0,0.9) |

0.25 ± 0.38 00 (0, 0.6) |

0.074 0.056 |

| Central retinal thickness, mean ± SD (µm) (Median) (µm) ( 25th,75th) | 215.1 ± 64.4 203.0 (175.5,261.0 |

231.3 ± 59.9 224.0 (184.0,270.0) |

188.5 ± 64.6 185.5 (134.8,221.3) |

0.05 0.04 |

| Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness, (mean ± SD) (µm) (Median (µm) | 42.4 ± 11.3 41.0 (35.3,47.8) |

43.1 ± 12.7 41.0 (35.0, 48.3) |

41.2 ± 8.9 41.0 (35.3, 48.3) |

NS NS |

| Ganglion Cell Layer Thickness, mean ± SD (µm) (Median (µm) | 59.9 ± 16.8 57.0 (50,70.8) |

65.4 ± 16.2 60.0 (51.0, 77.0) |

50.2 ± 13.4 49.0 (40.5, 55.5) |

0.0001 0.002 |

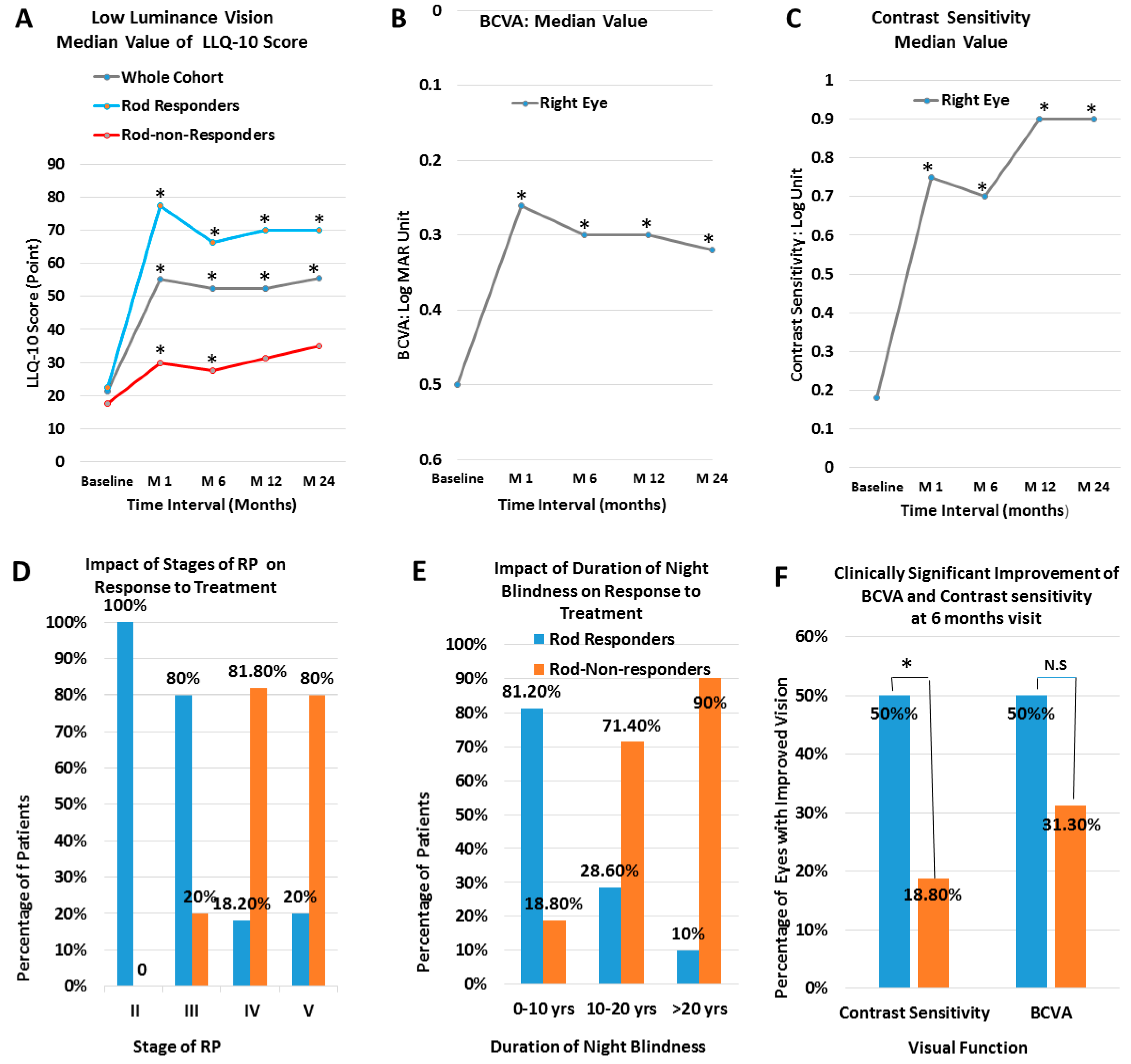

| Baseline | 1 month | 6 months | 12 months | 24 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LLQ-10 score (Whole Cohort): (Mean ± SD) P value Median Value (median; 25th, 75th) P value |

23.1 ± 13.0 21.3 (12.5,34.4) |

55.1 ± 28.6 (p=0.0001) 55.1 (37.5,85.0) (p= 0.0001) |

52.8 ± 27.2 (p=0.0001) 52.5 (37.5,85.0) (p=0.0001) |

52.9 ± 27.4 (p=0.0001) 52.5 (30.6,82.5) (p=0.0001) |

56.5 ± 28.0 (p=0.0001) 55.5 (32.5,85.0) (p=0.001) |

|

LLQ-10 score (Rod Responders): (Mean ± SD) P value Median Value (median; 25th, 75th) P value |

(23.6 ± 11.6) 22.5 (15.0,34.4) |

(73.5 ± 16.6) (p=0.0001) 77.5 (57.5,89.4) (p=0.0001) |

(70.0 ± 16.2) (p=0.0001) 66.3 (53.8,86.9) (p= 0.0001) |

(69.7 ± 20.5) (p=0.0001) 70.0 (52.5,86.9) (p=0.001) |

(68.9 ± 23.7) (p= 0.0001) 70.0 (54.0,90.0.0) (p=0.002) |

| BCVA (Whole Cohort, RE) (Log Mar) (Mean ± SD) P value Median Value (median; 25th, 75th) P value |

0.54 ±0.35 0.50 (0.02, 0.80) |

0.33 ±0.29 (p= 0.0001) 0.26 (0.03, 0.52) (p=0.0001) |

0.36 ± 0.30 (p= 0.0001) 0.3 (0.04, 0.6) (p=0.0001) |

0.40 ±0.34 (p=0.013) 0.3 (0.16, 0.6) (p=0.006) |

0.37 ± 0.29 (p=0.03) 0.32 (0.12, 0.57) (P=0.03) |

| Contrast Sensitivity (whole cohort RE) (Mean ± SD) P value Median Value (median; 25th, 75th) P value |

(0.43 ± 0.48) 0.18 (0.0, 0.9) |

(0.71 ± 0.51) (p=0.0001) 0.75 (0.21, 1.25) (p=0.0001) |

(0.65 ± 0.53) (p= 0.0001) 0.7 (0.03, 1.25) (p=0.0001) |

(0.71 ± 0.55) (p=0.002) 0.9 (0.0, 1.25) (p=0.003) |

(0.70 ± 0.53) (p=0.02) 0.9 (0.0, 1.22) (p=0.02) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).