1. Introduction

Handball is a high-intensity, contact sport that requires a high level of both aerobic and anaerobic performance [

1]. Several studies have confirmed that, in addition to tactical and technical skills, a high level of conditional abilities and anthropometric characteristics are also performance-influencing factors in handball [

2,

3]. The physical fitness of players can greatly influence the success of the team [

4]. Body height, body mass, and body composition play a decisive role in physical performance and are important factors in athlete selection [

5]. Data derived from motor tests (strength, speed, endurance) can be reliable predictors of performance; therefore, they hold particular significance in the evaluation of athletes [

6]. In various sports—including handball—it is of key importance to identify, through objective performance indicators, those motor abilities that distinguish elite athletes from those who are less outstanding.

When examining the performance of handball players, particular attention is given to test protocols assessing motor abilities, which include jumping, sprinting, agility and endurance [

7,

8,

9]. Several studies have demonstrated that the countermovement jump and squat jump tests possess high validity [

9,

10], and that Yo-Yo IR tests are suitable for determining intermittent endurance [

11,

12]. Tests assessing strength and explosiveness are essential among handball players [

13]. In light of this, the use of these tests is scientifically well-founded and important for examining the conditional demands of the sport.

In youth sports, the identification of talented players represents a complex, multifactorial process in which objective metrics constitute a critical component, complementing technical, tactical and psychological determinants of performance [

14,

15]. In handball specific physical attributes, namely maximal strength, speed and power are recognized as key indicators in the athlete selection process, given their direct impact on sport-specific actions such as jumping, running, sprinting and physical contact situations [

16,

17]. Nevertheless, the contribution of specific conditional abilities to performance may differ according to age, competitive level and sex with limited empirical evidence currently available for female youth athletes [

18,

19]. A comprehensive understanding of the physical performance characteristics that differentiate youth national team handball players from their non-selected peers may facilitate the development of more objective, evidence-based selection criteria and simultaneously support the long-term athletic development of talented players [

14].

One study investigated which tests reveal differences between handball players of various performance levels. The greatest differences were recorded in explosive strength (squat jump and countermovement jump), in favor of the Olympic team [

20]. When comparing youth national team and non-national team handball players, members of the national team outperformed their peers in several key tests (standing long jump, 30 m sprint, maximal oxygen uptake) [

21]. In young female handball players, significant performance differences were found between elite and non-elite groups and significant differences were also observed in anthropometric and body composition variables [

22]. Wagner et al. (2018) demonstrated that elite male handball players exhibit greater jump performance, maximal muscle strength, and better throwing velocity [

23]. Although numerous studies have examined the conditional and anthropometric characteristics of handball players in adult samples, considerably fewer data are available regarding youth athletes, particularly concerning differences between national team and non-national team players.

Our study aimed to determine whether differences in conditional abilities and body composition can be identified between youth national team and non-national team players. We sought to obtain a precise understanding of which conditional abilities and body composition variables most strongly characterize the attainment of youth national team level in the examined population. Our results may support the development of talent identification systems and provide practical benefits for sports professionals in designing more targeted training programs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Approach

Motor performance tests were conducted on 15 December 2025 at the Magvassy Mihály Sports Hall in Győr, Hungary. The test battery consisted of validated assessments supported by the scientific literature, and all procedures were executed according to established methodological guidelines. On a separate occasion, on 16 December 2025, the athletes body composition was evaluated. Before data collection, athletes, their guardians, and the discipline-specific coaches received verbal instructions and subsequently provided written informed consent for participation in the study.

2.2. Participants

The study included 36 female youth handball players from the Győri Audi ETO KC Handball Academy (mean age: 17.13 ± 1.75 years), comprising 18 national team athletes (height: 171.35 ± 4.73 cm; body mass: 67.68 ± 6.22 kg) and 18 position-matched non-selected players (height: 172.06 ± 8.30 cm; body mass: 66.52 ± 7.72 kg). National team status was defined as having received at least two invitations to national youth team training camps and/or participation in age-group world championships. To ensure comparability, each national team player was matched with a non-selected player by playing position.

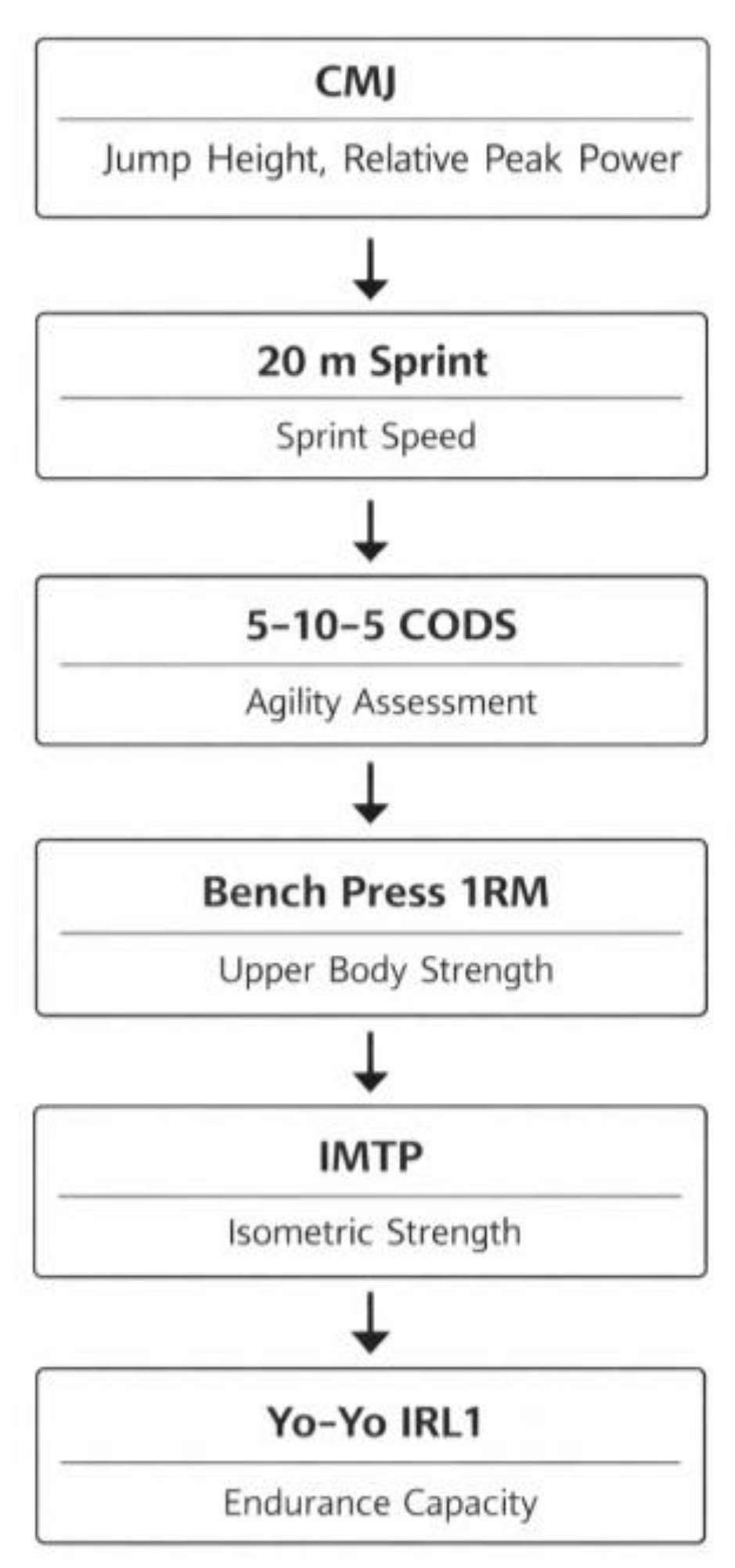

To minimize fatigue-related bias, athletes were instructed to refrain from strenuous training and competitive matches for 48 h before testing [

24]. The sequence of testing was designed to reduce neuromuscular fatigue and maximize the validity of performance outcomes. According to the protocol defined by the Hungarian Handball Federation, testing commenced with explosive power and speed assessments—given their high sensitivity to fatigue—followed by high-force strength measures, and concluded with endurance evaluation.

2.3. Measurement Protocol

Countermovement Jump (CMJ): The CMJ is a widely used method for assessing lower-limb force production, explosiveness, and stretch-shortening cycle efficiency [

25]. Force plates are considered the “gold standard” for measuring jump performance, as kinetic variables derived from ground reaction force provide accurate estimates of jumping height, force generation, and other parameters [

26]. The assessment was performed using a Vald ForceDecks Dual Force Plate system (FD Lite model, Newstead, Queensland, Australia; sampling frequency: 1000 Hz). Participants executed three maximal countermovement jumps with 30 s of rest between attempts. Athletes received verbal instructions prior to the test; verbal encouragement was not permitted during performance. For analysis, the highest recorded jump height (flight-time derived, cm) and relative peak power (W·kg

−1) were included.

20-m Sprint Test: The first pair of Witty photocells (Microgate, Bolzano, Italy) was positioned at the start line, 1,5 m apart. The second pair was placed 20 m from the start. Athletes began from a standing start 40 cm behind the start line, without a flying start. Each athlete initiated the test voluntarily following a standardized instruction: to complete the sprint in the shortest possible time. Three maximal trials were performed with 3 min of passive rest between attempts. The fastest time (s) were used for analysis.

Change of Direction Speed (5-10-5 CODS): This test assessed players’ ability to change direction twice at 180. Witty photocells were used for timing, with tripods opened to the first locking position and photocells placed above the midline. Cones were positioned 5 m to each side of the midpoint, and tape markings created parallel lines to ensure precise plant and cut execution, leaving a 40 cm gap at the center. Athletes assumed an athletic stance at the start line, positioned between both feet. After a self-initiated start, they sprinted left, planted the left foot at the cone while maintaining forward-facing orientation, returned through the start line, and repeated the movement to the right side. The test ended upon crossing the start line after the second change of direction. Players completed three trials to each side; the mean of the two fastest valid trials was recorded (s).

Bench Press Relative Maximal Strength: Upper body maximal strength was determined using the one-repetition maximum (1RM) bench press test. Following a standardized warm-up, athletes performed sets of 1-3 repetitions with progressively increasing loads until reaching the maximal weight that could be lifted once with proper technique. The obtained 1RM (kg) was normalized to body mass to determine relative strength (1RM/body mass, kg·kg−1).

Lower-Limb Maximal Isometric Strength (Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull; IMTP): Lower-limb maximal force production was assessed using the IMTP test, a reliable measure of maximal isometric strength [

27]. Athletes performed maximal isometric pulls with a bar positioned at mid-thigh height. The protocol followed international recommendations and Alex Natera’s standardized methodology. Before maximal attempts, participants completed three submaximal efforts (50–75–90% of estimated maximum) to minimize technical errors and reduce injury risk. Force production was measured using the Vald ForceDecks Dual Force Plate system (FD lite; sampling frequency: 1000 Hz). Peak force (N), defined as the highest point of the force-time curve, was recorded.

Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 1 (Yo-Yo IRL1): The Yo-Yo IRL1 is a widely applied test for assessing sport-specific aerobic capacity and recovery ability during repeated high-intensity efforts characteristic of intermittent sports [

28]. Participants performed 2*20 m shuttle runs at progressively increasing speeds, with 10 s of active recovery between bouts. Running pace was controlled using audio signals (bleep test application). The test ended when an athlete failed twice consecutively to maintain the required pace. Total distance covered (m) was recorded.

Body Composition Assessment: Body composition was measured using an Accuniq BC720 multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analyzer (BIA), whose reliability and validity have been confirmed [

29]. Measurements followed the manufacturer’s protocol. Athletes wore light clothing and stood barefoot on the device while segmental impedance was measured. To ensure reliability, assessments were conducted in a fasted state and participants refrained from fluid intake during the hour preceding measurement. The variables recorded for analysis were total body mass (kg), skeletal muscle mass (SMM, kg) and body fat percentage (BF%). Height was measured using a validated portable stadiometer (Seca 213, Hamburg, Germany). Athletes stood barefoot with heels, scapulae, and head aligned to the stadiometer backboard, in a neutral head position with fully extended knees. Measurements were taken during a natural breath hold following inhalation, in accordance with anthropometric recommendations, with millimeter accuracy. This research was approved by the Istvan Szechenyi University Scientific Council (ETT) Committee on Scientific Ethics SZE/ETT-95/2025 (XII.5), Hungary.

Figure 1.

The schematic illustration of the measurement protocol. CMJ = countermovement jump, m = meter, CODS = change of direction speed, 1RM = one-repetition maximum, IMTP = isometric mid-thigh pull, IRL 1 = intermittent recovery level 1.

Figure 1.

The schematic illustration of the measurement protocol. CMJ = countermovement jump, m = meter, CODS = change of direction speed, 1RM = one-repetition maximum, IMTP = isometric mid-thigh pull, IRL 1 = intermittent recovery level 1.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JASP 0.16.0.0. Normal distribution of data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Statistical significance was set at

p < 0,05. For variables showing normal distribution, independent-samples Student’s t-test was used to determine group differences. When the assumption of normality was violated, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was applied. Effect size (ES) was calculated using Cohen’s d, interpreted as very small (<0,20), small (0,20-0,59), moderate (0,60-1,19), large (1,20-1,99), and very large (>2,20) [

30].

3. Results

The mean and standard deviation values of the test results and basic anthropometric characteristic of the examined groups are presented in

Table 1.

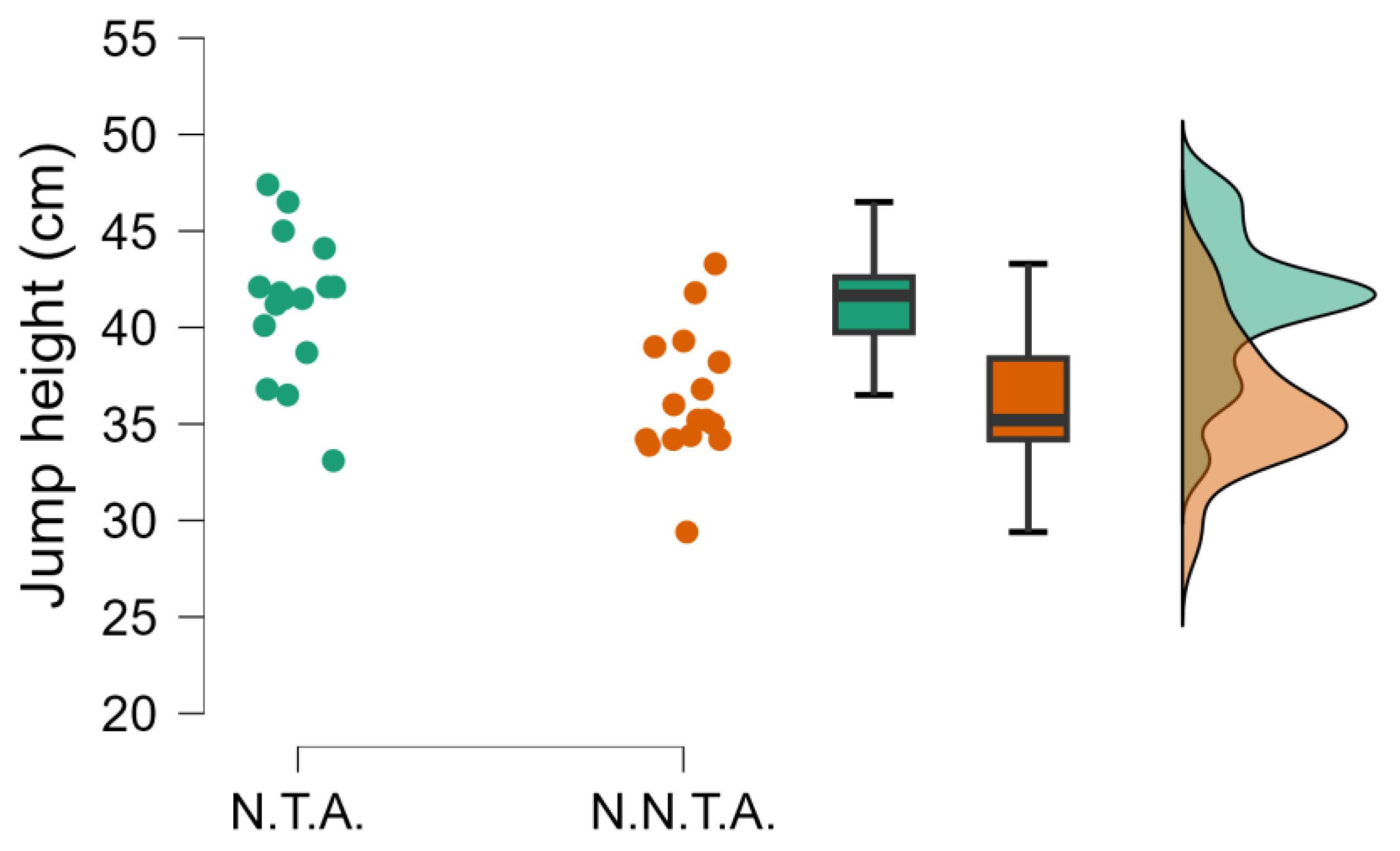

The independent-samples t-test comparing the performance of selected and non-selected handball players showed significant differences in several variables. National team athletes achieved significantly greater jump height (t = 4.163;

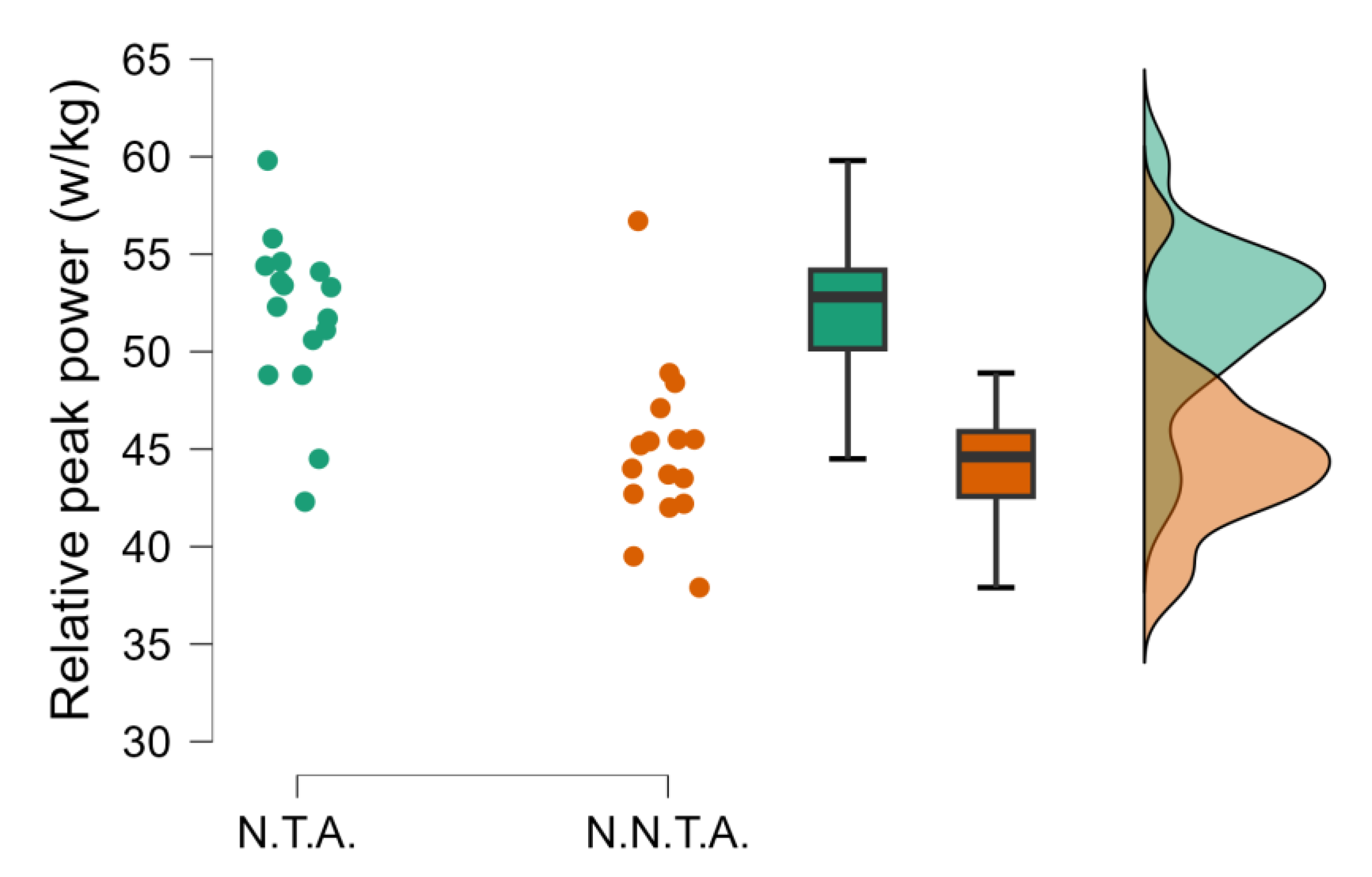

p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.408) (Figure 1), and their relative peak power was also substantially higher (t = 4.862;

p < 0.001; d = 1.644) (

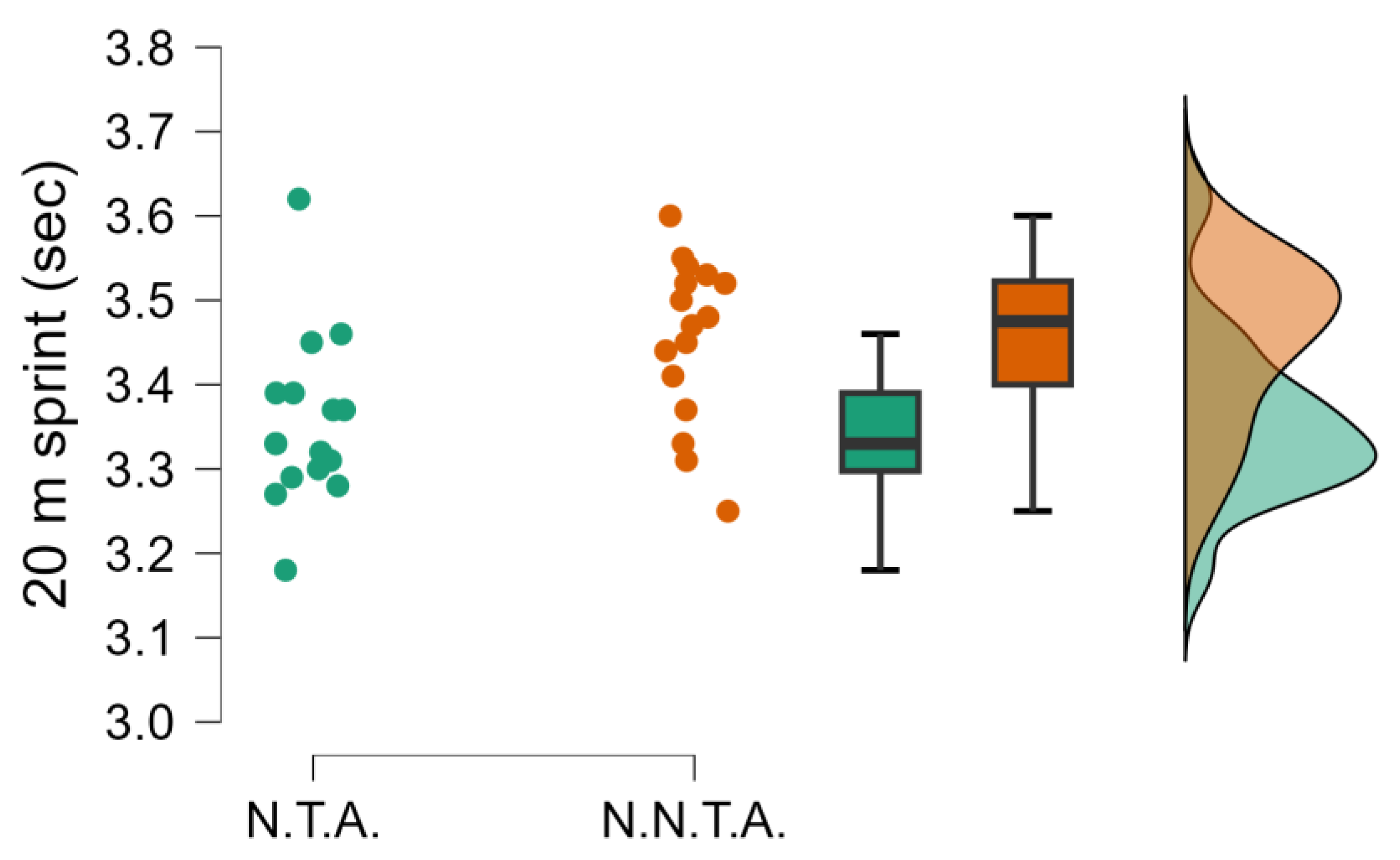

Figure 2). In the 20-m sprint time, the selected group proved to be faster (t = -3.067;

p = 0.004; d = -1.037) (

Figure 3).

Figure 1.

The significantly different jump height (t = 4.163; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.408). N.T.A. = National team athletes, N.N.T.A. = Non-national team athletes.

Figure 1.

The significantly different jump height (t = 4.163; p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.408). N.T.A. = National team athletes, N.N.T.A. = Non-national team athletes.

Figure 2.

The significantly different relative peak power (t = 4.862; p < 0.001; d = 1.644). N.T.A. = National team athletes, N.N.T.A. = Non-national team athletes.

Figure 2.

The significantly different relative peak power (t = 4.862; p < 0.001; d = 1.644). N.T.A. = National team athletes, N.N.T.A. = Non-national team athletes.

Figure 3.

The significantly different 20-m sprint (t = -3.067; p = 0.004; d = -1.037). N.T.A. = National team athletes, N.N.T.A. = Non-national team athletes.

Figure 3.

The significantly different 20-m sprint (t = -3.067; p = 0.004; d = -1.037). N.T.A. = National team athletes, N.N.T.A. = Non-national team athletes.

No significant differences were found between the groups for the other performance variables. In the 5-10-5 change of direction test (t = -1.028; p = 0.312), relative bench press (t = 1.787; p = 0.083), the Yo-Yo IRL1 endurance test (t = 1.563; p = 0.013), and IMTP (t = 0.007; p = 0.994), no statistically detectable differences were observed. The anthropometric variables—body height (t = -0.305; p = 0.762), body mass (t = 0.493; p = 0.625), skeletal muscle mass (t = 0.681; p = 0.501), and body fat percentage (t = -1.644; p = 0.110)—also didn’t differ significantly between the two groups.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to identify differences in body composition and conditional performance between youth national-team and non-national-team female handball players. Our results indicate that the two groups differed significantly in several motor abilities that are considered crucial for handball performance. Specifically, we found differences in explosive strength assessed by the countermovement jump (CMJ), as well as in linear speed (20 m sprint), with national team players outperforming their non-selected peers. Surprisingly, for most of the other motor tests, such as change of direction ability (5-10-5 CODS), isometric mid-thigh pull (IMTP), and relative maximal pushing strength (1RM bench press/body weight), no significant group differences were observed. Similarly, no meaningful differences emerged between groups in anthropometric characteristics (body height, body mass) or in body composition variables (body fat percentage, skeletal muscle mass).

One of the most prominent findings of our research was the significantly superior performance of national-team players in the CMJ test. The greater jump height and higher relative peak power indicate that the selected players possess enhanced explosive strength and more efficient stretch-shortening cycle function, both of which are key determinants of sport specific performance in handball [

31,

32,

33]. These findings align with previous studies reporting higher jump performance among female handball players of varying competitive levels and training backgrounds [

20,

34]. Other research has similarly emphasized that high levels of rapid force production are essential for reaching elite status [

22,

34]. Superior vertical jump performance provides athletes with an advantage during offensive actions, where the ability to elevate rapidly and to the greatest possible height enhances shooting success [

2]. The difference observed between national-team and non-national-team players in our study suggests that jump performance may play a key role in talent identification and in establishing performance profiles in youth handball.

The 20 m sprint test also revealed significant differences between groups. National team players were faster, suggesting that linear acceleration capacity is a relevant performance determinant in youth female handball. Numerous studies support our findings, reporting superior sprint performance in top-level compared to lower-level athletes [

33,

35]. However, the literature is not entirely consistent, as several studies have shown that linear sprint time does not always reliably differentiate between performance levels [

20,

36,

37]. Overall, although our data and several previous works identify 20 m sprint performance as a potential limiting factor may include age group, sample size, sprint distance, and differences in test protocols. Therefore, assessing linear speed alongside other measures of explosive strength is recommended.

Furthermore, our results showed no differences between groups in maximal strength, endurance performance, or change of direction ability. Concerning endurance performance, several reviews and empirical studies emphasize that intermittent aerobic tests and traditional VO2max assessments do not necessarily distinguish between elite and non-elite players in team sports. This may be linked to the sport-specific nature of aerobic demands, variability in testing protocols, and the limited association between laboratory VO2max values and match-specific physical outputs [

38,

39]. Change of direction performance is highly dependent on protocol characteristics (number and length of direction changes, angles etc.), making comparisons across studies challenging. As highlighted by prior research, methodological differences alone may lead to inconsistent findings regarding performance differences across competitive levels [

40]. The absence of significant differences in maximal strength measures (IMTP and relative bench press) was unexpected. However, several factors may explain this. Previous literature suggests that he relationship between one-repetition maximum measures and handball-specific performance is often mediated by fat-free mass [

41]. Given the similarity between our groups in anthropometric and body composition profiles, differences in absolute force production may have been attenuated. Additionally, explosive strength expressed in CMJ performance does not necessarily correspond to maximal isometric strength, as the IMTP measures peak isometric force, whereas the CMJ reflects SSC efficiency and dynamic explosive power [

42,

43].

Regarding the fundamental anthropometric and body composition variables (body height and body mass), no significant differences were observed between the two groups. This suggests that, within this age category, these variables alone may not serve as distinguishing factors. In contrast, several classical and contemporary studies have reported opposite findings, particularly in younger or still developing age groups [

21,

44,

45,

46]. Earlier research demonstrated that, during talent identification in youth handball, greater body mass, taller stature, and more favorable body composition often accompany a higher competitive level [

21]. Similarly, a study examining male handball players confirmed that, over the long term, a clear anthropometric trend emerges among world-class athletes, with pivots and defensive players being generally taller and possessing a larger body frame [

45]. Overall, our findings suggest that although a substantial body of literature indicates that anthropometric characteristics may distinguish elite from non-elite athletes, in this sample of youth athletes these variables were not decisive. This may imply that, at his developmental stage, selection processes are primarily performance based rather than driven by anthropometric criteria.

Our findings hold substantial practical relevance for youth athlete development and performance diagnostics. The study identifies which conditional variables most strongly contribute to reaching national-team level and which objective markers are less suitable for distinguishing between competitive levels. These insights can inform and optimize talent identification and long-term athlete development models. Motor tests that showed significant differences in our study (e.g., explosive strength and speed) may serve as key indicators of advancement programs. Conversely, parameters that showed no group differences highlight the importance of avoiding a narrow anthropometric selection approach and instead adopting a broader, multifactorial performance profiling strategy. Our results thus provide practical guidance for coaches and sport scientists seeking to support the athletic development of youth handball players more effectively.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the relatively small sample size may limit the ability to detect subtle but practically relevant differences. Second, all tests were performed on a single occasion, which does not account for day-to-day fluctuations in readiness or fatigue. Additionally, training load and athletes training histories, were not controlled, which may have influenced performance outcomes. As such, caution is warranted when generalizing the finding, and further research with larger samples and longitudinal designs is required to confirm our conclusions.

Future studies should incorporate additional tests assessing psychological and cognitive functions, as these may play important roles in match performance. Furthermore, expanding the research to male youth athletes and exploring performance differences across distinct age categories may provide additional valuable insights.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B.R. and R.B.; methodology, I.B.R.; software, Z.A.; validation, A.Z., F.I. and A.F.; formal analysis, B.K.; investigation, L.S.; resources, I.B.R.; data curation, I.F.; writing—original draft preparation, I.B.R.; writing—review and editing, F.I.; visualization, Á.P.; supervision, Cs.Ö.; project administration, O.V.; funding acquisition, I.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data collection was conducted in full compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants and their legal guardians were fully informed about the study and gave their written consent to participate. The study was conducted on a voluntary basis in cooperation with the sports clubs and national rowing associations involved. The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of Széchenyi Istvan University (protocol code SZE/ETT-95/2025 (XII.5.), approval date 5 December 2025) and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank all participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CMJ |

Countermovement Jump |

| IMTP |

Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull |

| N.T.A. |

National Team Athletes |

| N.N.T.A. |

Non-national Team Athletes |

| CODS |

Change of direction speed |

| IRL1 |

Intermittent Recovery Level 1 |

| 1RM |

One-repetition maximum |

| SSC |

Stretch Shortening Cycle |

References

- Hermassi, S.; Wollny, R.; Schwesig, R.; Shephard, R. J.; Chelly, M. S. Effects of In-Season Circuit Training on Physical Abilities in Male Handball Players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2019, 33(4), 944–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcher, C.; Buchheit, M. On-court demands of elite handball, with special reference to playing positions; Sports Medicine: Auckland, N.Z.), 2014; Volume 44, 6, pp. 797–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieseler, G.; Hermassi, S.; Hoffmeyer, B.; Schulze, S.; Irlenbusch, L.; Bartels, T.; Delank, K.-S.; Laudner, K. G.; Schwesig, R. Differences in anthropometric characteristics in relation to throwing velocity and competitive level in professional male team handball: A tool for talent profiling. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2017, 57(7–8), 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaratezabala, E.; Nakamura, F.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Castillo, D.; Rodríguez-Negro, J.; Yanci, J. Differences in Physical Performance According to the Competitive Level in Amateur Handball Players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2020, 34(7), 2048–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alföldi, Z.; Borysławski, K.; Ihász, F.; Soós, I.; Podstawski, R. Differences in the Anthropometric and Physiological Profiles of Hungarian Male Rowers of Various Age Categories, Rankings and Career Lengths: Selection Problems. Frontiers in Physiology 2021, 12–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suszter, L.; Barthalos, I.; Balázs, F.; Ihász, F. Anthropometric and motor characteristics of adolescence male and female rowers, their relationship with performance and their importance in selection. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Spencer, M.; Ahmaidi, S. Reliability, usefulness, and validity of a repeated sprint and jump ability test. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2010, 5(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermassi, S.; Aouadi, R.; Khalifa, R.; van den Tillaar, R.; Shephard, R. J.; Chelly, M. S. Relationships between the yo-yo intermittent recovery test and anaerobic performance tests in adolescent handball players. Journal of Human Kinetics 2015, 45, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fristrup, B.; Krustrup, P.; Kristensen, K. H.; Rasmussen, S.; Aagaard, P. Test-retest reliability of lower limb muscle strength, jump and sprint performance tests in elite female team handball players. European Journal of Applied Physiology 2024, 124(9), 2577–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, G.; Dizdar, D.; Jukic, I.; Cardinale, M. Reliability and factorial validity of squat and countermovement jump tests. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2004, 18(3), 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchheit, M.; Spencer, M.; Ahmaidi, S. Reliability, usefulness, and validity of a repeated sprint and jump ability test. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2010, 5(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchheit, M.; Rabbani, A. The 30-15 Intermittent Fitness Test versus the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test Level 1: Relationship and sensitivity to training. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2014, 9(3), 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermassi, S.; Laudner, K.; Schwesig, R. The Effects of Circuit Strength Training on the Development of Physical Fitness and Performance-Related Variables in Handball Players. Journal of Human Kinetics 2020, 71, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Till, K.; Baker, J. Challenges and [Possible] Solutions to Optimizing Talent Identification and Development in Sport. Frontiers in Psychology 2020, 11, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaeyens, R.; Lenoir, M.; Williams, A. M.; Philippaerts, R. M. Talent identification and development programmes in sport: Current models and future directions. In Sports Medicine; Auckland, N.Z.), 2008; Volume 38, 9, pp. 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalsik, L. B.; Aagaard, P. Physical demands in elite team handball: Comparisons between male and female players. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2015, 55(9), 878–891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gorostiaga, E. M.; Granados, C.; Ibáñez, J.; Izquierdo, M. Differences in physical fitness and throwing velocity among elite and amateur male handball players. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2005, 26(3), 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, R.; Oliver, J. The Youth Physical Development Model. Strength and Conditioning Journal 2012, 34, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meylan, C. M. P.; Cronin, J. B.; Oliver, J. L.; Hopkins, W. G.; Contreras, B. The effect of maturation on adaptations to strength training and detraining in 11-15-year-olds. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2014, 24(3), e156-164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Abad, C.; Kobal, R.; Kitamura, K.; Orsi, R.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Loturco, I. Differences in Speed and Power Capacities Between Female National College Team and National Olympic Team Handball Athletes. Journal of Human Kinetics 2018, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapartidis, I.; Vareltzis, I.; Gouvali, M.; Kororos, P. Physical Fitness and Anthropometric Characteristics in Different Levels of Young Team Handball Players. The Open Sports Sciences Journal 2009, 2, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, S. L.; McWhannell, N.; Michalsik, L. B.; Twist, C. Anthropometric and physical performance characteristics of top-elite, elite and non-elite youth female team handball players. Journal of Sports Sciences 2015, 33(17), 1780–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.; Fuchs, P. X.; von Duvillard, S. P. Specific physiological and biomechanical performance in elite, sub-elite and in non-elite male team handball players. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2018, 58(1–2), 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Fernandez, J.; Saez de Villarreal, E.; Sanz-Rivas, D.; Moya, M. The Effects of 8-Week Plyometric Training on Physical Performance in Young Tennis Players. Pediatric Exercise Science 2016, 28(1), 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komi, P. V. Stretch-shortening cycle: A powerful model to study normal and fatigued muscle. Journal of Biomechanics 2000, 33(10), 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckthorpe, M.; Morris, J.; Folland, J. P. Validity of vertical jump measurement devices. Journal of Sports Sciences 2012, 30(1), 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grgic, J.; Scapec, B.; Mikulic, P.; Pedisic, Z. Test-retest reliability of isometric mid-thigh pull maximum strength assessment: A systematic review. Biology of Sport 2022, 39(2), 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangsbo, J.; Iaia, F. M.; Krustrup, P. The Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test: A useful tool for evaluation of physical performance in intermittent sports. In Sports Medicine; Auckland, N.Z.), 2008; Volume 38, 1, pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-W.; Kim, T.-H.; Choi, H.-M. The reproducibility and validity verification for body composition measuring devices using bioelectrical impedance analysis in Korean adults. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation 2018, 14(4), 621–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungovan, S. F.; Peralta, P. J.; Gass, G. C.; Scanlan, A. T. The test-retest reliability and criterion validity of a high-intensity, netball-specific circuit test: The Net-Test. J Sci Med Sport 2018, 21(12), 1268–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, F.; Zhong, Y.; Zhu, L.; Feng, S. Meta-analysis of the effects of plyometric training on athletic performance in handball athletes. Scientific Reports 2025, 15(1), 29298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, M.; Izquierdo, M.; Marinho, D.; Barbosa, T.; Ferraz, R.; González-Badillo, J. Association Between Force-Time Curve Characteristics and Vertical Jump Performance in Trained Athletes. Journal of strength and conditioning research/National Strength & Conditioning Association 2015, 29, 2045–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohoric, U.; Abazovic, E.; Paravlic, A. H. Morphological and Physical Performance-Related Characteristics of Elite Male Handball Players: The Influence of Age and Playing Position. Applied Sciences 2022, 12(23), 11894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados, C.; Izquierdo, M.; Ibáñez, J.; Ruesta, M.; Gorostiaga, E. M. Are there any differences in physical fitness and throwing velocity between national and international elite female handball players? Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2013, 27(3), 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Malia, J. M.; Rodiles-Guerrero, L.; Pareja-Blanco, F.; Ortega-Becerra, M. Determinant factors for specific throwing and physical performance in beach handball. Science & Sports 2022, 37(2), 141.e1–141.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, J.; Chen, C.; Chmura, P.; Krustrup, P. Relationship between team ranking and physical fitness in elite male handball players in different playing positions. Scientific Reports 2024, 14(1), 3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, T. A.; Tønnessen, E.; Seiler, S. Physical and physiological characteristics of male handball players: Influence of playing position and competitive level. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2016, 56(1–2), 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Michalsik, L. B.; Fuchs, P.; Wagner, H. The Team Handball Game-Based Performance Test Is Better than the Yo-Yo Intermittent Recovery Test to Measure Match-Related Activities in Female Adult Top-Elite Field Team Handball Players. Applied Sciences 2021, 11(14), 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaevangelou, E.; Papadopoulou, Z.; Michailidis, Y.; Mandroukas, A.; Nikolaidis, P. T.; Margaritelis, N. V.; Metaxas, T. Changes in Cardiorespiratory Fitness during a Season in Elite Female Soccer, Basketball, and Handball Players. Applied Sciences 2023, 13(17), 9593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard Falch, H.; Guldteig Rædergård, H.; van den Tillaar, R. Effect of Different Physical Training Forms on Change of Direction Ability: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Medicine—Open 2019, 5(1), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados, C.; Izquierdo, M.; Ibañez, J.; Bonnabau, H.; Gorostiaga, E. M. Differences in physical fitness and throwing velocity among elite and amateur female handball players. International Journal of Sports Medicine 2007, 28(10), 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavridis, I.; Zisi, M.; Arsoniadis, G. G.; Terzis, G.; Tsolakis, C.; Paradisis, G. P. Relationship Between Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull Force, Sprint Acceleration Mechanics and Performance in National-Level Track and Field Athletes. Applied Sciences 2025, 15(3), 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojskić, H.; Schiller, J.; Pagels, P.; Ragnarsson, T.; Melin, A. K. Are counter movement jump and isometric mid-thigh pull tests reliable, valid, and sensitive measurement instruments when performed after maximal cardiopulmonary exercise testing? A sex-based analysis in elite athletes. Frontiers in Physiology 2025, 16, 1663590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lijewski, M.; Burdukiewicz, A.; Stachoń, A.; Pietraszewska, J. Differences in anthropometric variables and muscle strength in relation to competitive level in male handball players. PloS One 2021, 16(12), e0261141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuciuc, F. V.; Petrariu, I.; Pricop, G.; Rohozneanu, D. M.; Popovici, I. M. Toward an Anthropometric Pattern in Elite Male Handball. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massuça, L. M.; Fragoso, I.; Teles, J. Attributes of top elite team-handball players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2014, 28(1), 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

The mean and standard deviation values of the test results and basic anthropometric characteristic of the examined groups. N.T.A.=National team athletes, N.N.T.A.=Non-national team athletes.

Table 1.

The mean and standard deviation values of the test results and basic anthropometric characteristic of the examined groups. N.T.A.=National team athletes, N.N.T.A.=Non-national team athletes.

| |

N.T.A. |

N.N.T.A. |

| |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

| Body height (cm) |

171.35 |

4.73 |

172.01 |

8.30 |

| Body mass (kg) |

67.68 |

6.22 |

66.52 |

7.72 |

| Skeletal muscle mass (kg) |

31.19 |

3.31 |

30.31 |

4.06 |

| Body fat percentage (%) |

17.33 |

3.99 |

19.92 |

4.97 |

| Jump height (cm) |

41.17 |

3.56 |

36.32 |

3.01 |

| Relative peak power (w/kg) |

51.54 |

4.07 |

44.41 |

4.61 |

| 20 m sprint (sec) |

3.35 |

0.10 |

3.46 |

0.09 |

| 5-10-5 CODS (sec) |

4.93 |

0.14 |

4.98 |

0.11 |

| IMTP (N) |

2462.94 |

293.74 |

2476.54 |

476.03 |

| Bench press (kg/ttkg) |

0.78 |

0.12 |

0.71 |

0.11 |

| YoYo IRL1 (m) |

2100.00 |

337.26 |

1897.65 |

425.79 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |