Submitted:

15 January 2025

Posted:

16 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

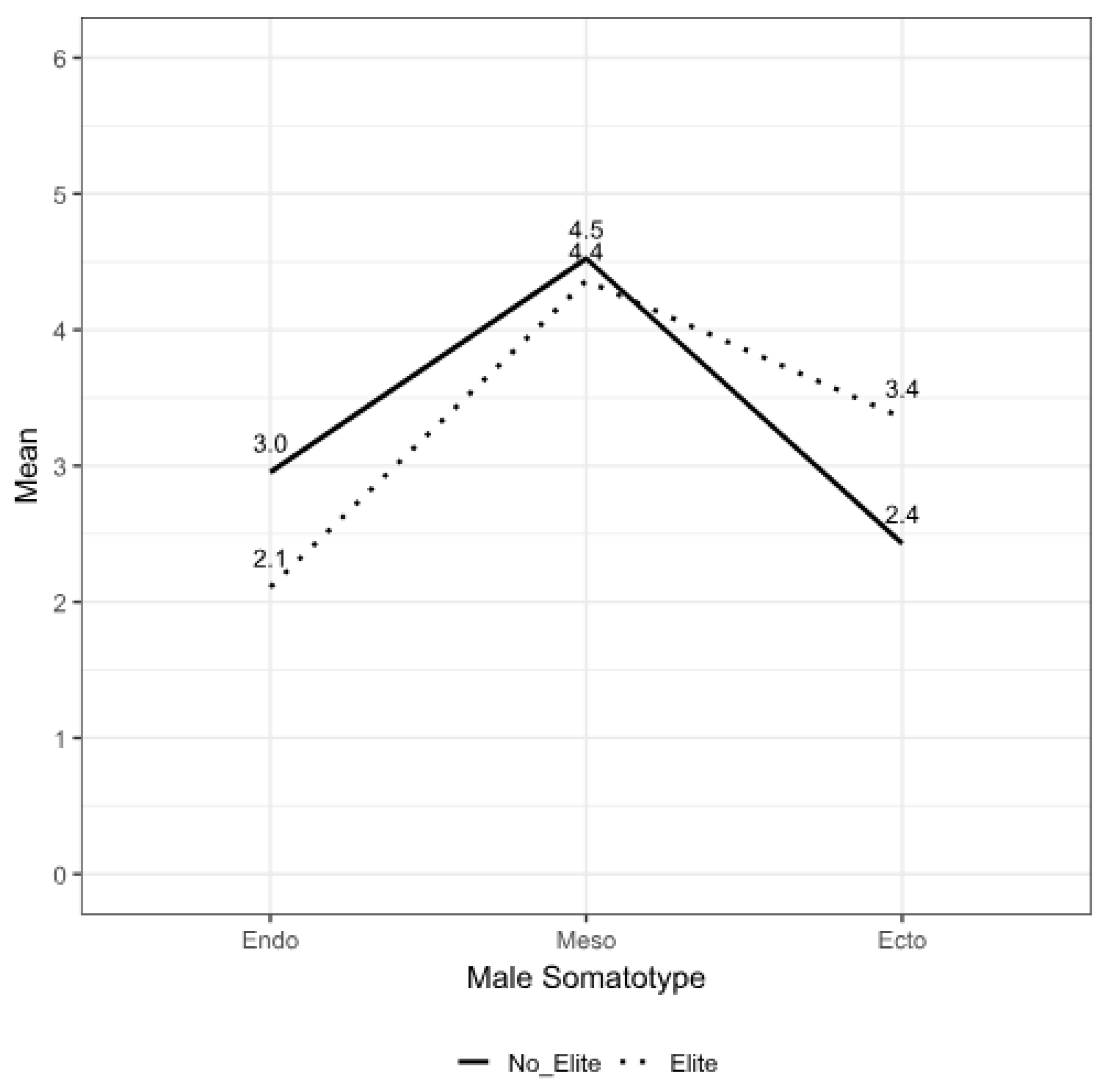

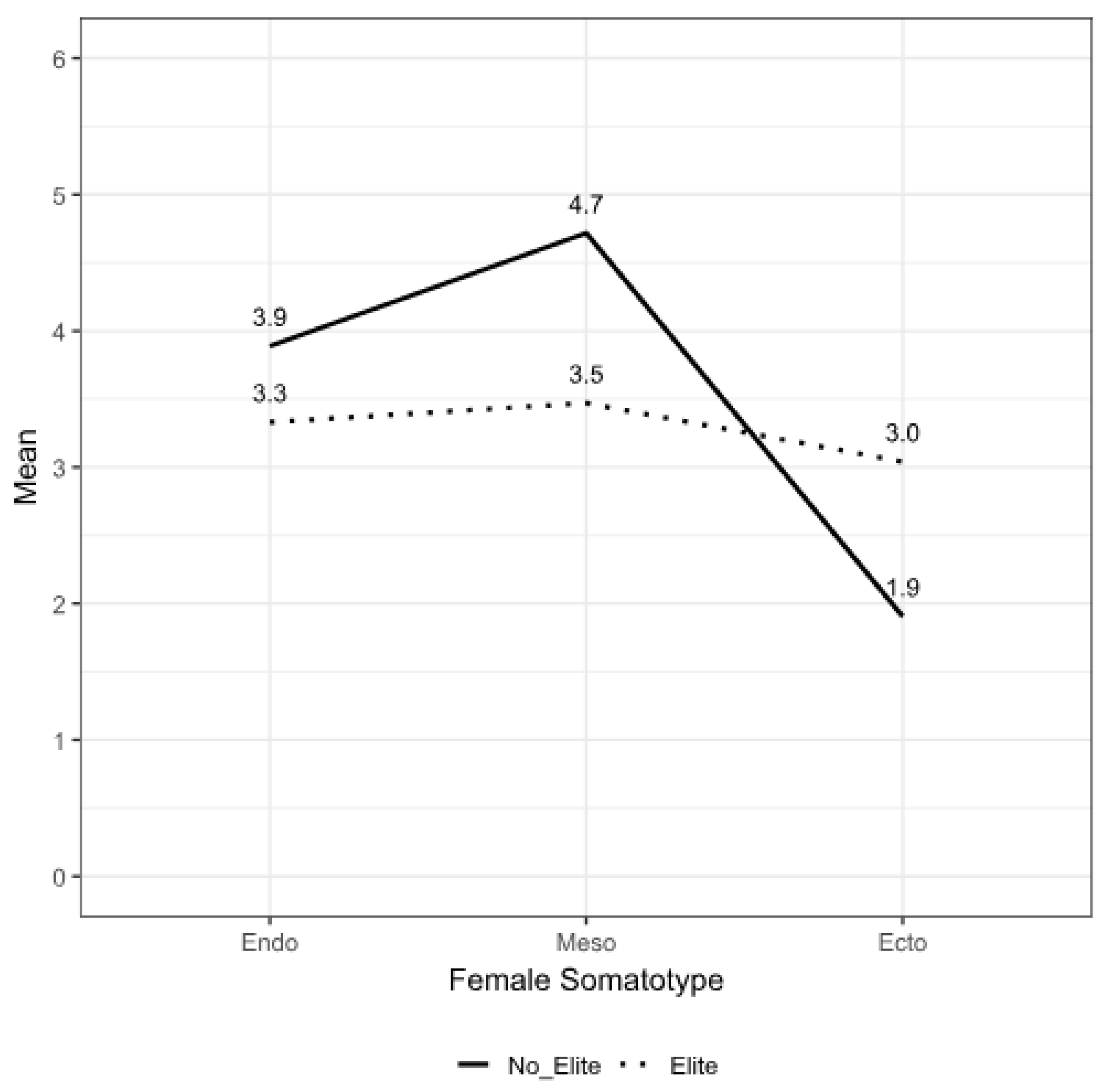

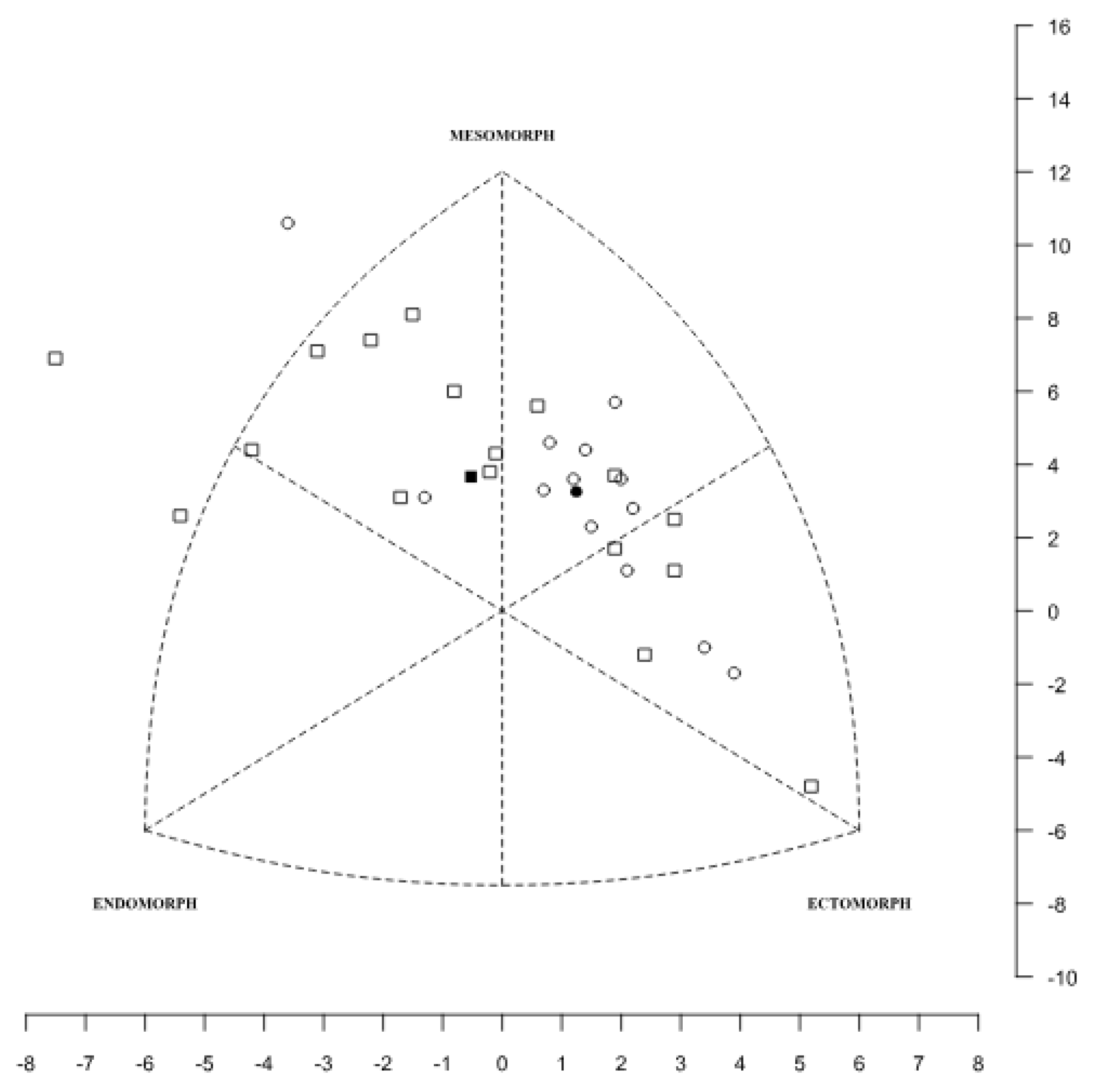

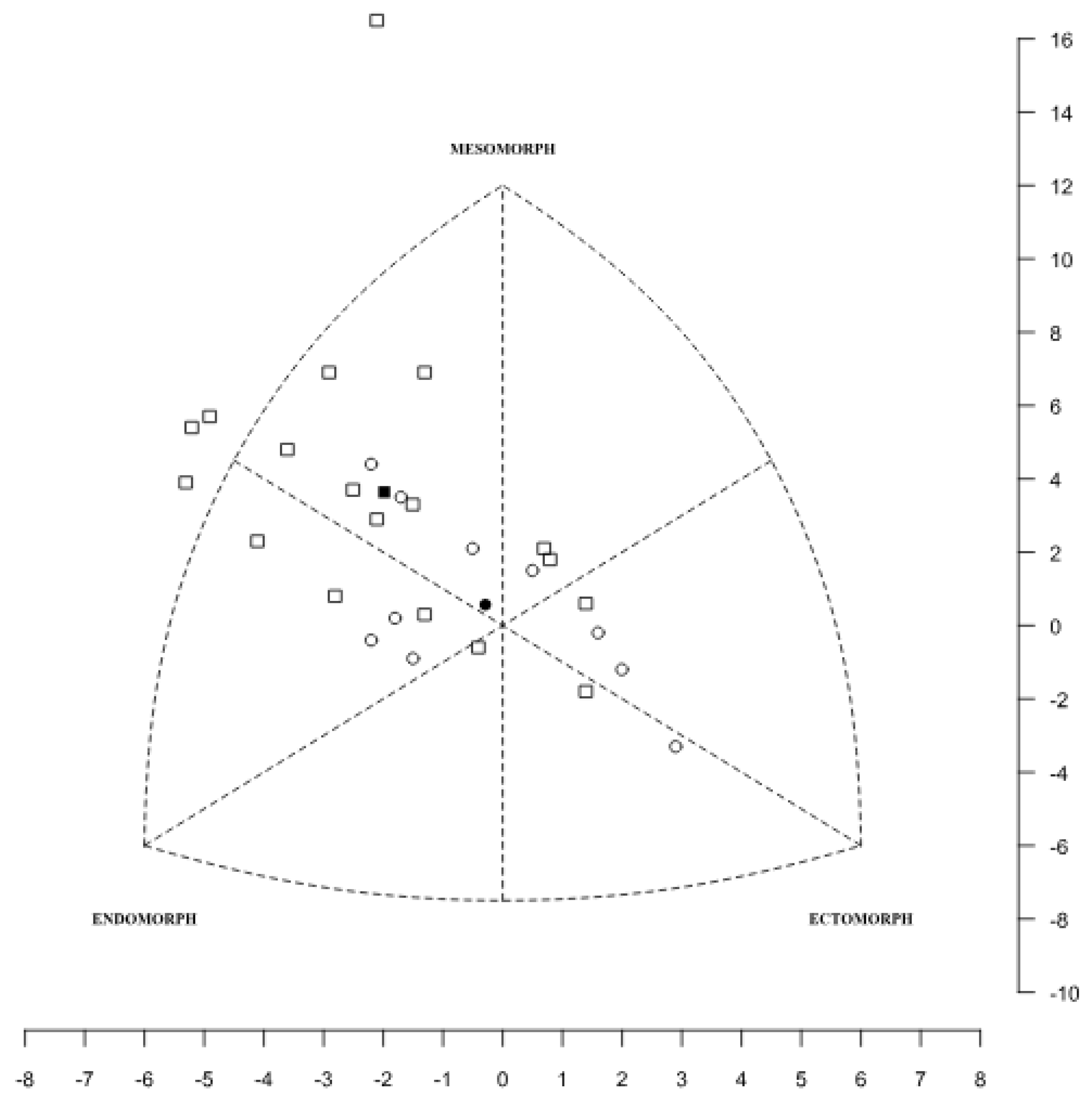

Objectives: This study aimed to identify physique characteristics (anthropometric, somatotype, body composition) of Orienteers and to compare them across with Nutrition Knowledge and Physical Activity Level. Methods: Data was collected from 58 competitive Orienteering athletes, 10 elite female (age = 25.5 ± 6.4 years, body mass = 59.5 ± 7.7 kg, height = 168.1 ± 6.5 cm, BMI = 21.0 ± 1.9 kg/m2) and 13 elite male (age = 24.3 ± 5.0 years, body mass = 65.0 ± 5.5 kg, height = 175.1 ± 6.0 cm, BMI = 21.3 ± 2.2 kg/m2) and 18 non-elite female (age = 41.7 ± 10.3 years, body mass = 60.6 ± 8.5 kg, height = 161.3 ± 11.7 cm, BMI = 23.4 ± 3.7 kg/m2) and 17 non-elite male (age = 37.2 ± 14.6 years, body mass = 71.5 ± 14.2 kg, height = 174.0 ± 8.8 cm, BMI = 23.6 ± 4.1 kg/m2). Nutrition knowledge was evaluated using the updated Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire (A-NSKQ). Physical activity was assessed using the short version of the self-reported International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form (IPAQ-SF). Results: The percentage of body fat (p = .050) in elite male was significantly lower than in non-elite male. Mesomorphy (p = .030) in elite female was significantly lower than in non-elite female, but the ectomorphy (p = .019) was significantly higher. Elite male are ectomorphic mesomorph while non-elite male are balanced mesomorph and elite female are central and non-elite female are endomorphic mesomorph. Significant differences (p = .025) were also observed in the Sports Nutrition Knowledge among elite male and non-elite male, with the former group achieving a higher percentage of correct responses. In the case of Total Nutritional Knowledge, elite Orienteering athletes of both sexes scored significantly higher (elite female: p = .042; elite male: p = .029) than their non-elite counterparts. A significant negative correlation is also observed between body fat and MET-min/week (r = −.39, p = .038), bone mass and MET-min/week (r = −.40, p = .033), endomorphy and Sports Nutrition Knowledge (r = −.38, p = .045) in female Orienteering athletes. Among male Orienteering athletes the most significant findings include a negative correlation between age and MET-min/week (r = −.49, p = .010), kcal/week (r = −.46, p = .016) and Sports Nutrition Knowledge (r = −.40, p = .029). Conclusions: Key findings indicate that elite Orienteers have lower body fat percentages and higher nutrition knowledge scores compared to non-elite Orienteers. These results on the physical characteristics of Orienteering athletes and score of Physical Activity and classification of Nutrition Knowledge can be useful to coaches and sports scientists to improve Orienteer’s performance.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Participants

2.3. Variables and Measures

2.4. Nutritional Knowledge Assessment

2.5. Physical Activity Assessment

2.6. Anthropometric Measurements

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACSM | American College of Sports Medicine |

| A-NSKQ | Abridged Nutrition for Sport Knowledge Questionnaire |

| BF | Body Fat |

| BC | Body Composition |

| BD | Body Density |

| BM | Bone Mass |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| E | Elite |

| EFOA | Elite Female Orienteering Athletes |

| EMOA | Elite Male Orienteering Athletes |

| F | Female |

| FEDO | Spanish Orienteering Federation |

| FPO | Portuguese Orienteering Federation |

| FOA | Female Orienteering Athletes |

| GNK | General Nutrition Knowledge |

| IOF | International Orienteering Federation |

| IPAQ-SF | International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form |

| ISAK | International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry |

| M | Male |

| MET | Metabolic Equivalent |

| MM | Muscle Mass |

| MOA | Male Orienteering Athletes |

| NE | Non-Elite |

| NEFOA | Non-Elite Female Orienteering Athletes |

| NEMOA | Non-Elite Male Orienteering Athletes |

| NK | Nutrition Knowledge |

| OA | Orienteering Athletes |

| OP | Orienteering Practice |

| OTF | Orienteering Training Frequency |

| OTQ | Orienteering Training Quantity |

| PAL | Physical Activity Level |

| REDs | Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport |

| SAM | Somatotype Attitudinal Mean |

| SAD | Somatotype Attitudinal Distance |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SDD | Somatotype Dispersion Distance |

| SDM | Somatotype Dispersion Mean |

| SNK | Sports Nutrition Knowledge |

| ST | Skinfold Thickness |

| TNK | Total Nutritional Knowledge |

References

- International Orienteering Federation (IOF). International Orienteering Federation Home Page. Available online: https://orienteering.sport/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Batista, M.M.; Paludo, A.C.; Gula, J.N.; Pauli, P.H.; Tartaruga, M.P. Physiological and cognitive demands of orienteering: a systematic review. Sport Sci. Health 2020, 16, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparza-Ros, F.; Vaquero-Cristóbal, R.; Marfell-Jones, M. Protocolo Internacional para la Valoración Antropométrica. Perfil Completo. Sociedad Internacional para el Avance de la Cineantropometría: Murcia, España, 2019.

- Trakman, G.L.; Forsyth, A.; Hoye, R.; Belski, R. The nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (NSKQ): development and validation using classical test theory and Rasch analysis. J. Int, Soc, Sports Nutr. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trakman, G.L.; Forsyth, A.; Hoye, R.; Belski, R. Development and validation of a brief general and sports nutrition knowledge questionnaire and assessment of athletes’ nutrition knowledge. J. Int, Soc, Sports Nutr. 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trakman, G.L.; Brown, F.; Forsyth, A.; Belski, R. Modifications to the nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (NSQK) and abridged nutrition for sport knowledge questionnaire (ANSKQ). J. Int, Soc, Sports Nutr. 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celestino, T.F.S.; Leitão, J.C.G.C.; Pereira, A.M.A. Determinantes para a excelência na Orientação: as representações de treinadores e atletas de elite (Determinants for excellence in Orienteering: the representation of elite coaches and athletes) (Determinantes para la excelencia en la orientación: las representaciones de entrenadores y atletas de elite). Retos 2019, 35, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federação Portuguesa de Orientação (FPO). Federação Portuguesa de Orientação Home Page. Available online: https://www.fpo.pt/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Federación Española de Orientación (FEDO). Federación Española de Orientación Home Page. Available online: https://www.fedo.org/web/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Levine, D.M.; Stephan, D.F.; Szabat, K.A. Estatística: Teoria e Aplicações Usando o Microsoft Excel® em Português, 7th ed.; LTC: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Federación del Deporte de Orientación de la Comunidad Valenciana (FEDOCV). Federación del Deporte de Orientación de la Comunidad Valenciana Home Page. Available online: https://www.fedocv.org/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). IPAQ - International Physical Activity Questionnaire Home Page. Available online: https://sites.google.com/view/ipaq/home (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Sember, V.; Meh, K.; Sorić, M.; Starc, G.; Rocha, P.; Jurak, G. Validity and reliability of International Physical Activity Questionnaires for adults across EU countries: systematic review and meta analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, B.E.; Haskell, W.L.; Whitt, M.C.; Irwin, M.L.; Swartz, A.M.; Strath, S.J.; O'Brien, W.L.; Bassett, D.R., Jr.; Schmitz, K.H.; Emplaincourt, P.O.; et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, S498–S516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.S.; Vieira, M.F.S. International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry (ISAK) Global: international accreditation scheme of the competent anthropometrist. Rev. Bras. Cineantropom. Desempenho Hum. 2020, 22, e70517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, V.S.; Souza, I.; Sehl, P.L. Good hygienic-sanitary practices in anthropometric routine in the (post-) COVID-19 pandemic. Rev. Bras. Cineantropom. Desempenho Hum. 2021, 23, e77625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G.; Feito, Y.; Fountaine, C.; Roy, B.A. Diretrizes do ACSM para os Testes de Esforço e sua Prescrição, 11th ed.; Guanabara Koogan: Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2023; pp. 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Quetelet, L.A.J. Anthropométrie ou Measure des Différentes Facultés de l’Homme. C. Muquardt: Brussels, Belgium, 1870.

- Withers, R.T.; Craig, N.P.; Bourdon, P.C.; Norton, K.I. Relative body fat and anthropometric prediction of body density of male athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1987, 56, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Withers, R.T.; Whittingham, N. O.; Norton, K.I.; La Forgia, J.; Ellis, M.W.; Crockett, A. Relative body fat and anthropometric prediction of body density of female athletes. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1987, 56, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, A.D. Anthropometric Assessment of Bone Mineral. In Anthropometric Assessment of Nutritional Status; Himes, J.H., Ed.; Wiley-Liss: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 185–96. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, R.C.; Wang, Z.; Heo, M.; Ross, R.; Janssen, I.; Heymsfield, S.B. Total-body skeletal muscle mass: development and cross-validation of anthropometric prediction models. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 796–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.E.L.; Heath, B.H. Somatotyping: Development and Applications. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 73–123.

- Silva, V.S.; Souza, I.; Rieger, E.D.; Ibáñez, H.E.; Vieira, F. Anthropometric characteristics and physical activity level of Orienteers: a pilot study. Rev. Bras. Cineantropom. Desempenho Hum. 2023, 25, e95102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team, version 4.3.1; The R Project for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 16 June 2023).

- Tam, R.; Gifford, J.A.; Beck, K.L. Recent developments in the assessment of nutrition knowledge in athletes. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.T.; Erdman, K.A.; Burke, L.M. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine: Nutrition and Athletic Performance. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mountjoy, M.; Sundgot-Borgen, J.K.; Burke, L.M.; Ackerman, K.E.; Blauwet, C.; Constantini, N.; Lebrun, C.; Lundy, B.; Melin, A.K.; Meyer, N.L.; et al. IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 687–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.T.; Erdman, K.A.; Burke, L.M. American College of Sports Medicine Joint Position Statement. Nutrition and Athletic Performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 543–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrenholtz, I.L.; Melin, A.K.; Garthe, I.; Hollekim-Strand, S.M.; Ivarsson, A.; Koehler, K.; Logue, D.; Lundström, P.; Madigan, S.; Wasserfurth, P.; et al. Effects of a 16-week digital intervention on sports nutrition knowledge and behavior in female endurance athletes with risk of relative energy deficiency in sport (REDs). Nutrients 2023, 15, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trakman, G.L.; Forsyth, A.; Hoye, R.; Belski, R. Australian team sports athletes prefer dietitians, the internet and nutritionists for sports nutrition information. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 76, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valliant, M.W.; Emplaincourt, H.P.; Wenzel, R.K.; Garner, B.H. Nutrition education by a registered dietitian improves dietary intake and nutrition knowledge of a NCAA female volleyball team. Nutrients, 2012, 4, 506–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spronk, I.; Heaney, S.E.; Prvan, T.; O'Connor, H.T. Relationship between general nutrition knowledge and dietary quality in elite athletes. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2015, 25, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyola, F.A.R.; Sánchez, S.G.; Devia, C.P.; Saborido, F.O.; Jurado, J.A.G. Lesiones en trail running, cross-country y Orientación: una revisión sistemática (Trail running, cross-country and Orienteering injuries: a systematic review). Retos 2024, 52, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Güllich, A.; Macnamara, B.N.; Hambrick, D.Z. Predictors of junior versus senior elite performance are opposite: a systematic review and meta-analysis of participation patterns. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 1399–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creagh, U.; Reilly, T. Physiological and biomechanical aspects of orienteering. Sports Med. 1997, 24, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cych, P.; Machowska-Krupa, W. Characteristics of the medallists of the World Masters Orienteering Championships. Appl. Sci. (Basel) 2024, 14, 10039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couture, S.; Lamarche, B.; Morissette, E.; Provencher, V.; Valois, P.; Goulet, C.; Drapeau, V. Evaluation of sports nutrition knowledge and recommendations among high school coaches. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2015, 25, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaney, S.; O'Connor, H.; Michael, S.; Gifford, J.; Naughton, G. Nutrition knowledge in athletes: a systematic review. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2011, 21, 248–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsell, L.C.; Neale, E.P.; Satija, A.; Hu, F.B. Foods, nutrients, and dietary patterns: interconnections and implications for dietary guidelines. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.M.; Hawley, J.A.; Wong, S.H.S.; Jeukendrup, A.E. Carbohydrates for training and competition. J. Sports Sci. 2011; 29, S17–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stellingwerff, T.; Morton, J.P.; Burke, L.M. A framework for periodized nutrition for athletics. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2019, 29, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Female, n = 28 | Male, n = 30 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-elite (n = 18) |

Elite (n = 10) |

Non-elite (n = 17) |

Elite (n = 13) |

|

| Age (years) | 41.7 ± 10.3 | 25.5 ± 6.4* | 37.2 ± 14.6 | 24.3 ± 5.0* |

| OP (years) | 11.3 ± 9.6 | 11.3 ± 5.3 | 11.6 ± 7.6 | 12.1 ± 6.2 |

| OTF (days/week) | 3.0 ± 2.2 | 4.9 ± 1.6* | 3.6 ± 2.1 | 6.1 ± 1.3* |

| OTQ (hours/week) | 4.2 ± 3.3 | 7.7 ± 4.3* | 5.5 ± 5.2 | 8.8 ± 4.0 |

| Body mass (kg) | 60.6 ± 8.5 | 59.5 ± 7.7 | 71.5 ± 14.2 | 65.0 ± 5.5 |

| Height (cm) | 161.3 ± 11.7 | 168.1 ± 6.5 | 174.0 ± 8.8 | 175.1 ± 6.0 |

| Sitting height (cm) | 114.0 ± 20.3 | 100.5 ± 20.2 | 122.0 ± 13.6 | 103.0 ± 18.7* |

| Arms span (cm) | 163.6 ± 7.6 | 168.2 ± 5.8 | 183.2 ± 27.0 | 176.1 ± 6.2 |

| Pectoral ST (mm) | 7.9 ± 5.7 | 8.7 ± 4.4 | 10.9 ± 9.0 | 6.4 ± 3.4 |

| Triceps ST (mm) | 15.8 ± 4.9 | 15.2 ± 5.2 | 9.2 ± 4.4 | 7.0 ± 2.8 |

| Subscapular ST (mm) | 11.5 ± 5.0 | 9.2 ± 2.7 | 12.1 ± 8.2 | 8.4 ± 2.6 |

| Biceps ST (mm) | 5.6 ± 2.4 | 5.3 ± 2.3 | 3.9 ± 1.6 | 3.3 ± 1.0 |

| Iliac crest ST (mm) | 15.4 ± 5.2 | 15.7 ± 7.3 | 15.0 ± 8.7 | 11.0 ± 7.1 |

| Supraspinal ST (mm) | 9.6 ± 4.0 | 8.1 ± 3.4 | 9.9 ± 7.8 | 7.0 ± 3.7 |

| Abdominal ST (mm) | 16.3 ± 6.2 | 13.0 ± 6.0 | 16.8 ± 9.7 | 10.1 ± 6.4* |

| Thigh ST (mm) | 21.5 ± 7.3 | 23.5 ± 8.5 | 10.6 ± 5.8 | 9.2 ± 3.2 |

| Calf ST (mm) | 11.5 ± 4.6 | 13.4 ± 6.7 | 5.7 ± 2.5 | 5.9 ± 2.7 |

| Neck Girth (cm) | 31.6 ± 2.0 | 30.6 ± 1.6 | 37.2 ± 3.0 | 35.1 ± 1.8* |

| RA Girth (cm) | 27.0 ± 2.8 | 25.8 ± 1.9 | 28.8 ± 3.3 | 27.3 ± 2.4 |

| FTA Girth (cm) | 27.3 ± 2.1 | 26.7 ± 1.4 | 30.1 ± 3.1 | 29.1 ± 2.3 |

| Chest Girth (cm) | 88.6 ± 6.4 | 85.5 ± 4.4 | 96.4 ± 8.5 | 90.3 ± 4.5* |

| Waist Girth (cm) | 74.0 ± 7.4 | 67.2 ± 4.5* | 84.2 ± 12.1 | 74.2 ± 5.6* |

| Hips Girth (cm) | 96.0 ± 7.1 | 93.4 ± 10.5 | 95.7 ± 8.2 | 91.2 ± 3.4 |

| TM Girth (cm) | 49.2 ± 3.5 | 50.3 ± 3.2 | 51.1 ± 3.8 | 51.0 ± 3.1 |

| Calf Girth (cm) | 36.0 ± 2.0 | 35.5 ± 2.7 | 37.4 ± 2.8 | 37.2 ± 2.1 |

| Ankle Girth (cm) | 21.5 ± 1.1 | 21.8 ± 2.5 | 22.6 ± 1.8 | 22.2 ± 0.9 |

| BF (%) | 17.9 ± 3.9 | 17.6 ± 6.2 | 11.3 ± 4.8 | 8.4 ± 2.2* |

| BM (kg) | 7.2 ± 1.0 | 7.3 ± 1.1 | 8.6 ± 1.3 | 8.7 ± 0.8 |

| MM (kg) | 21.7 ± 2.3 | 22.1 ± 1.9 | 30.4 ± 3.4 | 30.5 ± 2.0 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.4 ± 3.7 | 21.0 ± 1.9 | 23.6 ± 4.1 | 21.3 ± 2.2 |

| Endomorphy | 3.9 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.8 | 2.1 ± 0.9 |

| Mesomorphy | 4.7 ± 1.6 | 3.5 ± 0.9* | 4.5 ± 1.4 | 4.4 ± 1.3 |

| Ectomorphy | 1.9 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 1.0* | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 3.3 ± 1.2 |

| SDM | 4.6 ± 2.8 | 3.5 ± 1.6 | 5.4 ± 3.5 | 3.2 ± 3.1 |

| SDD | 4.3 | 3.1 | ||

| SAM | 2.0 ± 1.2 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 1.5 ± 1.3 |

| SAD | 1.8 | 1.3 | ||

| GNK (%) | 54.5 ± 12.1 | 63.6 ± 19.6 | 49.2 ± 13.3 | 57.3 ± 19.4 |

| SNK (%) | 35.4 ± 15.7 | 47.5 ± 14.0 | 26.7 ± 15.8 | 40.4 ± 15.5* |

| TNK (%) | 41.4 ± 13.1 | 52.6 ± 13.4* | 33.8 ± 13.8 | 45.7 ± 14.3* |

| MET-min/week | 3941.2 ± 2487.7 | 4249.5 ± 2346.8 | 3727.7 ± 3014.7 | 4451.3 ± 2299.4 |

| kcal/week | 4100.2 ± 2486.1 | 4242.3 ± 1900.7 | 4281.1 ± 2815.8 | 4948.8 ± 2520.0 |

| Variables | MET-min/week | kcal/week | GNK (%) | SNK (%) | TNK (%) | |||||

| F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | |

| Age (years) | −.17 | −.49* | −.19 | −.46* | −.28 | −.09 | −.40* | −.40* | −.41* | −.34 |

| OP (years) | −.02 | −.28 | −.11 | −.27 | −.05 | .01 | .25 | −.07 | .17 | -.05 |

| OTF (days/week) | .42* | .40* | .45* | .37 | .41* | .00 | .53** | .33 | .55** | .25 |

| OTQ (hours/week) | .54** | .64** | .52** | .59** | .38* | .04 | .53** | .23 | .54** | .19 |

| BF (%) | −.39* | −.48* | −.29 | −.42* | −.17 | −.09 | −.25 | −.24 | −.26 | −.22 |

| BM (kg) | −.40* | −.18 | −.22 | −.11 | −.13 | .15 | −.02 | −.03 | −.06 | .03 |

| MM (kg) | −.18 | −.45* | −.01 | −.37 | .08 | .25 | .13 | .13 | .13 | .18 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | −.18 | −.57** | −.10 | −.50** | .01 | −.07 | −.13 | −.22 | −.10 | −.19 |

| Endomorphy | −.32 | −.44* | −.22 | −.37 | −.21 | −.09 | −.38* | −.26 | −.37 | −.23 |

| Mesomorphy | −.12 | −.47* | −.08 | −.45* | .04 | .02 | −.10 | −.07 | −.07 | −.05 |

| Ectomorphy | .11 | .59** | .02 | .54** | −.01 | .12 | .27 | .21 | .21 | .20 |

| SDM | .06 | .19 | .01 | .21 | .10 | −.18 | −.01 | −.25 | .03 | −.25 |

| SAM | .07 | .13 | .02 | .15 | .12 | −.13 | −.02 | −.21 | .02 | −.21 |

| GNK (%) | .23 | −.09 | .25 | −.13 | - | - | .50** | .55** | .74** | .77** |

| SNK (%) | .15 | .15 | .10 | .10 | .50** | .55** | - | - | .95** | .96** |

| TNK (%) | .19 | .09 | .17 | .04 | .74** | .77** | .95** | .96** | - | - |

| MET-min/week | - | - | .97** | .99** | .23 | −.09 | .15 | .15 | .19 | .09 |

| Kcal/week | .97** | .99** | - | - | .25 | −.13 | .10 | .10 | .17 | .04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).