1. Introduction

Individuals with overweight or obesity often encounter significant challenges in meeting daily physical activity recommendations compared to their peers at a healthy weight. Moreover, even young people, regardless of their weight, are not physically active enough. In Romania, for example, over half of the population aged 15-24 (57% men, 51% women) rarely or never practice sport or physical activity (compared to 27% and 42% in the EU) [

1]. Less than 20% of individuals aged 15–24 engage in physical hobbies or independent activities at least once a week, with a marked decline to just 7.3% among adults aged 25–34 [

2]. Such patterns contribute to diminished fitness and increased weight gain during adolescence and early adulthood.

Body composition is defined as the ratio of lean body mass to fat mass expressed as a percentage of total body weight. Measuring these values can help understand an individual's physical condition and fitness. Recent studies have underscored a well-established relationship between body composition and physical fitness, as well as their close interconnection [

3]. Besides, body composition values provide essential information related to nutritional, health, and fitness status, making it a helpful factor in assessing overall well-being [

4].

Regular engagement in appropriate physical activity—adapted to cultural context, gender, age, and individual preference, and consistently maintained throughout youth and adulthood—offers a multitude of health benefits. These include reduced risk for non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, certain cancers, and depression. Enhanced musculoskeletal health, increased strength, and improved functional integrity are further advantages. As a central factor in energy expenditure, physical activity plays a beneficial role in regulating energy balance, improving central obesity indices [

5], and body weight.

A meta-analysis, based on 41 independent studies, concludes that regular physical activity, including more time spent actively, not only protects the health of students but also improves their academic performance [

6]. Physical activity is beneficial for the development of cognitive, motor, and social skills, as well as for good metabolic and musculoskeletal health. There is also an effect of improving learning performance and attention, and of reducing anxiety and depression [

7].

Overweight and obesity are not only physical conditions, but are also associated with psychological consequences. In the current generation (Gen Z, born between 1995 and 2005), ubiquitous online connectivity, along with prolonged sedentary time, induced the phenomenon of Fear of Missing Out (FoMO). The phenomenon originates from psychological deficits in people's competence and relatedness needs. [

8].

Social comparison processes engendered by FoMO are associated with lower self-esteem [

9], thereby compounding challenges to healthy self-perception in comparison with highly edited, filtered, and unrealistic portrayals of others' lives. Contemporary beauty standards—largely shaped by media and marketing—have contributed to unrealistic body ideals, driving body dissatisfaction, disordered eating, and elevated social physique anxiety among young women [

10]. The transition from adolescence into adulthood intensifies these effects, as emerging adults face novel social pressures and shifting norms around body image. Research consistently demonstrates that self-esteem and physical self-perception are pivotal for mental health, influencing motivation, behavior, life satisfaction, and overall well-being. Anxiety, FoMO, and loneliness are proven as mediators between negative emotional states and addictive behaviors, such as compulsive eating [

11].

Empirical studies have concluded that physical activity helps individuals cope with stress and improve emotional regulation, thereby enhancing social interaction [

12,

13]. In addition to its direct physiological and psychological benefits, physical activity also induces improvements in self-confidence, a heightened sense of control, and increased capacity to confront challenges [

14]. Physical fitness, particularly among individuals with excess weight, has been shown to contribute positively to functional efficiency and overall quality of life [15-17].

In response to these concerning trends, a targeted intervention was designed, conducted, and evaluated in a group of overweight and obese young adult women. The intervention yielded measurable improvements in physical fitness and body composition among participants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants.

A sample of 25 young adult women, aged 18-24 years (x̅ = 20.68 ± 1.6), with a BMI greater than 25 kg/m², were measured and evaluated before and after a 20-week intervention. They were recruited from university students in the first and second years of study. Of the total number of participants, based on a mean BMI calculation of 30.69 kg/m2, 12 (48%) were overweight and 13 (52%) were obese. Besides BMI, the other inclusion criteria were the state of health and the requirement to actively participate in physical education lessons, meaning they were not medically exempt from physical effort.

Before enrollment in the exercise program, all participants provided informed consent to participate in the study, respecting established ethical standards. The data were kept anonymous to respect the confidentiality of personal information.

2.2. Anthropometric Variables Measures.

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated based on direct measurements of students' weight and height. The normal range for women's BMI is usually considered to be 18 to 25, with more than 25 considered overweight and above 30 obese. The body fat percentage (BF), muscle tissue percentage (MT), and weight were measured using bioelectrical impedance. Healthy ranges for young women are BF 25–29.9%, MT 24.4–30.2%. Additionally, the waist and hip circumferences were measured to calculate the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR). A woman's waist circumference above 80cm is an indicator of visceral fat and a risk factor for health, as well as a WHR above 0,8 [

18]. Furthermore, a waist circumference greater than 88 cm and a waist–hip ratio of 0.85 or higher substantially increase the risk of metabolic complications [

19].

2.3. Intervention.

The intervention consisted of 60-minute sessions, twice a week, for 20 weeks, of ergonomic exercises with effort volume, intensity and complexity adapted to the practitioners' possibilities and needs. The physical effort was mostly of moderate intensity, with a target heart rate zone of 120-140 beats per minute. A variety of gym-based programs (Pilates, aerobic dance, circuit training using body weight, catch ball, and stretching) were used in different combinations. The aim was to provide a full range of motion, gradually increased in complexity and to stimulate participants’ interest and adherence. Each session incorporated different exercise modalities to address multiple aspects of physical fitness, including cardiovascular endurance, muscular strength, flexibility, and coordination. The program was divided into distinct phases (

Table 1), each introducing new forms of activity while maintaining core components to reinforce habits and encourage engagement.

Pilates is an integrated system of physical exercise intended to promote a leaner physique, enhanced bodily symmetry, and improved overall health. The method comprises a sequence of movements that involve the body, mind, and regulated breathing [

20]. Its primary goal is to establish muscular equilibrium by strengthening underdeveloped muscles and relieving areas of tension, thereby fostering greater control, strength, and flexibility throughout the body.

Aerobic dance improves cardiovascular and respiratory endurance, coordinative capacity, and spatial-temporal orientation [

21]. The style of gesture and fluency of movement set to a musical background enhances group coordination, rhythm, and natural feminine grace. Aerobic dancing was alternated with exercise programs on the machines in the gym, to keep the effort at an accessible level for all participants.

Catchball is a team sport for women derived from volleyball. Catchball promotes physical activity among women of all ages and fitness levels, encouraging participation after varying periods of inactivity [

22].

In the first and last weeks, 10 minutes were dedicated to physical tests, which were performed after warm-up.

2.4. Physical Performance Measures

The physical tests were conducted pre- and post-intervention, measuring upper and lower body strength as well as facial and dorsal trunk strength. For upper body strength, knee push-ups were the most convenient test for the group's physical abilities. Squads for the lower body, abs and prone trunk extensions were the other physical tests, all measuring the maximum number of repetitions in 30 seconds. The sessions were conducted at the Bucharest University of Economic Studies' sports facilities by specialists in physical education and rehabilitation.

2.5. Data Analysis

For improvement estimation between the two moments of measurements in a small sample size, the t (student) test for paired data was the statistical tool used, with a significance level set at 0.005. Further, we compared the “t” score calculated for the actual study, using the standard t-table cutoffs (df = n-1). Cohen’s effect size was also calculated for the difference between the two measurements and testing moments, and as a measure of the magnitude and practical importance of the observed difference. For analysing the data, the software IBM SPSS Statistics 20 was used.

3. Results

This quasi-experimental study design compares baseline parameters of body composition and fitness level with those measured at the end of the exercise program. The row data are presented in Annexe A1 and A2.

The anthropometric results are displayed in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Anthropometric Parameters.

Table 1.

Anthropometric Parameters.

| Parameter |

Pre- |

Post- |

Δ |

t |

p |

d |

| Weight |

84,94 |

80,32 |

-4,68 kg |

3.22 |

.004 |

0,644 |

| BMI |

30,69 |

28,68 |

-2,01kg/m2

|

3.21 |

.004 |

0,642 |

| FM |

44.45 |

40,38 |

-4,07% |

5,52 |

.000 |

1,05 |

| MM |

24,27 |

26,29 |

+2,02% |

5.87 |

.000 |

1,17 |

| Waist circ. |

84,94 |

80,32 |

-4,62 cm |

3.94 |

.001 |

0,78 |

| Hip circ. |

111,9 |

103,9 |

-8 cm |

2.85 |

.009 |

0,57 |

| WH Ratio |

0,7576 |

0,7436 |

- 0,014 |

1,92 |

.066 |

0,38 |

Compared with the critical t value < 2,064 for (n-1) 24 degrees of freedom, two tails, [

23] the data displayed in the biometric parameters table are statistically significant, except for the WHR. Based on benchmarks prescripted by Cohen (1988), effect size is considered small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d = 0.8)

The weight and BMI parameters evolved similarly, decreasing in the same pass, while the height remained constant. Both anthropometric parameters are correlated, their variation depending on body weight. Fat mass and muscular tissue had a divergent evolution; while fat mass decreased by 4 per cent, muscular tissue increased by 2 per cent. The waist circumference, as expected, got thinner as the weight decreased. The difference in waistline was 4.62 cm, along with a decrease in hip circumference of 8 cm. All those measurements are statistically significant, with an effect size (d) of medium to large magnitude.

The waist-hip ratio exhibits a minimum decrease as a result of the concomitant and significant decrease in both its components (waist and hip). Thus, this parameter is discussed because it provides clues about central fat, and subsequently about visceral fat.

Table 2.

Physical test results pre- and post-intervention.

Table 2.

Physical test results pre- and post-intervention.

| Physical test |

Pre- |

Post- |

Δ CV |

| Abs/30s |

12.28 ±3.09 |

16.20±2.66 |

+3.92 0.16 |

| Prone trunk extensions/30s |

16.20 ±4.62 |

19.92±4.45 |

+3.72 0.22 |

| Knee pushups/30s |

10.16±6.25 |

12.68±6.45 |

+2.52 0.51 |

| Squads/30s |

17.72±3.01 |

22.24±3.35 |

+4.52 0.15 |

| Statistical indicators |

t(24) =8,72 |

p<.003 |

d=1,74 |

The Abs test measures core strength and endurance, assessing the ability to engage and control abdominal muscles over a 30-second period. Prone trunk extensions focus on the back muscles, evaluating the ability to extend the spine and maintain stability during a 30-second test. Knee pushups test upper body strength, specifically targeting chest and arm muscles, and measuring endurance over a half-minute duration. Squats assessed lower body strength and flexibility, focusing on the ability to perform the movement correctly and sustain it for 30 seconds.

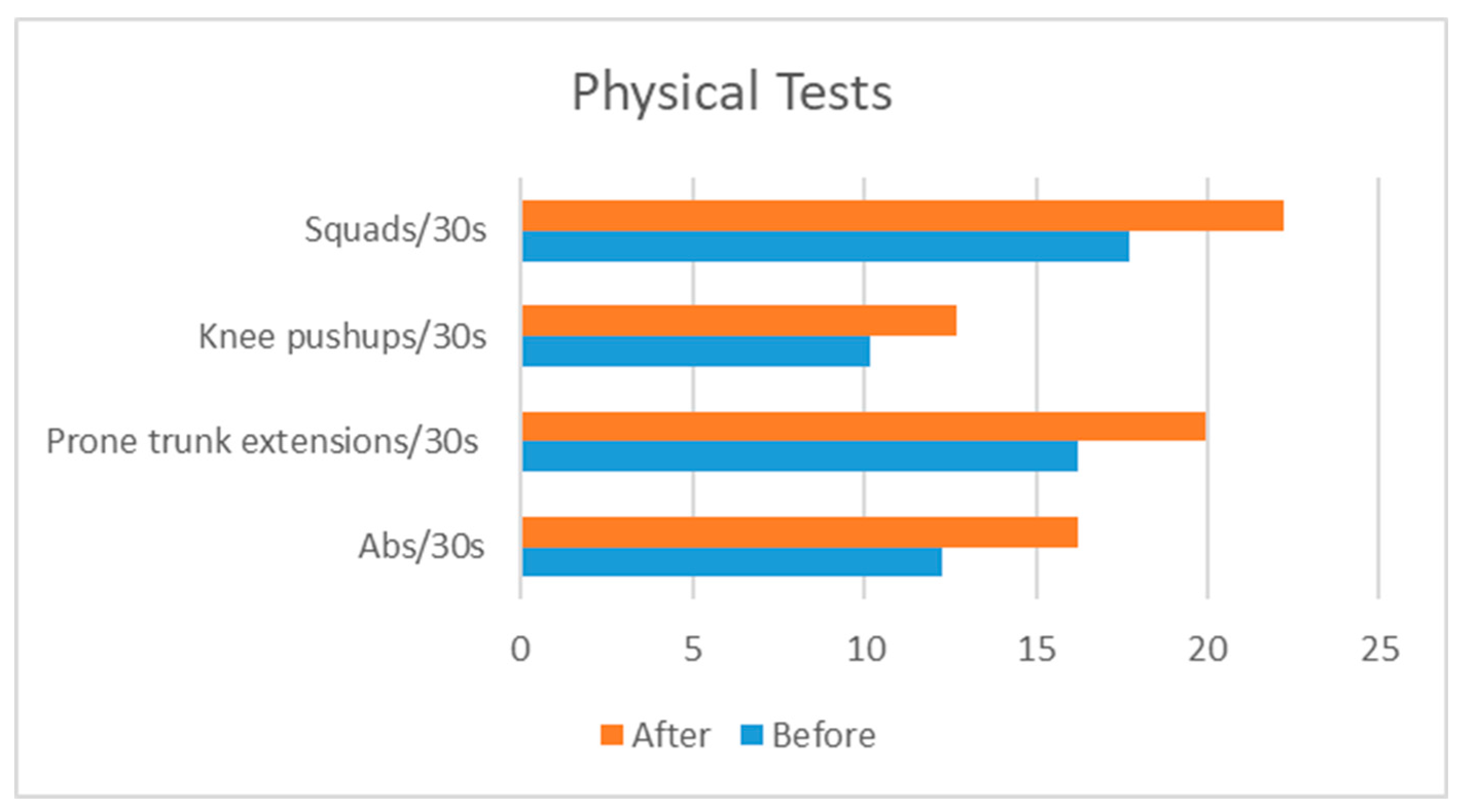

Participants recorded significant progress in all four tests; however, the real values and group evolution varied. The best improvement was observed in squats, followed by the two tests assessing trunk-lifting strength, as shown in

Figure 1. In terms of upper body strength, not only was the progress smaller, but it was also uneven. The variability coefficient of 0.5 demonstrates this lack of homogeneity. Overall, the effect of the intervention on the group of overweight female fitness progress was more than large (d = 1.74> 0.8).

4. Discussion.

This study aims to evaluate the effect of an adapted exercise program on fitness levels and body composition in overweight and obese women, with a particular focus on improvements in physical performance and body metrics over a 20-week intervention period.

Research to combat the effects of obesity has grown along with the magnitude of the phenomenon, which has reached global proportions. One of the causes of this “Globesity” is the sedentary lifestyle. Globally, 830,000 deaths can be attributed to physical inactivity each year [

24]. Furthermore, the generation we address in our research experienced sanitary restrictions during their teenage years due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The decrease in fitness level and the increase in BMI values due to these restrictive measures are well-documented. In a similar age and gender sample, a decrease in physical abilities was calculated between 10 and 28 per cent [

25]. Remote learning left gaps in their knowledge, abilities and physical competencies. Motor illiteracy encompasses challenges in motor development, including diminished competence and confidence, which may be exacerbated by factors such as obesity. Overweight and, especially, obesity are substantial obstacles, intensifying adverse outcomes across affective, behavioral, and physical aspects of their lives, thereby compounding difficulties for those affected [

26].

The initial distribution of participants in our study was as follows:

45% were overweight, with a BMI of 25-29.4, and

55% were obese, having a BMI of 30-44.5kg/m².

Twenty weeks later, measurements show a change in percentage:

The gratifying result of our applied program was to lower the weight of 30 per cent of obese women and to achieve a normal weight range for four young women. Similar results were obtained in groups of obese and overweight women performing aerobic and resistance exercises [

27].

The most significant effect obtained through our intervention is the increase in muscle mass percentage (d = 1.17; p<.000), which is concurrent with a decrease in fat mass. This parameter was identified in six studies from a meta-analysis [

28], which, on the contrary, found that the increase in muscle mass was not statistically significant.

In the pre-intervention waist circumference measurement, 8 participants had a waist circumference of less than 80 cm, which is considered the limit of health risk. In the final session, 16 of the women had a waist circumference of less than 80 cm, representing a 100% improvement in this anthropometric parameter. A meta-analysis concluded that the most effective exercise program for reducing waist circumference is a combination of moderate aerobic intensity and low-to-moderate resistance load [

29], which has been proposed as part of the physical exercise program intervention.

Most studies that have samples of overweight and obese people do not record the progress of fitness levels through physical tests. At most, progress is measured in static tests such as flexibility, sitting on a chair and standing up [

30], or handgrip strength [

31].

The results of the physical test in this research may be a benchmark for future studies in homogenous groups of overweight young women.

For an overweight person, awareness of their body size and volume can lead to social reluctance, timidity, and low self-confidence, which is reflected in their posture and attitudes [

32]. Furthermore, the socio-cultural patterns associate fatness with laziness, and overweight people are easily categorizated as being slow [

33] or dawdling.

Since all participants in this study are students in their first and second years of study, the transition to university life may bring about notable changes, including shifts in social networks, increased academic pressures, and exposure to new social norms and standards of body image. Young adults, especially students, often face challenges that increase social anxiety, including Social Physique Anxiety. This is a concept within self-presentation theory that describes the anxiety individuals experience when they expect negative judgments about their physical appearance [

34].

Shifting the focus away from appearance and emphasizing the physical and mental benefits of exercise, we could inspire our students with physical self-acceptance and confidence in their own strengths. The feeling of competence and physical literacy provides security in independent approaches, as well as continuity in physical activities.

Physical education strategies that foster autonomy, motivation, and self-assurance are effective means of encouraging individuals to engage in physical activity and mitigate the impacts of obesity and overweight.

Young women's membership in a group that shares similar concerns about physical appearance and a common desire to improve it may explain why participants adhered to the exercise program. Exercise in a supportive team environment serves as an effective motivator for individuals, including those managing weight concerns [

35]. Team development starts with personal commitment and acknowledgement of individual differences in values, skills, and needs. Team members can utilise constructive feedback from their peers to evaluate their own strengths and areas for improvement. A strong team spirit is cultivated through interpersonal connections and communication that are grounded in mutual respect and trust among all team members [

36].

Sustained physical activity should be complemented by a balanced diet and meaningful lifestyle changes to maximize its benefits. Future research should focus on combining tailored exercise programs with specialized psychological and dietary advice.

The homogeneity of the sample in terms of age, gender, education level, and body composition may be a factor that compensates for the limitation related to the small number of cases studied.

We conducted the study intervention in a specific social and cultural context; diverse cultures and societies may hold rather diverse views on women's body weight, self-image and self-efficacy. Consequently, the results may not be valid in any cultural context.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that a structured, ergonomic exercise program tailored to the needs of overweight and obese young women can produce significant improvements in both body composition and physical fitness. Over the 20-week intervention, participants experienced meaningful reductions in weight, body fat percentage, BMI, and waist and hip circumferences, alongside increases in muscle mass and enhanced performance in physical fitness tests. Notably, the proportion of participants with a waist circumference below the health risk threshold doubled, and several individuals transitioned from obese to overweight or normal weight categories.

Beyond the physiological benefits, the program fostered greater adherence and motivation, likely supported by the group specificity and shared goals. These findings underscore the importance of developing inclusive, supportive, and contextually tailored exercise interventions for young women who face body weight challenges. Such programs not only address physical health but may also contribute to improved self-esteem, social confidence, and psychological well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.V., C.P., C.F., C.N., R.C.; methodology, P.V., C.P., C.F., C.N., R.C.; software, P.V., C.P., C.F., C.N., R.C.; validation, P.V., C.P., C.F., C.N., R.C.; formal analysis, P.C and P.V, investigation, P.V., C.P., C.F., C.N., R.C.; resources, P.V., C.P., C.F., C.N., R.C.; data curation, P.V., C.P., C.F., C.N., R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.V, P.C.; writing—review and editing, N.C., H.C., C.V; visualization, P.V., C.P., C.F., C.N., R.C.; supervision, P.V., C.P., C.F., C.N., R.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because the research was conducted in stable educational environments that are commonly accepted and involve normal educational practices.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| FM |

Fat Mass |

| MT |

Muscular Tissue |

| WHR |

Weist Hip Ratio |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Anthropometrics – initial data.

Table A1.

Anthropometrics – initial data.

| No. |

Age |

Height

(m)

|

Weight

(kg)

|

BMI |

FM

%

|

MT

%

|

Weist

(cm)

|

Hip

(cm)

|

| 1 |

21 |

1.59 |

66.6 |

26.3 |

40.2 |

25.5 |

78.5 |

98.5 |

| 2 |

20 |

1.78 |

82.8 |

26.1 |

41.3 |

25.1 |

91 |

105 |

| 3 |

20 |

1.70 |

74 |

25.6 |

37.2 |

27.5 |

73 |

103 |

| 4 |

20 |

1.64 |

79.2 |

29.4 |

42.6 |

25.4 |

80 |

109 |

| 5 |

19 |

1.63 |

67.2 |

25.3 |

39 |

25.9 |

76.5 |

97.5 |

| 6 |

21 |

1.69 |

71.5 |

25 |

38.1 |

26.5 |

72 |

103 |

| 7 |

19 |

1.62 |

73.8 |

28.1 |

39.2 |

27.1 |

77 |

107 |

| 8 |

21 |

1.66 |

70.4 |

25.5 |

32.7 |

30.1 |

76 |

102 |

| 9 |

20 |

1.62 |

69.8 |

26.6 |

41.9 |

24.5 |

70 |

103 |

| 10 |

25 |

1.67 |

72.1 |

25.9 |

39.4 |

26.2 |

83.5 |

106 |

| 11 |

21 |

1.79 |

83.9 |

26.2 |

39.4 |

26.4 |

80 |

111 |

| 12 |

20 |

1.54 |

60 |

25.3 |

40 |

24.7 |

76 |

97.5 |

| 13 |

21 |

1.70 |

87.7 |

30.3 |

44.2 |

24.8 |

81 |

113 |

| 14 |

21 |

1.58 |

76.2 |

30.1 |

46 |

23.4 |

84.5 |

104.5 |

| 15 |

21 |

1.61 |

80.8 |

31.2 |

44.7 |

24.6 |

80 |

111 |

| 16 |

20 |

1.68 |

93.5 |

33.1 |

47.5 |

23.4 |

88.5 |

115 |

| 17 |

20 |

1.67.5 |

84.9 |

30.3 |

42.1 |

26 |

86 |

102 |

| 18 |

20 |

1.62 |

101.4 |

38.6 |

55.5 |

19.4 |

100.5 |

128 |

| 19 |

19 |

1.71 |

122 |

41.7 |

54.9 |

20.3 |

106 |

136.5 |

| 20 |

19 |

1.70 |

90.1 |

31.2 |

46.1 |

23.8 |

88 |

119.5 |

| 21 |

20 |

1.68 |

83.8 |

30 |

44.3 |

24.6 |

80 |

111 |

| 22 |

20 |

1.70 |

98.1 |

33.9 |

51.2 |

21.3 |

91 |

127.5 |

| 23 |

23 |

1.50.5 |

88.6 |

39.1 |

56.6 |

18.6 |

85.5 |

123 |

| 24 |

24 |

1.64 |

101.9 |

37.9 |

47.1 |

24.2 |

99 |

126 |

| 25 |

20 |

1.58 |

111.1 |

44.5 |

60 |

17.5 |

120 |

138 |

| X |

20.6 |

1.65 |

83.66 |

30.69 |

44.45 |

24.27 |

84.94 |

111.90 |

Table A2.

Anthropometrics – Results after intervention.

Table A2.

Anthropometrics – Results after intervention.

| No. |

Age |

Height

(m)

|

Weight

(kg)

|

BMI |

FM

%

|

MT

%

|

Weist

(cm)

|

Hip

(cm)

|

| 1 |

21 |

1.59 |

60.8 |

24 |

35 |

27.8 |

72 |

97 |

| 2 |

20 |

1.78 |

81.2 |

25.6 |

36.3 |

28.1 |

83 |

104 |

| 3 |

20 |

1.70 |

68.9 |

23.8 |

32.1 |

29.8 |

70 |

101 |

| 4 |

20 |

1.64 |

73.2 |

27.2 |

37.7 |

27.7 |

75 |

104 |

| 5 |

19 |

1.63 |

61.5 |

23.1 |

32.4 |

29.1 |

70 |

95 |

| 6 |

21 |

1.69 |

68.9 |

24.1 |

33.2 |

29.2 |

71 |

102 |

| 7 |

19 |

1.62 |

72.4 |

27.6 |

39.6 |

26.7 |

77 |

106 |

| 8 |

21 |

1.66 |

73 |

26.5 |

34.9 |

29.2 |

78 |

103 |

| 9 |

20 |

1.62 |

68 |

25.9 |

39 |

26.2 |

68 |

100 |

| 10 |

25 |

1.67 |

73.7 |

26.4 |

34.3 |

29.5 |

83 |

106 |

| 11 |

21 |

1.79 |

81.2 |

25.3 |

36.5 |

27.9 |

77 |

110 |

| 12 |

20 |

1.54 |

60.9 |

25.7 |

38.2 |

26.6 |

77 |

98 |

| 13 |

21 |

1.70 |

77.6 |

26.9 |

36.7 |

28.2 |

76 |

105 |

| 14 |

21 |

1.58 |

71 |

28.4 |

43.1 |

24.6 |

79 |

104 |

| 15 |

21 |

1.61 |

73.1 |

28.2 |

38.8 |

27.4 |

75.5 |

105 |

| 16 |

20 |

1.68 |

83.2 |

29.5 |

43.5 |

24.9 |

84 |

95 |

| 17 |

20 |

1.67.5 |

97.3 |

34.7 |

49 |

22.8 |

92 |

116 |

| 18 |

20 |

1.62 |

82.1 |

31.3 |

44.7 |

24.6 |

87.5 |

115 |

| 19 |

19 |

1.71 |

121.3 |

41 |

53.5 |

21 |

101 |

135 |

| 20 |

19 |

1.70 |

76.3 |

26.4 |

37.2 |

27.8 |

71.5 |

106 |

| 21 |

20 |

1.68 |

82.7 |

29.3 |

42.3 |

25.6 |

80 |

108 |

| 22 |

20 |

1.70 |

95.5 |

33 |

47.9 |

23.1 |

88 |

126 |

| 23 |

23 |

1.50.5 |

89.7 |

39.6 |

51.9 |

21.9 |

86 |

123 |

| 24 |

25 |

1.64 |

77.8 |

28.9 |

38.6 |

27.6 |

79.5 |

108.5 |

| 25 |

21 |

1.58 |

86.7 |

34.7 |

53.2 |

19.9 |

107 |

121 |

| X |

20,68 |

1.65 |

72.32 |

28.68 |

40,38 |

26.29 |

80,32 |

107,74 |

References

- National Institute of Public Health. Available online: https://insp.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Analiza-de-situatie-campanie-AF-2024.pdf (accessed on 12.08.2025).

- National Institute of Statistics. Available online: https://insse.ro/cms/ (accessed 11.08.2025).

- Rybakova, E., Shutova, T., Vysotskaya, T. Sports training of ski jumpers from a springboard based on body composition control and physical fitness. J Phys Educ Sport; 2020, 20:752–8.

- Holmes C., Racette S. The utility of body composition assessment in nutrition and clinical practice: An overview of current methodology. Nutrients; 2021, 13(8):2493.

- Przybylski A.K., Murayama K., DeHaan C.R., Gladwell V. Motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29:1841–1848. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa A, Whiting S, Simmonds P, Scotini Moreno R, Mendes R, Breda J. Physical Activity and Academic Achievement: An Umbrella Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Aug 17;17(16):5972. [CrossRef]

- Ratey, J.J., Hagerman, E. Spark! The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain, Ed. Herald, Bucharest, Romania, 2021, p. 132.

- Servidio R, Soraci P, Griffiths MD, Boca S, Demetrovics Z. Fear of missing out and problematic social media use: A serial mediation model of social comparison and self-esteem. Addict Behav Rep. 2024 Mar 5;19:100536. [CrossRef]

- Pop, C., Ciomag, V. The Relationship between Subjective Parameters of Well-being in a Sample of Young Romanian Women, Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2014, Vol 149, Pages 737-740, ISSN 1877-0428. [CrossRef]

- Eler, N. Seasonal Changes in Body Composition in Elite Male Handball Players. International Journal of Disabilities Sports and Health Sciences, 2024, 7(2), 274-281.

- Meynadier, J., Malouff, J. M., Schutte, N. S., & Loi, N. M. Using Social Media to Cope with Psychological Distress and Fear of Missing Out: The Role of Social Media Reward Expectancies in Social Media Addiction. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 2025, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Ugelta S, Rahmi U, Sutresna N, Pitriani P, Dewi Rahayu Fitrianingsih A, Zaeri Sya'rani A. The Effects of Isotonic and Isometric Training on Young Women’s Waist Circumference. Ann Appl Sport Sci 2022; 10 (S1). [CrossRef]

- Bell S. L., Audrey S., Gunnell D., Cooper A., Campbell R. The relationship between physical activity, mental wellbeing and symptoms of mental health disorder in adolescents: A cohort study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2019, 16, 1–12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu J., Zhu L., Dong X., Sun Z., Cai K., Shi Y., Chen A. Relationship between Physical Activity and Emotional Regulation Strategies in Early Adulthood: Mediating Effects of Cortical Thickness. Brain Sci. 2022; 12:1210. [CrossRef]

- Schrempft S., Jackowska M., Hamer M., Steptoe A. Associations between social isolation, loneliness, and objective physical activity in older men and women. BMC Public Health, 2019, 19, 1–10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marconcin P., Werneck A. O., Peralta M., Ihle A., Gouveia É. R., Ferrari G., Menezes A. M. B., Peralta M., Ihle A., Sarmento H., Marques A. The association between physical activity and mental health during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 2022, 22(1), 209. [CrossRef]

- McAuley E., Wœjcicki T. R., White S. M., Mailey E. L., Szabo A. N., Gothe N., Olson E. A., Mullen S. P., Fanning J., Motl R. W., Rosengren K., Estabrooks P. Physical activity, function, and quality of life: Design and methods of the FlexToBa trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 2012, 33(1), 228–236. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Waist Circumference and Waist–Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert Consultation, 2008. ISBN 978 92 4 150149 1, Available online at https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44583/9789241501491_eng.pdf (accessed on 14.08.2025).

- Siegel, H. M., Wyatt, H.R., Hill, J.O. Chapter 24 - Obesity: Overview of Treatments and Interventions, Editor(s): Ann M. Coulston, Carol J. Boushey, Mario G. Ferruzzi, Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Disease (Third Edition), Academic Press, 2013, Pages 445-464, ISBN 9780123918840. [CrossRef]

- Popescu, V. The Evolution and Benefits of the Pilates Method. Marathon 2025, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Ciomag, R. V., & Dinciu, C. C. (2013). Aerobics – Modern Trend in the University Educational Domain. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 92, 251-258. [CrossRef]

- Filip, C., Ciomag, V. Catchball Versus Volley. Marathon. 2018, 10(2). https://marathon.ase.ro/pdf/vol10/vol10_2/2%20ciomag,hantau.pdf.

- DataTab Available online at https://datatab.net/tutorial/t-distribution (accessed on 29.07.2025).

- WHO Global status report on physical activity 2022. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240064119, (accessed on 29.07.2025).

- Ciomag, R. V., Pop, C. L., Nae, I. C., & Filip,C. Post-COVID-19 pandemic effect on university students' fitness level. Revista Românească pentru Educaţie Multidimensională, 16(3), 193-205. [CrossRef]

- Trecroci, A.; Invernizzi, P.L.; Monacis, D.; Colella, D. Physical Illiteracy and Obesity Barrier: How Physical Education Can Overpass Potential Adverse Effects? A Narrative Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 419. [CrossRef]

- Guner Çicek; Ozdurak Singin, R.H. Effect of aerobic and resistance exercises on body composition and quality of life in overweight and obese women: a randomized control trial. Universa Medicina, 2023, 42(1), pp. 70–83. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Lee, J. Effects of Exercise Interventions on Weight, Body Mass Index, Lean Body Mass and Accumulated Visceral Fat in Overweight and Obese Individuals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2635. [CrossRef]

- Hao Z, Liu K, Qi W, Zhang X, Zhou L, Chen P. Which exercise interventions are more helpful in treating primary obesity in young adults? A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. Arch Med Sci. 2022 Sep 9;19(4):865-883. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moraes, F. C., Cabral, M. A. B., Soares, T. D., Grutzmacher, Q. C., Martins, J. S., & Branco, J. C. Efeito de um programa de exercí cio fí sico sobre medidas antropométricas e aptidão fí sica em mulheres obesas. RBONE - Revista Brasileira De Obesidade, Nutrição E Emagrecimento, 2020, 13(82), 960-967. Recuperado de https://www.rbone.com.br/index.php/rbone/article/view/1099.

- Miranda H, Bentes C, Resende M, Netto CC, Nasser I, Willardson J, Marinheiro L. Association between handgrip strength and body composition, physical fitness, and biomarkers in postmenopausal women with metabolic syndrome. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2022 Mar;68(3):323-328. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pop, C. Physical Activities for Overweight and Obese Children–an Inclusive Approach. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 163, 142–147. [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, M. C. D. M. P., Sato, P. D. M., & Scagliusi, F. B. Under the ‘weight’ of norms: Social representations of overweight and obesity among Brazilian, French and Spanish dietitians and laywomen. Social Science & Medicine, 2022, 298, 114861. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.; Bashir, M.; Zafar, L. Efficacious Self Presentation and Social Physique Anxiety: The Role of Depression. Policy J. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2024, 2, 127–139.

- Sarte, A. E., & Quinto, E. J. M. Understanding the importance of weight management: a qualitative exploration of lived individual experiences. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 2024, 19(1). [CrossRef]

- Stratone, M.-E.; Vătămănescu, E.-M.; Treapăt, L.-M.; Rusu, M.; Vidu, C.-M. Contrasting Traditional and Virtual Teams within the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic: From Team Culture towards Objectives Achievement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4558. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).