1. Introduction

The mass distribution within spiral galaxies remains a cornerstone of modern extragalactic astrophysics. While rotation curves and gravitational lensing have long provided the bulk of our understanding regarding galactic mass profiles [

1,

2], these methods often face challenges in disentangling the relative contributions of stellar populations, gas, and dark matter in the low-surface-brightness outskirts of spiral systems. A rare but highly effective alternative arises from the study of overlapping galaxy pairs. In these fortuitous line-of-sight alignments, the foreground galaxy partially obscures the background galaxy; at the same time, the background galaxy effectively serves as a “light box,” illuminating the foreground disk from behind. This geometry enables a direct measurement of the foreground galaxy’s extinction and obscuration properties, which are closely tied to the mass density distribution [

3,

4,

5].

This paper examines the remarkable alignment of the spiral galaxies LEDA 2073461 and SDSS J115331.86+360024.2 (for short: SDSS J115331.86 in this paper), located approximately one billion light-years from Earth. Identified through the Galaxy Zoo citizen science project and subsequently imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) as part of the “Gems of the Galaxy Zoos” (Zoo Gems) program [

6], this pair presents a near-perfect optical overlap. Unlike merging systems where tidal forces and morphological distortions complicate the analysis of mass distribution, LEDA 2073461 and SDSS J115331.86 are non-interacting “ships passing in the night.” This lack of physical interaction preserves the structural integrity of both galaxies, making them ideal for high-precision obscuration mapping without the confusion of starburst-driven turbulence or tidal heating.

The obscuration pattern observed in this system—the attenuation of light from the background galaxy as it passes through the foreground disk—provides a direct probe of the foreground galaxy’s mass density distribution [

7,

8]. By exploring the optical depth across the face of the foreground galaxy, we can derive independent constraints on the total mass distribution. In particular, the resolved structure of the obscuration field allows us to trace the matter distribution well beyond the bright stellar core, offering a clearer view of the galaxy’s outer disk and potentially yielding insight into the physical mechanisms responsible for the formation and maintenance of its spiral arms.

2. General Description of the Two Overlapping Galaxies LEDA 2073461 and SDSS J115331.86

Figure 1A is the original color image of the two overlapping galaxies LEDA 2073461 and SDSS J115331.86. The galaxy pair LEDA 2073461 and SDSS J115331.86 forms an exceptional overlapping system in which LEDA 2073461 is a face-on spiral galaxy in the foreground, while SDSS J115331.86 lies directly behind it along the same line of sight. This configuration provides a rare and powerful opportunity to study the dust, gas, and mass distribution within the foreground disk using the background galaxy as a natural illumination source.

LEDA 2073461, the foreground galaxy, presents a nearly face-on orientation, allowing an unobstructed view of its spiral structure and enabling extinction measurements across its entire disk. As the light from the background galaxy passes through LEDA 2073461, it is selectively absorbed and scattered by dust and interstellar material. Because the foreground disk is viewed face-on, the resulting attenuation pattern directly traces the radial and azimuthal variations in dust content and mass surface density, without the geometric complications introduced by high inclination.

SDSS J115331.86, the background galaxy, is a more distant spiral whose extended light distribution serves as an ideal “backlight.” Its surface brightness provides a stable reference against which the extinction caused by LEDA 2073461 can be measured with high spatial precision. The absence of tidal distortions or morphological disturbances in either galaxy indicates that the pair is non-interacting, confirming that the overlap is a chance alignment rather than a merger or close encounter.

This system is particularly valuable for probing the mass density distribution of the foreground galaxy. By mapping the spatially resolved attenuation of SDSS J115331.86’s light, researchers can derive the optical depth across the face of LEDA 2073461 and infer the distribution of dust and baryonic matter throughout its disk. Because the galaxy is face-on, these measurements extend cleanly into the outer regions where traditional rotation-curve analyses become uncertain. The resulting extinction map offers insight into the structure of the interstellar medium, the radial mass profile, and potentially the physical processes that shape and maintain the spiral arms of LEDA 2073461.

3. The Foreground Galaxy LEDA 2073461

This galaxy shows a well-constructed grand design spiral pattern [

9,

10] and can be perfectly simulated by the galactic spiral equation from ROTASE model [

11] as shown in

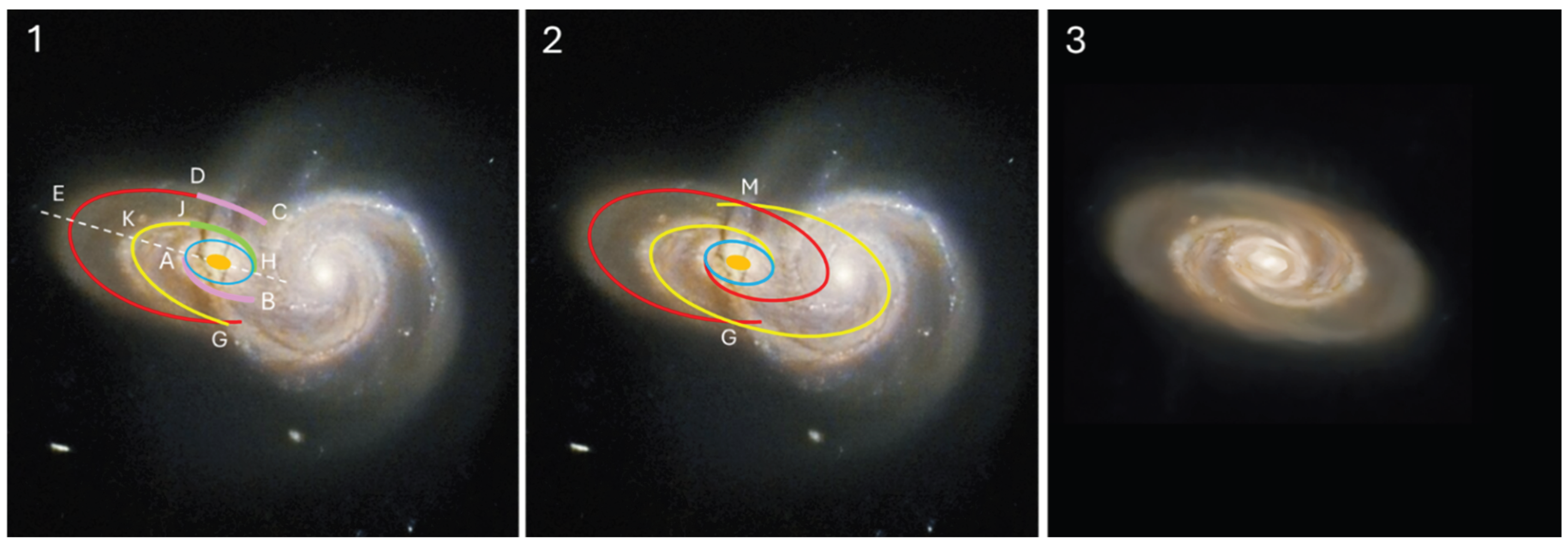

Figure 1B. The parameter ρ follows the equation:

However, the galaxy shows two very interesting phenomena illuminated by the “light box” from behind background galaxy SDSS J115331.86, shown in

Figure 2.

Figure 2A, when compared with the original overlapping-galaxy image in

Figure 1A, reveals a striking pair of dark lanes (marked by the blue and red lines) that flank both sides of a spiral arm in the foreground galaxy LEDA 2073461. These features represent dust lanes illuminated from behind by the background galaxy SDSS J115331.86. Notably, the inner dust lane (red) continues inward along the spiral arm toward the central region, as indicated by the green marking. The spiral arm itself narrows progressively and forms a distinct bottleneck at the lower end of the paired dust lanes.

LEDA 2073461 is a nearly textbook example of a grand-design spiral galaxy, the type most often cited in support of Density Wave Theory (DWT) [

12]. According to DWT, dust lanes arise where interstellar material encounters the spiral density wave and is compressed. For material entering the arm from inside the corotation radius, the dust lane should appear along the inner edge of the spiral arm. Conversely, for material approaching from the leading side of the arm, the dust lane should lie along the outer edge. In either case, DWT predicts a single dust lane on one side of the arm, determined by the direction of gas inflow relative to the density wave.

However, the observations here show dust lanes on both sides of the same spiral arm—an arrangement that is inconsistent with the predictions of Density Wave Theory. Furthermore, the dust feature highlighted by the green line lies within the middle of the spiral arm, rather than along either the inner or outer edge, which further contradicts the expected morphology of dust lanes in a density-wave-driven spiral.

If a corotation circle exists in LEDA 2073461, Density Wave Theory also predicts a dip in arm luminosity near the corotation radius due to the suppression of new star formation [

13]. One might interpret the bottleneck region as such a luminosity dip. However, if this interpretation were correct, the opposite spiral arm—labeled C and located at a comparable galactocentric distance—should exhibit a similar bottleneck or luminosity depression. No such feature is observed, further challenging the applicability of the Density Wave Theory to this system.

Chugunov et al. studied NGC 4535 and identified two pairs of luminosity dips along its spiral arms [

14]. Although each pair occurs at approximately the same galactocentric radius, none of the dips coincide with the expected location of the corotation circle. A plausible explanation is that these features arise from an inhomogeneous distribution of galactic material within the disk. An instructive analogy is provided by the ring system of Saturn, shown in

Figure 3. As of today, seven major rings have been identified, and their material distribution is highly non-uniform: the rings are separated by pronounced gaps such as the Cassini Division and Encke Division shown in the

Figure 3, and even within a single ring the density and chemical composition vary significantly with radius.

By extension, it is entirely reasonable to expect that the distribution of interstellar material in a spiral galaxy may also be substantially inhomogeneous as the size of galaxy is much larger than the Saturn. Radial gaps may exist within the disk, and even along a single radius the local density and chemical composition can vary markedly. Under this interpretation, the luminosity dips observed in NGC 4535 could naturally arise from such “gaps,” where the local supply of galactic material is insufficient to sustain enough new star formation. The bottleneck of spiral arm of the galaxy LEDA 2073461 could be also caused by the inhomogeneity of interstellar material distribution.

Figure 2B highlights the obscuring effect of the foreground galaxy LEDA 2073461 on the background galaxy SDSS J115331.86. The green circle marks the assumed outer boundary of LEDA 2073461. The region outlined by the orange lines corresponds to a non-spiral-arm portion of the foreground disk that lies directly in front of the background galaxy. Strikingly, this region appears essentially transparent: the background galaxy is clearly visible with minimal attenuation. Such transparency indicates that the density of interstellar material in this part of the disk is very low. The inner region outlined by the purple lines is slightly less transparent with expected higher disk density of the foreground galaxy as closer to the galactic center, but the texture of background galaxy is still visible, again revealing the background galaxy with little obscuration and implying a low material density in this portion of the foreground disk.

Taken together, these observations suggest that the interstellar medium between the spiral arms of LEDA 2073461 is sparse and insufficient to support the continuous inflow and compression of material required by Density Wave Theory. In the density-wave framework, substantial amounts of gas must flow in and out of the spiral arms to sustain the wave pattern and trigger ongoing star formation. One could argue that the material density in the orange- and purple-outlined regions is high but unusually transparent to background light; however, such a scenario is highly unlikely. Instead, the evidence favors a central-emission-driven mechanism for spiral arm formation, such as that described by the ROTASE model [

11].

The empty or low-density interstellar material distribution between spiral arms in the galaxy LEDA 2073461 is not a rare phenomenon, can be found in other galaxies also. A similar conclusion arises from Hoag’s Object, shown in

Figure 4A. The most striking feature in this image is the presence of a second, more distant Hoag-like ring galaxy located near the one-o’clock position with enlarged inset. This background object is seen with almost no obscuration from the foreground Hoag’s Object, indicating that the interior between the ring and central core is essentially empty. Such an “empty space” is difficult to reconcile with Density Wave Theory, which requires substantial material throughout the disk to sustain wave propagation. The ROTASE model provides a more plausible explanation for the formation of Hoag’s Object [

11].

Figures 4B and 4C present the well-known Tadpole Galaxy, characterized by its peculiar head–tail morphology. In this system, two much smaller objects (labeled 1 and 2) appear to be external intruders merging with the Tadpole Galaxy. The most remarkable feature, however, is the presence of two well-defined spiral arms in the head region, traced by the yellow and red lines, those spiral arms look normal compared to other regular spiral arms of disc galaxies. Previous analysis by the author [

15] shows that these two spiral arms do not lie in the same plane: the yellow arm spirals upward with left-hand chirality, while the red arm spirals downward, also with left-hand chirality. This makes the Tadpole Galaxy the only known chiral galaxy to date. The interaction with the two intruders induces a wobbling rotation in the Tadpole Galaxy, producing off-plane, three-dimensional cone-like spiral structures. Importantly, there is no detectable galactic material between the yellow and red spiral arms.

Such off-plane, non-coplanar spiral arms cannot be produced by Density Wave Theory, which requires a coherent, planar disk for wave propagation. Instead, the morphology of the Tadpole Galaxy is more naturally explained by a central-emission mechanism such as the ROTASE model, which can account for the observed three-dimensional spiral geometry.

4. Background Galaxy SDSS J115331.86

The

Figure 1C shows the depiction of the spiral pattern of the background galaxy SDSS J115331.86. Its left half side is clearly visible and other half is partially obscured by the central regions of the foreground galaxy. However, we may still make best approximate guess for the morphology of the galaxy based on the information from the left visible half side.

Figure 5-1 reveals visible segments of two spiral arms of the background galaxy SDSS J115331.86. The first spiral arm begins at the thick pink segment A–B. The segment B–C is fully obscured by the foreground galaxy, while the thick pink segment C–D is only partially obscured yet remains clearly identifiable. From D to G, the spiral continues curved loop with a steadily decreasing luminosity along the arm.

The second spiral arm originates at the thick green segment H–J, which is also partially obscured but still recognizable. This arm extends from J to K and then to G, again showing a gradual decline in luminosity along its length. At point G, the second (yellow) spiral crosses over the first (red) spiral. At this crossing, the luminosity of the second spiral is significantly stronger than that of the first. This crossing behavior matches the defining characteristics of the “chain-link” spiral-arm crossing pattern first introduced by the author [

11].

The central inner ring, outlined by the blue oval, is clearly visible. However, the orientation of the galactic bar cannot be determined from the image due to obscuration. Using the visible arm segments, curvature extension trend, the luminosity gradient patterns, and the assumption of central symmetry, the overall spiral configuration of the background galaxy can be reconstructed as shown in

Figure 5-2. The system is best interpreted as an 8-shaped double-ring galaxy exhibiting a chain-link spiral-arm crossing pattern, with points G and M marking the two arm-crossing locations.

Figure 5-3 presents the reconstructed appearance of SDSS J115331.86 after removing the obscuration from the foreground galaxy.

5. Conclusion

The overlapping spiral galaxies LEDA 2073461 and SDSS J115331.86 offer a rare opportunity to investigate both the structural properties and the formation mechanisms of spiral arms. The foreground system, LEDA 2073461, is an exemplary grand-design spiral galaxy. Its inter-arm regions contain only very low-density interstellar material, producing an almost transparent obscuration of the background galaxy. Such a low gas and dust density is difficult to reconcile with the predictions of classical Density Wave Theory for spiral-arm formation, whereas a central-driven emission mechanism appears more consistent with the observations.

The background galaxy, SDSS J115331.86, is most plausibly interpreted as an 8-shaped double-ring system exhibiting a chain-link spiral arm crossing pattern. This morphology provides additional insight into non-classical spiral structures and highlights the value of this overlapping pair as a natural laboratory for studying spiral-arm dynamics.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ostriker, J. P.; Peebles, P. J. E.; Yahil, A. The size and mass of galaxies, and the density of the universe. ApJ 1974, 193, L1–L4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofue, Y.; Rubin, V. Rotation curves of spiral galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2001, 39, 137–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. E.; Keel, W. C. Direct measurement of the optical thickness of spiral galaxy disks. Nature 1992, 359(6391), 129–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keel, W. C.; et al. Galaxy Zoo: A Catalog of Overlapping Galaxy Pairs for Dust Studies. The Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 2013, 125(923), 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holwerda, B.W.; et al. An extended dust disk in a spiral galaxy: an occulting galaxy pair in the ACS nearby galaxy survey treasury. AJ 2009, 137, 3000–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keel, W. C.; et al. Gems of the Galaxy Zoos—A Wide-ranging Hubble Space Telescope Gap-filler Program. AJ 2022, 163(4), 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmberg, E. A photographic photometry of extragalactic nebulae. Lund Medd. Astron. Obs. Ser. II 1958, 136, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T. Interstellar Dust Grains. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2003, 41(1), 241–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buta, R. J. Galaxy Morphology, in Planets, Stars and Stellar Systems; Springer, 2013; Vol. 6, pp. pp 1–89. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs, C.; Baba, J. 2014, Dawes Review 4: Spiral Structures in Disc Galaxies. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia 31, e035. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Hongjun. Spirals and Rings in Barred Galaxies by the ROTASE Model. IJP 2021, 9(6), 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. C.; Shu, F. H. On the Spiral Structure of Disk Galaxies. ApJ 1964, 140, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Hongjun. Density Wave Theory with Co-rotation May Have a Critical Problem. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugunov, I.; Marchuk, A.; Savchenko, S. Examination of the Functional Form of the Light and Mass Distribution in Spiral Arms. Galaxies 2025, 13(2), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Hongjun. Tadpole galaxy pattern may be formed by the combination of the ROTASE mechanism and galactic merging. IAARJ 2022, 4(1), 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Buta, R. Resonance Rings and Galaxy morphology. Astrophys. Space Sci. 1999, 269–270, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).