1. Introduction

Excess low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is considered a key risk factor in the development of atherosclerosis responsible for cardiovascular (CV) diseases (CVD), and its reduction has been a therapeutic priority for decades. In this context, the 3-hydroxy-3-methyglutaryl coenzyme-A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors are a class of drugs, also known as “statins”, that have revolutionized cardiovascular prevention, demonstrating significant reductions in morbidity and mortality from coronary and cerebrovascular events which are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality globally, substantially contributing to the socioeconomic burden of healthcare systems [

1].

Beyond lipid lowering, several clinical and mechanistic studies have described so-called pleiotropic effects of statins — including improvements in endothelial function, anti-inflammatory actions, atherosclerotic plaque stabilization and antithrombotic effects — which may contribute to early and some LDL-independent benefits observed in specific settings [

2,

3]. Nevertheless, evidence from randomized trial indicates that the magnitude of LDL-C reduction remains the primary determinant of clinical benefit, while the incremental clinical importance of pleiotropic mechanisms continues to be actively investigated [

2,

4].

Indeed, meta-analyses of statin trials have demonstrated that each 1 mmol/L reduction in LDL-C corresponds to an approximate 23% reduction in major vascular events [

5]. For this reason, clinical guidelines worldwide strongly recommend statin for patients at CV risk, and their chronic use has become standard practice in both primary and secondary prevention strategies [

6,

7].

Notably, several studies indicate that in primary prevention among low– to moderate-risk individuals, who account for approximately 60–70% of patients, statin therapies do not confer a direct measurable clinical benefit [

8]. In secondary or high-risk prevention 20–30% of patients fail to achieve a clinically meaningful reduction in CV events despite adequate LDL-C reduction [

9]. This suggest that CV risk is governed by a complex interplay of factors—including chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and remnant cholesterol—some of which remain underestimated or insufficiently addressed in clinical practice. Nevertheless, despite the established therapeutic value of statins, many patients are forced to discontinue or down-titrate therapy, particularly because of muscular, hepatic, or metabolic adverse effects [

10,

11].

Clinical data indicate that 20–25% of patients discontinue statins within 1–2 years, and that 5–10% experience true intolerance [

12]. More recently, it was estimated that over 50% of patients discontinue therapy within two years of initiation [

13]. Importantly, statin-treated patients who discontinued therapy because of intolerable adverse effects did not show a significant increase in mortality due to CVD [

4]. Suboptimal adherence to statin therapy therefore remains a major clinical challenge, as it represents a missed opportunity to reduce the burden of CVD [

14]. Consequently, the risk/benefit balance of statin use in primary prevention remains a complex and evolving topic of debate [

15].

Within this context, nutritional status has emerged as a critical factor that may influence the pleiotropic effects of statins, thereby linking pharmacological mechanisms with diet-related and malnutrition-associated clinical outcomes.

Malnutrition is an increasingly prevalent clinical condition among patients with chronic diseases, particularly in CV and geriatric–metabolic settings characterized by inflammation and complex metabolic disturbances. In these populations, the prevalence of malnutrition ranges from 30% to 60% [

16]. Recently, growing attention has been directed towards the interplay between nutritional status and statin therapy. Malnutrition and sarcopenia may alter drug metabolism, thereby affecting both the efficacy and tolerability of statins [

17,

18]. Moreover, chronic statin use, through marked reductions in total and LDL-C levels, may interfere with nutrition-related indices that include lipid parameters, such as the CONUT score, potentially leading to an overestimation of malnutrition [

19,

20]. In frail or elderly individuals, low LDL-C levels may not necessarily reflect CV protection but rather indicate nutritional decline or chronic inflammation [

21,

22]. Taken together, these observations highlight the need for a deeper understanding of the bidirectional relationship between malnutrition and statin therapy, with particular attention to underlying pathophysiological mechanisms, clinical implications, and the interpretative limitations of current diagnostic tools.

This narrative review aims to summarize the available evidence and to highlight how an integrated and personalized approach — incorporating nutritional assessment — may optimize clinical outcomes and therapeutic management in patients receiving statin therapy, beyond standardized cholesterol-lowering strategies. To enhance transparency in all aspects of this narrative and qualitative research, we followed the recommendations of the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) [

23].

2. Statins: Mechanism of Action and Pharmacokinetic Aspects

The mechanism of action of statins and their pharmacokinetics has been extensively described in the literature. Therefore, this section provides a concise overview of the key aspects relevant to the present discussion.

Statins are approximately 90% bound to serum proteins, mainly albumin, except for pravastatin, which exhibits a protein-binding rate of about 50% [

24]. Hepatic uptake of statins is mediated by active transporters, particularly organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1; SLCO1B1 gene). Genetic variants (e.g., SLCO1B1 c.521T>C) or inhibitors of OATP1B1 can increase plasma and skeletal muscle exposure to certain statins, thereby increasing the risk of muscle toxicity [

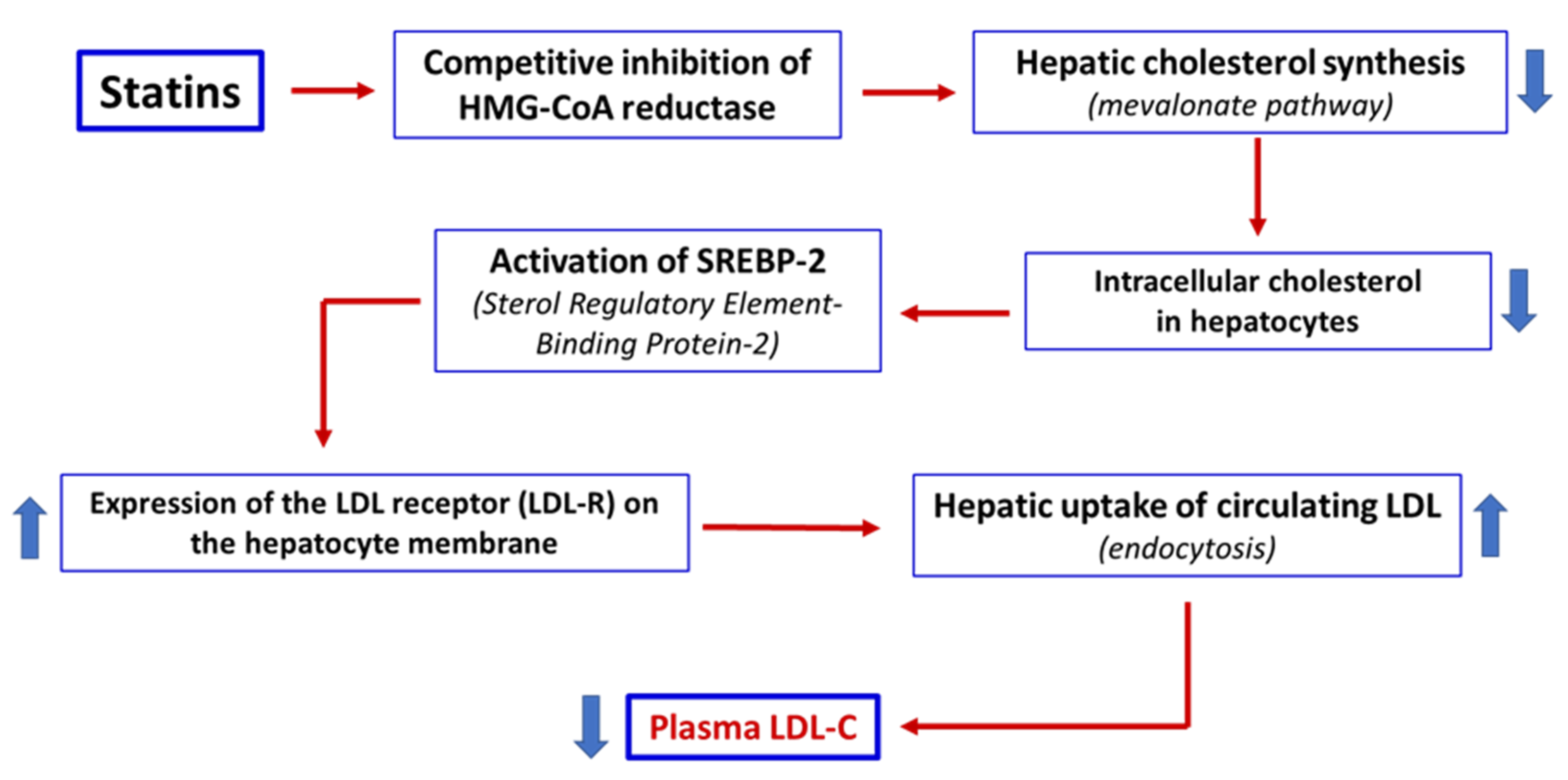

25]. In the liver, statins act as competitive inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase, blocking the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate. This inhibition reduces endogenous hepatic cholesterol synthesis, upregulates the expression of LDL receptors on the hepatocytes surface, and consequently enhances the clearance of circulating LDL-C levels, leading to a reduction in plasma LDL-C levels [

3] (

Figure 1).

In addition to their lipid-lowering effects, statins exert a range of pleiotropic actions mediated by reduced synthesis of intermediates of the mevalonate pathway, including isoprenoids such as farnesyl pyrophosphate and geranyl-geranyl pyrophosphate. These intermediates regulate the activity of prenylated proteins (e.g., Rho and Ras), thereby influencing key biological processes such as inflammation, endothelial function, plaque stability, and coagulation. These mechanisms are particularly relevant when considering the CV benefits of statins that are independent of LDL-C reduction [

3].

Statins are commonly classified as lipophilic or hydrophilic. Lipophilic statins (atorvastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin, fluvastatin, pitavastatin) more readily penetrate extrahepatic tissues and are metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes, particularly CYP3A4 and CYP2C9. In contrast, hydrophilic statins (rosuvastatin, pravastatin) are more hepato-selective and exhibit limited distribution in peripheral tissues. These differences influence pleiotropic effects, safety profile - particularly the risk of myopathy) - and susceptibility to drug–drug interactions [

26]. Some statins (simvastatin, lovastatin) are administered as inactive lactone prodrugs and are converted by hepatic enzymes to the active β-hydroxy acid form, whereas others (pravastatin, rosuvastatin, atorvastatin) are administered directly in their active form. This distinction has implications for pharmacokinetics and potential drug interactions [

3].

Although most statins are well absorbed following oral administration, their systemic bioavailability is limited by extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism. Therefore, for example, the bioavailability of atorvastatin is approximately 12%. In general, the oral bioavailability of statins ranges from 5 to 30%. The plasma half-life varies widely among the different molecules: from approximately 1–3 hours for simvastatin and lovastatin, up to over 19 hours for rosuvastatin and atorvastatin. This variability influences the dosage and therapeutic efficacy at the same dose [

26].

Several statins (atorvastatin, simvastatin, and lovastatin) are primarily metabolized in the liver via the cytochrome CYP3A4 enzyme system and subsequently undergo conjugation with glucuronic acid by uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) enzymes. These statins are predominantly eliminated via biliary excretion. In contrast, hydrophilic statins such as pravastatin are less dependent on hepatic metabolism and are extensively eliminated through the kidneys.

3. Disadvantages of Chronic Statin Therapy

Although statins represent a well-established therapeutic strategy capable of reducing CV morbidity and mortality through synergistic mechanisms that extend beyond simple plasma LDL-C lowering, long-term adherence remains problematic [

13]. This issue is largely driven by perceived or actual adverse effects, which most commonly involve skeletal muscle [

27,

28,

29].

Studies suggest that statins may significantly affect mitochondrial function and that some adverse effects might be mediated through mitochondrial dysfunction and intracellular surviving pathways [

30]. For example, cardiomyocytes obtained from patients with metabolic syndrome (MetS) treated with simvastatin were found to be more susceptible to stress both before and after ischemia-reperfusion during cardio-pulmonary bypass that cardiomyocytes from MetS patients not receiving statins. Specifically, cardiomyocytes from MetS+Stat patients exhibited reduced expression of the mitochondrial chaperone GRP75, together with increased expression of the endoplasmic reticulum stress marker GRP78 and the pro-apoptotic protein Bax [

31]. In addition, statin therapy has been associated with a reduction in the omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acid ratio, as well as with increases in body mass index, insulin resistance, and the risk of diabetes. Moreover, statins have been linked to reduced antitumor immune surveillance and a potential increase in breast cancer risk [

32].

The clinical effectiveness of statins may be further compromised by statin-associated muscle symptoms (SAMS), which represent the most frequently reported adverse effect in routine practice [

28,

29,

33]. SAMS encompass a broad spectrum of manifestations, ranging from myalgia and muscle weakness to elevations in creatine kinase (CK) levels [

34]. Statin-induced myotoxicity includes a self-limiting toxic myopathy that resolves after statin discontinuation, as well as a rare immune-mediated condition—immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM)—which requires immunomodulatory treatment [

35].

The pathophysiology of SAMS is multifactorial and remains incompletely understood. Several mechanisms have been proposed, including mitochondrial dysfunction [

36,

37], disruption of intracellular signaling pathways [

38], vitamin D deficiency [

39], inhibition of the mevalonate pathway [

40], genetic susceptibility [

41], and underlying neuromuscular disorder [

42].

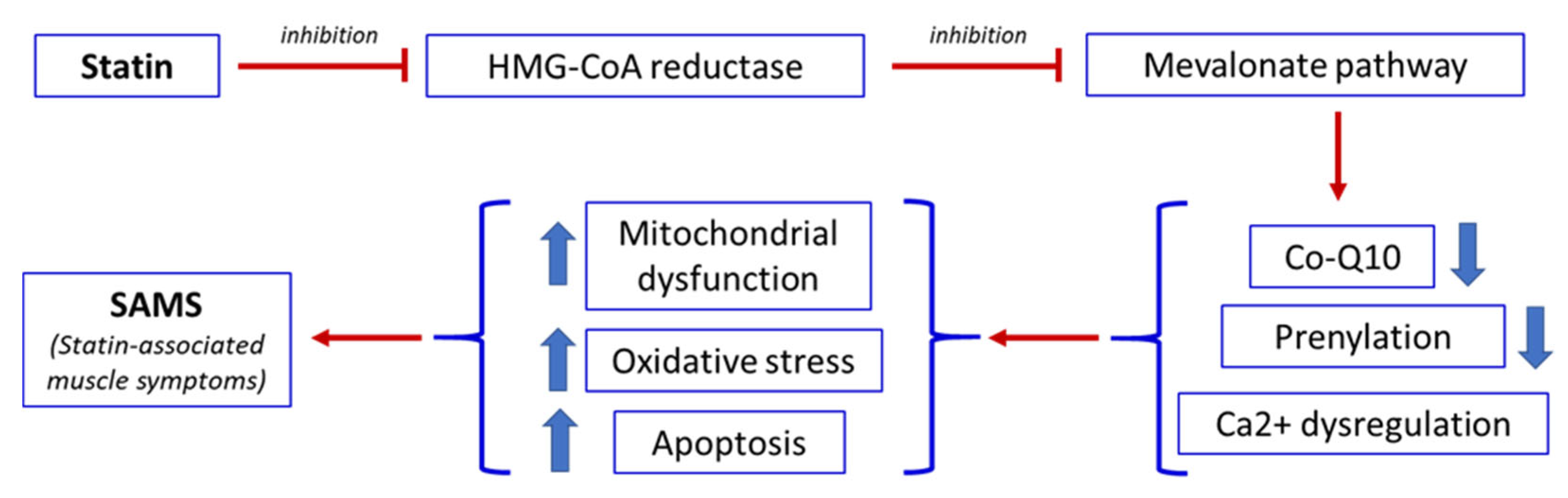

A central mechanism underlying statin-induced muscle toxicity is the inhibition of the mevalonate pathway. In addition to reducing cholesterol synthesis, this pathway also limits the production of isoprenoid intermediates such as coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10, also known as ubiquinone), farnesyl pyrophosphate, and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate [

30]. These compounds are essential for mitochondrial function, protein prenylation, and cellular energy metabolism. Reduced CoQ10 availability impairs the mitochondrial respiratory chain, leading to decreased adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production and increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The resulting oxidative stress promotes mitochondrial DNA damage and activation of apoptotic pathways, ultimately contributing to muscle fiber injury [

30,

43].

Statins may also disrupt intracellular calcium homeostasis in skeletal muscle, contributing to symptoms such as cramps and spasms [

44,

45]. Furthermore, they can alter the expression of genes involved in muscle protein degradation and mitochondrial biogenesis, thereby promoting muscle atrophy and impairing regenerative capacity [

44]. Finally, statins may additionally increase mitochondrial membrane permeability, facilitating the release of pro-apoptotic enzymes and further disturbing calcium handling [

44]. In most cases, SAMS are mild and reversible. However, a small subset of patients may develop severe complications, including rhabdomyolysis [

46] and necrotizing autoimmune myopathy (NAM), which is characterized by muscle weakness, markedly elevated creatine kinase (CK) levels, and the presence of anti-HMG-CoA reductase antibodies [

11].

Figure 2 summarizes the sequence of events that, following statin administration, leads to the development of SAMS.

4. Limitations of Guidelines and Clinical Trials

International guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia play a central role in defining diagnostic criteria, therapeutic targets, and indications for statin prescription [

47,

48,

49]. These guidelines are primarily based on evidence derived from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) and their systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which are widely regarded as the gold standard for evaluating interventions aimed at reducing cardiovascular risk through LDL-C lowering.

However, although RCTs represent the most rigorous method for evaluating the effectiveness and safety of healthcare interventions, their results must be interpreted considering important methodological, operational, and ethical limitations. Consequently, RCTs may fail to adequately reflect the heterogeneity of real-world patient populations, a limitation that has been increasingly recognized and addressed by regulatory authorities such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [

50,

51].

To ensure internal validity, many RCTs adopt restrictive eligibility criteria that exclude specific patient groups, such as individuals with multimorbidity, advanced age, polypharmacy, or socioeconomic vulnerability [

51,

52]. These exclusions limit external validity and reduce the generalizability of trial findings to everyday clinical settings. Consequently, therapeutic strategies that demonstrate robust efficacy in selected trial populations may yield attenuated benefits in broader, unselected patient cohorts [

51]. In addition, the under-representation of vulnerable populations limits meaningful subgroup analyses and hinders the extrapolation of results across diverse demographic and clinical contexts [

53]. Another relevant limitation is that many RCTs prioritize short-term endpoints to reduce costs and accelerate trial completion, often resulting in insufficient follow-up to capture long-term benefits, delayed adverse effects, or disease progression [

50]. This issue is particularly problematic for preventive therapies and chronic conditions, where clinically meaningful outcomes may emerge only over extended periods. Furthermore, publication and reporting biases must be considered, as trials with positive findings are more likely to be published and disseminated than those reporting neutral or unfavorable results [

54,

55].

Taken together, these considerations underscore the importance of interpreting clinical practice guidelines not as rigid prescribing algorithms but as flexible, evidence-informed frameworks that support personalized clinical decision-making. Such an approach is essential given inter-individual variability in statin response, the presence of comorbidities, patient preferences, and the complex interaction between pharmacological therapy and dietary habits.

Current guidelines appropriately emphasize the role of lifestyle modification, recognizing nutritional intervention as a fundamental component of dyslipidemia management, both as a first-line strategy and as an adjunct to pharmacological treatment [

56,

57]. For example, Mediterranean-style dietary patterns, characterized by a high intake of favorable nutrients — such as soluble fiber, mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids, phytosterols, and antioxidants — have been shown to improve lipid profiles and enhance the lipid-lowering efficacy of statins [

2,

58]. Conversely, dietary patterns rich in saturated fats, refined sugars, and alcohol may attenuate therapeutic response and contribute to residual cardiovascular risk.

A further illustration of the need for context-sensitive application of guidelines concerns younger populations. Among children and adolescents, excess body weight resulting from poor dietary habits, high consumption of ultra-processed foods, and sedentary lifestyles have reached alarming levels. This condition is associated with early clustering of cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, hyperuricemia, glucose intolerance, and type 2 diabetes. In this population, initial management should prioritize lifestyle and dietary modification rather than pharmacological intervention, except in carefully selected high-risk cases [

59].

From a clinical perspective, integrating statin therapy with structured nutritional counselling may optimize LDL-C reduction, improve treatment adherence by avoiding unnecessary dose escalation, and mitigate adverse effects — such as myalgia and liver enzyme abnormalities — that frequently lead to therapy discontinuation [

60]. This combined approach also facilitates the management of low-grade inflammation, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis, all of which interact with lipid metabolism and can influence responsiveness to statin therapy.

In summary, while clinical guidelines provide a robust methodological foundation for appropriate statin prescribing, they should not be applied uncritically. Their greatest clinical effectiveness is achieved when recommendations are tailored to the individual patient and when pharmacological treatment is integrated with dietary and lifestyle interventions.

5. Link Between Malnutrition and Statin Therapy

Recent evidence has highlighted that the use of statin monotherapy in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease among patients with metabolic syndrome is associated with suboptimal diet quality [

61]. The link between malnutrition, or states of nutritional depletion, and an increased risk of statin side effects is clinically relevant yet frequently under-recognized.

Malnourished patients represent a fragile biological milieu, in which the metabolic effects of statins, especially at the hepatic and muscular levels, may become less tolerable and potentially more harmful. Individuals with low body mass index (BMI) and/or protein–calorie malnutrition have reduced total muscle mass and, consequently, a smaller volume of drug distribution. In such patients, a standard statin dose that would be appropriate for an individual of normal body weight may be relatively excessive, thereby increasing the risk of toxic effects [

62]. Malnutrition, particularly when associated with advanced liver disease or chronic alcohol consumption, may also impair cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzyme activity, which is essential for the metabolism of most statins. This impairment can result in drug accumulation, thereby increasing the risk of hepatotoxicity [

63].

Furthermore, sarcopenia secondary to malnutrition leads to a reduced functional reserve of skeletal muscle and a diminished capacity to adapt to pharmacological stress [

64,

65]. Given that statins can induce mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress in muscle fibers, malnourished muscle tissue is inherently more vulnerable to pharmacological insults, including those associated with statin therapy [

66]. As previously discussed, statins inhibit the synthesis of mevalonate, a precursor not only of cholesterol but also of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), which is essential for mitochondrial ATP production and functions as a key antioxidant [

67]. Malnourished patients often exhibit reduced baseline CoQ10 levels; statin therapy may therefore exacerbate pre-existing mitochondrial energy deficits and oxidative stress, leading to muscle pain and weakness [

68].

Low serum vitamin D concentrations also represent a recognized risk factor for statin-induced myopathy. Vitamin D plays a critical role in skeletal muscle health by regulating mitochondrial function, muscle contractility, and protein synthesis. Malnutrition, particularly when combined with limited sunlight exposure—a common condition in elderly and chronically ill individuals—amplifies vitamin D deficiency, thereby predisposing muscle tissue to statin-related damage [

69,

70]. However, it should be noted that a recent randomized clinical trial demonstrated that vitamin D supplementation did not prevent SAMS nor reduce statin discontinuation rates [

71].

6. Nutrition and Statin Therapy

Clinical evidence supporting the use of nutraceuticals to improve lipid levels is highly variable and, for many compounds, still very limited. Data on the use of nutraceuticals in patients with SAMS or statins intolerance are even more scarce [

72]. For most nutraceutical, recommendation can be made only based on their demonstrated efficacy in lowering LDL-C and available safety data. Therefore, there is an urgent need for additional evidence on the potential role of nutraceuticals in patients experiencing statin-associated adverse effects.

Unfortunately, nearly 50% of individuals initiating statin therapy do not achieve the targeted reduction in plasma LDL-C and thus remain exposed to a substantial residual risk of CVD [

73]. Consequently, additional strategies may be useful to improve the efficacy of statin treatment and to limit potential adverse effects.

Statin therapy reduces plasma LDL-C and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels, resulting in a significant improvement in CV risk. It has therefore been suggested that reducing chronic inflammation through cholesterol lowering may attenuate vascular damage and ultimately improve CV outcomes [

72]. In this context, adequate nutrition represents an essential component of statin therapy.

It has been suggested that a "healthy diet" suitable for CVD may increase the effectiveness of statins by reducing inflammation [

74]. Although the concept of a healthy diet remains broad and ambiguous, a Mediterranean-style dietary pattern—characterized by a high intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, olive oil, and unsaturated fats, together with a reduced intake of saturated fats and simple sugars—appears to act synergistically with statins in reducing CV risk. Indeed, adherence to a Mediterranean diet has been shown to reduce all-cause, coronary artery disease (CAD), and cerebrovascular mortality in patients with CVD, independently of statin use. In the same population, statins reduce CV mortality only when combined with a Mediterranean dietary pattern. These findings suggest that the control of low-grade inflammation, rather than lipid lowering alone, may be a key determinant of mortality reduction in these patients [

74].

An important nutraceutical for cholesterol control is red yeast rice (RYR) which contains monacolin K

, a compound structurally like lovastatin. Although effective in improving blood lipid profiles, in Europe RYR is considered a drug: therefore, when prescribed as a supplement, the monacolin K content should not exceed 3 mg/day [

75,

76]. Furthermore, RYR has not been adequately studied in the pediatric population, so young subjects treated with RYR should therefore be carefully monitored [

59].

Omega-3 fatty acids may also enhance the benefits of statin therapy. It has been demonstrated that omega-3 combined with statins is superior to the statin alone in stabilizing coronary plaques and promoting plaque regression and may further reduce the occurrence of CV events [

77]. However, a meta-analysis suggested that pravastatin and atorvastatin may be more effective than omega-3 supplementation in reducing the risk of total CVD, CAD, and myocardial infarction [

78]. Furthermore, in high-risk CV patients receiving statins, the addition of omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid), compared with corn oil and usual care, did not result in significant differences in major adverse CV events. These findings do not support routine omega-3 supplementation for the reduction of major adverse events in high-risk statin-treated patients [

79].

Although the anti-inflammatory and cardioprotective properties of omega-3 fatty acids are well recognized, substantial uncertainty remains regarding their effectiveness in preventing or alleviating SAMS. To date, there is no consolidated clinical evidence demonstrating that omega-3 prevent or significantly reduce SAMS. Specifically, there is a lack of randomized clinical trials with myopathy or SAMS specific endpoints evaluating whether omega-3 supplementation reduces the incidence, severity, or duration of muscle symptoms in patients who develop statin-induced SAMS. Conversely, some preclinical findings appear promising. A transcriptional and proteomic study conducted in primary human muscle cell lines exposed to a lipophilic statin (simvastatin) and a hydrophilic statin (rosuvastatin) identified more the 1,800 transcripts and 900 proteins were differentially expressed after statin exposure. Both statins significantly impacted cholesterol biosynthesis, fatty acid metabolism, eicosanoid synthesis, proliferation, and differentiation of muscle cells. Notably, eicosanoids restored biological function, suggesting that the addition of omega-3 fatty acids may be useful in preventing or treating SAMS [

80]. Nevertheless, reviews on statin-induced myopathy conclude that clinical evidence supporting specific nutritional interventions, including omega-3 fatty acids, remains limited [

81]. Similarly, a recent randomized controlled trial comparing oral coenzyme Q10 supplementation with placebo in patients with SAMS showed no significant benefit in improving myopathy [

82].

Plant stanol or sterol have also been shown to reduce excess LDL-C by inhibiting intestinal cholesterol absorption. Accordingly, it has been suggested that the intake of plant sterols in combination with statins may exert a synergistic effect in reducing total and LDL-C levels beyond that achieved with statin therapy alone [

83,

84]. However, the role of stanol or sterol in preventing atherosclerotic CVD remains incompletely established.

7. Potential Role of Essential Amino Acids (EAA) Supplementation in Prevention of Myopathy and SAMS

Statins disrupt the delicate balance of amino acids (AA) metabolism and related pathways, leading to energy deficits, oxidative stress, and protein damage in muscles, which manifest clinically as SAMS. In addition, statins affect protein degradation pathways (ubiquitin-proteasome system), altering the stability of muscle proteins, especially those with certain N-terminal amino acids such as lysine and arginine [

85,

86].

Essential amino acids (EAA), particularly branched chain (BCAA), play a key role in maintaining muscle mass, mitochondrial biogenesis and function, and in counteracting oxidative damage [

87]. Moreover, EAA supplementation has been shown to inhibit fat synthesis and accumulation [

88,

89] and to regulate numerous metabolic pathways through their action as metabokines [

90]. Accordingly, EAA supplementation may represent a valuable nutritional strategy to counteract both lipid accumulation and SAMS.

Early studies demonstrated that soy proteins can positively regulate LDL receptor expression, which is often downregulated by hypercholesterolemia or dietary cholesterol intake in humans [

91,

92]. However, the use of soy proteins may also present limitations. Chronic and high consumption of soy products has been reported to interfere with thyroid function and fertility, as well as to reduce the absorption of several minerals (including calcium, iron, magnesium, copper, and zinc) due to their high phytic acid content. Additional direct effects on the circulatory system have also been described [

93]. In a cross-sectional study evaluating the effects of a soy-based drink compared with cow’s milk in 21 hypercholesterolemic patients who were resistant or intolerant to statin therapy, the combination of soy and cow’s milk significantly reduce plasma total and LDL-C levels by approximately 7.5% [

94].

The hypothesis that creatine monohydrate supplementation could reduce muscle soreness and muscle damage following eccentric exercise in patients treated with high-dose atorvastatin has also been investigated. These studies showed no significant differences in muscle responses between creatine and placebo groups. Interestingly, a significant correlation was observed between low vitamin D levels and elevated CK concentrations after exercise, suggesting that vitamin D deficiency may exacerbate the effects of statins on skeletal muscle and potentially contribute to the development of SAMS [

95]. Two clinical studies have reported promising results for creatine supplementation in statin-induced myopathy [

96,

97]. More recently, a preliminary study indicated that low-dose creatine supplementation reduced subjective myopathy symptoms in patients with mild or early SAMS, without affecting serum CK levels [

98]. In addition, experimental studies and limited clinical evidence suggest that L-carnitine may improve some manifestations of statin-induced muscle toxicity; however, robust clinical data remain scarce [

81].

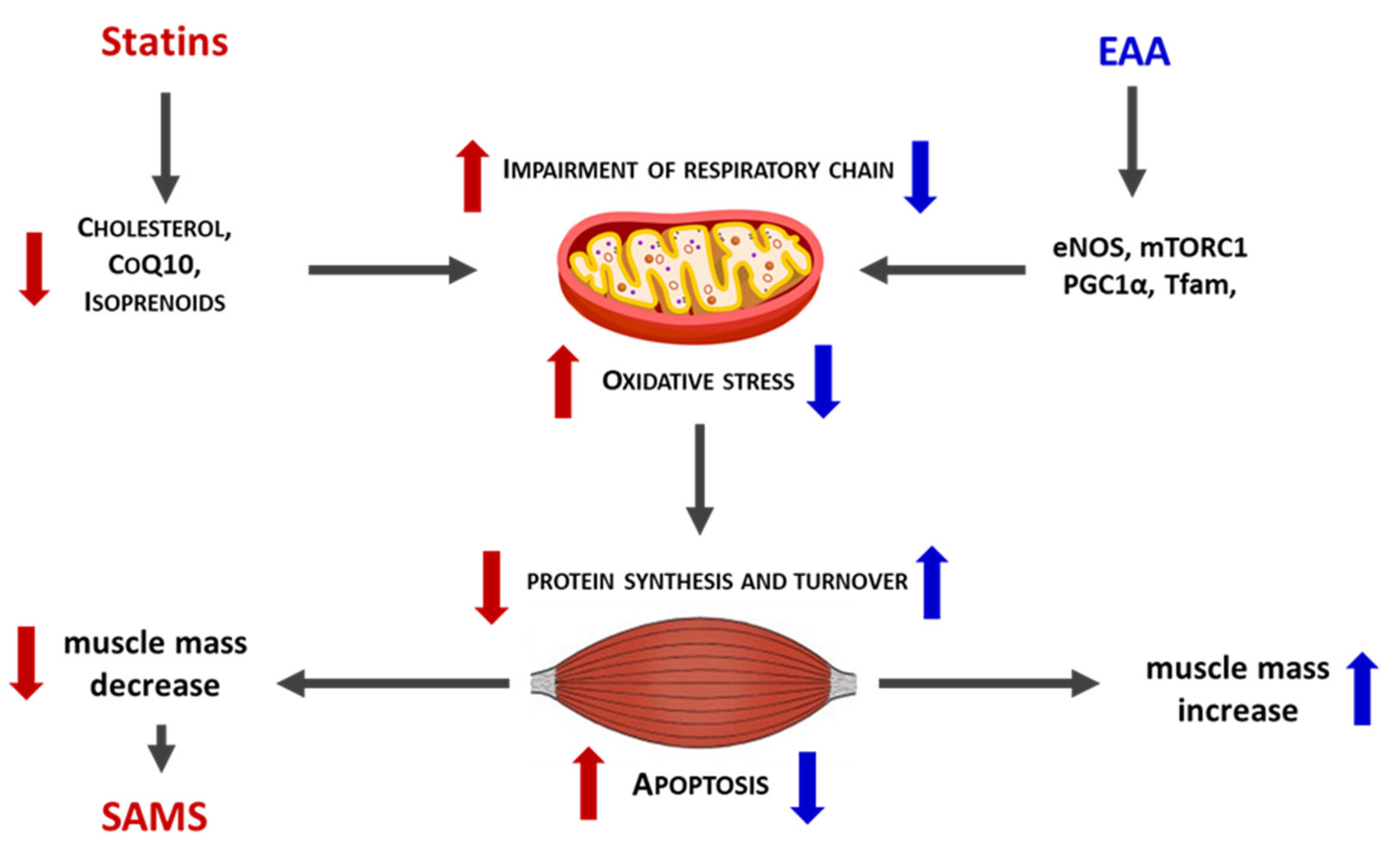

Extensive evidence supports the efficacy of dietary supplementation with a balanced EAA mixture in maintaining muscle mass and mitochondrial function across several clinical conditions characterized by impaired energy production [

99,

100,

101]. Numerous preclinical studies have further confirmed the protective effects of EAA mixtures in hypercatabolic and pathological states, ranging from ageing to cancer [

102,

103,

104]. Notably, in preclinical models, a specific balanced EAA mixture prevented rosuvastatin-induced muscle damage by stimulating de novo protein synthesis and reducing protein degradation. In addition, EAA supplementation preserved mitochondrial efficiency and improved oxidative stress control in muscle tissue from statin-treated mice [

105,

106] (

Figure 3).

Overall, supplementation with a personalized and balanced EAA mixture may represent a valuable supportive nutritional strategy to complement standard statin therapy, helping to preserve protein and mitochondrial homeostasis and thereby mitigate systemic adverse effects such as SAMS. Accordingly, well-designed clinical trials are warranted to confirm the efficacy of EAA supplementation, including in patients who are intolerant to statins.

8. Conclusions

Although statin therapy remains a valid and effective intervention for lowering LDL-C levels, caution is warranted in the indiscriminate application of clinical guidelines, as well as in the careful monitoring of potential adverse effects. Clinical practice guidelines represent evidence-based tools that support clinical decision-making but do not replace physician judgement. Accordingly, guidelines should be applied within an individualized, patient-centered therapeutic approach that accounts for patient-specific physiological variability and relevant clinical characteristics.

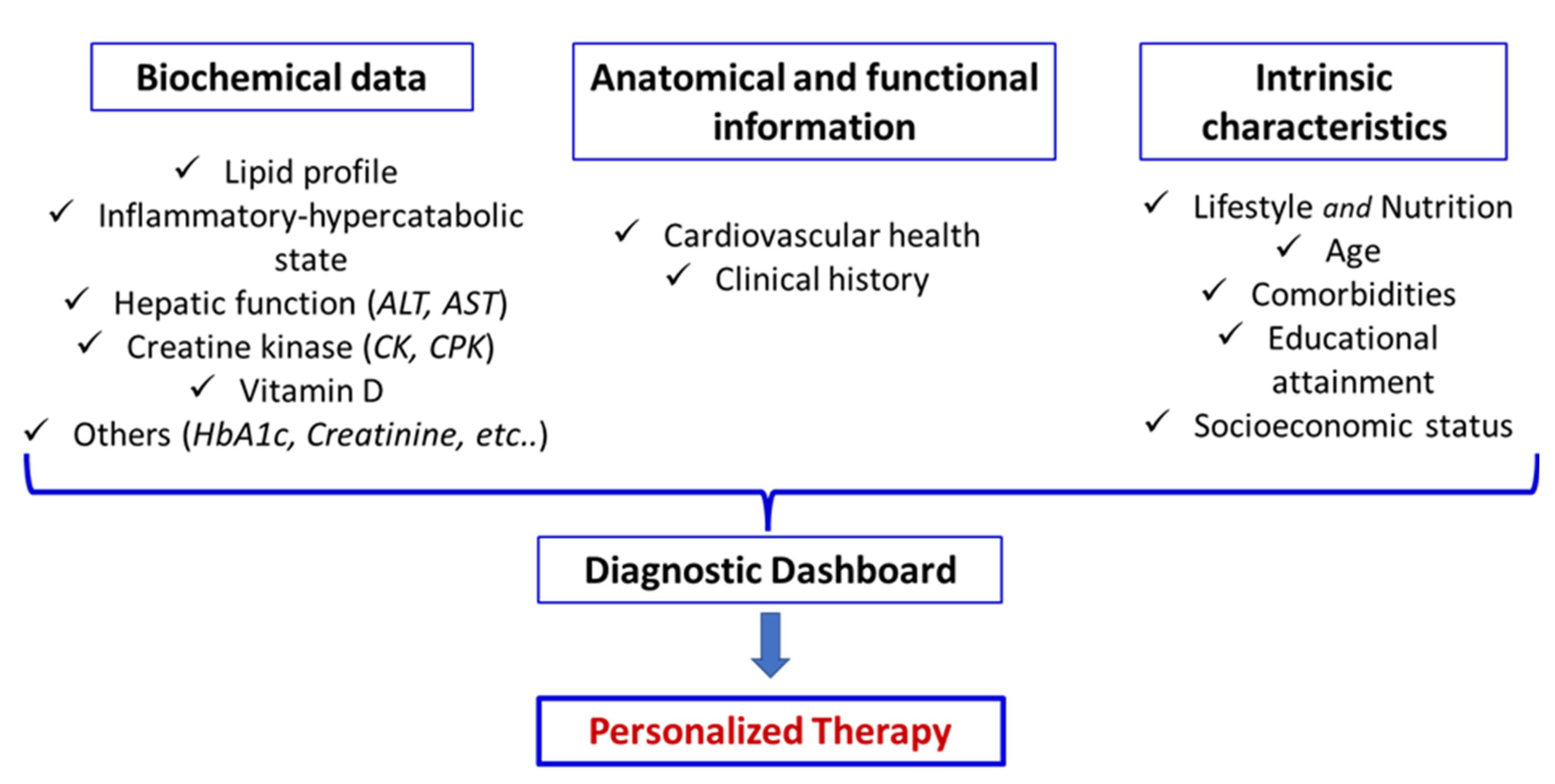

In this context, it is essential to integrate biochemical data of traditional lipid profile (Total cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, and triglycerides), emerging risk biomarker (e.g., omega-3 index, microRNAs levels, triglyceride-to-HDL-C ratio, lipid-lipoprotein ratio, others), markers of inflammatory and hypercatabolic state (e.g.; high-sensitivity-C-reactive protein, neutrophile to lymphocyte ratio, serum albumin, HOMA-index, others) and biological parameters of global patients metabolism (e.g., complete blood count, HbA1c, liver and kidney functions, creatine kinase, vitamin D, urine test, others) together with anatomical and functional assessments of the circulatory system as carotid ultrasound. These data should be further contextualized within the patient’s clinical history and intrinsic characteristics, including lifestyle, nutrition, age, comorbidities, educational level, and socioeconomic status, to construct a personalized diagnostic dashboard (

Figure 4).

Such a dashboard enables the development of tailored therapeutic strategies that, while adhering to established clinical guidelines as a fundamental reference, are specifically adapted to the unique characteristics of each patient. Attention should be devoted to nutritional factors, as adequate intake of the full spectrum of EAA may provide valuable support to pharmacological therapy by helping to mitigate statin-associated muscle and liver adverse effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C and E.P.; methodology, G.C and E.P.; software, G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C. and E.P.; writing—review and editing, G.C. and E.P.; supervision, G.C.; project administration, G.C.; funding acquisition, G.C. The authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work received a small contribution towards publishing costs from Vittorio Bellani.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cristina Antonelli for the linguistic revision of the text.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CVD |

Cardiovascular disease |

| CK |

Creatine kinase |

| CoQ10 |

Coenzyme Q10 |

| EAA |

Essential amino acids |

| HMG-CoA |

3-hydroxy-3-methyglutaryl coenzyme-A |

| LDL-C |

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| RCTs |

Randomized Clinical Trials |

| RYR |

Red yeast rice |

| SAMS |

Statin-associated muscle symptoms |

References

- Taylor, F.; Huffman, M.D.; Macedo, A.F.; Moore, T.H.; Burke, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Ward, K.; Ebrahim, S. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013, 2013(1), CD004816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridker, P.M.; Danielson, E.; Fonseca, F.A.; Genest, J.; Gotto, A.M., Jr.; Kastelein, J.J.; Koenig, W.; Libby, P.; Lorenzatti, A.J.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Shepherd, J.; Willerson, J.T.; Glynn, R.J.; JUPITER Study Group. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med 2008, 359(21), 2195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.K.; Sehgal, V.S.; Kashfi, K. Molecular targets of statins and their potential side effects: Not all the glitter is gold. Eur J Pharmacol 2022, 922, 174906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' Collaborators. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet 2012, 380, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, M.G.; Ference, B.A.; Im, K.; et al. Association between lowering LDL-C and cardiovascular risk reduction among different therapeutic interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.N.; Giugliano, R.P. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering therapy for the secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract 2020, 2020(3), e202039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, N.; Ruscica, M.; Fazio, S.; Corsini, A. Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol-Lowering Drugs: A Narrative Review. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, P.; Cullinan, J.; Smith, A.; Smith, S.M. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2019, 9(4), e023085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarese, E.P.; Robinson, J.G.; Kowalewski, M.; Kolodziejczak, M.; Andreotti, F.; Bliden, K.; Tantry, U.; Kubica, J.; Raggi, P.; Gurbel, P.A. Association Between Baseline LDL-C Level and Total and Cardiovascular Mortality After LDL-C Lowering: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2018, 319(15), 1566–1579, Erratum in: JAMA 2018 Oct 2, 320(13), 1387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12240.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bifulco, M. Debate on adverse effects of statins. Eur J Intern Med 2014, 25(8), e95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.D.; Panza, G.; Zaleski, A.; Taylor, B. Statin-Associated Side Effects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 67(20), 2395–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroes, E.S.; Thompson, P.D.; Corsini, A.; Vladutiu, G.D.; Raal, F.J.; Ray, K.K.; Roden, M.; Stein, E.; Tokgözoğlu, L.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; et al. European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy-European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel Statement on Assessment, Aetiology and Management. Eur Heart J 2015, 36(17), 1012–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banach, M.; Penson, P.E. Adherence to statin therapy: it seems we know everything, yet we do nothing. Eur Heart J Open 2022, 2(6), oeac071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de La Harpe, R.; Muzambi, R.; Bhaskaran, K.; Eastwood, S.; Herrett, E. Inequities in statin adherence for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a historical cohort study in English primary care. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2025, zwaf219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, M.; Patrono, C. The cardiovascular benefits of statins outweigh adverse effects in primary prevention: results of a large systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2021, 42(44), 4518–4519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kose, E.; Wakabayashi, H.; Yasuno, N. Polypharmacy and Malnutrition Management of Elderly Perioperative Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13(6), 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Huang, L.; Zhou, C.; Qian, B.; Luo, Z.; Chen, Y. Effects of statins on sarcopenia with focus on mechanistic insights and future perspectives. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1669591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semań, T.; Krupa-Nurcek, S.; Szczupak, M.; Kobak, J.; Widenka, K. Impact of Sarcopenia and Nutritional Status on Survival of Patients with Aortic Dissection: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Li, J.; Jin, H.; Chai, L.; Song, P.; Chen, L.; Yang, D. Predictive value of the controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score to assess long-term mortality (10 Years) in patients with hypertension. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2024, 34(11), 2528–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, S-P.; Guan, Y.; Yang, Q-Y.; Zhong, P-Y.; Wang, H-Y. Association between controlling nutritional status score and the prognosis of patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2025, 12, 1665713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioffe, M.; Kremer, A.; Nachimov, I.; Swartzon, M.; Justo, D. Mortality associated with stopping statins in the oldest-old - with and without ischemic heart disease. Medicine 2021, 100(37), e26966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, S.; Shishikura, D.; Kusumoto, H.; Yamauchi, Y.; Sakane, K.; Fujisaka, T.; Shibata, K.; Morita, H.; Kanzaki, Y.; Michikura; et al. Clinical impact of ≥50% reduction of low-density cholesterol following lipid lowering therapy on cardiovascular outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Clin Lipidol 2025, 19(2), 47–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, B.C.; Harris, I.B.; Beckman, T.J.; Reed, D.A.; Cook, D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014, 89, 1245–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.K. Calpain and caspase: can you tell the difference? Trends Neurosci 2000, 23(1), 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsby, R.; Hilgendorf, C.; Fenner, K. Understanding the Critical Disposition Pathways of Statins to Assess Drug–Drug Interaction Risk During Drug Development: It's Not Just About OATP1B1. Clin Pharm & Therap 2012, 92(5), 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climent, E.; Benaiges, D.; Pedro-Botet, J. Hydrophilic or Lipophilic Statins? Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 687585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.M.; Woodward, M.; Muntner, P.; Falzon, L.; Kronish, I. Predictors of nonadherence to statins: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother 2010, 44(9), 1410–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroes, E.S.; Thompson, P.D.; Corsini, A.; Vladutiu, G.D.; Raal, F.J.; Ray, K.K.; Roden, M.; Stein, E.; Tokgözoğlu, L.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; et al. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: impact on statin therapy—European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel Statement on Assessment, Aetiology and Management. Eur Heart J 2015, 36, 1012–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, P.; Panizon, E.; Tosoni, L.M.; et al. Statin-associated myopathy: emphasis on mechanisms and targeted therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22(21), 11687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollazadeh, H.; Tavana, E.; Fanni, G.; Bo, S.; Banach, M.; Pirro, M.; von Haehling, S.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of statins on mitochondrial pathways. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12(2), 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsetti, G.; Pasini, E.; Ferrari-Vivaldi, M.; Romano, C.; Bonomini, F.; Tasca, G.; Dioguardi, F.S.; Rezzani, R.; Assanelli, D. Metabolic syndrome and chronic simvastatin therapy enhanced human cardiomyocyte stress before and after ischemia-reperfusion in cardio-pulmonary bypass patients. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2012, 25(4), 1063–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lorgeril, M.; Salen, P. Do statins increase and Mediterranean diet decrease the risk of breast cancer? BMC Med 2014, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.D.; Panza, G.; Zaleski, A.; Taylor, B. Statin-associated side effects. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 67, 2395–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Shrestha, K.; Tseng, C.W.; Goyal, A.; Liewluck, T.; Gupta, L. Statin-associated muscle symptoms: A comprehensive exploration of epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and clinical management strategies. Int J Rheum Dis 2024, 27(9), e15337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfirevic, A.; Neely, D.; Armitage, J.; et al. Phenotype standardization for statin-induced myotoxicity. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2014, 96(4), 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schick, B.A.; Laaksonen, R.; Frohlich, J.J.; et al. Decreased skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA in patients treated with high-dose simvastatin. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007, 81(5), 650–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pinieux, G.; Chariot, P.; Ammi-Saïd, M.; et al. Lipid-lowering drugs and mitochondrial function: effects of HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors on serum ubiquinone and blood lactate/pyruvate ratio. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1996, 42(3), 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirvent, P.; Mercier, J.; Lacampagne, A. New insights into mechanisms of statin-associated myotoxicity. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2008, 8(3), 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Thompson, P.D. The relationship of vitamin D deficiency to statin myopathy. Atherosclerosis 2011, 215(1), 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalipati, N.; Shah, J.; Ramakrishan, A.; Vasnawala, H. Pleiotropic effects of statins. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2015, 19(5), 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunham, L.R.; Baker, S.; Mammen, A.; Mancini, G.B.J.; Rosenson, R.S. Role of genetics in the prediction of statin-associated muscle symptoms and optimization of statin use and adherence. Cardiovasc Res 2018, 114(8), 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsivgoulis, G.; Karandreas, N.; Panas, M.; Kladi, A.; Manta, P. Presymptomatic neuromuscular disorders disclosed following statin treatment. Arch Intern Med 2006, 166(14), 1519–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deichmann, R.; Lavie, C.; Andrews, S. Coenzyme q10 and statin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Ochsner J 2010, 10(1), 16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hanai, J.; Cao, P.; Tanksale, P.; Imamura, S.; Koshimizu, E.; Zhao, J.; Kishi, S.; Yamashita, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Sukhatme, V.P.; Lecker, S.H. The muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1/MAFbx mediates statin-induced muscle toxicity. J Clin Invest 2007, 117(12), 3940–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norata, G.D.; Tibolla, G.; Catapano, AL. Statins and skeletal muscles toxicity: from clinical trials to everyday practice. Pharmacol Res 2014, 88, 107–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.T.; Staffa, J.A.; Parks, M.; Green, L. Rhabdomyolysis with HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and gemfibrozil combination therapy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004, 13(7), 417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Roeters van Lennep, J.E.; Tokgözoğlu, L.; Badimon, L.; Baigent, C.; Benn, M.; Binder, C.J.; Catapano, A.L.; De Backer, G.G.; ESC/EAS Scientific Document Group. Focused update 2025 delle linee guida ESC/EAS 2019 per il trattamento delle dislipidemie. Giornale Italiano di Cardiologia 2025, 26, e1–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, D.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Albert, M.A.; Buroker, A.B.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hahn, E.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Khera, A.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; McEvoy, J.W.; et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 140(11), e596–e646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Cardiovascular Disease: Risk Assessment and Reduction, Including Lipid Modification Guideline. 2023–2024. NICE guideline, NG238, 2023. In https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng238 (14.12.2025).

- Friedman, L.M.; Furberg, C.; DeMets, D.L.; Reboussin, D.M.; Granger, C.B. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials, 5th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, P.M. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “To whom do the results of this trial apply?”. The Lancet 2005, 365, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, J.H.; Bertoni, A.G.; Staten, L.K.; Levine, R.S.; Gross, C.P. Participation in clinical trials among elderly adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2006, 54, 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lagakos, S.W.; Ware, J.H.; Hunter, D.J.; Drazen, J.M. Statistics in medicine—Reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med 2007, 357, 2189–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.W.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Haahr, M.T.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Altman, D.G. Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials. JAMA 2004, 291, 2457–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. Why are most published research findings false. PLoS Medicine 2005, 2, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catapano, A.L.; Barrios, V.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Pirro, M. Lifestyle interventions and nutraceuticals: Guideline-based approach to cardiovascular disease prevention. Atherosclerosis Supplements 2019, 39, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Bai, X.; Yang, Y.; Cui, J.; Xu, W.; Song, L.; Yang, H.; He, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Lu, J. Healthy lifestyle, statin, and mortality in people with high CVD risk: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Am J Prev Cardiol 2024, 17, 100635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, J.; Cobbe, S.M.; Ford, I.; Isles, C.G.; Lorimer, A.R.; MacFarlane, P.W.; McKillop, J.H.; Packard, C.J. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med 1995, 333(20), 1301–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovesi, S.; Vania, A.; Caroli, M.; Orlando, A.; Lieti, G.; Parati, G.; Giussani, M. Non-Pharmacological Treatment for Cardiovascular Risk Prevention in Children and Adolescents with Obesity. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, J. The safety of statins in clinical practice. Lancet 2007, 370(9601), 1781–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bélanger, A.; Desjardins, C.; Leblay, L.; Filiatrault, M.; Barbier, O.; Gangloff, A.; Leclerc, J.; Lefebvre, J.; Zongo, A.; Drouin-Chartier, J.P. Relationship Between Diet Quality and Statin Use Among Adults With Metabolic Syndrome From the CARTaGENE Cohort. CJC Open 2023, 6(1), 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, P.; Di Girolamo, F.G.; Pellicori, F.; Panizon, E.; Pirulli, A.; Tosoni, L.M.; Altamura, N.; Rizzo, S.; Perin, A.; Fiotti, N.; et al. Statin-Intolerant Patients Exhibit Diminished Muscle Strength Regardless of Lipid-Lowering Therapy. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsson, E.S. Hepatotoxicity of statins and other lipid-lowering agents. Liver Int 2017, 37(2), 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.A.; Thompson, P.D. Statin-Associated Muscle Disease: Advances in Diagnosis and Management. Neurotherapeutics 2018, 15(4), 1006–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attardo, S.; Musumeci, O.; Velardo, D.; Toscano, A. Statins Neuromuscular Adverse Effects. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23(15), 8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramkumar, S.; Raghunath, A.; Raghunath, S. Statin Therapy: Review of Safety and Potential Side Effects. Acta Cardiol Sin 2016, 32(6), 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littarru, G.P.; Langsjoen, P. Coenzyme Q10 and statins: biochemical and clinical implications. Mitochondrion 2007, 7 Suppl, S168–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bookstaver, D.A.; Burkhalter, N.A.; Hatzigeorgiou, C. Effect of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on statin-induced myalgias. Am J Cardiol 2012, 110(4), 526–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Khan, N.; Glueck, C.J.; Pandey, S.; Wang, P.; Goldenberg, N.; Uppal, M.; Khanal, S. Low serum 25 (OH) vitamin D levels (<32 ng/mL) are associated with reversible myositis‐myalgia in statin‐treated patients. Transl Res 2009, 153(1), 11–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennisi, M.; Di Bartolo, G.; Malaguarnera, G.; Bella, R.; Lanza, G.; Malaguarnera, M. Vitamin D Serum Levels in Patients with Statin-Induced Musculoskeletal Pain. Dis Markers 2019, 2019, 3549402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlatky, M.A.; Gonzalez, P.E.; Manson, J.E.; et al. Statin-Associated Muscle Symptoms Among New Statin Users Randomly Assigned to Vitamin D or Placebo. JAMA Cardiol 2023, 8(1), 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, M.; Patti, A.M.; Giglio, R.V.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Atanasov, A.G.; Bajraktari, G.; Bruckert, E.; Descamps, O.; Djuric, D.M.; Ezhov, M.; et al. International Lipid Expert Panel (ILEP). The Role of Nutraceuticals in Statin Intolerant Patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 72(1), 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akyea, R.K.; Kai, J.; Qureshi, N.; Iyen, B.; Weng, S.F. Sub-optimal cholesterol response to initiation of statins and future risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart 2019, 105, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; Costanzo, S.; Persichillo, M.; De Curtis, A.; Cerletti, C.; Donati, M.B.; de Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Moli-sani Study Investigators. Interaction between Mediterranean diet and statins on mortality risk in patients with cardiovascular disease: Findings from the Moli-sani Study. Int J Cardiol 2019, 276, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) Scientific Opinion on the Risks for Public and Animal Health Related to the Presence of Citrinin in Food and Feed. EFSA J 2012, 10, 2605. [CrossRef]

- Capra, M.E.; Biasucci, G.; Banderali, G.; Vania, A.; Pederiva, C. Diet and Lipid-Lowering Nutraceuticals in Pediatric Patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Children 2024, 11, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhou, J.; Yuan, Z. Meta-Analysis Comparing the Effect of Combined Omega-3 + Statin Therapy Versus Statin Therapy Alone on Coronary Artery Plaques. Am J Cardiol 2021, 151, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.; Kim, J. Comparative Effect of Statins and Omega-3 Supplementation on Cardiovascular Events: Meta-Analysis and Network Meta-Analysis of 63 Randomized Controlled Trials Including 264,516 Participants. Nutrients 2020, 12(8), 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Lincoff, A.M.; Garcia, M.; et al. Effect of High-Dose Omega-3 Fatty Acids vs Corn Oil on Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk: The STRENGTH Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020, 324(22), 2268–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunwald, S.A.; Popp, O.; Haafke, S.; Jedraszczak, N.; Grieben, U.; Saar, K.; Patone, G.; Kress, W.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; Dittmar, G.; Spuler, S. An eicosanoid protects from statin-induced myopathic changes in primary human cells. bioRxiv 2019, 271932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerino, G.M.; Tarantino, N.; Canfora, I.; De Bellis, M.; Musumeci, O.; Pierno, S. Statin-Induced Myopathy: Translational Studies from Preclinical to Clinical Evidence. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; Xin, X.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Q.; Naveed, M.; Kaiyan, C.; Xiao, P. Effects of coenzyme Q10 supplementation on statin-induced myopathy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ir J Med Sci 2022, 191(2), 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholle, J.M.; Baker, W.L.; Talati, R.; Coleman, C.I. The effect of adding plant sterols or stanols to statin therapy in hypercholesterolemic patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Nutr 2009, 28(5), 517–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Jiao, J.; Xu, J.; Zimmermann, D.; Actis-Goretta, L.; Guan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Qin, L. Effects of plant stanol or sterol-enriched diets on lipid profiles in patients treated with statins: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 31337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebkar, A.; Cicero, A.F.G.; Banach, M. Pathophysiological mechanisms of statin-associated myopathies: possible role of the ubiquitin–proteasome system. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11(4), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, C.A.; Pol, D.; Zacharewicz, E.; et al. Statin-induced increases in atrophy gene expression occur independently of changes in PGC1α protein and mitochondrial content. PLoS One 2015, 10(5), e0128398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Antona, G.; Ragni, M.; Cardile, A.; et al. Branched-chain amino acid supplementation promotes survival and supports cardiac and skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis in middle-aged mice. Cell Metab 2010, 12(4), 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedesco, L.; Corsetti, G.; Ruocco, C.; Ragni, M.; Rossi, F.; Carruba, O.; Valerio, A.; Nisoli, E. A specific amino acid formula prevents alcoholic liver disease in rodents. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2018, 314(5), G566–G582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, G.; Romano, C.; Codenotti, S.; Pasini, E.; Fanzani, A.; Dioguardi, F.S. Essential Amino Acids-Rich Diet Decreased Adipose Tissue Storage in Adult Mice: A Preliminary Histopathological Study. Nutrients 2022, 14(14), 2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, E.; Corsetti, G.; Dioguardi, F.S. Behind Protein Synthesis: Amino Acids-Metabokine Regulators of Both Systemic and Cellular Metabolism. Nutrients 2023, 15(13), 2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirtori, C.R.; Lovati, M.R.; Manzoni, C.; Monetti, M.; Pazzucconi, F.; Gatti, E. Soy and cholesterol reduction: clinical experience. J Nutr 1995, 125(3 Suppl), 598S–605S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, S.M. Overview of proposed mechanisms for the hypocholesterolemic effect of soy. J Nutr 1995, 125(3 Suppl), 606S–611S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Colletti, A.; Bajraktari, G.; et al. Lipid lowering nutraceuticals in clinical practice: position paper from an International Lipid Expert Panel. Arch Med Sci 2017, 13, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirtori, C.R.; Pazzucconi, F.; Colombo, L.; et al. Double-blind study of the addition of high-protein soya milk v. cows' milk to the diet of patients with severe hypercholesterolaemia and resistance to or intolerance of statins. Br J Nutr 1999, 82, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B.A.; Panza, G.; Ballard, K.D.; White, C.M.; Thompson, P.D. Creatine Supplementation Does Not Alter the Creatine Kinase Response to Eccentric Exercise in Healthy Adults on Atorvastatin. J Clin Lipidol 2018, 12(5), 1305–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewmon, D.A.; Craig, J.M. Creatine supplementation prevents statin-induced muscle toxicity. Ann Internal Med 2010, 153, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrino, M.; Adriano, E. Statin-induced myopathy prevented by creatine administration. BMJ Case Rep 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarsi, E.; Dorighi, U.; Adriano, E.; Grandis, M.; Balestrino, M. Low-Dose Creatine Supplementation May Be Effective in Early-Stage Statin Myopathy: A Preliminary Study. J Clin Med 2024, 13(23), 7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilani, R.; D'Antona, G.; Baiardi, P.; Gambino, A.; Iadarola, P.; Viglio, S.; Pasini, E.; Verri, M.; Barbieri, A.; Boschi, F. Essential amino acids and exercise tolerance in elderly muscle-depleted subjects with chronic diseases: a rehabilitation without rehabilitation? Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 341603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilani, R.; Boselli, M.; Boschi, F.; Viglio, S.; Iadarola, P.; Dossena, M.; Pastoris, O.; Verri, M. Branched-chain amino acids may improve recovery from a vegetative or minimally conscious state in patients with traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008, 89(9), 1642–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquilani, R.; Zuccarelli, G.C.; Dioguardi, F.S.; Baiardi, P.; Frustaglia, A.; Rutili, C.; Comi, E.; Catani, M.; Iadarola, P.; Viglio, S.; et al. Effects of oral amino acid supplementation on long-term-care-acquired infections in elderly patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2011, 52(3), e123-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfield, C.; Bradshaw, P.C. Amino acids in the regulation of aging and aging-related diseases. Translational Medicine of Aging 2019, 3, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragni, M.; Ruocco, C.; Tedesco, L.; Carruba, M.O.; Valerio, A.; Nisoli, E. An amino acid-defined diet impairs tumour growth in mice by promoting endoplasmic reticulum stress and mTOR inhibition. Mol Metab 2022, 60, 101478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corsetti, G.; Romano, C.; Codenotti, S.; Pasini, E.; Fanzani, A.; Scarabelli, T.; Dioguardi, F.S. A Diet Rich in Essential Amino Acids Inhibits the Growth of HCT116 Human Colon Cancer Cell In Vitro and In Vivo. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26(14), 7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, G.; D'Antona, G.; Ruocco, C.; Stacchiotti, A.; Romano, C.; Tedesco, L.; Dioguardi, F.; Rezzani, R.; Nisoli, E. Dietary supplementation with essential amino acids boosts the beneficial effects of rosuvastatin on mouse kidney. Amino Acids 2014, 46(9), 2189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Antona, G.; Tedesco, L.; Ruocco, C.; Corsetti, G.; Ragni, M.; Fossati, A.; Saba, E.; Fenaroli, F.; Montinaro, M.; Carruba, M.O.; et al. A Peculiar Formula of Essential Amino Acids Prevents Rosuvastatin Myopathy in Mice. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016, 25(11), 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).