1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the foremost cause of death all over the world, contributing to approximately 18 million deaths annually [

1]. In Greece, CVD continues to be the leading cause of mortality and morbidity, despite the low rates recorded in the 1950s and 1960s, when the country was considered privileged in terms of cardiovascular health. According to the ATTICA epidemiological study, the incidence of cardiovascular disease in Greece reaches 360 cases per 10,000 individuals over a 20-year follow-up period (2002-2022), indicating a high lifetime risk of developing cardiovascular disease [

2]. Beyond the estimation of cardiovascular disease-related deaths, there is growing concern about its substantial burden, as it ranks first compared to other diseases. In 2021, CVD was responsible for 14.9% of the total loss of healthy life years due to either premature mortality or disability [

3,

4].

Dietary modifications play a pivotal role in the secondary and tertiary prevention of cardiovascular disease. According to the literature, a diet rich in unsaturated fats and low in saturated fats is highly beneficial for patients with cardiovascular diseases, including those who have undergone Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting (CABG) as well as those with other forms of CVD such as heart failure, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease. Many studies have documented the value of a well-balanced diet in beneficial patient outcomes, including healthier metabolic profiles, reduced inflammation, enhanced overall cardiovascular function, as well as diminished mortality rates [

5,

6].

For instance, a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole-grain cereals, and lean proteins has been consistently associated with better clinical outcomes and fewer complications in patients with cardiovascular diseases. These dietary patterns help regulate blood pressure, improve lipid profiles, and reduce the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events [

7]. The Mediterranean diet is widely conceded as the most appropriate dietary model for cardiovascular patients due to its emphasis on plant-based foods, healthy fats (such as olive oil), and moderate consumption of fish and poultry. This diet has been shown to significantly reduce mortality, morbidity, and complications such as angina and acute myocardial infarction [

8,

9].

Beyond its physical health benefits, the Mediterranean diet also positively impacts psychological well-being. Unsanitary dietary habits, such as high consumption of processed foods and saturated fats, have been linked to increased levels of anxiety, stress, and depression, which can deteriorate cardiovascular outcomes [

10,

11]. For instance, patients with heart failure who adhere to a poor diet pattern often experience higher levels of psychological distress, which can worsen their condition, lessening their quality of life [

12]. Additionally, cognitive impairments, such as delirium and mild cognitive decline, are more frequent among cardiovascular patients with improper dietary habits, further underscoring the importance of a healthy diet in maintaining both physical and mental health [

12].

Despite the well-documented benefits of a healthy diet, adherence to dietary recommendations remains suboptimal for individuals with various forms of cardiovascular disease. Studies have identified several barriers to dietary adherence, such as lack of patient education, limited access to healthy foods, socioeconomic challenges, cultural factors, and insufficient follow-up care [

13,

14]. The first and crucial step to confront this issue is the reliable estimation of the nutritional status of these patients to plan and perform specific and systematic interventions trying to reverse the existing problematic situation and alleviate all the associated obstacles that impede the adoption of a healthy diet pattern among cardiovascular patients.

The Cardiovascular Diet Questionnaire 2 (CDQ-2) is a validated dietary assessment tool originally developed for the French population by Paillard et al. (2020), designed to evaluate dietary habits in patients with cardiovascular diseases. According to its nature and content, it provides a comprehensive assessment of nutrient intake based on a seven-day dietary history and biomarkers. Additionally, this tool captures both qualitative and quantitative aspects of diet, making it a robust tool for clinical and research settings [

15].

The purpose of the present study was a) to translate into the Greek language and validate the CDQ-2 for the Greek-speaking population of cardiovascular patients and b) to assess their dietary status, identifying the factors influencing it. This study intends to add useful new data to the existing body of literature by providing a culturally adapted and validated dietary tool for the Greek-speaking population, which can serve many research and clinical purposes in the field of cardiovascular prevention and holistic care. Additionally, it could provide a comprehensive understanding of the current dietary status of cardiovascular patients and the influencing factors, offering insights into tailoring personalized interventions and policies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design

This was a cross-sectional observational study. The study population was cardiovascular disease patients, users of a private Primary Health Care clinic. The convenience sampling method was used to collect data from December 2024 to January 2025. Participants who are eligible to take part in the study should be men or women aged 18 years and above who have been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease. Moreover, they should be able to read and write in Greek to ensure they can understand the study materials and take part in the related assessments effectively. Only individuals who willingly agree to participate in the study will be included in the enrollment process. As an exclusion criterion, we used the history of psychiatric illness, the recent history of alcohol and/or drug abuse, dementia, and Alzheimer's disease.

2.2. Translation of CDQ-2

The process involved an independent translation of the original French forward translation by two separate individuals. After this phase, a third individual compared the two translations and was able to determine an agreed-upon translation (1st reconciliation version). A bilingual individual, whose mother tongue was French, was a professional translator who later translated the agreed-upon version into the original questionnaire's language (backward translation). However, the individual was unaware of the questionnaire's standard format.

Twenty patients with cardiovascular disease completed the translated version of the questionnaire to evaluate its apparent validity (face validity), which verifies that the scale includes questions that are relevant to the characteristic being measured and does not lead to inaccurate or incomplete responses. Additionally, three eHealth specialists reviewed the questionnaire, giving them the cognitive capacity to assess the tool and suggest ways to make it better (Content Validity). In the final version of the instrument, items with a Coefficient Validity Ratio (CVR) greater than 0.70 were retained.

2.3. Reliability

To measure the reliability of a scale, the internal consistency coefficient Cronbach's alpha was calculated, which evaluates the degree to which the questions that make up a scale measure the same concept. Values greater than or close to 0.70 (70%) are considered acceptable. An internal consistency coefficient between 0.50 and 0.60 (50-60%) is considered sufficient in the early stages of the study. If the value exceeds 0.80 (80%), then it is considered a particularly good reliability analysis.

2.4. Validity

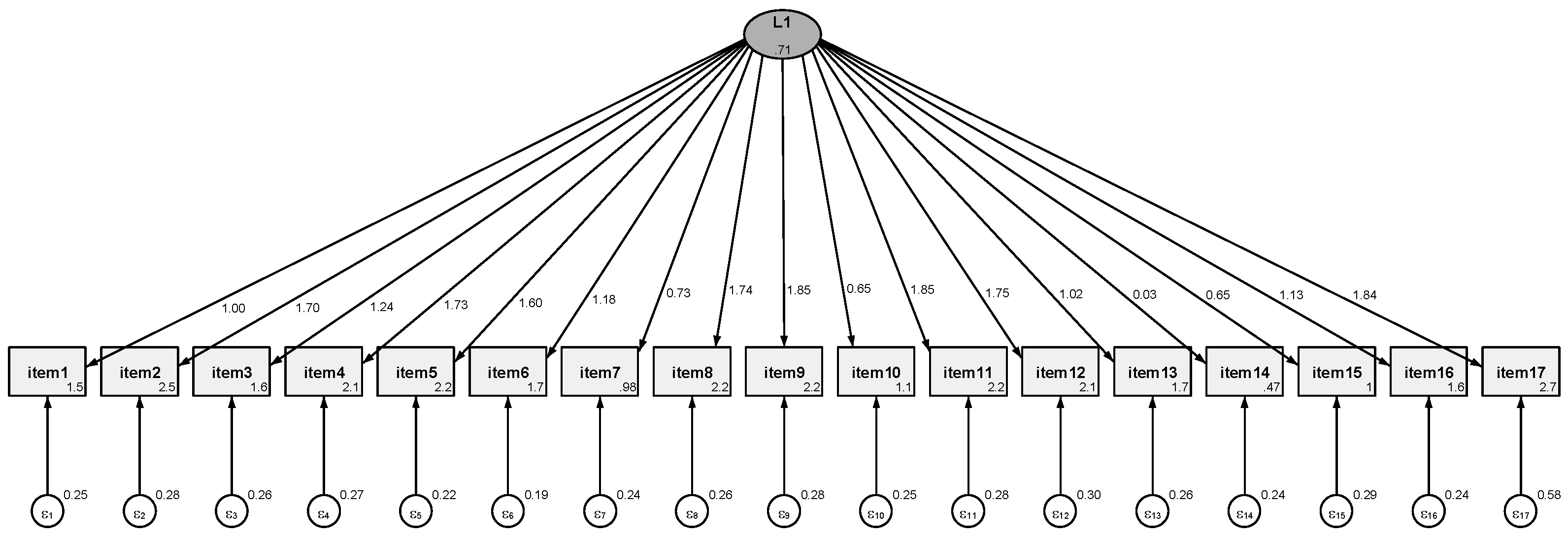

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to determine the model’s fit. Adequate or good fit was indicated by a Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR) less than or equal to 0.08, Coefficient of Determination (CD) greater than or equal to 0.90, and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) greater than or equal to 0.90.

Construct validity was determined using Pearson's correlation between CDQ-2 and the selected gold standard questionnaire

2.5. Translation and weighting questionnaire

Data was collected using an anonymous self-report questionnaire, consisting of three sub-sections:

-The first concerns the following demographic characteristics: a) age, b) biological sex, c) educational level, d) subjective economic situation, e) family situation.

-The CDQ-2 includes 17 closed-ended questions designed to identify major sources of nutrients. For each of the 9 questions related to saturated fatty acid (SFA) intake, the total score ranges from 0 to 27. Monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA) intake is investigated with one question (total score range 0–6). Omega-3 fatty acid (ω3FA) intake is investigated with 3 questions (total score range 0-10). Finally, there are 4 questions on fruit and vegetable (FV) consumption (range 0-14). The total nutritional score is calculated as [(FV + MUFA + ω3FA) – SFA], fluctuating from -27 to +30. Higher scores indicate better nutrition, whereas the existing literature does not provide universal cut-off points.

MEDAS was created by Spanish researchers [

16] and has been weighted and translated respectively by Greek researchers [

17]. This tool consists of 14 questions (total score range 0-14) about the main food groups consumed as part of the Mediterranean Diet, which is a valid means of rapidly assessing adherence to it. Higher scores indicate the healthiest dietary pattern, while a score ≥ 10 is considered indicative of high adherence [

18]. It is known that the dietary pattern associated with the Mediterranean Diet is characterized by daily consumption of olive oil (mainly extra virgin), whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. The Mediterranean diet is a rich source of essential minerals, vitamins, and fiber and is considered one of the healthiest dietary patterns.

3.6. Statistical methodology

We performed the statistical analysis using STATA software (version 12.0; Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) for the confirmatory factor analysis and SPSS statistical software (version 27; SPSS, Chicago, Ill) for the remainder. For the descriptive statistical analysis, the continuous variables are given as mean value and standard deviation, while the discrete ones are given as absolute and relative frequency. Multiple Logistic Regression was used to investigate the independent variables (Age, Biological sex, Higher level of education, Economic level, Marital status, Physical activity, Smoking, and Alcohol consumption) that can predict the dependent variable (CDQ-2). The minimum value of the statistical significance level was set at 5%. To weigh the CDQ-2 questionnaire, the following steps were followed: a) bilingual translation (Forward Translation, Reconciliation Report, Backward Translation), b) Cognitive Debriefing Process of the questionnaire, through pilot data collection of a small sample of participants (10- 15 people), to fully oversee the formation of the final form of the translated questionnaire, c) calculation of questionnaire reliability using the repeatability method, d) calculation of concurrent validity (the MEDAS questionnaire will be used as the gold standard) and e) calculation of validity through Confirmatory Factor Analysis. For the Confirmatory Factor Analysis, the calculation of the minimum required sample showed that for a number of 17 items, one factor, a type I error equal to 5%, a power of 80%, and an effect size of 0, 1, at least 87 participants are needed.

3. Results

The total sample comprised 90 individuals, 13 (14.4 %) females and 77 (85.6 %) males, and mean aged 63.8 ± 9.6 years. Single or divorced or widowed were 30 (33.3 %) and married or cohabiting were 60 (66.7 %). Up to secondary education were 21 (23.3 %), post-secondary non-tertiary education 41 (45.6 %), tertiary education 21 (23.3 %), and MSc or PhD were 7 (7.8 %). Twenty-four (26.7%) of the participants were of a low economic level, while 50 (55.6 %), and 16 (17.8 %) of them were of a middle and a high economic level, respectively. Low physical level had 32 (35.6 %) participants, middle level 43 (47.8 %), and high 15 (16.7 %). Of the participants, 19 (21.1%) reported non-consumption of alcohol, 55 (61.1%) reported moderate consumption, and 16 (17.8%) reported high consumption (

Table 1). The CVR results, for CDQ-2, showed that 100% of items (n = 17) were acceptable and Cronbach’s α was 0.97. A one-factor model conducted by CFA (figure 1) yielded acceptable global fit indices (SRMR = 0.08, CD = 0.99, CFI = 0.99) and indicated that the 17 items in the one-factor solution proposed by the principal investigators should be accepted for the Greek version of the CDQ-2 (

Figure 1). The mean score of CDQ-2 was 2.9 (SD = 17.2) and of MEDAS was 8 (SD = 5.2). A bivariate Pearson's correlation established that there was a strong, statistically significant linear relationship between CDQ-2 and MEDAS scores, r (90) = 0.962, p < 0.001.

A multivariate analysis was performed to ascertain the effects of independent variables, including age, biological sex, level of education, economic level, marital status, physical activity, smoking, and alcohol consumption, on the CDQ-2 score. The multiple linear regression model was statistically significant, F (8, 81) = 75.4, p < 0.001. The model explained 87 % (Adjusted R Square) of the variance in the score of CDQ-2. As shown in

Table 2, of the eight predictor variables, only the following five were statistically significant: 1) age (p < 0.001), 2) biological sex (p = 0.042), 3) marital status (p < 0.001), 4) physical activity (p = 0.001), and 5) smoking (p = 0.022). Specifically, younger age, male sex, being single/divorced/widowed, lower physical activity levels, and active smoking status were strongly associated with lower CDQ-2 scores (

Table 2 & Table 3).

4. Discussion

As aforementioned, the participants’ healthy diet adherence seems to be suboptimal according to the mean scores of both the MEDAS and CDQ-2, while by using multivariate analysis several socio-demographic parameters, including age, biological sex, marital status, physical activity levels, and smoking status, were identified as predictors of decreased CDQ-2 scores and insufficient dietary habits. However, the Greek version of the CDQ-2 seems to be a quite valid and reliable tool for the Greek-speaking cardiovascular patients’ setting.

Specifically, the participants are not characterized by optimal adherence to the proper diet habits. Despite the benefits of optimal diet habits for patients with cardiovascular diseases being distinct and well-documented in terms of lower morbidity [

19,

20] and mortality rates [

20,

21] many studies are in line with our findings revealing inadequate adherence observed even to the Mediterranean Diet among the inhabitants of the Mediterranean countries [

22,

23,

24]. This finding is indicative of poor self-management and self-care behavior, jeopardizing the secondary and tertiary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Adopting suboptimal adherence to a well-known advantageous diet archetype constitutes a global issue that should be addressed by more systematic, personalized, and not generic interventions.

Additionally, younger patients exhibited lower CDQ-2 scores, suggesting diminished adherence to the recommended eating patterns. This finding is in line with prior studies indicating that older individuals are generally more compliant with healthy dietary recommendations and guidelines, potentially due to increased awareness of secondary prevention measures and existing comorbidities [

1,

2]. Younger patients, even those already diagnosed with cardiovascular disease, may underestimate their risk, leading to a false sense of security which impedes them from activating healthier diet habits. On the contrary, older patients are more likely to adhere to healthier dietary patterns, possibly motivated by the presence of multiple health disorders and concerns about severe cardiovascular events.

Similarly, male sex was found to be significantly associated with lower CDQ-2 scores, suggesting a gender gap in dietary adherence among cardiovascular patients. This is consistent with findings from previous studies indicating that women are more likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors, including healthier eating habits and greater compliance with dietary recommendations [

25,

26]. Possible explanations for this disparity include higher health literacy levels among women, increased involvement in food preparation, and greater concern for long-term health outcomes. Additionally, traditional gender roles and sociocultural perceptions around masculinity may discourage men from prioritizing dietary changes, especially in older age groups [

27].

Regarding marital status, being single, divorced, or widowed was associated with significantly lower adherence to cardiovascular dietary guidelines. Several studies have highlighted the protective effect of marriage or cohabitation on health behaviors and outcomes, including diet quality [

28,

29]. Living with a partner may provide emotional support, shared responsibility in meal planning, and accountability, which contribute to better adherence. Conversely, individuals who live alone may experience lower motivation to maintain structured eating habits or may resort to convenience and processed foods, especially in the context of older age and chronic illness [

30].

Physical activity level was another significant determinant of CDQ-2 scores, with lower activity levels correlating with poorer dietary patterns. This finding aligns with literature suggesting that health-related behaviors tend to cluster together, with physically active individuals more likely to engage in healthy eating [

31]. It has been proposed that physical activity improves self-regulation and health consciousness, which may influence dietary decisions. Additionally, individuals who exercise regularly are often exposed to health promotion environments or programs that reinforce positive dietary habits [

32].

Active smoking was independently associated with lower CDQ-2 scores. Smokers are generally less likely to follow health guidelines, possibly due to a lower perceived vulnerability to disease or a higher tendency for risk-taking behavior [

33]. Moreover, smoking is often co-occurring with other unhealthy lifestyle choices, including poor dietary habits, low physical activity, and high alcohol consumption [

34]. This behavioral clustering underlines the importance of integrated lifestyle interventions that address multiple modifiable risk factors simultaneously in cardiovascular patients.

Additionally, this was a clinical study aimed at translating and validating a disease-specific dietary tool, namely the CDQ-2, for assessing dietary habits among patients with cardiovascular disease, based on a seven-day dietary history and biomarkers. The Greek version of the CDQ-2 demonstrated good construct and face validity. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.97 for the entire scale, confirming the internal consistency of the tool in line with the validation analysis. According to the CFA, a one-factor solution comprising all 17 items was proposed and accepted for the Greek version of the CDQ-2. Therefore, the CDQ-2 is a valid and reliable tool, recommended for use as an overall scale. Moreover, CFA indicated acceptable global fit indices (SRMR = 0.08, CD = 0.99, CFI = 0.99).

We used the MEDAS questionnaire as the gold standard to calculate the concurrent validity of the CDQ-2. The MEDAS assessed the main food groups consumed in the Mediterranean Diet. The analysis showed that the mean CDQ-2 total score was 2.9 (SD = 17.2), while the mean MEDAS total score was 8 (SD = 5.2). A bivariate Pearson’s correlation revealed a strong, statistically significant linear relationship between CDQ-2 and MEDAS total scores, r (90) = 0.962, p < 0.001. This finding underscores the robustness of the CDQ-2 in estimating dietary adherence within the cardiovascular setting.

Finally, according to the CFA, the calculation of the minimum required sample indicated that at least 87 participants were needed for the entire scale. The total sample enrolled in the present study was 90 individuals, thus supporting the adequacy of the sample size and the reliability of the findings.

5. Conclusions

The survey supports the validity and reliability of the CDQ-2 among cardiovascular patients in Greece, while the strong correlation between CDQ-2 and MEDAS scores underscores the robustness of the CDQ-2 in assessing dietary adherence within this population group. Cardiovascular patients seem to have suboptimal dietary patterns as indicated by the relatively low mean CDQ-2 score of 2.9 (SD = 17.2), along with a mean MEDAS score of 8 (SD = 5.2), with younger, males, single/divorced/widowed, individuals with lower physical activity and active smokers demonstrating poorer adherence to the optimal and beneficial cardiovascular dietary status. Healthcare providers could incorporate the CDQ-2 in routine clinical practice to identify patients with a lower capacity to follow and adopt the recommended dietary modifications. Future research is needed to inform clinical practitioners and support the design of tailored and personalized interventions for improving dietary behaviors among cardiovascular patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.G., E.P., A.A.C., D.A., N.V., H.B., N.V.F., E.G., and A.E.P; methodology, K.G., E.P., A.A.C., D.A., N.V., H.B., N.V.F., E.G., and A.E.P; software, K.G., E.P., A.A.C., and A.E.P; validation, K.G., E.P., D.A., N.V., H.B., and A.E.P.; formal analysis, K.G., E.P., A.A.C., D.A, N.V.F., and A.E.P; investigation, K.G., E.P., A.A.C., D.A., and A.E.P; resources, K.G., E.P., N.V.F., E.G., and A.E.P; writing—original draft preparation, K.G., E.P., A.A.C., D.A., and A.E.P; writing—review and editing, K.G., E.P., A.A.C., D.A., N.V., H.B., N.V.F., E.G., and A.E.P; supervision, K.G., and A.E.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the relevant Research Ethics Committees of the Hellenic Mediterranean University (protocol code 29563 approved 08 November 2024). Permission was obtained from the creators to translate, validate, and use the CDQ-2 from its creators. Similarly, to use the MEDAS tool, permission was obtained from both its developers and the researchers who validated the Greek version.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their voluntary participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vanzella, L.M.; Rouse, V.; Ajwani, F.; Deilami, N.; Pokosh, M.; Oh, P.; Ghisi, G.L.M. Barriers and facilitators to participant adherence of dietary recommendations within comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programmes: a systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2021, 24, 4823–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotakos, D.; Sigala, E.G.; Damigou, E.; Loukina, A.; Dalmyras, D.; Mentzantonakis, G.; Barkas, F.; Adamidis, P.S.; Kravvariti, E.; Liberopoulos, E. The burden of cardiovascular disease and related risk factors in Greece: the ATTICA epidemiological study (2002–2022). Hellenic J Cardiol. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vervoort, D.; Tchienga, D.; Ouzounian, M.; Mvondo, C.M. Thoracic aortic surgery in low- and middle-income countries: Time to bridge the gap? JTCVS Open. 2024, 19, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-J.; Ouyang, H.-Q.; Zhao, Z.-Y.; Li, W.-H.; Fall, I.S.; Djirmay, A.G.; Zhou, X.-N. Discrepancies in neglected tropical diseases burden estimates in China: comparative study of real-world data and Global Burden of Disease 2021 data (2004-2020). BMJ. 2025, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyan, G.N.; Reeder, K.M.; Vacek, J.L. Diet and exercise interventions following coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a review and call to action. Phys Sportsmed. 2014, 42, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casquel De Tomasi, L.; Salomé Campos, D.H.; Grippa Sant'Ana, P.; Okoshi, K.; Padovani, C.R.; Masahiro Murata, G.; Nguyen, S.; Kolwicz, S.C., Jr.; Cicogna, A.C. Pathological hypertrophy and cardiac dysfunction are linked to aberrant endogenous unsaturated fatty acid metabolism. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0193553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelman, D.T.; Ben Ali, W.; Williams, J.B.; Perrault, L.P.; Reddy, V.S.; Arora, R.C.; Roselli, E.E.; Khoynezhad, A.; Gerdisch, M.; Levy, J.H.; et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care in Cardiac Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Society Recommendations. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, M.I.; Corella, D.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Ruiz-Gutiérrez, V.; Fiol, M.; Lapetra, J.; et al. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, K.; Takeda, A.; Martin, N.; Ellis, L.; Wijesekara, D.; Vepa, A.; Das, A.; Hartley, L.; Stranges, S. Mediterranean-style diet for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019, 3, Cd009825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansone, R.A.; Dittoe, N.; Hahn, H.S.; Wiederman, M.W. The prevalence of borderline personality disorder in a consecutive sample of cardiac stress test patients. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011, 13, 27129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgazzar, E.; Ahmed, E.; Ahmed, S.A.; Karousa, M.M. Effects of betaine as feed additive on behavioral patterns and growth performance of Japanese quail. Benha Veterinary Medical Journal. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Saczynski, J.S.; Marcantonio, E.R.; Quach, L.; Fong, T.G.; Gross, A.; Inouye, S.K.; Jones, R.N. Cognitive trajectories after postoperative delirium. N Engl J Med. 2012, 367, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirão, S.; Costa, J.G.; Ferreira-Pêgo, C. Assessing knowledge and awareness of Food and Drug Interactions among nutrition sciences students: Implications for education and clinical practice. Nutr Health. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yancy, C.W.; Jessup, M.; Bozkurt, B.; Butler, J.; Casey Jr, D.E.; Colvin, M.M.; Drazner, M.H.; Filippatos, G.S.; Fonarow, G.C.; Givertz, M.M. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017, 70, 776–803. [Google Scholar]

- Paillard, F.; Flageul, O.; Mahé, G.; Laviolle, B.; Dourmap, C.; Auffret, V. Validation and reproducibility of a short food frequency questionnaire for cardiovascular prevention. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2021, 114, 570–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregório, M.J.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Salvador, C.; Dias, S.S.; de Sousa, R.D.; Mendes, J.M.; Coelho, P.S.; Branco, J.C.; Lopes, C.; Martínez-González, M.A. Validation of the telephone-administered version of the mediterranean diet adherence screener (Medas) questionnaire. Nutrients. 2020, 12, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalis, A.; Costarelli, V. The Greek version of the Mediterranean diet adherence screener: development and validation. Nutrition & Food Science 2021, 52, 129–139. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, L.M.; Gottschall, C.B.A.; Vinholes, D.B.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Marcadenti, A. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of 14-item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener and low-fat diet adherence questionnaire. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020, 39, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cangemi, R.; Miglionico, M.; D'Amico, T.; Fasano, S.; Proietti, M.; Romiti, G. F.; Corica, B.; Stefanini, L.; Tanzilli, G.; Basili, S.; Raparelli, V.; Tarsitano, M. G.; & Eva Collaborative Group. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet in Preventing Major Cardiovascular Events in Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease: The EVA Study. Nutrients. 2023, 15(14), 3150.

- Mertens, E.; Markey, O.; Geleijnse, J.M.; Lovegrove, J.A.; Givens, D.I. Adherence to a healthy diet in relation to cardiovascular incidence and risk markers: evidence from the Caerphilly Prospective Study. Eur J Nutr. 2018, 57(3), 1245–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furbatto, M.; Lelli, D.; Antonelli Incalzi, R.; Pedone, C. Mediterranean Diet in Older Adults: Cardiovascular Outcomes and Mortality from Observational and Interventional Studies—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2024, 16(22), 3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.; Chew, D.P.; Mamas, M.A.; Zaman, S. Cardiovascular Disease and the Mediterranean Diet: Insights into Sex-Specific Responses. Nutrients. 2024, 16(4), 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martimianaki, G.; Peppa, E.; Valanou, E.; Papatesta, E.M.; Klinaki, E.; Trichopoulou, A. Today’s Mediterranean Diet in Greece: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Survey—HYDRIA (2013–2014). Nutrients. 2022, 14(6), 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeid, C.A.; Gubbels, J.S.; Jaalouk, D.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Oenema, A. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet among adults in Mediterranean countries: a systematic literature review. Eur J Nutr. 2022, 61(7), 3327–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardle, J.; Haase, A.M.; Steptoe, A.; Nillapun, M.; Jonwutiwes, K.; Bellisle, F. Gender differences in food choice: the contribution of health beliefs and dieting. Ann Behav Med. 2004, 27, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.H.; Wardle, J. Sex differences in health behaviours in young adults. Psychol Health. 2003, 18, 651–668. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay, W.H. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000, 50, 1385–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Ryu, H.; Kang, H.S. The effects of marital status on health behaviors in middle-aged and elderly Koreans. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17, 628. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson, D. Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Soc Sci Med. 1992, 34, 907–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, K.L.; Collins, P.F. Relationship between living alone and food and nutrient intake. Nutr Rev. 2015, 73, 594–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenz, M.; Richter, T.; Mühlhauser, I. The morbidity and mortality associated with overweight and obesity in adulthood: a systematic review. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009, 106, 641–648. [Google Scholar]

- Plotnikoff, R.C.; Costigan, S.A.; Karunamuni, N.; Lubans, D.R. Social cognitive theories used to explain physical activity behavior in adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2013, 56, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spring, B.; Moller, A.C.; Coons, M.J. Multiple health behaviours: overview and implications. J Public Health (Oxf). 2012, 34 Suppl 1, i3–i10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W. The prevalence and clustering of four major lifestyle risk factors in an English adult population. Prev Med. 2007, 44, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).