Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Lay Summaries

Introduction

Methods

Study Population

Measurement of Dietary Intake and Development of the Plant-Based Heart-Protective Diet Scores

Cardiovascular Disease Incidence and Death

Cardiometabolic Outcomes

Statistical Analysis

Results

Sociodemographic and Dietary Characteristics of Participants

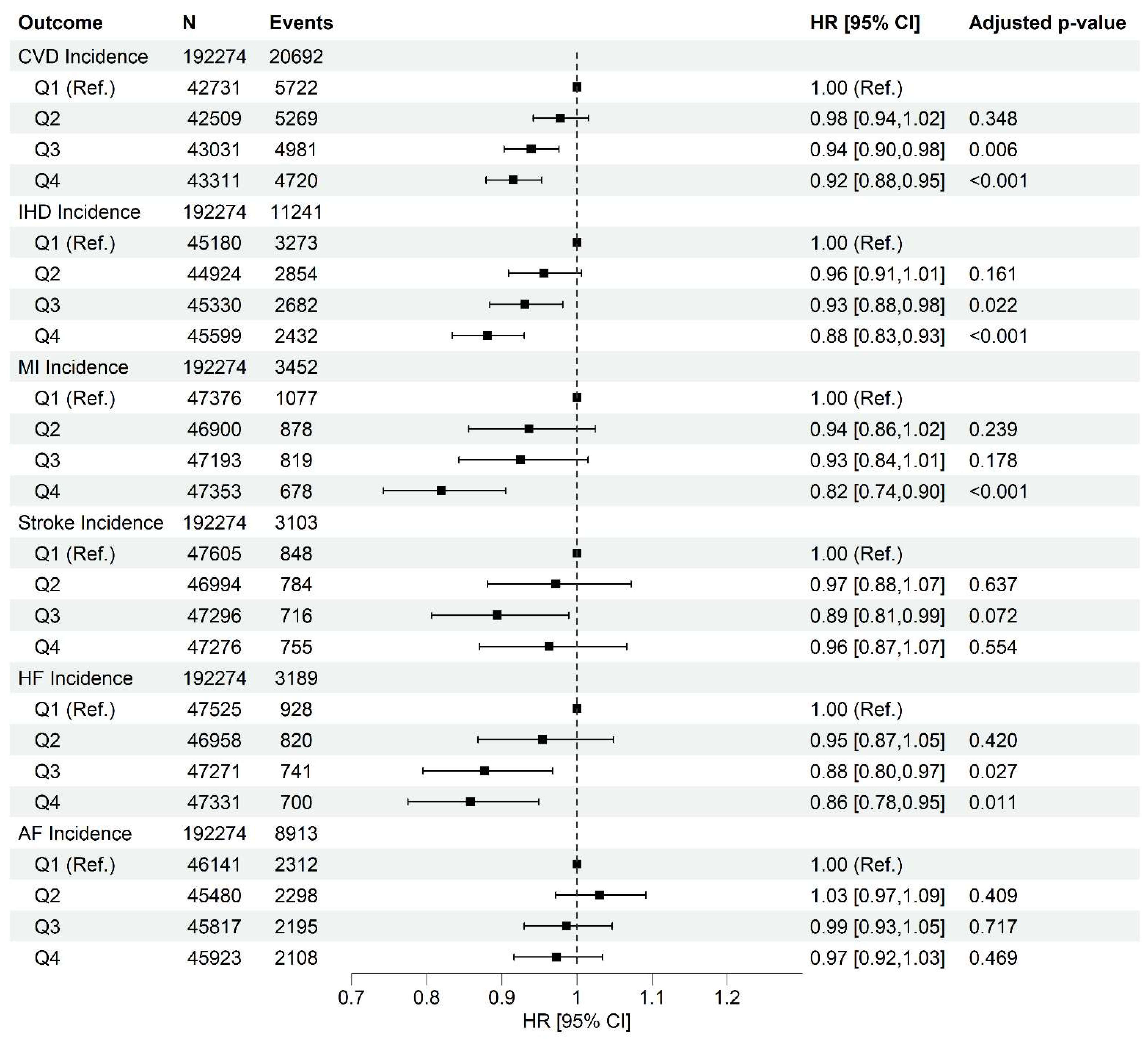

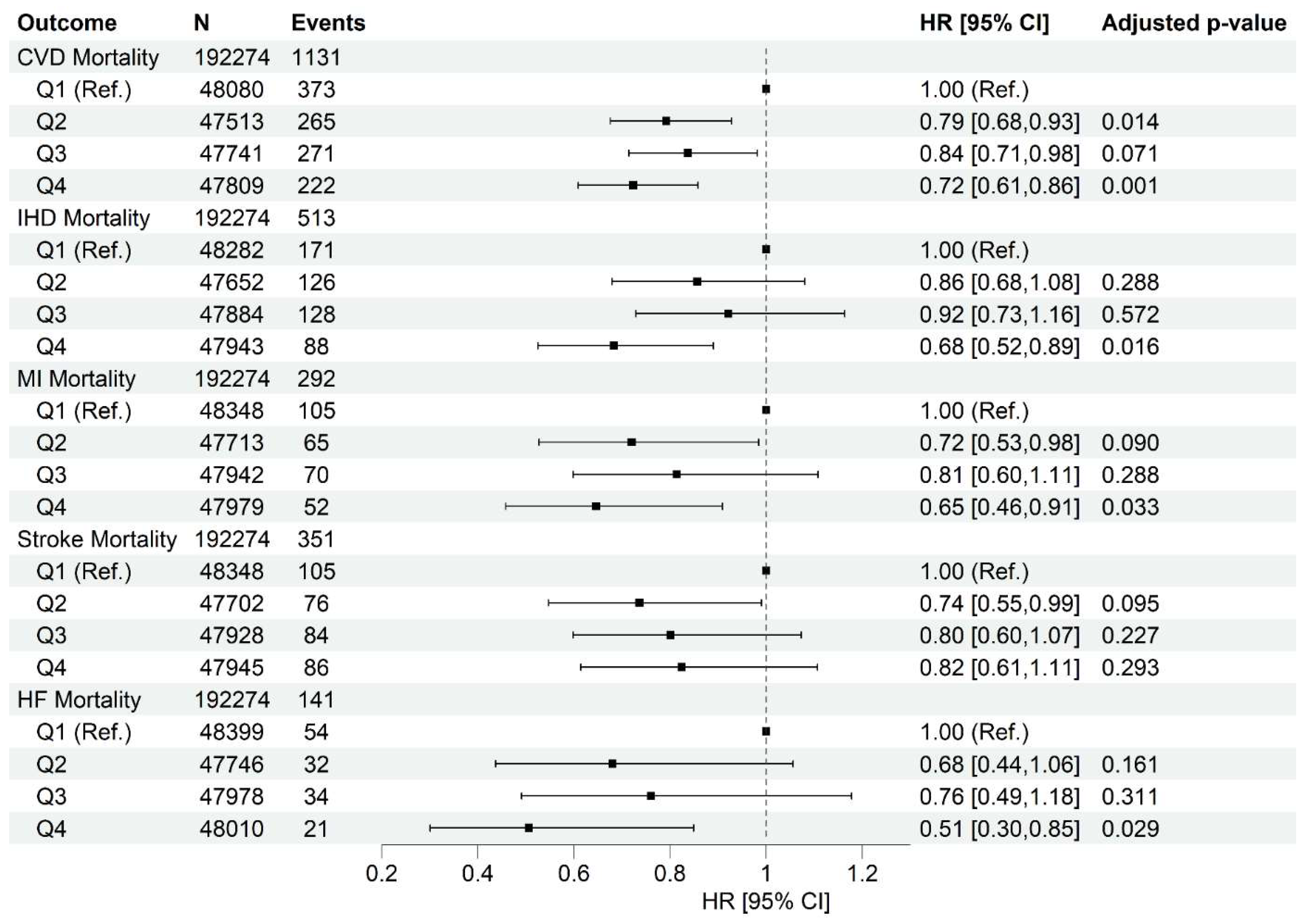

Higher Healthy Plant-Based Diet Score Is Associated with Lower Cardiovascular Diseases Incidence and Mortality

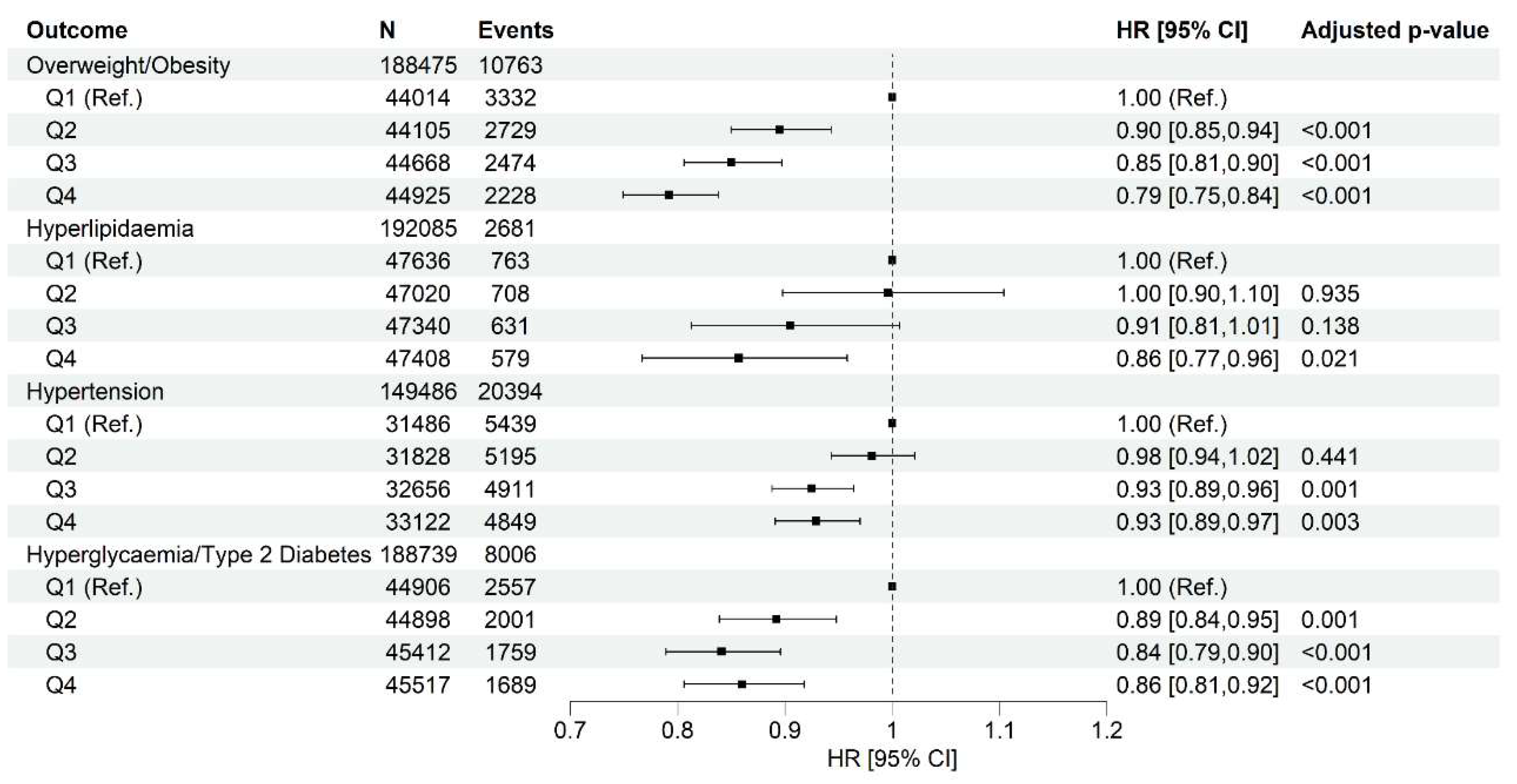

Higher Healthy Plant-Based Diet Score Is Associated with Lower Incidence of Cardiometabolic Abnormalities

Moderation Effects of Sex and Townsend Deprivation Index, and Sensitivity Analyses

Discussion

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions Statement

Funding/Support

Role of the Funders/Sponsors

Competing interests

Ethical approval

Data Availability Statement

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities

Disclosures

A short tweet summarizing this paper

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| AF | atrial fibrillation |

| BMI | body mass index |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| HF | heart failure |

| HPDS | heart-protective diet score |

| IHD | ischemic heart disease |

| MI | myocardial infarction |

References

- Timmis, A.; Vardas, P.; Townsend, N.; Torbica, A.; Katus, H.; De Smedt, D.; Gale, C.P.; Maggioni, A.P.; Petersen, S.E.; Huculeci, R.; et al. European Society of Cardiology: cardiovascular disease statistics 2021. Eur. Hear. J. 2022, 43, 716–799. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Vadiveloo M, Hu FB, Kris-Etherton PM, Rebholz CM, Sacks FM, Thorndike AN, Van Horn L, Wylie-Rosett J. 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021;144(23):e472-e487.

- Tosti, V.; Bertozzi, B.; Fontana, L. Health Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Metabolic and Molecular Mechanisms. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2018, 73, 318–326. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, Greenlund K, Daniels S, Nichol G, Tomaselli GF, Arnett DK, Fonarow GC, Ho PM, Lauer MS, Masoudi FA, Robertson RM, Roger V, Schwamm LH, Sorlie P, Yancy CW, Rosamond WD. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 2010;121(4):586-613.

- Petermann-Rocha, F.; Parra-Soto, S.; Gray, S.; Anderson, J.; Welsh, P.; Gill, J.; Sattar, N.; Ho, F.K.; Celis-Morales, C.; Pell, J.P. Vegetarians, fish, poultry, and meat-eaters: who has higher risk of cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality? A prospective study from UK Biobank. Eur. Hear. J. 2021, 42, 1136–1143. [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.Y.N.; Appleby, P.N.; Bradbury, K.E.; Perez-Cornago, A.; Travis, R.C.; Clarke, R.; Key, T.J. Risks of ischaemic heart disease and stroke in meat eaters, fish eaters, and vegetarians over 18 years of follow-up: results from the prospective EPIC-Oxford study. BMJ 2019, 366, l4897. [CrossRef]

- Appleby PN, Crowe FL, Bradbury KE, Travis RC, Key TJ. Mortality in vegetarians and comparable nonvegetarians in the United Kingdom. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103(1):218-30.

- Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Spencer, E.A.; Travis, R.C.; Roddam, A.W.; Allen, N.E. Mortality in British vegetarians: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1613S–1619S. [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Spiegelman, D.; Chiuve, S.E.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.; Rexrode, K.M.; Rimm, E.B.; Hu, F.B. Healthful and Unhealthful Plant-Based Diets and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in U.S. Adults. Circ. 2017, 70, 411–422. [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Chiuve, S.E.; Borgi, L.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B. Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women: Results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. PLOS Med. 2016, 13, e1002039. [CrossRef]

- Bycroft, C.; Freeman, C.; Petkova, D.; Band, G.; Elliott, L.T.; Sharp, K.; Motyer, A.; Vukcevic, D.; Delaneau, O.; O’connell, J.; et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature 2018, 562, 203–209. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Young, H.; Crowe, F.L.; Benson, V.S.; A Spencer, E.; Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Beral, V. Development and evaluation of the Oxford WebQ, a low-cost, web-based method for assessment of previous 24 h dietary intakes in large-scale prospective studies. Public Health Nutr 2011, 14, 1998–2005. [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, K.E.; Young, H.J.; Guo, W.; Key, T.J. Dietary assessment in UK Biobank: an evaluation of the performance of the touchscreen dietary questionnaire. J. Nutr. Sci. 2018, 7, e6. [CrossRef]

- A Martínez-González, M.; Sánchez-Tainta, A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ros, E.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E.; Fiol, M.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M.; Schröder, H.; et al. A provegetarian food pattern and reduction in total mortality in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 320S–328S. [CrossRef]

- Marchese, L.E.; McNaughton, S.A.; Hendrie, G.A.; Wingrove, K.; Dickinson, K.M.; Livingstone, K.M. A scoping review of approaches used to develop plant-based diet quality indices. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2023, 7, 100061. [CrossRef]

- Nutritools. Strengths and Weaknesses of Dietary Assessment Tools (DATs). https://www.nutritools.org/strengths-and-weaknesses.

- Keaver, L.; Ruan, M.; Chen, F.; Du, M.; Ding, C.; Wang, J.; Shan, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhang, F.F. Plant- and animal-based diet quality and mortality among US adults: a cohort study. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 125, 1405–1415. [CrossRef]

- Caivano, S.; Colugnati, F.A.B.; Domene, S.M.Á. Diet Quality Index associated with Digital Food Guide: update and validation. Cad. de Saude publica 2019, 35, e00043419. [CrossRef]

- Bromage, S.; Batis, C.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Fawzi, W.W.; Fung, T.T.; Li, Y.; Deitchler, M.; Angulo, E.; Birk, N.; Castellanos-Gutiérrez, A.; et al. Development and Validation of a Novel Food-Based Global Diet Quality Score (GDQS). J. Nutr. 2021, 151, 75S–92S. [CrossRef]

- American Heart Association Inc. Available online: http://www.heart.org/ (accessed on May 2020).

- Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, Chapman MJ, De Backer GG, Delgado V, Ference BA, Graham IM, Halliday A, Landmesser U, Mihaylova B, Pedersen TR, Riccardi G, Richter DJ, Sabatine MS, Taskinen M-R, Tokgozoglu L, Wiklund O, Group ESD. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk: The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). European Heart Journal 2019;41(1):111-188.

- Heart Foundation. Nutrition Position Statements. https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/bundles/for-professionals/nutrition-position-statements.

- Satija, A.; Bhupathiraju, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Spiegelman, D.; Chiuve, S.E.; Borgi, L.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F.B. Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women: Results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. PLOS Med. 2016, 13, e1002039. [CrossRef]

- Micha, R.; Shulkin, M.L.; Peñalvo, J.L.; Khatibzadeh, S.; Singh, G.M.; Rao, M.; Fahimi, S.; Powles, J.; Mozaffarian, D. Etiologic effects and optimal intakes of foods and nutrients for risk of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses from the Nutrition and Chronic Diseases Expert Group (NutriCoDE). PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0175149. [CrossRef]

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Himmelfarb CD, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA, Williamson JD, Wright JT. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 2018;71(6):e13-e115.

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; de Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 139, E1046–E1081. [CrossRef]

- NHS. The Eatwell Guide. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/food-guidelines-and-food-labels/the-eatwell-guide/ (29th Nov 2022; date last accessed).

- Tan, M.S.; Cheung, H.C.; McAuley, E.; Ross, L.J.; MacLaughlin, H.L. Quality and validity of diet quality indices for use in Australian contexts: a systematic review. Br. J. Nutr. 2021, 128, 2021–2045. [CrossRef]

- Chamoli, R.; Jain, M.; Tyagi, G. Reliability and Validity of the Diet Quality Index for 7–9-year-old Indian Children. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2019, 22, 554–564. [CrossRef]

- Bolland, M.J.; Barber, A.; Doughty, R.N.; Grey, A.; Gamble, G.; Reid, I.R. Differences between self-reported and verified adverse cardiovascular events in a randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002334. [CrossRef]

- Machón, M.; Arriola, L.; Larrañaga, N.; Amiano, P.; Moreno-Iribas, C.; Agudo, A.; Ardanaz, E.; Barricarte, A.; Buckland, G.; Chirlaque, M.; et al. Validity of self-reported prevalent cases of stroke and acute myocardial infarction in the Spanish cohort of the EPIC study. J. Epidemiology Community Heal. 2012, 67, 71–75. [CrossRef]

- Okura, Y.; Urban, L.H.; Mahoney, D.W.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Rodeheffer, R.J. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J. Clin. Epidemiology 2004, 57, 1096–1103. [CrossRef]

- Eliassen, B.-M.; Melhus, M.; Tell, G.S.; Borch, K.B.; Braaten, T.; Broderstad, A.R.; Graff-Iversen, S. Validity of self-reported myocardial infarction and stroke in regions with Sami and Norwegian populations: the SAMINOR 1 Survey and the CVDNOR project. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e012717. [CrossRef]

- Darke, P.; Cassidy, S.; Catt, M.; Taylor, R.; Missier, P.; Bacardit, J. Curating a longitudinal research resource using linked primary care EHR data—a UK Biobank case study. J. Am. Med Informatics Assoc. 2021, 29, 546–552. [CrossRef]

- Pastorino, S.; Richards, M.; Hardy, R.; Abington, J.; Wills, A.; Kuh, D.; Pierce, M. Validation of self-reported diagnosis of diabetes in the 1946 British birth cohort. Prim. Care Diabetes 2014, 9, 397–400. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A.L.C.; Pankow, J.S.; Heiss, G.; Selvin, E. Validity and Reliability of Self-reported Diabetes in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am. J. Epidemiology 2012, 176, 738–743. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.M.R.; DeFor, T.A.; Crain, A.L.; Kerby, T.J.M.; Strayer, L.S.M.; Lewis, C.E.M.; Whitlock, E.P.; Williams, S.B.; Vitolins, M.Z.D.; Rodabough, R.J.; et al. Validity of diabetes self-reports in the Women’s Health Initiative. Menopause 2014, 21, 861–868. [CrossRef]

- Moradpour, F.; Piri, N.; Dehghanbanadaki, H.; Moradi, G.; Fotouk-Kiai, M.; Moradi, Y. Socio-demographic correlates of diabetes self-reporting validity: a study on the adult Kurdish population. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shen, J.; Xuan, J.; Zhu, A.; Ji, J.S.; Liu, X.; Cao, Y.; Zong, G.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, X.; et al. Plant-based dietary patterns in relation to mortality among older adults in China. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 224–230. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Giovannucci, E.L. Plant-based diet quality and the risk of total and disease-specific mortality: A population-based prospective study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5718–5725. [CrossRef]

- Heianza, Y.; Zhou, T.; Sun, D.; Hu, F.B.; Qi, L. Healthful plant-based dietary patterns, genetic risk of obesity, and cardiovascular risk in the UK biobank study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4694–4701. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 779–798. [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, K.M.; Abbott, G.; Bowe, S.J.; Ward, J.; Milte, C.; A McNaughton, S. Diet quality indices, genetic risk and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: a longitudinal analysis of 77 004 UK Biobank participants. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045362. [CrossRef]

- Sacks, F.M.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Wu, J.H.Y.; Appel, L.J.; Creager, M.A.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Miller, M.; Rimm, E.B.; Rudel, L.L.; Robinson, J.G.; et al. Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 136, e1–e23. [CrossRef]

- Mensink, R.P.; Zock, P.L.; Kester, A.D.; Katan, M.B. Effects of dietary fatty acids and carbohydrates on the ratio of serum total to HDL cholesterol and on serum lipids and apolipoproteins: a meta-analysis of 60 controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 77, 1146–1155. [CrossRef]

- AbuMweis, S.S.; Barake, R.; Jones, P. Plant sterols/stanols as cholesterol lowering agents: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Food Nutr. Res. 2008, 52. [CrossRef]

- Theuwissen, E.; Mensink, R.P. Water-soluble dietary fibers and cardiovascular disease. Physiol. Behav. 2008, 94, 285–292. [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Canfora, E.E.; Blaak, E.E. Gastrointestinal Transit Time, Glucose Homeostasis and Metabolic Health: Modulation by Dietary Fibers. Nutrients 2018, 10, 275. [CrossRef]

- Bjerregaard, L.J.; Joensen, A.M.; Dethlefsen, C.; Jensen, M.K.; Johnsen, S.P.; Tjønneland, A.; Rasmussen, L.H.; Overvad, K.; Schmidt, E.B. Fish intake and acute coronary syndrome. Eur. Hear. J. 2009, 31, 29–34. [CrossRef]

- Strøm M, Halldorsson TI, Mortensen EL, Torp-Pedersen C, Olsen SF. Fish, n-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular diseases in women of reproductive age: A prospective study in a large national cohort. Hypertension 2012;59(1):36-43.

- Karusheva, Y.; Koessler, T.; Strassburger, K.; Markgraf, D.; Mastrototaro, L.; Jelenik, T.; Simon, M.-C.; Pesta, D.; Zaharia, O.-P.; Bódis, K.; et al. Short-term dietary reduction of branched-chain amino acids reduces meal-induced insulin secretion and modifies microbiome composition in type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled crossover trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 110, 1098–1107. [CrossRef]

- Theuwissen, E.; Mensink, R.P. Water-soluble dietary fibers and cardiovascular disease. Physiol. Behav. 2008, 94, 285–292. [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Canfora, E.E.; Blaak, E.E. Gastrointestinal Transit Time, Glucose Homeostasis and Metabolic Health: Modulation by Dietary Fibers. Nutrients 2018, 10, 275. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, C.; Yoruk, A.; Wang, L.; Gaziano, J.M.; Sesso, H.D. Fish and omega-3 fatty acid consumption and risk of hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2019, 37, 1223–1229. [CrossRef]

| FOOD GROUPS | FOOD ITEMS | SCORING |

|---|---|---|

| Wholegrains (14 items) | Porridge, muesli, oat crunch, bran cereal, non-white bread (flour types, brown, wholemeal, other type), seeded or other bread, crispbread, whole-wheat cereal, other cereal, oatcakes, wholemeal pasta, brown rice, couscous, other cooked grains (such as bulgur). | + |

| Fruits (20 items) | Avocado, mixed fruit, apple, banana, berries, cherries, grapefruit, grapes, mango, melon, orange, orange-like small fruits (such as satsuma), peach/nectarine, pear, pineapple, plum, other fruits, stewed/cooked fruit, prunes, other dried fruit | + |

| Non-starchy Vegetables (26 items) | Mixed vegetables, vegetable pieces, coleslaw, side salad, beetroot, broccoli, cabbage/kale, carrots, cauliflower, celery, courgette, cucumber, garlic, leeks, lettuce, mushrooms, onion, parsnip, sweet peppers, spinach, sprouts, fresh tomatoes, cooked or tinned tomatoes, turnip/swede, watercress, other vegetable intake | + |

| Starchy Vegetables (3 items) | Butternut squash, sweetcorn, sweet potato | + |

| Nuts & Seeds (5 items) | Unsalted peanuts, unsalted nuts, seeds, salted peanuts, salted nuts | + |

| Legumes & Beans, Other Vegetarian Protein Alternatives (9 items) | Beans (baked beans), other beans or lentils (pulses), broad beans, green beans, peas, vegetarian sausages/burgers, tofu, quorn, other vegetarian alternative | + |

| Uncoated Fish & Seafood (7 items) | Tinned tuna, oily fish, white fish, prawns, lobster/crab, shellfish, other fish intake | + |

| Eggs (5 items) | Whole eggs, omelettes or scrambled egg, eggs in sandwiches, scotch egg, other egg dishes | + |

| (Reduced-fat and/or No Added Sugar) Milk & Dairy Products (4 items) | Milk, low fat hard cheese, low fat cheese spread, cottage cheese | + |

| Tea, Coffee & Other Low-calorie Drinks (11 items) | Instant coffee, filtered coffee, cappuccino, latte, espresso, other coffee drinks, standard tea, rooibos tea, green tea, herbal tea, other tea | + |

| Homemade soup (1 item) | Homemade soup | + |

| Refined grains & cereals, including discretionary choices (12 items) | Sweetened cereal, plain cereal, white sliced bread, white bread, white bap, white bread roll, naan bread, garlic bread, white pasta, white rice, pancake, snackpot | - |

| Potatoes (4 items) | Fried potatoes, boiled/baked potatoes, mashed potatoes, crisps (e.g., potato chips) | - |

| Meat, Poultry & Processed Meat (10 items) | Sausage, beef, pork, lamb, crumbed or deep-fried poultry, poultry, bacon, ham, liver, other meat intake | - |

| Coated Fish & Seafood (2 items) | Breaded fish, battered fish | - |

| (Full-fat and/or Added Sugar) Milk & Dairy Products (10 items) | Flavored milk, yogurt, hard cheese, soft cheese, blue cheese, cheese spread, feta cheese, mozzarella cheese, goat's cheese, other cheese | - |

| Processed Soup (2 items) | Powdered/instant soup intake, canned soup intake | - |

| Sugar, Sweets & Desserts, Cookies & Pastries (23 items) | Intake of sugar added to coffee/tea/cereal, ice-cream, milk-based pudding, other milk-based pudding, soya dessert, fruitcake, cake, doughnuts, sponge pudding, cheesecake, other dessert, chocolate bar, white chocolate, milk chocolate, dark chocolate, chocolate-covered raisin, chocolate sweet, diet sweets, chocolate-covered biscuits, chocolate biscuits, sweet biscuits, cereal bar, other sweets | - |

| Savoury Snacks (2 items) | Savoury or cheesy biscuits, other savoury snack | - |

| Sugary Drinks including Juices & Sugar-sweetened Beverages (3 items) | Low-calorie hot chocolate, hot chocolate, other non-alcoholic drink | - |

| Artificial sweetener (1 item) | Artificial sweetener added to coffee/tea/cereal | - |

| Unhealthy Fat (with/without Carbohydrates) (2 items) | Butter/margarine on bread/crackers (spreadable, low fat, normal fat, or unknown type), number of bread slices/baps/bread rolls/crackers/crispbreads/oatcakes/other bread types with butter/margarine | - |

| Q1 (n=48453) | Q2 (n=47778) | Q3 (n=48012) | Q4 (n=48031) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart-protective diet score | -6.8 (3.6) | 0.3 (1.5) | 5.2 (1.5) | 12.5 (3.8) |

| Age at recruitment, year | 55.3 (8.2) | 56.1 (8.0) | 56.7 (7.8) | 57.0 (7.6) |

| Sex, male | 26619 [54.9] | 21435 [44.9] | 18965 [39.5] | 16283 [33.9] |

| Ethnicity, White | 46212 [95.4] | 45654 [95.6] | 45977 [95.8] | 45877 [95.5] |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 26818 [55.3] | 27386 [57.3] | 28022 [58.4] | 28192 [58.7] |

| Former | 16313 [33.7] | 16460 [34.5] | 16710 [34.8] | 17000 [35.4] |

| Current | 5195 [10.7] | 3806 [8.0] | 3176 [6.6] | 2724 [5.7] |

| Missing | 127 [0.3] | 126 [0.3] | 104 [0.2] | 115 [0.2] |

| Townsend deprivation index | -1.5 (3.0) | -1.7 (2.9) | -1.7 (2.8) | -1.6 (2.9) |

| College or university degree, Y | 16714 [34.5] | 20026 [41.9] | 22205 [46.2] | 24424 [50.9] |

| Average total household income before tax | ||||

| < £18000 | 7119 [14.7] | 6302 [13.2] | 5923 [12.3] | 6017 [12.5] |

| £18000-30999 | 10740 [22.2] | 10239 [21.4] | 10220 [21.3] | 10192 [21.2] |

| £31000- £51999 | 12937 [26.7] | 12195 [25.5] | 12374 [25.8] | 12173 [25.3] |

| £52000-100000 | 10168 [21] | 10913 [22.8] | 11097 [23.1] | 11091 [23.1] |

| > £100000 | 2521 [5.2] | 3270 [6.8] | 3397 [7.1] | 3624 [7.5] |

| Physical activity score | ||||

| Low | 5965 [12.3] | 5437 [11.4] | 4660 [9.7] | 3910 [8.1] |

| Moderate | 19019 [39.3] | 19082 [39.9] | 19205 [40.0] | 18453 [38.4] |

| High | 14387 [29.7] | 14756 [30.9] | 15917 [33.2] | 18126 [37.7] |

| Sitting score (hours/day) | 5.2 (2.5) | 4.8 (2.3) | 4.6 (2.2) | 4.3 (2.2) |

| Sleep score [range: 0-5] | 3.6 (1.0) | 3.7 (1.0) | 3.7 (1.0) | 3.8 (1.0) |

| Dietary supplement use, yes | 22261 (45.9) | 24244 (50.7) | 25842 (53.8) | 27855 (58.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.5 (4.8) | 27.0 (4.6) | 26.6 (4.4) | 26.2 (4.5) |

| SBP, mmHg | 137.1 (17.9) | 136.6 (18.3) | 136.5 (18.4) | 136.1 (18.6) |

| DBP, mmHg | 82.6 (10.0) | 82.0 (10.0) | 81.6 (10.0) | 81.2 (10.0) |

| TC, mmol/L | 5.7 (1.1) | 5.8 (1.1) | 5.8 (1.1) | 5.8 (1.1) |

| LDL-C, mmol/L | 3.6 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.8) | 3.6 (0.8) |

| HDL-C, mmol/L | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.4) |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.8 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.6 (1.0) | 1.6 (0.9) |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 35.6 (6.1) | 35.4 (5.9) | 35.3 (5.8) | 35.3 (5.5) |

| Quartiles | Q1 (n=48453) | Q2 (n=47778) | Q3 (n=48012) | Q4 (n=48031) |

| Heart-protective diet score | -6.8 (3.6) | 0.3 (1.5) | 5.2 (1.5) | 12.5 (3.8) |

| Food groups intake (grams/week) | ||||

| Wholegrains (1 serve: 60g) | 76.2 (98.8) | 116.2 (107.5) | 142.9 (110) | 176.6 (117.1) |

| Fruits (1 serve: 80g) | 70.6 (100.9) | 120.9 (127.7) | 174.4 (145.5) | 262.7 (173.6) |

| Non-starchy Vegetables (1 serve: 80g) |

102.7 (132.8) | 156.6 (162.9) | 211.1 (185) | 311.3 (228.7) |

| Starchy Vegetables (1 serve: 75g) |

1.2 (8.7) | 2.5 (13) | 4.4 (17.2) | 10.7 (27.7) |

| Nuts & Seeds (1 serve: 30g) | 1.9 (8.2) | 3.2 (11.2) | 4.8 (13.6) | 9.3 (19.5) |

| Legumes & Beans, Other Vegetarian Protein Alternatives (1 serve: 80g) | 15 (34.7) | 23.7 (43.8) | 32.8 (50.6) | 54.7 (66.1) |

| Uncoated Fish & Seafood (1 serve: 140g) |

14 (46.6) | 27.8 (63.2) | 43 (76.6) | 72.7 (95.5) |

| Eggs (1 serve: 120g) | 23.6 (59.9) | 29.8 (67.4) | 34.5 (72.1) | 47.7 (84.7) |

| (Reduced-fat and/or No Added Sugar) Milk & Dairy Products (1 serve: 250ml) | 17.2 (76.3) | 23.5 (85.2) | 32.5 (100.0) | 52.8 (127.8) |

| Tea, Coffee & Other Low-calorie Drinks (1 serve: 250ml) |

345.2 (476.6) | 506.2 (517.4) | 611.1 (525) | 781.8 (548.8) |

| Homemade soup (1 serve: 250ml) |

8.6 (48.1) | 16.8 (66.8) | 25.9 (83.6) | 46.5 (112.1) |

| Refined grains & cereals, including discretionary choices (1 serve: 60g) | 114.6 (101.5) | 60.7 (76.1) | 39.5 (60.1) | 23.5 (43.7) |

| Potatoes (1 serve: 75g) | 66.4 (64.5) | 55.3 (56.5) | 49 (52.0) | 39 (45.9) |

| Meat, Poultry & Processed Meat (1 serve: 70g) | 109.6 (91.7) | 85.9 (79.7) | 70.4 (71.4) | 49.1 (62.9) |

| Coated Fish & Seafood (1 serve: 140g) |

5.6 (24.1) | 3.9 (18.9) | 2.7 (15.7) | 1.4 (11.0) |

| (Full-fat and/or Added Sugar) Milk & Dairy Products (1 serve: 250ml) | 329.4 (302.7) | 296.2 (288.1) | 285.1 (282) | 268.8 (267.2) |

| Processed Soup (1 serve: 250ml) |

27.1 (82.4) | 20.3 (70.9) | 16.4 (63.9) | 11.3 (53.1) |

| Sugar, Sweets & Desserts, Cookies & Pastries (1 serve: 40g) |

80.4 (79.5) | 52.4 (63.6) | 38.5 (54.1) | 24.5 (42) |

| Savoury Snacks (1 serve: 30g) |

2.2 (9.1) | 1.4 (6.9) | 1.1 (5.9) | 0.8 (4.9) |

| Sugary Drinks including Juices & Sugar-sweetened Beverages (1 serve: 150ml) |

21.1 (70.1) | 14.6 (56.3) | 12.3 (50.7) | 9.0 (44.5) |

| Artificial sweeteners (1 serve: 4g) |

1.4 (3.7) | 0.9 (2.9) | 0.6 (2.4) | 0.4 (1.9) |

| Unhealthy Fat (with/without Carbohydrates) (1 serve: 10g) |

6.3 (11) | 4.2 (9.1) | 3.1 (7.9) | 2.0 (6.7) |

| Daily nutrient intake | ||||

| Total energy intake, kcal/d | 2187.3 (631.4) | 2016.4 (604.0) | 1970.7 (580.6) | 1991.6 (578.6) |

| Total protein, g/d | 81.6 (28.0) | 78.4 (26.3) | 78.4 (25.3) | 81.9 (26.2) |

| Total fat, g/d | 79.4 (31.0) | 71.2 (29.8) | 68.5 (29.1) | 68.8 (30.2) |

| Saturated fatty acids, g/d | 31.2 (13.8) | 27.1 (12.6) | 25.0 (12.0) | 23.0 (11.6) |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids, g/d | 28.7 (11.8) | 25.6 (11.5) | 24.7 (11.4) | 25.3 (12.3) |

| n-3 fatty acids, g/d | 1.8 (0.9) | 1.8 (1.0) | 1.9 (1.1) | 2.3 (1.4) |

| n-6 fatty acids, g/d | 10.8 (5.3) | 10.3 (5.4) | 10.5 (5.7) | 11.7 (6.5) |

| Total carbohydrate, g/d | 269.7 (85.4) | 247.6 (81.9) | 244.1 (80.0) | 249.3 (80.6) |

| Total sugars, g/d | 125.1 (54.1) | 119.4 (50.9) | 122.3 (50.2) | 132.1 (52.2) |

| Dietary fibre, g/d | 14.6 (5.9) | 16.3 (6.3) | 18.3 (6.5) | 22.3 (7.7) |

| Alcohol, g/d | 18.0 (26.2) | 17.7 (24.9) | 16.5 (23.1) | 14.42 (21.4) |

| Vitamin C, mg/d | 96.8 (71.1) | 115.7 (77.9) | 134.8 (83.4) | 169.8 (97.5) |

| Vitamin E, mg/d | 10.5 (5.0) | 10.17 (4.9) | 10.65 (4.9) | 12.3 (5.2) |

| Vitamin B12, ug/d | 5.7 (3.7) | 5.80 (3.7) | 6.1 (3.8) | 6.9 (4.2) |

| Folate, ug/d | 277.0 (107.3) | 292.7 (110.0) | 315.5 (110.4) | 364.1 (122.7) |

| Beta carotene, ug/d | 1727.4 (2089.6) | 2239.4 (2445.7) | 2760.2 (2724.9) | 3937.7 (3566.4) |

| Iron, mg/d | 11.7 (4.0) | 11.8 (4.0) | 12.2 (4.0) | 13.5 (4.3) |

| Zinc, mg/d | 9.8 (4.0) | 9.5 (3.7) | 9.5 (3.5) | 9.8 (3.5) |

| Magnesium, mg/d | 299.9 (90.3) | 313.3 (92.5) | 333.8 (93.5) | 379.5 (106.4) |

| Iodine, ug/d | 203.8 (109.3) | 201.9 (111.5) | 207.9 (119.6) | 224.2 (135.7) |

| Sodium, mg/d | 2158.5 (912.8) | 1895.3 (845.3) | 1814.8 (810.0) | 1843.1 (820.2) |

| Potassium, mg/d | 3342.3 (1099.5) | 3478.5 (1100.8) | 3686.0 (1088.8) | 4128.9 (1157.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).