Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

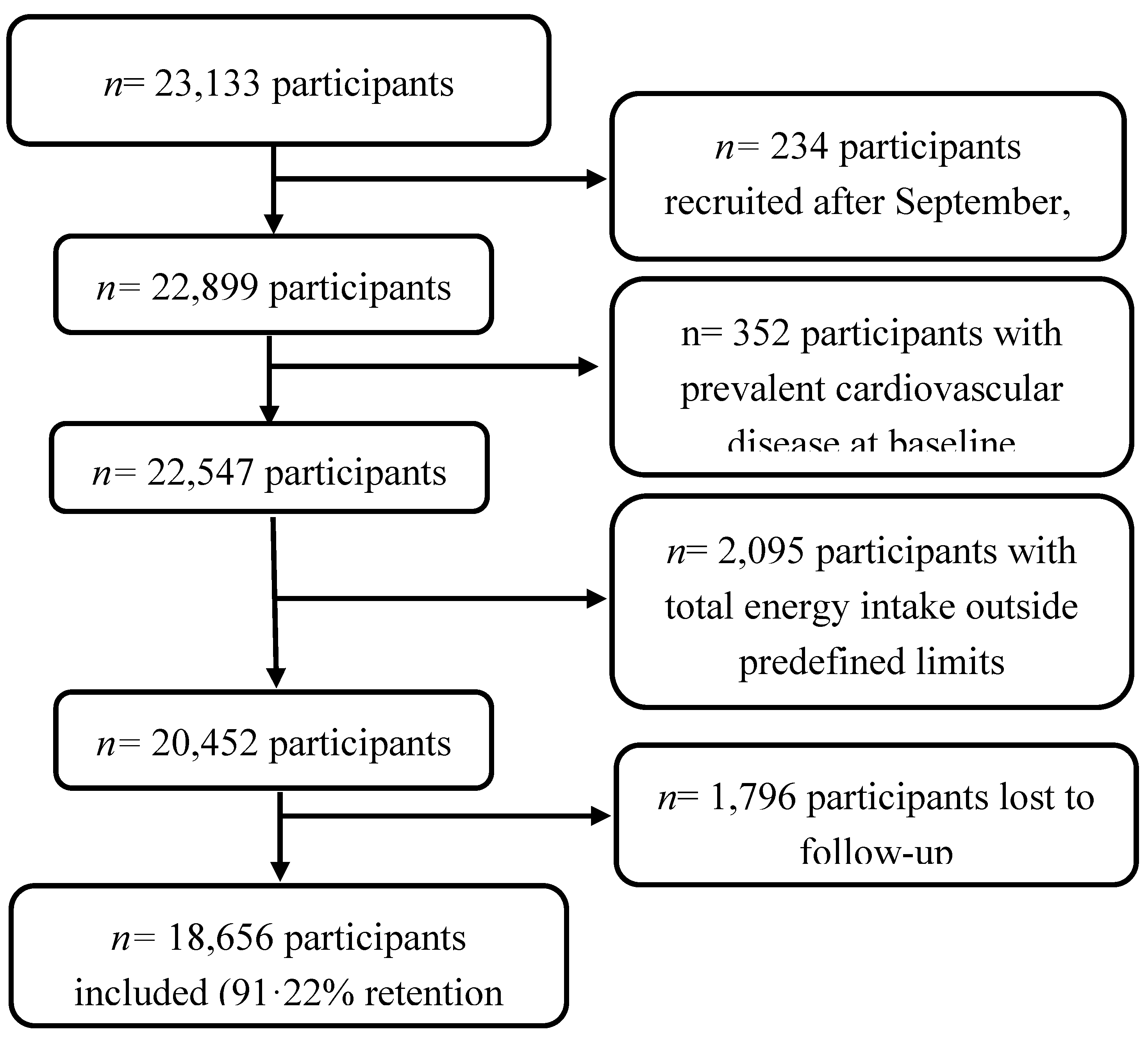

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Dietary Assessment

2.3. Planetary Health Diet Assessment

2.4. Assessment of Other Dietary Variables

2.5. Ascertainment of CVD

2.6. Co-Variables Evaluation

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Participants

3.2. Association Between Planetary Health Diet and CVD

3.3. Correlation Between Planetary Health Diet and Mediterranean Diet

3.4. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Food components Planetary Health Diet Index1 | Target intake (reference interval)2 | 3 points | 2 points | 1 point | 0 points | Scoring criteria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emphasized intake | Vegetables | 300 (200-600) | >300 | 200-300 | 100-200 | <100 | Positive score: 3 points = intake above the target 2 points = lower limit of the reference interval up to the target intake 1 point = 50%-100% of the lower limit of the reference interval 0 points <50% of the lower limit of the reference interval |

| Fruits | 200 (100-300) | >200 | 100-200 | 50-100 | <50 | ||

| Unsaturated oils | 40 (20-80) | >40 | 20-40 | 10-20 | <10 | ||

| Legumes | 75 (0-150) | >75 | 37.5-75 | 18.75-37.5 | <18.75 | Positive score, adjusted3: 3 points = intake above the target 2 points = 50%-100% of the target intake 1 point = 25%-50% of the target intake 0 points = <25% of the target intake |

|

| Nuts | 50 (0-100) | >50 | 25-50 | 12.5-25 | <12.5 | ||

| Whole grains | 232 | >232 | 116-232 | 58-116 | <58 | ||

| Fish | 28 (0-100) | >28 | 14-28 | 7-14 | <7 | ||

| Limited intake | Beef and lamb | 7 (0-14) | <7 | 7-14 | 14-28 | >28 | Inverse score: 3 points = intake below the target 2 points = between the target intake and the upper limit of the reference interval 1 point = 100%-200% of the upper limit of the reference interval 0 points >= 200% of the upper limit of the reference interval |

| Pork | 7 (0-14) | <7 | 7-14 | 14-28 | >28 | ||

| Poultry | 29 (0-58) | <29 | 29-58 | 58-116 | >116 | ||

| Eggs | 13 (0-25) | <13 | 13-25 | 25-50 | >50 | ||

| Dairy | 250 (0-500) | <250 | 250-500 | 500-1000 | >1000 | ||

| Potatoes | 50 (0-100) | <50 | 50-100 | 100-200 | >200 | ||

| Added sugar4 | 31 (0-31) | <31 | 31-62 | 62-124 | >124 | ||

|

1Food components are based on the Planetary Health Diet as grams per day [12]. 2Target and reference values from the EAT-Lancet diet [12] based on an energy intake of 2500 kcal/day, expressed in grams. 3The initial criteria of the positive score were not feasible, since the lower limit of the reference interval was 0. 4Since the upper limit of the reference Interval and target were identical, we used an upper reference interval of target intake x2 (62 g) [13]. | |||||||

References

- Berthy, F.; Brunin, J.; Allès, B.; Fezeu, LK.; Touvier, M.; Hercberg, S. Association between adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet and risk of cancer and cardiovascular outcomes in the prospective NutriNet-Sante cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 2022, 116, 980–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawicki, CM.; Ramesh, G.; Bui, L.; Nair, NK.; Hu, FB.; Rimm, EB. Planetary health diet and cardiovascular disease: Results from three large prospective cohort studies in the USA. Lancet 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, CW.; Aday, AW.; Almarzooq, ZI.; Alonso, A.; Beaton, AZ.; Bittencourt, MS. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, E153–639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Spain-Overview of the distribution of causes of total deaths grouped by category. 2021. Available online: https://platform.who.int/mortality/countries/country-details/MDB/spain.

- Arnett, DK.; Blumenthal, RS.; Albert, MA.; Buroker, AB.; Goldberger, ZD.; Hahn, EJ. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 140, e596–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M. Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health. Nature 2014, 515, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray CJL.; Aravkin AY. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1223–1249. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Caulfield, LE.; Garcia-Larsen, V.; Steffen, LM.; Coresh, J.; Rebholz, CM. Plant-Based Diets Are Associated With a Lower Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Disease, Cardiovascular Disease Mortality, and All-Cause Mortality in a General Population of Middle-Aged Adults. J Am Heart Assoc 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heianza, Y.; Zhou, T.; Sun, D.; Hu, FB.; Qi, L. Healthful plant-based dietary patterns, genetic risk of obesity, and cardiovascular risk in the UK biobank study. Clin Nutr 2021, 40, 4694–4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D. Plant Foods, Antioxidant Biomarkers, and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mortality: A Review of the Evidence. Adv Nutr 2019, 10, S404–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarova S, V.; Sutherland, JM. Adherence to emerging plant-based dietary patterns and its association with cardiovascular disease risk in a nationally representative sample of Canadian adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2022, 116, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stubbendorff, A.; Sonestedt, E.; Ramne, S.; Drake, I.; Hallström, E.; Ericson, U. Development of an EAT-Lancet index and its relation to mortality in a Swedish population. Am J Clin Nutr 2022, 115, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springmann, M.; Spajic, L.; Clark, MA.; Poore, J.; Herforth, A.; Webb, P. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: Modelling study. The BMJ 2020, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Marken, I.; Stubbendorff, A.; Ericson, U.; Qi, L.; Sonestedt, E. The EAT-Lancet Diet Index, Plasma Proteins, and Risk of Heart Failure in a Population-Based Cohort. JACC Heart Fail 2024, 12, 1197–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotos-Prieto, M.; Ortolá, R. Association between planetary health diet and cardiovascular disease: A prospective study from the UK Biobank. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataei-Kachouei, A.; Mohammadifard, N. Adherence to EAT-Lancet reference diet and risk of premature coronary artery diseases: A multi-center case-control study. Eur J Nutr 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colizzi, C.; Harbers, MC.; Vellinga, RE.; Monique, WM.; Boer, JM.; Biesbroek, S. Adherence to the EAT-Lancet Healthy Reference Diet in Relation to Risk of Cardiovascular Events and Environmental Impact: Results From the EPIC-NL Cohort. J Am Heart Assoc 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacau, LT.; Benseñor, IM. Adherence to the EAT-Lancet sustainable reference diet and cardiometabolic risk profile: Cross-sectional results from the ELSA-Brasil cohort study. Eur J Nutr 2023, 62, 807–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Dukuzimana, J.; Stubbendorff, A.; Ericson, U.; Borné, Y.; Sonestedt, E. Adherence to the EAT-Lancet diet and risk of coronary events in the Malmö Diet and Cancer cohort study. Am J Clin Nutr 2023, 117, 903–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuppel, A.; Papier, K.; Key, TJ.; Travis, RC. EAT-Lancet score and major health outcomes: The EPIC-Oxford study. Lancet 2019, 394, 213–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, YX.; Chen, JX. Adherence to a planetary health diet, genetic susceptibility, and incident cardiovascular disease: A prospective cohort study from the UK Biobank. Am J Clinical Nutr 2024, 120, 648–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karavasiloglou, N.; Thompson, AS.; Pestoni, G.; Knuppel, A.; Papier, K.; Cassidy, A. Adherence to the EAT-Lancet reference diet is associated with a reduced risk of incident cancer and all-cause mortality in UK adults. One Earth 2023, 6, 1726–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacau, LT.; Hanley-Cook, GT. Relative validity of the Planetary Health Diet Index by comparison with usual nutrient intakes, plasma food consumption biomarkers, and adherence to the Mediterranean diet among European adolescents: The HELENA study. Eur J Nutr 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seguí-Gómez, M.; de la Fuente, C. Cohort profile: The “Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra” (SUN) study. Int J Epidemiol 2006, 35, 1417–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willet, WC. Nutritional epidemiology. 3rd ed. NewYork, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Ballart, JD.; Piñol, JL.; Zazpe, I.; Corella, D.; Carrasco, P.; Toledo, E. Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br J Nutr 2010, 103, 1808–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-moreno, JM.; Boyle, P.; Gorgojo, L.; Maisonneuve, P.; Fernandez-rodriguez, JC.; Salvini, S. Development and validation of a food frequency questionnaire in Spain. Int J Epidemiol 1993, 22, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataix Verdu, J. Tabla de Composición de Alimentos Españoles (Spanish Food Composition Tables). 4th ed. Granada: Universidad de Granada 2003.

- Moreiras, O.; Carbajal, Á.; Cabrera, L.; Cuadrado, C. Tablas de Composición de Alimentos (Food Composition Tables). 9th ed. Pirámide, Madrid 2005.

- Trichopoulou, A. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. Vascular Medicine 2004, 9, 145–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H.; Fitó, M.; Estruch, R.; Martínez-González, MA.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J. A Short screener is valid for assessing mediterranean diet adherence among older spanish men and women. J Nutr 2011, 141, 1140–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thygesen, K.; Alpert, JS.; Jaffe, AS.; Simoons, ML.; Chaitman, BR.; White, HD. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2012, 33, 2551–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Pérez Valdivieso, JR.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Alonso, Á.; Martínez-González, MA. Validación del peso e índice de masa corporal auto-declarados de los participantes de una cohorte de graduados universitarios. [Validation of self-reported weight and body mass index in a cohort of university graduates]. Rev Esp Obes 2005, 3, 352–358. [Google Scholar]

- Vanegas, P.; Zazpe, I.; Santiago, S.; Fernandez-Lazaro, CI.; de la O, V. ; Martínez-González MÁ. Macronutrient quality index and cardiovascular disease risk in the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra (SUN) cohort. Eur J Nutr, 2022; 61, 3517–3530. [Google Scholar]

- de la O, V.; Zazpe, I.; Goni, L.; Santiago, S.; Martín-Calvo, N.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. A score appraising Paleolithic diet and the risk of cardiovascular disease in a Mediterranean prospective cohort. Eur J Nutr 2022, 61, 957–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quek, J.; Lim, G.; Lim, WH.; Ng, CH.; So, WZ.; Toh, J. The Association of Plant-Based Diet With Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Prospect Cohort Studies. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, ZH.; Cheong, HC.; Tu, YK.; Kuo, PH. Association between plant-based dietary patterns and risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutrients MDPI 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehin, S.; Rasmussen, P.; Mai, S.; Mushtaq, M.; Agarwal, M.; Hasan, SM. Plant Based Diet and Its Effect on Cardiovascular Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health MDPI 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, G.; Kehoe, L.; Flynn, A.; Walton, J. Plant-based diets: A review of the definitions and nutritional role in the adult diet. Proc Nutr Soc 2022, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Samtiya, M.; Dhewa, T.; Mishra, V.; Aluko, RE. Health benefits of polyphenols: A concise review. J Food Biochem 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, EA.; McKay, S. The role of specific components of a plant-based diet in management of dyslipidemia and the impact on cardiovascular risk. Nutrients MDPI 2020, 12, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estruch, R.; Ros, E.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Covas, MI.; Corella, D.; Arós, F. Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease with a Mediterranean Diet Supplemented with Extra-Virgin Olive Oil or Nuts. New Engl J Med 2018, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, I.; Wilairatana, P.; Saqib, F.; Nasir, B.; Wahid, M.; Latif, MF. Plant Polyphenols and Their Potential Benefits on Cardiovascular Health: A Review. Molecules MDPI) 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandropoulou, I.; Goulis, DG.; Merou, T.; Vassilakou, T.; Bogdanos, DP.; Grammatikopoulou, MG. Basics of Sustainable Diets and Tools for Assessing Dietary Sustainability: A Primer for Researchers and Policy Actors. Healthcare, 2022; 10. [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente-Arrillaga, C.; Vzquez Ruiz, Z.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Sampson, L.; Martinez- González, MA. Reproducibility of an FFQ validated in Spain. Public Health Nutr 2010, 1364–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, MA.; Sánchez-Tainta, A.; Corella, D.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Ros, E.; Arós, F. A provegetarian food pattern and reduction in total mortality in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) study. Am J Clin Nutr 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (frequency) | 4,758 | 6,895 | 3,706 | 3,297 |

| Planetary Health Diet range | 7-18 | 19-21 | 22-23 | 24-37 |

| Planetary Health Diet median | 17 | 20 | 22 | 24 |

| Age | 38.2 (12.4) | 38 (12.1) | 38.1 (12.2) | 38 (12.3) |

| Marital status (%) | ||||

| Single | 50.4 | 45.1 | 40.2 | 38.7 |

| Married | 45.2 | 49.7 | 54.3 | 53.3 |

| Other | 4.6 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 1.0 |

| Smoking (%) | ||||

| Never | 51.9 | 50.1 | 46.3 | 46.2 |

| Current smoker | 23.7 | 22.4 | 21.7 | 18.3 |

| Former smoker | 24.4 | 27.5 | 32.0 | 35.5 |

| Cumulative smoking habit (pack-years) | 5.4 (9.3) | 5.7 (9.4) | 6.6 (10.2) | 7.2 (10.8) |

| Years of university | 5.1 (1.5) | 5.0 (1.5) | 5.1 (1.5) | 5.1 (1.5) |

| Physical activity (METs/h/week) | 20.1 (22.2) | 21.5 (22.3) | 22.5 (23.8) | 24.2 (24.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.6 (3.4) | 23.5 (3.5) | 23.7 (3.7) | 23.5 (3.5) |

| Time spent sitting (h/d) | 5.5 (2.0) | 5.3 (2.1) | 5.2 (2.0) | 5.1 (2.1) |

| Watching television (h/d) | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.2) |

| Weight gain of > 3 kg in the last 5 years (%) | 34.5 | 30.1 | 29.7 | 24.4 |

| Snacking between meals (%) | 37.4 | 33.7 | 30.5 | 29.4 |

| Follow-up of special diet (%) | 5.7 | 7.2 | 8.7 | 13.4 |

| Supplements consumption (%) | 17.5 | 18.1 | 18.6 | 22.4 |

| Prevalent diseases (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 3.3 |

| Hypertension | 8.5 | 9.8 | 12.5 | 12.6 |

| Dyslipemia | 5.8 | 6.0 | 7.4 | 8.1 |

| Depression | 10.6 | 11.1 | 11.5 | 13.8 |

| Cancer | 2.2 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 3.7 |

| Trichopoulou MDS [31], (range, 0-9) | 3.0 (1.5) | 4.1 (1.6) | 4.8 (1.6) | 5.6 (1.5) |

| MEDAS [32], (range, 0-14) | 4.9 (1.6) | 5.9 (1.6) | 6.4 (1.7) | 7.3 (1.8) |

| Provegetarian score [47], (range, 12-60) | 32.2 (4.3) | 35.4 (4.0) | 37.8 (3.9) | 40.8 (4.2) |

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (frequency) | 4,758 | 6,895 | 3,706 | 3,297 |

| Planetary Health Diet range | 7-18 | 19-21 | 22-23 | 24-37 |

| Food (g/d) | ||||

| Vegetables | 394.7 (268.9) | 528.9 (314.3) | 583.9 (335.8) | 667.1 (415.3) |

| Fruits | 171.9 (164.6) | 276.5 (219.2) | 347.4 (267.6) | 412.2 (316.6) |

| Unsaturated oils1 | 17.6 (13.6) | 22.3 (15.6) | 25.2 (16.7) | 28.2 (18.3) |

| Olive oil | 13.3 (11.7) | 17.9 (14.0) | 21.1 (15.5) | 24.4 (17.1) |

| Legumes | 18.8 (13.7) | 22.1 (15.8) | 24.1 (17.7) | 28.8 (25.4) |

| Nuts | 4.6 (6.1) | 6.0 (8.6) | 7.8 (11.7) | 14.6 (19.8) |

| Cereals | 97.0 (70.7) | 100.2 (71.0) | 101.8 (70.4) | 110.8 (78.6) |

| Whole grains | 5.4 (15.0) | 9.9 (24.1) | 15.3 (33.2) | 29.0 (49.0) |

| Fish | 84.3 (55.1) | 97.9 (55.5) | 104.8 (58.7) | 111.4 (73.6) |

| Beef and lamb | 62.8 (33.8) | 56.6 (33.0) | 52.0 (34.3) | 37.9 (34.9) |

| Pork | 81.9 (43.8) | 75.5 (41.9) | 67.0 (41.0) | 52.1 (41.1) |

| Poultry | 51.9 (37.6) | 43.8 (33.0) | 36.2 (29.6) | 29.8 (29.9) |

| Eggs | 28.0 (17.6) | 24.7 (14.6) | 21.0 (15.2) | 15.6 (12.3) |

| Dairy | 506.7 (284) | 431.0 (249) | 381.0 (242.6) | 328.5 (229.7) |

| Potatoes | 69.7 (51.8) | 54.3 (43.5) | 44.2 (38.0) | 37.0 (33.1) |

| Added sugars | 58.3 (30.3) | 45.7 (24.9) | 37.8 (22.4) | 30.9 (21.0) |

| Fast food2 | 28.1 (23.3) | 22.7 (19.8) | 18.7 (19.2) | 15.3 (17.6) |

| Energy and nutrients | ||||

| Energy (kcal/d) | 2434 (651) | 2352 (610) | 2277 (582) | 2248 (586) |

| Carbohydrates (% TEI) | 42.7 (7.1) | 43.1 (7.0) | 43.5 (7.5) | 45.1 (8.6) |

| Fiber (g/d) | 17.7 (7.3) | 21.8 (8.3) | 24.3 (9.5) | 29.2 (12.1) |

| Proteins (% TEI) | 18.5 (3.5) | 18.5 (3.3) | 18.3 (3.1) | 17.5 (3.4) |

| Fats (% TEI) | 36.9 (6.0) | 36.4 (6.3) | 36.1 (6.8) | 35.2 (7.7) |

| MUFAs | 15.4 (3.1) | 15.7 (3.6) | 16.0 (4.0) | 16.2 (4.5) |

| PUFAs | 5.3 (1.6) | 5.1 (1.5) | 5.1 (1.6) | 5.2 (1.7) |

| n-3 fatty acids (g/d) | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.6 (1.2) | 2.5 (1.1) | 2.6 (1.2) |

| n-6 fatty acids (g/d) | 20.0 (13.6) | 18.0 (11.8) | 16.7 (10.89 | 15.6 (11.3) |

| SFAs | 13.8 (3.1) | 12.8 (3.0) | 12.0 (2.9) | 10.6 (3.1) |

| TFAs | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) |

| Cholesterol (mg/d) | 473.4 (155.7) | 432.4 (142.4) | 388.1 (128.7) | 325.4 (126.9) |

| Alcohol (g/d) | 6.3 (10.2) | 6.7 (10.3) | 6.9 (10.0) | (9.6) |

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | p for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 4,758 | 6,895 | 3,706 | 3,297 | |

| PHD range | 7-18 | 19-21 | 22-23 | 24-37 | |

| CVD | 53 | 78 | 44 | 45 | |

| Person-years | 62597.7 | 89631.6 | 48404.5 | 41548.6 | |

| Mortality rate/1000 person years | 0·84 | 0.87 | 0.91 | 1.08 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.98 (0.69-1.40) | 0.75 (0.50-1.13) | 0.74 (0.49-1.12) | 0.081 |

| Model 2 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.97 (0.68-1.39) | 0.76 (0.50-1.15) | 0.78 (0.52-1.19) | 0.150 |

| Model 3 | 1 (Ref.) | 0.98 (0.68-1.40) | 0.74 (0.49-1.12) | 0.77 (0.51-1.18) | 0.127 |

| Cumulative Diet Average1 | |||||

| Planetary Health Diet range | 7-19 | 19.5-21 | 21.5-23 | 23.5-36.5 | |

| CVD cases | 61 | 63 | 49 | 47 | |

| Person-years | 77681.8 | 66065.4 | 54292.8 | 54140.7 | |

| Mortality rate/1000 person years | 0.79 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 1.04 | |

| Model 3 | 1 (Ref.) | 1.18 (0.82-1.70) | 0.88 (0.60-1.31) | 0.82 (0.55-1.23) | 0.229 |

|

1Reapeted measures: cumulative average information of the Planetary Health Diet Index at baseline and after 10 years of follow-up. Ref. reference. Model 1: adjusted for sex, and stratified by age (deciles) and by year entering the cohort. Model 2: additionally adjusted for total energy intake (kcal/d, continuous), educational level (years of higher education, continuous), smoking (never, current, and former smoker), accumulated smoking habit (pack-years, continuous), alcohol intake (g/d, continuous), physical activity (metabolic equivalent-h/week, continuous), snacking between meals (yes/no), body mass index (BMI [kg/m2, linear and quadratic terms, continuous]), time spent sitting (hours/week, continuous), watching television (h/d, continuous) and following a special diet at baseline (yes/no). Model 3: additionally adjusted for family history of CVD (yes/no), and any diagnosis of diabetes (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), dyslipidemia (yes/no), depression (yes/no), and cancer (yes/no). | |||||

| N | CVD events | HR (95%CI) | p for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Main analyses | ||||

| Main analyses | 18,656 | 220 | 0.77 (0.51-1.18) | 0.127 |

| Sensitivity analyses | ||||

| Only men | 11,312 | 45 | 0.68 (0.24-1.92) | 0.450 |

| Only women | 7,344 | 175 | 0.75 (0.47-1.21) | 0.151 |

| Only <45 years | 13,234 | 41 | 0.86 (0.30-2.47) | 0.680 |

| Only ≥45 years | 5,422 | 179 | 0.80 (0.50-1.27) | 0.170 |

| Only health professionals | 11,980 | 134 | 0.75 (0.44-1.28) | 0.676 |

| Only non-health professionals | 6,676 | 86 | 0.71 (0.36-1.44) | 0.312 |

| Excluding hypertension or hypercholesterolemia at baseline | 14,278 | 86 | 0.81 (0.41-1.57) | 0.420 |

| Energy limits: percentiles 5-95 at baseline | 18,517 | 206 | 0.70 (0.45-1.09) | 0.071 |

| Excluding participants with cancer at baseline | 18,163 | 211 | 0.77 (0.50-1.17) | 0.110 |

| Excluding participants with special diet at baseline | 17,129 | 192 | 0.75 (0.48-1.18) | 0.910 |

| Excluding participants with 30 or more missing values in FFQ | 17,453 | 182 | 0.79 (0.50-1.25) | 0.133 |

| Excluding early cases (first 2 years) | 18,628 | 192 | 0.76 (0.49-1.19) | 0.910 |

| Adjusted for sex, and stratified by age (deciles) and by year entering the cohort, total energy intake (kcal/d, continuous), educational level (years of higher education, continuous), smoking (never, current, and former smoker), accumulated smoking habit (pack-years, continuous), alcohol intake (g/d, continuous), physical activity (metabolic equivalent-h/week, continuous), snacking between meals (yes/no), body mass index (BMI [kg/m2, linear and quadratic terms, continuous]), time spent sitting (hours/week, continuous), watching television (h/d, continuous) and following a special diet at baseline (yes/no), family history of CVD (yes/no), and any diagnosis of diabetes (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), dyslipidemia (yes/no), depression (yes/no), and cancer (yes/no). | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).