1. Introduction

Despite sustained global efforts, stunting remains a critical public health challenge, with numerous countries including Malaysia falling short of achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goal of reducing stunting among children by 2030 [

1]. Stunting, defined as height-for-age z-score (HAZ) less than −2 standard deviations of the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards [

2], represents chronic undernutrition during the critical early years of life. Multiple interconnected factors contribute to this condition, including poor maternal nutrition, low birth weight, failure of exclusive breastfeeding, inadequate dietary intake, recurrent infections, and poor environmental sanitation, which compound to create long-term nutritional deficiency in children [

3].

Globally, stunting affected 150.2 million children under five years of age in 2024, representing 23.2% of this age group [

4]. While the global prevalence has declined from 26.4% in 2012, progress remains insufficient to meet the 2030 target of a 40% reduction [

5]. Asia continues to bear the highest burden, with 53% of stunted children globally residing in this region, and South Asia alone accounting for 56 million stunted children [

4]. The highest stunting prevalence is observed in South-central Asia (36%) and sub-Saharan Africa regions (East Africa 42%; West Africa 36%), where the number of stunted children continues to increase despite global progress [

4].

1.1. The Malaysian Context

Malaysia presents a particularly concerning profile among middle-income countries in Southeast Asia. According to the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS), the stunting rate in Malaysia increased alarmingly from 17.7% in 2015 to 21.2% in 2022 – a trend that contradicts the declining patterns observed in neighboring Southeast Asian nations [

6,

7]. This 20% increase over this period positions Malaysia’s stunting prevalence (21.8%) higher than countries such as the West Bank and Gaza (7.4%) and comparable to Iraq (22.6%), despite Malaysia’s significantly higher economic development [

8,

9].

Geographic disparities within Malaysia are stark. Kelantan, one of the north-eastern states, recorded the highest stunting rate at 28.8%, followed by Pahang (26.2%) and Terengganu (23.4%) [

6]. These rates substantially exceed Malaysia’s 2030 target of reducing stunting to 14.2%, and the National Plan of Action for Nutrition 2016-2025 target of 11.0% by 2025, indicating a persistent and worsening nutritional crisis that necessitates immediate intervention [

9,

10]. Importantly, stunting in Malaysia cuts across all socioeconomic strata: even among households with monthly income exceeding RM5,000, the prevalence remains 17.4%, and among children of mothers with tertiary education, the rate is 18.6% [

11]. This unusual pattern suggests that factors beyond household income and parental education contribute significantly to stunting in the Malaysian context.

1.2. Consequences of Stunting

Stunting represents far more than hindered physical growth; it is a comprehensive indicator of persistent undernutrition with profound and enduring effects across the life course. Evidence consistently demonstrates that early-life stunting among children has major effects on future cognitive function, educational attainment, and health outcomes [

12]. Stunted children exhibit increased susceptibility to infections, higher functional impairments, elevated mortality risks, and greater vulnerability to chronic diseases during adulthood [

12]. The cognitive and educational impacts are particularly concerning: children who recover to normal height status (HAZ ≥ −1) by age 5 demonstrate cognitive function levels similar to children who were never stunted, emphasizing the critical importance of early intervention [

13]. Children who remain stunted, however, face substantially reduced academic performance, shorter adult height, and diminished economic productivity, perpetuating intergenerational cycles of poverty and undernutrition.

1.3. Nutritional Determinants and Intervention Approaches

Micronutrient deficiencies play a pivotal role in growth faltering. Deficiencies in vitamin A, iron, zinc, and iodine contribute to 35% of deaths in children under five years of age [

14]. Inadequate intake of calcium and vitamin D further increases the likelihood of stunting [

15]. Recent evidence from systematic reviews demonstrates that prenatal multi-micronutrient supplementation (MMS) produces superior effects compared to single-nutrient approaches in promoting optimal growth in children [

16,

17]. Multiple micronutrient interventions have shown efficacy in improving not only anthropometric outcomes but also biochemical markers of nutritional status across diverse populations [

18].

Evidence from intervention studies conducted in Asian and African settings demonstrates that nutrient-dense oral nutrition supplements (ONS) can significantly improve height, weight, and growth z-scores in undernourished children [

13,

19]. Recent randomized controlled trials in Vietnam showed that ONS combined with dietary counseling resulted in significant improvements in height-for-age percentiles, with effects becoming evident after 24 weeks of supplementation, and approximately 40% of stunted children recovering to normal height status after 6 months [

13,

20]. Similarly, studies in India demonstrated that ONS with dietary counseling was more effective than counseling alone in promoting catch-up growth, with significant improvements in weight-for-age and height-for-age z-scores [

19,

21].

Linear growth has been found to lag behind weight gain by approximately 3 months in undernourished children, emphasizing the importance of intervention durations of at least 120-180 days to adequately assess effects on linear growth [

13]. Most successful studies examining height gain in stunted children have employed interventions lasting 6 months or longer [

13,

19].

1.4. Evidence Gap

Despite the growing body of evidence from neighboring countries such as Vietnam, India, and other Asian settings, evidence specific to Malaysia remains critically limited, particularly in regions such as Kelantan where the burden of stunting is highest [

6]. No community-based intervention trials examining the efficacy of nutrient-dense ONS have been conducted in Malaysian populations. This gap is particularly significant given Malaysia’s unique stunting profile, which differs from typical patterns observed in other countries, where stunting correlates strongly with poverty and low parental education. The lack of locally generated evidence limits the ability of policymakers to design and implement context-appropriate interventions that address the specific determinants of stunting in Malaysia.

Furthermore, while international evidence demonstrates the efficacy of ONS in children with severe stunting (HAZ < -2 SD), there is limited evidence on the effectiveness of such interventions in children who are at-risk of stunting (HAZ between -2 and -1 SD) – a population that represents a critical window for preventive intervention before irreversible growth faltering occurs. This preventive approach aligns with WHO recommendations emphasizing early identification and intervention for children at nutritional risk [

2].

1.5. Study Objectives

The present study was designed to address these critical evidence gaps by evaluating the efficacy of a nutrient-dense ONS (commercially known as Dutch Lady MaxGro) on linear and ponderal growth among Malaysian children aged 12–36 months who are stunted or at-risk of stunting. Specifically, the study aimed to: (1) Determine whether daily consumption a nutrient-dense ONS for 180 days improves stunting in children with compromised nutritional status; (2) Estimate the rate of stunting, underweight, wasting, and overweight among the study children at baseline and subsequently at 90 days and at 180 days after intervention; and (3) Determine the changes in nutrient intakes before and after the intervention.

1.6. Study Significance and Expected Impact

The findings will provide locally generated evidence to inform policy development, clinical practice guidelines, and program scalability for nutrition interventions. By including both stunted and at-risk children during the critical 12–36-month age window – when growth failure is potentially reversible – this research addresses both treatment and prevention within a single framework. The evidence generated from this trial would provide a scalable, evidence-based intervention that could be integrated into Malaysia’s existing maternal and child health programs to reverse the alarming trend of increasing childhood stunting in the country.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in Kelantan, Malaysia from December 2022 to March 2024 by using a community-based single arm intervention trial design.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Eligible children were Malaysian citizens, boys or girls aged between 12 and 36 months, with a HAZ between < –1.0 SD and >- 3 SD and a weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) between < –1.0 SD and ≥ - 3 SD, according to the WHO Child Growth Standards. Parents or legal guardians were required to be able to read and communicate in either Malay or English and to provide written informed consent prior to participation. Only apparently healthy children with no current infection, chronic illness, or physical or mental disability were included. In addition, parents or legal guardians were required to own a mobile or smartphone, and mothers must have previously received breastfeeding counselling from a qualified breastfeeding counsellor.

Exclusion criteria included children with any chronic disease, congenital disorder, or deformity. Children with an ongoing episode of diarrhoea or a history of persistent diarrhoea within the past month were excluded. Those with a known cow’s milk allergy or milk intolerance, children already consuming multivitamins (including iron) prior to enrolment, and those who were still receiving breast milk as part of their diet were also excluded.

2.2. Ethical Procedures

The protocols and materials of the present study were reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM/JEPeM/22050302). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles mentioned in the Declaration of Helsinki and was consistent with Good Clinical Practice (GCP). The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT05670002).

2.3. Screening of Subjects

Children were identified across 50 nurseries in Kelantan using a convenience sampling method. Of 1,438 children assessed for eligibility, 118 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled after parental consent; 91 completed the study.

2.4. Sample Size Calculation

The power analysis for the primary outcome was based on a published report [

22]. Baseline and post-intervention height-for-age z-scores (HAZ) were −1.96 ± 0.62 and −1.70 ± 0.76, respectively. The estimated mean difference (effect size) between pre- and post-test was 0.30, with a pooled standard deviation of 0.98. Assuming a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05) and 80% power (β = 0.20), the required sample size was 86. Considering a 28% dropout rate, the final target sample size was 110 participants.

2.5. Anthropometric Measurements

Anthropometric assessments were conducted at three time points: baseline (T0), day 90 (mid-intervention), and day 180 (post-intervention).

Standing height was measured in duplicate using a SECA stadiometer, recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. Children were measured without hair ornaments, headgear, or jewelry. During measurement, each child stood barefoot on the stadiometer platform with feet together, body upright, arms relaxed at the sides, and the head positioned in the Frankfurt horizontal plane. If duplicate measurements differed by more than 10%, a third measurement was obtained, and the mean of the closest values was calculated. Anthropometric status was classified using the WHO Anthro software (version 3.2.2) for children under five years of age and standardized for sex and age based on the WHO (2006) reference standards [

2]. Stunting was defined as HAZ < −2 SD, at risk of stunting as HAZ between −2 SD and < −1 SD, and normal height growth as HAZ ≥ −1 SD [

2]. HAZ scores were calculated using raw anthropometric measurements.

Body weight was measured in duplicate using an automatic digital scale (SECA 769) with a precision of 10 g. Measurements were taken on a flat, stable surface with children in minimal clothing and without shoes or jewelry. If duplicate measurements differed by more than 10%, a third measurement was obtained, and the mean of the closest values was calculated. The scale was calibrated at each measurement session. According to WHO (2006) reference standards, underweight was defined as WAZ between −3 SD and < −2 SD, and normal weight as WAZ between −2 SD and 2 SD. Wasting was defined as weight-for-height z-score WHZ between −3 SD and < −2 SD, overweight as WHZ > 2 SD to 3 SD and normal as -2 SD to 2 SD [

2].

2.6. Dietary Assessment

A quantitative 3-day, 24-h dietary recall (two weekdays and one weekend day) was conducted by telephone and in-person at baseline (T0) and post-intervention (day 180) to estimate energy and nutrient intakes. Interviews were administered by trained research assistants under the supervision of a nutritionist and were conducted without prior notification to mothers.

Nutrient analysis was performed using Nutritionist Pro (Axxya Systems). Food composition data were sourced primarily from the Malaysian Food Composition Database [

23], supplemented by the USDA database (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service (USDA ARS, 2024) and food product labels as needed [

24].

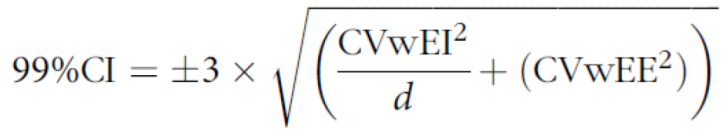

Prior to analysis, plausibility of intake was evaluated using the Black and Cole formula Black and Cole (2000) [

25], by calculating the ratio of reported energy intake (EI) to predicted energy expenditure (EE). EE was estimated as basal metabolic rate (BMR) [

26,

27] multiplied by a physical activity level (PAL) of 1.60, assuming moderate activity for children aged 12-48 months [

28]. Following Black and Cole (2000) and using a 99% CI, within-subject coefficients of variation of 8.2% for EE and 23% for EI were applied [

25].

where CV wEE = within-subject variation in of EE, 8·2%, CV wEI = within-subject variation in EI, 23%, and d = number of days of diet assessment.

The Scofield equation [

26] for estimating BMR in kcal/day (kilocalories per day) from body weight (kg).

The acceptable EI:EE range was 0.30–1.70; only children within this range were retained for dietary analyses. Out of the 91 children, a four over-reporting subjects were excluded and a total of 87 children were included in the analysis Nutrient analyses did not include intake from dietary supplements.

2.7. Study Intervention

All subjects were asked to consume 510 mL (170 mL x 3 servings/day) of Nutrient Dense Oral Nutrition Supplement (ONS) Dutch Lady MaxGro on a daily basis for a duration of (180 days), 6 months. Subjects were asked to take the product, three servings per day; 1) in the morning, upon waking, 2) 2-3 hours after lunch and 3) before going to bed at night. Preparation for each serving: 1 sachet (27g) of MaxGro powder + 150 mL water = 170 mL.

2.8. Subject Compliance

To ensure compliance, parents were contacted three times by telephone calls after 60, 120, and 150 days of intervention. They were also followed by two home or nursery visits to replenish the nutrient dense (ONS) supply after 30 and 90 days of the start of intervention.

Subjects’ compliance was assessed by collecting and counting the number of empty sachets returned. Compliance at each time point was calculated as the number of sachets returned relative to the total number of sachets provided, multiplied by 100 to find the percentage. The overall compliance percentage was determined by averaging values across all the three time points. The subject considered compliant when the average percentage of all time points is 80% and above. The mean compliance rate of all children was 97.4 ± 6.70 percentage.

2.9. Data Management and Statitical Analysis

The quality of data collected was checked in two steps: first, by data checking all entries in SharePoint against paper forms and questionnaires and then SharePoint entries against paper forms to validate the first-round data entry. During data cleaning process, logic checks were performed to identify inconsistencies and implausible values between related variables (e.g., age versus date of birth, date of measurement, consistency of dietary entry, etc.). Implausible or inconsistent data were verified against source forms and corrected when necessary. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 27.0 (IBM Corp.). Improvement in linear growth was assessed by comparing height, weight, BMI, and HAZ at three points of time (baseline or T0, at 90 days, and at 180 days) by using repeated measures ANOVA. HAZ and WAZ were also compared between stunted and at-risk stunted children at the three points of time. Changes in nutrient intakes, such as energy (kcal), protein, carbohydrate, fat, vitamins, and minerals were compared between baseline and at 180 days after intervention by paired sample t-test. Statistical significance was assessed when p-value was ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study CONSORT Flowchat

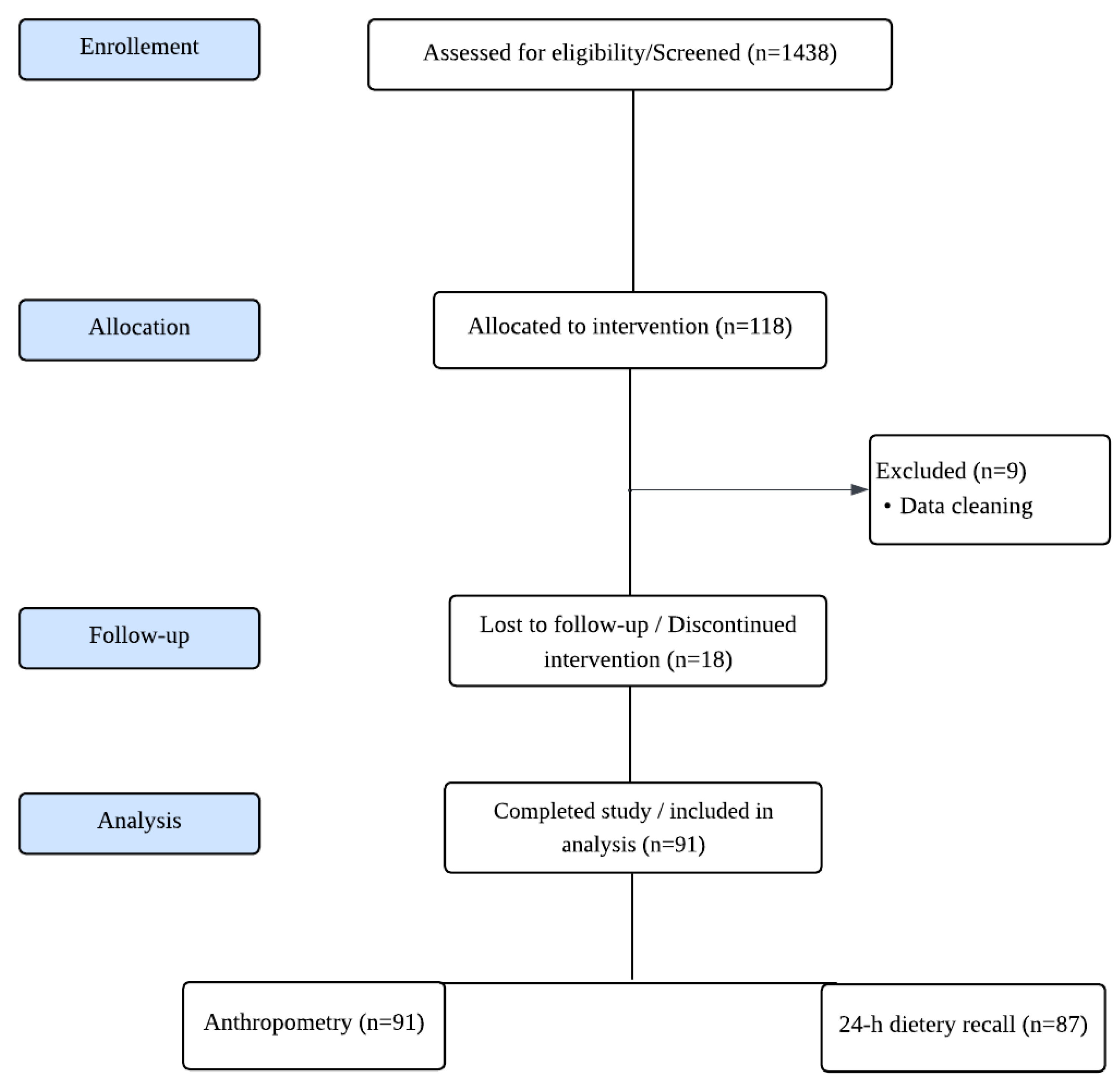

Figure 1.

Study CONSORT flowchart.

Figure 1.

Study CONSORT flowchart.

A total of 1438 children were screened and assessed for eligibility. A total of 118 children were enrolled in the study. Following data cleaning, 9 participants were excluded, and 91 completed the study and were included in the final analysis.

3.2. Sociodemographic Profile

Table 1 shows that all participants were Malay children, and were Muslims. The majority were boys (64.8%), whereas 35.2% were girls. The majority of children attended nursery (83.5%), but only 3.3% went to kindergarten or preschool. Almost all parents or guardians were married (98.9%). The majority of participants’ fathers had tertiary education (73.6%), while 23.1% had completed secondary education, and 2.2% had basic education or no formal schooling. Similarly, most of the mothers had tertiary education (78.0%). Most of the households are in the lower economic class for the monthly household food expenditure (87.9%).

3.3. Anthropometric Results

Table 2 summarizes the anthropometric indicators at baseline (T

0), 90 days, and 180 days. Height increased significantly over time (p < 0.001), from baseline 84.2 ± 4.91 cm to 86.7 ± 4.58 cm at 90 days and to 88.7 ± 4.26 cm at 180 days. Post hoc analysis confirmed significant differences across all pairwise comparisons (baseline vs. 90 days, baseline vs. 180 days, and 90 days vs. 180 days; all p < 0.001).

Weight also showed a significant main effect of time (p < 0.001) – children’s mean weight increased from baseline of 11.1±1.24 kg to 11.6±1.28 kg at 90 days, and to 12.2±1.36 kg at 180 days. Post hoc analysis indicated significant gain between baseline and 180 days (p < 0.001), whereas changes between baseline and 90 days and between 90 and 180 days were not statistically significant.

For BMI, a significant main effect of time was observed (p < 0.01). Mean BMI values improved from 15.7±1.23 kg/m2 at baseline to 15.5 ±1.19 kg/m2 at 90 days and 15.5 ±1.26 kg/m2 at 180 days. Post hoc analysis identified a significant difference between baseline and 90 days and between baseline and 180 days (p < 0.05).

HAZ increased from baseline of -1.94± 0.42 to -1.77± 0.43 at 90 days, and to -1.76± 0.41 at 180 days. Post hoc tests confirmed significant increases between baseline and 90 days (p < 0.001) and baseline and 180 days (p < 0.001), with no differences between 90 and 180 days.

When comparing HAZ between groups (stunted vs. at-risk), a significant group effect was observed (p < 0.001). In the stunted group, HAZ improved from -2.33± 0.29 at baseline to -2.11± 0.38 at 90 days and -2.07± 0.44 at 180 days. In the at-risk group, HAZ improved from -1.66± 0.24 at baseline to -1.54 ± 0.29 at 90 days and -1.54 ± 0.27 at 180 days. Post hoc analysis showed significant increases for both groups from baseline to 90 days and baseline to 180 days (all p < 0.001). From 90 to 180 days, significant improvement was seen only in the stunted group (p < 0.001), while no change was detected in the at-risk group (p > 0.05).

WAZ changed significantly over time and differed between nutritional status groups (p < 0.001). In the stunted group, mean WAZ increased modestly from −1.58 ± 0.60 at baseline to −1.57 ± 0.65 at 90 days and −1.49 ± 0.70 at 180 days, with no significant differences between time points. In contrast, the at-risk group showed a significant improvement in WAZ from −1.13 ± 0.67 at baseline to −1.04 ± 0.63 at 90 days and −1.01 ± 0.70 at 180 days (p < 0.05), with no difference between 90 and 180 days.

WHZ did not change significantly across time points. Mean WHZ values were -0.40 ± 0.85, -0.43 ± 0.86 and -0.34 ± 0.95 at baseline, 90 days and 180 days, respectively.

Table 3 presents the percentage of children by nutritional status indicators (HAZ, WAZ, and WHZ) across baseline, 90 days, and 180 days. The percentage of stunted children decreased from 40.7% at baseline to 33.0% at 90 days and to 25.3% at 180 days. At the same time, the proportion of children classified as at risk of stunting increased from 59.3% to 65.9% and 73.6% at 90 days and at 180 days, respectively. One child (1.1%) achieved normal HAZ status at both 90 and 180 days. McNemar test indicated a statistically significant reduction in stunting of nearly 38%, from baseline to 180 days (p = 0.003).

For underweight status, the prevalence decreased from 14.3% at baseline to 13.2% at 90 days and to 8.8% at 180 days, accompanied by an increase in the proportion of children with normal weight-for-age z-scores (from 85.7% to 91.2%). Although these changes reflect a positive shift in nutritional status, the differences were not statistically significant.

Wasting remained stable at 3.3% from baseline to 90 days before falling to 1.1% at 180 days. Two children (2.2%) were classified as overweight at 180 days. These latter two children were already near the upper cut-off at baseline, and their classification shift is consistent with expected growth patterns rather than disproportionate increases in WHZ.

Overall, the data indicate a significant increase in height and weight over the 180-days of the intervention and a significant reduction in stunting.

3.4. 24-h Dietary Recall

Table 4 summarizes changes in nutrient intake across baseline and 180 days. Overall, significant improvements were observed in almost all macronutrients and micronutrients when comparing baseline to 180 days, except carbohydrates. This indicates that while the overall dietary profile improved, carbohydrate intake remained relatively stable throughout the intervention.

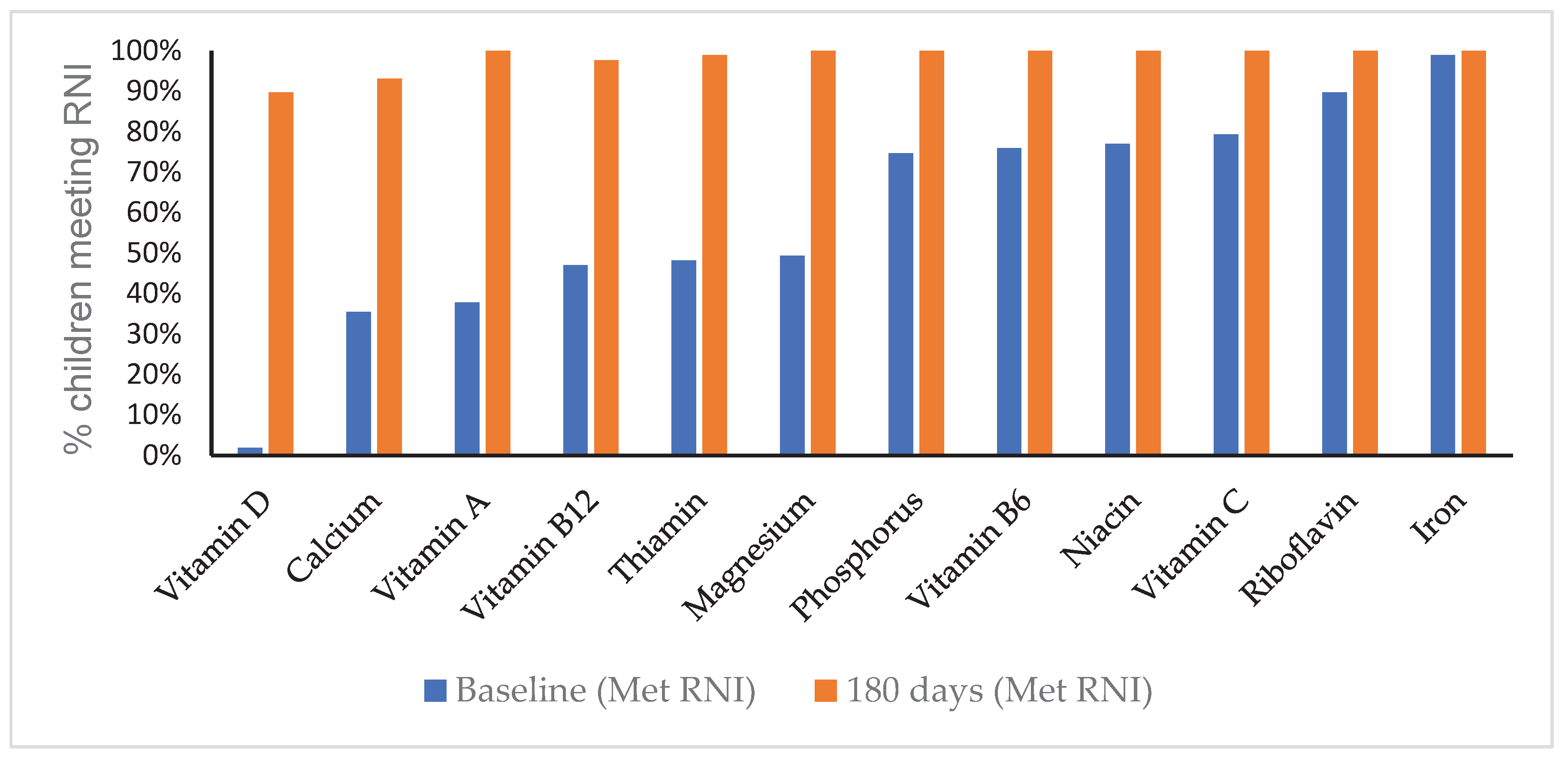

Figure 2 shows the percentage of children meeting the level of the Malaysian Recommended Nutrient Intake (RNI) at baseline and at 180 days. At baseline, adequacy varied widely across nutrients: iron (99%), riboflavin (90%), vitamin C (79%), and niacin (77%) were relatively high, whereas fewer than half of the children met the RNI levels for calcium (36%), vitamin A (38%), vitamin B12 (47%), thiamine (48%), and magnesium (49%). Vitamin D adequacy was the lowest, with only 2% of children meeting the RNI level.

By 180 days, notable improvements were observed across nearly all nutrients, with adequacy approaching or reaching 100% for most vitamins and minerals. Calcium increased from 36% at baseline to 91% at 180 days, while vitamin D rose from 2% to 89%. Thiamine (99%) and vitamin B12 (98%) also improved markedly, though they remained slightly lower than other nutrients. Overall, the intervention resulted in a substantial shift from suboptimal to adequate intake levels across almost all micronutrients.

4. Discussion

This community-based intervention study demonstrates that daily supplementation with 510 mL of nutrient-dense oral nutrition supplement (ONS) substantially improved growth and nutritional status among stunted and at-risk Malaysian children aged 12–36 months. Over 180 days, participants showed significant increases in height, weight, and height-for-age z-scores (HAZ), with improvements evident as early as 90 days. By the end of the intervention there was a reduction of nearly 38% of the number of stunted children, representing a clinically meaningful shift in nutritional status within this vulnerable population. Two cases reported borderline overweight status at the end of the study, but these children were already near the cut-off at baseline and reflect minor shifts across anthropometric thresholds rather than excessive or abnormal weight gain, suggesting the intervention maintained appropriate growth trajectories without promoting overnutrition.

4.1. Comparison with Malaysian Studies

To our knowledge, this is the first community-based ONS intervention trial specifically targeting stunted and at-risk children in Malaysia, particularly in Kelantan, the state with the highest stunting burden (28.8%) [

29]. Previous Malaysian research has predominantly focused on identifying determinants and prevalence of stunting rather than evaluating nutritional interventions [

30,

31]. A recent cross-sectional study in Terengganu among children under 2 years found that 19.3% were stunted, with low birth weight and poor maternal nutritional knowledge identified as key risk factors, though no intervention was tested [

32]. A nationwide survey across 11 states found that approximately one in five children reported at least one form of undernutrition, emphasizing the need for evidence-based nutritional intervention strategies [

33].

Our study addresses this critical evidence gap by providing the first locally generated data on ONS efficacy in the Malaysian context. The 38% reduction in stunting percentage within 6 months is particularly encouraging given that Malaysia’s Deputy Health Ministry reported that almost 30% of young children suffer from stunted growth, with Kelantan having among the highest rates [

7]. This finding is especially relevant to Malaysia’s policy context, as the country’s stunting rate has increased significantly from 17.7% in 2015 to 21.2% in 2022, far exceeding the National Plan of Action for Nutrition target of 14.2% by 2030 [

5,

34]. Our results suggest that ONS interventions could be a viable component of Malaysia’s multisectoral strategy to reverse this alarming trend.

4.2. Comparison with Neighboring Country Data

Our findings align closely with recent evidence from neighboring Asian countries. In a prospective multicenter trial in India, ONS with dietary counseling in children aged 24–48 months, who were at malnutrition risk (

weight-for-height percentile 3rd to 15th) found significant improvements in weight-for-height percentile in the intervention group, as compared to dietary counseling alone (p = 0.009). Anthropometric measurements such as weight and body mass index also increased significantly in the intervention group [

19]. Similarly, Pham et al. (2019) demonstrated that six months of ONS improved HAZ and weight-for-age z-scores (WAZ), with approximately 40% of stunted Vietnamese children recovering to normal height status [

35]. Our study’s finding of significant HAZ improvement within 180 days parallels these Vietnamese results, despite our slightly younger cohort (12–36 months versus 24–60 months).

A recent randomized controlled trial in India involving 223 children aged 3.0 to 6.9 years found that those receiving daily ONS plus dietary counseling grew taller and stronger than those receiving counseling alone [

36]. Earlier Indian studies by Sazawal et al. (2010) reported parallel improvements in HAZ, WAZ, and weight-for-height z-scores (WHZ) following ONS intervention [

37]. Another Indian study in children at malnutrition risk (weight-for-height percentile 3rd to 15th) demonstrated that ONS with dietary counseling produced superior growth outcomes compared to counseling alone [

38]. Ghosh et al. (2018) conducted a 90-day randomized controlled trial in India showing improved nutrient intake and growth, though height changes were modest over the short duration, underscoring the importance of our 180-day intervention period [

38].

Studies from other Asian settings further corroborate our findings. Huynh et al. (2015, 2016) in Vietnam reported steady increases in height and weight over 48 weeks of ONS in 3–4-year-olds, with compliance above 80% [

39,

40]. Devaera et al. (2018) in Indonesia tested ONS over 28 days and observed weight gain but no significant differences in height between groups, reinforcing that longer intervention durations are essential to detect linear growth changes [

41]. Similarly, in the recent Indonesian clustered RCT by Chandra et al. (2025), children receiving 400 mL/day of growth milk for 3 months showed HAZ significantly increased from −1.65 to −1.58 in the intervention group, suggesting the positive effects of growth milk supplementation on children’s growth [

42]. Collectively, these Asian studies support our conclusion that ONS, when delivered consistently at adequate dosage (typically ≥400-600 mL/day) with appropriate clinical monitoring, can reverse early growth faltering across diverse Asian populations.

The dose-response relationship appears important. Evidence from Nigeria demonstrated that only the highest ONS intake (600 mL/day) improved HAZ, while lower doses showed benefits primarily for weight [

43]. Our study provided 510 mL/day, which appears to fall within the effective range for promoting both linear and ponderal growth.

4.3. Comparison with Global Evidence

Our findings contribute to the broader international evidence base on ONS efficacy for childhood undernutrition. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed that polymeric ONS providing complete blends of macronutrients and micronutrients are effective in promoting growth in children aged 9 months to 12 years with undernutrition [

44,

45]. Multiple micronutrient formulations have been found more effective than single-nutrient approaches, as poor growth in developing countries commonly results from multiple nutrient deficiencies rather than single deficiencies [

46].

The pattern of weight gains preceding height gains observed in our study is consistent with global evidence. Previous randomized controlled trials have demonstrated improved weight gain as early as 10 days and consistently at 30 days, while results for height gain are less consistent in short-duration trials [

13,

47]. Among 90-day randomized controlled trials, height gain was significantly larger in the ONS group in only one trial and trended larger but non-significant in two others [

48,

49]. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis showed that studies with longer durations (≥ 180 days), the nutritional interventions significantly improved the weight-for-height z scores, compared to studies where the nutritional intervention period was shorter than 180 days [

50]. Our 180-day intervention duration was therefore appropriately designed to capture linear growth changes.

4.4. Age Considerations for Linear Growth

Our study’s finding of significant improvement in stunted children within 180 days is particularly encouraging given that participants were at least 24 months old at baseline (mean age: 27 months). This supports previous longitudinal analyses demonstrating that linear catch-up growth can occur beyond 24 months or after the first 1,000 days of life [

51]. While the effects of stunting are largely irreversible after the first 1,000 days, and school-level interventions may not impact stunting itself [

52], our data suggest that targeted nutritional interventions during the 12-36 month period – which extends slightly beyond the traditional 1,000-day window – can still produce meaningful improvements in linear growth. This finding has important programmatic implications, as it suggests that children identified with stunting or at-risk status during routine growth monitoring beyond 24 months may still benefit from intensive nutritional support.

4.5. Mechanistic Considerations

The catch-up growth observed in our study can be explained by the synergistic roles of key nutrients in skeletal development and overall growth. Bone elongation occurs at the epiphyseal growth plate, where chondrocytes proliferate, mature, and ossify, driving longitudinal bone growth [

53]. Adequate protein intake is essential to meet amino acid demands for tissue synthesis and to stimulate growth-promoting hormones. Dietary protein raises insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), both of which enhance chondrocyte activity and bone matrix formation [

54].

Alongside protein, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, vitamin D, and vitamin K are required for optimal bone mineralization and structural integrity [

55]. Deficiencies in any of these nutrients can impair linear growth and compromise bone health [

56]. The ONS used in our study provided 360 kcal per day, 16.2 g protein, 13.8 g fat, and 42 g carbohydrates, along with a comprehensive micronutrient profile including calcium (753 mg), iron (6 mg), zinc (4.5 mg), vitamin D3 (12.9 mcg), vitamin C (93 mg), and B vitamins. This complete nutritional package addresses both macronutrient energy requirements and micronutrient needs for growth.

4.6. Study Strengths

This study employed standardized WHO anthropometric assessment methods and included both stunted (HAZ < -2 SD) and at-risk children (HAZ between ≥ −2 SD to < −1 SD), providing evidence on both treatment and prevention strategies within a single intervention framework [

57]. This dual approach is pragmatically important, as identifying and intervening with at-risk children may prevent progression to stunting.

Second, the 180-day intervention duration was appropriately designed based on evidence that linear growth lags behind weight gain by approximately 3 months in undernourished children, ensuring adequate time to observe changes in HAZ. The detection of improvements as early as 90 days also provides valuable information on the time course of nutritional recovery.

4.7. Study Limitations

We acknowledge several important limitations that should be considered when interpreting our findings.

The most significant limitation is the absence of a control group. While ethical considerations informed this decision, as withholding a potentially beneficial nutritional intervention from already stunted or at-risk children raised ethical concerns, this design limits our ability to definitively attribute the observed improvements solely to the ONS intervention. However, a recent controlled study reported by Khadilkar et al. (2025) in India [

36] already demonstrated that ONS with nutritional counseling had significantly greater benefits in improving anthropometric scores compared with counseling alone.

While our study demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements, the sample size may have limited our ability to detect differential effects across subgroups (e.g., by severity of stunting, age, sex, or socioeconomic status). Larger sample sizes in future studies would enable more robust subgroup analyses to identify which children benefit most from ONS interventions.

The use of parent-reported 24-hour dietary recalls is subject to recall bias, social desirability bias, and potential underreporting or overreporting of food intake. While 24-hour recalls are widely used and validated tools for dietary assessment, more objective measures such as biomarkers of nutritional status (serum micronutrient levels, hemoglobin, albumin) would strengthen future studies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this community-based intervention study provides the first Malaysian evidence that daily consumption of 510 mL (three 170 mL servings) of nutrient-dense oral nutrition supplement over 180 days significantly improved linear and ponderal growth in children aged 12–36 months who were stunted or at risk of stunting. Significant gains in height and weight were observed as early as 90 days, with sustained improvements through 180 days. Clinically, the intervention achieved an approximate 38% reduction in stunting prevalence within 6 months, representing a meaningful shift in nutritional status within this high-burden population.

These findings are particularly significant given that Malaysia is experiencing an alarming increase in childhood stunting rates, contrary to declining trends in neighboring Southeast Asian nations, and is currently off-track to meet national targets.

Overall, these findings highlight the potential of fortified ONS as a core component of evidence-based strategies to address stunting and associated micronutrient deficiencies in Malaysian children aged 12–36 months. Despite several limitations, our study provides crucial proof-of-concept that targeted nutritional supplementation can produce clinically significant improvements in growth outcomes among Malaysia’s most nutritionally vulnerable children.

As Malaysia intensifies efforts to reverse rising stunting trends and meet national and global nutrition targets, the evidence generated from this study offers a viable, scalable intervention that can be implemented while more comprehensive, multi-sectoral approaches are developed and tested. The findings support calls for evidence-based nutrition policies in Malaysia and contribute to the regional knowledge base on effective stunting interventions in middle-income Southeast Asian countries facing the paradox of rising child undernutrition amid economic development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, supervision – H.J.J.M., H.V.R and S.N.H.H; National Coordinator, Project Administration, and Funding acquisition -- H.J.J.M., I.K.; Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation – S.A.A.; Original draft, and Visualization, S.A.A., A.K.M.; Writing—review and editing, A.K.M,, S.N.H.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FrieslandCampina, a Dutch multinational dairy cooperative; grant number (P222/UTS262(21). The APC was funded by FrieslandCampina.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocols and materials of the present study were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM/JEPeM/22050302) on 29th November 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian prior to a child’s participation in the study. Permission to conduct data collection was obtained from all relevant parties, including nurseries principals and teachers.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated or analyzed during this study are not publicly available due to confidentiality and compliance with European General Data Privacy Regulations. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the project funder.:

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the subjects, their parents, and caregivers for their cooperation, as well as the nursery’s teachers and staff involved in the study for their support. Also, thanks to Ms Serene Tan for her contribution in the early stage of this research while she was working with FrieslandCampina.

Conflicts of Interest

Although FrieslandCampina was the study’s sponsor, the company’s involvement had no bearing on the results of this study.

Abbreviations

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| CI |

Confidence Interval |

| HAZ |

Height-for-age Z-score |

| MYR |

Malaysian Ringgit |

| NHMS |

National Health and Morbidity Survey |

| ONS |

Oral Nutrition Supplement |

| SD |

Standard Deviation |

| USDA ARS |

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service |

| WAZ |

Weight-for-age Z-score |

| WHZ |

Weight-for-height Z-score |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- Countdown to 2030 Collaboration; Boerma, T.; Requejo, J.; Victora, C.G.; Amouzou, A.; George, A.; Agyepong, I.; Barroso, C.; Barros, A.J.D.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Black, R.E.; Borghi, J.; Buse, K.; Aguirre, L.C.; Chopra, M.; Chou, D.; Chu, Y.; Claeson, M.; Daelmans, B.; et al. Countdown to 2030: Tracking progress towards universal coverage for reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health. Lancet 2018, 391, 1538–1548. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Child Growth Standards: Length/Height-for-Age, Weight-for-Age, Weight-for-Length, Weight-for-Height and Body Mass Index-for-Age: Methods and Development; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Mulyani, A.T.; Khairinisa, M.A.; Khatib, A.; Chaerunisaa, A.Y. Understanding Stunting: Impact, Causes, and Strategy to Accelerate Stunting Reduction—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1493. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); World Health Organization (WHO); International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. Levels and Trends in Child Malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates—Key Findings of the 2025 Edition; UNICEF and WHO: New York, NY, USA, 2025.

- UNICEF. Child Malnutrition. Available online at: https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/malnutrition/, (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Haron, M.Z.; Rohana, A.J.; Hamid, N.A.A.; Omar, M.A.; Abdullah, N.H. Stunting and its associated factors among children below 5 years old on the East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia: Evidence from the National Health and Morbidity Survey. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 30, 155–168. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2022: Nutritional Status; Institute for Public Health, National Institutes of Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia.

- Global Nutrition Report. Country Nutrition Profiles: Malaysia; Development Initiatives: Bristol, UK, 2024. Available online: https://globalnutritionreport.org/resources/nutrition-profiles/asia/south-eastern-asia/malaysia/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Kok, J.K. Shortcomings and Missteps: Malaysia’s Efforts in Addressing Child Stunting; Jeffrey Cheah Institute on Southeast Asia, Sunway University: Selangor, Malaysia, 2024. Available online: https://sunwayuniversity.edu.my/sites/default/files/publications/2024-01/jci-wp-2024-01_shortcomings_and_missteps_-_malaysias_efforts_in_addressing_child_stunting.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Sulaiman, N.; Yeatman, H.; Russell, J.; Law, L.S. A Food Insecurity Systematic Review: Experience from Malaysia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 945. [CrossRef]

- Kok, D. Stunting in Malaysia: Costs, Causes and Courses for Action; Jeffrey Cheah Institute on Southeast Asia, Jeffrey Sachs Center on Sustainable Development: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019; JCI–JSC Working Paper. Available online: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1x9ZP3cqVWxDE6LWCXXVvFT6CZ0OVe9YD/view (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- De Sanctis, V.; Soliman, A.; Alaaraj, N.; Ahmed, S.; Alyafei, F.; Hamed, N. Early and long-term consequences of nutritional stunting: From childhood to adulthood. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021168. [CrossRef]

- Ow, M.Y.L.; Tran, N.T.; Berde, Y.; Nguyen, T.S.; Tran, V.K.; Jablonka, M.J.; et al. Oral nutritional supplementation with dietary counseling improves linear catch-up growth and health outcomes in children with or at risk of undernutrition: A randomized controlled trial. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1341963. [CrossRef]

- Imdad, A.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Haykal, M.R.; Regan, A.; Sidhu, J.; Smith, A.; Bhutta, Z.A. Vitamin A supplementation for preventing morbidity and mortality in children from six months to five years of age. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2022, 3, CD008524. [CrossRef]

- van Stuijvenberg, M.E.; Nel, J.; Schoeman, S.E.; Lombard, C.J.; du Plessis, L.M.; Dhansay, M.A. Low intake of calcium and vitamin D, but not zinc, iron or vitamin A, is associated with stunting in 2- to 5-year-old children. Nutrition 2015, 31, 841–846. [CrossRef]

- Tam, E.; Keats, E.C.; Rind, F.; Das, J.K.; Bhutta, Z.A. Micronutrient supplementation and fortification interventions on health and development outcomes among children under-five in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 289. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, F.; Adu-Afarwuah, S.; Agustina, R.; Ali, H.; Arcot, A.; Arifeen, S.; et al. Effect of prenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation compared with iron and folic acid supplementation on size at birth and subsequent growth through 24 months of age: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 122, 185–195. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Wang, W.; van Velthoven, M.H.; Chang, S.; Han, H.; et al. Effectiveness of complementary food supplements and dietary counselling on anaemia and stunting in children aged 6–23 months in poor areas of Qinghai Province, China: A controlled interventional study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011234. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Yalawar, M.; Saibaba, P.V.; Bhatnagar, S.; Ghosh, A.; Jog, P.; Khadilkar, A.V.; Kishore, B.; Paruchuri, A.K.; Pote, P.D.; Mandyam, R.D.; Shinde, S.; Shah, A.; Huynh, D.T.T. Oral nutritional supplementation improves growth in children at malnutrition risk and with picky eating behaviors. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3590. [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.T.; Hoang, T.N.; Ngo, N.T.; Nguyen, L.H.; Tran, T.Q.; Pham, H.M.; Huynh, D.T.T.; Ninh, N.T. Effect of oral nutritional supplementation on growth in Vietnamese children with stunting. Open Nutr. J. 2019, 13, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, A.; Ranade, A.; Bhosale, N.; Motekar, S.; Mehta, N. Impact of oral nutritional supplementation and dietary counseling on outcomes of linear catch-up growth in Indian children aged 3–6.9 years: Findings from a 6-month randomized controlled trial. Children 2025, 12, 1152. [CrossRef]

- Senbanjo, I.O.; Owolabi, A.J.; Oshikoya, K.A.; Hageman, J.H.J.; Adeniyi, Y.; Samuel, F.; Melse-Boonstra, A.; Schaafsma, A. Effect of a fortified dairy-based drink on micronutrient status, growth, and cognitive development of Nigerian toddlers: A dose–response study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 864856. [CrossRef]

- Tee, E.S.; Ismail, M.N.; Mohd Nasir, A.; et al. Nutrient Composition of Malaysian Foods, 4th ed.; Malaysian Food Composition Database Programme: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1997.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA Food and Nutrient Database for Dietary Studies 2021–2023. Food Surveys Research Group Home Page. Available at: https://www.ars.usda.gov/nea/bhnrc/fsrg, (accessed on August 2024).

- Black, A.E. The sensitivity and specificity of the Goldberg cut-off for EI:BMR for identifying diet reports of poor validity. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 54, 395–404. [CrossRef]

- Poh, B.K.; Ismail, M.N.; Zawiah, H.; et al. Predictive equations for the estimation of basal metabolic rate in Malaysian adolescents. Mal. J. Nutr. 1999, 5, 1–14.

- Schofield, W.N. Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work. Hum. Nutr. Clin. Nutr. 1985, 39(Suppl. 1), 5–41.

- Torun, B.; Davies, P.S.W.; Livingstone, M.B.E.; et al. Energy requirements and dietary energy recommendations for children and adolescents 1 to 18 years old. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1996, 50, S37–S80.

- Institute for Public Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2019: Volume I—Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs): Risk Factors and Other Health Problems; Ministry of Health Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2020.

- Khor, G.L.; Sharif, Z.M. Dual forms of malnutrition in the same households in Malaysia—A case study among Malay rural households. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 12, 427–437.

- Makbul, I.A.A.; Yeo, G.S.; Sharif, R.; Lim, S.M.; Mediani, A.; Geurts, J.; Poh, B.K.; on behalf of the SEANUTS II Malaysia Study Group. Determinants of stunting among children aged 0.5 to 12 years in Peninsular Malaysia: Findings from the SEANUTS II Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2348. [CrossRef]

- Te Ku Nor, T.F.N.; Wee, B.S.; Aung, M.M.T.; Mohamad, M.; Ahmad, A.; Che Taha, C.S.; Ismail, K.F.; Shahril, M.R. Factors associated with malnutrition in children under 2 years old in Terengganu, Malaysia. SAGE Open 2024, 14, 21582440241242184. [CrossRef]

- Poh, B.K.; Wong, J.E.; Lee, S.T.; Chia, J.S.M.; Yeo, G.S.; Sharif, R.; Safii, N.S.; Jamil, N.A.; Chan, C.M.H.; Farah, N.M.; et al. Triple burden of malnutrition among Malaysian children aged 6 months to 12 years: Current findings from SEANUTS II Malaysia. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e151. [CrossRef]

- National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition. National Plan of Action for Nutrition of Malaysia IV (2021–2030); Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2021.

- Pham, D.T.; Hoang, T.N.; Ngo, N.T.; Nguyen, L.H.; Tran, T.Q.; Pham, H.M.; Huynh, D.; Ninh, N.X. Effect of oral nutritional supplementation on growth in Vietnamese children with stunting. Open Nutr. J. 2019, 13, 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, A.; Ranade, A.; Bhosale, N.; Motekar, S.; Mehta, N. Impact of oral nutritional supplementation and dietary counseling on outcomes of linear catch-up growth in Indian children aged 3–6.9 years: Findings from a 6-month randomized controlled trial. Children 2025, 12, 1152. [CrossRef]

- Sazawal, S.; Dhingra, U.; Dhingra, P.; et al. Micronutrient fortified milk improves iron status, anemia and growth among children 1–4 years: A double masked, randomized, controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12167. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Kishore, B.; Shaikh, I.; Satyavrat, V.; Kumar, A.; Shah, T.; Pote, P.; Shinde, S.; Berde, Y. Effect of oral nutritional supplementation on growth and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections in picky eating children at nutritional risk: A randomized, controlled trial. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46(7), 2186–2201. [CrossRef]

- Huynh, D.T.; Estorninos, E.; Capeding, R.Z.; Oliver, J.S.; Low, Y.L.; Rosales, F.J. Effect of oral nutritional supplementation with PediaSure® on growth, appetite, and body composition in Vietnamese children aged 3–4 years: A 48-week prospective study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 28(6), 623–632. [CrossRef]

- Huynh, D.T.T.; Estorninos, E.; Capeding, M.R.; Oliver, J.S.; Low, Y.L.; Rosales, F.J. Impact of long-term use of oral nutritional supplement on nutritional adequacy, dietary diversity, food intake and growth of Filipino preschool children. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e20. [CrossRef]

- Devaera, Y.; Syaharutsa, D.M.; Jatmiko, H.K.; Sjarif, D.R. Comparing compliance and efficacy of isocaloric oral nutritional supplementation using 1.5 kcal/mL or 1 kcal/mL sip feeds in mildly to moderately malnourished Indonesian children: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2018, 21, 315–320. [CrossRef]

- Chandra, D.N.; Rambey, K.R.K.; Aprilliyani, I.; Arif, L.S.; Sekartini, R. The Influence of Growth Milk Consumption on Nutritional Status, Illness Incidence, and Cognitive Function of Children Aged 2–5 Years. Children 2025, 12, 545. [CrossRef]

- Senbanjo, I.O.; Owolabi, A.J.; Oshikoya, K.A.; Hageman, J.H.J.; Adeniyi, Y.; Samuel, F.; et al. Effect of a fortified dairy-based drink on micronutrient status, growth, and cognitive development of Nigerian toddlers—A dose-response study. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 864856. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Hannon, B.A.; Hustead, D.S.; Aw, M.M.; Liu, Z.; Chuah, K.A.; Low, Y.L.; Huynh, D.T.T. Effect of oral nutritional supplementation on growth in children with undernutrition: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3036. [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; McGrath, M.; Sharma, E.; Gupta, P.; Kerac, M. Effectiveness of breastfeeding support packages in low- and middle-income countries for infants under six months: A systematic review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 681. [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, U.; Nguyen, P.; Martorell, R. Effects of micronutrients on growth of children under 5 years of age: Meta-analyses of single and multiple nutrient interventions. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 191–203. [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, P.A.; Lin, L.H.; Noche, M., Jr.; Hernandez, V.C.; Cimafranca, L.; Lam, W.; Comer, G.M. Effect of oral supplementation on catch-up growth in picky eaters. Clin. Pediatr. 2003, 42, 209–217. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Suri, D.; Uauy, R. Assessment of protein adequacy in developing countries: Quality matters. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S77–S87. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Tong, M.; Zhao, D.; Leung, T.F.; Zhang, F.; Hays, N.P.; Ge, J.; Ho, W.M.; Northington, R.; Terry, D.L.; Yao, M. Randomized controlled trial to compare growth parameters and nutrient adequacy in children with picky eating behaviors who received nutritional counseling with or without an oral nutritional supplement. Nutr. Metab. Insights 2014, 7, 85–94. [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Ren, Y.; Jia, Y. Effects of nutritional interventions on the physical development of preschool children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Pediatr. 2023, 12, 991–1003. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.P.; Pathak, B.G.; Raut, S.V.; Kumar, D.; Singh, D.; Sudfeld, C.R.; et al. Linear growth beyond 24 months and child neurodevelopment in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 101. [CrossRef]

- Martorell, R.; Khan, L.K.; Schroeder, D.G. Reversibility of stunting: Epidemiological findings in children from developing countries. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 48 (Suppl. 1), S45–S57.

- Hasan, S.; Naseer, S.; Zamzam, M.; Mohilldean, H.; Van Wagoner, C.; Hasan, A.; et al. Nutrient and hormonal effects on long bone growth in healthy and obese children: A literature review. Children 2024, 11, 817. [CrossRef]

- Watling, C.Z.; Kelly, R.K.; Tong, T.Y.N.; Piernas, C.; Watts, E.L.; Tin Tin, S.; et al. Associations of circulating insulin-like growth factor-I with intake of dietary proteins and other macronutrients. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 4685–4693. [CrossRef]

- Rizzoli, R.; Biver, E.; Bonjour, J.P.; Coxam, V.; Goltzman, D.; Kanis, J.A.; Lappe, J.; Rejnmark, L.; Sahni, S.; Weaver, C.M.; Weiler, H.; Reginster, J.Y. Benefits and safety of dietary protein for bone health—an expert consensus paper endorsed by the European Society for Clinical and Economical Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis, and Musculoskeletal Diseases and by the International Osteoporosis Foundation. Osteoporos. Int. 2018, 29, 1933–1948. [CrossRef]

- Prentice, A.; Schoenmakers, I.; Laskey, M.A.; et al. Nutrition and bone growth and development. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2006, 65, 348–360.

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO AnthroPlus for Personal Computers Manual: Software for Assessing Growth of the World’s Children and Adolescents; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).