Submitted:

08 January 2026

Posted:

09 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

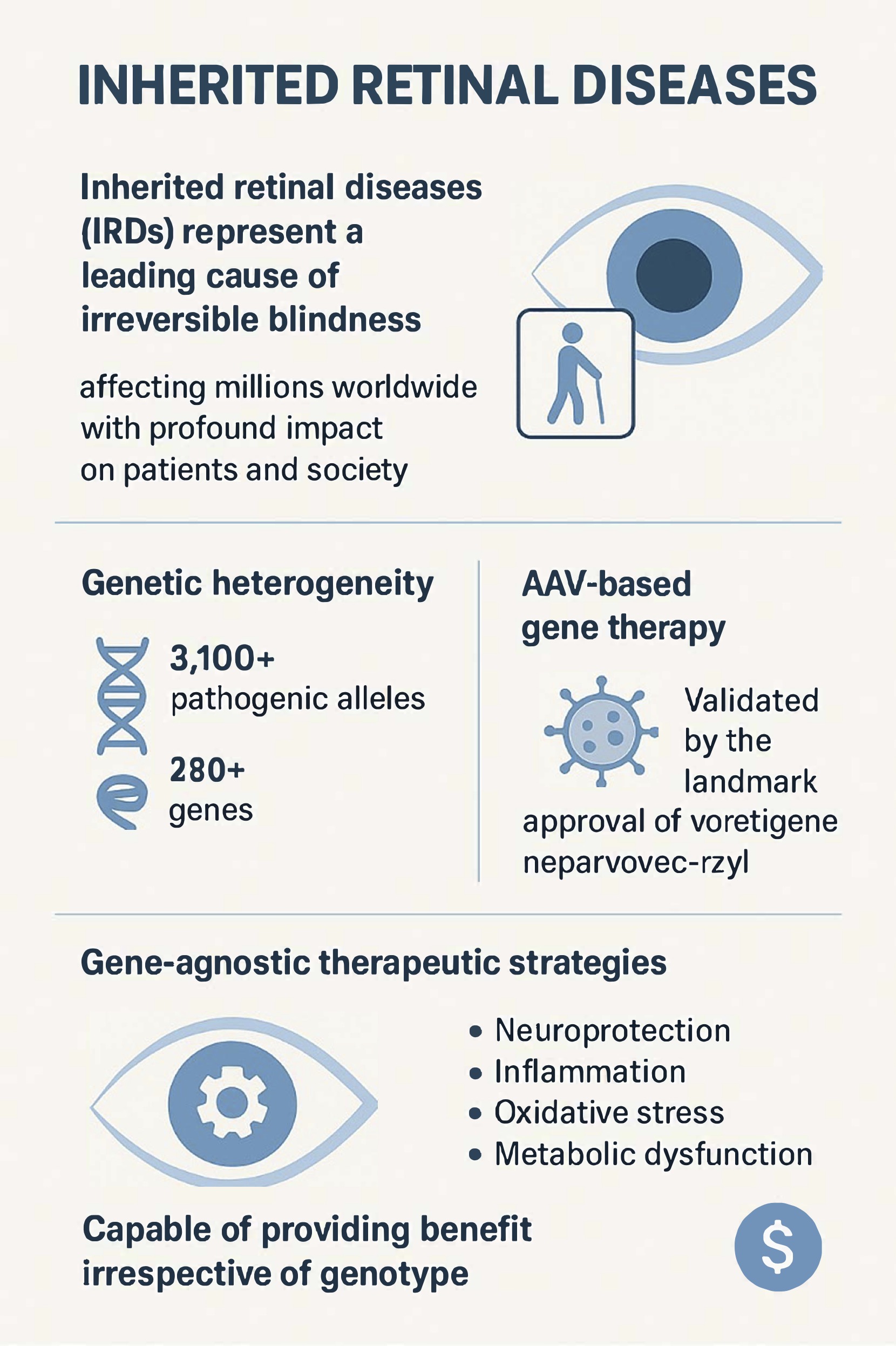

1. Introduction

2. Neuroprotective Approaches

2.1. Growth Factor-Based Therapies

2.1.1. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF)

2.1.2. Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor (CNTF)

2.1.3. Rod-Derived Cone Viability Factor (RdCVF)

2.2. Other Neuroprotective Strategies

3. Regulation of the Complement System

3.1. Complement Dysregulation in IRDs

3.2. Complement Modulation as a Therapeutic Strategy

4. Combination Therapeutic Strategies

4.1. Rationale for Multi-Target Approaches

4.2. Promising Combinations

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Georgiou, M.; Robson, A.G.; Fujinami, K.; de Guimarães, T.A.C.; Fujinami-Yokokawa, Y.; Daich Varela, M.; Pontikos, N.; Kalitzeos, A.; Mahroo, O.A.; Webster, A.R.; et al. Phenotyping and Genotyping Inherited Retinal Diseases: Molecular Genetics, Clinical and Imaging Features, and Therapeutics of Macular Dystrophies, Cone and Cone-Rod Dystrophies, Rod-Cone Dystrophies, Leber Congenital Amaurosis, and Cone Dysfunction Syndromes. Prog Retin Eye Res 2024, 100, 101244. [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; Bennett, J.; Wellman, J.A.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.-F.; Tillman, A.; Wittes, J.; Pappas, J.; Elci, O.; McCague, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Voretigene Neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) in Patients with RPE65-Mediated Inherited Retinal Dystrophy: A Randomised, Controlled, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 849–860. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, N.; Sundaresan, Y.; Gopalakrishnan, P.; Beryozkin, A.; Hanany, M.; Levanon, E.Y.; Banin, E.; Ben-Aroya, S.; Sharon, D. Inherited Retinal Diseases: Linking Genes, Disease-Causing Variants, and Relevant Therapeutic Modalities. Prog Retin Eye Res 2022, 89, 101029. [CrossRef]

- Abu Elasal, M.; Mousa, S.; Salameh, M.; Blumenfeld, A.; Khateb, S.; Banin, E.; Sharon, D. Genetic Analysis of 252 Index Cases with Inherited Retinal Diseases Using a Panel of 351 Retinal Genes. Genes (Basel) 2024, 15, 926. [CrossRef]

- Branham, K.; Samarakoon, L.; Audo, I.; Ayala, A.R.; Cheetham, J.K.; Daiger, S.P.; Dhooge, P.; Duncan, J.L.; Durham, T.A.; Fahim, A.T.; et al. Characterizing the Genetic Basis for Inherited Retinal Disease: Lessons Learned From the Foundation Fighting Blindness Clinical Consortium’s Gene Poll. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2025, 66, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rubanyi, G.M. The Future of Human Gene Therapy. Mol Aspects Med 2001, 22, 113–142. [CrossRef]

- Burnight, E.R.; Giacalone, J.C.; Cooke, J.A.; Thompson, J.R.; Bohrer, L.R.; Chirco, K.R.; Drack, A.V.; Fingert, J.H.; Worthington, K.S.; Wiley, L.A.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Engineering: Treating Inherited Retinal Degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res 2018, 65, 28–49. [CrossRef]

- Chew, L.A.; Iannaccone, A. Gene-Agnostic Approaches to Treating Inherited Retinal Degenerations. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1177838. [CrossRef]

- John, M.C.; Quinn, J.; Hu, M.L.; Cehajic-Kapetanovic, J.; Xue, K. Gene-Agnostic Therapeutic Approaches for Inherited Retinal Degenerations. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 15, 1068185. [CrossRef]

- Orkin, S.H.; Reilly, P. MEDICINE. Paying for Future Success in Gene Therapy. Science 2016, 352, 1059–1061. [CrossRef]

- Arango-Gonzalez, B.; Trifunović, D.; Sahaboglu, A.; Kranz, K.; Michalakis, S.; Farinelli, P.; Koch, S.; Koch, F.; Cottet, S.; Janssen-Bienhold, U.; et al. Identification of a Common Non-Apoptotic Cell Death Mechanism in Hereditary Retinal Degeneration. PLoS One 2014, 9, e112142. [CrossRef]

- Tolone, A.; Sen, M.; Chen, Y.; Ueffing, M.; Arango-Gonzalez, B.; Paquet-Durand, F. Pathomechanisms of Inherited Retinal Degeneration and Perspectives for Neuroprotection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2023, 13, a041310. [CrossRef]

- Tombran-Tink, J.; Barnstable, C.J. PEDF: A Multifaceted Neurotrophic Factor. Nat Rev Neurosci 2003, 4, 628–636. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Subramanian, P.; Shen, D.; Tuo, J.; Becerra, S.P.; Chan, C.-C. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor Reduces Apoptosis and pro-Inflammatory Cytokine Gene Expression in a Murine Model of Focal Retinal Degeneration. ASN Neuro 2013, 5, e00126. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pinto, A.; Polato, F.; Subramanian, P.; Rocha-Muñoz, A. de la; Vitale, S.; de la Rosa, E.J.; Becerra, S.P. PEDF Peptides Promote Photoreceptor Survival in Rd10 Retina Models. Exp Eye Res 2019, 184, 24–29. [CrossRef]

- Holekamp, N.M.; Bouck, N.; Volpert, O. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor Is Deficient in the Vitreous of Patients with Choroidal Neovascularization Due to Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol 2002, 134, 220–227. [CrossRef]

- Ogata, N.; Matsuoka, M.; Imaizumi, M.; Arichi, M.; Matsumura, M. Decrease of Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor in Aqueous Humor with Increasing Age. Am J Ophthalmol 2004, 137, 935–936. [CrossRef]

- Rebustini, I.T.; Crawford, S.E.; Becerra, S.P. PEDF Deletion Induces Senescence and Defects in Phagocytosis in the RPE. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 7745. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, T.S.; Adsersen, R.L.; Askou, A.L.; Corydon, T.J. Functional Roles of Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor in Retinal Degenerative and Vascular Disorders: A Scoping Review. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2024, 65, 41. [CrossRef]

- Brook, N.; Brook, E.; Dharmarajan, A.; Chan, A.; Dass, C.R. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor Regulation of Neuronal and Stem Cell Fate. Exp Cell Res 2020, 389, 111891. [CrossRef]

- Comitato, A.; Subramanian, P.; Turchiano, G.; Montanari, M.; Becerra, S.P.; Marigo, V. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor Hinders Photoreceptor Cell Death by Reducing Intracellular Calcium in the Degenerating Retina. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9, 560. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, Y.; Ikeda, Y.; Yonemitsu, Y.; Onimaru, M.; Nakagawa, K.; Kohno, R.; Miyazaki, M.; Hisatomi, T.; Nakamura, M.; Yabe, T.; et al. Inhibition of Nuclear Translocation of Apoptosis-Inducing Factor Is an Essential Mechanism of the Neuroprotective Activity of Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor in a Rat Model of Retinal Degeneration. Am J Pathol 2008, 173, 1326–1338. [CrossRef]

- Michelis, G.; German, O.L.; Villasmil, R.; Soto, T.; Rotstein, N.P.; Politi, L.; Becerra, S.P. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF) and Derived Peptides Promote Survival and Differentiation of Photoreceptors and Induce Neurite-Outgrowth in Amacrine Neurons. J Neurochem 2021, 159, 840–856. [CrossRef]

- Pagan-Mercado, G.; Becerra, S.P. Signaling Mechanisms Involved in PEDF-Mediated Retinoprotection. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019, 1185, 445–449. [CrossRef]

- Polato, F.; Becerra, S.P. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor, a Protective Factor for Photoreceptors in Vivo. Adv Exp Med Biol 2016, 854, 699–706. [CrossRef]

- Ortín-Martínez, A.; Valiente-Soriano, F.J.; García-Ayuso, D.; Alarcón-Martínez, L.; Jiménez-López, M.; Bernal-Garro, J.M.; Nieto-López, L.; Nadal-Nicolás, F.M.; Villegas-Pérez, M.P.; Wheeler, L.A.; et al. A Novel in Vivo Model of Focal Light Emitting Diode-Induced Cone-Photoreceptor Phototoxicity: Neuroprotection Afforded by Brimonidine, BDNF, PEDF or bFGF. PLoS One 2014, 9, e113798. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Polato, F.; Samardzija, M.; Abu-Asab, M.; Grimm, C.; Crawford, S.E.; Becerra, S.P. PEDF Deficiency Increases the Susceptibility of Rd10 Mice to Retinal Degeneration. Experimental Eye Research 2020, 198, 108121. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Geng, H.; Li, L.; Li, J.; Cheng, B.; Ma, X.; Li, H.; Hou, L. Photoreceptor Degeneration in Microphthalmia (Mitf) Mice: Partial Rescue by Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor. Dis Model Mech 2019, 12, dmm035642. [CrossRef]

- Bernardo-Colón, A.; Bighinati, A.; Parween, S.; Debnath, S.; Piano, I.; Adani, E.; Corsi, F.; Gargini, C.; Vergara, N.; Marigo, V.; et al. H105A Peptide Eye Drops Promote Photoreceptor Survival in Murine and Human Models of Retinal Degeneration. Commun Med (Lond) 2025, 5, 81. [CrossRef]

- Vigneswara, V.; Esmaeili, M.; Deer, L.; Berry, M.; Logan, A.; Ahmed, Z. Eye Drop Delivery of Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor-34 Promotes Retinal Ganglion Cell Neuroprotection and Axon Regeneration. Mol Cell Neurosci 2015, 68, 212–221. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Q.; Park, K.; Zhou, K.; Wassel, D.; Farjo, R.; Criswell, T.; Ma, J.-X.; Zhang, Y. Sustained Therapeutic Effect of an Anti-Inflammatory Peptide Encapsulated in Nanoparticles on Ocular Vascular Leakage in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 1049678. [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Cui, B.; Xing, M.; Chen, S.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, D.; Guo, Y.; Du, M.; Wang, X.; Zhou, D.; et al. Stable Inhibition of Choroidal Neovascularization by Adeno-Associated Virus 2/8-Vectored Bispecific Molecules. Gene Ther 2024, 31, 511–523. [CrossRef]

- Valiente-Soriano, F.J.; Di Pierdomenico, J.; García-Ayuso, D.; Ortín-Martínez, A.; Miralles de Imperial-Ollero, J.A.; Gallego-Ortega, A.; Jiménez-López, M.; Villegas-Pérez, M.P.; Becerra, S.P.; Vidal-Sanz, M. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF) Fragments Prevent Mouse Cone Photoreceptor Cell Loss Induced by Focal Phototoxicity In Vivo. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 7242. [CrossRef]

- Imai, D.; Yoneya, S.; Gehlbach, P.L.; Wei, L.L.; Mori, K. Intraocular Gene Transfer of Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor Rescues Photoreceptors from Light-Induced Cell Death. J Cell Physiol 2005, 202, 570–578. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Yonemitsu, Y.; Miyazaki, M.; Kohno, R.; Murakami, Y.; Murata, T.; Goto, Y.; Tabata, T.; Ueda, Y.; Ono, F.; et al. Acute Toxicity Study of a Simian Immunodeficiency Virus-Based Lentiviral Vector for Retinal Gene Transfer in Nonhuman Primates. Human Gene Therapy 2009, 20, 943–954. [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, M.; Ikeda, Y.; Yonemitsu, Y.; Goto, Y.; Sakamoto, T.; Tabata, T.; Ueda, Y.; Hasegawa, M.; Tobimatsu, S.; Ishibashi, T.; et al. Simian Lentiviral Vector-Mediated Retinal Gene Transfer of Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor Protects Retinal Degeneration and Electrical Defect in Royal College of Surgeons Rats. Gene Ther 2003, 10, 1503–1511. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Goto, Y.; Yonemitsu, Y.; Miyazaki, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Ishibashi, T.; Tabata, T.; Ueda, Y.; Hasegawa, M.; Tobimatsu, S.; et al. Simian Immunodeficiency Virus-Based Lentivirus Vector for Retinal Gene Transfer: A Preclinical Safety Study in Adult Rats. Gene Ther 2003, 10, 1161–1169. [CrossRef]

- Stable Retinal Gene Expression in Nonhuman Primates via Subretinal Injection of SIVagm-Based Lentiviral Vectors | Human Gene Therapy Available online: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/hum.2009.009 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Rasmussen, H.; Chu, K.W.; Campochiaro, P.; Gehlbach, P.L.; Haller, J.A.; Handa, J.T.; Nguyen, Q.D.; Sung, J.U. Clinical Protocol. An Open-Label, Phase I, Single Administration, Dose-Escalation Study of ADGVPEDF.11D (ADPEDF) in Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD). Hum Gene Ther 2001, 12, 2029–2032.

- Hisai, T.; Murakami, Y.; Kusano, K.; Kobayakawa, Y.; Ikeda, Y. Phase 1/2a Clinical Trial Protocol for Lentiviral Vector-Based Retinal Gene Therapy to Slow the Progression of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Methods Mol Biol 2026, 2974, 239–248. [CrossRef]

- Warner, E.F.; Vaux, L.; Boyd, K.; Widdowson, P.S.; Binley, K.M.; Osborne, A. Ocular Delivery of Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF) as a Neuroprotectant for Geographic Atrophy. Aging Dis 2024, 15, 2003–2007. [CrossRef]

- Cayouette, M.; Smith, S.B.; Becerra, S.P.; Gravel, C. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor Delays the Death of Photoreceptors in Mouse Models of Inherited Retinal Degenerations. Neurobiol Dis 1999, 6, 523–532. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, J.; Fariss, R.N.; Campos, M.M.; Robison, W.G.; Kim, H.; Lutz, R.; Becerra, S.P. Transscleral-RPE Permeability of PEDF and Ovalbumin Proteins: Implications for Subconjunctival Protein Delivery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005, 46, 4383–4392. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.-H.; Zhan, W.; Gallagher, T.L.; Gao, G. Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus as a Delivery Platform for Ocular Gene Therapy: A Comprehensive Review. Mol Ther 2024, 32, 4185–4207. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, F.; Arsenijevic, Y. Precision Gene Therapy: Tailoring rAAV-Mediated Gene Therapies for Inherited Retinal Dystrophies (IRDs). Mol Aspects Med 2025, 106, 101424. [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.D.; Nusinowitz, S.; Chao, K.; Yu, F.; Bok, D.; Yang, X.-J. CNTF-Mediated Protection of Photoreceptors Requires Initial Activation of the Cytokine Receptor Gp130 in Müller Glial Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, E4520-4529. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, W.M.; Wang, Q.; Tzekova, R.; Wiegand, S.J. Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor and Stress Stimuli Activate the Jak-STAT Pathway in Retinal Neurons and Glia. J Neurosci 2000, 20, 4081–4090. [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Cojocaru, R.I.; Dudley, V.J.; Brooks, M.; Swaroop, A.; Sarthy, V.P. Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Induces Genes Associated with Inflammation and Gliosis in the Retina: A Gene Profiling Study of Flow-Sorted, Müller Cells. PLoS One 2011, 6, e20326. [CrossRef]

- Cayouette, M.; Behn, D.; Sendtner, M.; Lachapelle, P.; Gravel, C. Intraocular Gene Transfer of Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Prevents Death and Increases Responsiveness of Rod Photoreceptors in the Retinal Degeneration Slow Mouse. J Neurosci 1998, 18, 9282–9293. [CrossRef]

- Cayouette, M.; Gravel, C. Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Transfer of Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Can Prevent Photoreceptor Degeneration in the Retinal Degeneration (Rd) Mouse. Hum Gene Ther 1997, 8, 423–430. [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Wen, R.; Goddard, M.B.; Sherman, S.D.; O’Rourke, P.J.; Stabila, P.F.; Bell, W.J.; Dean, B.J.; Kauper, K.A.; Budz, V.A.; et al. Encapsulated Cell-Based Delivery of CNTF Reduces Photoreceptor Degeneration in Animal Models of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002, 43, 3292–3298.

- l.ferguson@neurotechusa.com Neurotech’s ENCELTOTM (Revakinagene Taroretcel-Lwey) Approved by the FDA for the Treatment of Adults with Idiopathic Macular Telangiectasia Type 2 (MacTel) Available online: https://www.neurotechpharmaceuticals.com/neurotechs-enceltotm-revakinagene-taroretcel-lwey-approved-by-the-fda-for-the-treatment-of-macular-telangiectasia-type-2-mactel/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Chew, E.Y.; Gillies, M.; Jaffe, G.J.; Gaudric, A.; Egan, C.; Constable, I.; Clemons, T.; Aaberg, T.; Manning, D.C.; Hohman, T.C.; et al. Cell-Based Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Therapy for Macular Telangiectasia Type 2. NEJM Evidence 2025, 4, EVIDoa2400481. [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.G.; Weleber, R.G.; Duncan, J.L.; Jaffe, G.J.; Tao, W.; Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Retinitis Pigmentosa Study Groups Randomized Trial of Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Delivered by Encapsulated Cell Intraocular Implants for Retinitis Pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol 2013, 156, 283-292.e1. [CrossRef]

- Birch, D.G.; Bennett, L.D.; Duncan, J.L.; Weleber, R.G.; Pennesi, M.E. Long-Term Follow-up of Patients With Retinitis Pigmentosa Receiving Intraocular Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Implants. Am J Ophthalmol 2016, 170, 10–14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Hopkins, J.J.; Heier, J.S.; Birch, D.G.; Halperin, L.S.; Albini, T.A.; Brown, D.M.; Jaffe, G.J.; Tao, W.; Williams, G.A. Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Delivered by Encapsulated Cell Intraocular Implants for Treatment of Geographic Atrophy in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 6241–6245. [CrossRef]

- Aït-Ali, N.; Fridlich, R.; Millet-Puel, G.; Clérin, E.; Delalande, F.; Jaillard, C.; Blond, F.; Perrocheau, L.; Reichman, S.; Byrne, L.C.; et al. Rod-Derived Cone Viability Factor Promotes Cone Survival by Stimulating Aerobic Glycolysis. Cell 2015, 161, 817–832. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, L.C.; Dalkara, D.; Luna, G.; Fisher, S.K.; Clérin, E.; Sahel, J.-A.; Léveillard, T.; Flannery, J.G. Viral-Mediated RdCVF and RdCVFL Expression Protects Cone and Rod Photoreceptors in Retinal Degeneration. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 105–116. [CrossRef]

- Marie, M.; Churet, L.; Gautron, A.-S.; Farjo, R.; Mizuyoshi, K.; Stevenson, V.; Khabou, H.; Léveillard, T.; Sahel, J.-A.; Lorget, F. Preclinical Safety and Biodistribution of SPVN06, a Novel Gene- and Mutation-Independent Gene Therapy for Rod-Cone Dystrophies. Gene Ther 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Chaffiol, A.; Kole, C.; Yang, Y.; Millet-Puel, G.; Clérin, E.; Aït-Ali, N.; Bennett, J.; Dalkara, D.; Sahel, J.-A.; et al. The Thioredoxin Encoded by the Rod-Derived Cone Viability Factor Gene Protects Cone Photoreceptors Against Oxidative Stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 2016, 24, 909–923. [CrossRef]

- Noel, J.; Jalligampala, A.; Marussig, M.; Vinot, P.-A.; Marie, M.; Butler, M.; Lorget, F.; Boissel, S.; Leveillard, T.D.; Sahel, J.A.; et al. SPVN06, a Novel Mutation-Independent AAV-Based Gene Therapy, Protects Cone Degeneration in a Pig Model of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 1189–1189.

- Audo, I.; Barale, P.-O.; Everett, L.A.; Lauer, A.K.; Martel, J.N.; Blouin, L.; Gautron, A.-S.; Messeca, N.; Loustalot, F.; Meur, A.L.; et al. PRODYGY: A First-in-Human Trial of Rod-Derived Cone Viability Factor (RdCVF) Gene Therapy in Subjects with Rod-Cone Dystrophy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 1442–1442.

- Abed, E.; Corbo, G.; Falsini, B. Neurotrophin Family Members as Neuroprotectants in Retinal Degenerations. BioDrugs 2015, 29, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Okoye, G.; Zimmer, J.; Sung, J.; Gehlbach, P.; Deering, T.; Nambu, H.; Hackett, S.; Melia, M.; Esumi, N.; Zack, D.J.; et al. Increased Expression of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Preserves Retinal Function and Slows Cell Death from Rhodopsin Mutation or Oxidative Damage. J Neurosci 2003, 23, 4164–4172. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, A.; Namekata, K.; Guo, X.; Harada, C.; Harada, T. Neuroprotection, Growth Factors and BDNF-TrkB Signalling in Retinal Degeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2016, 17, 1584. [CrossRef]

- Osborne, A.; Khatib, T.Z.; Songra, L.; Barber, A.C.; Hall, K.; Kong, G.Y.X.; Widdowson, P.S.; Martin, K.R. Neuroprotection of Retinal Ganglion Cells by a Novel Gene Therapy Construct That Achieves Sustained Enhancement of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor/Tropomyosin-Related Kinase Receptor-B Signaling. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9, 1007. [CrossRef]

- Osborne, A.; Khatib, T.Z.; Whitehead, M.; Mensah, T.; Yazdouni, S.; Nieuwenhuis, B.; Ali, Z.; Ching, J.; Watt, R.; Kishi, N.; et al. Dose-Ranging and Further Therapeutic Evaluation of a Bicistronic Humanized TrkB-BDNF Gene Therapy for Glaucoma in Rodents. Mol Neurodegener Adv 2025, 1, 3. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yin, X.; Wu, L.; Huang, D.; Wang, Z.; Wu, F.; Jiang, J.; Chen, G.; Wang, Q. High-Efficiency Ocular Delivery of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Oligomycin for Neuroprotection in Glaucoma. Adv Mater 2025, 37, e2500623. [CrossRef]

- Di Pierdomenico, J.; Scholz, R.; Valiente-Soriano, F.J.; Sánchez-Migallón, M.C.; Vidal-Sanz, M.; Langmann, T.; Agudo-Barriuso, M.; García-Ayuso, D.; Villegas-Pérez, M.P. Neuroprotective Effects of FGF2 and Minocycline in Two Animal Models of Inherited Retinal Degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018, 59, 4392–4403. [CrossRef]

- Rana, D.; Dhankhar, S.; Chauhan, R.; Saini, M.; Singh, R.; Kumar, P.; Singh, T.G.; Chauhan, S.; Devi, S. Targeting Neurotrophic Dysregulation in Diabetic Retinopathy: A Novel Therapeutic Avenue. Mol Biol Rep 2025, 52, 570. [CrossRef]

- Arranz-Romera, A.; Hernandez, M.; Checa-Casalengua, P.; Garcia-Layana, A.; Molina-Martinez, I.T.; Recalde, S.; Young, M.J.; Tucker, B.A.; Herrero-Vanrell, R.; Fernandez-Robredo, P.; et al. A Safe GDNF and GDNF/BDNF Controlled Delivery System Improves Migration in Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells and Survival in Retinal Ganglion Cells: Potential Usefulness in Degenerative Retinal Pathologies. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14, 50. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cruz, A.; Hernández-Pinto, A.; Lillo, C.; Isiegas, C.; Marchena, M.; Lizasoain, I.; Bosch, F.; de la Villa, P.; Hernández-Sánchez, C.; de la Rosa, E.J. Insulin Receptor Activation by Proinsulin Preserves Synapses and Vision in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Cell Death Dis 2022, 13, 383. [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.W.; Wubben, T.J.; Zacks, D.N. Promising Therapeutic Targets for Neuroprotection in Retinal Disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2025, 36, 247–252. [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.; Compagnoni, C.; Cordeiro, M.F. Investigational Neuroprotective Compounds in Clinical Trials for Retinal Disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2021, 30, 571–577. [CrossRef]

- Lenis, T.L.; Sarfare, S.; Jiang, Z.; Lloyd, M.B.; Bok, D.; Radu, R.A. Complement Modulation in the Retinal Pigment Epithelium Rescues Photoreceptor Degeneration in a Mouse Model of Stargardt Disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 3987–3992. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Pauer, G.J.; Hagstrom, S.A.; Bok, D.; DeBenedictis, M.J.; Bonilha, V.L.; Hollyfield, J.G.; Radu, R.A. Evidence of Complement Dysregulation in Outer Retina of Stargardt Disease Donor Eyes. Redox Biol 2020, 37, 101787. [CrossRef]

- Silverman, S.M.; Ma, W.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L.; Wong, W.T. C3- and CR3-Dependent Microglial Clearance Protects Photoreceptors in Retinitis Pigmentosa. J Exp Med 2019, 216, 1925–1943. [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Mastellos, D.C.; Li, Y.; Dunaief, J.L.; Lambris, J.D. Targeting Complement Components C3 and C5 for the Retina: Key Concepts and Lingering Questions. Prog Retin Eye Res 2021, 83, 100936. [CrossRef]

- de Jong, S.; Tang, J.; Clark, S.J. Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Disease of Extracellular Complement Amplification. Immunol Rev 2023, 313, 279–297. [CrossRef]

- Armento, A.; Ueffing, M.; Clark, S.J. The Complement System in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 4487–4505. [CrossRef]

- Akula, M.; McNamee, S.M.; Love, Z.; Nasraty, N.; Chan, N.P.M.; Whalen, M.; Avola, M.O.; Olivares, A.M.; Leehy, B.D.; Jelcick, A.S.; et al. Retinoic Acid Related Orphan Receptor α Is a Genetic Modifier That Rescues Retinal Degeneration in a Mouse Model of Stargardt Disease and Dry AMD. Gene Ther 2024, 31, 413–421. [CrossRef]

- Kassa, E.; Ciulla, T.A.; Hussain, R.M.; Dugel, P.U. Complement Inhibition as a Therapeutic Strategy in Retinal Disorders. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2019, 19, 335–342. [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.M.; Ciulla, T.A.; Berrocal, A.M.; Gregori, N.Z.; Flynn, H.W.; Lam, B.L. Stargardt Macular Dystrophy and Evolving Therapies. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2018, 18, 1049–1059. [CrossRef]

- West, E.E.; Woodruff, T.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Kemper, C. Complement in Human Disease: Approved and up-and-Coming Therapeutics. Lancet 2024, 403, 392–405. [CrossRef]

- Katschke, K.J.; Xi, H.; Cox, C.; Truong, T.; Malato, Y.; Lee, W.P.; McKenzie, B.; Arceo, R.; Tao, J.; Rangell, L.; et al. Classical and Alternative Complement Activation on Photoreceptor Outer Segments Drives Monocyte-Dependent Retinal Atrophy. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 7348. [CrossRef]

- Astellas Pharma Global Development, Inc. A Phase 2b Randomized, Double-Masked, Controlled Trial to Establish the Safety and Efficacy of ZimuraTM (Complement C5 Inhibitor) Compared to Sham in Subjects With Autosomal Recessive Stargardt Disease; clinicaltrials.gov, 2025;

- Annamalai, B.; Parsons, N.; Nicholson, C.; Obert, E.; Jones, B.; Rohrer, B. Subretinal Rather Than Intravitreal Adeno-Associated Virus-Mediated Delivery of a Complement Alternative Pathway Inhibitor Is Effective in a Mouse Model of RPE Damage. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2021, 62, 11. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar-Schäfer, I.; Wang, L.; Krohne, T.U.; Xu, H.; Langmann, T. Modulation of Three Key Innate Immune Pathways for the Most Common Retinal Degenerative Diseases. EMBO Mol Med 2018, 10, e8259. [CrossRef]

- Guymer, R.H.; Campbell, T.G. Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Lancet 2023, 401, 1459–1472. [CrossRef]

- Maneu, V.; Lax, P.; De Diego, A.M.G.; Cuenca, N.; García, A.G. Combined Drug Triads for Synergic Neuroprotection in Retinal Degeneration. Biomed Pharmacother 2022, 149, 112911. [CrossRef]

- Comitato, A.; Schiroli, D.; La Marca, C.; Marigo, V. Differential Contribution of Calcium-Activated Proteases and ER-Stress in Three Mouse Models of Retinitis Pigmentosa Expressing P23H Mutant RHO. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019, 1185, 311–316. [CrossRef]

- Kutluer, M.; Huang, L.; Marigo, V. Targeting Molecular Pathways for the Treatment of Inherited Retinal Degeneration. Neural Regen Res 2020, 15, 1784–1791. [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, I.; Maneu, V.; Campello, L.; Fernández-Sánchez, L.; Martínez-Gil, N.; Kutsyr, O.; Sánchez-Sáez, X.; Sánchez-Castillo, C.; Lax, P.; Cuenca, N. Inherited Retinal Dystrophies: Role of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Their Physiopathology and Therapeutic Implications. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11, 1086. [CrossRef]

- Olivares-González, L.; Velasco, S.; Campillo, I.; Rodrigo, R. Retinal Inflammation, Cell Death and Inherited Retinal Dystrophies. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 2096. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Yan, J.; Yang, M.; Xu, W.; Hu, Z.; Paquet-Durand, F.; Jiao, K. Inherited Retinal Degeneration: Towards the Development of a Combination Therapy Targeting Histone Deacetylase, Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase, and Calpain. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 581. [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.M.; Johnson, L.E.; Ahuja, S.; Ekström, P. a. R.; Romero, J.; van Veen, T. Significant Photoreceptor Rescue by Treatment with a Combination of Antioxidants in an Animal Model for Retinal Degeneration. Neuroscience 2007, 145, 1120–1129. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yao, J.; Jia, L.; Kocab, A.J.; Zacks, D.N. Neuroprotection of Photoreceptors by Combined Inhibition of Both Fas and Autophagy Pathways in P23H Mice. Cell Death Dis 2025, 16, 469. [CrossRef]

- Martinez Velazquez, L.A.; Ballios, B.G. The Next Generation of Molecular and Cellular Therapeutics for Inherited Retinal Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 11542. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.X.; Wang, J.J.; Gao, G.; Shao, C.; Mott, R.; Ma, J. Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor (PEDF) Is an Endogenous Antiinflammatory Factor. FASEB J 2006, 20, 323–325. [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Jin, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, K.; Ma, J. Overexpression of Pigment Epithelium-Derived Factor Inhibits Retinal Inflammation and Neovascularization. Am J Pathol 2011, 178, 688–698. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Singh, N.K. The Role of Inflammation in Retinal Neurodegeneration and Degenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 23, 386. [CrossRef]

- Kanan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bernardo-Colón, A.; Debnath, S.; Khan, M.; Becerra, S.P.; Campochiaro, P.A. Rabbit Model of Oxidative Stress-Induced Retinal Degeneration. Free Radic Biol Med 2025, 231, 48–56. [CrossRef]

- Campochiaro, P.A.; Iftikhar, M.; Hafiz, G.; Akhlaq, A.; Tsai, G.; Wehling, D.; Lu, L.; Wall, G.M.; Singh, M.S.; Kong, X. Oral N-Acetylcysteine Improves Cone Function in Retinitis Pigmentosa Patients in Phase I Trial. J Clin Invest 2020, 130, 1527–1541. [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Hafiz, G.; Wehling, D.; Akhlaq, A.; Campochiaro, P.A. Locus-Level Changes in Macular Sensitivity in Patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa Treated with Oral N-Acetylcysteine. Am J Ophthalmol 2021, 221, 105–114. [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Ramzan, F.; Tayyab, H.; Damji, K.F. Rekindling Vision: Innovative Strategies for Treating Retinal Degeneration. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 4078. [CrossRef]

- Leinonen, H.; Zhang, J.; Occelli, L.M.; Seemab, U.; Choi, E.H.; L P Marinho, L.F.; Querubin, J.; Kolesnikov, A.V.; Galinska, A.; Kordecka, K.; et al. A Combination Treatment Based on Drug Repurposing Demonstrates Mutation-Agnostic Efficacy in Pre-Clinical Retinopathy Models. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 5943. [CrossRef]

- Zuzic, M.; Striebel, J.; Pawlick, J.S.; Sharma, K.; Holz, F.G.; Busskamp, V. Gene-Independent Therapeutic Interventions to Maintain and Restore Light Sensitivity in Degenerating Photoreceptors. Prog Retin Eye Res 2022, 90, 101065. [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Raji, S.; Cehajic Kapetanovic, J. Visualising Treatment Effects in Low-Vision Settings: Proven and Potential Endpoints for Clinical Trials of Inherited Retinal Disease Therapies. Gene Ther 2025. [CrossRef]

- Guidelines on Clinical Assessment of Patients with Inherited Retinal Degenerations - 2022 Available online: https://www.aao.org/education/clinical-statement/guidelines-on-clinical-assessment-of-patients-with (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- PaVe-GT Available online: https://pave-gt.ncats.nih.gov (accessed on 27 December 2025).

| Therapeutic Factor | Category | Key Mechanism of Action | Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEDF | Neuroprotection | Neurotrophic, anti-angiogenic, and anti-inflammatory properties; protects photoreceptors via suppression of apoptotic pathways | Preclinical |

| CNTF | Neuroprotection | Activates neuroprotective signaling via STAT3 pathway; promotes photoreceptor survival | FDA Approved (Encelto for MacTel Type 2) |

| RdCVF | Neuroprotection | Rod-secreted factor promoting cone survival; stimulates aerobic glycolysis in cones | Clinical trials |

| BDNF | Neuroprotection | Promotes neuronal survival via TrkB receptor signaling; supports photoreceptor viability | Preclinical |

| FGF | Neuroprotection | Multiple growth factors supporting retinal neuron survival and development | Preclinical |

| GDNF | Neuroprotection | Glial-derived factor promoting photoreceptor survival | Preclinical |

| Proinsulin | Neuroprotection | Activates survival pathways; reduces oxidative stress in photoreceptors | Preclinical |

| Complement C3 inhibitors | Immunomodulation | Blocks complement cascade at C3 level; reduces inflammation and cell damage | Clinical trials (GA approved) |

| Complement C5 inhibitors | Immunomodulation | Inhibits terminal complement pathway; prevents membrane attack complex formation | Clinical trials (GA approved) |

| Soluble complement regulators | Immunomodulation | Gene therapy delivery of endogenous complement regulatory proteins | Preclinical/Early clinical |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.