1. Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of irreversible vision loss in people over 50 years old [

3]. Dry AMD, characterized by progressive retinal dysfunction and degeneration, lacks effective therapeutic interventions early in the disease, and no therapeutics currently in development for early and intermediate AMD are durable. Gene therapies offer a durable approach to treating chronic retinal degenerative diseases [

2]. One promising candidate for therapeutic intervention is BMI1, a gene encoding a polycomb ring finger protein that is essential for stem cell self-renewal and the repair of DNA damage in somatic cells [

5,

6,

7,

8]. The BMI1 protein is downregulated in retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells in aged and AMD maculas [

1,

2,

9].

BMI1 has shown protective effects in various tissues, including its role in mitigating oxidative stress and preserving cellular integrity [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], but its potential in retinal therapy remains unexplored. BMI1 has emerged as a critical factor in maintaining retinal homeostasis, promoting regenerative processes, and protecting against cellular damage [

5,

10]. The BMI1 gene has been identified as a key regulator of DNA damage repair and cellular self-renewal, making it a promising candidate for gene therapy [

11]. Restoring BMI1 expression protects RPE cells from oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, both of which are critical contributors to AMD progression. Furthermore, BMI1 is known to promote retinal cell survival and reduce inflammation by regulating p16INK4a/Rb and p19ARF/p53 [

12].

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of targeting oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in AMD, as these mechanisms are central to disease progression [

18,

19]. Stimulation of mitochondria has also demonstrated vision improvement and is the basis of FDA approval of the Valeda light therapy device. BMI1’s ability to regulate these pathways makes it a promising candidate for addressing the underlying pathology of dry AMD [

9,

20].

The NaIO₃ (sodium iodate)-induced retinal degeneration mouse model is widely used for studying oxidative stress-induced retinal degenerative diseases, especially dry AMD [

21,

22,

23]. The retinal changes in this model, including RPE atrophy and outer retinal degeneration, mirror those observed in advanced nonexudative AMD [

24,

25].

We aimed to evaluate the use of an AAV-based gene therapy strategy to deliver BMI1 to the retina of NaIO₃-induced dry AMD mice to mitigate structural and functional damage caused by AMD. The lack of effective treatments for dry AMD underscores the need for innovative therapeutic approaches. By targeting BMI1, we aim to address the unmet need for effective treatments for dry AMD and explore innovative therapeutic strategies. In this model, we induced severe photoreceptor loss with systemic NaIO₃ (40-50 mg/kg). We evaluated the ability of subretinal (SR) AAV5.BMI1 and suprachoroidal (SC) AAV8.BMI1 to mitigate retinal damage in two murine species (Balb/c and C57B/6) at early and late timepoints to assess durability of the therapeutic effects. The outer nuclear layer thickness (ONL), which contains photoreceptor cell bodies, was measured in all treatment groups, and is reduced in advanced nonexudative AMD when vision is lost.

2. Results

2.1. Confirmation of Sodium Iodate-Induced Retinal Damage and Phenotype in the Murine Model

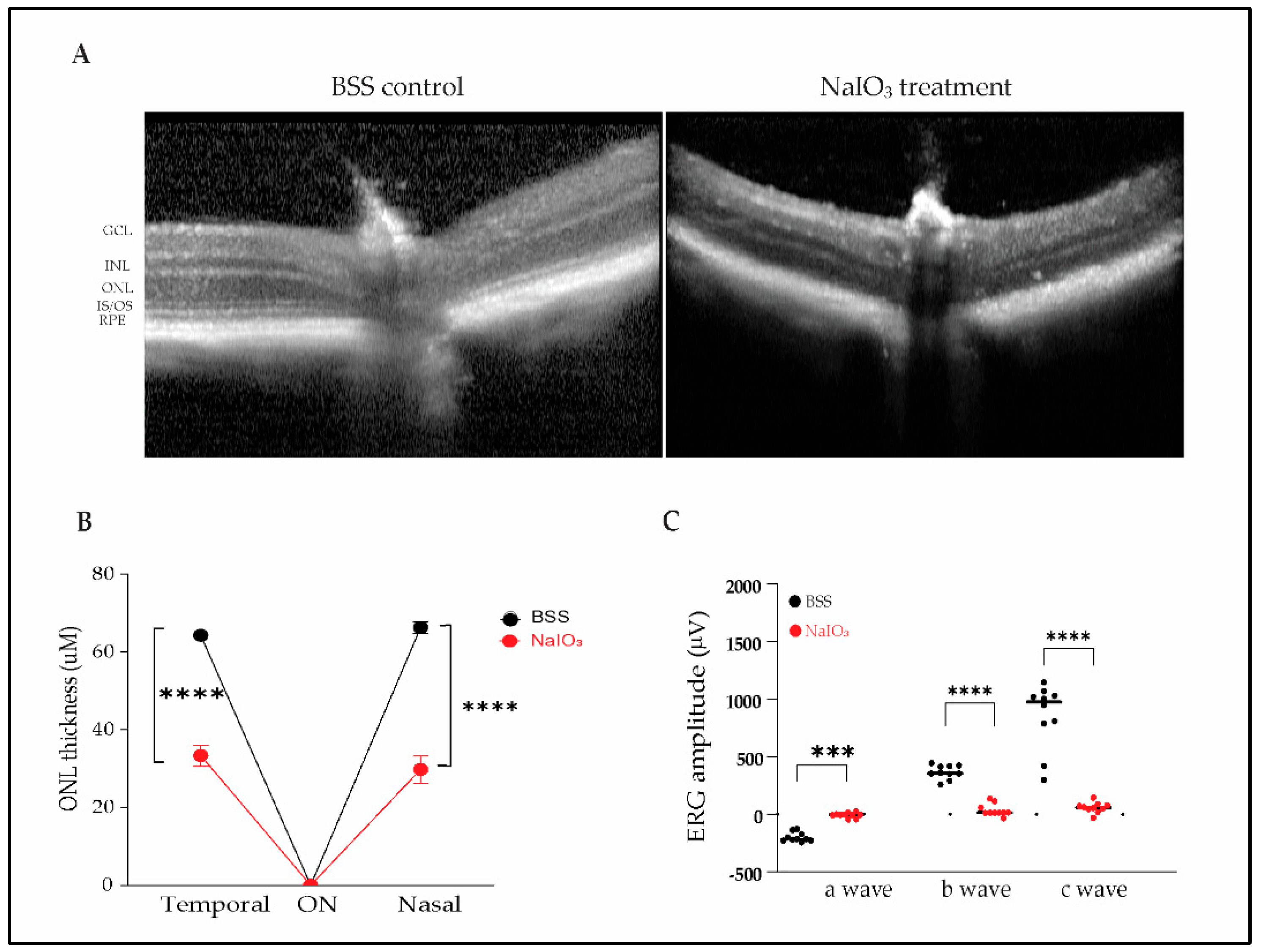

Intraperitoneal exposure to sodium iodate (40 and 50 mg/kg) results in RPE, ellipsoid zone, and ONL loss and complete loss of retinal function, as measured by ERG, by 1 month after injection. To capture retinal phenotypic changes, OCT images were acquired 4 weeks after systemic NaIO

3 injection. OCT images are shown in Fig 1A. BSS (balanced salt solution) control mice maintained outer retinal structure and layers. In contrast, NaIO₃-treated mice exhibited loss of IS/OS, RPE cells, and thinning of the ONL. As previously reported, quantitative analysis revealed significant thinning of the ONL in NaIO₃-treated mice compared to controls, with thickness reductions in the nasal (33.4 ± 8.7 µm vs. 66.3 ± 4.6 µm) and temporal (29.8 ± 10.9 µm vs. 64.3 ± 3.3 µm) regions (

Figure 1B).

To assess retinal functional changes, we performed ERG recordings 4 weeks post-NaIO3 treatment. A significant decrease in scotopic a-wave, photopic b-wave and c-wave amplitudes was observed (p<0.001), indicating impaired RPE, photoreceptor and bipolar cell function (Fig 1C). Function damage to the retina was very severe with this model, eliminating all ERG waves by the study endpoint. In this model, it is unlikely to demonstrate functional protection given the severity of the oxidative stress insult.

2.2. Durable Dose-Related Increase in Retinal BMI1 mRNA and Protein Levels

2.2.1. AAV5

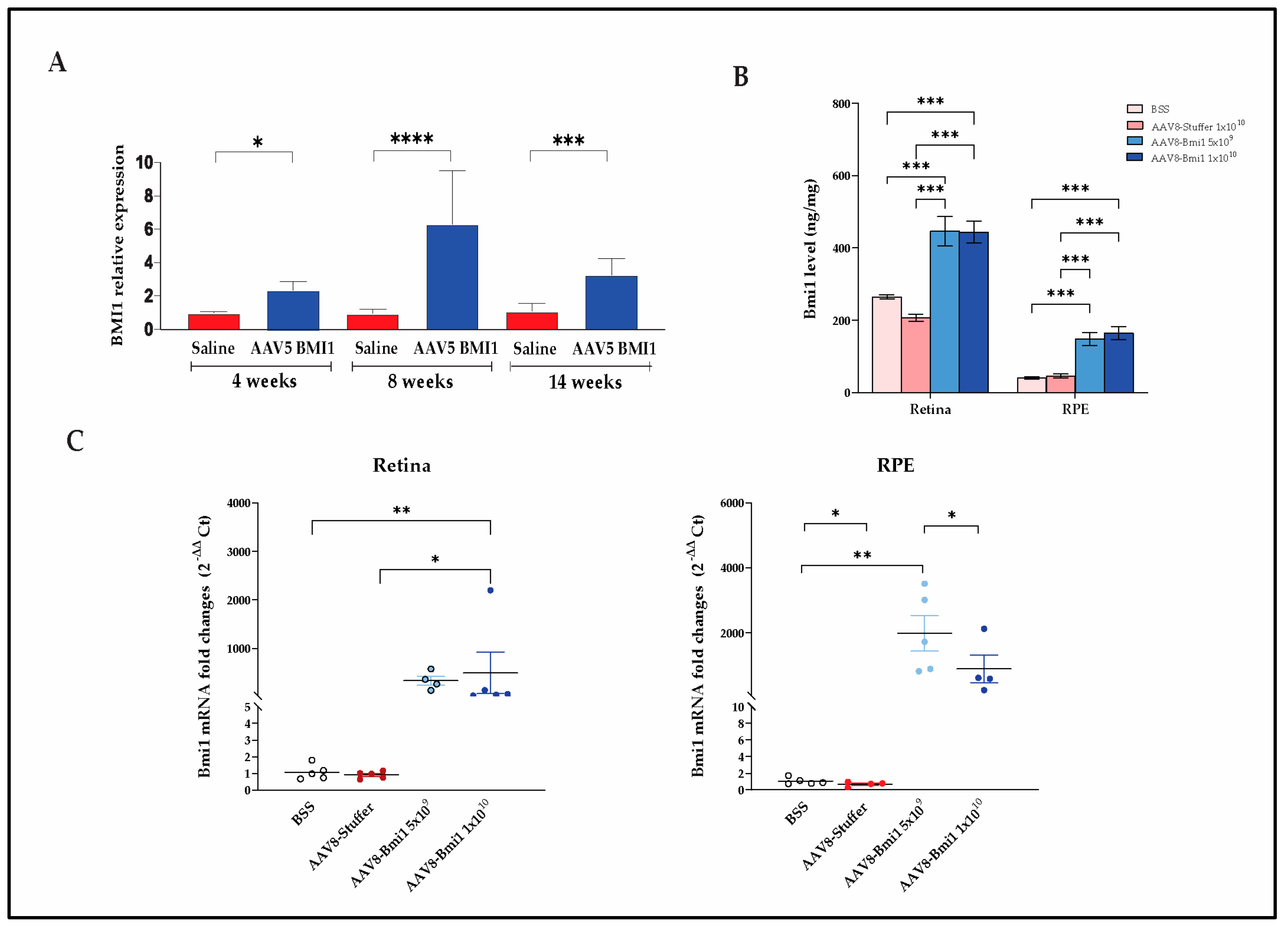

Bmi1 mRNA expression is significantly increased in murine RPE after AAV5.BMI1 injection (1 × 10

9 vg) compared to saline injected controls after 4, 8 and 14 wks. Values are expressed as mean ± SD. *

P value < 0.05, ***

P value < 0.001, ****

P value < 0.0001 (student’s t-test) (n=2-11 per group) (

Figure 2A). There was a trend toward increased BMI1 protein levels in the retinal tissues of AAV5.BMI1-treated eyes but significant variability among animals with SR injection (Data not shown).

2.2.2. AAV8

C57B6 mice received SC injections of BSS, AAV8.stuffer (1×1010 vg/eye) which lacks enhancer, promoter, splicing regulator, noncoding RNA, antisense sequence, or a coding sequence, or AAV8.BMI1 (5×10⁹ or 1×1010 vg/eye), followed by NaIO₃ 4 weeks later.

BMI1 expression levels in the retina and RPE were quantified using a validated electrochemiluminescence (ECL) assay (MSD). A significant increase in BMI1 protein levels was observed in AAV8.BMI1-treated mice at the 5×10

9 and 1×10

10 vg/eye doses compared to BSS and AAV8.stuffer controls (

Figure 2B).

After ocular tissue microdissection and RNA and protein extraction,

Bmi1 mRNA levels in the retina and RPE were assessed. Treatment with AAV8.BMI1 (1×10

10 vg/eye) significantly increased

Bmi1 mRNA expression in retina and RPE compared to control groups (

Figure 2C).

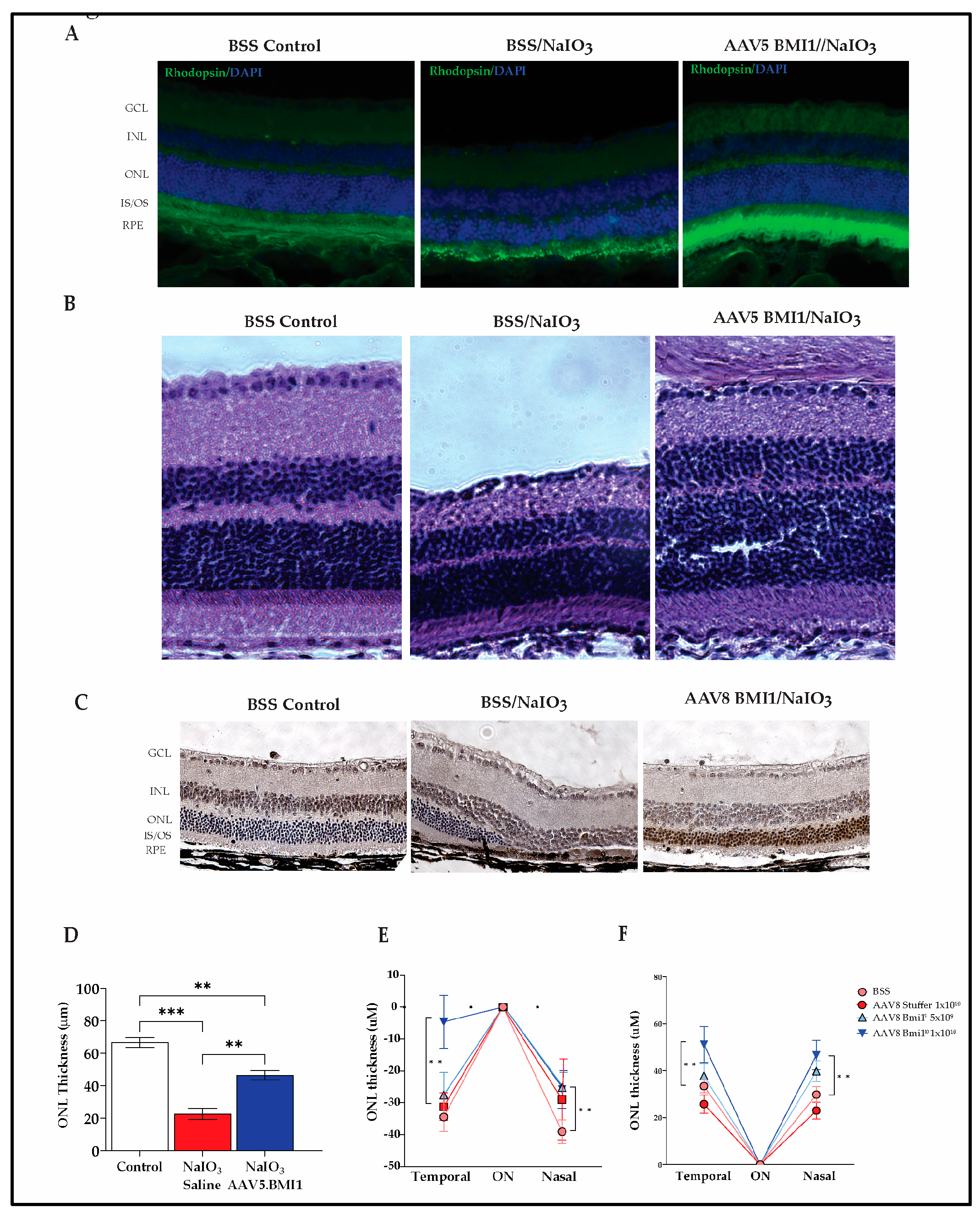

2.3. BMI1 Expression Preserves Photoreceptors and Retinal Structure

Our findings demonstrate that AAV5.BMI1 and AAV8.BMI1 prevent retinal damage and cell loss induced by NaIO

3. AAV5.BMI1 significantly increased rhodopsin expression (

Figure 3A), correlating to increased outer nuclear layer (ONL) thickness and preserved outer segment ultrastructure (

Figure 3B) 30 days post-AAV5.BMI1 injection and 3 days post-

NaIO₃ exposure.

AAV8.BMI1 treated mice exhibited robust nuclear BMI1 staining and preserved

ONL cells and

outer segments compared to controls after NaIO₃ exposure, confirming its expression in preserved photoreceptors (

Figure 3C).

To further address how AAV.BMI1 treatment affects retinal structure with NaIO

3-induced damage, OCT imaging was performed 4 weeks post-NaIO₃ injection. AAV5.BMI1 treatment preserved retinal structure, with significant retention of ONL thickness compared to controls (

Figure 3B and 3D). In contrast, NaIO₃-treated controls exhibited marked ONL thinning. A significant increase in ONL thickness was seen in both AAV5.BMI1 and AAV8.BMI1 treated animals compared to saline-treated controls (p<0.01) (

Figure 3D–F). BMI1 expression was seen with IHC in the preserved photoreceptors (

Figure 3C)

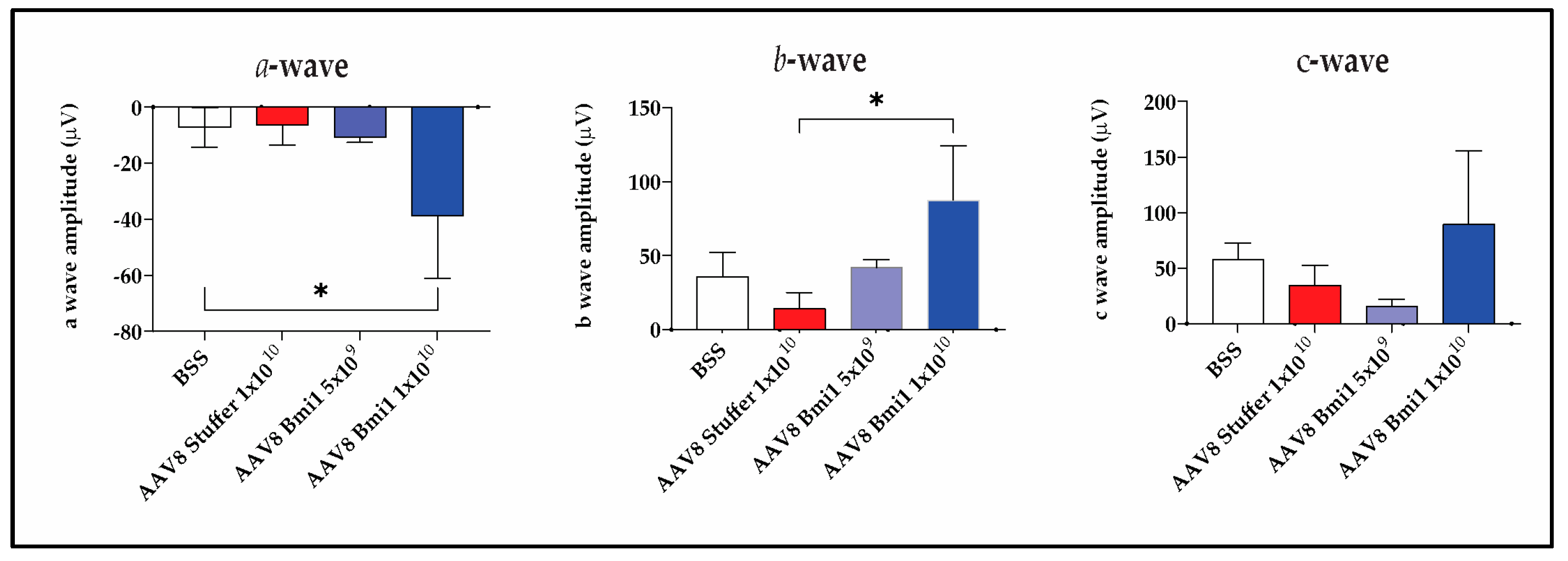

2.4. AAV8.BMI1 Treatment Prevents Functional Retinal Damage from Sodium Iodate

Given the known reduction in ERG amplitudes with SR injection, ERGs were not measured in the AAV5.BMI1 SR study. SC injection does not cause a significant change in ERG waves in mice, and therefore ERGs were measured in the AAV8.BMI1 SC study. To examine changes in retinal function associated with AAV8.BMI1 treatment, ERGs were collected at baseline and 4-weeks after systemic oxidative stress. Analyses demonstrated that AAV8.BMI1 treatment improved retinal function with significantly higher a- and b-wave amplitudes compared to BSS and AAV8.stuffer-treated mice. The 1×10

10 vg/eye dose provided the most robust functional protection while the 5×10⁹ vg/eye dose showed no significant improvement (

Figure 4). These findings indicate that AAV8.BMI1 treatment effectively protects photoreceptor, Muller cell, and bipolar cell function.

3. Discussion

There are no FDA-approved durable treatments that prevent progressive retinal damage from chronic oxidative stress. Investigational therapeutics tested in transgenic mouse models have failed to prevent AMD disease progression in clinical trials. After extensive review of potential disease models for advanced nonexudative macular degeneration [

26], our group selected the sodium iodate model. The sodium iodate retinal degeneration model induces a phenotype like geographic atrophy with patchy loss of RPE and overlying photoreceptors, resulting in severe loss of retinal function on ERG and loss of retinal cells within three months after injection. The main limitation of this model is the patchy phenotype 1 week after exposure and the potential for recovery and reversal of damage after sodium iodate exposure lower doses. For this reason, we elected for a very high dose of sodium iodate (40-50 mg/kg), at which the RPE damage is permanent. Additionally, when evaluating efficacy and photoreceptor protection, we utilized multiple methods for quantification of photoreceptor cell bodies: a spider plot to capture the treatment effect on either side of the optic, as well as an average of multiple measurements over the span of the eye, to capture a representative average. Most groups report efficacy 1 week after sodium iodate exposure, but given the chronicity of AMD, it is critical to demonstrate the durability of the therapy against chronic oxidative stress, and this durability is presented with a 3-month endpoint when most of the photoreceptor cell bodies have atrophied in the control group.

Suprachoroidal injection of AAV8 was more effective and reliable at increasing retinal BMI1 protein levels than subretinal injection of AAV5. The expression of BMI1 in retinal cells enhances cellular repair mechanisms. The observed functional protection, as measured by ERG, and structural preservation, as assessed by OCT, suggest that AAV8.BMI1 represents a promising gene therapy strategy for dry AMD.

The protective effects of BMI1 are mediated through its roles in mitochondrial bioenergetics, DNA damage repair, oxidative stress mitigation, and cellular homeostasis [

5,

7]. BMI1 has been shown to regulate key pathways, including p16INK4a/Rb and p19ARF/p53, which are critical for maintaining retinal cell survival and reducing inflammation [

6,

8]. Our results align with previous studies demonstrating that BMI1 overexpression protects against oxidative stress and promotes cellular repair in various tissues. The significant increase in BMI1 levels in the retina and RPE, coupled with improved ONL thickness and ERG responses, underscores its potential to counteract the pathological processes underlying dry AMD [

12,

26].

The dose-dependent efficacy observed in our study, with the 1×10

10 vg/eye dose providing the most robust protection, suggests that optimizing BMI1 expression levels is crucial for therapeutic success. These findings are consistent with previous reports on AAV-mediated gene therapy, where higher vector doses often correlate with enhanced therapeutic outcomes [

27,

28].

The suprachoroidal injection (SCI) approach used in this study offers several advantages, including targeted delivery to the retina and RPE, reduced systemic exposure, and minimal invasiveness. This method has been increasingly adopted in preclinical and clinical studies for retinal gene therapy, demonstrating its feasibility and safety [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. This study demonstrates long-term transgene expression stability, facilitating clinical translation [

34,

35]. Preclinical studies in larger animal models with clinical suprachoroidal delivery devices could provide valuable insights into the pharmacokinetic profile of AAV.BMI1 therapy [

36] and will guide clinical dosing.

With testing in two serotypes, two murine species, and two routes of administration, our robust results demonstrate that AAV-mediated BMI1 gene delivery provides a significant, durable, dose-dependent protection of RPE and photoreceptor cells against oxidative stress-induced retinal degeneration.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. AAV Vectors

AAV8 Stuffer was produced by Vector Builder (Chicago, IL) with a 981 base pair noncoding sequence. AAV5.BMI1 was produced by Signagen (Frederick, MD), and AAV8.BMI1 was produced by Forge Biologics (Grove City, OH). Final preparations were diluted with BSS (Balanced salt solution, Alcon, Fort Worth, TX).

4.2. Animals

All animals were treated in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and in accordance with our IACUC-approved protocols. A total of 36 Balb/c mice and 20 C57BL/6 mice were used for the sodium iodate experiments.

Sixteen 8-week-old Balb/c mice were divided into three groups: (1) BSS (control) and sodium iodate, (2) AAV5.BMI1 (1×10⁹ vg/eye) and NaIO3, (3) controls (no treatment or sodium iodate). Each group received bilateral subretinal injections of the respective treatment, followed by NaIO3 intraperitoneal (i.p.) administration (50 mg/kg) four weeks later to induce retinal degeneration. Seven days later, two mice per group and one control were euthanized, and ocular tissues were fixed and cryosectioned for immunofluorescence staining with rhodopsin and H&E staining. Twenty-one days later, animals were euthanized, and ocular tissues were collected for pathologic analyses. Fifteen weeks later, animals were euthanized, and ocular tissues were collected for pathologic analyses and immunofluorescence staining with rhodopsin.

Twenty 8-week-old Balb/c mice were divided into three groups: (1) BSS (control), (2) BSS with and NaIO3, and (3) AAV5. BMI1 (1×10⁹ vg/eye) with NaIO3. Each group received bilateral subretinal injections of the respective treatment, followed by NaIO3 i.p. administration (50 mg/kg) twenty-eight days after AAV injection. OCT images were collected under isoflurane anesthesia on day 35, and ERG was performed on day 40. Animals were sacrificed on day 42. Ocular tissues were collected for protein and histological analyses.

Twenty 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice were used for the study. Mice were divided into four groups: (1) BSS (control, n=5), (2) AAV8.stuffer (1×1010 vg/eye, n=5), (3) AAV8.BMI1 (5×10⁹ vg/eye, n=5), and (4) AAV8.BMI1 (1×1010 vg/eye, n=5). Each group received bilateral suprachoroidal injections of the respective treatment, followed by NaIO3 tail vein administration (40 mg/kg) four weeks later to induce retinal degeneration.

4.3. Subretinal Injection

Mice were anesthetized with a 1.5% isoflurane (Isoflurane UPS) in 100% oxygen in a custom-made anesthetic holder. Mice will be given a cocktail of 0.5% Cyclopentolate HCl and 10% Phenylephrine HCl topically to dilate and proptose the eyes after one drop of 0.5% proparacaine HCL was applied to both eyes. The injection was performed under direct visualization using a surgical microscope and a micromanipulator. A small pilot hole using the tip of a 33-gauge needle was made in the posterior sclera for subretinal injection using a 34-gauge blunt needle and Hamilton syringe (1µl/eye). BSS or AAV5.BMI1 was delivered subretinally in the mice. AAV5.BMI1 vectors were produced to the appropriate titers, and the injection volume was calibrated to ensure consistent delivery of the vector.

4.4. Suprachoroidal Injection

As described previously ([

9]), mice were anesthetized with a 1.5% isoflurane (Isoflurane UPS) in 100% oxygen in a custom-made anesthetic holder. Eyes were visualized with a surgical microscope. A 34-gauge needle on a 1-ml syringe was used to make an oblique, partial-thickness scleral tunnel 4-mm posterior to the limbus, and then a 34-gauge blunt-tip needle attached to a 10-µl Hamilton syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV) was used to enter the suprachoroidal space (SCC). 1 µl of BSS, AAV8 stuffer or AAV8.BMI1 was delivered via suprachoroidal injection into the eyes of the mice. AAV8.BMI1 and AAV8.stuffer vectors were produced to the appropriate titers, and the injection volume was calibrated to ensure consistent delivery of the vector.

4.5. Electroretinography

Mice were dark-adapted overnight and anesthetized with intraperitoneal ketamine (150 mg/kg) and xylazine (45 mg/kg) under dim-red illumination. All electroretinography (ERG) recordings were performed with the Celeris system (Diagnosys LLC, Lowell, MA) after topical application of 0.5% Cyclopentolate HCl and 10% Phenylephrine HCl for pupillary dilation and 0.5% Proparacaine HCL for topical anesthesia. Data shown was recorded with the following parameters: Scotopic, photopic and C-wave ERGs.

4.6. Optical Coherence Tomography

After 0.5% Cyclopentolate HCl and 10% Phenylephrine HCl for pupillary dilation and 0.5% Proparacaine HCL for topical anesthesia, optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed under anesthesia with 1.5% isoflurane (Isoflurane UPS) in 100% oxygen in a custom-made anesthetic holder using Spectralis HRA+OCT (Heidelberg Engineering Inc., Heidelberg, Germany).

The combination of scanning laser retinal imaging and OCT allows for real-time tracking of eye movements and real-time averaging of OCT scans, reducing speckle noise in the OCT images. Total retina and ONL thicknesses were calculated by the manufacturer's proprietary Eye Explorer algorithm, with manual correction of segmentation lines as needed, and averaged for each region of retinal imaging.

4.7. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

Ocular tissues were homogenized with ultrasound, and total RNA was isolated using Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) per the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was quantified with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Then, cDNA was synthesized using the First strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) per manufacturer’s protocol. qRT-PCR was performed with the QuantStudio 6 pro RT PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The fold change in expression was calculated by taking 2 to the negative power of the ΔΔCt value.

4.8. MSD (Meso Scale Discovery) Assay for BMI1 Quantification

Retina and RPE lysates were generated by homogenization in ice-cold T-PER tissue protein extraction reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) freshly supplemented with the Halt Protease inhibitor cocktail proteinase inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). After homogenization, samples were centrifuged at >10,000 g and 4°C for 10 minutes. Then, supernatant was carefully collected. Total protein concentration was measured by the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

BMI1 protein levels were quantified from ocular tissues using an antigen-capture immunogenicity assay on the MSD (Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, MD) platform. Retina and RPE lysates were diluted to 5 µg/25µl total protein concentration. BMI1 level was determined by MSD Meso QuickPlex SQ 120MM Discovery Workbench software v.4.0.

4.9. Immunofluorescence and Immunohistochemistry

Eyes were removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 1 × PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 24 h at 4 °C. Fixed eyes were cryoprotected in sucrose prepared in 1 × PBS: 10%, 20% and 30% sucrose. Eyes were then embedded in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek. Torrance, CA), snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C. Frozen eyes were sectioned at 7 μm thickness on a Leica CM1950 cryostat (Leica Biosystems, Deer Park, IL). The retinal sections were incubated for 1 hour in 5% goat serum blocking solution. These sections were incubated with mouse anti-Rhodopsin antibody (Novus Bio, Centennial, CO). After washing with blocking solution, sections were incubated with AlexFluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and nuclei stained using DAPI (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA). The sections were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Inc.), cover-slipped, and analyzed with an EVOS™ M7000 imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Immunohistochemistry was conducted on cryosections using rabbit anti-BMI1 (Bethyl lab, Montgomery, TX) antibody. After washing with blocking solution, the sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories Inc., Westgroove, PA) for 1 h at room temperature. The slides were developed using the ImmPACT DAB substrate kit (Vector laboratories). The slides were counterstained with hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA). Slides were mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Inc.), cover-slipped, and analyzed with an EVOS™ M7000 imaging system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

4.10. Quantification of Outer Nuclear Layer Thickness

In AAV5 studies, quantification was performed on OCT images. The Heidelberg Eye explorer software provided automatic layer segmentation. Layers were manually corrected when not representative by two readers masked to treatment group. Five measurements were taken at 100 µm intervals on either side of the optic nerve (ON) on five B-scans. Measurements were pooled over the whole eye for each animal to account for topographic variability.

In AAV8 studies, quantification was also conducted on OCT images with manual correction of retinal layers. Measurements were taken utilizing the Heidelberg Eye Explorer measurement tool at 1500 µm on either side of the optic nerve. Measurements were compared across groups for each location, and a spiderplot was generated.

4.11. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA). The results are expressed as mean ± SD.

To determine the statistical differences between the two unpaired groups, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test was used. To compare three or more different treatment groups, ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparisons was performed. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

The sodium iodate induced oxidative stress model overcomes many of the limitations of transgenic mouse models and, while an acute oxidative stress model, activates oxidative stress-induced retinal cell death. We determined that suprachoroidal delivery of an AAV8 vector resulted in better transduction efficiency and safety than subretinal delivery of an AAV5 vector. These studies provides robust and reproducible data supporting the protective role of BMI1 in photoreceptors and RPE in a NaIO3-induced retinal degeneration in two murine species. Expression of BMI1 with AAV vectors effectively and durably protects against retinal dysfunction and structural degeneration, highlighting its potential as a treatment, if introduced earlier in the disease stage, that can prevent advanced AMD. These findings lay the groundwork for future clinical trials targeting retinal degenerative diseases.

In summary, AAV-delivered BMI1 expression preserves retinal integrity and function and shows compelling therapeutic promise for the treatment of intermediate dry AMD. An in-office suprachoroidal delivery of this vector has the potential to be an early intervention and meet an unmet need in the treatment of macular degeneration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L. and H.R.; methodology, Z.L. and S.L.; software, Z.L.; validation, Z.L. and H.R., data curation, Z.L. A.W., and H.R.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.L.; data collection, Z.L. S. L. and G. M.; writing—review and editing, H.R. and R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

AAV, Adeno-associated viruses; AMD, age-related macular degeneration; BBS, balanced salt solution; BMI1, B lymphoma Mo-MLV insertion region 1 homolog; ERG, electroretinography; INL, inner nuclear layer; i.p., intraperitoneal; iv, intravenous; IPL, inner plexiform layer; IS/OS, inner segments/outer segments; NaIO3, sodium iodate; OCT, optical coherence tomography; OPL, outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; RGC, retinal ganglion cell; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; SCC, suprachoroidal space; SCI, suprachoroidal injection.

References

- Bardales, S.; Lu, Z.; Whitlock, A.; Ramkumar, H. Potency Assay for AAV vector Encoding BMI1 Protein for the Treatment of Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2023, 64, 1134–1134. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Whitlock, A.; Ramkumar, R.; Ramkumar, H. Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Suprachoroidal Delivery of AAV.BMI1 in C57/B6 Mice. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 2024, 65, 201–201. [Google Scholar]

- Rein, D.B.; Wittenborn, J.S.; Burke-Conte, Z.; Gulia, R.; Robalik, T.; Ehrlich, J.R.; Lundeen, E.A.; Flaxman, A.D. Prevalence of Age-Related Macular Degeneration in the US in 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol 2022, 140, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drag, S.; Dotiwala, F.; Upadhyay, A.K. Gene Therapy for Retinal Degenerative Diseases: Progress, Challenges, and Future Directions. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2023, 64, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatoo, W.; Abdouh, M.; David, J.; Champagne, M.P.; Ferreira, J.; Rodier, F.; Bernier, G. The polycomb group gene Bmi1 regulates antioxidant defenses in neurons by repressing p53 pro-oxidant activity. J Neurosci 2009, 29, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.; Sauvageau, G. Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature 2003, 423, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cao, L.; Chen, J.; Song, S.; Lee, I.H.; Quijano, C.; Liu, H.; Keyvanfar, K.; Chen, H.; Cao, L.Y.; et al. Bmi1 regulates mitochondrial function and the DNA damage response pathway. Nature 2009, 459, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molofsky, A.V.; Pardal, R.; Iwashita, T.; Park, I.K.; Clarke, M.F.; Morrison, S.J. Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation. Nature 2003, 425, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Morales, M.G.; Liu, S.; Ramkumar, H.L. The Endogenous Expression of BMI1 in Adult Human Eyes. Cells 2024, 13, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatoo, W.; Abdouh, M.; Duparc, R.H.; Bernier, G. Bmi1 distinguishes immature retinal progenitor/stem cells from the main progenitor cell population and is required for normal retinal development. Stem Cells 2010, 28, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, C.Z.; Ma, M.; Shao, G.F. MiR-15 suppressed the progression of bladder cancer by targeting BMI1 oncogene via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2019, 23, 8813–8822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaarniranta, K.; Uusitalo, H.; Blasiak, J.; Felszeghy, S.; Kannan, R.; Kauppinen, A.; Salminen, A.; Sinha, D.; Ferrington, D. Mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction and their impact on age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res 2020, 79, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, S.; Oshima, M.; Yuan, J.; Saraya, A.; Miyagi, S.; Konuma, T.; Yamazaki, S.; Osawa, M.; Nakauchi, H.; Koseki, H.; et al. Bmi1 confers resistance to oxidative stress on hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e36209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Xue, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Miao, D. BMI1 Deficiency Results in Female Infertility by Activating p16/p19 Signaling and Increasing Oxidative Stress. Int J Biol Sci 2019, 15, 870–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S.; Sun, W.; Miao, D. Bmi1 Overexpression in Mesenchymal Stem Cells Exerts Antiaging and Antiosteoporosis Effects by Inactivating p16/p19 Signaling and Inhibiting Oxidative Stress. Stem Cells 2019, 37, 1200–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, L.; Ni, W.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; Miao, D.; Chai, R.; Li, H. Bmi1 regulates auditory hair cell survival by maintaining redox balance. Cell Death Dis 2015, 6, e1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibenedetto, S.; Niklison-Chirou, M.; Cabrera, C.P.; Ellis, M.; Robson, L.G.; Knopp, P.; Tedesco, F.S.; Ragazzi, M.; Di Foggia, V.; Barnes, M.R.; et al. Enhanced Energetic State and Protection from Oxidative Stress in Human Myoblasts Overexpressing BMI1. Stem Cell Reports 2017, 9, 528–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, S.G.; Boulton, M.E. Consequences of oxidative stress in age-related macular degeneration. Mol Aspects Med 2012, 33, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppinen, A.; Paterno, J.J.; Blasiak, J.; Salminen, A.; Kaarniranta, K. Inflammation and its role in age-related macular degeneration. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016, 73, 1765–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabino, A.; Plamondon, V.; Abdouh, M.; Chatoo, W.; Flamier, A.; Hanna, R.; Zhou, S.; Motoyama, N.; Hebert, M.; Lavoie, J.; et al. Loss of Bmi1 causes anomalies in retinal development and degeneration of cone photoreceptors. Development 2016, 143, 1571–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Q.; Gong, X.; Gong, L.; Zhang, L.; Tang, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, F.; Fu, J.L.; Xiang, J.W.; Xiao, Y.; et al. Sodium Iodate-Induced Mouse Model of Age-Related Macular Degeneration Displayed Altered Expression Patterns of Sumoylation Enzymes E1, E2 and E3. Curr Mol Med 2018, 18, 550–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Kim, H.L.; Oh, Y.; Xu, Q. Sodium iodate-induced retina degeneration observed in non-separate sclerochoroid/retina pigment epithelium/retina whole mounts. Ann Eye Sci 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geathers, J.S.; Grillo, S.L.; Karakoleva, E.; Campbell, G.P.; Du, Y.; Chen, H.; Barber, A.J.; Zhao, Y.; Sundstrom, J.M. Sodium Iodate: Rapid and Clinically Relevant Model of AMD. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2024, 29, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, M.; Bonilha, V.L. Regulated cell death pathways in the sodium iodate model: Insights and implications for AMD. Exp Eye Res 2024, 238, 109728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, B.D.; Lee, T.T.; Bell, B.A.; Wang, T.; Dunaief, J.L. Optimizing the sodium iodate model: Effects of dose, gender, and age. Exp Eye Res 2024, 239, 109772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, M.; Bora, K.; Blomfield, A.K.; Pavlovich, M.C.; Huang, S.; Liu, C.H.; Chen, J. Oxidative stress in retinal pigment epithelium degeneration: from pathogenesis to therapeutic targets in dry age-related macular degeneration. Neural Regen Res 2023, 18, 2173–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkara, D.; Byrne, L.C.; Klimczak, R.R.; Visel, M.; Yin, L.; Merigan, W.H.; Flannery, J.G.; Schaffer, D.V. In vivo-directed evolution of a new adeno-associated virus for therapeutic outer retinal gene delivery from the vitreous. Sci Transl Med 2013, 5, 189ra176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; Bennett, J.; Wellman, J.A.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.F.; Tillman, A.; Wittes, J.; Pappas, J.; Elci, O.; McCague, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of voretigene neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) in patients with RPE65-mediated inherited retinal dystrophy: a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.J.; Dai, X.; Boye, S.E.; Barone, I.; Boye, S.L.; Mao, S.; Everhart, D.; Dinculescu, A.; Liu, L.; Umino, Y.; et al. Long-term retinal function and structure rescue using capsid mutant AAV8 vector in the rd10 mouse, a model of recessive retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther 2011, 19, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Campochiaro, P.A.; Green, J.J. Suprachoroidal Delivery of Viral and Nonviral Vectors for Treatment of Retinal and Choroidal Vascular Diseases. Am J Ophthalmol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habot-Wilner, Z.; Noronha, G.; Wykoff, C.C. Suprachoroidally injected pharmacological agents for the treatment of chorio-retinal diseases: a targeted approach. Acta Ophthalmol 2019, 97, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naftali Ben Haim, L.; Moisseiev, E. Drug Delivery via the Suprachoroidal Space for the Treatment of Retinal Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.Y.; Fujioka, J.K.; Gholamian, T.; Zaharia, M.; Tran, S.D. Suprachoroidal Injection: A Novel Approach for Targeted Drug Delivery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Fu, Y.; Ma, L.; Yao, Y.; Ge, S.; Yang, Z.; Fan, X. AAV for Gene Therapy in Ocular Diseases: Progress and Prospects. Research (Wash D C) 2023, 6, 0291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.A.; Khan, H.; Khanani, Z.A.; Thomas, M.J.; Khan, H.; Ahmed, A.; Gahn, G.M.; Khanani, A.M. Review of Gene Therapy Clinical Trials for Retinal Diseases. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2024, 64, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLaren, R.E.; Groppe, M.; Barnard, A.R.; Cottriall, C.L.; Tolmachova, T.; Seymour, L.; Clark, K.R.; During, M.J.; Cremers, F.P.; Black, G.C.; et al. Retinal gene therapy in patients with choroideremia: initial findings from a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchert, G.A.; Shamsnajafabadi, H.; Hu, M.L.; De Silva, S.R.; Downes, S.M.; MacLaren, R.E.; Xue, K.; Cehajic-Kapetanovic, J. The Role of Inflammation in Age-Related Macular Degeneration-Therapeutic Landscapes in Geographic Atrophy. Cells 2023, 12, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).