Submitted:

07 January 2026

Posted:

08 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

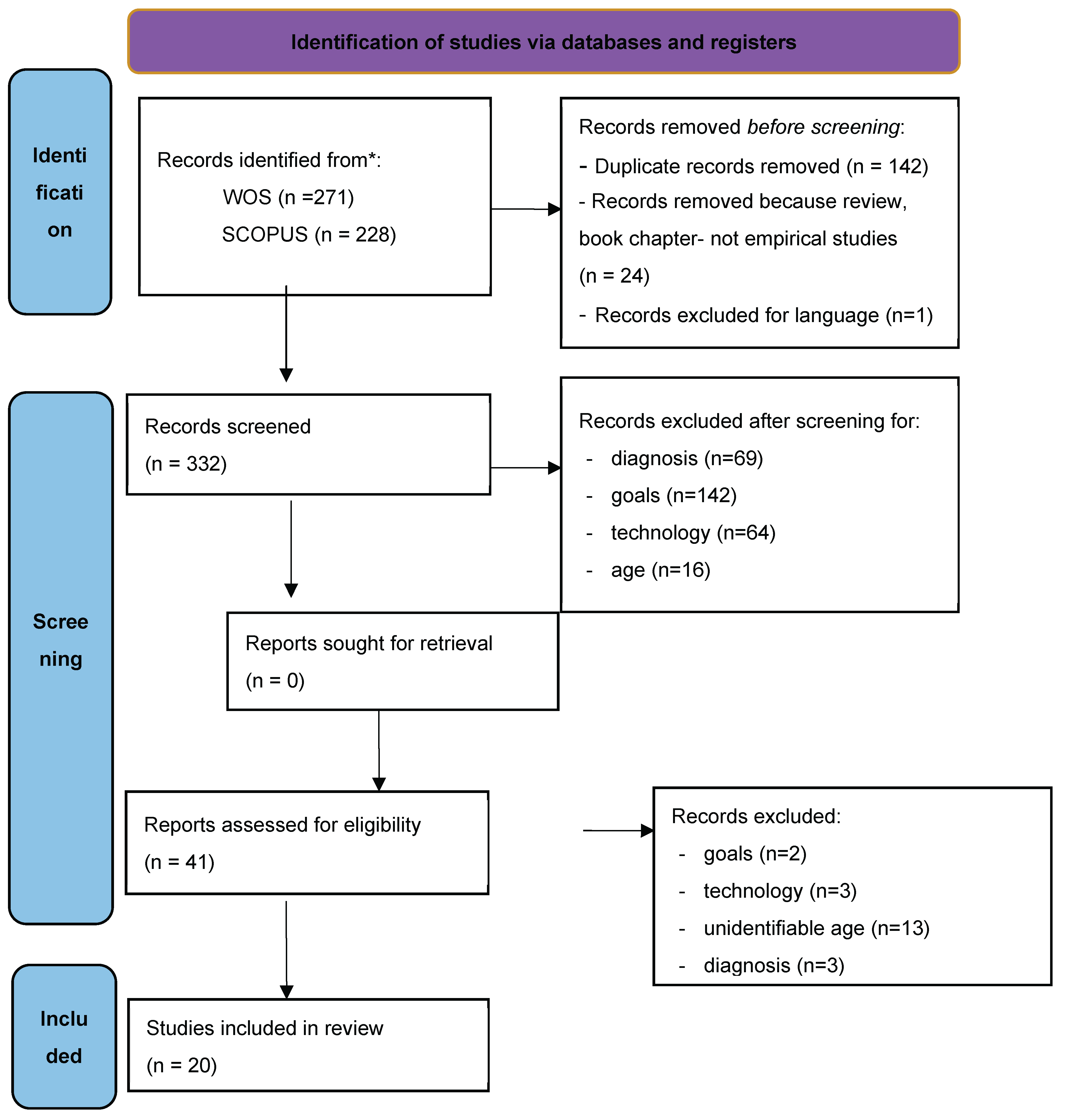

Background: Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by inattention, motor hyperactivity and verbal and cognitive impulsivity. Impairments in executive functions (EFs), in particular working memory, monitoring and organization of daily life-are frequently observed in children diagnosed with ADHD, and are reflected in behavioural, social-emotional and learning difficulties. The development and use of technologies such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR) for ADHD have increased in recent years, using a variety of tools to support including PC, video games, wearable devices and tangible interfaces. Objectives: To systematically map the current state of research on the use of AR, VR and MR technologies to assess and/or enhance EFs in children with ADHD. To evaluate the effects on their quality of life and on families’ and caregivers’ burden reduction. To explore the interventions’ clinical validity. Methods: A scoping review according to PRISMA-ScR guidelines was conducted. A systematic search was carried out in the Scopus and Web of Science databases for studies published between 2015 and 2025.Empirical studies published in English that examined children with ADHD aged < 13 years were included. AR, VR, or MR-based interventions focused on EF were considered. For each study, the following features were recorded: year and country of publication, design, objectives, EFs considered, technology and hardware used, main results, and limitations. Results: Twenty studies were identified. The most frequently addressed functional domains were sustained and selective visual attention, working memory, and inhibition. Assessment interventions primarily involved the use of a head-mounted display (HMD) in conjunction with the Continuous Performance Test (CPT). Training interventions included immersive VR, serious video games, VR with motor or dual-task training, and MR. The results suggest that VR can enhance cognitive performance and sustained attention; however, longitudinal studies are required to evaluate its long-term effectiveness and integrate emotional skills. Conclusions: The use of these technologies is a promising strategy for assessment and training of EFs in children with ADHD. These tools provide positive, inclusive feedback and motivating tasks. Nevertheless, larger sample studies, longitudinal follow-ups to confirm the suitability and effectiveness of the technology-based programs are warranted.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Assessment

3.2. Training

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Research Perspectives

- -

- greater uniformity among protocols regarding measures (frequency, duration, contexts, pre- and post-intervention tests), types of VRtechnology, presence or absence of distractors, and the use of control groups;

- -

- longitudinal studies with large samples to generalize and consolidate the results over time;

- -

- greater individualized treatment of emotional skills, as virtual environments may not faithfully replicate the wide range of real-world contexts and situations to which children are exposed[87].

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

References

- Salari, N.; Ghasemi, H.; Abdoli, N.; Rahmani, A.; Shiri, M. H.; Hashemian, A. H.; Akbari, H.; Mohammadi, M. The Global Prevalence of ADHD in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ital J Pediatr 2023, 49, 48. [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Jaramillo, L.; Herrera-Solís, A.; Herrera-Morales, W. V. ADHD: Reviewing the Causes and Evaluating Solutions. J Pers Med 2021, 11 (3), 166. [CrossRef]

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders | Psychiatry Online. DSM Library. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 (accessed 2026-01-05).

- Barkley, R. A. Behavioral Inhibition, Sustained Attention, and Executive Functions: Constructing a Unifying Theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin 1997, 121 (1), 65–94. [CrossRef]

- Castellanos, F. X.; Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S.; Milham, M. P.; Tannock, R. Characterizing Cognition in ADHD: Beyond Executive Dysfunction. Trends Cogn Sci 2006, 10 (3), 117–123. [CrossRef]

- Martinussen, R.; Hayden, J.; Hogg-Johnson, S.; Tannock, R. A Meta-Analysis of Working Memory Impairments in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005, 44 (4), 377–384. [CrossRef]

- Nigg, J. T. What Causes ADHD?: Understanding What Goes Wrong and Why; Guilford Press: New York, 2006.

- Anderson, P. Assessment and Development of Executive Function (EF) during Childhood. Child Neuropsychol 2002, 8 (2), 71–82. [CrossRef]

- Suchy, Y. Executive Functioning: Overview, Assessment, and Research Issues for Non-Neuropsychologists. Ann Behav Med 2009, 37 (2), 106–116. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive Functions. Annu Rev Psychol 2013, 64, 135–168. [CrossRef]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N. P.; Emerson, M. J.; Witzki, A. H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T. D. The Unity and Diversity of Executive Functions and Their Contributions to Complex “Frontal Lobe” Tasks: A Latent Variable Analysis. Cogn Psychol 2000, 41 (1), 49–100. [CrossRef]

- Zelazo, P. D.; Cunningham, W. Executive Function: Mechanisms Underlying Emotion Regulation. In Handbook of emotion regulation; Gross, J., Ed.; Guilford: New York, NY, 2007; pp 135–158.

- Sambol, S.; Suleyman, E.; Ball, M. The Interplay of Hot and Cool Executive Functions: Implications for a Unified Executive Framework. Cognitive Systems Research 2025, 91, 101360. [CrossRef]

- Tyburski, E.; Mak, M.; Sokołowski, A.; Starkowska, A.; Karabanowicz, E.; Kerestey, M.; Lebiecka, Z.; Preś, J.; Sagan, L.; Samochowiec, J.; Jansari, A. S. Executive Dysfunctions in Schizophrenia: A Critical Review of Traditional, Ecological, and Virtual Reality Assessments. J Clin Med 2021, 10 (13), 2782. [CrossRef]

- Hirose, S.; Chikazoe, J.; Watanabe, T.; Jimura, K.; Kunimatsu, A.; Abe, O.; Ohtomo, K.; Miyashita, Y.; Konishi, S. Efficiency of Go/No-Go Task Performance Implemented in the Left Hemisphere. J Neurosci 2012, 32 (26), 9059–9065. [CrossRef]

- Jonides, J.; Smith, E. E. The Architecture of Working Memory. In Cognitive neuroscience; Studies in cognition; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, US, 1997; pp 243–276.

- Kalbfleisch, L. Neurodevelopment of the Executive Functions. In Executive functions in health and disease; Elsevier Academic Press: San Diego, CA, US, 2017; pp 143–168. [CrossRef]

- Chevignard, M.; Pillon, B.; Pradat-Diehl, P.; Taillefer, C.; Rousseau, S.; Le Bras, C.; Dubois, B. An Ecological Approach to Planning Dysfunction: Script Execution. Cortex 2000, 36 (5), 649–669. [CrossRef]

- Fortin, S.; Godbout, L.; Braun, C. M. J. Cognitive Structure of Executive Deficits in Frontally Lesioned Head Trauma Patients Performing Activities of Daily Living. Cortex 2003, 39 (2), 273–291. [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, L.; Giovanello, K. Executive Function in Daily Life: Age-Related Influences of Executive Processes on Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Psychol Aging 2010, 25 (2), 343–355. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Liang, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Shum, D. H. K. Efficacy of Non-Pharmacological Interventions on Executive Functions in Children and Adolescents with ADHD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Asian J Psychiatr 2023, 87, 103692. [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, N.; Păsărelu, C.-R.; Voinescu, A. Immersive Virtual Reality for Improving Cognitive Deficits in Children with ADHD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Virtual Real 2023, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A. D.; Cruit, J.; Endsley, M.; Beers, S. M.; Sawyer, B. D.; Hancock, P. A. The Effects of Virtual Reality, Augmented Reality, and Mixed Reality as Training Enhancement Methods: A Meta-Analysis. Hum Factors 2021, 63 (4), 706–726. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Saavedra, L.; Miró-Amarante, L.; Domínguez-Morales, M. Augmented and Virtual Reality Evolution and Future Tendency. Applied Sciences 2020, 10 (1), 322. [CrossRef]

- Mann, S.; Furness, T.; Yuan, Y.; Iorio, J.; Wang, Z. All Reality: Virtual, Augmented, Mixed (X), Mediated (X,Y), and Multimediated Reality. arXiv April 20, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Apochi, O. O.; Olusanya, M. D.; Wesley, M.; Musa, S. I.; Ayomide Peter, O.; Adebayo, A. A.; Olaitan Komolafe, D. Virtual, Mixed, and Augmented Realities: A Commentary on Their Significance in Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropsychology. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2024, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Mühlberger, A.; Jekel, K.; Probst, T.; Schecklmann, M.; Conzelmann, A.; Andreatta, M.; Rizzo, A. A.; Pauli, P.; Romanos, M. The Influence of Methylphenidate on Hyperactivity and Attention Deficits in Children With ADHD: A Virtual Classroom Test. J Atten Disord 2020, 24 (2), 277–289. [CrossRef]

- Romero-Ayuso, D.; del Pino-González, A.; Torres-Jiménez, A.; Juan-González, J.; Celdrán, F. J.; Franchella, M. C.; Ortega-López, N.; Triviño-Juárez, J. M.; Garach-Gómez, A.; Arrabal-Fernández, L.; Medina-Martínez, I.; González, P. Enhancing Ecological Validity: Virtual Reality Assessment of Executive Functioning in Children and Adolescents with ADHD. Children (Basel) 2024, 11 (8), 986. [CrossRef]

- Gounari, K. A.; Giatzoglou, E.; Kemm, R.; Beratis, I. N.; Nega, C.; Kourtesis, P. The Trail Making Test in Virtual Reality (TMT-VR): Examination of the Ecological Validity, Usability, Acceptability, and User Experience in Adults with ADHD. Psychiatry International 2025, 6 (1), 31. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-A.; Kim, J.-Y.; Park, J.-H. Concurrent Validity of Virtual Reality-Based Assessment of Executive Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Intelligence 2024, 12 (11), 108. [CrossRef]

- Holleman, G. A.; Hooge, I. T. C.; Kemner, C.; Hessels, R. S. The ‘Real-World Approach’ and Its Problems: A Critique of the Term Ecological Validity. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Fang, C.; Che, Y.; Peng, X.; Zhang, X.; Lin, D. Reward Feedback Mechanism in Virtual Reality Serious Games in Interventions for Children With Attention Deficits: Pre- and Posttest Experimental Control Group Study. JMIR Serious Games 2025, 13, e67338. [CrossRef]

- Yen, J. M.; Lim, J. H. A Clinical Perspective on Bespoke Sensing Mechanisms for Remote Monitoring and Rehabilitation of Neurological Diseases: Scoping Review. Sensors 2023, 23 (1), 536. [CrossRef]

- Tajik-Parvinchi, D.; Wright, L.; Schachar, R. Cognitive Rehabilitation for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Promises and Problems. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry / Journal de l’Académie canadienne de psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent 2014, 23 (3), 207–217.

- Tajik-Parvinchi, D.; Wright, L.; Schachar, R. Cognitive Rehabilitation for Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Promises and Problems. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014, 23 (3), 207–217.

- Borgnis, F.; Baglio, F.; Pedroli, E.; Rossetto, F.; Uccellatore, L.; Oliveira, J. A. G.; Riva, G.; Cipresso, P. Available Virtual Reality-Based Tools for Executive Functions: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T. D.; Gaggioli, A.; Riva, G. Virtual Reality for Research in Social Neuroscience. Brain Sci 2017, 7 (4), 42. [CrossRef]

- Güler, E. C.; Köse, B.; Temeltürk, R. D.; Aynigül, K. D.; Pekçetin, S.; Öztop, D. B. Investigation of the Effect of Second-Generation Virtual Reality Interventions on Hot and Cold Executive Functions in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Study. Games Health J 2025. [CrossRef]

- Rmus, M.; McDougle, S. D.; Collins, A. G. The Role of Executive Function in Shaping Reinforcement Learning. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 2021, 38, 66–73. [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, J.; Balasubramani, M.; Rajan, V. A.; S, V.; Aeron, A.; Arora, M. Reinforcement Learning for Optimizing Real-Time Interventions and Personalized Feedback Using Wearable Sensors. Measurement: Sensors 2024, 33, 101151. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Q.; Mao, J.; Sun, J.; Teo, W.-P. Exercise Intensity of Virtual Reality Exergaming Modulates the Responses to Executive Function and Affective Response in Sedentary Young Adults: A Randomized, Controlled Crossover Feasibility Study. Physiol Behav 2025, 288, 114719. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.-L.; Chaw, X.-J.; Fresnoza, S.; Kuo, H.-I. Effects of Virtual Reality-Based Exercise Intervention in Young People with Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation 2025, 22 (1), 139. [CrossRef]

- Benzing, V.; Schmidt, M. The Effect of Exergaming on Executive Functions in Children with ADHD: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2019, 29 (8), 1243–1253. [CrossRef]

- Goharinejad, S.; Goharinejad, S.; Hajesmaeel-Gohari, S.; Bahaadinbeigy, K. The Usefulness of Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Reality Technologies in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children: An Overview of Relevant Studies. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22 (1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Poon, K. Hot and Cool Executive Functions in Adolescence: Development and Contributions to Important Developmental Outcomes. Front Psychol 2017, 8, 2311. [CrossRef]

- Rapoport, J. L.; Giedd, J. N.; Blumenthal, J.; Hamburger, S.; Jeffries, N.; Fernandez, T.; Nicolson, R.; Bedwell, J.; Lenane, M.; Zijdenbos, A.; Paus, T.; Evans, A. Progressive Cortical Change during Adolescence in Childhood-Onset Schizophrenia. A Longitudinal Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999, 56 (7), 649–654. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S.; Akl, E. A.; Chang, C.; McGowan, J.; Stewart, L.; Hartling, L.; Aldcroft, A.; Wilson, M. G.; Garritty, C.; Lewin, S.; Godfrey, C. M.; Macdonald, M. T.; Langlois, E. V.; Soares-Weiser, K.; Moriarty, J.; Clifford, T.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Straus, S. E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169 (7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A. C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C. M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid Synth 2020, 18 (10), 2119–2126. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q. N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; Rousseau, M.-C.; Vedel, I.; Pluye, P. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 for Information Professionals and Researchers. Education for Information 2018, 34 (4), 285–291. [CrossRef]

- Merzon, L.; Pettersson, K.; Aronen, E. T.; Huhdanpää, H.; Seesjärvi, E.; Henriksson, L.; MacInnes, W. J.; Mannerkoski, M.; Macaluso, E.; Salmi, J. Eye Movement Behavior in a Real-World Virtual Reality Task Reveals ADHD in Children. Sci Rep 2022, 12 (1), 20308. [CrossRef]

- Stokes, J. D.; Rizzo, A.; Geng, J. J.; Schweitzer, J. B. Measuring Attentional Distraction in Children With ADHD Using Virtual Reality Technology With Eye-Tracking. Front Virtual Real 2022, 3, 855895. [CrossRef]

- Neguț, A.; Jurma, A. M.; David, D. Virtual-Reality-Based Attention Assessment of ADHD: ClinicaVR: Classroom-CPT versus a Traditional Continuous Performance Test. Child Neuropsychology 2017, 23 (6), 692–712. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Han, D.; Luo, H. A Virtual Reality Application for Assessment for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in School-Aged Children. NDT 2019, Volume 15, 1517–1523. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. J.; Yum, J. Y.; Kim, K.; Shin, B.; Eom, H.; Hong, Y.; Heo, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, H. S.; Kim, E. Evaluating Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms in Children and Adolescents through Tracked Head Movements in a Virtual Reality Classroom: The Effect of Social Cues with Different Sensory Modalities. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 943478. [CrossRef]

- Eom, H.; Kim, K. (Kenny); Lee, S.; Hong, Y.-J.; Heo, J.; Kim, J.-J.; Kim, E. Development of Virtual Reality Continuous Performance Test Utilizing Social Cues for Children and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2019, 22 (3), 198–204. [CrossRef]

- Hong, N.; Kim, J.; Kwon, J.-H.; Eom, H.; Kim, E. Effect of Distractors on Sustained Attention and Hyperactivity in Youth With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Using a Mobile Virtual Reality School Program. J Atten Disord 2022, 26 (3), 358–369. [CrossRef]

- Seesjärvi, E.; Puhakka, J.; Aronen, E. T.; Lipsanen, J.; Mannerkoski, M.; Hering, A.; Zuber, S.; Kliegel, M.; Laine, M.; Salmi, J. Quantifying ADHD Symptoms in Open-Ended Everyday Life Contexts With a New Virtual Reality Task.

- Ju, Y.; Kang, S.; Kim, J.; Ryu, J.-K.; Jeong, E.-H. Clinical Utility of Virtual Kitchen Errand Task for Children (VKET-C) as a Functional Cognition Evaluation for Children with Developmental Disabilities. Children 2024, 11 (11), 1291. [CrossRef]

- Pasarín-Lavín, T.; García, T.; Abín, A.; Rodríguez, C. Neurodivergent Students. A Continuum of Skills with an Emphasis on Creativity and Executive Functions. Applied Neuropsychology: Child 2024, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Bioulac, S.; Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A.; Maire, J.; Bouvard, M. P.; Rizzo, A. A.; Sagaspe, P.; Philip, P. Virtual Remediation Versus Methylphenidate to Improve Distractibility in Children With ADHD: A Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial Study. J Atten Disord 2020, 24 (2), 326–335. [CrossRef]

- Shema-Shiratzky, S.; Brozgol, M.; Cornejo-Thumm, P.; Geva-Dayan, K.; Rotstein, M.; Leitner, Y.; Hausdorff, J. M.; Mirelman, A. Virtual Reality Training to Enhance Behavior and Cognitive Function among Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Brief Report. Developmental Neurorehabilitation 2019, 22 (6), 431–436. [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, M.; Manshaee, G.; Ghamarani, A.; Rasti, J. Comparison of the Effectiveness of Virtual Reality with Medication on the Memory of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Students. Int Arch Health Sci 2020, 7 (1), 37. [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.-K.; Wang, Y.-L.; Chang, H.-C.; Yen, S.-Y.; Zheng, Y.-H.; Lee, B.-O. Development of Virtual Reality Rehabilitation Games for Children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. J Ambient Intell Human Comput 2020, 11 (11), 5713–5720. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, B.; Marion, S.; Rizzo, A.; Turnbull, J.; Nolty, A. Virtual Reality Assessment of Classroom – Related Attention: An Ecologically Relevant Approach to Evaluating the Effectiveness of Working Memory Training. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1851. [CrossRef]

- Schena, A.; Garotti, R.; D’Alise, D.; Giugliano, S.; Polizzi, M.; Trabucco, V.; Riccio, M. P.; Bravaccio, C. IAmHero: Preliminary Findings of an Experimental Study to Evaluate the Statistical Significance of an Intervention for ADHD Conducted through the Use of Serious Games in Virtual Reality. IJERPH 2023, 20 (4), 3414. [CrossRef]

- Wong, K. P.; Zhang, B.; Lai, C. Y. Y.; Xie, Y. J.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Qin, J. Empowering Social Growth Through Virtual Reality–Based Intervention for Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: 3-Arm Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Serious Games 2024, 12, e58963. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hong, S.; Song, M.; Kim, K. Visual Attention and Pulmonary VR Training System for Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 53739–53751. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Ryu, J.; Choi, Y.; Kang, Y.; Li, H.; Kim, K. Eye-Contact Game Using Mixed Reality for the Treatment of Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 45996–46006. [CrossRef]

- Gol, D.; Jarus, T. Effect of a Social Skills Training Group on Everyday Activities of Children with Attention-Deficit-Hyperactivity Disorder. Dev Med Child Neurol 2005, 47 (8), 539–545. [CrossRef]

- Sadozai, A. K.; Sun, C.; Demetriou, E. A.; Lampit, A.; Munro, M.; Perry, N.; Boulton, K. A.; Guastella, A. J. Executive Function in Children with Neurodevelopmental Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nat Hum Behav 2024, 8 (12), 2357–2366. [CrossRef]

- El Wafa, H. E. A.; Ghobashy, S. A. E. L.; Hamza, A. M. A Comparative Study of Executive Functions among Children with Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder and Those with Learning Disabilities. Middle East Current Psychiatry 2020, 27 (1), 64. [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, A.; Yue, X.; Fang, S.; Zheng, Y. Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Digital Therapies in Children with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1054831. [CrossRef]

- Capobianco, M.; Puzzo, C.; Di Matteo, C.; Costa, A.; Adriani, W. Current Virtual Reality-Based Rehabilitation Interventions in Neuro-Developmental Disorders at Developmental Ages. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2025, 18. [CrossRef]

- van Mourik, R.; Oosterlaan, J.; Heslenfeld, D. J.; Konig, C. E.; Sergeant, J. A. When Distraction Is Not Distracting: A Behavioral and ERP Study on Distraction in ADHD. Clinical Neurophysiology 2007, 118 (8), 1855–1865. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, S. Experiencing an Art Education Program through Immersive Virtual Reality or iPad: Examining the Mediating Effects of Sense of Presence and Extraneous Cognitive Load on Enjoyment, Attention, and Retention. Front Psychol 2022, 13, 957037. [CrossRef]

- Sikström, S.; Söderlund, G. Stimulus-Dependent Dopamine Release in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Psychol Rev 2007, 114 (4), 1047–1075. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Hew, K. F.; Du, J. Gamification Enhances Student Intrinsic Motivation, Perceptions of Autonomy and Relatedness, but Minimal Impact on Competency: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. Education Tech Research Dev 2024, 72 (2), 765–796. [CrossRef]

- Clancy, T. A.; Rucklidge, J. J.; Owen, D. Road-Crossing Safety in Virtual Reality: A Comparison of Adolescents with and without ADHD. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2006, 35 (2), 203–215. [CrossRef]

- Babu, A.; Joseph, A. P. Integrating Virtual Reality into ADHD Therapy: Advancing Clinical Evidence and Implementation Strategies. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16. [CrossRef]

- Simón-Vicente, L.; Rodríguez-Cano, S.; Delgado-Benito, V.; Ausín-Villaverde, V.; Cubo Delgado, E. Cybersickness. A systematic literature review of adverse effects related to virtual reality. Neurologia 2024, 39 (8), 701–709. [CrossRef]

- Savaş, E. H.; Coşkun, A. B.; Elmaoğlu, E.; Semerci, R.; Şahiner, N. C. Investigating the Effects of Augmented Reality-Based Interventions on Pediatric Patient Outcomes in the Clinical Setting: A Systematic Review. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2025, 85, 39–47. [CrossRef]

- Tait, A. R.; Connally, L.; Doshi, A.; Johnson, A.; Skrzpek, A.; Grimes, M.; Becher, A.; Choi, J. E.; Weber, M. Development and Evaluation of an Augmented Reality Education Program for Pediatric Research. J Clin Transl Res 2020, 5 (3), 96–101.

- Tychsen, L.; Foeller, P. Effects of Immersive Virtual Reality Headset Viewing on Young Children: Visuomotor Function, Postural Stability, and Motion Sickness. Am J Ophthalmol 2020, 209, 151–159. [CrossRef]

- Chaytor, N.; Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. The Ecological Validity of Neuropsychological Tests: A Review of the Literature on Everyday Cognitive Skills. Neuropsychol Rev 2003, 13 (4), 181–197. [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T. D. Virtual Reality for Enhanced Ecological Validity and Experimental Control in the Clinical, Affective and Social Neurosciences. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J. O.; Dores, A. R.; Peixoto, B.; Barbosa, F. Ecological Validity in Neurocognitive Assessment: Systematized Review, Content Analysis, and Proposal of an Instrument. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2025, 32 (2), 577–594. [CrossRef]

- Schöne, B.; Kisker, J.; Lange, L.; Gruber, T.; Sylvester, S.; Osinsky, R. The Reality of Virtual Reality. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- De la Charie, A.; Delteil, F.; Labrell, F.; Colas, P.; Vigneras, J.; Câmara-Costa, H.; Mikaeloff, Y. Time Knowledge Impairments in Children with ADHD. Arch Pediatr 2021, 28 (2), 129–135. [CrossRef]

- Noreika, V.; Falter, C. M.; Rubia, K. Timing Deficits in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Evidence from Neurocognitive and Neuroimaging Studies. Neuropsychologia 2013, 51 (2), 235–266. [CrossRef]

- Ptacek, R.; Weissenberger, S.; Braaten, E.; Klicperova-Baker, M.; Goetz, M.; Raboch, J.; Vnukova, M.; Stefano, G. B. Clinical Implications of the Perception of Time in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A Review. Med Sci Monit 2019, 25, 3918–3924. [CrossRef]

- Quintero, J.; Baldiris, S.; Rubira, R.; Cerón, J.; Velez, G. Augmented Reality in Educational Inclusion. A Systematic Review on the Last Decade. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Nekar, D. M.; Lee, D.-Y.; Hong, J.-H.; Kim, J.-S.; Kim, S.-G.; Seo, Y.-G.; Yu, J.-H. Effects of Augmented Reality Game-Based Cognitive–Motor Training on Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors and Executive Function in Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Healthcare (Basel) 2022, 10 (10), 1981. [CrossRef]

- Di Giusto, V.; Purpura, G.; Zorzi, C. F.; Blonda, R.; Brazzoli, E.; Meriggi, P.; Reina, T.; Rezzonico, S.; Sala, R.; Olivieri, I.; Cavallini, A. Virtual Reality Rehabilitation Program on Executive Functions of Children with Specific Learning Disorders: A Pilot Study. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Mittmann, G.; Zehetner, V.; Hoehl, S.; Schrank, B.; Barnard, A.; Woodcock, K. Using Augmented Reality Toward Improving Social Skills: Scoping Review. JMIR Serious Games 2023, 11 (1), e42117. [CrossRef]

| First author, year | Screening | type of study | MMAT score | % Quality | |

| Bioulac, 2020 | ✓ | Randomized Controlled Trials |

4/5 | 100% | |

| Wong, 2024 | ✓ | Randomized Controlled Trials |

5/5 | 100% | |

| Cho, 2022 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 4/5 | 100% | |

| Coleman, 2019 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 2/5 | 50% | |

| Fang, 2019 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 4/5 | 100% | |

| Eom, 2019 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 3/5 | 75% | |

| Hong, 2022 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 2/5 | 50% | |

| Ju YM, 2024 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 3/5 | 75% | |

| Kim, 2024 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 3/5 | 75% | |

| Kim, 2020 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 5/5 | 100% | |

| Merzon, 2022 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 5/5 | 100% | |

| Muhlberger, 2020 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 5/5 | 100% | |

| Negut, 2017 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 5/5 | 100% | |

| Pasarín-Lavín, 2024 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 4/5 | 100% | |

| Schena, 2023 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 3/5 | 75% | |

| Seesjärv, 2022 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 4/5 | 100% | |

| Shema-Shiratzk,2018 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 2/5 | 50% | |

| Stokes, 2022 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 2/5 | 50% | |

| Tabrizi, 2020 | ✓ | Non-Randomize Studies | 3/5 | 75% | |

| Ou, 2020 | ✓ | Quantitative descriptive studies |

3/5 | 75% | |

| Screening questions | S1. Are there clear research questions? S2. Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? |

||||

|

Randomized Controlled Trial |

2.1. Is randomization appropriately performed? 2.2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? 2.3. Are there complete outcome data? 2.4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? 2.5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? |

||||

|

Non-Randomize Studies |

3.1 Are the participants representative of the target population? 3.2. Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended |

||||

|

Quantitative descriptive |

4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? 4.3. Are the measurements appropriate? 4.4. Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? 4.5. Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question |

||||

| Authors | Country | Design | Sample | Aims | Technology | EFs domain | Findings | type of intervention |

| Bioulac S. et al. (2020) | France | Randomized Controlled Trial | 51 children with ADHD (age = 7-11) | To develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a virtual classroom-based cognitive rehabilitation program to improve cognitive distractibility in children with ADHD. | The virtual classroom with HMD | Sustained visual attention; inhibition |

The VR group showed significant improvements in attention and inhibition of correct responses in both the virtual classroom task and the CPT; effects comparable to those of methylphenidate | Training |

| Cho YJ et al. (2022) | South Korea |

Controlled experimental study within-subjects | 37 children: 20 ADHD (mean age = 11.85) + 17 control group | To investigate the correlation between head movements and signals of inattention and hyperactivity and whether influenced by different social stimuli | VR-CPT | Attention; inhibition |

In subjects with ADHD, increased "out-of-context" head movement was associated with greater symptom severity. In both conditions, as the social cue increased, irrelevant head movements tended to decrease. | Assessment |

| Coleman, B. et al. (2019) | United States | Single-group pre and post design | 15 children (ages = 6-13; mean age = 10.5) | Detect classroom improvements in sustained attention and behavioural control after working memory training using a VR based ecological performance measure. | VR with headset | Sustained attention; impulsivity; working memory |

Post-training improvements in sustained and selective attention were observed in both standard neuropsychological tests and classroom VR tasks. Working memory training transfers to ecologically valid attention performance. |

Training |

| Fang YT et al. (2019) | China | Between-groups design | 140 children: 63 control group (mean age = 8.17) + 77 ADHD group (Mean age = 8.34) |

Explore the feasibility and availability of VR for evaluating symptoms of ADHD | VR with headset | Auditory and visual attention; impulsion/hyperactivity |

The VR application significantly differentiated children with ADHD from the control group in terms of correct responses, incorrect responses, and total time (sustained attention, inhibition, attentional control, and processing speed). The study's VR test is more sensitive to visual than auditory attention. Performance on the VR test was significantly correlated with scores on conventional clinical tests. |

Assessment |

| Eom H. et al. (2019) | South Korea | Mixed design |

38 children: 20 ADHD + 18 TDC (age: 6-17; mean age = 11.85) includingN=13 ADHD (65%)12 years | Analyse differences in attentional performance using a VR neuropsychological | VR-CPT | Visual sustained attention; inhibition |

VR-CPT performance correlated significantly with ADHD symptom severity, ADHD group exhibited comparable performance with TDC in the VR-CPT. Presence of a virtual teacher/social cues improved the attention performance of ADHD children. | Assessment |

| Hong N. et al. (2022) | Korea | Between-groups design | 20 children: 11 control group + 9 ADHD group (mean age = 12) | Examine the impact of distractors on the sustained attention of children and adolescents with ADHD in VR. |

VR-RVP with a HMD | Sustained attention; response inhibition | Children with ADHD performed comparable to controls in the distraction condition, but had poorer VR-RVP performance in the no-distraction condition. The presence of distractors in the VR-RVP task improved performance in participants with ADHD. |

Assessment |

| Ju YM et al. (2024) | Republic of Korea | Cross-sectional between-subjects design | 38 children: 23 typically developing + 18 developmental disabilities including 2 ADHD (ages = 7-12 years; mean age = 8,91) |

Evaluate the clinical utility of a virtual reality-based kitchen error task to assess functional cognition in children. | VKET-C | Working memory; visual attention; inhibition; pianification |

Children with ADHD committed more errors of omission (inattention) and commission (impulsivity). Although they showed fewer successful trials, they showed longer initial reflection times on some items. A positive relationship was found between task difficulty and the occurrence of commission errors. | Assessment |

| Kim J. et al. (2024) | Republic of Korea | A between subjects design | 24 children ADHD: 12 experimental group + 12 control group (ages = 8 -13; mean age = 10.7) |

Verify of us in VR to treat visual attention in ADHD subjects | VR games based on breathing training | Visual attention | The visual attention of the Participants improved significantly in omission error, commission error better in the experimental group than in the control group |

Training |

| Kim S. et al. (2020) | South Korea | Pre-post experimental design | 40 children ADHD: 20 experimental group+ 20 control group (ag e= 8-10; mean age = 8,7) |

Develop and evaluate a MR HMD based eye-contact training game as a treatment tool for children with ADHD | Serius game with MR HMD | Visual sustained attention; impulsivity; | Attention improved significantly, impulsivity partially decreased, and mean response times decreased in the ADHD group. | Training |

| Merzon L. et al. (2022) | Finland | Cross sectional | 73 children (age = 9-13): 37 ADHD group (mean age = 10.5) + 36 control group (mean age = 10.9 years) | Develop a naturalistic VR task (EPELI) combined with eye tracking to detect attention deficits in children with ADHD. | VR with eye tracking | Visual attention | Group differences in all EPELI parameters. The ADHD group showed poorer performance with a greater number of eye movements, longer fixations, and shorter saccades with smaller amplitudes. | Assessment |

| Muhlberger A. et al. (2020) | Germany | Experimental study between-subjects design | 128 children: 34 control group (mean age = 12.17) + 68 unmedicated ADHD (mean age = 11.43) +26 Medicated ADHD = (mean age = 11.89) |

To examine differences in CPT performance in a VRC scenario and correlations with standard questionnaires | CPT-VRC | Impulsivity; attention |

Unmedicated children with ADHD showed greater inattention than both healthy controls and the methylphenidate-medicated group | Assessment |

| Negut A; et al., (2017) | Romania | Mixed design | 75 children (age = 7-13; mean age=9.5): 33 ADHD (mean age=10.24) + 42 control group (mean age = 8.9) | Investigating the discriminant validity of a virtual reality-based measure for assessing attention compared to the CPT test | ClinicaVR Classroom-CPT | Sustained and selective visual attention | ClinicaVR Classroom CPT discriminated between participants with ADHD and healthy controls. Children with ADHD made more errors and had slower reaction times. Reaction times in VR were slower for both groups. |

Assessment |

| Ou YK et al. (2020) | Taiwan | Case study | 3 children with ADHD (ages = 8-12; mean age = 9,6) | Evaluate the use of immersive VR exercise games as a rehabilitation intervention in children with ADHD. | Immersive VR game | Attention; inhibition |

Participants showed improvements in attention, especially focused, sustained, and alternating attention. Reduction of impulsive and oppositional symptoms. | Training |

| Pasarín-Lavín T. et al. (2024) | Spain | Experimental study | 181 children: 159 neurotypical + 22 neurodivergent including 7 ADHD (mean age = 13.5) |

To analyse differences in creativity and EFs components |

VR: Nesplora Executive Functions – Ice Cream | Working memory; planning; cognitive Flexibility | Students with ADHD performed similarly to controls on working memory and planning, but scored higher on Flexibility | Assessment |

| Schena A. et al. (2023). | Italy | Quasi-experimental study | 60 children ADHD (age=5-12; mean age = 8): 30 experimental group + 30 control group | To evaluate the efficacy of IAmHero (VR) in improving symptoms and EFs in children with ADHD. | Serius games (IAmHero) with VR | Selective auditory attention; sustained visual attention; planning; inhibition; problem solving |

Reduction of core ADHD symptoms assessed with standardized instruments | Training |

| Seesjärvi E. et al. (2022) | Finland | Experimental design between subject |

76 children (ages = 9-12): 38 ADHD (mean age = 10.4) + 38 control group (mean age = 10.9) |

Validate the EPELI VR task to quantify goal-directed behaviour and executive symptoms of ADHD in realistic daily life contexts. | EPELI VR task with headset | Selective attention inhibition |

Children with ADHD performed worse on the EPELI than controls. VR performance was correlated with ADHD symptomatology. The EPELI had good discriminant validity and performed better than conventional neuropsychological tests. | Assessment |

| Shema-Shiratzky S. et al. (2019) | Israel | Pilot study, single-group | 14 children with ADHD (ages = 8 - 12; mean age = 9.3) |

Examine the efficacy of a combined motor-cognitive training using VR in non-medicated children with ADHD | Dual-task training (treadmill with virtual obstacle course) using a motion capture camera | Inhibition working memory; flexibility; pianification; attention |

There were significant improvements in EFs and memory, even at the six-week follow-up. There was an improvement in dual-task abilities. There was no significant change in sustained attention or vigilance index. | Training |

| Stokes JD et al. (2022) | USA | Cross-sectional, proof-of-principle observational study | 20 children with ADHD (ages = 8-12; mean age = 10) | Evaluate the temporal dynamics of distraction via eye-tracking measures in a VR classroom setting | VR system connected to a headset with integrated eye tracking. | Sustained and selective attention | Distractors reduced the tendency to look at the board over time, even when the distractor itself was no longer actively present (up to 10 seconds later). Distractors interfered with performance regardless of the task being performed. The greater the distraction, the lower the response to the task. | Assessment |

| Tabrizi M; et al. (2020) | Iran | Quasi-experimental study | 48 ADHD children (age = 7-12): 16 VR group + 16 medication group + 16; control group |

Compare the effectiveness of VR with medication on the memory of ADHD students. | VR therapy software | Working memory | There was a significant difference in memory variables between the control and VR groups and the control and medication groups. Both interventions led to significant improvements in the memory, but VR therapy showed longer-lasting effects than medication |

Training |

| Wong KP et al. (2024) | China | Randomized Controlled Trial | 90 children (ages = 6-12; mean age = 8): 30 VR group + 30 Social VR group + 30 control group | Examine the fleasibility and effectiveness of VR-based social skills training | Social VR intervention | Social Skills; inhibition; emotion regulation |

The VR group performed better in social skills, self-control, initiative, and emotional control than the traditional group |

Training |

| Type of intervention | EFs Domain | VR Approach | Overall Trend |

| Assessment | Attention | VR-CPT, classroom | Strong evidence |

| Planning / Flexibility | EPELI, multitasking VR | Emerging | |

| Training | Inhibition | Immersive VR, serious games | Moderate–strong |

| Working memory | VR + cognitive training | Moderate | |

| Emotional regulation | Social VR scenarios | Emerging |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).