Submitted:

12 January 2026

Posted:

14 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

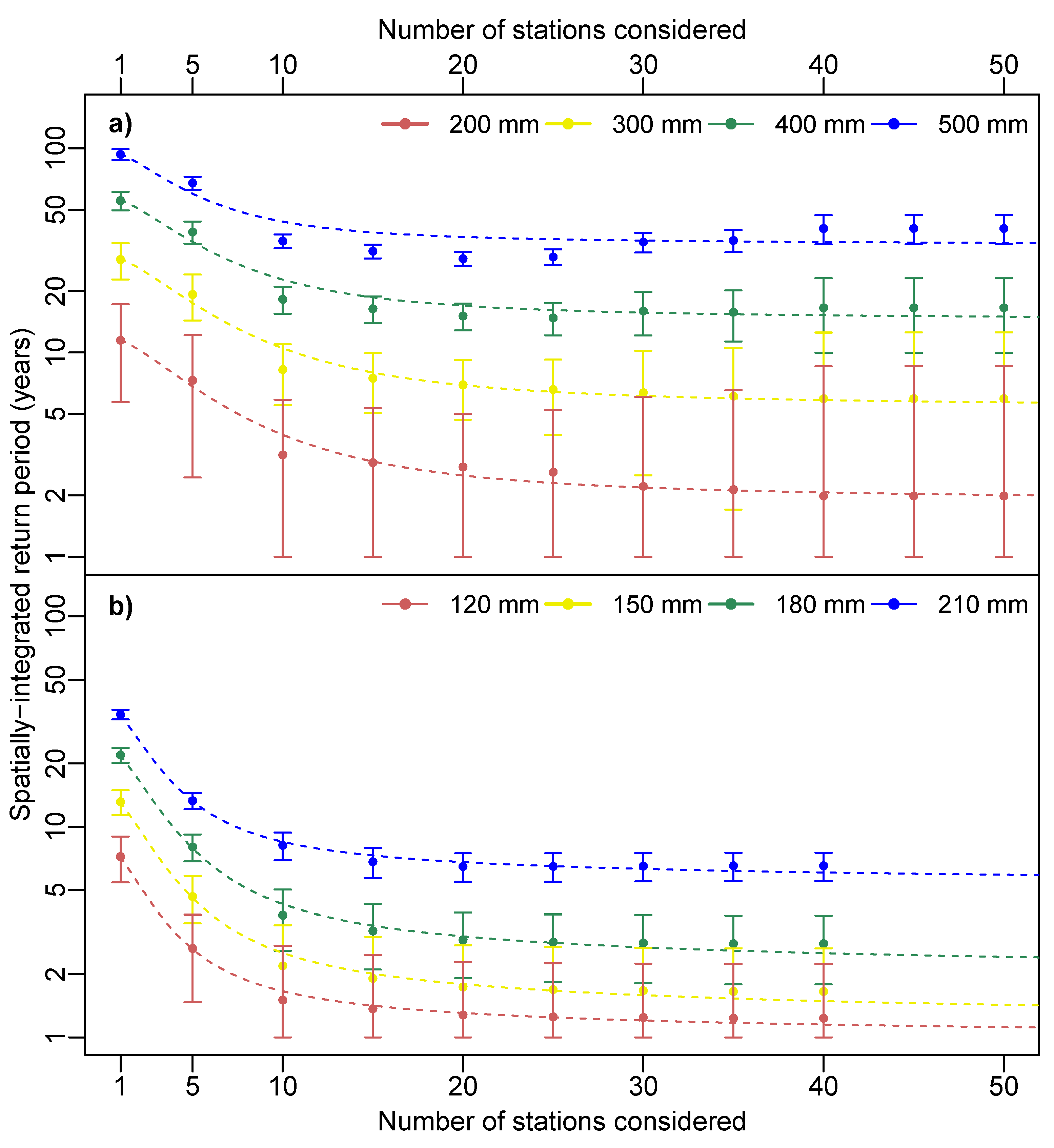

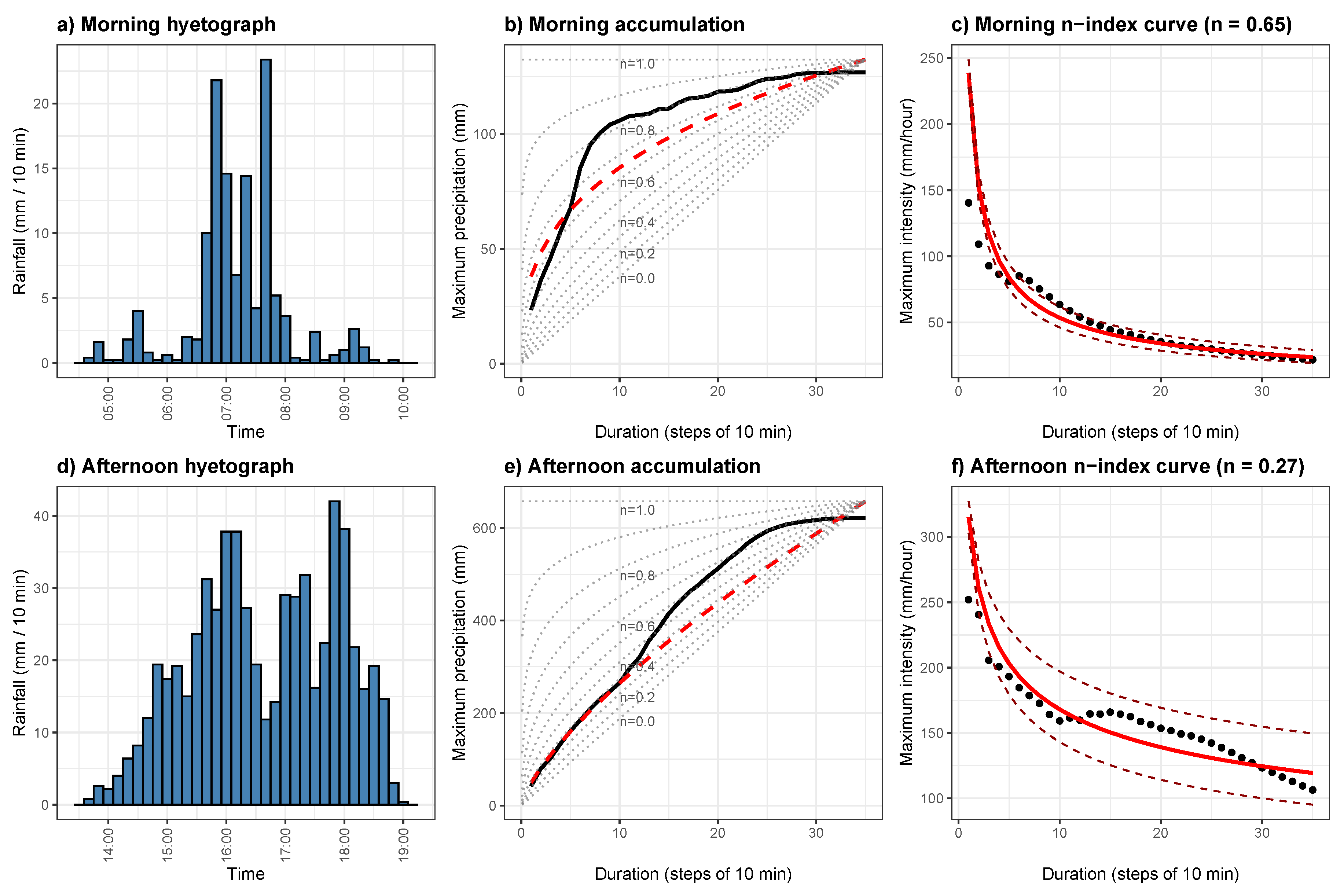

Extreme precipitation poses a major natural hazard in the western Mediterranean, particularly along the Valencia coast, where torrential events recur with significant societal impacts. This study evaluates the feasibility and added value of an explicitly spatial approach for estimating return periods of extreme precipitation in the Júcar and Turia basins, moving beyond traditional point-based or micro-catchment analyses. Our methodology consists of progressive spatial aggregation of time series within a basin to better estimate return periods of exceeding specific catastrophic rainfall thresholds. This technique allows us to compare 10-min rainfall data of a reference station (e.g. Turis, València, 29 October 2024 catastrophe) with long-term annual maxima from 98 stations. Temporal structure is characterized using the fractal−intermittency n index, while tail behavior is modeled using several extreme-value distributions (Gumbel, GEV, Weibull, Gamma, and Pareto) and guided by empirical errors. Results show that n ≈ 0.3−0.4 is consistent for extreme rainfall, while return periods systematically decrease as stations are added, stabilizing with about 15-20 stations, once the relevant spatial heterogeneity is sampled. Specifically, the probability of exceeding extreme thresholds is between 3 and 10 times higher for the areal than the point approach. Overall, the results demonstrate that spatially-integrated return-period estimation is operational, physically consistent, and better suited for basin-scale risk assessment than purely point-based approaches.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

1.2. Episode Recurrence

1.3. Rainfall Concentration

2. Materials and Methods

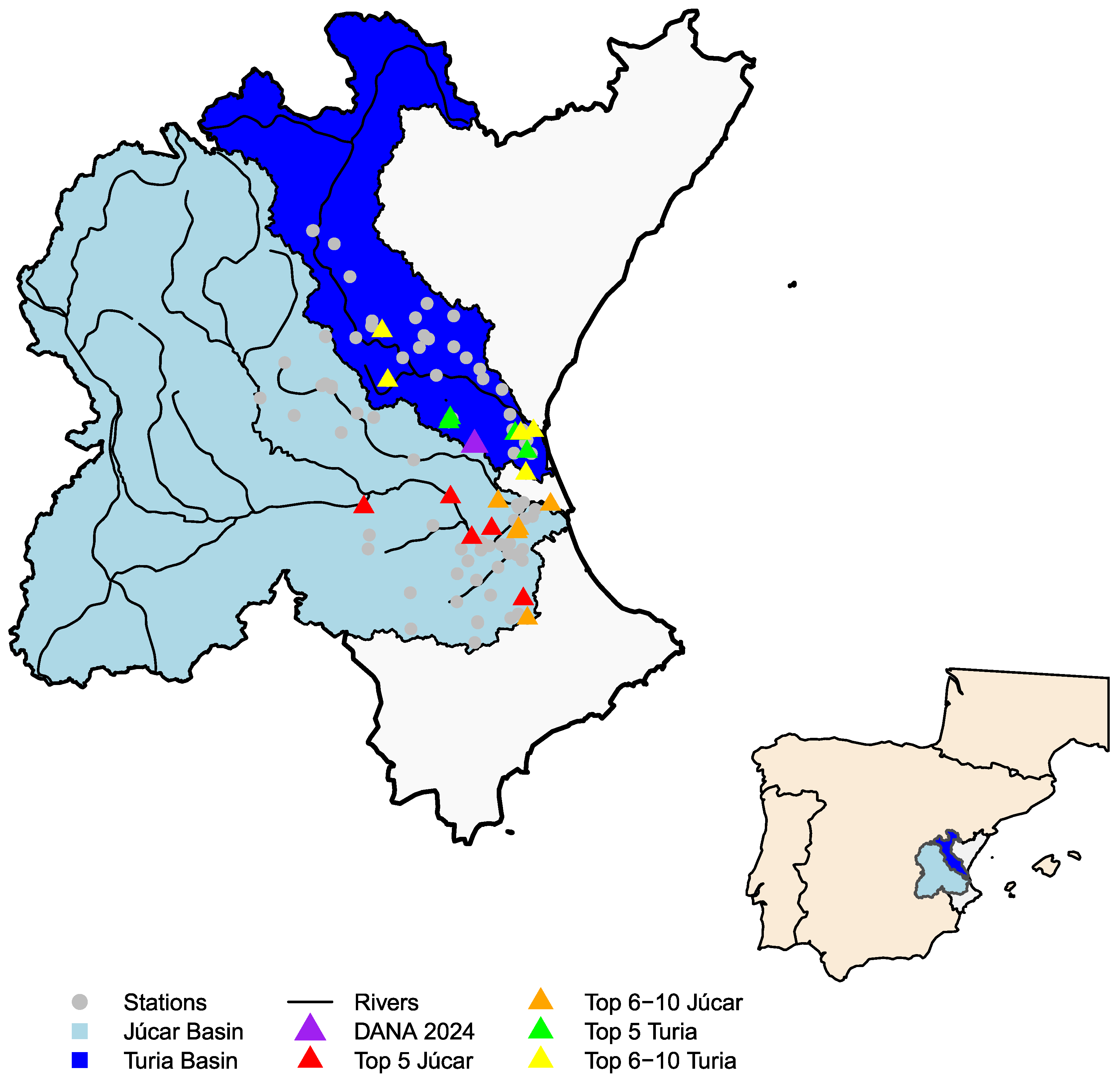

2.1. Observed Data

2.2. Point and Spatially-Integrated Frequency

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Episode Recurrence

2.4. Rainfall-Concentration Comparison

3. Results

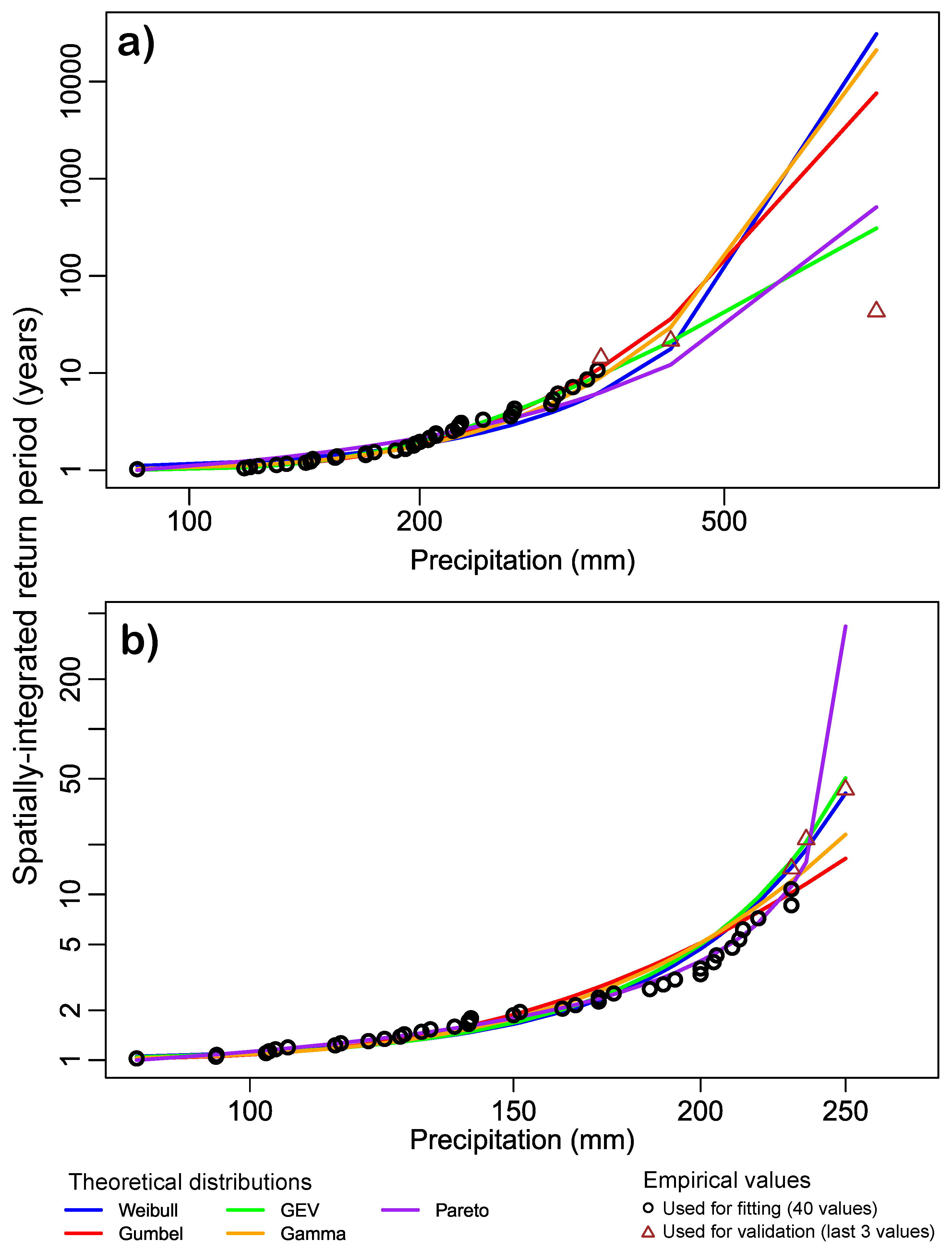

3.1. Episode Recurrence

3.2. Rainfall Concentration

4. Discussions and Conclusions

4.1. Spatially-Integrated Return Periods

4.2. Selection of Theoretical Distributions

4.3. Episode Time Structure

4.4. Final Recommendation

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gonzalez, S.; Bech, J. Extreme point rainfall temporal scaling: a long term (1805–2014) regional and seasonal analysis in Spain. International Journal of Climatology 2017, 37, 5068–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Hidalgo, J.C.; Beguería, S.; Peña-Angulo, D.; Blanco, V.T. Catalogue and Analysis of Extraordinary Precipitation Events in the Spanish Mainland, 1916–2022. International Journal of Climatology 2025, 45, e8785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriopedro, D.; Jiménez-Esteve, B.; Collazo, S.; Garrido-Perez, J.M.; Johnson, J.E.; García-Herrera, R. A Multimethod Attribution Analysis of Spain’s 2024 Extreme Precipitation Event. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2025, 106, E2440–E2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L, A.; L, F.; G, D.B. Increasing flood risk under climate change: a pan-European assessment of the benefits of four adaptation strategies. CLIMATIC CHANGE 2016, 136, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfieri, L.; Dottori, F.; Betts, R.; Salamon, P.; Feyen, L. Multi-Model Projections of River Flood Risk in Europe under Global Warming. Climate 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotz, M.; Lange, S.; Wenz, L.; Levermann, A. Constraining the Pattern and Magnitude of Projected Extreme Precipitation Change in a Multimodel Ensemble. Journal of Climate 2024, 37, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, T.; Wu, P. Anthropogenic amplification of precipitation variability over the past century. Science 2024, 385, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, A.C.; Fowler, H.J.; Blenkinsop, S.; et al. Precipitation extremes in 2024. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 2025, 6, 243–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayan, U.; Nissen, K.; Ulbrich, U. Review Article: Atmospheric conditions inducing extreme precipitation over the eastern and western Mediterranean. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2015, 15, 2525–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrantonas, N.; Herrera-Lormendez, P.; Magnusson, L.; Pappenberger, F.; Matschullat, J. Extreme precipitation events in the Mediterranean: Spatiotemporal characteristics and connection to large-scale atmospheric flow patterns. International Journal of Climatology 2021, 41, 2710–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Garrido-Perez, J.M.; Fernández-Álvarez, J.C.; et al. Characteristics of widespread extreme precipitation events in Peninsular Spain and the Balearic Islands: spatio-temporal dynamics and driving mechanisms. Climate Dynamics 2025, 63, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.M.; Carmona, P.; Pérez Cueva, A. Flood frequency and seasonality of the Jucar and Turia Mediterranean rivers (Spain) during the “Little Ice Age”. Méditerranée. 2014. Online since 19 June 2016. (accessed on 30 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Benito, G.; Díez-Herrero, A. Chapter 3 - Palaeoflood Hydrology: Reconstructing Rare Events and Extreme Flood Discharges. Hydro-Meteorological Hazards, Risks and Disasters 2015, 65–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, B.; Ballesteros-Cánovas, J.A.; Macdonald, N.; Toonen, W.H.; Baker, V.; Barriendos, M.; Benito, G.; Brauer, A.; Corella, J.P.; Denniston, R.; et al. Interpreting historical, botanical, and geological evidence to aid preparations for future floods. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncho, R.; Caselles, V. Potential distribution of extreme rainfall in the Basque Country. Tethys 2011, 8, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Guan, Y.; Li, P.; et al. Quantifying the Impact of Rainfall Spatial Heterogeneity and Patterns on Urban Flooding by Integrating Machine Learning Algorithm and Hydrodynamic–Hydrological Modeling. Water Resources Management 2026, 40, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, P.; Brunner, M.; Opitz, T.; Huser, R. Spatial Modeling and Future Projection of Extreme Precipitation Extents. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2025, 120, 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.T.; Qian, J.L.; Jiang, X.J.; Wu, Y.X.; Yu, P.B. Spatial Dependence of Conditional Recurrence Periods for Extreme Rainfall in the Qiantang River Basin: Implications for Sustainable Regional Disaster Risk Governance. Sustainability 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, I.; Cea, L.; Puertas, J. Effect of rainfall uncertainty on the performance of physically based rainfall–runoff models. Hydrological Processes 2019, 33, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjo, R. Measure of rainfall time structure using the dimensionless n-index. Clim. Res. 2016, 67, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjo, R.; Martin-Vide, J. Daily precipitation concentration around the world according to several indices. International Journal of Climatology 2016, 36, 3828–3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbazo, M.N.; Adéchinan, J.A.; N’gobi, G.K.; Bessou, J. Analysis and Predictability of Dry Spell Lengths Observed in Synoptic Stations of Benin Republic (West Africa). American Journal of Climate Change 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjo, R.; Locatelli, L.; Milligan, J.; Torres, L.; Velasco, M.; Gaitan, E.; Portoles, J.; Redolat, D.; Russo, B.; Ribalaygua, J. Estimation of future extreme rainfall in Barcelona (Spain) under monofractal hypothesis. Int. J. Climatol. 2023, 163, 4047–4068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacon, B.; Santuy, D.; Redolat, D. Temporal Distribution of Extreme Precipitation in Barcelona (Spain) under Multi-Fractal n-Index with Breaking Point. Atmosphere 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collar, N.M.; Moody, J.A.; Ebel, B.A. Rainfall as a driver of post-wildfire flooding and debris flows: A review and synthesis. Earth-Science Reviews 2025, 260, 104990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monjo, R.; Gaitán, E.; Pórtoles, J.; Ribalaygua, J.; Torres, L. Changes in extreme precipitation over Spain using statistical downscaling of CMIP5 projections. International Journal of Climatology 2016, 36, 757–769. Available online: https://rmets.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/joc.4380. [CrossRef]

- Monjo, R.; Royé, D.; Martin-Vide, J. Meteorological drought lacunarity around the world and its classification. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 741–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delignette-Muller, M.L.; Dutang, C. fitdistrplus: An R Package for Fitting Distributions. Journal of Statistical Software 2015, 64, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, A.G. evd: Extreme Value Distributions. R News 2002, 2, 31–32. [Google Scholar]

| Júcar basin | Turia basin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Distribution | MAE | RMSE | MAE | RMSE |

| Fitting | Weibull | 0.80 | 1.67 | 0.65 | 1.31 |

| Gumbel | 0.26 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 1.01 | |

| GEV | 0.28 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 1.68 | |

| Gamma | 0.44 | 0.98 | 0.65 | 1.04 | |

| Pareto | 0.72 | 1.62 | 0.28 | 0.68 | |

| Validation | Weibull Pred. | 15400 | 22000 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Gumbel Pred. | 3800 | 5300 | 18 | 20 | |

| GEV Pred. | 133 | 188 | 4.1 | 5.3 | |

| Gamma Pred. | 10500 | 14900 | 13.6 | 15.0 | |

| Pareto Pred. | 240 | 330 | 190 | 270 | |

| Threshold [] | (years) | (years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Júcar | 200 mm | ||||

| 300 mm | |||||

| 400 mm | |||||

| 500 mm | |||||

| Turia | 120 mm | ||||

| 150 mm | |||||

| 180 mm | |||||

| 210 mm |

| Date | Station | Basin | (mm) | n | (mm) | (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20/10/1982 | Casas del Baró | Júcar | 140 | 0.37 | 21.8 | |

| 03/11/1987 | Gandia | Serpis | 154 | 0.42 | 26.3 | |

| 03/11/1987 | Oliva | Serpis | 150 | 0.41 | 817 | 17.7 |

| 22/10/2000 | Carlet | Júcar | 60 | 0.35 | 532 | 28.7 |

| 12/10/2007 | Alcalalí | Xaló–Gorgos | 90 | 0.35 | 440 | 11.5 |

| 23/09/2008 | Sueca | Júcar | 142 | 0.14 | 350 | 2.9 |

| 29/10/2024 | Turís | Turia-Jucar | 180 | 0.27 | 772 | 7.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).