Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

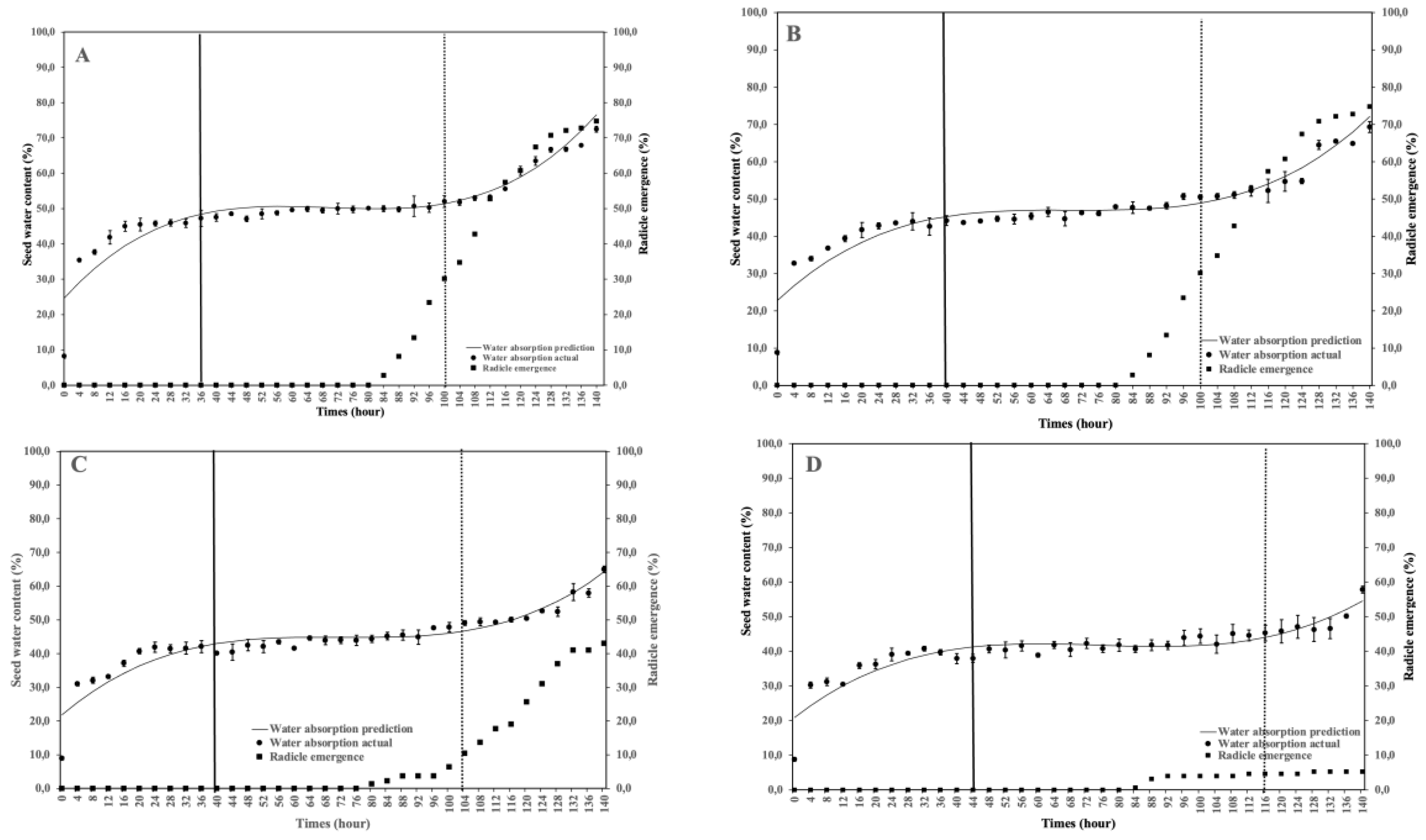

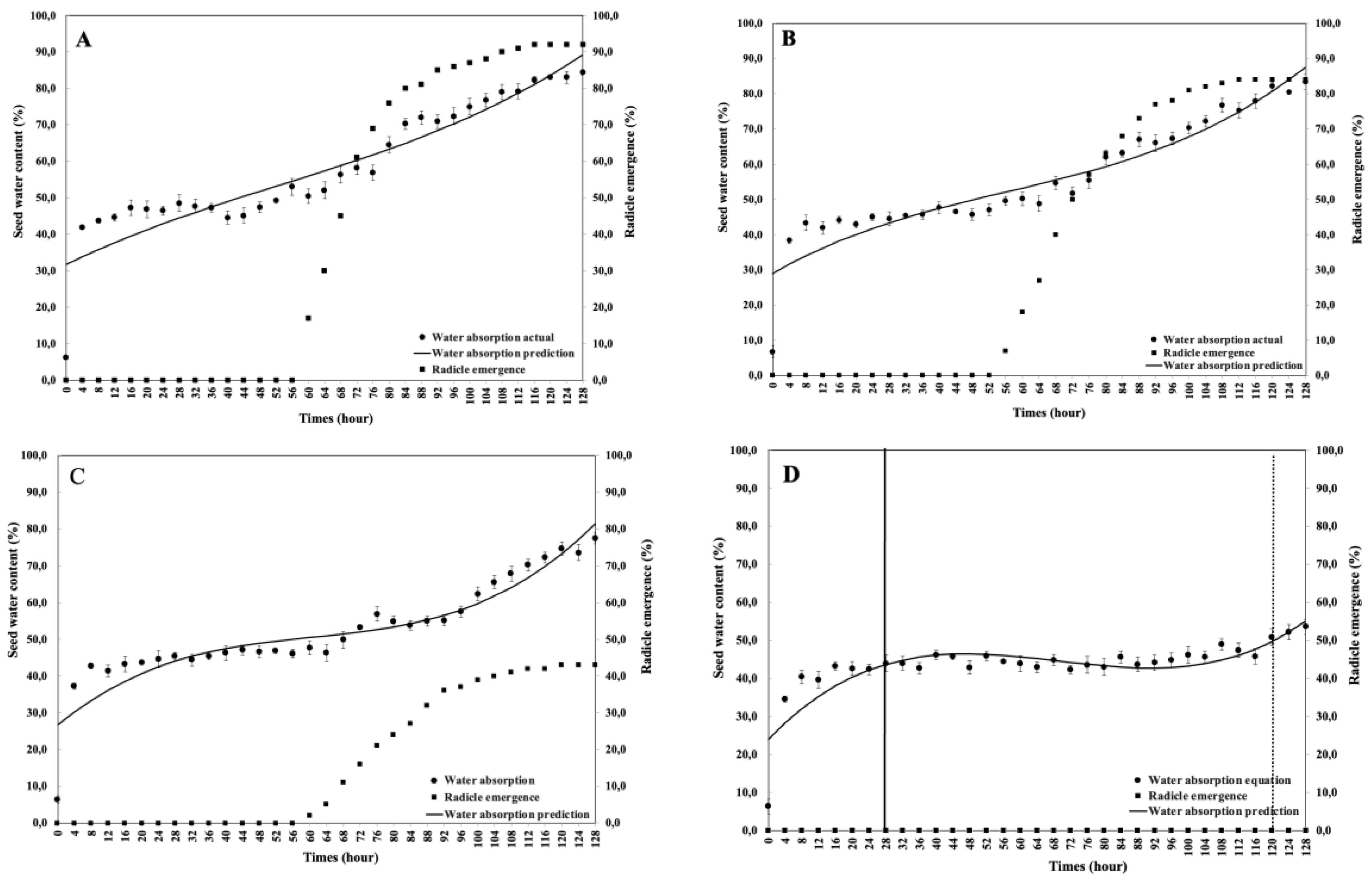

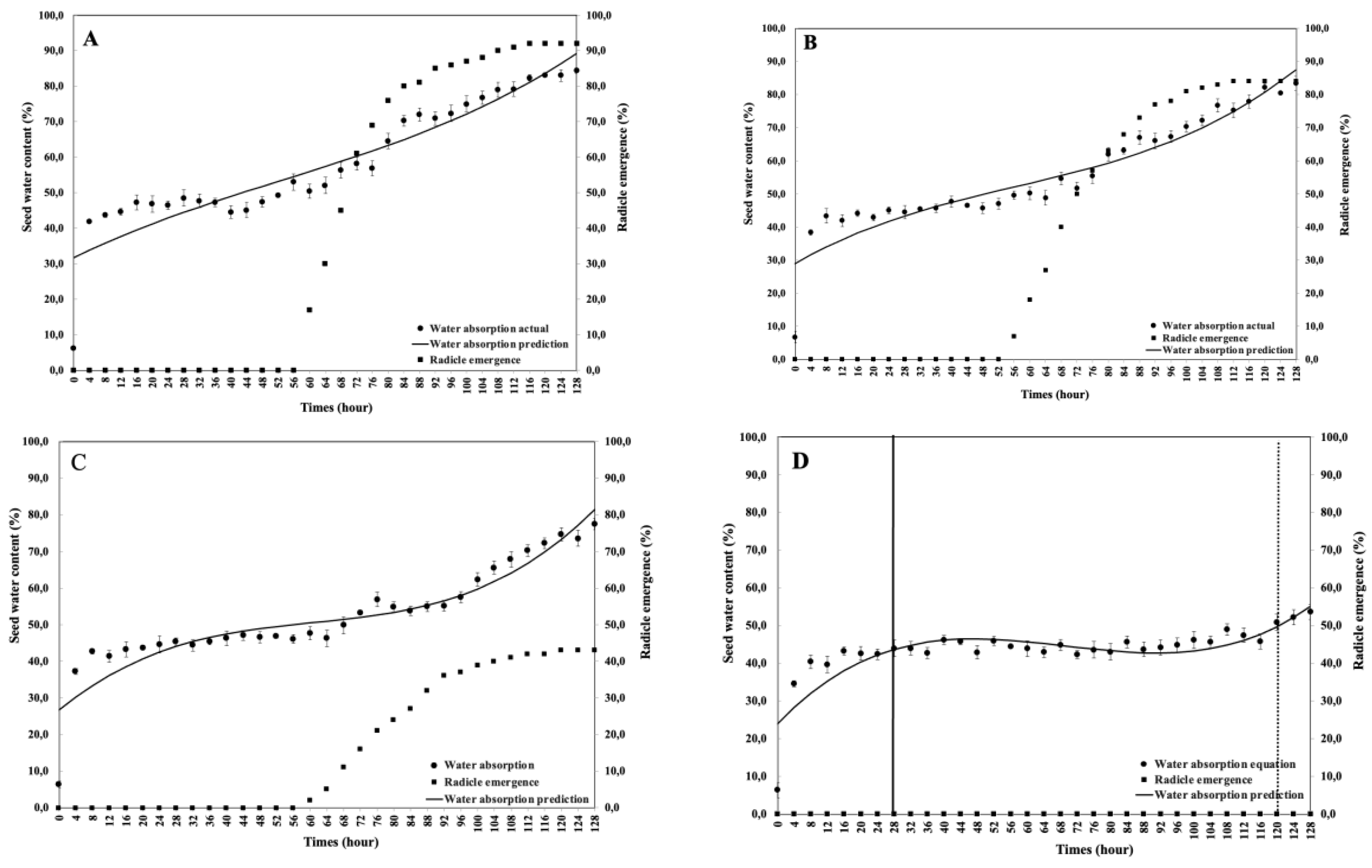

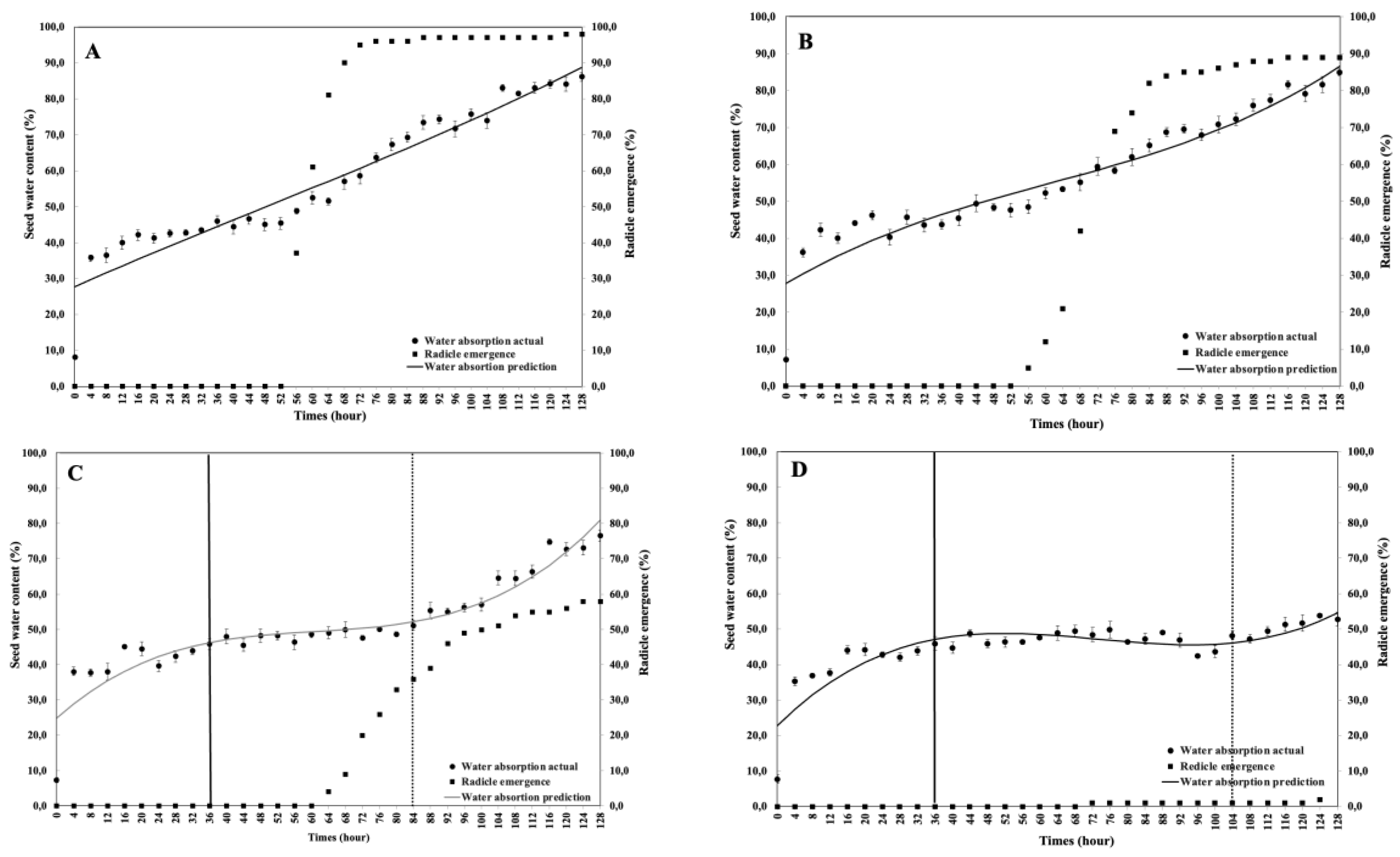

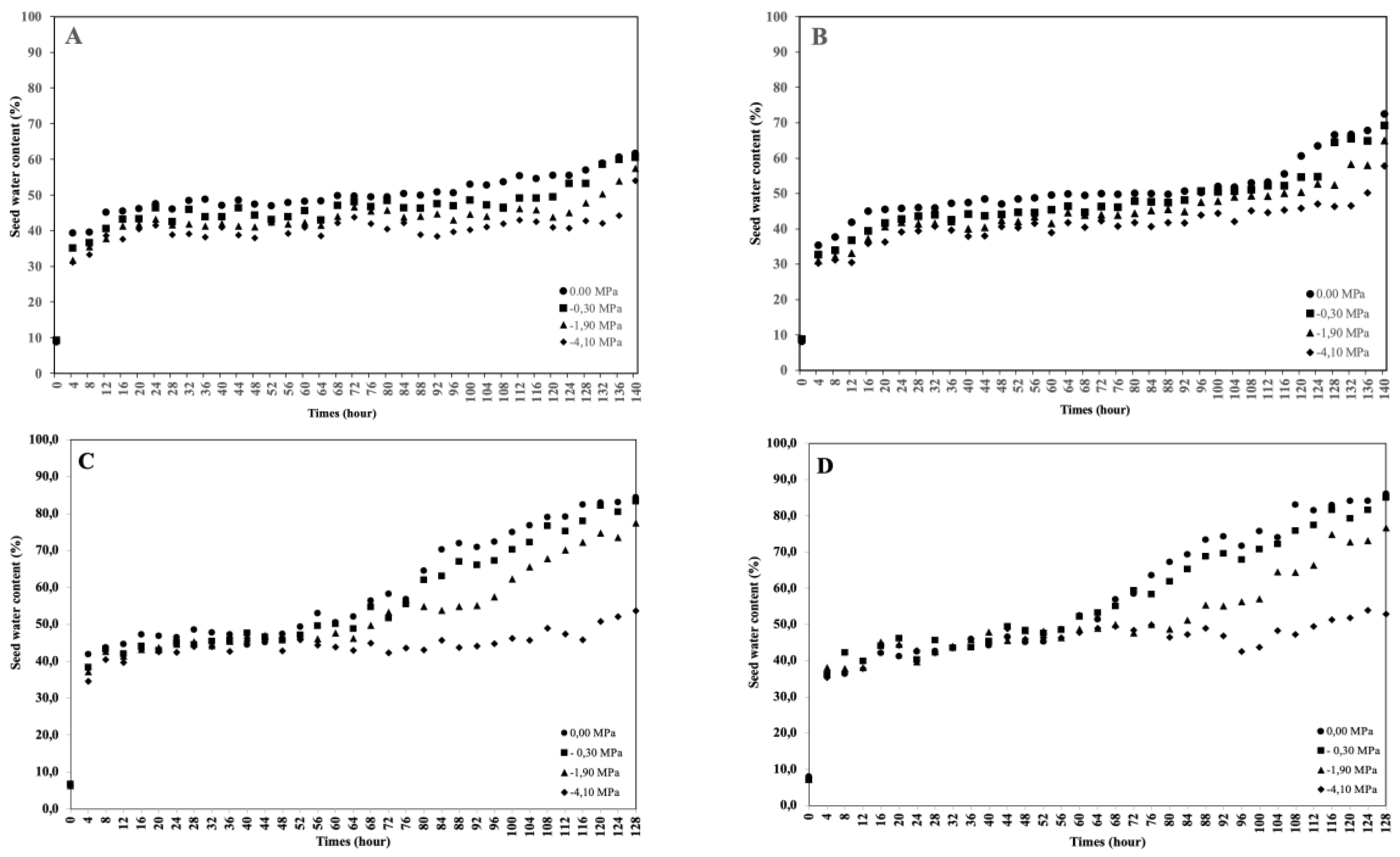

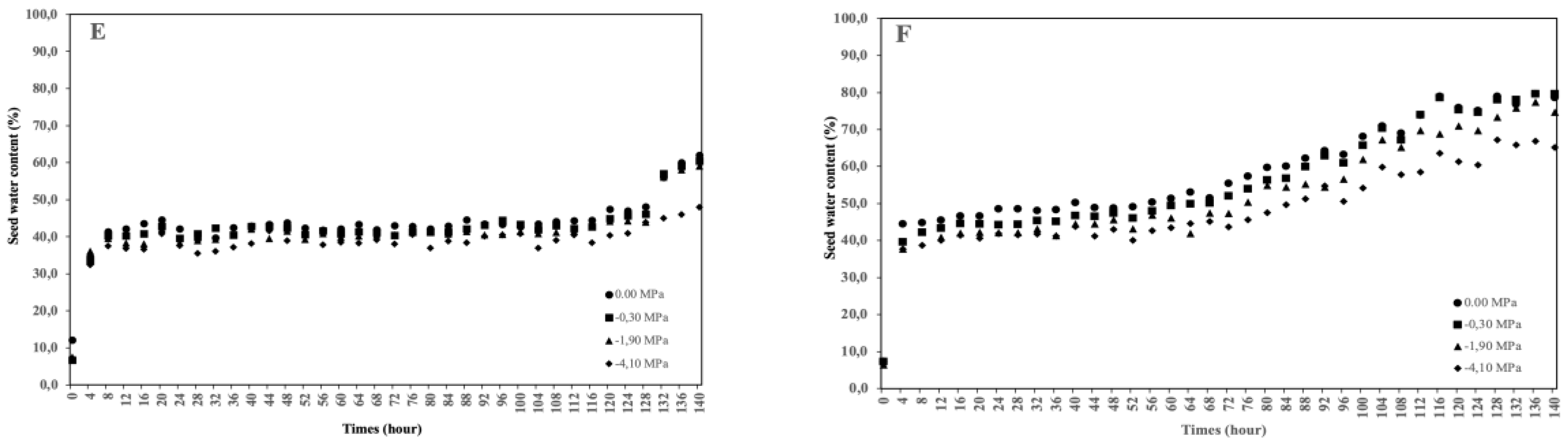

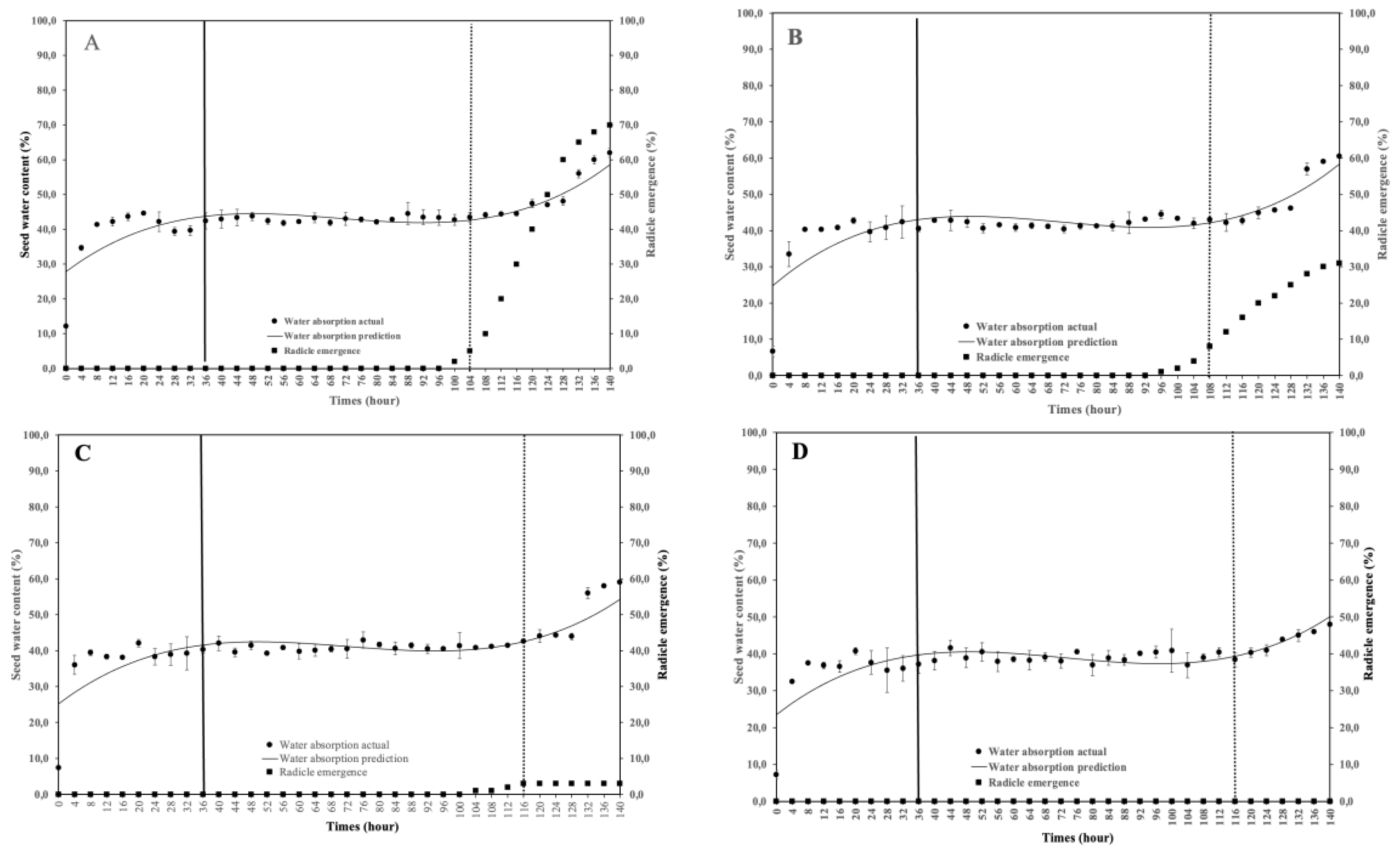

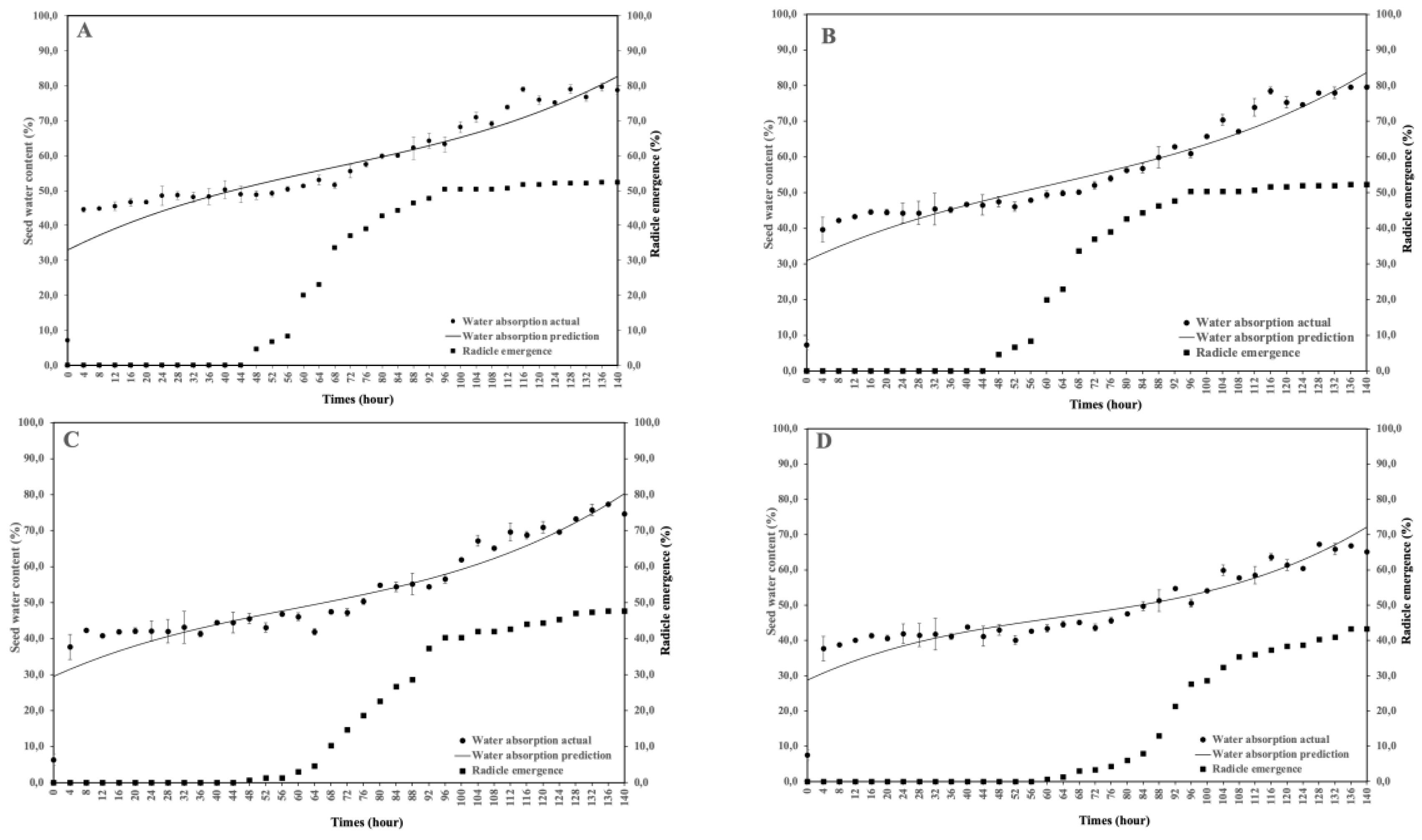

This study aimed to analyze the effect of reduced water potential on the imbibition curve and triphasic pattern of seeds in several Solanaceae species. The experiment was conducted at the Seed Physiology and Health Laboratory and the Seed Biology and Biophysics Laboratory, Department of Agronomy and Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Bogor Agricultural University, from April to September 2025. The study used seeds from three Solanaceae crops—chili (Capsicum annuum L., varieties Simpatik and Sempurna), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L., varieties Niki and Rempai), and eggplant (Solanum melongena L., varieties Tangguh and Provita). The seeds were subjected to various levels of osmotic stress using polyethylene glycol (PEG 6000) to simulate water potentials of 0.00, –0.30, –1.90, and –4.10 MPa. Lower water potential in the growing medium reduced the seed’s ability to absorb the water. The triphasic pattern consistently appeared only in chili seeds, whereas in tomatoes and eggplants, it varied across varieties and water potential conditions. The lower water potential made the later the phase I ended, and the longer the phase II lasted. These findings confirm that the standard imbibition pattern cannot be generalized to all seeds, and therefore, the imbibition response is specific to seed type, variety, and germination environment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bradford, KJ. A Water Relations Analysis of Seed Germination Rates. Plant Physiol 1990, 94, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, A.R.; Rashidi, S.; Moradi, P.; Mastinu, A. Germination and Seedling Growth Responses of Zygophyllum fabago, Salsola kali L. and Atriplex canescens to PEG-Induced Drought Stress. Environments 2020, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bewley, J.D.; Black, M. Seeds Physiology of Development and Germination, 3rd. ed; Plenum Press: New York; 445p.

- Niu, J.; Xu, M.; Zong, N.; Sun, J.; Zhao, L.; Hui, W. Ascorbic acid releases dormancy and promotes germination by an integrated regulation of abscisic acid and gibberellin in Pyrus betulifolia seeds. Physiol Plant 2024, 176, e14271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, H.A.; Ullah, S.; Shah, W.; Ali, B.; Satti, S.Z.; Ullah, R.; et al. Seed Priming Modulates Physiological and Agronomic Attributes of Maize (Zea mays L.) under Induced Polyethylene Glycol Osmotic Stress. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 22788–22808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, P.A.; Kumar, R.; Rehal, P.K.; Toora, P.K.; Ayele, B.T. Molecular mechanisms underlying abscisic acid/gibberellin balance in the control of seed dormancy and germination in cereals. Front Plant Sci 2018, 9, 362906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompelli, M.F.; Jarma-Orozco, A.; Rodriguez-Páez, L.A. Imbibition and Germination of Seeds with Economic and Ecological Interest: Physical and Biochemical Factors Involved. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, P.; Abdin, M.Z. Water deficit-induced oxidative stress affects artemisinin content and expression of proline metabolic genes in Artemisia annua L. FEBS Open Bio 2017, 7, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Shao, S.; Wang, Y.; Qi, M.; Lin, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Germination responses of the halophyte Chloris virgata to temperature and reduced water potential caused by salinity, alkalinity and drought stress. Grass and Forage Science 2016, 71, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khetsha, Z.; van der Watt, E.; Masowa, M.; Legodi, L.; Satshi, S.; Sadiki, L.; et al. Phytohormone-Based Biostimulants as an Alternative Mitigating Strategy for Horticultural Plants Grown Under Adverse Multi-Stress Conditions: Common South African Stress Factors. Caraka Tani: Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 2024, 39, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R. The Solanaceae family: Botanical features and diversity; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Megersa, H.G. Potential Effects of Salt Stress on Selected Solanaceous Crops (Tomato (Solanum esculentum L.) and Hot Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.)) Production. Journal of Agricultural Science and Food Research 2022, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pessoa, H.P.; de Carvalho Rocha, J.R.D.A.S.; Alves, F.M.; Copati, M.G.F.; Dariva, F.D.; da Silva, L.J.; et al. Multi-trait selection of tomato introgression lines under drought-induced conditions at germination and seedling stages. Acta Sci Agron 2022, 44, e55876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barris, S.; Toumi, M.; Belkebir, A. Effect of osmotic and salt stresses on germination and phenolic compounds of Eruca vesicaria subs. sativa L. Research square 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, C.; Bagavathiannan, M.; Wang, H.; Sharpe, S.M.; Meng, W.; Yu, J. Osmopriming with Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) for Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Germinating Crop Seeds: A Review. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radić, V.; Balalić, I.; Cvejić, S.; Jocić, S.; Marjanović-Jeromela, A.; Miladinović, D. Drought effect on maize seedling development. Ratarstvo i povrtarstvo 2018, 55, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mexal, J.; Fisher, J.T.; Osteryoung, J.; Reid, C.P.P. Oxygen Availability in Polyethylene Glycol Solutions and Its Implications in Plant-Water Relations. Plant Physiol 1975, 55, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISTA. International Rules for Seed Testing 2018. Available online: https://www.tarimorman.gov.tr/BUGEM/TTSM/Belgeler/Duyuru%20Belgeleri/ISTA%20Rules%202018.pdf.

- Bewley, J.D.; Bradford, K.J.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Nonogaki, H. Seeds: Physiology of Development, Germination and Dormancy, 3rd. ed; Springer: New York, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upretee, P.; Bandara, M.S.; Tanino, K.K. The Role of Seed Characteristics on Water Uptake Preceding Germination. Seeds 2024, 3, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeller, H.; Perez, S.C.; Raizer, J. Water uptake, priming, drying and storage effects in Cassia excelsa Schrad seeds. Braz J Biol 2003, 63(1), 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, W.V.S.; José, A.C.; Tonetti, O.A.O.; de Melo, L.A.; Faria, J.M.R. Imbibition curve in forest tree seeds and the triphasic pattern: theory versus practice. South African Journal of Botany 2022, 144, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresch, D.M.; Quintão Scalon, S.de.P.; Elisa Masetto, T.; do Carmo Vieira, M. Germinação e vigor de sementes de gabiroba em função do tamanho do fruto e semente. Pesqui Agropecu Trop 2013, 43, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.V.; De Lima E Borges, E.E.; Guimarães, V.M.; Da Mata Ataíde, G.; Castro, R.V.O. Germinação de sementes de Melanoxylon brauna schott em diferentes temperaturas. Revista Árvore 2014, 38, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seethalakshmi, S.; Umarani, R.; Maduraimuthu, D. Gibberellic Acid Biosynthesis During Dehydration Phase of Priming Increases Seed Vigour of Tomato. Research square 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, S.; Balestrazzi, A.; Madsen, M.D.; Bhalsing, K.; Hardegree, S.P.; Dixon, K.W.; et al. Seed enhancement: getting seeds restoration-ready. Restor Ecol 2020, 28, S266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.B.; Raj, S.K. Seed priming: An approach towards agricultural sustainability. Journal of Applied and Natural Science 2019, 11, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechowska, K.; Kubala, S.; Wojtyla, Ł.; Nowaczyk, G.; Quinet, M.; Lutts, S.; et al. New Insight on Water Status in Germinating Brassica napus Seeds in Relation to Priming-Improved Germination. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gama, G.F.V.; Brum, L.B.T.L.; Martins, M.S.; da Silva, L.J.; Dias, D.C.F. dos.S. Silicon in wheat crop under water limitation and seed tolerance to water stress during germination. Revista Ceres 2021, 68, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Zong, J.; Zhang, J.; Wei, L.; Wei, W.; Fan, R.; et al. Effects of temperature and drought stress on the seed germination of a peatland lily (Lilium concolor var. megalanthum). Front Plant Sci 2024, 15, 1462655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling-Yun, W.; Jun, Y.; Zhi-Wu, H.; Yan-Hui, W.; Wei-Min, Z. Solid matrix priming improves cauliflower and broccoli seed germination and early growth under the suboptimal temperature conditions. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0275073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, K.; Cheng, Y.; Pan, T.; Wang, J.; Sun, Q. Effects of Seed Priming on Vitality and Preservation of Pepper Seeds. Agriculture 2022, 12, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueridi, S.; Boucelha, L.; Abrous-Belbachir, O.; Djebbar, R. Effects of hormopriming and pretreatment with gibberellic acid on fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) seed germination. Acta Bot Croat 2024, 83, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhone, P.R.; Lopes, J.C.; Alexandre, R.S.; Lima, P. A. M.; Lopes, S.O.; Mengarda, L.H.G.; et al. Plant growth regulators and mobilization of reserves in imbibition phases of yellow passion fruit. Brazilian Journal of Biology 2024, 84, e273999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Wang, L.; Zeng, P.; He, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, H.; et al. Identification of genes involved in rice seed priming in the early imbibition stage. Plant Biol 2017, 19, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adhikari, B.; Dhital, P.R.; Ranabhat, S.; Poudel, H. Effect of seed hydro-priming durations on germination and seedling growth of bitter gourd (Momordica charantia). PLoS One 2021, 16, e0255258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Varieties | Water potential (MPa) | Equations | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capsicum annuum (chili) seeds | |||

| Simpatik | 0.00 | y = 28.41 + 0.9474x – 0.01308x2 + 0.000058x3 | 74.60% |

| -0.30 | y = 25.40 + 1.007x – 0.01479x2 + 0.000068x3 | 79.08% | |

| -1.90 | y = 23.82 + 0.9517x – 0.01371x2 + 0.000061x3 | 75.93% | |

| -4.10 | y = 23.25 + 0.8854x- 0.01295x2 + 0.000057x3 | 66.69% | |

| Sempurna | 0.00 | y = 24.70 + 1.183x–0.01756x2 + 0.000084x3 | 88.17% |

| -0.30 | y = 22.80 + 1.056x–0.01525x2 + 0.000073x3 | 90.21% | |

| -1.90 | y = 21.88 + 0.9706x–0.01359x2 + 0.000063x3 | 88.75% | |

| -4.10 | y = 20.92 + 0.9085x–0.01261x2 + 0.000056x3 | 84.19% | |

| Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) seeds | |||

| Niki | 0.00 | y = 31.69 + 0.5415x – 0.003663x2 + 0.000023x3 | 86.81% |

| -0.30 | y = 28.96 + 0.6800x – 0.007114x2 + 0.000042x3 | 89.10% | |

| -1.90 | y = 26.66 + 0.9450x – 0.01364x2 + 0.000075x3 | 87.08% | |

| -4.10 | y = 23.92 + 1.152x – 0.01849 x2 + 0.000089x3 | 69.31% | |

| Rempai | 0.00 | y = 27.73 + 0.4884x – 0.000857x2 + 0.000006x3 | 92.81% |

| -0.30 | y = 27.70 + 0.6985x – 0.006216x2 + 0.000034x3 | 91.06% | |

| -1.90 | y = 24.89 + 1.064x – 0.01628x2 + 0.000089x3 | 88.72% | |

| -4.10 | y = 22.85 + 1.223x – 0.01824x2 + 0.000083x3 | 76.31% | |

| Solanum melongena (eggplant) seeds | |||

| Tangguh | 0.00 | y = 27.87 + 0.8366x – 0.01323x2 + 0.000063x3 | 56.95% |

| -0.30 | y = 24.77 + 0.9524x – 0.01489x2 + 0.000070x3 | 56.35% | |

| -1.90 | y = 25.20 + 0.8414x – 0.01293x2 + 0.000060x3 | 53.13% | |

| -4.10 | y = 23.46 + 0.8380x – 0.01289x2 + 0.000059x3 | 54.21% | |

| Provita | 0.00 | y = 33.04 + 0.5616x – 0.004695x2 + 0.000023x3 | 84.74% |

| -0.30 | y = 30.89 + 0.5236x – 0.004264x2 + 0.000023x3 | 88.03% | |

| -1.90 | y = 29.44 + 0.5111x – 0.004839x2 + 0.000027x3 | 86.63% | |

| -4.10 | y = 28.78 + 0.5251x – 0.005739x2 + 0.000030 x3 | 82.48% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).