Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

26 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

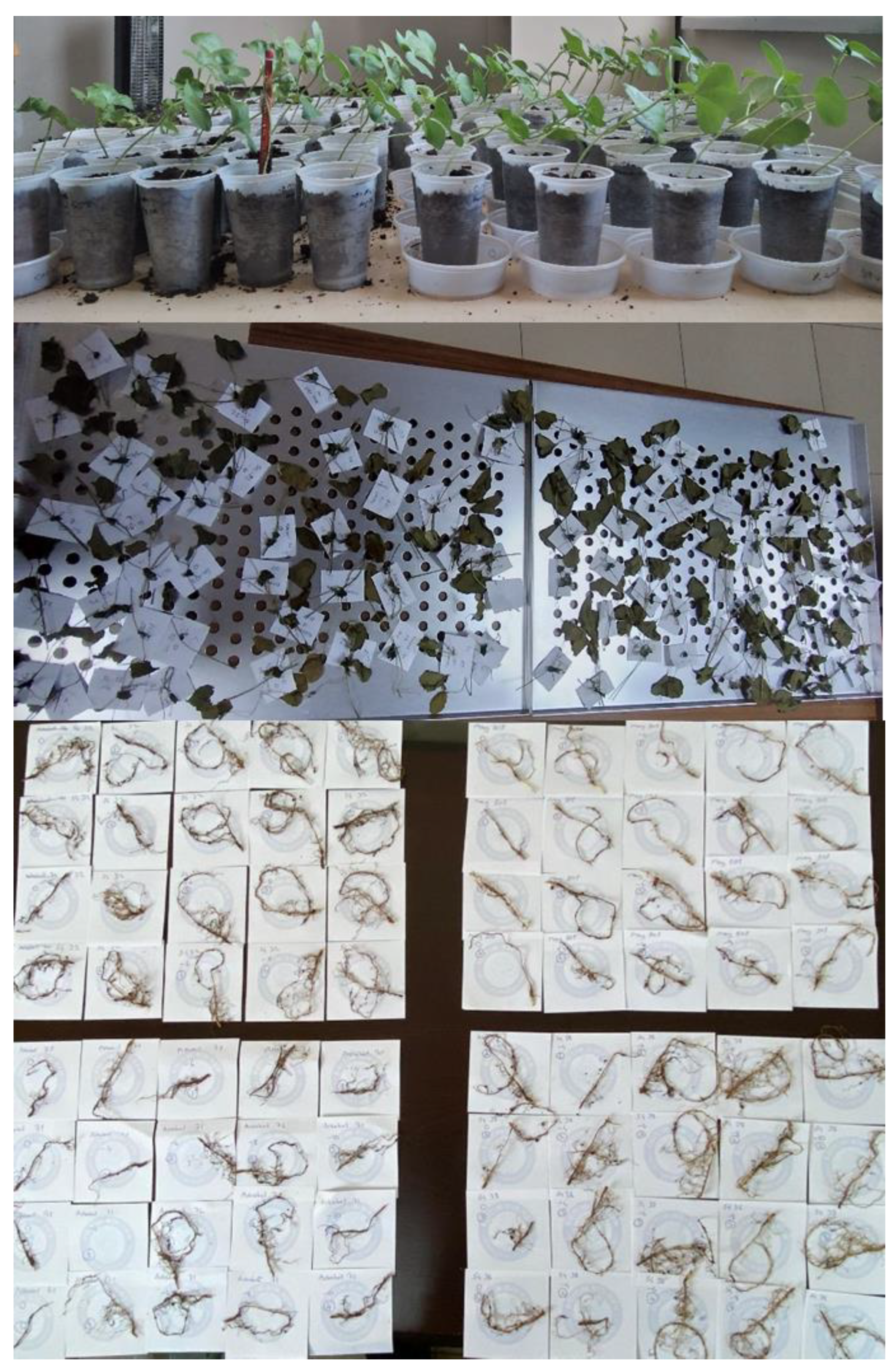

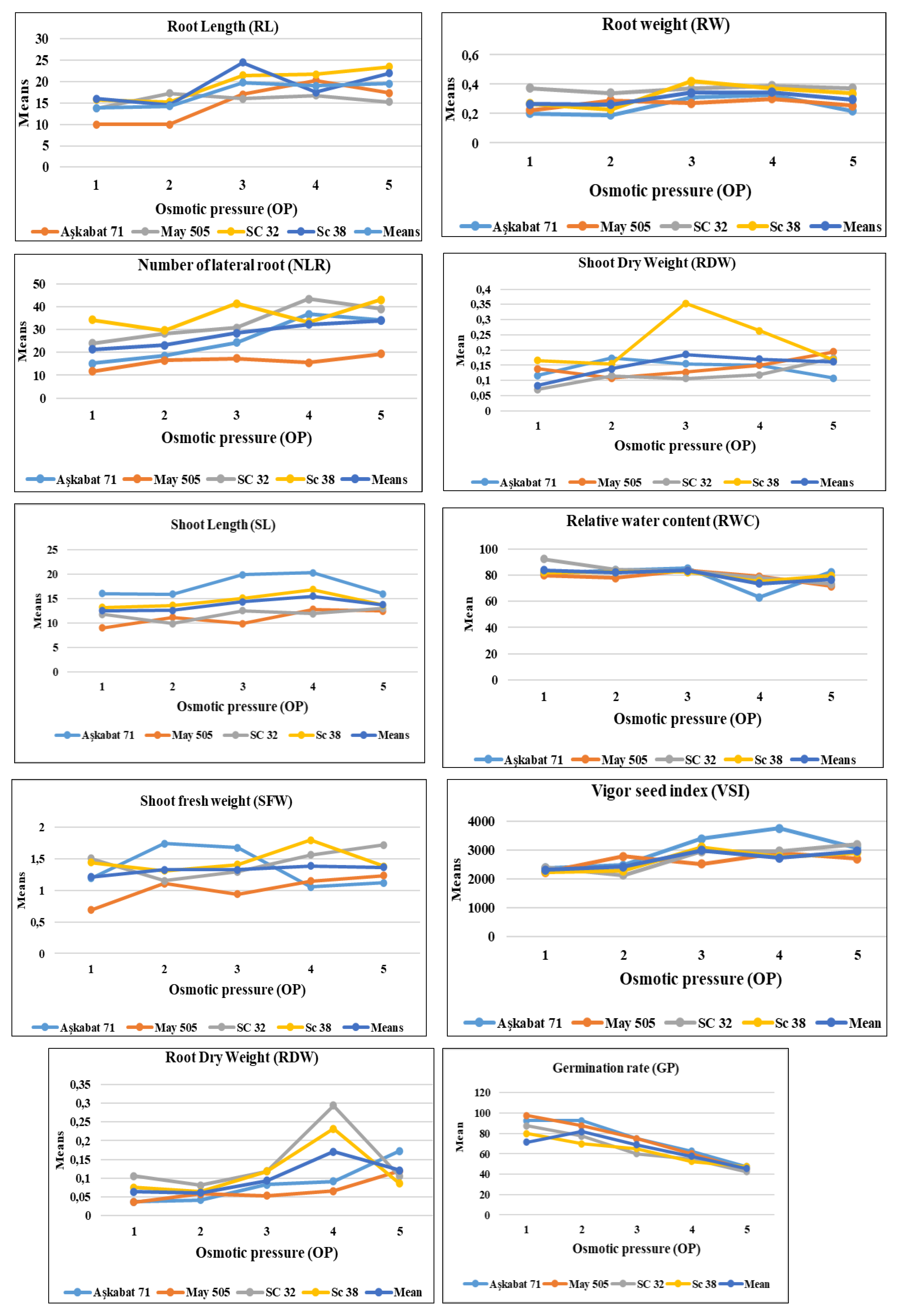

This laboratory experiment was conducted in the Forestry Department of Bingöl University, Vocational School of Youth, in 2023. It aimed to investigate the responses of cotton genotypes to drought stress by creating osmotic pressure stresses of 0 MPa (control), -4 MPa, -6 MPa, -8 MPa, and -10 MPa using PEG 6000 chemical on the advanced lines SC32 and SC38, as well as the varieties Aşkabat 71 and May 505. Various parameters such as Root length (RL), Root Fresh Weight (RFW), Root Dry Weight (RDW), Shoot Length (SL), Shoot Fresh Weight (SFW), Shoot Dry Weight (SDW), Relative Water Content (RWC), Germination percent (GP), Vigor Seed Index (VSI), and Number of Lateral roots (NLRs) were measured. It was observed that as the severity of drought increased, the root system expanded in parallel. However, the plant’s tolerance decreased with increasing drought severity. The genotypes SC32 and SC38, which were obtained from the breeding program for developing drought-tolerant varieties, exhibited high averages in almost all drought measurement parameters, demonstrating a high level of heterosis. As a conclusion, continuing the breeding program with these genotypes was found tolerant to contribute to the success of breeding. May 505 variety showed high tolerance to drought in terms of Relative Water Content (RWC), and it also exhibited promising results in other parameters compared to G. barbadense variety Aşkabat 71 and segregating population genotypes. May 505 variety showed a high germination rate and rapid germination, suggesting its potential use as a parent in both drought and early variety breeding programs.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant materials

2.2. Method

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang Y.; Fan, Y.; Rui, C.; Zhang, H.; Xu, N.; Dai, M.; Chen, X.; Lu, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; Chen, C.; Guo, L.; Zhao, L.; Ye, W. Melatonin improves cotton salt tolerance by regulating ROS scavenging system and Ca2+ signal transduction. Front Plant Sci. 2021, 28;12: 693690. [CrossRef]

- Grayson, M. Agriculture and drought. Nature, 2013,501: S1.

- Saranga, Y.; Paterson, A.H.; Levi, A. Bridging classical and molecular genetics of abiotic stress resistance in cotton. genet. Genom. Cott. 2009, 3. 337–352. [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.H.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought stress impacts on plants and different approaches to alleviate its adverse effects. Plants (Basel). 2021, 28;10. [CrossRef]

- Abdelraheem, A.; Esmaeili, N.; O’Connell, M.; Zhang, J. Progress and perspective on drought and salt stress tolerance in cotton. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 130. 118–129. [CrossRef]

- Li et al., 2009 a.

- Li et al., 2009 b.

- Parida, A. K.; Dagaonkar, V. S. Phalak, M. S.; Aurangabadkar, L. P. Differential responses of the enzymes involved in proline biosynthesis and degradation in drought tolerant and sensitive cotton genotypes during drought stress and recovery. Acta Physiol. Plant, 2008, 30. 619–627. [CrossRef]

- Chen et al., 2007.

- Hu, Y.; Jiedan, C.; Lei, F.; Zhiyuan, Z.; Wei, M.; Yongchao, N.. et al. Gossypium barbadense and Gossypium hirsutum genomes provide insights into the origin and evolution of allotetraploid cotton. Nat. Genet. 2019, 51 739–748. [CrossRef]

- Chaves, M. M.; Maroco, J. P.; Pereira, J. S. Understanding plant responses to drought—from genes to the whole plant. Funct. Plant Biol. 2003, 30:239. [CrossRef]

- Gadallah, M. A. A. Effect of water stress. abscisic acid. and proline on cotton plants. J. Arid Environ. 1995, 30 315–325. [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.; Rasul, E. “Photosynthesis in leaf. stem. flower. and fruit.” in Handbook of Photosynthesis. 2nd Edn. ed. Pessarakli M. (Boca Raton. FL: CRC Press;). 2005, 479–497.

- Iqbal, M.; Khan, M.A.; Naeem, M.; Aziz, U.; Afzal, J.; Latif, M. (2013) Inducing drought tolerance in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Accomplishments and future prospects. World Appl Sci J. 2013, 21:1062–1069. [CrossRef]

- Cornic, G.; Massacci, A. “Leaf photosynthesis under drought stress.” in Photosynthesis and the Environment. ed. Baker N. R. (Dordrecht: Springer;). 1996, 347–366. [CrossRef]

- Lawlor, D. W.; Cornic, G. Photosynthetic carbon assimilation and associated metabolism in relation to water deficits in higher plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2002, 25 275–294. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Xiong, L. General mechanisms of drought response and their application in drought resistance improvement in plants. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72 673–689. [CrossRef]

- Zahid, Z.; Khan, M.K.R.; Hameed, A.; Akhtar, M.; Ditta, A.; Hassan, H.M.; Farid, G. Dissection of drought tolerance in upland cotton through morpho-physiological and biochemical traits at seedling stage. Front Plant Sci. 2021 Mar 12; 12:627107. [CrossRef]

- Waterworth, W.M.; Bray, C.M.; West, C.E. The importance of safeguarding genome integrity in germination and seed longevity. J Exp Bot. 2015, 66(12):3549-58. [CrossRef]

- Wanda M. Waterworth. Clifford M. Bray. Christopher E. West. The importance of safeguarding genome integrity in germination and seed longevity. Journal of Experimental Botany. Volume 66. Issue 12. June 2015. Pages 3549–3558. [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Wahid, A.; Kobayashi, N. et al. Plant drought stress: Effects. mechanisms. and management. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 29. 185–212. [CrossRef]

- Larcher. W. Ecofisiologia Vegetal. 3. ed. São Carlos, SP: RiMa, 2006, 531.

- Parry, M.A.J.; Flexas, J.; Medrano, H. Prospects for crop production under drought: Research priorities and future directions. Ann. Appl. Biol.. 2005; 147(3):211-226.

- Babu, A.G.; Patil, B.C.; Koti, R.V. Identification of drought-tolerant cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) genotypes by biophysical and physiological traits. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 2019, 8(1). 1855-1560.

- Guo et al, 2018.

- Fukao and Xiong, 2013.

- Ashraf, M.Y.; Naqvi, M.H.; Khan, A.H. 1996. Evaluation of four screening techniques for drought tolerance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Acta Agron. Hung.. 1996, 44: 213-220.

- Dodd, G.L.; Donovan, L.A. Water potential and ionic effect on germination and seedling growth of two cold desert shrubs. Amer J Bot. 1999, 86:1146-1153. [CrossRef]

- Heikal, M.M.; Shaddad, M.A.; Ahmed, A.M. Effect of water stress and gibberellic acid on germination of flax. sesame and onion seed. Biol Plant, 1982, 24:124-129. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Ahmad, R.; Ashraf, M.Y.; Ashraf, M.; Waraich, E.A. Sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) response to drought stress at germination and seedling growth stages. Pak. J. Bot. 2009, 41(2): 647-654.

- Babu, A.G., Patil, B.C., Pawar, K.N. Evaluation of cotton genotypes for drought tolerance using PEG-6000 water stress by slanting glass plate technique. The Bioscan, 2014, 9(4): 1419-1424.

- Wendel, J.F.; Cronn, R.C. Polyploidy and the evolutionary history of cotton. Advances in Agronomy, 2003, 78: 139-186.

- Basal, H.; Smith, C.W.; Thaxton, P.S.; Hemphill, J.K. Seedling drought tolerance in upland cotton. Crop Science. 2005, 45(2): 766-771. [CrossRef]

- Medeiros Filho, S.; Silva, S.O.; Dutra, A.S.; Torres, S.B. 2006. Comparison of germination test methodologies of linted and delinted cotton seeds. Revista Caatinga, 2006, 19: 56-60.

- Lopes, K.P.; Bruno, R.L.A.; Costa, R.F.; Bruno, G.B.; Rocha, M.S. 2006. Effects of seed processing on physiological and sanitary qualities of seeds of herbaceous cotton. Revista Brasileira de Engenharia Agrícola e Ambiental, 10: 2006, 426-435. [CrossRef]

- McMichael, B.L.; Oosterhuis, D.M.; Zak, J.C. Stress response in cotton root systems. Stress Physiology in Cotton, 2011, 97.

- Abdual-Baki, A.; Andersen, J. Relationship between decarboxilation of glutamatic acid and vigour in soyabean seed. Crop Science. 1973, 13(2): 222-226. [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, J. R.; Messéan, A.; Ricci, P. Research and innovation priorities as defined by the Ecophyto plan to address current crop protection transformation challenges in France. Advances in Agronomy. 2019, 154. 81-152. [CrossRef]

- Côme, D. (1982). Germination, Mazliak, P. (Ed.) Physiologie Végétale II Croissance et Développement. Hermann. Paris, 1982, 129-225.

- Belcher, E.W.; Miller, L. Influence of substrate moisture level on the germination of sweetgum and sand pine seed. In Proceedings, 1975.

- Pieczynski, M.; Marczewski, W.; Hennig, J.; Dolata, J.; Bielewicz, D.; Piontek, P.; Wyrzykowska, A.; Krusiewicz, D.; Strzelczyk-Zyta, D.; Konopka-Postupolska, D.; Krzeslowska, M. Down-regulation of CBP 80 gene expression as a strategy to engineer a drought-tolerant potato. Plant biotechnology journal. 2013, 11(4):459-69. [CrossRef]

- JMP®. Version <x>. SAS Institute Inc. Cary. NC. 1989–2021.Where <17> is the version of JMP being cited.

- Minitab, L.L.C. 2021. Minitab. Retrieved from https://www.minitab.com.

- Steel, R.; Torrie, J., Dicky, D. Principles and Procedures of Statistics. Multiple Comparisons. McGraw Hill Book Co; 1997, 178–198.

- Sperdouli, I.; Moustakas, M. Differential response of photosystem II photochemistry in young and mature leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana to the onset of drought stress. Acta Physiol Plant, 2012, 34: 1267–1276. [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.; Park, K.; Jensen, K.H.; Kim, W.; Kim, H.Y. (2019). A design principle of root length distribution of plants. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 2019, 16(161), 20190556. [CrossRef]

- Postma, J.A.; Dathe, A.; Lynch, J.P. The optimal lateral root branching density for maize depends on nitrogen and phosphorus availability. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 590-602. [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.D.; McCannon, B.C.; Lynch, J.P. Optimization modeling of plant root architecture for water and phosphorus acquisition. J. Theor. Biol. 2004, 226, 331-340. [CrossRef]

- Couvreur, V.; Faget, M.; Lobet, G.; Javaux, M.; Chaumont, F.; Draye, X. 2018 Going with the flow: Multiscale insights into the composite nature of water transport in roots. Plant Physiol. 2018, 178, 1689-1703. [CrossRef]

- Fitter, A.H.; Stickland, T.R.; Harvey, M.L.; Wilson, G.W. 1991 Architectural analysis of plant root systems 1. Architectural correlates of exploitation efficiency. New Phytol. 1991, 118, 375-382. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, K.N.; Veena, V.B. Evaluation of Cotton Genotypes for Drought Tolerance using PEG-6000 Water Stress by Slanting Glass Plate Technique. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2020, 9(11): 3203-3212. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, C.J.; Cothren, J.T.; McInnes, K.J. Partitioning of biomass in water and nitrogen-stressed cotton during the pre-bloom stage. J. Plant Nutr. 1996, 19:595–617. [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Farooq, J.; Sakhawat, G.; Mahmood, A.; Sadiq, M.A.; Yaseen, M. Genotypic variability for root/shoot parameters under water stress in some advanced lines of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Genet Mol Res. 2013, 27;12(1):552-61. [CrossRef]

- Lakhanpaul, S.; Singh, V.; Kumar, S.; Bhardwaj, D.; Bhat, K.V. Sesame: Overcoming the abiotic stresses in the queen of oilseed crops. Improving crop resistance to abiotic stress, 2012, 1251-1283. [CrossRef]

- Dossa, K.; Yehouessi, L.W.; Likeng-Li-Ngue, B.C.; Diouf, D.; Liao, B.; Zhang, X.; Cisse, N.; Bell, J.M. Comprehensive screening of some west and central African sesame genotypes for drought resistance probing by geomorphological, physiological, biochemical, and seed quality traits. Agronomy, 2017a, 7: 83. [CrossRef]

- Dossa, K.; You, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Zhou, R.; Yu, J.; Wei, X.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, S.; Gao, Y.; Mmadi, M.A.; Zhang, X. Transcriptomic profiling of sesame during waterlogging and recovery. Scientific Data, 2019b, 6, 204. [CrossRef]

- Gloaguen, R.M.; Couch, A.; Rowland, D.L.; Bennett, J.; Hochmuth, G.; Langham, D.R.; Brym, Z.T. Root life history of non-dehiscent sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) cultivars and the relationship with canopy development. Field. Crop. Res. 2019, 241, 107560. [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Zhou, R.; Mmadi, M.A.; Li, D.; Qin, L.; Liu, A.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Wei, M.; Shi, L.; Wu, Z.; You, J.; Zhang, X.; Dossa, K. Root diversity in sesame (Sesamum indicum L.): Insights into the morphological, anatomical and gene expression profiles. Planta 2019, 250: 1461–1474. [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, M.S.; Talha, G.M.; Shahzad, R.; Jameel, S.; Aleem, M.; Iqbal, M.Z. Early response of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) genotype against drought stress. International Journal of Biosciences, 2019, 14 (2): 537-544. [CrossRef]

- Wang et al., 2015.

- Liu et al., 2018.

- Bin, C.; Anne, M.J.; Ramsey, S.L.; Ralph, E.D.; Lowell, P.B. (R)-nicotine biosynthesis, metabolism and translocation in tobacco as determined by nicotine demethylase mutants. Phytochemistry, 2013, 95:188–196. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Xie, Q.; Li, C.; Li, C.; Mei, L.; Yu, J.Z.; Chen, J.; Zhu, S. Cotton roots are the major source of gossypol biosynthesis and accumulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2020; 20:88. [CrossRef]

- Rauf, M.; Munir, M.; ul Hassan, M.; Ahmad, M.; Afzal, M. Performance of wheat genotypes under osmotic stress at germination and early seedling growth stage. African Journal of biotechnology, 2007, 6(8).

- Dossa, K.; Zhou, R.; Li, D.; Liu, A.; Qin, L.; Mmadi, M. A.; Su, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; You, J. A novel motif in the 5’-UTR of an orphan gene ‘Big Root Biomass’ modulates root biomass in sesame. Plant biotechnology journal, 2021, 19(5), 1065-1079. [CrossRef]

- Hamoud, H.; Soliman, Y.; Eldemery, S.; Abdellatif, K. Field performance and gene expression of drought stress tolerance in cotton (Gossypium barbadense L.). British Biotechnol J. 2016; 14:1–9. [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Norvell, E.; Wijewardana, C.; Wallace, T.; Chastain, D.; Reddy, K.R. Assessing morphological characteristics of elite cotton lines from different breeding programmes for low temperature and drought tolerance. J Agron Crop Sci. 2018; 204:467–76. [CrossRef]

- Wijewardana, C.; Henry, W.B.; Gao, W.; Reddy, K.R. Interactive efects on CO2, drought, and ultraviolet-B radiation on maize growth and development. J. Photochem Photobiol B Biol. 2016; 160:198–209. [CrossRef]

- Sekmen, A.H.; Ozgur, R.; Uzilday, B.; Turkan, I. Reactive oxygen species scavenging capacities of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) cultivars under combined drought and heat-induced oxidative stress. Environ Exp Bot. 2014; 99: 141–9. [CrossRef]

- Rehman et al. (2022).

- Megha, B.R.; Mummigatti, U.V.; Chimmad, V.P.; Aladakatti, Y.R. Evaluation of hirsutum cotton genotypes for water stress using PEG-6000 by slanting glass plate technique. Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci, 2017, 5, 740-750.

- Khan, M.F.; Shah, S.; Manzoor, T. Genotypic variability and trait association in cotton (Gossypıum hirsutum L.) seedlings under normal and drought conditions. Biological and Clinical Sciences Research Journal, 2023, (1): 266-266.

- Zafar, S.; Azhar, M. T. Assessment of variability for drought tolerance in Gossypium hirsutum L. at the seedling stage. Pakistan Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2015, 52(2).

- Raza, S.; Saleem, M. F.; Khan, I. H.; Jamil, M.; Ijaz, M.; Khan, M. A. Evaluating the drought stress tolerance efficiency of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) cultivars. Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences, 2012, 12(12), 41-46. [CrossRef]

- Shivakrishna, P.; Reddy, K. A.; Rao, D.M. The effect of PEG-6000 imposed drought stress on RNA content, relative water content (RWC), and chlorophyll content in peanut leaves and roots. Saudi Journal of biological sciences, 2018, 25(2), 285-289. [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, M.; Khan, M.; Arif, M. Effects of peg-induced water stress on growth and physiological responses of rice genotypes at the seedling stage. Pak. J. Bot, 2019, 51(6), 2013-2021. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Liu, W.J.; Zhang, N.H.; Wang, M.B.; Liang, H.G.; Lin, H. Effects of water stress on major photosystem II gene expression and protein metabolism in barley leaves Physiol. Plant., 2005, 125(4): 464-473. [CrossRef]

- Zgallaï, H.; Steppe, K.; Lemeur, R. Photosynthetic, physiological and biochemical responses of tomato plants to polyethylene glycol-induced water deficit. J. Integr. Plant Biol., 2005, 47(12): 1470-1478. [CrossRef]

- Hurd, E.A.; Spratt, E.D. Root Pattern in Crops Related to Water and Nutrition Uptake. Physiological Aspects of Dry Land Farming (Gupta US, ed.). Oxford & IBH Publ. Co., New Delhi, 1975.

- Bayoumi, T.Y.; Eid, M.H.; Metwali, E.M. Application of physiological and biochemical indices as a screening technique for drought tolerance in wheat genotypes. Afr. J. Biotech., 2008, 7(14).

- Quisenberry, J.E.; Jordan, W.R.; Roark, B.A.; Fryrear, D.W. Exotic cottons as genetic sources for drought resistance. Crop Sci. 1981, 21: 888-959. [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, D.H.; Rost, T.L. Primary and lateral root development of dark-and light-grown cotton seedlings under salinity stress. Botanica Acta, 1995, 108(5): 457-465. [CrossRef]

- Kalefetoğlu, T.; Turan, Ö.; Ekmekçi, Y. Effects of water deficit induced by PEG and NaCl on chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) cultivars and lines at early seedling stages. Gazi University Journal of Science, 2009, 22(1): 5-14.

- Kaya, M.D.; Okçu, G.; Atak, M.; Çıkılı, Y.; Kolsarıcı, Ö. Seed treatments to overcome salt and drought stress during germination in sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.). Eur. J. Agron., 2006, 24(4): 291-295. [CrossRef]

- Nepomuceno, A.L.; Oosterhuis, D.M.; Stewart,J. M. Physiological responses of cotton leaves and roots to water deficit induced by polyethylene glycol. Environmental and Experimental Botany, 1998, 40(1): 29-41. [CrossRef]

- Carpita, N.; Sabularse, D.; Montezinos, D.; Delmer, D.P. Determination of the pore size of cell walls of living plant cells. Science, 1979, 205(4411): 1144-1147. [CrossRef]

- Sy, A.; Grouzis, M.; Danthu, P. Seed germination of seven Sahelian legume species. Journal of Arid Environments, 2001, 49(4), 875-882. [CrossRef]

- Uprety, A.; Dahal, B. R.; Shrestha, B. (2020). Germination and seed vigour of indigenous bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) genotype in Nepal. SAARC J. Agric., 2020, 18(2): 67-75. [CrossRef]

| Root Lenght (RL) | |||||

| Genotype | 0 MPa | -4 MPa | -6 MPa | -8 Pa | -10 MPa |

| Aşkabat71 | 10.00a | 10. 00a | 17. 00a | 20.25a | 17.38b |

| May 505 | 13.75a | 17.25a | 16. 00a | 16.75a | 15.25b |

| SC 32 | 15.75a | 15.25a | 21.50a | 21.75a | 23.50a |

| Sc 38 | 16. 00a | 14.50a | 24.50a | 17.50a | 22. 00a |

| Mean | 13.87 a | 14.25a | 19.75a | 19.06a | 19.53ab |

| Root Weight (RW) | |||||

| Genotype | 0 MPa | -4 MPa | -6 MPa | -8 MPa | -10 MPa |

| Aşkabat71 | 0.201b | 0.190a | 0.310ab | 0.325a | 0.219b |

| May 505 | 0.223ab | 0.290a | 0.270b | 0.300a | 0.254b |

| SC 32 | 0.374a | 0.340a | 0.370a | 0.390a | 0.374a |

| Sc 38 | 0.267ab | 0.230a | 0.420a | 0.370a | 0.337ab |

| Mean | 0.266ab | 0.262c | 0.342ab | 0.346a | 0.296a |

| Number of Lateral Roots (NLRs) | |||||

| Genotip | 0 MPa | -4 MPa | -6 MPa | -8 MPa | -10 MPa |

| Aşkabat71 | 15.25b | 18.50a | 24.25ab | 36.75a | 34.00ab |

| May 505 | 11.75b | 16.50a | 17.25b | 15.5b | 19.25b |

| SC 32 | 24.00ab | 28.25a | 30.75ab | 43.25a | 39.00a |

| Sc 38 | 34.25a | 29.50a | 41.25a | 33.25a | 43.00a |

| Mean | 21.31ab | 23.18a | 28.38ab | 32.19a | 33.812ab |

| Shoot Lenght (SL) | |||||

| Genotip | 0 MPa | -4 MPa | -6 MPa | -8 MPa | -10 MPa |

| Aşkabat71 | 15.98a | 15.87a | 19.82a | 20.22a | 15.95a |

| May 505 | 09.00c | 11.12b | 09.90c | 12.80c | 12.40a |

| SC 32 | 11.75bc | 9.87b | 12.52bc | 11.92c | 13.00a |

| Sc 38 | 13.20ab | 13.57ab | 15.05b | 16.82b | 13.62a |

| Mean | 12.48bc | 12.607ab | 14.322bc | 15.44b | 13.742a |

| Shoot Fresh Weight (SFW) | |||||

| Genotip | 0 MPa | -4 MPa | -6 MPa | -8 MPa | -10 MPa |

| Aşkabat71 | 1.187a | 1.740a | 1.670a | 1.051a | 1.117a |

| May 505 | 0.687b | 1.107b | 0.940b | 1.142a | 1.230a |

| SC 32 | 1.530a | 1.150b | 1.290ab | 1.560a | 1.717a |

| Sc 38 | 1.437a | 1.307ab | 1.407ab | 1.790a | 1.380a |

| Mean | 1.210ab | 1.326ab | 1.327ab | 1.386a | 1.361a |

| Root Dry Weight (RDW) | |||||

| Genotip | 0 MPa | -4 MPa | -6 MPa | -8 MPa | -10 MPa |

| Aşkabat71 | 0,0373a | 0,0413a | 0,083a | 0,0919a | 0,1731a |

| May 505 | 0,0364a | 0,0579a | 0,0534b | 0,0656b | 0,1192b |

| SC 32 | 0,1061b | 0,0808b | 0,1181c | 0,294d | 0,1046b |

| Sc 38 | 0,0753c | 0,0634c | 0,1186c | 0,2323d | 0,0862c |

| Mean | 0,063775c | 0,06085c | 0,0932a | 0,17095d | 0,1207b |

| Shoot Dry Weight (SDW) | |||||

| Genotip | 0 MPa | -4 MPa | -6 MPa | -8 MPa | -10 MPa |

| Aşkabat71 | 0.116b | 0.174a | 0.155a | 0.150b | 0.108a |

| May 505 | 0.138ab | 0.108a | 0.128a | 0.150b | 0.194a |

| SC 32 | 0.070c | 0.115a | 0.107a | 0.119b | 0.174a |

| Sc 38 | 0.166a | 0.155a | 0.354a | 0.263a | 0.168a |

| Mean | 0.122ab | 0.138a | 0.186a | 0.171ab | 0.161a |

| Relative Water Content (RWC) | |||||

| Genotip | 0 MPa | -4 MPa | -6 MPa | -8 MPa | -10 MPa |

| Aşkabat71 | 81.50b | 83.75a | 85.25a | 63,00a | 82.50a |

| May 505 | 79.75b | 77.75a | 83.50a | 79,00a | 71.75b |

| SC 32 | 92.25a | 84.25a | 83.25a | 77.75a | 73.25ab |

| Sc 38 | 82.00ab | 82.50a | 82.50a | 75.25a | 79.5ab |

| Mean | 83.875ab | 82.06a | 83.63a | 73.75a | 76.81ab |

| Germination Percentage (GP) | |||||

| Genotip | 0 MPa | -0.4 MPa | -0.6 MPa | -0.8 MPa | -1 MPa |

| Aşkabat71 | 92.50a | 92.5a | 75,00a | 62.50a | 47.50a |

| May 505 | 97.50a | 87.5ab | 75,00a | 60,00a | 45,00a |

| SC 32 | 87.50a | 77.5ab | 60,00a | 55,00a | 42.50a |

| Sc 38 | 80,00a | 70,00b | 65,00a | 52.50a | 47.50a |

| Mean | 71.37a | 81.88ab | 68.75a | 57.50a | 45.625a |

| Vigor Seed Index (VSI) | |||||

| Genotip | 0 MPa | -4 MPa | -6 MPa | -8 MPa | -10 MPa |

| Aşkabat71 | 2379a | 2473a | 3381a | 3740a | 3062a |

| May 505 | 2225a | 2780a | 2521a | 2905b | 2699a |

| SC 32 | 2387a | 2134a | 2951a | 2960ab | 3197a |

| Sc 38 | 2245a | 2284a | 3099a | 2725b | 2905a |

| Mean | 2309a | 2417a | 2988a | 3082bc | 2965a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).