Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Neospora Caninum and Neosporosis

2. Diagnosis of N. caninum Infection

3. Distribution and Transmission of Neosporosis in Farm Animals

4. The Farm Animal-Wildlife Animal Interface and Control

5. Molecular and Cellular Biology of N. caninum

6. Immunological Control of Infection and Vaccination

7. Recent Advances in Therapeutic Strategies

8. N. caninum as a Therapeutic Agent for Cancer Treatments

9. Potential Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dubey, J.P.; Hattel, A.L.; Lindsay, D.S.; Topper, M.J. Neonatal Neospora Caninum Infection in Dogs: Isolation of the Causative Agent and Experimental Transmission. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1988, 193, 1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gondim, L.F.P.; McAllister, M.M.; Pitt, W.C.; Zemlicka, D.E. Coyotes (Canis Latrans) Are Definitive Hosts of Neospora Caninum. Int J Parasitol 2004, 34, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAllister, M.M.; Dubey, J.P.; Lindsay, D.S.; Jolley, W.R.; Wills, R.A.; McGuire, A.M. Dogs Are Definitive Hosts of Neospora Caninum. Int J Parasitol 1998, 28, 1473–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

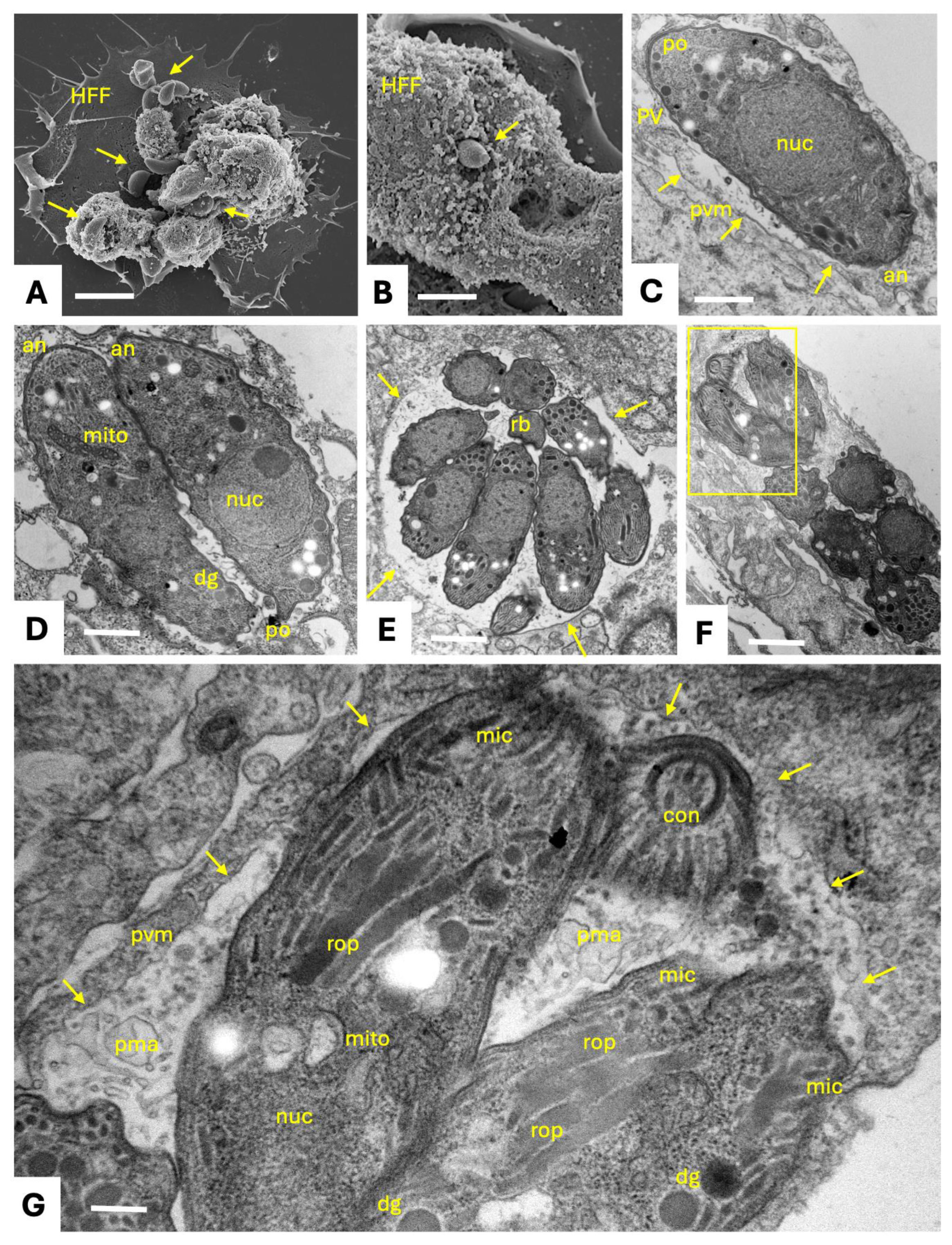

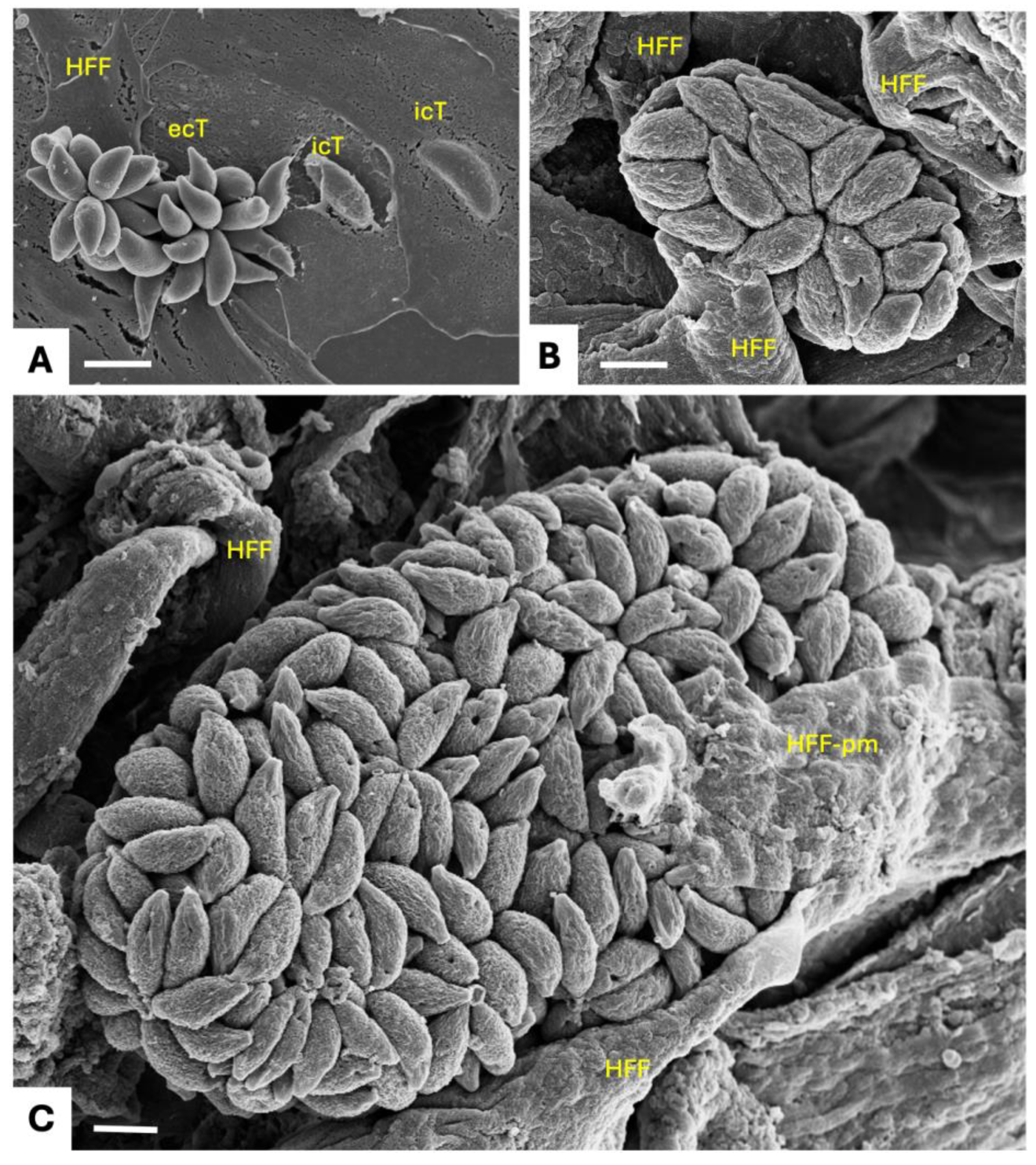

- Hemphill, A. The Host-Parasite Relationship in Neosporosis. Adv Parasitol 1999, 43, 47–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, A.; Vonlaufen, N.; Naguleswaran, A. Cellular and Immunological Basis of the Host-Parasite Relationship during Infection with Neospora Caninum. Parasitology 2006, 133, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P.; Hemphill, A.; Calero-Bernal, R.; Schares, G. Neosporosis in Animals, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton; Taylor & Francis, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-15256-1. [Google Scholar]

- Imhof, D.; Hänggeli, K.P.A.; De Sousa, M.C.F.; Vigneswaran, A.; Hofmann, L.; Amdouni, Y.; Boubaker, G.; Müller, J.; Hemphill, A. Working towards the Development of Vaccines and Chemotherapeutics against Neosporosis-With All of Its Ups and Downs-Looking Ahead. Adv Parasitol 2024, 124, 91–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-Fernández, I.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; Jiménez-Pelayo, L.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Horcajo, P. Modeling the Ruminant Placenta-Pathogen Interactions in Apicomplexan Parasites: Current and Future Perspectives. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 7, 634458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collantes-Fernandez, E.; Arrighi, R.B.G.; Alvarez-García, G.; Weidner, J.M.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Boothroyd, J.C.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Barragan, A. Infected Dendritic Cells Facilitate Systemic Dissemination and Transplacental Passage of the Obligate Intracellular Parasite Neospora Caninum in Mice. PLoS One 2012, 7, e32123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Lütkefels, E.; Heckeroth, A.R.; Schares, G. Immunohistochemical and Ultrastructural Evidence for Neospora Caninum Tissue Cysts in Skeletal Muscles of Naturally Infected Dogs and Cattle. Int J Parasitol 2001, 31, 1144–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharekhani, J.; Yakhchali, M. Vertical Transmission of Neospora Caninum in Iranian Dairy Cattle. Ann Parasitol 2020, 66, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aguado-Martínez, A.; Basto, A.P.; Leitão, A.; Hemphill, A. Neospora Caninum in Non-Pregnant and Pregnant Mouse Models: Cross-Talk between Infection and Immunity. Int J Parasitol 2017, 47, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L.M.; Ma, Y.F.; Halonen, S.; McAllister, M.M.; Zhang, Y.W. The in Vitro Development of Neospora Caninum Bradyzoites. Int J Parasitol 1999, 29, 1713–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vonlaufen, N.; Müller, N.; Keller, N.; Naguleswaran, A.; Bohne, W.; McAllister, M.M.; Björkman, C.; Müller, E.; Caldelari, R.; Hemphill, A. Exogenous Nitric Oxide Triggers Neospora Caninum Tachyzoite-to-Bradyzoite Stage Conversion in Murine Epidermal Keratinocyte Cell Cultures. Int J Parasitol 2002, 32, 1253–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonlaufen, N.; Guetg, N.; Naguleswaran, A.; Müller, N.; Björkman, C.; Schares, G.; von Blumroeder, D.; Ellis, J.; Hemphill, A. In Vitro Induction of Neospora Caninum Bradyzoites in Vero Cells Reveals Differential Antigen Expression, Localization, and Host-Cell Recognition of Tachyzoites and Bradyzoites. Infect Immun 2004, 72, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokol-Borrelli, S.L.; Coombs, R.S.; Boyle, J.P. A Comparison of Stage Conversion in the Coccidian Apicomplexans Toxoplasma Gondii, Hammondia Hammondi, and Neospora Caninum. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 608283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horcajo, P.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Aguado-Martínez, A.; Hemphill, A.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Vaccines for Bovine Neosporosis: Current Status and Key Aspects for Development. Parasite Immunol 2016, 38, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, C.; Seferidis, N.; Zilli, J.; Roberts, T.; Harcourt-Brown, T. Insights into the Clinical Presentation, Diagnostics and Outcome in Dogs Presenting with Neurological Signs Secondary to Infection with Neospora Caninum: 41 Cases (2014-2023). J Small Anim Pract 2024, 65, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alf, V.; Tirrito, F.; Fischer, A.; Cappello, R.; Kiviranta, A.-M.; Steinberg, T.A.; Poli, F.; Stotz, F.; Del Vecchio, O.V.; Dörfelt, S.; et al. A Multimodal Approach to Diagnosis of Neuromuscular Neosporosis in Dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2024, 38, 2561–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, G.; Rigamonti, G.; Brustenga, L.; Calgaro, V.; Angeli, G.; Moretta, I.; Diaferia, M.; Veronesi, F. Exploring Similarities and Differences between Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum Infections in Dogs. Vet Res Commun 2024, 48, 3563–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodswen, S.J.; Kennedy, P.J.; Ellis, J.T. A Guide to Current Methodology and Usage of Reverse Vaccinology towards in Silico Vaccine Discovery. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2023, 47, fuad004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoust, B.; Laidoudi, Y. Wildlife, Reservoir of Zoonotic Agents: Moving beyond Denial and Fear. Pathogens 2023, 12, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P.; Lindsay, D.S. A Review of Neospora Caninum and Neosporosis. Vet Parasitol 1996, 67, 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.-S.; Yang, C.-Y.; Ayanniyi, O.-O.; Chen, Y.-Q.; Lu, Z.-X.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Liu, L.-Y.; Hong, Y.-H.; Cheng, R.-R.; Zhang, X.; et al. Development and Application of an Indirect ELISA to Detect Antibodies to Neospora Caninum in Cattle Based on a Chimeric Protein rSRS2-SAG1-GRA7. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 1028677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udonsom, R.; Adisakwattana, P.; Popruk, S.; Reamtong, O.; Jirapattharasate, C.; Thiangtrongjit, T.; Rerkyusuke, S.; Chanlun, A.; Hasan, T.; Kotepui, M.; et al. Evaluation of Immunodiagnostic Performances of Neospora Caninum Peroxiredoxin 2 (NcPrx2), Microneme 4 (NcMIC4), and Surface Antigen 1 (NcSAG1) Recombinant Proteins for Bovine Neosporosis. Animals 2024, 14, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereig, R.M.; Abdelbaky, H.H.; Nishikawa, Y. Comparative Evaluation of Four Potent Neospora Caninum Diagnostic Antigens Using Immunochromatographic Assay for Detection of Specific Antibody in Cattle. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereig, R.M.; Nishikawa, Y. From Signaling Pathways to Distinct Immune Responses: Key Factors for Establishing or Combating Neospora Caninum Infection in Different Susceptible Hosts. Pathogens 2020, 9, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, T.; Macrae, A.I.; Cantón, G.J.; Cantile, C.; Martineau, H.M.; Palarea-Albaladejo, J.; Cahalan, S.; Underwood, C.; Katzer, F.; Chianini, F. Evaluation of Species-Specific Polyclonal Antibodies to Detect and Differentiate between Neospora Caninum and Toxoplasma Gondii. J Vet Diagn Invest 2024, 36, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellarupe, A.; Moré, G.; Unzaga, J.M.; Pardini, L.; Venturini, M.C. Study of Specific Immunodominant Antigens in Different Stages of Neospora Caninum, Toxoplasma Gondii, Sarcocystis Spp. and Hammondia Spp. Exp Parasitol 2024, 262, 108772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandelj, P.; Kušar, D.; Šimenc, L.; Jamnikar-Ciglenečki, U.; Vengušt, G.; Vengušt, D.Ž. First Molecular Detection of Neospora Caninum in Feces of Grey Wolf (Canis Lupus) and Golden Jackal (Canis Aureus) Populations in Slovenia. Animals (Basel) 2023, 13, 3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouvias, I.; Lysitsas, M.; Batsidis, A.; Malefaki, S.; Bitchava, D.; Tsara, A.; Nickovic, E.; Bouzalas, I.; Malissiova, E.; Guatteo, R.; et al. Molecular Investigation of Small Ruminant Abortions Using a 10-Plex HRM-qPCR Technique: A Novel Approach in Routine Diagnostics. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.; Šlapeta, J. Analytical Sensitivity of a Multiplex Quantitative PCR for Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum. Parasitol Res 2023, 122, 1043–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabet, C.; Brossas, J.-Y.; Poignon, C.; Bouzidi, A.; Paris, L.; Touafek, F.; Varlet-Marie, E.; Sterkers, Y.; Passebosc-Faure, K.; Dardé, M.-L.; et al. Assessment of Droplet Digital PCR for the Detection and Absolute Quantification of Toxoplasma Gondii: A Comparative Retrospective Study. J Mol Diagn 2023, 25, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, A.E.; Muñoz, M.; Cortés-Vecino, J.A.; Barato, P.; Patarroyo, M.A. A Novel Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification-Based Test for Detecting Neospora Caninum DNA. Parasit Vectors 2017, 10, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erber, A.C.; Sandler, P.J.; De Avelar, D.M.; Swoboda, I.; Cota, G.; Walochnik, J. Diagnosis of Visceral and Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Using Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) Protocols: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Parasites Vectors 2022, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Hu, K.; Chen, M.; Hong, H.; Jiang, X.; Huang, R.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Yu, X.; Liu, Q.; et al. A Colorimetric Assay for Neospora Caninum Utilizing the Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Technique. Res Vet Sci 2024, 179, 105395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Cao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Cao, S.; Zhang, N.; et al. Establishment of an Ultrasensitive and Visual Detection Platform for Neospora Caninum Based-on the RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a System. Talanta 2024, 269, 125413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, N.; Zimmermann, V.; Hentrich, B.; Gottstein, B. Diagnosis of Neospora Caninum and Toxoplasma Gondii Infection by PCR and DNA Hybridization Immunoassay. J Clin Microbiol 1996, 34, 2850–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Silveira, C.; Armendano, J.I.; Moore, D.P.; Cantón, G.J.; Macías-Rioseco, M.; Riet-Correa, F.; Giannitti, F. A comparative study of commercial ELISAs for antibody detection in the diagnostic investigation of Neospora caninum-associated abortion in dairy cattle herds in Uruguay. Rev Argent Microbiol 2020, 52, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gliga, D.S.; Basso, W.; Ardüser, F.; Moore-Jones, G.; Schares, G.; Zanolari, P.; Frey, C.F. Switzerland-Wide Neospora Caninum Seroprevalence in Female Cattle and Identification of Risk Factors for Infection. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 1059697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waap, H.; Bärwald, A.; Nunes, T.; Schares, G. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors for Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum in Cattle in Portugal. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12, 2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, L.; Allievi, C.; Di Cerbo, A.R.; Zanzani, S.A.; Sommariva, F.; Zanini, L.; Mortarino, M.; Manfredi, M.T. Neospora Caninum Antibodies in Bulk Tank Milk from Dairy Cattle Herds in Italy in Relation to Reproductive and Productive Parameters and Spatial Analysis. Acta Trop 2024, 254, 107194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, W.; de Jong, E.; McCubbin, K.D.; Biesheuvel, M.M.; van der Meer, F.J.U.M.; De Buck, J.; Lhermie, G.; Hall, D.C.; Kalbfleisch, K.N.; Kastelic, J.P.; et al. Herd-Level Prevalence of Bovine Leukemia Virus, Salmonella Dublin, and Neospora Caninum in Alberta, Canada, Dairy Herds Using ELISA on Bulk Tank Milk Samples. J Dairy Sci 2024, 107, 8313–8328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idarraga-Bedoya, S.E.; Álvarez-Chica, J.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Moore, D.P.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J. Seroprevalence of Neospora Caninum Infection in Cattle from Pereira, Colombia ⋆. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports 2020, 22, 100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.-Y.; An, Q.; Xue, N.-Y.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wang, C.-R. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Neospora Caninum Infection in Cattle in China from 2011 to 2020: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prev Vet Med 2022, 203, 105620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Zhu, Z.-F.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Neospora Caninum Infection among Cattle in Mainland China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Prev Vet Med 2022, 201, 105593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, Z. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum in Dairy Cows in Hebei Province, China. Anim Biotechnol 2021, 32, 451–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, X.-L.; Yang, W.-H.; Zheng, H.-L.; Cao, M.-L.; Xiong, J.; Chen, W.-C.; Zhou, Y.-J.; Li, F.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Liu, G.-H. Seroprevalence and Molecular Detection of Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum in Beef Cattle and Goats in Hunan Province, China. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebbar, B.K.; Mitra, P.; Khan, W.; Chaudhari, S.; Shinde, S.; Deshmukh, A.S. Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum Infections in Cattle in Central India. Parasitol Int 2022, 87, 102514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahiduzzaman, M.; Biswas, P.; Kabir, A.; Beni Amin, A.R.M.; Parijat, S.S.; Ahmed, N.; Hossain, M.Z.; Wakid, M.H. First Report of Neospora Caninum from Aborted Fetuses of Cattle, Sheep, and Goats in Bangladesh. J Adv Vet Anim Res 2024, 11, 618–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selim, A.; Alshammari, A.; Gattan, H.S.; Marzok, M.; Salem, M.; Al-Jabr, O.A. Neospora Caninum Infection in Dairy Cattle in Egypt: A Serosurvey and Associated Risk Factors. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 15489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwally, S.; Hamada, R.; Sobhy, K.; Frey, C.F.; Fereig, R.M. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors Analysis of Neospora Caninum and Toxoplasma Gondii in Cattle of Beheira, Egypt. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10, 1122092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagwireyi, W.M.; Thompson, P.N.; Garcia, G.A.; Morar-Leather, D.; Neves, L. Seroprevalence and Associated Risk Factors for Neospora Caninum Infection in Dairy Cattle in South Africa. Parasitol Res 2024, 123, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakimori, M.T.A.; Osman, A.M.; Silva, A.C.S.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Shair, M.A.; Cavallieri, A.C.; Barros, L.D.; Garcia, J.L.; Vieira, T.S.W.J.; Hassan-Kadle, A.A.; et al. Serological and Molecular Detection of Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum in Ruminants from Somalia. Parasitol Res 2024, 123, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira Junior, I.M.; Mesquita, L.E.D.S.; Miranda, D.N.P.; Gomes, T.A.; Vasconcelos, B.K.S.; Penha, L.C.; Silveira, L.C.S.; Redondo, A.R.R.; Costa, R.C.; Bruhn, F.R.P.; et al. Endogenous Transplacental Transmission of Neospora Caninum in Successive Generations of Congenitally Infected Goats. Veterinary Parasitology 2020, 284, 109191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campero, L.M.; Basso, W.; Moré, G.; Fiorani, F.; Hecker, Y.P.; Echaide, I.; Cantón, G.J.; Cirone, K.M.; Campero, C.M.; Venturini, M.C.; et al. Neosporosis in Argentina: Past, Present and Future Perspectives. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports 2023, 41, 100882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, L.S.; Withoeft, J.A.; Bilicki, J.V.; Melo, I.C.; Snak, A.; das Neves, G.B.; Miletti, L.C.; de Moura, A.B.; Casagrande, R.A. Neospora Caninum-Associated Abortions in Cattle from Southern Brazil: Anatomopathological and Molecular Characterization. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports 2022, 36, 100802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remor-Sebolt, A.P.; de Lima, F.R.; Américo, L.; Padilha, M.A.C.; Chryssafidis, A.L.; de Moura, A.B. Occurrence of Antibodies and Epidemiological Significance of Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum Infections in Canine Populations of Laguna, State of Santa Catarina. Vet Res Commun 2024, 48, 3349–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Pazmiño, A.S.; Brito, C.M.; Salas-Rueda, M.; Orlando, S.A.; Garcia-Bereguiain, M.A. A First Insight into Seropositivity of Neospora Caninum and Associated Risk Factors in Free-Roaming Dogs from Ecuador. Acta Trop 2024, 256, 107245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turlewicz-Podbielska, H.; Ruszkowski, J.J.; Wojciechowski, J.; Pomorska-Mól, M. Seroprevalence of Neospora Caninum in Pet Cats, Dogs and Rabbits from Urban Areas of Poland. BMC Vet Res 2024, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagomarsino, H.; Scioli, A.; Rodríguez, A.; Armendano, J.; Fiorani, F.; Bence, Á.; García, J.; Hecker, Y.; Gual, I.; Cantón, G.; et al. Controlling Endemic Neospora Caninum-Related Abortions in a Dairy Herd From Argentina. Front Vet Sci 2019, 6, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, M.H.M.; Sandoval, E.D.P.; Duarte, J.M.B. Assessment of Transplacental Transmission of Neospora Caninum and Toxoplasma Gondii in Neotropical Deer: An Estimative Based on Serology. Vet Parasitol 2022, 303, 109677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanet, S.; Poncina, M.; Ferroglio, E. Congenital Transmission of Neospora Caninum in Wild Ungulates and Foxes. Front Vet Sci 2023, 10, 1109986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, L.; Withoeft, J.A.; Costa, L. da S.; Ribeiro, L.R.; Melo, I.C.; Alves, R.S.; Baumbach, L.F.; Pinto, M.G.L.; Snak, A.; Miletti, L.C.; et al. Causes of Fetal Death in the Flemish Cattle Herd in Brazil. Vet World 2023, 16, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montiel-González, G.; Franco-Robles, E.; García-Munguía, C.A.; Valencia-Posadas, M.; Martínez-Jaime, O.A.; López-Briones, S.; Gutiérrez-Chávez, A.J. Co-Infection by Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum in Goats Reared in Extensive System of Mexico. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2024, 24, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzavi, Y.; Salimi, Y.; Ahmadi, M.; Adimi, P.; Falahi, S.; Bozorgomid, A. Global Prevalence of Neospora Caninum in Rodents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vet Med Sci 2023, 9, 2192–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichel, M.P.; Alejandra Ayanegui-Alcérreca, M.; Gondim, L.F.P.; Ellis, J.T. What Is the Global Economic Impact of Neospora Caninum in Cattle - the Billion Dollar Question. Int J Parasitol 2013, 43, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, C.M.; Soares, I.R.; Mendes, R.G.; De Santis Bastos, P.A.; Katagiri, S.; Zavilenski, R.B.; De Abreu, H.F.P.; Afreixo, V. Meta-Analysis of the Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Bovine Neosporosis. Trop Anim Health Prod 2019, 51, 1783–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, P.A.; Eşki, F.; Ütük, A.E. Estimating the Total Economic Costs of Neospora Caninum Infections in Dairy Cows in Turkey. Trop Anim Health Prod 2020, 52, 3251–3258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, M.J.; Huaman, J.L.; Pacioni, C.; Stephens, D.; Hitchen, Y.; Carvalho, T.G. Active Shedding of Neospora Caninum Detected in Australian Wild Canids in a Nonexperimental Context. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022, 69, 1862–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaman, J.L.; Pacioni, C.; Doyle, M.; Forsyth, D.M.; Helbig, K.J.; Carvalho, T.G. Evidence of Australian Wild Deer Exposure to N. Caninum Infection and Potential Implications for the Maintenance of N. Caninum Sylvatic Cycle. BMC Vet Res 2023, 19, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semango, G.P.; Buza, J. Review of the Current Status on Ruminant Abortigenic Pathogen Surveillance in Africa and Asia. Veterinary Sciences 2024, 11, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Escobar, M.; Millán, J.; Chirife, A.D.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Calero-Bernal, R. Molecular Survey for Cyst-Forming Coccidia (Toxoplasma Gondii, Neospora Caninum, Sarcocystis Spp.) in Mediterranean Periurban Micromammals. Parasitol Res 2020, 119, 2679–2686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Torres, K.I.; Pomeroy, L.W.; Moritz, M.; Saville, W.; Wolfe, B.; Garabed, R. Host Species Heterogeneity in the Epidemiology of Nesopora Caninum. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydett, K.M.; Peper, S.T.; Reinoso Webb, C.; Tiffin, H.S.; Wilson-Fallon, A.N.; Jones-Hall, Y.L.; Webb, S.L.; Presley, S.M. Prevalence of Neospora Caninum Exposure in Wild Pigs (Sus Scrofa) from Oklahoma with Implications of Testing Method on Detection. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenny, L.; O’Handley, R.; Kovaliski, J.; Mutze, G.; Peacock, D.; Lanyon, S. Evidence of Infection with Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum in South Australia: Using Wild Rabbits as a Sentinel Species. Aust Vet J 2020, 98, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Azevedo Filho, P.C.G.; Ribeiro-Andrade, M.; Santos, J.F.D.; Reis, A.C.D.; Pinheiro Júnior, J.W.; Valença, S.R.F. de A.; Samico-Fernandes, E.F.T.; Mota, R.A. Neospora Caninum Infection in Cattle in the State of Amazonas, Brazil: Seroprevalence, Spatial Distribution and Risk Factors. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 2021, 30, e020820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, L.; Maksimov, P.; Luttermann, C.; Tuschy, M.; Gazzonis, A.L.; Zanzani, S.A.; Mortarino, M.; Conraths, F.J.; Manfredi, M.T.; Schares, G. Spatial Distance between Sites of Sampling Associated with Genetic Variation among Neospora Caninum in Aborted Bovine Foetuses from Northern Italy. Parasit Vectors 2021, 14, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinon, A.; Fiorani, F.; Campero, L.M.; Moore, D.P.; Corva, P.M. The Role of Genetic Variability of the Host on the Resistance to Neospora Caninum Infection in Cattle. Anim Genet 2024, 55, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo, G.F.; Couto, S.R.B.; Guerson, Y.B.; Ferreira, J.E.; Teixeira, E.F.; Silva, A.F.; Palhano, H.B.; Mello, M.R.B. Neospora Caninum Is Not Transmissible via Embryo Transfer, but Affects the Quality of Embryos in Dairy Cows. Vet Parasitol 2024, 331, 110287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivatto, R.A.; Reiter, J.C.; Rodrigues, R.B.; Miletti, L.C.; Palácios, R.; Snak, A.; Chryssafidis, A.L.; Moura, A.B. de Experimental Infection with Neospora Caninum in Texel Ewes at Different Stages of Gestation. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Reports 2023, 37, 100817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, A.J.; Vermont, S.J.; Cotton, J.A.; Harris, D.; Hill-Cawthorne, G.A.; Könen-Waisman, S.; Latham, S.M.; Mourier, T.; Norton, R.; Quail, M.A.; et al. Comparative Genomics of the Apicomplexan Parasites Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum: Coccidia Differing in Host Range and Transmission Strategy. PLoS Pathog 2012, 8, e1002567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jia, L.; Shao, Q.; Lu, H.; Zhao, J.; Yin, J. MicroRNA Profiling of Neospora Caninum Tachyzoites (NC-1) Using a High-Throughput Approach. Parasitol Res 2021, 120, 2165–2174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.; Hasan, M.; Akter, S.; Roy, S.; Sharma, B.; Chowdhury, M.S.R.; Ahsan, M.I.; Akhand, R.N.; Uddin, M.B.; Ahmed, S.S.U. In Silico Investigation of Conserved miRNAs and Their Targets From the Expressed Sequence Tags in Neospora Caninum Genome. Bioinform Biol Insights 2021, 15, 11779322211046729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-M.; Zhao, S.-S.; Tao, D.-L.; Li, J.-Y.; Yang, X.; Fan, Y.-Y.; Song, J.-K.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, G.-H. Temporal Transcriptomic Changes in microRNAs Involved in the Host Immune Response and Metabolism during Neospora Caninum Infection. Parasit Vectors 2023, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz-Solís, D.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Lourido, S.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Saeij, J.P.J. Toxoplasma CRISPR/Cas9 Constructs Are Functional for Gene Disruption in Neospora Caninum. Int J Parasitol 2018, 48, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-San Román, L.; Hänggeli, K.P.A.; Hemphill, A.; Horcajo, P.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Boubaker, G. TaqMan-Quantitative PCR Assays Applied in Neospora Caninum Knock-Outs Generated through CRISPR-Cas9 Allow to Determine the Copy Numbers of Integrated Dihydrofolate Reductase-Thymidylate Synthase Drug Selectable Markers. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, 14, 1419209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mineo, T.W.P.; Chern, J.H.; Thind, A.C.; Mota, C.M.; Nadipuram, S.M.; Torres, J.A.; Bradley, P.J. Efficient Gene Knockout and Knockdown Systems in Neospora Caninum Enable Rapid Discovery and Functional Assessment of Novel Proteins. mSphere 2022, 7, e0089621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, Y.; Shimoda, N.; Fereig, R.M.; Moritaka, T.; Umeda, K.; Nishimura, M.; Ihara, F.; Kobayashi, K.; Himori, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; et al. Neospora Caninum Dense Granule Protein 7 Regulates the Pathogenesis of Neosporosis by Modulating Host Immune Response. Appl Environ Microbiol 2018, 84, e01350-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-San Román, L.; Amieva, R.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; García-Sánchez, M.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; Pastor-Fernández, I.; Saeij, J.P.J.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Horcajo, P. NcGRA7 and NcROP40 Play a Role in the Virulence of Neospora Caninum in a Pregnant Mouse Model. Pathogens 2022, 11, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Wang, X.; Song, X.; Ma, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J. Function of Neospora Caninum Dense Granule Protein 7 in Innate Immunity in Mice. Parasitol Res 2021, 120, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, J.; Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Q. NcGRA17 Is an Important Regulator of Parasitophorous Vacuole Morphology and Pathogenicity of Neospora Caninum. Veterinary Parasitology 2018, 264, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, N.; Dong, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Gong, P.; Zhang, X. Effects of Dense Granular Protein 6 (GRA6) Disruption on Neospora Caninum Virulence. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 562730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhao, P.; Li, J.; Cao, L.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Zhang, X.; Gong, P. Disruption of Dense Granular Protein 2 (GRA2) Decreases the Virulence of Neospora Caninum. Front Vet Sci 2021, 8, 634612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ayanniyi, O.O.; Luo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wang, C.; Yang, C. Functional Characterization of Three Novel Dense Granule Proteins in Neospora Caninum Using the CRISPR-Cas9 System. Acta Trop 2024, 256, 107250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amieva, R.; Coronado, M.; Powell, J.; Arranz-Solís, D.; Hassan, M.A.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Horcajo, P. NcROP2 Deletion Reduces Neospora Caninum Virulence by Altering Parasite Stage Differentiation and Hijacking Host Immune Response. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1617570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, H.; Lu, X.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X.; Ying, Z.; Ma, L. Identification and Function Characterization of NcAP2XII-4 in Neospora Caninum. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelbaky, H.H.; Rahman, M.M.; Shimoda, N.; Chen, Y.; Hasan, T.; Ushio, N.; Nishikawa, Y. Neospora Caninum Surface Antigen 1 Is a Major Determinant of the Pathogenesis of Neosporosis in Nonpregnant and Pregnant Mice. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1334447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q. NcPuf1 Is a Key Virulence Factor in Neospora Caninum. Pathogens 2020, 9, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Chen, M.; Chang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Gong, P.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; et al. Immunization with the NcMYR1 Gene Knockout Strain Effectively Protected C57BL/6 Mice and Their Pups against the Neospora Caninum Challenge. Virulence 2024, 15, 2427844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasina, R.; González, F.C.; Echeverría, S.; Cabrera, A.; Robello, C. Insights into the Cell Division of Neospora Caninum. Microorganisms 2023, 12, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Flores, C.J.; Tibabuzo Perdomo, A.M.; Gallego-López, G.M.; Knoll, L.J. Transcending Dimensions in Apicomplexan Research: From Two-Dimensional to Three-Dimensional In Vitro Cultures. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2022, 86, e0002522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feix, A.S.; Cruz-Bustos, T.; Ruttkowski, B.; Joachim, A. In Vitro Cultivation Methods for Coccidian Parasite Research. Int J Parasitol 2023, 53, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado-Martínez, A.; Basto, A.P.; Tanaka, S.; Ryser, L.T.; Nunes, T.P.; Ortega-Mora, L.-M.; Arranz-Solís, D.; Leitão, A.; Hemphill, A. Immunization with a Cocktail of Antigens Fused with OprI Reduces Neospora Caninum Vertical Transmission and Postnatal Mortality in Mice. Vaccine 2019, 37, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, M.S.; Hecker, Y.P.; Quintana, S.; Pérez, S.E.; Leunda, M.R.; Cantón, G.J.; Cobo, E.R.; Moore, D.P.; Odeón, A.C. Immunization with Inactivated Antigens of Neospora Caninum Induces Toll-like Receptors 3, 7, 8 and 9 in Maternal-Fetal Interface of Infected Pregnant Heifers. Veterinary Parasitology 2017, 243, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pelayo, L.; García-Sánchez, M.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Horcajo, P.; Gutiérrez-Expósito, D.; Espinosa, J.; Benavides, J.; Osoro, K.; Pfarrer, C.; et al. Crosstalk between Neospora Caninum and the Bovine Host at the Maternal-Foetal Interface Determines the Outcome of Infection. Vet Res 2020, 51, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, T.; Nishikawa, Y. Advances in Vaccine Development and the Immune Response against Toxoplasmosis in Sheep and Goats. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 951584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuo, W.; Feng, X.; Cao, L.; Vinyard, B.; Dubey, J.P.; Fetterer, R.; Jenkins, M. Vaccination with Neospora Caninum-Cyclophilin and -Profilin Confers Partial Protection against Experimental Neosporosis-Induced Abortion in Sheep. Vaccine 2021, 39, 4534–4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza-Morales, L.F.; Fiorani, F.; Morán, K.D.; Hecker, Y.P.; Cirone, K.M.; Sánchez-López, E.F.; Ramos-Duarte, V.A.; Corigliano, M.G.; Bilbao, M.G.; Clemente, M.; et al. Immunogenicity, Safety and Dual DIVA-like Character of a Recombinant Candidate Vaccine against Neosporosis in Cattle. Acta Trop 2024, 257, 107293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bengoa-Luoni, S.A.; Corigliano, M.G.; Sánchez-López, E.; Albarracín, R.M.; Legarralde, A.; Ganuza, A.; Clemente, M.; Sander, V.A. The Potential of a DIVA-like Recombinant Vaccine Composed by rNcSAG1 and rAtHsp81.2 against Vertical Transmission in a Mouse Model of Congenital Neosporosis. Acta Trop 2019, 198, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marugán-Hernández, V.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Aguado-Martínez, A.; Jiménez-Ruíz, E.; Álvarez-García, G. Transgenic Neospora Caninum Strains Constitutively Expressing the Bradyzoite NcSAG4 Protein Proved to Be Safe and Conferred Significant Levels of Protection against Vertical Transmission When Used as Live Vaccines in Mice. Vaccine 2011, 29, 7867–7874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Quinn, H.; Ryce, C.; Reichel, M.P.; Ellis, J.T. Reduction in Transplacental Transmission of Neospora Caninum in Outbred Mice by Vaccination. International Journal for Parasitology 2005, 35, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojo-Montejo, S.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; López-Pérez, I.; Risco-Castillo, V.; Prenafeta, A.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Evaluation of the Protection Conferred by a Naturally Attenuated Neospora Caninum Isolate against Congenital and Cerebral Neosporosis in Mice. Vet Res 2012, 43, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winzer, P.; Imhof, D.; Anghel, N.; Ritler, D.; Müller, J.; Boubaker, G.; Aguado-Martinez, A.; Ortega-Mora, L.-M.; Ojo, K.K.; VanVoorhis, W.C.; et al. The Impact of BKI-1294 Therapy in Mice Infected With the Apicomplexan Parasite Neospora Caninum and Re-Infected During Pregnancy. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 587570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, Y.P.; Moore, D.P.; Quattrocchi, V.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J.; Verna, A.; Leunda, M.R.; Morrell, E.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Zamorano, P.; Venturini, M.C.; et al. Immune Response and Protection Provided by Live Tachyzoites and Native Antigens from the NC-6 Argentina Strain of Neospora Caninum in Pregnant Heifers. Veterinary Parasitology 2013, 197, 436–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojo-Montejo, S.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; Pérez-Zaballos, F.; Rodríguez-Marcos, S.; Blanco-Murcia, J.; Rodríguez-Bertos, A.; Prenafeta, A.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Effect of Vaccination of Cattle with the Low Virulence Nc-Spain 1H Isolate of Neospora Caninum against a Heterologous Challenge in Early and Mid-Gestation. Vet Res 2013, 44, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.H.; Jackson, J.A.; Sobecki, B.; Choromanski, L.; Olsen, M.; Meinert, T.; Frank, R.; Reichel, M.P.; Ellis, J.T. On the Efficacy and Safety of Vaccination with Live Tachyzoites of Neospora Caninum for Prevention of Neospora-Associated Fetal Loss in Cattle. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2013, 20, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imhof, D.; Pownall, W.R.; Monney, C.; Oevermann, A.; Hemphill, A. A Listeria Monocytogenes-Based Vaccine Formulation Reduces Vertical Transmission and Leads to Enhanced Pup Survival in a Pregnant Neosporosis Mouse Model. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imhof, D.; Pownall, W.; Hänggeli, K.P.A.; Monney, C.; Román, L.R.-S.; Ortega-Mora, L.-M.; Forterre, F.; Oevermann, A.; Hemphill, A. Immunization with a Multivalent Listeria Monocytogenes Vaccine Leads to a Strong Reduction in Vertical Transmission and Cerebral Parasite Burden in Pregnant and Non-Pregnant Mice Infected with Neospora Caninum. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pownall, W.R.; Imhof, D.; Trigo, N.F.; Ganal-Vonarburg, S.C.; Plattet, P.; Monney, C.; Forterre, F.; Hemphill, A.; Oevermann, A. Safety of a Novel Listeria Monocytogenes-Based Vaccine Vector Expressing NcSAG1 (Neospora Caninum Surface Antigen 1). Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021, 11, 675219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, M.; Maleki, B.; Kordi, B.; Majidiani, H.; Nazari, N.; Irannejad, H.; Asghari, A. Towards the First Multiepitope Vaccine Candidate against Neospora Caninum in Mouse Model: Immunoinformatic Standpoint. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022, 2644667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, A.; Kordi, B.; Maleki, B.; Majidiani, H.; Shams, M.; Naserifar, R. Neospora Caninum SRS2 Protein: Essential Vaccination Targets and Biochemical Features for Next-Generation Vaccine Design. Biomed Res Int 2022, 2022, 7070144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, Z. The Combination of Vaccines and Adjuvants to Prevent the Occurrence of High Incidence of Infectious Diseases in Bovine. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1243835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansilla, F.C.; Quintana, M.E.; Cardoso, N.P.; Capozzo, A.V. Fusion of Foreign T-Cell Epitopes and Addition of TLR Agonists Enhance Immunity against Neospora Caninum Profilin in Cattle. Parasite Immunology 2016, 38, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Débare, H.; Moiré, N.; Ducournau, C.; Schmidt, J.; Laakmann, J.-D.; Schwarz, R.T.; Dimier-Poisson, I.; Debierre-Grockiego, F. Neospora Caninum Glycosylphosphatidylinositols Used as Adjuvants Modulate Cellular Immune Responses Induced in Vitro by a Nanoparticle-Based Vaccine. Cytokine 2021, 144, 155575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, B.; Lim, J.M.; Yu, B.; Song, S.; Neeli, P.; Sobhani, N.; K, P.; Bonam, S.R.; Kurapati, R.; Zheng, J.; et al. The Next-Generation DNA Vaccine Platforms and Delivery Systems: Advances, Challenges and Prospects. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1332939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Pratama, A.C.; Qiu, H.; Liu, Z.; He, F. Toward Innovative Veterinary Nanoparticle Vaccines. Animal Diseases 2024, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, D.S.; Dubey, J.P. Effects of Sulfadiazine and Amprolium on Neospora Caninum (Protozoa: Apicomplexa) Infections in Mice. J Parasitol 1990, 76, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.P.; Schares, G. Neosporosis in Animals--the Last Five Years. Vet Parasitol 2011, 180, 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Sánchez, R.; Vázquez, P.; Ferre, I.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Treatment of Toxoplasmosis and Neosporosis in Farm Ruminants: State of Knowledge and Future Trends. CTMC 2018, 18, 1304–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Aguado, A.; Laleu, B.; Balmer, V.; Ritler, D.; Hemphill, A. In Vitro Screening of the Open Source Pathogen Box Identifies Novel Compounds with Profound Activities against Neospora Caninum. Int J Parasitol 2017, 47, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Winzer, P.A.; Samby, K.; Hemphill, A. In Vitro Activities of MMV Malaria Box Compounds against the Apicomplexan Parasite Neospora Caninum, the Causative Agent of Neosporosis in Animals. Molecules 2020, 25, 1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Xue, Y.; Pei, Y.; Yin, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q. Construction of Luciferase-Expressing Neospora Caninum and Drug Screening. Parasit Vectors 2024, 17, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, M.; Nagai, J.; Kurata, R.; Shimizu, K.; Cui, X.; Isagawa, T.; Semba, H.; Ishihara, J.; Yoshida, Y.; Takeda, N.; et al. Establishment of Novel High-Standard Chemiluminescent Assay for NTPase in Two Protozoans and Its High-Throughput Screening. Mar Drugs 2020, 18, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurata, R.; Harada, M.; Nagai, J.; Cui, X.; Isagawa, T.; Semba, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Takeda, N.; Maemura, K.; Yonezawa, T. Nucleoside Triphosphate Hydrolases Assay in Toxoplasm Gondii and Neospora Caninum for High-Throughput Screening Using a Robot Arm. J Vis Exp 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L.M.; De Luca, G.; Abichabki, N.D.L.M.; Brochi, J.C.V.; Baroni, L.; Abreu-Filho, P.G.; Yatsuda, A.P. Atovaquone, Chloroquine, Primaquine, Quinine and Tetracycline: Antiproliferative Effects of Relevant Antimalarials on Neospora Caninum. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet. 2021, 30, e022120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Lima, Â.C.; Nolasco, M.; Freitas, L.D.S.; Pinheiro, A.M.; de Carvalho, C.A.L.; de Freitas, H.F.; Pita, S.S. da R.; Vieira, I.J.C.; Braz Filho, R.; Branco, A. A New Cyclodipeptide from Tetragonisca Angustula Honey Active against Neospora Caninum and in Silico Study. Nat Prod Res 2024, 38, 2909–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Xie, S.; Min, P.; Li, H.; Zhao, F.; Liu, M.; Jin, W.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Jia, L. Protective Effect of Inonotus Obliquus Polysaccharide on Mice Infected with Neospora Caninum. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 261, 129906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Hu, K.; Yang, Z.; Wei, Z. Efficacy of Cordycepin against Neospora Caninum Infection in Vitro and in Vivo. Vet Parasitol 2024, 331, 110284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojo, K.K.; Reid, M.C.; Kallur Siddaramaiah, L.; Müller, J.; Winzer, P.; Zhang, Z.; Keyloun, K.R.; Vidadala, R.S.R.; Merritt, E.A.; Hol, W.G.J.; et al. Neospora Caninum Calcium-Dependent Protein Kinase 1 Is an Effective Drug Target for Neosporosis Therapy. PLoS One 2014, 9, e92929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, J.A.; Alday, P.H.; Choi, R.; Khim, M.; Staker, B.L.; Hulverson, M.A.; Ojo, K.K.; Fan, E.; Van Voorhis, W.C.; Doggett, J.S. Bumped Kinase Inhibitors Inhibit Both Toxoplasma Gondii MAPKL1 and CDPK1. ACS Infect Dis 2025, 11, 1552–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, D.; Anghel, N.; Winzer, P.; Balmer, V.; Ramseier, J.; Hänggeli, K.; Choi, R.; Hulverson, M.A.; Whitman, G.R.; Arnold, S.L.M.; et al. In Vitro Activity, Safety and in Vivo Efficacy of the Novel Bumped Kinase Inhibitor BKI-1748 in Non-Pregnant and Pregnant Mice Experimentally Infected with Neospora Caninum Tachyzoites and Toxoplasma Gondii Oocysts. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2021, 16, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, M.C.F.; Imhof, D.; Hänggeli, K.P.A.; Choi, R.; Hulverson, M.A.; Arnold, S.L.M.; Van Voorhis, W.C.; Fan, E.; Roberto, S.-S.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; et al. Efficacy of the Bumped Kinase Inhibitor BKI-1708 against the Cyst-Forming Apicomplexan Parasites Toxoplasma Gondii and Neospora Caninum in Vitro and in Experimentally Infected Mice. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2024, 25, 100553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Anghel, N.; Imhof, D.; Hänggeli, K.; Uldry, A.-C.; Braga-Lagache, S.; Heller, M.; Ojo, K.K.; Ortega-Mora, L.-M.; Van Voorhis, W.C.; et al. Common Molecular Targets of a Quinolone Based Bumped Kinase Inhibitor in Neospora Caninum and Danio Rerio. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anghel, N.; Balmer, V.; Müller, J.; Winzer, P.; Aguado-Martinez, A.; Roozbehani, M.; Pou, S.; Nilsen, A.; Riscoe, M.; Doggett, J.S.; et al. Endochin-Like Quinolones Exhibit Promising Efficacy Against Neospora Caninum in Vitro and in Experimentally Infected Pregnant Mice. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, N.; Imhof, D.; Winzer, P.; Balmer, V.; Ramseier, J.; Haenggeli, K.; Choi, R.; Hulverson, M.A.; Whitman, G.R.; Arnold, S.L.M.; et al. Endochin-like Quinolones (ELQs) and Bumped Kinase Inhibitors (BKIs): Synergistic and Additive Effects of Combined Treatments against Neospora Caninum Infection in Vitro and in Vivo. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist 2021, 17, 92–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, M.; Jiménez-Pelayo, L.; Horcajo, P.; Collantes-Fernández, E.; Ortega-Mora, L.M.; Regidor-Cerrillo, J. Neospora Caninum Infection Induces an Isolate Virulence-Dependent pro-Inflammatory Gene Expression Profile in Bovine Monocyte-Derived Macrophages. Parasit Vectors 2020, 13, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandage, A.K.; Olivera, G.C.; Kanatani, S.; Thompson, E.; Loré, K.; Varas-Godoy, M.; Barragan, A. A Motogenic GABAergic System of Mononuclear Phagocytes Facilitates Dissemination of Coccidian Parasites. Elife 2020, 9, e60528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, C.M.; Oliveira, A.C.M.; Davoli-Ferreira, M.; Silva, M.V.; Santiago, F.M.; Nadipuram, S.M.; Vashisht, A.A.; Wohlschlegel, J.A.; Bradley, P.J.; Silva, J.S.; et al. Neospora Caninum Activates P38 MAPK as an Evasion Mechanism against Innate Immunity. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellani, F.; Leleu, I.; Saidi, N.; Martin, N.; Lecoeur, C.; Werkmeister, E.; Koffi, D.; Trottein, F.; Yapo-Etté, H.; Das, B.; et al. Role of Astrocyte Senescence Regulated by the Non- Canonical Autophagy in the Neuroinflammation Associated to Cerebral Malaria. Brain Behav Immun 2024, 117, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergersen, K.V.; Kavvathas, B.; Ford, B.D.; Wilson, E.H. Toxoplasma Infection Induces an Aged Neutrophil Population in the CNS That Is Associated with Neuronal Protection. J Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Hu, H.; Song, Y.; Zhou, S.; Ayanniyi, O.O.; Xu, Q.; Yue, Z.; Yang, C. Development and Validation of a Machine Learning Algorithm Prediction for Dense Granule Proteins in Apicomplexa. Parasites Vectors 2023, 16, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantier, L.; Poupée-Beaugé, A.; di Tommaso, A.; Ducournau, C.; Epardaud, M.; Lakhrif, Z.; Germon, S.; Debierre-Grockiego, F.; Mévélec, M.-N.; Battistoni, A.; et al. Neospora Caninum: A New Class of Biopharmaceuticals in the Therapeutic Arsenal against Cancer. J Immunother Cancer 2020, 8, e001242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battistoni, A.; Lantier, L.; di Tommaso, A.; Ducournau, C.; Lajoie, L.; Samimi, M.; Coënon, L.; Rivière, C.; Epardaud, M.; Hertereau, L.; et al. Nasal Administration of Recombinant Neospora Caninum Secreting IL-15/IL-15Rα Inhibits Metastatic Melanoma Development in Lung. J Immunother Cancer 2023, 11, e006683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riviere, C.; Aljieli, M.; Mévélec, M.-N.; Lantier, L.; Boursin, F.; Lajoie, L.; Ducournau, C.; Germon, S.; Moiré, N.; Dimier-Poisson, I.; et al. Neospora Caninum as Delivery Vehicle for Anti-PD-L1 scFv-Fc: A Novel Approach for Cancer Immunotherapy. Mol Ther Oncol 2025, 33, 200968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eissa, M.M.; Salem, A.E.; El Skhawy, N. Parasites Revive Hope for Cancer Therapy. Eur J Med Res 2024, 29, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, P.S.; Biggers, P.; Nuru, N.; Versaci, N.; Chirila, M.I.; Darie, C.C.; Neagu, A.-N. Small Biological Fighters Against Cancer: Viruses, Bacteria, Archaea, Fungi, Protozoa, and Microalgae. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.-H.; Chong, A.; Hong, Y.; Min, J.-J. Bioengineering of Bacteria for Cancer Immunotherapy. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, J.W.; Dekker, L.; Owen, K.A.; Barnes, C.P. Microbiome Engineering: Engineered Live Biotherapeutic Products for Treating Human Disease. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 1000873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Tang, Y.; Xu, W.; Hao, X.; Li, Y.; Huang, S.; Xiang, D.; Wu, J. Bacteria-Based Immunotherapy for Cancer: A Systematic Review of Preclinical Studies. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1140463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, D.; Saberi, R.; Sharif, M.; Sarvi, S.; Hosseini, S.A.; Moosazadeh, M.; Hosseininejad, Z.; Chegeni, T.N.; Daryani, A. Seroprevalence of Neospora Caninum Infection in Dog Population Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acta Parasitol 2020, 65, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N.; Hogan, M.J.; Weissman, D. Recent Advances in mRNA Vaccine Technology. Curr Opin Immunol 2020, 65, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomazic, M.L.; Marugan-Hernandez, V.; Rodriguez, A.E. Next-Generation Technologies and Systems Biology for the Design of Novel Vaccines Against Apicomplexan Parasites. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 8, 800361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, D.; Pownall, W.R.; Schlange, C.; Monney, C.; Ortega-Mora, L.-M.; Ojo, K.K.; Van Voorhis, W.C.; Oevermann, A.; Hemphill, A. Vaccine-Linked Chemotherapy Approach: Additive Effects of Combining the Listeria Monocytogenes-Based Vaccine Lm3Dx_NcSAG1 With the Bumped Kinase Inhibitor BKI-1748 Against Neospora Caninum Infection in Mice. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 901056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, V.; Holmes, M.J.; Bastos, M.S.; Wek, R.C.; Sullivan, W.J. Cap-Independent Translation Directs Stress-Induced Differentiation of the Protozoan Parasite Toxoplasma Gondii. bioRxiv 2024, 2024.09.17.613578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Licon, M.H.; Giuliano, C.J.; Chan, A.W.; Chakladar, S.; Eberhard, J.N.; Shallberg, L.A.; Chandrasekaran, S.; Waldman, B.S.; Koshy, A.A.; Hunter, C.A.; et al. A Positive Feedback Loop Controls Toxoplasma Chronic Differentiation. Nat Microbiol 2023, 8, 889–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Holmes, M.J.; Hong, H.J.; Thaprawat, P.; Kannan, G.; Huynh, M.-H.; Schultz, T.L.; Licon, M.H.; Lourido, S.; Dong, W.; et al. Translation Initiation Factor eIF1.2 Promotes Toxoplasma Stage Conversion by Regulating Levels of Key Differentiation Factors. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).