1. Introduction

Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus (SEZ) is a commensal bacterium found on the skin and mucous membranes of horses. As an opportunistic pathogen, it can cause a range of infections, including those of the respiratory tract and the reproductive and urinary systems. These infections result in significant illness, economic losses, and complications in managing equine health. Although SEZ can cause clinical respiratory disease in horses, not all exposed horses become ill. Horses carrying these bacteria can still infect other horses, even if they do not show any clinical signs of disease.

Recently, evidence indicates SEZ may also cause severe diseases in humans due to direct contact with infected animals or the consumption of unpasteurized milk and dairy products [1-3]. Human infection caused by SEZ can lead to symptoms ranging from mild skin infection to meningitis and sepsis, especially in individuals with weakened immune systems [4-6]. Respiratory symptoms may arise, including sore throat and pneumonia, particularly if the bacteria spread from direct contact with infected animals [

7]. During November 2021–May 2022, a large SEZ outbreak involving 37 clinical cases was reported in Italy [

8].

SEZ has also been recently identified as the causative agent of severe cases of pneumonia in donkeys in Italy where a novel SEZ sequence type (ST525) was responsible for the death of four donkeys raised on a farm between March and April 2022 [

9].

As a commensal bacterium, there is limited information available about its actual distribution. In a study by the United States Department of Agriculture, bacterial cultures of nasal swabs from 6,000 healthy horses revealed a SEZ prevalence of 9.2% [

10].

Additionally, little is known about the genetic factors that distinguish non-pathogenic strains from pathogenic ones, both in equines and humans.

This study aimed to assess the prevalence of SEZ at both the animal and herd levels in the Italian regions of Abruzzo and Molise, identify risk factors associated with equine disease, and compare the genetic characteristics of SEZ commensal strains with pathogenic strains found in equines and humans. This was accomplished through a cross-sectional study using nasal swab samples.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Target Population

Regulation (EU) 2016/429 [

11] required European Union Member States to set up a computer database for terrestrial-kept animals, including equids. After the entrance into force of the above-mentioned act and related regulations, Italy has transposed those statements with legislative decree No. 302, September 30, 2021 and legislative decree No. 134, August 5, 2022 [

12,

13] which establish the identification and registration system and define the management and operation of the national equine registry. The Italian equine registry allows for searching single equid information by unique identifiers such as the Single Lifetime Identification Document (SLID - also known as passport), the Unique Equine Life Number code (UELN), the Transponder code, or the animal's name. Through the specific interface with personal records is possible to visualize the codes mentioned above along with details regarding the species, breed, sex, date of birth, and the destination for food production or not of the single animal.

According to official data from the Italian equine registry, 474,759 equines were registered in the database as of December 31, 2023, with 18,933 (4%) located in Abruzzo and 4,657 (1%) in Molise. The study population had a median of 44 animals per farm. Of the farms in the territories considered in the analysis, 43% had only 1 animal, 48% had up to 10 animals, 5% had between 11 and 20 animals and 5% had more than 20 animals.

2.2. Sampling Design and Collection

A sampling plan was designed to collect nasal swabs from equines randomly distributed throughout the regions of Abruzzo and Molise. To determine the sample, the animals were considered as the sampling units, with an assumed a priori prevalence of 50%, a confidence level of 95%, and an absolute accuracy of 5%. Based on these parameters, the minimum required number of primary units was 384 animals. About 25% additional animals were sampled to provide a safety margin, increasing the total number of primary units to 478. The sample parameters were defined based on the number of establishments with at least one animal (N =5050) registered in the National Equine Registry.

A sample accompanying form was drafted to collect anamnesis information on the sampled animals, such as the animal's unique identifier, species (equine, asinine or mule), age, sex, and breed, if intended for food production, and any presence of respiratory symptoms. In addition, information on the farm was collected such as the unique registration number, farmed species, type of activity regarding animals of the same species or group of species carried out in the establishment, geographical location, and the name of the establishment operator. Where information on the sample accompanying form was missing, it was retrieved by consulting the National Equine Registry.

Veterinarians collected samples from the nasal cavities of 478 adult horses using sterile swabs. The nostrils were cleaned with paper towels before swabbing the distal nasal cavity, then swabs were placed in a transport medium to be delivered to the laboratory. Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale (IZS) in Teramo, Italy, performed testing.

2.3. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

The animal's unique identifier, sampled species, and establishment unique registration number reported on the form were also registered in the laboratory information system (LIMS) of IZS Teramo. At the end of the registration process, a label with a sequential number was generated to uniquely identify the nasal swab collected from each animal. A database was created using data extracted from LIMS, along with additional information collected via accompanying forms or obtained from the National Equine Registry.

Every entry of animal and establishment data, as well as laboratory results, in the database was double-checked to ensure data quality. The spatial location of each sampled establishment, intended as the physical location in which animals are kept, was plotted on a map using the GIS (Geographic Information System) software (QGIS.org, 2024. QGIS Geographic Information System. QGIS Association.

http://www.qgis.org).

The prevalence of SEZ was calculated at both the animal and farm levels, with a 95% confidence interval determined using exact binomial confidence intervals.

A multivariate statistical analysis was conducted using multivariate logistic regression, with the response variable being the presence or absence of SEZ on the collected swab, and the covariates including sex, species, breed, age category (less than or greater than 15 years, with 15 years serving as the threshold for classifying a horse as "aged” [

14]), symptoms, if the animal was intended for food production, the simultaneous presence of multiple livestock species and presence of dairy species within the same farm. The potential relationship between the presence of SEZ and the covariates included in the model was also assessed using a chi-square test. A two-tailed Mann–Whitney test was used to evaluate age differences between negative and positive animals. All statistical analyses were carried out with R v.4.3.2 (R Development Core Team, 2023).

2.4. PCR, Isolation and Sequencing of SEZ

Nasal swabs were streaked for isolation onto 5% sheep blood agar plates (Microbiol srl, Cagliari, Italy) and incubated at 37±1°C in a 5-10% CO2-enriched atmosphere for 24-72 hours. Streptococcus spp. suspicious colonies were sub-cultured and identified by MALDI-TOF (MALDI Biotyper®, Bruker Daltonics Gmbh & Co. KG, Bremen, Germany). Then, DNA was extracted from isolated colonies for sequencing using Maxwell® RSC Genomic DNA Kit (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) with minor protocol modification. Nasal swabs were also subjected to DNA extraction (Maxwell® RSC Genomic DNA Kit) and then tested in real-time PCR for SEZ by using a commercial kit (Genesig® PrimerdesignTM Ltd, UK).

DNA extraction was performed for a total of 51 strains with minor modifications and NGS was performed through the Illumina platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). For the WGS data analysis, an in-house pipeline (

https://github.com/genpat-it/ngsmanager/) was used and a quality check was performed. To confirm species identification the KmerFinder tool [

15] was used.

In order to verify the correlation between the 51 SEZ genomes, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis was performed through the CFSAN pipeline [

16] using CP001129 (

Streptococcus equi subsp.

zooepidemicus MGCS10565) as a reference.

3. Results

3.1. SEZ Prevalence

Out of the samples collected from the 99 farms, 478 nasal swabs were analyzed for the presence of SEZ. Among these establishments, 56,6% had between 1 and 5 animals.

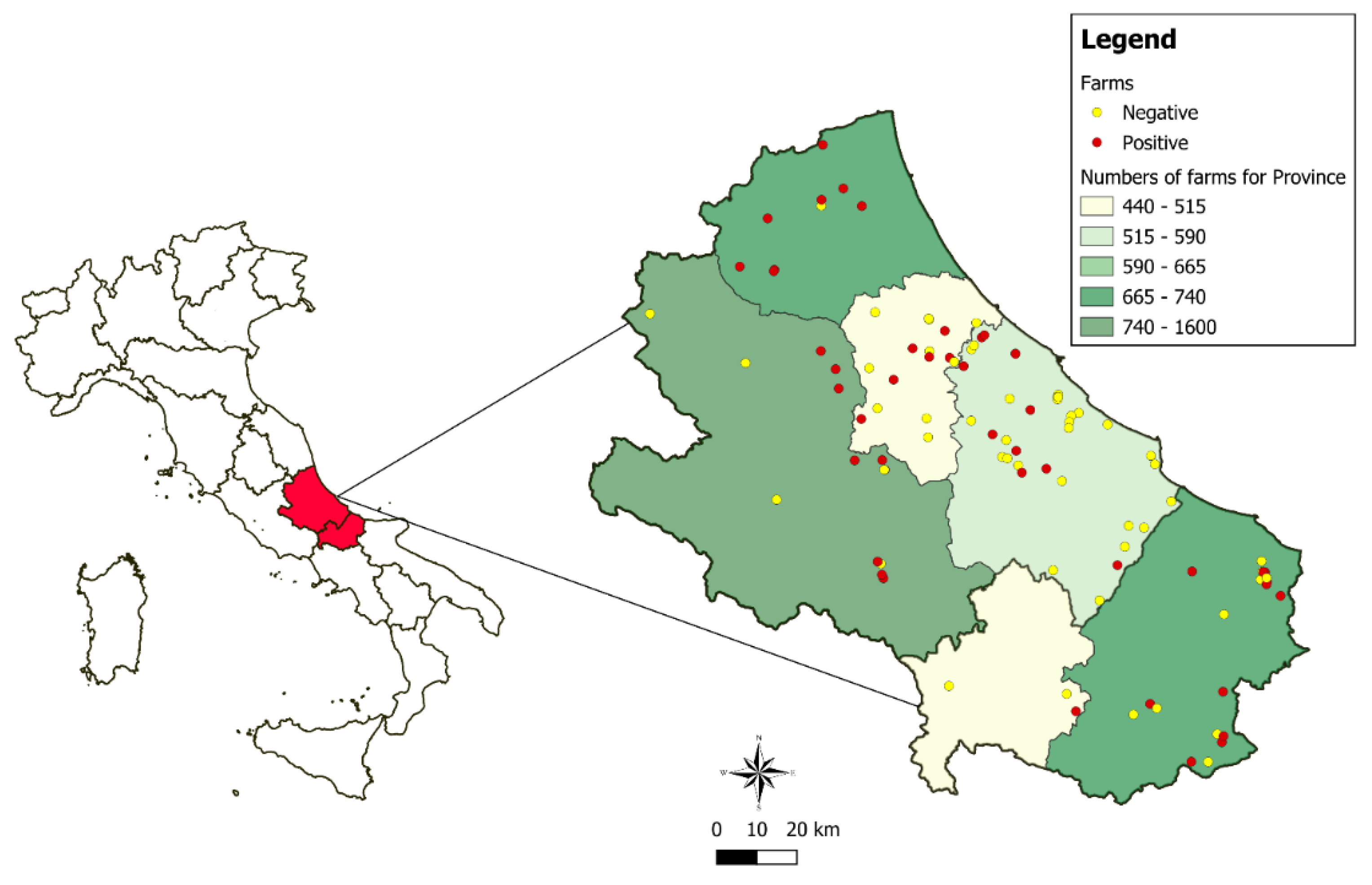

Figure 1 illustrates the geographical distribution of the farms that were tested, highlighting those with positive results.

A total of 144 equines tested positive for SEZ by PCR, resulting in an estimated prevalence of 30.1% (95% CI: 26.2%-34.4%) at the animal level. At the herd level, 45 establishments were classified as positive (P= 45.5%; 95% CI:36.0%-55.3%). The distribution of farms and the number of tested and positive animals by province is shown in

Table 1. For 4 animals, the information regarding the province of the sampled farm could not be traced. As a result, the number of animals tested (N=474) and the number of animals that tested positive (N=143) in

Table 1 do not align with the total number of sampled animals (N=478) and the total number of positive animals (N=144).

The logistic model was not significant, and none of the covariates considered reached significance (p-value>0.05), as shown in

Table 2. The chi-square test results were not statistically significant (p-value<0.05) for all variables examined except for the species. Statistical analysis revealed a significant association between species and the presence of SEZ, with asinine being significantly more positive than equine (chi square= 4.70 p-value = 0.030). The median age of positive animals was 6.5 years, significantly lower (p-value = 0.000, two tails Mann—Whitney Test) than that of negative animals (median age: 10 years).

3.2. Genomic Characterization and Cluster Analysis

A total of 56 strains were isolated from 144 PCR-positive nasal swabs. Of these, 51 underwent whole genome sequencing (WGS), while for 5 it was not possible to proceed due to poor DNA extraction quality, which was insufficient for sequencing. All the 51 genomes were confirmed as SEZ. The MLST analysis showed that the SEZ genomes were classified into 31 Sequence Types (STs) (

Table 3). Among the STs calculated, 14 new STs were identified: ST536, ST538, ST539, ST540, ST541, ST542, ST543, ST544, ST546, ST547, ST549, ST550, ST551 and ST552. The MLST profiles could not be calculated for two isolates (2024.TE.15857.1.2 and 2024.TE.15855.1.2) due to the genome fragmentation. The 51 sequenced genomes came from 23 different farms, including 7 from Molise and 16 from Abruzzo.

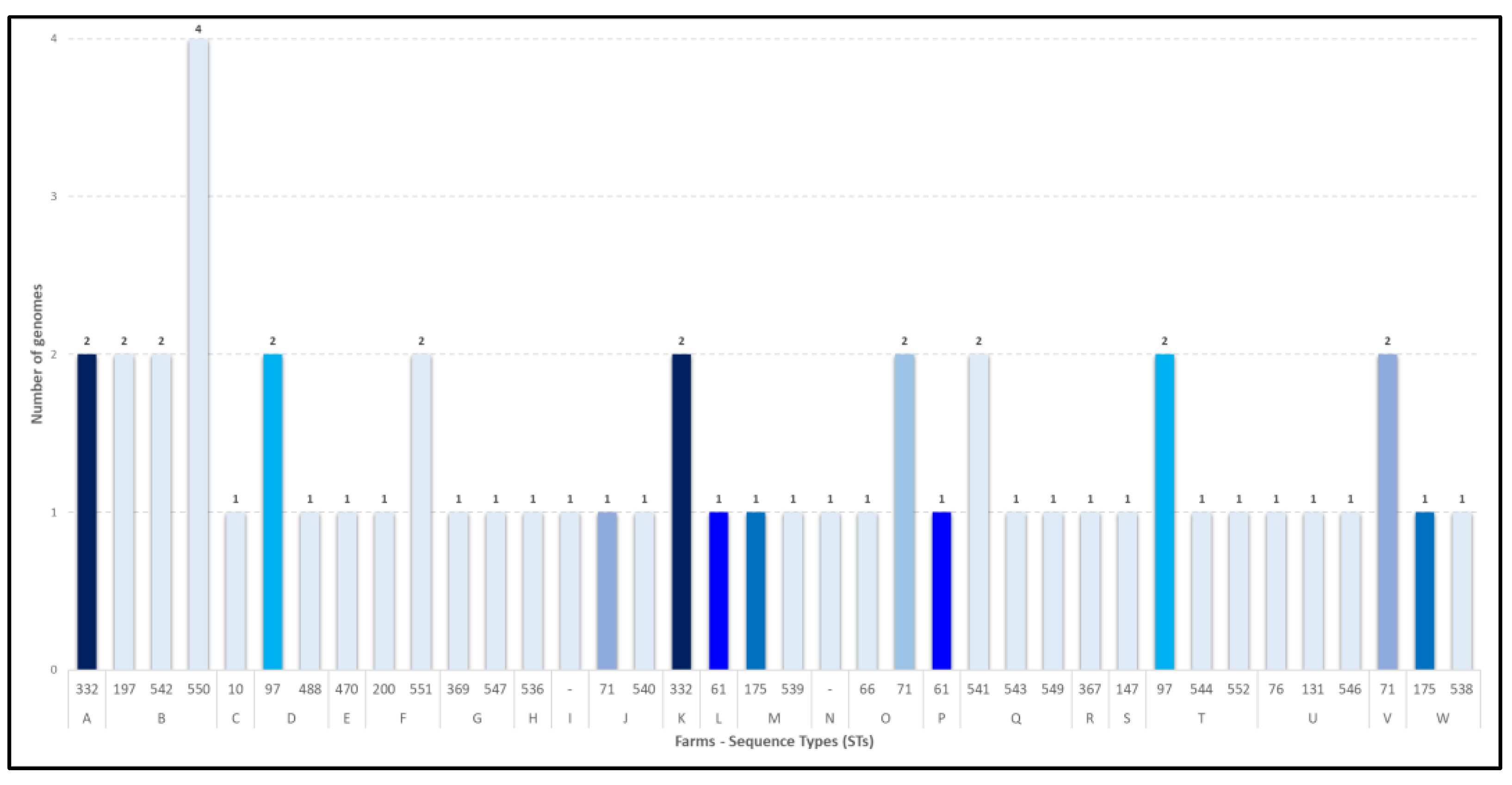

Figure 3 lists the farms and the sequence types identified in each. In nearly half of the farms (N=11), more than one sequence type was detected.

The results of the investigations on the virulence genes are reported in

Table 3. The gene fbp54 encoding for fibronectin–binding proteins were present in 41 isolates. Meanwhile, mf2 and mf3 were identified in 19 and 29 strains, respectively. Interestingly, one isolate (2024.TE.6603.1.55) harboured spel gene, which encodes streptococcal exotoxin L precursor, and spek gene, involved in the production of streptococcal toxin-phage associated. The hasC gene, which product is cell wall surface anchor family protein, was found in 16 isolates.

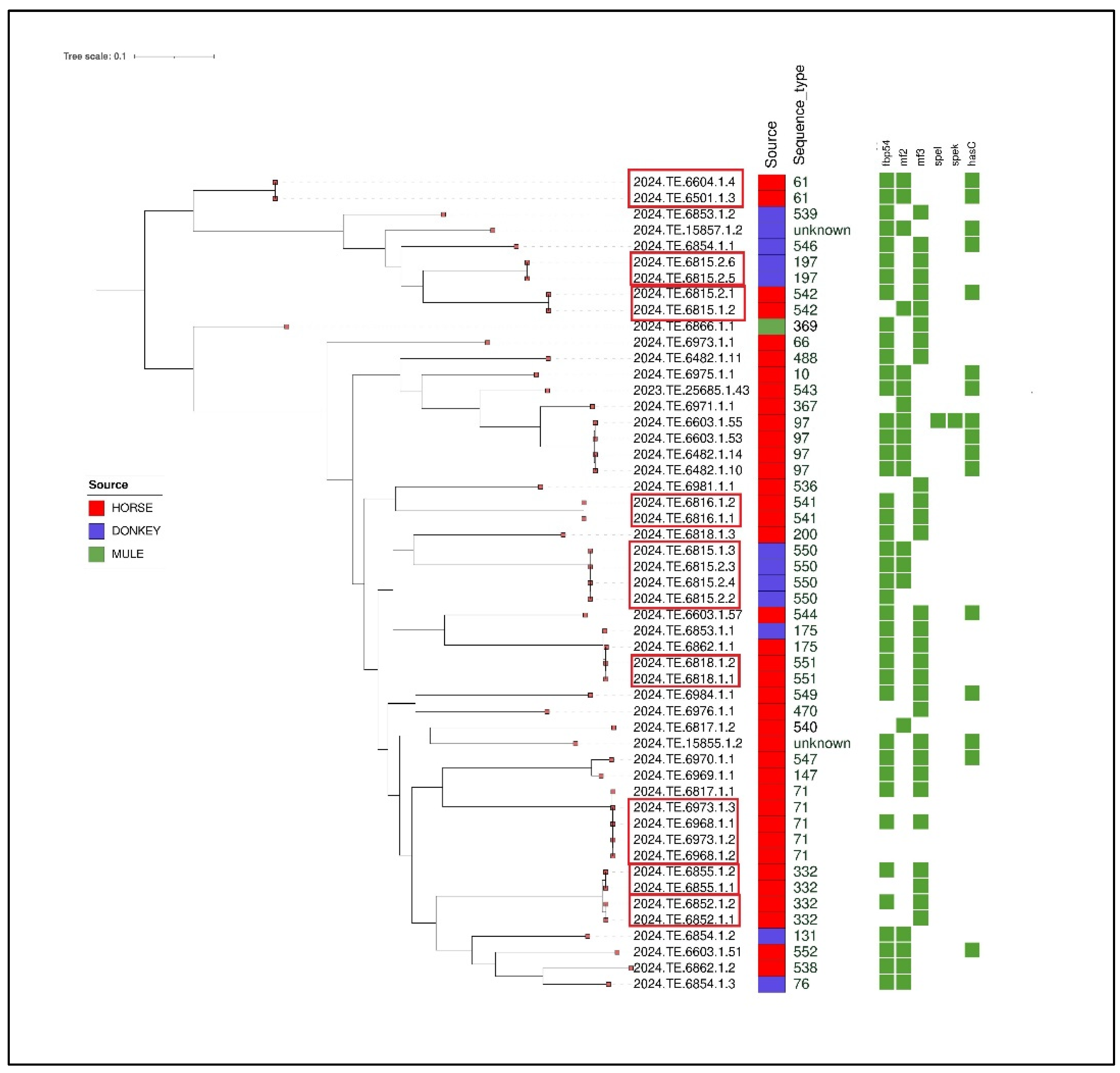

The clustering analysis highlighted the presence of different clusters according to MLST analysis (

Figure 2). Specifically, one strain isolated from a donkey (2024.TE.6815.2.5) and belonging to ST197 clustered with another strain isolated from another donkey from the same breeding. Two other clusters were identified on the same farm. Specifically, four strains isolated from donkeys belong to the ST550 cluster and two strains belonging to novel ST542 were isolated from two horses.

Another cluster was detected among two strains (ST541) isolated from 2 different horses belonging to the same breeder.

Moreover, the SNP analysis revealed another cluster that involved four SEZ strains (ST71) isolated from 4 horses sampled in the provinces of Chieti and L’Aquila from two different farms; meanwhile, another strain (2024.TE.6817.1.1) belonging to ST71, isolated from a different farm in the province of L'Aquila, was distant from the rest of cluster. No epidemiological correlation was found between the three farms.

A similar situation was observed for ST332 strains. Specifically, one cluster was identified for two strains isolated from two horses belonging to the same farm in the province of Isernia, meanwhile, the isolated (2024.TE.6852.1.1) was correlated to another strain (2024.TE.6852.1.2) and both originating from two horses belonging to the same farm in the province of Campobasso. Furthermore, one cluster (ST541) was identified between two horses sampled from the same breeding in the province of Teramo.

Another cluster was identified between two strains belonging to ST551 and isolated from two different horses.

Finally, two strains (ST61) isolated from 2 different horses on the same farm in the province of Campobasso were correlated. Given the relevance assumed by this clone following the outbreak in the “Vestina” area in November 2021-May 2022 [

8], the comparative genomics of these two strains with those belonging to the aforementioned outbreak was performed. The results showed that the strains isolated in this study are not correlated. Animal movement records also revealed that there are no connections between the farm in Campobasso and the one where the outbreak occurred.

The remaining isolates resulted in singletons.

Figure 2.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) midpoint rooted tree obtained from CFSAN pipeline of the 51 SEZ isolates. The first layer represents the source of isolation as shown in the legend. The second layer represents MLST analysis results. Virulence genes are shown in the heatmap with a green color. The clusters identified with SNP analysis were highlighted with a red box. The visualization of genes profiles and genes presence/absence was visualized using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) (

https://itol.embl.de/).

Figure 2.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) midpoint rooted tree obtained from CFSAN pipeline of the 51 SEZ isolates. The first layer represents the source of isolation as shown in the legend. The second layer represents MLST analysis results. Virulence genes are shown in the heatmap with a green color. The clusters identified with SNP analysis were highlighted with a red box. The visualization of genes profiles and genes presence/absence was visualized using the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) (

https://itol.embl.de/).

Figure 3.

Sequence types identified across sampled farms, with each farm represented by a unique letter. Isolates identified as singletons are highlighted in light blue.

Figure 3.

Sequence types identified across sampled farms, with each farm represented by a unique letter. Isolates identified as singletons are highlighted in light blue.

4. Discussion

Streptococcus equi subsp.

zooepidemicus (SEZ) is a commensal bacterium found in the pharyngeal mucosa of various animal species. Studies of SEZ in equids are mostly limited to observations after symptoms appear or seroprevalence data, where the detection of antibodies implies prior exposure but does not confirm carrier status. The literature, however, does not allow for population-wide inferences, as it often relies on opportunistic sampling. The only probabilistic study, conducted by Libardoni et al. in Brazil [

17] and focused on estimating the prevalence of

Streptococcus equi subsp.

equi, reported a prevalence of 2.37% at the animal level and 5.86% at the herd level.

This study not only assesses the prevalence of SEZ in equid populations in the Abruzzo and Molise regions (Italy), but also identifies risk factors associated with SEZ presence and explores the genetic characteristics of the circulating SEZ strains. Traditional strain typing methods do not capture SEZ’s genomic diversity, distinguishing only

Streptococcus equi subsp.

zooepidemicus from other streptococci. Following a local human outbreak linked to SEZ from raw milk cheeses [

8] and the emergence of a highly virulent strain that caused significant mortality in a donkey herd [

9], it became essential to assess whether these strains differed genetically and in terms of virulence from the typical strains found in circulation.

Our findings reveal a SEZ prevalence of 30.1% at the animal level and 45.5% at the herd level, substantially higher than the prevalence of

Streptococcus equi subsp.

equi reported by Libardoni et al., [

17] despite our smaller sample size. The higher percentage of animals sampled in this study (456/23,588 versus 1,010/522,578 in the Brazilian study) might account for this disparity. Notably, our risk factor analysis found no significant associations with SEZ presence. Variables such as respiratory symptoms or the presence of dairy species on the premises did not correlate with SEZ prevalence, suggesting that pharyngeal SEZ colonization may not necessarily lead to respiratory symptoms. Further, intermittent bacterial shedding and inconsistencies in sample collection techniques across independent professionals may have impacted detection rates.

Interestingly, donkeys had a significantly higher prevalence of SEZ than horses. This could reflect donkeys’ role as asymptomatic carriers, as they are generally susceptible to respiratory pathogens, though they often exhibit milder symptoms compared to horses. This species-specific susceptibility highlights a potential area for further research, particularly to identify mechanisms that could inform more tailored management practices for donkeys to limit SEZ transmission.

Another important observation is the significantly younger age of SEZ-positive animals compared to negative ones, suggesting age-related susceptibility factors. This association invites further study into the genetic, environmental, and nutritional influences on younger animals, which may help to improve management strategies across different age groups.

Genomic analysis revealed a marked heterogeneity among the circulating strains. Fourteen new STs were identified, while the remaining seventeen had been previously reported. In particular, ST200 and ST10 had been detected in both healthy dogs and those with respiratory symptoms [

18,

19]. ST147, in contrast, was previously isolated from a horse breeding facility in China and from a mare in Argentina in 2017 [

20,

21]. ST71 was isolated from the respiratory tracts of horses in the UK and USA over an extended period [

22]. The fact that the identified genotypes have also been reported in different countries and host species suggests that there is no specific adaptation to a particular host.

On the other hand, genomic analysis revealed a significant similarity to group A streptococci (GAS), particularly those linked to GAS infections. Most SEZ strains possessed the fpb54 gene, encoding a streptococcal fibronectin-binding protein—a critical factor for GAS infection, facilitating attachment to human buccal epithelial cells [

23,

24]. Additionally, 19 of the 51 SEZ strains carried the mf2 gene, a virulence factor associated with

Streptococcus pyogenes prophages that is rarely detected in SEZ [

9]. Another GAS-associated virulence factor, mf3, encoding for mitogen factor 3 (MF3) with DNase activity, was also identified [

25].

In one isolate, both the spel and spek genes were detected, which are associated with streptococcal exotoxin production. The spel gene, first detected in SEZ in 2005, shares over 98% identity with S. pyogenes’ spel gene, indicating possible horizontal gene transfer. The superantigenic toxin encoded by the spel gene is a widely distributed virulence factor in S. equi subsp. equi, but is less common in SEZ [

26]. The spek gene, showing high similarity to the seeL gene, plays a role in immune evasion by suppressing phagocyte recruitment [

27]. Consequently, the isolate 2024.TE.6603.1.55 exhibits considerable virulence potential.

Finally, this study confirmed the presence of the hasC gene from the has operon, encoding UDP-glucose dehydrogenase, necessary for the synthesis of SEZ’s hyaluronic acid capsule [

28]. This capsule, mimicking human connective tissue, reduces the host’s immune response, presenting another virulence mechanism [

29].

5. Conclusions

Overall, this study offers valuable insights into SEZ’s distribution in the target regions, identifying substantial strain variability and a higher prevalence in donkeys. The lack of association with cohabitation with dairy species contrasts with prior assumptions about risk factors. These findings underscore the need for additional research to determine species-specific susceptibility mechanisms and to identify factors that activate SEZ virulence, which could hold implications for both animal and public health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, FC, AP and CEDF; methodology, FC, AP, MC; software, FC, MC, AC; validation, DA, AA, MR, MCC and AP; formal analysis, FC, MC; investigation, ADB, AG, GV.; resources, AP.; data curation, FC, MC, AC.; writing—original draft preparation, FC, MC, AC; writing—review and editing, AP, AA, DA; visualization, AC, MC, FC; supervision, AP, CEDF; project administration, AP; funding acquisition, AP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Data Availability Statement

All sequences are publicly available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. The accession numbers are detailed in

Table 3.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to our independent professional colleagues operating in the field for their invaluable collaboration and expertise throughout this study. Their contributions have been essential to the successful completion of this research.

We also wish to thank the staff at the peripheral diagnostic units of the IZSAM for their continuous support and dedication. Their hard work and commitment were fundamental to the successful execution of the study, and we greatly appreciate their involvement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SEZ |

Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus

|

| IZSAM |

Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale dell’Abruzzo e Molise |

| WGS |

Whole Genome Sequencing |

References

- Kuusi, M.; Lahti, E.; Virolainen, A.; Hatakka, M.; Vuento, R.; Rantala, L.; Vuopio-Varkila, J.; Seuna, E.; Karppelin, M.; Hakkinen, M.; Takkinen, J.; Gindonis, V.; Siponen, K.; Huotari, K. An outbreak of Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus associated with consumption of fresh goat cheese. BMC Infect Dis 2006, 6, 36–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balter, S.; Benin, A.; Pinto, S.W.; Teixeira, L.M.; Alvim, G.G.; Luna, E.; Jackson, D.; LaClaire, L.; Elliott, J.; Facklam, R.; Schuchat, A. Epidemic nephritis in Nova Serrana, Brazil. Lancet 2000, 355, 1776–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres Rosângela S. L., A.; Santos Talita, Z.; Bernardes Andre F., L.; Soares Patricia, A.; Soares Ana C., C.; Dias Ricardo, S. Outbreak of Glomerulonephritis Caused by Streptococcus zooepidemicus SzPHV5 Type in Monte Santo de Minas, Minas Gerais, Brazil. J Clin Microbiol 2018, 56, 10.1128–jcm.00845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madzar, D.; Hagge, M.; Moller, S.; Regensburger, M.; Lee, D.; Schwab, S.; Jantsch, J. Endogenous endophthalmitis complicating Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus meningitis: a case report. BMC Res Notes 2015, 8, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, G.; Soffritti, A.; Mantovani, M.; Digaetano, M.; Prandini, F.; Sarti, M.; Bedini, A.; Meschiari, M.; Mussini, C. Streptococcus equi Subspecies zooepidemicus Endocarditis and Meningitis in a 62-Year-Old Horse Rider Patient: A Case Report and Literature Review. Microorganisms 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minces, L.R.; Brown, P.J.; Veldkamp, P.J. Human meningitis from Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus acquired as zoonoses. Epidemiol Infect 2011, 139, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelkonen, S.; Lindahl, S.B.; Suomala, P.; Karhukorpi, J.; Vuorinen, S.; Koivula, I.; Vaisanen, T.; Pentikainen, J.; Autio, T.; Tuuminen, T. Transmission of Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus infection from horses to humans. Emerg Infect Dis 2013, 19, 1041–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosica, S.; Chiaverini, A.; De Angelis, M.E.; Petrini, A.; Averaimo, D.; Martino, M.; Rulli, M.; Saletti, M.A.; Cantelmi, M.C.; Ruggeri, F.; Lodi, F.; Calistri, P.; Cito, F.; Camma, C.; Di Domenico, M.; Rinaldi, A.; Fazii, P.; Cedrone, F.; Di Martino, G.; Accorsi, P.; Morelli, D.; De Luca, N.; Pomilio, F.; Parruti, G.; Savini, G. Severe Streptococcus equi Subspecies zooepidemicus Outbreak from Unpasteurized Dairy Product Consumption, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 2023, 29, 1020–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantelmi, M.C.; Merola, C.; Averaimo, D.; Chiaverini, A.; Cito, F.; Cocco, A.; Di Teodoro, G.; De Angelis, M.E.; Di Bernardo, D.; Auzino, D.; Petrini, A. Identification of the Novel Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus Sequence Type 525 in Donkeys of Abruzzo Region, Italy. Pathogens 2023, 12, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Epidemiology and Animal Health; USDA, Animal and Plant Health Inspective Service (APHIS) Infectious Upper Respiratory Disease in U.S. Horses: Laboratory Results for Influenza Serology and Nasal Swab Culture for Streptococcus Isolation. 2001.

- European Parliament and of the Council Regulation (EU) 2016/429 of the European Parliament and of the Council of on transmissible animal diseases and amending and repealing certain acts in the area of animal health (‘Animal Health Law’). 2016 Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2016/429/oj. 9 March.

- Minstero della Salute di concerto con il Ministero delle Politiche Agricole, Alimentari e Forestali DECRETO 30 settembre 2021 Gestione e funzionamento dell'anagrafe degli equini. (21A07453) (GU Serie Generale n.302 del 21-12-2021). 2021 Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2021/12/21/21A07453/sg.

- Il Presidente della Repubblica Decreto legislativo 5 agosto 2022, n. Il Presidente della Repubblica Decreto legislativo 5 agosto 2022, n.134, Disposizioni in materia di sistema di identificazione e registrazione degli operatori, degli stabilimenti e degli animali per l'adeguamento della normativa nazionale alle disposizioni del regolamento (UE) 2016/429, ai sensi dell'articolo 14, comma 2, lettere a), b), g), h), i) e p), della legge 22 aprile 2021, n. 53. 2022 Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2022/09/12/22G00142/sg.

- Mcgowan, C. Welfare of Aged Horses. Animals 2011, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, M.V.; Cosentino, S.; Lukjancenko, O.; Saputra, D.; Rasmussen, S.; Hasman, H.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Ussery, D.W.; Lund, O. Benchmarking of methods for genomic taxonomy. J Clin Microbiol 2014, 52, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.; Pettengill, J.B.; Luo, Y.; Payne, J.; Shpuntoff, A.; Rand, H.; Strain, E. CFSAN SNP Pipeline: an automated method for constructing SNP matrices from next-generation sequence data. PeerJ Comput Sci 2015, 1, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libardoni, F.; Machado, G.; Gressler, L.T.; Kowalski, A.P.; Diehl, G.N.; dos Santos, L.C.; Corbellini, L.G.; de Vargas, A.C. Prevalence of Streptococcus equi subsp. equi in horses and associated risk factors in the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Res Vet Sci 2016, 104, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalker, V.J.; Waller, A.; Webb, K.; Spearing, E.; Crosse, P.; Brownlie, J.; Erles, K. Genetic diversity of Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus and doxycycline resistance in kennelled dogs. J Clin Microbiol 2012, 50, 2134–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, E.R.; Jones, G.M.C.; Suarez-Bonnet, A.; Waller, A.S.; Priestnall, S.L. Streptococcus zooepidemicus in dogs: Exploring a canine pathogen through multilocus sequence typing. Vet Microbiol 2024, 292, 110059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, B.; Su, L. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Phenotypic Analysis of Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus Sequence Type 147 Isolated from China. Microorganisms 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamar, G.C.; Bustos, C.P.; Guillemi, E.C.; Becu, T.; Ivanissevich, A.; Mesplet, M.; Munoz, A.J. Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus: High molecular diversity of Argentinian strains isolated from mares with endometritis. Res Vet Sci 2024, 173, 105242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, K.; Jolley, K.A.; Mitchell, Z.; Robinson, C.; Newton, J.R.; Maiden, M.C.J.; Waller, A. Development of an unambiguous and discriminatory multilocus sequence typing scheme for the Streptococcus zooepidemicus group. Microbiology (Reading) 2008, 154, 3016–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, H.S.; Dale, J.B.; Hasty, D.L. Host cell specific adhesins of group A streptococci. Adv Exp Med Biol 1997, 418, 605–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, H.S.; Dale, J.B.; Hasty, D.I. Differential effects of the streptococcal fibronectin-binding protein, FBP54, on adhesion of group A streptococci to human buccal cells and HEp-2 tissue culture cells. Infect Immun 1996, 64, 2415–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Tsou, C.; Kuo, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, J.; Liao, P. Differential secretomics of Streptococcus pyogenes reveals a novel peroxide regulator (PerR)-regulated extracellular virulence factor mitogen factor 3 (MF3). Mol Cell Proteomics 2011, 10, M110.007013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alber, J.; El-Sayed, A.; Estoepangestie, S.; Lammler, C.; Zschock, M. Dissemination of the superantigen encoding genes seeL, seeM, szeL and szeM in Streptococcus equi subsp. equi and Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus. Vet Microbiol 2005, 109, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, E.R.A.; Wu, J.; Bordin, A.I.; Lawhon, S.D.; Cohen, N.D. Differences in the Accessory Genomes and Methylomes of Strains of Streptococcus equi subsp. equi and of Streptococcus equi subsp. zooepidemicus Obtained from the Respiratory Tract of Horses from Texas. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e0076421–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, L.M.; Hugenholtz, P.; Nielsen, L.K. Evolution of the hyaluronic acid synthesis (has) operon in Streptococcus zooepidemicus and other pathogenic streptococci. J Mol Evol 2008, 67, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crater, D.L.; van de Rijn, I. Hyaluronic Acid Synthesis Operon (has) Expression in Group A Streptococci (∗). J Biol Chem 1995, 270, 18452–18458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).