Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Nutrition Quotient

2.4. Exercise Load Test

2.5. Anthropometric Parameters and Blood Pressure

2.6. The Measurement of Lactate and Glucose in Whole Blood

2.7. Blood Collection

2.8. Fatigue Parameters

2.9. Oxidative Stress Related Markers

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Information of the Study Subjects

3.2. Exercise Performance, Fasting Glucose, and Blood Pressure of Subjects According to LMWP Consumption

3.3. Comparison of Heart Rate Changes According to LMWP Consumption

3.4. Comparison of Blood Lactate Levels According to LMWP Consumption

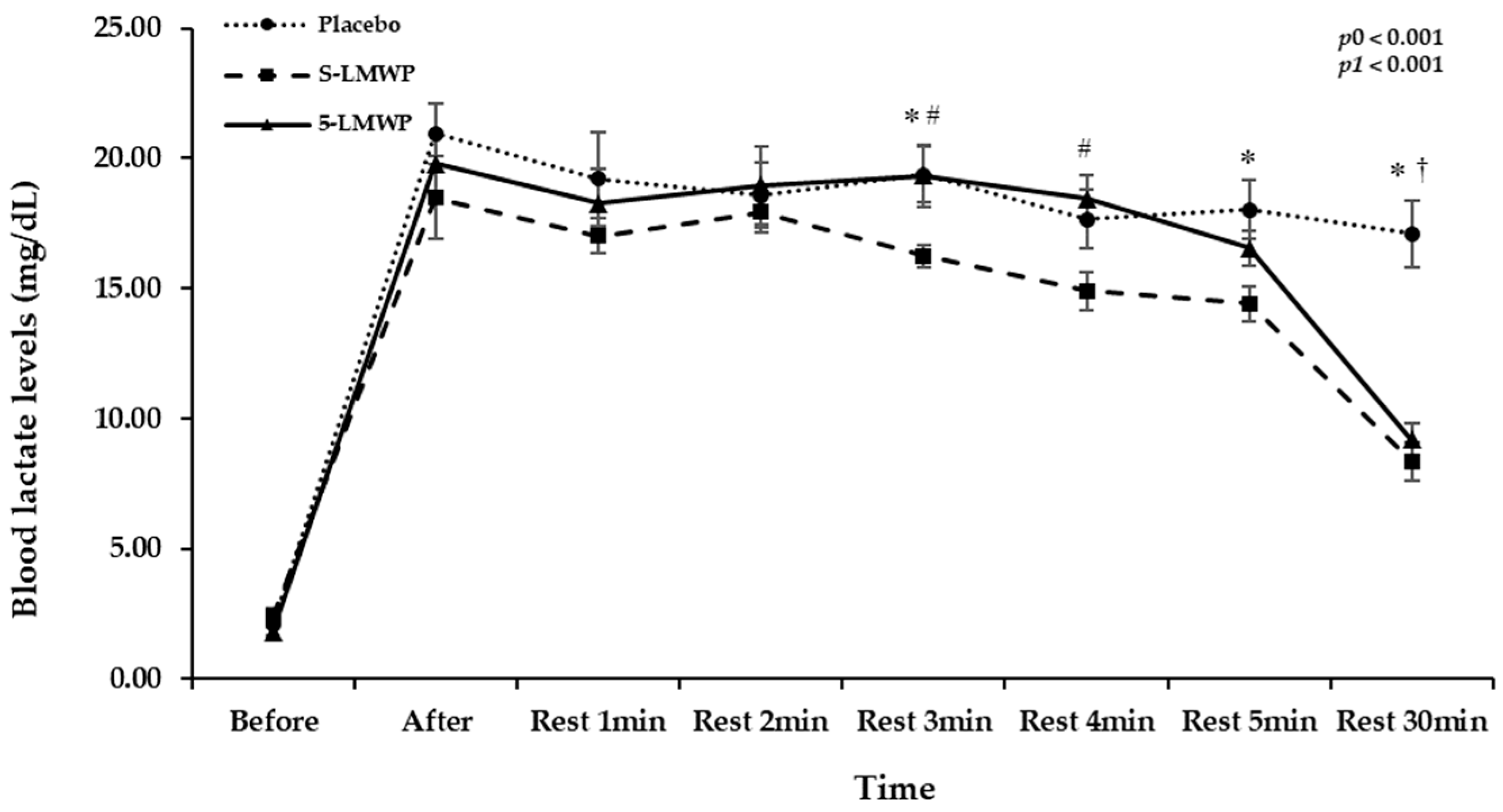

3.5. Comparison of Fatigue Metabolism and Oxidative Stress Related Markers Levels According to LMWP Consumption

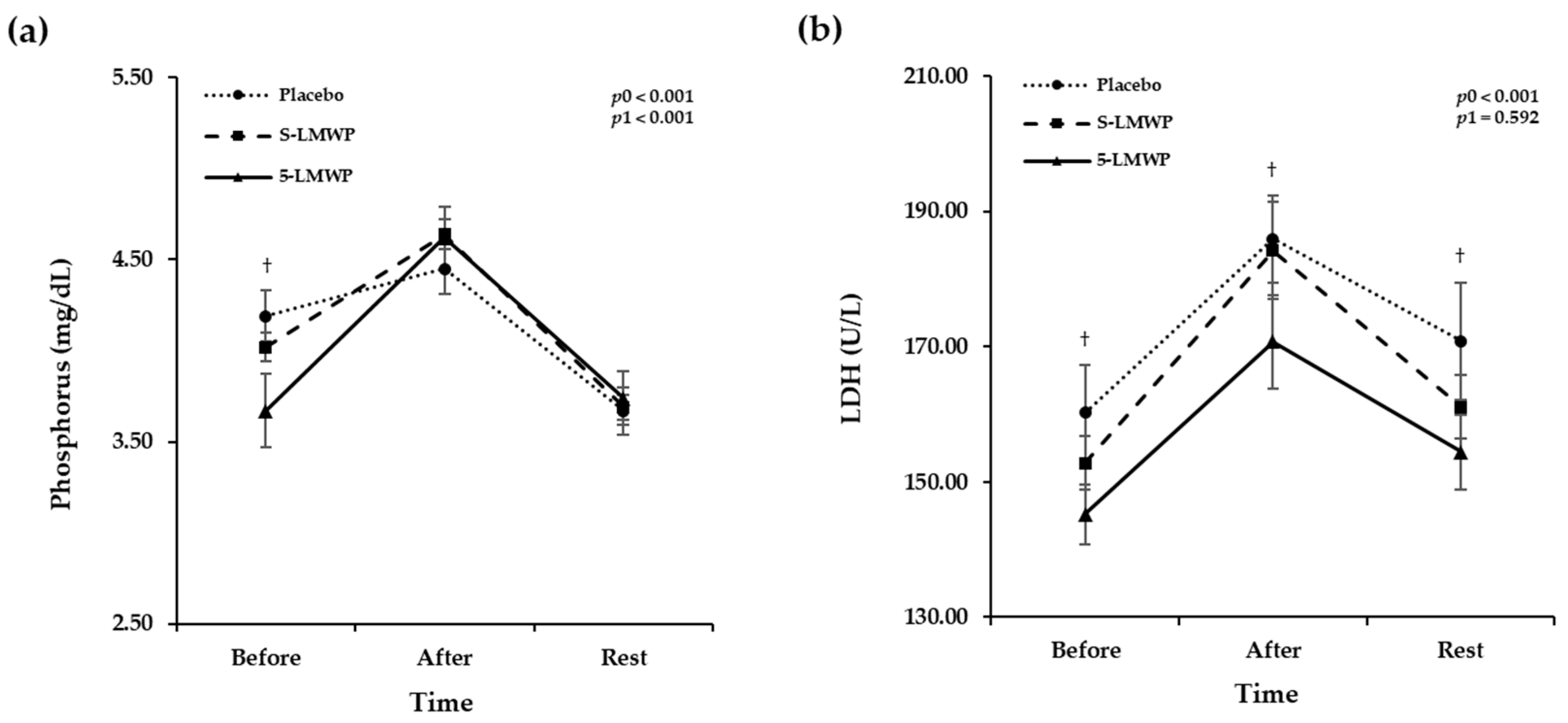

3.6. Changes of Phosphorus and LDH Levels According to LMWP Consumption

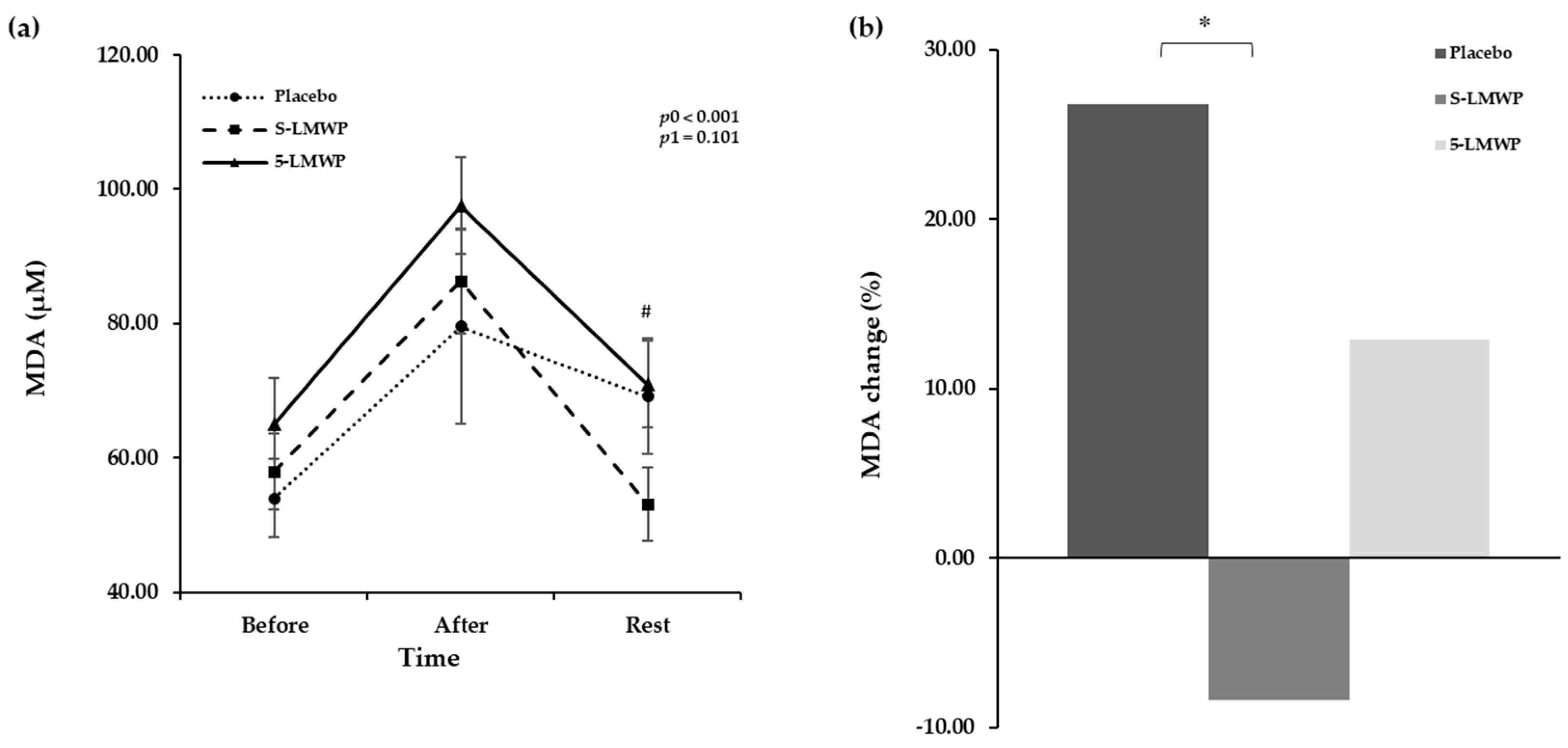

3.7. Changes of MDA Levels According to LMWP Consumption

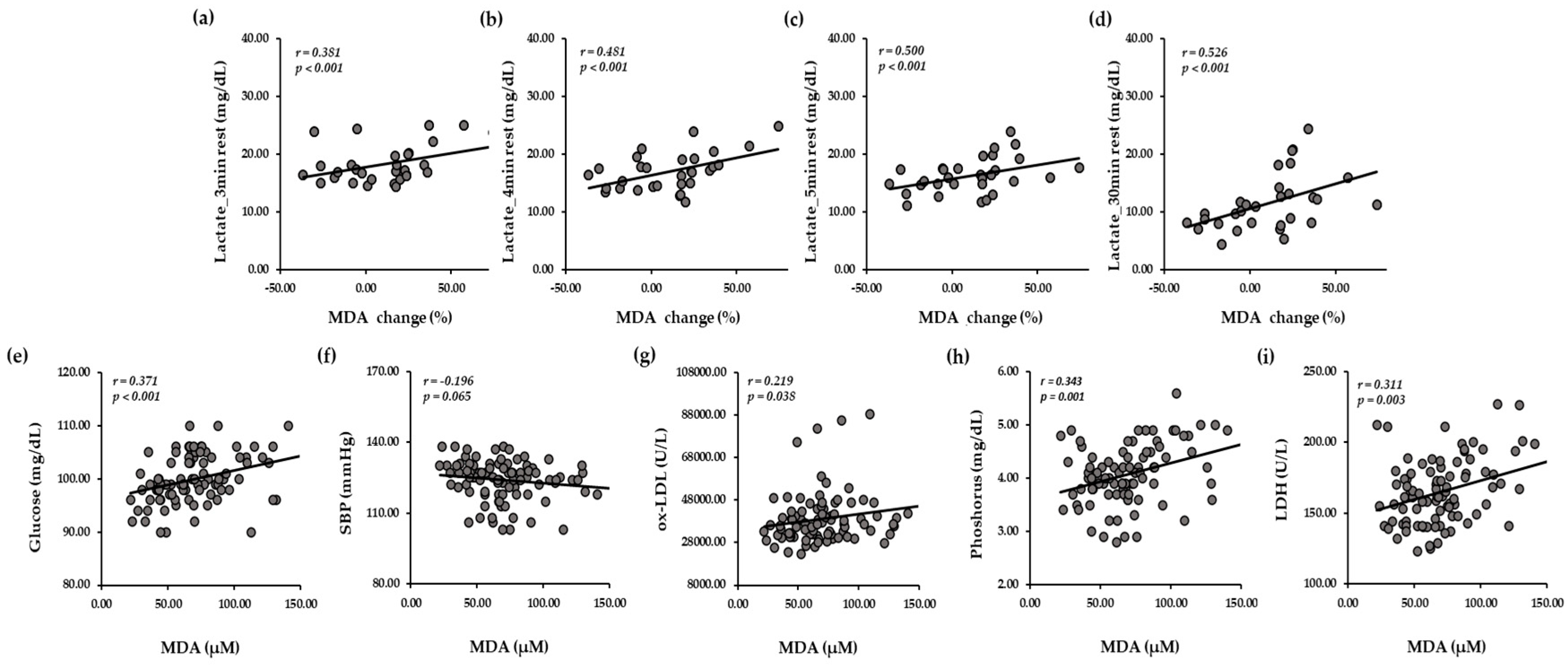

3.8. Relationships Between Oxidative Stress Related Markers and Biochemical Markers

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leeuwenburgh, C.; Heinecke, J.W. Oxidative stress and antioxidants in exercise. Curr Med Chem 2001, 8, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingitore, A.; Lima, G.P.; Mastorci, F.; Quinones, A.; Iervasi, G.; Vassalle, C. Exercise and oxidative stress: potential effects of antioxidant dietary strategies in sports. Nutrition 2015, 31, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Duarte, J.; Kavazis, A.N.; Talbert, E.E. Reactive oxygen species are signalling molecules for skeletal muscle adaptation. Exp Physiol 2010, 95, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simioni, C.; Zauli, G.; Martelli, A.M.; Vitale, M.; Sacchetti, G.; Gonelli, A.; Neri, L.M. Oxidative stress: role of physical exercise and antioxidant nutraceuticals in adulthood and aging. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 17181–17198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushchak, V.I. Free radicals, reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress and its classification. Chem Biol Interact 2014, 224, 164–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoi, W.; Naito, Y.; Takanami, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Sakuma, K.; Ichikawa, H.; Yoshida, N.; Yoshikawa, T. Oxidative stress and delayed -onset muscle damage after exercise. Free Radic Biol Med 2004, 37, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.F.; Reid, M.B. Muscle-derived ROS and thiol regulation in muscle fatigue. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2008, 104, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, I. Blood lactate. Implications for training and sports performance. Sports Med 1986, 3, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaap, A.J.; Shore, A.C.; Tooke, J.E. Relationship of insulin resistance to microvascular dysfunction in subjects with fasting hyperglycaemia. Diabetologia 1997, 40, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.L.Y.; Co, V.A.; El-Nezami, H. Dietary polyphenol impact on gut health and microbiota. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2021, 61, 690–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Tsatsakis, A.; Mamoulakis, C.; Teodoro, M.; Briguglio, G.; Caruso, E.; Tsoukalas, D.; Margina, D.; Dardiotis, E.; Kouretas, D.; et al. Current evidence on the effect of dietary polyphenols intake on chronic diseases. Food Chem Toxicol 2017, 110, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Colombo, F.; Biella, S.; Stockley, C.; Restani, P. Polyphenols and human health: the role of bioavailability. Nutrients 2021, 13, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowtell, J.; Kelly, V. Fruit-derived polyphenol supplementation for athlete recovery and performance. Sports Med 2019, 49 (Suppl. 1), 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cases, J.; Romain, C.; Marín-Pagán, C.; Chung, L.H.; Rubio-Pérez, J.M.; Laurent, C.; Gaillet, S.; Prost-Camus, E.; Prost, M.; Alcaraz, P.E. Supplementation with a polyphenol-rich extract, PerfLoadⓇ, improves physical performance during high-intensity exercise: a randomized, double blind, crossover trial. Nutrients 2017, 9, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, C.A.; Cook, M.D.; Willems, M.E. Effect of New Zealand blackcurrant extract on repeated cycling time trial performance. Sports (Basel) 2017, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Yoshitake, N.; Zhao, P.; Matsuo, Y.; Kouno, I.; Nonaka, G. Production of oligomeric proanthocyanidins by fragmentation of polymers. Jpn J Food Chem 2007, 14, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, H.; Nishioka, H.; Wakame, K.; Magnuson, B.A.; Roberts, A. Acute, subchronic and genotoxicity studies conducted with Oligonol, an oligomerized polyphenol formulated from lychee and green tea extracts. Food Chem Toxicol 2008, 46, 3553–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Noh, J.S.; Fujii, H.; Roh, S.S.; Song, Y.O.; Choi, J.S.; Chung, H.Y.; Yokozawa, T. Oligonol, a low-molecular-weight polyphenol derived from lychee fruit, attenuates gluco-lipotoxicity-mediated renal disorder in type 2 diabetic db/db mice. Drug Discov Ther 2015, 9, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, H.; Fujii, H.; Sun, B.; Aruoma, O.I. Comparative efficacy of oligonol, catechin and (−)-epigallo catechin 3-O-gallate in modulating the potassium bromate-induced renal toxicity in rats. Toxicology 2006, 226, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, H.Y.; Zhong, X.; Park, J.; Na, H.K.; Kim, N.; Lee, H.S.; Surh, Y.J. Oligonol inhibits dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis and colonic adenoma formation in mice. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013, 19, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Park, J.M.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Kangwan, N.; Han, Y.M.; Kang, E.A.; An, J.M.; Park, Y.K.; Hahm, K.B. Oligonol prevented the relapse of dextran sulfate sodium-ulcerative colitis through enhancing NRF2-mediated antioxidative defense mechanism. J Physiol Pharmacol 2018, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Bak, J.; Je, N.K.; Chung, H.Y.; Yokozawa, T.; Yoon, S.; Moon, J.Y. Oligonol ameliorates CCl4-induced liver injury in rats via the NF-Kappa B and MAPK signaling pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 3935841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.Y.; Maeda, T.; Fujii, H.; Yokozawa, T.; Kim, H.Y.; Cho, E.J.; Shibamoto, T. Oligonol improves memory and cognition under an amyloid β25-35-induced Alzheimer's mouse model. Nutr Res 2014, 34, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.B.; Shin, Y.O.; Min, Y.K.; Yang, H.M. The effect of oligonol intake on cortisol and related cytokines in healthy young men. Nutr Res Pract 2010, 4, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, A.; Hashimoto, S.; Suzuki, M.; Ueno, H.; Sugita, M. Oligomerized polyphenols in lychee fruit extract supplements may improve high-intensity exercise performance in male athletes: a pilot study. Phys Act Nutr 2021, 25, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, H.Y.; Hwang, J.Y.; Kwon, S.; Chung, H.R.; Kwak, T.K.; Kang, M.H.; Choi, Y.S. Development of nutrition quotient for Korean adults: item selection and validation of factor structure. J Nutr Health 2018, 51, 340–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yook, S.M.; Lim, Y.S.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, K.N.; Hwang, H.J.; Kwon, S.; Hwang, J.Y.; Kim, H.Y. Revision of Nutrition Quotient for Korean adults: NQ-2021. J Nutr Health 2022, 55, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalai, T.; Therasa, S.V.; Elumalai, E.K.; David, E. Intense and exhaustive exercise induce oxidative stress in skeletal muscle. Asian Pac J Trop Dis 2011, 1, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, O.Y.; Erukainure, O.l.; Ajiboye, J.A.; Adejobi, R.O.; Owolabi, F.O.; Kosoko, S.B. Modulatory effect of pineapple peel extract on lipid peroxidation, catalase activity and hepatic biomarker levels in blood plasma of alcohol-induced oxidative stressed rats. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2011, 1, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, H.M. Exercise-induced oxidative stress. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993, 25, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, D.; Williams, C.; McGregor, S.J.; Nicholas, C.W.; McArdle, F.; Jackson, M.J.; Powell, J.R. Prolonged vitamin C supplementation and recovery from demanding exercise. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2001, 11, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, T.; Muraoka, I. Exercise-Induced Oxidative Stress and the Effects of Antioxidant Intake from a Physiological Viewpoint. Antioxidants (Basel) 2018, 7, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S.K.; Smuder, A.J.; Kavazis, A.N.; Hudson, M.B. Experimental guidelines for studies designed to investigate the impact of antioxidant supplementation on exercise performance. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2010, 20, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.J.; Child, R.B.; Day, S.H.; Donnelly, A.E. Exercise-induced skeletal muscle damage and adaptation following repeated bouts of eccentric muscle contractions. J Sports Sci 1997, 15, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, D.S.; McFarlin, B.; Bois, C. Interleukin-6 expression after repeated bouts of eccentric exercise. Int J Sports Med 2003, 24, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foschini, D.; Prestes, J. Acute hormonal and immune responses after a bi-set strength training. Fit Perform J 2007, 6, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howatson, G.; McHugh, M.P.; Hill, J.A.; Brouner, J.; Jewell, A.P.; van Someren, K.A.; Shave, R.E.; Howatson, S.A. Influence of tart cherry juice on indices of recovery following marathon running. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010, 20, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, D.R.; Orange, T.; Gruber, M.T.; Darakjian, A.A.; Conway, K.L.; Hausenblas, H.A. Broad spectrum polyphenol supplementation from tart cherry extract on markers of recovery from intense resistance exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2021, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.C.; Lee, M.C.; Ho, C.S.; Hsu, Y.J.; Ho, C.C.; Kan, N.W. Protective and recovery effects of resveratrol supplementation on exercise performance and muscle damage following acute plyometric exercise. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona, G.; Roca, E.; Guerrero, M.; Cusso, R.; Barcena, C.; Mateu, M.; Cadefau, J.A. Fibre-type-specific and mitochondrial biomarkers of muscle damage after mountain races. Int J Sports Med 2019, 40, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.A.; Silva, E.T.; Caris, A.V.; Lira, F.S.; Tufik, S.; Dos Santos, R.V. Vitamin E supplementation inhibits muscle damage and inflammation after moderate exercise in hypoxia. J Hum Nutr Diet 2016, 29, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.K.; Hsieh, C.C.; Hsu, J.J.; Yang, Y.K.; Chou, H.N. Preventive effects of spirulina platensis on skeletal muscle damage under exercise-induced oxidative stress. Eur J Appl Physiol 2006, 98, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.J.; Zhao, M.M.; Regenstein, J.M.; Ren, J.Y. In vitro antioxidant activity and in vivo anti-fatigue effect of loach (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) peptides prepared by papain digestion. Food Chem 2011, 124, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.W.; Hahn, S.; Kim, J.J.; Yang, S.M.; Park, B.J.; Lee, S.C. Oligomerized lychee fruit extract (OLFE) and a mixture of vitamin C and vitamin E for endurance capacity in a double blind randomized controlled trial. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2012, 50, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovlin, R.; Cottle, W.; Pyke, I.; Kavanagh, M.; Belcastro, A.N. Are indices of free radical damage related to exercise intensity. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 1987, 56, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.J.; Quintanilha, A.T.; Brooks, G.A.; Packer, L. Free radicals and tissue damage produced by exercise. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1982, 107, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R.R. Exercise and oxidative stress methodology: a critique. Am J Clin Nutr 2000, 72, 670S–4S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, D.W.; Hessler, J.R.; Chisolm, G.M. Low density lipoprotein cytotoxicity induced by free radical peroxidation of lipid. J Lipid Res 1983, 24, 1070–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Mean | ± | SE | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 24.00 | ± | 0.52 | 22.00 | 27.00 |

| Height (cm) | 177.47 | ± | 1.87 | 166.70 | 188.10 |

| Weight (kg) | 80.32 | ± | 2.79 | 67.70 | 93.50 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.52 | ± | 0.81 | 23.50 | 30.00 |

| LBM (kg) | 61.34 | ± | 1.93 | 50.90 | 70.30 |

| SMM (kg) | 34.39 | ± | 1.10 | 28.50 | 39.80 |

| BFM (kg) | 18.98 | ± | 1.89 | 8.90 | 28.80 |

| BFP (%) | 23.37 | ± | 1.75 | 11.20 | 30.80 |

| NQ1 (balance) | 28.88 | ± | 4.45 | 3.93 | 47.00 |

| NQ2 (moderation) | 38.76 | ± | 3.17 | 25.90 | 53.90 |

| NQ3 (practice) | 58.82 | ± | 2.41 | 48.06 | 67.76 |

| NQ4 (total) | 43.82 | ± | 2.18 | 34.90 | 56.57 |

| Variables | Placebo | S-LMWP | 5-LMWP | p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 80.32 | ± | 2.79ab | 80.87 | ± | 3.01a | 80.35 | ± | 2.98b | 0.125 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.52 | ± | 0.81ab | 25.80 | ± | 0.85a | 25.57 | ± | 0.86b | 0.124 |

| LBM (kg) | 61.34 | ± | 1.93 | 62.23 | ± | 2.01 | 61.66 | ± | 1.89 | 0.452 |

| SMM (kg) | 34.39 | ± | 1.10 | 34.91 | ± | 1.14 | 34.59 | ± | 1.07 | 0.452 |

| BFM (kg) | 18.98 | ± | 1.89a | 18.64 | ± | 1.92b | 18.69 | ± | 2.00ab | 0.358 |

| BFP (%) | 23.37 | ± | 1.75a | 22.78 | ± | 1.71b | 22.94 | ± | 1.07ab | 0.031 |

| Variables | Placebo | S-LMWP | 5-LMWP | p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VO2max (ml/kg/min) | 47.29 | ± | 1.39 | 47.85 | ± | 1.63 | 47.06 | ± | 1.41 | 0.273 |

| HRmax (bpm) | 190.80 | ± | 2.21ab | 189.30 | ± | 1.92b | 193.00 | ± | 1.61a | 0.006 |

| ET (sec) | 736.00 | ± | 12.49 | 741.50 | ± | 18.80 | 755.50 | ± | 16.37 | 0.085 |

| AT (sec) | 502.50 | ± | 19.99 | 508.00 | ± | 23.43 | 486.50 | ± | 21.20 | 0.132 |

| GL (kg) | 43.41 | ± | 1.25a | 41.21 | ± | 1.32b | 40.22 | ± | 0.88b | 0.003 |

| GR (kg) | 45.87 | ± | 1.93a | 43.77 | ± | 2.23b | 42.87 | ± | 2.13b | 0.061 |

| BMS (kg) | 152.45 | ± | 5.94 | 143.60 | ± | 6.26 | 146.00 | ± | 8.21 | 0.122 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 98.40 | ± | 1.07 | 99.80 | ± | 1.82 | 101.60 | ± | 1.31 | 0.256 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 129.10 | ± | 1.57a | 122.40 | ± | 3.21ab | 120.20 | ± | 2.47b | 0.014 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 80.50 | ± | 3.46a | 73.70 | ± | 2.24b | 73.40 | ± | 1.78b | 0.199 |

| Time | Placebo | S-LMWP | 5-LMWP | p0 | p1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise | <0.001 | 0.293 | |||||||||

| Before | 65.60 | ± | 2.57 | 62.70 | ± | 1.78 | 63.40 | ± | 1.63 | ||

| After | 191.30 | ± | 2.07 | 189.30 | ± | 1.92 | 192.00 | ± | 1.50 | ||

| Rest | |||||||||||

| 1 min | 116.30 | ± | 4.97b | 123.70 | ± | 1.97ab | 130.80 | ± | 3.97a | ||

| 2 min | 111.90 | ± | 4.57b | 117.10 | ± | 2.12ab | 120.50 | ± | 3.22a | ||

| 3 min | 108.90 | ± | 5.69 | 111.10 | ± | 1.68 | 115.00 | ± | 2.80 | ||

| 4 min | 113.40 | ± | 3.31 | 110.20 | ± | 2.16 | 115.70 | ± | 2.53 | ||

| 5 min | 110.60 | ± | 3.04ab | 107.00 | ± | 2.03b | 113.50 | ± | 1.95a | ||

| 30 min | 96.50 | ± | 3.84 | 96.10 | ± | 3.47 | 102.10 | ± | 2.61 | ||

| Variables | Placebo | S-LMWP | 5-LMWP | p0 | p1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UA (mg/dL) | Before | 6.71 | ± | 0.27 | 6.57 | ± | 0.16 | 6.50 | ± | 0.23 | <0.001 | 0.089 |

| After | 6.56 | ± | 0.26 | 6.60 | ± | 0.19 | 6.56 | ± | 0.23 | |||

| Rest | 8.37 | ± | 0.34a | 7.85 | ± | 0.31b | 8.27 | ± | 0.33ab | |||

| CK (U/L) |

Before | 153.60 | ± | 18.41b | 203.00 | ± | 32.40a | 139.80 | ± | 11.70ab | <0.001 | 0.008 |

| After | 178.10 | ± | 21.66b | 238.40 | ± | 39.26a | 167.20 | ± | 14.73b | |||

| Rest | 163.20 | ± | 19.53b | 211.20 | ± | 33.77a | 152.40 | ± | 12.73ab | |||

| CK-MB (ng/dL) |

Before | 1.64 | ± | 0.20 | 1.48 | ± | 0.14 | 1.43 | ± | 0.16 | <0.001 | 0.139 |

| After | 1.89 | ± | 0.24 | 1.74 | ± | 0.17 | 1.71 | ± | 0.20 | |||

| Rest | 1.70 | ± | 0.20 | 1.57 | ± | 0.16 | 1.58 | ± | 0.17 | |||

| ox-LDL (mU/L) | Before | 35985.37 | ± | 2515.65 | 35152.11 | ± | 2672.22 | 34060.01 | ± | 3167.76 | <0.001 | 0.250 |

| After | 44276.02 | ± | 4940.21 | 42444.66 | ± | 2452.35 | 43410.29 | ± | 5461.12 | |||

| Rest | 40597.81 | ± | 4153.36 | 36440.74 | ± | 2478.22 | 40847.47 | ± | 4772.95 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.