1. Introduction: Parallel Innovations, Divergent Trajectories

The historiography of Cold War computing often presents a unidirectional narrative: Western technological superiority versus Soviet imitation epitomized by the Ryad series’ cloning of IBM 360 architecture [

8]. Yet this framing obscures a more complex reality of

parallel innovation—instances where similar mathematical techniques emerged independently on both sides of the Iron Curtain, shaped by radically different material and institutional contexts.

This article examines one such case: the development of

operator splitting methods for solving multidimensional partial differential equations (PDEs). In the United States, Donald W. Peaceman and Henry H. Rachford Jr. at Humble Oil published their Alternating Direction Implicit (ADI) method in 1955 [

1], followed by Jim Douglas and Rachford’s generalization in 1956 [

2]. Independently, Soviet mathematicians at Novosibirsk—particularly Nikolai N. Yanenko—developed analogous

fractional steps methods formalized in Yanenko’s 1967 monograph [

3].

1.1. Research Questions and Thesis

This study addresses three interconnected questions:

Parallel discovery: How did similar decomposition techniques emerge in different scientific communities?

Material and epistemic constraints: To what extent did Soviet hardware limitations interact with pre-existing Soviet mathematical traditions to shape algorithmic priorities?

Geographic specificity: What role did Akademgorodok’s unique institutional structure play in fostering a distinct “Novosibirsk school”?

Central thesis: While the mathematical core of splitting methods was discovered independently in East and West, the Soviet trajectory—driven by acute resource scarcity and deep epistemological preference for operator-theoretic elegance—produced a more systematic theoretical framework emphasizing computational economy.

1.2. Methodological Approach and Source Limitations

This study synthesizes:

Technical publications: Primary mathematical texts (Yanenko 1967, Marchuk 1975, Samarskii 1964) and Western counterparts

Secondary historiography: Works on Soviet cybernetics [

8], Akademgorodok sociology [

9,

10]

Archival materials: Limited access to Siberian Branch of RAS archives (SO RAN, Funds 14 and 28)

Critical limitations: Access to classified TsAGI reports remains restricted. Claims about industrial applications rely on secondary sources rather than primary computational reports.

2. The Memory Wall and the Curse of Dimensionality

2.1. Comparative Hardware Landscape (c. 1965)

By the mid-1960s, scientific computing bifurcated along geopolitical lines, with profound implications for algorithmic development.

Table 1.

Leading Scientific Computers: Comparative Specifications (c. 1967).

Table 1.

Leading Scientific Computers: Comparative Specifications (c. 1967).

| Feature |

BESM-6 (USSR) |

CDC 6600 (USA) |

| Architecture |

48-bit words |

60-bit words |

| Main Memory |

32,768 words (∼192 KB) |

131,072 words (∼983 KB) |

| Performance |

∼1 MFLOPS |

3–10 MFLOPS |

| Clock Speed |

∼1 MHz |

10 MHz |

| Secondary Storage |

Magnetic drums (512 KB) |

Disk drives (6.6 MB) |

| Cooling |

Air-cooled |

Freon-cooled |

| Power Consumption |

∼30 kW |

∼150 kW |

| Production Run |

∼355 units (1968–1987) |

∼100 units (1964–1969) |

The memory disparity was the critical bottleneck. While Western engineers could increasingly rely on expanding RAM, Soviet researchers faced a persistent ceiling that remained unchanged through multiple BESM generations.

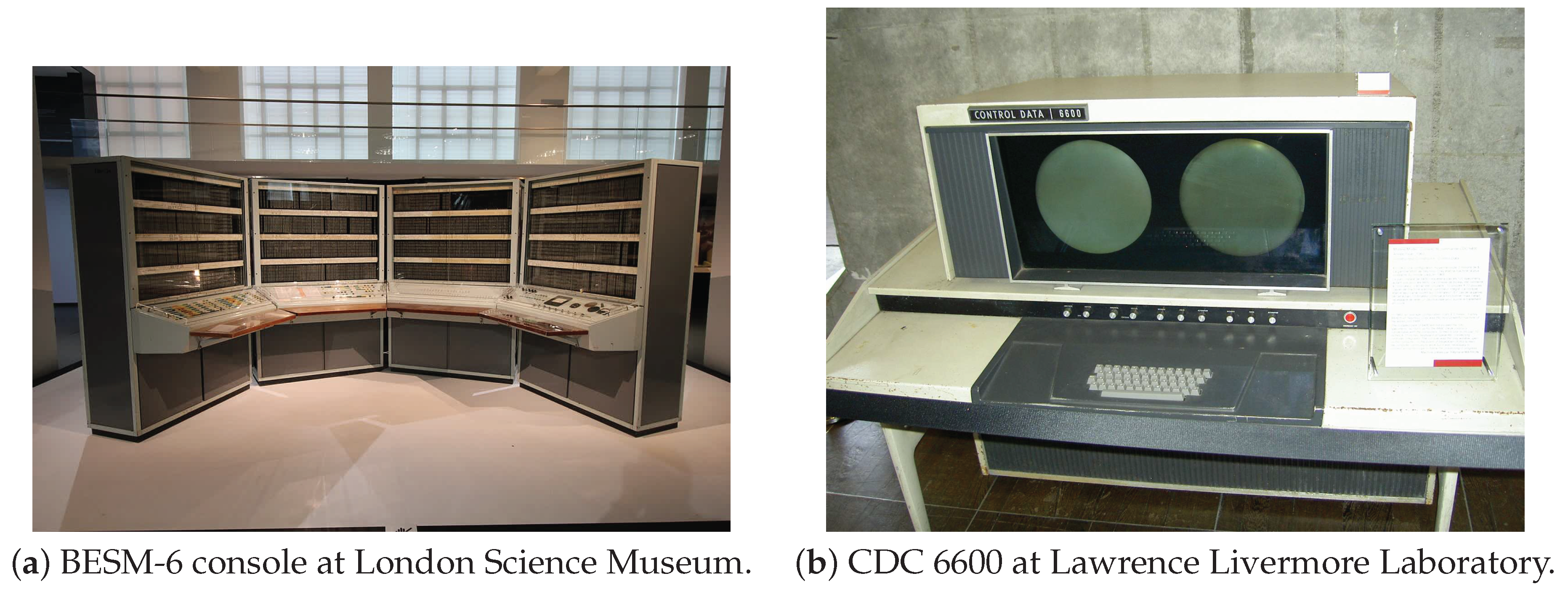

Figure 1.

The hardware divide: Soviet BESM-6 versus American CDC 6600.

Figure 1.

The hardware divide: Soviet BESM-6 versus American CDC 6600.

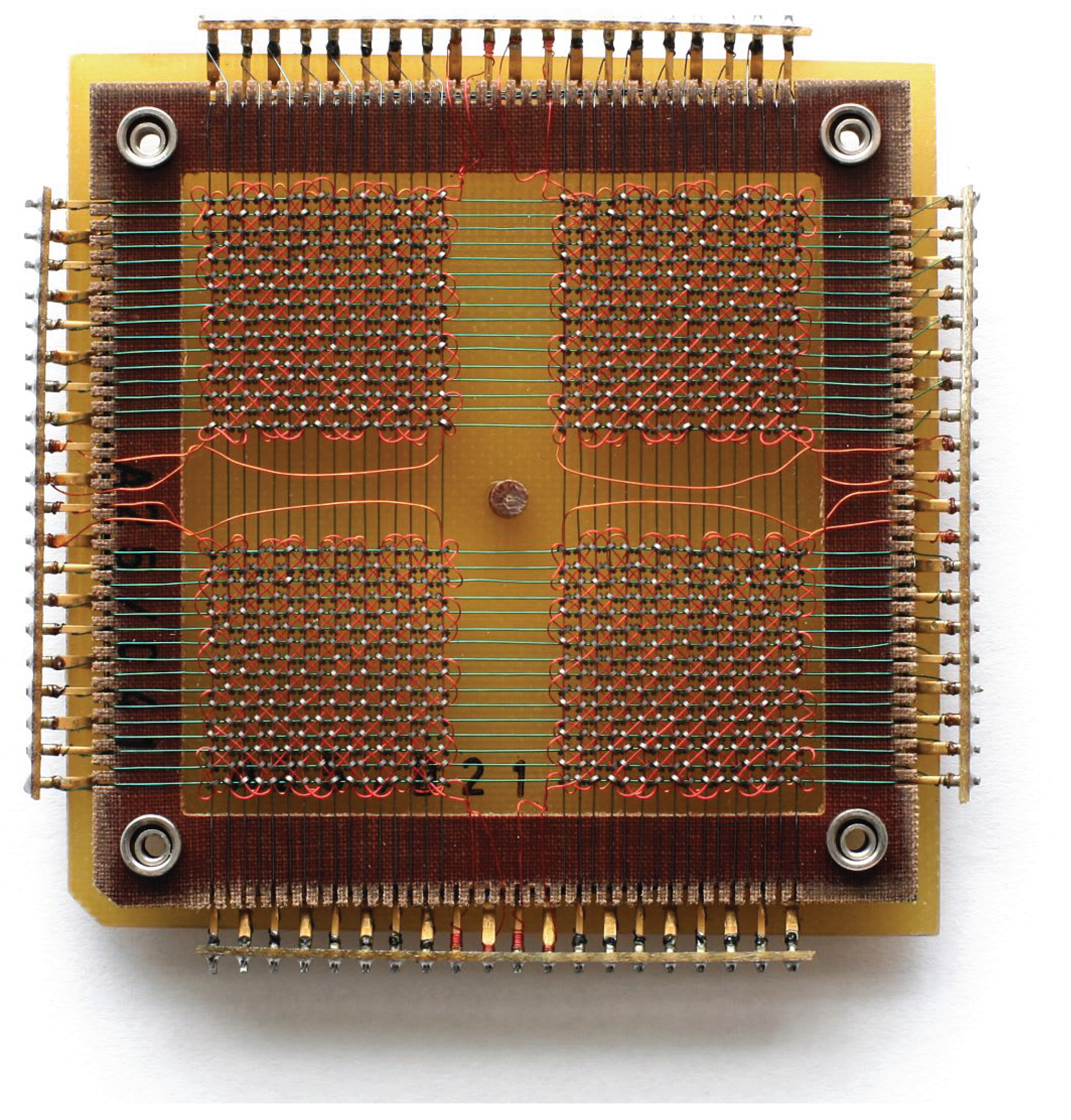

Figure 2.

Magnetic core memory plane (close-up). Each ferrite ring stores one bit. BESM-6 contained 1,536,000 individual cores hand-woven primarily by female technicians at Moscow plants.

Figure 2.

Magnetic core memory plane (close-up). Each ferrite ring stores one bit. BESM-6 contained 1,536,000 individual cores hand-woven primarily by female technicians at Moscow plants.

2.2. The Implicit Scheme Dilemma

Consider the canonical heat equation in three spatial dimensions:

Discretization on a modest grid yields unknowns. Two traditional approaches existed:

Explicit schemes (von Neumann, 1944): Require tiny time steps (CFL condition) to maintain stability, rendering long-time integration prohibitively expensive.

Implicit schemes (Crank-Nicolson, 1947): Unconditionally stable for large , but require solving a linear system at each time step. For 3D problems:

Matrix size: (for : )

Sparse storage (7-point stencil): words ≈ 56 MB

BESM-6 capacity: 0.192 MB⇒300:1 memory deficit

Even with tape/drum swapping, the computational overhead made 3D implicit schemes impractical on Soviet hardware.

3. The Genesis of Splitting: Western Origins and Soviet Reformulation

3.1. The Peaceman-Rachford Breakthrough (1955)

The first systematic solution to the 3D implicit dilemma came not from academia but from industrial petroleum engineering. Donald W. Peaceman and Henry H. Rachford Jr., working at Humble Oil Company, needed to simulate subsurface fluid flow in heterogeneous porous media [

1].

Their

Alternating Direction Implicit (ADI) method proposed:

Each sub-step requires solving only a tridiagonal system along one direction—a dramatic reduction in computational complexity.

Douglas-Rachford extension (1956): Jim Douglas and Rachford generalized ADI to 3D and proved second-order accuracy [

2], establishing the method’s mathematical rigor.

3.2. Independent Soviet Development (1957–1967)

Soviet awareness of Peaceman-Rachford appears limited until the late 1960s. Early Russian work on directional decomposition includes:

Samarskii (1957–1960): “Locally one-dimensional” schemes for parabolic equations. First citation of Peaceman-Rachford appears in his 1964 review article [

5], treating it as parallel development rather than acknowledged precursor.

Marchuk (1962): Application of splitting to atmospheric modeling [

4].

This delay in Western awareness reflects language barriers, institutional isolation, and different application domains.

Yanenko’s contribution was systematic

theoretical unification under the umbrella of “fractional steps,” published in his 1967 monograph [

3].

3.3. Mathematical Equivalence and Conceptual Divergence

While mathematically analogous, the Western ADI and Soviet fractional steps traditions diverged in:

Table 2.

Comparative Philosophies: ADI vs. Fractional Steps.

Table 2.

Comparative Philosophies: ADI vs. Fractional Steps.

| Aspect |

Western ADI |

Soviet Fractional Steps |

| Primary goal |

Accuracy (O()) |

Computational economy |

| Theoretical emphasis |

Convergence proofs |

Operator theory generality |

| Application driver |

Petroleum engineering |

Military aerodynamics |

| Institutional context |

Industrial R&D (Humble Oil) |

State-sponsored academic institutes |

| Publications |

SIAM journals, specialized |

Comprehensive monographs (Yanenko 1967) |

The Soviet approach developed into a philosophical framework—viewing splitting as a universal strategy for managing complexity under resource constraints, not merely an algorithmic trick.

4. The Novosibirsk Formalization

4.1. Yanenko’s Operator-Theoretic Framework

N.N. Yanenko’s 1967 monograph

The Method of Fractional Steps [

3] systematized splitting via abstract operator theory. For an evolution equation:

Yanenko proposed approximating the evolution operator

via product formula:

This abstraction enabled systematic analysis of consistency, stability, and conservation properties.

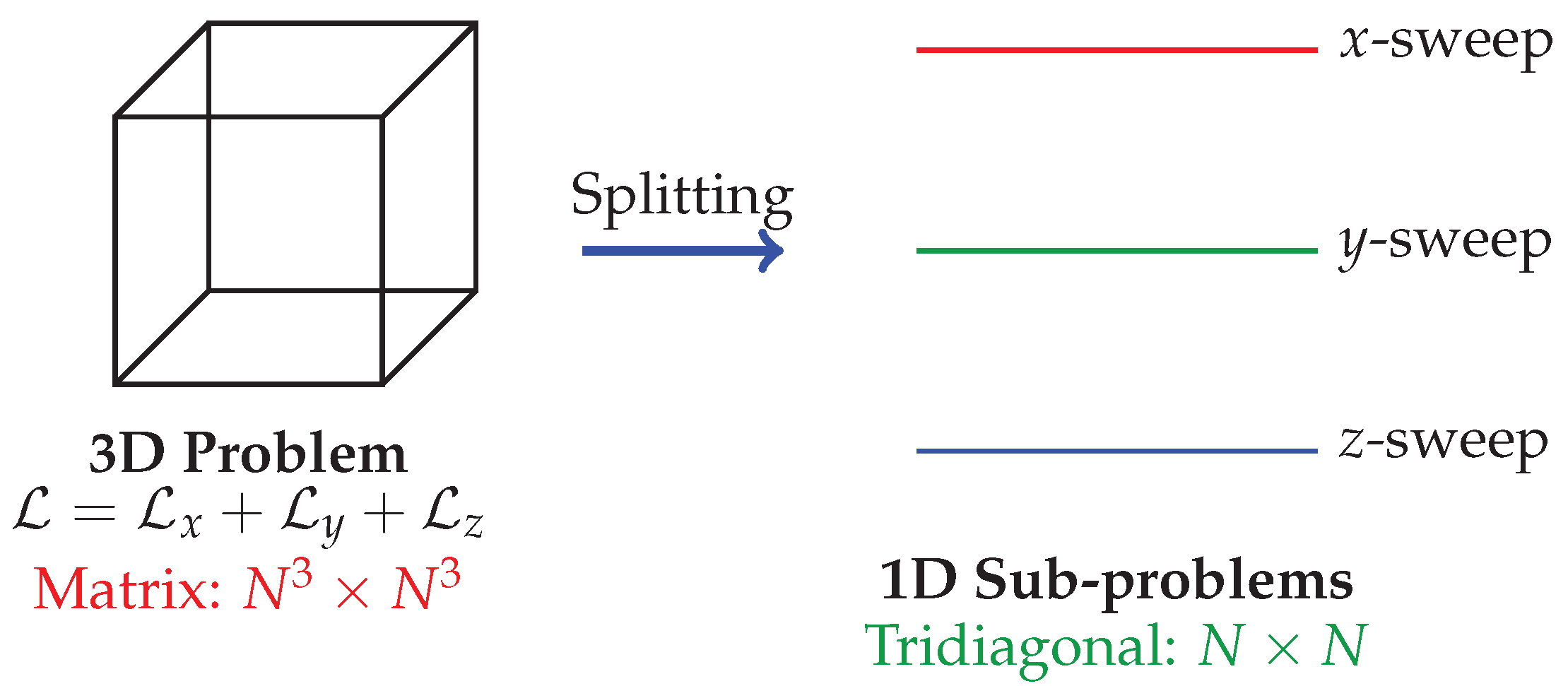

Figure 3.

Operator splitting concept: 3D operator decomposed into three sequential 1D operators.

Figure 3.

Operator splitting concept: 3D operator decomposed into three sequential 1D operators.

4.2. The Progonka Algorithm: Soviet Standardization

The computational payoff of splitting hinged on efficient solution of tridiagonal systems. The Tridiagonal Matrix Algorithm (TDMA), known in the West as the Thomas algorithm (1949), was available. Its adoption in Soviet science was distinct in its universality [

5].

Renamed and standardized as the Progonka method (literally “chase” or “sweep”), it was not merely an available subroutine but a pedagogical cornerstone. Unlike in the West, where TDMA was one option among many, Soviet university curricula prioritized Progonka as the fundamental building block of efficient computing, creating a generation of programmers culturally conditioned to seek solutions.

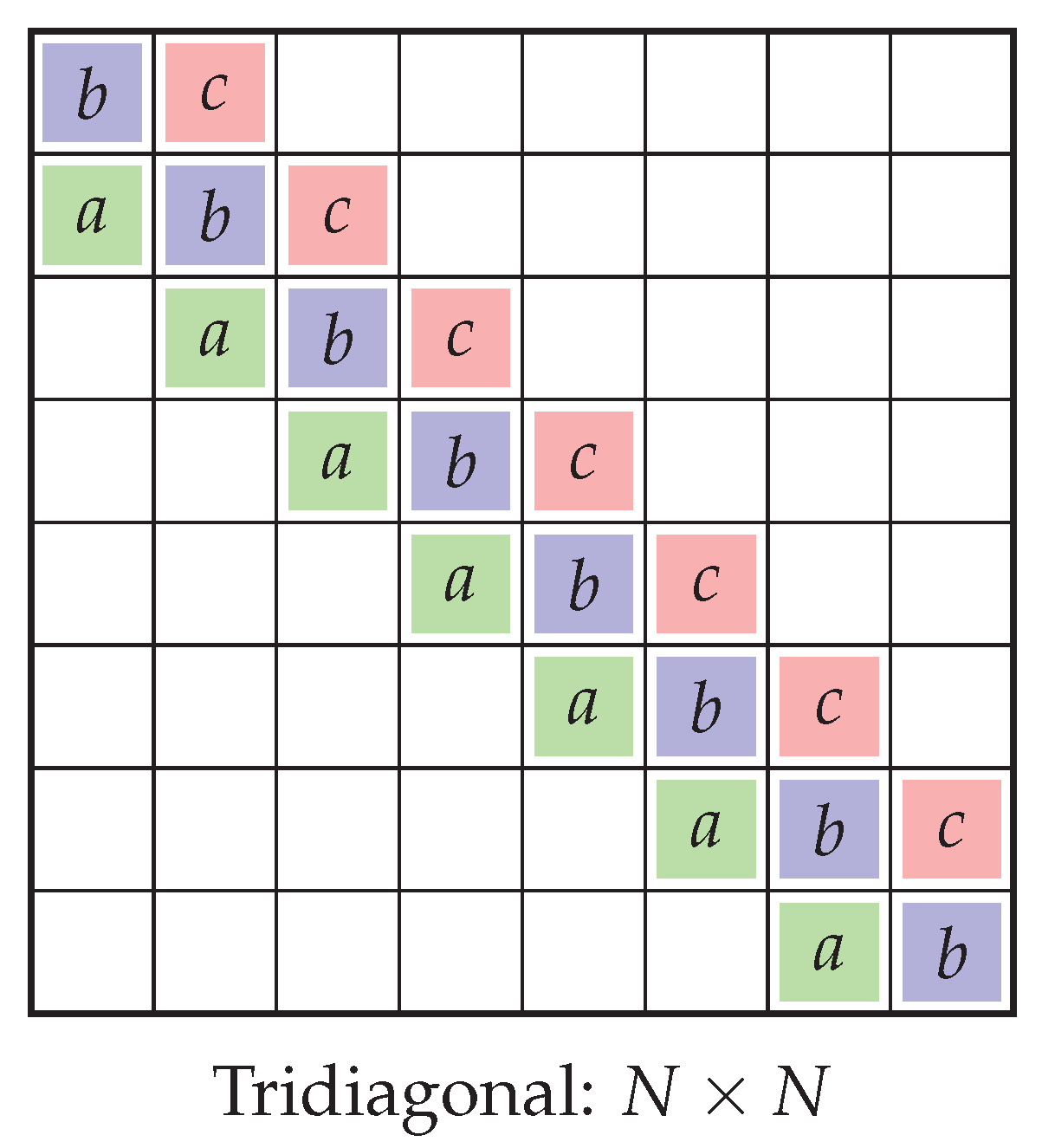

Figure 4.

Tridiagonal matrix structure. Only 3 diagonals are non-zero.

Figure 4.

Tridiagonal matrix structure. Only 3 diagonals are non-zero.

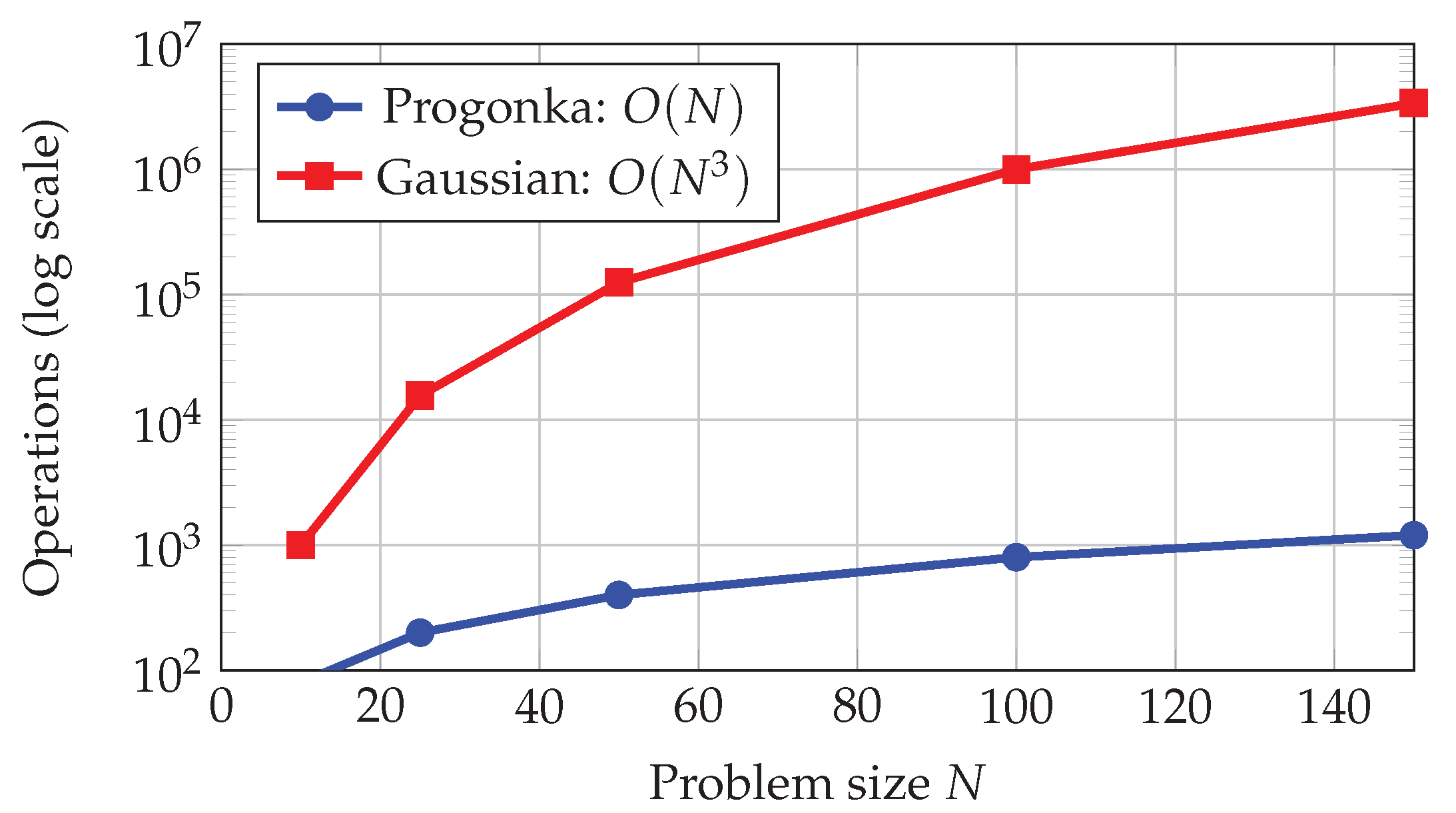

Complexity advantage:

Operations: FLOPs (linear)

Memory: 5 vectors of length N

For : 10,000x speedup versus naive Gaussian elimination

Figure 5.

Computational complexity comparison: Progonka/Thomas algorithm scales linearly.

Figure 5.

Computational complexity comparison: Progonka/Thomas algorithm scales linearly.

This standardization—codified in textbooks and widely taught in Soviet universities—created a shared computational culture emphasizing algorithmic efficiency.

5. Geography of Innovation: The Akademgorodok Context

5.1. Institutional Architecture and Interdisciplinarity

Akademgorodok’s physical layout was designed to counteract Moscow’s disciplinary silos [

10]. Key features shaping the fractional steps research program:

Figure 6.

Aerial view of Akademgorodok, Novosibirsk, late 1960s. Founded in 1957 by M.A. Lavrentyev, this “Science City” housed 35+ research institutes in close spatial proximity. The Computing Centre (center-right) was adjacent to Institutes of Hydrodynamics, Nuclear Physics, and Theoretical Mechanics, fostering rapid interdisciplinary feedback loops.

Figure 6.

Aerial view of Akademgorodok, Novosibirsk, late 1960s. Founded in 1957 by M.A. Lavrentyev, this “Science City” housed 35+ research institutes in close spatial proximity. The Computing Centre (center-right) was adjacent to Institutes of Hydrodynamics, Nuclear Physics, and Theoretical Mechanics, fostering rapid interdisciplinary feedback loops.

Spatial proximity: 500-meter walking distance between Computing Centre and hydrodynamics/physics institutes

Unified administration: Siberian Branch (SO AN SSSR) enabled flexible resource allocation

Military-industrial urgency: Closed cities (Chelyabinsk-40/70, Arzamas-16) demanded practical solutions

Computational rationing: Limited BESM-6 access (shared across 35 institutes) incentivized efficient algorithms

This created a feedback loop: physicists/engineers posed urgent problems → mathematicians developed efficient methods → rapid implementation testing → refinement.

5.2. Epistemological Foundations: Soviet Mathematical Culture

This trajectory was not solely dictated by hardware scarcity. It also reflected a deeper epistemological preference within the Soviet mathematical physics tradition. This culture, fostered by the rigorous standards of the S.L. Sobolev school in Novosibirsk, is exemplified by the seminal textbooks of S.K. Godunov and V.S. Ryabenkii, which prioritized the development of a unified “theory of difference schemes” [

14] over ad-hoc empirical solutions.

This tradition valued general operator theory and analytical elegance—a preference well-documented in the historiography of Soviet cybernetics [

8,

11]—over the direct heuristic discretizations often favored in American industrial R&D. The hardware constraints of the BESM-6 thus acted as a selection pressure—not a creative force, but a catalyst that reinforced a pre-existing cultural preference for sophisticated, theoretically robust algorithms.

5.3. Yanenko’s Biography: From Nuclear Weapons to Numerical Methods

Nikolai Nikolaevich Yanenko (1921–1984) epitomized the Soviet scientific-military complex:

1940s: Nuclear weapons program (Chelyabinsk-70)

1950s: Transition to academic research, focus on gas dynamics

1960s: Novosibirsk Computing Centre, systematization of splitting methods

1967: Publication of defining monograph [

3]

His trajectory illustrates the Soviet pattern: weapons scientists transitioning to theoretical work while maintaining applied focus. Unlike Western pure mathematicians (e.g., Strang at MIT), Yanenko remained embedded in industrial problem-solving.

5.4. The Labor of Implementation: Invisible Work

The feminization of the Soviet programming workforce is well-established in general historiography [

8,

9], yet the specific demographic composition of the Novosibirsk Computing Centre remains obscured by restricted personnel archives (Fund 28).

However, the implementation of fractional steps on the BESM-6 required meticulous optimization in Autocode assembly—labor-intensive work that disproportionately fell to female technicians and junior programmers. Acknowledging this invisible labor is essential, even if specific attributions remain inaccessible pending archival declassification.

6. Applications and Contemporary Legacy

6.1. Industrial Applications: Confirmed and Probable Scenarios

Atmospheric modeling (Confirmed) This remains the best-documented application. Marchuk’s global circulation models at the Computing Centre explicitly utilized fractional steps for advection-diffusion equations, enabling Soviet weather forecasting to maintain parity with Western capabilities despite hardware lags [

4].

Thermal analysis (Soyuz program) Engineering memoirs [

13] confirm the use of numerical modeling for ablative heat shield design. The physics of heat conduction in composite materials is mathematically consistent with the splitting schemes Yanenko advocated, though specific code listings remain classified.

Supersonic aerodynamics (MiG-25/Su-27) Caution is required to avoid anachronistic projections of modern CFD. Unlike thermal analysis, full 3D aerodynamic simulation was beyond the BESM-6’s effective capacity. It is historically probable that splitting methods served primarily as post-facto validation tools for specific shock-wave interactions where wind tunnel data was ambiguous, rather than as drivers of initial airframe design.

6.2. The French Connection: Validated Intellectual Transfer

Historiography on Franco-Soviet mathematical exchange is well-documented [

12]:

1968: French translation of Yanenko’s monograph (Méthode à pas fractionnaires, Armand Colin)

1969–1975: Lions-Marchuk collaboration, bilateral colloquia

1970s: Integration into French numerical analysis curriculum (École Polytechnique, INRIA)

J.-L. Lions and R. Temam’s rigorous convergence proofs [

6] provided mathematical validation for methods Soviets used pragmatically, creating a synthesis of Soviet efficiency and Western rigor.

6.3. Modern Legacy: Parallelism from Scarcity

The ironic reversal: methods designed for memory-constrained single CPUs (BESM-6) became optimal for massively parallel architectures (2000s+):

Directional decoupling:x-sweeps across all planes can be computed independently ⇒ perfect parallelization

Minimal communication: Only boundary data exchanged between processors

Scalability: PISO/SIMPLE solvers in OpenFOAM, ANSYS Fluent scale to 100,000+ cores

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study’s conclusions are constrained by several methodological limitations:

7.1. Archival Access

TsAGI classified reports: Aerodynamic computation details remain restricted

SO RAN incomplete cataloging: Computing Centre archives (Fund 28) partially inventoried

Personnel records: Privacy restrictions prevent demographic analysis of programming staff

7.2. Language and Translation

Russian technical literature from 1955–1970 remains under-translated. Systematic review of Zhurnal Vychislitelnoi Matematiki i Matematicheskoi Fiziki could reveal earlier splitting method developments predating Yanenko’s 1967 synthesis.

7.3. Comparative Industrial Analysis

Claims about Soviet computational aerodynamics require detailed comparisons with contemporary Western CFD codes, benchmarking data, and engineering workflow documentation.

7.4. Gender and Labor

Definitive statements about women programmers at Novosibirsk require personnel archives, oral history interviews, and internal Computing Centre reports.

8. Conclusion: Algorithmic Resilience and Historical Contingency

This study examined the development of operator splitting methods through the lens of Soviet material constraints, epistemological commitments, and institutional structures. Three conclusions emerge:

1. Parallel innovation with divergent epistemologies. The mathematical core of splitting (Peaceman-Rachford 1955, Yanenko 1967) emerged independently, challenging narratives of unidirectional technological transfer. Yet institutional contexts and intellectual traditions shaped distinct emphases: Western focus on accuracy/convergence versus Soviet focus on computational economy and operator-theoretic elegance.

2. Material constraint as selective pressure, not creative force. Akademgorodok’s spatial organization and military-industrial urgency created a research environment favoring practical algorithms. The pre-existing Soviet mathematical tradition valorizing theoretical generality acted as a selection filter, ensuring pragmatic algorithmic solutions were clothed in sophisticated operator-theoretic language. This conjunction was rare and consequential.

3. The paradox of constraint-driven innovation. Methods designed to circumvent BESM-6’s 192 KB memory limitation—a severe handicap in the 1960s—became optimal for 21st-century massively parallel supercomputers. This suggests scarcity-driven optimization can produce robust, transferable solutions outlasting their original hardware context.

Broader implications: Soviet mathematical and computational approaches contributed substantially to the analytical resilience of Soviet aerospace engineering, enabling competitive performance by validating critical experimental data despite inferior hardware. In an era of computationally intensive AI models consuming megawatt-hours, the Soviet experience offers a counterpoint: algorithmic elegance and resource efficiency as strategic assets.

Final caveat: This narrative risks romanticizing constraint. Soviet computing also suffered from systemic inefficiencies, bureaucratic rigidity, and brain drain. The success of fractional steps was exceptional, not representative. A balanced historiography must account for both brilliance and dysfunction.

The author is an independent researcher.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Data Availability Statement

Archival references (SO RAN Funds 14, 28) and bibliographic sources are cited throughout.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the archival staff of SO RAN (Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences) for partial access to historical materials. Photographic materials courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and SO RAN historical archives.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no competing financial or non-financial interests.

References

- Peaceman, D.W., & Rachford, H.H. (1955). The Numerical Solution of Parabolic and Elliptic Differential Equations. Journal of the Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 3(1), 28–41. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J., & Rachford, H.H. (1956). On the Numerical Solution of Heat Conduction Problems in Two and Three Space Variables. Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 82(2), 421–439. [CrossRef]

- Yanenko, N.N. (1967). Metod drobnykh shagov resheniya mnogomernykh zadach matematicheskoj fiziki. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Marchuk, G.I. (1975). Methods of Numerical Mathematics. New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Samarskii, A.A. (1964). Local one-dimensional difference schemes for multi-dimensional hyperbolic equations. USSR Computational Mathematics and Mathematical Physics, 4(4), 21–35. [CrossRef]

- Lions, J.-L., & Temam, R. (1969). Éclatement et décentralisation en calcul des variations. Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées, 48, 45–82.

- Strang, G. (1968). On the Construction and Comparison of Difference Schemes. SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis, 5(3), 506–517. [CrossRef]

- Gerovitch, S. (2002). From Newspeak to Cyberspeak: A History of Soviet Cybernetics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Tatarchenko, K. (2013). The Computer for the 21st Century? In N. Oreskes & J. Krige (Eds.), Science and Technology in the Global Cold War (pp. 263–298).

- Josephson, P.R. (1997). New Atlantis Revisited: Akademgorodok, the Siberian City of Science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Graham, L.R. (1993). Science in Russia and the Soviet Union: A Short History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Dahan-Dalmedico, A. (1995). Mathématiques et politique. La Recherche, 26(278), 86–91.

- Chertok, B.E. (1999). Rakety i lyudi. Moscow: Mashinostroenie.

- Godunov, S.K., & Ryabenkii, V.S. (1964). Teoriya raznostnykh skhem. Moscow: Nauka.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).