Submitted:

07 December 2024

Posted:

09 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 65-04; 65Y04

1. Introduction and Notation

1.1. Preliminaries

1.2. General Notations

- – set of integers

- – set of integers , where

- – set of integers

- – set of real (complex) numbers

- – imaginary unit, where

- – sum of the scalar quantities

- – definite integral of the function on the interval

- ≺ – lexicographical order on the set of pairs defined as if , or and ; we write if , or

- – set of matrices A with elements , where is one of the sets , or

- – pth row of

- – qth column of

- – spectral norm in

- – matrix with unit elements

- – rank of the matrix

- – trace of the matrix

- – determinant of the matrix

- – identity matrix with and for

- – matrix with unique nonzero element, equal to 1, in position

- – nilpotent matrix with and for

- – eigenvalues of the matrix , where ; we usually assume that

- – singular values of the matrix , where , ; the singular values are ordered as

- – spectral norm of the matrix

- – condition number of the non-singular matrix

1.3. Machine Arithmetic Notations

- – set of finite positive (negative) machine numbers

- – set of finite machine numbers

- – rounded value of ; is computed as by the command sym(x,’f’), where , and m is odd if

- – set of positive (negative) machine numbers; we have

- () – machine number right (left) nearest to ; is obtained as X + eps(X)

- – machine epsilon; we have , ; is obtained as eps(1), or simply as eps

- – rounding unit

- – maximal integer such that positive integers are machine numbers; we have ,

- – maximal machine integer degree of 2; we have

- – maximal machine number; it is also denoted as realmax and we have eps(realmax) = 2^971

- – minimal positive normal machine number; it is also denoted as realmin

- – minimal positive subnormal machine number; it is found as eps(0)

- – rounded value of

- – normal range; numbers are rounded with relative error less than

- Inf (-Inf) – positive (negative) machine infinity

- NaN – result of mathematically undefined operation, comes from Not a Number

- – extended machine set

1.4. Abbreviations

| AI | – | artificial intelligence |

| ARRE | – | average rounding relative error |

| BFCT | – | brute force computational technique |

| CPRS | – | computational problem with reference solution |

| FPA | – | double precision binary floating-point arithmetic |

| LLSP | – | linear least squares problem |

| LSM | – | least squares method |

| LSP | – | least squares problem |

| MAI | – | mathematical artificial intelligence |

| MRRE | – | maximal rounding relative error |

| NLF | – | Newton-Leibniz formula |

| NFP | – | numerical fixed point |

| RRE | – | rounding relative error |

| RTA | – | real time application |

| VPA | – | variable precision arithmetic |

1.5. Software and Hardware

1.6. Problems with Reference Solution

2. Machine Arithmetic

2.1. Preliminaries

2.2. Violation of Arithmetic Laws

2.3. Numerical Convergence of Series

- numerically convergent if there is a positive and such that for ; the number S is called numerical sum of the series .

- numerically divergent if there is such that for ; in this there are now terms for

- numerically undefined if there is such that for and

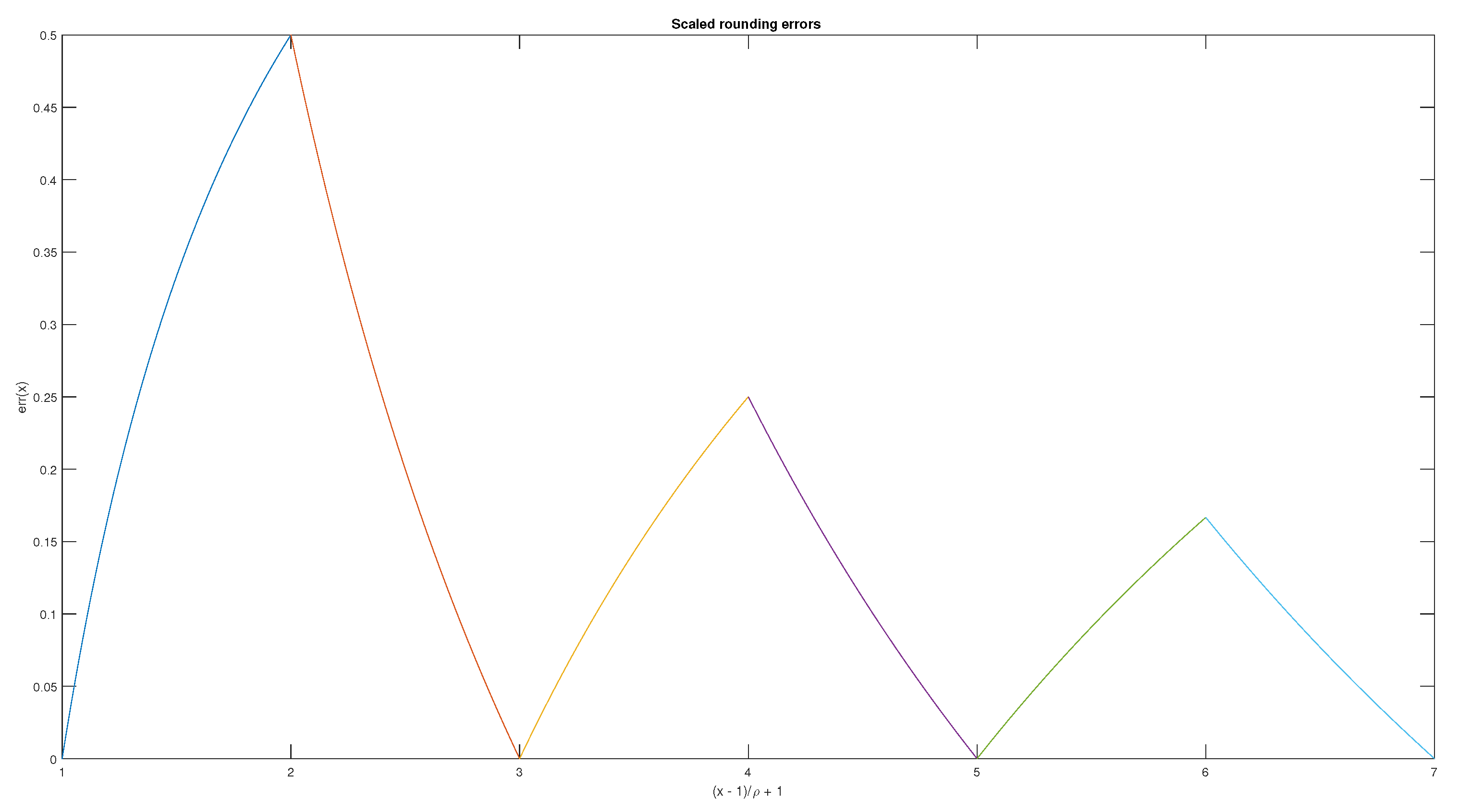

2.4. Average Rounding Errors

| m | |||

| 10 | |||

| 100 | |||

| 1000 |

3. Numerically Stable Computations

3.1. Lipschitz Continuous Problems

- The function is Lipschitz continuous if and is not Lipschitz continuous if .

- The function is Lipschitz continuous if and is not Lipschitz continuous if .

- The function , , is Lipschitz continuous if and is not Lipschitz continuous if .

- The function for and , is differentiable on but is not Lipschitz continuous.

- The sensitivity of the computational problem relative to perturbations in the data d measured by the Lipschitz constant L of the function f

- The stability of the computational algorithm expressed by the constants

- The FPA characterized by the rounding unit ρ and the requirement that the intermediate computed results belong to the normal range

- well conditioned if ; in this case we may expect about true decimal digits in the computed solution

- poorly conditioned if ; in this case there may be no true digits in the computed solution

3.2. Hölder Continuous Problems

- The code roots is fast and works, on middle power computer platforms, with equations of degree n up to several thousands but gives large errors in case of multiple roots. This code solves algebraic equations only.

- The code vpasolve works with VPA corresponding to 32 true decimal digits with equations of degree n up to several hundreds but may be slow in some cases. This code works with general equations as well finding one root at a time.

- The code fzero is fast but finds one root at a time. It may not work properly in case of multiple roots of even multiplicity. This code works with general finite equations as well.

3.3. Golden Rule of Computations

4. Extremal Elements of Arrays

4.1. Vectors

4.2. Matrices

4.3. Application to Voting Theory

5. Problems with Reference Solution

5.1. Evaluation of Functions

5.2. Linear Algebraic Equations

- Standard solution X_1 = A\b obtained by Gauss elimination with partial pivoting based on LR decomposition of A, where L is lower triangular matrix with unit diagonal elements, R is upper triangular matrix with nonzero diagonal elements and P is permutation matrix.

- Solution X_2 = R\(Q’*b) obtained by QR decomposition [Q,R] = qr(A) of A, where , the matrix Q is orthogonal and the matrix R is upper triangular.

- Solution X_3 = inv(A)*b based on finding the inverse of A.

5.3. Eigenvalues of Machine Matrices

- For we have , and , where the quantity 1.0000 has at least 5 true decimal digits and is a small imaginary tail which may be neglected. This result seems acceptable.

- For we have , and , . With certain optimism these results may also be declared as acceptable.

- For a computational catastrophe occurs with (true), (completely wrong) and , (also completely wrong). Here surprisingly is computed as which differs from 1 (which is to be expected) but differs also from . It is not clear what and why had happened. Using the computed coefficients , the roots of the characteristic equation now are , instead of the computed and . This is a strange wrong result.

- We give also the results for which are full trash and are served without any warning for the user. We have , and . We also get for completeness.

6. Zeros of Functions

- Find one particular solution of equation in the interval T.

- Find the general solution of equation in the interval T.

- Find all roots of a given nth degree polynomial .

7. Minimization of Functions

7.1. Functions of Scalar Argument

7.2. Functions of Vector Argument

- the computational problem

- the computational algorithm

- the FPA

- the computer platform

- the starting point

8. Canonical Forms of Matrices

8.1. Preliminaries

8.2. Jordan and Generalized Jordan Forms

- implies

- implies

- If then is the group .

- If , , then is the set of matrices and , where .

- If then is the set of matrices , .

- implies

- implies .

8.3. Condensed Schur Form

9. Least Squares Revisited

9.1. Preliminaries

9.2. Nonlinear Problems

9.3. Linear Problems

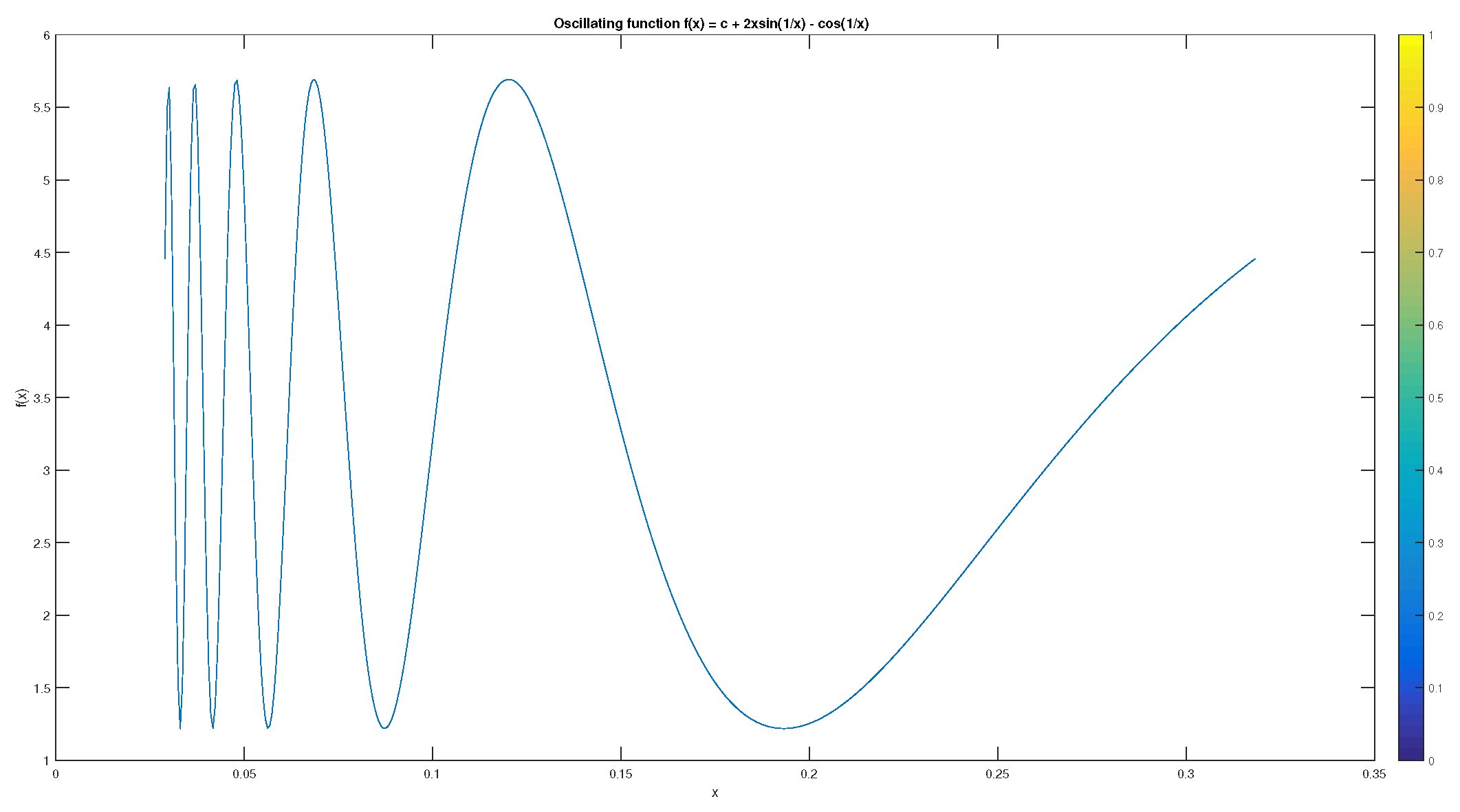

- The function is smooth and decreasing.

- The function is smooth and non-monotone in each interval , where .

- The function (whenever defined) is smooth and non-monotonic in each arbitrarily small subunterval of the interval , where .

10. Integrals and Derivatives

10.1. Integrals

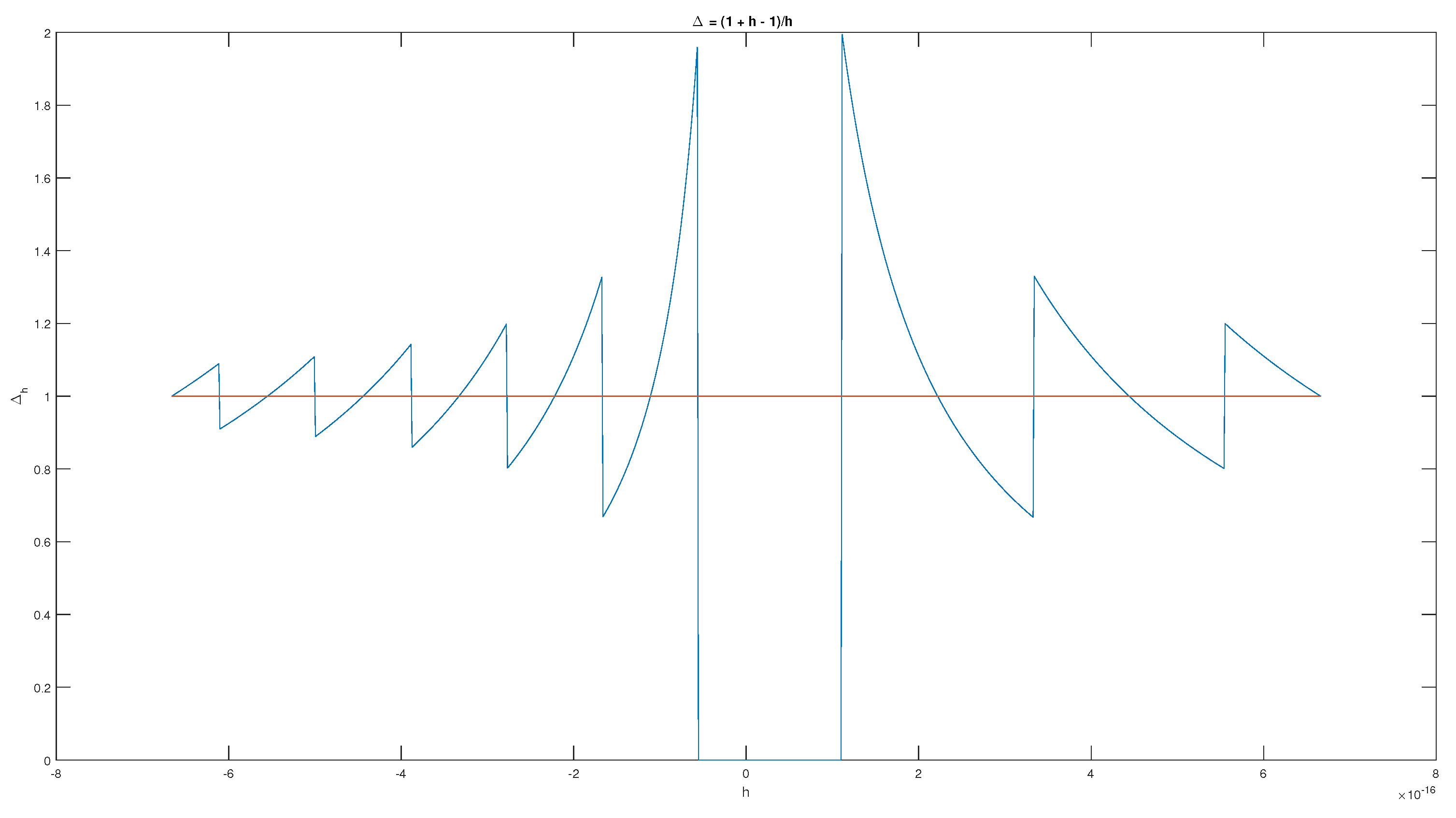

10.2. Derivatives

11. VPA versus FPA

12. Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stoer, J.; Bulirsch, R. Introduction to Numerical Analysis; Springer New York: New York, 2002; ISBN 978-0387954523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faires, D.; Burden, A. Numerical Analysis; Cengage Learning: Boston, 2016; ISBN 978-1305253667. [Google Scholar]

- Chaptra, S. Applied Numerical Methods with MATLAB for Engineers and Scientists (5th edition); McGraw Hill, 2017; ISBN 978-12644162604. [Google Scholar]

- Novak, K. Numerical Methods for Scientific Computing; Equal Share Press, 2022; ISBN 978-8985421804. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, T.; Braun, R. Fundamentals of Numerical Computations; SIAM, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TheMathWorks, Inc. MATLAB Version 9.9.0.1538559 (R2020b); The MathWorks, Inc.: Natick, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: www.mathworks.com.

- Higham, D.; Higham, N. MATLAB Guide, 3rd ed.; SIAM: Philadelphia, 2017; ISBN 978-1611974652. [Google Scholar]

- Maplesoft. Maple 2017.3. Ontario, 2017. Available online: www.maplesoft.com/ products/maple/.

- Mathematica. Available online: www.wolfram.com/mathematica/.

- WolframAlpha. Available online: www.wolframalpha.com/.

- Borbu, A.; Zhu, S. Monte Carlo Methods; Springer: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-9811329708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; et al. Advancing mathematics by guiding human intuition with AI. Nature 2021, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, T. Why mathematics is set to be revolutionized by AI. Nature 2024, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 754-2019; IEEE Standard for Floating-Point Arithmetic. IEEE Computer Society: NJ, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Higham, N. Accuracy and Stability of Numerical Algorithms; SIAM: Philadelphia, 2002; ISBN 0-898715210. [Google Scholar]

- Higham, N.; Konstantinov, M.; Mehrmann, V.; Petkov, P. The sensitivity of computational control problems. IEEE Control Systems Magazine 2004, 24, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D. What every computer scientist should know about floating-point arithmetic. ACM Computing Surveys 1991, 23, 5–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugh, C. Real Mathematical Analysis; Springer Nature: Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-3319177700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinov, M.; Petkov, P. Computational errors. International Journal of Applied Mathematics 2022, 1, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balinski, M.; Young, H. Fair Representation: Meeting the Ideal One Man One Vote, 2nd ed.; Brookings Institutional Press: New Haven and London, 2001; ISBN 978-0815701118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A. Numerical Methods, 3rd ed.; LCCN 57004892; London, Butterworths Scientific Publications: London, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinov, M.; Petkov, P. Remainders vs. errors. AIP Conference Proceedings 2016, 1789, 060007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarias, J.; Reeds, J.; Wright, M.; Wright, P. Convergence properties of the Nelder-Mead simplex method in low dimensions. SIAM Journal on Optimization 1998, 9, 112–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelder, J.; Mead, R. A simplex method for function minimization. Computer Journal 1965, 7, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossendrijver, M. Ancient Babylonian astronomers calculated Jupiter’s position from the area under a time-velocity graph. Science 2016, 351, 482–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, Q.; Schmeisser, G. Characterization of the speed of convergence of the trapezoidal rule. Numerische Mathematik 1990, 57, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, K. An Introduction to Numerical Analysis, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0471500230. [Google Scholar]

- Glazman, M.; Ljubich, J. Finite-Dimensional Linear Analysis: A Systematic Presentation in Problem Form (Dover Books in Mathematics); Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-04866453323. [Google Scholar]

- Jackobson, N. Basic Algebra I; W. Freeman & Co Ltd.: London, UK, 1986; ISBN 978-07167114804. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, G. The Theory of Partitions, (revisited edition); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2008; ISBN 978-0521637664. [Google Scholar]

- Konstantinov, M.; Petkov, P. On Schur forms for matrices with simple eigenvalues. Axioms 2024, 13, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| m | err | est | err/est |

| 2 | 0.0349 | ||

| 3 | 0.0187 | ||

| 4 | 9.1475 | 0.0272 | |

| 5 | 1.0002 | 4.6283 | 0.2161 |

| n | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

| 1.73 | 1.78 | 1.53 | 1.95 | 1.62 | 1.60 | 1.84 | 1.72 | 2.03 | |

| n | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 1.76 | 2.04 | 1.94 | 2.10 | 1.92 | 2.06 | 2.01 | 1.97 | 1.91 |

| n | ||

| 5 | ||

| 10 | ||

| 100 | ||

| 1 000 | ||

| 10 000 | ||

| 100 000 | ||

| 1 000 000 | ||

| 1 500 000 | ||

| 2 000 000 | ||

| 5 000 000 | ||

| 10 000 000 | ||

| 50 000 000 | ||

| 100 000 000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).