1. Introduction

The advent of large-scale quantum computing represents a paradigm shift in computational capabilities with profound and urgent implications for cryptographic security. Shor’s algorithm [

1], which efficiently factors large integers and computes discrete logarithms on a quantum computer, directly threatens the foundational hardness assumptions of widely deployed public-key cryptosystems such as RSA, Diffie-Hellman, and elliptic curve cryptography. This impending vulnerability has spurred global efforts in post-quantum cryptography (PQC) [

2], seeking to develop new classical algorithms resistant to quantum attacks. However, an alternative and complementary approach emerges from the quantum domain itself: constructing cryptographic schemes whose security is rooted in the fundamental laws of quantum physics, rather than in computational complexity assumptions.

1.1. Quantum Encryption Paradigms: From Key Distribution to Direct Encryption

Quantum cryptographic strategies can be broadly classified into three categories based on their operational modality and physical scale: quantum key distribution (QKD), quantum secure direct communication (QSDC), and quantum direct encryption schemes such as QEPS—the latter encompassing both symmetric and public-key variants.

Quantum Key Distribution (QKD) is a

micro-scale approach that operates in the deep quantum regime with single photons or weak coherent pulses. Exemplified by the BB84 protocol, its security stems from the no-cloning theorem and the detectable disturbance caused by measuring quantum states in the wrong conjugate basis (e.g., rectilinear vs. diagonal polarization) [

1]. While QKD provides information-theoretically secure key sharing, its practical deployment faces challenges including limited key rates, the need for dedicated quantum channels or careful coexistence with classical signals, and a critical reliance on an initial authenticated classical channel—which itself may require post-quantum cryptographic algorithms.

Quantum Secure Direct Communication (QSDC) represents an alternative micro-scale paradigm that enables the

direct transmission of secret messages without first establishing a shared key [

3,

4]. QSDC protocols typically employ single photons or entangled photon pairs to encode information directly, leveraging quantum principles such as entanglement swapping, superdense coding, or quantum one-time pads to ensure security [

5,

6]. Recent advances have extended QSDC to measurement-device-independent configurations [

7] and demonstrated real-time transmission over distances exceeding 100 km using weak coherent pulses [

8].

In contrast,

Quantum Encryption in Phase Space (QEPS) represents a

macro-scale approach that operates at the quantum-classical boundary using

bright coherent states—the very same information carriers underpinning modern coherent optical communications. Rather than distributing a key (as in QKD) or transmitting single-photon-encoded messages (as in QSDC), QEPS frameworks implement

direct encryption of data at the physical layer using high-power laser signals. These schemes exploit a different quantum uncertainty principle—the number-phase uncertainty

for coherent states [

9]—and the practical requirement of a phase-synchronized local oscillator (LO) for coherent detection. Here, security arises not from detecting an eavesdropper’s presence (as in QKD/QSDC), but from rendering their interception fundamentally futile: without the secret key, an eavesdropper cannot establish the correct phase reference for a coherent receiver and is thus limited to direct detection, which reveals only photon-number (amplitude) information while the encrypted data resides in the phase.

This tripartite classification highlights a key innovation of QEPS: it bridges the gap between the quantum-security of single-photon protocols and the practical high-speed infrastructure of classical coherent optics, offering a path toward quantum-resistant security that is compatible with existing optical networks without requiring single-photon sources or detectors.

1.2. Phase Space: The Arena for Optical Quantum Encryption

Phase space provides the natural mathematical framework for describing the quantum states of light used in optical communications, particularly coherent states . These quasi-classical states exhibit robust, laser-like properties while retaining intrinsic quantum noise. The phase-space formalism, visualized via Wigner functions or constellation diagrams, enables the intuitive design of encryption protocols as geometric transformations—rotations, displacements, and their dynamic combinations—applied directly to the optical field.

The evolution of QEPS has progressed through three generations of unitary operators, each enhancing security and compatibility:

Phase Operators (): Implementing rotations

, these operators form the basis of the original Quantum Public Key Envelope (QPKE) protocol [

10]. The same physical principle—randomizing the phase of a coherent state—was subsequently adapted for symmetric-key physical-layer encryption, leading to the QEPS-p scheme. This adaptation has been extensively studied via simulation [

11,

12,

13] and experimental demonstrations [

14,

15] for the QPKE scheme and experimental demonstration for QEPS-p symmetric encryption [

13]. However, pure phase encryption exhibits an inherent limitation: while effective for phase-encoded data (e.g., PSK), it becomes partially vulnerable for modulation formats that encode information in both amplitude and phase, such as quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM), as amplitude information remains partially exposed.

Displacement Operators (): To address this limitation, QEPS-d schemes were developed, employing the

reduced displacement operator

(defined by its action

) that translates coherent states across the entire phase space. This approach overcomes the amplitude-sensitivity of pure phase encryption by randomizing both quadratures, thereby enabling the secure encryption of arbitrary QAM formats [

16,

17]. Crucially, these reduced operators commute (

), making QEPS-d practically implementable with standard coherent optical hardware while expanding the cipher space to include the full two-dimensional constellation plane [

18].

Dynamic Displacement Operators (DDOs): Building upon both preceding approaches, the most recent advancement combines displacement and phase operations in time-varying sequences,

, yielding QEPS-dd. This dynamic framework creates a highly randomized and expansive cipher space through the continuous evolution of encryption parameters

and

according to cryptographic algorithms. By introducing temporal variability alongside spatial obfuscation, QEPS-dd offers enhanced security against advanced cryptanalytic techniques and adapts more robustly to evolving threat models [

19,

20].

This progression has been supported by significant experimental validation, including demonstrations of QEPS-d operating at up to 560 Gb/s over standard fiber using commercial coherent transceivers, where unauthorized decryption attempts yield a near-50% bit error rate [

18].

1.3. Quantum Public-Key Encryption in Phase Space

A seminal innovation within this domain is the Quantum Public Key Envelope (QPKE), a round-trip protocol that implements public-key functionality using coherent states [

10]. In this scheme, a recipient’s public key is a coherent state randomized by a secret phase

(the private key). A sender encodes a message phase

onto this state and returns it. Crucially, an eavesdropper intercepting the transmitted state cannot measure

without knowledge of

, as they lack the necessary LO phase reference for coherent detection. This elegantly leverages the practical requirements of measurement apparatus as a cryptographic feature, providing a quantum analogue of RSA-type encryption. Recent advances continue to explore physical-layer public-key encryption using coherent states and integrated photonics [

21].

Alternative implementations of optical public-key encryption have since emerged, demonstrating the versatility of physical-layer approaches. Notably, Wu

et al. demonstrated a public-key encryption scheme using partially coherent light and an on-chip Mach-Zehnder interferometer mesh, achieving 10 Gbit/s encrypted transmission over 40 km of fiber [

21]. While employing different physical resources (partially coherent light versus pure coherent states) and hardware (integrated photonic chip versus standard modulators), this work shares the same cryptographic objective: implementing public-key encryption at the optical physical layer without relying on computational complexity assumptions.

1.4. The Broader Landscape of Optical Physical-Layer Security

QEPS exists within a rich ecosystem of optical encryption techniques, each with distinct mechanisms. Chaotic encryption masks data within broadband, noise-like waveforms generated by nonlinear dynamics [

22]. Polarization-based schemes rapidly scramble the state of polarization using digital scramblers [

23]. Other approaches include cross-phase encoding with all-optical gates [

24], electro-optic phase feedback systems [

25], quantum homomorphic encryption [

26], and encryption exploiting spatial coherence properties [

27]. These diverse strategies offer varied trade-offs between security, data rate, complexity, and compatibility with existing network infrastructure.

Integrated photonic approaches represent another promising direction. Wu

et al. demonstrated public-key encryption using a lithium niobate photonic chip with a Mach-Zehnder interferometer mesh, encoding keys in the incoherent optical transmission matrix [

21]. This work highlights the potential for chip-scale integration of quantum-inspired encryption protocols, offering advantages in compactness, power efficiency, and compatibility with emerging photonic systems.

1.5. Chaos-Based Optical Encryption: A Comparative Perspective

Optical chaos encryption represents another prominent paradigm for achieving physical-layer security, leveraging the inherent nonlinear dynamics and sensitivity to initial conditions of chaotic systems [

28,

29]. In contrast to QEPS’s foundation in quantum phase-space transformations, chaos-based schemes typically employ synchronized chaotic carriers—generated via optical feedback, injection, or electro-optic loops—to mask or modulate information-bearing signals [

30,

31]. The security of these systems traditionally relies on the

computational difficulty of reconstructing nonlinear dynamics from observed signals and the

practical challenge of achieving precise synchronization without knowledge of system parameters (e.g., feedback delay, injection strength) [

32,

33].

Recent advances in chaos-based communications have focused on enhancing bandwidth, suppressing time-delay signatures to resist reconstruction attacks, and extending transmission distances [

30,

34]. Notably, the integration of digital signal processing (DSP) and deep learning has significantly improved chaos synchronization and decryption performance in long-haul and high-speed scenarios [

31,

35,

36]. For instance, deep neural networks have been employed to model chaotic transmitters, enabling high-quality synchronization and decryption at rates exceeding 100 Gb/s over several hundred kilometers of fiber [

22,

31]. Furthermore, chaotic encryption has been successfully demonstrated in free-space optical links, addressing challenges posed by atmospheric turbulence through adaptive optical processing [

37,

38].

Despite these impressive demonstrations, chaos-based encryption faces inherent challenges that distinguish it from the QEPS approach:

Security Foundation: Chaos security relies on

computational hardness—the difficulty of reconstructing nonlinear dynamics from intercepted signals. While sensitive to parameter mismatches, this security is not information-theoretic and can be vulnerable to advanced system identification or machine-learning attacks with sufficient intercepted signal length [

39,

40].

Synchronization Requirement: Most chaos schemes require active

synchronization between transmitter and receiver, either through common drive signals, matched parameters, or digital post-processing. This introduces a potential point of failure and added complexity, especially in dynamic or impaired channels [

41,

42].

Dual-Channel Architecture: Many chaos synchronization schemes (particularly drive-response configurations) inherently require two optical channels or signals: one for the chaotic carrier and another for the encrypted message, or dedicated synchronization preambles. This increases system complexity and reduces spectral efficiency compared to single-channel approaches.

Implementation Complexity: High-bandwidth chaos generation often involves specialized laser configurations, optical feedback loops, or careful parameter tuning, which can increase cost and reduce compatibility with standard telecom hardware [

29].

In contrast, QEPS operates on a fundamentally different principle: it exploits the quantum mechanical uncertainty of coherent states and the practical necessity of phase synchronization for coherent detection. Rather than hiding data within a complex analog waveform, QEPS disrupts the phase reference itself, creating a phase synchronization barrier that renders coherent demodulation impossible without the secret key. This approach offers several distinctive advantages:

Single-Channel Operation: QEPS operates over a single optical channel—the same channel used for standard coherent communication. No separate drive signals, synchronization channels, or pilot transmissions are required. Encryption and decryption are performed entirely within the standard modulation and demodulation process.

DSP Phase Synchronization as Cryptographic Control: In QEPS, the essential DSP function of carrier phase recovery (CPR) becomes cryptographically controlled. Authorized receivers use the shared secret to apply the inverse transformation before CPR, restoring a stable constellation that enables standard DSP to succeed. Unauthorized receivers cannot establish a phase reference, causing their CPR algorithms to fail and resulting in BER near 50%. Thus, QEPS transforms a routine DSP requirement into a cryptographic barrier.

No Continuous Synchronization Needed: Unlike chaos systems requiring continuous dynamical synchronization, QEPS decryption is a deterministic inversion of a unitary transformation using a shared key sequence.

Hardware Compatibility: QEPS transformations (phase shifts, displacements) are natively implemented using standard IQ modulators and coherent transceivers, ensuring seamless integration into existing optical networks.

Security Based on Physical Law: Security arises from the quantum noise of coherent states and the fundamental inability to establish a phase reference without the secret—a physical limitation rather than a computational assumption.

Summary Comparison: While both QEPS and chaos-based encryption aim to secure the optical physical layer, they represent divergent strategies with distinct trade-offs:

Chaos Encryption: Embeds data within a complex, noise-like analog waveform; requires synchronization mechanisms; often uses dual channels; security based on computational hardness of dynamics reconstruction.

QEPS: Denies signal recovery by cryptographically controlling phase synchronization; operates over a single channel; requires no additional synchronization; security based on physical impossibility of phase reference establishment without the secret key.

This distinction positions QEPS as a uniquely hardware-friendly, spectrally efficient, and quantum-resistant alternative, particularly suited for high-speed coherent systems where phase synchronization is already a critical operational requirement. The choice between these approaches depends on specific application requirements: chaos encryption may offer advantages in certain analog security contexts, while QEPS provides a more integrated solution for digital coherent communication systems seeking quantum-resistant security with minimal infrastructure changes.

1.6. Scope and Contribution of This Review

This comprehensive review synthesizes the theoretical foundations, security analyses, experimental progress, and future trajectories of Quantum Encryption in Phase Space. We provide a unified perspective on the QEPS framework, tracing its evolution from phase-based to dynamic displacement operator approaches. We elucidate its core security principle—exploiting the number-phase uncertainty and LO-synchronization requirement to render eavesdropping futile—and contrast this with the disturbance-detection basis of QKD, the single-photon direct transmission of QSDC, and the synchronization-dependent paradigm of chaos-based encryption. By examining both theoretical models and experimental demonstrations, we assess the practical viability of QEPS for securing high-speed optical networks against both classical and quantum computational threats. Furthermore, we situate QEPS within the broader context of optical physical-layer security, highlighting its unique advantages as a protocol capable of leveraging standard telecom hardware to provide quantum-enhanced security. Through this synthesis, we aim to provide researchers and practitioners with a clear understanding of the potential, challenges, and future directions of phase-space encryption in building the quantum-resilient communication infrastructure of tomorrow.

2. Theoretical Foundations: Coherent States and Phase-Space Dynamics

2.1. Coherent States: Bridging Classical and Quantum Optics

The coherent state

, first formalized by Glauber [

9], represents a fundamental cornerstone of quantum optics and serves as the primary information carrier in modern coherent optical communications. Generated by displacing the vacuum state,

, where

encodes both amplitude and phase information, coherent states uniquely bridge the classical and quantum domains. They are quasi-classical, exhibiting laser-like properties while retaining intrinsic quantum noise. This duality makes them ideally suited for high-speed communications and, as we will show, for quantum-inspired encryption. Their defining properties include:

Minimum Uncertainty: Coherent states saturate the Heisenberg uncertainty principle with equal uncertainties in the two field quadratures ( in appropriate units). This makes them the closest quantum mechanical analogue to a stable classical electromagnetic wave.

Poissonian Photon Statistics: The photon number distribution is Poissonian, , with mean photon number . This matches the statistical behavior of an ideal laser operating well above threshold and underpins the signal-to-noise characteristics in coherent optical systems.

Overcompleteness: Coherent states form an overcomplete basis, satisfying the resolution of identity . This property allows any optical quantum state to be expressed as a superposition of coherent states, providing a powerful representation for calculations.

-

Displacement Property and its Simplification: The action of a displacement operator is given by

. This reveals two distinct effects: a

translation in phase space from

to

, and an overall

global phase factor. Since global phases are unobservable in physical measurements, the core action can be captured by a

reduced displacement operator defined by its action:

This simplified operator retains the additive property

and, critically, commutes:

. As established in QEPS-d [

16], this commutativity is a key enabler for practical implementation, allowing encryption and decryption sequences to be applied without concern for operator ordering, thus facilitating direct realization with standard in-phase/quadrature (IQ) modulators.

The combination of robust propagation through optical fiber and inherent quantum-mechanical character makes coherent states a uniquely powerful substrate for physical-layer encryption protocols like QEPS, which harness these properties for security.

2.2. Phase-Space Formalism: Visualizing Quantum Encryption

Phase space provides an elegant and intuitive framework for representing quantum states of light, where each point

corresponds to a coherent state. Unlike discrete variable representations, this continuous phase space allows quantum states to be fully described by quasi-probability distributions that seamlessly blend classical-like features with quantum noise:

For a pure coherent state , the Wigner function is a symmetric Gaussian peak centered at , while the Q-function represents its overlap with a probe coherent state. The finite width of these distributions is a direct manifestation of the quantum noise inherent to the state. This geometric visualization is particularly powerful for designing and analyzing encryption schemes: rotations and translations in phase space correspond directly to physically implementable unitary operations on the optical field. Moreover, the quantum noise—apparent as the finite breadth of the distributions—provides an innate source of randomness that underpins the cryptographic security of QEPS by obscuring the exact location of the encrypted symbol.

2.3. Key Operator Transformations in Phase Space

The QEPS framework is built upon two fundamental classes of unitary transformations that physically manipulate coherent states in phase space. These operators correspond directly to standard optical components, providing a clear path from theory to experimental implementation.

2.3.1. Phase Operators: Phase-Space Rotations

The phase operator

implements rotations in phase space. Acting on a coherent state

, it produces a rotated coherent state:

This operation is physically realized by a phase modulator that applies a controllable phase delay

. For encryption purposes, random phase rotations effectively obscure the original phase information, making this approach particularly suitable for phase-encoded data (e.g., in PSK formats). The original Quantum Public Key Envelope (QPKE) protocol leveraged this transformation, using a secret phase shift as a private key [

10]. In a symmetric-key setting, applying a random phase rotation

(determined by a shared secret key) to a data-bearing coherent state

yields the cipher state:

2.3.2. Displacement Operators: Phase-Space Translations

The displacement operator

implements translations in phase space. Its action on a coherent state is given by:

Physically, this corresponds to adding a complex field amplitude

to the optical signal, an operation natively performed by an in-phase/quadrature (IQ) modulator. For cryptographic applications, the global phase factor

is physically irrelevant and can be omitted, leading to the reduced displacement operator

with the simplified transformation:

In the QEPS-d encryption scheme [

16], a data symbol represented by

is encrypted by applying a secret displacement

:

The displacement vector , generated from a shared secret key, randomizes the symbol’s position across the entire constellation plane.

2.3.3. Dynamic Displacement Operators: Combined Transformations

The most general encryption transformation within the QEPS framework combines both displacement and phase operations, often in a time-dependent sequence. A dynamic displacement operator (DDO) can be defined as:

where

and

evolve according to a cryptographically secure algorithm driven by the secret key. Applying this operator to a data state yields the cipher state:

This approach, formalized in QEPS-dd [

19,

20], creates a cipher space with enhanced dimensionality and temporal variability, significantly increasing the difficulty of cryptanalysis.

2.3.4. Non-Commutativity: The Quantum Mechanical Heart of Security

The mathematical bedrock of QEPS security is the fundamental non-commutativity of the displacement and phase operators. For the full operators, this is expressed as:

which follows from the canonical commutation relation

. This algebraic property is a direct consequence of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle applied to the conjugate observables of quadrature amplitude and phase. Cryptographically, it ensures that an eavesdropper lacking the secret key sequence cannot determine or invert the composite encryption transformation—even with perfect measurement equipment. Applying decryption operations in the wrong order (due to an incorrect key guess) yields a result quantum-mechanically distinct from the original message. This intrinsic quantum property, augmented by the practical necessity of a phase-synchronized local oscillator for coherent detection, establishes a multi-layered security barrier fundamentally different from classical computational encryption.

These theoretical pillars—coherent states as robust, quantum-encoded information carriers; phase space as an intuitive encryption design arena; explicit transformation equations for encryption operations; and non-commuting operators as enforcers of cryptographic secrecy—collectively form the essential mathematical foundation for the Quantum Encryption in Phase Space framework detailed in the following sections.

These theoretical pillars—coherent states as robust, quantum-encoded information carriers; phase space as an intuitive encryption design arena; explicit transformation equations for encryption operations; and non-commuting operators as enforcers of cryptographic secrecy—collectively form the essential mathematical foundation for the Quantum Encryption in Phase Space framework detailed in the following section.

3. The QEPS Framework: Principles and Mechanisms

Building upon the theoretical foundations of coherent states and phase-space transformations, we now present the

Quantum Encryption in Phase Space (QEPS) framework as a systematic approach to physical-layer encryption for coherent optical communications [

10,

13,

16,

18,

20]. The framework leverages the quantum mechanical properties of coherent states and unitary operators to achieve secure, high-speed data transmission over existing optical infrastructure.

It is noteworthy that the QPKE protocol represents a specific application architecture (a round-trip, public-key-like protocol) that implements the phase randomization principle of QEPS-p. In contrast, QEPS-p, QEPS-d, and QEPS-dd are defined primarily by their encryption operators and are typically deployed in symmetric-key configurations.

3.1. Core Encryption Protocol Architecture

The QEPS encryption process employs

phase shift operators and

displacement operators to transform data-bearing coherent states. Each modulated symbol in a coherent optical communication system is represented by a single coherent state

drawn from a

K-QAM constellation. The encryption transformation for each symbol is expressed as:

where

represents a unitary transformation parameterized by a shared secret key. This formulation encompasses three main variants, each characterized by the specific form of

:

QEPS-p (Phase-based): Uses only phase shift operators, rotating constellation points around the origin:

where

is derived from the secret key.

QEPS-d (Displacement-based): Uses only displacement operators, shifting the entire constellation in phase space:

where

is derived from the secret key.

QEPS-dd (Dual Displacement Operator): Combines both operators in sequence:

where both

and

are derived from the secret key. The

dynamic nature arises because the combined transformation creates an effective displacement

that depends on

, making the encryption state-dependent and enhancing security.

The encryption parameters

can vary dynamically from symbol to symbol according to a predetermined sequence generated from the shared secret key, forming what is termed a

Dynamic Displacement Operator Pad (DDOP) [

20], using Quantum Permutation Pad or QPP [

43]. This time-varying encryption ensures that each symbol undergoes a unique transformation, preventing pattern recognition by unauthorized receivers.

The physical implementation typically employs a single IQ-MZM modulator that applies the combined transformation in a single step, with the complex driving signals calculated from both the data symbol and the encryption parameters . This approach maintains compatibility with standard coherent optical transceivers while introducing the quantum encryption layer.

3.2. Channel Normalization via Digital Signal Processing

A critical enabling technology for QEPS is modern

Digital Signal Processing (DSP) [

44,

45,

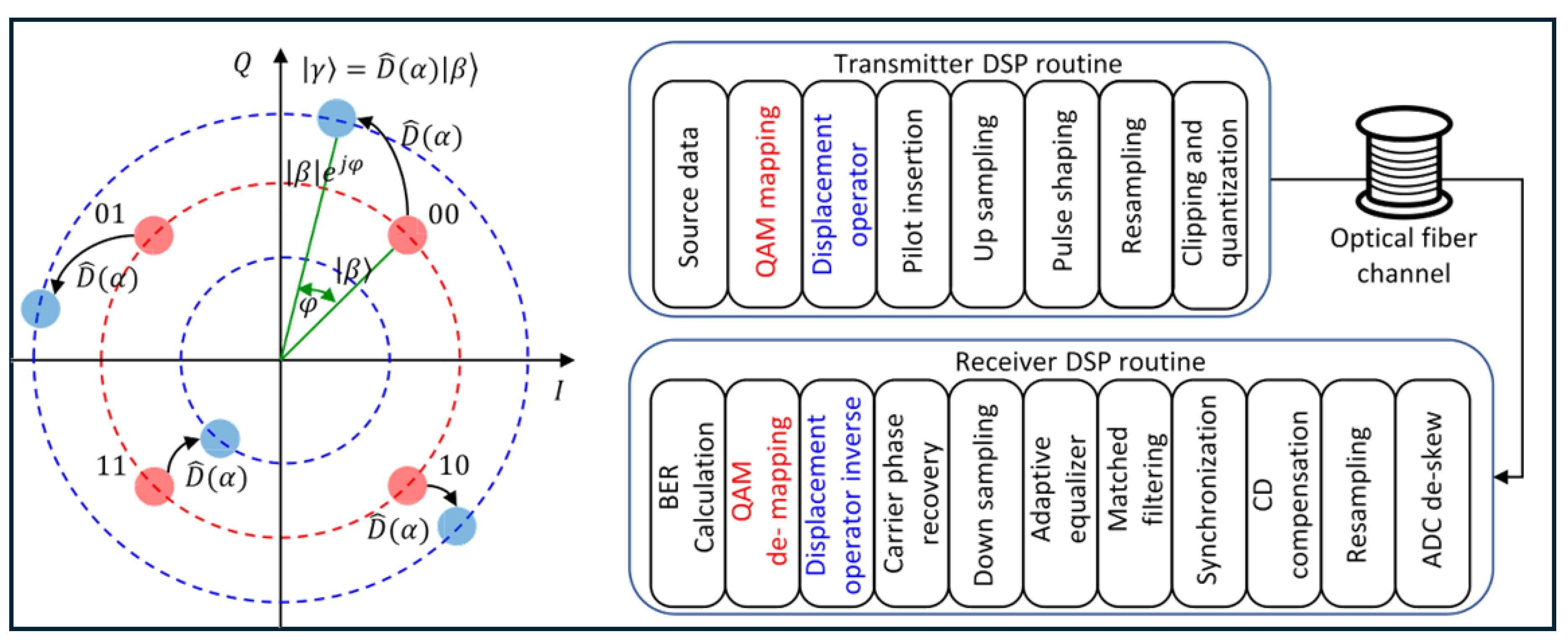

46] in coherent optical systems. The DSP integration framework, illustrated in

Figure 1 [

47] for the QEPS-d variant, applies

equivalently to all QEPS variants (p, d, and dd) with appropriate substitutions of the encryption/decryption operators. For authorized parties, this DSP performs the dual function of decrypting the signal and normalizing channel impairments, creating an effective

DSP-trusted channel.

The complete transmitter processing chain operates as follows:

Source data undergoes QAM Mapping to generate complex symbols , which correspond mathematically to coherent states .

The Encryption Operator (specific to the QEPS variant) applies the encryption. For QEPS-d: ; for QEPS-p: ; for QEPS-dd: .

The encrypted complex waveform then enters the standard Transmitter DSP routine: pilot symbols are inserted for synchronization, the signal is up-sampled, pulse-shaped, re-sampled to the DAC rate, and finally undergoes clipping and quantization before optical modulation.

After propagation through the optical fiber channel and coherent detection with ADC de-skew correction, the receiver DSP chain executes:

Synchronization aligns the signal using inserted pilots.

Matched filtering optimizes the signal-to-noise ratio.

The Adaptive equalizer compensates for linear channel impairments (e.g., chromatic and polarization-mode dispersion).

Down-sampling reduces the data to one sample per symbol.

Carrier phase recovery corrects for laser phase noise and frequency offset.

The Inverse Encryption Operator is applied using the shared key. This crucial decryption step restores the original constellation point .

Finally, QAM de-mapping recovers the bit stream for BER calculation.

This sequence embodies channel normalization for the authorized user: standard DSP algorithms first condition the signal, then decryption restores its structure, enabling accurate demapping. The entire chain compensates for physical channel effects, resulting in a low-BER link—the DSP-trusted channel.

Conversely, for an eavesdropper lacking the secret key, step 6 (Inverse Encryption Operator) cannot be performed. Without the correct inverse transformation, the signal constellation remains scrambled in the optical field domain. Importantly, this is not merely a digital encryption layer like AES, which operates on bits and is independent of the transmission channel. Rather, QEPS fundamentally alters the physical waveform such that the transmitted symbols are no longer standard QAM symbols recognizable to a classical coherent receiver.

This physical transformation has profound implications for the eavesdropper’s recovery attempt. While an eavesdropper can execute the initial DSP steps (1-5) on the encrypted waveform —as these algorithms operate on signal statistics and pilots rather than specific constellation geometry—the process breaks down at the critical decryption step:

Without the secret key, the Inverse Encryption Operator cannot be applied correctly. Any attempt at inversion (including skipping it entirely) leaves the signal in a scrambled state.

When this scrambled signal reaches QAM de-mapping, it no longer corresponds to valid constellation points, preventing meaningful data recovery.

The encryption’s effect is thus not to prevent initial DSP convergence, but to ensure that the signal presented to the decision circuitry remains indistinguishable from noise after all channel compensation has been applied.

Even with brute-force key search, each trial would require complete QAM demapping and error evaluation, as the DSP chain up to carrier recovery may still execute on incorrectly decrypted signals without obvious failure cues.

Thus, while AES provides digital security by scrambling bits, QEPS provides physical-layer security by ensuring that only the legitimate receiver can transform the compensated signal into a decodable constellation. The security manifests not in early DSP failure, but in the final impossibility of mapping the processed signal to valid data symbols without the precise inverse transformation.

3.3. Cipher Space and Key Space Characterization

The security of QEPS is rooted in the expansion of the original message constellation into a randomized cipher constellation. For a

K-QAM constellation

, the cipher space

is:

where

is the set of unitary transformations achievable with valid keys. The

cipher expansion ratio:

is maximized when using a

Dynamic Displacement Operator Pad (DDOP) combined with a

Quantum Permutation Pad (QPP) [

48]. A DDOP is constructed from a publicly known set of

DDOs:

which is then permuted via QPP using a shared secret

s to produce a random pad:

This process maximizes the cipher constellation points to nearly and ensures semantic security by making the ciphertext distribution statistically indistinguishable from random noise to an eavesdropper.

3.4. Dynamical Evolution and Security Enhancement

Time-dependent key sequences introduce

dynamical evolution into the encryption process, preventing pattern analysis and providing forward secrecy. The encryption parameters can evolve via cryptographically secure pseudorandom number generators (PRNGs) or chaotic maps:

where

is the

n-th state of the master key. This temporal evolution, combined with the non-commutativity of the operators:

creates a

generalized uncertainty principle that prevents an eavesdropper from simultaneously determining both the displacement and phase parameters. The result is a

bit error rate (BER) approaching 50% for any measurement without the correct DDOP.

The security against brute-force attacks is quantified by the

effective entropy of the DDOP. For an

ℓ-bit secret, the entropy is:

which grows factorially with

ℓ. For example, with

,

bits, far exceeding NIST post-quantum security requirements.

3.5. Practical Implementation and Experimental Validation

Practical implementation uses standard coherent optical modules:

Transmitter: Laser diode, IQ-MZM modulator driven by DACs, DSP for pulse shaping and pilot insertion, with QEPS encryption integrated into the modulation process.

Receiver: Coherent detector with local oscillator, ADC, QEPS decryption module, followed by standard DSP for channel compensation.

The round-trip QPKE protocol demonstrates how QEPS can emulate public-key functionality: Bob sends an encrypted “envelope” to Alice, who modulates her secret and returns . Bob then decrypts with to recover . This eliminates the need for pre-shared secrets and enables authentication through self-shared randomness.

Experimental demonstrations have validated QEPS at speeds up to 560 Gbps (32-QAM over 80 km) with BER below the forward error correction threshold, confirming its feasibility for real-world high-speed quantum-secure optical communications. The experimental results consistently show that without decryption, the measured BER remains at approximately 48-49%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the encryption in preventing unauthorized reception.

4. Physical-Layer Security Principle: Phase Synchronization Barrier

This section synthesizes the security arguments common to Quantum Encryption in Phase Space (QEPS) implementations as advanced in the literature. Rather than proposing new formal proofs, we distill the operational principles and experimental evidence that collectively establish QEPS’s security foundation. The central thesis—that randomized unitary transformations disrupt the phase reference essential for coherent detection—has been consistently validated across phase-only (QEPS-p), displacement-based (QEPS-d), and dynamic displacement operator (QEPS-dd) implementations [

13,

14,

16,

18]. We contrast this physical-layer mechanism with classical computational security and other optical encryption paradigms, situating QEPS within the broader landscape of quantum-inspired security for optical communications.

4.1. The Phase Synchronization Imperative in Coherent Detection

Accurate demodulation in coherent optical communication necessitates establishing a stable phase reference at the receiver. Carrier phase recovery (CPR), essential for decoding quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) signals, depends fundamentally on the presence of a structured constellation in phase space. In conventional coherent systems, DSP-based phase recovery typically follows one of two paradigms:

Active phase recovery (e.g., blind phase search, decision-directed phase-locked loops) estimates and compensates phase drift using known statistical or structural properties of the transmitted symbols.

Passive phase mitigation (e.g., differential encoding, phase-diverse reception) reduces sensitivity to phase noise through signal design without explicit feedback.

Both approaches assume that received symbols cluster around a finite, stable set of constellation points—an assumption that QEPS deliberately violates by encrypting information directly at the coherent-state level prior to standard modulation.

4.2. The Phase Synchronization Barrier: Core Mechanism

The security rationale for QEPS stems from its ability to cryptographically deny the phase reference required for coherent detection. By applying symbol-by-symbol unitary transformations—phase shifts, displacements, or their combination—QEPS encrypts the data-bearing coherent state

into:

where the encryption parameters

are derived from a secret key and vary dynamically. This process deliberately destroys the structured clustering of constellation points in phase space that is essential for any DSP-based carrier recovery algorithm.

For an authorized receiver possessing the key, decryption (applying at the appropriate DSP stage) restores the original QAM constellation before CPR is attempted. The DSP then operates on a legitimate signal, achieving phase synchronization and yielding low bit-error rate (BER).

For an eavesdropper, however, the encrypted signal presents a fundamental obstruction. While initial DSP steps (synchronization, equalization) may process the encrypted waveform, the critical CPR stage fails. Without the correct inverse transformation, the received symbols do not converge to a discrete constellation but instead form a diffuse cloud in phase space. Consequently, the eavesdropper cannot establish a meaningful phase reference—a condition termed the phase synchronization barrier in QEPS literature.

Numerical simulations and experimental studies consistently report that without the secret key, eavesdroppers’ BER saturates near 50% regardless of the DSP strategy employed [

13,

16]. This operational result forms the primary evidence for QEPS security: the signal is rendered

physically undecodable to unauthorized parties.

4.3. Core Security Rationale: Basis Randomization and Restoration

The phase synchronization barrier described above can be fundamentally understood as a consequence of basis randomization at the coherent-state level. At its essence, QEPS leverages a shared secret of effectively unlimited length to dynamically randomize the communication basis for coherent states carrying K-PSK or K-QAM symbols. The secret key controls a sequence of unitary transformations—phase rotations, displacements, or their combination—that collectively define a time-varying encryption basis.

This basis randomization directly implements the phase synchronization barrier: by randomizing the communication basis, QEPS ensures that coherent detection without the secret key amounts to measurement in a misaligned basis, leading to the observed 50% BER.

For authorized communication, the legitimate receiver applies the inverse transformation sequence using the same shared secret, thereby restoring the original communication basis before coherent detection and demodulation. This restoration process reconstructs the structured constellation necessary for standard digital signal processing (DSP) algorithms to succeed.

For an eavesdropper lacking the secret, the intercepted signal remains encoded in a randomized basis. Coherent detection—requiring precise phase synchronization with the transmitted signal—effectively constitutes a measurement in a random basis. As established in quantum measurement theory, such misaligned measurements yield maximally ambiguous results. In practical terms, this manifests as a bit error rate (BER) approaching 50%, equivalent to random guessing, regardless of the eavesdropper’s receiver sophistication or computational resources.

This basis randomization mechanism differs fundamentally from conventional encryption in both scope and implementation:

Scope: Operates at the physical waveform level rather than the digital bit level.

Secret Nature: Utilizes a continuously evolving parameter stream rather than a fixed-length cryptographic key.

Security Consequence: Creates physical undecodability rather than computational hardness.

The experimental evidence reviewed in

Section 5 consistently validates this mechanism, showing authorized receivers achieving BERs below forward error correction thresholds while unauthorized receivers experience BERs near 50% across all QEPS variants.

4.4. Security Evolution Across QEPS Variants

4.4.1. QEPS-p: Phase-Only Encryption

QEPS-p employs random phase-shift operators

to rotate constellation points around the origin while preserving amplitudes. The resulting cipher forms concentric amplitude rings. While an eavesdropper may infer partial amplitude information, randomized phase relationships prevent stable carrier phase recovery, enforcing the phase synchronization barrier [

13]. Studies present QEPS-p in two cryptographic contexts: as a

symmetric encryption scheme with shared phase sequences, or as a

public-key-like mechanism (QPKE) in round-trip architectures where security arises from inability to coherently reverse an unknown public phase transformation [

10].

4.4.2. QEPS-d: Displacement-Based Encryption

QEPS-d employs random displacement operators

to translate constellation points across phase space. This obscures both amplitude and phase information, presenting a cipher constellation with no discernible structure. Experimental analyses confirm that without the displacement sequence, both active and passive DSP methods fail due to absence of differential or clustered features, maintaining the 50% BER barrier [

16].

4.4.3. QEPS-dd: Dynamic Displacement Operator Encryption

QEPS-dd combines both operations: , where the effective displacement depends on the data symbol . This introduces data-dependent randomness, making the cipher appear as continuous noise in phase space. Research indicates this dynamic randomization prevents adaptive tracking, ensuring robust security even against sophisticated DSP-based attacks.

4.5. Contrast with Classical Digital Encryption

In conventional digital encryption (e.g., AES), encrypted data are transmitted using standard modulation formats. An eavesdropper can recover digital ciphertext with high fidelity using standard coherent receivers; security then relies entirely on computational hardness of decrypting that ciphertext.

In contrast, QEPS encrypts at the analog coherent-state level before modulation. The resulting waveform does not conform to a standard QAM constellation and is physically undecodable without the secret key. Even with ideal coherent receivers and advanced DSP, eavesdroppers cannot recover usable digital symbols because the requisite phase synchronization is cryptographically denied at the physical layer. Thus, while AES provides digital-layer security (ciphertext recoverable, but hard to decrypt), QEPS provides physical-layer security (ciphertext unrecoverable as structured symbols).

4.6. The Nature of Secrecy and Attack Considerations

A key distinction from classical symmetric encryption lies in the nature of the secret. In conventional systems, the secret is a finite digital key (e.g., 256 bits), and adversaries can recover structured ciphertext for offline cryptanalysis. In QEPS, the effective secret is a continuously varying stream of physical parameters . Unauthorized receivers may acquire I/Q samples of the scrambled waveform but lack the dynamic parameter stream needed to restore a structured constellation before symbol decisions. Consequently, the effective secret space grows with transmission duration and symbol rate.

Research further notes that QEPS presents no structured algebraic surface at the physical layer akin to those targeted by analytical attacks in classical cryptography (e.g., linear or differential cryptanalysis). For eavesdroppers, meaningful data recovery requires establishing correct symbol decisions after QAM demapping—contingent on knowing time-dependent encryption parameters. Absent this knowledge, DSP chains yield essentially random outputs at demapping stages. Attacks thus reduce to exhaustive searches over continuously varying physical parameters, bounded by physical noise and measurement uncertainty rather than mathematical cryptanalysis.

In public-key configurations (QPKE), no static secret exists; security is enforced solely by physical impossibility of coherently demodulating phase-randomized signals without access to complete round-trip exchanges.

4.7. Assessment of Security Analysis in QEPS Literature

The security arguments reviewed here—centered on the phase synchronization barrier—are characteristic of physical-layer security approaches where protection stems from practical implementation constraints rather than abstract mathematical assumptions. While formal cryptographic proofs in reductionist frameworks remain less developed for QEPS compared to classical algorithms, the consistent experimental evidence across multiple studies provides strong operational validation. The demonstrated 50% BER for eavesdroppers across various modulation formats and channel conditions constitutes a direct, measurable security metric. Future research may seek to formalize these physical arguments within information-theoretic or computational models, but current literature establishes QEPS security through demonstrated physical denial of decoding capability—a distinct paradigm from traditional computational security.

4.8. Summary: The Phase Synchronization Barrier in Perspective

The phase synchronization barrier represents a distinct security primitive operating at the intersection of quantum optics and communication theory. It leverages quantum noise of coherent states and practical necessity of phase-synchronized local oscillators to create cryptographic obstruction. Research consistently shows this barrier is:

Physical rather than computational: Security stems from signal properties, not mathematical hardness.

Operationally validated: Eavesdroppers’ BER approaches 50% in experimental demonstrations.

Compatible with existing infrastructure: Implemented using standard coherent transceivers and DSP.

Inherently quantum-resistant: Immune to attacks from both classical and quantum computers, as it does not rely on computational assumptions vulnerable to quantum algorithms.

This distinguishes QEPS not only from classical digital encryption but also from other physical-layer approaches like chaotic encryption, which typically rely on synchronization mechanisms and computational hardness of reconstructing dynamics. By cryptographically controlling phase synchronization itself, QEPS establishes a robust security foundation for next-generation optical networks, as evidenced by the body of work reviewed herein.

5. Experimental Review

This section reviews the principal experimental demonstrations validating Quantum Encryption in Phase Space (QEPS) for coherent optical communications. Three main configurations are discussed: the quantum public key encryption (QPKE) implementation using QEPS-p in a round-trip architecture reported in CLEO and IPC proceedings [

14,

15], the phase-only symmetric encryption (QEPS-p) implementation reported in Scientific Reports [

13], and the displacement-operator encryption (QEPS-d) implementation reported in EPJ Quantum Technology [

18].

5.1. QPKE: Quantum Public Key Encryption via Round-Trip Architecture

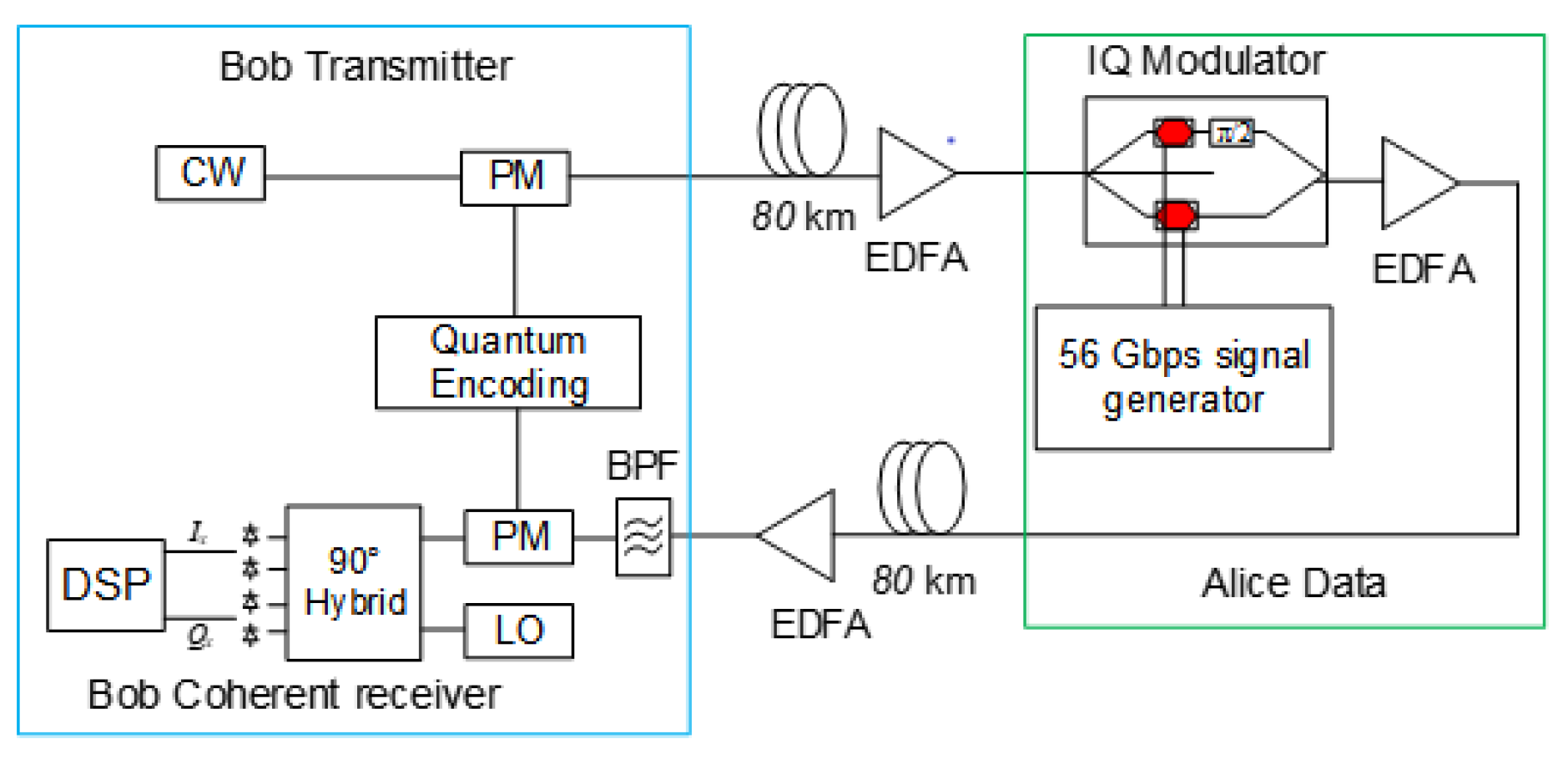

The QPKE implementation —a practical instantiation of the QEPS-p principle within a round-trip architecture— demonstrates public-key-like functionality at the physical layer using a round-trip architecture with QPSK modulation [

14,

15]. As illustrated in

Figure 2, this "pseudo-3-party" infrastructure eliminates the need for pre-shared symmetric keys while maintaining physical-layer security through a unique round-trip protocol:

The QPKE protocol operates as follows:

Bob (initiator) generates a random phase sequence using a Quantum Permutation Pad (QPP) and applies it to a continuous-wave (CW) laser via a phase modulator (PM), creating an encrypted "envelope" signal.

This phase-randomized carrier is transmitted to Alice over an 80 km standard single-mode fiber link with Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifier (EDFA) compensation.

Alice receives the scrambled carrier and modulates her secret data (at 56 Gbps) onto it using an IQ modulator, effectively "hiding" her information within Bob’s phase randomization without learning or storing the phase sequence.

The doubly-modulated signal returns to Bob over another 80 km link. Bob possesses the original phase sequence and applies the inverse phase transformation via synchronized QPP before coherent detection using a 90° hybrid and local oscillator, followed by digital signal processing (DSP).

The critical security insight is that Alice never learns Bob’s phase randomization, and an eavesdropper intercepting either the forward or return path sees only phase-randomized signals. Experimental validation at 200 Gb/s (QPSK over 80 km SMF) demonstrated that authorized communication between Bob and Alice achieves error-free performance, while eavesdroppers on either path experience BER near 50%.

Further security analysis in [

15] explored various eavesdropping scenarios, confirming that without access to the complete round-trip exchange and knowledge of the phase randomization, the system maintains robust physical-layer security. This QPKE implementation represents a significant departure from conventional encryption by enabling

public-key functionality without computational hardness assumptions, instead relying on the physical impossibility of coherently demodulating phase-randomized signals.

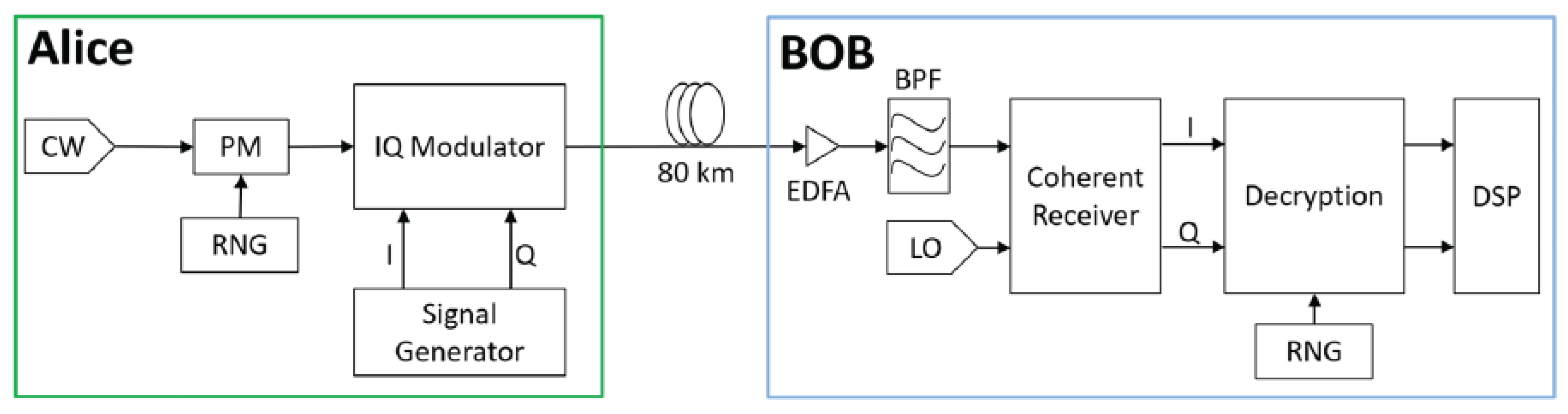

5.2. QEPS-p: Experimental Demonstration of Phase Mask Encryption

The QEPS-p experimental study presents the first systematic experimental validation of phase-based quantum encryption applied to classical coherent optical links using commercially available transceiver components [

13]. Building upon the QPKE concept, this work demonstrates the

symmetric key version of phase encryption where both transmitter and receiver share the same phase sequence.

Figure 3 (adapted from

Figure 2 of [

13]) illustrates the experimental implementation. At the transmitter (Alice), a continuous-wave (CW) laser is first modulated by a phase modulator (PM) driven by a deterministic pseudo-random sequence generated from a shared random number generator (RNG). The phase-encrypted optical carrier is then passed through an IQ modulator, which encodes the information-bearing in-phase (I) and quadrature (Q) symbols. The encrypted signal is transmitted over an 80 km standard single-mode fiber link.

At the receiver (Bob), coherent detection is performed using a local oscillator, after which the inverse phase operation—driven by the synchronized RNG—is applied before digital signal processing. This ordering is critical: only after decryption does the received signal recover a structured constellation suitable for carrier phase recovery and standard DSP, explicitly enforcing the DSP trust boundary described in

Section 4.

The experimental results, summarized in Figure 5 of [

13], demonstrate the security impact of phase masking on coherent reception. Using a 16-QAM modulation format, the study compares system performance with and without correct phase decryption. When the phase mask is unknown, the received constellation collapses into a rotationally symmetric ring structure, and carrier phase recovery algorithms fail to converge. As a result, the measured bit error rate (BER) at an unauthorized receiver approaches the random-guessing limit. In contrast, when the correct phase sequence is applied, the original QAM constellation is restored, and the authorized receiver achieves BER performance comparable to an unencrypted coherent link.

Additional experiments reported in [

13] extend these observations across multiple modulation formats, including 4-PSK, 16-PSK, and high-order QAM, under practical optical signal-to-noise ratios. In all cases, phase masking effectively denies stable phase synchronization to unauthorized receivers while preserving reliable communication for authorized users. These results experimentally confirm the core QEPS-p security principle: randomized phase encryption destroys the phase reference required for coherent DSP, thereby enforcing physical-layer security through a phase synchronization barrier.

5.3. QEPS-d: Experimental Validation Using Displacement Operator Encryption

Subsequent work experimentally validated the QEPS framework using random displacement operators rather than phase-only transformations. In "Experimental demonstration of quantum encryption in phase space with displacement operator in coherent optical communications," displacement operator encryption was applied to coherent states prior to modulation and transmission over a standard coherent optical link [

18]. The displacement operator technique (DOCS) randomizes both amplitude and phase by translating constellation points in the two-dimensional phase plane.

This implementation demonstrated that authorized users, with knowledge of the displacement operator parameters, can correctly undo the random displacements and recover the transmitted data with low BER. Unauthorized receivers, in contrast, experienced BER values close to 50% when any mismatch occurred in the displacement coefficients, amplitudes, or phases. The work also explored dual-polarization encryption, applying independent displacement operators to orthogonal polarizations to further increase randomness and resist eavesdropping [

18]. These experimental results support the premise that displacement-based encryption further diminishes residual structure in the encrypted signal’s phase space, reinforcing the physical-layer security afforded by the QEPS approach.

Together, these experimental investigations confirm that QEPS implementations can be integrated with existing coherent optical communication infrastructure and that both phase-only and displacement-based encryption effectively deny coherent phase recovery to unauthorized receivers. Security is evidenced by randomized measurement statistics and BER saturation near the random-guessing limit in the absence of the secret encryption parameters, consistent with the phase synchronization barrier described in

Section 4.

The progression from QPKE (public-key-like) to symmetric QEPS-p and finally to QEPS-d demonstrates the versatility and scalability of the QEPS framework, offering multiple deployment options ranging from key-agreement-free QPKE to high-security symmetric encryption with displacement operators.

5.4. Summary of Experimental Performance and Achievements

Table 1 summarizes the key performance metrics and security outcomes from the experimental demonstrations of QEPS variants reviewed in this section.

The experimental results collectively demonstrate that:

All QEPS variants successfully enforce a phase synchronization barrier at the physical layer, causing unauthorized receivers to experience a bit error rate (BER) near the theoretical maximum of 50%, equivalent to random guessing.

Authorized receivers with the correct secret (or, in the case of QPKE, with the ability to apply the inverse transformation) achieve BER performance comparable to unencrypted coherent links, typically below the forward error correction (FEC) threshold ( for hard-decision FEC).

The implementations support high-speed transmission (up to 200 Gb/s in experiments) over standard single-mode fiber spans of 80 km, confirming compatibility with existing optical infrastructure.

Security does not depend on computational complexity but on the physical-layer denial of a stable phase reference, making it inherently resistant to advances in computing power, including quantum computing.

The framework is versatile, supporting multiple cryptographic models: from public-key emulation (QPKE) that requires no pre-shared secret, to symmetric encryption (QEPS-p, QEPS-d) with enhanced randomness through displacement operators.

These experimental validations confirm that QEPS provides a practical, high-performance approach to physical-layer security for coherent optical communications, with security rooted in fundamental principles of quantum optics and coherent detection rather than in algorithmic complexity.

6. Conclusions

Quantum Encryption in Phase Space (QEPS) represents a transformative approach to securing optical communications by integrating cryptographic operations directly into the physical layer of coherent transmission systems. By exploiting the quantum-mechanical formalism of coherent states and unitary transformations, QEPS fundamentally redefines the security paradigm—shifting from reliance on computational complexity in the digital domain to enforcement of physical barriers in the analog domain. This review has systematically examined the theoretical foundations, security mechanisms, and experimental validations that establish QEPS as a viable and potent framework for next-generation optical security.

At its core, QEPS operates by applying randomized phase shifts, displacements, or combined dynamic operators to data-bearing coherent states before modulation, rendering the transmitted waveform indistinguishable from noise to any receiver lacking the precise inverse transformation. This mechanism disrupts the phase synchronization essential for coherent detection, creating what we term the phase synchronization barrier—a physical-layer obstruction that cannot be circumvented through computational means alone. The result is a cryptographic separation where authorized users achieve near-error-free communication, while eavesdroppers are relegated to bit-error rates approaching 50%, equivalent to random guessing.

The experimental progression from QPKE—a public-key-like round-trip protocol requiring no pre-shared secret—to symmetric QEPS-p and QEPS-d implementations demonstrates the framework’s adaptability and practicality. These demonstrations, conducted at data rates up to 200 Gb/s over 80 km of standard fiber, confirm that QEPS can be seamlessly integrated into existing coherent transceiver architectures without sacrificing performance or compatibility. Crucially, security does not degrade with advances in computing power, positioning QEPS as a future-proof solution in an era of evolving computational threats, including those posed by quantum computers.

Nevertheless, the transition from experimental validation to widespread deployment presents several salient challenges. Key among these is the establishment of a scalable and secure key distribution mechanism for high-speed symmetric QEPS implementations. This challenge is uniquely addressed within the QEPS framework itself through a layered security architecture. The round-trip QPKE protocol can first be employed as a physical-layer key establishment mechanism, enabling two parties to agree upon a shared secret without pre-shared keys or reliance on computational hardness. This agreed secret can then seed the generation of high-speed, symbol-by-symbol encryption sequences for a subsequent symmetric QEPS (p, d, or dd) data session. Alternatively, for environments where a public-key infrastructure is preferred, Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) algorithms can perform the initial key agreement, combining computational and physical-layer security. Additional challenges include comprehensive characterization of system performance under real-world channel impairments—such as nonlinearities and polarization effects—and the integration of QEPS within standardized optical transport ecosystems to ensure interoperability with conventional network protocols and management planes.

Looking forward, QEPS opens several promising directions for both theoretical and applied investigation. These include hybrid architectures that combine physical-layer encryption with higher-layer cryptographic protocols, extensions to other coherent transmission domains such as wireless and satellite communications, and the exploration of advanced modulation formats and error-correction schemes tailored to encrypted waveforms. The framework also invites deeper inquiry into the information-theoretic limits of physical-layer security and its interplay with channel capacity and noise resilience.

In conclusion, QEPS establishes a new frontier in optical security—one where protection is embedded not merely in bits, but in the very photons that carry them. By leveraging the principles of quantum optics to enforce security through physical denial rather than mathematical obfuscation, it offers a robust, efficient, and inherently quantum-resistant approach to safeguarding the optical infrastructure that underpins the global digital economy. As research advances toward higher speeds, longer distances, and network-scale demonstrations, QEPS is poised to become a cornerstone of secure optical communications in the decades to come.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of language AI tools, including Deepseek and Gemini, for language refinement and editorial assistance. Scientific analyses and conclusions remain the sole responsibility of the authors.

References

- Shor, P.W. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science; 1994; pp. 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, D.J. Introduction to post-quantum cryptography. Post-quantum cryptography 2009, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, F.G.; Long, G.L. Secure direct communication with a quantum one-time pad. Phys. Rev. A 2004, 69, 052319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, G.l.; Deng, F.g.; Wang, C.; Li, X.h.; Wen, K.; Wang, W.y. Quantum secure direct communication and deterministic secure quantum communication. Frontiers of Physics in China 2007, 2, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Deng, F.G.; Li, Y.S.; Liu, X.S.; Long, G.L. Quantum secure direct communication with high-dimension quantum superdense coding. Phys. Rev. A 2005, 71, 044305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.B.; Zhou, L.; Long, G.L. One-step quantum secure direct communication. Science Bulletin 2022, 67, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Sheng, Y.; Niu, P.; Yin, L.; Long, G.; Hanzo, L. Measurement-device-independent quantum secure direct communication. Science China Physics, Mechanics, and Astronomy 2020, arXiv:quant63, 230362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Liu, Y.C.; Niu, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, F.; Wang, M.; Song, X.T.; Chen, X.; Zheng, C.; Long, G.L. Simultaneous transmission of information and key exchange using the same photonic quantum states. Science Advances 2025, 11, eadt4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glauber, R.J. Coherent and incoherent states of the radiation field. Physical Review 1963, 131, 2766–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, R.; Bettenburg, N. Quantum Public Key Distribution using Randomized Glauber States. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE), 2020; pp. 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Khalil, M.; Shahriar, K.A.; Chen, L.R.; Plant, D.V.; Kuang, R. Security Analysis of a Next Generation TF-QKD for Secure Public Key Distribution with Coherent Detection over Classical Optical Fiber Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), 2021; pp. 416–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Chan, A.; Shahriar, K.A.; Chen, L.R.; Plant, D.V.; Kuang, R. Security Performance of Public Key Distribution in Coherent Optical Communications Links. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Computer Communication and the Internet (ICCCI), 2021; pp. 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Khalil, M.; Shahriar, K.A.; Plant, D.V.; Chen, L.R.; Kuang, R. Encryption in Phase Space for Classical Coherent Optical Communications. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 12965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, K.A.; Khalil, M.; Chan, A.; Chen, L.R.; Kuang, R.; Plant, D.V. Physical-Layer Secure Optical Communication Based on Randomized Phase Space in Pseudo-3-Party Infrastructure. In Proceedings of the Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics, 2022; Optica Publishing Group; p. SF4L.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahriar, K.A.; Khalil, M.; Chan, A.; Chen, L.R.; Kuang, R.; Plant, D.V. Security Performance of Physical-Layer Encryption Based on Randomized Phase Space in Optical Fiber Communication. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Photonics Conference (IPC), 2022; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, R.; Chan, A. Quantum encryption in phase space with displacement operators. EPJ Quantum Technology 2023, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, R. Quantum Encryption in Phase Space Uing Displacement Operator for QPSK Data Modulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 8th International Conference on Systems, Control and Communications, New York, NY, USA, 2024; ICSCC ’23, pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Chan, A.; Chen, L.R.; Plant, D.V.; Kuang, R. Quantum-Inspired Encryption Using Displacement Operators in Coherent Optical Communications. In Proceedings of the Advanced Photonics Congress 2024, 2024; Optica Publishing Group; p. SpW2H.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Kuang, R.; Wen, K.; et al. Toward Practical Quantum Encryption in Phase Space: Simulated QPSK and 16-QAM with Dynamic Displacement Operators. Research Square;Preprint 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, R. Quantum encryption in phase space with dynamic displacement operators and quantum permutation pad. Academia Quantum 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, H.; Dong, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X. Partially coherent optical chip enables physical-layer public-key encryption. Opto-Electron Adv 2025, 8, 250098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, H.; Deng, L.; Yang, Q.; Dai, X.; Liu, D.; Gao, X.; Yu, Y.; Cheng, M. 100Gb/s coherent optical secure communication over 1000 km based on analog-digital hybrid chaos. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 33200–33211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Xu, Z.; Gao, C.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhang, X.; Xi, L.; Xu, H.; Bai, C. Physical layer encryption for coherent PDM system based on polarization perturbations using a digital optical polarization scrambler. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 26791–26806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Gong, X.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, W.; Hou, W.; Guo, L. High-speed coherent optical encryption/decryption system based on cross-phase encoding. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 33021–33032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Gu, W.; Deng, Z.; Li, X.; Ye, J.; An, Y.; Bi, S.; Wang, A.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; et al. 40 Gb/s Secure Coherent Optical Communication Based on Electro-Optic Phase Feedback Encryption. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 2024, 36, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.H.; Ouyang, Y.; Rohde, P.P. Practical somewhat-secure quantum somewhat-homomorphic encryption with coherent states. Physical Review A 2018, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Dong, Z.; Zhu, Y.M.; Peng, D.M.; Wang, Y.K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhu, W.Q.; Li, D.Z.; Liu, X.L. Three-channel robust optical encryption via engineering coherence Stokes vector of partially coherent light. PhotoniX 2024, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larger, L.; Goedgebuer, J.P. Encryption using chaotic dynamics for optical telecommunications. Comptes Rendus Physique 2004, 5, 609–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Mao, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, R.; Wang, L.; Jia, Z.; Li, P.; Wang, A.; Wang, Y. Optical Chaos Generation and Applications. Advanced Photonics Research 2025, 6, 2500055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Wang, H.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, Y. Ultra-wideband chaotic optical communication based on electro-optic differential feedback loop. Optics Communications 2023, 545, 129729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Yang, Z.; Shi, M.; Zhuge, Q.; Hu, W.; Yi, L. 100 Gb/s coherent chaotic optical communication over 800 km fiber transmission via advanced digital signal processing. Advanced Photonics Nexus 2024, 3, 016003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo, A.; Soriano, M.C.; Mirasso, C.R.; Colet, P. Chaos-Based Optical Communications: Encryption Versus Nonlinear Filtering. IEEE Journal of Quantum Electronics 2010, 46, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakidis, D.; Argyris, A.; Bogris, A.; Syvridis, D. Influence of the decoding process on the performance of chaos encrypted optical communication systems. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2006, 24, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Gao, X.; Li, X.; Yang, H.; An, Y.; Xu, P.; Wang, A.; Dong, X.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Y.; et al. Physical layer security–enhanced optical communication based on chaos masking and chaotic hardware encryption. Optics Express 2024, 32, 27734–27747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Ji, Y. Chaotic optical communication decryption framework based on the conv-transformer model. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 44071–44086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Mao, X.; Wang, L.; Fu, S.; Wang, A.; Wang, Y. Improving decryption quality of optical chaos communication using neural networks. Opt. Lett. 2024, 49, 4445–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaminga, S.; Martinez, A.; Huang, H.; Rontani, D.; Morichetti, F.; Melloni, A.; Grillot, F. Optical chaotic signal recovery in turbulent environments using a programmable optical processor. Light: Science & Applications 2025, 14, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Pu, M.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, M.; Chen, S.; Qiu, K.; Jiang, N.; Luo, X. Experimental demonstration of an 8-Gbit/s free-space secure optical communication link using all-optical chaos modulation. Optics Letters 2023, 48, 1470–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.Y.; Zhou, X.F.; Li, Q.L.; Hu, M.; Li, H.Z. Secondary-encryption optical chaotic communication system based on one driving laser and two responding lasers. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2022, 163, 112554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Xia, Y.; Chen, W.; Gu, P.; Zhang, Z. Physical-layer security of optical communication based on chaotic optical encryption without an additional driving signal. Optics Letters 2023, 48, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.W.A.; Singh, A.R.; Pandian, A.; Bajaj, M.; Zaitsev, I.; Rathore, R.S. Enhancing network security with hybrid feedback systems in chaotic optical communication. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 24958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Song, L. Optical chaotic secure algorithm based on space laser communication. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems - S 2019, 12, 1355–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, R. Quantum Permutation Pad for Quantum Secure Symmetric and Asymmetric Cryptography. Academia Quantum 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M.G. Coherent Detection for Fiber Optic Communications Using Digital Signal Processing. In Proceedings of the Optical Amplifiers and Their Applications/Coherent Optical Technologies and Applications; Optica Publishing Group, 2006; p. CThB1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yu, J. Digital signal processing for coherent optical communication. In Proceedings of the 2009 18th Annual Wireless and Optical Communications Conference, 2009; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, T. Advanced DSP for Coherent Optical Fiber Communication. Applied Sciences 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Plant, D.V.; Chan, A.; Chen, L.R.; Kuang, R. Experimental demonstration of quantum encryption in phase space with displacement operator in coherent optical communications. EPJ Quantum Technology 2024, 11, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, R.; Barbeau, M. Quantum Permutation Pad for Universal Quantum-Safe Cryptography. Quantum Information Processing 2022, 21, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |