1. Introduction

The arrival of quantum computing marks one of the most significant paradigm shifts in computational science since the invention of the classical transistor. Unlike classical bits, quantum bits— or qubits— possess the dual abilities of superposition and entanglement, allowing them to process information in states that are combinations of both 0 and 1. This feature enables quantum devices to explore solution spaces in ways that classical computers cannot, challenging the very foundations of modern digital security.

Public-key cryptographic systems, notably RSA and Elliptic-Curve Cryptography (ECC), underpin secure communications, electronic commerce, and data confidentiality across the globe. RSA’s security relies on the presumed hardness of factoring large composite integers, while ECC’s depends on the intractability of the elliptic-curve discrete logarithm problem. Over decades, rigorous analyses and empirical benchmarks have placed the best-known classical algorithms for these tasks firmly in the sub- exponential complexity class, rendering keys of size 2048 bits (RSA) or 256 bits (ECC) effectively unbreakable by classical devices for centuries to come.

This security paradigm changed significantly in 1994 when Peter Shor introduced a polynomial-time quantum algorithm for integer factorization and discrete logarithms, showing that a sufficiently large and error-corrected quantum computer could break RSA and ECC in practical time frames [

3]. Soon after, Grover’s algorithm demonstrated how to quadratically speed up brute-force searches, reducing the effective key length of Symmetric ciphers like AES [

4]. Together, these algorithms transformed quantum computing from a theoretical curiosity into a genuine threat to classical cryptography. In recent years, experimental progress has accelerated significantly: superconducting qubit arrays now exceed 100 physical qubits [

5], and ion-trap systems achieve coherence times sufficient for meaningful circuit execution. Coupled with advances in quantum error correction—especially surface-code architectures—researchers expect fault-tolerant quantum machines within the next decade. If realized, such machines could run Shor’s algorithm to factor RSA-2048 in hours or days instead of millennia, and use Grover’s search to break symmetric keys much faster than expected [

10,

11]. This paper offers a thorough mathematical analysis of Shor’s and Grover’s algorithms, explaining their resource needs and comparing them to the fastest classical methods. We expand the literature review to include both foundational complexity results and the latest resource estimates under realistic error-correction overheads. In the Development section, we derive accurate asymptotic formulas, show numerical simulations, and illustrate the performance gap visually. Finally, in an expanded Discussion, we explore mitigation strategies—lattice-based, code-based, multivariate, and hash-based schemes—assess their security margins, and suggest practical pathways for migration through standardization processes.

2.1. Quantum Complexity Foundations

Bernstein and Vazirani formalized the quantum complexity class BQP, establishing relationships with classical classes: P ⊆ BQP ⊆ PSPACE [

6]. Shor’s 1994 algorithm leveraged the Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT) to solve period-finding in O(poly(n)) time, proving that integer factorization and discrete logarithm lie in BQP [

3]. Subsequent lower-bound analyses by Beals et al. revealed that certain problems resist exponential quantum speed-ups, delimiting the scope of quantum advantage [

7]. Brassard, Høyer, and Tapp extended these results to hash functions, quantifying how Grover’s algorithm degrades collision resistance from O(2n/2) to O(2n/3) under specific quantum random oracle models [

8].

2.2. Resource Estimates for Quantum Attacks

Initial resource assessments—Beauregard’s circuit for 2n + 3 qubits and O(n3) gate complexity— offered optimistic lower bounds but neglected error correction [

9]. Fowler et al. incorporated surface- code overhead, showing that physical qubit requirements inflate by two orders of magnitude and runtime by an order of magnitude to achieve logical error rates < 10−15 [

10]. Gidney and Ekerå’s 2022 study refined these numbers, estimating ~20 million noisy qubits and ~8 hours to factor a 2048-bit RSA modulus on a realistic noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) device [

11].

2.3. Emergence of Post-Quantum Schemes

Pre-quantum work by McEliece (1978) introduced code-based cryptography, relying on the hardness of decoding random linear codes [

12]. In 1998, Hoffstein et al. proposed NTRU, a ring-based lattice scheme, later formalized via the Learning With Errors (LWE) framework by Regev in 2005 [

13,

14]. Multivariate quadratic schemes (Oil–Vinegar, Rainbow) emerged in the mid-2000s but faced algebraic attacks that necessitated parameter adjustments [

15,

16]. Hash-based signature schemes (XMSS, LMS) offered provable security under collision resistance, suitable for forward-secure signature requirements [

17]. Survey papers by Buchmann & Ding and Katz & Lindell compare these families on public-key sizes, computational costs, and security reductions [

18,

19].

2.4. Standardization Initiatives

NIST’s PQC standardization process, launched in 2016, progressed through three selection rounds, culminating in finalists: Crystals-Kyber, Crystals-Dilithium, Classic McEliece, Rainbow, and SPHINCS+ [

20,

21]. Draft standards are expected by 2025, with finalization by 2027 [

22]. The European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) and industry consortia publish complementary guidelines and interoperability tests to accelerate adoption [

23].

3. Mathematical Development

In this section, we detail the mathematical underpinnings of classical and quantum cryptanalysis algorithms, derive asymptotic complexities, and provide numerical illustrations4. Discussion

Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

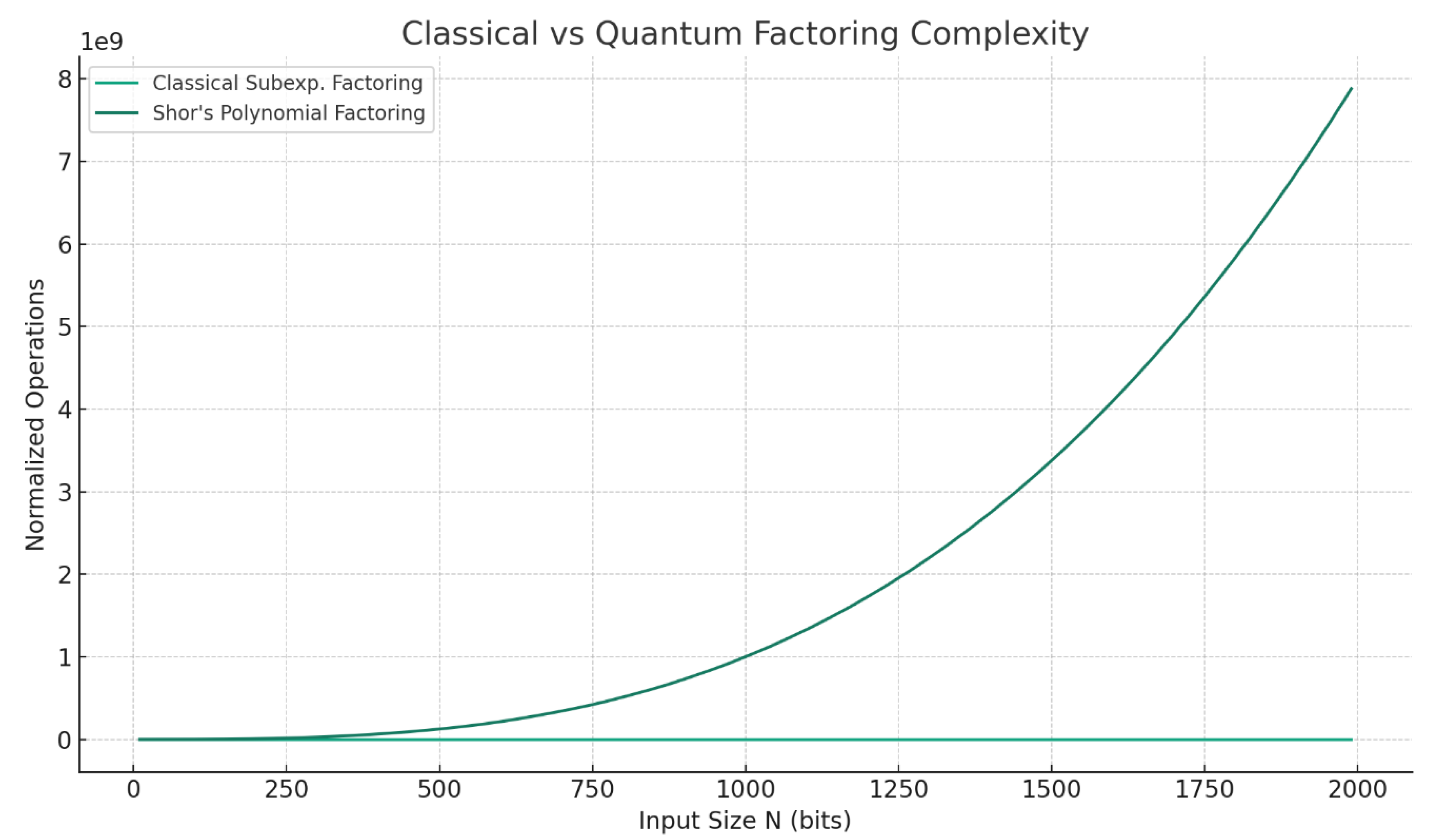

3.1. Classical Subexponential Factorization

The General Number Field Sieve (GNFS) achieves complexity

where c = (64/9)1/3 ≈ 1.92 [

2]. Incorporating lower-order terms yields

For N = 22048, numerical substitution gives TGNFS ≈ 10154 classical operations, infeasible with current supercomputing resources.

3.2. Shor’s Algorithm: Quantum Polynomial Factoring

Shor’s algorithm factors N by mapping to the period-finding problem:

Initialize registers: ∣0⟩⊗2n∣0⟩⊗n. 2n

Create superposition: 1 ∑2 −1 ∣x⟩∣0⟩.

Apply modular exponentiation to obtain ∣x⟩∣ax mod N ⟩ using O(n3) gates [

9].

Perform inverse QFT on the first register in O(n2 log n log log n) depth [

8].

Measure to estimate k/r, extract r via continued fractions, and compute gcd(ar/2 ± 1, N ) to find factors.

Gate complexity: O(n3) for modular exponentiation and O(n2 log n log log n) for QFT. Surface-code error correction imposes a logical-to-physical qubit ratio of O(d2) with d ≈ 30 for desired error rates, implying ~900 physical qubits per logical qubit [

10].

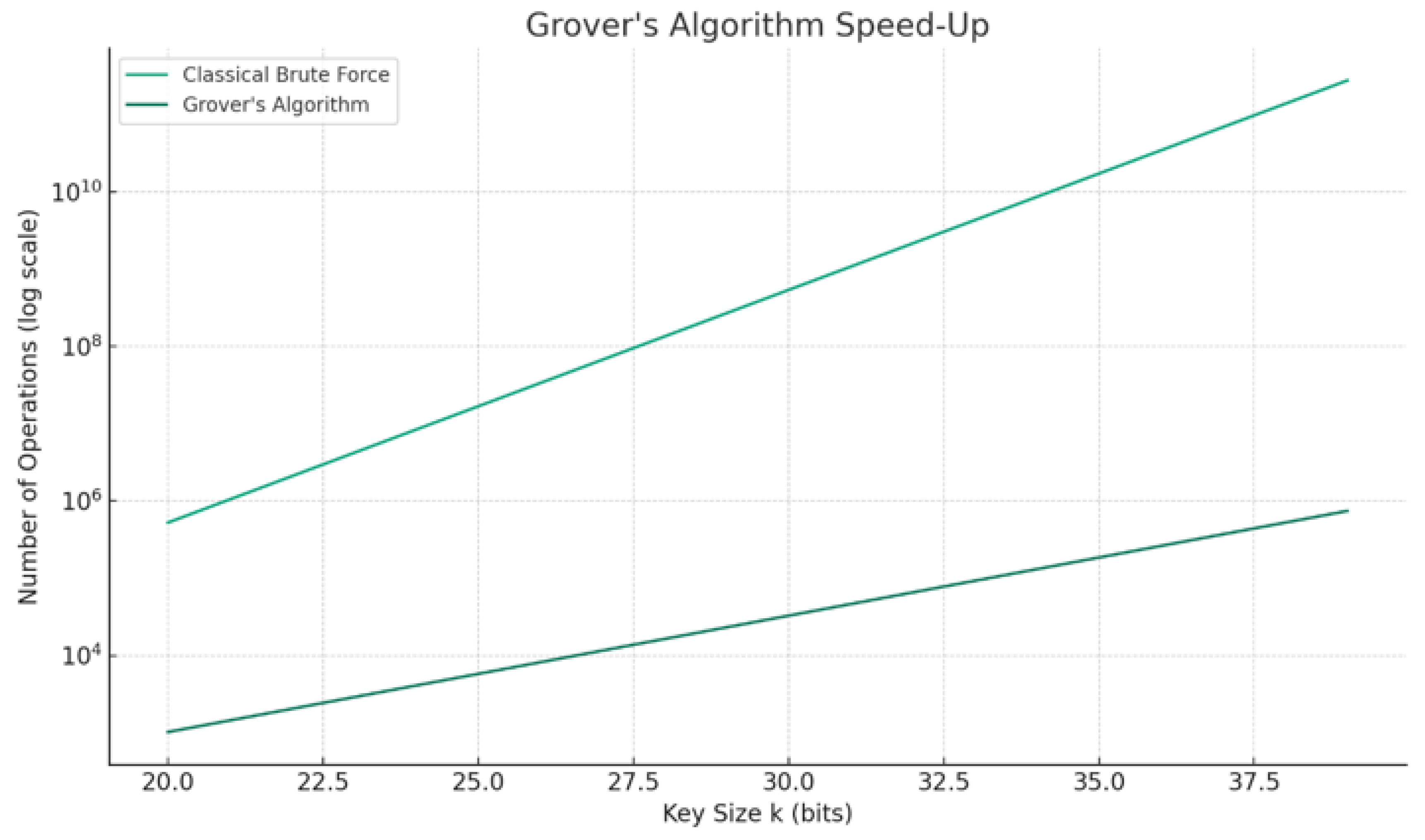

3.3. Grover’s Algorithm: Quadratic Speed-Up for Key Search

Given an unstructured search space of size M = 2n, Grover’s algorithm reduces search to O(M) = O(2n/2) oracle calls [

4]. The amplitude amplification process iterates the Grover operator G k times, where k ≈ π/4, to maximize success probability sin2((2k + 1)θ) with θ = arcsin(2−n/2) arcsin(2

−n/2).

To preserve a 128-bit security level against quantum adversaries, symmetric key lengths must double to 256 bits, as 2256/2 = 2128.

3.4. Qubit Representation and Error Correction Overhead A qubit state resides on the Bloch sphere:

2 2

Surface-code error correction encodes one logical qubit into d2 physical qubits; for logical error < 10−15, d ≈ 30 yields ~900 physical qubits per logical qubit [

10]. Factoring RSA-2048 (~4\,000 logical qubits) requires ~3.6 million physical qubits.

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 illustrate complexity scaling for factoring and key search, respectively.

4. Discussion

The rapid development of quantum hardware and software requires a similarly quick response in cryptographic research and implementation. The following discussion explores post-quantum defenses through practical perspectives—algorithm maturity, deployment issues, and societal effects. As quantum processors near fault tolerance, organizations must envision a future where classical cryptosystems become vulnerable quickly. The transition is neither purely technical nor instant; it demands coordinated efforts across research, engineering, policy, and education. Lattice-based cryptography is notable for its combination of strong security assumptions and practical performance. Schemes like Crystals-Kyber (for key encapsulation) and Crystals-Dilithium (for digital signatures) rely on the difficulty of the Learning With Errors (LWE) problem and feature small key sizes (~1–2 KB) and moderate computational costs [

21,25]. Their implementations integrate smoothly into existing protocols (TLS, SSH), supported by open-source libraries for cross-platform deployment. A key factor in their adoption is the strong reduction from worst-case lattice problems to average-case instances, providing formal security guarantees even against quantum attackers [

14,26]. Code-based cryptography, especially Classic McEliece, offers long-standing security: the decoding problem for Goppa codes has resisted classical and quantum attacks for over 40 years [

12,27]. However, its public keys—often several megabytes—pose significant challenges for memory-limited environments and bandwidth-restricted applications. Researchers are exploring hybrid models that combine lattice-based key exchange with code-based encryption to balance key size and maintain quantum resistance [28]. Multivariate quadratic schemes, like Rainbow, are attractive due to small signature sizes and quick signing processes [

15]. Nevertheless, their security has been weakened by successive algebraic attacks that exploit structural flaws [

16,29]. Current efforts aim to develop multivariate families with provable hardness, possibly by embedding perturbation mechanisms or investigating new algebraic structures less susceptible to Groebner-basis acceleration.

Hash-based signatures, exemplified by SPHINCS+, depend solely on cryptographic hash functions, requiring no assumptions other than collision resistance [

17,30]. Although signature sizes (~40 KB) are larger compared to other schemes, their security reductions are straightforward and based on well-established hash constructions. This simplicity makes hash-based signatures especially suitable for constrained devices and high-security environments where minimal reliance on new number-theoretic assumptions is preferred.

Beyond choosing algorithms, the migration process involves extensive interoperability testing, updates to network and firmware stacks, and rigorous verification of randomness sources. Standards organizations (NIST, ETSI) require certification frameworks to ensure developers adhere to security and performance standards [

22,

23]. Training in new primitives, expanding quality assurance processes to include post-quantum parameters, and regulatory deadlines to speed up adoption in sectors like finance, healthcare, and government are also necessary.

Most importantly, the human aspect—awareness, governance, and risk management—will influence the success of this transition. Organizations should perform quantum risk assessments, create hybrid deployment strategies combining classical and quantum-resistant algorithms, and prepare incident response plans for cryptographic failures. Collaboration between academia, industry, and government is vital to share expertise, exchange threat intelligence, and develop standardization roadmaps.

5. Conclusions

Quantum computing is set to undermine the cryptographic foundations of modern digital security. Our mathematical analysis demonstrates the significant reduction in complexity enabled by Shor’s and Grover’s algorithms, and our narrative underscores the urgent need for a coordinated shift to post-quantum schemes. Lattice-, code-, multivariate-, and hash-based cryptography provide workable defenses; hybrid transition strategies and international standardization efforts are already underway. To protect global data, stakeholders must begin migration planning immediately—balancing technical accuracy with organizational readiness—to ensure a secure digital future in the quantum era.

Funding

This research was funded by VIC Project from European Comission, GA no. 101226225.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- K. Lenstra and H. W. Lenstra Jr., “The development of the number field sieve,” LNCS, vol. 1554, pp. 11–42, 1993.

- J. M. Pollard, “The complexity of the Rho method for factoring,” Math. Comput., vol. 32, no. 143, pp. 918–924, 1978.

- Shor, P.W. Algorithms for Quantum Computation: Discrete Logarithms and Factoring. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundation of Computer Science, Washington, DC, USA, 20–22 November 1994; pp. 124–134. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, L.K. A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on the Theory of Computing, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 22–24 May 1996; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. M. Arute et al., “Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor,” Nature, vol. 574, pp. 505–510, 2019.

- E. Bernstein and U. Vazirani, “Quantum complexity theory,” SIAM J. Comput., vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1411– 1473, 1997.

- D. Beals et al., “Quantum lower bounds by polynomials,” J. ACM, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 778–797, 2001.

- G. Brassard, P. G. Brassard, P. Høyer, and A. Tapp, “Quantum cryptanalysis of hash functions,” ACM SIGACT News, vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 14–19, 1997.

- Beauregard, “Circuit for Shor’s algorithm using 2n + 3 qubits,” Quantum Inf. Comput., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 175–185, 2003.

- Fowler, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Surface-code implementation of Shor’s algorithm,” Phys. Rev. Lett., vol. 115, no. 3, 2025.

- Gidney and, M. Ekerå, “Factoring RSA-2048 in 8 hours using 20 million noisy qubits,” Quantum, vol. 6, 2022.

- R. J. McEliece, “A public-key cryptosystem based on algebraic coding theory,” DSN Prog. Rep. 44, pp. 114–116, 1978.

- J. Hoffstein et al., “NTRU: A ring-based cryptosystem,” in ANTS ’98, LNCS 1423, pp. 267–288, 1998.

- O. Regev, “On lattices, LWE, and cryptography,” J. ACM, vol. 56, no. 6, 2009.

- J. Ding and D. Schmidt, “Rainbow: A multivariate signature scheme,” in ACNS 2005, LNCS 3531, pp. 164–175, 2005.

- H. Kipnis and A. Shamir, “Cryptanalysis of Oil–Vinegar,” in EUROCRYPT ’99, LNCS 1592, pp. 257–271, 1999.

- Hühnlein et al., “XMSS—A forward secure signature,” in PQC ’15, 2015.

- W. Buchmann and J. Ding, “Post-quantum cryptography,” AAECC, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 19–45, 2008.

- J. Katz and Y. Lindell, Introduction to Modern Cryptography, 3rd ed., CRC Press, 2020. NIST, “PQC Standardization,” Feb. 2016.

- D. J. Bernstein et al., “Crystals-Kyber: Round 3 submission,” 2020. NIST, “PQC Plans,” Apr. 2022.

- ETSI, “Quantum-Safe Cryptography,” Mar. 2023.

- J. Alkim et al., “NewHope: Lattice KEX,” USENIX Sec., 2016.

- P. Schwabe, “Crystals-Dilithium performance,” IACR HES, 2022P. Schwabe, “Crystals-Dilithium performance,” IACR HES, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).