Submitted:

06 January 2026

Posted:

07 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

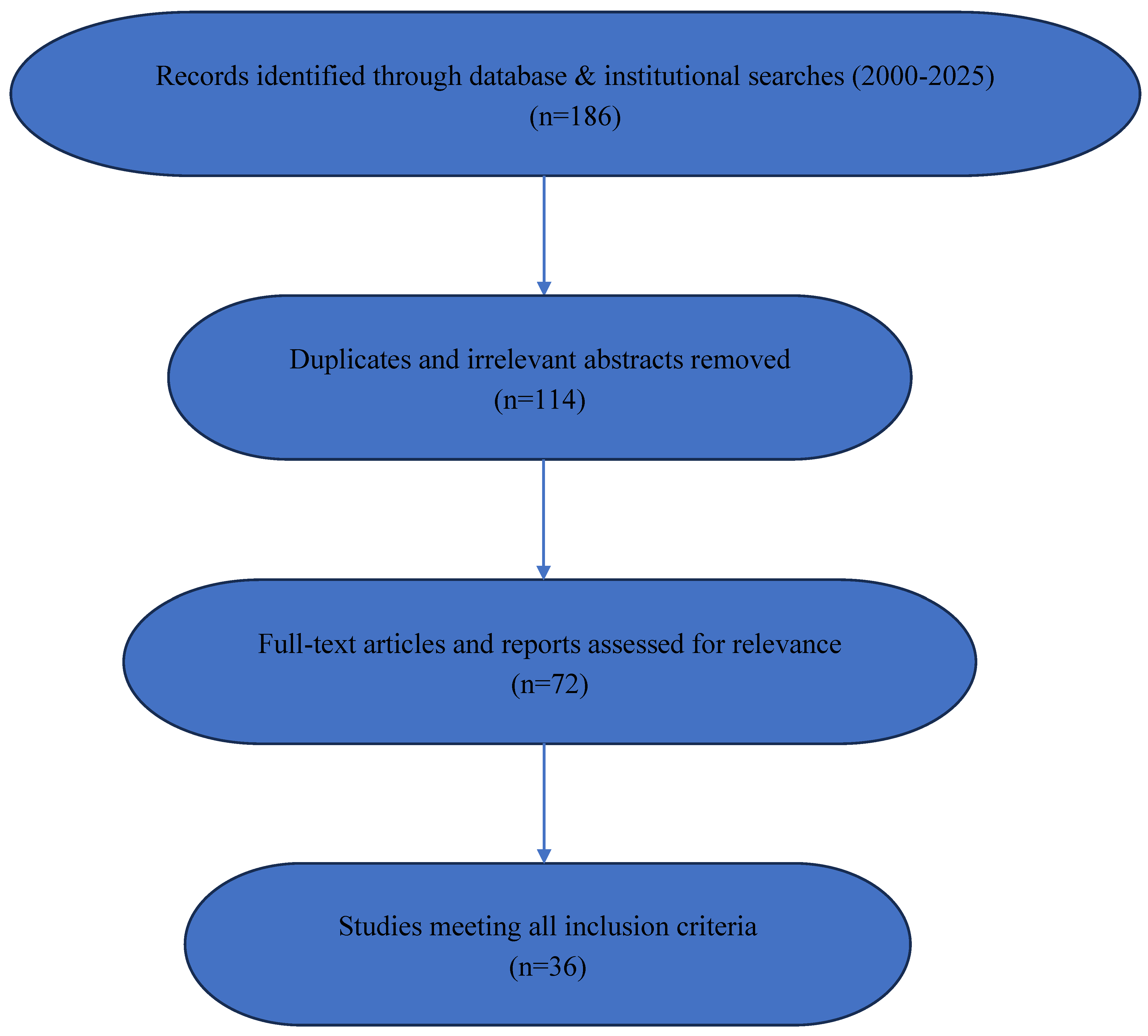

Material and Method

Results

Archive Demographics

Ecological-Justice Discourse

Displacement Discourse

Criminal-Economy Discourse

Active and Passive Discourses of Resource Governance

Who Controls the Resources?

The Community’s Voice

Discussion

Conclusion

Appendix A. Literature Included in the Scoping Review (1999–2025).

| Author(s) and Year | Title / Report | Source / Publisher | Type | |

| 1 | Ojewale (2025) | Undermining Peace: Banditry, Gold, and Elite Collusion in Northwest Nigeria | Deviant Behavior | Peer-Reviewed Journal |

| 2 | Kleffmann et al. (2024) | Banditry Violence in Nigeria’s Northwest: Insights from Affected Communities | UNIDIR | IGO Report |

| 3 | NEWC (2025) | Blood and Treasure Report | Office for Strategic Preparedness and Resilience | Government Report |

| 4 | Ogbonnaya (2020) | Illegal Mining and Rural Banditry in North West Nigeria | Policy Brief | Policy Report |

| 5 | Ikelegbe (2006) | The Economy of Conflict in the Oil-Rich Niger Delta | Nordic Journal of African Studies | Journal Article |

| 6 | Watts (2010) | Resource Curse? Governmentality, Oil and Power in the Niger Delta | Geopolitics | Journal Article |

| 7 | Akinola (2018) | Globalization, Democracy and Oil Sector Reform in Nigeria | Palgrave Macmillan | Book |

| 8 | Aderonmu (2010) | Rural Poverty Alleviation and Democracy in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic | Current Research Journal of Social Science | Journal Article |

| 9 | Awodezi & Mohammed (2023) | Oil Pipelines Vandalism and Oil Theft: Security Threat to Nigerian Economy and Environment | Journal of Environmental Law and Policy | Journal Article |

| 10 | Ijere (2015) | The Resource Curse in Nigeria: Lessons and Policy Options | Int. J. of Research in Humanities and Social Studies | Journal Article |

| 11 | Azgaku & Osuala (2015) |

The Socio-Economic Effects of Colonial Tin Mining on the Jos Plateau (1904–1960) |

Developing Country Studies | Journal Article |

| 12 | James, Olaniyi, & Olatubosun (2022) | Investigating the Environmental Sustainability Issues of Oil and Gas Operations in the Niger Delta | Sustainable Energy and Allied Disciplines | Journal Article |

| 13 | Klieman (2012) | U.S. Oil Companies, the Nigerian Civil War, and the Origins of Opacity | Journal of American History | Journal Article |

| 14 | Ogunsola (2023) | Cost of Governance and Economic Development in Nigeria | Journal of Business Management & Accounting | Journal Article |

| 15 | African Liberty (2019) | Nigerian Lawmakers Are Eating the Country’s Wealth with Insane Allowances | African Liberty | NGO/Media Source |

| 16 | Stober (2018) | Nigeria’s Senators and Their Jumbo Pay | ResearchGate | Commentary |

| 17 | African Union (2024) | Enhancing Mechanisms for Curbing Illegal Exploitation of Natural Resources | AU Commission | IGO Report |

| 18 | UN Security Council (2022) | Proceeds from Exploitation and Terrorism Financing | United Nations | IGO Report |

| 19 | NRGI (2015) | The Resource Curse Revisited | Natural Resource Governance Institute | Policy Report |

| 20 | African Security Sector Network (2023) | Youth, Violence, Exclusion and Injustice | ASSN | Regional Policy Report |

| 21 | Gandu (2012) | Analytical Basis for Botswana’s Diamond-Enclave Growth: Lessons for Nigeria | Research Paper | Comparative Study |

| 22 | NEITI (2022a) | Oil and Gas Industry Audit Report | Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative | National Report |

| 23 | NEITI (2022b) | Solid Minerals Industry Report | Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative | National Report |

| 24 | PAGMI (2021) | Framework and Progress Report | Presidential Artisanal Gold Mining Development Initiative | National Report |

| 25 | MMSD (2016) | Roadmap for the Growth and Development of the Nigerian Mining Industry | Federal Ministry of Mines & Steel Development | Policy Document |

| 26 | NDDC (2004) | Niger Delta Regional Development Master Plan | Niger Delta Development Commission | Development Plan |

| 27 | NOSDRA (2020) | Annual Oil Spill Data Report | National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency | Environmental Report |

| 28 | NEITI–EITI (2019) | Nigeria EITI Validation Report | Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative | Validation Report |

| 29 | NUPRC (2023) | Annual Report | Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission | Annual Report |

| 30 | Kyowe et al. (2024) | Index of heavy metal pollution and health risk assessment with respect to artisanal gold mining operations in Ibodi-Ijesa, Southwest Nigeria | Journal of Trace Elements and Minerals | Journal Article |

| 31 | International Crisis Group (2022) | Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem | ICG | Conflict Report |

| 32 | Amnesty International (2009) | Nigeria: Petroleum, Pollution and Poverty in the Niger Delta | Amnesty International | NGO Report |

| 33 | Human Rights Watch (1999) | The Price of Oil: Corporate Responsibility and Human Rights Violations in Nigeria | HRW | NGO Report |

| 34 | Amos (2025) | Digging into the Future | ATHENA Centre (Nigeria) | Policy Report |

| 35 | World Bank (2011) | World Development Report: Conflict, Security and Development | World Bank | Global Report |

| 36 | AfDB | Africa’s natural resources: The paradox of plenty | African Development Bank | Report |

References

- Abbink, J. Being young in Africa: The politics of despair and renewal. In Vanguard or vandals: Youth, politics and conflict in Africa; Abbink, J., van Kessel, I., Eds.; Brill, 2005; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ajide, K. B.; Alimi, O. Y. Environmental impact of natural resources on terrorism in Africa. Resources Policy 2021, 73, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderonmu, Jonathan. Rural Poverty Alleviation and Democracy in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic (1999-2009). Current Research Journal of Social Science 2010. [Google Scholar]

- African Development Bank. (2007). Africa’s natural resources: The paradox of plenty (Chap. 4). In African development report 2007 (pp. 96–138). African Development Bank Group. https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/documents/publications/(e)%20africanbank%202007%20ch4.pdf.

- African Security Sector Network. (2023). Youth, Violence, Exclusion and Injustice: Knowledge and Lessons Learnt from Africa for Positioning Inclusive Democratic Governance. https://www.africansecuritynetwork.org/.

- African Union. Discussion on enhancing mechanisms for curbing illegal exploitation of natural resources by armed and terrorist groups. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Akinola, A.O. The Structure and Nature of the Nigerian State. In Globalization, Democracy and Oil Sector Reform in Nigeria. African Histories and Modernities; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avtar, R.; Kouser, A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, D.; Misra, P.; Gupta, A.; Yunus, A. P.; Kumar, P.; Johnson, B. A.; Dasgupta, R.; Sahu, N.; Besse Rimba, A. Remote Sensing for International Peace and Security: Its Role and Implications. Remote Sensing 2021, 13(3), 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awodezi, H.; Mohammed, S. U. Oil pipelines vandalism and oil theft: Security threat to Nigerian economy and environment. Journal of Environmental Law and Policy 2023, 3(1), 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrighi, G. The long twentieth century: Money, power, and the origins of our times; Verso, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Alumona, I.M.; Azom, S.N. Politics of Identity and the Crisis of Nation-Building in Africa. In The Palgrave Handbook of African Politics, Governance and Development; Oloruntoba, S., Falola, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autesserre, S. The trouble with the Congo: Local violence and the failure of international peacebuilding; Cambridge University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Auty, R.M. Sustaining Development in Mineral Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis. Routledge, London, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Azgaku, C. B. A.; Osuala, U. S. The socio-economic effects of colonial tin mining on the Jos-Plateau: 1904-- 1960. Developing Country Studies 2015, 15 5(14). [Google Scholar]

- Badeeb, R. A.; Lean, H. H.; Clark, J. The evolution of the natural resource curse thesis: A critical literature survey. Resources Policy 51 2017, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boege, V.; Brown, A.; Clements, K. Hybrid political orders, not fragile states: State formation in the context of ‘fragility’; Berghof Research Center for Constructive Conflict Management: Berlin, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bunker, Stephen G.; Ciccantell, Paul S. Globalization and the Race for Resources; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bunker, Stephen G.; Ciccantell, Paul S. East Asia and the Global Economy: Japan’s Ascent, with Implications for China’s Future; The Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cederman, L.; Wimmer, A.; Min, B. Why Do Ethnic Groups Rebel?: New Data and Analysis. World Politics 2010, 62(1), 87–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charou, E.; Stefouli, M.; Dimitrakopoulos, D.; et al. Using Remote Sensing to Assess Impact of Mining Activities on Land and Water Resources. Mine Water Environ 2010, 29, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, P.; Hoeffler, A. Resource Rents, Governance, and Conflict. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 2005, 49(4), 625–633. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30045133. [CrossRef]

- Loria, Davie. Remote sensing and armed conflict a unique humanitarian role for geophysics; EarthScope Consortium, 22 July 2024; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Dauvergne, P. Loggers and degradation in the Asia-Pacific: Corporations and environmental management; Cambridge University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- De Waal, A. (Ed.). (2007). War in Darfur and the search for peace. Global Equity Initiative, Harvard University, in association with Justice Africa.

- Drine, I. ‘Successful’ Development Models in the MENA Region. Research Papers in Economics. 2012. https://ideas.repec.org/p/unu/wpaper/wp-2012-052.html.

- 27; Elbadawi, I.; Soto, R. Resource rents, institutions and violent civil conflicts. Defence and Peace Economics 2015, 26(1), 89–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etefa, T. Ethnicity as a Tool: The Root Causes of Ethnic Conflict in Africa—A Critical Introduction. In The Origins of Ethnic Conflict in Africa. African Histories and M odernities; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, N. Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language, 2nd ed.; Routledge, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, F. Reframing public policy: Discursive politics and deliberative practices; Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, J.; De Waal, A. Darfur: A new history of a long war; Zed Books, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J. B. Marx’s ecology: Materialism and nature; Monthly Review Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gandu, Y.K. An Analytical Basis for Botswana's Diamond-Enclave Sustainable Economic Growth And Wellbeing: Lessons For Nigeria; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ijere, M. The Resource Curse in Nigeria: Lessons and Policy Options. International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies 2015, 2(8), 35–44. https://www.ijrhss.org/pdf/v2-i8/5.pdf.

- Honwana, A. The time of youth: Work, social change, and politics in Africa; Kumarian Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ikelegbe, Augustine. The Economy of Conflict in the Oil Rich Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. African and Asian Studies 2006, 5, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R. T.; Olaniyi, T. K.; Olatubosun, P. Investigating the environmental sustainability issues of oil and gas operations in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. In Sustainable Energy and Allied Disciplines; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Klieman, K. A. U.S. Oil Companies, the Nigerian Civil War, and the Origins of Opacity in the Nigerian Oil Industry. The Journal of American History 2012, 99(1), 155–165. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41510311. [CrossRef]

- Le Billon, P. The political ecology of war: Natural resources and armed conflicts. Political Geography 2001, 20(5), 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K. K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, Siddharth. Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives; St. Martin’s Press: New York, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kleffmann, J.; Ramachandran, S.; Cohen, N.; O’Neil, S.; Bukar, M.; Batault, F.; Van Broeckhoven, K. Banditry violence in Nigeria’s Northwest: Insights from affected communities (Findings Report No. 36); UNIDIR, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, Matthew. Oil Ownership and Domestic Terrorism. In Non-State Violent Actors and Social Movement Organizations: Influence, Adaptation, and Change; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mamdani, M. Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism; Princeton University Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mehlum, H.; Moene, K.; Torvik, R. Institutions and the resource curse. The Economic Journal 2006, 116(508), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J. W. Capitalism in the web of life: Ecology and the accumulation of capital; Verso, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tahir, Muhammad; Khan, Muhammad Mumtaz. Do natural resources invite terrorism: evidence from resource-rich region. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natorski, M. The liberal peacebuilding approach: debates and models. In The European Union Peacebuilding Approach: Governance and Practices of the Instrument for Stability; Peace Research Institute Frankfurt, 2011; pp. 3–7. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep14480.4.

- National Early Warning Centre (NEWC). Blood and Treasure report; Office for Strategic Preparedness and Resilience, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI). The Resource Curse Revisited. 2015. https://resourcegovernance.org/sites/default/files/nrgi_Resource-Curse.pdf.

- Obi, C. Oil extraction, dispossession, resistance, and conflict in Nigeria’s oil-rich Niger Delta. Canadian Journal of Development Studies 2010, 30(1–2), 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonnaya. Illegal mining and rural banditry in North West Nigeria (Policy Brief) 2020.

- Onah, Emmanuel; Nwali, Uche. Monetisation of electoral politics and the challenge of political exclusion in Nigeria. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 2018, 56. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsola, A. Cost of governance and economic development in Nigeria: An empirical analysis of the presidency, the national assembly, and the judiciary expenditure. Journal of Business Management & Accounting 2023, 13(1), 31–55. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367544637.

- Ojewale, O. Undermining Peace: Banditry, Gold, and Elite Collusion in Northwest Nigeria. Deviant Behavior 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesco, Paola; Dasgupta, Shouro; De Cian, Enrica; Carraro, Carlo. Natural resources and conflict: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. In Ecological Economics; 2020; Volume 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M. F.; Liaqat, S.; Bashir, F.; Boota, M. From Shadows to Structures: Unveiling the Terrorism-Corruption Nexus in Developing Countries through Structural Equations Modeling (SEMs). Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 2024, 12(2), 1658–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P. No peace, no war: An anthropology of contemporary armed conflicts; Ohio University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, James; Acemoglu, Daron. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty; Random House, 2012; http://www.randomhouse.com.

- Rodney, W. How Europe underdeveloped Africa, 2nd ed.; Verso, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, M. The Natural Resource Curse: How Wealth Can Make You Poor. In Natural Resources and Violent Conflict: OPTIONS AND ACTIONS; Bannon, I., Collier, P., Eds.; World Bank, 2003; pp. 17–42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep02485.7.

- 62; Ross, M. L. What Do We Know about Natural Resources and Civil War? Journal of Peace Research 2004, 41(3), 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. D.; Warner, A. M. The curse of natural resources. European Economic Review 2001, 45(4–6), 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghatak, Sambuddha; Karakaya, Suveyda. Terrorists as rebels: Territorial goals, oil resources, and civil war onset in terrorist campaigns. In Foreign Policy Analysis; 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, C., & Wright, S. (Eds.). (1997). Anthropology of policy: Critical perspectives on governance and power. Routledge.

- Sommers, M. Stuck: Rwandan youth and the struggle for adulthood; University of Georgia Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stearns, J. K. Dancing in the glory of monsters: The collapse of the Congo and the great war of Africa; PublicAffairs, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UN Security Council. Concerns over the use of proceeds from the exploitation, trade and trafficking of natural resources for terrorism financing. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Uvin, P. Aiding violence: The development enterprise in Rwanda; Kumarian Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, I. The modern world-system: Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century (Vol. I); Academic Press, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.Y.; Raymond, N.; Gould, G.; Baker, I. Problems from Hell, Solution in the Heavens?:Identifying Obstacles and Opportunities for Employing Geospatial Technologies to Document and Mitigate Mass Atrocities. Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 2013, 2(3), Art. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, M. Resource curse? Governmentality, oil and power in the Niger Delta. Geopolitics 2010, 9(1), 50–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2011: Conflict, security and development; World Bank: Washington, DC, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Subgroups | # of Texts (Total = 36) | |

|---|---|---|

| Author Identity | Researcher / Academic |

24 |

| Policy Analyst / Think-Tank Author (e.g., Ogbonnaya, NRGI, AfDB) |

6 | |

| Government Agency (e.g., NEWC, OSPRE) | 3 | |

|

Intergovernmental Organization (e.g., AU, World Bank) |

2 |

|

| NGO Representative / Civil Society |

1 | |

| Decade of Publication | 1999–2010 | 8 |

| 2011–2020 | 12 | |

| 2021–2025 | 16 | |

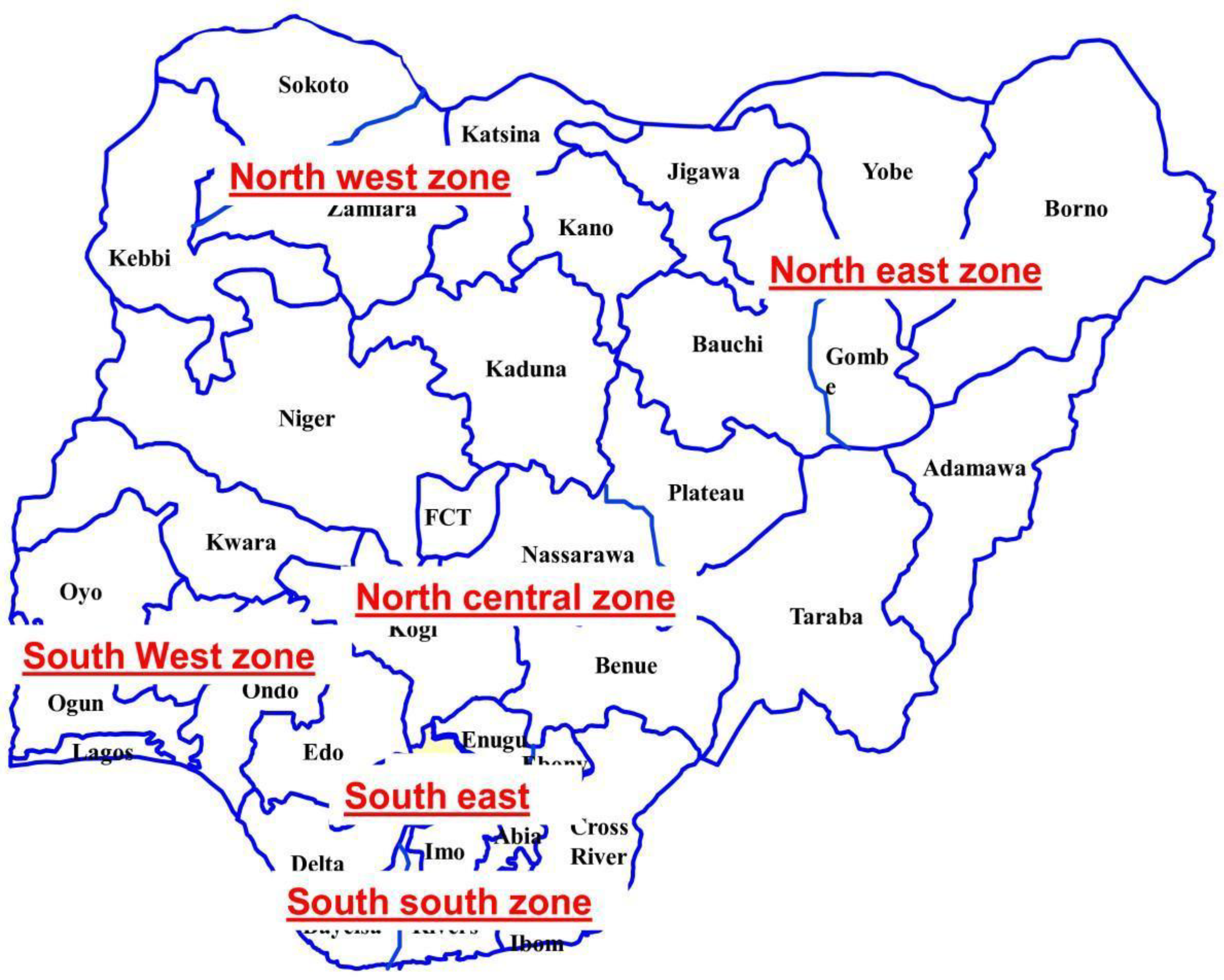

| Geographic Focus | Niger Delta (Rivers, Bayelsa, Delta, Akwa Ibom, Cross River, Edo) | 8 |

| Zamfara State (North-West) | 14 | |

| Plateau State (Jos Plateau) | 4 | |

| Kaduna / Katsina / Sokoto (North-West) | 3 | |

| Nasarawa / Kogi / Niger (North-Central) | 3 | |

| Borno / Yobe (North-East) | 2 | |

| Abuja (Federal Capital Territory) and national |

2 | |

| Publication Type | Peer-Reviewed Journal Article | 10 |

| Policy or Research Report | 12 | |

| Book Chapter / Monograph | 5 | |

| Government Publication | 6 | |

| NGO / Institutional Publication | 3 |

| Theme | Description | Representative Quotations from Archive Literature | No. of Texts (Cited in Archive) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental degradation and dispossession | Connects extraction to pollution, land loss, and declining community health, especially in the Niger Delta. |

“The heart of the ecological harms stem from oil spills-either from the pipelines which criss-cross Ogoniland...” “If you want to go fishing, you have to paddle for about four hours through several rivers before you can get to where you can catch fish and the spill is lesser…some of the fishes we catch, when you open the stomach, it smells of crude oil.” |

9 |

| Community resistance and activism | Highlights local mobilizations demanding remediation and redistribution of resource benefits. |

“In Delta state, youths have been known to demand development levy for the land occupied and employment for community youths from oil companies and other firms”. “Youths from the Umuechem community demanded provision of electricity, water, roads, and other compensation for oil pollution of crops and water supplies”. |

7 |

| Theme | Description | Representative Quotations from Archive Literature | No. of Texts (Cited in Archive) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Youth Marginalization and Unemployment | Links exclusion from resource benefits to youth frustration, unemployment, and vulnerability to violence. | “Young people are made vulnerable to exploitation by the state and forced to partner with government actors who have little legitimacy within their community, in order to gain access to the resources they require for their work”. “Mining activities often attract entire families displaced by poverty or environmental stress, drawn to mining areas in search of livelihood”. |

7 |

| Livelihood Loss and Displacement |

Shows how extraction and land acquisition push communities into poverty and dislocation. |

“When mining concessions are granted—often without adequate resettlement planning—entire communities are uprooted” “Land expropriation by government creates scarcity of land which negatively affects the traditional occupation of the people which could also lead to communal clashes and violence” |

5 |

| Theme | Description | Representative Quotations from Archive Literature | No. of Texts (Cited in Archive) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illicit economies of extraction | Positions artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) as a criminalized economy intertwined with violence and informal taxation. | “The illicit enterprise has drawn in local and foreign migrants and led criminal syndicates to resort to deadly violence in protecting their access to minerals” “Bandit leaders operate parallel systems of taxation over mining communities.” |

10 |

| Elite complicity | Frames political elites, military officers, and traditional leaders as beneficiaries of illegal extraction networks. | “Illegal miners front for politically connected individuals who collaborate with foreign nationals and corporations to smuggle and sell gold via neighbouring countries”. “Traditional authorities act as silent shareholders in illegal mining ventures.” |

8 |

| Moral economy of corruption | Depicts corruption not as deviation but as a normalized governance practice within resource frontiers. | “a regime of violent and armed resistance by youth militias and militant groups principally in response to state repression and corporate violence and as part of actions to compel concessions in respect of self-determination, regional autonomy, resource control and greater oil-based benefits”. “Local miners pay levies to both bandits and security agents in exchange for safety and access to sites, creating a complex web of informal governance”. |

7 |

| Securitization of informality | Treats artisanal miners as security threats, legitimizing state coercion and militarized responses. | “Criminal actors masquerading as miners must be neutralized to protect state sovereignty.” | 4 |

| Region | Mineral Resource(s) | Conflict Actor(s) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zamfara (NW) | Gold, laterite | Armed bandits, Fulani militias | Epicenter of extractive conflict, declared terrorist zone by FG |

| Shiroro, Niger State (NC) | Gold | Boko Haram, ISWAP factions | Mining sites used as abduction zones |

| Benue (NC) | Gold, lithium | Local militias, foreign-linked cartels | Illegal mining intertwined with boundary disputes and land grabs |

| Oyo (SW) | Gold, tourmaline | Corporate actors, criminal networks | Urban explosion (Ibadan) tied to black-market explosives for mining |

| Birnin Gwari, Kaduna (NW) | Tin, sapphire | Bandits, terrorist collaborators | Cross-border refuge zone for militants from Zamfara |

| Plateau State (NC) | Tin, uranium | Historical site of resource conflict | Sites now reoccupied by ASM and affected by radioactive contamination |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.