1. Introduction

The future of mining governance is no longer defined solely by economic performance or legal compliance. Instead, its viability increasingly depends on ensuring procedural justice1 and strengthening institutional credibility to sustain public trust, especially in contested scenarios amid mounting environmental and social pressures (Bebbington et al., 2019). With the increasing global calls for a just energy transition, resource-rich countries are subject to heightened scrutiny over how extractive projects align with diverse interests, knowledge systems, and evolving norms of legitimacy (Saenz, 2019; Spalding, 2023).

Across Latin America—and particularly in Panama—mining conflicts have underscored persistent governance vulnerabilities: environmental concerns, perceptions of exclusion, opaque decision-making, and declining trust in public institutions (Arsel et al., 2016; Spalding, 2023). In 2023, the annulment of Law 406 (Supreme Court of Panama, 2023) – which revoked the operating contract of Panama’s largest copper mine (Cobre Panama2) - and the nationwide prohibition of metallic mining concessions by Law 407 (República de Panamá, 2023), crystallized a legitimacy crisis with national and international repercussions, exposing fractures across institutional, community, and global scales (Bloomberg, 2024; IMF, 2024).

Frameworks such as the Social License to Operate (SLO) and Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) have advanced dialogue and rights recognition, yet they falter in systemic, multi-level legitimacy crises where governance fractures extend beyond project boundaries or procedural consent (Kemp & Owen, 2017; Luning, 2022).

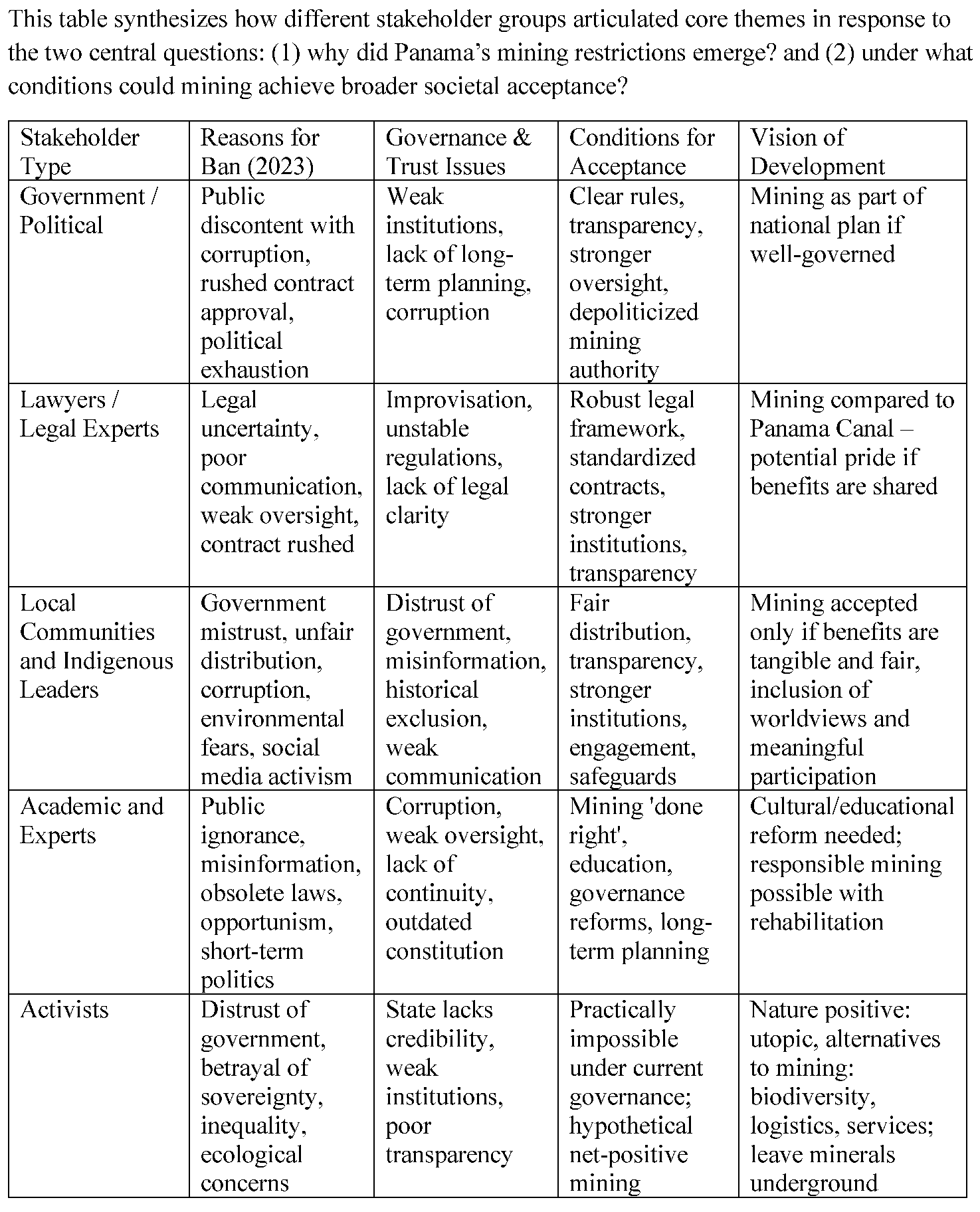

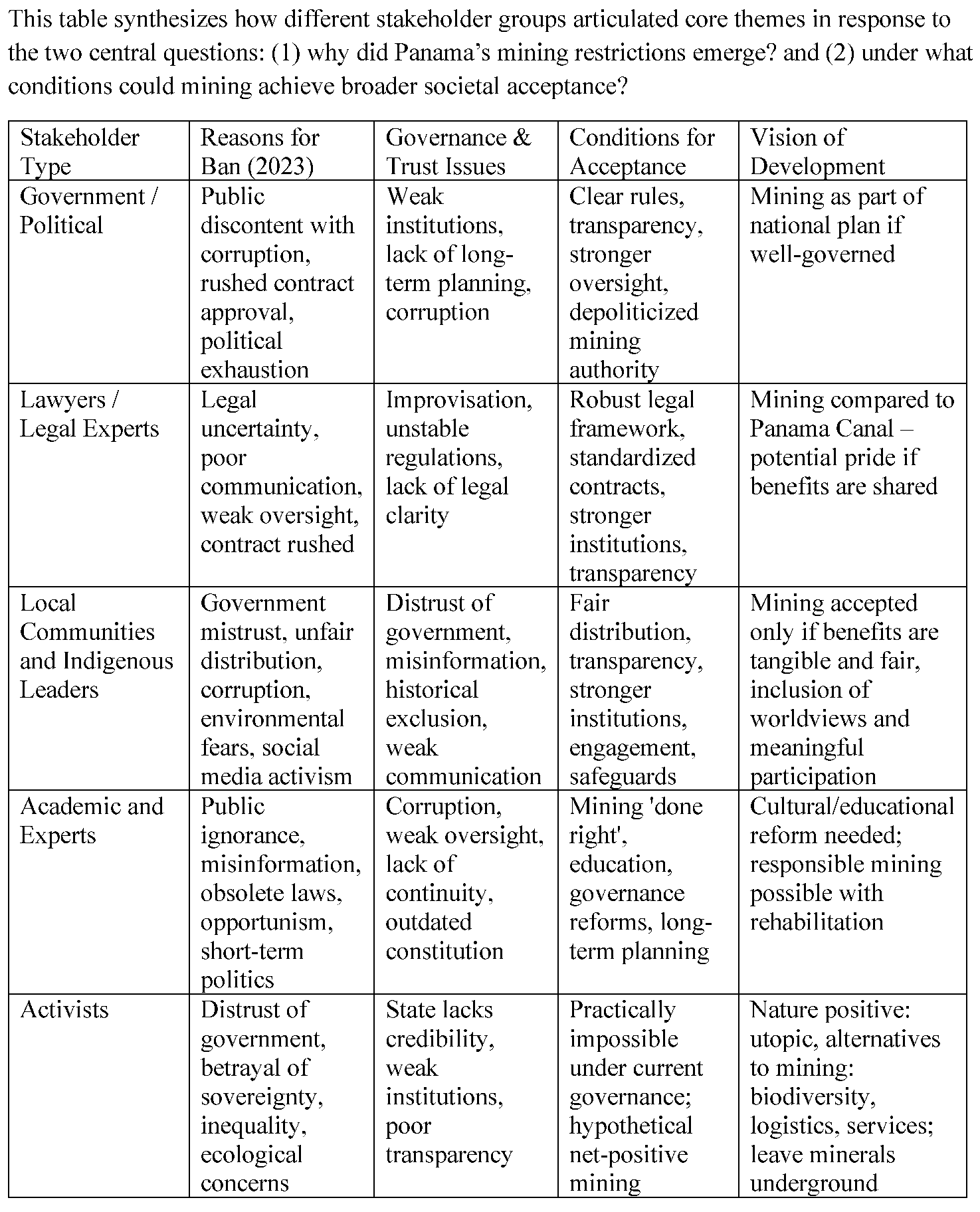

As debates over the decision to restrict mining intensifies, Panama offers as a timely case for understanding how legitimacy is dismantled and whether it can be potentially reconstructed. This research draws on 25 in-depth interviews in Panama with government officials, industry representatives, Indigenous leaders, local community actors, and civil society stakeholders (including critics of mining development), complemented by document review and policy/legal analysis. The interviews were structured around two central questions: (1) why did Panama’s mining restrictions emerge? and (2) under what conditions could mining achieve broader societal acceptance? By capturing diverse perspectives and contested narratives, this study proposes the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework as a stakeholder-informed tool to restore trust, strengthen accountability, and advance inclusive governance in extractive industries.

This research makes three contributions. Empirically, it amplifies diverse stakeholder perspectives to explain the roots of Panama’s mining legitimacy crisis and identify conditions for reconstruction. Conceptually, it proposes the SLM framework as a systemic, multi-actor alternative to project-level models like SLO and FPIC. Practically, it translates findings into pathways for governments, industry, and civil society to align extractive governance with environmental stewardship, institutional credibility, and social justice.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Rethinking Legitimacy in Mining

Contemporary debates in mining governance recognize legitimacy and trust as distinct but interrelated foundations of effective resource management. Legitimacy reflects perceptions that authority is exercised appropriately and fairly, grounded in shared norms and values (Beetham, 1991; Tyler, 2006), whereas trust indicates expectations of competent, reliable, and equitable action (Kaasa & Andriani, 2021; Saenz, 2019). Although intertwined, legitimacy may endure despite fragile trust, particularly in contexts marked by institutional weakness or historical conflict (Levi et al., 2009), but the lack of trust erodes legitimacy.

Within mining, legitimacy and trust operate across two axes: institutional trust in regulatory systems and relational trust between firms and local communities. While companies often prioritize community-level trust-building, evidence shows that local approval cannot substitute for sector-wide legitimacy—illustrated by the closure of Cobre Panama despite project-level relationships (CoNEP, 2024; Saenz, 2019).

Building on Suchman’s (1995) framework, legitimacy is understood as multidimensional, encompassing pragmatic (stakeholder self-interest), moral (ethical validity), cognitive (cultural comprehensibility), and increasingly, epistemic legitimacy—the recognition of diverse knowledge systems, particularly Indigenous and local epistemologies (Escobar, 2008; Kung et al., 2022; Moffat & Zhang, 2014). Extractive projects often face challenges when failing to respect these dimensions. Hence, long-term legitimacy depends not only on legal compliance but also on transparent, inclusive governance that integrates plural knowledge and mediates competing expectations across local, national, and transnational arenas (Kemp & Owen, 2013; Poelzer & Yu, 2021).

2.2. Governance, Good Governance, and Its Role in Legitimacy

Governance refers broadly to the mechanisms through which authority and accountability are structured, while good governance emphasizes transparency, inclusivity, responsiveness, and rule of law—all critical for legitimacy (Pierre & Peters, 2020; Weiss, 2012). In mining, these ideals must be translated into practices that protect rights, ensure fairness, and build both institutional and relational trust. Research demonstrates that perceptions of procedural justice often outweigh material benefits in determining acceptance, while gaps between formal rules and weak enforcement foster conflict (Franks et al., 2014; Bebbington et al., 2018).

Achieving good governance requires both institutional strengthening and capacity development across state and non-state actors. Distinctions between capacity for development and capacity development (Otoo et al., 2009) highlight that this involves not only resource mobilization and technical expertise, but also the empowerment of stakeholders to participate meaningfully in decision-making. Where capacity is weak, processes are often perceived as unfair and exclusionary; where it is nurtured, legitimacy improves through more informed, participatory, and accountable governance (Marín & Cunial, 2025). Good governance therefore underpins both input legitimacy—the fairness and inclusivity of decisions—and output legitimacy—the justice and effectiveness of institutional outcomes.

2.3. Translating Good Governance into Mining Mechanisms

Despite the proliferation of international standards and industry commitments, governance gaps remain pervasive in the mining sector. Too often, formal compliance is achieved without genuine participation, deepening community mistrust and exacerbating conflict (Spalding, 2023). In practice, translating the ideals of good governance into mining requires more than adopting global frameworks—it depends on credible enforcement, local accountability, and meaningful engagement.

A variety of governance tools have emerged over the past two decades. These include global principles such as the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (United Nations, 2011); binding regulatory standards such as the IFC Performance Standards (IFC, 2012); and voluntary disclosure frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI, 2023). While these instruments signal progress, their effectiveness is undermined by inconsistent enforcement and selective adoption, reducing them to symbolic or procedural exercises (Owen & Kemp, 2013; Dashwood, 2012).

More recent initiatives, such as the ICMM’s commitment to “No Net Loss/Net Gain of Biodiversity” (ICMM, 2025), aspire to move beyond harm mitigation toward positive ecological legacies. Yet critical scholarship cautions that without strong domestic governance and institutional accountability, such measures risk becoming technocratic or reputational strategies (Bull et al., 2013; Dash, 2012). Similarly, voluntary frameworks like IRMA and the ICMM’s Mining Principles now explicitly map their standards to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). However, achieving SDG-aligned outcomes—justice, transparency, inclusive participation—ultimately depends on robust legal enforcement, credible multi-stakeholder engagement, and cross-sectoral collaboration (Hilson, 2012; UNDP, 2018).

Participatory mechanisms have also become central. Two examples that became particularly influential in the extractive scenario, face significant limitations when operationalization remains weak or disconnected from context-specific governance realities (Boiral et al, 2022; Tomlinson, 2017), they are:

The Social License to Operate (SLO) as an informal, dynamic form of community approval grounded in trust and engagement rather than legal compliance (Owen & Kemp, 2013). It has influenced ESG standards and corporate practice globally, but risks devolving into a narrow reputation management tool that overlooks structural power asymmetries and the role of state institutions (Hall et al., 2015; Brueckner & Eabrasu, 2018).

Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), rooted in ILO Convention 169 and UNDRIP (2007), codifies Indigenous peoples’ right to consent to projects affecting their territories. While fundamental to Indigenous rights, FPIC has limitations in pluralistic contexts where it risks becoming a procedural box-checking exercise, insufficient to address inequities or incorporate non-Indigenous stakeholders (Thorpe & Hughes, 2020; Kung et al., 2022).

Taken together, these experiences highlight that governance tools alone cannot secure legitimacy. Scholars emphasize that meaningful legitimacy emerges only when such frameworks are embedded in broader systems of capacity development, institutional strengthening, and inclusive governance capable of mediating competing claims across multiple scales (Boutilier, 2014; Marín & Cunial, 2025).

2.4. Beyond Procedural Frameworks

Mining prohibitions in Latin America illustrate how legitimacy crises in extractive governance extend beyond procedural limitations to encompass normative, ethical, and epistemic dimensions (Helwege, 2015). Such measures carry institutional, financial, and reputational consequences for states and companies, underscoring how fragile legitimacy becomes when diverse knowledge systems and social demands are not adequately incorporated (Bebbington et al., 2019; Montoya, 2023).

Plural governance forces—activism, Indigenous resistance, and faith-based advocacy—have been especially influential in reframing extractive debates around moral and social values. The Catholic Church, through initiatives such as Pastoral Minera, invokes principles of human dignity, justice, and stewardship, offering an ethical perspective to extractive debates, sometimes contrasting with state narratives and past industry negative impacts. (Francis, 2015, Montoya, 2023, Pastoral Minera, n.d.). These interventions highlight that extractive legitimacy is shaped not only by regulatory compliance but also by collective values, symbolic authority, and societal expectations.

Peru, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and El Salvador, are example where mining restrictions were catalyzed by community opposition, environmental activism, and contested consultation processes, demonstrating how governance breakdowns intersect with normative pressures to reshape extractive development (CooperAccion, 2024; Imai et al., 2007; TicoTimes.net, 2024). Notably, El Salvador’s pioneering 2017 prohibition on metal mining (Montoya, 2023) was reversed in 2024 (The Guardian, 2024), reflecting ongoing tensions between environmental protection and economic imperatives. These cases underscore that legitimacy restoration cannot rely solely on procedural reforms but must also address deeper normative and epistemic dimensions.

2.5. Advancing Social Legitimacy for Mining

Addressing the limitations of procedural and governance-focused frameworks discussed above requires a more integrated and adaptive conceptual approach. This study draws on legitimacy theory, stakeholder and stakeholder salience theories, and political ecology—to scaffold a multi-dimensional understanding of legitimacy in post-crisis extractive governance proposed by the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework.

Legitimacy theory forms the foundation of this approach, treating legitimacy as a dynamic, socially constructed evaluation of whether institutions, decisions, or actors exercise authority in accordance with shared norms and values (Beetham, 1991; Suchman, 1995). As seen in the extractive sector, legitimacy comprises multiple dimensions—including pragmatic, moral, and cognitive legitimacy—and involves not just acceptance but ongoing public judgment and contestation (Suchman, 1995; Moffat & Zhang, 2014).

To operationalize this, the framework draws on Stakeholder Theory, which maps how a wide range of actors shape governance outcomes (Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Gifford et al., 2010), and Stakeholder Salience Theory (Mitchell et al., 1997; 2017), which clarifies how differences in power, legitimacy, and urgency determine whose interests are advanced or marginalized. This lens makes it possible to move beyond static lists of “stakeholders” to offer a dynamic, comparative approach that recognizes how shifting actor salience and institutional contexts affect governance trajectories.

Finally, political ecology further integrates attention to historical legacies, material grievances, and the embeddedness of environmental values and justice claims in broader systems of governance (Bridge, 2004; Bebbington et al., 2019). It reminds us that extractive conflicts are not only institutional disputes but also struggles over knowledge, identity, and environmental meaning—especially acute following governance crises where postcolonial fault lines and structural inequalities exist either currently or historically.

2.6. Research Gap and Justification

Building on the preceding review, legitimacy remains a central yet problematic concept within extractive sector governance. While frameworks such as SLO and FPIC have advanced standards for participation and consent, both the literature and stakeholder interviews reveal critical shortcomings—especially when crises move beyond the project level and entail complex, multi-actor dynamics (Kemp & Owen, 2013; Boutilier, 2014; Kung et al., 2022). The 2023 suspension of metallic mining in Panama exemplifies this, with localized grievances rapidly expanding into wider institutional and societal disruption.

Stakeholder interviews conducted for this research provided first-hand evidence of these limitations, highlighting gaps such as unclear responsibilities, insufficient integration of public and state actors, and challenges in creating responsive, inclusive engagement mechanisms. These insights extend the literature’s critique, emphasizing that addressing legitimacy requires approaches attuned to political, institutional, and societal complexity—rather than narrow project-level compliance (Szablowski, 2019; Breakey et al., 2025; Kazemi, 2022).

Empirical studies from post-crisis contexts underscore the necessity of embedding good governance principles and robust capacity-building across all levels (Franks et al., 2014; Marín & Cunial, 2025). Guided by these findings and informed by stakeholder perspectives, this study proposes the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) as an evolving framework designed to analyze and respond to legitimacy deconstruction, contestation, and reconstruction throughout governance crises. Situated at the intersection of local, national, and transnational forces, the framework provides a context-responsive tool for examining how legitimacy can be dismantled and potentially rebuilt in the extractive sector. Its application to Panama is intended as a proof of concept rather than a definitive global model. The framework will require further testing and co-development with stakeholders in other jurisdictions to evaluate its broader applicability and adaptability to different governance contexts.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Philosophical Orientation

This study employed a qualitative, single-case design (Yin, 2018) to analyze legitimacy reconstruction in Panama’s mining governance. The research is grounded in a critical realist ontology and an interpretivist–constructivist epistemology, which recognize that governance systems, legitimacy, and trust exist independently of perception but are only accessible through stakeholders’ socially constructed interpretations (Bagg, 2020; Alvarez et al., 2014; Prasad & Ingo, 2013).

This orientation is particularly suited to Panama’s context, where extractive legitimacy is deeply contested and shaped by historical grievances, institutional narratives, and competing visions of development (Spalding, 2023). To inform the development of the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework legitimacy was examined as a multi-scalar, plural, and dynamic process. The study tested the proposition that legitimacy reconstruction in Panama depends less on technical compliance and more on institutional credibility, plural inclusion, and relational governance.

3.2. Case Selection, Boundaries, and Units of Analysis

Panama was selected as a single case study because it presents a rare convergence of environmental, geopolitical, and governance dynamics. As one of the few carbon-negative countries (MiAmbiente, 2025), its exceptional biodiversity and strong public concern for environmental protection creates a highly contested terrain for extractive industries. At the same time, Panama’s strategic position as a global transport hub, financial center, and visible actor in international debates heightens the stakes of its resource governance choices (Britannica.com, 2025; IGF, 2020). The recent mining restrictions have intensified these dynamics, illustrating how disputes over natural resource governance intersect with questions of legitimacy, institutional strength, and economic resilience (Gomez, 2023). By 2025, pressures to reconsider the prohibition—driven by economic contraction, arbitration claims, and global demand for transition minerals—further underscore Panama’s salience as a timely case for examining the future of mining governance (IMF, 2024; Dou et al., 2023).

A structural feature further shaping Panama’s governance context is its constitutional prohibition of consecutive presidential re-election. This rule ensures democratic alternation, but in practice it has meant that every electoral cycle brings a change in governing party, with power consistently alternating across political lines. While this system reinforces pluralism, it also entrenches short-termism, as each administration tends to prioritize five-year agendas over long-term policy coherence. The result is a stop–start policy environment in which new governments often dismantle or reverse the initiatives of their predecessors. This institutional dynamic has profound implications for extractive governance, where legitimacy depends on commitments that extend beyond electoral transitions and require stability across successive administrations.

Study boundaries are defined by the post-2023 mining governance context, focusing on the contested period following the annulment of Law 406 and enactment of Law 407.

3.2.1. Units of Analysis

To capture the multi-scalar nature of legitimacy reconstruction, this study examines three interrelated units of analysis:

Local communities – directly affected populations whose perspectives illuminate procedural justice and relational governance.

Institutional actors – regulatory, judicial, and policy bodies central to institutional trust and credibility.

National stakeholders – a diverse group including Indigenous leaders, business chambers, activists, academics, students and legal/policy experts. These actors influence public discourse, generate competing knowledge claims, and shape epistemic legitimacy and broader societal acceptance.

Applying this multi-scalar lens informs the SLM framework by conceptualizing legitimacy as co-produced across local, institutional, and national levels. This approach enables analysis of how governance processes are dismantled and how they may be rebuilt through interconnected mechanisms of trust, justice, and inclusion.

3.3. Data Collection

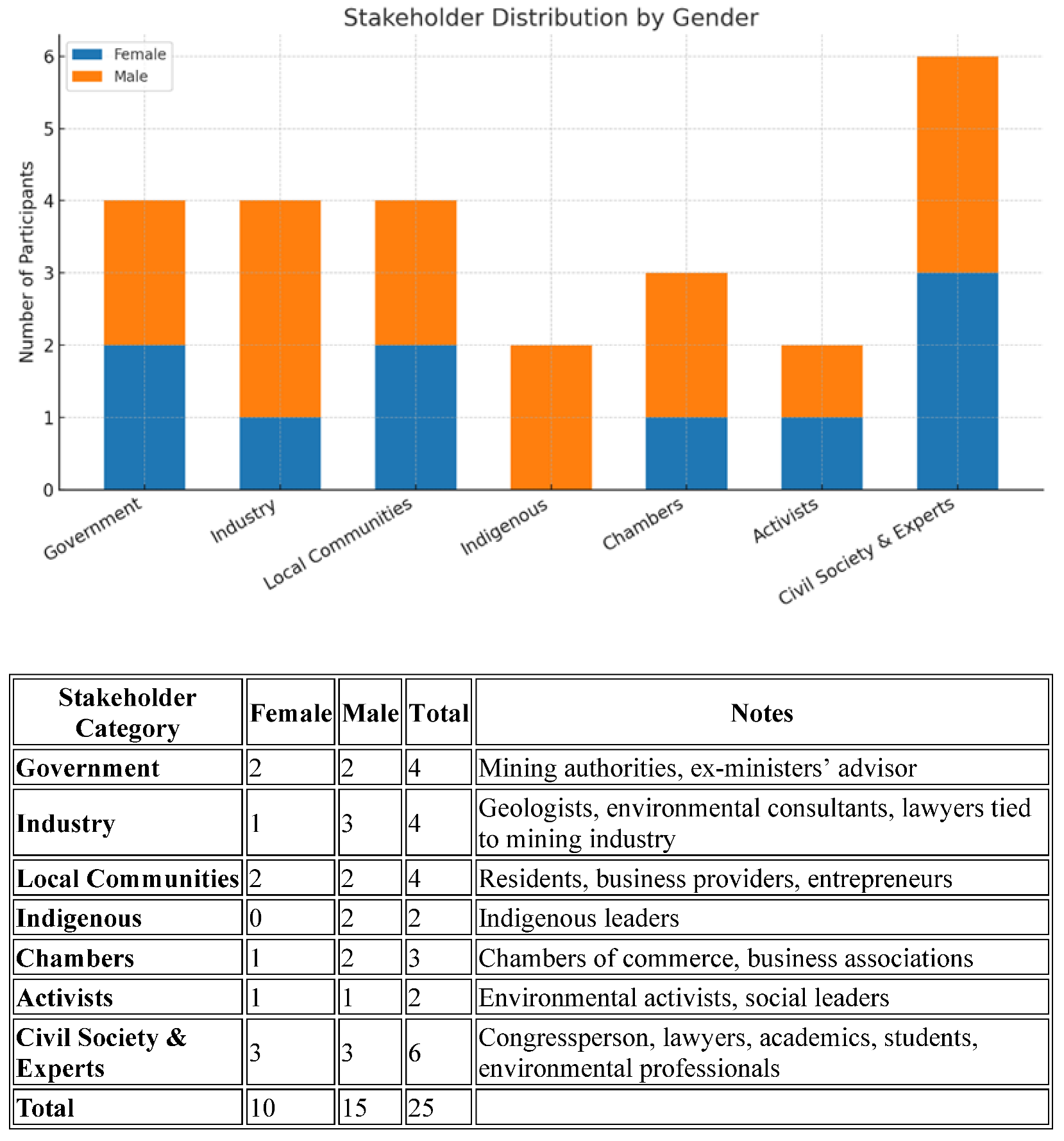

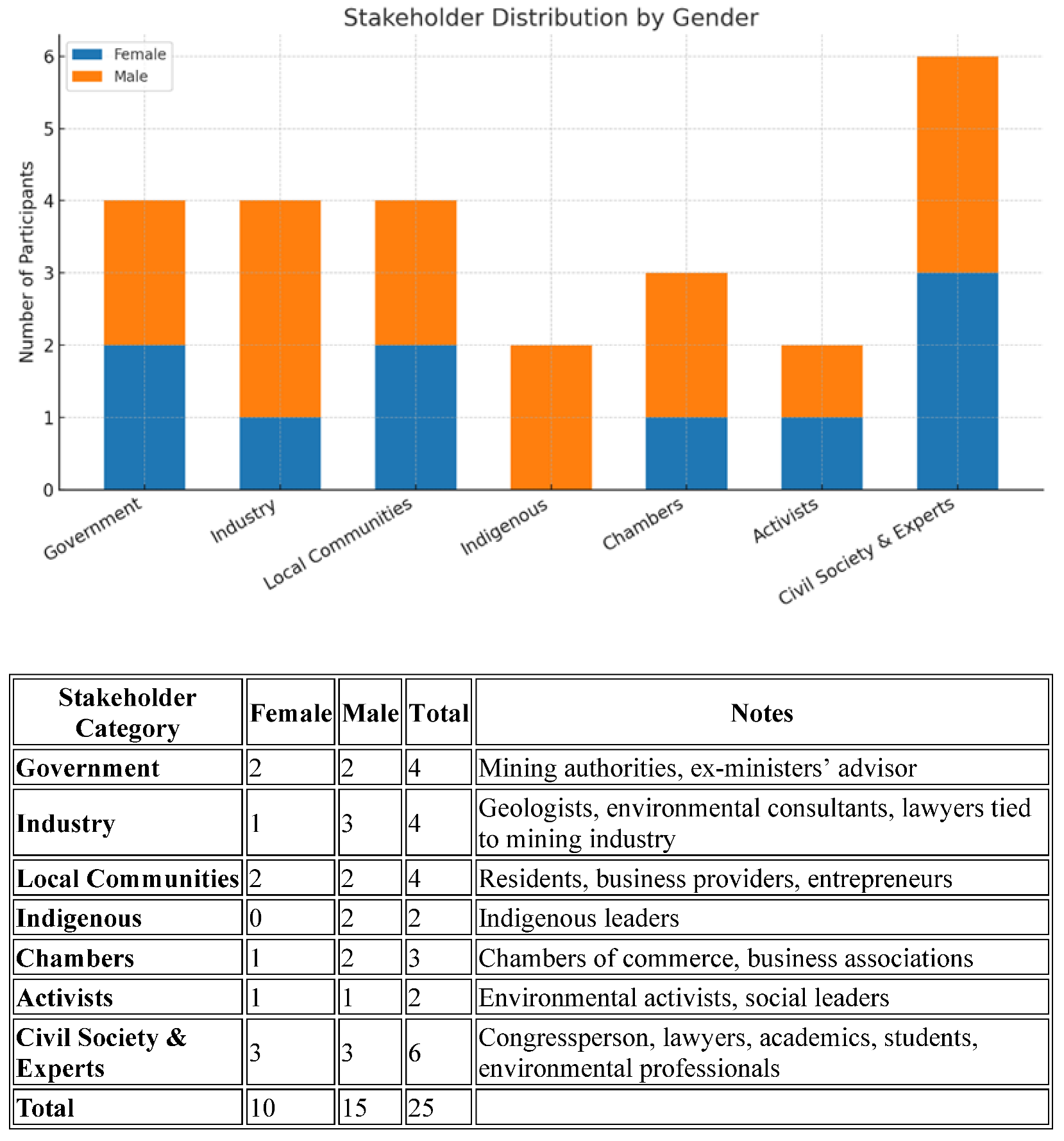

Semi-structured interviews and document review constituted the primary sources of data. Interviews were conducted in Panama with 25 stakeholders across seven categories: government (n = 4), industry (n = 4), local communities (n = 4), Indigenous representatives (n = 2), chambers of business (n = 3), activists (n = 2), and broader civil society/experts (n = 6, including lawyers, academics, students, environmental professionals, and business service providers). Of the participants, 10 were women and 15 were men, ensuring gender representation, though no systematic differences by gender were observed in responses (more details on

Appendix A).

Sampling followed a purposive, maximum-variation strategy to capture diverse perspectives across actors with differing power, legitimacy, and urgency (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Mitchell et al., 1997). Participants were identified and recruited through professional networks, snowball sampling, and outreach at public debates and conferences in Panama, which proved especially useful for including underrepresented groups.

All interviews were conducted in Spanish, either in person, via Zoom, or over WhatsApp, and typically lasted 45–90 minutes. With prior informed consent, interviews were audio-recorded on a password-protected smartphone in MP3 digital file format. Recordings were transferred the same day to an encrypted, password-protected laptop and original audio files were deleted from the phone after transfer.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim using Whisper AI, with manual verification by the researcher to ensure accuracy, particularly for idiomatic expressions. Transcripts were then anonymized: names, organizations, and identifiable references were replaced with pseudonyms or generalized descriptors (e.g., “industry representative,” “community leader”). A unique code was assigned to each interview to preserve analytical traceability without revealing participant identity.

Spanish-language summaries were prepared from the verified transcripts and carefully translated into English. These, together with anonymized transcripts and the researcher’s reflexive field notes, were uploaded into NVivo for coding and analysis. All files were stored in password-protected folders in accordance with ethics protocols.

Interviews focused on two overarching research questions: (1) why did Panama’s mining restrictions emerge? and (2) under what conditions could mining achieve broader societal acceptance? To avoid framing bias, participants were explicitly told that envisioning a future without mining was equally valid as supporting responsible mining. They were also invited to reflect on what a world without mining would mean for Panama and for global resource demand. A list of notable quotes is available on

Appendix D.

To complement interview findings, an extensive document review was undertaken, including laws, contracts, court rulings, protest materials, policy and industry reports, and media coverage (CoNEP, 2024; IDB, 2021). Document analysis contextualized interviews, informed coding categories, and provided an independent basis for triangulation.

3.4. Data Analysis

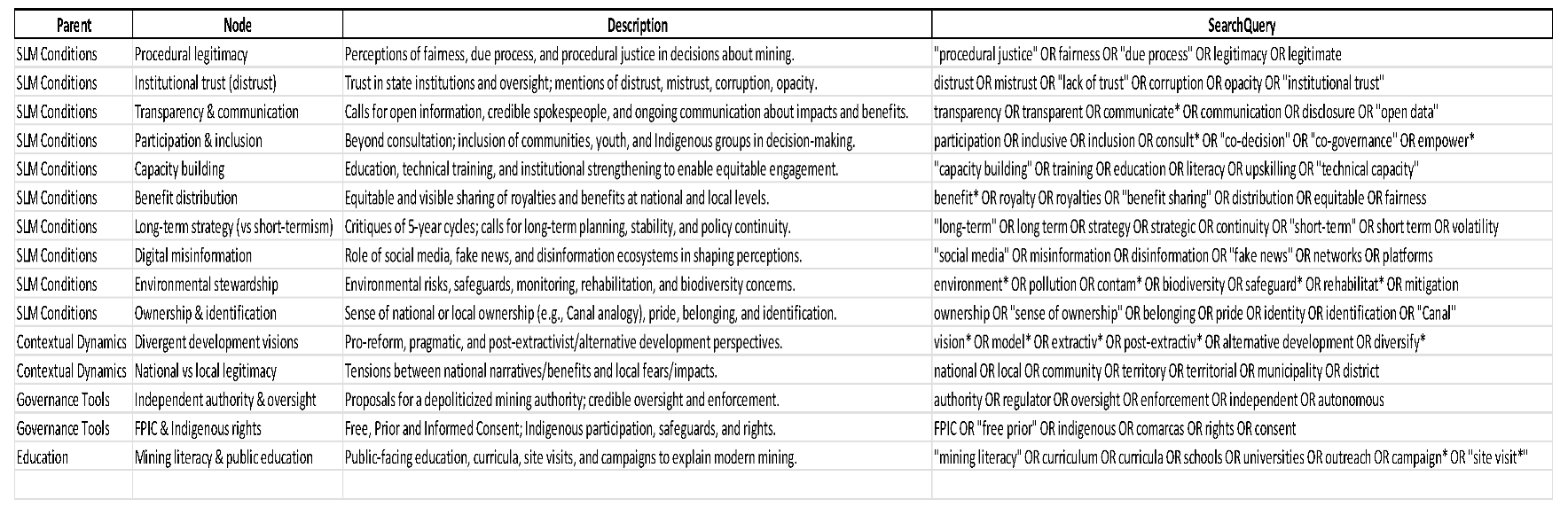

Data analysis followed a hybrid thematic strategy. Deductive coding was guided by sensitizing concepts from the SLM framework—procedural justice, institutional trust, epistemic legitimacy, and relational governance—while inductive coding allowed new themes to emerge, such as social movement dynamics, perceptions of corruption, misinformation, environmental concerns, and distributional fairness.

Analysis began with descriptive codes (e.g., trust in institutions, transparency, legal uncertainty, environmental concerns, and perceptions of unfair benefit distribution), which encompassed not only economic outcomes but also questions of equity and social justice. These descriptive codes were then grouped into broader thematic categories (e.g., institutional trust, governance quality, legitimacy crises). Finally, these themes were connected to higher-level concepts from the proposed SLM framework, enabling systematic movement from participants’ accounts to theory-informed insights. A Codebook sample is available on

Appendix F.

All transcripts were managed and analyzed in NVivo 15, where coding, memoing, and matrix queries ensured rigor and traceability. NVivo outputs were complemented by ChatGPT-assisted thematic exploration, which helped cluster emergent themes and cross-check them against researcher field notes. Generative AI tools (See statement on Backmatter) were used only to assist with thematic clustering, text refinement, and visualization support; all coding decisions and interpretations were conducted and validated by the researcher. This triangulation enhanced reliability while maintaining reflexivity.

Finally, Stakeholder Salience Theory (Mitchell et al., 1997; 2017) was used as an interpretive lens to assess how different actors emphasized power, legitimacy, and urgency in their positions. While not applied as a formal coding scheme, the framework helped make sense of contrasts across stakeholder groups and linked participants’ perspectives to broader questions of governance and legitimacy. Industry actors often emphasized urgency, highlighting economic contraction and arbitration risk. Communities and Indigenous leaders foregrounded legitimacy, centering on rights, participation, and fairness. Government officials spoke from a position of institutional power but were frequently perceived as lacking legitimacy. Viewed through this lens, the interviews revealed how governance crises emerge when power is disconnected from legitimacy, or when urgent claims are sidelined, underscoring the need for frameworks such as SLM that integrate these dimensions into a more systemic understanding of extractive governance.

4. Results

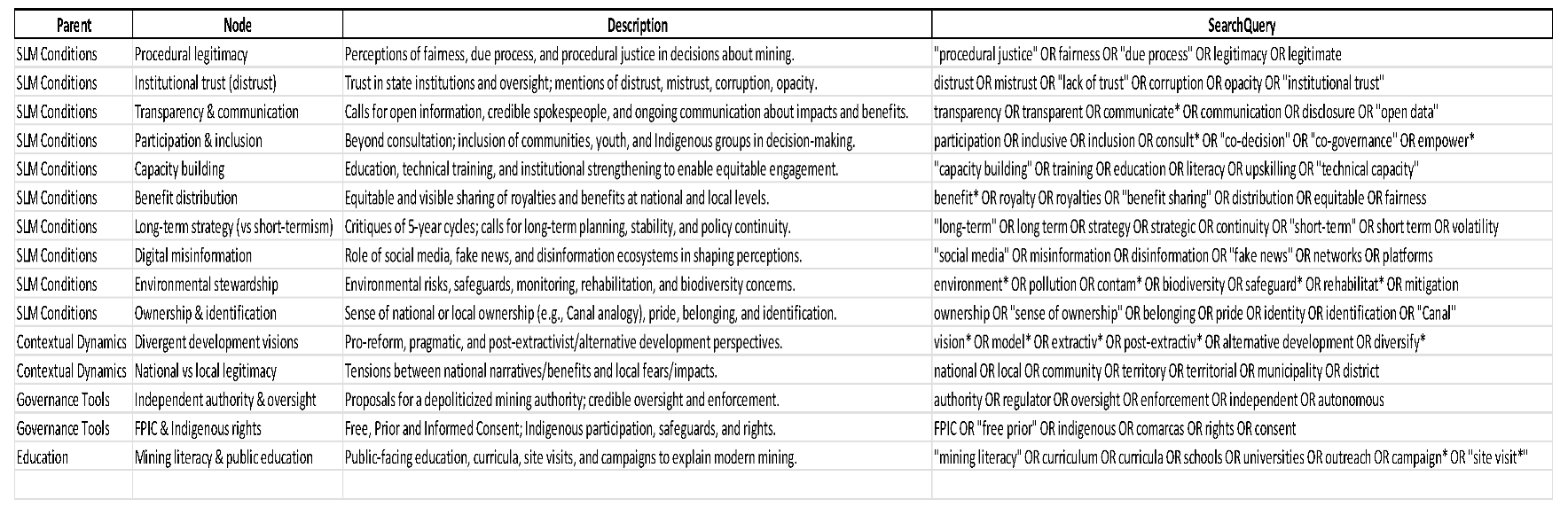

The findings are organized according to the four dimensions proposed for the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework—procedural justice, trust and institutional credibility, epistemic legitimacy, and relational governance. This deductive structure was complemented by inductive themes raised during interviews. Together, the analysis shows how Panama’s stakeholders (n = 25) understood the collapse of legitimacy in 2023 and what conditions they identified for its possible reconstruction.

4.1. Procedural Justice: Transparency, Accountability, and Institutional Weakness

A total of 17 participants (68%) directly linked the 2023 mining crisis to fragile procedures and weak institutional capacity. Government respondents acknowledged gaps in regulation and oversight, while civil society, activists, and Indigenous representatives emphasized corruption, lack of accountability and the volatility of Panama’s five-year political cycles, as one business leader noted: “In an ideal world, mining could be done responsibly. But Panama needs stronger institutions and clear long-term policies, not just five-year political cycles” (Interview 01).

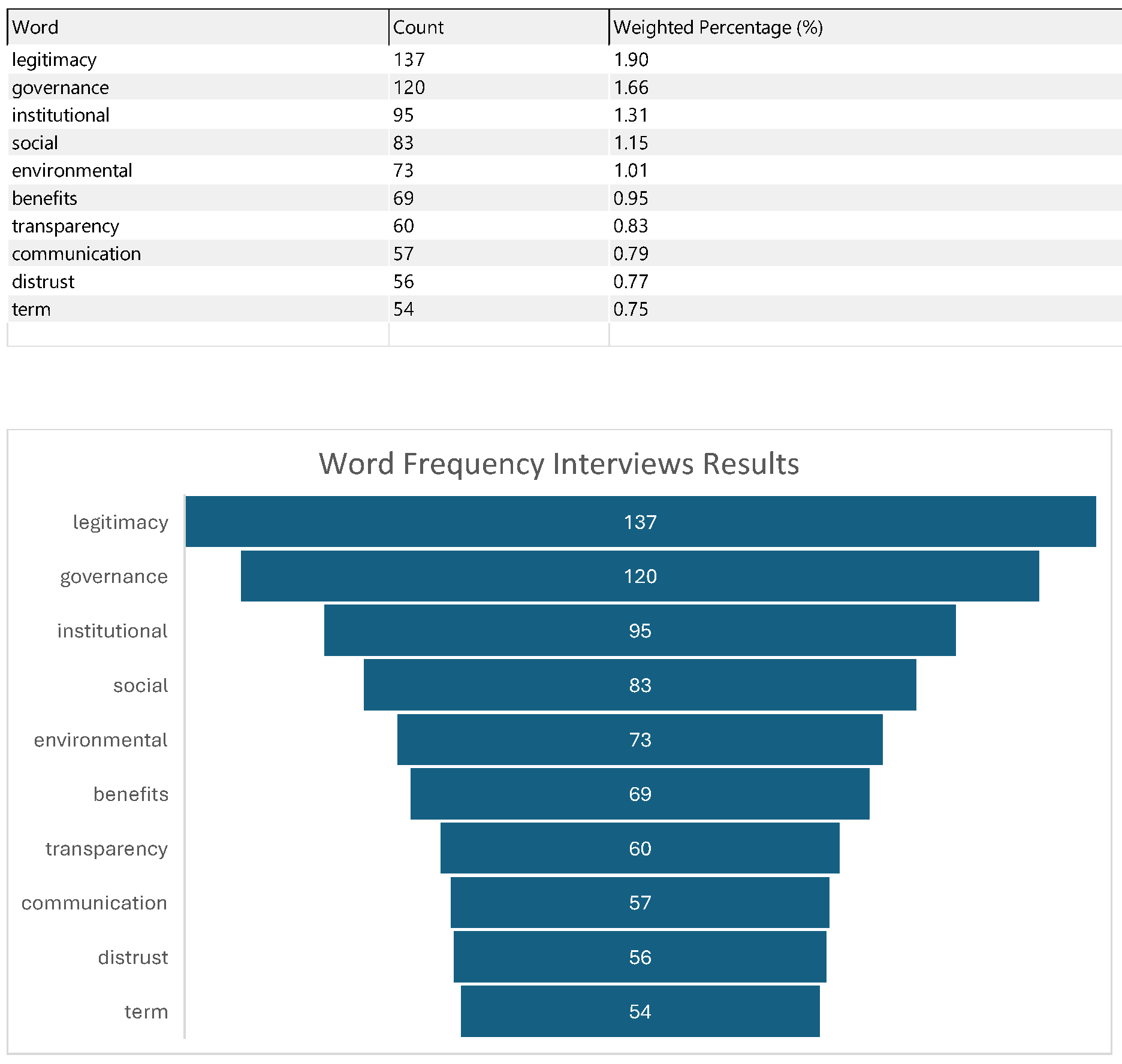

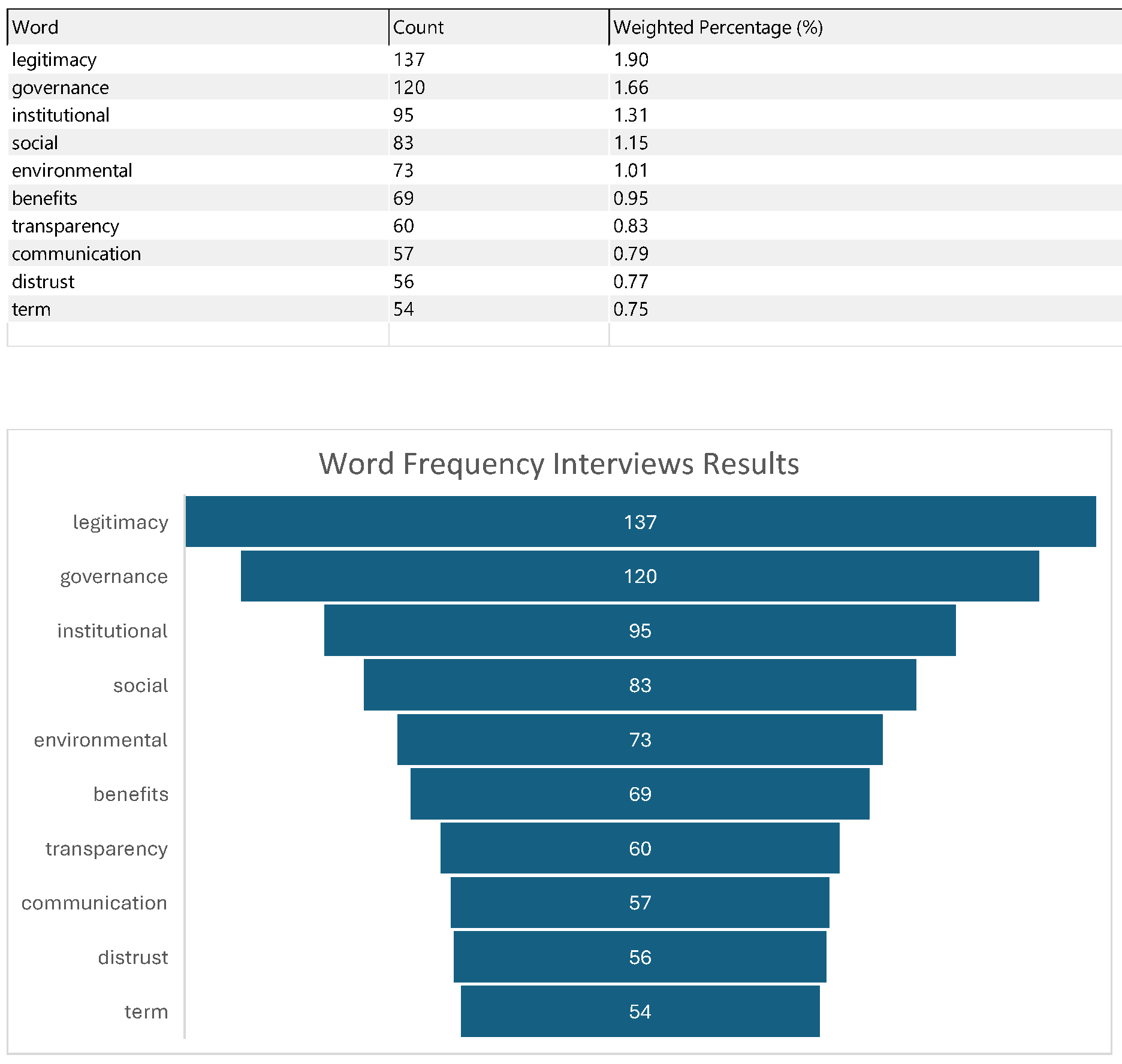

Transparency emerged as a near-universal concern, raised by 23 of 25 participants (92%). Respondents described the lack of accessible information on contracts, environmental impacts, and revenue flows as creating a vacuum filled by misinformation and fear. This emphasis is reflected in the frequency of terms (see

Appendix C) such as transparency (60 mentions), communication (57), and distrust (56), which ranked among the most cited words in the interviews (see Appendix 6 for more details). As one community leader explained:

“If there is no transparency, people imagine the worst. Information must be shared clearly and early” (Interview 04).

4.2. Trust and Institutional Credibility

Distrust in state institutions was the most pervasive finding. It was mentioned by 24 of 25 participants (96%) and described by all stakeholder categories, including those broadly supportive of mining. Even industry and business chamber representatives acknowledged that weak enforcement and broken promises had eroded credibility. Past experiences of limited consultation and unmet commitments were repeatedly cited as reasons communities doubt that future agreements would be honored.

Ten participants (40%) pointed to the collapse of the IDB-supported mining reform initiative (IDB, 2021; 2023) as emblematic of governance fragility, reinforcing public skepticism toward institutional reforms - cited by respondents as both a promising model and a missed opportunity. The salience of this theme is reinforced by the prominence of legitimacy (137 mentions), governance (120), and institutional (95) in the interviews (

Appendix C).

An area of divergence concerns the time horizon for potential social acceptance of mining. Some younger stakeholders expressed optimism that, with sustained public education and generational political renewal, mining could be reconsidered within 5–10 years. Industry actors similarly argued that institutional reform and visible benefits could help rebuild trust in the near term. By contrast, pragmatic voices and activist groups contended that legitimacy, once broken, is extremely difficult—if not impossible—to restore (Interviews 24, 25). From their perspective, acceptance is either unattainable or would require profound cultural and institutional transformations extending over several decades.

4.3. Epistemic Legitimacy: Divergent Knowledge Claims and Environmental Concerns

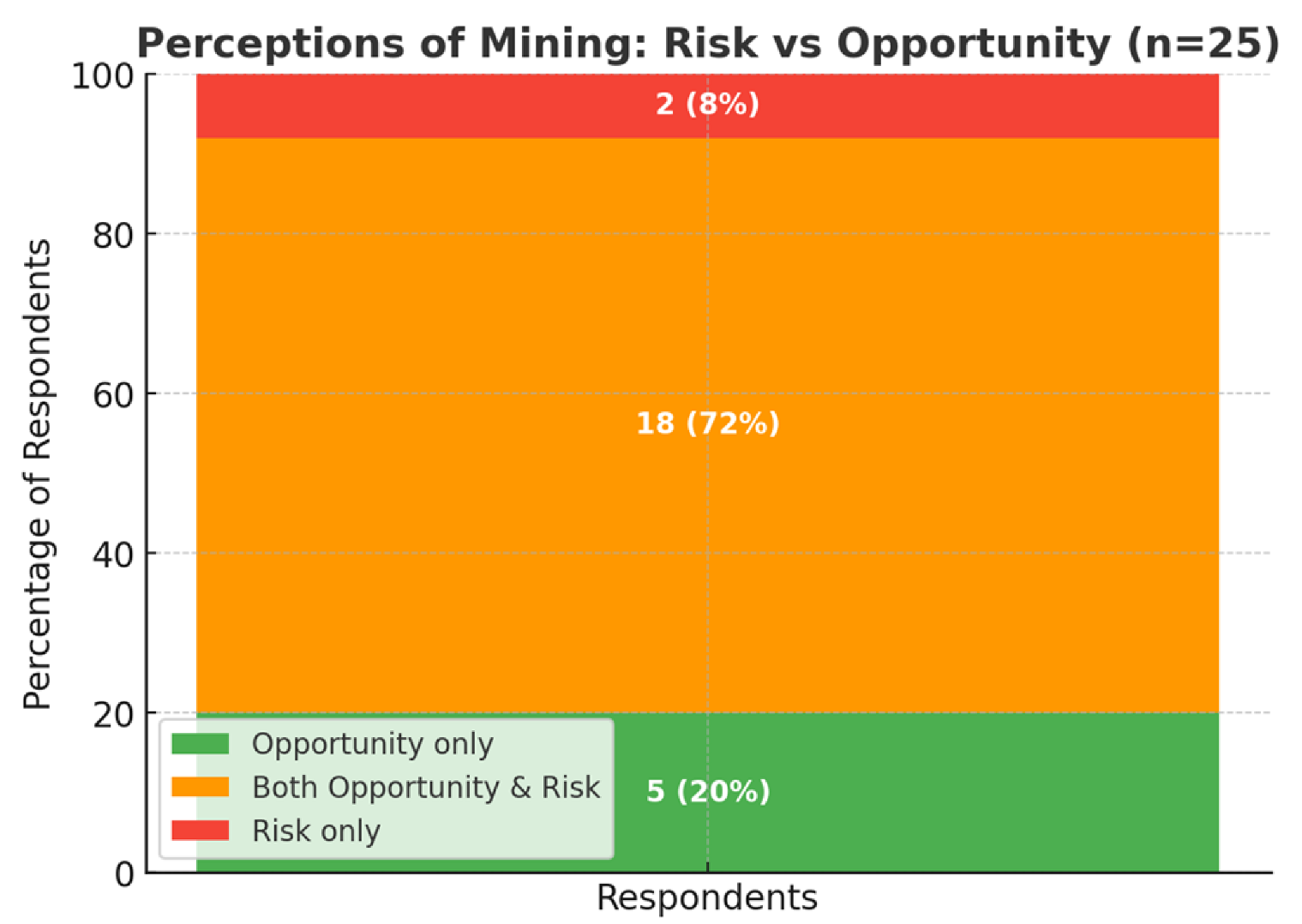

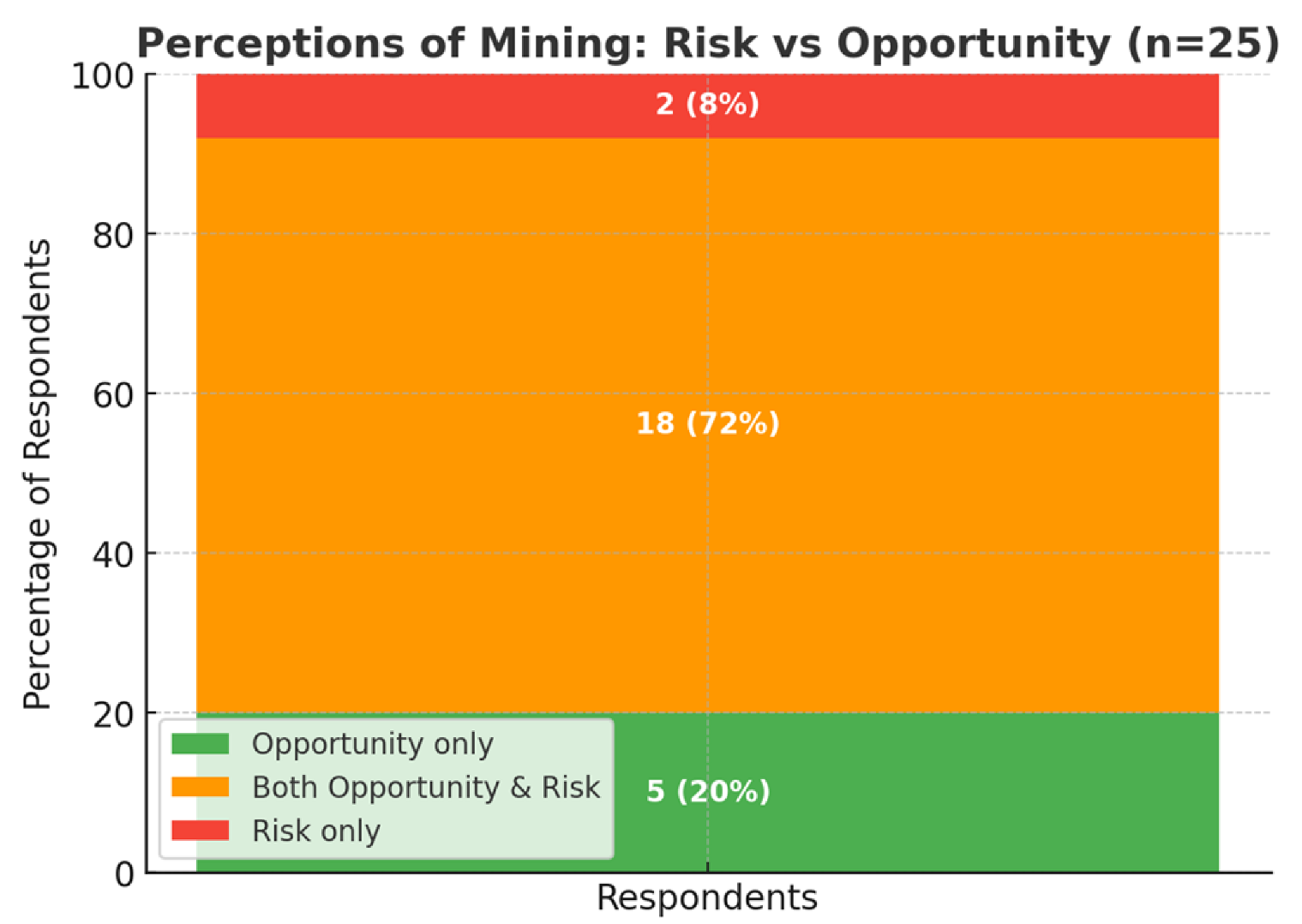

Stakeholders diverged sharply in their assessments of mining’s risks and opportunities (See

Appendix B). Of the 25 participants, 22 (88%) acknowledged potential opportunities, while 12 (48%) simultaneously identified mining as a risk. Only 2 participants (8%) framed it exclusively as a risk.

Risks were stressed by activists, Indigenous leaders, and environmental experts, who highlighted biodiversity loss, water contamination, and tailings dam safety under Panama’s tropical climate. One activist argued: “Mining is necessary, but I aspire to a Panama that works with nature and leaves behind the destructive extractives model” (Interview 25). These findings resonate with Montoya’s (2023) analysis, which shows that conflicts over extractives are not only material but also epistemic, rooted in struggles over whose knowledge is recognized as legitimate in governance processes.

Opportunities were emphasized most often by government, industry, and chambers of business, portraying mining as a multisectoral driver comparable to the Panama Canal, particularly in relation to employment, fiscal revenues, and economic diversification. One stakeholder stated, “Mining needs to be seen as the multisectoral driver that it is, not only as an extractive business” (Interview 05). Such divergent framings of risk and opportunity mirror broader regional patterns in which epistemic legitimacy becomes central to contested mining governance (Bebbington, 2019; Montoya, 2023).

The language of the interviews reflected this dual framing. Environmental (73 mentions) and benefits (69) were among the ten most frequent terms, underscoring how both opportunity and risk were central to the debate (see

Appendix C).

4.4. Relational Governance: Intermediaries, Inclusion, and Plural Voices

A total of 14 participants (56%) explicitly identified the Catholic Church, NGOs, or media as more credible than government institutions in shaping public opinion. The Church was highlighted across stakeholder categories as both mediator and moral authority, framing mining as an issue of justice, dignity, and stewardship of creation.

The need for more inclusive engagement was cited by 18 participants (72%), who emphasized that Indigenous peoples, grassroots organizations, and local communities must be involved in future decision-making beyond symbolic consultation. Capacity building was also widely raised (mentioned by 19 of 25 participants; 76%), with calls to strengthen not only state regulators but also community and civil society capacities to engage in technical, legal, and environmental oversight.

Finally, while all groups recognized the importance of public participation, they differed sharply in how it should be understood. Government and industry tended to frame participation in terms of consultation processes and communication strategies. Civil society emphasized the need for more substantive engagement, calling for education and informed public debate. Activist and Indigenous perspectives went further still, advocating for pluralistic inclusion, citizen decision-making authority, and recognition of alternative worldviews that question the very premises of extractivism.

4.5. Cross-Cutting Insight

Across the four dimensions, respondents consistently stressed that legitimacy cannot be restored through technical fixes or isolated reforms. Nearly all participants (24 of 25; 96%) identified transparency, institutional credibility, plural knowledge, or inclusive governance as essential preconditions for any resumption of mining. These findings are further reflected in the distribution of conditions for acceptance across stakeholder categories (see

Appendix E).

5. Discussion

As revealed in the Results, Panama’s 2023 mining restrictions were not simply a contractual dispute but the culmination of multi-layered legitimacy crises. These crises are echoing wider patterns across Latin America where extractive industries collapse into social conflict when weak institutions, corruption perceptions, and environmental risks converge (Arsel et al., 2016; Bebbington et al., 2019; Spalding, 2023). Situating the findings within theoretical debates shows why legitimacy in mining extends beyond technical compliance, why institutional trust is indispensable, and why legitimacy is distributed across plural societal authorities rather than monopolized by state or industry.

5.1. Legitimacy Beyond Technical Compliance

The Results demonstrated that transparency and procedural weakness were among the most frequently cited themes, with nearly all respondents linking them to the restrictions on metallic mining brought by the annulment of Law 406 and the implementation of Law 407. Here, compliance with formal contracts or environmental approvals was not enough. What mattered most was whether processes were perceived as transparent, inclusive, and trustworthy. This supports Suchman’s (1995) distinction between pragmatic, moral, and cognitive legitimacy: pragmatic legitimacy faltered as benefits were seen as unequally distributed, moral legitimacy collapsed amid corruption perceptions, and cognitive legitimacy weakened as misinformation widely disseminated caused environmental concerns, as reflected by this quote: "Institutional weakness opened the door for disinformation and extremist narratives. To restore legitimacy, Panama needs stronger institutions, effective communication, and long-term coherent policies that integrate government and industry" (Interview 02).

This interpretation also aligns with governance scholarship, which cautions that legal procedure alone cannot secure acceptance if trust and fairness are absent (Franks et al., 2014; Owen & Kemp, 2013). In Panama, as the Results show, legitimacy deficits persisted even where technical or legal benchmarks had been met.

5.2. Trust, Institutions, and the Reconstruction of Legitimacy

As revealed in the Results, distrust in state institutions was nearly universal (96% of participants), cutting across supportive and critical stakeholders alike. In the Discussion, this distrust is interpreted as a decisive barrier to rebuilding legitimacy and as a structural weakness undermining any reform effort. This interpretation resonates with Holmes’ (2008) theoretical framework, which demonstrates that corporate environmental policy is shaped not only by internal decision-making but also by external institutional pressures and stakeholder expectations. In the Panamanian context, where 17 participants (68%) explicitly linked the 2023 mining restrictions to fragile institutions and regulatory weakness, Holmes’ insights reinforce why institutional strengthening must be understood as a legitimacy-building process, not merely a technical reform.

This insight also clarifies why existing frameworks like SLO and FPIC fall short in post-crisis contexts. As the Results highlighted, respondents did not call for new technical standards, but for durable institutions capable of credible enforcement. SLO’s company-centric approach (Kemp & Owen, 2017) and FPIC’s legal scope (Spalding, 2023) are necessary but insufficient; both require integration within broader governance reforms to rebuild institutional trust.

5.3. Plural Voices and Uneven Influence

The Results showed that 14 participants (56%) explicitly named the Catholic Church, NGOs, or media as strong influential actors. This indicates that legitimacy in Panama is relational and distributed across non-state actors who command higher public trust. Interpreted theoretically, this underscores the importance of epistemic pluralism in governance: legitimacy is co-produced through overlapping authorities, not delivered solely by state or corporate actors (Kemp & Owen, 2013; 2017; Moffat & Zhang, 2014). This interview (16) called for recognition and inclusion of multiple knowledge systems: "Mining could only return if our communities are part of the decisions, with real benefits and respect for our rights — otherwise, it will always be rejected."

The case of the Catholic Church exemplifies the multifaceted role of faith-based actors in mining governance. In Panama, the Church has frequently adopted a critical stance toward mining (López, 2023; Rendon, 2024), aligning with environmental and social movements in defense of creation3 (Francis, 2015; Pastoral Minera, 2023). Elsewhere in Latin America, however, the Church has assumed a more collaborative or reform-oriented posture, engaging with industry and communities to encourage more responsible practices. Bryant (2015) highlights initiatives, including those of the Development Partner Institute4, that explore partnerships between faith-based organizations and mining companies as “unexpected collaborations for prosperity.” Similarly, in a 2025 presentation at the Universidad Nacional de Piura, in Peru, Father Henry Yoan David, Director of the Pastoral Minera in the Archdiocese of Antioquia, emphasized that the Church’s response to mining challenges is not outright rejection but the promotion of just and responsible mining as a pathway for reform (David, 2025).

An additional illustration of plural voices is found in a letter sent in 2024 to the President of Panama by Indigenous groups. The letter, signed by four Presidents and one Cacique from Indigenous territories, stated: “…we would be willing to promote the interest of mining companies, and others to associate (joint venture) with us to propose the development of already identified mining projects within our Comarca, provided that we have a reasonable equity participation and that the due process of consultation is respected” (Indigenous Territories of Panama, personal communication, 2025). This document reveals an underexplored dimension: while many Indigenous and activist perspectives may oppose resource extraction outright, other Indigenous authorities express conditional openness to mining under frameworks of equity, partnership, and consultation (O’Faircheallaigh & Corbett, 2006; Whiteman & Mamen, 2002). Such diversity within Indigenous governance itself underscores the complexity of legitimacy and the uneven distribution of influence across stakeholder groups.

5.4. Global Frameworks, Local Skepticism

As shown in

Appendix B, respondents often framed mining simultaneously as opportunity and risk, with “environmental” and “benefits” ranking among the most cited terms. This duality shaped how international frameworks such as ICMM’s “Nature Positive” model is perceived. While these initiatives articulate a restorative vision for mining, stakeholders in Panama viewed them with skepticism, questioning whether voluntary frameworks could succeed in a context of weak enforcement and entrenched mistrust.

This skepticism resonates with critical scholarship on “no net loss” and “nature positive” strategies, which warns that such commitments can become technocratic or reputational exercises, obscuring power asymmetries and diluting accountability (Bull et al., 2013). The Results suggest that unless global frameworks are embedded in robust, context-specific governance systems—backed by independent verification and participatory oversight—they will lack legitimacy in Panama.

An additional layer to these debates is Panama’s considerable mineral potential. According to the Panamanian Chamber of Mining (CAMIPA, 2024), the country hosts a diverse portfolio of metallic and non-metallic resources that could support long-term development if managed responsibly. Geological research further confirms this potential: Redwood (2020) documents Panama’s position within an arc metallogenic province on the trailing edge of the Caribbean Large Igneous Province, with significant deposits of copper, gold, and other minerals distributed throughout the isthmus. Such evidence underscores that the debate is not about resources, but the governance conditions under which their extraction might be deemed socially legitimate.

5.5. Toward a Stakeholder-Informed Framework: Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM)

As revealed in the results, legitimacy in Panama’s mining sector cannot be rebuilt through cosmetic reforms, technical compliance, or external frameworks alone. Nearly all stakeholders emphasized that credible institutions, transparent processes, plural knowledge, and inclusive governance were essential preconditions for any resumption of mining. These insights form the foundation for the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework.

Proposed as an extension to SLO and FPIC, the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework is co-produced with stakeholders based on empirical insights from interviews, emphasizing a governance approach rooted in participatory legitimacy reconstruction. SLM reconceptualizes legitimacy as a systemic, multi-actor, and dynamic process across four interdependent dimensions: procedural justice, institutional credibility, epistemic pluralism, and relational governance. Unlike SLO and FPIC, which often operate at the project or legal level, SLM intends to respond to stakeholder experiences in Panama by situating legitimacy at multiple scales—local, institutional, and national—and by explicitly addressing governance breakdowns.

The Panamanian case also illustrates that external frameworks such as ICMM’s “nature positive” approach only gain traction when embedded in trusted, context-responsive governance. SLM proposes to address this gap by linking global normative aspirations to local legitimacy conditions, emphasizing independent verification, participatory monitoring, and recognition of Indigenous and community worldviews. In this way, SLM is not a replacement for SLO or FPIC but an integrative evolution, designed to make legitimacy resilient in volatile or post-crisis environments.

Table 1 synthesizes the comparative features of SLO, FPIC, and the proposed SLM framework. While it risks appearing aspirational, it is not intended as a fully operational model at this stage. Instead, it represents a conceptual architecture that can be tested and refined in practice.”

Conceptually, SLM synthesizes insights from legitimacy theory, stakeholder theory, stakeholder salience, and political ecology, positioning legitimacy as a dynamic and rebuildable process. It does not assume full consensus or the resolution of all contestations; rather, its aim is to enhance the perceived fairness, inclusiveness, and credibility of governance, particularly in post-crisis contexts.

Distinctively, SLM:

Frames legitimacy as ongoing and interactive, shaped through four dimensions: procedural justice, institutional trust, epistemic legitimacy, and relational governance.

Emphasizes multi-scalar applicability, from local to national and global levels.

Incorporates stakeholder salience to analyze how power, legitimacy, and urgency shift across crises (Mitchell et al., 1997).

Provides practical diagnostic tools to identify legitimacy breakdowns and chart pathways for restoration.

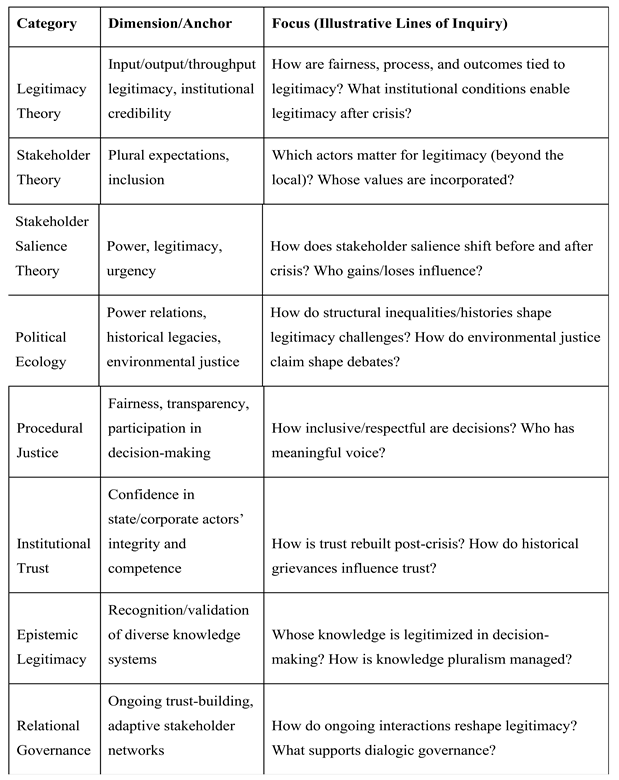

Table 2 outlines the theoretical anchors of SLM and illustrative lines of inquiry, showing how the framework can guide both scholarly analysis and policy practice.

By integrating these dimensions, the SLM framework proposes to offer a structured and adaptive lens for analyzing legitimacy in extractive governance. It intends to provide scholars and practitioners with a practical and conceptually robust approach for understanding, contesting, and reconstructing legitimacy—explicitly addressing systemic, multi-actor challenges that extend beyond project-level models.

6. Policy and Practice Implications

The findings suggest that the collapse of mining legitimacy in Panama reflects institutional fragility, opacity, and widespread distrust. Stakeholders in this study emphasized that transparency, capacity building, and inclusive participation are essential for restoring confidence, indicating that superficial consultation or one-off corporate responsibility initiatives are unlikely to be effective in isolation. The following recommendations outline possible policy pathways for operationalizing SLM’s core dimensions in Panama:

Institutionalize Binding Commitments: full implementation of Panama’s Escazú Agreement6 obligations—ensuring timely information access, participatory decision-making, and effective grievance mechanisms—could address core transparency and accountability concerns identified by participants.

Integrate Measurable Standards in Regulation: while interviewees expressed skepticism toward voluntary initiatives, frameworks such as Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM)7 – formally endorsed by the Panamanian Chamber of Mines, CAMIPA - and ICMM Performance Expectations provide reference points for responsible practice. Their integration into public regulation, alongside independent oversight, may enhance institutional credibility.

Illustrative Use of the IAP2 Spectrum for Public Engagement: to demonstrate a stepwise approach from informing to collaboration, this study adapts SLM to the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2)8 Spectrum as an example (IAP2, 2018). This globally recognized model can clarify how participation mechanisms might progress from simple information-sharing to empowered co-governance. Its use here is illustrative, pointing to options for incremental, context-sensitive reform, rather than prescribing a universal solution for Panama.

Build Capacity and Empower Stakeholders: long-term legitimacy is likely to require sustained investment in technical, legal, and monitoring skills for regulators, communities, Indigenous organizations, and civil society, to ensure meaningful participation and oversight.

Foster Multi-Actor Oversight Structures: aligning with SLM’s emphasis on relational governance, multi-actor oversight entities can support joint monitoring, deliberation, and accountability, but should be shaped by ongoing stakeholder input to reflect diverse perspectives and needs.

Create a Depoliticized Mining Authority: to address institutional fragility and restore credibility, stakeholders emphasized the need for an autonomous, professionalized body capable of regulating the mining sector at arm’s length from partisan politics. In collaboration with the previous government (2019 – 2024) the IDB proposed the establishment of such a depoliticized Mining Authority in Panama, to ensure consistency, technical rigor, and accountability in governance. Anchoring this authority in law—with transparent appointment processes, independent funding mechanisms, and structured stakeholder representation—could mitigate risks of political capture, strengthen institutional trust, and provide a stable foundation for long-term sector governance (IDB, 2023).

6.1. Adaptation of the IAP2 Spectrum

The following table presents the IAP2 model as an illustrative example of how the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework’s principles could be operationalized in practice. Each engagement level is aligned with legitimacy-building actions and potential applications for Panama’s mining governance. This adaptation is intended to demonstrate one possible pathway from basic information-sharing toward more collaborative and participatory processes, addressing interviews data.

Table 3.

Adapted IAP2 Spectrum for Advancing Social Legitimacy in Panama’s Mining Governance.

Table 3.

Adapted IAP2 Spectrum for Advancing Social Legitimacy in Panama’s Mining Governance.

| Level |

Community Promise |

Engagement Goal (within SLM) |

Examples Practices for Panama |

| Inform |

We will keep you informed, though this does not yet imply shared decision-making. |

Provide transparent, accessible information as a baseline for legitimacy (necessary but insufficient on its own). |

Public information portals on contracts, revenues, and monitoring data; open access to environmental impact assessments; site visits; disclosure consistent with Escazú obligations. |

| Consult |

We will listen and explain how your input influences decisions. |

Obtain stakeholder input on decisions and ensure visible feedback loops. |

Public hearings with published responses; accessible feedback mechanisms; surveys and summaries in culturally and linguistically appropriate formats. |

| Involve |

We will incorporate your concerns into decision-making. |

Strengthen epistemic legitimacy by validating diverse knowledge systems (technical, Indigenous, community-based). |

Stakeholder forums; technical workshops with communities; participatory mapping of biodiversity and water resources; integration of local knowledge into project design. |

| Collaborate |

We will co-develop options and solutions with you. |

Advance relational governance by fostering joint ownership of strategies and decisions. |

Joint advisory boards (government–industry–Indigenous–civil society); tripartite commissions for strategic planning; participatory monitoring aligned with TSM standards. |

| Empower |

We will make decisions together before implementation. |

Institutionalize shared authority in critical areas, ensuring affected groups have meaningful influence. |

Co-approval processes for high-risk decisions; Indigenous organizations with formal roles in governance structures relevant to their territories; community-led environmental monitoring with recognized authority in oversight. |

It is important to emphasize that successful operationalization of SLM in Panama will likely require approaches tailored to local institutional capacities and stakeholder preferences. The IAP2 spectrum is offered here as a conceptual aid for visualizing incremental shifts from transactional to participatory engagement, rather than as a definitive roadmap for restoring legitimacy.

In summary, while these recommendations and examples aim to provide practical entry points for advancing legitimacy and trust, any reform should remain adaptive and responsive to evolving governance challenges, building toward credible, collaborative, and context-appropriate institutions.

7. Conclusion

7.1. The Future of Mining and the Mining of the Future

Panama’s mining restrictions are more than a national controversy—it stands as a governance warning with lessons that extend far beyond its borders. The trajectory of extractive industries today is increasingly being shaped by the credibility of institutions, the inclusiveness of decision-making, and the trust built among stakeholders. In Panama, interviews revealed overwhelming demands for transparency (92%), institutional credibility (96%), and inclusive participation (over 70%). These are not peripheral concerns but central conditions for legitimacy.

Importantly, the consequences of weak governance extend beyond the extractive sector. The annulment of contracts and uncertainty around mining in Panama, have declined perceptions of security of investment, contributed to sovereign credit downgrades, and raised the cost of government borrowing on international bond markets. This demonstrates that governance failures reverberate across the entire economy, not just mining.

Stakeholders worldwide are demanding that extractive projects move beyond a narrow focus on resource exploitation to become multisectoral development drivers, aligned with long-term national and local aspirations. As the global energy transition accelerates demand for critical minerals, the message is clear: the mining of the future will depend not only on technical efficiency, but on legitimacy co-produced between governments, industry and society.

7.2. Contribution and Way Forward

This research makes three contributions. Empirically, it amplifies diverse stakeholder voices, demonstrating why Panama’s mining legitimacy collapsed in 2023 and what conditions are needed for reconstruction. Conceptually, it proposes the Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM) framework as a systemic, multi-actor alternative to project-based models like SLO and FPIC. Practically, it links findings to actionable pathways, illustrating how instruments like Escazú, TSM, ICMM, and the adapted IAP2 spectrum can be aligned within SLM to support reform. Together, these contributions highlight that legitimacy cannot be rebuilt through temporary fixes. It requires structural reforms, credible institutions, fair benefit-sharing, and long-term engagement resilient to political and market volatility. Further research should test and refine SLM in different jurisdictions, evaluating its capacity to deliver measurable governance and social outcomes.

Closing Reflection

Ultimately, the future of mining in Panama—and globally—will not be determined by the richness of its ore bodies, but by the credibility of its governance and the depth of its social legitimacy.

Funding

No external funding was received for this research.

Ethics Statement

This study did not require formal institutional ethics approval in Panama, as national

regulations governing research ethics apply primarily to biomedical and health-related research (Canario

Guzmán et al., 2022). Nonetheless, the research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

All participants provided informed consent prior to interviews, were assured of confidentiality, and had the

right to withdraw at any stage. Data was anonymized, securely stored, and used exclusively for academic

purposes.

Reflexivity and Limitations

The author’s background in mining governance and fluency in both Spanish and

English enabled privileged access to diverse perspectives but also required heightened reflexivity to minimize

potential bias (Berger, 2015). To uphold rigor throughout the research process, a reflexive journal was

maintained, the researcher’s professional background was transparently disclosed to all respondents, and

interview questions were deliberately designed to be neutral and open-ended. Spanish-language interviews,

transcripts, and any translations were carefully checked for accuracy. Research credibility was further

strengthened through member checking, peer debriefing, triangulation of interview, document, and media data,

and a fully documented audit trail of analytic decisions.

Despite purposeful and snowball sampling to maximize diversity, it is acknowledged that some highly

marginalized or dissenting voices may not be fully represented, and elite access was at times constrained by

political sensitivity. As with qualitative research generally, the findings are context-specific and not intended for

statistical generalization. All steps were taken to ensure analytic transparency, methodological integrity, and

critical self-awareness throughout the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and its supplementary material. Summarized anonymized interview data, codebooks, and NVivo-generated tables are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. However, due to ethical considerations, the confidentiality and privacy of respondents were assured, and therefore raw interview data provided by participants will be kept strictly confidential and cannot be shared.

Use of Artificial Intelligence Tools

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2025), Perplexity (2025), and Grammarly (2025) for language refinement and structure optimization, with Grammarly also providing grammar and style checking. Mendeley (Elsevier, 2025) was used for reference management and citation formatting. For literature organization, Google Scholar, Perplexity, and ChatGPT supported the structuring and summarization of academic and policy texts and were not used to generate original content. Whisper (OpenAI, 2025) improved the efficiency and accuracy of transcribing qualitative interviews. In the analytical phase, NVivo 15’s (QSR International, 2025) AI-assisted functions supported the organization and clustering of themes; however, all coding, interpretation, and theory-building decisions remained the sole responsibility of the author. At no stage were AI tools used to generate academic arguments, conduct analyses independently, or substitute for the researcher’s critical judgment. The author has reviewed and edited all outputs and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Acknowledgments

This article is influenced by research undertaken for the author’s proposed Doctor of Business Administration (DBA) dissertation at Royal Roads University. The author gratefully acknowledges the insights of all interview participants who contributed their time and perspectives to this study. Sincere appreciation is extended to Professor William Holmes (supervisor), Dr. Heather Hachigian, and Dr. Sean Irwin for their guidance throughout the DBA process. Special thanks are also given to Dr. Holmes and Dr. Stewart Redwood for generously reviewing the paper prior to submission. The author further wishes to recognize the inspiration of industry colleagues who embody integrity and commitment to responsible mining. In particular, Ana Juárez, President of Women in Mining Central America, and Stellamaris Tile, a Panamanian role model for women in mining, are acknowledged alongside the late David J. Hall and Brian Grant, who are remembered with gratitude. Together, they represent the many individuals whose example has shaped and encouraged this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

AI — Artificial Intelligence

CAMIPA — Cámara Minera de Panamá (Panamanian Chamber of Mining)

CoNEP — Consejo Nacional de la Empresa Privada (National Council of Private Enterprise, Panama)

ESG — Environmental, Social, and Governance

FPIC — Free, Prior and Informed Consent

GRI — Global Reporting Initiative

IAP2 — International Association for Public Participation

ICMM — International Council on Mining and Metals

IDB — Inter-American Development Bank

IFC — International Finance Corporation

IGF — Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development

ILO — International Labour Organization

IRMA — Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance

MAC — Mining Association of Canada

MP3 — MPEG Audio Layer-3 (digital audio format)

NGO(s) — Non-Governmental Organization(s)

NVivo — Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QSR International)

PDF — Portable Document Format

SDG(s) — Sustainable Development Goal(s)

SLO — Social License to Operate

SLM — Social Legitimacy for Mining

TSM — Towards Sustainable Mining

UNDP — United Nations Development Programme

UNDRIP — United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

UNSDG(s) — United Nations Sustainable Development Goal(s)

Appendix A: Stakeholder Distribution by Gender

Appendix B: Perceptions of Mining: Risk vs Opportunity

5 respondents (20%) → opportunity only

18 respondents (72%) → both opportunity & risk

2 respondents (8%) → risk only

0 respondents (0%) → neither

Appendix C: Top 10 most frequent words in interviews

Appendix D: List of Notable Quotes from Interviewees in No Specific Order

| Quotes |

| “There are examples of responsible mining in Latin America. Panama should learn from them instead of banning the sector outright.” |

| “The government simply does not have the capacity or credibility to monitor a project of this size. People assumed corruption, and trust collapsed.” |

| “When no clear data is available, people imagine the worst. Fear spreads faster than facts.” |

| “Mining could transform Panama’s economy if managed transparently. It brings revenues and jobs that no other sector can match.” |

| “The country cannot depend only on the Canal. Mining offers a chance to diversify and fund social programs.” |

| “With so much rain, tailings are simply too risky here. The climate itself makes mining unviable here.” |

| “Even if mining could help the economy, no one trusts the institutions to manage it fairly.” |

| “Without transparency, no reform will matter. People must see the numbers and the monitoring in real time.” |

| “People want a voice, not a checkbox consultation. Real inclusion means being part of decisions, not just informed after.” |

| “Unless rules outlast the five-year political cycle, nothing will change. Stability is part of legitimacy.” |

| “There are examples of responsible mining in Latin America. Panama should learn from them instead of banning the sector outright.” |

| “Without trusted information, people imagine the worst. If local governments were stronger, communities educated, and companies truly part of the community, mining could be seen differently.” |

| “If the community sees transparency, stronger institutions, and real benefits, mining could be accepted — but not under the old model of secrecy and corruption.” |

| “Communities paid the price in health and environment but saw no benefits — mining will only be accepted if people are included and truly see the results.” |

| “People saw wealth leaving the mine but not reaching their communities — if mining returns, it must bring real benefits and be managed with honesty.” |

| “Mining needs independent oversight and credible institutions to be seen as legitimate. Trust must be rebuilt step by step — and young voices must be part of shaping that change.” |

| “Mining needs to be seen as the multisectoral driver that it is, not only an extractive business.” |

| “People rejected mining not just for the contract, but because they don’t trust the government. Transparency is the key.” |

| “Without legal certainty and strong institutions, mining in Panama will always face rejection — contracts must be clear, transparent, and genuinely beneficial to the people.” |

| “Mining was not banned because of geology or economics, but because the state lost legitimacy — people no longer trusted the process. Without institutions that inspire confidence, no contract will ever be seen as acceptable.” |

| “For mining to be accepted, people must identify with it as they do with the Canal. That sense of ownership, supported by education and trust-building, could take a generation to achieve.” |

| “The contract fell because of distrust. Mining can only return if oversight improves and citizens see tangible benefits.” |

| “Institutional weakness opened the door for extremism and fake news. To regain trust, Panama needs strong institutions, education to prevent radical contagion, and long-term coherent policies that integrate government and industry.” |

| “Mining can regain acceptance if we improve communication, ensure transparency, and demonstrate clear benefits for society.” |

| “Just as the Canal gave Panamanians a sense of ownership, mining too must be seen as ours. But legitimacy will take a generation to be regained, it needs to be shaped by today values of equality, minority rights, and environmental protection.” |

| “If you can see the scar of Donoso from space on Google Maps, of course people are afraid — but with more education and transparency, in 5 or 10 years I believe mining could be accepted again.” |

| “The problem is not mining itself but doing it the wrong way — with weak laws, poor oversight, and without educating the population.” |

| “Mining could only return if our communities are part of the decisions, with real benefits and respect for our rights — otherwise, it will always be rejected.” |

| “Is it really worth sacrificing our ecosystems and the future of our children just to send copper abroad, while the people see no real benefit?” |

| “Even if mining could help the economy, no one trusts the institutions to manage it fairly.” |

| “The government has no credibility. People don’t believe in its ability to audit mining operations or enforce environmental protections.” |

| “Mining is a necessity in today’s world, but in Panama it should only proceed if the operations minimize negative impacts and protect biodiversity.” |

| “We cannot let short-term economic pressure undo the protection of our environment and our communities.” |

Appendix E: Cross-Case Comparative Matrix - Themes Summary

Appendix F: Codebook Sample

Notes

| 1 |

Procedural justice refers to the perceived fairness, transparency, and inclusivity of decision-making processes, especially as experienced by stakeholders involved in governance arrangements (Tyler, 2006; Bäckstrand, 2006). |

| 2 |

Cobre Panamá is operated by Minera Panamá S.A., a subsidiary of First Quantum Minerals Ltd., a Canadian mining company. |

| 3 |

In Catholic social teaching, “creation” refers to the natural environment and all living beings as part of God’s creation. The phrase “defense of creation” is commonly used by the Church to frame ecological protection as both a moral and spiritual responsibility (see Francis, 2015, Laudato Si’). |

| 4 |

|

| 5 |

Comparative analysis of frameworks: The Social License to Operate (SLO); Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC); and the proposed Social Legitimacy for Mining (SLM). |

| 6 |

The Escazú Agreement (2018) is a legally binding regional treaty for Latin America and the Caribbean that guarantees rights of access to environmental information, participation, and justice, and includes provisions to protect environmental defenders. |

| 7 |

Towards Sustainable Mining (TSM) is a performance-based sustainability program created by the Mining Association of Canada in 2004. It requires participating companies to measure and publicly report on environmental and social performance across areas such as tailings management, community engagement, and biodiversity, with external verification to ensure transparency. |

| 8 |

IAP2 is a global association established in 1990 that promotes the practice of inclusive, transparent, and effective decision-making processes by aligning public input with decision-making authority (IAP2, 2018). |

References

- Alvarez, S. A., Barney, J. B., & Wuebker, R. J. (2014). Realism in the study of entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review, 39(2), 227–233. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43699238.

- Arsel, M., Hogenboom, B., & Pellegrini, L. (2016). The extractive imperative and the boom in environmental conflicts at the end of the progressive cycle in Latin America. The Extractive Industries and Society, 3(4), 877–879. [CrossRef]

- Bäckstrand, K. (2006). Multi-stakeholder partnerships for sustainable development: Rethinking legitimacy, accountability and effectiveness. European Environment, 16(5), 290–306. [CrossRef]

- Bagg, S. (2022). Realism against legitimacy: For a radical, action-oriented political realism. Social Theory and Practice, 48(1), 29–60. [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A., Abdulai, A.-G., Bebbington, D. H., Hinfelaar, M., & Sanborn, C. A. (2018). Governing extractive industries: Politics, histories, ideas. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A., Fash, B., & Rogan, J. (2018). Socio-environmental Conflict, Political Settlements, and Mining Governance: A Cross-Border Comparison, El Salvador and Honduras. Latin American Perspectives, 46(2), 84-106. (Original work published 2019). [CrossRef]

- Beetham, D. (1991). Towards a social-scientific concept of legitimacy. In The legitimation of power (pp. 3–41). Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234. [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg. (2024, November 26). Panama’s debt downgraded by S&P to lowest investment grade. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-11-26/panama-s-debt-downgraded-by-s-p-to-lowest-investment-grade.

- Boiral, O., Heras-Saizarbitoria, I., & Brotherton, M. C. (2022). Sustainability management and social license to operate in the extractive industry: The cross-cultural gap with Indigenous communities. Sustainable Development, 31(1), 125–137. [CrossRef]

- Boutilier, R. (2014). Frequently asked questions about the social licence to operate. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 32(4), 263–272. [CrossRef]

- Breakey, H., Wood, G., & Sampford, C. (2025). Understanding and defining the social license to operate: Social acceptance, local values, overall moral legitimacy, and ‘moral authority.’ Resources Policy, 102, 105488. [CrossRef]

- Bridge, G. (2004). Contested terrain: Mining and the environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 29(1), 205–259. [CrossRef]

- Britannica. (2025). Panama: History, map, flag, capital, population, & facts. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Panama.

- Brueckner, M., & Eabrasu, M. (2018). Pinning down the social license to operate (SLO): The problem of normative complexity. Resources Policy, 59, 218–226. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, P. (2015, February 18). Mining & faith: Unexpected partnerships for prosperity. Clareo. https://clareo.com/mining-faith-unexpected-partnerships-for-prosperity/.

- Bull, J. W., Suttle, K. B., Gordon, A., Singh, N. J., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2013). Biodiversity offsets in theory and practice. Oryx, 47(3), 369–380. [CrossRef]

- CAMIPA. (2024). Factsheet: Mining in Panama. Cámara Minera de Panamá.

- Canario Guzmán, J. A., Orlich, J., Mendizábal-Cabrera, R., Ying, A., Vergès, C., Espinoza, E., Soriano, M., Cárcamo, E., Mendoza Marrero, E. R., Sepúlveda, R., Nieto Anderson, C., Feune de Colombi, N., Lescano, R., Pérez-Then, E., & et al. (2022). Strengthening research ethics governance and regulatory oversight in Central America and the Dominican Republic in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Health Research Policy and Systems, 20, Article 138. [CrossRef]

- CoNEP. (2024). Repercusiones socioeconómicas del cierre de operaciones de Cobre Panamá. Consejo Nacional de la Empresa Privada.

- CooperAccion. (2024). El proyecto El Algarrobo y Tambogrande. https://cooperaccion.org.pe/opinion/el-proyecto-el-algarrobo-y-tambogrande/.

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- David, H. Y. (2025, August 19). La Pastoral Minera: Una respuesta de la Iglesia a los desafíos de la minería [Unpublished conference presentation slides]. Conference on Formalization, Universidad Nacional de Piura, Piura, Peru.

- Dashwood, H. S. (2012). The rise of global corporate social responsibility: Mining and the spread of global norms. Cambridge University Press. [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91. [CrossRef]

- Dou, S., Xu, D., Zhu, Y., & Keenan, R. (2023). Critical mineral sustainable supply: Challenges and governance. Futures, 146, 103101. [CrossRef]

- Escobar, A. (2008). Territories of Difference: Place, Movements, Life, Redes. Durham: Duke University Press. [CrossRef]

- Francis. (2015). Laudato Si’: On care for our common home. Vatican Press.

- Franks, D. M., Davis, R., Bebbington, A. J., Ali, S. H., Kemp, D., & Scurrah, M. (2014). Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business costs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(21), 7576–7581. [CrossRef]

- Gifford, B., Kestler, A., & Anand, S. (2010). Building local legitimacy into corporate social responsibility: Gold mining firms in developing nations. Journal of World Business, 45(3), 304–311. [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). (2023). GRI 14: Mining sector standard. Global Reporting Initiative. https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/standards-development/sector-standard-for-mining/.

- Gómez, J. (2023). The mining moratorium in Panama: Economic impacts and social unrest. Latin American Policy Journal, 12(2), 24–31.

- Hall, N. L., Lacey, J., Carr-Cornish, S., & Dowd, A.-M. (2015). Social licence to operate: Understanding how a concept has been translated into practice in energy industries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 86, 301–310. [CrossRef]

- Helwege, A. (2015). Challenges with resolving mining conflicts in Latin America. The Extractive Industries and Society, 2(1), 73–84. [CrossRef]

- Hilson, G. (2012). Corporate social responsibility in the extractive industries: Experiences from developing countries. Resources Policy, 37(2), 131–137. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, W. R. (2008). A theoretical framework for the investigation of the determinants of corporate environmental policy. Interdisciplinary Environmental Review, 10(1–2), 110–147. [CrossRef]

- Imai, S., Mehranvar, L., & Sander, J. (2007). Breaching Indigenous law: Canadian mining in Guatemala. Indigenous Law Journal, 6(1), 31–66. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1267902.

- Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA). (2018). IRMA standard for responsible mining (Version 1.0). Section 2.2: Free, Prior and Informed Consent. https://responsiblemining.net/irma-standard.

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). (2018). Performance expectations. https://www.icmm.com/en-gb/our-principles/mining-principles/mining-principles.

- International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM). (2025). Achieving No Net Loss or Net Gain of Biodiversity: Good practice guide. https://www.icmm.com/achieving-nnl-or-ng-biodiversity.

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). (2021). Hacia una minería sostenible en Panamá.

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). (2023). Consorcio Gobernanza Minera Panamá, John T. Boyd Company, & International Trade Advisory Services. (2023, April 18). Reforma institucional y estratégica de la gobernanza del sector minero de Panamá: Socialización de avances y resultados del proyecto (Anexo 5 Fase 3). Inter-American Development Bank (BID), RG-T3553 Technical Proposal.

- International Finance Corporation (IFC). (2012). Performance standards on environmental and social sustainability. World Bank Group. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/sustainability-at-ifc/policies-standards/performance-standards.

- Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development (IGF). (2020). Mining Policy Framework Assessment: Panama (Assessment report). International Institute for Sustainable Development. Retrieved from https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2021-02/panama-mining-policy-framework-assessment-en.pdf.

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2024). Panama: Impacto económico de la minería. https://www.imf.org/es/News/Articles/2024/03/03/cs030324-panama-staff-concluding-statement-of-the-2024-article-iv-mission.

- International Association for Public Participation (IAP2). (2018). IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation. IAP2 International Federation. Retrieved from https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.iap2.org/resource/resmgr/pillars/spectrum_8.5x11_print.pdf.

- Kaasa, A., & Andriani, L. (2021). Determinants of institutional trust: The role of cultural context. Health Economics, Policy and Law, 16(1), 86–103. [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, L., & Soares de Oliveira, R. (2022, August). Supporting Good Governance of Extractive Industries in Politically Hostile Settings: Rethinking Approaches and Strategies (Discussion Paper). Columbia Center on Sustainable Investment. Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/sustainable_investment/4.

- Kemp, D., & Owen, J. R. (2013). Community relations and mining: Core to business but not “core business.” Resources Policy, 38(4), 523–531. [CrossRef]

- Kemp D, Owen Jr. Corporate Readiness and the Human Rights Risks of Applying FPIC in the Global Mining Industry. Business and Human Rights Journal. 2017;2(1):163-169. doi:10.1017/bhj.2016.28 . [CrossRef]

- Kemp, D., & Owen, J. R. (2017). Grievance handling at a foreign-owned mine in Southeast Asia. The Extractive Industries and Society, 4(1), 131–139. [CrossRef]

- Kung, A., Holcombe, S., Hamago, J., & Kemp, D. (2022). Indigenous co-ownership of mining projects: A preliminary framework for the critical examination of equity participation. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 40(4), 413–435. [CrossRef]

- Levi, M., Sacks, A., & Tyler, T. (2009). Conceptualizing legitimacy, measuring legitimating beliefs. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(3), 354–375. [CrossRef]

- López, M. (2023, October 21). La Iglesia se suma a las manifestaciones contra la explotación minera en Panamá. Vida Nueva Digital. https://www.vidanuevadigital.com/2023/10/21/la-iglesia-se-suma-a-las-manifestaciones-contra-la-explotacion-minera-en-panama/.