1. Introduction

Green cosmetics are sustainable self-care products based on biodegradable ingredients, mainly from plant sources, and environmentally friendly biotechnological tools [

1]. They mainly incorporate bioactive phytochemicals, herbal extracts, and plant oils (fixed and essential oils) [

2,

3,

4]. The extraction processes are based on advanced green chemistry techniques that preserve bioactivity, and they align with principles of sustainability, environmental protection, and consumer health consciousness [

5,

6]. The foundation of natural cosmetics represents a shift away from synthetic chemicals with harmful effects on human health [

7,

8,

9] toward bio-based, environmentally friendly alternatives that offer both efficacy and safety [

10]

Natural cosmetics primarily rely on botanical sources, including plant oils, essential oils, plant extracts, and bioactive phytochemicals (phenolics, polysaccharides, vitamins, etc), used in traditional medicine [

11,

12,

13]. They are based on ingredients that provide (i) antioxidant properties - protecting skin against oxidative stress [

14,

15]; (ii) photoprotection - natural UV absorbers [

16,

17]; (iii) anti-inflammatory effects - soothing irritated and inflamed skin [

18,

19,

20]; (iiii) anti-aging benefits - various bioactive compounds that address skin aging [

19,

21,

22].

Natural oils (rosehip, argan, olive, coconut, sweet almond, jojoba, grapeseed) are widely included in skin care products [

23,

24]. Jojoba oil (JO), a liquid wax obtained by cold-pressing seeds of

Simmondsia chinensis, has proven to be a particularly suitable ingredient for cosmetic products [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. Unlike other vegetable oils, JO has very low volatility and, in its pure form, contains only minimal amounts of volatile organic compounds [

30,

31]. It is mainly composed of long-chain wax esters, which confer oxidative stability, a long shelf life, and a non-greasy texture that is easily absorbed by the skin [

32,

33]. Its emollient properties and compatibility with human sebum make JO an excellent vehicle for incorporating bioactive compounds, allowing for stable, effective, and pleasant-to-apply formulations. Furthermore, the JO chemical composition makes it resistant to degradation at moderate temperatures and under light, thereby maintaining the bioactive properties of the added ingredients [

34,

35,

36]. Jojoba oil can also serve as a carrier for essential oils, reducing the risk of skin sensitivity and irritation, and acting synergistically with most of them [

37].

The complex composition of essential oils provides multiple benefits, including antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties, making them invaluable in cosmetic formulations [

38,

39,

40]. Moreover, cosmetic emulsions loaded with essential oils exhibit stability and self-preservation under various storage conditions [

41].

Lichens are rich in secondary metabolites with phenolic structure that contribute to neutralizing free radicals generated by UV exposure, thereby protecting cell membranes and skin lipids from peroxidation [

42,

43,

44]. The fruticose lichen

Usnea barbata (L.) F.H. Wigg contains bioactive phytochemicals such as phenolic compounds (depsides, depsidones, dibenzofurans) and polysaccharides [

45]. Previous studies obtained and investigated

U. barbata extracts in vegetable oils (sunflower and canola oil) [

46,

47]. The most active phenolic metabolite from

Usnea sp. is usnic acid [

48,

49], a dibenzofuran derivative known for its antimicrobial activity, antioxidant capacity, and ability to absorb UV radiation [

50,

51]. At the same time, lichen polysaccharides can stabilize various emulsion-type formulations and provide natural viscosity to oil extracts [

47,

52].

Recent findings from the scientific literature lead to the following hypotheses:

Therefore, the present study proposes an innovative approach to natural skin care products by preparing a complex plant-derived base, the U. barbata extract in JO enriched with 10% Vitamin E and 5% Peppermint oil (PEO). We investigated the bioactive phytochemicals in UBPJO and compared them with those in PEO and PJO. Then, the UBPJO physicochemical properties, including those essential for further cosmetic formulation and stability, were evaluated and compared with those of the oil base (PJO). Statistical analysis supports the results, suggesting that UBPJO could be safely used in the development of pharmaceutical formulations with appreciable stability and skin-protective properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Jojoba oil (JO) was obtained by cold pressing

Simmondsia chinensis (Link) C.K. Schneid. seeds and supplied by Fagron Hellas (Trikala, Greece). It is highly pure and suitable for cosmetic applications. Vitamin E was purchased from the same supplier. Peppermint essential oil (PEO) was purchased from Laboratoarele Fares Biovital SRL (Orastie, Romania); its CG-MS analysis was previously reported [

55]. It was diluted in the JO-Vitamin E combination (carrier oil) to 5%. The oily mixture (PJO) was obtained by stirring at 500 rpm for 10 minutes at room temperature (22°) using a Heidolph MR 3001K magnetic stirrer (Heidolph Instruments GmbH, Schwabach, Germany).

U. barbata lichen was harvested in March 2024 from the Călimani Mountains, Romania (47°28′ N, 25°13′ E, at an altitude of 900 m). The freshly collected lichen thalli were separated from impurities, then dried at 18–25 °C in an herbal room, protected from sunlight. Dried lichen preservation for an extended period was performed in similar conditions. It was identified by the Department of Pharmaceutical Botany of the Faculty of Pharmacy at Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy using standard methods. A voucher specimen is maintained in the Herbarium of the Pharmacognosy Department, Faculty of Pharmacy, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy (UBL 3/2024, Ph-UMFCD).

All chemicals, solvents, and reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2. Preparation of U. barbata Oil Extract

U. barbata extraction in PJO was performed by cold maceration, which preserves the integrity of bioactive compounds and prevents thermal degradation. The dried lichen thalli were ground and passed through successive 2.5 mm sieves (DIN 1171) and 1.2 mm mesh (DIN 117) for homogenization. Almost 20 g of this mass was accurately weighed using a Kern analytical balance, placed in a 1000 mL brown glass container, and 500 mL of PJO was added. The extraction process was performed in a light-protected location at a constant temperature (21-22 °C) for three months; the container was manually shaken daily [

47]. After this period, the oil extract (UBPJO) was filtered through cotton mesh gauze into a brown vessel with a sealed plug. The pH values of both oil samples (PJO and UBPJO) were determined using a CONSORT P601 pH meter (Consort Bvba, Turnhout, Belgium) equipped with an electrode. Then, the

U. barbata oil extract was preserved in a plant room, at 21-22 °C, sheltered from sunlight [

47].

2.3. GC-MS Analysis

The chemical composition of the PJO and UBPJO was analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) [

55]. The GC-MS analysis was performed on an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an Agilent 5975C Mass Selective Detector (MSD). A DB-5MS capillary column (30 m × 250 µm × 0.25 µm, 5% phenyl methyl siloxane) was used for separation. Sample injection was performed manually with a 0.5 µL syringe in split injection mode (100:1). The injection volume was 0.25 µL, and each sample was injected into triplicate to ensure reproducibility. The injector temperature was set at 250 °C, with helium as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The column temperature program was as follows: an initial temperature of 40 °C was held for 3 min, followed by a ramp of 10°C/min to 280 °C, which was maintained for 3 min, resulting in a total run time of 30 min. All these conditions are detailed in the Supplementary Material. The MS detector was operated in standard mode with the following parameters: electron-impact ionization and complete-scan acquisition. More detailed data are available in the Supplementary Material.

Data acquisition and processing were performed using the instrument’s software. The chemical constituent identification was achieved by comparing mass spectra with reference libraries and by retention-time matching.

2.4. Total Phenolic Content

The determination of total phenolic content (TPC) was performed using the Folin–Ciocalteu colorimetric method, as described by [

56]. All reagents were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). The samples (PJO and UBPJO) were diluted 1:1 (v/v) with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to ensure uniform dispersion and to maintain measurements within the calibration curve's linear range. Almost 50 μL of each sample was taken, to which 50 μL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, 450 μL of distilled water, and 500 μL of 7% (M/v) sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃) solution were added successively. The mixtures were homogenized and incubated in the dark for 50 minutes to allow the development of the blue color characteristic of the complex formed between the phenolic compounds and the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged for 5 minutes at 10000 rpm and 4°C to remove insoluble particles. Absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a FlexStation 3 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, GA, USA). The calibration curve was prepared under the same experimental conditions, using gallic acid as a reference standard, over the concentration range 12.5–250 µg/mL, yielding a linear correlation (R² = 0.9978). The results were expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE), reported as µg GAE/mL, and µg GAE/g of the oil sample, depending on the analyzed matrix.

2.5. FTIR Analysis

Fourier Infrared spectra were acquired using a Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (FT/IR-4200, JASCO, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory (ATR PRO450-S). Spectral measurements were performed over the wavenumber range of 4000 to 400 cm

-1, employing a spectral resolution of 4 cm

-1. All spectra of UBPJO and PJO were recorded at ambient temperature and presented as transmittance values [

57].

2.6. AFM Analysis

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) analysis of UBPJO and PJO was conducted as previously described [

58]. Oil samples (20 µL each) were diluted in 2 mL of 96% ethanol (Merk Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) and deposited onto clean glass substrates. The samples were then heated at 200 °C for 30 min to ensure proper adhesion and solvent evaporation. AFM imaging was performed in enhanced contrast mode, and the resulting line scans, displayed below the images, clearly illustrate the surface profiles of both oil samples [

54].

2.7. Heavy Metals Content

Heavy metals, arsenic (As) and lead (Pb), were identified in UBPJO and PJO using Graphite-Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry (GFAAS) [

59,

60,

61,

62].

2.7.1. Mineralization

The mineralization of oil samples was performed in the Ethos Easy microwave digestion system (oven). In each vial, the central part of a segment, approximately 0.300g of sample, 1 mL of 30% H2O2 solution, 9 mL of 69% HNO3 solution, and HPLC-grade water were added to allow detection of impurities at the ppb (µg/L) level. The oven is equipped with five mineralization segments/flasks, positions 1, 6, 7, 8, and 11. The sample is weighed on the analytical balance directly into the flask, then the volume of 30% hydrogen peroxide (1 mL) and 69% nitric acid (9 mL) is added, as indicated by the mineralization method from the library in the operating software of the device (always in the niche). – the method in the Palm Oil software. The first stage of the mineralization process lasts for 15 minutes, during which the temperature increases to 200° C in 5 segments, with the power set to a maximum of 1800W. The second stage also lasts 15 minutes, during which the temperature is maintained at 200°C. The power is set to 1800 W.

After complete mineralization, the vials (segments) are allowed to cool using the apparatus fans for approximately 10-15 minutes. After cooling, the segments containing the vials can be removed from the apparatus, and access to the vials with the processed sample is allowed after opening with the torque wrench.

The mineralized samples were analyzed using an atomic absorption spectrometer with the graphite furnace method.

2.7.2. GFAAS Analysis

All solutions were prepared with high-purity deionized water obtained with a Millipore model system. All glassware and polyethylene bottles were cleaned by soaking in 10% nitric acid and rinsed three times with deionized water. High-purity concentrated 69% nitric acid (Trace Grade assay) was supplied by Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany).

The high-purity standard stock solutions containing 1000 mg/L H3AsO4 in 0.5 M nitric acid and 1000 mg/L Pb(NO3)2 in 0.5 M nitric acid were purchased from Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany. A volume of 10 mL was taken from the 1000 mg/L stock solution, and successive dilutions were made to obtain the final concentration of 100 µg/mL, used for the 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 µg/L standards.

The platform was a SOLAAR 6M (Thermo Electron Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) atomic absorption spectrometer equipped with a deuterium lamp for background correction. The analysis was performed using the GFAAS technique with a graphite furnace system (GF95Z Zeeman) and an FS95 autosampler (Thermo Electron Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Thus, a graphite pyrolytic cuvette was used; the sample volume and the volumes of the injected standard solutions were 20 µL. The height of the autosampler capillary tip in the cuvette was adjusted by observing the injection through a camera positioned in the graphite furnace (GFTV), which was provided with the spectrometer.

Argon was used as a shielding gas throughout the determination at a flow rate of 0.2 L/min. The 4 stages in the temperature program were: stage 1 – drying; stage 2 – pyrolysis; stage 3 – atomization and determination; stage 4 – cleaning. The manufacturer provided the spectrometer parameters: the wavelengths for As and Pb were 193.7 nm and 283.3 nm, respectively. The calibration curve used the following As and Pb standards’ concentrations: 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 μg/L, thus ensuring a linearity coefficient (R

2) > 0.99. Detailed working parameters and the calibration curves for both heavy metals are included in the

Supplementary Materials.

The As and Pb concentrations in each oil sample were calculated from the corresponding regression line, namely, the absorbance as a function of concentration. All measurements were performed in duplicate.

2.8. Rheological Properties of the Oil Samples

The rheological determinations were made using a B One Plus rotary viscometer (Lamy Rheology Instruments), with an accuracy of ±1% of full scale and a repeatability of 2%. It is equipped with seven probes (spindles), identified by acronyms from RV1 to RV7, each measuring a specific viscosity range. The RV3 probe was used to determine oil viscosity by immersing it in 50 mL of each sample.

The measurements were performed at rotation speeds of 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 rpm for 10 seconds each; the temperature remained constant (22°).

The spreading behavior of all samples was assessed using an extensometer (Epsilon Technology Corp., Jackson, WY, USA) [

63]. Two glass plates were used; 0.5 g of oil was placed at the center of the lower plate. The upper plate, weighing 150 g, was added, and the diameter of the oil spread was measured. Then, weights of 50, 100, 200, and 500 g were gradually added, and, after 1 minute of rest, the diameter occupied by the oil sample was measured, and the area was calculated as πr

2.

2.9. Oxidation Stability

A significant issue that can shorten the shelf life and effectiveness of vegetable oils and their extracts is lipid auto-oxidation, particularly in formulations containing high levels of unsaturated oils or oxygen-sensitive compounds. The Velp OXITEST reactor (Velp Scientifica Srl, Usmate Velate, MB, Italy), which accelerates oxidation under controlled, repeatable conditions, was used to assess the oxidative stability of UBPJO and PJO by measuring the induction period. In the test, the samples are exposed to 90 °C and 6 atm of pure oxygen, conditions that increase oxidative stress. The oxidation chamber, where oxygen consumption is continuously monitored, was filled with 10 g of each sample. Oxygen consumed during oxidation reduces the chamber's internal pressure.

The duration (measured in hours and minutes) until a noticeable drop in oxygen pressure is observed, indicating the onset of strong oxidation, is known as the induction period (IP). This point is often associated with early signs of rancidity or changes in sensory and functional characteristics. It also coincides with the formation of primary oxidation products, such as hydroperoxides. The IP was determined using two methods: (i) the least squares method, which fits a curve to the oxygen consumption data, and (ii) the graphical method, which is used as an additional recalculation technique if necessary.

A more extended induction period suggests the oil sample is more resistant to oxidative deterioration and therefore has a longer shelf life under usual storage conditions. This metric is crucial for determining packaging, storage, and formulation optimization. It is significant for formulations containing plant oils, unsaturated fatty acids, or antioxidants.

2.10. Data Analysis

Almost all measurements were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility, and the results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Data analysis was performed using XLSTAT Premium v.2025.2.0.1232 (Lumivero, Denver, CO, USA) and Microsoft Excel v. 16.0 19328 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). ANOVA single-factor was used to detect significant differences between variables (p < 0.05), while Pearson Correlation established the correlation and covariance between oil sample constituents and physicochemical properties [

64].

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. U. barbata Oil Extract Density and pH

JO has a liquid wax composition, primarily long-chain esters (that confer an appreciable resistance to oxidation and rancidity), a non-greasy texture, and a high compatibility with human skin [

65]. Vitamin E, widely used in cosmetics, was chosen for its substantial antioxidant properties [

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71]. PEO was selected for its bioactivities (antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory), which are widely used in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals [

39,

72,

73]. Moreover, PEO can enhance the penetration of various chemicals at low concentrations with minimal skin irritation [

74,

75].

UBPJO has a lower density and a higher pH value than PJO (0.7786 g/mL and 6.25 vs. 0.8198 g/mL and 6.01, p>0.05). The previously prepared UBO (through maceration in Canola oil) had a significantly lower pH (almost 4, p<0.05) [

47]. These results demonstrate a slight effect of UB on extraction pH and a substantial impact of the oil carrier. The obtained pH values indicate compatibility with the skin [

76], confirming that UBPJO is suitable for topical applications.

3.2. GC-MS Analysis

The GC-MS analysis provided phytochemical profiles of both PJO and UBPJO, with notable qualitative and quantitative differences (

Table 1 and

Figure S1).

Both samples showed a predominant presence of monoterpene derivatives, such as L-limonene (PJO: 9.93%, UBPJO: 7.11%), L-menthone (PJO: 3.94%, UBPJO: 2.97%), and (-)-isomenthone / cis-p-menthan-3-one (PJO: 18.34%, UBPJO: 19.50%). Isomenthone content is the highest in PEO (26.52%, p<0.05). In the UBPJO, however, short-chain fatty acids were also detected, which can be attributed to the lipid fraction of U. barbata. These additional compounds highlight the successful incorporation of bioactive lichen constituents into the oil matrix.

Focusing on PEO terpenoid metabolism, derivatives of menthol and menthone, which are present in higher amounts in UBPJO than in PJO, can be explained by the fact that interconversion is possible under experimental conditions. Such transformations likely contribute to the observed increase in pulegone, ketones, and methylated ketones. Previous studies have reported similar pathways in plant metabolism, where enzymatic or chemical processes convert menthol and related terpenoids into bioactive ketone derivatives [

77,

78]. Indeed, PEO has a substantial content of isomenthol (55.09%) [

55]. However, neither PJO nor UBPJO contains isomenthol (

Table 1). Thus, it can be justified that the difference between the two samples in pulegone concentration, which approximately doubled from UBPJO to PJO (from 29.93% to 41.66% in the presence of

U. barbata). Pulegone is an optically active monoterpenoid cyclic ketone, a PEO constituent, and functions as an intermediate in the biosynthetic pathway of menthol [

79]. Pulegone content can increase when PEO is mixed with other compounds that influence its production pathway [

79,

80].

Similarly, the significant increase in pulegone content in UBJO can be partially attributed to chemical interactions among the various phytoconstituents of all three fractions, which promote chemical transformations, potentially through oxidation and methylation reactions, upon incorporation of

U. barbata. Many of the newly detected compounds in the mixture were identified as ketones or methylated oxygenated derivatives, suggesting that the combination of these compounds facilitates chemical transformations that cannot be observed in the individual components [

81].

Additional compounds were detected exclusively in the UBPJO, including short-chain fatty acids (1-nonanol, 0.51%), esters (2-dodecenyl acetate, 0.48%), and oxygenated terpenoids such as carvone (1.38%) and 8-hydroxy-p-menth-4-en-3-one (2.57%). These are likely the result of interactions between lichen metabolites and oil ones. Minor changes in other components, such as cis-

p-mentha-1,5,8-triene (PJO: 0.55%, UBPJO: 0.31%) and methyl eugenol (PJO: 1.63%, UBPJO: 0.95%), indicate subtle shifts in the volatile profile upon mixing and storage. The total area percentages were 96.78% for PJO and 95.24% for UBPJO, reflecting comprehensive detection of the main volatile and semi-volatile constituents. The observed compositional changes suggest that mixing and maceration, along with storage conditions, may induce bioactivation or chemical transformation, producing metabolites with potentially enhanced bioactivity. In plant extracts, such bioactivation can indicate both potential beneficial effects, such as antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, and possible toxicological implications [

82].

Overall, the GC/MS data confirm that the addition of U. barbata modifies the chemical profile of PJO, increasing the relative content of specific monoterpenes (e.g., pulegone) and introducing oxygenated compounds and fatty acids. These transformations provide a chemical basis for the UBPJO multifunctional properties and support its use in natural cosmetic formulations with enhanced bioactivity.

3.3. Total Phenolic Content

The results highlight significant differences in the total phenolic content between PJO and UBPJO. UBPJO had a significantly higher TPC content than PJO (

Table 2).

The significantly higher TPC in UBPJO vs. PJO (p<0.05) can be explained by the abundance of lichen secondary metabolites with a phenolic structure, of which the most important is usnic acid.

U. barbata extract in Canola oil had 0.915 mg/g usnic acid and TPC = 2.592 ± 0.097 mg PyE/g [

55].

PEG 400 showed an apparent signal of 260.49 ± 0.27 µg GAE/mL under the assay conditions (

Table 2), attributed to the background reactivity of the matrix, suggesting a non-specific reaction between the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and reducing compounds or minor impurities present in the PEG. To correct this, a matrix blank (PEG + DMSO) was used. The values for PJO and UBPJO are reported after subtracting the PEG contribution. To express the total phenolic content by mass, the volumetrically determined values (µg GAE/mL) were converted to µg GAE/g using the specific density of each sample. The densities were measured experimentally under the same temperature and composition conditions as in the Folin–Ciocalteu method.

Overall, PJO is a favorable carrier for the phenolic compounds of Usnea barbata, providing a matrix with superior antioxidant potential. PEO can enhance the penetration of phenolic lichen metabolites.

3.4. FTIR Analysis

The IR spectrum of PJO (

Figure 1A) is consistent with the presence of typical oil-derived chemical components. The intense peaks at 2921.6 cm⁻¹ (61%) and 2852.2 cm⁻¹ (71%) correspond to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the methylene (CH2) group. The peak at 1463.7 cm⁻¹ (86%) is attributed to the bending vibration of the methylene groups. The band at 721.2 cm⁻¹ (85%) is due to long-chain methylene rocking vibrations, confirming the presence of long fatty acid moieties (

Figure S2). The peak at 3003.6 cm⁻¹ (96%) is attributed to =C–H stretching, suggesting the presence of alkenyl groups and, by extension, unsaturated fatty acids.

The presence of the ester groups is proved by the strong band appearing at 1738.5 cm⁻¹ (76%), produced by the carbonyl (C=O) stretch vibration, while the C–O stretching vibrations are present at 1170.6 cm⁻¹ (84%) and at 1118.5 cm⁻¹ (93%). The spectra also indicate that the free acids are below the detection limit, as evidenced by the lack of the characteristic broad O–H band in the range 3500 to 2500, produced by hydroxyl stretching. Another indication is the absence of a second carbonyl stretch at a lower wavelength, characteristic of the carboxyl group.

The relatively simple IR spectrum, characterized by narrow and well-resolved peaks, suggests the predominance of fatty acid esters. In contrast, triglycerides typically exhibit broader peaks due to greater chemical diversity and conformational heterogeneity. The UBPJO spectrum differs slightly from that of PJO (

Figure 1B).

3.4. Atomic Force Microscopy Analysis

The AFM images of the two oil samples (PJO and UBPJO) are shown in

Figure 2: PJO (

Figure 2A,B) and UBPJO (

Figure 2C,D). The corresponding line scans, representing the surface profiles, are plotted at the positions indicated by the horizontal red lines in each image, highlighting differences in topography and nanoscale structure between the two samples.

The 2D-AFM images are scanned over areas of (10 × 10) μm² and (2 × 2) μm².

For PJO, the surface morphology appears with a heterogeneous texture characterized by uniformly distributed peaks (ridges) and valleys (

Figure 2A,B). The line scans plotted along the marked horizontal red lines confirm this morphology, revealing moderate topographical irregularities. The roughness parameters (Rq and Rpv) obtained for these samples across the entire scanned area (

Figure 2E,F) support the visual observation of the oils' corrugated surface.

The addition of

U. barbata led to a distinct modification of the PJO morphology (

Figure 2C,D). The surface morphology exhibits a notable smoothing effect. The line scans indicate lower oscillation amplitudes, reflected in lower Rq and Rpv values than for PJO (

Figure 2G,H). These findings suggest that

U. barbata interacts with the oil matrix, leading to structural rearrangements that contribute to a compact surface.

A more homogeneous oil formulation is expected to exhibit enhanced stability over time, as reduced corrugation minimizes aggregation and phase separation. Therefore, AFM analysis not only confirms the successful incorporation of U. barbata into the PJO matrix but also suggests improved nanoscale structural uniformity.

3.5. Heavy Metals Content

The results are expressed in both measurement units (μg/L and μg/g) and are illustrated in

Table 3. Heavy metals (As and Pb) content (ug/g) is higher in UBPJO than PJO (0.174 and 0.053 vs. 0.157 and 0.051).

The concentrations determined for arsenic ranged from 0.157 to 0.174 µg/g, The values recorded are slightly above the permissible limit of 0.10 µg/g, established by Regulation (EC) No. 1881/2006 and the Codex Alimentarius (FAO/WHO) for foodstuffs, but remain within a range considered safe for cosmetic or unrefined vegetable oils [

83].

The results obtained are consistent with the values reported in recent literature, whereas As concentrations in vegetable oils generally range between 0.05 and 0.20 mg/kg [

84]

However, Zhu et al. [

85], found arsenic levels ranging from 0.009 to 0.019 µg/g (~9–19 µg/kg) in various edible vegetable oils (sunflower, olive, peanut, etc.) consumed in China, establishing the daily safe use of these oils.

Both oil samples have Pb content < 0.052 µg/g, i.e. approximately half of the maximum permitted limit of 0.100 µg/g set by Regulation (EC) No. 1881/2006 for lead in vegetable oils and fats [

86].

The samples analyzed are well below the maximum permitted threshold, demonstrating compliance with European safety requirements. The values obtained are also consistent with data reported in recent literature, where typical Pb concentrations in vegetable oils range from 10 to 80 µg/kg. This correlation confirms the accuracy of the method used and the absence of external contamination in the analyzed samples. Therefore, the HNO₃/H₂O₂ mineralization method in the Ethos Easy microwave system, combined with GFAAS detection, proved efficient, reproducible, and sensitive for determining trace levels of heavy metals in vegetable oils [

87].

In a similar study, Tayeb et al. [

88], detected high amounts of Pb in various commercial and traditional oils (commercial olive oil: ~13.27 ± 3.37 µg/kg; traditional olive oil: ~17.48 ± 4.82 µg/kg; commercial corn oil: ~19.27 ± 8.12 µg/kg; traditional corn oil: ~32.40 ± 6.13 µg/kg), highlighting the importance of monitoring heavy metals in vegetable oils.

3.6. Rheological Properties

Rheology is an essential tool in the design and analysis of complex cosmetic formulations, given the inherent characteristics of their application, which involve processes of flow and deformation [

89]. The sensory texture of these cosmetic products is often closely linked to rheological measurements, providing valuable insights into their feel and performance. Furthermore, rheology serves as a revealing lens, illuminating the physical and chemical properties, as well as the microstructural nuances, of these formulations. Consequently, it has become a vital metric for assessing stability, ensuring that each product not only delights the senses but also endures over time [

90].

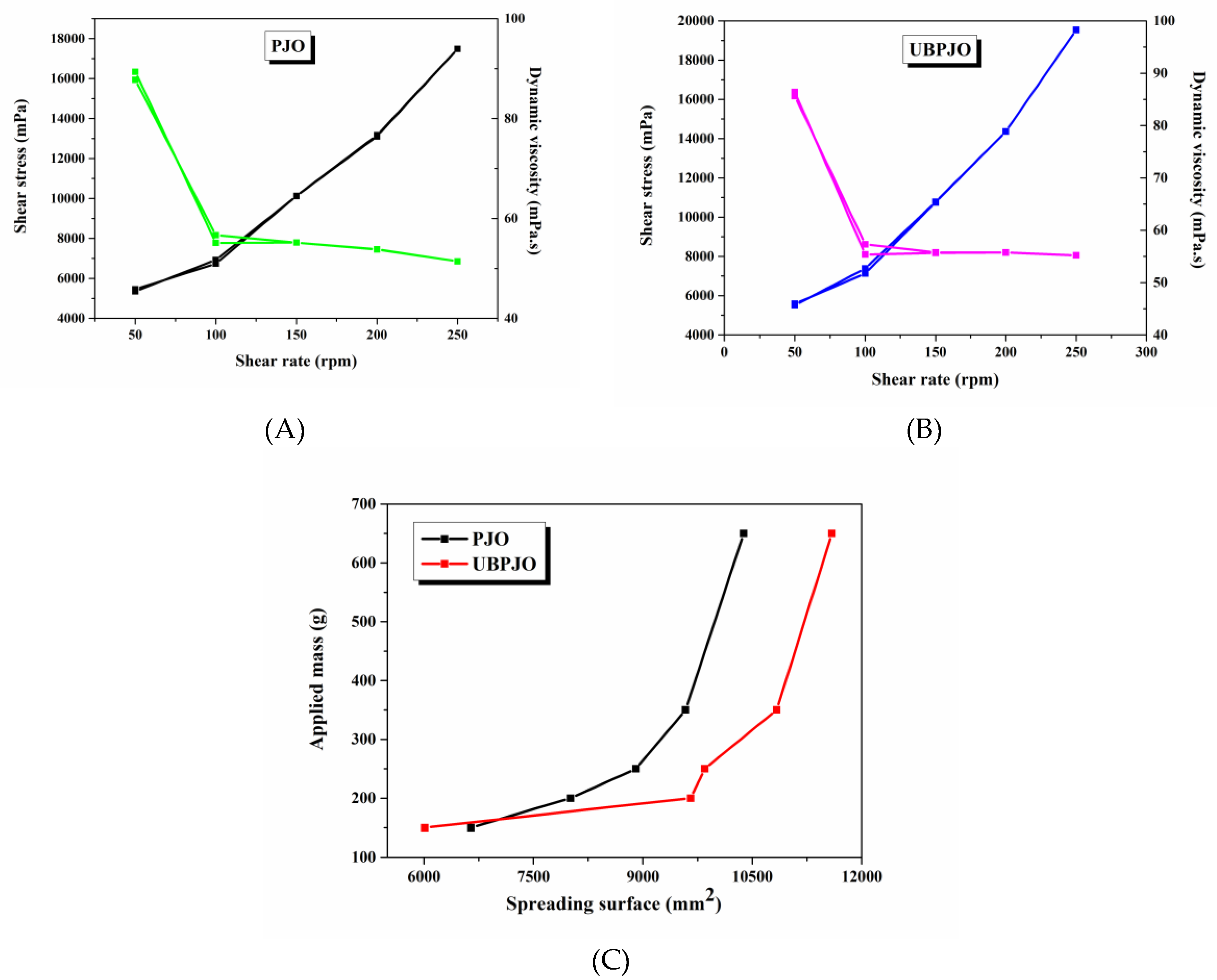

The difference in viscosity between the two samples is not very pronounced, given their similar densities. Generally, the shear stress is slightly higher at UBPJO vs. PJO (10.598±4765 vs. 9830±4510,

p > 0.05;

Figure 3A, B, and

Table S1). The same for dynamic and kinematic viscosities (UBPJO vs. PJO: 62.5±13.3 vs. 62±15.1;

p > 0.05;

Figure 3A, B, and

Table S1).

The viscosity dynamics of oily extracts at different shear rates are essential for determining their deformation behavior and flowability when included in various topical formulations [

91].

The phytochemical composition of vegetable oils is the key factor influencing their viscosity. Depending on the compounds included, the oils can behave as Newtonian or non-Newtonian fluids [

92]. Newtonian oils have predictable and straightforward flowability, while non-Newtonian oils can behave differently depending on the shear rate.

All samples exhibited initial non-Newtonian fluidity, but their performance at high shear rates differed. PJO exhibits pseudoplastic behavior, with viscosity decreasing continuously with increasing shear rate. Meanwhile, UBPJO displays the same behavior up to 150 rpm, then remains constant in the 150–250 rpm range, indicating a transition to Newtonian fluidity. Still, both samples exhibit thixotropic character, with viscosity recovering as shear is withdrawn (

Table S1). These findings are relevant for understanding the behavior of the oils in various future topical formulations and for selecting the manufacturing process type and parameters.

Although after applying the upper plate, the stretching surface of UBPJO is lower than that of PJO. Later, when additional weights are added, the extensibility of UBPJO becomes greater than that of PJO (9587±2146 vs. 8704±1445, p > 0.05;

Figure 3C, and

Table S2). The spreadability of the samples aligns with their viscosity behavior, indicating that UBPJO will likely spread quickly and evenly over the skin surface without requiring high pressure. Additionally, the extensibility reflects the behavior of the oil when incorporated into other fluid or semisolid systems. The results demonstrate that UBPJO can uniformly spread across different carriers without requiring high energy. Formulation cohesiveness determines extensibility performance, and UB was found to preserve the structural properties and flexibility of PJO while providing only a minor improvement in spreading ability. Gobi R. et al. [

93], have shown that viscoelastic properties strongly influence adhesion qualities. A significant correlation between the spreading and viscoelastic properties of UBPJO is observed, similar to PJO. Nevertheless, based on the recorded slight differences, it can be concluded that UB constituents form new interparticle bonds in the oily system, as reflected in changes in rheological attributes.

3.7. Oxidation Stability

The quantitative assessment of oxidative stability is represented by the induction period (IP), measured in hours, determined as the time at which the tangent lines drawn before and after the inflection point intersect. This indicates the time required to reach the oxidation starting point, which can be either a noticeable degree of rancidity or an abrupt shift in oxidation rate. It is considered that the longer the IP, the greater the oxidation resistance and the longer the shelf life [

94].

The recorded IP for PJO was 137.35 ± 8.22 h, and for UBPJO it was 153.02 ± 6.16 h. Although the difference is not substantial, with an increase of only 11%, it can be observed that

U. barbata has a beneficial influence on the lipid peroxidation resistance of PJO. This phenomenon can be explained by the presence of a higher amount of lichen secondary metabolites with phenolic structure, which significantly contribute to the improvement of the oxidative stability of oils [

95].

However, both oil samples have strong oxidative resistance, as their IP values are much higher compared to other vegetable oils, such as sunflower seed oil (IP = 62.60 h), walnut oil (IP = 44.47 h), or almond oil (IP = 85.00 h) [

96]. Besides, vitamin E is known as a potent antioxidant [

97].

Based on the recorded results, both samples have a long shelf life, making them suitable for long-term use and storage. Moreover, incorporating them into topical products can ensure both technological and biological antioxidant potential.

3.8. Data Analysis

Pearson's correlation was applied to all variables, and the correlation coefficient (r), p-value, and determination coefficient (R2) were calculated and graphically represented in Figure 5. The detailed statistical analysis is available in Excel version in the Supplementary Material.

Isomenthone, pulegone, hydroxy-

p-menthone, TPC, As, and Pb show substantial positive correlations with pH, kinematic and dynamic viscosity, and oxidative stability (

r > 0.999, p < 0.0001 or p = 0.000), and considerable negative correlations with density and shear stress (

r < –0.999,

p < 0.0001,

p = 0.000; Figure 5A). L-limonene, estragole, and L-menthone report a significant positive correlation with density and shear stress (r > 0.999,

p < 0.0001,

p = 0.000) and a considerable negative correlation with pH, kinematic and dynamic viscosity, and oxidative stability (

r < –0.999,

p < 0.0001,

p = 0.000; Figure 5A). Physicochemical properties of oil extracts are highly intercorrelated. Density shows a remarkable negative correlation with pH, kinematic and dynamic viscosity, spreadability, and oxidative stability (

r < –0.999,

p < 0.0001,

p = 0.000; Figure 5A). Oxidative stability highlights a significant positive correlation with pH, and kinematic and dynamic viscosity (

r > 0.999,

p = 0.000;

Figure 4A).

Significant correlations also reveal strong interdependence, as reflected in high values of the coefficient of determination (R

2), which ranged from 0.778 to 1 (

Figure 4B).

5. Conclusions

The present study investigated a complex and original oil lichen extract (U. barbata in Jojoba oil enriched with 10% Vitamin E and 5% Peppermint essential oil), with potential applications in the cosmetic field. The results obtained offer promising perspectives for further development of multifunctional cosmetic formulations based on rheological characteristics. The high oxidative stability of the oil lichen extract may ensure satisfactory self-preservation properties in subsequent skin care preparations. The identified bioactive phytochemicals could protect the skin against oxidative stress and UV radiation, maintain hydration, and support skin health through their antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Advanced study in this direction should focus on confirming these qualities, previously reported for each constituent.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.D., E.A.O., and D.L.; methodology, M.A.D., O.C., V.P., A.M.M., G.M.N., M.A., E.A.O., I.C.M., C.M.G., D.L.B., D.U., M.H., A.F.P., and D.L.; software, V.P.; validation, O.C., A.M.M., G.M.N., M.A., D.L.B., M.H., and D.L.; formal analysis, V.P.; investigation, M.A.D., O.C., V.P., A.M.M., G.M.N., M.A., E.A.O., I.C.M., C.M.G., D.L.B., D.U., M.H., A.F.P., A.R.U., and D.L.; resources, M.A.D., O.C., V.P., A.M.M., G.M.N., M.A., E.A.O., I.C.M., C.M.G., D.L.B., D.U., M.H., A.F.P., A.R.U., and D.L.; data curation, V.P, A.M.M., and D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.D., O.C., V.P., A.M.M., G.M.N., M.A., E.A.O., I.C.M., C.M.G., D.L.B., D.U., M.H., A.F.P., A.R.U., and D.L.; writing—review and editing, V.P, A.M.M., and E.A.O.; visualization, M.A.D., O.C., V.P., A.M.M., G.M.N., M.A., E.A.O., I.C.M., C.M.G., D.L.B., D.U., M.H., A.F.P., A.R.U., and D.L.; supervision, D.L.; project administration, D.L.; funding acquisition, M.A.D., V.P., E.A.O., and D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was supported by the Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pitaloka, L.K.; Marpaung, G.N.; Widia, S. The Eco-Beauty Movement: A Deep Dive into Millennial Green Cosmetic Purchases. Review of Applied Socio-Economic Research 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amro, B.I.; Abu Hajleh, M.N.; Afifi, F. Evidence-Based Potential of Some Edible, Medicinal and Aromatic Plants as Safe Cosmetics and Cosmeceuticals. Tropical Journal of Natural Product Research 2021, 5, 16–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz do Nascimento, L.; de Moraes, A.A.B.; da Costa, K.S.; Pereira Galúcio, J.M.; Taube, P.S.; Costa, C.M.L.; Neves Cruz, J.; de Aguiar Andrade, E.H.; Faria, L.J.G. de Bioactive Natural Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Essential Oils from Spice Plants: New Findings and Potential Applications. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, K.; Aburjai, T.; Al-Mamoori, F.; Schmidt, M. Plants with Cosmetic Uses. Phytotherapy Research 2023, 37, 5755–5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, Y.B.; Ahamed, A.F.M.J. What Influences Green Cosmetics Purchase Intention and Behavior? A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca, C.C.V.; Ueno, H.M. Green Cosmetics: Perspectives and Challenges in the Context of Green Chemistry. Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente 2020, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. An Insight into Toxicity and Human-Health-Related Adverse Consequences of Cosmeceuticals — A Review. Science of the Total Environment 2019, 670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athar, M. Detrimental Effects of Perfumes, Aroma & Cosmetics. Journal of Dermatology & Cosmetology 2020, 4, 42–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G. Toxics in Cosmetics: Chemical Properties, Impact Mechanism and Clinical Cases Derived from Major Chemical Components. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology 2023, 36, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, R.; Acerbi, F.; Fumagalli, L.; Taisch, M. Sustainability Paradigm in the Cosmetics Industry: State of the Art. Cleaner Waste Systems 2022, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saive, M.; Frederich, M.; Fauconnier, M.L. Plants Used in Traditional Medicine and Cosmetics in Mayotte Island (France): An Ethnobotanical Study. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge 2018, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Nadia, S.; Hamza, E.F.; Asma, H.; Abdelhamid, Z.; Lhoussaine, E.R. Traditional Knowledge of Medicinal Plants Used for Cosmetic Purposes in The Fez-Meknes Region. Tropical Journal of Natural Product Research 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Ho, R.; Butaud, J.-F.; Filaire, E.; Ranouille, E.; Berthon, J.-Y.; Raharivelomanana, P. A Selection of Eleven Plants Used as Traditional Polynesian Cosmetics and Their Development Potential as Anti-Aging Ingredients, Hair Growth Promoters and Whitening Products. J Ethnopharmacol 2019, 245, 112159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima Cherubim, D.J.; Buzanello Martins, C.V.; Oliveira Fariña, L.; da Silva de Lucca, R.A. Polyphenols as Natural Antioxidants in Cosmetics Applications. J Cosmet Dermatol 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiari-Andréo, B.G.; Trovatti, E.; Marto, J.; De Almeida-Cincotto, M.G.J.; Melero, A.; Corrêa, M.A.; Chiavacci, L.A.; Ribeiro, H.; Garrigues, T.; Isaac, V.L.B. Guava: Phytochemical Composition of a Potential Source of Antioxidants for Cosmetic and/or Dermatological Applications. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2017, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giossi, C.; Cartaxana, P.; Cruz, S. Photoprotective Role of Neoxanthin in Plants and Algae. Molecules 2020, 25, 4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna-Perez, Y.; Puertas-Mejia, M.A.; Mejia-Giraldo, J.C. Marine Macroalgae: A Source of Chemical Compounds with Photoprotective and Antiaging Capacity—an Updated Review. J Appl Pharm Sci 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawid-Pać, R. Medicinal Plants Used in Treatment of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Advances in Dermatology and Allergology 2013, 3, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, B. Skin Health Promoting Effects of Natural Polysaccharides and Their Potential Application in the Cosmetic Industry. Polysaccharides 2022, 3, 818–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Pintado, M.; Tavaria, F.K. A Systematic Review of Natural Products for Skin Applications: Targeting Inflammation, Wound Healing, and Photo-Aging. Phytomedicine 2023, 115, 154824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, J.; Ojcius, D.M.; Ko, Y.; Chang, C.; Young, J.D. Antiaging Effects of Bioactive Molecules Isolated from Plants and Fungi. Med Res Rev 2019, 39, 1515–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zofia, N.Ł.; Martyna, Z.D.; Aleksandra, Z.; Tomasz, B. Comparison of the Antiaging and Protective Properties of Plants from the Apiaceae Family. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullen, R.L. The Benefits and Challenges of Treating Skin with Natural Oils. Int J Cosmet Sci 2024, 46, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.C.; Nyam, K.L. Application of Seed Oils and Its Bioactive Compounds in Sunscreen Formulations. J Am Oil Chem Soc 2021, 98, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J. V; Terpak, N.; Massard, S.; Schwartz, A.; Bojanowski, K. Passive Enhancement of Retinol Skin Penetration by Jojoba Oil Measured Using the Skin Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeation Assay (Skin-PAMPA): A Pilot Study. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2023, Volume 16, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galus, S.; Karwacka, M.; Ciurzyńska, A.; Janowicz, M. Effect of Drying Conditions and Jojoba Oil Incorporation on the Selected Physical Properties of Hydrogel Whey Protein-Based Edible Films. Gels 2024, 10, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, S.; Aroua, M.K.; Gew, L.T. A Comprehensive Review of Plant-Based Cosmetic Oils (Virgin Coconut Oil, Olive Oil, Argan Oil, and Jojoba Oil): Chemical and Biological Properties and Their Cosmeceutical Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 44019–44032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietel, Z.; Melamed, S.; Ogen-Shtern, N.; Eretz-Kdosha, N.; Silberstein, E.; Ayzenberg, T.; Dag, A.; Cohen, G. Topical Application of Jojoba (Simmondsia Chinensis L.) Wax Enhances the Synthesis of pro-Collagen III and Hyaluronic Acid and Reduces Inflammation in the Ex-Vivo Human Skin Organ Culture Model. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Ma, S.; Tominaga, T.; Yokoyama, K.; Kitatani, K.; Horikawa, K.; Suzuki, K. Acute Effects of Transdermal Administration of Jojoba Oil on Lipid Metabolism in Mice. Medicina (B Aires) 2019, 55, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, S.; Vishnupriya, V.; Gayathri, R. Phytochemical Analysis and In Vitro Antioxidant Activity of Jojoba Oil. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2016, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Gad, H.A.; Roberts, A.; Hamzi, S.H.; Gad, H.A.; Touiss, I.; Altyar, A.E.; Kensara, O.A.; Ashour, M.L. Jojoba Oil: An Updated Comprehensive Review on Chemistry, Pharmaceutical Uses, and Toxicity. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchimoto, S.; Sakai, H.; Fukui, K. Oxidative Stability and Antioxidant Activity of Crude Jojoba Oil. BPB Reports 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahaan, A.P.; Rohaeti, E.; Muddathir, A.M.; Batubara, I. Antioxidant Activity of Jojoba (Simmondsia Chinensis) Seed Residue Extract. Biosaintifika 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.A.; Nordin, F.N.M.; Zakaria, Z.; Abu Bakar, N.K. A Systematic Literature Review on the Current Detection Tools for Authentication Analysis of Cosmetic Ingredients. J Cosmet Dermatol 2022, 21, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Dréau, Y.; Dupuy, N.; Gaydou, V.; Joachim, J.; Kister, J. Study of Jojoba Oil Aging by FTIR. Anal Chim Acta 2009, 642, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belostozky, A.; Bretler, S.; Kolitz-Domb, M.; Grinberg, I.; Margel, S. Solidification of Oil Liquids by Encapsulation within Porous Hollow Silica Microspheres of Narrow Size Distribution for Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 97, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.Y.; Park, M.A.; Kim, Y.C. Peppermint Oil Promotes Hair Growth without Toxic Signs. Toxicol Res 2014, 30, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelan, U.S.; de Oliveira, A.C.; Cacoci, É.S.P.; Martins, T.E.A.; Giacon, V.M.; Velasco, M.V.R.; Lima, C.R.R. de C. Potential Use of Essential Oils in Cosmetic and Dermatological Hair Products: A Review. J Cosmet Dermatol 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syaharani, C.P.S.; Isnaini, N.; Harnelly, E.; Prajaputra, V.; Maryam, S.; Gani, F.A. A Systematic Review: Formulation of Facial Wash Containing Essential Oil. Journal of Patchouli and Essential Oil Products 2023, 2, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kumar, V.; Mittal, C.; Rana, V.; Dabral, K.; Parveen, G. Role of Essential Oil Used Pharmaceutical Cosmetic Product. Journal for Research in Applied Sciences and Biotechnology 2023, 2, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkreli, R.; Terziu, R.; Memushaj, L.; Dhamo, K.; Malaj, L. Selected Essential Oils as Natural Ingredients in Cosmetic Emulsions: Development, Stability Testing and Antimicrobial Activity. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research 2023, 57, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesta, A.R.; N, R.; Kanivebagilu, V.S. Assessment of Antimicrobial Activity of Ethanolic Extraction of Usnea Ghattensis and Usnea Undulata. Int J Res Ayurveda Pharm 2020, 11, 75–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Míguez, F.; Schiefelbein, U.; Karsten, U.; García-Plazaola, J.I.; Gustavs, L. Unraveling the Photoprotective Response of Lichenized and Free-Living Green Algae (Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta) to Photochilling Stress. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millot, M.; Di Meo, F.; Tomasi, S.; Boustie, J.; Trouillas, P. Photoprotective Capacities of Lichen Metabolites: A Joint Theoretical and Experimental Study. J Photochem Photobiol B 2012, 111, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žugić, A.; Tadić, V.; Kundaković, T.; Savić, S. Chemical Composition and Biological Activities of the Extracts and Secondary Metabolites of Lichens Belonging to the Genus Usnea, Parmeliaceae. Lekovite sirovine 2018, 38, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basiouni, S.; Fayed, M.A.A.; Tarabees, R.; El-Sayed, M.; Elkhatam, A.; Töllner, K.R.; Hessel, M.; Geisberger, T.; Huber, C.; Eisenreich, W.; et al. Characterization of Sunflower Oil Extracts from the Lichen Usnea Barbata. Metabolites 2020, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popovici, V.; Bucur, L.; Gîrd, C.E.; Rambu, D.; Calcan, S.I.; Cucolea, E.I.; Costache, T.; Ungureanu-Iuga, M.; Oroian, M.; Mironeasa, S.; et al. Antioxidant, Cytotoxic, and Rheological Properties of Canola Oil Extract of Usnea Barbata (L.) Weber Ex F. H. Wigg from Călimani Mountains, Romania. Plants 2022, 11, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorðević, S.; Ivanović, J.; Kukić-Marković, J.; Petrović, S.; Žižović, I.; Tadić, V.; Marković, G. HPLC Determination of Usnic Acid Content in Different Extracts of Usnea Barbata. Planta Med 2010, 76, LS1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovici, V.; Bucur, L.; Popescu, A.; Caraiane, A.; Badea, V. Determination of the Content in Usnic Acid and Polyphenols from the Extracts of Usnea Barbata L. And the Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Activity. Farmacia 2018, 66, 337–341. [Google Scholar]

- Varol, M.; Tay, T.; Candan, M.; Türk, A.; Koparal, A.T. Evaluation of the Sunscreen Lichen Substances Usnic Acid and Atranorin. Biocell 2015, 39, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Galanty, A.; Popiół, J.; Paczkowska-Walendowska, M.; Studzińska-Sroka, E.; Paśko, P.; Cielecka-Piontek, J.; Pękala, E.; Podolak, I. (+)-Usnic Acid as a Promising Candidate for a Safe and Stable Topical Photoprotective Agent. Molecules 2021, 26, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halici, M.; Odabasoglu, F.; Suleyman, H.; Cakir, A.; Aslan, A.; Bayir, Y. Effects of Water Extract of Usnea Longissima on Antioxidant Enzyme Activity and Mucosal Damage Caused by Indomethacin in Rats. Phytomedicine 2005, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luzina, O.A.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Usnic Acid and Its Derivatives for Pharmaceutical Use: A Patent Review (2000–2017). Expert Opin Ther Pat 2018, 28, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovici, V.; Matei, E.; Cozaru, G.C.; Bucur, L.; Gîrd, C.E.; Schröder, V.; Ozon, E.A.; Karampelas, O.; Musuc, A.M.; Atkinson, I.; et al. Evaluation of Usnea Barbata ( L.) Weber Ex F. H. Wigg Extract in Canola Oil Loaded in Bioadhesive Oral Films for Potential Applications in Oral Cavity Infections and Malignancy. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagu, R.; Popovici, V.; Ionescu, L.-E.; Ordeanu, V.; Biță, A.; Popescu, D.M.; Ozon, E.A.; Gîrd, C.E. Phytochemical Screening and Antibacterial Activity of Commercially Available Essential Oils Combinations with Conventional Antibiotics against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Folin-Ciocalteu Method for the Measurement of Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Capacity; Measurement of Antioxidant Activity and Capacity: Recent Trends and Applications, 2017; pp. 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovici, V.; Matei, E.; Cozaru, G.; Bucur, L.; Gîrd, C.E.; Schröder, V.; Ozon, E.A.; Sarbu, I.; Musuc, A.M.; Atkinson, I.; et al. Formulation and Development of Bioadhesive Oral Films Containing Usnea Barbata ( L.) F. H. Wigg Dry Ethanol Extract ( F-UBE-HPC ) with Antimicrobial and Anticancer Properties for Potential Use in Oral Cancer Complementary Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, A.R.; Musuc, A.M.; Ozon, E.A.; Anastasescu, M.; Atkinson, I.; Mitran, R.-A.; Rusu, A.; Luță, E.-A.; Chițescu, C.L.; Gîrd, C.E. Physicochemical Investigations on Samples Composed of a Mixture of Plant Extracts and Biopolymers in the Broad Context of Further Pharmaceutical Development. Polymers (Basel) 2025, 17, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.-J.; Yen, C.-H.; Kuo, M.-S. Determination of Trace Amounts of Arsenic(III) and Arsenic(V) in Drinking Water and Arsenic(III) Vapor in Air by Graphite-Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry Using 2,3-Dimercaptopropane-1-Sulfonate as a Complexing Agent. Analytical Sciences 1999, 15, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, D. Direct Graphite Furnace–Atomic Absorption Method for Determination of Lead in Edible Oils and Fats: Summary of Collaborative Study. J AOAC Int 1994, 77, 951–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.P.; Chen, S.L.; Liu, E.Q.; Chen, H.Y. Determination of Trace Elements in Some Seasonings by Microwave Digestion-High Resolution Continuum Source Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry. Modern Food Science and Technology 2013, 29, 1424–1427. [Google Scholar]

- Gunduz, S.; Akman, S. Investigation of Trace Element Contents in Edible Oils Sold in Turkey Using Microemulsion and Emulsion Procedures by Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry. LWT - Food Science and Technology 2015, 64, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, A.R.; Ozon, E.A.; Musuc, A.M.; Anastasescu, M.; Atkinson, I.; Mitran, R.-A.; Rusu, A.; Popescu, L.; Gîrd, C.E. Preparation and Preliminary Analysis of Several Nanoformulations Based on Plant Extracts and Biodegradable Polymers as a Possible Application for Chronic Venous Disease Therapy. Polymers (Basel) 2024, 16, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neagu, R.; Popovici, V.; Ionescu, L.E.; Ordeanu, V.; Popescu, D.M.; Ozon, E.A.; Gîrd, C.E. Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Effects of Different Samples of Five Commercially Available Essential Oils. 2023, 12, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaak, J.; Staib, P. An Updated Review on Efficacy and Benefits of Sweet Almond, Evening Primrose and Jojoba Oils in Skin Care Applications. Int J Cosmet Sci 2022, 44, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierrotte, O.; Gierasimovič, Z. The Effect Of Vitamins A, E, C On Skin Affected By Biological Age. Slauga. Mokslas ir praktika 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanawiwatpong, P.; Wanitphakdeedecha, R.; Bumrungpert, A.; Maiprasert, M. Anti-aging and Brightening Effects of a Topical Treatment Containing Vitamin C, Vitamin E, and Raspberry Leaf Cell Culture Extract: A Split-face, Randomized Controlled Trial. J Cosmet Dermatol 2020, 19, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.; Hiremath, P.; John, J.; Ranadive, N.; Nandakumar, K.; Mudgal, J. Modulatory Role of Vitamins A, B3, C, D, and E on Skin Health, Immunity, Microbiome, and Diseases. Pharmacological Reports 2023, 75, 1096–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochulska, O.M.; Chornomydz, I.B.; Hlushko, K.T.; Krycky, I.O.; Hoshchynskyi, P.V.; Dzhyvak, V.H. Clinical Effect of Applying Peach Oil with Vitamins A, E, D Externally on the Skin at Atopic Dermatitis in Children. Modern pediatrics. Ukraine 2023, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazali, N.I.; Mohd Rais, R.Z.; Makpol, S.; Chin, K.Y.; Yap, W.N.; Goon, J.A. Effects of Tocotrienol on Aging Skin: A Systematic Review. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaee, Z.M.; Al-Ani, I.; Hajleh, M.N.A.; Al-Dujaili, E. Formulation and Evaluation of Retinyl Palmitate and Vitamin E Nanoemulsion for Skin Care. Pharmacia 2023, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadee, P.; Chansakaow, S.; Tipduangta, P.; Tadee, P.; Khaodang, P.; Chukiatsiri, K. Essential Oil Pharmaceuticals for Killing Ectoparasites on Dogs. J Vet Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.J.; Harding, L.M.; Baranowski, A.P. A Novel Treatment of Postherpetic Neuralgia Using Peppermint Oil. Clin J Pain 2002, 18, 200–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, X.; Liu, T.; Ma, H.; Tian, Y.; Li, L.; Li, Z.; Gao, M.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Z. Preparation of Essential Oil-Based Microemulsions for Improving the Solubility, PH Stability, Photostability, and Skin Permeation of Quercetin. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 3097–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erawati, T.; Arifiani, R.A.; Miatmoko, A.; Hariyadi, D.M.; Rosita, N.; Purwanti, T. The Effect of Peppermint Oil Addition on the Physical Stability, Irritability, and Penetration of Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Coenzyme Q10. J Public Health Afr 2023, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narda, M.; Trullas, C.; Brown, A.; Piquero-Casals, J.; Granger, C.; Fabbrocini, G. Glycolic Acid Adjusted to PH 4 Stimulates Collagen Production and Epidermal Renewal without Affecting Levels of Proinflammatory TNF-alpha in Human Skin Explants. J Cosmet Dermatol 2021, 20, 513–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringer, K.L.; Davis, E.M.; Croteau, R. Monoterpene Metabolism. Cloning, Expression, and Characterization of (−)-Isopiperitenol/(−)-Carveol Dehydrogenase of Peppermint and Spearmint. Plant Physiol 2005, 137, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Estepa, R.; Turner, G.W.; Lee, J.M.; Croteau, R.B.; Lange, B.M. A Systems Biology Approach Identifies the Biochemical Mechanisms Regulating Monoterpenoid Essential Oil Composition in Peppermint. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 2818–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhadi, M.; Badi, H.N.; Mehrafarin, A.; Omidi, H. Allometric Ratio of Menthol and Menthone to Pulegone in the Essential Oil of Peppermint ( Mentha Piperita L.) Affected by Bioregulators. Research Journal Pharmacognosy 2018, 5, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaggaf, H.; El Hachlafi, N.; Elbouzidi, A.; Taibi, M.; Benkhaira, N.; El Kamari, F.; Alnasseri, S.M.; Laaboudi, W.; Bouyahya, A.; Ardianto, C.; et al. Unlocking the Combined Action of Mentha Pulegium L. Essential Oil and Thym Honey: In Vitro Pharmacological Activities, Molecular Docking, and in Vivo Anti-Inflammatory Effect. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabba, S. V.; Jordt, S.-E. Risk Analysis for the Carcinogen Pulegone in Mint- and Menthol-Flavored e-Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco Products. JAMA Intern Med 2019, 179, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Koh, H.-L.; Gao, Y.; Gong, Z.; Lee, E.J.D. Herbal Bioactivation: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Life Sci 2004, 74, 935–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO, 1995 GENERAL STANDARD FOR CONTAMINANTS AND TOXINS IN FOOD AND FEED (CODEX STAN 193-1995) Adopted in 1995 Revised in 1997, 2006, 2008, 2009 Amended in 2010, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015. GENERAL STANDARD FOR CONTAMINANTS AND TOXINS IN FOOD AND FEED (CODEX STAN 193-1995) 2015, 1.

- Assubaie, F.N. Assessment of the Levels of Some Heavy Metals in Water in Alahsa Oasis Farms, Saudi Arabia, with Analysis by Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2015, 8, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Fan, W.; Wang, X.; Qu, L.; Yao, S. Health Risk Assessment of Eight Heavy Metals in Nine Varieties of Edible Vegetable Oils Consumed in China. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2011, 49, 3081–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Regulation (EC) Commission Regulation (EC) No 118/2006 of 19 December 2006 Setting Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Union 2006, 364, 5–24.

- Păduraru, D.N.; Coman, F.; Ozon, E.A.; Gherghiceanu, F.; Andronic, O.; Ion, D.; Stănescu, M.; Bolocan, A. The Use of Nutritional Supplement in Romanian Patients – Attitudes and Beliefs. Farmacia 2019, 67, 1060–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeb, J.; Movassaghghazani, M. Assessment of Lead and Cadmium Exposure through Olive and Corn Oil Consumption in Gonbad-Kavus, North of Iran: A Public Health Risk Analysis. Toxicol Rep 2025, 14, 101922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräbner, D.; Hoffmann, H. Rheology of Cosmetic Formulations. In Cosmetic Science and Technology; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 471–488. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Jeong, E.H.; Baik, J.H.; Park, J.D. The Role of Rheology in Cosmetics Research: A Review. Korea-Australia Rheology Journal 2024, 36, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahasrabudhe, S.N.; Rodriguez-Martinez, V.; O’Meara, M.; Farkas, B.E. Density, Viscosity, and Surface Tension of Five Vegetable Oils at Elevated Temperatures: Measurement and Modeling. Int J Food Prop 2017, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyin, S.O.; Arinina, M.P.; Polyakova, M.Yu.; Kulichikhin, V.G.; Malkin, A.Ya. Rheological Comparison of Light and Heavy Crude Oils. Fuel 2016, 186, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobi, R.; Ravichandiran, P.; Babu, R.S.; Yoo, D.J. Biopolymer and Synthetic Polymer-Based Nanocomposites in Wound Dressing Applications: A Review. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppin, E.A.; Pike, O.A. Oil Stability Index Correlated with Sensory Determination of Oxidative Stability in Light-exposed Soybean Oil. J Am Oil Chem Soc 2001, 78, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabni, A.; Bañares, C.; Torres, C.F. Study of the Oxidative Stability via Oxitest and Rancimat of Phenolic-Rich Olive Oils Obtained by a Sequential Process of Dehydration, Expeller and Supercritical CO2 Extractions. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1494091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, C.-H.; Chang, C.-W.; Ho, Y.-C.; Chuang, Y.-K.; Lee, W.-J. Application of OXITEST for Prediction of Shelf-Lives of Selected Cold-Pressed Oils. Front Nutr 2021, 8, 763524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, U.; Devaraj, S.; Jialal, I. VITAMIN E, OXIDATIVE STRESS, AND INFLAMMATION. Annu Rev Nutr 2005, 25, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).