1. Introduction

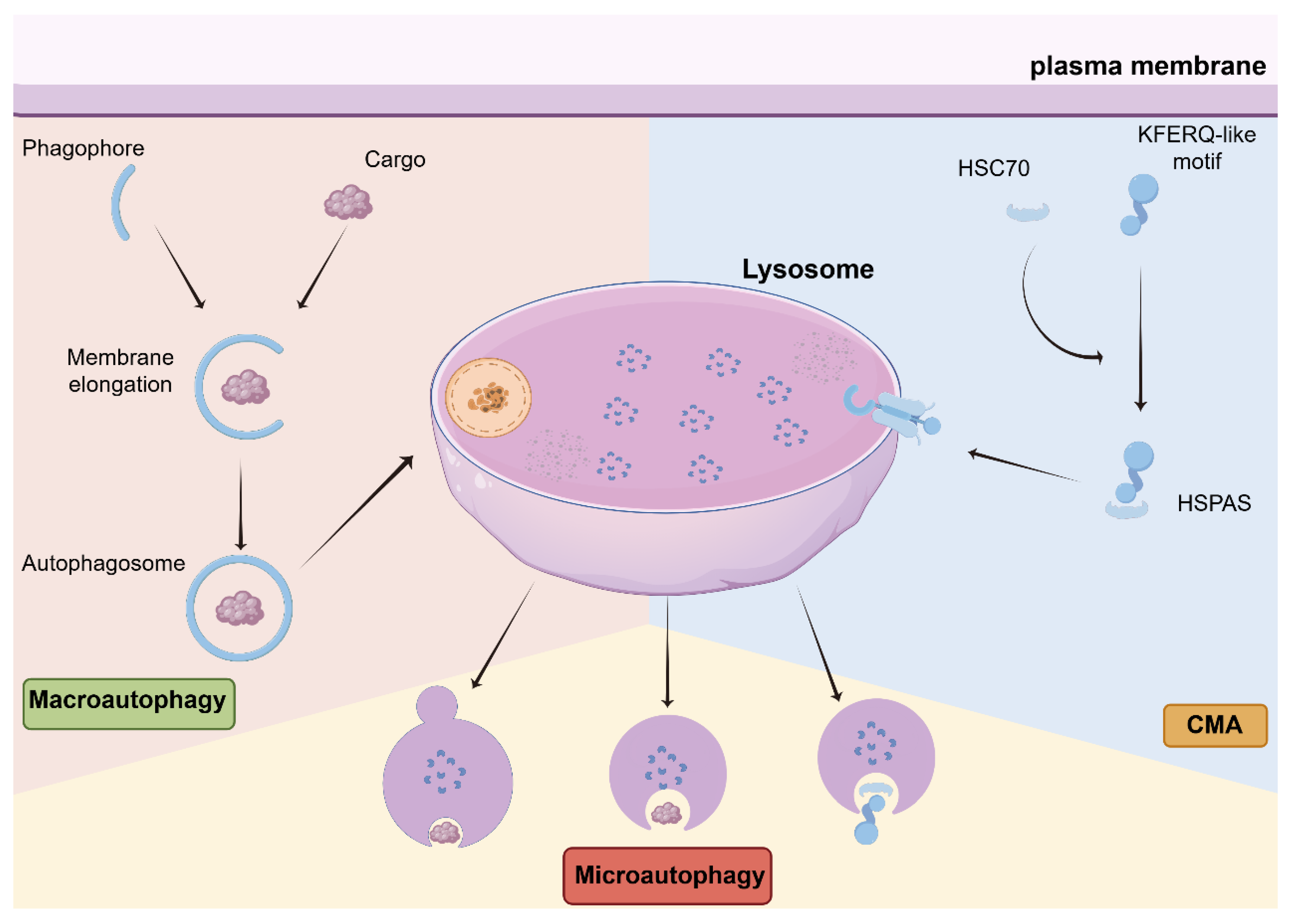

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved intracellular degradation system that plays a fundamental role in maintaining cellular homeostasis. Since its initial characterization more than half a century ago, autophagy has been recognized as a highly coordinated and multi-layered process encompassing distinct forms, including macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) (

Figure 1), each governed by specialized molecular machinery and regulatory networks [

1,

2]. This molecular complexity underlies the broad physiological relevance of autophagy in development, metabolism, and disease.

In cancer, autophagy has long been viewed as a paradoxical process. Early genetic and functional studies established a tumor-suppressive role for basal autophagy through the maintenance of genomic stability, proteostasis, and cellular quality control [

3,

4]. In contrast, subsequent work demonstrated that established tumors frequently exploit autophagy as an adaptive mechanism to survive metabolic stress, hypoxia, and therapeutic insults [

5,

6]. As a result, both autophagy activation and inhibition have been reported to produce beneficial or detrimental effects depending on experimental context, leading to inconsistent outcomes in preclinical models and clinical trials [

7,

8,

9].

A central explanation for these discrepancies lies in the stage- and context-dependent nature of autophagy in cancer. Autophagic activity is dynamically regulated throughout tumor evolution and varies substantially among genetically and metabolically heterogeneous cancer cell populations [

10]. Moreover, autophagy is not confined to malignant cells. Immune cells, endothelial cells, and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) within the tumor microenvironment (TME) exhibit distinct autophagy programs that critically influence tumor growth, immune surveillance, and therapeutic resistance [

11,

12,

13]. Consequently, autophagy-targeted interventions inevitably affect multiple cellular compartments, with therapeutic outcomes determined by the integrated response of the tumor ecosystem rather than cancer cells alone.

The TME imposes additional selective pressures that actively rewire autophagy pathways. Hypoxia and nutrient deprivation robustly induce autophagy in both tumor and immune cells, reshaping immune responses and treatment sensitivity [

11,

12]. Notably, recent studies have demonstrated that autophagy-mediated degradation of major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecules facilitates tumor immune evasion, whereas autophagy inhibition can restore antigen presentation and enhance immunotherapy efficacy [

14]. These findings underscore the critical importance of microenvironmental context in determining whether autophagy restrains or promotes tumor progression.

Precision medicine provides a conceptual framework for addressing the context dependency of autophagy by integrating molecular profiling, tumor staging, and microenvironmental features to guide therapeutic decision-making [

15,

16]. Within this framework, nanotechnology-based drug delivery systems offer unique advantages for spatially and temporally controlled modulation of autophagy. Nanocarriers can enhance tumor-specific drug accumulation, enable cell-type-selective targeting, and fine-tune autophagic responses while minimizing systemic toxicity [

17]. Emerging nanomedicine strategies have demonstrated the feasibility of modulating autophagy-related pathways—including Beclin-1, mTOR, and p53 signaling—in a context-aware manner [

18,

19,

20].

In this review, we propose that autophagy-related proteins should be redefined as context-dependent therapeutic targets rather than universal intervention points. By synthesizing current evidence on the stage- and microenvironment-specific roles of key autophagy regulators and discussing how precision nanomedicine enables spatiotemporal control of autophagy within heterogeneous tumors, we aim to provide a rational framework for exploiting autophagy in personalized cancer therapy.

2. Autophagy as a Stage- and Context-Dependent Process in Cancer

Autophagy functions as a dynamic and adaptive process throughout tumor development, exerting distinct and sometimes opposing roles at different stages of cancer progression. During early tumorigenesis, basal autophagy contributes to tumor suppression by maintaining cellular homeostasis, limiting oxidative stress, and preventing the accumulation of damaged organelles and oncogenic protein aggregates. Genetic or functional disruption of core autophagy machinery has been shown to promote genomic instability and malignant transformation, supporting the protective role of autophagy during the initial phases of tumor development.

As tumors progress, however, cancer cells are increasingly exposed to hostile microenvironmental conditions characterized by hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, and therapeutic stress. Under these circumstances, autophagy is frequently co-opted as an adaptive survival mechanism that supports metabolic flexibility and stress tolerance. This transition gives rise to a state often described as “autophagy addiction,” in which advanced tumors rely on sustained autophagic flux to cope with bioenergetic and proteotoxic stress. In this setting, autophagy inhibition can sensitize tumors to chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or targeted therapies, although therapeutic efficacy remains highly context dependent [

7,

21,

22].

Intratumoral heterogeneity further complicates efforts to therapeutically target autophagy. Cancer cell subpopulations within the same tumor differ substantially in genetic alterations, metabolic requirements, and stress adaptability, resulting in variable dependence on autophagy. Consequently, global modulation of autophagy may eliminate vulnerable cell populations while inadvertently selecting for more aggressive and therapy-resistant clones. Moreover, autophagy can either promote survival or trigger non-apoptotic cell death depending on the genetic and signaling context, underscoring the limitations of uniform therapeutic strategies [

23].

Importantly, autophagy is not restricted to malignant cells but operates across multiple cellular compartments within the tumor microenvironment. In immune cells, autophagy regulates antigen presentation, cytokine secretion, and cell viability, thereby shaping anti-tumor immunity. In stromal cells, particularly cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), autophagy supports metabolic coupling with cancer cells and facilitates tumor recovery following therapeutic stress, including radiotherapy [

24,

25]. These non-cell-autonomous effects highlight that the net impact of autophagy modulation reflects the integrated response of the tumor ecosystem rather than cancer cells alone.

Taken together, these observations emphasize that autophagy in cancer should be viewed as a stage-dependent and context-specific process rather than a static pathway. Effective therapeutic exploitation of autophagy therefore requires precise consideration of tumor stage, cellular heterogeneity, and microenvironmental conditions, providing a strong rationale for integrating autophagy-targeted interventions with precision medicine strategies.

3. Context-Dependent Roles of Key Autophagy Regulators in Cancer

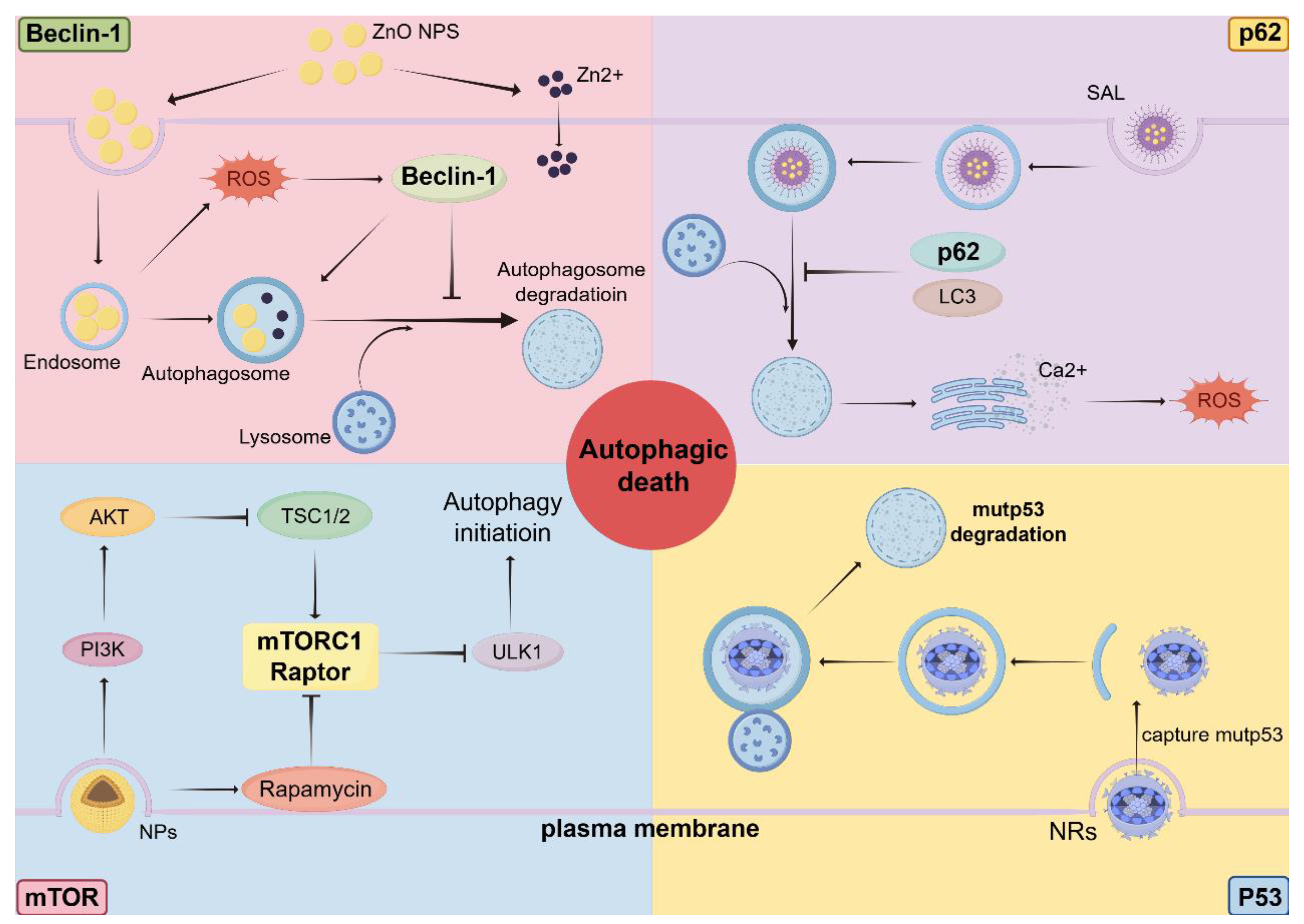

Autophagy-related proteins are often discussed as discrete molecular targets; however, accumulating evidence indicates that their biological functions and therapeutic relevance are profoundly shaped by tumor stage, genetic background, and microenvironmental context. Central regulators such as Beclin-1, p62/SQSTM1, mTOR, and p53 occupy nodal positions at the intersection of autophagy, metabolism, stress responses, and cell fate determination. Rather than functioning as linear components of a uniform pathway, these proteins act as context-sensitive signaling hubs whose modulation can yield divergent therapeutic outcomes (

Figure 2).

3.1. Beclin-1: Tumor Suppressor, Stress Adaptor, or Therapeutic Switch

Beclin-1, encoded by

BECN1, was among the first autophagy-related proteins implicated in cancer and is frequently described as a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor [

26]. Early studies demonstrated that reduced

BECN1 expression promotes tumor initiation, supporting the concept that basal autophagy restrains malignant transformation by preserving cellular homeostasis [

27]. These findings positioned Beclin-1 as a canonical tumor-suppressive regulator during early-stage tumorigenesis.

Subsequent work, however, revealed a more nuanced and context-dependent role for Beclin-1 in established tumors. Beclin-1 participates in multiple protein complexes that integrate signals from nutrient availability, growth factor signaling, and cellular stress, thereby fine-tuning autophagic flux [

28]. In metabolically stressed or hypoxic tumor environments, Beclin-1–dependent autophagy enables cancer cells to maintain bioenergetic balance and limit proteotoxic damage, effectively functioning as a stress-adaptive mechanism that supports tumor progression and therapy resistance [

3,

10].

Recent nanomedicine-based studies further illustrate the therapeutic ambiguity of targeting Beclin-1. Nanoparticle-mediated modulation of Beclin-1 signaling has been reported to induce autophagic cell death or suppress tumor growth in a cancer type– and context-dependent manner [

29,

30,

31]. Conversely, targeted suppression of

BECN1 using a peptide-conjugated poly (β-amino ester) can inhibit autophagy and restrain tumor progression in autophagy-dependent models [

32]. Collectively, these findings underscore that Beclin-1 cannot be uniformly classified as either a beneficial or detrimental therapeutic target; instead, its relevance depends critically on the timing, location, and mode of autophagy modulation.

3.2. p62/SQSTM1: Autophagy Flux Sensor and Oncogenic Signaling Hub

p62/SQSTM1 occupies a unique position at the interface between selective autophagy and oncogenic signaling. As an autophagy receptor, p62 mediates the delivery of ubiquitinated cargo to autophagosomes, while its own degradation serves as a functional indicator of autophagic flux [

33]. Accumulation of p62 is commonly observed in autophagy-deficient settings and has been linked to tumor-promoting signaling through activation of NRF2, NF-κB, and mTOR pathways [

34].

Paradoxically, p62 also cooperates with intact autophagy to promote tumor progression. Rather than acting solely as a passive substrate, p62 functions as a signaling scaffold that integrates stress responses, metabolic reprogramming, and survival pathways. In tumors with functional autophagic flux, dynamic turnover of p62 supports adaptation to oxidative and metabolic stress, whereas disruption of this balance can shift p62 toward a driver of oncogenic signaling.

These dual roles complicate therapeutic strategies targeting p62. Autophagy inhibition may lead to pathological accumulation of p62, inadvertently enhancing tumor-promoting pathways. Conversely, restoring autophagic degradation of p62 can suppress oncogenic signaling in selected contexts [

35]. Thus, p62 exemplifies a key principle in autophagy-targeted therapy: therapeutic outcome is determined by modulation of autophagic flux rather than static alteration of individual pathway components.

3.3. mTOR: Metabolic Gatekeeper Linking Autophagy and Therapeutic Vulnerability

mTOR serves as a master regulator of cellular metabolism and a central inhibitory node controlling autophagy initiation [

36]. Hyperactivation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis is a hallmark of many cancers and contributes to uncontrolled proliferation, metabolic rewiring, and therapeutic resistance [

37]. Accordingly, pharmacological inhibition of mTOR has been widely explored as a strategy to induce autophagy and suppress tumor growth.

Despite its conceptual appeal, mTOR inhibition produces heterogeneous outcomes across tumor types and treatment contexts. In some settings, mTOR inhibition–induced autophagy promotes cancer cell survival by alleviating metabolic stress and limiting therapy-induced damage. In others, excessive or dysregulated autophagy can trigger non-apoptotic cell death or sensitize tumors to chemotherapy and radiotherapy [

38]. These divergent responses reflect differences in tumor stage, metabolic dependency, and co-occurring genetic alterations.

Nanoparticle-based delivery systems provide new opportunities to refine mTOR-targeted autophagy modulation. Nanocarriers encapsulating mTOR inhibitors or autophagy modulators enable controlled drug release, enhanced tumor accumulation, and reduced systemic toxicity [

39,

40]. Importantly, precision delivery allows selective exploitation of autophagy dependency in advanced tumors while limiting protective autophagy in normal tissues, reinforcing the concept that mTOR represents a context-sensitive therapeutic node rather than a universal autophagy switch.

3.4. p53: Genotype-Dependent Regulator of Autophagy and Therapy Response

p53 plays a multifaceted role in autophagy regulation, acting as either an inducer or suppressor depending on its mutation status, subcellular localization, and signaling context [

41]. Wild-type p53 can promote autophagy through transcriptional activation of autophagy-related genes and metabolic stress pathways, contributing to tumor suppression during early disease stages. In contrast, cytoplasmic p53 has been reported to inhibit autophagy, further highlighting the complexity of p53-mediated regulation.

In p53-deficient or mutant tumors, autophagy regulation is frequently rewired, altering therapeutic vulnerabilities. Mutant p53 can cooperate with autophagy to promote tumor survival and chemoresistance, whereas restoration of wild-type p53 activity may sensitize tumors to autophagy modulation [

42]. Recent nanomedicine-based approaches have leveraged this dependency by delivering wild-type p53 or promoting selective degradation of mutant p53 via autophagy-related mechanisms, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy [

43,

44].

These findings illustrate that p53 status is a critical determinant of whether autophagy activation or inhibition is therapeutically advantageous. As such, p53 exemplifies the importance of genotype-informed strategies when integrating autophagy modulation with precision delivery platforms.

3.5. Implications for Precision Autophagy Targeting

Collectively, these examples demonstrate that key autophagy regulators function as context-dependent signaling hubs rather than linear drug targets. The therapeutic impact of modulating Beclin-1, p62, mTOR, or p53 is dictated by tumor stage, genetic background, metabolic state, and microenvironmental pressures. Failure to account for these variables helps explain the inconsistent outcomes observed in clinical attempts to target autophagy.

Precision medicine approaches—particularly when combined with nanotechnology-enabled delivery systems—offer a viable path forward by enabling spatially and temporally controlled modulation of autophagy in defined cellular contexts. A clear understanding of the context-dependent biology of autophagy regulators is therefore essential for transforming autophagy from a paradoxical pathway into a rational and actionable therapeutic opportunity.

4. Tumor Microenvironment as a Determinant of Autophagy Dependency

Autophagy in cancer cannot be fully understood without considering the tumor microenvironment (TME), which imposes dynamic and heterogeneous stresses that profoundly shape autophagy dependency and therapeutic vulnerability. The TME comprises a complex and evolving network of malignant cells, immune infiltrates, stromal components, vasculature, and extracellular matrix, all of which experience fluctuating oxygen and nutrient availability as well as immune and therapeutic pressures [

45,

46,

47]. These microenvironmental conditions act as powerful regulators of autophagy, rendering its functional consequences highly context specific.

4.1. Hypoxia and Metabolic Stress as Drivers of Autophagy Rewiring

Hypoxia and nutrient deprivation are defining features of solid tumors and among the most potent inducers of autophagy. Oxygen limitation activates autophagy through multiple mechanisms, including suppression of mTOR signaling and engagement of stress-responsive pathways, enabling tumor cells to maintain energy homeostasis under adverse conditions [

48]. Autophagy-mediated recycling of intracellular components supports metabolic flexibility and promotes survival in poorly vascularized tumor regions.

Beyond cancer cells, hypoxia-driven autophagy also exerts important effects on immune cell function within the TME. In immune populations exposed to low oxygen tension, autophagy modulates cytokine production, antigen processing, and cell survival, thereby reshaping anti-tumor immune responses [

11]. These observations highlight the dual role of hypoxia-induced autophagy: while facilitating tumor cell adaptation, it simultaneously influences immune surveillance in a context-dependent manner.

4.2. Autophagy-Mediated Immune Evasion and Immunotherapy Response

Recent studies have uncovered a direct mechanistic link between autophagy and tumor immune evasion. Autophagy can selectively degrade components of the antigen presentation machinery, most notably major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) molecules, thereby reducing tumor recognition by cytotoxic T lymphocytes [

14]. This mechanism has been particularly well characterized in pancreatic cancer, where autophagy-mediated MHC-I degradation contributes to immune escape and resistance to immunotherapy.

Conversely, inhibition of autophagy has been shown to restore surface expression of MHC-I molecules, enhance antigen presentation, and improve the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade in selected tumor models [

49]. These findings underscore that autophagy modulation can reprogram tumor–immune interactions, but only within specific immunological and microenvironmental contexts. Autophagy should therefore be viewed not merely as a cell-autonomous survival pathway but also as a regulator of tumor immunogenicity.

4.3. Autophagy in Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts and Stromal Support

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) constitute a major stromal component of the TME and play a central role in tumor progression and therapy resistance. Emerging evidence indicates that CAFs exhibit elevated autophagic activity, which supports metabolic coupling between stromal and cancer cells [

50]. Through autophagy-dependent recycling processes, CAFs supply metabolites and growth-supportive factors that fuel tumor growth and facilitate recovery following therapeutic stress.

Autophagy in CAFs has been particularly implicated in resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Experimental models demonstrate that autophagy-competent CAFs promote the survival and regrowth of irradiated cancer cells, whereas disruption of stromal autophagy sensitizes tumors to treatment. These findings reveal a non-cell-autonomous dimension of autophagy dependency and suggest that targeting autophagy exclusively in malignant cells may be insufficient to overcome therapy resistance.

4.4. Therapeutic Stress, Adaptive Autophagy, and Resistance Mechanisms

Therapeutic interventions themselves represent a major selective pressure within the TME and frequently induce adaptive autophagy as a cytoprotective response. Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapies can activate autophagy through mechanisms involving DNA damage, oxidative stress, and metabolic disruption [

51,

52]. While such stress-induced autophagy may initially limit tumor growth, it often contributes to the emergence of treatment resistance by enabling cancer cells to withstand cytotoxic insults.

Importantly, the contribution of autophagy to therapy resistance is strongly influenced by microenvironmental factors. Hypoxic tumor regions, for example, often display heightened autophagy dependency following treatment, whereas well-oxygenated areas may respond differently. This spatial heterogeneity further complicates uniform therapeutic strategies and underscores the need for context-aware modulation of autophagy.

4.5. Targeting TME-Driven Autophagy: Implications for Precision Therapy

Collectively, these findings establish the TME as a decisive determinant of autophagy dependency in cancer. Hypoxia, immune interactions, stromal support, and therapy-induced stress converge to reprogram autophagy across multiple cellular compartments, dictating whether autophagy restrains tumor growth or promotes tumor persistence. Therapeutic strategies that fail to account for this microenvironmental complexity are therefore unlikely to achieve durable clinical benefit.

Precision medicine approaches that integrate tumor stage, immune profiling, and microenvironmental characteristics provide a rational framework for exploiting TME-driven autophagy vulnerabilities [

53]. In this context, nanotechnology-based delivery systems offer a powerful means to selectively modulate autophagy within specific regions or cell types of the TME, thereby enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects [

54]. Understanding and targeting TME-driven autophagy thus represents a critical step toward the rational design of personalized, autophagy-informed cancer therapies.

5. Precision Nanomedicine for Spatiotemporal Modulation of Autophagy

The context-dependent nature of autophagy presents a fundamental obstacle to therapeutic intervention, as indiscriminate activation or inhibition of autophagy often produces unpredictable and even opposing effects. Precision nanomedicine offers a compelling strategy to address this challenge by enabling spatially and temporally controlled modulation of autophagy, improving tumor specificity, and minimizing systemic toxicity [

55,

56,

57]. By integrating targeted delivery, controlled release, and microenvironment-responsive design, nanotechnology provides a practical framework for translating autophagy biology into personalized cancer therapy (

Table 1).

5.1. Rationale for Nanotechnology-Based Autophagy Modulation

Conventional pharmacological modulators of autophagy, including mTOR inhibitors and lysosomal inhibitors, exert systemic effects that fail to account for intratumoral heterogeneity and microenvironmental complexity. Such approaches inevitably influence autophagy in both malignant and non-malignant tissues, including immune and stromal compartments, thereby limiting therapeutic selectivity and tolerability.

Nanocarrier-based delivery systems overcome these limitations by enhancing tumor accumulation through passive and active targeting mechanisms, enabling controlled drug release, and facilitating cell-type-selective modulation of autophagy [

60,

61]. These properties are particularly advantageous for autophagy-targeted therapies, where therapeutic efficacy depends on precise modulation of autophagic flux in defined cellular contexts rather than global pathway inhibition.

5.2. Targeted Nanocarriers for Modulating Beclin-1–Dependent Autophagy

A growing body of evidence demonstrates that nanomedicine-based approaches can effectively modulate Beclin-1–dependent autophagy in cancer. Liposomal and polymeric nanoparticles loaded with autophagy-modulating agents have been shown to induce Beclin-1–associated autophagic responses, leading to tumor growth inhibition or autophagic cell death in selected tumor models. In lung and ovarian cancer systems, nanoparticle formulations that enhance Beclin-1–mediated autophagy have been reported to exert anti-tumor effects through excessive stress induction or non-apoptotic cell death pathways [

29,

30].

Conversely, nanocarriers delivering microRNAs or small interfering RNAs targeting BECN1 have been used to suppress autophagy in autophagy-dependent tumors, resulting in reduced tumor progression and enhanced treatment sensitivity [

62]. These contrasting strategies reinforce a central concept of this review: Beclin-1 functions as a context-dependent therapeutic switch, and nanotechnology enables its bidirectional modulation in a tumor- and stage-specific manner.

5.3. Nanomedicine-Enabled Control of mTOR Signaling and Autophagy Flux

Given its central role in autophagy regulation, mTOR has been extensively explored as a therapeutic target in cancer. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of mTOR inhibitors has been shown to improve drug stability, pharmacokinetics, and tumor accumulation compared with free agents. Polymeric nanoparticles and albumin-bound formulations encapsulating sirolimus or related compounds exemplify this strategy and have demonstrated enhanced anti-tumor efficacy in preclinical and clinical settings [

63].

Beyond improving drug delivery, advanced nanocarriers have been engineered to fine-tune autophagy flux by modulating upstream signaling pathways and lysosomal function [

64]. Such systems enable controlled induction or inhibition of autophagy depending on tumor dependency and treatment context. Importantly, nanomedicine-based mTOR modulation can be integrated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or immunotherapy to exploit autophagy-mediated vulnerabilities while limiting adaptive resistance.

5.4. Nanoparticle-Based Strategies Targeting p53–Autophagy Interplay

The interplay between p53 status and autophagy regulation offers unique opportunities for precision nanomedicine. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of wild-type p53 has been shown to sensitize p53-deficient tumors to chemotherapy and targeted therapies, in part through modulation of autophagy-related signaling pathways [

20]. These approaches illustrate how restoration of tumor suppressor function can be coupled with reprogramming of autophagy dependency.

More recently, innovative nanoreceptor systems have been developed to promote selective degradation of mutant p53 by mimicking autophagy receptors, thereby reactivating autophagy-mediated tumor suppression [

43]. Such strategies demonstrate the potential of nanotechnology to manipulate autophagy at the level of specific protein–protein interactions rather than through indiscriminate pathway inhibition.

5.5. Responsive and Multifunctional Nanocarriers for TME-Adapted Autophagy Modulation

The tumor microenvironment provides distinct physicochemical cues—including acidic pH, hypoxia, and elevated reactive oxygen species—that can be exploited for responsive nanomedicine design. Multifunctional nanocarriers capable of sensing and responding to these cues enable localized modulation of autophagy within specific tumor regions.

Recent studies have shown that ultrasmall nanoparticles and metal-based nanomaterials can induce or disrupt autophagy by interfering with autophagosome formation, maturation, or lysosomal function [

65]. In parallel, hybrid nanovesicle systems have been developed to modulate autophagy within the TME to enhance anti-tumor immunity, highlighting the potential of combining autophagy regulation with immunomodulatory strategies. These advances underscore that nanotechnology can function not only as a delivery vehicle but also as an active regulator of autophagy dynamics.

5.6. Challenges and Perspectives for Clinical Translation

Despite encouraging preclinical progress, several challenges hinder the clinical translation of nanomedicine-based autophagy modulation. These include variability in nanoparticle biodistribution, incomplete understanding of long-term effects on autophagy in non-malignant tissues, and the lack of robust biomarkers to monitor autophagy flux in patients. Moreover, the complexity of autophagy regulation within the TME necessitates careful patient stratification and treatment customization

Nonetheless, the convergence of precision medicine, nanotechnology, and autophagy biology offers a compelling opportunity to overcome the longstanding paradox of autophagy targeting in cancer. By enabling spatially and cell-type-selective modulation of autophagy, precision nanomedicine provides a rational pathway toward more effective and personalized cancer therapies.

6. Integrating Autophagy Targeting with Tumor Microenvironment Modulation and Combination Therapy

Given the multifaceted and context-dependent roles of autophagy in cancer, it has become increasingly evident that autophagy modulation is unlikely to be effective as a standalone therapeutic strategy. Instead, its greatest therapeutic value lies in rational integration with tumor microenvironment (TME) modulation and established treatment modalities, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Such combination approaches aim to exploit autophagy-dependent vulnerabilities while limiting adaptive resistance and preserving anti-tumor immunity.

6.1. Autophagy Modulation to Overcome Therapy Resistance

Adaptive autophagy represents a well-established mechanism of resistance to chemotherapy and targeted therapies. A wide range of cytotoxic agents and molecularly targeted drugs induce autophagy as a cellular stress response, enabling cancer cells to survive treatment-induced damage and metabolic disruption. Inhibition of autophagy has therefore been shown to sensitize tumor cells to chemotherapeutic agents, histone deacetylase inhibitors, and targeted therapies, particularly in tumors that exhibit high autophagy dependency.

However, the therapeutic benefit of autophagy inhibition is strongly influenced by tumor stage and microenvironmental context. In advanced tumors characterized by hypoxia and nutrient limitation, autophagy inhibition may preferentially target highly stress-adapted cancer cell populations. In contrast, in early-stage or metabolically less constrained tumors, autophagy inhibition may provide limited benefit or even compromise cellular homeostasis. These observations underscore the necessity of precise patient selection and optimal treatment timing when combining autophagy modulation with conventional anti-cancer therapies.

6.2. Enhancing Radiotherapy Efficacy Through Stromal and Microenvironmental Autophagy Targeting

Radiotherapy imposes profound stress on both malignant and stromal compartments of the tumor microenvironment, leading to robust induction of autophagy. Notably, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) have emerged as critical mediators of tumor regrowth following radiation through autophagy-dependent mechanisms. Autophagy in CAFs supports metabolic recycling and paracrine signaling that facilitate the survival and recovery of irradiated cancer cells.

Targeting stromal autophagy therefore represents a promising strategy to enhance radiotherapy efficacy. Disruption of autophagy in CAFs has been shown to impair tumor repair processes and sensitize tumors to radiation-induced damage. Importantly, these findings highlight the non-cell-autonomous contributions of autophagy to treatment resistance and emphasize that effective autophagy-targeted strategies must extend beyond cancer cell–intrinsic pathways.

6.3. Autophagy and Immunotherapy: Balancing Immune Activation and Immune Evasion

The interplay between autophagy and anti-tumor immunity has emerged as a critical determinant of immunotherapy response. Autophagy regulates antigen presentation, immune cell survival, and cytokine production, thereby shaping the immunological landscape of the tumor microenvironment.

These findings suggest that autophagy inhibition may function as an immunotherapy sensitizer in selected tumor contexts. However, autophagy also supports immune cell viability and function under stress conditions, raising the concern that indiscriminate autophagy inhibition could impair anti-tumor immune responses. Consequently, spatially and temporally controlled modulation of autophagy—potentially achieved through precision nanomedicine—may be required to maximize immunotherapeutic efficacy while preserving immune competence.

6.4. Nanomedicine-Enabled Combination Strategies Targeting Autophagy and the TME

Nanotechnology provides a versatile platform for integrating autophagy modulation with TME-targeted combination therapies. Recent nanomedicine-based approaches have demonstrated the feasibility of co-delivering autophagy modulators with chemotherapeutic agents, immunomodulators, or metabolic inhibitors to achieve synergistic anti-tumor effects. By enabling localized drug release and cell-type-selective targeting, nanocarriers can reduce systemic toxicity and minimize off-target effects on immune and stromal compartments.

Moreover, multifunctional nanocarriers responsive to microenvironmental cues—such as hypoxia, acidic pH, or oxidative stress—offer the capacity to dynamically modulate autophagy in tumor regions with heightened dependency. These strategies align with the principles of precision medicine by tailoring therapeutic interventions to the spatial, metabolic, and immunological heterogeneity of individual tumors.

6.5. Clinical Considerations and Future Integration Strategies

Despite promising preclinical evidence, the clinical integration of autophagy-targeted combination therapies remains challenging. Key obstacles include the identification of reliable biomarkers to assess autophagy dependency, determination of optimal treatment sequencing, and management of potential toxicities associated with sustained autophagy modulation. In addition, patient-reported outcomes and quality-of-life considerations emphasize the importance of minimizing systemic side effects while maintaining therapeutic efficacy.

Future clinical strategies should prioritize rational trial design informed by tumor stage, molecular profiling, and microenvironmental characterization. Integration of pharmacodynamic biomarkers to monitor autophagy modulation, combined with precision delivery platforms, may enable adaptive treatment strategies that maximize therapeutic benefit while limiting resistance and toxicity.

7. Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite substantial progress in elucidating the molecular mechanisms and functional roles of autophagy in cancer, the clinical translation of autophagy-targeted therapies remains limited. This gap reflects not a lack of biological relevance, but rather the intrinsic complexity and context dependency of autophagy regulation. Addressing these challenges requires a conceptual shift from uniform pathway modulation toward context-aware, precision-guided therapeutic strategies.

7.1. Defining and Measuring Autophagy Dependency in Patients

One of the most significant barriers to effective autophagy-targeted therapy is the absence of robust biomarkers capable of defining autophagy dependency in human tumors. Autophagy is a highly dynamic and multistep process, and static measurements of autophagy-related proteins—such as LC3 or p62—often fail to capture functional autophagic flux. As a result, patient stratification based on conventional markers remains imprecise, contributing to variable clinical outcomes.

Future efforts should focus on the development of dynamic, context-sensitive biomarkers that integrate molecular signatures, metabolic states, and microenvironmental features. Advances in multi-omics profiling, functional imaging, and real-time assessment of autophagy activity may enable more accurate evaluation of autophagy dependency in clinical samples. Importantly, such approaches should extend beyond cancer cells to encompass autophagy activity within immune and stromal compartments of the tumor microenvironment.

7.2. Managing Spatial and Temporal Heterogeneity of Autophagy

Tumor heterogeneity represents a fundamental obstacle to effective autophagy targeting. Autophagy dependency varies across tumor regions, cellular subpopulations, and disease stages, driven by gradients in oxygen availability, nutrient supply, and therapeutic exposure. Consequently, uniform modulation of autophagy often produces incomplete or transient responses, with resistant subclones emerging over time.

Addressing this challenge necessitates therapeutic strategies capable of spatially and temporally controlled autophagy modulation. Nanomedicine-based delivery systems, particularly those responsive to microenvironmental cues such as hypoxia or acidity, offer a promising avenue for achieving localized and adaptive control of autophagy. However, realizing this potential will require deeper insights into intratumoral nanoparticle distribution and more precise control over release kinetics.

7.3. Balancing Anti-Tumor Efficacy with Immune Preservation

Autophagy plays indispensable roles in immune cell survival, antigen presentation, and cytokine regulation, raising important concerns regarding the immunological consequences of autophagy modulation.

Future therapeutic strategies must therefore carefully balance tumor-directed autophagy modulation with preservation of immune competence. This balance may be achieved through cell-type-selective targeting, optimized dosing schedules, or temporally restricted intervention windows. Precision delivery platforms, combined with immune profiling, will be essential for tailoring autophagy modulation strategies that synergize with immunotherapy rather than undermine it.

7.4. Translational and Clinical Trial Challenges

Clinical trials targeting autophagy have historically encountered challenges related to patient selection, treatment sequencing, and toxicity management. Many early studies relied on non-specific autophagy inhibitors and lacked pharmacodynamic biomarkers to confirm effective pathway modulation, limiting interpretability and clinical impact. Moreover, sustained manipulation of autophagy raises legitimate concerns regarding long-term toxicity, given the essential role of autophagy in normal tissue homeostasis.

Future clinical development should emphasize rational trial design grounded in precision oncology principles. This includes stratifying patients based on molecular and microenvironmental characteristics, incorporating biomarkers to monitor autophagy flux in real time, and optimizing combination regimens to minimize cumulative toxicity. In parallel, patient-reported outcomes and quality-of-life measures should be integrated into trial endpoints to ensure clinical relevance and tolerability.

7.5. Future Directions: Toward Context-Aware Autophagy Therapy

The future of autophagy-targeted cancer therapy lies in embracing, rather than attempting to simplify, the context-dependent nature of autophagy. Integrative strategies that combine autophagy biology, tumor microenvironment analysis, and precision delivery technologies hold promise for overcoming current limitations. In particular, nanomedicine-enabled approaches offer the ability to selectively modulate autophagy within defined spatial and cellular contexts, transforming autophagy from a blunt therapeutic target into a finely tunable regulatory axis.

Advances in systems biology, artificial intelligence–driven data integration, and real-time monitoring of therapeutic responses may further enhance the ability to predict autophagy dependency and guide personalized treatment strategies. Ultimately, translating these insights into clinical benefit will require close interdisciplinary collaboration among basic scientists, clinicians, and bioengineers, as well as adaptive therapeutic paradigms that evolve with tumor dynamics.

8. Conclusions

Autophagy is a central paradoxical process in cancer, exerting tumor-suppressive/promoting effects dependent on stage, genotype, and microenvironment. Uniform global modulation is ineffective; its clinical value lies in dynamic, context-dependent roles in tumor ecosystems. Key regulators (Beclin-1, p62/SQSTM1, mTOR, p53) integrate signals to govern tumor progression and therapy resistance; neglecting these interactions explains disappointing clinical outcomes. The tumor microenvironment (TME) emerges as a pivotal determinant of autophagy dependency, coordinating hypoxia-mediated metabolic adaptation, stromal support, immune modulation, and treatment-induced stress responses. Beyond facilitating tumor cell survival under adverse conditions, autophagy actively remodels tumor-immune and tumor-stroma crosstalk, highlighting the imperative of a systems-level perspective that frames autophagy as an ecosystem-wide adaptive program rather than a cancer cell-intrinsic pathway. Precision medicine offers a rational framework to dissect autophagy’s complexity in cancer by integrating tumor stage, molecular profiling, and TME features. Within this paradigm, precision nanomedicine provides robust tools for spatiotemporally controlled autophagy modulation, enabling cell-type-selective targeting while mitigating systemic toxicity and transforming autophagy intervention from a blunt strategy into a finely tunable therapeutic approach.

In conclusion, embracing autophagy’s context dependency constitutes a paradigm shift in cancer therapy. Aligning autophagy biology with TME dynamics and precision delivery technologies may enable future strategies to overcome long-standing challenges in autophagy targeting. Sustained interdisciplinary efforts are essential to translate these insights into clinically impactful, personalized cancer treatments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization M.W., M.L. and A.L.; original draft writing: Y.L., A.L. and M.W.; supervision: M.W.; figure and tables: M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Part of the present work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82403464).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

Not applicable.

References

- Yang, Z.; Klionsky, D.J. Eaten alive: a history of macroautophagy. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2019, 12, 814-822.

- Nakatogawa, H. Mechanisms governing autophagosome biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2020, 21, 439-458.

- Russell, R.C.; Guan, K.L. The multifaceted role of autophagy in cancer. EMBO. J. 2022, 41, e110031. [CrossRef]

- White, E. The role for autophagy in cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 12, 42-46.

- Debnath, J.; Gammoh, N.; Ryan, K.M. Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2023, 24, 560-575.

- Shi, Z.; Hu, C.L.; Zheng, X.G.; Sun, C.; Li, Q. Feedback loop between hypoxia and energy metabolic reprogramming aggravates the radioresistance of cancer cells. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2024, 13, 55. [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.M.; Thorburn, A. Targeting autophagy during cancer therapy to improve clinical outcomes. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 131, 130-141. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Hernández, M.; Arias, A.; Martínez-García, D.; Pérez-Tomás, R.; Quesada, R.; Soto-Cerrato, V. Targeting Autophagy for Cancer Treatment and Tumor Chemosensitization. Cancers. 2019, 11, 1599.

- Zou, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Long. Z.; Chen, J.; Tang, Z.; Zhu, Y.L.; Chen, S.P.; Xu, J.; Yan, M.; et al. Aurora kinase A inhibition-induced autophagy triggers drug resistance in breast cancer cells. Autophagy. 2012, 8, 1798-1810. [CrossRef]

- Kenific, C.M.; Debnath, J. Cellular and metabolic functions for autophagy in cancer cells. Trends. Cell. Biol. 2015, 25, 37-45.

- Schlie, K.; Spowart, J.E.; Hughson, L.R.; Townsend, K.N.; Lum, J.J. When Cells Suffocate: Autophagy in Cancer and Immune Cells under Low Oxygen. Int. J. Cell. Biol. 2011, 470597. [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Green, D.R.; Zou, W. Autophagy in tumour immunity and therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2021, 21, 281-297. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Chen, J.F.; Fu, X.T.; Ding, Z.B. Advances in autophagy regulation of macrophages involved in the construction of tumor microenvironment. Chin. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 28, 894-899.

- Yamamoto, K.; Venida, A.; Yano, J.; Biancur, D.E.; Kakiuchi, M.; Gupta, S.; Sohn A.S.W.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Lin E.Y.; Parker S.J.; et al. Autophagy promotes immune evasion of pancreatic cancer by degrading MHC-I. Nature. 2020, 581, 100-105.

- Mirnezami, R.; Nicholson, J.; Darzi, A. Preparing for precision medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 489-491.

- Mosele, M.F.; Westphalen, C.B.; Stenzinger, A.; Barlesi, F.; Bayle, A.; Bièche, I.; Bonastre, J.; Castro, E.; Dienstmann, R.; Krämer, A.; et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with advanced cancer in 2024: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 588-606. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, S.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, D. Nanomaterials for Cancer Precision Medicine. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1705660.

- Zhao, G.Y.; Yousefi, F.; Tsukamoto, I.; Moran, S.; Behfar, A.; Evans, C.; Zhao, C.F. A therapeutic-grade purified exosome system alleviates osteoarthritis by regulating autophagy through the BCL2-Beclin1 axis. J. Nanobiotechnology. 2025, Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Jalouli, M.; Bhajan, S. K.; Al-Zharani, M.; Harrath, A.H. A Comprehensive Review of Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery for Modulating PI3K/AKT/mTOR-Mediated Autophagy in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1868. [CrossRef]

- Kong, N.; Tao, W.; Ling, X.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Shi, S.; Ji, X.Y.; Shajii, A.; Gan, S.T.; Kim, N.T.; et al. Synthetic mRNA nanoparticle-mediated restoration of p53 tumor suppressor sensitizes p53-deficient cancers to mTOR inhibition. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaaw1565.

- Lu, Y.Y.; Fang, Y.Y.; Wang, S.S.; Guo, J., Song, J.L.; Zhu, L.; Lin, Z.K.; Wang, R.; Zhang, S.Y.; Qiu, W.S.; et al. Cepharanthine sensitizes gastric cancer cells to chemotherapy by targeting TRIB3-FOXO3-FOXM1 axis to inhibit autophagy. Phytomedicine. 2024, 135, 156161. [CrossRef]

- Koschade, S.E.; Klann, K., Shaid, S.; Vick, B.; Stratmann, J.A.; Thölken, M.; Meyer L.M.; Nguyen, T.D.; Campe, J.; Moser, L.M.; et al. Translatome proteomics identifies autophagy as a resistance mechanism to on-target FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2022, 36, 2396-2407.

- Jin, S. p53, Autophagy and tumor suppression. Autophagy. 2005, 1, 171-173.

- Wang, Y.; Gan, G.; Wang, B.; Wu, J.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, D.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.N.; Han, H.X.; Li, X.L.; et al. Cancer-associated Fibroblasts Promote Irradiated Cancer Cell Recovery Through Autophagy. EBioMedicine. 2017, 17, 45-56.

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yang, H.; Liang, T.; Bai, X. The"Self-eating" of cancer-associated fibroblast: A potential target for cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114762.

- Aita, V.M.; Liang, X.H.; Murty, V.V.; Pincus, D.L.; Yu. W.; Cayanis, E.; Kalachikov, S.; Gilliam, T.C.; Levine, B. Cloning and genomic organization of beclin 1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 17q21. Genomics. 1999, 59, 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.H.; Zhu, L.M.; Qiao, M.M.; Zhang, Y.P.; Jiang, S.H.; Wu, Y.L.; Tu, S.P. The XAF1 tumor suppressor induces autophagic cell death via upregulation of Beclin-1 and inhibition of Akt pathway. Cancer Lett. 2011, 310, 170-180.

- Kaur, S.; Changotra, H. The beclin 1 interactome: Modification and roles in the pathology of autophagy-related disorders. Biochimie. 2020, 175, 34-49.

- Wang, S.; Ma, D.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Y; Wang, S.; Zhou, W. Arsenic trioxide-based nanoparticles for enhanced chemotherapy by activating pyroptosis. Acta. Pharm. Sin. B. 2025, 15, 6001-6018. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.H.; Yin, X.W.; Lyu, C.Y.; Wang, J.Y.; Liu, K.; Cui, S.Y.; Ding, S.M.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, J.X.; Guo, D.L.; et al. Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Trigger Autophagy in the Human Multiple Myeloma Cell Line RPMI8226: an In Vitro Study. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2024, 203, 913-926. [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Chen, H.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, P.; Chen, J.; Jiang, S. Ultrasmall iron oxide nanoparticles induced ferroptosis via Beclin1/ATG5-dependent autophagy pathway. Nano Converg. 2021, 8, 10. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y, Lin, Y.X.; Qiao, Z.Y.; An, H.W.; Qiao, S.L.; Wang, L.; Rajapaksha R.P.Y.; Wang, H. Self-assembled

autophagy-inducing polymeric nanoparticles for breast cancer interference in-vivo. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27,

2627-2634.

- Puissant, A.; Fenouille, N.; Auberger, P. When autophagy meets cancer through p62/SQSTM1. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2012, 2, 397-413.

- Wei, H.; Wang, C.; Croce, C.M.; Guan J.L. p62/SQSTM1 synergizes with autophagy for tumor growth in vivo. Genes. Dev. 2014, 28, 1204-1216.

- Islam, M.A.; Sooro, M.A.; Zhang, P. Autophagic Regulation of p62 is Critical for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1405. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C.; Guan, K.L. mTOR: a pharmacologic target for autophagy regulation. J. Clin. Invest. 2015, 125, 25-32.

- Glaviano, A.; Foo, A.S.C.; Lam, H.Y.; Yap, K.C.H.; Jacot, W.; Jones, R.H.; Eng, H.; Nair, M.G.; Makvandi, P.; Geoerger, B.; et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling transduction pathway and targeted therapies in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2023, 22, 138. [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, J.A.Z.; Romagnoli, G.G.; Kaneno, R. Inhibiting autophagy to prevent drug resistance and improve anti-tumor therapy. Life Sci. 2021, 265,118745. [CrossRef]

- Woo, H.N.; Chung, H.K.; Ju, E.J.; Jung. J.; Kang, H.W.; Lee, S.W.; Seo, M.H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, J.S.; Park, H.J.; et al. Preclinical evaluation of injectable sirolimus formulated with polymeric nanoparticle for cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2012, 7, 2197-208.

- Jia. L.; Hao. S.L.; Yang, W.X. Nanoparticles induce autophagy via mTOR pathway inhibition and reactive oxygen species generation. Nanomedicine (London). 2020, 15, 1419-1435.

- Xu. J.; Patel, N.H.; Gewirtz, D.A. Triangular Relationship between p53, Autophagy, and Chemotherapy Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8991.

- Liu, Y.; Su, Z.; Tavana, O.; Gu, W.; Understanding the complexity of p53 in a new era of tumor suppression. Cancer Cell. 2024, 42, 946-967.

- Huang, X.; Cao. Z.; Qian, J.; Ding, T.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, S.Q.; Wang, X.L.; Ren, X.G.; Zhang, W.; et al. Nanoreceptors promote mutant p53 protein degradation by mimicking selective autophagy receptors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 545-553. [CrossRef]

- Camp, E.R.; Wang, C.; Little, E.C.; Watson, P.M.; Pirollo, K.F.; Rait. A.; Cole, D.J.; Chang, E.H.; Watson, D.K. Transferrin receptor targeting nanomedicine delivering wild-type p53 gene sensitizes pancreatic cancer to gemcitabine therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2013, 20, 222-228.

- Bilotta, M.T.; Antignani, A.; Fitzgerald, D.J. Managing the TME to improve the efficacy of cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 954992.

- Chen, F.; Zhuang, X.; Lin, L.; Yu, P.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Hu, G.; Sun, Y. New horizons in tumor microenvironment biology: challenges and opportunities. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 45.

- Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Mendes, R.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R. Targeting Tumor Microenvironment for Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20.

- Ashraf, R.; Kumar, S. Mfn2-mediated mitochondrial fusion promotes autophagy and suppresses ovarian cancer progression by reducing ROS through AMPK/mTOR/ERK signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2022, 79, 573. [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, E.; Lamprou, I.; Mitrakas, A.G.; Michos, G.D.; Zois, C.E.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Harris, A.; Koukourakis M. Autophagy Blockage Up-Regulates HLA-Class-I Molecule Expression in Lung Cancer and Enhances Anti-PD-L1 Immunotherapy Efficacy. Cancers. 2024, 16, 3272.

- Sari, D.; Gozuacik, D.; Akkoc, Y. Role of autophagy in cancer-associated fibroblast activation, signaling and

metabolic reprograming. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 11, 1274682.

- Liang, L.; Fu, J.; Wang, S.; Cen, H.; Zhang, L.; Mandukhail, S.R.; Du, L.R.; Wu, Q.N.; Zhang, P.Q.; Yu, X.Y. MiR-142-3p enhances chemosensitivity of breast cancer cells and inhibits autophagy by targeting HMGB1. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2020, 10, 1036-1046.

- Carew, J.S.; Nawrocki, S.T.; Kahue, C.N.; Zhang, H.; Yang. C.; Chung, L.; Houghton, J.A.; Giles, P.H.F.J.; Cleveland, J.L. Targeting autophagy augments the anticancer activity of the histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA to overcome Bcr-Abl-mediated drug resistance. Blood. 2007, 110, 313-322. [CrossRef]

- König, I.R.; Fuchs, O.; Hansen, G.; Mutius, E.; Kopp, M.V. What is precision medicine? Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700391.

- Awad, N. S.; Paul, V.; AlSawaftah, N.M.; Haar G.T.; Allen, T.M.; Pitt, W.G.; Husseini, G.A. Ultrasound-Responsive Nanocarriers in Cancer Treatment: A Review. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 589-612.

- Fulton, M. D.; Najahi-Missaoui, W. Liposomes in Cancer Therapy: How Did We Start and Where Are We Now. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6615.

- Son, K.H.; Hong, J.H.; Lee, J.W. Carbon nanotubes as cancer therapeutic carriers and mediators. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2016, 11, 5163-5185.

- Hari, S.K.; Gauba, A.; Shrivastava, N.; Tripathi, R.M.; Jain, S.K.; Pandey, A.K. Polymeric micelles and cancer therapy: an ingenious multimodal tumor-targeted drug delivery system. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2023, 13, 135-163. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.X.; Zhu, B.J. The Research and Applications of Quantum Dots as Nano-Carriers for Targeted Drug Delivery and Cancer Therapy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 207.

- Liu, L.; Tu, B.; Sun, Y.; Liao, L.L.; Lu, X.L.; Liu, E.G.; Huang, Y.Z. Nanobody-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. J. Control Release. 2025, 381, 113562.

- Steichen, S.D.; Caldorera-Moore, M.; Peppas, N.A. A review of current nanoparticle and targeting moieties for the delivery of cancer therapeutics. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 48, 416-427.

- Xiang, J.; Zhao, R.; Wang, B.; Sun, X.; Guo, X.; Tan, S.; Liu, W.J. Advanced Nano-Carriers for Anti-Tumor Drug Loading. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 758143. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Tan, C. Combination of microRNA therapeutics with small-molecule anticancer drugs: mechanism of action and co-delivery nanocarriers. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 81, 184-197.

- Wagner, A.J.; Ravi, V.; Ganjoo, K.N.; Tine, V.B.A.; Riedel, R.F.; Chugh. R. ABI-009 (nab-sirolimus) in advanced malignant perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComa): Preliminary efficacy, safety, and mutational status from AMPECT, an open label phase II registration trial. American Society of Clinical Oncology; 2019.

- Elimam, H.; El-Say, K.M.; Cybulsky, A.V.; Khalil, H.; Regulation of Autophagy Progress via Lysosomal Depletion by Fluvastatin Nanoparticle Treatment in Breast Cancer Cells. ACS omega. 2020, 5, 15476-15486. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lv, X.; Xu, L.; Liu, X.; Zhu, X.; Song, E.; et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles effectively regulate autophagic cell death by activating autophagosome formation and interfering with their maturation. Part. Fibre. Toxicol. 2020, 17, 46. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).