1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

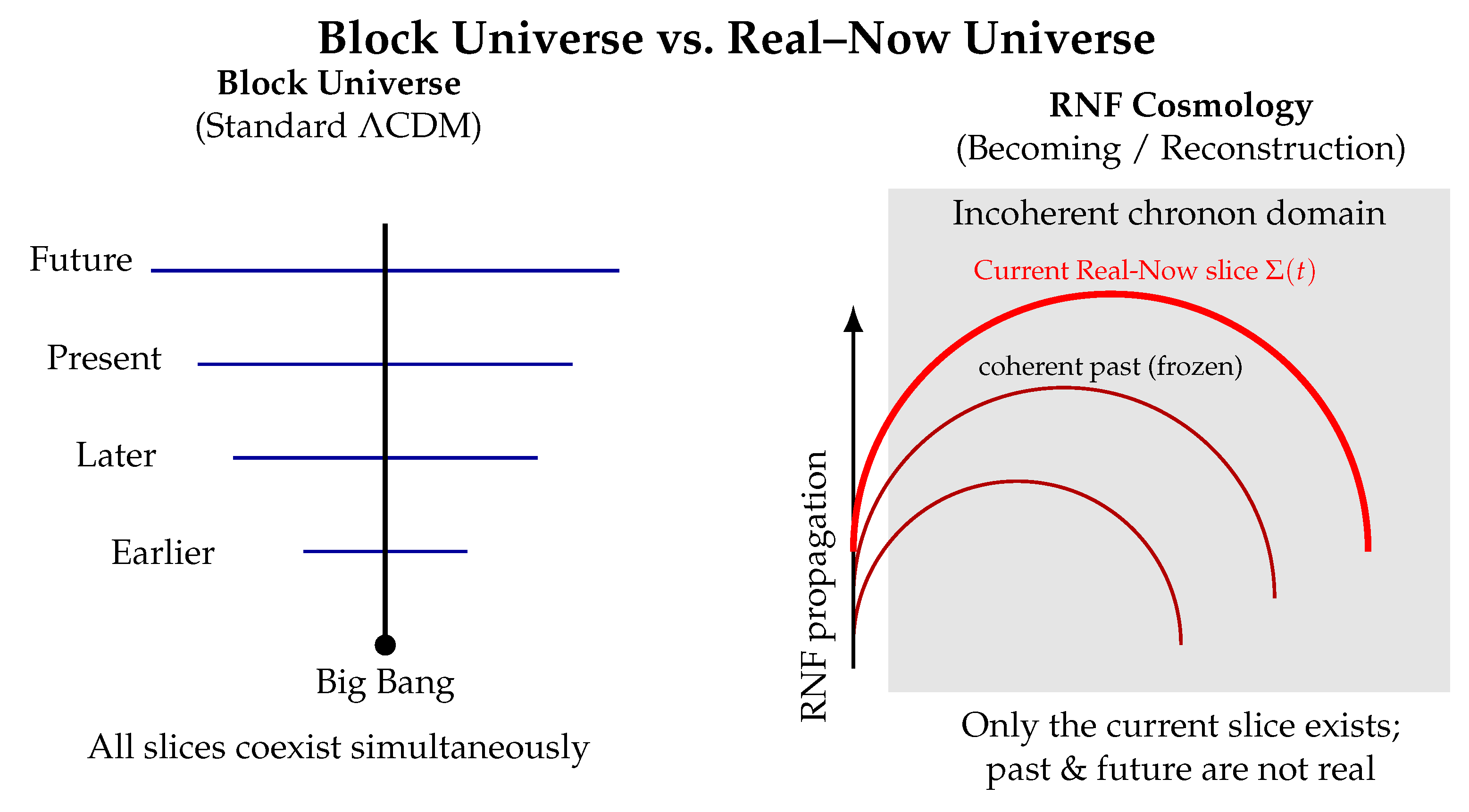

Standard cosmology begins with a fully formed four-dimensional spacetime equipped with a Lorentzian metric. In this block-universe picture, the entire manifold already exists, with no distinguished

present, and with spacetime geometry postulated rather than generated. Although empirically successful, this framework leaves several foundational questions unresolved: the origin of large-scale smoothness and near-flat curvature [

1,

2], the horizon problem and the associated need for an inflationary scalar [

3,

4,

5], the extreme fine-tuning implied by dark energy, and the unexplained microphysical nature of dark matter [

6,

7].

A deeper conceptual issue underlies these puzzles: spacetime symmetries are assumed a priori, rather than explained as emergent properties of an underlying physical structure. Lorentz invariance, causal cones, elastic curvature response, and universal propagation speeds are all imposed at the level of the metric, even though the metric itself is not associated with identifiable microscopic degrees of freedom.

A more physical perspective is therefore to treat spacetime as an emergent medium. In every other domain of physics, robust symmetries, propagation speeds, elastic response, large-scale coherence, defect formation, and domain growth arise from ordered phases of underlying microstructures. By contrast, CDM assigns these properties directly to the metric, leading to several longstanding conceptual tensions:

The invariance of c is postulated rather than derived from a microscopic alignment or ordering mechanism.

Curvature behaves like an elastic strain, yet no underlying degrees of freedom exist to carry or regulate such strain.

Cosmic expansion is driven by a constant vacuum energy whose origin remains obscure.

The observed near-flat geometry and horizon-scale correlations require either fine-tuned initial conditions or an inflationary field whose own initial conditions are left unspecified.

These considerations motivate a framework in which spacetime geometry and its symmetries are generated dynamically from a microscopic alignment field, much as elastic, optical, and transport properties emerge from the ordering of constituents in condensed phases.

Real–Now–Front (RNF) cosmology develops precisely such a generative picture. The Universe does not begin as a pre-existing spacetime but as a pre-geometric chronon medium. Aligned regions nucleate and merge; their boundary—the

Real–Now–Front (RNF)—propagates through the unaligned domain, constructing new spatial slices. From within the Universe, this advancing hypersurface is experienced as the evolving physical present. The central organizing principle is the

Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP), which governs chronon alignment, reconstructs matter patterns, and induces the emergent Lorentzian metric [

8]. Crucially, TCP drives each newly reconstructed region toward a preferred coherence–curvature density, so that cosmic expansion, structure formation, void growth, and local collapse arise as distinct local responses of a single coherence-restoration mechanism.

A second microphysical ingredient is the

Chronon Exclusivity Principle (CEP), which forbids curvature concentrations from overlapping within a single causal cell. Near this bound the medium becomes effectively incompressible and forms finite-density, nonsingular cores with universal scaling

. Small cores behave as horizonless cold dark matter candidates (

Micro Chronon Condensates, MCCs), while massive cores reproduce the exterior geometry of GR black holes with CEP-regulated interiors. A single TCP–CEP dynamical process therefore accounts for compact objects across the entire mass range [

7,

9,

10,

11].

Within this framework, cosmic expansion, late-time acceleration, void dynamics, and the dark sector all emerge not from added fields or finely tuned initial conditions, but from the local, self-tuning response of the chronon medium as the Real–Now–Front advances.

1.2. Why Spacetime Should Be an Emergent Medium

The introduction of an underlying medium is motivated by physical necessity. Several key features of modern cosmology become more natural, and in some cases only intelligible, when geometry arises from microphysical alignment dynamics:

Universality of c.

A single invariant propagation speed c for all locations, observers, and all types of probes (photons, gravitational waves, massless neutrinos) is difficult to justify in a stage-only picture. In RNF, the light cone is the characteristic cone of pattern-preserving chronon alignment dynamics. Lorentz invariance then emerges as the symmetry of an ordered phase, rather than a primitive axiom.

Curvature as elastic response.

Einstein’s equation,

treats the metric as if it could be

deformed by energy–momentum. But how can an abstract geometric field, with no physical microstructure, respond elastically to stress? In RNF, curvature is not imposed on a mathematical stage but arises as the coarse-grained strain of aligned chronon configurations, making Einstein’s equation a constitutive relation of an underlying medium [

12,

13].

Late-time accelerated expansion.

Unlike CDM, where acceleration is imposed by a constant vacuum energy, RNF cosmology allows it to emerge kinematically. As vacuum-rich regions come to dominate cosmic volume, TCP-driven metric stretching approaches a steady rate, yielding an accelerated, de Sitter–like phase without dark energy.

Early-universe smoothing.

Near-flatness and large-scale uniformity arise from TCP-driven relaxation during RNF percolation, rather than from fine-tuned initial conditions or inflation.

Arrow of time.

A block universe lacks an ontological distinction between past and future. RNF provides a physical advancing present: aligned slices form the past, unaligned regions constitute the future, and the RNF itself generates new spacetime.

Becoming and the physical present.

A stage-only spacetime cannot explain why a single definite outcome appears in quantum measurements: the block universe contains all events at once and provides no mechanism of `becoming.” In RNF cosmology the advancing Real–Now–Front is a physical process that creates new slices by selecting a single coherent continuation of chronon patterns. Outcome selection is therefore tied to the generative construction of spacetime itself, giving a concrete physical meaning to the present.

These considerations together make a strong physical case that cosmology requires a microphysical substrate. RNF cosmology provides one concrete realization of such a substrate, introducing no additional fields beyond the chronon medium and its alignment dynamics. It is built on three coupled ingredients:

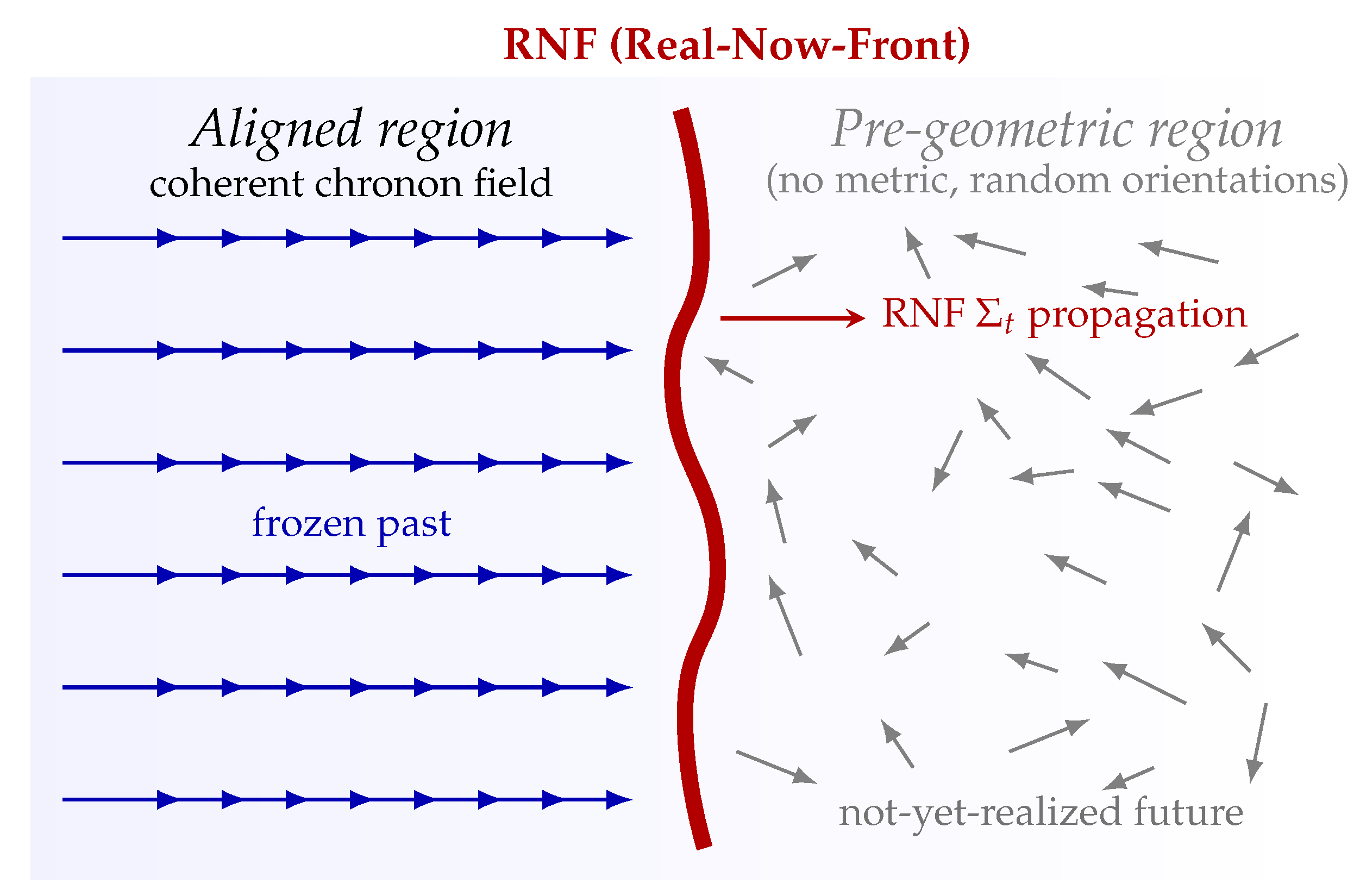

The Real–Now–Front (RNF): An advancing three-surface that generates spacetime. Behind the RNF lies the aligned, metric-bearing region; ahead lies a non-geometric domain. From within the Universe the RNF is experienced as the advancing present.

The chronon field : A unit timelike covector whose alignment induces both the emergent metric and the temporal direction. Unaligned regions carry no geometry. Early alignment proceeds through defect formation and coarsening [

14,

15].

The Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP): A local variational rule that aligns chronons as the RNF advances, reconstructing matter patterns and inducing . TCP drives each reconstructed region toward a preferred coherence–curvature density , which is central to the dynamics described below.

A key geometric consequence follows directly from the generative nature of the RNF:

Advancing the RNF forces each newly formed slice to rescale its geometry.

TCP requires every reconstructed patch to maintain the characteristic coherence density

(See

Section 6.2) while RNF propagation continually increases the aligned four-volume behind the front. To satisfy both constraints, the induced spatial metric must either

stretch or

shrink. This produces a local TCP bifurcation with three regimes:

Stretching branch (): Under-curved regions lower their TCP energy by expanding the metric, generating the familiar Hubble flow. Because RNF propagation depends on local chronon structure, the expansion rate becomes self-tuning: voids stretch more rapidly, and regions near massive objects or MCCs stretch more slowly.

Near-equilibrium branch (): Mild adjustments produce GR and FRW-like behavior.

Shrinking branch (): Over-curved regions lower their TCP energy by metric contraction, initiating collapse into chronon condensates (MCCs).

Chronon soliton condensates formed during early alignment behave as stable, compact, lensing dark-matter objects. Their properties follow from the

Chronon Exclusivity Principle (CEP), which forbids curvature knots from overlapping within a causal cell and thereby enforces a finite-density, nonsingular core with

(

Appendix D). Small CEP-saturated objects serve as horizonless cold dark matter; large ones reproduce the exterior geometry of GR black holes while avoiding singularities.

RNF cosmology thus ties the emergence of geometry, cosmic expansion, the arrow of time, and the dark sector to a single generative mechanism: the propagation of the RNF through the chronon medium.

Recent advances in Chronon Field Theory (ChFT) supply the mathematical foundation. Lorentzian signature emerges dynamically from chronon ordering [

12], and Einstein–Yang–Mills structure appears as the long-wavelength limit of chronon alignment [

13]. RNF cosmology extends these results by identifying RNF propagation as the engine that constructs spacetime itself.

Summary of Contributions

Conceptually, RNF cosmology builds on the

Evolving Block Universe (EBU) perspective introduced by Ellis [

26,

27], providing a concrete microphysical mechanism by which spacetime itself is generated slice by slice. Building on this foundation, this paper develops

Real–Now–Front (RNF) cosmology as a generative framework and establishes the following main advances:

Generative origin of spacetime: Spacetime is created slice by slice as the RNF advances into an unaligned chronon domain, rather than being assumed as a pre-existing four-dimensional manifold.

Local geometric mechanism for cosmic expansion: RNF propagation forces the induced spatial metric to stretch in order to restore temporal coherence, producing the Hubble law and late-time acceleration without invoking dark energy. Expansion is intrinsically local and self-tuning.

Unified origin of dark energy and dark matter: The stretching branch yields cosmic expansion (phenomenologically replacing dark energy), while the shrinking branch forms CEP-regulated chronon cores () that serve as cold dark matter and compact objects.

Early-universe smoothing without inflation: Alignment-domain growth in the pre-geometric chronon medium naturally produces large-scale isotropy and near-flatness without requiring an inflationary scalar field.

Mild two-metric phenomenology: Photon and matter excitations couple to slightly different chronon-based effective metrics, leading to small but testable deviations in cosmological distance–redshift relations.

Together these elements yield a unified microphysical picture in which geometry, expansion, compact objects, and the dark sector all emerge from a single generative process: the propagation of the Real–Now–Front through the chronon medium.

Scope and limitations.

The present work is intended as a conceptual and theoretical foundation rather than a precision cosmological fit. Quantitative confrontation with CMB anisotropies, large-scale structure statistics, and detailed numerical simulations of RNF alignment dynamics are identified as important future directions. The framework is constructed to be compatible with the large-scale phenomenology of CDM while addressing its foundational limitations at the level of microphysics and spacetime ontology, rather than to replace standard cosmological modeling tools at this stage.

2. RNF as a Physical Theory of the Present

2.1. Why the Present is Dynamical

Standard cosmology assumes a fully formed four-dimensional manifold with a pre-existing metric. In this traditional “block-universe” view [

23,

25], the entire cosmic history is embedded in a fixed spacetime geometry with no physically privileged

present. Large-scale smoothness, near-flat curvature, and correlated matter distribution must therefore be imposed as initial conditions on the entire four-dimensional structure at once [

24,

25].

A generative alternative, introduced most prominently by Ellis in the

Evolving Block Universe (EBU) framework [

26,

27], is to treat the present as a physically meaningful and dynamically advancing entity. In the EBU and related becoming-based approaches [

26,

27,

28,

29], the Universe is constructed slice by slice as an advancing hypersurface actualizes new regions of spacetime. This perspective aligns naturally with our direct experience that only the present is physically accessible, and that decisions and actions are made

now, influencing a future that is not yet realized.

RNF cosmology provides a concrete microphysical implementation of this idea. The Real-Now-Front (RNF) is a codimension-one surface whose propagation is governed by the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP). Geometry, effective causal description, and matter fields are reconstructed only in the region through which the RNF has passed; ahead of the front the chronon field is unaligned and lacks metric structure. Spacetime is therefore built dynamically rather than assumed from the outset, supplying a microphysical realization of Ellis’ dynamical present within an emergent-spacetime framework.

A viable emergent-spacetime picture must also specify

how geometry is generated. The RNF provides a definite boundary between realized geometry and a pre-geometric domain, together with a natural ordering that sequences the construction of successive slices. The following sections analyze the quantitative consequences of this mechanism, while Appendices

Appendix A and

Appendix C present the mathematical formulation of RNF propagation and its homogeneous expansion law.

2.2. Definition of the Real–Now–Front

The RNF is a smooth, spacelike hypersurface that advances monotonically through an underlying pre-geometric chronon domain. At the RNF, the chronon field undergoes alignment, and the patterns inherited from earlier slices are reconstructed into a newly actualized three-dimensional slice. The induced metric and effective matter fields arise as part of this reconstruction, while the aligned region left behind constitutes the frozen past. All apparent physical processes—including cosmological evolution—emerge from the ordered reconstruction of patterns across successive RNF advances.

Ahead of the RNF lies a region that is not spacetime in the usual sense: the chronon field is unaligned, and no metric, distances, or causal structure exist. This domain resembles Wheeler’s pregeometry and modern emergent-gravity precursors [

19]. When the RNF reaches such a region, the Temporal Coherence Principle aligns

and incorporates the region into the reconstructed sequence of physical slices.

In this way the RNF functions as the physical present: the generative boundary at which new spacetime slices are instantiated. The future remains non-metric until the RNF arrives, while the past consists of the stack of previously reconstructed, frozen slices.

2.3. Forest-Fire Analogy

To illustrate the unfamiliar role of the RNF, consider a forest fire advancing across a landscape. Ahead of the fireline lies unburned forest with no flame or temperature structure; at the fireline local chemistry ignites combustion; behind it lies a coherent thermal region.

The RNF picture parallels this:

the unaligned domain resembles unburned forest, lacking geometric structure;

the RNF front corresponds to the fireline, activating local degrees of freedom;

the aligned spacetime corresponds to the burned region, where coherent chronon alignment defines geometry;

the copying of persistent chronon patterns resembles the replication of flame structure at the fireline.

This analogy highlights two points. First, the RNF selects a preferred generative direction, similar to the irreversible transition from unburned to burned states. Second, the RNF does not generate coherence from nothing: it reconstructs alignment by copying persistent chronon patterns from previous slices. This copying mechanism underlies the expansion behavior derived in

Section 8 and

Appendix A.

2.4. Pre-Geometric Domain

The domain ahead of the RNF lacks metric structure: although a manifold topology may exist, there is no notion of distance, curvature, or volume. Without volume, there is no meaningful sense in which the RNF could “run out’’ of unaligned region; such questions require geometry, which only appears after alignment.

This also reframes the cosmological beginning. The RNF has a finite past consisting of earlier aligned slices, but the pre-geometric domain need not possess a beginning or boundary. The Big Bang corresponds not to a geometric singularity but to the first slice on which the chronon field achieved self-sustaining alignment, a view consistent with nonsingular emergent-gravity perspectives [

19].

2.5. Temporal Coherence Principle

The Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP) governs chronon alignment and determines the propagation of the RNF [

8]. Intuitively, the TCP aligns the chronon field so as to minimize local misalignment gradients, akin to order-parameter dynamics in nonequilibrium systems [

30]. This behavior parallels domain-wall motion under gradient flow and pattern formation in condensed-matter systems [

31,

32].

Two consequences are central:

Alignment Rule. As the RNF encounters an unaligned region, the chronon field is driven into a coherent configuration, inducing the local metric and reconstructing matter fields.

Propagation Rule. The RNF advances because misaligned regions ahead of the front are favored sites for further alignment. Geometry grows outward as the RNF sweeps through the pre-geometric domain.

The TCP field Equation (

3) and well-posedness conditions appear in

Section 4 and

Appendix A, and the resulting homogeneous expansion law in

Appendix C.

In summary, the RNF provides the physical present, the TCP supplies the law that generates spacetime, and the pre-geometric domain provides the substrate through which this generative process unfolds. Together these ingredients form the conceptual and dynamical foundation of RNF cosmology. See

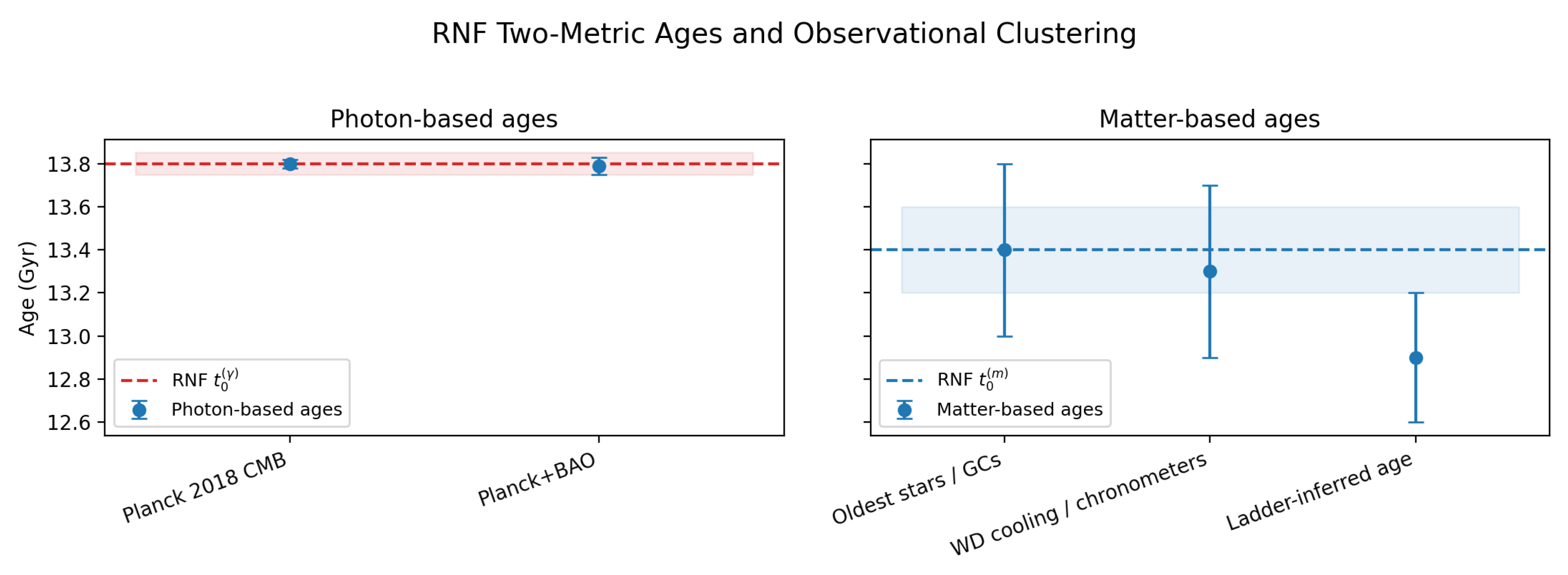

Figure 1 for a schematic illustration of RNF propagation. The RNF is the physical present: the three–dimensional slice on which all fields and measurements exist, advancing irreversibly as new spacetime is generated.

3. RNF Propagation and Operational Lorentz Invariance

3.1. Effective Spacetime Description and RNF Reconstruction

Before discussing propagation and Lorentz invariance, it is important to clarify the role of standard spacetime language within the RNF/ChFT framework. In RNF cosmology, an RNF slice is not a dynamical arena in which processes unfold. No physical motion, signal transmission, or causal influence occurs within a slice. Instead, all apparent dynamics arise from the reconstruction of patterns across successive RNF advances.

Nevertheless, once reconstructed, the slice-by-slice dynamics admits an operationally equivalent description in the familiar block-universe language. Concepts such as signal propagation, light cones, worldlines, and Lorentz invariance may therefore be used throughout as effective descriptors of RNF reconstruction dynamics, provided it is kept in mind that they are not ontologically fundamental. This effective description is fully adequate for observational and phenomenological analysis, and it is only when the generative role of the RNF itself is under consideration —such as in front propagation or measurement selection—that RNF-native language becomes essential.

With this understanding, we proceed using conventional spacetime terminology while interpreting it as an emergent and operationally equivalent description of RNF reconstruction.

3.2. RNF Advance and Microscopic Alignment Scale

A central property of RNF cosmology is that the Real–Now–Front (RNF) advances into the pre-geometric chronon domain at a fixed microscopic alignment scale. This advance is not defined relative to any spacetime metric—no metric exists ahead of the RNF—but reflects the intrinsic rate at which chronon alignment relaxes in the underlying medium.

From the hyperbolic TCP field equation (

Appendix A,

Section 4), the characteristic alignment scale is

which may be described, in effective language, as the maximal rate at which coherent patterns can be reconstructed across RNF advances in a nonlinear order-parameter medium [

30].

Importantly, this microphysical scale governs only the generative process by which aligned slices and their induced metrics come into existence. It has no operational meaning for observers, who exist only on already-aligned RNF slices and have access solely to the emergent geometry.

3.3. Meta-Time and the Generative Order of Slices

The RNF does not move within physical time; instead, physical time is defined only after a slice has been aligned and endowed with a metric . Ahead of the RNF there are no rods, clocks, or causal structure. The advance of the RNF is therefore parametrized by a more primitive meta-time, a bookkeeping variable that orders the creation of successive slices.

Meta-time is not an additional physical dimension. It labels discrete generative steps of RNF reconstruction, much as an iteration parameter labels updates in lattice relaxation or domain-growth models. All physical observers exist strictly within the aligned region and have access only to the emergent Lorentzian geometry. Consequently, the microphysical direction of RNF advance is operationally unobservable.

This remains true even when a slice contains matter, curvature, or defect-induced structure. After each reconstruction step, the TCP ensures that all chronon patterns—including “defect + curved vacuum” configurations—are fully equilibrated on that slice. The emergent metric therefore already incorporates the curvature required for local coherence, and no trace of the generative ordering survives within the observable description.

3.4. Co-moving Concealment Principle

These considerations lead to the:

Co-moving Concealment Principle (CCP). All observable physics occurs on fully aligned RNF slices whose local geometry has already been TCP-stabilized. Because reconstruction precedes the existence of clocks, signals, or causal ordering, the microphysical direction and scale of RNF advance cannot be detected by observers within spacetime. Observable phenomena are governed solely by the induced Lorentzian metric .

The CCP is strengthened by the three-regime structure of TCP reconstruction: whether a patch stretches, adjusts curvature, or collapses into a Micro Chronon Condensate, the outcome is always a locally equilibrated geometric structure. Any geometric adjustment associated with RNF reconstruction is completed before the slice becomes part of the observable universe. As a result, no measurement can access the generative asymmetry.

3.5. Compatibility with Lorentz symmetry Tests

The decoupling between microphysical generative ordering and emergent Lorentz invariance parallels mechanisms in analogue-gravity systems, condensed-matter emergence models, Einstein–Æther frameworks, and Hořava–Lifshitz constructions [

17,

33,

34,

35]. In each case, a preferred microstructure exists but remains concealed by the equilibrated effective geometry.

RNF cosmology must satisfy stringent empirical bounds on Lorentz violation. Observational constraints from multi-messenger observations [

36], high-energy neutrinos [

37], ultra–high-energy cosmic rays [

38], and the SME program [

39] require any violations to be below

–

. The CCP ensures compliance: the only geometry accessible to observation is the fully TCP-stabilized metric, not the microphysical reconstruction dynamics that produced it.

Even in regions where TCP actively adjusts curvature—such as near solitons, MCCs, or mild coherence deficits—this adjustment is completed at reconstruction. Once a slice is formed, both massive and massless excitations admit a consistent effective spacetime description with no memory of the RNF ordering. Lorentz invariance is therefore preserved to all experimentally accessible precision.

3.6. Summary

The distinction between meta-time and emergent time, together with slice-by-slice TCP equilibration, ensures that:

a preferred generative ordering exists at the microphysical level,

all observable physics admits a fully Lorentz-invariant effective description,

coherence-driven geometric adjustments leave no operational imprint of the RNF,

and no experiment within the aligned region can detect the RNF or infer a preferred frame.

RNF cosmology therefore contains a microphysical generative ordering associated with chronon alignment, but this structure is completely concealed by the TCP-stabilized effective geometry, leaving observable physics strictly Lorentz invariant.

4. Chronon Field and TCP: Minimal Mathematical Formulation

RNF cosmology is based on a single structural hypothesis: spacetime geometry is

induced by the alignment of a smooth unit-timelike covector field

, the

chronon field. The Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP) governs this alignment and supplies the restoring dynamics that selects, stabilizes, and preserves geometric patterns. As in other ordering phenomena in condensed-matter or statistical systems [

14,

30], coherence of an order-parameter field controls the emergence of macroscopic structure. Here, the chronon medium plays this role for geometry itself, including its curvature, causal structure, and matter content.

4.1. Chronon Field

The chronon field is the fundamental pre-geometric field of the theory: a smooth covector on the underlying manifold whose alignment creates spacetime. It is not a particle, not a time quantum, and not a scalar “clock’’ field. Rather, it is an order-parameter–like orientation field whose coherent domains generate the emergent metric.

When the RNF aligns a region,

enters an ordered phase satisfying

and small gradients

encode a well-defined temporal direction and induce the emergent Lorentzian metric

[

8,

12]. Where

is highly sheared or disordered, the region is pre-geometric: the manifold exists, but no physical metric or causal structure has yet formed.

Similar unit-timelike fields occur in Einstein–Æther theory [

34], ADM formulations [

40], and analogue-gravity systems [

17]. But in RNF cosmology,

is not auxiliary: its alignment

creates the spacetime manifold and determines the microscopic origin of causal cones, curvature, matter, and gauge fields.

4.2. The Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP)

The Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP) specifies the local dynamical rule by which the ontological chronon field aligns and relaxes as the Real–Now–Front (RNF) advances. TCP is not a phenomenological postulate but a local variational principle governing chronon ordering on an underlying smooth manifold. Its role is to suppress misalignment, stabilize curvature-bearing structures, and enforce a preferred ordered phase from which spacetime geometry emerges.

A minimal effective action capturing these requirements is

where:

penalizes chronon misalignment and large gradients;

stabilizes finite-size curvature concentrations and prevents Derrick-type collapse;

enforces the unit timelike normalization .

The effective measure reflects the coarse-grained volume element induced by aligned chronons; its precise form is not required here.

Varying (

2) yields the local TCP equation of motion,

where

collects quartic-gradient corrections responsible for soliton stabilization and curvature saturation. Equation (

3) is hyperbolic, with characteristic speed

which governs chronon-pattern relaxation in the pre-geometric medium. This speed is

not the physical speed of light; causal structure and null cones emerge only after coherent alignment has produced an effective metric.

TCP as a coherence-restoration principle.

A crucial consequence of (

2) is that TCP does not favor either perfect vacuum alignment or arbitrarily dense curvature. Excessive homogeneity increases the energetic cost of perturbations through the quartic term, while excessive curvature raises the quadratic gradient energy. The competition between these contributions selects a preferred local

coherence–curvature density , corresponding to a stable “defect + curved vacuum” pattern. This preferred density is not imposed externally; it is an intrinsic property of the chronon medium.

During RNF reconstruction, the internal chronon pattern of a comoving patch is copied from slice to slice. To leading order, TCP therefore cannot modify the pattern itself on the reconstruction timescale; instead, it acts by adjusting the geometric assignment to that pattern. As shown in

Section 6.2 and

Section 8.5, deviations of the inherited coherence density from

force TCP to respond geometrically: metric stretching when coherence is too high, metric shrinking when it is too low, and curvature redistribution near equilibrium.

Thus the same local TCP equation (

3) underlies: (i) early-universe smoothing and near-flatness, (ii) the local Hubble law from RNF kinematics, (iii) the stretching–equilibrium–shrinking bifurcation, and (iv) the formation of CEP-saturated solitonic cores.

4.3. Metric Emergence and Curvature as Part of the Pattern

When

is aligned on an RNF slice, a Lorentzian metric emerges as a functional of the chronon field:

with

defined by

This parallels ADM decompositions but arises here from chronon alignment rather than from an assumed manifold structure.

Crucially, is not arbitrary: it is selected by TCP so that the local defect + curved vacuum structure has the correct coherent pattern density. Curvature is therefore not an independent geometric field but the self-consistent spatial distortion required for TCP coherence. A soliton with insufficient curvature induces further curvature via TCP; a soliton with excess curvature induces stretching to reduce curvature density. This logic underlies the geometric bifurcation between expansion, curvature equilibria, and collapse.

Where

is not aligned,

is undefined, consistent with the pre-geometric interpretation of

Section 2.

4.4. Invariant Standards and Operational Geometry

A metric becomes operational only when invariant physical standards of length and phase exist. In RNF cosmology these standards arise dynamically: alignment at the Planck correlation scale generates a fixed quantum of symplectic flux, the minimal quantum of action

[

8]. Relations such as

provide the clocks and rods needed to

measure the emergent metric. Thus the chronon field not only produces geometry but also supplies the measurement standards that make geometry physical.

4.5. RNF Propagation as an Energy-Reducing Solution of TCP

An RNF slice is characterized by:

Because misalignment carries higher TCP energy, the front advances by aligning regions ahead of it—exactly analogous to advancing phase boundaries in non-equilibrium pattern-forming systems [

31]. A key property is

copying invariance: once TCP stabilizes a “defect + curvature” pattern on

, the RNF copies that pattern into

, where only the metric embedding may adjust to restore the preferred coherence density. This copying mechanism underlies matter persistence, gauge reconstruction, and the slice-by-slice geometric responses (stretching, curvature adjustment, or shrinking) discussed in

Section 8.6.

4.6. Emergent GR, Gauge Fields, and Matter

Chronon Field Theory (ChFT) provides a unified microphysical origin for spacetime geometry, gauge interactions, and matter fields. Only a brief summary is provided here; detailed derivations are given in Refs. [

8,

13].

Emergent Einstein dynamics.

In the aligned phase, coarse-graining the TCP alignment equation yields an effective metric theory whose long-wavelength limit reproduces Einstein dynamics. Specifically, variations of the chronon alignment energy with respect to the induced metric give

where

is determined by chronon stiffness parameters and

encodes alignment stress. General relativity thus appears as the hydrodynamic limit of chronon ordering rather than a fundamental postulate.

Emergent gauge structure.

Internal rotations and twists of the chronon polarization bundle induce effective gauge connections. At long wavelengths these reduce to standard Abelian and non-Abelian gauge fields, with curvature two-forms

arising from chronon twist modes [

13]. Gauge invariance is therefore emergent, reflecting redundancy in the description of aligned chronon configurations rather than an imposed symmetry principle.

Bosons as transverse excitation modes.

Small-amplitude transverse fluctuations of the aligned chronon field act as propagating bosonic degrees of freedom. In particular, the normalization constraint

implies gapless transverse modes that propagate within each RNF slice along null directions of the photon metric:

These modes preserve the internal pattern and therefore do not undergo slice-by-slice reconstruction.

Matter as topological solitons.

Fermionic matter arises as localized, topologically protected solitonic excitations of the chronon alignment field. Quartic-gradient (Skyrme-like) terms stabilize these defects, whose combined “defect + curved vacuum” configuration represents a local TCP energy minimum. Mass corresponds to the integrated curvature and misalignment energy of the soliton core, while internal topological structure accounts for charge and chirality. Because solitons carry intrinsic curvature, they must be reconstructed at each RNF advance, naturally coupling them to the reconstruction metric.

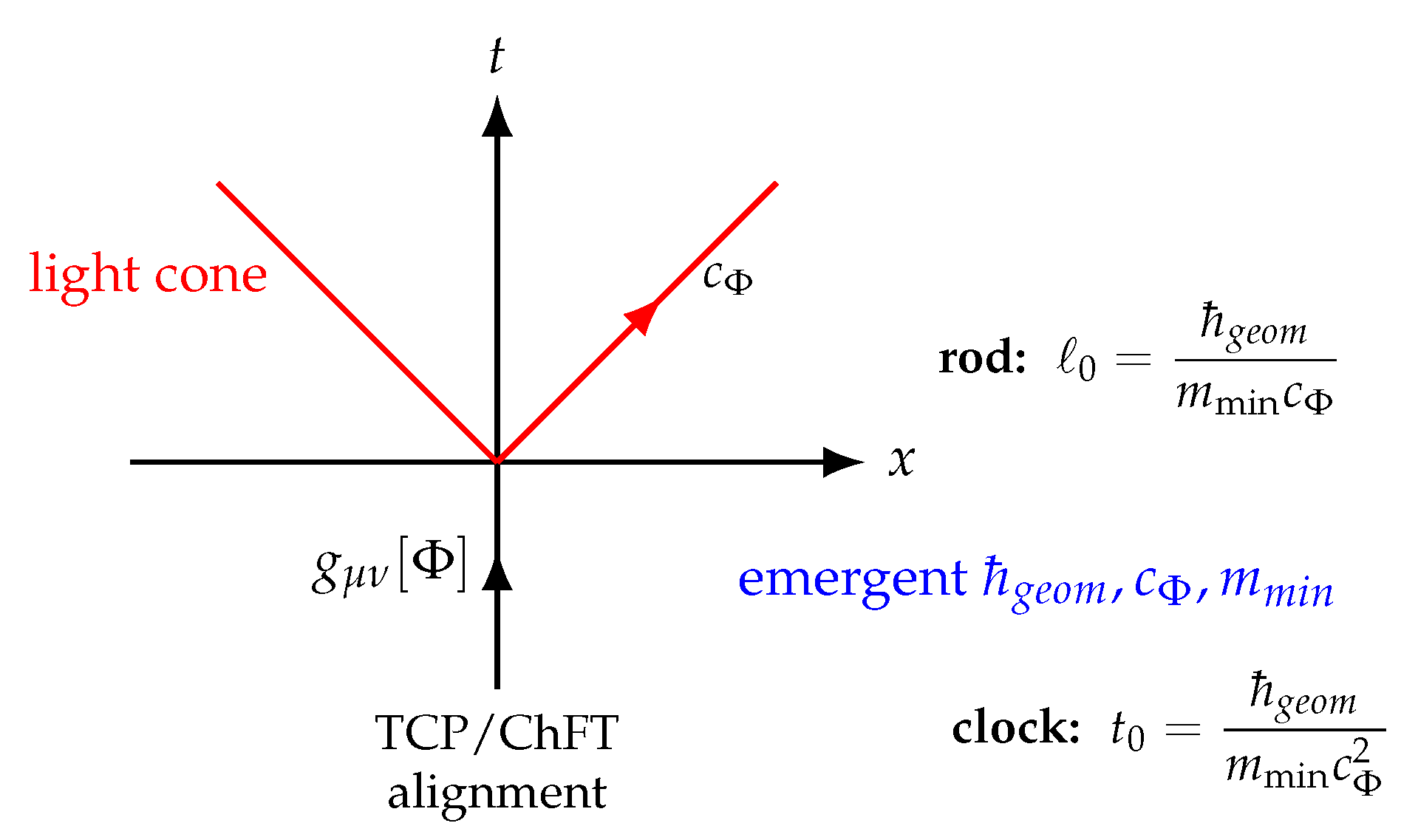

Emergent physical constants and operational geometry.

A key consequence of ChFT is that the fundamental constants required for an operational spacetime geometry are not imposed but

emerge dynamically. As shown in Ref. [

8], the effective Planck constant

arises from the symplectic flex and minimum action associated with stable chronon solitons, while the characteristic propagation speed

emerges from the TCP alignment dynamics. The lightest stable soliton is identified with the electron, whose mass

, charge

e, and coupling strengths follow from integrated curvature and polarization structure of the soliton core.

Together,

,

, and

define natural operational units: a fundamental length (rod)

and a fundamental time (clock)

corresponding to the Compton wavelength and period of the minimal soliton. These emergent rods and clocks provide the physical basis for Lorentzian metric measurements. Accordingly, the spacetime metric used in RNF cosmology is not merely a geometric construct but an

operationally grounded structure, anchored in the same chronon microphysics that generates matter and interactions.

Cosmological relevance.

RNF cosmology therefore requires no additional matter or interaction sector beyond the chronon field itself. It inherits:

GR-like dynamics from aligned chronon hydrodynamics,

Standard Model–like gauge interactions from polarization geometry,

photons as transverse excitation modes,

matter as solitonic curvature concentrations,

and persistent worldlines via RNF reconstruction.

Together, these results establish the chronon field as the single microphysical substrate underlying geometry, interactions, and matter, providing a closed and self-consistent foundation for the cosmological framework developed in this paper.

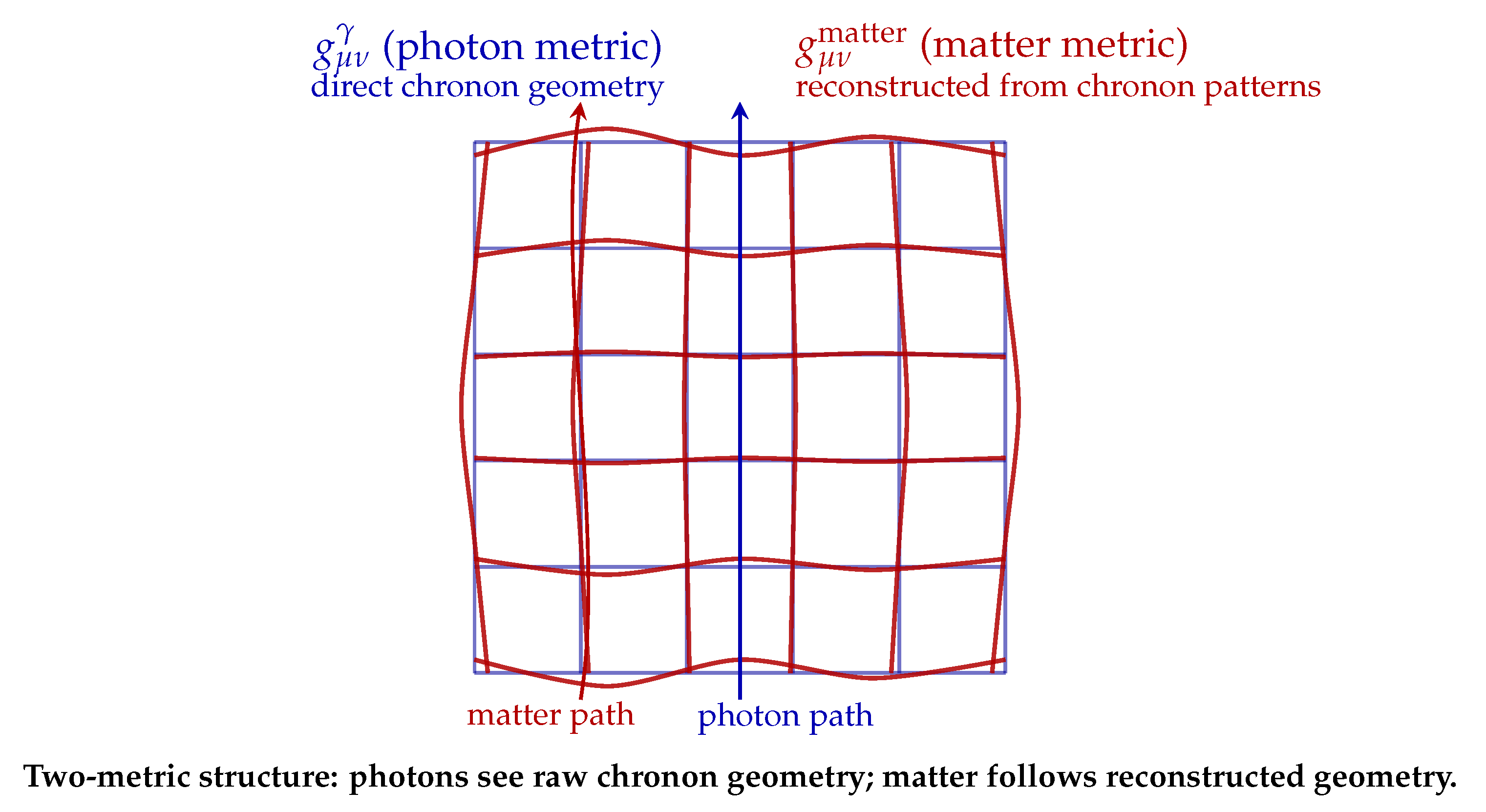

Figure 2 is a schematic illustration of the emergent metric structure.

5. Propagation of the RNF as Local 4D Reconstruction

In RNF cosmology, the advance of the Real–Now–Front (RNF) is the fundamental generative process by which spacetime is created. Nothing evolves within a pre-existing 4D manifold. Instead, when the RNF encounters unaligned chronon regions, those chronons align to the incoming “defect + curved vacuum” pattern and thereby acquire metric structure. The universe is thus built slice-by-slice: the RNF is a propagating 3-surface that continuously reconstructs spacetime one infinitesimal layer at a time.

This section formulates RNF propagation directly from the TCP equation and clarifies how continuity, motion, curvature, and matter arise from strictly local chronon alignment dynamics.

5.1. Local Reconstruction from the TCP Equation

The leading-order TCP equation in an already-aligned region is

subject to the unit-norm constraint

. All geometric quantities—curvatures, covariant derivatives, and the induced spatial Laplacian—are defined only on the

aligned side of the RNF; the unaligned domain carries no metric and no notion of 4D geometry.

Let

denote slices displaced by proper distance

ℓ along the aligned normal

, with

at the RNF. In Gaussian normal coordinates on the aligned side,

and the d’Alembertian decomposes as

In the

slow-front regime relevant for cosmology, chronon alignment relaxes much more rapidly than the RNF advances. Hence

and Equation (

10) reduces on each slice to the elliptic equation

which determines the TCP-smoothing of boundary alignment data.

Let

be the current slice and

the slice created after an RNF advance

. Because

is continuous on the aligned side,

the newly created slice inherits the same alignment pattern up to small smoothing corrections. Solving (

11) yields the first-order reconstruction law

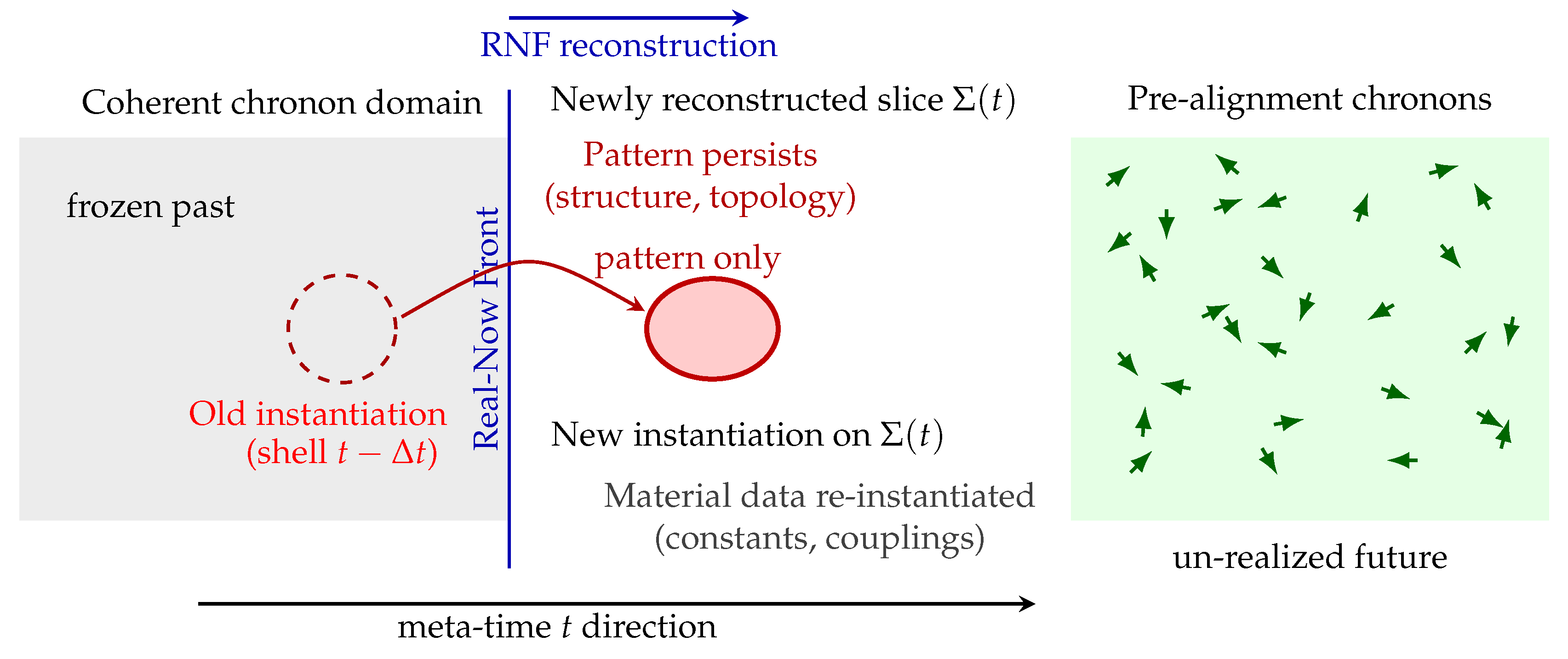

Copying invariance and curvature inheritance.

Equation (

11) implies that the RNF does not create new structure; instead it

copies the existing “defect + curved vacuum” pattern onto the next slice and then allows TCP to restore the preferred coherence density. This is the microscopic origin of

persistence of matter (soliton cores reconstruct),

persistence of gauge fields (twist modes reconstruct),

persistence of curvature patterns (spatial geometry reconstructs),

and the local geometric responses—stretching, curvature equilibration, shrinking—described in

Section 8.6.

Thus RNF propagation is local 4D reconstruction: chronon alignment copies the entire coherent pattern into the next infinitesimal layer of spacetime, while TCP provides the metric adjustment needed to maintain the preferred coherence density.

These features, illustrated in

Figure 3, ensure that as the RNF advances, solitons, gauge twists, curvature distributions, and vacuum structure are reinstantiated with high fidelity, yielding a smooth and dynamically consistent emergent spacetime.

5.2. Motion and Interactions as Reconstruction Dynamics

Because nothing moves

within a fixed RNF slice, all apparent motion arises from where a given pattern is re-instantiated when the next slice is created. Let

denote the solitonic pattern corresponding to a particle. On

the RNF places this pattern at the position

that minimizes the local TCP spatial energy:

Small spatial displacements

give

so the effective velocity is

5.2.0.16. Interpretation.

From within this may appear as global optimization, but in the chronon ontology it is completely local: each chronon aligns with the chronon “above’’ it (in meta-time), while neighboring aligned chronons exert small tilting biases. These tiny biases accumulate slice by slice into what observers interpret as inertia and forces.

For the remainder of this paper, and for notational simplicity, we use “RNF copying” to denote both exact copying and copying accompanied by TCP-guided pattern shifts; this distinction is immaterial because such shifts preserve the coherence content and do not affect the subsequent coherence-restoration analysis.

Interactions.

Different distortions of correspond to:

curvature gradients ⇒ geodesic motion,

gauge twists ⇒ electromagnetic forces,

soliton overlap distortions ⇒ mutual forces.

Photons are special: as pattern-preserving excitations they propagate along the chronon-induced null cone

, producing the two-metric phenomenology of

Section 10.

Thus motion and interaction arise entirely from the slice-by-slice reconstruction of chronon patterns.

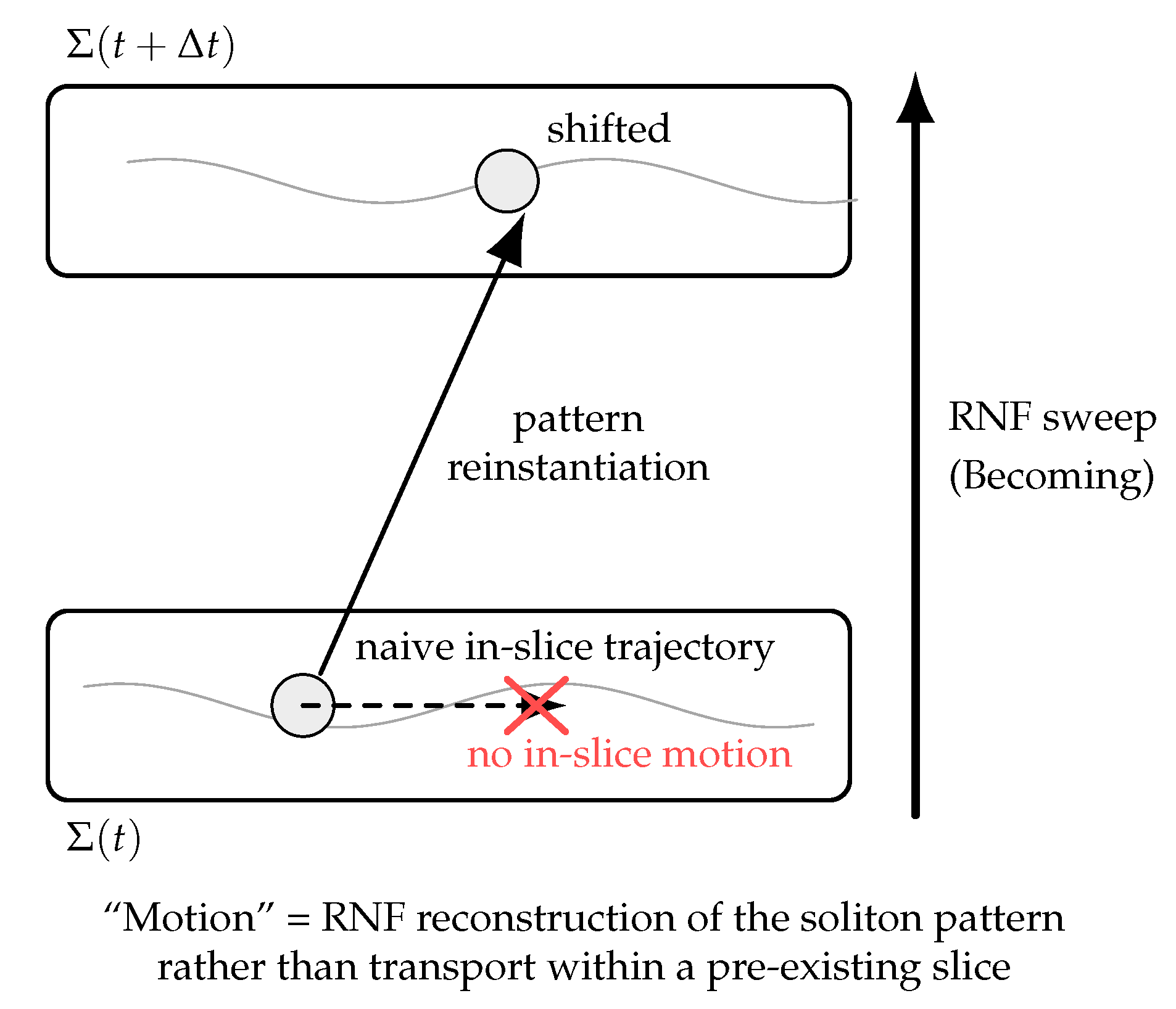

Figure 4.

Illustration of motion as reconstruction in the RNF framework. The lower and upper rectangles represent successive slices and . The soliton does not move within a pre-existing slice; instead, the RNF generates the next slice with the soliton pattern reinstantiated at a shifted location. Conventional trajectories (dashed arrow) are effective descriptions of this underlying reconstruction process.

Figure 4.

Illustration of motion as reconstruction in the RNF framework. The lower and upper rectangles represent successive slices and . The soliton does not move within a pre-existing slice; instead, the RNF generates the next slice with the soliton pattern reinstantiated at a shifted location. Conventional trajectories (dashed arrow) are effective descriptions of this underlying reconstruction process.

5.3. Geometric Volume Response from RNF Reconstruction

A defining feature of RNF cosmology is that the unaligned chronon domain carries no geometric structure. When the Real–Now–Front advances, TCP induces a spatial metric on the newly aligned patch so that the inherited chronon pattern attains the preferred coherence density

(

Section 6.2).

Crucially, RNF advancement does not imply universal volume increase. Because the internal “defect + curved vacuum” pattern is copied across slices, TCP can restore coherence only by adjusting the metric volume assigned to that pattern. This leads to three generic local geometric responses:

Vacuum-rich regions () undergo metric stretching and local expansion;

Near-equilibrium regions () exhibit GR-like behavior with slowly varying volume;

Curvature-rich regions () undergo metric contraction, potentially leading to collapse and MCC formation.

In statistically homogeneous vacuum-dominated regions, this local response becomes uniform and yields an FRW-like expansion law. The full mathematical formulation of metric stretching, coherence-density scaling, TCP bifurcation, and the resulting Hubble law is developed in

Section 8 and

Section 8.5.

6. Early Universe: Smoothness, Flatness, and Horizon Resolution

In RNF cosmology, the large-scale smoothness, near-flatness, and uniformity of the early Universe arise from the statistical properties of the pre-geometric chronon medium and from chronon alignment under the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP). Before alignment, the chronon substrate possesses no metric, no causal cones, and no horizons. Nevertheless, its microphysics is statistically homogeneous: every region of the unaligned medium has the same local chronon statistics by symmetry. Geometry appears only after RNF alignment imposes coherent structure; the classical puzzles of standard cosmology—horizon, flatness, and initial-condition tuning—are therefore reframed. Smoothness does not require superluminal expansion or horizon-spanning correlations; it reflects the uniformity of the substrate from which geometry is later constructed.

This behaviour parallels ordering phenomena in nonlinear media [

30,

31], where an initially featureless state undergoes coarsening, defect formation, and relaxation toward a characteristic defect density. In RNF cosmology the analogue is TCP-driven relaxation toward a preferred coherence density

, which sets the equilibrium balance between aligned vacuum and localized curvature.

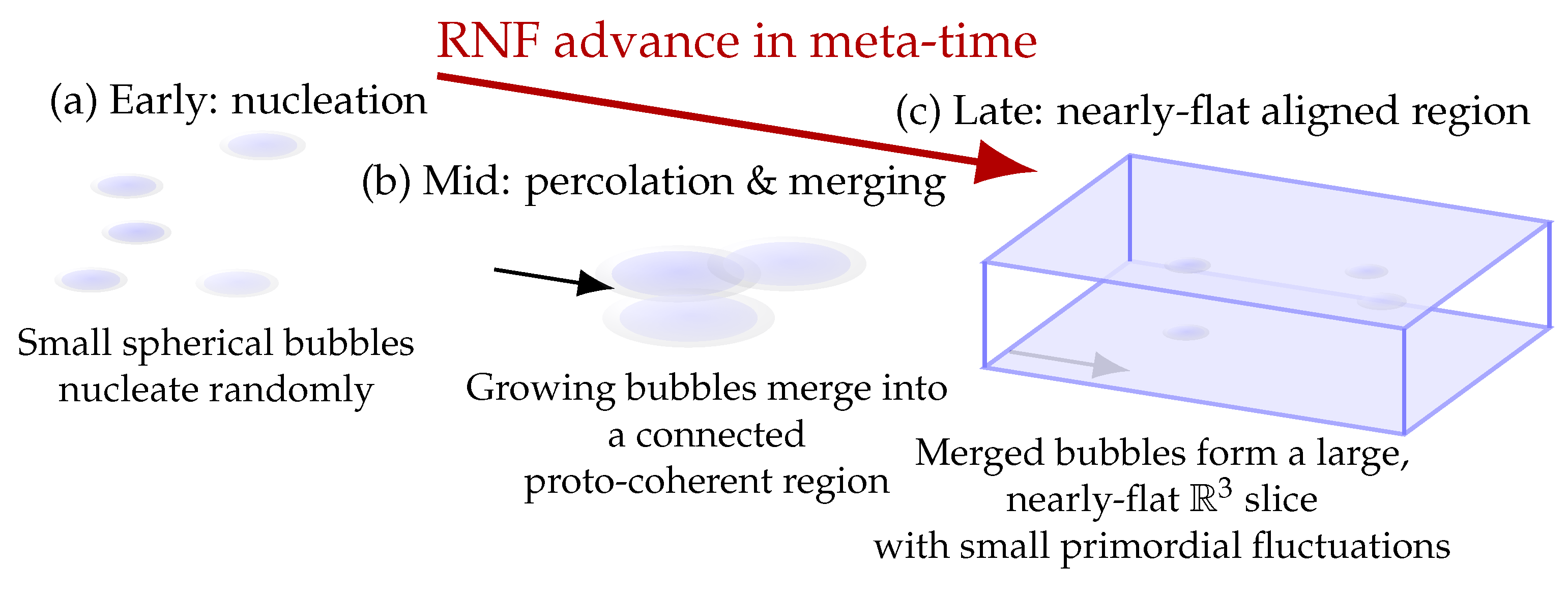

6.1. RNF Foam and the Emergence of Global Coherence

The chronon medium begins in an unaligned, pre-geometric phase. Small aligned patches nucleate stochastically, creating a multi-domain network—an

RNF foam. These domains expand, merge, and eliminate misaligned interfaces in the same manner as phase-ordering dynamics [

32,

44]. TCP penalizes large gradients and deviations from the preferred coherence density, gradually steering each region toward a stable “defect + aligned-vacuum” configuration.

Three processes structure this epoch:

domain coarsening through TCP suppression of strong gradients,

defect capture and annihilation at domain collisions,

percolation of aligned domains into a single connected region.

Once percolation is achieved, the RNF becomes a single coherent three-surface. At this moment the Universe first acquires a global geometric structure. Because the pre-geometric medium was statistically homogeneous, each region entering the aligned phase inherits effectively identical local structure.

The Universe becomes smooth because the substrate it is built from is uniform, not because distant regions ever required causal contact.

Thus the horizon problem never arises: smoothness and isotropy follow from substrate homogeneity plus TCP alignment, not from inflationary stretching of a causally connected patch.

6.2. Preferred Coherence Density in the Early Universe

A central microphysical ingredient of RNF cosmology is the existence of a

preferred coherence–curvature density selected by chronon dynamics. This density determines the equilibrium balance between vacuum alignment and localized curvature (defects, solitons) in an ordered chronon medium. Its existence is generic and follows from simple energetic considerations; a formal derivation from coarse-grained Chronon Field Theory is given in

Appendix B.

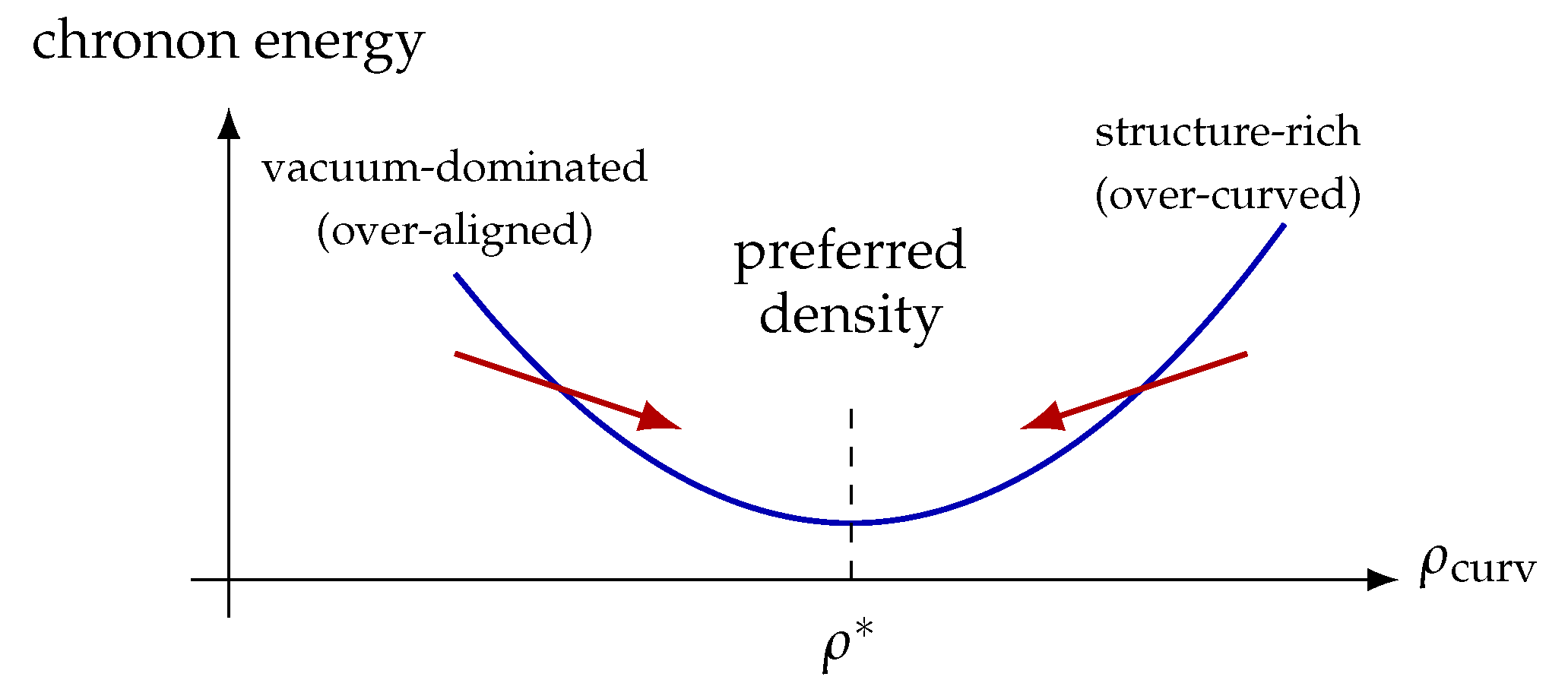

Competing microscopic tendencies.

Chronon alignment energetically favors coherent, low-entropy regions, but perfect alignment is not optimal. If the medium becomes too homogeneous, any perturbation produces large gradients in , increasing the Skyrme-type quartic term in the chronon energy functional. Thus extremely aligned vacuum carries a coherence penalty. Conversely, excessive curvature or defect concentration also raises the energy by increasing local misalignment. Between these two extremes lies an energetically preferred density of “defect + curved vacuum” content that minimizes the local chronon free energy.

Early-universe condensation.

During the initial ordering of the chronon medium, alignment fronts nucleate and expand. As defects form and smooth out, the medium naturally relaxes toward the preferred density . This process mirrors defect-mediated ordering in condensed-matter quenches, where gradient and quartic terms balance to produce a stable density of vortices, disclinations, or topological textures.

Why newly aligned regions must copy the previous slice.

When the RNF invades an unaligned region, that region can no longer form its own defect population dynamically—unaligned chronons lack geometric structure and cannot sustain curvature. Instead, the TCP reconstruction process

copies the pattern of the previously aligned layer, preserving its coherence density. Thus

is not only a microphysical optimum but also a

dynamical attractor: every newly formed slice inherits its structure from the advancing RNF and then relaxes locally toward the same preferred density. See

Figure 5 for a schematic demonstration.

Implications for cosmic evolution.

Once the Universe becomes largely aligned, local deviations from the preferred density directly determine the response of the induced metric:

: under-curved, coherence too high ⇒ TCP expands (stretches) the metric.

: balanced configuration ⇒ supports local gravity and yields FRW-like evolution.

: over-curved, coherence too low ⇒ TCP contracts (shrinks) the metric into MCCs.

These three regimes underpin the TCP bifurcation discussed in later sections.

6.3. Flatness from TCP Coherence-Equilibration

After percolation, the Universe consists of an almost uniformly aligned chronon field, but with small spatial variations: trapped twists, incipient solitonic cores, and mild deviations from the preferred coherence density .

The TCP functional,

measures departures from the locally optimal “defect + aligned-vacuum’’ pattern and drives each region toward the coherence density

that minimizes the chronon free energy. This produces the three-regime behaviour of

Section 8.6:

Stretching branch: vacuum-rich (over-coherent) regions expand.

Equilibrium branch: regions with adjust their curvature with minimal change in volume.

Shrinking branch: structure-rich (under-coherent) regions contract.

In the early Universe the equilibrium branch dominates. Misalignment gradients and small curvature irregularities are efficiently damped, and each RNF slice relaxes toward a nearly flat metric. Subsequent RNF copying preserves this low-curvature pattern, while mild global stretching in vacuum-rich regions dilutes any remaining variations.

Flatness is therefore not a fine-tuned initial condition and not an inflationary attractor; it emerges naturally from TCP coherence-restoration acting during and shortly after alignment. The metric is generated only after large-scale smoothness is already statistically encoded in the homogeneous chronon substrate, and TCP equilibration ensures that the first geometric slices are nearly flat.

6.4. Origin of Primordial Perturbations

TCP smoothing ensures large-scale uniformity, but small fluctuations are unavoidable in any nonlinear alignment medium. In RNF cosmology they originate from deviations from the preferred coherence density through two microphysical channels:

RNF reconstruction preserves these features slice by slice, so once imprinted the perturbations remain stable and coherent.

Near scale invariance and spectral tilt.

During early coarsening, the alignment pattern exhibits a single growing correlation length,

with dynamic exponent

set by chronon microphysics. Curvature fluctuations generated at scale

L satisfy

yielding a spectrum that is naturally close to scale invariant for

, as expected for relativistic ordering dynamics. A small red tilt would arise if

, but determining the precise value of

requires a dedicated RNF/ChFT calculation that remains to be carried out.

Tensor perturbations require long-range transverse-traceless modes of , but these are strongly suppressed both before and after alignment. RNF cosmology therefore predicts a very small primordial tensor amplitude ().

Summary.

RNF cosmology naturally produces:

nearly scale-invariant scalar perturbations from alignment-domain coarsening,

a plausibly slight red tilt depending on the coarsening exponent (not yet derived microscopically),

negligible primordial tensor modes (),

small, physical non-Gaussianities associated with defect formation and capture.

These perturbations arise from chronon microphysics—not from inflaton potentials, vacuum fluctuations, or superluminal expansion.

6.5. Comparison with Inflation

In standard cosmology, inflation solves the early-universe puzzles by stretching pre-existing geometry. In RNF cosmology these puzzles do not arise: geometry is generated after the chronon substrate has already become statistically homogeneous and after TCP alignment has eliminated misaligned gradients.

Horizon problem: Inflation stretches correlations; RNF cosmology inherits homogeneity from the pre-geometric substrate.

Flatness: Inflation drives curvature toward zero; RNF cosmology drives curvature toward the TCP equilibrium density .

Perturbations: Inflation sources them from quantum vacuum modes; RNF cosmology sources them from defect remnants and alignment stochasticity.

Tensor modes: Inflation allows ; RNF cosmology predicts .

Late-time acceleration: Inflation is separate from dark-energy dynamics; RNF cosmology produces acceleration through geometric stretching in vacuum-rich regions (the stretching branch), without dark energy.

Thus RNF cosmology offers a microphysical, generative alternative to inflation: smoothness and near-flatness reflect the properties of the chronon substrate and TCP equilibration, not exponential expansion driven by a scalar field.

Figure 6 is a schematic illustration of the early universe.

7. Structure Formation in the RNF Framework

RNF cosmology reproduces the large-scale phenomenological successes of the CDM structure–formation paradigm while grounding its ingredients in a generative microphysical model of spacetime, coherence, and dark matter. Differences arise from three structural features of the chronon–TCP system:

the origin and scaling of primordial perturbations from TCP coherence-equilibration dynamics during RNF-domain coarsening,

the microphysical nature of dark matter as coherence-regulated solitonic structures (MCCs),

a mild two-metric structure arising from the distinct ways photons and matter propagate through RNF slices.

At cosmological scales these differences leave the standard linear-growth picture almost unchanged; deviations appear primarily on small scales and in precision distance and growth measurements.

Primordial perturbations from RNF percolation and TCP coherence dynamics.

As described in

Section 6, the Universe transitions from an initially unaligned chronon medium to a single connected aligned region as the RNF percolates. Throughout this epoch, the TCP coherence-restoration rule drives each domain toward the preferred coherence density

. Departures from

—whether excess coherence (vacuum-rich) or deficient coherence (structure-rich)—generate local geometric distortions once a metric appears.

Two microphysical channels robustly produce scalar perturbations:

Because the chronon substrate is already statistically homogeneous before the metric exists, long-range coherence is imprinted prior to the emergence of light cones. Thus the horizon problem does not arise: homogeneity is inherited from the pre-metric substrate, not generated by superluminal expansion.

TCP coherence-equilibrium then damps large gradients while preserving the scaling behaviour of fluctuations. Tensor modes remain extremely suppressed, since long-range transverse–traceless excitations of are energetically disfavored.

RNF reconstruction preserves these perturbations slice by slice, ensuring their fidelity until they re-enter causal horizons.

Linear growth under emergent Einstein dynamics.

Once the RNF has produced a sufficiently coherent and nearly flat region, metric perturbations evolve according to the emergent Einstein equation obtained from chronon hydrodynamics [

12,

13]. At linear order the matter overdensity satisfies

where

depends on chronon stiffness parameters

that govern how the medium responds to coherence-density deviations.

Corrections to GR scale as

, where

is the chronon coherence length (

Appendix E). Thus for modes with

—the cosmologically relevant regime—RNF cosmology recovers standard linear growth. Departures appear only at high precision or at small physical scales.

Micro Chronon Condensates (MCCs) as dark matter.

Within TCP microphysics, stable solitonic structures appear whenever a localized chronon distortion plus its self-consistent aligned vacuum minimizes the coherence energy. These objects—Micro Chronon Condensates (MCCs)—play the role of cold dark matter.

Key properties follow directly from coherence-density physics:

Cold and collisionless: MCCs form nonrelativistically and interact almost exclusively through the emergent gravitational field, reproducing CDM-like clustering.

Finite core radius from TCP equilibrium: TCP stabilization at coherence density

gives

producing naturally cored halo profiles and alleviating the cusp problem.

Granularity at small scales: For modes with , MCC discreteness and coherence-equilibrium effects suppress power, while large-scale () behaviour remains CDM-like.

Black-hole mimicry for high mass: Massive MCCs approximate GR black-hole exteriors with high accuracy, consistent with strong-lensing and shadow measurements, while maintaining CEP-regulated interiors.

Thus RNF cosmology preserves the large-scale clustering success of CDM while predicting distinctive microphysical structure in dark-matter halos.

Two-metric effects from RNF reconstruction.

As shown in

Appendix E, photons and matter couple to slightly different emergent metrics:

because photons propagate as transverse chronon waves within each slice, whereas matter solitons are reconstructed across slices under TCP.

This produces subtle but testable phenomenology:

BAO–SN distance offset: BAO relies on , while SN luminosity distances trace , generating a small redshift-dependent mismatch.

Growth-rate shifts: probes matter geodesics, whereas CMB and BAO infer expansion from photon geodesics.

Lorentz invariance preserved: The Co-moving Concealment Principle ensures both metrics share identical local inertial frames, consistent with observational bounds.

These effects are cosmologically small but offer sharp discriminants between RNF and CDM.

Summary.

Structure formation in RNF cosmology rests on four pillars:

Primordial perturbations sourced by TCP coherence dynamics during RNF-domain coarsening, not by inflaton fluctuations.

GR-like linear evolution emerging from the hydrodynamic limit of chronon alignment.

A cold MCC dark-matter sector that matches CDM on large scales while predicting microphysical halo structure at small scales.

Two-metric phenomenology yielding subtle but testable redshift-dependent differences between matter- and light-based observables.

Accordingly, RNF cosmology reproduces the large-scale successes of CDM while providing a microphysical and generative origin for perturbations, coherence, dark matter, and small but measurable departures from the standard model. A full quantitative comparison will ultimately require Boltzmann codes adapted to RNF hypersurface propagation and chronon-based perturbation evolution.

8. Cosmic Expansion as a Local Geometric Response to TCP Curvature Restoration

In RNF cosmology, a spatial slice is not a pre-existing three-dimensional manifold but the instantaneously reconstructed boundary of the newly aligned chronon domain. The Real–Now–Front (RNF) is a propagating 3D hypersurface in a 4D pre-geometric medium; the induced spatial metric arises from chronon alignment obeying the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP). Geometry, curvature, and local scale are therefore outputs of the alignment process, not background structures.

This viewpoint is aligned with ADM hypersurface geometry [

23,

40,

42] and with emergent-gravity approaches in which curvature is a collective, pattern-dependent response of a microscopic medium [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Crucially:

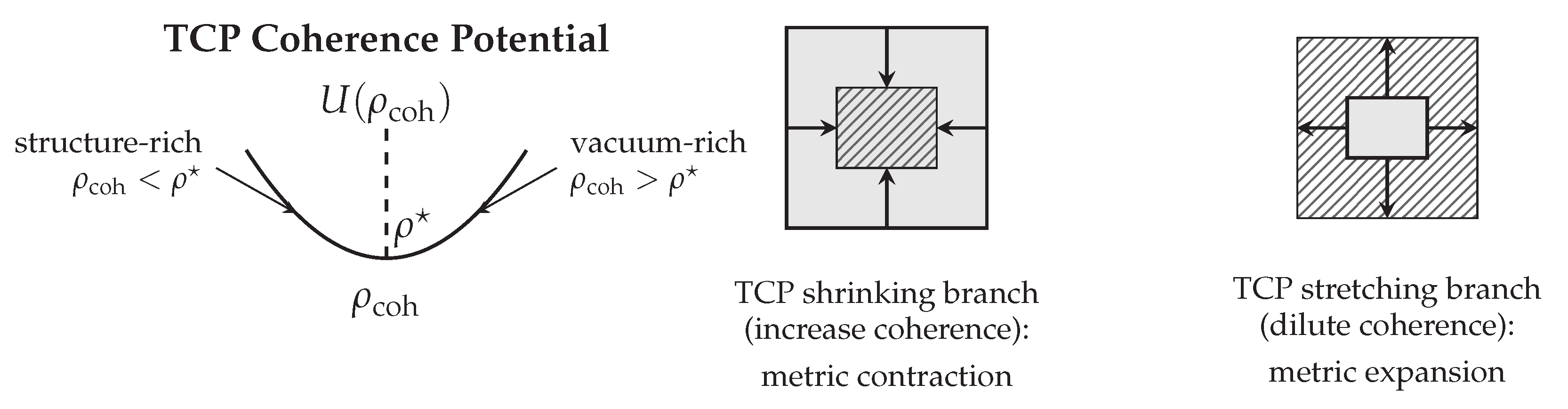

Cosmic expansion is not driven by stress–energy or vacuum pressure, but arises whenever the curvature density of the aligned pattern lies below the preferred TCP value .

TCP always attempts to restore the local “defect + curved vacuum” structure to the coherence–curvature density associated with a stable chronon pattern. Thus:

If the reconstructed slice is under-curved (), TCP lowers its energy by stretching the metric: cosmic expansion.

If the curvature is near , TCP produces only mild adjustments, yielding equilibrium GR and FRW-like evolution.

If the curvature is too large (), TCP lowers its energy by shrinking the metric: collapse into MCCs.

These three responses constitute the TCP bifurcation that governs the global evolution of the Universe.

We now derive the corresponding geometric law of expansion and show that accelerated expansion emerges generically from the stretching branch.

8.1. Local Reconstruction and the TCP Curvature–Density Condition

When the RNF advances by a normal distance into an unaligned region, a thin new layer of chronons becomes aligned. Because the pre-geometric domain carries no metric, the induced metric on the new layer is selected by TCP so as to minimize the local alignment energy.

A central consequence is that TCP drives each newly reconstructed slice toward a preferred coherence–curvature density

. In the language developed later (Sec.

Section 8.5), this density is a coarse-grained quantity obtained by dividing the integrated local coherence content of the inherited chronon pattern by the assigned spatial volume:

Because RNF reconstruction copies the internal chronon pattern while allowing the metric volume to adjust, deviations from

are corrected primarily through local volume rescaling. Schematically, for a comoving patch of physical volume

,

Accordingly:

if , TCP restores coherence by metric stretching ( increases);

if , TCP restores coherence by metric shrinking ( decreases).

RNF advancement therefore induces a local rescaling

The stretching branch underlies cosmic expansion, while the shrinking branch leads to local collapse and the formation of Micro Chronon Condensates (MCCs). A quantitative formulation of coherence density, metric rescaling, and the associated TCP bifurcation is developed in Sec.

Section 8.5.

8.2. Hubble Law from Hypersurface Kinematics

Let

be the induced metric on

. When the RNF advances by

along its normal

, the ADM evolution identity gives

where

is the extrinsic curvature.

In homogeneous and isotropic regions:

Substituting into (

17) yields

implying the Hubble relation

Thus the FRW expansion law is a geometric identity arising solely from the motion of the RNF hypersurface.

8.3. Why Expansion is Generic in the Large-Scale Universe

The early Universe after percolation (

Section 6) is extremely smooth and nearly flat due to TCP curvature smoothing. Such a region is typically

under-curved relative to the preferred curvature density

because curvature associated with defects has been diluted.

Thus the large-scale Universe enters the stretching branch:

Cosmic expansion is therefore not an exotic dynamical phenomenon—it is the

default response of the chronon medium to under-curvature. No vacuum energy or negative-pressure fluid is required [

20,

21].

8.4. Local RNF Expansion Theorem

Theorem 8.1 (Local RNF Expansion Theorem). Let be an RNF slice with metric and extrinsic curvature . Assume:

the RNF advances by during ,

TCP drives the curvature density to the preferred value ,

the patch is isotropic: .

Then the induced scale factor satisfies:

where is one-third the trace of :

Proof. Insert isotropy into the ADM evolution law

Taking

yields the differential identity

TCP curvature restoration guarantees that this rescaling is required to bring , completing the proof. □

Interpretation.

The FRW expansion law is not a dynamical equation—it is the local kinematic imprint of RNF propagation plus TCP curvature restoration.

8.5. Metric Stretching/Shrinking as Coherence-Density Restoration

1. A local coherence scalar and its density.

Let

be the ontological chronon alignment field on the underlying smooth manifold, and let

be an RNF slice with induced spatial metric

and volume element

. Introduce a nonnegative

coherence functional density built from local chronon structure (one convenient choice is the simplest quadratic alignment measure)

where

denotes the (coarse-grained) symplectic/vorticity two-form associated with the aligned phase and

sets units.

For any comoving domain

, define the

coherence content

the physical volume

and the

coherence density

2. The RNF copying constraint: “pattern fixed, volume adjustable.”

RNF reconstruction copies the internal chronon pattern slice-by-slice. To leading order in a single RNF step, this means that the comoving distribution of

is inherited, so

is approximately conserved across the step,

TCP therefore restores primarily by changing the metric volume assigned to the fixed pattern.

3. Metric stretching/shrinking and the density scaling law.

Model the immediate TCP response within

as an (approximately) isotropic rescaling of the induced 3-metric,

Using

from Equation (

23), the coherence density transforms as

Hence metric

stretching (

)

dilutes coherence density, while metric

shrinking (

)

concentrates it:

4. Preferred density and the TCP “restoration” rule.

TCP selects a preferred value

(set by chronon microphysics), implemented as minimization of a local effective potential

with a minimum at

:

Given

on the inherited pattern, the instantaneous TCP rescaling chooses

s so that

moves toward

:

Therefore:

while

yields

(near-equilibrium, GR and FRW-like evolution).

5. Connection to extrinsic curvature and the local Hubble law.

In Gaussian normal slicing,

so the local volume-creation rate

satisfies

. For an isotropic scaling

, one has

, and therefore

(

Appendix C). The sign of

matches the TCP branch:

Interpretation.

The coherence density

measures the amount of aligned chronon structure per unit physical volume on an RNF slice. Metric rescaling changes

only the denominator of Equation (

22) during reconstruction, while the numerator is fixed by RNF pattern copying. Thus expansion and contraction are not dynamical responses to stress–energy, but purely geometric operations required to restore coherence density toward its preferred value

.

8.6. TCP Bifurcation: Stretching, Equilibrium, and Collapse

The Temporal Coherence Principle admits three distinct local responses, depending on the coherence density inherited by a comoving patch during RNF reconstruction:

Stretching branch (). The copied patch is vacuum-rich and therefore over-coherent. TCP restores coherence by diluting through metric expansion (). This branch produces local Hubble-like expansion and dominates void regions.

Equilibrium branch (). Coherence density is near its preferred value. TCP does not drive significant volume change () and instead acts primarily through redistribution of curvature within an approximately fixed volume. This regime yields standard GR-like dynamics and FRW evolution.

Shrinking branch (). The patch is structure-rich and under-coherent. TCP increases by contracting the metric (), amplifying curvature until CEP saturation halts collapse. The endpoint is a stable Micro Chronon Condensate (MCC) or, at higher mass, a CEP-regulated black-hole interior.

These three responses form a genuine TCP bifurcation. Cosmic expansion, ordinary gravity, and compact-object formation therefore arise as different local geometric responses of the same chronon medium to coherence-density restoration.

8.7. Late-Time Acceleration from RNF Propagation

At late cosmic times, large-scale regions are expected to be increasingly vacuum-dominated as structure formation localizes coherence into compact objects. Such regions generically satisfy and therefore lie on the stretching branch of TCP.

As a result, RNF reconstruction continues to induce metric expansion in these regions. Whether this expansion asymptotically approaches a constant-rate (de Sitter–like) behavior or exhibits slow evolution depends on the chronon stiffness parameters governing the effective potential and the relaxation timescale of TCP restoration.

Thus RNF cosmology predicts late-time acceleration as a geometric response to vacuum dominance, without invoking vacuum energy. Determining the precise functional form of requires a quantitative derivation of chronon microphysics and is deferred to future work.

8.8. Summary

In RNF cosmology, cosmic expansion follows directly from chronon microphysics and RNF reconstruction:

RNF advancement continuously generates newly aligned spatial slices with no preset physical scale.

RNF copying preserves the internal chronon pattern of each patch, fixing its coherence content while leaving its metric volume adjustable.

The Temporal Coherence Principle restores the local coherence density toward a preferred value by metric stretching () or shrinking ().

In near-equilibrium regions this produces GR-like/FRW-like expansion as a geometric consequence of hypersurface kinematics.

Vacuum-dominated regions preferentially lie on the stretching branch, while over-structured regions collapse into CEP-regulated solitonic objects (MCCs).

Cosmic expansion, compact-object formation, and late-time acceleration thus emerge as distinct local geometric responses of a single mechanism: TCP-driven coherence-density restoration during RNF hypersurface propagation.

Figure 7 illustrates how the Temporal Coherence Principle (TCP) determines whether a comoving patch expands or collapses as the RNF advances.

9. Collapsed Objects and Cold Dark Matter in RNF Cosmology

Cosmic expansion and the formation of collapsed objects originate from the

same local TCP reconstruction mechanism. As shown in

Section 8, when the RNF aligns a new layer of chronons, TCP compares the inherited curvature density of the copied pattern to the preferred value

fixed by chronon microphysics. This comparison determines whether the induced metric must stretch or shrink:

The stretching branch yields cosmic expansion. The shrinking branch produces

local collapse: a comoving region is assigned a smaller metric volume on the next RNF slice, raising its curvature density until the Chronon Exclusivity Principle (CEP) halts compression. This mechanism is analogous to curvature focusing in GR [

63] and to pattern collapse in nonlinear media [

31,

32].

Cosmic expansion and solitonic dark matter are two outcomes of a single TCP curvature–restoration bifurcation.

This section develops the microphysics of the shrinking branch, the CEP regulator, and the resulting spectrum of collapsed, dark, nonsingular objects.

9.1. TCP Shrinking Branch and the Onset of Collapse

If the inherited chronon pattern in a local patch carries

excess curvature relative to the preferred density

, TCP must

shrink the induced metric to raise the curvature density toward its target:

The reduced metric volume increases curvature and gradient energy, driving the patch into a collapse regime reminiscent of GR curvature focusing [

63]. As curvature increases, the patch eventually encounters a microphysical limit: the Chronon Exclusivity Principle.

Collapse in RNF cosmology is therefore:

a local, microphysical effect of TCP reconstruction,

triggered purely by geometric mismatch (),

regulated by CEP at high curvature.

This mechanism mirrors soliton formation in nonlinear field theories [

72,

75], but arises here from the microscopic alignment dynamics of spacetime itself.

9.2. Chronon Exclusivity Principle (CEP)

Chronon Field Theory assigns each solitonic pattern element a quantized symplectic-curvature flux. The Chronon Exclusivity Principle states that a finite spacetime cell cannot support curvature density beyond a fixed microphysical limit:

where

is the symplectic curvature density and

the chronon stiffness scale.

As TCP-driven collapse raises

, the curvature density approaches

. Once this saturation occurs, further compression becomes impossible: the chronon medium transitions to an effectively incompressible, finite-density state. The result is a minimal-radius

chronon core—the CEP analog of a topological soliton core in other nonlinear systems [

72].

This replaces the singular interior of GR collapse [

63] with a nonsingular, microphysically regulated structure.

9.3. Core Radius and the Universal Law

A CEP-saturated core contains

N curvature quanta, with

because mass corresponds to integrated curvature content in ChFT. Since each quantum occupies a minimal cell,

implying the universal scaling law

This

behavior parallels the scaling of solitonic and condensate cores in several nonlinear systems [

66]. A key implication is

which determines whether the final object is an MCC or a CEP black hole.

9.4. MCCs vs. Black Holes: Two Outcomes of the Same Soliton Core

A CEP core forms first. Whether a horizon develops is governed by the standard Schwarzschild condition:

1. Micro Chronon Condensates (MCCs).

If

the configuration is horizonless. MCCs are:

nonsingular solitonic objects,

extremely compact (near Planck scale for minimal mass),

absolutely stable,

2. CEP-regulated black holes.

If

the exterior geometry is standard Schwarzschild/Kerr, but the interior is non-singular and saturated by a finite-density CEP core. This resembles gravastar-like interiors [

76] but with a microphysical, not phenomenological, origin.

9.5. Gauge Freezing and Electromagnetic Darkness

Gauge fields in ChFT arise from twist modes of the chronon-alignment bundle. Inside a CEP-saturated core, alignment collapses to a single orientation and all twist modes vanish:

This resembles gauge-structure freezing in certain condensed phases [

16,

17] and implies:

no electromagnetic or Yang–Mills charge can be supported,

no flux or radiation can escape from the core,

gauge fields cannot propagate through the interior.

Thus MCCs are

intrinsically dark without hidden sectors or new particles, consistent with observational constraints on compact dark matter [

68].

9.6. Stability and Absence of Evaporation

Because quantum vacuum fluctuations do not exist in the chronon medium, Hawking radiation—which relies on vacuum-mode excitation near a horizon [

77]—works differently [

8]. The emission is exponentially suppressed leakage of curvature waves:

Both MCCs and CEP black holes are therefore stable over cosmological times, much like solitonic compact objects in other theories [

78].

9.7. Formation of MCCs During RNF Alignment

During early RNF percolation:

domain boundaries trap symplectic curvature, similar to defect formation in quenched phase transitions [

15],

over-curved TCP patches enter the shrinking branch,

CEP saturation produces minimal-radius cores,

these cores become MCCs.

Even extremely small trapping fractions,

naturally yield the observed dark-matter density, paralleling estimates for primordial compact objects [

68].

Thus MCCs form automatically during spacetime genesis.

9.8. MCCs as Cold, Collisionless Dark Matter

MCCs satisfy all criteria for cold dark matter (CDM) [

56,

58,

59]:

Compactness: minimal radii near the Planck scale for low-mass cores.

Electromagnetic darkness: inside the core.

Collisionlessness: is far below observational limits.

Gravitational clustering: identical to standard CDM on large scales.

No new matter species or hidden sectors are required.

9.9. Unified Family of Collapsed Objects

RNF cosmology predicts a continuous spectrum of collapsed configurations:

MCCs: horizonless dark-matter solitons.

Chronon stars: intermediate, horizonless compact objects stabilized by CEP.

Astrophysical black holes: GR exterior with a CEP-regulated, nonsingular interior.

All arise from the same microphysical pathway:

9.10. Cosmological Summary

TCP curvature comparison yields two branches: stretching (expansion) and shrinking (collapse).

The shrinking branch raises curvature until CEP saturation.

CEP produces a minimal finite-density core with .

If , an MCC forms; if , a CEP black hole forms.

MCCs are stable, cold, collisionless, and electromagnetically inert.

Thus dark matter, black holes, and expansion share a single origin: TCP–CEP microphysics of the chronon field.

RNF cosmology provides a unified, generative account of collapse, compact-object formation, and dark matter without invoking new particles or exotic fields.

10. Photon vs. Matter Geometry: A Two-Metric Framework

A distinctive prediction of RNF cosmology is that photons and massive matter probe slightly different effective geometries. The origin is microphysical: photons propagate as pattern-preserving excitations within each RNF slice, while massive matter is reconstructed slice-by-slice from persistent internal chronon patterns. Because these two classes of excitations couple differently to chronon curvature and to RNF advancement, their long-distance propagation is governed by two closely related but not identical metrics.

Crucially, the two-metric structure is

not imposed. It emerges generatively from the chronon field and its TCP dynamics. On local scales the two metrics coincide to extremely high precision, ensuring operational Lorentz invariance and complete agreement with laboratory, solar-system, and binary-pulsar tests [

38,